The promise of new bookcases

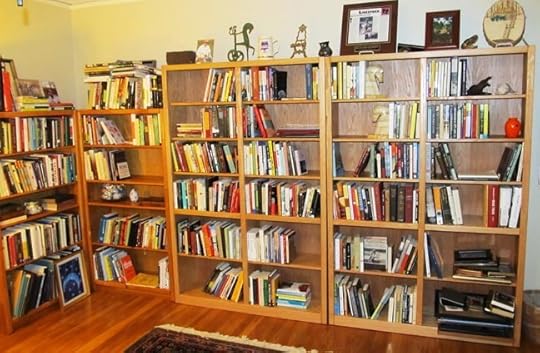

[Alphabetized novels and memoirs form the heart of the new Working Library.]

What’s on our shelves? Only matters of infinite hope.

Most of us when we go into other people’s homes will surreptitiously check out the bookshelves and the music collections, forming our impressions of the owners’ character from what they read or listen to. Most of us know that others do this and so the books in the public spaces will be arranged to particular effect, different from the working books.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Bishop’s book: night reading.]

You told your mate that for every new physical book you bought, two would leave the house—carted to the used bookstore, or to the library, or even secreted in the trash. Yet this has not quite happened. The jig was up when she caught you culling her old books more heavily than you pared your own.In the basement are six full bookcases, pine painted white, each four feet tall and three feet wide. Eighteen feet of books. Your how-to library and oddments, many small thin paperback novels and plays from the spouse’s days as an English teacher. Some children’s books. This library could use another hard sorting—or complete dispersal. But all those gardening and farming and dog and chicken and sheep and cattle books are old friends. Some were your father’s. They reflect long-gone prior lifetimes. Youth itself.

Upstairs, on the main floor of this house, built in 1939, just off the foyer there’s a tidy room with real built-in bookcases. The house’s own small but dignified library: dark, solid walnut shelves. Now a sitting room-TV room-library. The show library. Here are the big hardback novels. And your father’s leather-bound Britannica Great Books—54 unread volumes. Also a complete set, as resonant as a train whistle from your childhood, of the Encyclopedia Britannica. And The Riverside Shakespeare. Books as decoration, as aspiration, as comforting totems.

Like the three oversized paperback iterations of Stewart Brand’s The Whole Earth Catalog—1970s pre-Internet subject-surfing fodder. The iconic black-covered original edition is crumbling from heavy use, high-acid newsprint, and cheap binding.

•

The door to the library was in the corner and the bookcases jutted out into the room so that nobody coming in knew at first whether you were there or not. You felt twice removed from the outside world, secure to dream.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Nabokov’s lectures: old buddy.]

On the second floor, there’s your real library, in a spare bedroom. What you think of as your Working Library. This repository has required the recent acquisition of two huge new bookcases. Oak to match two stout butcher-block cases—each five feet tall and thirty inches wide—your mate gave you years ago. New bookcases were necessary because the small ones were full and hopelessly jumbled. There were stacks of books on the floor around them. Sometimes it was easier to buy a new book suddenly needed for teaching than it was to find the copy you were sure you had. Somewhere.Now the two little bookcases, to the left, hold your books on writing, your essay and poetry collections, your religion, spirituality, and self-help volumes. Some of these summon a younger you: Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature; John Calhoun Merrill’s Existential Journalism; your father’s copy of Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer; his own book, Success Without Soil. You’ve lugged them around since before college and shortly after.

Atop of one of the original bookcases is a huge and growing pile of to-be-read. You promise yourself to peruse these before ordering new books.

And so: center-right on the wall, there they are. The two new capacious Arthur W. Brown bookcases. Each six feet tall and four feet wide; in face-frame style to match their shorter companions. They’re alphabetized. Memoirs and novels. Already read only. Literature only. Well, with a little history and evolutionary psychology on the far right.

The oak is a shade lighter than the old five-footers’ mellow amber. But it will darken imperceptibly as they age.

•

I’ve heard that most academics—most professionals—read in chunks of thirty pages or less. The average length of a professional article. So even when you have the time, on sabbatical or on holiday, after your thirty pages you feel you should be turning to something else.

—Ted Bishop, Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books

[Modernist novel: morning book.]

Now you’re piling up a stack on your dresser for winter break reading. For December and January. Actually two stacks. To the left, books for Spring classes. To the right, books that have lingered long in the to-be-read pile. Like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Which you always think of after you make it to Florida, hear the waves breaking outside your sister’s beach condo, and wish you’d brought.A student expresses amazement that you buy physical books, or keep them. Yet, though no real foe of e-books, you do. You find the presence of physical books aesthetically satisfying and emotionally comforting. Objects of such pleasure. One for each mood. And at least two always going: in a nod to age, an easy night book and a harder one for morning.

Books, to paraphrase your ex-friend Nick Carraway, are matters of infinite hope. Yet, like any object of art, like any perfected medium, they cry out for placement. A person’s home, you posit, must have not just pictures on the wall but at least one serviceable bookcase. Which always has its own story.

Doesn’t yours?