Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 2

April 12, 2017

Pain’s parallel kingdom

Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays From a Nervous System by Sonya Huber. University of Nebraska Press, 177 pages

We are primitive in our methods, and the nervous system is a mystery.—Sony Huber, Pain Woman Takes Your Keys

Humans don’t want to think about pain—at least I don’t. But pain is our lot, sooner or later. For Sonya Huber, it came sooner.

[image error]

After a divorce and well into single motherhood, at 38, she contracted an autoimmune condition in which the thyroid slowly erodes. Within three months of that, she felt her skeleton “pulsing.” A new bodily self-sabotage—rheumatoid arthritis. As Huber points out, autoimmune diseases are when the body attacks itself, for largely unknown reasons. She endures constant joint pain—the main effect of her particular arthritis—along with whole-body aches and odd effects. Woven through Pain Woman Takes Your Keys is her effort to accept and make sense of her suffering.

She writes:

It took roughly five years of pain days to believe that the pain-free body had died. I need to understand that she is buried in photographs with my face, to understand that I am now living another incarnation of myself. . . .

Chronic pain is not a missing limb or open wound; it is the essence of invisible suffering. In Kevin Brockmeier’s novel The Illumination, characters in pain radiate light through their skin. I wonder what it would be like to live in a society like that, where our collective agony might blind us, or where the skin of the afflicted would shine as though they were ethereal beings. I wish I sparkled. I wish my pain made me beautiful, made me more noble, or was a fashion statement. Instead it is just pain, wordless and desperate for expression.

Because she’s a writer, Huber does express, in a considered and artful way. The linked essays in Pain Woman Takes Your Keys form a memoir with a narrative arc. Her desperation early on, when she realizes her fate, but still knows what it feels like to be pain free, makes her “feral.” She sees specialists and cries. She demands, of herself and doctors, to be healed. She settles for palliative measures. Medical professionals’ power over her—their ratings of her “difficulty,” their cold rejections, for endless insurance-related and humdrum reasons—gradually make Huber wary, furtive, meek. This degradation feels instantly real, and you’re angry on her behalf. Friends and colleagues, not knowing what to say when they notice a flare-up, often blunder. They suggest yoga, acupuncture, massage, all of which soothe but cannot defeat what’s undefeatable.

In opening the book, Huber writes more than three pages of declarative sentences starting with the word “pain,” including:

Pain has something urgent to tell you but forgets over and over again what it was.

Pain tells you to put your laptop in the refrigerator.

Pain wants to be taken to an arts and crafts store.

Pain demands that you make eye contact with it and then sit utterly still.

Pain would like French fries and Netflix.

The book’s witty title essay is about one of her few refuges, writing. At first afraid that the “fogginess and ache” of rheumatoid arthritis would destroy her practice, Huber still goes to the keyboard for an hour or more a day. The focus helps. Sometimes blogging is the best she can do. She explains how she wrote, in “an altered pain state,” her humorous post “Shadow Syllabus,” a hermit crab essay. It went viral. In the book, she explains the new persona, in life and on the page, that made that essay:

Pain Woman gives no shits. Pain Woman has stuff to tell you, and she has one minute to do so before she’s too tired. Pain Woman knows things.

My non-pain voice searches for metaphors to entertain you. She aims to fascinate with far-reaching, pretty, solar-system lava curlicues, hiding behind constructions that might allow you to forget for a second that you are even looking at a woman at all.

Pain Woman takes your car keys and drives away.

[image error]

Thus humor and offhand brilliance meet testimony and literary art. All crafted from hard experience and a fierce struggle. This is why summarizing fails Pain Woman Takes Your Keys. But why read a book about pain in the first place? I’ve had seasons in pain—back injuries and degenerative disc disease generally—and autoimmune diseases run in my family. Not just my own bad allergies. There’s an older sister’s decades with rheumatoid arthritis. A cousin’s Wegener’s disease, very rare. A cousin with severe asthma. An aunt who died from the side-effects of drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Maybe other stuff I’ve forgotten. As a hospice volunteer, I’ve seen suffering and different reactions to it.

Knowing someone who’s suffering makes real what we normally deny. I have attended a few writers’ conferences with Huber (and I reviewed her book on Hillary Clinton). Such familiarity surely helped me identify with her. But reading Pain Woman Takes Your Keys is searing because of its emotional honesty and its artful shaping. Readers cannot help but imagine themselves into Huber’s situation. Writers will admire what she has wrested from experience.

Sonya Huber answered some questions by email.

Q. Why did you write this as essays instead of as a straight narrative memoir? Having said that, these essays are so linked they are virtually chapters, and they deepen and they extend each other. There’s a progression in both time and disease/life stage. So do you think of this as a kind of “memoir” in the usual sense, even though the pieces are also discrete? And it’s called “essays” in its title. But it’s a stealth memoir, I’d say. Your structural approach has such intent behind it, and I wonder if you’d talk about that.

SH: When I started writing about pain, I knew that I didn’t want to write a narrative. Pain itself feels like it disrupts my sense of chronology—it almost lifts me out of time. Because I have told the story of my illness to doctors so many times, that chronology feels sort of numb and less interesting to me, and the timeline feels depressing, too, because there’s no cure or ending in my situation. I wrote these slices of my life with pain to offer a kind of escape and even a sense of play and delight for myself as the topics occurred to me.

Then, much later, I looked at the collection I had in progress and gave myself topics to fill in what I saw were the holes in the manuscript, the big topics I hadn’t yet taken on but that I knew were affected by pain. I like the fact that it might hold up as a stealth memoir! The ordering of the essays was done after the collection was finished, kind of as a mix tape, to break up the long serious prose with shorter bursts of lyric writing. But I never looked at the collection from the perspective of time, and now that I think about it, the first narrative piece (“Lava Lamp of Pain”) was the first one I wrote, and the last (“Ten Thousand Things”) was one of the last. So maybe there’s more chronology going on here than I’m aware of!

Q. How in the world did you write such a beautifully crafted and deep book so fast? Were you writing it after five years with your autoimmune diseases? You seem impressively quick even if you started writing three years in. Could you discuss the nuts and bolts of your process, of making this kind of art from your life?

SH: Thank you! I wrote the first piece at the end of 2014, so I had already been sick for over four years at that point. Until then, I wasn’t writing much about pain–although I was reading about pain and venting about it in my journal. The funny thing is that I was working on a different book project (a memoir) while I was writing these essays, and that book project felt really difficult. So I would “play hooky” on days when I couldn’t tackle the memoir and write about pain. The pain essays felt like recess, because I did not envision them as a collection. In a way they were a place for me to play with language and a way to make something pleasing or interesting out of a situation that I often frankly fight with a lot.

It doesn’t feel to me like I am a fast writer, but I do put things in documents whenever I have ideas, and I believe those accrue shape over time. So I might have had seven or eight pain essay ideas, and as something would occur to me on one of the topics, I’d write it in one of the documents and it would sit there and simmer. I worked for a number of years as a reporter and freelance journalist, and I think being involved with journalism has so much impact on my writing process. I just put text on the page and then worry later about what form it will take. That helps me get to a very rough draft.

Then—and this is so important—I would bring something that felt “done” to one of my two writing groups, and they were completely central. They helped me see where I was diving off the deep end of metaphor and abstraction. That’s my pitfall, especially with this project. My treasured readers helped rein me in. The last critical part of the piece was post-publication readers. I didn’t know I was writing about an interesting subject until after “Lava Lamp” [about the onset of her disease, her desperation, her screaming meltdown] was published in The Rumpus. I thought I was putting something out there that had to be published as a way to share around the agony a little bit, and then responses from readers helped me see with each publication that I could take a tiny further step out into what seemed like weirdness with the next publication. As I’ve only worked on completely structured books before, I had never had the experience of being emboldened by my readers in a step-by-step fashion, and once people—and editors—responded to something, I got more confidence to try the next thing.

Q. You portray one screaming meltdown. You’re at a low point, hardly able to believe what’s befallen you, and you drive hours to a specialist who can’t or won’t help you. Your raging despair in his parking lot is breathtaking, scary. It’s a departure from your largely quiet, thoughtful suffering. It really drove home your pain, loneliness, fear, and hopelessness at that point. But were you worried about readers not accepting this honesty? That is, in cnf terms, of not accepting your persona because of the way writers of nonfiction are judged in a way fiction writers aren’t?

