Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 14

January 8, 2014

Joshua Cody’s memoir [sic]

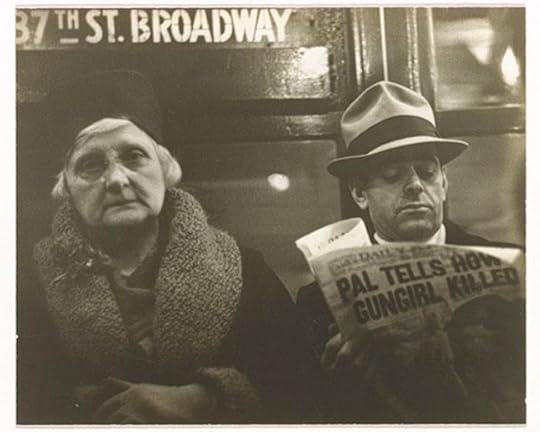

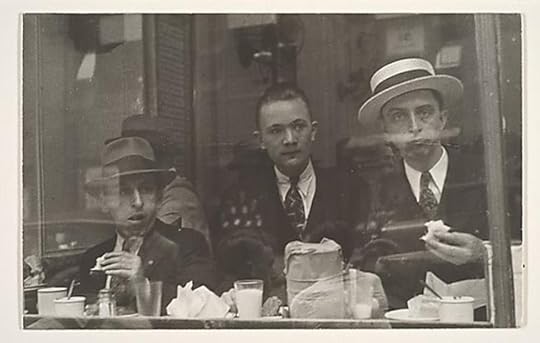

[“Subway Passengers,” 1938, by Walker Evans.]

[“Subway Passengers,” 1938, by Walker Evans.]A memoirist’s risky performance draws praise & provokes rage.

[sic]: A Memoir by Joshua Cody. Norton, 259 pp.

The first two times I opened [sic]: A Memoir, I was impressed by Joshua Cody’s sentences—cool, syntactically complex, allusive. But I didn’t keep reading it because I was working on my own book and sensed immediately that his high-flying persona was at odds with my attempt at a sincere one.

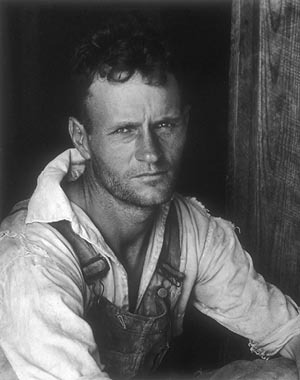

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]Late in 2013 I made it through [sic] and admired it, so refreshingly different from my own writing—or almost anyone’s. I wouldn’t try such a performance and couldn’t sustain one for long if I did. A possible cost of Cody’s approach is that I always felt distanced from him. How much “knowing” and liking a memoirist matters to you is intensely personal, but partly because of this, at times reading [sic] my mind wandered. Cody’s memoir showcases not only the rewards but the risks of a flamboyant (some would say egoistic) persona.

American reviewers generally raved [sic] (see the appreciative review in the New York Times Sunday Book Review), while it got a cooler reception in Europe—the Guardian’s review’s headline: “Joshua Cody’s postmodern memoir of terminal illness is too busy being clever to engage the reader’s feelings.” Guardian reviewer Robert McCrum called Cody “too cool for school” and said, “Part of the essential vanity of this publication is that Cody has been horribly overindulged, and allowed to lard his manuscript with illustrative material. [sic] is a book about sickness that should have been sent to the script doctor. It’s a mess; worse, it’s a pretentious mess. Descended from that great Victorian exhibitionist, ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody, it’s almost as if he’s genetically programmed to perform to the crowd.”

But the pervasive gut-level response of Amazon’s crowd of readers was rage.

It’s hard to pick one thing to show why. Early in the book, there’s a long scene of Cody, in new and dire diagnosis, having sex with a breast-cancer survivor. Before her breasts were removed, she’d had them cast in plaster, and this wall mount above her bed is what Cody gazes upon while they pleasure each other below, as it were, in the ruins.

So Carmilla wasn’t irritated by my admiration. On the contrary, she was flattered. In this way, her breasts still belonged to her. In this way, she was giving them, with so much else, to me. Although my hands had a problem: where should they go? The hollow of her chest. Her dear chest, and my dear hands, meeting there. And I would never tell her this, but I felt as if my hands were gripping the eyestones of a skull. And meanwhile.

But that was why she had her clitoris pierced: such a simple thing, to refocus one’s erogenous zones.

And then, at some point, which would be impossible to determine on the curve of a parabola, or on a map, we were, for the moment, finished: both satiated and done, done with the adolescent anxiety before death—she, seemingly, forever; me temporarily, vicariously, through her.

And she was finished with treatment—she’d refused that well before this point. After the loss of her breasts, enough was enough. People in white jackets had been removing parts of her body for years. And at a certain tipping point she simply said no. She’d just had a scan that clearly showed recurrence.

You’re refusing treatment? I yelled. Cleaning up. She was putting on some music.

“I know I can do it alone. It’s just the mind. More treatment will kill me. I’m treating myself: good food, sex, vodka and cigarettes. And like I was saying before—who cares? If I go this second I’ll be fine. What’s the big deal about death?”

It’s what we’d been talking about before. I’d been worried about death at the restaurant, leaving the restaurant, her hand grabbing mine, entering her apartment. Now I was again.

I don’t want to die, I said.

“Why not?”

After castigating him for wanting to survive to accomplish something, like write a book—“It’s the moment. There are no projects”—she describes the nature of her separate peace that she urges upon him:

“The superb freedom I have—and you will have—is that of a being who’s already died. And it’s so sad, that you died. I can see the sadness in your face. I know that face so well: you’re dead. But in a good way! I mean, it’s sad. But along with this sadness is this great freedom: you can do absolutely anything, there are no consequences, it’s exactly like a lucid dream, except you never wake up.”

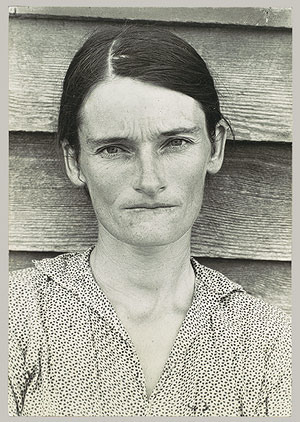

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]

[“Alabama Tenant Farmer Wife,” 1936, by Walker Evans.]As elsewhere, I admire Cody’s courage here in portraying his inner subjectivity, plus his free and fearless use of colons. But I recoiled when his paramour seems callous toward Cody’s newbie-patient fear. He hasn’t died, doesn’t want to, and in fact doesn’t. I didn’t believe her, either: her tough response struck me as a false stance. And the two of them together reminded me of any of Hemingway’s fakey, sentimental couples. Yet here I am in bed with them, or at least with Cody, for 259 pages.

Yet this is tricky. When I reread it I had to admit that hers may be a survivor’s tactic I haven’t myself earned and cannot understand. Her own attitude, she’s entitled to—not what she inflicts on him. This was surely Cody’s effort, to show her living out an active death sentence. She’s on very borrowed time; she’s late-stage, terminal. Yet I still intuited, in the way readers will, that I’d dislike her before she got sick. (And late in the memoir she shows up again and she’s fine.)

