Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 12

June 18, 2014

Ancient stories . . .

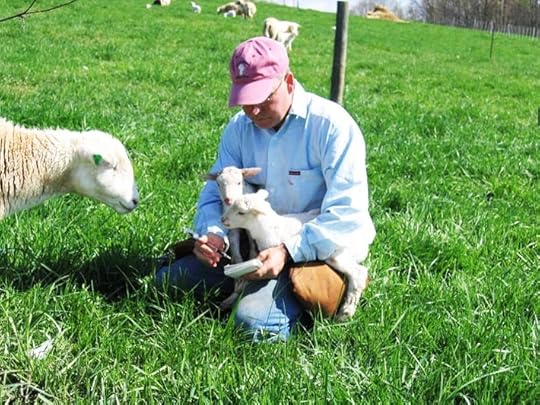

[Everyone present and focused on my writing: working lambs one spring.]

. . . in which writing & pedagogy meet farming & foxes.

I.

“It has to be about the reader,” began Philip Gerard. “If not, what am I doing with your book?”

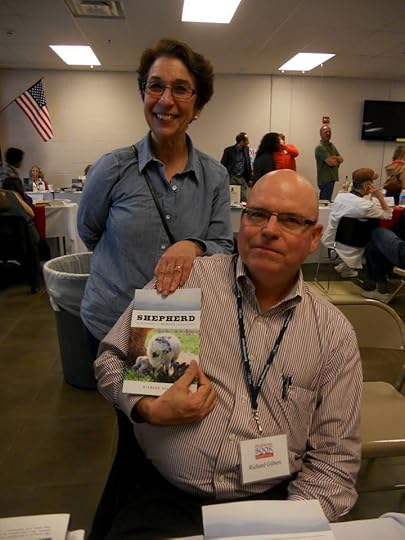

[Meanwhile: Kathy enjoys Virginia.]

Gerard’s keynote that Friday opened the recent River Teeth Nonfiction Conference at Ashland University in northeast Ohio. His opening words hung in the air. I tried to claw my way back to them. Yes. That’s it. Talk about that. Only he moved on into his focus, the allure and the power of research. He’d stated a profundity—in practice, a paradox— about writing and publishing and just as quickly left it. Upon reflection, his intended connection was obvious: give good content.But what’s good? What does serving the reader mean? “Why should I read your story?” haunts writers, especially those of personal essays and memoirs. (And even if writers can answer for themselves, editors and publishers will rule before regular readers can.) How many celebrated books have you not finished? What did most readers like? At base maybe there’s character, or at least personality, that we respond to. Before that, there’s technique. Hence the endless discussions about craft at Ashland in those last days of May.

Before the writing conference, I’d ended my teaching year, undergone 2.5 weeks of Hospice volunteer training, and attended a camp for schoolteachers on how better to teach English to non-native speakers. Pedagogy was much on my mind. I’d had my own best teaching semester ever. I’d marveled at the information, enculturation, and student involvement fostered at Hospice and at the way my Otterbein University colleagues taught a classroom full of teachers. At Ashland, there were those thrilling flashes of insight between presenters and audience.

Just people helping people, trying to teach them—always a compelling meta-narrative. Maybe the oldest story in the book.

II.

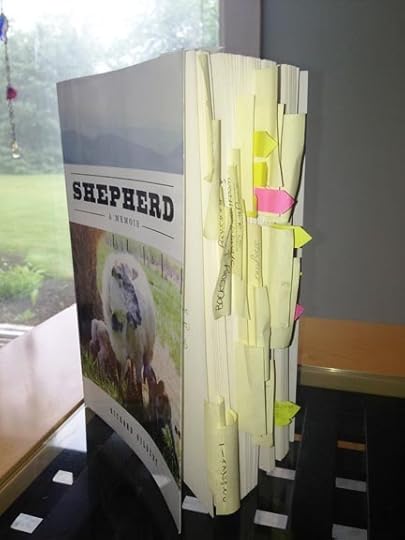

[Jenny Patton’s mauled copy of Shepherd.]

I was thrilled when a friend at the conference, Jenny Patton, showed me her mauled copy of Shepherd: A Memoir. In the midst of writing her own memoir, mine had helped her with structural ideas. I admired in her that wonderful focus a working writer achieves. I likewise ransacked books— late in my own process, Cheryl Strayed’s Wild (discussed) gave me ideas about how and where to deploy backstory. All the same, I’ve never seen any book marked and flagged like Jenny’s copy of mine.Yet it seems a hurdle for Shepherd that farming has become exotic. Even as we’re in the midst of one of America’s back-to-the-land booms, beyond that niche there may be less knowledge and less interest in agriculture than ever in human history. At least in developed nations that take food for granted.

Every evening at Ashland, walking back to my dorm stuffed full of craft tips and conversation, I called my wife, Kathy, to get her very personal news from the farm front. About the time I headed north for the conference, she had driven south, to Virginia, to farm-sit for our daughter Claire and her husband, David. Alone except for their animals—a pig, four goats, four mallards, countless chickens and bantams in three groups, a dog and two cats—Kathy was feeling disoriented and sometimes lonely. In one day, she’d gone from an intense office job to a quietly demanding and thankless role as a caretaker tethered to ornery animals and the whims of weather.

She was finally relaxing Saturday afternoon, reading a novel in the porch swing between chores. Claire’s laying hens came cuk-cuk-cukking across the lawn, chasing bugs and nipping bluegrass. A movement caught Kathy’s eye. She saw a red fox dash from a stand of pines 20 feet from her and grab a fat hen by the wing. Kathy yelled and ran and threw her shoe.

But that fox carried away its prize, scoring a tender five-pound dinner. Anymore you can’t assume that, somewhere in America on any given day, somebody will get kicked by a mule. I’m here to tell you, however, that at least one hen was snatched by a fox one Saturday in Virginia.

Kathy freaked out, of course: violent death on her watch. She wasn’t mollified when I mentioned that she’d merely entered a new narrative. She, Claire’s clueless chicken, and that wily fox, were actors in an ancient drama.

III.

[They’re cousins! Brownie & Belle.]

I was the new player—along with our dog, Belle, who would get to visit her cousin, Claire and David’s dog, Brownie. After driving home Sunday afternoon to re-pack and sleep, I ransacked our garage for my old pen-building tools—various pliers and cutters and crimpers, some staples and deck screws, my cordless drill—and hit the road.Kathy’s ending of the flock’s free-ranging ways had underscored serious limitations in our daughter’s avian housing. I keep abreast of poultry appurtenances and was excited about building a couple of light, moveable grazing pens.

When I arrived in southwestern Virginia—a modest drive from central Ohio, except the whole of West Virginia is always in the way—rainy weather had set in and the need seemed more dire than I’d imagined.

Six adolescent partridge Plymouth Rocks were now caught full-time between two other groups in their pen: the mallards (though happily playing in the soupy outside run, they were irritable chook tail-biters) and two grouchy mature hens (comb-pecking hussies) that dominated the small coop’s covered portion. The sodden and mud-spattered young chickens appeared miserable.

Kathy and I drove around half of Monday, gathering wire and wood. We plan to retire here, near the university town of Blacksburg, and it struck me that, for some reason, we’re fated never to leave Appalachia for long. Much of Shepherd deals with our initial culture shock in Ohio’s Appalachian region. Southwestern Virginia is Appalachian as well as southern, and for the first time I experienced what that meant. These influences can seem jarring, maybe a bit schizophrenic.

[Muddy & nasty crowded coop.]

But a dollop of southern charm softens the warier hill culture, and the overall graciousness and the more relaxed pace felt refreshing after busier, blander Ohio.It amazed me how hard I worked and how sore I got building two measly 4×6 pens over 2.5 days. Squatting and hammering revealed gravity’s renewed mastery over my 59-year-old body. Getting up and down and moving around, fetching supplies and bending or cutting welded wire, involved staggering. Everything took astonishing effort. At night my spine burned, my neck stiffened, my knees ached. My hands, bent like claws, could hardly hold my medicine: ibuprofen chased with beer and bourbon.

[Dad & Chicken tractor to rescue!]

“Why didn’t you tell me that aging is like being stoned?” I asked an older friend. My problem, he informed me, is I’m out of shape. Fair comment. We left the farm five years ago, and I sat down. Kathy and I have our exercise routines, sure—walking around the neighborhood daily and lifting weights a couple times a week—but there’s nothing like physical labor to make a mockery of chichi suburban fitness.Of course no one had sympathy for my suffering. Friends and family laughed at my complaints, and blamed me for Claire’s farm. “Genetics will out,” Kathy said. Okay, fine. But, for the record, I have never furnished a house or a barnyard—let alone both—from Craig’s List.

[The mallards enjoy their clean grazing pen.]

Recovering in Ohio, I’ve begun to suspect I’m one of those men whose externalized obsessions keep him sane. Sheep farming occupied me for a solid decade; then I wrote a book about it, which took almost as long, seven years. Maybe, like returning to Appalachia, I’m fated to keep teaching writing and writing about farming.At least one thing’s certain: I’ll be taking care of farm animals again whether I own them or not.

