Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 9

June 17, 2015

Q&A: Monica Wood

[Monica Wood of Maine.]

Recently I reviewed here Monica Wood’s When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine. Afterwards, she agreed to answer some questions for Draft No. 4.Q: In an interview with Lisa Shirah-Hiers for Story Circle Book Reviews, you said about the memoir genre:

I teach memoir writing now, and I don’t think I’ll ever go back to teaching fiction. I’ve seen first hand the power of speaking stories aloud, of simply putting on paper the tragic or ordinary or quirky or mundane. I teach in a women’s prison and I see every week how their stories not only make them reflect on who they are, but how their stories connect them to one another in a place where human connection can be really risky.

Could you elaborate on memoir’s “for the people” aspect implied here—the personal benefits of examining one’s life in written story—in relation to memoir as literature? Some critics seem to get irate when people they view as amateur, non-literary types publish their stories. For example, last year in the Washington Post Jonathan Yardley unloaded an anti-youth, anti-memoir, anti-MFA screed in a review of 34-year-old Will Boast’s memoir Epilogue. The issue won’t die. Recently there were columns by Leslie Jamison and Benjamin Moser in the New York Times Book Review on “Should There be a Minimum Age for Writing a Memoir?”

I think you’re making the distinction between writing that serves as catharsis for the writer alone, and writing that aspires to speak to the human condition universally. Catharsis is a perfectly valid reason for writing, and I recommend it. But there’s a difference between writing a book and publishing a book. Although the Yardley screed seems awfully mean, I know what he’s getting at. I haven’t read the memoir in question, so I offer no opinion on Epilogue, but I have read a few memoirs by both young and older writers that make too little effort to look OUTWARD.

Good stories—fiction or nonfiction—allow us to look both inside and outside ourselves, allow us to connect to human experience at large. Older writers do this more naturally, perhaps, simply because they’ve lived longer and had more experience with the universal. But young writers can also do that (Dave Eggers’s first memoir laid me flat). All I can honestly say on this subject is that the memoirs I like tell a personal story in the largest possible context. The memoirs that bore me read like “a series of unfortunate events” with no shape, little insight, and not much effort to reach beyond the deeply personal. And, of course, the writing has to be good to keep me engaged. Sometimes the writing alone can hook me in a story I’m not especially interested in.

Q: Related to the above question, I have been thinking about a paradox. In teaching my “Writing Life Stories” class to upper-level college students, after I show them some great essays, underscore technique, and they write (and rewrite), many students produce artful memoirs. Most of these kids aren’t English majors. They might struggle to write a decent short story, and most wouldn’t want to try, but they get the artistic dimension of personal nonfiction. In your teaching, have you found this to be true as well? What techniques of writing memoir do you emphasize?

When teaching the art of memoir writing I often focus on two elements: story structure, scene, and the management of time/event. And narrative voice. That’s a big one and so, so, so hard to teach. It’s important to bring the reader into the world of the story by choosing the right narrative voice, which is a fancy way of describing word choice, syntax, verb tenses.

So much of a successful narrative voice comes down to the basic elements of grammar and usage. “He had ranted for two days about the new dog” is less intimate than “he ranted for two days about the new dog,” and far less intimate than “It’s been two days and he’s still ranting about the new dog.”

And it’s also difficult, if you’re writing a childhood memoir, to get the right balance of old-young. You want the reader to experience the childhood event, but not be limited to a child’s perception/vocabulary. So I went with a high/low hybrid, i.e., a child’s sensibility in an adult’s vocabulary. One example: “The Vaillancourts were catless but otherwise without flaw.” That’s a kid’s observation, but rendered in an adult’s knowing voice. There are three layers to this sentence: the kid’s innocent perception, the dispassionate writer’s wryness, and the adult child’s warm memory.

Q: What challenged you in shifting from fiction to nonfiction in writing When We Were the Kennedys? Did the learning curve apply—that is, even things you’d mastered were harder? I’m especially interested in how you worked out your storyteller’s persona, which fiction writers tend to call voice.

Yes, that was a challenge, one I welcomed. I love nothing more than a narrative problem to solve. I wrote an entire draft, 300 pages, in a past tense, journalistic, essayish voice, which didn’t work at all. Not until I started applying fiction techniques (scene structure, dialogue, etc.) did the story begin to feel real. And I must add here that I did not make up anything. No composite characters, no altered chronology. The shape came from what I left out, mainly.

Q: My wife and I were fascinated by your depiction of the impact of the Kennedy assassination on your own Irish Catholic family, and especially on your mother. For those of us in your generation, time stopped that weekend. Your memoir rekindled the national trauma for us and made us realize how personal responses to it were. Was this event’s ripple effect in your life a major thread from the beginning or did the parallels grow in writing?

The parallels did grow, in the exact way that “theme” appears very late in the writing of a book. At first all you do is write and remember. Then you discover the recurring motifs, the big moments, the controlling metaphors that make a story more than itself. For me, the assassination was one (the sudden death of a father figure) but the really big one was the paper mill; in fact, I call it “my first metaphor” in the book. An omnipotent, ever-present entity that had the power to give and take.

Q: You’ve recently added another genre to your oeuvre with the production of Papermaker, cast in Maine and New York and performed in Portland this past spring. It’s set during a strike at the town’s paper mill, and described on the theatre’s web site as a “revealing drama about family, loyalty, and the quiet tragedies of mill-town life,”which sounds a lot like your memoir! How did your writing a play come about?

The premise of the play came from an earlier book of mine called Ernie’s Ark, then diverged quite a bit once I began writing scenes. I LOVED writing drama. I’ve always been a theatergoer and I’ve always wanted to try writing a play. This one came so naturally, and I loved the challenge of telling a full, rich story with only one tool: dialogue.

It was both confining and liberating at the same time, hard to describe. The collaboration with actors and a director was the best part of the whole experience. After typing in a room for 20 years I was ready for it.

The post Q&A: Monica Wood appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 9, 2015

Shepherd: A Memoir named 2015 Ohioana Book Award Finalist

[The Big House at Malabar Farm, Lucas, Ohio, outside Mansfield.]

Reflections on Louis Bromfield, hospice & great indie bookstores.

[Louis Bromfield & friend at Malabar Farm.]