SH: This is so interesting as a question—and it’s weird, I guess, that I never worried about it, as I always worry about my persona and how readers might view me. But in this case . . . this was one of the clear signpost events in my life that I never doubted writing about. I was so outside of myself with fear and anger that the event feels very objective, like a mystery or a monument I had to describe. In a way I can see that an alternate ordering of the book would lead up to this crisis, after the reader would get to see me as reflective and calm. But in real life that’s not how it feels. It feels like pain dropped into my life like a bomb. I guess I hoped that the reflection and language itself in the essay up until the crisis would make some of the readers trust me. And those who were going to be judgmental about a breakdown in a parking lot definitely would not want to read further. I never wanted to write a book—or even an essay—in which I might describe pain as less than overwhelming, as that doesn’t do justice to either the pain experience or to the many other people with pain. I guess I offered my reliability as persona as a sacrifice.

Q. I found it interesting that Buddhism’s lessons and tools suffuse this book. The penultimate essay, “Between One and Ten Thousand,” presents your ongoing Buddhist learning and practice. And thus Buddhism seems to resonate through the last essay, “Inside the Nautilus,” a tour de force of inquiry and reflection into official pain scales. How did you decide to do so much implicitly instead of writing straightforwardly, maybe near the start, about your spiritual path? And was it a preexisting condition, as it were, to your ailments?

SH: Oh thank you so much about that last essay—it’s one that’s close to my heart. Yes, Buddhism was a pre-existing condition. I’ve been practicing since 2004, after my son was born. So I am very lucky that I had a few years of meditation under my belt by the time pain hit, as meditation, among other supports, have all helped me get through days of pain. I think Buddhism sort of permeates rather than announces itself because the spiritual practice itself doesn’t offer a drastic change or an epiphany. It’s just another way to inquire. In many ways I think meditation made these essays possible. Buddhist monks in Tibet and India have a practice of going to charnel grounds, places where bodies were decaying above ground in order to look at the corpses and to study their own revulsion and resistance. Thinking about these things—the practice of watching my own struggle with my reality—gave me the support to describe an experience that for many is a bit repulsive.

Q. Your work underscores how far as a society we are from truly treating those in pain. I am thinking both in terms of pain management and in treating them with respect and compassion. Why do you think this is so, when there’s so much suffering? At the same time, America is said to have an opiate epidemic from some doctors’ laxity or corruption. Has that clouded the issue?

SH: This is such an urgent and complex question, and it connects to the previous question in terms of our clear revulsion toward pain as a society. We don’t like pain—well, no one does—but in the U.S., suffering is still often ascribed to character weakness. Calvinism, the Protestant Work Ethic, capitalism—all these systems tell us that we get what we deserve, and that we can make our lives better through individual effort. Effort is important, but we have a mythology that individual striving can erase all suffering, which is clearly not true. Pain is still, on some level, seen to be either psychosomatic, something having to do with age, or something related to a weak constitution. And pain of women and people of color is assumed to be exaggerated and not that urgent. So we’re often deluded about suffering. We can’t even look at it to examine it.

In terms of the medical system, I think our for-profit insurance-based healthcare has to go. It’s not working; doctors barely have time to spend with their patients. And most doctors don’t learn much about pain or pain management in medical school. Their training prioritizes cure as an achievement, and the absence of cure as a failure. Doctors do want to heal people, so chronic pain often feels like a failure to doctors. I think that connects to the opioid epidemic, and the genuine interest doctors may have in doing something to help within their limited structures. I think the primary cause of the epidemic is a medical system in which many patients received prescriptions because they don’t have insurance that is adequate to treat or investigate underlying conditions that might be causing pain, and doctors don’t have time to inquire into the causes or build a relationship with their patients.

The “opioid epidemic” has resulted in a crackdown on medications that chronic pain patients use to survive, and that’s wrong. The suspicion of chronic pain patients being seen as “med seekers” has been present for years, and it’s good to have some awareness about the dangers of substance abuse, but it’s strange that despite that concern, people with addictions still often go into debt to get treatment. What is unseen is that chronic pain people visit multiple doctors out of a genuine desire to get a diagnosis and get better. As I gradually realized there was no cure and that my former life was not coming back, I had profound desperation. That made me scream in a parking lot. It makes people do desperate things, including turning to substances or anything else that might provide relief. So chronic pain is often one piece of a puzzle to solve in a person’s life, and maybe other pieces are mental health, physical issues, employment that aggravates chronic conditions—but our medical system can’t see us as whole people in order to address these problems.

The post Pain’s parallel kingdom appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 29, 2017

Making Notting Hill’s long list

[U.S. war fleet, the Pacific, WWII. My father flew bombers in the Pacific theatre.]

Revising an essay about Dad’s prize bull & my wife’s hurt foot.

A year and a half ago here, I wrote about my excitement at having drafted an essay in which I relive accompanying my father to buy a Hereford bull when I was four. That’s the main story, but the essay really explores the complex relationship among memory, story, and imagination as I relive that trip and some other early memories. What happened to provoke it was fetching a cane for my wife, who was recovering from foot surgery two summers ago. That reminded me of a cane the bull’s breeder gave me. I still have it, over 55 years later. Why?

[image error]

[Charles C. Gilbert, a Pacific pilot in WWII.]

I found out late last week that my long complexly braided essay, “The Founder Effect,” has made the 2017 long list for the prestigious Notting Hill Essay Prize, a British-run worldwide biennial competition. They pay $20,000 and publish the winner, and publish their short list of top finalists. Two friends also made the long list: Jill Christman, who teaches at Ball State University, in Indiana, and Dave Madden, who teaches in the MFA program of the University of San Francisco.I don’t expect my essay to go further—I’m counting the long list as its award. What an honor and unexpected achievement. It’s hard to remember what I was thinking when I sent it in. For great reading, go to the 2015 long list and search your chosen authors and their titles—these “losing” essays have since appeared in an array of journals, and many are readable on line.

My essay will soon be three years old, and I’m still fiddling with it. After my first year of working on it, I had it so messed up. I quit it and dashed off (in comparison, at least) an essay on my crazy dog that was well received on Longreads. I actually used in the dog essay something I was trying in “The Founder Effect,” which is showing how I jump to conclusions about people and situations from mere scraps. I think that’s common, and says something about the operating system of the human mind: stories.

But after sending it around, it wasn’t getting anywhere with contests or journals. So I sent it to a friend who’d never seen it, and he said he couldn’t understand what I was getting at. I knew he was being honest and that I had to get some distance on it. I hired a developmental editor, the excellent Joan Dempsey, up in Maine, to read it and advise me.

[image error]

[Joan Dempsey: writer, coach.]

Joan pointed out that I started telling it one way, about my trip with Dad and related aspects, and then went into not apparently connected memoir stories. I let it sit a long time. Then I cut a ton. The trick for me was keeping some of the extraneous memoir stuff—material I felt shed a light on my father, his post-ranching life, and our relationship.And I restored something neither my friend nor Joan had seen. This is the essay’s initial foreground thread about Kathy’s recovering from foot surgery. That thread running through the essay really grounds it in the here and now. And it echoes the notion that in life as in stories, the little details and shadings, one way or another, are the big things. For example, the shallow step at our house’s side door and a low tile lip on our shower loom like Everest to someone with only one useable foot. A friend who brought us a casserole dish? Huge.

The real-time segments make the essay kind of amusing, too, because while Kathy was painfully recovering, and I was tending her, I was also going down the internet rabbit hole learning about the rancher who sold my farther a bull in remote southwestern Georgia over half a century ago. With that license, I dragged in Dad’s previous adventure, on the California ranch where I was born. And his pride in the bull he bred and registered there, Atoka Gold, whose quizzical eye now regards me from my atop my walnut dresser.

In the process of relating all this memoir to humans’ inner stew of memory, imagination, and story, I came to a new understanding of my father. This man who’d begun his aviation career in the wake of biplanes had ended up at the Kennedy Space Center. A failed rancher, yes, but also a former aviator who was helping to send humans into space. And, ultimately, to set a man’s foot on the moon.

How fitting Dad’s story arc; how sweet its trajectory.