[Kathy pats Claire and David’s overgrown pot-bellied sow, Oreo. Another Craig’s List animal, goat Timone, observes.]

June 11, 2014

Awake at the wheel

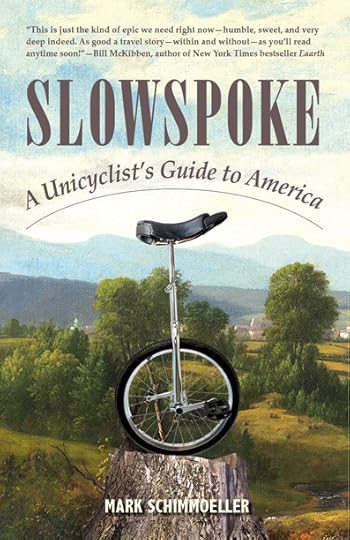

[Mark Schimmoeller & his wife on their Kentucky homestead.]

A unicyclist muses across the land while braiding a memoir.

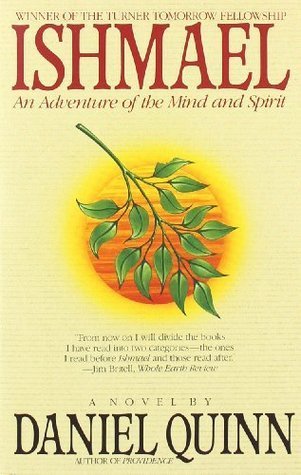

Slowspoke: A Unicyclist’s Guide to America by Mark Schimmoeller

Alice Peck Editorial: $19.82 hardback, $13.03 paperback. Forthcoming from Chelsea Green Publishing.

Guest Review by Lanie Tankard

The wheel is come full circle; I am here.

—William Shakespeare, King Lear

One day Mark Schimmoeller decided to do a little traveling, “attempting to visit people living for something other than what our consumer society deemed was important.” Thus was his mission when he set off in 1992 atop one wheel for a cross-country unicycle trip.

One day Mark Schimmoeller decided to do a little traveling, “attempting to visit people living for something other than what our consumer society deemed was important.” Thus was his mission when he set off in 1992 atop one wheel for a cross-country unicycle trip.

Body balance steers this upright one-wheeled vehicle driven by pedals. Unicycles appear to date back to the late 1800s and a bicycle called a “penny farthing.” The benefits of riding a unicycle are documented, and riding on one wheel has even been pushed to an extreme sport.

The author of Slowspoke meets all types of people living along the byways of America as he buys provisions, dodges cars, and seeks out places to camp for the night. He sketches word portraits of folks who don’t trend on Twitter, just as real as the ones who populate reality shows on television.

Schimmoeller muses as he rides, in no hurry to arrive. The reader ponders along with him, about topics such as time: “It had become cool to have no time, to be busy.“Ah, I thought, but Socrates long ago warned: “Beware the barrenness of a busy life.”

It was just this type of recurring silent mental dialogue I found myself having with a unicyclist that decelerated my progress through Slowspoke. We ramble along in our thoughts, he and I, noticing patchworks of woods and fields, hearing the sound of the wood thrush, and feeling the hot morning sun on our faces.

Schimmoeller becomes so comfortable riding as I read that he begins to tell me about his childhood. His parents were former Peace Corps volunteers who became Kentucky homesteaders raising their children far from the madding crowd. Gradually he rolls out the story of how he courted his wife. He gently chronicles a life off the grid as he and his wife construct their own home in the woods near the one his parents built.

Then, bit by bit, Schimmoeller starts weaving in another thread—his quest to save a large parcel of Kentucky property next to theirs so that it can be rescued from logging and turned into a land trust. Will he succeed?

The book by now has become a braided memoir with three strands: the unicycle journey, the author’s family life, and the quest to save land from logging. As he crosses the USA, Schimmoeller delves deeper into himself to work out philosophical aphorisms to live by. While commenting on hidden beauty during his coast-to-coast crossing, he isn’t afraid to air out his own personal weaknesses as well.

Schimmoeller is not the only rider to make a long unicycle trek. A few books and blogs record others, such as Bob Mueller’s Bob Across America, Cary Gray’s CaryOutThere, Dustin and Katie Kelm’s Refugee Ride, and Gracie Cole’s One Wheel for Life. Schimmoeller’s writing, however, is glorious.

Slowspoke did seem to drag in a few places toward the end, although one could certainly view it as an intentional rhetorical device to symbolize running out of steam on a long expedition. The story braids worked in most places but on occasion were timewise confusions, as they didn’t alternate in regular intervals. Several small repetitions of information occurred.

All in all, though, Slowspoke is a tale very well told. Schimmoeller manages to convey enthusiasm for the common bonds he unearths with those he encounters on his quest across the land while at the same time share insights into his own psyche sparked by these interactions. He does so in a calm straightforward manner, a method that is effective because it is not didactic. His prose meanders in a way that matches the pace and wanderings of his unicycle. That thought process forces the reader also to slow down and enjoy the ride.

The book reminded me in certain ways of The Road to Somewhere: An American Memoir by James A. Reeves and Blue Highways by William Least-Heat Moon, but Mark Schimmoeller’s Slowspoke is distinctly different in both the mode of transportation and trifocal nature of the braided storylines.

“Time is the longest distance between two places,” Tennessee Williams wrote in The Glass Menagerie. Do we have time to read an unhurried book like Slowspoke? Such softspoken slow-paced volumes are easily overlooked, but they contain large-scale wisdom.

Lanie Tankard is a freelance writer and editor in Austin, Texas. A member of the National Book Critics Circle and former production editor of Contemporary Psychology: A Journal of Reviews, she has also been an editorial writer for the Florida Times-Union in Jacksonville.

June 4, 2014

Her emotional compass

[Julene Bair swims in the Republican River, Kansas.]

Q&A: Julene Bair on what’s at stake in her memoir of prairie love.

The Ogallala Road: A Memoir of Love and Reckoning by Julene Bair. Viking, 278 pp.

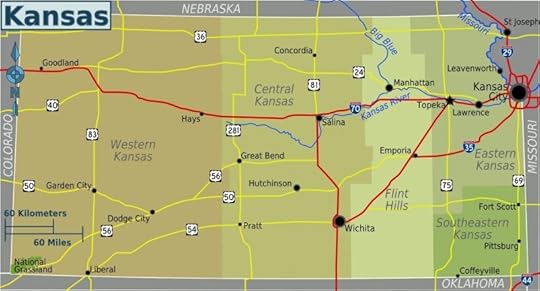

With a great publisher, a page-turner of a story, and an appealing, actively publishing author, Julene Bair’s memoir The Ogallala Road is red hot. As I noted in my recent review, her book features two compelling foreground narratives: her romance with a man of the prairie and the fate of the sprawling family farm in western Kansas she has recently inherited. Bair agreed to a virtual sit-down with Draft No. 4 about her writing process and the fate of the Ogallala Aquifer that features prominently in her book.

An impressive feature of The Ogallala Road is the number of narrative threads you weave elegantly through it—and resolve. These include: your childhood; your family and especially your father; your mid-life love affair with an intellectual cowboy; your son and your parenting of him; different types of farming and the tragic misuse of the Ogallala Aquifer to grow corn on the plains; and your love of wilderness, water, and desert. How in the world did you work out all of this while telling such a forward-moving, compelling foreground narrative?

I don’t want any struggling memoirists out there to think this came easily. I wrote an essay for the current (May/June) issue of Poets & Writers comparing the way I write to the way my father farmed—doggedly and with determination. When a crop didn’t “make,” he plowed it under and started over. I plowed under many drafts before I understood that the central storylines were my romance with the rancher I met when I went home to research the watershed and my struggle to live up to my father’s first commandment, “Hang on to your land!” The strength of those stories drives the book forward and makes it possible for me to share much else that I care about.

The Ogallala Road begins on a hot August day in 2001 as I’m visiting the farmstead I grew up on. From there, I intend to follow the dry creek in our old pasture all the way to its outlet in the Republican River. I am searching for one of the Ogallala-fed springs that I’ve read supported human habitation on the Plains all the way back to Paleolithic times. Afraid that groundwater pumping has drained the surface of every last drop, I’m elated when I do find a little spring-fed pond. Then, on page ten, while sitting in the shade of a cottonwood nearby, I hear the familiar rattle of a pickup pulling an empty stock trailer down the hill. Enter Ward, the love interest (not his real name.)

While it might seem that the writer in me had been handed these events on a silver platter, it took me forever to accept them as the way to begin the book. I knew that Ward would figure highly, but I fought introducing him so soon. I didn’t want readers to think that this was just a love story, so I wrote and discarded literally dozens of prologues and opening scenes trying to place that secondary plot line in the more important family-land context. When a friend finally suggested that I chop the first twenty-three pages and begin as I’m trundling across our plowed wheat field toward our old canyon pasture, I could feel the dead weight of all that explanatory writing drop away. And I could feel the actual story lifting off on page one. All I needed to establish the family-land context were those few pages during which I visit the old farmstead and confront my guilt over my own family’s participation in the aquifer’s depletion.

