Richard Gilbert's Blog, page 3

October 11, 2016

Politics & our narrative impulse

Many writers possess a visceral antipathy to politics, or at least to politicians. This may be because of politicians’ storied lack of integrity. But we know the constraints they face in our republic of laws, of soaring ideals, and of humanly selfish interests. Still, we’ve seen recently how shockingly low some can go. Yet what a politician does at her or his best is the same magic trick to which writers aspire. Which is channeling and kindling, through all America’s murk, our core truths flickering in overused platitudes. Those verities reflect historic and still-evolutionary ideals that are still evolving. Yes, America is exceptional. But our past is no guarantee. Hence our latent respect for our politicians who try to affirm and foster the best in us. Or in whom we intuit that, under the right circumstances, they will try.

![[Roger Cohen: top of his game.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1476300772i/20825081._SY540_.jpg)

[Roger Cohen: top of his game at the Times.]

Even though on that score this presidential contest should be a boring no-brainer, writers have nonetheless ascended right and left—well, mostly on left but some on the right—to great work. Roger Cohen, a former foreign correspondent who writes columns for the New York Times, wrote a stunning news feature back in early September, “We Need ‘Somebody Spectacular’: Views From Trump Country,” subtitled “Appalachian voters know perfectly well the candidate is dangerous. But they’re desperate for change.”The author of a memoir about his mother, The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family, Cohen went into the rural mid-South and Appalachia to interview and portray Trump supporters. He talked to a woman in Paris, Kentucky—a burg in horse country, right across the river from Ohio, that you drive through to Lexington—who voted for Obama in 2008 but now supports Trump. She operates a boot shop. Cohen’s interview with her, as with others in these travels, was sensitive and searching.

Although now a columnist, here Cohen was functioning as an “objective” journalist. Which usually means in practice that the writer isn’t free to state his thesis as his own but has explored it, tested it. And here, the notion seems simply an honest question. To ask, on our behalf, How can decent, tax-paying, idealistic Americans vote for a man who is anything but? These folks may trend conservative, but they try to be good—they aspire to macro ethics—yet many have supported Trump, the ultimate micro ethicist. Cohn writes freely, revealing his considered view, supported by the research he presents, but within bounds of American mainstream newspapers’ objective format:

The post-convention Trump free fall has run into the obstinacy of his appeal — an appeal that seems to defy every gaffe, untruth and insult. The race is tightening once again because Trump’s perceived character — a strong leader with a simple message, never flinching from a fight, cutting through political correctness with a bracing bluntness — resonates in places like Appalachia where courage, country and cussedness are core values.

Of course, this was before Trump’s latest debacle that revealed him to be in private what anyone could have guessed. In any case, I think what caused Cohen’s editors to slap “Opinion” on his article was this, four sentences in its middle:

Trump can’t reverse globalization. Nor is he likely to save coal in an era of cheap natural gas. His gratuitous insults, evident racism, hair-trigger temper and lack of preparation suggest he would be a reckless, even perilous, choice for the Oval Office. I don’t think he is a danger to the Republic because American institutions are stronger than Trump’s ego, but that the question even arises is troubling.

In the exquisite calculus of mainstream objective journalism, Cohen’s writing so freely and drawing so clearly on his research crossed a line here, however mildly he furrowed his brow. Lest readers not recognize his article as containing such cautious, informed opinion—and bending over backwards to be fair—editors met their objective format’s standard with an “Opinion” label. All well and good, though it’s interesting that a magazine wouldn’t have done that. Newspaper reporters speak in the voice of their institution discharging its public duty; magazines hire “writers” who are expected not to hide but to evince a personality.

![[Adam Gopnik: witty bad boy.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1469099256i/19779490.jpg)

[Adam Gopnik: witty highbrow bad boy.]