[image error]

[Dad bred and registered this bull; the photo was taken about 1954, a year before my birth in Hemet, California.]

The post Making Notting Hill’s long list appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

March 8, 2017

A story structured in shards

[Natalie Portman as Jacqueline Kennedy, giving a White House tour.]

Portman & a film’s braided structure give an icon her human due.

God isn’t interested in stories. He’s interested in the truth.—a priest counseling Jacqueline Kennedy in Jackie

Since narrative appears to be the human mind’s operating system, I’d quibble with the priest. Naked truth, shorn of narrative, becomes eye-glazing philosophy or an aphorism that’s useful mostly in response to a story. But he’s a wily old coot, played by the great John Hurt in his last role, and bears witness to Jacqueline Kennedy’s private devastation. Though I doubt God was in the bullet that killed Jack Kennedy, the priest partly redeems himself by also declaring, “God is love . . .”

Interested in stories, I watched Jackie twice. Nothing against the delightful La La Land, or Emma Stone’s refreshing performance, but I was disappointed that Natalie Portman didn’t receive best actress honors. This injustice seemed an aspect of the largely salutary balancing of awards the academy undertook. Such as honoring La La Land’s visionary director for his joyous blockbuster while declaring the wonderful artsy film Moonlight as best picture.

Sort of like calling Stephen King “best author” but naming an obscure, challenging small-press title “best book.” Usually the literary set finds a compromise between those poles. Maybe for me, in cinema, that sweet spot this year was the strangely overlooked Jackie. There were too many great movies, or otherwise unlucky timing, or movie-world politics I don’t understand. But Jackie was unrivaled for Portman’s inspired performance and for its complex layering of time frames.

Portman nails Jackie’s breathy finishing-school voice—you imagine it began as an instructed affectation, as an adaption to a wealthier milieu, or as an ambitious adoption that became her. She also conveys Jackie’s sincerity, her flashes of insecurity, her fidelity to duty, and ultimately her pain. After the horror in Dallas, she plans Jack’s funeral, even as she medicates herself with alcohol, comforts her two young children, and oversees the packing of her family’s possessions for their abrupt exodus from the White House.

The movie opens after all that, scant days after the funeral, with Jackie being interviewed. She wants to further her husband’s legacy by cementing his image as a noble leader, as an aristocrat who loved the people, as a demigod. This foreground frame (or recurring braid, if you choose) grounds the narrative. Otherwise a succession of flashbacks, not always linear, the segments reflect Jackie’s PTSD and the nation’s disorientation. The background elements include:

• A televised tour of the White House Jackie gave, about a year into the couple’s residency, that focuses on her historical restoration.

• A concert in the White House that showcases Jackie’s devotion to art and culture. Likewise at times, the inaugural ball.

• Dallas, including the couple’s arrival, the shooting, the fruitless race to a hospital, LBJ’s oath of office on the airplane.

• Jackie’s research into Lincoln’s funeral, which she used as the model for JFK’s.

• Her battles to achieve those trappings we remember, such as the rider-less dark horse, and her vulnerable walking “with Jack,” as she thought of it, while exposed to other possible shooters enacting an unknown plot.

• Her counseling by the priest, in which she reveals her grief, her love for her late husband, and the flaws in their marriage.

Like many a boomer, I carry memories of November 22, 1963, when Kennedy fell in Dallas and Jackie scrambled briefly onto the car’s trunk: to retrieve a piece of his skull, the movie affirms, not to flee, as it appeared to many at the time. Then, as we watched: Oswald’s killing and JFK’s funeral and John-John’s brave salute. But I’d never contemplated Jacqueline Kennedy’s grief, much less her PTSD. She was an odd, glamorous celebrity, a myth seemingly of her own creation. Not like us.

Thus Portman’s sobbing is heart-rending as she portrays Jackie, 34 years old, scrubbing from her beautiful, agonized face her mate’s clotted gore.

[image error]

[Aboard Air Force One, after the shooting, returning to Washington, D.C.]

An edgy, fractured narrative deepens our understanding.

In the foreground interview, exactly one week after the assassination, Jackie is a grieving and traumatized woman; but, holding it together, she’s also steely, insightful, sardonic, calculating, and angry. Above all, she’s one pro dealing with another—a celebrity widow and the celebrity reporter she summoned. Both are vested in her glossy image, even as the journalist tries to negotiate for some human grit. Jackie won’t have it. “I don’t smoke,” she tells him as she chain-smokes through their meeting.

My beef with the film’s take here is the reporter’s insensitive, even disrespectful, attitude toward Jackie. Not only is this almost unimaginable in human terms, in real life the reporter, Theodore H. White, was the consummate beltway scribe. Friendly toward the Kennedys, he possessed, thanks to JFK and his own talents, a nascent literary franchise. White’s The Making of the President campaign series began with his account of JFK’s narrow victory over Nixon a few years before. This mega-bestseller also won him the Pulitzer prize. He was a respectful supporting player, the journalistic father of today’s fading print insider, Bob Woodward. And Jackie needed White, wanting to establish, as she did, the Camelot mythology for JFK’s short reign of under three years.

In real life, when White phoned-in his concise essay, of about 1,000 words, from the Kennedy’s Hyannis Port house, his editors resisted the Camelot metaphor, feeling it was overdone. White pushed back, at Jackie’s insistence. It remained. His interestingly structured essay is dated by that, the writer’s and Jackie’s sentimental collaboration, but it’s also of historical interest because of that excess. Years later, White wrote in his memoir In Search of History: A Personal Adventure that his editors were right; he was being kind to Jackie, but wished later he’d been less malleable.

I imagine that Jackie’s gifted Chilean director, Pablo Larrain, wanted his screenwriter—a journalist!—to seize the Hollywood cliché of the crass reporter because it provided a splash of vinegar. This gave Portman-as-Jackie something to play off; something to bring out her anger and a soupcon of bitterness at life in the fishbowl. Something to set apart the audience, in its growing sympathy for her, from the staring outside world. This braid has been criticized for, among other things, being unnecessary. But it does tremendous work in grounding the segmented narrative and in giving Jackie, and us, a slight distance from which to reflect.

The Guardian, which named Jackie number five among the top 50 U.S. films of 2016, wrote in its review:

The narrative doesn’t just move back and forth between the tragic day in Dallas, the arranging of the president’s funeral, her time spent accompanying her husband’s coffin to Arlington cemetery, and her earlier time in the White House – it often swirls, whirling the series of events together into a dizzying whole.

But what the fractured narrative does seems more considered and more precise than the Guardian’s summation. I’ve heard Jackie’s structure also called a mosaic, but I think there’s greater relationship among its elements than that term implies. The second time I watched Jackie, I saw how the Dallas flashbacks increase old-fashioned narrative suspense. Early in the movie, we see the first, survivable shot JFK took, to his neck. Certainly from that moment, the film makes an implicit promise to give its audience the next moment. The fatal one. But the filmmakers delay depicting the shot that removed the top of the president’s head. That wound left Jackie’s pink suit covered in blood for that whole day, in life, and for key scenes in the movie.

Finally the film delivers Jack’s death—and Jackie’s full experience of horror—in a way that deepens our compassion for her.

Jackie ’s skilled, versatile scribe favors compression.

Jackie didn’t win a single Oscar, and wasn’t even nominated for original screenplay. The winner in that category went to writer-director Kenneth Lonergan for Manchester by the Sea. I’m a fan of Lonergan’s, for Margaret, and Manchester’s a beautiful film. But I found its script, an exploration of grief, a letdown, both manipulative and mundane in the buried secret that haunts its protagonist. Maybe that’s just how it hit me. And, after all, it was critically acclaimed and earned another Oscar for best actor.

[image error]

[Noah Oppenheim: reporter, author, screenwriter.]

The Venice International Film Festival did honor Jackie for best screenplay. The script is by Noah Oppenheim, rather impressively also the president of NBC News. He’s the former producer of the network’s popular Today Show. A graduate of the Gregory School, a private prep school in Tucson, and Harvard College, he’s a veteran screenwriter as well as a journalist. His previous film credits include the screen adaptation of The Maze Runner; he’s coauthor of a bestselling book, The Intellectual Devotional: American History. Clearly he’s a genius. And persistent: in an essay for the Los Angeles Times, Oppenheim said Jackie was actually his first screenplay, but “in development” for three decades. (Though the actual writing went much faster than that—six years between his first and final drafts, with the last two or three done quickly for director Larraine.)In the Los Angeles Times essay, he traces his Jacqueline Kennedy obsession to his mother:

My mother grew up in a small, two-bedroom apartment in Scranton, Penn. Not a lot of breathing room, let alone storage space for memorabilia. And yet, she saved one box — filled with yellowing newspapers and crumbling magazines, printed in fall 1963.