The second narrative thread is introduced on page fifty-five, when my brother Bruce announces at a family Thanksgiving dinner, with Ward in attendance, that he “is not certain what the future holds for the Bair farm.” My recoil at the topic he’s broaching makes it evident that the more important and overarching story will be whether my brother and I will find the wherewithal to honor our father’s commandment.

The take-home for me is that if I ever find the energy and courage to attempt another book-length narrative, I really need to understand what is at stake for the narrator. My identity as my father’s daughter and as a landed person of that place had been under threat ever since I was sixteen and he sold the farm I grew up on, consolidated our holdings elsewhere in the county, and moved us to town. I didn’t understand that as I was writing this book, because, as I explain in my P & W piece, I was living the story as I wrote it. When events finally reached a real-life conclusion, I came to terms with them only as I wrote. I did my processing on the page.

Unity of theme also helps the book cohere. Place isn’t just elevated to the level of character in this book, as critics sometimes claim about western narratives, but functions more as the characters’ creator. Our land dictated that we would be dry-land farmers and livestock ranchers, and also dictated my values and my aesthetics. So I can tell the story of my relationship to my son, because I seek nothing more for him than that same rootedness, and I can tell the story of Ward and me because he seemed as rooted in his land as my father was and I hoped he could be that kind of father to Jake. The aquifer had made our lives possible, so I could tell the story of the Cheyenne, who occupied the land before us and drank from those Ogallala-fed streams. My love affairs with mountain lakes and the Mojave Desert also go back to that land. I would not have felt drawn to either had I not grown up in that wide-open, sunlit place where water could not be taken for granted.

[Bair's roots are in far western Kansas, near the town of Goodland.]

Let’s talk about structure. Your book features five sections—do these correspond to “acts” in your mind? For instance, in your conception is The Ogallala Road really a classical three-act dramatic structure, say, despite the way you broke it? How did you decide to place the long flashback section of your twenties adventure in the Mojave where you did, second?

The section breaks are much like chapter breaks, except that they signify bigger shifts. I didn’t really think in terms of the classic three-act structure, and having just visited its description on Wikipedia, I’m glad I didn’t confuse myself with the need to do so. It would have frustrated my uncovering the story I needed to tell. After all, life doesn’t follow a three-act structure, and, for me, memoir is about real life—with the material chosen for inclusion around a particular theme or crisis or issue.

But I did think about the need for suspense, with tension building to a climax and then a denouement. And reflecting on your question helps me understand why my editor advised that I not emphasize the climactic moment in the Ward-Julene story. Doing so would have drawn readers’ attention away from the still rising action in the family-land story. I’d been struggling with this structural issue for ages, and finally, at her advice, cut a very dramatic chapter that I kept trying to make pivotal when it wasn’t really that important, in the long run, to my challenged identity.

Regarding Part II, in order to fully identify with a story and a character’s current struggle and motives, readers need some immersion into the character’s past. It’s customary to have that look-back occur fairly early, but not before the story is well-launched. The alternative would have been to write chronologically. In that approach, I would have begun in childhood, left Kansas at eighteen for San Francisco, rediscovered the outdoors and become a nature girl, moved to the desert, gone home after my second disastrous marriage to a cowboy, farmed with my Dad, gone back to school in Iowa, moved to Laramie to teach, all before I met Ward. It would have been a plodding, self-involved, autobiographical approach, and not at all artful.

I wasn’t a famous person whose life warranted chronicling. We “plebe” memoirists have to be much more purposeful than that. We need to understand where the drama lies and lead with it. But more importantly, we need to understand what we’re really writing about. I don’t like memoirs that are satisfied to simply record a series of bizarre incidents or childhood suffering. I want meaning to be made from events, no matter how sensational they might be. True, the love story got handed to me on a silver platter, but it wouldn’t have been pertinent unless, through telling it, I could address the issues that have driven my life. I was attracted to Ward because I thought he offered me a way back into a sane, self- and land-sustaining relationship to the place on earth that had made me who I was.

I needed to tell the backstory of my love for mountain lake swimming and my wild and adventurous foray into the Mojave in order to establish and share my genuine passion for water and desert. These fueled everything. They gave me the energy to tackle a topic that had plagued my conscience for years and that I feared, rightly, I might not be able to resolve (and would therefore be stuck writing about for years, until it resolved itself—sort of).

The latter two-thirds of Part II are about my relationship with my father, once I returned home from the Mojave after a failed marriage. In my childhood, gender roles were strictly defined on the farm and it had been impossible for a girl to imagine herself as a farmer. So for him to embrace me as a potential successor not only elevated me to a status equal to my brothers, but gave me intimate knowledge of the chemical and extractive methods we now employed. All of this—the intensified loyalty to a father who believed in me that much and my complicity in the environmental harms—upped the ante when I was confronted with whether to sell or keep the farm.

![[Grassland at the Tallgrass Kansas Prairie National Preserve.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1402053007i/9887893._SX540_.jpg)

[Rangeland at the Tallgrass Kansas Prairie National Preserve.]

The sentences in your book are gorgeous. Could you discuss how you create and refine them? For example, do you try to perfect each one as you go or do you spew out prose and return later? What role does reading, and of what kind, play in your practice and growth as a maker of sentences, essays, and books?

I rewrite, or at the very least tweak, every sentence dozens of times. Sometimes (rarely) a passage pours out of me, and when that happens I try to respect the mysterious source that gifted it to me. I try not to defuse the energy, but even then I will delicately go in and tweak, trim, expand and elucidate. I don’t print a chapter out until I think it’s getting close to finished, but when I do, problems invariably leap out at me that I couldn’t see when reading on the screen. When I think a chapter or essay is perfected, I read it aloud, and let my ear dictate further changes. I don’t seem capable of moving forward until I’ve perfected the prose in a chapter.

I don’t advise this approach. I would prefer to spew and spiff later. But how much fixing something takes seems to be an indicator of how much bullshitting I’m doing. Often, in the umpteenth pass, I realize that the whole chapter or essay is just an elaborate attempt at saying something important when I’m actually lying or not saying anything at all. So into the “cut material” file it goes, never to be looked at again. Then I start over, chastened and more honest, because I don’t want to go through all of that again.

This painstaking process makes writing a veritable black hole, time-wise. And because the rest of my life fills whatever space writing leaves, I don’t get as much time to read as I would like, but I always reserve bedtime for books that feed my spirit. I found, during the drafting of this book, that I would try to incorporate the strengths of whatever book I was reading at bedtime into my own work the next day. (I don’t worry about taking on others’ voices, as I feel that my voice, as long as I’m not trying to fool anyone, will always be my own.)

Ellen Meloy is my favorite nature writer. Whenever I was reading one of her books, I strived harder to craft more original sentences, and also to pull out the stops on my passion for nature. Reading her also made me try to be funnier (while trying not to seem to try—try doing that!) In short, she set the bar really high. I practically worship Craig Childs, for the depth of his knowledge and evocations of the desert, water, and the natural-world. David Abram’s Spell of the Sensuous influenced me deeply, because he articulates the non-human forces that are interacting with us all the time, while we bumble harmfully along, oblivious to our connection to all things.

Novels are really important to my writing also. Like most people, I’ll stay up much later to read fiction than I will to read most nonfiction (other than narrative memoirs). But the plot is like a locomotive. What counts is the freight it carries. I read for insight and for the catharsis I experience when an author makes me feel all that her characters are feeling. Only writers with a perfectly tuned emotional compass can do this, and that’s the characteristic, as a human and a writer, I most wish for. Standouts as I was writing this book were Elizabeth Strout’s Amy & Isabel (even better, in my opinion, than Olive Kitteridge); Marilynne Robinson’s Home; Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are Completely Beside Ourselves; and Jo Ann Beard’s In Zanesville. When I read books like these, I know that, the very next day, I will have to—have to—find a way to express what I’ve barely intuited before but which is propelling me through life without my full awareness. That’s the great thing about writing—making the unconscious conscious—and the fact that there’s always more down there, waiting to be discovered and said.

Your book caused me to feel pained by the destruction of the Ogallala aquifer so farmers can grow corn where it should not be grown. In geologic time it will refill, one supposes. But is there any hope that this recovery will begin sooner by our ending or severely reducing irrigation on the plains? What do you foresee for the region when and if its inhabitants truly need the water to sustain human life there? Are we going to be trucking in water the way we now transport everything else?

As to whether the recovery could begin sooner, I had a wonderful experience last October, although it was preceded by a disappointment. On a visit home to western Kansas, I first stopped by Big Spring, the one Ward and I visited in the book. From my reading, I had determined that Big Springs might have been the one that provided water to three or four thousand Cheyenne Indians, and many times that number of horses, for a sun dance held in the Beaver Valley in 1857. When Ward and I visited the spring in 2002 it was much diminished but deep enough that it probably would have reached my waist had I waded in it, and it stretched for a hundred or more feet down the bed. But last October, after several more years of intense pumping and an intense drought, it wasn’t a question of wading anymore. I stood at the lowest point, and my shoes remained bone dry.