The Ohioana Library Association has just announced that Shepherd: A Memoir is one of five finalists for the 2015 Ohioana Book Award in Nonfiction. I was and remain surprised and grateful. The north doesn’t get behind its books, not the way the south does, but the Ohioana Library Association has always been a shining exception to that feeling.The association established its awards in 1942 for fiction, nonfiction, books about Ohio or an Ohioan, poetry, and juvenile literature. Even if your book is not eventually nominated for an award, the good folks at Ohioana will note it in their Ohioana Quarterly if you or your book touches on the Buckeye State. When I was marketing manager at Ohio University Press/Swallow Press, I sent Ohioana a boatload of books. Our authors received thoughtful reviews in return.

I treasure Shepherd’s review in Ohioana Quarterly last October, especially its phrase, “The ups and downs of Gilbert’s farm projects coincide with a deeper reflection on the poignant dilemmas common to all humankind.” Above all, a memoirist likes being told he’s not narcissistic.

The Ohioana honor caps a season of firsts for me and Shepherd. This struck me in May, driving into northern Ohio to give a reading. I had just received the “Spirit of Hospice Rookie of the Year Award” from Hospice of Central Ohio. I’d undergone training as a patient companion the previous spring, and my bedside visits had changed me. At first it surprised me that no one seemed curious about my work with the dying. I’m sure I was the same way. Death is messy and scary, and my own issues with it were one reason I volunteered. And what I’d learned is that helping in hospice isn’t depressing. That the dying are still just people, no different from you or from me. Except a doctor has made official their imminent mortality.

One reason for my hospice work had been to widen my sphere—in a time when my life and my wife’s seemed to revolve exclusively around our work at Otterbein University. And Hospice was a natural venue because of its service during my mother’s terminal illness. I was beginning to see another connection between joining hospice—just as my book was published—and my mother. She did not live to see Shepherd, but she had helped me with it. I read passages to Mom in her hospital bed. Ever the sharp editor, at one point she said, “There’s something wrong with that sentence.” She was right.

A great indie bookstore in Mansfield, Ohio

[Llaylan Fowler and Ben Madden at their bookstore.]

As I drove that glorious afternoon on the way to the bookstore, I savored the season. It was May 1, neither early nor late spring. As always I marveled that the trees weren’t yet fully leafed. But a golden-green haze blurred the domes of the woods. After months of looking at gray-brown bark, my eyes lingered on the soft new buds adorning the roadside trees. I was bound for my book’s ultimate venue: Mainstreet Books, in Mansfield, Ohio. Mansfield’s most famous native son, Louis Bromfield, was a hero to me as I grew up in Satellite Beach, Florida. He showed me how I might redeem the loss of our family farm in southwestern Georgia. I write in Shepherd about stumbling across reprints of his books as a teenager:Sometimes, curled up with the chunky mass-market paperbacks in an overstuffed chair in our Florida room, I ached with my sense of loss. When I excitedly showed Dad my books, surprise flickered across his handsome, impassive face—The Great Stone Face, a brother would one day call it—and he pointed out the hardcover originals in his library. Bound in black cloth, they were embossed with a red Harper & Brothers logo that showed a torch being passed from one had to another.

[Cover of the 1970 paperback reprint.]

Though the Pulitzer he won as a young man was for fiction, Bromfield’s books on farming in tune with nature, especially Pleasant Valley (1945) and its sequel Malabar Farm (1948) are Bromfield’s literary legacy. He won an Ohioana Career Award in 1946—just as his farming phase got started and ten years before his death.Ohioana’s web site offers a fine essay, “Louis Bromfield’s Cubic Foot of Soil,” by David D. Anderson, about the writer-farmer-conservationist’s career and importance. Anderson pegs Bromfield’s appeal when he calls Animals and Other People, published in 1955 when Bromfield was ill with the cancer that would kill him the next year, “a remarkable re-creation of Malabar, its people, and its animals, and the mystic rather than rational ties that unite them.”

Bromfield wrote impressionistically, with sensory details and bold strokes, as if painting murals for friends in a cozy bar after a few drinks. The roots of his hunger for a bountiful, holistic life are explored in Ellen Bromfield Geld’s memoir The Heritage: A Daughter’s Memories of Louis Bromfield. It is lyrically written, a loving yet honest portrait of a man with epic ambitions and a forceful personality. These qualities both attracted and alienated others. The Heritage won an Ohioana Award in 1963, and Ohio University Press returned it to print in 1999 when I worked there.

Driving into Mansfield in the glory of Ohio’s burgeoning mid-spring, now pushing my own Bromfield-esque book and hosted by an independent bookstore, my belly was full of good fortune. Arriving early for the event, I ate a piece of blackberry pie in the diner beside Mainstreet Books. The old downtown and the diner took me back to the first job I landed after college, as a newspaper reporter in the north Georgia mountain town of Dalton. There were two eateries in downtown Dalton, the U.S. Café and the Oakwood, each with its loyalists.

[Poster in the Mansfield bookstore.]

My sense of déjà vu deepened when I met Llalan Fowler (“Laylan”—the name is Welsh, after a great aunt who lived in Scotland) and Ben Madden, the bookstore’s young managers. Bromfield had excoriated Mansfield in fiction for its money-grubbing crudity, and now their bookstore is a cultural oasis there. I felt nostalgic. If you are doing anything interesting and creative in such a place, you meet everyone else who is. I’d been an actor in Dalton Little Theatre—“entertaining Georgia since 1869”—and from that, my newspaper work, and classes at a karate dojo, I knew an interesting bunch of people. Here in Mansfield was a sense of young folks lined out on good paths. And making a difference in their town. It felt good to think of such people busy in burghs across the republic.The shelves of Mainstreet Books hold a thoughtful and surprising selection; the store regularly hosts authors, musicians, and ice cream socials. Llalan and Ben made their way back to Mansfield after college and various jobs—he started at Ohio State, went to Oklahoma and Denver, and she studied English at Ohio University and worked in bookstores in DC, Boston, and New York.

Llalan’s parents attended my reading, along with some of her friends from high school days—others who had returned to Mansfield after college. One young woman listened thoughtfully, eating her takeout pizza while taking notes—clearly for her own work, clearly a writer. Another woman was interested in gardening and animals and finding a paying farming sideline for the acreage she’d inherited. A clergyman wandered in and asked me about agrarian author Wendell Berry.

As Bromfield himself said in one of his farming books, it’s amazing what people can accomplish when they finally settle down and dig in. We seldom see our glory days as they happen. But if we’re lucky, one day we know they’re always happening now.