Over the years, visiting that apartment with my mom, I’d leaf through the fading images of the president’s veiled, heartbroken widow. I didn’t really understand why my mother had saved them. But I knew that this moment in history—and this woman—mattered deeply to her. . . .

I couldn’t shake the feeling that, like so many women in history, her story had never really been told. Sure, she’s been portrayed on the page, on television, even in film. But always as a mannequin, a fashion icon, a beleaguered spouse suffering the indignities of her husband’s infidelities. Never as a fully realized human being. Further, my time covering politicians had taught me one thing—there is almost always a gaping chasm between a person’s public persona and who they really are.

In an interview with Variety, he said the priest braid was actually a bit of dramatic license, derived from letters that Jackie exchanged with priests during the months and year following the assassination. Not a fan of slogging, cradle-to-grave biopics, he chose to focus on the week between JFK’s death and burial, he said in a YouTube interview, believing he could show Jackie’s many sides better through that cathartic prism.

Early on, the movie’s rhythms are slow, with some braids long, almost stately; about two-thirds through the narrative, the climax of JFK’s death is heralded by a staccato delivery of the story’s elements. These late, rapid cuts go like this:

• interview

• funeral

• priest

• funeral

• priest

• SHOOTING

• priest

• funeral

• priest

• funeral

• SHOOTING

• funeral

• SHOOTING

• funeral

• interview

• White House tour redux

The film’s juxtapositions reflect an unreal situation’s component parts, shards of Jackie’s shattered and shattering experience. But we must care about her to feel her tragedy. The Jackie who emerges in Jackie is a woman preoccupied by and keenly responsive to history and to beauty. These two qualities, at the film’s core depiction of her, we sense as true. Her interest in history surely flows at least partly from her historic position; her concern with beautiful furnishings, clothing, and artistic expression helpfully unites her official role, and her allied sense of occasion, with her own aesthetic taste and desire.

Jacqueline Kennedy was an opaque figure Americans saw but never knew. God may not be interested in stories, as the priest claimed, but Jackie sure as hell was; she fed her intelligence by serious reading, and in her last act became a trade book editor. Jackie gives her something precious, her human due: just another person, albeit exceptional, a private someone who merits compassion. How fitting that she’s at last delivered unto us through the alchemy and empathy of narrative art.

[image error]

[She wore her bloody suit all day, wanting “them to see what they’ve done,” assuming that hateful right-wing reactionaries killed her husband.]

[My friend Dave Owen wrote a wonderful essay, “Jackie Consults a Priest,” his take on that element of the film, for his blog Owen at Random.]The post A story structured in shards appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

December 28, 2016

Making life add up in art

Bruce Springsteen’s bio reveals a steel will & a fragile psyche.

Now look at me baby

Struggling to do everything right

And then it all falls apart

When out go the lights

I’m just a lonely pilgrim

I walk this world in wealth

I want to know if it’s you I don’t trust

‘Cause I damn sure don’t trust myself

—“Brilliant Disguise,” from Tunnel of Love

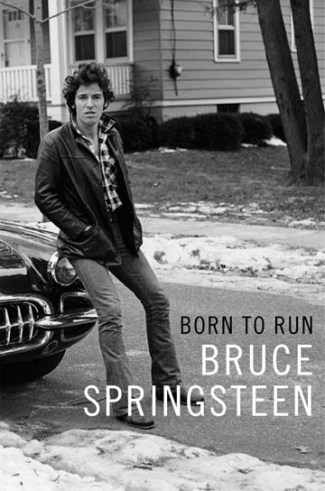

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen. Simon & Schuster, 508 pp.

One of Bruce Springsteen’s horde of mid-1970s fans, I began drifting away from The Boss in the mid-1980s after attending one of his mega Born in the USA concerts, in Cincinnati. Bruce is going for it, the faithful said ruefully. “It” being mega stardom. Here was our feral bard all cleaned up—a clean-shaven hunk with a headband and bulging muscles—finally fit for mass consumption. When he looks back on photographs of himself then, Springsteen says in his recent autobiography Born to Run, he looks “just gay.”

I saw him a couple of years ago at a typically joyous gathering in Columbus, impressed by his commitment to performance and by the endurance of his always-approachable persona. When he backed against a stadium bulwark, a fan reached down from his seat and kneaded Springsteen’s sweaty scalp, twisting his head to and fro, as if mauling a beloved dog. Good old Bruce just smiled and kept singing.

So I was surprised, even knowing Springsteen’s songs, when I heard him say, promoting Born to Run on Fresh Air, that he’s been in therapy since 1983. This was one of the reasons I bought Born to Run. How is that possible for such a beloved man? For rocker so incredibly charismatic and vibrant yet down to earth? For an American success story? What’s the deal, Bruce?

Springsteen answers my question early in Born to Run, revealing the details and circumstances of his exquisitely screwed-up family. And why and how he bore the brunt. But also the curse of depression, and maybe bipolar disorder, that plagues his kin and himself. A figure at once grounded and mythic, Springsteen reveals his behind-the-scenes heroic struggle with emotional baggage and mental illness. That’s his double-whammy, existential and biological. He experienced his father’s rage toward him—and outright contempt—plus he inherited his old man’s disease. Add to that how hard it is just being human, let alone a celebrity, and oh mercy.

The theme of his interior struggle isn’t incidental but, threaded through his massive book, it’s what he’s come to explore and to offer. He’s a good writer—no real surprise—whose prose is conversational and rhythmic. I wished an editor had nixed quotes around so many words used metaphorically and fixed Springsteen’s British usage “amongst,” used always in place of “among,” though a friend who read the book didn’t notice such nits. He shared my frustration, however, with Springsteen’s impressionistic timeline—especially early on, where you want it. Was that watershed gig in middle school or high school?

The matter of Springsteen’s songwriting—the nitty gritty of how he does it—is what some readers will miss. Instead we get his savvy and hyper aware analysis of his work. For instance, I’ve always thought his 1975 breakout album, Born to Run, sounds over-produced, but didn’t expect Springsteen’s confirming verdict on its flawed “bombastic big rock sound.” But, he adds, offering a deeper insight, that’s the dark side of its “beauty, power, and magic.” He’s exquisitely tuned to tradeoffs—he wants it all—and struggles to accept them. Many fans, including me, call that album’s first track, “Thunder Road” our favorite song. Its timeless story opens scenically, amidst a tinkling piano and plangent saxaphone—

The screen door slams

Mary’s dress waves

Like a vision she dances across the porch

As the radio plays

—and the song’s subsequent lines, the successful suitor’s nod to those who lost, helped get him placed on the covers of Time and Newsweek, in the same week, as the future of rock:

The ghosts in the eyes of all the boys

you sent away

they haunt this dusty beach road

in the skeleton frames of burnt-out Chevrolets

He can channel not only the yearning romance of male desire but its murderously destructive dark side, as in his haunting “State Trooper,” from 1982’s Nebraska. Springsteen sings in a Brando-esque sotto voce that he punctuates with psychotic yips:

Maybe you got a kid maybe you got a pretty wife

The only thing that I got’s

Been bothering me my whole life

Mister state trooper please don’t stop me

Please don’t stop me please don’t stop me

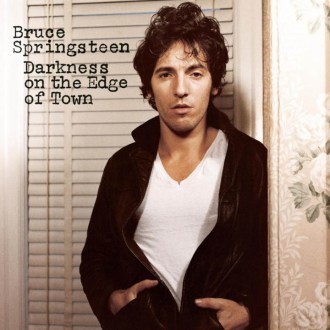

He’s especially good at pairing despair and hope. He does it with the bleak words and bouncy melody of “Born in the USA,” and in lines like these from “The Promised Land,” on my favorite Springsteen album, Darkness on the Edge of Town:

I’ve done my best to live the right way

I get up every morning and go to work each day

But your eyes go blind and your blood runs cold

Sometimes I feel so weak I just want to explode

Explode and tear this town apart

Take a knife and cut this pain from my heart

Find somebody itching for something to start

The dogs on main street howl,

’cause they understand,

If I could take one moment into my hands

Mister, I ain’t a boy, no, I’m a man,

And I believe in a promised land

The mating of words and music, a mystery to most of us, and what makes music such a profoundly moving art form, may be too hard to explain. Does any musician—can any musician—illuminate this? There are hints in Born to Run that Springsteen likes to hole up, immerse. Also that there’s a tension between that and being a family man. He’s demonstrably a steady, hard worker, which indicates a consistent approach. But the core of his process may be intuitive enough that he doesn’t want to jinx it by analyzing it for us. Or maybe it’s usually a slog while clutching a melody or a few lines, too blurry and tedious to explicate.