As to whether the recovery could begin sooner, I had a wonderful experience last October, although it was preceded by a disappointment. On a visit home to western Kansas, I first stopped by Big Spring, the one Ward and I visited in the book. From my reading, I had determined that Big Springs might have been the one that provided water to three or four thousand Cheyenne Indians, and many times that number of horses, for a sun dance held in the Beaver Valley in 1857. When Ward and I visited the spring in 2002 it was much diminished but deep enough that it probably would have reached my waist had I waded in it, and it stretched for a hundred or more feet down the bed. But last October, after several more years of intense pumping and an intense drought, it wasn’t a question of wading anymore. I stood at the lowest point, and my shoes remained bone dry.

After that, I dreaded what I might find when I visited the South Fork of the Republican River, also in that northwest corner of Kansas, but instead of a vanished river I found a resurgent one—running higher than I’d ever seen it before. Despite the season, I just couldn’t help myself. I had to put on my bathing suit (which I bring on every trip regardless of how unlikely a swim might be) and jump in. After returning home, I called the groundwater district on the Colorado side of the border and confirmed what I already suspected. The river was running so high for two reasons: in settlement of a long-fought lawsuit between the states over the Republican, Colorado had opened the floodgates at Bonny Dam, a Republican River reservoir where my father used to take me fishing; and, and they had closed down hundreds of irrigation wells, also in order to restore flow to the river. So the answer is a resounding yes. Shutting down wells or vastly reducing the pumping rates can begin to stabilize the aquifer, and even restore or improve the flow in some of those precious streams. But the longer we wait, the less hope for them remains.

What do I foresee for the region? The world also has a stake in this. The most recent United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change tells us we’re going to need our aquifers in order to sustain crops that we could traditionally grow without the aid of irrigation. (It takes only a few inches or less to pull a wheat crop through a drought, whereas irrigated corn requires anywhere from fourteen to twenty inches.) So really, the ability of many people to get enough to eat by 2050, when nine billion people are projected to inhabit this planet, will be direly affected if the Plains “breadbasket” become less viable.

As for the farmers and local economies, there will probably always be enough water for small municipal needs, because when the aquifer falls below a certain level irrigation rates can’t be sustained. But there won’t be much point of living there if even those traditional dry-land crops can’t be grown. So unless we find the political will now to get the federal government to stop subsidizing the aquifer’s destruction (through the ethanol mandate and Farm Program subsidies of thirsty crops in the region) and instead underwrite a return to more drought-tolerant crops and grazing on the High Plains, the region is indeed headed for a crash landing.

[I took this last summer, crossing the Mojave Desert.]

May 28, 2014

Desire in a thirsty land

[A prairie windmill. Image from Shutterstock.]

Julene Bair’s memoir of romance & eco-tragedy on the prairie.

The Ogallala Road: A Memoir of Love and Reckoning by Julene Bair. Viking, 278 pp.

Bair’s mournful tale is told with resignation, honesty and heartbreak, but also with strength and joy as she shares memories . . . [T]his is a book by a tough, restless, energetic, admirable, principled Kansan who also happens to be a fine writer.—review by Mark Bittman in the New York Times Book Review

We read literature to escape, if only briefly, our own subjective silos. We yearn to piggyback upon someone else’s experience of life. And we seek, as well, clarity: the meaning someone has harvested from her existence—also the order and beauty in that restless act, that hero’s effort to distill coherence from the quotidian.

Here is a story; here is its wisdom.

The wonderful thing about this fine memoir, Julene Bair’s recent The Ogallala Road: A Memoir of Love and Reckoning, is that it shines so brightly in both dimensions. Here is why books remain quietly important. Why they’re still honored in an age of louder, less personal mass media and of jittery, flash-in-the-pan social media.

The Ogallala Road opens with Bair on a quest for water, which she loves, this child of a thirsty landscape. She’s roaming beside a creek in the High Plains of western Kansas, trying to assess the effects of irrigation. She’s researching an essay. And then she meets, trespassing on his range, the Marlboro Man.

Not exactly, but Ward is rather iconic. A cowboy, not a sodbuster; a horseman, not a tractor jockey. In some ways, he’s very different from her dirt-farmer father, but like him he epitomizes Kansas itself. He’s also read her first book, the essay collection One Degree West: Reflections of a Plainsdaughter. He’s handsome, sure, but the fact that he reads seals the deal.

Julene, 53 at this point and twice divorced, is long single. Sparks fly between this feminist environmentalist trying to make amends—with Kansas, with its remnant prairie and streams—and this macho cowboy just looking for a sweet ride across Earth’s trampled face. (Politics be damned: this thing between women and men never ends.) You wonder if it’s too late for her son, though; a boy who has always openly craved a father figure, he’s become a rebellious teenager. (And by the way: the High Plains of Kansas haven’t been this well described since Truman Capote ventured west for In Cold Blood.)

Second, you ask—and you can’t help but ask because of Bair’s intent, her narrative craft, Can this progressive woman find lasting love with a Republican cowboy cum livestock equipment salesman?

You read on to see. Bair addresses this aspect in an interview with Map of Kansas Literature:

This book has the “narrative arc” that New York editors and agents always emphasized when I tried to sell books there in the past. I was annoyed by that supposed necessity to write narratively, when much of experience is interior and less linear, but over the course of writing The Ogallala Road, I began to honor that more and more, making choices according to the story’s pulse. You can’t really engage hearts without a story, and you can’t open minds without first opening hearts. I think it was D. H. Lawrence who said that the purpose of the novel is to expand sympathy.

[Julene Bair, High Plains girl.]

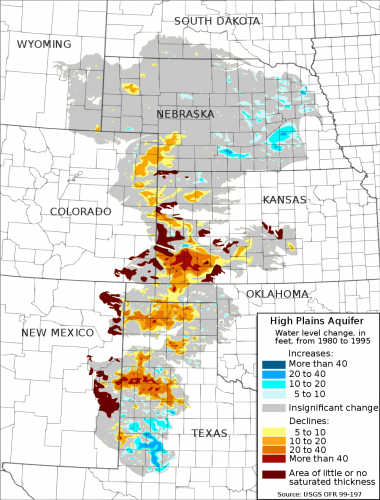

As the romance proceeds, Bair weaves in backstory. Her father having died, she has co-inherited 3,500 acres, the family farm in dry western Kansas, and quit teaching writing to help manage it. As a lover of wilderness, she’s tormented by an old guilt. To grow crops, especially corn, her family and other dry-land farmers from America’s midsection are depleting a vast underground water system. The Ogallala Aquifer stretches from South Dakota to Texas. Farmers are pumping, each year, forty times more liquid than the aquifer needs to recharge itself. Year by year, they must pump from deeper and deeper levels.The scope of this environmental tragedy is what Bair makes clear. The Ogallala Aquifer is the most plentiful source of groundwater in America. Once upon a time, her family and other plains farmers raised livestock on native prairie grasses; using windmills, they and their horses, cows, and sheep sipped sparingly from this unseen river. Later they broke the sod for wheat, which could be planted to take advantage of late-winter and early-spring precipitation. But then government agriculture subsidies—necessary because of America’s cheap food policy—encouraged farmers to grow crops that needed more water. Especially corn, which the government is now encouraging more than ever for ethanol.

We’re all complicit in this. But Bair, and not just her Dad anymore, suddenly was among those actively fueling the conflagration. She dimly remembers, from girlhood, the older, slower, sustainable High Plains realm she desires. The one of the Native Americans and of the first white agrarians who replaced them.

In 2001, the year before she met Ward, she recalls, her family pumped 200 hundred million gallons of water from the Ogallala Aquifer. In one of the book’s compellingly dramatized backstory sections, she portrays her discovery in the mid-1970s, after she’d moved back home for a few years, that her family had pumped 139 million gallons. She’d just emerged from a stint of living in the Mojave Desert and was keenly aware of water’s centrality to life. Outraged, she did the math on her kitchen table: it took over 4,000 gallons of water for every bushel of corn they’d harvested.

Bair confronted her father, who was unmoved. Though they had barely made any money when they sold the corn, federal subsidies put them $10,000 in the black. As a practical businessman, he trusted the government to limit his rapacity, to save the aquifer from him and other farmers. “Don’t despair,” he said. “Big Daddy will put the plug in before it’s too late.”

Use it or lose it! my father used to say whenever I complained about how much he drew out. Kansas, like most dry western states, had a law requiring that those holding water rights take advantage of them to their fullest, or lose what they didn’t use so someone else could access the water before it flowed, or seeped, into the next state. It hadn’t occurred to early legislators that water could be lost through too much use. Now the law was codified by long practice and the rights holders were powerful vested interests with political clout.