[Found poetry on the bookstore’s typewriter: “threre is a strangeness about mansfield, ohio. wanting for the beginning of something hopeful”]

The post Shepherd: A Memoir named 2015 Ohioana Book Award Finalist appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

June 5, 2015

Memoir pro & con

Positive energy is the best energy, certainly the most sustainable. But we must admit the opposite is also true. There’s an odd power in negativity. A roomful of happy folks can be cast into quiet doubt by one vehement naysayer. And yet, when negativity goes too far, as Jonathan Yardley appears to do in his review for The Washington Post of Will Boast’s Epilogue: A Memoir, it kindles defiance in turn. Going beyond what he views as Boast’s inadequacy, Yardley unloads on memoir, youth, and the MFA.

He makes me want to read the book. It’s about how Boast, at age 24, is left alone in the world after his father succumbs to alcoholism—his mother and brother having already died—and he discovers that his father had sequestered a wife and two sons, Boast’s half brothers, in England. The memoir comes highly praised for its artistry, and that’s a clue to Yardley’s choler.

At first I assumed his pique was about amateurs, non-literary types getting their messy life stories into print. Then I realized it was allied to that, not not that entirely. Yardley’s broadside in large part reflects the difference between the world of New York trade books and the world of literary academic books. The camps are permeable—as Boast himself shows, winning a New York imprint (Liveright, his publisher, is a division of Norton)—but they’re very different. And Boast has the gall to straddle them: a trade publisher and artsy content.

A year after Yardley’s broadside, it appears to be the proximate cause of two interesting recent columns, “Should There be a Minimum Age for Writing Memoir” in the New York Review of Books’ series Bookends, where two writers opine on opposite sides of some divide. One is by artistic-but-commercially-successful Leslie Jamison, a red-hot writer for her essay collection The Empathy Exams. She’s also a friend of Boast’s. The other is by Benjamin Moser, who doesn’t attack the genre, either, but tries to place it in distilled historical context. In his somewhat inscrutable essay is this gem:

Every event, and certainly every event worth writing about, will always remain tattooed on our neurons. So it is never too early to start giving those events, which are our lives, a form. It is a homage we pay ourselves. More solid than a memory, a memoir will outlast it, because until a memory is put into words, it remains mist, never shore.

I agree, of course. Everyone’s a critic, but let it be noted: a critic’s first insight isn’t always the best insight. One of the objections that occurs to almost every untutored someone (after “Isn’t creative nonfiction an oxymoron?”) is that almost no one—and certainly no young person—has any business writing memoir. Nonsense. Quite the opposite, actually. Maybe a gifted writer so inclined should publish three right out of the gate. And leave plenty of room for her middle-aged reflections, plus late thoughts into senescence.

That’s obviously not Yardley’s view. And his froth tips the crest of a roiling memoir backlash by lesser literary lights. I stumbled across Kara Brown’s “Delete Your Memoir” recently on Jezebel. It isn’t worth quoting, and the title says it all anyway. No one cares about you and what you want to share. Give up.

In contrast, my student, Amanda

Which raises the question of whether such folk are even close to speaking wisdom. What part of their psyche brings us such snarling? My guess would be the ego, which wants and fears, as Eckhart Tolle succinctly puts it. I’d add, “It’s ego’s desire for attention plus, from our primate substrate, the ugly urge to dominate.” (Brassy-unto-angry folk bypass six million years of kindly, group-mind hominin evolution. See Carl Jung on the collective consciousness. Or, in contrast, experience the behavior of most drivers in any big American city.)

I can’t help but think of a girl I taught recently. I’ll call her Amanda, because that was her name. (There were three or four Amandas in my classes last school year—all smart and nice, FYI.) This Amanda was the sweetest kid in the sweetest bunch of freshmen I taught last year in a certain class at Otterbein University. When we workshopped memoirs—yes, I had 18-year-olds writing memoir essays. Multiple times!—she was riveting to watch. As she spoke to another writer, Amanda seemed to be re-experiencing the writer’s story; with her eyes on the writer, her gaze somehow went inward. She made suggestions, which I required, but this shy girl glowed. An old-soul joy suffused her face.

Soon I learned to watch the faces of the writers she was speaking to. They studied her, guardedly but hungrily, and unguarded emotions swept their faces. They radiated an ephemeral amusement of their own, in Amanda’s, and a profound respect for her tender, egoless grace.

Daisy Hickman on memoir’s ‘curious place in literary conversations.’

[Daisy Hickman: wise mind.]

So many memoirs are under way, and so much is being written about memoir. Haters gotta hate, but I find this foment interesting. So many voices, so much passion, so many steps forward into discovery. Into greater wisdom, deeper peace.At her web site, Sunny Room Studio, my virtual friend Daisy Hickman is a master of life’s and memoir’s spiritual dimension. Her recent blog post “Learning to Write” explains how, in her second memoir that’s well under way, she weaves in apple trees—the three outside her grandmother’s window she loved as a girl; the three, which had been tended by her late son, who died at age 27, that she treasures today. In figuring out how these trees connect, she quotes the late William Zinsser:

Write about small, self-contained incidents that are still vivid in your memory. If you remember them, it’s because they contain a larger truth that your readers will recognize in their own lives. Think small and you’ll wind up finding the big themes in your family saga.

Daisy explains where reflecting on this advice took her. But she adds this:

Here’s the thing about writing a memoir — it’s extremely challenging. When working in the captivating land of memory, emotions, and time … how could it be otherwise? There is much to write about, yet, paradoxically, there is little to write about. As writers, we have to tease out milestones, memorable dialogue, fading landscapes sketched somewhere in our mind, and then we have to discover the relevance of this — to ourselves, to those who eventually read our books.

Having worked on this memoir for almost seven years, since the publication of her Always Returning: the Wisdom of Place, Daisy has some wise-mind lessons to impart. She’s worth listening to here about memoir and memory, about loss, and spiritual gain. So is her newest entry in this series, “Never Orderly,” on breaking the rules of memoir. As Daisy puts it so well, memoir “holds a curious place in literary conversations.”

As someone who himself has struggled to learn the conventions of literary memoir, and to teach them to others, I find her inclination to break its rules exciting. Marveling at Daisy’s journey in these two posts, I happened across an essay at Glimmer Train by Lisa Gornick, who has added memoir writing and teaching to her quiver, alongside fiction and psychotherapy.