One thing’s for sure: it’s all he’s ever done. Born to Run reveals that the only other job he ever held was a summer spent as an uncle’s yard boy and neighborhood handyman when he was 15. Playing music in bars was his blue-collar apprenticeship, a genuine if unusual one. Against his father’s scarring rage and depression, his loving mother fed his dream.

Springsteen animates this journey with vivid profiles of his bandmates and others along the way. “Of course I thought I was a phony—that is the way of the artist—but also thought I was the realest thing you’d ever seen,” he says of himself, coming up. Springsteen and his E Street Band aspired to be “understood and accessible,” he says, and that’s his generous effort in Born to Run.

Again, however, there’s always the flip side, where the magic lives:

One plus one equals two. It keeps the world spinning. But artists, musicians, con men, poets, mystics and such are paid to turn that math on its head, to rub two sticks together and bring forth fire. Everybody performs this alchemy somewhere in their lives, but it’s hard to hold onto and easy to forget. People don’t come to rock shows to learn something. They come to be reminded of what they already know and feel deep down in their gut. That when the world is at its best, when we are at our best, when life feels fullest, one and one equals three.

[The Ultimate Classic Rock web site ranks Springsteen’s 20 studio albums from worst to best. Their top three: 1. Tunnel of Love 2. Nebraska 3. Darkness on the Edge of Town. Last October, Springsteen appeared at The New Yorker Festival for a talk with David Remnick.]

The post Making life add up in art appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

December 1, 2016

Dirge for the undead

[Merry Christmas, ya’ll: Christmas trees, Columbus, Ohio, Nov. 30, 2016.]

Hillbilly Elegy: everything he left, can’t explain, but can deplore.

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J.D. Vance. Harper, 257 pp.

J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy has been often cited to explain the white rage that surfaced and was grotesquely showcased during and in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential campaign. Vance’s bestseller is an intermittently interesting if not ultimately cohesive hybrid: part memoir, part summation of sociological reports. Vance’s own bootstrap exodus from poverty is inspiring and even moving. But he doesn’t explain so much as morally indict “hillbillies”—and the “welfare state” that, in his view, has abetted their desultory-unto-criminal ways.

An asset of Vance’s origin is that he can blast his people, as it were, for being shiftless without risking the accusation of elitism. His bluntness can be refreshing. But his lack of deep historical perspective and good solutions troubled me. Beyond the moral of his own story—get lucky with one or two parental figures and work like hell—Vance offers cursory insight into his former culture. This may stem from his getting his own answer early on, in high school, reading studies of America’s black underclass. He saw a direct parallel. In short, the poor will always be with us, so don’t coddle them.

Yet he shows himself, late in the book, having graduated from Ohio State and Yale Law School, volunteering to do try to help stray kids from Appalachia and its broad diaspora. It’s what worked for him, a few random, happenstance interventions, plus his own herky-jerky yet upwardly moving efforts. He writes,

Nobel-winning economists worry about the decline of the industrial Midwest and the hollowing out of the economic core of working whites. What they mean is that manufacturing jobs have gone overseas and middle-class jobs are harder to come by for people without college degrees. Fair enough—I worry about those things too. But this book is about something else: what goes on in the lives of real people when the industrial economy goes south. It’s about reacting to bad circumstances in the worst way possible. It’s about a culture that increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it.

To be clear, the culture encouraging social decay here isn’t the wider culture, the amoral, striving, shiny corporate one that exited with its jobs. It’s the oddly idealistic, flag-waving, blue-collar one stranded in place that’s at fault. Vance derives support for his view from his pathetic mother. As a sensitive child, she was scarred by growing up with raging parents, who’d moved from their beloved eastern Kentucky to dreary Middletown, Ohio, for employment. Maybe that’s why they were so angry—they actually did try to better themselves but had to leave paradise, or at least home, for Ohio. As a current resident, I understand. They got here just before good factory jobs started drying up and Ohio became part of America’s “rust belt.”

At any rate, Vance’s mother makes of herself a nurse, but falls into hopeless addiction. She bounces from one sorry man to another. Eventually Vance is saved from this chaos by being taken in permanently by his crusty, foul-mouthed grandmother, Mamaw. The same woman who, with her husband, by-then estranged, had failed his mother. Mamaw’s the most vivid character in the book, though it’s hard to picture her, or anyone else in Hillbilly Elegy, because there’s scant description and dramatization. Vance’s reliance on exposition harms the work as a memoir, which is to say as literature, but seems to have helped it get viewed as serious nonfiction.

And some of the book’s asides are riveting. For instance, despite its Bible-thumping image, Vance cites research claiming that actual church attendance in Appalachia is very low. And both Cincinnati and Dayton, home to countless Appalachian refugees, also “have very low rates of church attendance, about the same as ultra-liberal San Francisco.” Vance’s discussion of this is interesting in part because of how the phenomenon affected him. His father, whom he never knew growing up, straightens himself out through church, which supports his outreach to his son. Their tenuous relationship helps the boy endure his mother’s shenanigans.

So does school, after his grandmother finally takes him in permanently, in tenth grade, and he begins to apply himself. Which is why his implied support for school vouchers that allow schoolchildren to “escape failing public schools,” rankled me. His hard-knocks conservative and ex-Marine outlook is an asset for the book when he gets to law school at Yale. (Vance served a four-year hitch in the Marines, including in Iraq, before he entered Ohio State as a freshman.) Seeing that bastion of liberal orthodoxy from his perspective is interesting and useful, even if I want to equally credit Yale for acting upon its progressive ideal of diversity in admitting him.

But Vance seems most influenced by what he learned early—from his kick-ass Mamaw, from welfare cheats and lazy workers he encountered in jobs, from studies of inner city black folks. In short, he writes: “the way our government encouraged social decay through the welfare state.” Nobody, liberal or conservative, wants to carry freeloaders. But where’s the balance between that sense of justified outrage and the resentment that led to the utter horror of England’s old debtors’ prisons? (Which largely stocked the Appalachians initially with the British Isles’ downtrodden.) By seeing modest safety nets as superhighways to socialism and even communism, conservatives like Vance can support corrosively anti-democratic measures like school vouchers.

If Vance’s book is, as it claims, an “elegy”— a funeral song or poem for the dead—how can it also be, as its subtitle says, a memoir of a culture in “crisis”? Is the hillbilly dead or is he/she/it living? Obviously it’s alive, and for some time has dwelled in distress. Vance got out, which seems to be his solution. Get lucky, work hard, and get out. He offers scant broader wisdom to his fellow hillbillies, or to the wider culture they might look to for help.

[J.D. Vance explains those he left behind from his home in San Francisco.]

The post Dirge for the undead appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 16, 2016

We can fix a sexist blip

[Kate McKinnon movingly performs Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.”]

Bummer vote, 2016! But our narrative arc trumps this wobble.

As democracy is perfected, the office of president represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.

—H.L. Mencken, July 26, 1920

for Claire

[Mencken: funny anti-populist hater.]

I flipped over journalist H.L. Mencken’s delicious syntax, in 1980, when I was a young reporter at Today in Cocoa, Florida. A few years later, I made a pilgrimage to his lifelong domicile, a rowhouse in Baltimore. Aside from delighting in his sturdy, witty sentences, I found him hilariously hateful to anti-intellectualism. Now, what he warned about our republic’s strain of dumbass Babbittry has come true. All the same, I’ve always been suspicious of his hatred of the “booboisie.” He was an elitist Germanic autocrat, a man blinkered for all his brilliance—he looked kindly upon the rise of Adolph Hitler. And here’s what I keep reminding myself:• Hillary Clinton won the popular vote!