You might wonder, as I do, what this critique I’m making of a character in a memoir has to do with its author. I guess it seemed indicative to me. And it does epitomize what irks and excites me about [sic]: its “fine” style, as opposed to “plain,” as explained by Annie Dillard in her great aesthetic analysis Living by Fiction (reviewed). Part of my review:

Fine writing is energetic, though not precise, dazzling, complex and grand, an edifice that celebrates the beauty of language; it strews metaphors and adjectives about, even adverbs, and “traffics in parallel structures and repetitions.” All modernist fine writing begins in Joyce’s collages, Dillard says. “Fine writing does indeed draw attention to a work’s surface, and in that it furthers modernist aims. But at the same time it is pleasing, emotional, engaging . . . It is literary. It is always vulnerable to the charge of sacrificing accuracy, or even integrity, to the more dubious value, beauty. For these reasons it may be, in the name of purity, jettisoned.”

Plain prose, which has carried the day, stands in stark contrast. Again, from my review of Living by Fiction:

Plain writing, like Hemingway’s and Chekhov’s, is a prose “purified by its submission to the world” and represents literature’s “new morality,” says Dillard. This “courteous,” “mature” style emerged with Flaubert, who eschewed verbal dazzle. Clean, sparing in its use of adjectives and adverbs, avoiding relative clauses, fancy punctuation, and metaphor, plain prose can be as taut as lyric poetry. In an extreme form of plain writing (as in Dillard’s own The Maytrees), the simple sentences themselves “become objects which invite inspection and which flaunt their simplicity.” It risks the fatuous: “Hemingway once wrote, and discarded, the sentence ‘Paris is a nice town,’ ” Dillard observes. But plainness helps the writer to honor and to under-write real drama, respecting readers’ intelligence and permitting “scenes to be effective on their narrative virtues, not on the overwrought insistence of their author’s prose.

It’s the prose you’d write for a an audience of terminal patients—one of Dillard’s principles in The Writing Life (reviewed) and in her New York Times essay distilling the book, “Write Till You Drop”:

Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?

While struggling to make sense of my ambivalence about Cody, I happened across images of the sad but undefeated people in Walker Evans’s photographs. Having been spared yourself, a prosperous and talented person, would you caper about for them in cleverness? For those trashed and transcendent suffering souls?

Cody is a composer, and one can see this in his prose/persona, see the black-clad conductor who, standing with his back to the audience, calls forth with his pointer complex sounds from a full-throated orchestra. He’s right there in the spotlight but you won’t get to know him. At some remove, he’s causing and controlling—coolly orchestrating—the crescendo you’re hearing.

I guess what thrilled me in [sic] was seeing someone flout the plain-prose conventions that I honor. Of course my final take on Cody’s performance comes from my plugging it into my own preexisting temperament, experience, and knowledge. This is the delight and danger of experiencing anyone else’s response to art: Ah, here we have a specimen of “fine” prose . . . You know, people can educate themselves into stupidity.

So one best always check his response, as well, with his gut.

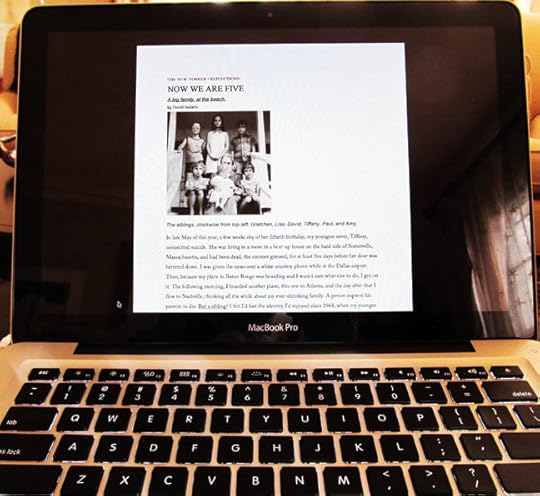

Next: an interview with Thomas Larson about his new memoir of illness.

[“Lunchroom Window, New York,” 1929, by Walker Evans.]

[“Lunchroom Window, New York,” 1929, by Walker Evans.]

January 1, 2014

A reader’s log

[In both categories.]

In 2012 I kept a reading log for the first time, and learned that I read 68 books. I thought it would be more—like 100—but the body count still impressed me. What’s weird is that I’ve just tallied my total for 2013 and it’s again 68 books. What are the odds? And is my seemingly permanent number respectable?A 2010 post by Cynthia Newberry Martin on her fine Catching Days blog puts things in perspective. Cindy and her responders are both writers and serious readers, and nobody mentioned cracking 100. My number is apparently typical, the range roughly 40 to 78. I’m not a fast reader, nor do I desire to be. In fact, a danger for a counter is reading shorter books just to boost one’s tally. Surely it’s better, for a reading writer, to have read 40 great books than to have consumed 100 solely for diversion or bragging.

As always, my 2013 list functions as a kind of diary: knowing when I read a book tends to remind me of the reading experience, as do my brief remarks. (I made an Excel spreadsheet with columns for dates, page counts, comments, etc.) Sometimes those brief judgments are coherent enough for a reader’s review on Amazon or Goodreads. My best short reviews, however, are distillations of the longer analyses I post here. I review a lot of books on this blog, which is odd because I find reviews so hard to write. Something about reviewing must appeal to me—I think it’s figuring out a book on a deeper level, really seeing how it works. Or learning why, for me at least, it doesn’t quite cohere.

A 2013 example is Rebecca Solnit’s meditation on stories, The Faraway Nearby, which I wrote a lot about here. It’s a thrilling book, and has the air of a classic. And it’s personally important to me on a couple levels. As a reader I struggled at times, however, and had to read the book again to put my finger on what caused this (yes, I counted the book twice). I distilled my long review into this notice on Goodreads:

The Faraway Nearby opens with 100 pounds of apricots, collected from her ailing mother’s tree, ripening and rotting on Solnit’s floor, a bequest and a burden as if from a fairy tale. The fruit was a story, she explains, and also “an invitation to examine the business of making and changing stories.” So Solnit tells her own story, shows how she escaped it by entering the wider world of others’ stories, and how she changed her story as she better understood her unhappy mother and their bad relationship.

A key to this unusual book is the story in The Thousand and One Nights of the sultan who, cuckholded by his queen, decides to sleep with a new virgin every night and kill her in the morning. Scheherazade volunteers to end the slaughter by telling the jealous man endless stories, distracting him with suspense so that he spares her life; in time she bears three sons, and he becomes less murderous. “Those ex-virgins who died were inside the sultan’s story,” Solnit writes. “Scheherazade, like a working-class hero, seized control of the means of production and talked her way out.”

By the same token, there are almost too many stories in The Faraway Nearby to list. Solnit has said she’s a collector of stray bits, her method bricolage. Using that clue illuminates her apparent working method: there’s been a patient melding, with verbal transitions for topic shifts. Though her method is collage-like, with disparate subjects juxtaposed, the white space one would expect is rare. This makes for more demanding reading—less warning of new topics and less time for a reader’s preparation. You’re immersed a new story before you know it. Some readers will get lost and bored and close the book.