Gornick explains:

For the past century, the emblem of the journey into self-discovery has been the psychoanalyst’s couch, but preceding Freud and the consultation room lies a history of personal essayists, leading back to Montaigne in the sixteenth century, who have shone unsparing light on their own thoughts, emotions and desires. Indeed, a person embarking on writing a personal essay and a person embarking on a psychotherapy share many aims: a desire to tell a story, to penetrate the surface to reach a liberating meaning beneath, to feel enlarged by experience such that the tabloid account is transformed into something poetic and mythic. The material, though, needs to be harnessed: both essayist and patient must gain sufficient control over their emotions and automatized ways of thought to step back and reflect, to not succumb to the countervailing forces lobbying for secrecy, subterfuge, the status quo.

[Lisa Gornick: writer, teacher, therapist.]

Gornick offers valuable advice for those who teach memoir-writing to young folk. They are, by definition, changing rapidly and vulnerable. Amidst the triggering turmoil of emotionally raw work, she has learned to direct students’ attention to the class’s touchstone and backdrop: work by established authors. Added to these, “a clear definition of each person’s responsibilities in the workshop, a consensual code of conduct for giving and receiving feedback, and a rigorous emphasis on the mechanics of writing” keeps students transforming their experience into art. This rigor sets true memoir apart from therapy or journaling, and it’s what kneejerk critics of the genre miss.“Writing a personal essay requires beating back our defenses and looking head-on at our foibles, misconceptions, foolishness and sins,” Gornick says. “As an analyst, I would say that the personal essay is a perfect storm for personal growth. As a writer, I would say that the personal essay offers an opportunity to shape raw experience into a narrative that clarifies who we once were, who we are now, and who we hope to become.”

Amen.

The post Memoir pro & con appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 27, 2015

Loving kindness

Review: Monica Wood’s warm memoir depicts love & loss in Maine.

When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine by Monica Wood. Mariner Books of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 231 pp.

In her stellar memoir, Monica Wood portrays her family’s quiet woe in the wake of her father’s death and the trauma, a few months later, of JFK’s assassination. Monica was only nine when her oversized, ebullient father fell dead that spring. He was on his way to work at another mighty entity, the Oxford paper mill, the big employer in their tiny Maine town of Mexico.

Wood juggles multiple, ongoing stories, including her widowed mother’s shame and depression; her three lively sisters who help Monica cope; her kindly, beloved Uncle Bob, her mother’s brother, a priest devastated and derailed by his brother-in-law’s death; the mill itself, provider of good jobs, sower of deadly toxins, site of increasing strife; friends and neighbors, including the Wood’s odd, immigrant landlords, who are played for humor but who were terrifying to young Monica; her teachers, the loving, eccentric nuns at school; the ripple effect in her large Irish Catholic family of the Kennedy assassination—and especially its effect on her mother; and Wood’s genesis as a writer.

A successful novelist before turning to memoir, Wood’s experience shows. She blends her childhood world and point of view with the wiser eye of her adult self. Often we see what her child self cannot—the author’s skill here a delight. Her prose is lovely, rich with details and metaphors. She does a lot with implication, knowing how much to leave unsaid.

After a college student, humming an aria he’s practicing, finds her fallen father outside his garage, news spreads. Here is the writer now, reflecting, before shading into her childhood perspective and her younger self’s mistaken, heartbreaking first inkling of loss:

We were an ordinary family. A mill family, not the stuff of opera. And yet, beginning with the singing boy who found Dad, my memory of that day reverberates down the decades as something close to music. Emotion, sensation, intuition. I see the day—or chips and bits, as if looking through a kaleidoscope—but I also hear it, a faraway composition in the melodious language of grief, a harmonized affair punctuated now and again by an odd, crystalline note fluting up on its own. A knock on the door. A throaty cry. . . .

My mother bursts into song. Or so it seems, on this morning in which nothing is as it seems.

Ohhh. My mother sings. Ohhh.

And then here, in the midst of an early scene in the family’s kitchen, Moncia observes her mother and uncle:

“Time for bed,” she says, still sitting. After the heartwreck of the first day, the sustained shock of the news, the ordeal of the wake, she’s composed herself for good and at great cost, and her body when I press myself against it feels like a gently closed door. It’s been thirty-eight and a half hours. Any further tears—thousands, millions, in the years she has remaining of her own brief life—she will shed out of our sight.

Father Bob is still here, sitting next to the birdcage, breathing like a gut-shot deer. Mum looks up. “Father,” she murmurs to her baby brother, “you’re going to have to pull yourself together.”

Another turn of phrase new to me, and it too sounds just right, for we have burst, haven’t we? We lie in pieces that must be pulled together, and Father Bob has to help whether or not he believes he can. He will pull himself together because his big sister reminds him that he must.

Wood’s interweaving of her adult knowledge here is deft, but it’s how she deploys young Monica, stunned, struggling to triangulate her loss, that renders the emotional wallop. Her story and her storytelling skill have been recognized. When We Were the Kennedys won the 2012 May Sarton Memoir Award for best memoir by U.S. or Canadian woman and the 2013 Maine Literary Award for memoir, among other honors.

This is one of my favorite memoirs. I pressed it on my wife, who pressed it on her four sisters. This Spring I taught it to an honors class of college freshmen; they’re a tough crew—they favor edgy circumstances, and they recoil from middle-aged sensibilities—but they liked it, and a few loved it.

I cherish its storytelling grace. I found Wood’s sentences thrilling, and was moved by the loving kindness and understated sadness that suffuse her narrative. Her book lingers in the mind, beckoning repeat readings. When We Were the Kennedys possesses an easygoing literary mastery

[Coming soon: an interview with Monica Wood about the memoir genre and writing When We Were the Kennedys.]

The post Loving kindness appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 21, 2015

Animals in life, literature

[Tess hitting the water hard in Florida.]

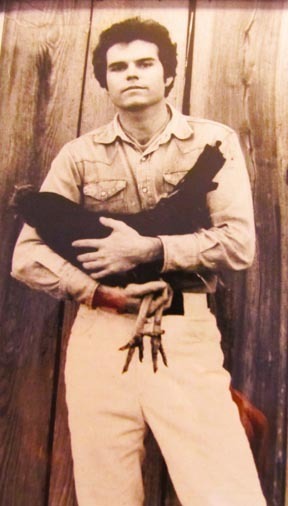

Dogs, ducks, chickens—nature & birdy days in youth & memoir.

[Chicken boy: Georgia, 1978.]