There are two other salient points about the election:

• A lot of it, sadly, involved sexism. Actually I think her narrow loss pivoted on sexism. The narrative that’s winning, of course, is that it was a populist backlash. I agree somewhat, but many wealthy people voted for Trump. First and last, as they know, he’ll protect his class.

• A lot of it, sadly, involved sexism. Who can imagine a man as qualified as Hillary Clinton being so relentlessly hounded and so successfully vilified? Her improperly using a private email server, following the practice of others, is not equivalent to Trump’s actual criminal behavior. Yet she’s demonized as a dragon lady.

As Anthony Lane wrote in the New Yorker, in “Watching the Trump Spectacle Overseas”:

There was far less misogyny on view during Brexit, and less opportunity for misogynistic outbursts; those were reserved for the land of the free. Only now, therefore, is the rest of the world at leisure to stand back and ponder the astounding dereliction of November 8th, whereby the most potent of nations on Earth had the chance to place itself under the guidance and command of a woman, and ducked out.

///

Let’s face it, Barack Obama is uber cool but we know, or suspect, he can also be frosty, as the smartest guy in any room. Hillary lacks his charisma, most humans do, and it may be a long wait for a qualified woman with that characteristic too. Yet we can adore a male political geek. A male Hillary can be reverse-charming. Cuddly even. Give him loving noogies. Bernie Sanders, I’m thinking of you. Though you weren’t as qualified or as realistic as Hillary.

Many streams, many causes, I know. People’s financial plight, terrorist-unto-immigrant alarm, disgust with gridlocked government. But sexism may have made the marginal difference.

Do I repeat myself? Very well, I repeat myself. When over 50 percent of women voted for Trump—and 91 per cent of white Republican women—reiteration’s desirable. I’m not saying women should have voted for her solely because she’s a woman, but they shouldn’t have voted against her for it.

The likely right-wing Supreme Court appointment(s) and the probable loss of progress on fighting climate change upset me. But I return to my original point: a majority of American voters chose Hillary Clinton. Trump lacks the mandate of a landslide. Without the Electoral College—thanks, Alexander Hamilton! Love the brilliant musical, not so much the brilliant Republican—Trump wouldn’t have won at all. As a people, we’ve been trying to move in a gently progressive direction, as befits a nation with such progressive ideals. Our mistakes, tragedies, and setbacks notwithstanding, we’ve stacked up a lot of justice since America’s founding.

Adam Gopnik observed this week in the New Yorker, “Can twenty million people be deprived of medical insurance without consequence? We’ll see. Things slip back, or are forced back—but almost never all the way back.”

Walt Whitman’s populist love song

This is from the preface to Leaves of Grass (1855):

This is what you shall do; Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body.

I side with Walt Whitman, not H.L. Mencken, regarding human nature and the American spirit. Walt! A poet turned Civil War correspondent. A lover of Abraham Lincoln—as we all should be. And gay (probably) before it was: illegal; a mental illness; legal; tolerated; marginally celebrated. Or even a category. Would Uncle Walt lose hope? Nope. No Walt would not.

There’s more to do than water our plants and read Jane Austen, Garrison Keillor’s in the Washington Post notwithstanding. Smarminess is the primary liberal fault—it’s only a secondary flaw for conservatives, who therefore pander more successfully. People hate a smarmy person, as candidate Al Gore appeared to be, much worse than they hate assholes like George W. Bush or Trump. I haven’t yet figured out why, despite working on that puzzle going on 30 years now, but it’s true.

///

About six weeks before the election, I took on a message board of farmers about Hillary. I got massacred. One thoughtful guy, among a phalanx of sexist idiots, mentioned that “liberals look down on us.” Weirdly effective words—hard to refute, and people hate being condescended to. While Hillary isn’t unduly smarmy—probably she’s average in humility for our prideful species—her “deplorables” comment fed that impression and that narrative.

Midway through my internet beating, I wondered why I thought my strong feelings could persuade them? When that mob, literally owners of pitchforks, didn’t have a snowball’s chance of convincing me? Maybe I was being smarmy instead of funny when I told them, “Laugh at the big orange pig. Don’t vote for it.” With my back to the wall, I couldn’t help myself!

But individual temperament, theirs and mine, while a profound matter, may be an incidental here. Another smokescreen for the unquestioned, or even proud, clannish impulses and proud ignorance—you know them by their lack of empathy—that stoke human conflict. And, in truth, I do look down on racists and sexists. But although those issues must be addressed in education and politics, such battles are finally won or lost in each individual heart. And the trend lines are upward. America and the globe, overall and in historical terms, are strikingly peaceful and prosperous.

Here I feel like the little boy found upending the dirty stable, who said, “With all this manure, there’s gotta be a pony here somewhere!” But America is too special and too important to despair just because (not quite half) of our fellow voters gave Trump the barn despite his mountainous preexisting dung heaps. Many Americans have only temporarily forgotten why they appointed Barack Obama to shovel us out after George Bush.

We’ll work, console each other, and vote. We’ll fix this mess. Trump’s a blip.

[Below, President Obama’s historic speech in Selma, on March 7, 2015, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the march across the Edmund Pettus bridge, and extolling America’s evolving effort to bring our flawed actions in line with our highest ideals.]

Barack Obama:

“We are capable of bearing a great burden,” James Baldwin once wrote. “Once we discover that the burden is reality, and arrive where reality is, there’s nothing America can’t handle if we actually look squarely at the problem.” And this is work for all Americans, not just some. . . .

But what has not changed is the imperative of citizenship. That willingness of a 26-year-old church deacon, or a Unitarian minister, or a mother of five, who decided they loved America so much they would risk everything to realize its promise. That’s what it means to love America. That’s what it means to believe in America. That’s what it means when we say America is exceptional.

The post We can fix a sexist blip appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 9, 2016

Dusting off. Moving forward.

[Offutt among his father’s output, mostly porn. NYT photo, William Mebane.]

Chris Offutt’s writing advice resonates as America regroups.

Cast a cold Eye

On life, on death

Horseman, pass by.—tombstone of W.B. Yeats

When Chris Offutt was ten, growing up in an Appalachian backwater, he asked a librarian for a book on baseball. She gave him J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Its writing was a revelation, “personal, told in an intimate way, about family issues of supreme importance.” He never read another book for juveniles, and he became a writer of short stories, novels, screenplays, and multiple memoirs. Back in May, I read Offutt’s My Father, the Pornographer: A Memoir, one of the more interesting books I’ve read this year.

This powerful story concerns his brilliant, driven, awful father. In part, My Father, the Pornographer is a portrait of Appalachian Kentucky. Offutt’s town had a toxic charcoal briquette factory and that was it. He was the smartest kid in school, sometimes beaten by teachers who resented him for that and for his quiet defiance of authority. His Kentuckian father, from a farm in the western part of the state, had picked the tiny company town in eastern Kentucky to be a big-fish insurance salesman. He was that, and increasingly a terrifying tyrant to his children. Especially when he quit his lucrative office work to become a freelance writer. As his oldest child, Offutt got the job when he died of archiving the man’s published and unpublished science fiction, fantasy, and pornography. Literally a ton of novels, stories, and comics. Offutt pere could write a novel in three to seven days.

His secret, parallel 50-year project was the creation of extremely sadistic comics. Sometimes he wrote them for patrons, wealthy collectors. Other than a brief description of these comics, the memoir is not unduly graphic. But it’s sad and disquieting. What Offutt endured from his father and this environment turned him toward literature. But he grew up with the permanent wound of feeling unloved. Part of the book’s brilliance, saturating its deft syntax, content, and structure, is that it escapes self-pity while making you feel for Chris’s experiences and what seems his ongoing burden. The New York Times Magazine ran an excerpt.

[Offutt – Buzz Orr photo.]