Toward the end, she returns to her mother and to her mother’s end, to those apricots. Pared to its bones, she tells us, this book is the history of an emergency—her mother’s traumatic decline—and of the stories that kept Solnit company then. But she tells us she’ll resist the essayist’s “temptation of a neat ending,” and indeed she does. Questions flood in, a ripple effect of the book; her method, which meditates on meaning, doesn’t always presume to supply it.

This short review is the fruit of two readings of The Faraway Nearby and much writing about it here and discussing with a discerning friend who loved it without reservation. In case it’s too condensed, my lone criticism is that Solnit’s associative linking of topics with scanty expository transitions doesn’t work well for me. We’re in a particular place and time with her, and suddenly she’s at some remove, at her desk “now,” I suppose (without her telling us that), and talking about something else the foreground situation has reminded her of. Solnit’s abstracting move won’t bother some readers at all, while others will quit. I much prefer the way Virginia Woolf, one of Solnit’s influences here, grounds the reader in time and space or in the movement of her mind in A Room of One’s Own.

[A great stealth memoir.]

This makes me want to read The Faraway Nearby again, and maybe I’ll change my mind, certain in advance of what trips me. I do that of course, change my mind. I’m a fan of David Shields’s nonfiction, and last year enjoyed his Enough About You: Notes Toward the New Autobiography enough to place it briefly on my “Favorite CNF” page. Eventually I realized that for me it was completely forgettable, probably because its structure felt arbitrary, a collection of disparate pieces rather than a crafted, overarching narrative.Late last month, I devoured Shields’s The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead and consider it one of the best books I read all year. My reading-log comments: “I loved this inquiry and lament about human mortality, a stealth memoir in which we learn about the author indirectly, mostly in relation to his vibrant, dominating 97-year-old father.”

Fans of stealth memoir, here’s your huckleberry.

Next: Joshua Cody’s provocative and problematic account of cancer, [sic]: A Memoir.

December 26, 2013

Writing life, secret life

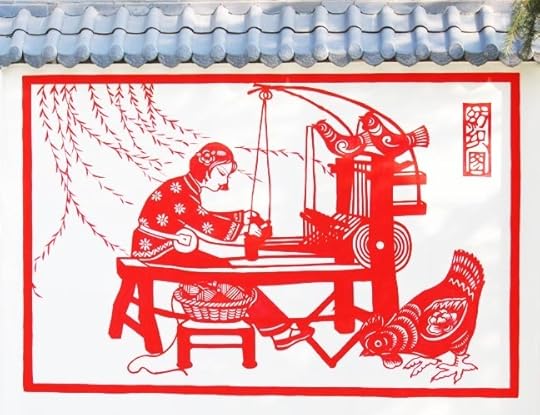

[China: Loom worker, birds, chickens.]

Jayne Anne Phillips on the writing life

From Jayne Anne Phillips’s essay “Outlaw Heart” on her web site:

[Jayne Anne Phillips.]

The writing life is a secret life, whether we admit it or not. Writers focus perpetually on the half-seen, and we live in the dim or glorious shadows of partially apprehended shapes. We could bill ourselves as perceptually challenged—given that we live two lives at once, segueing from one to the other with some distress—but we accept, long before we publish, the outlaw’s mantle. We occupy a kind of border country, focused on the details that speak to us. Ask those who marry us, or those who don’t: we’re too intensely involved, yet never quite present. Perhaps we’re difficult to live with as adults, but often we were precocious, overly-responsible children—not in what we accomplished, necessarily, but in what we remembered, in the emotional burdens we took on. . . .Writers begin as readers, and words become a means of survival. At some juncture deep within family life, the child sees in written language a way to embrace her own burden. When I was young, words themselves seemed secret because I read them in my mind and no one else could hear. Knowledge was often secret; the most interesting things were repeated in low tones.

Rumpus guy’s metaphors

From The Rumpus editor Stephen Elliott’s recent email about a dinner party he helped host for author Nick Flynn:

Nick arrived last to his own party. He’s here for the Lou Reed celebration tonight at the Apollo and I’m his date. I said this was a prime example of bromance, and then I pointed out to people, maybe more than once, that the OED credits me with the term “bromance.” Though I’ve never looked inside the OED. Apparently I was the first to put the term in writing in 2003 or something, referring to Josh Bearman when we were covering the presidential election which was interesting when Howard Dean was running on health care and tragic when we all ended up solidifying like chillled bacon fat behind John Kerry who had voted to authorize the war in Iraq, the thing we were all most against. I mean, they just squandered our country.

Which is why when it was over I was out there in the Atlantic, floating off the shore of Hollywood, Florida, struck by waves like calm fists, when I was overtaken by nausea. Brent Hoff was on the beach contemplating the birds. The sun was smokey orange and low. Florida is like an enormous apartment with seven foot ceilings. The sky is so close to the earth it makes people violent. It makes you want to live in a swamp, or St. Petersburg. I was taken to the judge’s house and I lay recuperating in their attic with four years to kill.

Anyway, now I have very high ceilings. I would say the ceilings in my apartment are fourteen feet. Plus, we were all sitting on the floor so the ceiling was even further away. And we talked about Snowden, and the holidays, and Almost Human, and Friday Night Lights, and Vancouver, and food, and relationships.

It’s the second paragraph I really adore, what with Elliott’s similies of waves “like calm fists,” Florida “like an enormous apartment with seven foot ceilings,” the line about the low sky, and the crack about St. Petersburg. Plus its lack of connective tissue and plainly surrealistic quality—he feels nauseous and suddenly is in a judge’s house’s attic “with four years to kill,” such wonderful mixes of details and exaggeration. And can the ceilings in his apartment—where? New York? or was he just traveling?—really be 14 feet? That’s airy, even for the South.

Ah, well. Don’t try this at home, kids. But I’d like to. Go for it.

December 19, 2013

Tolstoy’s paragraphs of the week

![[Leo Tolstoy.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1387792103i/7672122.jpg)

[Leo Tolstoy.]

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

All was confusion in the Oblonskys’ house. The wife had found out that the husband was having an affair with their former French governess, and had announced to the husband that she could not live in the same house with him. This situation had continued for three days now, and was painfully felt by the couple themselves, as well as by all members of the family and household. They felt that there was no sense in their living together and that people who meet accidentally at any inn have more connection with each other than they, the members of the family and household of the Oblonskys. The wife would not leave her rooms, the husband was away for the third day. The children were running all over the house as if lost; the English governess quarreled with the housekeeper and wrote a note to a friend, asking her to find her a new place; the cook had already left the premises the day before, at dinner-time; the kitchen-maid and coachman had given notice.

—Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

You have to wonder about when, in his writing process, Tolstoy came up with his killer first line, seemingly one of the truest and certainly one of the most famous in all of literature. Did it always launch his 800-page novel, published when Tolstoy was 49, or did it arise during composition and end up placed there? (Scholars?) In any case, does it not refute the maddening “kill your darlings” commandment? It places an expository moralizing signpost atop a great paragraph that could open the book. There’s every nasty neat reason to cut it—and one not to, bound up in the category called genius.