I’ve always needed or at least wanted animals in my life. My memoir is crawling with them. As a daydreaming boy I loved reading stories about animals and ecosystems—maybe the genesis of my passion for nonfiction. I got in trouble at school for reading a book about turtles during class. At home, my bedroom floor was covered with animal skins, including that of a zebra an uncle shot in Africa. Atop my walnut dressers: an incubator stuffed with domestic duck eggs and aquariums shimmering with snakes and fish caught in nearby lots and ditches. Sometimes a free-ranging iguana or parakeet passed through.I gave up the reptiles eventually. They were, well, too reptilian. Birds possess a warmth, maybe emanating from their feathers. There seems a reciprocal consciousness, even an interest, in their eyes.

Satellite Beach, Florida, where I grew up, was an earthly paradise, situated atop a scrim of sand between the Atlantic Ocean to the east and the Indian River, a broad estuary, to the west. Until my father’s almost-fatal heart attack in 1967, when he was 49 and I was twelve, he took us fishing and skiing in the river. I was grieving for the loss of the first home I’d known, our Georgia cattle ranch, but I took solace in nature. In winter, migrating ducks rode the river’s dark face, and lying in my bedroom at night I thought of them—each bird alone but all together and wholly immortal in their vast rafts. When I finally raised wild ducks in middle age, in Indiana, I felt them carry a piece of me into the sky when they took wing.

[Florida, 1981: Me & Tess.]

Such experiences helped draw me to Helen Macdonald’s acclaimed memoir H is for Hawk, reviewed in my previous post, about her training a goshawk to hunt. Her story kindled nostalgia for training my Labrador retriever, Tess, when I was a young newspaper reporter in Florida. I cast Tess into many a field and stream. We participated in a retriever trial near Tallahassee when she was still a pup, rapturous over fetching rubber bumpers. Later we hunted pheasants in Michigan and grouse in Indiana.Mostly I hurled Frisbees for her—she ran flat-out from my side and caught them over her shoulder, like a wide receiver. Tess appears early in my memoir of farming, helping me court my wife. And then, in our children’s early years, she shuffles off the stage with an arthritic shoulder, the cost of our endless Frisbee game. Tess took me from youth to middle age.

I’m really a farmer at heart, and my interest in hunting faded as Tess did. On that pocket farm in Indiana, Tess supervised my rearing of laying hens, broilers, bantams, and mallards. As a poultryman, I grew to hate raccoons and to harbor mixed feelings about raptors. They fascinate me—they’re birds, after all—but they eat chickens and ducks. My chosen birds eat grain and peck at grass; birds that eat them, or that consume any flesh, strike me as deeply wrong.

[Macho chook: Old English gamecock.]

My next great dog love was Jack, a feisty canine id loosed upon the world. That termite was a far bigger presence in Shepherd: A Memoir than was Tess. He gave chase to groundhogs, which riddled our pastures with holes, and to chicken-eating raccoons and opossums. Just before we moved off the farm we had to have him stitched up from his winning fight with a huge possum. He was 12. I posted Jack’s obituary here five years ago. Overcome with grief, I tried to avoid sentimentality and surely failed. Most such accounts ask for unearned emotion, though it hasn’t stopped me from reading them.In H is for Hawk, Macdonald’s love for her hawk’s killer soul rivets the reader. The goshawk, named Mabel, is gorgeous but, as Macdonald also underscores, more than faintly reptilian. To reward Mabel during training, Macdonald gives her treats of dead day-old chicks.

I know a fellow bird nerd when I see one. But give me, any day, a sleek mallard or a sturdy chicken with a yen for yellow corn. Or, in a pinch, a lovable dog.

![[Tess & her beloved bumper.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1432293714i/14921337._SY540_.jpg)

[Tess & her beloved bumper.]

The post Animals in life, literature appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 13, 2015

Bird nerd

[Now: Helen Macdonald recently with a raptor. Photo from The Times, UK.]

Review: readers flock to Helen Macdonald’s H is for Hawk memoir for its savory braided structure, intense immersion, poetic prose.

H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald. Grove Press, 300 pp.

It is so fatally easy to make young children believe that they are horrible.— T.H. White, The Once and Future King

[Then: Macdonald with Mabel, ca. 2008.]

In H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald brings out the beauty and killing prowess of raptors used as hunting allies. She’s steeped in the ancient tradition of falconry, reduced, in our time, to a tiny, odd subculture. The hook for this book includes her selection of a notoriously temperamental goshawk to train instead of a comparatively easy species such as a peregrine falcon. She spends much time fretting over her hawk and frantically running after it, raising a gloved fist and blowing a whistle.I should say her, not it: Macdonald’s goshawk is a girl. Endearingly dubbed Mabel, she is both gorgeous and a fierce avatar of death. So it’s all the more charming when Macdonald discovers that Mabel enjoys playing catch with crumpled paper wads. Mabel’s narrowed eyes mean mirth. But she’s a changeling. Triggered by sights and sounds, her quicksilver reactions—effectively her moods—are expressed in beating wings, biting beak, gripping talons.

H is for Hawk, the first memoir to win Britain’s Samuel Johnson Prize, is slow at first, and dense—this was my fresh-mind morning book for a good while before I adjusted to Macdonald’s rhythms. But heightened experiences appeal, and Macdonald evokes them in a narrative rife with savory juxtapositions. She braids three stories: taming and training the goshawk; coping with her father’s death and her disordered state; depicting novelist T.H. White’s own harrowing experience with a goshawk. White’s deeply damaged psyche and tormented life anger and chasten Macdonald in her mirroring pursuit.

We learn less about her backstory; Macdonald’s spare retelling may reflect the fabled British reserve, as well as her hunch about readers’ interests. Somehow this makes her memoir feel less damp with grief. Her father died; she bought a hawk. She is, however, grief-crazed before and during much of her hawking. A news photographer, her father had been her buddy. Unlike White, who was abused by his parents and at boarding school, Macdonald was nurtured, encouraged in her childhood rapture over winged predators.

Macdonald eschews dates, no doubt to make her story more timeless. After reading the memoir I studied its sketchy, seasonal clues. As I’ve pieced it together from the book, from reviews and interviews, and from her blog, her father dies of a sudden heart attack on a city street, while at work, in March 2007, when he is 67 and she is 37; in July 2008, some nine months later, she buys Mabel and trains and lives with her; the book closes in summer 2009.

Macdonald’s elliptical approach leads to similar conflations like this in Kathryn Schulz’s superb review and article for the New Yorker:

Helen Macdonald was in her third and final year as a research fellow at Cambridge, a prestigious postgraduate position, when her father died and, for eight hundred pounds sterling, she acquired a ten-week-old goshawk.