Offutt writes about his long, bruising writing apprenticeship in an essay, “The Eleventh Draft,” collected in a book by that title, edited by Frank Conroy, and which I found online as a pdf. In it, he tells the story of the librarian handing him Catcher in the Rye. After leaving Kentucky, he worked part-time jobs around the country for almost a decade, and wrote an average of 30 pages a day in his journal. He explains:Writing is the most difficult task I’ve ever undertaken, which is perhaps why I do it. For much of my life, I cared about little except the act of writing. Writing taught me to trust myself, which enabled me to trust others. This resulted in marriage, and within a year my wife convinced me to apply to an MFA program. I did so reluctantly and with no alternative. We’d moved back to Kentucky, where we were living without benefit of plumbing, heat, or jobs. The summer I turned thirty, we borrowed a thousand dollars and headed for Iowa. This decision literally changed my life.

“The Eleventh Draft” takes us through his process, including his learning to love revision. Today, his average short story takes ten or eleven drafts over two years; one took 35 versions over eight years:

The move to revision became so complete that I no longer cared about the story as a product. What mattered was the evolution of the act of creating. I spent many joyful hours merely shifting material from one narrative to another, gauging the success of the integration, attempting greater risks on the page. Plot was a loose form I could rely on in the same way that poets might utilize a sonnet or a villanelle. . . .

The only way I can create anything worthwhile is to concern myself solely with the moment, to maintain as much freedom as possible during the interaction between my mind and a narrative. This has led me to write what I need to write, instead of what I want to write. My work, both fiction and nonfiction, is about my current emotional state, my past behavior, and my recent thoughts.

Offutt’s essay is one of the best accounts of learning to write, and what writing teaches, that I’ve ever read. It affirms that, as for me, writing is hard. Especially when I lose faith in the process. Or receive a painful rejection, as I did last week. But as Offutt reminds us—and as anyone knows who has written anything worth reading, whether an office memo or an epic poem—writing takes recursive effort. Maybe it takes caffeine and chocolate too. It sure did for me today, along with bowls of pinto beans simmered with smoked ham hocks—Mom’s proven answer: life goes better with soul food.

Then, back to work. And try to be wise about victories and setbacks. The work may weary you, its outcome disappoint you, its reception pain you. But only action, not brooding, will lift you from the hole you’re in. If quitting is your answer, did you truly believe, which is to say love, in the first place? At base, worthy belief arises from love. Greater than egoistic rage or grinding duty is love. That must come first. And, if it began there, that’s where it must continue. That’s my hope for myself and my work and for our nation and its work.

[Hillary Clinton before Detroit rally, Friday, Nov. 4. NYT photo, Doug Mills.]

The post Dusting off. Moving forward. appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

November 2, 2016

The case for Hillary

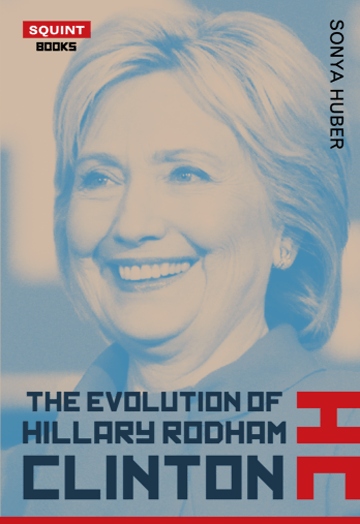

The Evolution of Hillary Rodham Clinton by Sonya Huber. Eyewear Publishing, 188 pp.

Puzzled by her aversion toward Hillary Clinton, former Bernie Sanders supporter Sonya Huber accepted an offer to quickly write a short book exploring why. In The Evolution of Hillary Rodham Clinton, Huber assesses fair and unfair criticisms of Clinton. I found Huber’s look from the Left balanced and interesting—and, more to the point, useful. With her historical overview, Huber clarified my own mixed feelings as a moderate progressive. The bottom line, however, is that we’ll both be voting for Clinton. I’ll be doing so with more confidence after Huber’s inquiry, which convinces me that the false narratives that dog Clinton do cloud our view of her.

Huber teaches creative writing at Fairfield University and in the low-residency MFA program at Ashland University. Her books include: Opa Nobody, about her German grandfather; Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir; and the forthcoming Pain Woman Takes Your Keys: Essays from a Nervous System. She has worked as a reporter, but also, in her long journey toward writing and teaching writing—and obtaining health care—in a range of jobs including working as a waitress, trash collector, gardener, nanny, dishwasher, video store clerk, canvasser for an environmental organization, labor-community coalition organizer, receptionist, and mental health counselor. She blogs about a range of topics, including her struggles with autoimmune diseases, and recently about the Clinton book in “How to Write a Book in Two Weeks.”

I’d forgotten so much that Huber reminds me of, including Bill Clinton’s conservatism as a “New Democrat.” In the wake of Ronald Reagan and under pressure from a new breed of militant conservatives, Bill sought to out-Republican the Right. As Huber puts it,

This was Jimmy Carter with brass knuckles, a party that had to get tough to rescue the southern white male vote by promising to enforce a series of belt-tightening bootstrap policies that would end up glorifying the Republican ideals of free trade agreements, destroying welfare, and enacting an era of mass incarceration in the name of a War on Drugs.

Bill appointed Hillary as chair of the Task Force on National Healthcare Reform, making her the public face of the effort. This was an unusual move, and Huber’s research indicates that Hillary was far from the plan’s architect though she was demonized by the GOP and left holding the bag for the initiative’s failure: “It’s amazing, really—the evil power that this narrative has given her. It wasn’t profit interests that derailed healthcare reform: it was a woman.” Afterward, Hillary worked with Bill, Teddy Kennedy, and Orrin Hatch on a successful bipartisan effort to expand healthcare coverage for low-income children.

Republicans took the House in 1994, and Newt Gingrich became their angry spokesman. They briefly shut down the government to force President Clinton to agree to cuts in basic social programs. Soon Clinton signed a bill enacting harsher penalties on violent crime and another to reform welfare. The crime bill is blamed for today’s high level of incarceration, and in supporting it, Hillary used the “super predator” phrase she has apologized for. She does have a long track record in public service, which seems to get used against her more than for most politicians.

On welfare, Bill Clinton was under pressure but also had promised reform. While he vetoed even harsher Republican welfare bills, the president’s own reform replaced a coordinated federal program, Aid for Families with Dependents and Children, with an easily cut block-grant system to states. Hillary supported but helped buffer it. But this, Huber writes, “effectively destroyed the New Deal-era safety net of welfare in 1996.” In Huber’s view, Bill’s initiative and Hillary’s subsequent cooperation with GOP welfare reforms continue to hurt her with the Left; her current positions would roll back “pernicious elements” of her husband’s initiatives:

Part of the greater concern among progressives is the extent to which Clinton is willing to use right-wing language to make incremental changes in bad legislation and the extent to which she believes New Democrat neoliberal rhetoric that imposes punitive restrictions on the poor without investigating full implications.

Her moderately progressive inclinations or her political pragmatism haven’t lessened the Right’s visceral hatred for her, much of which Huber and the sources she quotes in The Evolution of Hillary Rodham Clinton attribute to sexism—on the Right and the Left. Her “continued involvement in politics is astounding,” writes Huber, considering she has lived with concocted scandals and intense scrutiny and criticism for decades. “At a personal level,” Huber adds, “delving into her substantial backstory has convinced me that she will be a competent leader who will not be embittered or stunned at any point by the horrible game of politics in Washington or on the international stage, and I think that’s a necessary qualification for the position of president.”

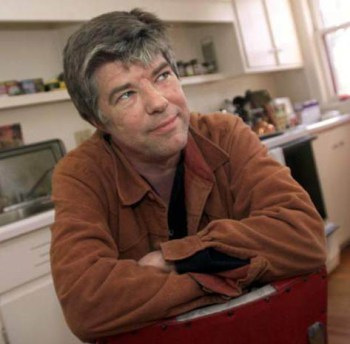

[Sonya Huber, existential journalist.]