Like every American there and elsewhere, she was deeply compromised; unlike most, she knew it. She portrays herself when she moved back home from the Mojave at age 26: no money, no health care, pregnant, a failing marriage to an abusive man—another cowboy. The aquifer, in the form of Dad’s largesse, kept her head above water. Years later, in The Ogallala Road’s foreground narrative, she still yearns for change, a larger awakening so that she’s not alone in enacting more thoughtful land use. As it is, if she convinces her brother, who now manages the land, that they should quit pumping, they’ll likely just go bankrupt. Thanks to the Ogallala Aquifer, she’s able to write full time, partly about its ongoing destruction.

Watching this dilemma play out amidst several dicey human stories, you gallop through The Ogallala Road. Bair keeps the narrative’s reins taut: the fate of the aquifer; the fate of her family’s land; the fate of her unruly son; the fate of her romance.

Her memoir’s environmental aspect hit me hard because after reading it—twice—I happened to read Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change, which makes clear certain implications of Earth’s ongoing and rapidly worsening crisis. Our planet, with its greenhouse atmosphere of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water, naturally traps solar energy; pollution has caused the atmosphere to seize much more. Picture planet Earth as a terrarium with an added heat lamp, which greatly increases evaporation. More energy is trapped in the system, and the weather is getting more violent.

In this new world, wet areas likely will get much wetter; dry places much drier. Average temperature-increase figures can seem trivial because they’re spread over an entire year, including winter, but summers already are getting much hotter. 2014 is forecast to be an El Nino year, when the Pacific Ocean, 40 percent of the Earth’s surface, heats up. And thus 2014 (some say 2015) is expected to be the hottest year in recorded human history.

When the Ogallala Aquifer is gone, what will that mean for people there and for the rest of Americans living in the wake of climate change? Will we truck water into the High Plains so people can live there? Or, with rising fuel prices, and having also drained the lakes and streams that interact with the aquifer, will we abandon the region for thousands of years?

The Ogallala Road, in showing one woman’s and one family’s cruel ecological and economic dilemma, is clarifying and important. It sounds a warning bell, but it is not helpless. Bair is not a helpless person and offers some ideas; she’s a doer, surely a legacy of her father, that dominating, driven, beloved, exasperating, workaholic farmer.

None of us alive today started this fire—the excessive timbering, plowing, draining, and coal-burning—but very soon everyone must help extinguish it.

[Bair has written an Op-Ed for The New York Times, “Running Dry on the Great Plains.” There’s an essay by Bair, “She Poured Out Her Own,” at Terrain.org, about the plight of the Ogallala Aquifer. Next: An interview with Julene Bair about writing her memoir and the aquifer.]

[Irrigation on the High Plains. Image from Terrain.org.]

Love in a thirsty land

[A prairie windmill. Image from Shutterstock.]

Julene Bair’s memoir of romance & eco-tragedy on the prairie.

The Ogallala Road: A Memoir of Love and Reckoning by Julene Bair. Viking, 278 pp.

Bair’s mournful tale is told with resignation, honesty and heartbreak, but also with strength and joy as she shares memories . . . [T]his is a book by a tough, restless, energetic, admirable, principled Kansan who also happens to be a fine writer.—review by Mark Bittman in the New York Times Book Review

We read literature to escape, if only briefly, our own subjective silos. We yearn to piggyback upon someone else’s experience of life. And we seek, as well, clarity: the meaning someone has harvested from her existence—also the order and beauty in that restless act, that hero’s effort to distill coherence from the quotidian.

Here is a story; here is its wisdom.

The wonderful thing about this fine memoir, Julene Bair’s recent The Ogallala Road: A Memoir of Love and Reckoning, is that it shines so brightly in both dimensions. Here is why books remain quietly important. Why they’re still honored in an age of louder, less personal mass media and of jittery, flash-in-the-pan social media.

The Ogallala Road opens with Bair on a quest for water, which she loves, this child of a thirsty landscape. She’s roaming beside a creek in the High Plains of western Kansas, trying to assess the effects of irrigation. She’s researching an essay. And then she meets, trespassing on his range, the Marlboro Man.

Not exactly, but Ward is rather iconic. A cowboy, not a sodbuster; a horseman, not a tractor jockey. In some ways, he’s very different from her dirt-farmer father, but like him he epitomizes Kansas itself. He’s also read her first book, the essay collection One Degree West: Reflections of a Plainsdaughter. He’s handsome, sure, but the fact that he reads seals the deal.

Julene, 53 at this point and twice divorced, is long single. Sparks fly between this feminist environmentalist trying to make amends—with Kansas, with its remnant prairie and streams—and this macho cowboy just looking for a sweet ride across Earth’s trampled face. (Politics be damned: this thing between women and men never ends.) You wonder if it’s too late for her son, though; a boy who has always openly craved a father figure, he’s become a rebellious teenager.

Second, you ask—and you can’t help but ask because of Bair’s intent, her narrative craft, Can this progressive woman find lasting love with a Republican cowboy cum livestock equipment salesman?

You read on to see. Bair addresses this aspect in an interview with Map of Kansas Literature:

This book has the “narrative arc” that New York editors and agents always emphasized when I tried to sell books there in the past. I was annoyed by that supposed necessity to write narratively, when much of experience is interior and less linear, but over the course of writing The Ogallala Road, I began to honor that more and more, making choices according to the story’s pulse. You can’t really engage hearts without a story, and you can’t open minds without first opening hearts. I think it was D. H. Lawrence who said that the purpose of the novel is to expand sympathy.

[Julene Bair, High Plains girl.]

As the romance proceeds, Bair weaves in backstory. Her father having died, she has co-inherited 3,500 acres, the family farm in dry western Kansas, and quit teaching writing to help manage it. As a lover of wilderness, she’s tormented by an old guilt. To grow crops, especially corn, her family and other dry-land farmers from America’s midsection are depleting a vast underground water system. The Ogallala Aquifer stretches from South Dakota to Texas. Farmers are pumping, each year, forty times more liquid than the aquifer needs to recharge itself. Year by year, they must pump from deeper and deeper levels.The scope of this environmental tragedy is what Bair makes clear. The Ogallala Aquifer is the most plentiful source of groundwater in America. Once upon a time, her family and other plains farmers raised livestock on native prairie grasses; using windmills, they and their horses, cows, and sheep sipped sparingly from this unseen river. Later they broke the sod for wheat, which could be planted to take advantage of late-winter and early-spring precipitation. But then government agriculture subsidies—necessary because of America’s cheap food policy—encouraged farmers to grow crops that needed more water. Especially corn, which the government is now encouraging more than ever for ethanol.

We’re all complicit in this. But Bair, and not just her Dad anymore, suddenly was among those actively fueling the conflagration. She dimly remembers, from girlhood, the older, slower, sustainable High Plains realm she desires. The one of the Native Americans and of the first white agrarians who replaced them.

In 2001, the year before she met Ward, she recalls, her family pumped 200 hundred million gallons of water from the Ogallala Aquifer. In one of the book’s compellingly dramatized backstory sections, she portrays her discovery in the mid-1970s, after she’d moved back home for a few years, that her family had pumped 139 million gallons. She’d just emerged from a stint of living in the Mojave Desert and was keenly aware of water’s centrality to life. Outraged, she did the math on her kitchen table: it took over 4,000 gallons of water for every bushel of corn they’d harvested.

Bair confronted her father, who was unmoved. Though they had barely made any money when they sold the corn, federal subsidies put them $10,000 in the black. As a practical businessman, he trusted the government to limit his rapacity, to save the aquifer from him and other farmers. “Don’t despair,” he said. “Big Daddy will put the plug in before it’s too late.”

Use it or lose it! my father used to say whenever I complained about how much he drew out. Kansas, like most dry western states, had a law requiring that those holding water rights take advantage of them to their fullest, or lose what they didn’t use so someone else could access the water before it flowed, or seeped, into the next state. It hadn’t occurred to early legislators that water could be lost through too much use. Now the law was codified by long practice and the rights holders were powerful vested interests with political clout.

Like every American there and elsewhere, she was deeply compromised; unlike most, she knew it. She portrays herself when she moved back home from the Mojave at age 26: no money, no health care, pregnant, a failing marriage to an abusive man—another cowboy. The aquifer, in the form of Dad’s largesse, kept her head above water. Years later, in The Ogallala Road’s foreground narrative, she still yearns for change, a larger awakening so that she’s not alone in enacting more thoughtful land use. As it is, if she convinces her brother, who now manages the land, that they should quit pumping, they’ll likely just go bankrupt. Thanks to the Ogallala Aquifer, she’s able to write full time, partly about its ongoing destruction.

Watching this dilemma play out amidst several dicey human stories, you gallop through The Ogallala Road. Bair keeps the narrative’s reins taut: the fate of the aquifer; the fate of her family’s land; the fate of her unruly son; the fate of her romance.