For some, her leaps won’t matter a whit—or are part of Macdonald’s virtue: she has mastered the art of leaving out things. Others will feel unmoored. For me, without a clear timeline linked to plot developments in the foreground hawk drama, narrative momentum faded a wee bit. This made the book, which is nicely reflective, feel more discursive than it is.

As well as being a nature writer, Macdonald is a poet, which may incline her to pare connective tissue from her stories. Her fealty to her threads keeps them clean. You won’t learn from her memoir about any romantic ties, or anything about her past except glimpses of her dad and her birdy girlhood. She even omits far-flung adventures in training birds of prey, such as a stint breeding falcons for a royal family in United Arab Emirates. She’s not discursive in that way. Her sharp focus here is her intense experience with one hawk, one death, one writer.

Here’s a spangled morning in a few strokes:

Last night the forecast was bad. A storm surge threatened to inundate East Anglia. All night I kept waking, listening to the rain, fearing for the caravans along the coast, their frail silver backs against the rain and rising seas. But the storm surge held back at the brink, and the morning dawned blue and shiny as a puddle.

Here’s one of her meditations on meaning:

Hunting with a hawk took me to the very edge of being human. Then it took me past that place to somewhere I wasn’t human at all. The hawk in flight, me running after her, the land and the air a pattern of deep and curving detail, sufficient to block out anything like the past or the future, so that the only thing that mattered were the next thirty seconds. I felt the curt lift of autumn breeze over the hill’s round brow, and the need to tack left, to fall over the leeward slope to where the rabbits were. I crept and walked and ran. I crouched. I looked. I saw more than I’d ever seen. The world gathered about me. It made absolute sense. But the only things I knew were hawkish things, and the lines that drew me across the landscape were the lines that drew the hawk: hunger, desire, fascination, the need to find and fly and kill.

Some nitty-gritty details of her lone, intense, antiquarian experience of living with a predator: her pockets, fridge, and freezer stuffed with dead chicks and raw meat; droppings in the TV room and dusting her clothes; white scars on her hands from beak and talons made to pierce and flay pheasants and rabbits. She evokes the quiddity—to use a Cambridge-ish word—of this fierce feathered creature and its unlikely potential for human partnership.

Braided structure, immersive experience, fine prose—these are why so many readers adore H is for Hawk.

[Before: Helen Macdonald in 2001 with a friend’s gyrkin.]

The post Bird nerd appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

May 6, 2015

Tiny libraries

The Little Free Library Book: Take a Book, Return a Book by Margret Aldrich Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, $25.00 hardcover (264 pages), April 2015.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

How far that little candle throws his beams;

So shines a good deed in a naughty world.

—William Shakespeare (Portia in The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene i)

Margret Aldrich loves books, and she loves to share them—so much so that she wrote a book about it: The Little Free Library Book: Take a Book, Return a Book. This volume tells the inspiring tale of a growing movement to unite people through the sharing of books in neighborhoods. The motto: “Always a gift. Never for Sale.”

The Little Free Library (LFL) concept was the brainchild of Todd Bol of Hudson, Wisconsin, who explained in a 2013 TED Talk how he and cofounder Rick Brooks began this program in 2009. Editor/writer Margaret Aldrich was taken by the idea, so she “planted” her own LFL in front of her Minneapolis home.

Aldrich’s new book probes the how and why of this program, with chapters about community building, literacy, creativity, overcoming challenges, the humanitarian “good deed” characteristics, global reach, and even yarn bombing—with a Foreword written by Bol. Aldrich enlarges these basic concepts with headings such as “Come Together,” “Celebrate Reading,” “Kickstart Creativity,” and “Pay It Forward.” She includes interviews with a selection of LFL stewards.

NooX, an ongoing study begun in 2012 by Canadian researchers, examines how neighborhood book exchanges relate to theories of information practices. Investigators identified four main goals in 2014—neighborhood destinations, interactive spaces, gathering spaces, and sharing books—emphasizing the wide divergence in these goals from steward to steward.

LFLs encourage the green reuse of materials for building, which preserves the environment while it also enhances the edginess of styles. The artistic aspect of these tiny book havens shines forth on practically every page of Aldrich’s book, in photos of all the different ways stewards around the world have presented their creations. The designs swing far and wide: a Victorian haunted house in Iowa City, a hollow ash tree in Canada, a deconstructed pinball machine in the Netherlands, a library made of buttons, a small VW bus, and a blue police box resembling the time-traveling TARDIS from Doctor Who. Stewards tweak these miniature houses and their literary contents much as bonsai addicts do their wee trees.

Want to build your own? Construction plans are included here as well, with tips for builders and installation guides. Whether you purchase a ready-made structure from the Little Free Library website or start from scratch, the next step is to register the finished book dwelling on the LFL world map to make it official.

I’ve wanted one for a long time. My childhood passion for books called me to this task. I was intrigued by the idea of releasing books into the wild to let them fly. A website called Bookcrossing actually provides a way to track book travels, should you want to spend the time to label and post your volumes online—which of course requires the finder to record the “catch” as well.

[Lanie Tankard’s Tiny Library at her home.]

Yesterday, I launched my own official Little Free Library. Last September, I had downloaded building instructions from the LFL website. In October, a craftsman working on my house set a post in concrete near the curb in my front yard, after I’d checked with city water and electric workers about placement. I tacked a wooden sign to the post: “Future Site of a Little Free Library.” Then I gave the plans to the craftsman, who promised to build me one by the end of the year. Good intentions fell by the wayside though, as he got busy with other jobs.In late December, I noticed a special promotion on the Little Free Library website for the prebuilt Cedar Roof Basic design—complete with free shipping, a big red bow, and stuffed full of free books from Coffee House Press. Who could resist?

When the unpainted LFL arrived, I noticed the name of the carpenter: Henry Miller in Cashton, Wisconsin. Miller is a talented Amish woodworker at H&L Rustic Reclaim who has built hundreds of LFLs. Thanks, Henry! Nice work!

Next came the painting—once the weather finally warmed up and it wasn’t raining. Since I was going for a folk-art theme, I used seven colors, with three coats of each (two over a primer). I admit, there were days when I thought I’d never finish. I found a colorful knob. I repurposed several metal items for decorations on the sides.

And suddenly, my LFL was ready. The craftsman even came by to install it for free, as a goodwill gesture. We chatted about what he liked to read, and he selected a book of poems, The Architecture of Language by Quincy Troupe, from the library. A Miles Davis fan, he said he remembered reading Troupe’s memoir Miles and Me and enjoying it.