I’m struck too by how Tolstoy starts in long-distance mode, referring to “the wife” and “the husband,” but in the third paragraph he’s moving the camera closer; soon we’re right up in their nostrils. I’ve always loved Tolstoy’s simple but elegant sentences, on full display here.

But of course I’m reading him in translation, in the new edition edited by the hottest Russian-literature translating team, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. If you poke around on the web and read Amazon reviews, you’ll see even these lauded midwives dissed—someone swearing an older translation is better. Basically I picked Pevear and Volokhonsky based on Anna Karenina’s opening line: I liked their version’s phrasing and punctuation, as well as the opening sentence of the second paragraph; you can read several using Amazon’s “Look Inside” feature. I might have read the Constance Garnett version with an opening line almost identical—“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”—though Garnett’s second sentence, truer to Tolstoy for all I know, feels slightly less felicitous: “Everything was in confusion in the Oblonskys’ house.”

I imagine that in any version, which must be an interpretation and approximation of his Russian style, Tolstoy’s graciousness and wisdom survive.

Recently I pulled from my bookcase an old paperback, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Russian Literature, and it launched my Russian writers kick. I realized I’d probably meant to read Chekhov, Dostoevski, Gogol, Gorki, Tolstoy, and Turgenev with Nabokov as my guide when I bought the book over 30 years ago, in 1981. But I hadn’t. So I’ve started. But not slavishly—recently I gave up on Gogol’s Dead Souls—and may lack the endurance for completing even the artistically exciting Anna Karenina.

Employing Nabokov as my teacher embodies several paradoxes. For one, his analyses are full of very detailed plot descriptions, so must be read afterward. For another, while I honor his literary artistry, I dislike Nabokov’s haughty aesthete persona. So my experiment is fraught. Yet I find my distaste for Nabokov’s persona frees me from awe and leaves room for disagreement with the master. For instance, he disliked and dismissed Fyodor Dostoevsky, and while that Russian joins Nikolay Gogol in defeating me as a reader so far, Nabokov’s estimation of one of the world’s acknowledged great novelists seems petty and willfully obtuse.

This winter I’m trying to channel my inner 14-year-old and lose myself in Anna Karenina. That’s harder with age, but it has been gratifying to feel myself excited by Tolstoy’s sentences and his magisterial yet compassionate vision of his characters. Partly, I admit, I want to learn from and argue with cold-fish Nabokov about that warm mammal Tolstoy.

December 12, 2013

Perils of persona

["Labor of Love Thrift Store," The Plains, Ohio.]

Ten Notions About Persona in Nonfiction

1. “Truth is subjectivity.”—Søren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript.

Every human experience is first passed through the scrim of emotion. A vital tool in our kit. Consider the jury system.

Art is made from emotion, about emotion, elicits emotion.

But for making art from experience, like Kierkegaard did, craft is required. Techniques that tell the reader a wiser intelligence is at work to wrest something shapely from the quotidian, from chaos, from mere moods. Part of this craft of presentation is the creation of a palatable, truth-telling persona. Witty or somber. Earnest or flip. Glimpsed in the margins, or all over everything like white on rice.

This is an approved practice. Rock solid. Take it to the bank.

2. “A sensibility we construct into some kind of figure is what keeps the reader going.”—former Atlantic editor Richard Todd, to a workshop I attended.

This emphasizes Persona 1: the person telling the story, someone come to testify or entertain. Both, really, always.

Often as well there’s Persona 2: the former self in the experience being depicted or discussed.

Behind these, there’s the writer creating each persona. Is that Persona 3? Or is that “you”?

3. Maybe it’s this simple:

You take something that is important to you, something you have brooded about. You try to see it as clearly as you can, and to fix it in a transferable equivalent. All you want in the finished print is the clean statement of the lense, which is yourself, on the subject that has been absorbing your attention.—Wallace Stegner, Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs

4. Maybe it’s not:

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

—T.S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Call that face what Freud called the ego: a mediation between the censoring parental superego and the unruly id.

How is preparing a persona in prose any different? Do writers, like children, perform for the superego—that is, for society, a stand-in for parents?

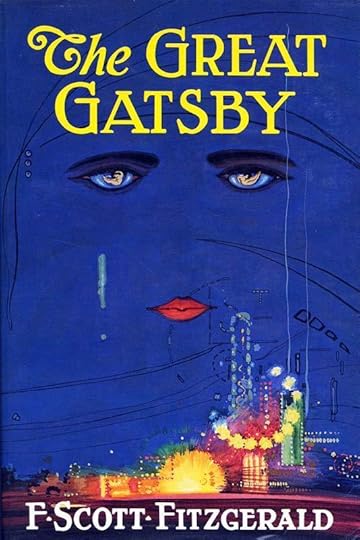

5. “Personality is a series of successful gestures.”—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby.

[Dawkins: Classic British twit.]

Buddhists view the fiction of a concrete self as a delusion; we’re more like onions, with various layers, no core. For convenience we might call the conceit of a self the ego.A similar notion of the unmoored self was expressed by the existentialists; they believed there’s no essence or blueprint but only a self constantly created and re-created through action. Supposedly unlike our dog, and certainly unlike a chair, humans lack a blueprint, save what we draw in action. We’re consciously choosing what to do in each moment and thereby can define a new self—but also have the burden to do so.

Despite or because of its grandiose romanticism, existentialism is moribund.

The more recent theories of some evolutionary psychologists are much darker, implying that all significant actions are the product of genes, our behaviors forged during centuries of evolution. We can’t help our bad side any more than our dog can his. Change essentially is impossible, a pathetic hope for an animal (admittedly complex) that evolution has programmed, as thoroughly as any robot, to be utterly selfish.

[Shakespeare: immortal British genius.]

Have we truly become such dwarves since Shakespeare’s grand vision of us? People may be gluttons for punishment, but surely only superficially accept this bullshit, despite the cachet of that classic British twit Richard Dawkins. Evolution itself is of course as real as a heart attack. As always, though, it’s all in how you interpret, which depends on what you bring to the table. Watch Dawkins on TV and you’ll find it hard to resist wanting to give him noogies, a wedgie, an Indian burn, a Wet Willie. This is the dork who tells us how dark and corrupt humans are? But then, growing up he must’ve drawn bullies like garbage draws flies.Buddhism presumes far less than most belief systems, certainly less than than atheistic evolutionary psychology claims, and at least offers good tools.

6. “The first art work in an artist is the shaping of his own personality.”—Norman Mailer.

Dorothea Brande’s slim 1934 classic Becoming a Writer says conviction is the underpinning of all imaginative writing. Writers therefore must know who they are and what they believe about most of life’s major issues. Like their notion of God, she says. In his foreword to the 1980 paperback reissue of Brande’s book, John Gardner says the root problems of the writer are personality problems, “in other words, are problems of confidence, self-respect, freedom . . . Her whole focus, and a very valuable focus indeed, is on the writer’s mind and heart.’’

7. We touch, rub shoulders as we go, but we move forward each alone into eternity encased in the narrow cell of self.

Seeing survivors’ pain, Jesus wept.