Her memoir’s environmental aspect hit me hard because after reading it—twice—I happened to read Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change, which makes clear certain implications of Earth’s ongoing and rapidly worsening crisis. Our planet, with its greenhouse atmosphere of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water, naturally traps solar energy; pollution has caused the atmosphere to seize much more. Picture planet Earth as a terrarium with an added heat lamp, which greatly increases evaporation. More energy is trapped in the system, and the weather is getting more violent.

In this new world, wet areas likely will get much wetter; dry places much drier. Average temperature-increase figures can seem trivial because they’re spread over an entire year, including winter, but summers already are getting much hotter. 2014 is forecast to be an El Nino year, when the Pacific Ocean, 40 percent of the Earth’s surface, heats up. And thus 2014 (some say 2015) is expected to be the hottest year in recorded human history.

When the Ogallala Aquifer is gone, what will that mean for people there and for the rest of Americans living in the wake of climate change? Will we truck water into the High Plains so people can live there? Or, with rising fuel prices, and having also drained the lakes and streams that interact with the aquifer, will we abandon the region for thousands of years?

The Ogallala Road, in showing one woman’s and one family’s cruel ecological and economic dilemma, is clarifying and important. It sounds a warning bell, but it is not helpless. Bair is not a helpless person and offers some ideas; she’s a doer, surely a legacy of her father, that dominating, driven, beloved, exasperating, workaholic farmer.

None of us alive today started this fire—the excessive timbering, plowing, draining, and coal-burning—but very soon everyone must help extinguish it.

[Bair has written an Op-Ed for The New York Times, “Running Dry on the Great Plains.” There’s an essay by Bair, “She Poured Out Her Own,” at Terrain.org, about the plight of the Ogallala Aquifer. Next: An interview with Julene Bair about writing her memoir and the aquifer.]

[Irrigation on the high plains. Image from Terrain.org.]

May 19, 2014

Wounded family

From Our House: A Memoir by Lee Martin. Bison Books, 192 pp.

Lee Martin’s From Our House has an honored place in my aesthetic pantheon and in my heart. I’ve read it four times over the years. It concerns his growing up with a rageful father, who had lost both hands in a farming accident, and a meek schoolteacher mother. She stood by, helpless to stop her husband’s harsh treatment of their son, unable to protect young Lee from Roy Martin’s mean words and brutal whippings.

Despite its easygoing narrative, rich in plot yet also feeling searchingly essayistic, this portrait of one troubled family possesses a riveting force. You sense that the surface events unfolding as Lee grows up reflect his family’s deep inner struggle to transcend its patriarch’s physical and psychic wounds. Martin evokes his experience in scenes while also slipping into the action musings by his older and wiser self. For one price, we get two points of view—that of the sensitive, difficult boy and that of the wiser adult he became.

This dual quality, layering the story and enriching the reader’s understanding of it, exists in Martin’s narration even when the retrospective writer’s presence is subtle. In this passage, set when Lee expects a beating from his father for refusing to attend his grandmother’s burial, you can also feel the story’s deep sepia tones, timeless air, and bygone setting:

I heard my father’s voice break, and it startled me. I pulled my head out from under my pillow and saw him lying on his back, his eyes closed, his hooks clasped on top of his stomach. “When I die,” he had said, as we had left my grandma’s wake, “everyone will come just to see if they bury me with these hooks.” It was, perhaps, the first time I understood that my father, so much older than my friends’ fathers, might die while I was young. And though he was the man who whipped me, he was my father, and freedom from him would carry with it an everlasting guilt, a regret that we hadn’t found a way to love each other more.

It was impossible for me to snuggle in close to him, because of his hooks, but I moved as close as I could and felt the heat from his body.

“We have to go,” he said. “You know that, don’t you?”

I didn’t answer. In a while, he would ask me if I was ready, and we would rise and go to the funeral home. But for the moment, we lay there, the two of us alone, while the rooster crowed again and my father said, “Good morning,” as if we were just then waking to a new day.

Quiet but resonant, this scene shows his father not as a hook-armed monster but as another suffering human—and as the kindly man he tried to be.

[Lee Martin: memoir master.]

It wasn’t until my third reading of From Our House that I realized consciously how much I identify with it because of my own boyhood. I cannot help but think of my parents, my siblings, and myself when I read it. In my memoir, Shepherd, I write about growing up with a father scarred by his own father. Dad was 14 on the day he came upon him, violently slain by his own hand. Dad wasn’t an angry man as a result, though he told me once that he hated his father for years, but he was a depressive and isolated one. He seemed utterly apart from others; I had no sense he was moving through life with us. I should have blamed my grandfather for my father’s ways, I suppose, but that’s what I came to know intellectually rather than what I felt.My mother was the present parent—our only real parent—but also the angry one. The one who lashed out with bony hands, leather belts, and belittling words. For years I assumed this was simply her nature, or her response to my absent father, or her frustration with my schoolboy defiance of her. Maybe it was all of that. But as Mom aged she revealed that her attack parenting had been how her mother had reared her and her siblings long ago in Oklahoma. I began to see her and my favorite uncle—a man still hurting in old age from his mother’s lack of expressed love—in a new light.

Throughout From Our House, the boy’s experience and the writer’s understanding show how pain, regret, and anger—helplessly entwined with love—can ripple forever inside people from dysfunctional families. This can be passed on, an enduring emotional legacy—like the gift of a happy childhood, though of course different in effect. Mary Karr summed up this reverberating blow in her memoir Lit (reviewed):

When you’ve been hurt enough as a kid (maybe at any age), it’s like you have a trick knee. Most of your life, you can function as an adult, but add in the right proportions of sleeplessness and stress and grief, and the hurt, defeated self can bloom into place.

What makes this fate so painful is that sufferers know old wounds can warp them in the present; their burden clouds when and how and whether they act and express themselves in the world. How can you be properly and maturely assertive when your pain and your parental example want aggression—or passivity? But no matter how justified negative emotions feel, any adult who experiences them knows they’re toxic. This dilemma is captured in the Cherokee-cum-generic-Native American parable “The Wolf You Feed,” which has gone viral in various versions, this one from The Daily Kos:

An elder Native American was teaching his grandchildren about life. He said to them, “A fight is going on inside me. It is a terrible fight and it is between two wolves. One wolf represents fear, anger, envy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.

“The other stands for joy, peace, love, hope, sharing, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, friendship, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith.

“This same fight is going on inside you, and inside every other person, too,” he added.

The Grandchildren thought about it for a minute and then one child asked his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?”

The old Cherokee simply replied, “The one you feed.”

I saw my parents grow as the years passed. People can and do change, if they try and if they don’t. Just so, Martin depicts his ill family slowly begin to heal and become whole. This is where From Our House amazes in its particulars and in his telling. Martin credits his mother, who may have been too submissive toward his father, but, sweet and steadfast, she never gave up:

Where would we have been without her eternal optimism? Though she had stood by, silent, while my father had whipped me when I was a child, she had at least always believed—and somehow had made me believe—that our lives were worth more than the shabby way we often treated them. She lacked the courage to confront my father’s rage or to escape it, but she endured, and by doing so, she slowly began to win the long battle for goodness that was the history of our family.

A top-five memoir. Written with palpable tenderness and love for both parents, From Our House awes me with its graceful execution, from its perfect pace to its lovely prose. Sad, wise, and inspiring, this hopeful story testifies to love’s resilient power.

You know Martin is lucky to have had his parents, not cursed, just as we’re now lucky to have his work.

[Previously I reviewed and interviewed Martin about his memoir essay collection, Such a Life, and reported on his talk to one of my classes that had read Such a Life.]

May 13, 2014

Tending what remains

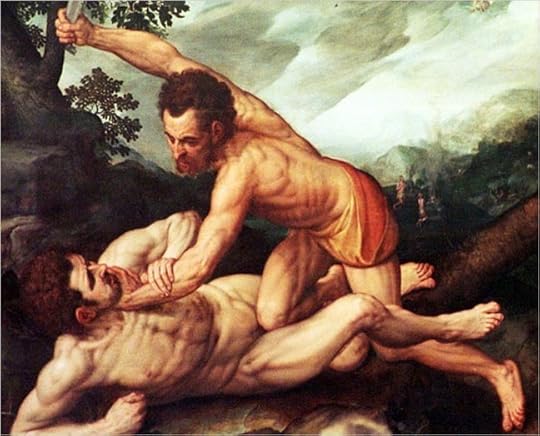

[Cain, a crop farmer and Earth's firstborn, kills his brother Abel, a shepherd.]

Are we intrinsically hostile to Mother Earth? Can we save her?

I was concerned going into my panel Saturday, “Return to Nature: Nonfiction,” at the Ohioana Book Festival. Although farming still brings many of its practitioners into intimate daily contact with the natural world, farming is now seen mostly as hostile to nature. A necessary evil, at best. Yet so much else seems grandfathered in its deleterious environmental effects! Am I being thin-skinned here? I can’t tell.

[Ohio University Press Director Gillian Berchowitz visits me at Ohioana Book Festival.]