[Margret Aldrich, author.]

In Margret Aldrich’s book, former US poet laureate Billy Collins notes Little Free Libraries are “a terrific example of placing books—poetry included—within reach of people in the course of their everyday lives.”Coming unexpectedly upon one of these wee book buffets laden with stories is akin to a parched traveler stumbling onto an oasis, lifting one’s spirits like a daub of color on a gray day. Aldrich’s book lovingly documents the role of Little Free Libraries in building communities as we reach out and meet one another.

Did you think LFLs were only about books? Oh my, books are just the tip of the iceberg.

Brava, Margret Aldrich!

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

The post Tiny libraries appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

April 29, 2015

Emphasizing structure

[Barrington’s short classic.]

I suppose like all writing teachers, I try to emulate certain teachers. But mostly I’m trying to be the teacher I wish I’d had. Someone who illuminates a genre and saves me from myself. The latter is too much to ask, I know. But here’s a secret. I think I’ve become a good teacher of memoir writing, at least for beginners.A key reason for my feeling of success is my evolving emphasis on structure. In my experience, green writers can produce creditable-to-impressive work if they focus not just on the story they want to tell but on how best to present it. Fine work ensues in my memoir classes if I show students framing, braiding, Hermit Crabs, and segmentation along with scenes and persona and the rest. Structure cracks open their material to themselves. Structure makes the eye-popping difference between a plodding chronology and a memoir essay enriched with layers and refreshing rhetorical moves.

I’m talking about receiving poignant and interesting work from a twenty-year-old. Someone who has read one novel for enjoyment in his life, whose grasp of grammar is shaky, and who has never willingly written. Much less taken a creative writing class. Maybe every teacher is doing that. If so, I’m conceited for suspecting I’m special. But amidst the very hard work of teaching, receiving such writing keeps me going. A kid’s essay may be a tad lumpy, a lopsided vase, especially the first draft, but it can also be—undeniably—art.

“Art is made of emotion, is about emotion, and asks for an emotional response,” I told my students this semester.

The key is to teach them to earn that tear, that laugh, that inner tingle in the reader. Expose them to fine work. Point out structures and techniques. Give them stimulating exercises. Their desire to tell their stories does the rest.

• • •

[Barrington: poet-memoirist-teacher.]

After drafting this post, I began rereading Judith Barrington’s concise how-to book, Writing the Memoir: From Truth to Art. I had read it several times before, and was surprised to notice this time how early it supports the notion of emphasizing structure to beginning writers. She’s known for crystalizing memoir’s core elements—“scene, summary, and musing,” which are explicated in Chapter Five and which teachers have built whole classes around. Barrington’s Chapter Three, however, is “Finding Form.” She begins:Do not make the mistake of thinking it is easier to tell the stories you have lived than to make up fictitious stories about imaginary people. It is no easier to write your own story well than it is to write anything else well. Like any other literary genre, memoir requires you, as Annie Dillard has said, “to fashion a text.” An important part of this crafting is finding the right form for your story—a structure that is more than simply an adequate vehicle for the facts. The form must actively enhance the subject matter, subtly reveal layers of meaning, and compliment the shape of the story with its own pleasing structure.

“Art announces itself in form,” I began my writing classes this semester. Meaning not form solely as in Barrington’s chapter title or as in fiction’s writers’ favored term for structure, but in every element being heightened or perfected. Title, diction, paragraphing, punctuation, persona, rhetorical variety, and of course structure.

Writing can be taught. That’s the lesson here, I guess. And an orderly process of emphasis can help students. When I was obsessed with scene in my own work, I got scene. Ditto for the reflective persona, which is the aesthetic sin qua non for literary memoir. My emphasis on structure along with those elements happened organically. And, as I say, it seems to have made the most difference. At least recently—but all elements must cohere.

My teaching is built atop my own failures. My publications were a litany of overcome errors until some faceless editor finally said Yes. So when I harp at the chalkboard about any element of creative writing, I’m haranguing my thick-headed past self. Trying to help that stubborn, slow-learner I was—and remain.

What I’ve learned about teaching writing is to clarify certain core principles. For me, in teaching memoir they are scene (dramatized action and its leap-ahead opposite, summary), persona (the writer-as-character amidst past events and the writer now, at the desk, reflecting on meaning), and structure (the shaped mode of presentation). These form the umbrella under which we also consider diction, syntax, imagery. Etcetera.

Maybe, after Barrington, I should list structure first on my syllabus?

“Structure is what writers talk about when they talk about writing,” I sometimes say, with a nod to Raymond Carver and his haunting story, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” (A long version of this story, then titled “Beginners,” prior to Gordan Lish’s severe shortening, is available at The New Yorker site.)

I think what I say is more or less true. In any case, I’m doing my part to make it so.

[This is a follow up to my recent post “Teaching Memoir, ver. 3.0” on how I began to structure my class by teaching different essay structures. Below is a link of Judith Barrington giving a reading.]

https://media.oregonstate.edu/media/song_for_the_blue_ocean_readings_judith_barrington/1_b1zdtej8

The post Emphasizing structure appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

April 21, 2015

Publishing essays

[My “Writing Life Stories” classroom in Courtright Memorial Library, Otterbein University.]

A teacher’s advice to students on revision & submission.

I sent this email last week to my “Writing Life Stories” students, who meet in person with me once a week and otherwise online.

Class,

I’m reading your new memoirs with enjoyment, appreciation, and a feeling of accomplishment as a teacher for what you’ve done. This semester, you’ve all made art from your experience. We’ve pondered and tried many aspects of writing—but we haven’t touched on publishing. I have some advice on that if you are interested in pursuing it. But first a caveat.

Last summer, attending an intensive writing workshop taught by a respected writer, I was struck by how stringently she separated writing from publishing. And by how sparingly she praised what we wrote. She was a nice person; it was just that we were there to make new work. The point was to keep making pieces, not to jump the gun and think about publishing them, not yet. I don’t think she thought in terms of whether she “liked” or “loved” an essay, but, rather, focused on whether it had some spark, some alive quality.

Most pieces, written in response to prompts, we filed for the future, to be struggled with or cannibalized back home. But everyone churned out one piece that she suggested we might read to the assembled workshops at the end of the week. Those we slaved on, late into the night in our dorm rooms. Then she tried to help each of us further realize its potential. By that time, the extra insight she could provide was powerful. The more frustrated a writer is with his own piece—meaning he has struggled hard with it on all levels and has turned it into an external object, a misshapen piece of clay he’s almost angry at—usually the more help an editor or teacher can provide.