Kierkegaard, whose concerns and cure were likewise spiritual, spoke to a deeper need than self-discovery, that of rebirth:

If a man cannot forget, he will never amount to much.

If you forget, can you draft a new persona for yourself?

I’ve tried—who hasn’t? As they say in southern Ohio, “It weren’t easy.”

8. “Wanting to be noticed is wanting to be loved.”—Richard Poirier, The Performing Self: Compositions and Decompositions in the Languages of Contemporary Life.

Is the artist only someone who wants to be noticed more? Loved more? Is this quality, offensive in everyday life if too obvious, justified by content and rendered palatable by craft?

Maybe, like our stories, we are constructs—complex interactions between genetics and environment—but with something mysterious in us as well. Something in the depths that links humans across time. Carl Jung called it the collective unconscious. Trying to express this, or tap its power, the constructed self constructs a self in which to present self and story.

9. The usual image of the writer is one who has stuffed herself with much Art and much Life. This constructed fullness gives the writer the right and the material to spin her tales, to hold forth.

Gertrude Stein, in her strange essay “What are Master-pieces and Why Are There So Few of Them,” seems to argue, to the contrary, that the artist must draw from what is original and unbuilt within. “After all,” she writes, “any woman in any village or men either if you like or even children know as much of human psychology as any writer that ever lived.” The artistic self is not the piling up of more and more identity but a paring. She seems to argue for expression of an irreducible core that is completely original:

The thing one gradually comes to find out is that one has no identity that is when one is in the act of doing anything. Identity is recognition, you know who you are because you and others remember anything about yourself but essentially you are not that when you are doing anything. I am I because my little dog knows me but, creatively speaking the little dog knowing that you are you and your recognising that he knows, that is what destroys creation. . . .

10. W.B. Yeats explaining his creative process:

I think that all happiness depends on the energy to assume the mask of some other self; that all joyous or creative life is a re-birth as something not oneself, something which has no memory and is created in a moment and perpetually renewed.

So you, whoever you may be, are—or might be—a vessel of creation.

December 4, 2013

A true farmer & a good writer

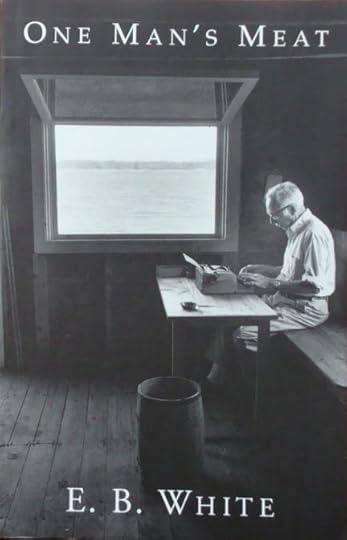

![[White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361085i/7347570._SX540_.jpg) [White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]

[White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]E. B. White captured farming’s mythic pull and practical difficulty.

There is no doubt about it, the basic satisfaction in farming is manure, which always suggests that life can be cyclical and chemically perfect and aromatic and continuous. —E.B. White, One Man’s Meat

![[“Andy” White and friend.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361085i/7347571.jpg) [“Andy” White and friend.]

[“Andy” White and friend.]During the years I worked on Shepherd: A Memoir, I learned that literary folk interested in country matters wanted to know my agrarian pedigree was pure. Maybe that I had one. Those early draft-readers wanted assurance that I’d read Wendell Berry and Wes Jackson. At first this irked me. Sure, I knew their work. Their writings on agriculture and American society have informed my thinking from early adulthood; Berry’s Jayber Crow is one of my all-time favorite novels.

But why was it crucial that I let readers of my story know that?

I wondered if they knew about Maine organic proponent Eliot Coleman; about Australian permaculture pioneer Bill Mollison; about Zimbabwe-born Allan Savory, whose Holistic Resource Management is the most profound treatise on conservation and human decision-making I’ve ever read.

As it was, Shepherd explored my boyhood hero worship of Ohio farm memoirist Louis Bromfield; and my being influenced as a practitioner by Bromfield’s more pragmatic eco-farming successor, Joel Salatin; and my discovery of Charles Allen Smart’s classic memoir, RFD, set in the same region where I ended up struggling to become a farmer. Plus my day job was in publishing, so there was plenty more about books in my memoir.

I finally decided that concerns about my literary lineage were a kind of backhanded praise. As if those readers were saying, “This book is by a writer, not just some farmer.” So I dutifully mentioned Berry and Jackson.

Now it strikes me as odd that nobody mentioned E.B. White (1899–1985).

It is not often that someone comes along who is a true farmer and a good writer. White was both.

///

As a writing man, or secretary, I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost. But it is not easy to communicate anything of this nature.—E.B. White, “The Ring of Time”

I reread One Man’s Meat years ago, about the time I started my own book. I saw that White, a genuine man of letters, was farming on a significant scale for the times. His place was no gentleman’s hobby farm. Or not merely that. Thus he’d earned genuine insights into the mythic pull and the practical difficulty of farming.

I reread One Man’s Meat years ago, about the time I started my own book. I saw that White, a genuine man of letters, was farming on a significant scale for the times. His place was no gentleman’s hobby farm. Or not merely that. Thus he’d earned genuine insights into the mythic pull and the practical difficulty of farming.

It wasn’t until recently, when I read White’s newest biography, Michael Sims’s The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E.B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic, that I learned he had a full-time hired man. I didn’t have sense enough to get a helper myself until I’d gotten seriously injured in a farming accident. White had grown up with servants, in a Victorian manse near Long Island Sound, and he and his wife kept several folks on their payroll. She edited and he wrote, both stalwarts and stars for decades at the New Yorker, and for years they commuted between their Maine coast farm and Manhattan.

Sims’s biography is great on the writer’s early years. White grew up in an orderly, affluent world, with two loving parents. His father ran a company that made musical instruments, and adored his youngest child, Elwyn Brooks White: “Oh, the joy, the joy of my little boy; we have lots of good times together.” As for little Elwyn, he was both artistic and outdoorsy. Also: anxious, terrified, sickly, and melancholy. The kid was a hot mess. Having been a similar child myself, I now identify with him even more.

White made good use of his thin-skinned temperament, which fuels his writing and courses in an elegiac vein through it. Only a sensitive soul could have crafted this lovely line, from One Man’s Meat: “I am always humbled by the infinite ingenuity of the Lord, who can make a red barn cast a blue shadow.” (While working at Ohio University Press/Swallow Press, I titled one of our P.L. Gaus Amish mysteries Cast a Blue Shadow.) It’s striking how much of White’s work, including his famous essay “Once More to the Lake,” is about death. This preoccupation was balanced by his love of the city’s busy workaday world and of nature close at hand. Many of us share his adoration for birds and dogs. A few of us see how genuinely he appreciated humble livestock.

And White is the only prominent farmy writer I’ve read who mentions something else we sadly share: allergies. Hay fever is a particularly cruel and ironic affliction for a farmer. White’s description in One Man’s Meat of his periodic malaise could be my own in ragweed season. Writing so personally has kept White’s work fresh, whereas Bromfield’s farm adventures, still hugely enjoyable, have taken on a sepia cast.