As a former farmer and author of a book that portrays farming, I’m sure of one thing. Farming has become an exotic activity in America. People have heard too much to fully trust the mainstream, which engages in what’s become mysterious. But those seeking alternatives often seem lost. There they stand, looking at labels—pay extra for organic? what does grass-raised mean? are cage-free eggs better? And I’m among the uncertain: the man who knows too much. I know that organic farms are only as good as the farmers who run them. That such farms can be a sham, abuse the environment. And I fret about monster farms taking over the value-added organic market.On balance, I’ve decided, a vote for organic-sustainable-pastoral-humane methods, the odd scammer among them notwithstanding, is a vote for a better system and will foster its emergence. Surely we’re all coming to know these things.

Such musing didn’t prepare me for my session with my lone fellow panelist (our third speaker was a no-show). A panel on nature and farming can mean anything. I was wondering about reading one of my rapturous landscape descriptions, when the moderator’s introduction turned me in a different direction.

I had yearned to farm, I heard myself saying, after my father’s loss of my boyhood farm. After my discovery as a teenager of Pleasant Valley and Malabar Farm, by Louis Bromfield, two of the most romantic (and nature-saturated) books ever written about agriculture. I spoke of landing in Appalachian Ohio, an ecologically abused region where 1970s hippie back-to-landers rooted and which was being touted as a pastoral Mecca by The Stockman Grassfarmer.

“I have a different view,” began Frank W. Porter, author of a lovely little book, Back to Eden: Landscaping with Native Plants.

Frank runs a nursery, Porterbrook Native Plants, in impoverished Meigs County, Ohio, which abuts where my book, Shepherd: A Memoir, is set, in Athens County. Since his book is coded Gardening / Native Plants / Eastern U.S. and mine is coded Nature and Animals / Horticulture / Memoir, they’ll probably be shelved near each other in bookstores.

Frank, who himself epitomized my just-expressed vision of southeastern Ohio’s alternative culture, said people there were as ignorant about plants as anyplace else. Fair enough. Does a tiny minority offset America’s juggernaut culture? Frank’s rebuke stung, all the same—I’m an avid planter of native species, and my father, in retirement, ran a successful native-plants nursery in Florida.

Below the simmering conflict I sensed between Frank and me may have been the issue of native plants and farming. Aside from farming’s presumed hostility to nature, it likes exotics. Just to name a few livestock species being raised in America which didn’t originate here: cattle, sheep, swine, chickens. Look out the window. Every blade of grass you see isn’t native: the South’s Bermuda grass came from Africa; Kentucky 31 fescue, which grows almost everywhere East of the Mississippi, came from Europe; ditto for Bluegrass—and dandelions and plantain.

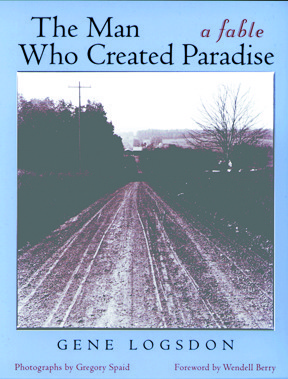

[Gene Logsdon’s agrarian eco-fable.]

And Frank, a Native American himself, has declared war on exotic species. Rip out your non-natives and plant natives, he urged; natives attract birds and butterflies, and neighbors seeing this transformation will ape you—changing whole neighborhoods. He reminded me of The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono, a sublime fable about reversing desertification. I might have told him that Gillian Berchowitz and I published, 13 years ago, under the imprint of Swallow Press, Gene Logsdon’s takeoff on that book, The Man Who Created Paradise, which is set in strip-mined southern Ohio landscapes.

In Shepherd I depict my sweaty, bloody efforts to clear multiflora rose thickets. I beat them back, on my land. The rampant Asian species, promoted in the 1940s by the U.S. Soil Conservation Agency and Louis Bromfield, cannot be eradicated, however. Probably no exotic species that successfully establishes can be wiped out. Right now, the Emerald Ash Borer, from Asia, is busy killing every ash tree in Ohio. And as I write, Asian stinkbugs are creeping around my living room’s crown molding over my head. My family knows my obsession with the fact that Florida’s Everglades are crawling with giant Asian and some African boa constrictors. They’re crossbreeding—not only exotics but a new hybrid species.

But as a guilty former exotic-grass-growing farmer, I knew how deep Frank’s argument truly went. What he really was talking about. The Fall. Which is inescapably tied to Homo sapiens’ turn to agriculture some 10,000 years ago. Now, as the Bible has it, we dwell not in Eden, an effortless cornucopia, but must earn our bread “in the sweat of our faces.”

[Farming as the Fall.]

With my “Green Thoughts” class this semester at Otterbein University, I read the visionary novel Ishmael—1.5 million copies in print!—in which author Daniel Quinn depicts a genius gorilla who explains this shift to a human pupil. With farming, Ishmael says, we became Takers, and began to destroy the Earth and its native peoples, the Leavers. It’s a powerful parable, right out of the Bible’s Book of Genesis in which crop farmer Cain, Adam and Eve’s firstborn—thus the first human born—killed his brother Abel, the second-born, a wandering herder. Which means he was a shepherd, folks. The first murderer, a tiller; the first murder victim, a gentle pastoralist. I find it fascinating, of course, that my ilk is Biblically portrayed as a compromise between Edenic hunter-gatherers and evil dirt farmers.But farming, it must be said, fueled the risen glory of human civilization. And having grown our numbers so, hunting and gathering won’t quite cut it. Nor will pastures alone feed us. This is a tough nut to crack, folks. Ishmael may be right, but who ya gonna call?

While Frank exhorted our listeners to rip out their Butterfly Bush and plant the native version, maybe Butterfly Weed, and even to eschew even their beloved hostas, I thought of the idiocy of a local group that rips out invasive Japanese honeysuckle from the banks of nearby Alum Creek. This makes them feel virtuous and creates instant erosion problems. To their credit, they sometimes plant a few natives, dogwood and redbud and such, a few of which survive—in areas heavily trafficked by mowing, weed-whacking humans.

Plant natives, sure—but enjoy your hostas, I almost cried out. Take some pleasure in one of England’s largely benign gifts, the herbaceous perennial border.

“We have to do something about global warming,” is what I did say.

How mightily I trumped Frank—how easily that’s done in these matters—and he’s working more actively to solve this puzzle than I am. But climate change really is my current obsession, and it has been fueled by my recent reading. Our assault on Earth has led us to the here and now, to a place where we’re reaping our planet’s revenge.

Meantime, I bought Frank’s book. He signed it for me, “Go native!” He didn’t buy mine. But he did visit my booth at the end of the day and shake my hand.

[Next: Irrigation, Memoir, and Global Warming.]

April 30, 2014

Rock me—publication day!

![[Paige and Haley celebrate as Amazon.com delivers my book early.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1399016622i/9498604._SX540_.jpg)

[Paige and Haley celebrate as Amazon.com delivers my book early.]

Seven long years. Six complete versions. Yo: Shepherd: A Memoir.

Otterbein University, in Westerville, Ohio, is chock-full of the nicest kids I’ve ever known. And Paige Schortgen and Haley Young, former writing students of mine, are two of the nicest. Which makes them, in fact, two of the nicest girls in the entire world. (Good writers, too.) Their geeked-out celebration selfie above is the best reaction my book has provoked so far. (Other readers, your mileage may vary.) My little world is so much larger and warmer with such folks in it. Girls, you are funny, kind, and definitely keepers.

Though Amazon began selling the book on or about April 15, the official publication date of Shepherd: A Memoir is today, May 1, 2014.

I’m not sure I can send the treasured photo of my student friends to booksellers as proof they should stock my book. So Shepherd’s review in Kirkus carries a tad more weight in the book world.

Here’s a chunk of what Kirkus said:

[2005: Starting book.]

Gilbert ruminates warmly on his artisanal flock, seeing the hidden beauty of his sheep. He also recalls his collection of farm implements: an old post pounder, a used cultivator, a small tractor—accompaniments to the never-ending work that was especially backbreaking for someone with a day job in town. Gilbert is especially astute in his portrayals of his Appalachian neighbors, who were mostly good folk. His farm logs are studies in animal husbandry, proper fencing, house building, birth and decay. His prose is pungent: In a sheep barn, he notes, the air was humid with an amalgam of “mellow musk, tangy manure, bitter urine, sweet hay.” He writes of digging out aged offal, of tenant rats, and of the hundreds of natural shocks that man and beast may encounter. . . . In a sometimes-earthy, sometimes-prolix and ultimately sagacious elegy, Gilbert speaks of descent into pain and fear as well as of the beauty of bucolic nature and the diverse traits of agrarian man.

A thoughtful memoir of rams and ewes, farmers and family, life and death.

What a wise and gracious review. Dad used to say of such outcomes, “That’s better than a sharp stick in the eye.”

