A true farmer & a good writer

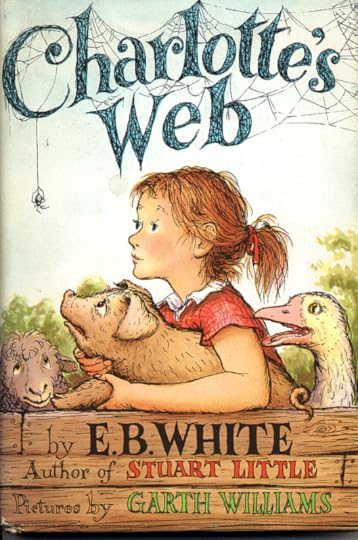

![[White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361085i/7347570._SX540_.jpg) [White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]

[White wrote a lot about death, but he also celebrated the world’s beauty.]E. B. White captured farming’s mythic pull and practical difficulty.

There is no doubt about it, the basic satisfaction in farming is manure, which always suggests that life can be cyclical and chemically perfect and aromatic and continuous. —E.B. White, One Man’s Meat

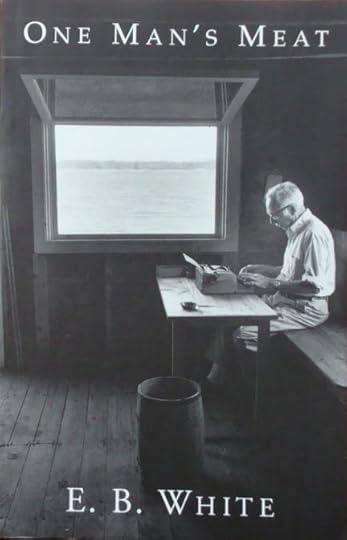

![[“Andy” White and friend.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1386361085i/7347571.jpg) [“Andy” White and friend.]

[“Andy” White and friend.]During the years I worked on Shepherd: A Memoir, I learned that literary folk interested in country matters wanted to know my agrarian pedigree was pure. Maybe that I had one. Those early draft-readers wanted assurance that I’d read Wendell Berry and Wes Jackson. At first this irked me. Sure, I knew their work. Their writings on agriculture and American society have informed my thinking from early adulthood; Berry’s Jayber Crow is one of my all-time favorite novels.

But why was it crucial that I let readers of my story know that?

I wondered if they knew about Maine organic proponent Eliot Coleman; about Australian permaculture pioneer Bill Mollison; about Zimbabwe-born Allan Savory, whose Holistic Resource Management is the most profound treatise on conservation and human decision-making I’ve ever read.

As it was, Shepherd explored my boyhood hero worship of Ohio farm memoirist Louis Bromfield; and my being influenced as a practitioner by Bromfield’s more pragmatic eco-farming successor, Joel Salatin; and my discovery of Charles Allen Smart’s classic memoir, RFD, set in the same region where I ended up struggling to become a farmer. Plus my day job was in publishing, so there was plenty more about books in my memoir.

I finally decided that concerns about my literary lineage were a kind of backhanded praise. As if those readers were saying, “This book is by a writer, not just some farmer.” So I dutifully mentioned Berry and Jackson.

Now it strikes me as odd that nobody mentioned E.B. White (1899–1985).

It is not often that someone comes along who is a true farmer and a good writer. White was both.

///

As a writing man, or secretary, I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost. But it is not easy to communicate anything of this nature.—E.B. White, “The Ring of Time”

I reread One Man’s Meat years ago, about the time I started my own book. I saw that White, a genuine man of letters, was farming on a significant scale for the times. His place was no gentleman’s hobby farm. Or not merely that. Thus he’d earned genuine insights into the mythic pull and the practical difficulty of farming.

I reread One Man’s Meat years ago, about the time I started my own book. I saw that White, a genuine man of letters, was farming on a significant scale for the times. His place was no gentleman’s hobby farm. Or not merely that. Thus he’d earned genuine insights into the mythic pull and the practical difficulty of farming.

It wasn’t until recently, when I read White’s newest biography, Michael Sims’s The Story of Charlotte’s Web: E.B. White’s Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic, that I learned he had a full-time hired man. I didn’t have sense enough to get a helper myself until I’d gotten seriously injured in a farming accident. White had grown up with servants, in a Victorian manse near Long Island Sound, and he and his wife kept several folks on their payroll. She edited and he wrote, both stalwarts and stars for decades at the New Yorker, and for years they commuted between their Maine coast farm and Manhattan.

Sims’s biography is great on the writer’s early years. White grew up in an orderly, affluent world, with two loving parents. His father ran a company that made musical instruments, and adored his youngest child, Elwyn Brooks White: “Oh, the joy, the joy of my little boy; we have lots of good times together.” As for little Elwyn, he was both artistic and outdoorsy. Also: anxious, terrified, sickly, and melancholy. The kid was a hot mess. Having been a similar child myself, I now identify with him even more.