I wish during my memoir-writing I’d reread White’s “Death of a Pig,” a fine essay that appeared after those collected in One Man’s Meat. Here’s its famous opening paragraph:

I spent several days and nights in mid-September with an ailing pig and I feel driven to account for this stretch of time, more particularly since the pig died at last, and I lived, and things might easily have gone the other way round and none left to do the accounting. Even now, so close to the event, I cannot recall the hours sharply and am not ready to say whether death came on the third night or the fourth night. This uncertainty afflicts me with a sense of personal deterioration; if I were in decent health I would know how many nights I had sat up with a pig.

“Death of a Pig” bares a timeless dilemma of animal husbandry: tending and heroically ministering to animals that one day you’re going to betray. That jarring shift in roles from nurturer to killer shocked and troubled me as a farmer—I write about it in Shepherd. So here’s a case where my invoking an agrarian-writer forefather would have been highly appropriate. Dang.

Beyond its compelling content, there are writing lessons in “Death of a Pig.” There’s the humor, which takes the curse off this story of death, makes it more entertaining than harrowing. And the humor signals the perspective of a wiser narrator, a survivor who is invoked and mocked at the same time. And who fearlessly gives away the game at the start—the pig died—because he’s come not just to tell the tale but to inform us of the incident’s deeper meaning. White is witty without seeming too pleased with himself; his sentences are strong without feeling ostentatious.

As in his other work, White’s artistry—in the form of persona, style, and narrative structure—shields “Death of a Pig” from the implicit “Why should I read your story?” challenge that haunts personal nonfiction. His material is always solid, his rhythms pleasing, but it’s his wry view of himself and his situations that may be his most effective move in making art from experience.

///

After all, what’s a life, anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die.— Charlotte’s Web

I owe E. B. White a personal debt, too, though that story didn’t make my book either. One day when we were living on our farm in southeastern Ohio, my son, then in fourth grade, came home upset. Fighting back tears, he said, “I’m going to die.” He meant one day, which was worse to deal with, for him and for me, than some passing irritation. Years later, I can’t forget that moment in our family room. Sunlight fills the windows, the green world burgeons outside, and we stand looking at each other. His precocious despair robbed me of easy words. The moment lasted forever—in my mind’s eye we’re paused there still—but my response arrived in an instant.

What I did was turn from his swollen face and pop in a videotape. It was the animated Charlotte’s Web, a Hanna-Barbera musical released in 1973, the year of my graduation from high school, way down in Florida, where I’d grown up grieving my father’s loss of our family farm. My grabbing the movie seemed instinctive, and later it puzzled me—I hadn’t yet read the book and had watched the movie without conscious assessment. Now I can see why I did it. Wilbur barely escapes his intended destiny of becoming bacon. And his aging spider friend Charlotte does expire, though her story continues with her renewal in the form of baby spiders. Rebirth is her final gift as Wilbur gains three new friends from among her 514 offspring.

Friendship is the novel’s suggestion for coping with the death part of the life cycle. It does make a world of sense, if you need to justify fellowship, because people surely do need people. As Woody Allen puts it in his play Don’t Drink the Water, “Life is an adventure you go through with someone you care about.” Charlotte’s Web adds, And if you’re able, fill the world with new allies—procreate. That’s what I’d done.

But my and Charlotte’s reproductive solution wasn’t a relevant strategy for my nine-year-old son. So showing him the video now seems lame—why not question him, hug him, reveal something? Yet in the midst of my comparatively complacent middle-aged life, standing before him blank and panicky, I seized upon Charlotte’s Web.

I’d have a better answer today, I think. But maybe not, in the moment.

White’s magical story was relevant. So I thank him for helping me out of a parental jam. But then E.B. White, as an artist, was so nicely balanced between that hypersensitive life-loving pig and that tough-minded creative spider.

[White once gave an interesting interview to The Paris Review, which I excerpted here. The New York Times ran his obituary.]

November 27, 2013

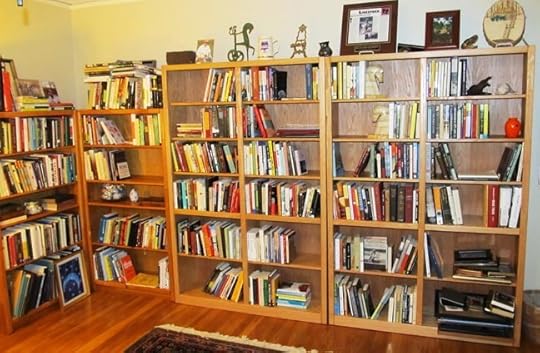

The promise of new bookcases

[Alphabetized novels and memoirs form the heart of the new Working Library.]

What’s on our shelves? Only matters of infinite hope.

Most of us when we go into other people’s homes will surreptitiously check out the bookshelves and the music collections, forming our impressions of the owners’ character from what they read or listen to. Most of us know that others do this and so the books in the public spaces will be arranged to particular effect, different from the working books.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Bishop’s book: night reading.]

You told your mate that for every new physical book you bought, two would leave the house—carted to the used bookstore, or to the library, or even secreted in the trash. Yet this has not quite happened. The jig was up when she caught you culling her old books more heavily than you pared your own.In the basement are six full bookcases, pine painted white, each four feet tall and three feet wide. Eighteen feet of books. Your how-to library and oddments, many small thin paperback novels and plays from the spouse’s days as an English teacher. Some children’s books. This library could use another hard sorting—or complete dispersal. But all those gardening and farming and dog and chicken and sheep and cattle books are old friends. Some were your father’s. They reflect long-gone prior lifetimes. Youth itself.

Upstairs, on the main floor of this house, built in 1939, just off the foyer there’s a tidy room with real built-in bookcases. The house’s own small but dignified library: dark, solid walnut shelves. Now a sitting room-TV room-library. The show library. Here are the big hardback novels. And your father’s leather-bound Britannica Great Books—54 unread volumes. Also a complete set, as resonant as a train whistle from your childhood, of the Encyclopedia Britannica. And The Riverside Shakespeare. Books as decoration, as aspiration, as comforting totems.

Like the three oversized paperback iterations of Stewart Brand’s The Whole Earth Catalog—1970s pre-Internet subject-surfing fodder. The iconic black-covered original edition is crumbling from heavy use, high-acid newsprint, and cheap binding.

•

The door to the library was in the corner and the bookcases jutted out into the room so that nobody coming in knew at first whether you were there or not. You felt twice removed from the outside world, secure to dream.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Nabokov’s lectures: old buddy.]

On the second floor, there’s your real library, in a spare bedroom. What you think of as your Working Library. This repository has required the recent acquisition of two huge new bookcases. Oak to match two stout butcher-block cases—each five feet tall and thirty inches wide—your mate gave you years ago. New bookcases were necessary because the small ones were full and hopelessly jumbled. There were stacks of books on the floor around them. Sometimes it was easier to buy a new book suddenly needed for teaching than it was to find the copy you were sure you had. Somewhere.Now the two little bookcases, to the left, hold your books on writing, your essay and poetry collections, your religion, spirituality, and self-help volumes. Some of these summon a younger you: Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature; John Calhoun Merrill’s Existential Journalism; your father’s copy of Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer; his own book, Success Without Soil. You’ve lugged them around since before college and shortly after.