Indeed. And as such matters go, it’s almost a rave. So “sometimes-prolix” didn’t make me wince. A writer friend remarked, “Most people won’t know what ‘prolix’ means and will think it’s a compliment.” Prolix: “Extended to great, unnecessary, or tedious length.” That’s me all over. As any reader of this blog can confirm. One of my writing defaults seems to be that storytelling is like selling ears of sweet corn by the dozen at a farm stand: you throw in extra!

I’m grateful to and rather in awe of the anonymous reviewer. S/he managed generously to overlook topics s/he might have harped on—what I might be fairly said to harp on—and instead pulled way back to see the story entire and to summarize it without undue distortion. That’s hard. Especially in a review that’s anything but prolix.

On the heels of this favorable notice, comes an excerpt in Utne Review. They ran my book’s Prologue in its entirety. As an excerpt, it would seem to leave readers hanging—the Prologue is designed to send readers deeper into the book—but maybe they’ll click on over to Amazon and order it, just to relieve their unbearable narrative tension. Or to satisfy their morbid curiosity.

[2006: With Freckles's lambs.]

Writers tend to think excerpts will just happen when their book appears, but in my experience in book publicity, they’re rare. Magazine editors don’t know your book, and won’t take time to patch something together. (Hence Utne’s approach with mine.) Even if an author or publicist hands them a cohesive excerpt, it must then compete with any other piece clamoring for their attention. Just being from a book won’t help, and in fact may hurt, unless the author is famous or the book extremely newsworthy.

In its approximately twelfth and final Prologue, my book opens:

Childhood dreams cast long shadows into a life. As if the strong feelings they stir prove their validity, dreams propel the dreamer through an indifferent world. Which explains how I, a guy who grew up in a Florida beach town, find myself crouched beside a suffering sheep in an Appalachian pasture.

“Richard, I think you should call the vet,” says my wife. Kathy and I flank the ewe’s prostrate body.

Our third lambing has just begun this spring of 2001, and Red is in trouble. I’d found the little ewe in distress and had urged her up and nudged her inside an old shed, where she’d collapsed and resumed straining, panting as if in labor. But nothing happens; no lambs, hour after hour. . . .

So I relent and call Maggie Swenson this Sunday afternoon. She arrives as heavy shadows from hickory and locust trees fall across the pasture. Maggie announces after a quick check that Red’s cervix isn’t dilated, and then she sits back with a puzzled frown on her elfin face. Red sure appears to be in labor.

Over at Sunny Room Studio, Daisy Hickman has run a wide-ranging interview with me about Shepherd, farming, writing, teaching, and spirituality.

With Shepherd’s dribs and drabs of attention, maybe independent bookstores and even Barnes & Noble will stock it. If so, look for it in the gardening or nature section. Although it’s a literary memoir and not how-to (more like how-don’t), it is categorized on the back cover Nature and Animals / Horticulture / Memoir. Those are the labels that influence booksellers regarding where to shelve it. I asked my publisher to use such codes because I’ve noticed that memoirs come and go rather quickly in stores, and I believe it may sell if back-to-the-land types come across it.

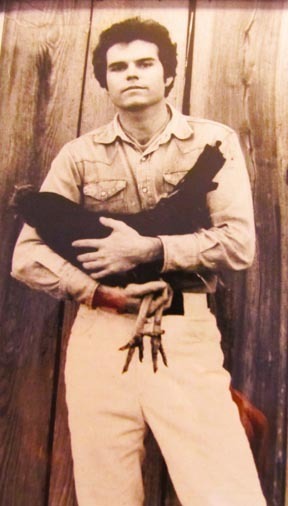

[1978: Rural leanings, at 22.]

Tonight I read at Paging Columbus, a literary event series in Ohio State University’s Urban Arts Space downtown. It’s a sleek gallery venue, rife with talented poets. The host and organizer, Hannah Stephenson is author of the poetry collection In the Kettle, the Shriek, and I share the stage with two other accomplished young poets up from Cincinnati, Rochelle Hurt, author of the prose-poem and verse narrative The Rusted City, and Julia Koets, author of Hold Like Owls, winner of the 2011 South Carolina Poetry Book Prize. Rush-hour traffic and parking angst precedes my appearance. (Kathy’s driving.) On Saturday I’m part of the Westerville Public Library’s Local Author Book Festival. And on Sunday I read and sign books at Courtright Memorial Library of Otterbein University.

Later this month my book and I participate in one of Ohio’s greatest cultural assets, the Ohioana Book Festival. I’ve always envied the way the South gets behind southern authors’ books—while in Ohio, Cleveland is apt to ignore a book by a Cincinnati author—but the Ohioana book fest and The Ohoiana Quarterly, which solely reviews books by Buckeye-inflected authors, are glaring exceptions.

Meantime, I’ve mailed some early author copies to family and friends. And been made aware that about half the time, busy filling out envelopes or jotting the recipient a note, I forgot to inscribe the enclosed book! What’s happening to me?

Oh, I’m pleased, sure—yet somehow terrified by attention. No biggie, I tell myself. Just a blip in so many phases in this life. Mere moments, really. Chances to celebrate. Sometimes a tad much, though, for an introvert. Despite how willfully, carefully, and officially he’s dramatized himself.

Well, heck. What did I expect? Author Michael Perry likens writing to cleaning out calf pens on his father’s dairy farm: if you keep shoveling, eventually you’ll have a pile big enough that folks notice.

But it’s hard to believe. All those solitary years at a desk led to this? Upon consideration: Thank goodness they led to something.

Rock me mama like the wind and the rain

Rock me mama like a south-bound train

Hey mama, rock me . . .

Rock me mama like a wagon wheel

Rock me mama any way you feel

Hey mama, rock me.

—“Wagon Wheel,” written by Bob Dylan & Ketch Secor

[Listen: Old Crow Medicine Show plays its epic “Wagon Wheel”—there’s hardly anything more heartbreakingly lovely than these boys’ banjo-inflected harmonies and their old-timey fiddle. What a joyous, resonant tune. It makes me proud to be an American, a Dylan fanatic, and a once and future southern boy.]

April 22, 2014

Lie, steal, remake?

[Up for the first time: My daffodils making the eternal Spring new.]

How ‘lying’ and remaking spur creativity in fiction & nonfiction.

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

—from “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth

[Blues icon Big Mama Thornton.]

As a lifelong writing student, I’ve resisted writing prompts—a lazy doubting stubbornness that’s fading as I see repeatedly in my classes their utility and power. Spurred by an exercise, my “Writing Life Stories” students have just produced some of their best work of the semester.Here’s the prompt, “Tell a Lie, Tell the Truth,” from Lee Martin. I got it from his wonderful blog (I’ve probably changed some of the wording for my students, who by and large are not writing majors and are taking their first creative writing class of any kind):

1. Open a piece of creative nonfiction by telling a lie about yourself. Don’t stop to think. Just go with the first thing that comes to you. Be as outrageous as you’d like.

2. Admit the lie, using this prompt: “That’s not true at all. The truth is. . .”

3. Embrace the lie, using this prompt: “Oh, but how I wish it were true, for if it were. . .”

4. Let the lie bring material to the surface that you might be hesitant to explore otherwise by using this prompt: “Why would I spin a lie like that? When I think of that lie, I also think of. . .”

*The objective is to let fiction (the lie) provide a doorway into truths about your life that you might not otherwise notice. This can sometimes open our material to us in profound ways.

Though I can’t stop thinking about some of them, I won’t retell the stories my students told. But suffice it to say that their essays’ opening lies—in their yearning and often-iconic specifics, images maybe borderline trite in a straight usage—take on such power, resonance, and frequently sadness as we learn the truth. Yet the retrospective wisdom fostered by the nature and placement of the truth-telling narrator makes it all moving but emotionally bearable, and a gift.

Over at Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, Bill Roorbach takes lying or simple appropriation to new creative heights in his “Bad Advice Wednesday: Remake.” He says to take a story or essay you admire and retell it in your own way.

By stealing in this post, I’ve sort of done that. Except my two sources are advising more ultimate originality than I’m displaying here so far. One says, Tell a lie and immediately admit it and speculate on it, revealing who you really are; the other says, Steal a plot and write the heck out of it and watch it become your creation, even unto plot.

It strikes me that a perfect example of what Bill Roorbach, at least, is talking about is essayist and essay scholar Robert Atwan’s recent brilliantly conceived and executed re-imaging of The Great Gatsby, the story retold from Tom Buchanan’s viewpoint for The Believer.

Meanwhile, Lee Martin has posted on his blog, The Least You Need to Know, what’s more than a post: it’s a flash essay, “An Easter Sunday Memory,” only 441 words; it is a poignant tableau of 10-year-old him and his parents eating out at a restaurant, with powerful use of the retrospective view at the end as Lee pulls the camera way, way back.

As I told him, I think there’s a future prompt here!

Such as:

Read Lee Martin’s flash essay “An Easter Sunday Memory,” and write your own vignette that takes place during a holiday; start in scene and flow background explanations into the unfolding action; step back at the end and speak from now, from your wisdom of what your characters don’t know awaits them.