Depicting others

This is a continuation of my last post on crafting a truth-telling persona in memoir.

2. Writing about others is as challenging as pulling off one’s own persona.

[A case study in how to write a bad guy.]

The only thing a memoir reader knows at the outset is that the writer survived long enough to write the book. Every memoirist knows two things: readers judge memoirists as people in a way they don’t novelists; and some people depicted in the book will read it in a close and even predatory way.Recently when I guest lectured to Alyson Latta’s online memoir class at The University of Toronto I was struck by how many students were worried about family reactions to their life stories.

One student asked, How do your family members feel about being included in your writing? Do you purposefully leave out details that they might find embarrassing or an invasion of their privacy? I replied:

I am lucky in that my family members are tolerant. I write less, and less personally, about my children than my wife. Some details are matters of negotiation. My children are often surprised because they usually don’t even remember an event that was huge for me. That is the nature of memoir—it’s so personal, and even from the same event, everyone experienced and remembers things differently.

My chipper answer later troubled me, because I was thinking of my situation and not what these students might be facing. And I realized that their situations might include living parents. My mother died during time I was writing my memoir, which mentioned our difficult relationship. She was tough and nails and wouldn’t have had the least problem with that. But Shepherd is more a daddy issues book, and I can’t even imagine having published it while my father was alive. Of course, much of it concerns coming to terms with his death, including the long shadow of his legacy. But telling any element of his story would have been off limits during his lifetime. That’s me. We do own our experience, I believe, but what we are willing and able to live with varies.

The students’ concerns made me remember the big hurdle I faced in writing about friends and acquaintances in Shepherd: A Memoir. I found that some were disturbed or overly sensitive about being portrayed. It made them uncomfortable. Hence I ended up changing most of their names and identifying details in my book.

Two events led to pseudonyms. The first was a stand-alone essay I crafted from the manuscript when my hired helper on the farm, a neighbor, died. We were very different but got along and worked together for years, and I spoke at his funeral. But when I proudly shared my essay with his widow, she was just puzzled by it. In her experience, apparently it made no sense. My pride turned to discomfort, almost shame.

Then an acquaintance I shared the manuscript with objected to being described as having grown up as “a poor kid.” For years he’d been bragging to me in those words about himself. Seeing it in print, he roared, “We weren’t poor! We were working class!” So I thought, To hell with it. I gave him and almost everyone else in the book a fake name and physical description. The weird thing, especially in his case, was I began to write with much more freedom and truth.

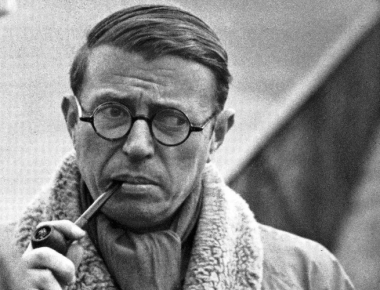

[Sartre: theorist of the stare.]

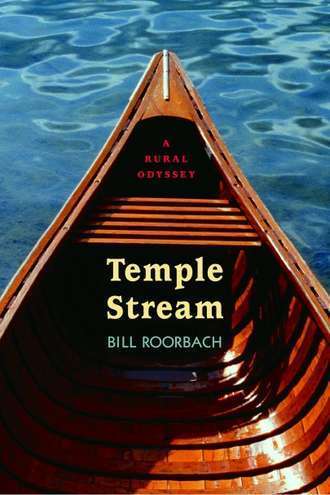

Both instances underscored that people are sensitive to being stared at—“congealed” as objects, as Jean Paul Sartre explains in Being and Nothingness. When you write about them, you reveal, inevitably, your staring appraisal. Or that’s how it can come off. As something not entirely sympathetic, for even the warmest portrait involves stepping back. Someone sees the gap between how he tries to come across—and hopes he does—and what others see. Or at least how one twit sees him.This aspect of memoir gets risky aesthetically (if the writer seems to be settling scores), physically (he might get punched in the nose), and legally (if sued for invasion of privacy) when an otherwise ordinary person is depicted in print negatively. Bill Roorbach faced this in his memoir Temple Stream: A Rural Odyssey (reviewed), in which there’s a bad guy. Here he describes the fellow in arresting detail on a ninety-degree Maine day:

He was enormous, wide beard untrimmed, two streaks of gray in it, thick mustache that fell over his mouth, flannel shirt, top button ripped, thermal-underwear shirt beneath despite the heat, massive shoulders, massive arms, massive hands black with engine grease, massive chest pressing the bib of a huge pair of Carharrt overalls, legs like tree trunks, big leather shoes that looked to be shaped by a chain saw, unlaced, heavy rawhide dangling, one pant leg rolled up showing long johns.

Bill prefaces the book with the information that the man is a composite of several backwoodsmen. And you can see why—and hope that that tactic works forever—given what a menacing fellow he turns out to be. He’s contemptuous of outsider Roorbach, and literally and figuratively trespasses upon him, but is hyper-sensitive himself about such matters, especially about Roorbach’s awareness that he’s a poacher.

Obviously depicting real enemies or just bad dealings with someone taxes the memoirist. Even if the person in question is family and dead—because of repercussions among relatives. You may write as a writer but you live as a person.

Despite stereotypes about the genre’s navel-gazing narcissism, the best memoirists manage to write a lot about others. And what typifies their prose isn’t vengeance but love. Love for certain others, love for the world.