Atop of one of the original bookcases is a huge and growing pile of to-be-read. You promise yourself to peruse these before ordering new books.

And so: center-right on the wall, there they are. The two new capacious Arthur W. Brown bookcases. Each six feet tall and four feet wide; in face-frame style to match their shorter companions. They’re alphabetized. Memoirs and novels. Already read only. Literature only. Well, with a little history and evolutionary psychology on the far right.

The oak is a shade lighter than the old five-footers’ mellow amber. But it will darken imperceptibly as they age.

•

I’ve heard that most academics—most professionals—read in chunks of thirty pages or less. The average length of a professional article. So even when you have the time, on sabbatical or on holiday, after your thirty pages you feel you should be turning to something else.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Modernist novel: morning book.]

Now you’re piling up a stack on your dresser for winter break reading. For December and January. Actually two stacks. To the left, books for Spring classes. To the right, books that have lingered long in the to-be-read pile. Like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Which you always think of after you make it to Florida, hear the waves breaking outside your sister’s beach condo, and wish you’d brought.A student expresses amazement that you buy physical books, or keep them. Yet, though no real foe of e-books, you do. You find the presence of physical books aesthetically satisfying and emotionally comforting. Objects of such pleasure. One for each mood. And at least two always going: in a nod to age, an easy night book and a harder one for morning.

Books, to paraphrase your ex-friend Nick Carraway, are matters of infinite hope. Yet, like any object of art, like any perfected medium, they cry out for placement. A person’s home, you posit, must have not just pictures on the wall but at least one serviceable bookcase. Which always has its own story.

Doesn’t yours?

November 20, 2013

Newest film rocks ‘Gatsby’

[Baz Luhrmann’s film is as gorgeous, specific, and unmoored as the novel.]

Great American Novel survives another film—will it survive itself?

On Sunday morning while church bells rang in the villages alongshore, the world and its mistress returned to Gatsby’s house and twinkled hilariously on his lawn.

—the opening to Chapter Four of The Great Gatsby

As famous as are The Great Gatsby’s gorgeous opening and ending passages, the above line shows as well as anything the1925 novel’s elusive poetic magic. Gardens are blue, cocktail music is yellow, and trays of silver drinks float in the dusk. In prose at once specific and grandly metaphoric, The Great Gatsby unspools a plot utterly American in its larceny and its romance: the story of a rags-to-riches-shady-but-essentially-good-social-climbing outlaw whose self-invention and male yearning end in murder.

Since I’ve loved Gatsby for much of my life, I resisted seeing until recently the latest movie based upon it. I doubted whether Leonardo DiCaprio could get off Gatsby’s “old sport” tic without sounding ridiculous. “Old sport” was the nail in the coffin of Robert Redford’s inert performance in the 1974 film flop.

Now comes Baz Luhrmann with Leo as leading man. The Aussie’s effort, Hip-Hop infused and with splashy 3-D option, is “pretty much a disaster,” rules David Denby of the New Yorker. “Gatsby’s big parties are a seething mass of flesh, feathers, dropped waists, cloche hats, swinging pearls, flying tuxedos, fireworks, and breaking glass,” Denby writes. “Luhrmann’s vulgarity is designed to win over the young audience, and it suggests that he’s less a filmmaker than a music-video director with endless resources and a stunning absence of taste.”

To me, Luhrmann’s Gatsby and its centerpiece party are properly riotous—he brings brassily to life the wild gaiety to which the novel alludes. In the novel, we’re told that Gatsby is about servicing a “vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty” and that his guests conduct themselves “according to the rules of behavior associated with an amusement park.” So Luhrmann’s attempt to render this is vulgar? And though F. Scott Fitzgerald felt no need to point out the obvious, it helps that Luhrmann does, in a deft voice-over: the action occurs in 1922, with Prohibition in full swing and foaming with paradoxes: alcohol was more abundant, cheaper, and more alluring than it had ever been.

Luhrmann appears to have a genuine love and understanding for the slender, jaunty novel and its hyper-literary quality. Toby McGuire is well cast as Nick Carraway, who in the text as well is trying to make writerly sense of Gatsby and his fate. Nick’s wan love interest, Jordan Baker, played by a strapping, striking actress, does not fit my image of her, but what the heck. Luhrmann’s Daisy is fine. And DiCaprio not only gets off multiple credible “old sports,” he breathes to life Gatsby, who becomes far more real than he is in the novel; not just rich and driven, he’s also insecure and charismatic. This is how some movies bigfoot their prose sources: they make textual fancies palpably real.

In short, Luhrmann’s movie is as gorgeous, specific, and unmoored as the novel.

[Luhrmann and DiCaprio at Cannes.]

Yet this begs the question of whether Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, which still sells 500,000 copies a year and is widely used in schools, will endure as the iconic Great American Novel. One of its portrayals seems anti-Semitic. And though Fitzgerald and his stand-in Carraway mock Tom Buchanan for his racism, later Carraway makes a comment that’s jarringly racist. Maybe this is more verisimilitude, reflecting the book’s times or Carraway—not fatuous like Buchanan but still a man of his times. Yet now, at the least, these ugly notes date the book; literature in America isn’t assumed any longer to be the province of male WASPs. Interestingly, Luhrmann silently addresses both flaws, in the later case by the inspired infusion of black musicians.This aspect of the novel pains me on this, my latest rereading. I think it’s having taught and identified with students of diverse ethnicities and sexual orientations. Suddenly you see the world through their eyes, and even pop songs can seem a phalanx of cruelly narrow heterosexual orthodoxy. As narrator, Carraway is someone we’re meant to identify with, and I picture a black kid getting to that line, where Carraway calls two black men “bucks.” As much as I’ve loved it, I wouldn’t want to teach Gatsby.

Previously I wrote about Gatsby’s memoiristic structure.

November 14, 2013

New reading, writing tools

[My iGoogle page: clean look, dozens of feeds.]

On Friday, November 1, I arise and open my computer. Sure to Google’s months of warnings, iGoogle is gone. I’m flying blind.For years, dozens of RSS feeds filled my iGoogle page—it’s the way I kept up with blogs and got news feeds. In an instant I could scan headlines, note a blogger’s new post, feel connected with the hive. Google wants its iGoogle fans to use another of its services. There’s no way.

For starters, I’m miffed. iGoogle was so perfect a reader and home page for me. Not that I ever paid for it, so how much can I fairly protest? And yet, by the end, I would have paid. (For the record.) But paying for what I’d grown to love wasn’t an option—you live by the Internet’s freebies and you die by them.

[igHome imported my feeds but feels clunky.]

There are all kinds of new readers. Most make the same mistake, emphasizing graphics. The beauty of iGoogle was its clarity and simplicity. Supposedly you can make Netvibes or Feedly or whatever look like iGoogle. But I fail.Instead, I select igHome, which most resembles iGoogle. Superficially. Since it’s kind of clunky and uncool, however—like its very name—I feel even more Internet inept. And certain I’ve made a mistake. Surely igHome is doomed.