As we near the end of our workshop, some of you may be ready to send off your most perfected pieces. They’ve been workshopped and rewritten several times. But know that while talent is common, the higher levels of craft are not. So make sure your essay is the best you can make it.

As a last stage, I recommend picking out three different essays you love by other writers and trying to emulate what you love in them in your own essay. Maybe it’s the colloquial snap of the language in one, the deft structure in another, the gorgeous sentences and metaphors in the third. Read one of them and then read yours aloud; you will be surprised by the tweaks that will jump out at you. Now repeat with the other two model essays.

Most literary journals are now online, or have an online component. Many of them use a handy submissions portal called Submittable. It’s easy and fun to use, and allows you to check on the status of your work under review. Follow the instructions. (Many journals charge a small reading fee for submissions, especially for contests—to fund winners’ awards—which is annoying but a fact of life.) Before submitting, spend some time reading the journal.

Here are some journals that specialize in publishing work by students (and probably by recent graduates):

In addition, here are a few others to look at:

• SNReview

• Vela Magazine – Work by women writers only.

[Rebecca McClanahan: “that’s a separate subject”.]

Good luck! Rejection is common, and doesn’t mean your piece isn’t good. Rejection can spur you to try harder, to act on any doubts you have and further polish or revise your essay. Until, finally, you know your piece is ready. Ideally that comes before you send it out, of course, and maybe in time it will.I think back to my purist mentor last summer. She put her emphasis so insistently on the practice because it’s real, it can endure, and it creates more writing. Like her, I realize, I have grown to EXPECT great work from my “Writing Life Stories” students. It no longer surprises me. But it does please me. Just wanted to say that, for me, working with you this semester has been rewarding and fun.

[My post last summer, “Among the Poets,” details my experience in a workshop with Rebecca McClanahan at Kenyon College.]

[A fanciful map of Otterbein University’s campus by alumna Lindsey Buck.]

April 10, 2015

Depicting others

This is a continuation of my last post on crafting a truth-telling persona in memoir.

2. Writing about others is as challenging as pulling off one’s own persona.

[A case study in how to write a bad guy.]

The only thing a memoir reader knows at the outset is that the writer survived long enough to write the book. Every memoirist knows two things: readers judge memoirists as people in a way they don’t novelists; and some people depicted in the book will read it in a close and even predatory way.Recently when I guest lectured to Alyson Latta’s online memoir class at The University of Toronto I was struck by how many students were worried about family reactions to their life stories.

One student asked, How do your family members feel about being included in your writing? Do you purposefully leave out details that they might find embarrassing or an invasion of their privacy? I replied:

I am lucky in that my family members are tolerant. I write less, and less personally, about my children than my wife. Some details are matters of negotiation. My children are often surprised because they usually don’t even remember an event that was huge for me. That is the nature of memoir—it’s so personal, and even from the same event, everyone experienced and remembers things differently.

My chipper answer later troubled me, because I was thinking of my situation and not what these students might be facing. And I realized that their situations might include living parents. My mother died during time I was writing my memoir, which mentioned our difficult relationship. She was tough and nails and wouldn’t have had the least problem with that. But Shepherd is more a daddy issues book, and I can’t even imagine having published it while my father was alive. Of course, much of it concerns coming to terms with his death, including the long shadow of his legacy. But telling any element of his story would have been off limits during his lifetime. That’s me. We do own our experience, I believe, but what we are willing and able to live with varies.

The students’ concerns made me remember the big hurdle I faced in writing about friends and acquaintances in Shepherd: A Memoir. I found that some were disturbed or overly sensitive about being portrayed. It made them uncomfortable. Hence I ended up changing most of their names and identifying details in my book.

Two events led to pseudonyms. The first was a stand-alone essay I crafted from the manuscript when my hired helper on the farm, a neighbor, died. We were very different but got along and worked together for years, and I spoke at his funeral. But when I proudly shared my essay with his widow, she was just puzzled by it. In her experience, apparently it made no sense. My pride turned to discomfort, almost shame.

Then an acquaintance I shared the manuscript with objected to being described as having grown up as “a poor kid.” For years he’d been bragging to me in those words about himself. Seeing it in print, he roared, “We weren’t poor! We were working class!” So I thought, To hell with it. I gave him and almost everyone else in the book a fake name and physical description. The weird thing, especially in his case, was I began to write with much more freedom and truth.

[Sartre: theorist of the stare.]

Both instances underscored that people are sensitive to being stared at—“congealed” as objects, as Jean Paul Sartre explains in Being and Nothingness. When you write about them, you reveal, inevitably, your staring appraisal. Or that’s how it can come off. As something not entirely sympathetic, for even the warmest portrait involves stepping back. Someone sees the gap between how he tries to come across—and hopes he does—and what others see. Or at least how one twit sees him.This aspect of memoir gets risky aesthetically (if the writer seems to be settling scores), physically (he might get punched in the nose), and legally (if sued for invasion of privacy) when an otherwise ordinary person is depicted in print negatively. Bill Roorbach faced this in his memoir Temple Stream: A Rural Odyssey (reviewed), in which there’s a bad guy. Here he describes the fellow in arresting detail on a ninety-degree Maine day:

He was enormous, wide beard untrimmed, two streaks of gray in it, thick mustache that fell over his mouth, flannel shirt, top button ripped, thermal-underwear shirt beneath despite the heat, massive shoulders, massive arms, massive hands black with engine grease, massive chest pressing the bib of a huge pair of Carharrt overalls, legs like tree trunks, big leather shoes that looked to be shaped by a chain saw, unlaced, heavy rawhide dangling, one pant leg rolled up showing long johns.

Bill prefaces the book with the information that the man is a composite of several backwoodsmen. And you can see why—and hope that that tactic works forever—given what a menacing fellow he turns out to be. He’s contemptuous of outsider Roorbach, and literally and figuratively trespasses upon him, but is hyper-sensitive himself about such matters, especially about Roorbach’s awareness that he’s a poacher.

Obviously depicting real enemies or just bad dealings with someone taxes the memoirist. Even if the person in question is family and dead—because of repercussions among relatives. You may write as a writer but you live as a person.

Despite stereotypes about the genre’s navel-gazing narcissism, the best memoirists manage to write a lot about others. And what typifies their prose isn’t vengeance but love. Love for certain others, love for the world.

![[Literary mind: Rebecca McClanahan.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1403849879i/10153495.jpg)