Tending what remains

[Cain, a crop farmer and Earth's firstborn, kills his brother Abel, a shepherd.]

Are we intrinsically hostile to Mother Earth? Can we save her?

I was concerned going into my panel Saturday, “Return to Nature: Nonfiction,” at the Ohioana Book Festival. Although farming still brings many of its practitioners into intimate daily contact with the natural world, farming is now seen mostly as hostile to nature. A necessary evil, at best. Yet so much else seems grandfathered in its deleterious environmental effects! Am I being thin-skinned here? I can’t tell.

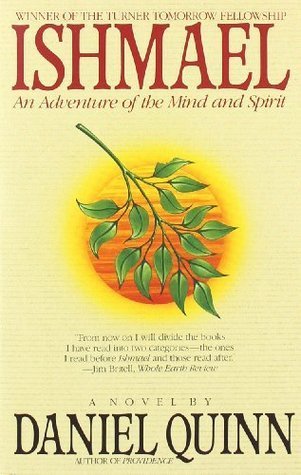

[Ohio University Press Director Gillian Berchowitz visits me at Ohioana Book Festival.]

As a former farmer and author of a book that portrays farming, I’m sure of one thing. Farming has become an exotic activity in America. People have heard too much to fully trust the mainstream, which engages in what’s become mysterious. But those seeking alternatives often seem lost. There they stand, looking at labels—pay extra for organic? what does grass-raised mean? are cage-free eggs better? And I’m among the uncertain: the man who knows too much. I know that organic farms are only as good as the farmers who run them. That such farms can be a sham, abuse the environment. And I fret about monster farms taking over the value-added organic market.On balance, I’ve decided, a vote for organic-sustainable-pastoral-humane methods, the odd scammer among them notwithstanding, is a vote for a better system and will foster its emergence. Surely we’re all coming to know these things.

Such musing didn’t prepare me for my session with my lone fellow panelist (our third speaker was a no-show). A panel on nature and farming can mean anything. I was wondering about reading one of my rapturous landscape descriptions, when the moderator’s introduction turned me in a different direction.

I had yearned to farm, I heard myself saying, after my father’s loss of my boyhood farm. After my discovery as a teenager of Pleasant Valley and Malabar Farm, by Louis Bromfield, two of the most romantic (and nature-saturated) books ever written about agriculture. I spoke of landing in Appalachian Ohio, an ecologically abused region where 1970s hippie back-to-landers rooted and which was being touted as a pastoral Mecca by The Stockman Grassfarmer.

“I have a different view,” began Frank W. Porter, author of a lovely little book, Back to Eden: Landscaping with Native Plants.

Frank runs a nursery, Porterbrook Native Plants, in impoverished Meigs County, Ohio, which abuts where my book, Shepherd: A Memoir, is set, in Athens County. Since his book is coded Gardening / Native Plants / Eastern U.S. and mine is coded Nature and Animals / Horticulture / Memoir, they’ll probably be shelved near each other in bookstores.

Frank, who himself epitomized my just-expressed vision of southeastern Ohio’s alternative culture, said people there were as ignorant about plants as anyplace else. Fair enough. Does a tiny minority offset America’s juggernaut culture? Frank’s rebuke stung, all the same—I’m an avid planter of native species, and my father, in retirement, ran a successful native-plants nursery in Florida.

Below the simmering conflict I sensed between Frank and me may have been the issue of native plants and farming. Aside from farming’s presumed hostility to nature, it likes exotics. Just to name a few livestock species being raised in America which didn’t originate here: cattle, sheep, swine, chickens. Look out the window. Every blade of grass you see isn’t native: the South’s Bermuda grass came from Africa; Kentucky 31 fescue, which grows almost everywhere East of the Mississippi, came from Europe; ditto for Bluegrass—and dandelions and plantain.

[Gene Logsdon’s agrarian eco-fable.]

And Frank, a Native American himself, has declared war on exotic species. Rip out your non-natives and plant natives, he urged; natives attract birds and butterflies, and neighbors seeing this transformation will ape you—changing whole neighborhoods. He reminded me of The Man Who Planted Trees, by Jean Giono, a sublime fable about reversing desertification. I might have told him that Gillian Berchowitz and I published, 13 years ago, under the imprint of Swallow Press, Gene Logsdon’s takeoff on that book, The Man Who Created Paradise, which is set in strip-mined southern Ohio landscapes.

In Shepherd I depict my sweaty, bloody efforts to clear multiflora rose thickets. I beat them back, on my land. The rampant Asian species, promoted in the 1940s by the U.S. Soil Conservation Agency and Louis Bromfield, cannot be eradicated, however. Probably no exotic species that successfully establishes can be wiped out. Right now, the Emerald Ash Borer, from Asia, is busy killing every ash tree in Ohio. And as I write, Asian stinkbugs are creeping around my living room’s crown molding over my head. My family knows my obsession with the fact that Florida’s Everglades are crawling with giant Asian and some African boa constrictors. They’re crossbreeding—not only exotics but a new hybrid species.

But as a guilty former exotic-grass-growing farmer, I knew how deep Frank’s argument truly went. What he really was talking about. The Fall. Which is inescapably tied to Homo sapiens’ turn to agriculture some 10,000 years ago. Now, as the Bible has it, we dwell not in Eden, an effortless cornucopia, but must earn our bread “in the sweat of our faces.”

[Farming as the Fall.]

With my “Green Thoughts” class this semester at Otterbein University, I read the visionary novel Ishmael—1.5 million copies in print!—in which author Daniel Quinn depicts a genius gorilla who explains this shift to a human pupil. With farming, Ishmael says, we became Takers, and began to destroy the Earth and its native peoples, the Leavers. It’s a powerful parable, right out of the Bible’s Book of Genesis in which crop farmer Cain, Adam and Eve’s firstborn—thus the first human born—killed his brother Abel, the second-born, a wandering herder. Which means he was a shepherd, folks. The first murderer, a tiller; the first murder victim, a gentle pastoralist. I find it fascinating, of course, that my ilk is Biblically portrayed as a compromise between Edenic hunter-gatherers and evil dirt farmers.But farming, it must be said, fueled the risen glory of human civilization. And having grown our numbers so, hunting and gathering won’t quite cut it. Nor will pastures alone feed us. This is a tough nut to crack, folks. Ishmael may be right, but who ya gonna call?

While Frank exhorted our listeners to rip out their Butterfly Bush and plant the native version, maybe Butterfly Weed, and even to eschew even their beloved hostas, I thought of the idiocy of a local group that rips out invasive Japanese honeysuckle from the banks of nearby Alum Creek. This makes them feel virtuous and creates instant erosion problems. To their credit, they sometimes plant a few natives, dogwood and redbud and such, a few of which survive—in areas heavily trafficked by mowing, weed-whacking humans.

Plant natives, sure—but enjoy your hostas, I almost cried out. Take some pleasure in one of England’s largely benign gifts, the herbaceous perennial border.

“We have to do something about global warming,” is what I did say.

How mightily I trumped Frank—how easily that’s done in these matters—and he’s working more actively to solve this puzzle than I am. But climate change really is my current obsession, and it has been fueled by my recent reading. Our assault on Earth has led us to the here and now, to a place where we’re reaping our planet’s revenge.

Meantime, I bought Frank’s book. He signed it for me, “Go native!” He didn’t buy mine. But he did visit my booth at the end of the day and shake my hand.

[Next: Irrigation, Memoir, and Global Warming.]