Trying to adjust to my new window on the web, it feels like my glasses prescription is from a decade ago. Everything’s a bit out of focus and less graspable. But such a problem everyone should have in this world! Complaining about igHome makes me feel worse about myself than does having picked it.

My new Apple MacBook Pro computer

[New Apple from China in the box.]

The afternoon of the death of iGoogle, I open my new 13-inch MacBook laptop. Which had arrived from China on Halloween.I’m a packrat, and have filled up my poor current MacBook in 4.5 years of steady use and obsessive collection of material. All my students’ essays from every class, plus stuff from each class. Hundreds of other essays I’ve downloaded. Six versions of my book—with dozens of chapter versions. Hundreds of blog posts. And the real memory hog: photographs. I recently upgraded my RAM from 2 gigabytes to the maximum it would take, 4. But Apple’s spinning pinwheel of death barely was staved off.

So I needed capacity. I stuck with the 13-inch MacBook Pro laptop, not the fancy Retina screen model but their workhorse: the maximum RAM, 8 gigabytes, and the biggest hard drive storage offered in the line: 1 terabyte. I have no idea how much that is, but it’s a hell of a lot.

I can guarantee you something about computer technology. Within days of my buying a new computer, Apple will announce a huge new advance of some kind. Longer battery life. Better graphics. Enhanced operating system. Humongous storage capacity. RAM so fast it will make your nose bleed.

Knowing this, before I ordered I asked two experts—my twentysomething daughter who works in IT for a university, and my university’s Apple expert—if there was anything on the horizon. Nope, they said. All quiet at Apple. Then I called Apple and asked a rep. No, he said, nothing looming. So I ordered.

Two days later, Apple offered hugely increased RAM and hard drive storage in its high-resolution Retina screen laptops. I could’ve doubled my RAM yet again, to 16 gigabytes. And viewed my virtual world in hi def. The storage in the Retina model still isn’t quite as much as I got, but probably enough, what with cloud storage trends. RAM probably makes more difference in user experience. I don’t actually feel bad, though—more like excited about my strange power to spur Apple’s release of new products.

But then, there’s the issue of where my computer originated. Internet tracking records show it was assembled, per my online order, in Shenzhen, China. With China’s human rights, labor, and pollution issues, how good can a guy feel about his Chinese-American laptop? Supposedly India is kicking China’s butt as a cheap assembler, though, so maybe competition will eventually work its vaunted magic.

New Microsoft Word – including Focus View

[My new MacBook's Word software shown in Focus View. Looks good for writers.]

For years I wrote in and loved WordPerfect. I kept using it on my old desktop Apple computer even when Corel quit supporting it. But that computer died. So when I migrated to a laptop at last, I had a fling with Apple’s word-processing program, Pages. Which was fine, but not portable enough—not with my students using mostly Word.

I started liking Apple products and disliking its foe Microsoft back in 1994, when I entered a sophisticated Apple environment at Indiana University Press. My favorite quip about Microsoft is still that it’s neither small nor soft. It’s a big and ruthless company. I have to admit now that that describes Apple as well.

Yet I favor Apple’s products and have accepted Word. It has killed a legion of basic, elegant writing programs. But though Microsoft has larded it up with far more features than anyone uses, Word has won.

Having to leave my 2008 Word version, however, was my biggest worry in getting a new computer. A student who has the 2013 model for windows says it’s a mess. Thankfully, the version for Apple always lags behind a few years. I haven’t migrated to my new laptop yet, but have launched its Word 2011 software and it seems fine.

In fact, this Word has a new “Focus View,” which blacks out everything on your screen except your document. I’m looking forward to trying that feature.

November 8, 2013

Last edit, Amazon page & blurb

[That big stack of paper beside Belle, my editing buddy, is my typeset memoir.]

The past couple of weeks I’ve worked my way through page proofs for my book. My last crack at perfecting Shepherd: A Memoir. As I’d leave classes for the day, walking across the campus’s lovely old green I’d think, I can’t keel over dead. Not yet. Not under this ginkgo tree. Not until I submit my edits!

So life went on. I nursed Kathy through emergency dental surgery. Walked the dog. Went to committee meetings. Ordered a new computer. Read lots of student essays. One was heartbreaking. And a brave work of art. It was rewarding to see some of my teaching come back, or at least see what grew in a space I created, but celebrating it was fraught. I told its author what Augusten Burroughs recently told me, in This is How: Surviving What You Think You Can’t (which recently I too briefly reviewed):

As it happens, we human beings are able to live just fine with many holes of many sizes and shapes.

And pleasure, love, compassion, fulfillment—these things do not leak out of holes of any size.

So we can be filled with holes and loss and wide expanses of unhealed geography—and we can also be excited by life and in love and content at the exact same moment.

Though there will always be days, like the weather, when the loss returns fresh and full and we will reside within it once again, for a while.

Loss creates a greater overall surface area within a person. You expand as a result of it.

That’s me, I’d say. Expanded all over the place. And Augusten is right, love and loss are a pair. Reading my page proofs, typeset in elegant Adobe Garamond Pro, was to sit side-by-side with love and loss. There on the couch, with the dog. (She’s a strange, furtive thing, and I love her too.)

I found only one typo, a truncated word. And too many instances where I repeated the same word several times within a few sentences. Set in type, words jumped out in a new way. Sentences I’d recast in one mood, years ago, I felt the urgent need to alter. Or even to change a few back to what I recalled doing in the first place. Not for the first time, I thought, I am not smart enough to do this work.

Then someone called my attention to the fact that already my book, not due till May 1, has an Amazon page. And then I received this amazing endorsement from Lee Martin, a Pulitzer finalist in fiction, a great memoirist, and one of my writing heroes:

Shepherd is the story of one man’s dream of returning to the land, but Richard Gilbert’s glorious memoir is more than that. It’s a universal story of families, the ones we try to redeem and the ones we strive to create and maintain. Gilbert writes with a keen eye and a quiet grace. His portrait of the natural world takes us into the interior landscape of its very human, very likeable guide—an honorable, courageous man. I’m so very happy to have had the chance to meet him in these pages.

—Lee Martin, author of Such a Life and From Our House

As Dad used to say, That’s better than a sharp stick in the eye!

[Editing is hard work.]

Oh, that’s another thing. How I missed Dad and Mom as I worked this last time on Shepherd. The book is so much about them, really, as Lee saw. Dad died a few years after he couldn’t physically operate his nursery anymore. The book he wrote before my birth, Success Without Soil, as I’ve noted, goes on and on. It has its own listing on Amazon. Some of his oaks, raised from acorns he collected, must be a hundred feet tall.Writers and their books, farmers and their crops. Gotta see how they turn out. That next bunch of calves, foals, lambs. That extra three-bushels an acre corn. That perfect next composition. You see your work, you see your failure, you love the thing itself.

I could keel over now. My war-hero uncle used to say, when aged, “I’m under consideration.” Aren’t we all? But though the winter comes, ushered on a low November sky, my publisher is sending me bound galleys, made from uncorrected proofs, and it would be nice to hold them.

And in spring, the book.