White made good use of his thin-skinned temperament, which fuels his writing and courses in an elegiac vein through it. Only a sensitive soul could have crafted this lovely line, from One Man’s Meat: “I am always humbled by the infinite ingenuity of the Lord, who can make a red barn cast a blue shadow.” (While working at Ohio University Press/Swallow Press, I titled one of our P.L. Gaus Amish mysteries Cast a Blue Shadow.) It’s striking how much of White’s work, including his famous essay “Once More to the Lake,” is about death. This preoccupation was balanced by his love of the city’s busy workaday world and of nature close at hand. Many of us share his adoration for birds and dogs. A few of us see how genuinely he appreciated humble livestock.

And White is the only prominent farmy writer I’ve read who mentions something else we sadly share: allergies. Hay fever is a particularly cruel and ironic affliction for a farmer. White’s description in One Man’s Meat of his periodic malaise could be my own in ragweed season. Writing so personally has kept White’s work fresh, whereas Bromfield’s farm adventures, still hugely enjoyable, have taken on a sepia cast.

I wish during my memoir-writing I’d reread White’s “Death of a Pig,” a fine essay that appeared after those collected in One Man’s Meat. Here’s its famous opening paragraph:

I spent several days and nights in mid-September with an ailing pig and I feel driven to account for this stretch of time, more particularly since the pig died at last, and I lived, and things might easily have gone the other way round and none left to do the accounting. Even now, so close to the event, I cannot recall the hours sharply and am not ready to say whether death came on the third night or the fourth night. This uncertainty afflicts me with a sense of personal deterioration; if I were in decent health I would know how many nights I had sat up with a pig.

“Death of a Pig” bares a timeless dilemma of animal husbandry: tending and heroically ministering to animals that one day you’re going to betray. That jarring shift in roles from nurturer to killer shocked and troubled me as a farmer—I write about it in Shepherd. So here’s a case where my invoking an agrarian-writer forefather would have been highly appropriate. Dang.

Beyond its compelling content, there are writing lessons in “Death of a Pig.” There’s the humor, which takes the curse off this story of death, makes it more entertaining than harrowing. And the humor signals the perspective of a wiser narrator, a survivor who is invoked and mocked at the same time. And who fearlessly gives away the game at the start—the pig died—because he’s come not just to tell the tale but to inform us of the incident’s deeper meaning. White is witty without seeming too pleased with himself; his sentences are strong without feeling ostentatious.

As in his other work, White’s artistry—in the form of persona, style, and narrative structure—shields “Death of a Pig” from the implicit “Why should I read your story?” challenge that haunts personal nonfiction. His material is always solid, his rhythms pleasing, but it’s his wry view of himself and his situations that may be his most effective move in making art from experience.

///

After all, what’s a life, anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die.— Charlotte’s Web

I owe E. B. White a personal debt, too, though that story didn’t make my book either. One day when we were living on our farm in southeastern Ohio, my son, then in fourth grade, came home upset. Fighting back tears, he said, “I’m going to die.” He meant one day, which was worse to deal with, for him and for me, than some passing irritation. Years later, I can’t forget that moment in our family room. Sunlight fills the windows, the green world burgeons outside, and we stand looking at each other. His precocious despair robbed me of easy words. The moment lasted forever—in my mind’s eye we’re paused there still—but my response arrived in an instant.

What I did was turn from his swollen face and pop in a videotape. It was the animated Charlotte’s Web, a Hanna-Barbera musical released in 1973, the year of my graduation from high school, way down in Florida, where I’d grown up grieving my father’s loss of our family farm. My grabbing the movie seemed instinctive, and later it puzzled me—I hadn’t yet read the book and had watched the movie without conscious assessment. Now I can see why I did it. Wilbur barely escapes his intended destiny of becoming bacon. And his aging spider friend Charlotte does expire, though her story continues with her renewal in the form of baby spiders. Rebirth is her final gift as Wilbur gains three new friends from among her 514 offspring.

Friendship is the novel’s suggestion for coping with the death part of the life cycle. It does make a world of sense, if you need to justify fellowship, because people surely do need people. As Woody Allen puts it in his play Don’t Drink the Water, “Life is an adventure you go through with someone you care about.” Charlotte’s Web adds, And if you’re able, fill the world with new allies—procreate. That’s what I’d done.

But my and Charlotte’s reproductive solution wasn’t a relevant strategy for my nine-year-old son. So showing him the video now seems lame—why not question him, hug him, reveal something? Yet in the midst of my comparatively complacent middle-aged life, standing before him blank and panicky, I seized upon Charlotte’s Web.

I’d have a better answer today, I think. But maybe not, in the moment.

White’s magical story was relevant. So I thank him for helping me out of a parental jam. But then E.B. White, as an artist, was so nicely balanced between that hypersensitive life-loving pig and that tough-minded creative spider.

[White once gave an interesting interview to The Paris Review, which I excerpted here. The New York Times ran his obituary.]