Hillary Clinton is inclined to be an interventionist, a hawk, Huber concludes, perhaps influenced by mass killings in Rwanda and the Bosnian war during her husband’s presidency. While this concerns Huber, as it does me, my sense is that plenty of voters fear she won’t be tough enough because of her gender. As I write this, polls and pundits seem unsure of the presidential race’s outcome. Partly is this uncertainty the media’s interest in a close horse race? Mostly, I sense, with Huber, that along with the retrograde and unexamined sexism toward Clinton is “anti-establishment resistance to her domestic and international connections.” This is much of what fueled Bernie Sanders’s support on the Left, of course.For a wider perspective, Huber consulted books, including Hillary’s, and read many articles in researching The Evolution of Hillary Rodham Clinton. With Sanders gone, her book makes clear, populist backlash could still find expression through a Trump vote. I hope some of his angry supporters will melt away, and hopefully Clinton’s base will turn out. I’ve been telling my wife that the “sweet little old ladies” we know—Republican and Democrat—represent a nationwide bloc that’s going to see its way through the murk and throw the election to Clinton. They vote, and they’re not single-issue voters. They do, however, possess the wisdom to shun a man who isn’t a gentleman, knowing such bad character is indicative.

I’ll give Huber the last word regarding what to expect if and when Hillary Clinton is elected:

She doesn’t go in for grandstanding. In fact, she’s controlled because we’ve made her that way. We think we know what we get with Hillary because she has been tested on the national and international stage. At the same time, the presidency itself might allow her a new latitude to be open about the agendas she cares about. The big show for Hillary might be very different than we have imagined it to be.

The post The case for Hillary appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 26, 2016

She wore white

[Clinton: radiant with ideas & conviction in the final presidential debate.]

Hillary Clinton bravely faces Trump & the forces of darkness.

The journey of women, like America’s journey, is always evolving toward equality and social justice.—Meryl Streep, narrator of Shoulders: Hillary Rodham Clinton’s Story, below.

By the final presidential debate, who could deny that our nation’s howling retrograde armies have assumed the bodily form of Donald Trump? In the face of ignorance and evil, Hillary Clinton acquitted herself almost flawlessly and looked fantastic. Her white suit alluded to the long struggle by women in America for equal treatment—and thereby stood, as well, for justice for all. In contrast, Trump was his usual vile self, and the Women of the House of Trump dressed in black—Melania capping her ensemble with a “pussy-bow” blouse, as if to refer dismissively, from the summit of haute couture, to her husband’s vulgarities. Symbolism has never had it so good.

[Darkness visible: Trump’s Women go marching in.]

There’s been so much inspired ink on what Trump’s surprising level of support means. The dominant narrative, of course, is that it springs from economic pain among America’s middle- and lower-middle classes. But clearly in this backlash there’s also a strong racist, sexist, misogynistic, nativist, homophobic component. Trump’s sole gift as a leader may be, in stirring the embers of fear and pain, to kindle rage.As a progressive who fervently believes in American exceptionalism, I’m worried. A proven cure for angry, unexamined feelings is education, which leads to consideration of others’ viewpoints and to self-inquiry, but that’s a slow process.

This week’s New Yorker brings comic relief of sorts with an entertaining analysis of Clinton, Trump, and their campaigns’ supporting players by historical novelist Thomas Mallon. He outlines what he’d write about the campaign in a novel he’d call Presumptive. With Trump barely two-dimensional—a “flat character” in fiction’s lexicon—he doesn’t merit Mallon’s serious consideration to carry the novel’s point of view. Clinton, of course, does. But right off the bat, Mallon hits his hardest, darkest note regarding her:

If Nixon was shredded and poisoned by each of his pre-Presidential defeats, Hillary died a little with each of Bill’s victories, one after another, in Arkansas and beyond, all of them forcing her to stand at a spot on the stage that she knew she should not be occupying. Her life was supposed to take place behind the lectern, not beside it, hoisting the hand of the man who’d just got the votes.

By the time it was “her” turn, it was psychologically too late, just as it was for Nixon in 1968. In his case, winning could not make up for losing; in hers, fifteen years of jury-rigged self-fulfillment cannot make up for the previous twenty-five of self-suppression and worse.

In going with the unoriginal Clinton-is-Nixonian metaphor, Mallon inflates a minor observation into a risky and false-feeling note in an otherwise savory essay. I do agree she’s better than Bill—as a person: but that dawg Bill was a successful president, and she hasn’t pulled that off yet. As well, the sexism she faced, if nothing else, impelled the couple to take turns. Did waiting and racking up political triumphs—becoming a stateswoman—really kill her soul?

Wary and inscrutable do not equal warped. She faces a white tycoon who bleats how the system is rigged against him. Why? In large part because he faces a “nasty woman.” Can anyone imagine Hillary Clinton having survived with even half his record of mendacity and infidelity? With children by three husbands? A string of business swindles?

So, yes, she’s cagey after three decades of far-right assault, most of it as absurd as her opponent.

[Clinton blinded Trump, who failed to make his dirt stick.]

As for Clinton’s steely pragmatic nature, similar doubts might’ve been sounded about Abraham Lincoln, who worked as a tough, amoral lawyer. He represented a railroad. Who could have predicted his rise to personal and political greatness? That is, besides pretty much the entire South?So Lincoln gives me hope. He knew—and the South knew—what his election would mean. The first assassination attempt on Lincoln’s life came on his way to taking office. Idiots still debate whether the Civil War was “really about slavery, and whether Lincoln “really cared.” What’s true is that he grew in office. It was as if America produced him; in doing so, the union preserved itself and removed one of its last impediments to greatness.

We can’t know whether or when America will need to produce such a person again. But Trump’s depravity makes this moment feel like Armageddon. Clinton, resplendent in her white tunic, has shown considerable courage in facing this rough beast unleashed by dark forces. Never mind her secret soul—who most fears Clinton’s effect on America’s historic and evolutionary destiny? Trump’s supporters.

Clinton is an incrementalist who faces a number of intractable problems caused by previous politicians, of both parties, and by human nature itself. I believe she can grow, as she has in the past. I’m certain Trump cannot. And, moreover, that he’d harm America for decades through bad appointments. Since I got over my own unexamined sexism regarding Clinton—that maybe she’s not “nice” behind the scenes, when my standard for male politicians was much lower—I have only one concern.

She’s hawkish for my taste. Her vote for the Iraq war was the biggie. Out here in the hinterlands, I saw George W. Bush’s crime-in-the-making for what it was. Why couldn’t she? But at least she’s admitted her error. Moreover, Barack Obama’s Lincolnesque move of appointing her as Secretary of State, after they’d been such bitter rivals, not only grew her as a stateswoman—as he intended it to—but surely grew her as a person as well.

This week’s issue of the New Yorker features an eloquent endorsement of Clinton, “The Choice.” Its weakest aspect comes in addressing my concern, vaguely hoping she has “learned greater caution” in military matters from Obama. Though it spends much time thumping her unworthy opponent, the essay otherwise makes a good case for Clinton’s tax plan, her economic development policies, and her likely restoration of moderation to the Supreme Court. Clinton, like Obama—and, for that matter, her deeply flawed husband—appears to understand America’s march toward a sacred horizon.

Belief in America is part and parcel of my own hard-won sense of our species’ spiritual destiny. But will we ever get out of the weeds? Maybe this is what democracy is about after all, a series of crossroads. Maybe it’ll take 2,000 years to get everyone on the same page. Maybe “Amazing Grace” is right—it’ll take 10,000. Until then, I guess, it’s baby steps. Now each side—one mildly progressive, one violently regressive—has presented to us its avatar. We must choose one or the other.

Through many dangers, toils and snares,

I have already come;

’Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far,

And grace will lead me home—“Amazing Grace”

The post She wore white appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 19, 2016

The noble Bob

[Many guises: During 1975’s Rolling Thunder tour, when I first saw him.]

Bob Dylan’s genius & oceanic body of work.

He not busy being born is busy dying.—Bob Dylan, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1965.

Bob Dylan’s work is like barbeque or Mexican food—some is better, but it’s all good. It was news last week that he got the Nobel Prize for literature. It hasn’t been news for a long time that he’s a genius. But then, genius is simply brilliance plus output. Then again, he’s a genius among geniuses. I count it as my good fortune to have lived during a time when an artist on the order of William Shakespeare has been belting it out for us.

He’s written timeless gems like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are A-Changin” and surreal masterpieces like “Desolation Row” and “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” and born-again testaments like “Slow Train Coming” and “You’ve Got to Serve Somebody,” along with too many love songs to count. He created one of my favorite sub-genres: his own spooky Mojave stories like “All Along the Watchtower,” “Senior (Tales of Yankee Power),” and “Man in the Long Dark Coat.” And, always, shooting through everything, the blues.