At the unabashedly progressive New Yorker, in contrast, below a “News Desk” logo Adam Gopnik’s piece after the second debate on Sunday was headlined “DONALD TRUMP: NARCISSIST, CREEP, LOSER.” Amid this usual sincere yet entertaining outrage over Trump, Gopnik pauses to wonder, with several of us, about Trump’s vulgar tape, “Why should this previously hidden mean-minded monologue mean more than all the other countless unhidden ones, which have already shown Trump to be a brutal, vile vulgarian?” Gopnik probes and ponders this conundrum on our behalf. That’s what writers do. I admired this passage:This was not a dominant American Mussolini asserting himself contemptuously on stage. It was, well, a loser, struggling to impress a very insignificant new acquaintance with pitiful boasts about his masculinity. What runs through the tape is, along with his one-size-fits-all brutality, Trump’s deep insecurity and desperate need for approval from other men. Even the bad language doesn’t seem like that of a native speaker of English, certainly not what the nasty sex predator he wants to portray himself as being would use. “I moved on her like a bitch!” Is that even an idiom?

That last sentence makes me laugh—it’s pure Gopnik and expresses, as well, the New Yorker’s addictively highbrow bad-boy wit. I suspect being laughed at is the one thing Trump can’t stand. Hoping for such freely expressed scorn, increasingly I tend to read the Opinion writers at the New York Times before the news columns. Lately Times columnist Frank Bruni has hit it out of the ballpark repeatedly, most recently with “Donald Trump’s Pathetic Fraternity.” We rely on such professional writers to keep score, and Bruni gives Chris Christie and Rudy Giuliani the thrashing they deserve for making themselves toadies to an odious bully.

Cohen is normally walled off at the newspaper into the Opinion arena I frequent, and was just poaching on the news side. His article occurs against a backdrop of the Times’s internal soul-searching regarding its perceived impartiality or lack thereof. What is fair and balanced with a person like Trump?

[Liz Spayd: stuck in the middle at the Times.]

In “Why Readers See the Times as Liberal,” Liz Spayd, the Times new Public Editor, worries about the newspaper’s alienation of independent, conservative, and even liberal readers. “A paper whose journalism appeals to only half the country has a dangerously severed public mission,” she writes. “And a news organization trying to survive off revenue from readers shouldn’t erase American conservatives from its list of prospects.” Spayd is stuck in the middle between readers and her newspaper’s journalists. It’s got to be an exciting but tough job under any circumstances.The Republican party has become so extreme, ceding even the broad middle to Democrats, I don’t see Spayd’s fret as easily solved. But even I notice anomalies at the Times. Why was Nicholas Kristof’s account last Sunday, “Donald Trump, Groper in Chief,” labeled a column (“OP-ED”) and not a news story? This is a sad and tawdry account of Trump’s mauling pursuit of a woman, who sued him for sexual harassment yet eventually became his girlfriend. Like Cohen, Kristof is a columnist, but his piece is a fairly straightforward news feature article, not a column.

Maybe Kristof got and kept the scoop. Maybe the news side feels it has fully documented Trump’s disrespect for women. Maybe that was what Kristof “had” for his weekly allotted space in the paper’s Sunday Review section. Maybe Times journalists can’t keep up with this kind of news, let alone decide where to put it. These are some likely commonsense explanations.

Nothing makes much sense in this political campaign, and that extends to the journalism it engenders. By virtue of their giving necessary attention, objective-format journalists and even columnists appear to treat Trump as equivalent, to some degree, to his solid opponent. This makes it seem our republic itself doesn’t know what to do. In the end, as always, America’s fate will be left in the hands of those who’ll turn out to vote.

The post Politics & our narrative impulse appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

October 5, 2016

Writing loss: God’s in the details

[Tess protests sitting: Florida, 1981]

Writing about a dog’s death, or even a dead dog, risks sentimentality. I mean, the writer seeking from readers emotion he hasn’t earned. I must like the animal sub-genre of dog deaths, though, because I’ve read so many. And, as my previous posts have explained, I’ve just written an essay concerning my late Labrador, Tess. I realized, writing it, that I should take the advice I’ve given so many freshmen students trying to write about a recently dead grandparent.“Show readers, in scenes and details, your grandparent,” I’ve told them. “You must convey in specifics what you lost to show the world what it lost.” The “world” is grand shorthand for unknown readers, of course. Which in those cases actually is always me and a few peers. We’re the kindly stand-ins for those uncaring readers whose armor the writer must crack. It’s best to think of readers as friends, actually.

But to have a chance of moving readers emotionally, the writer must recreate a singular, not a generic, beloved. The writer must not just summarize what s/he experienced but, as a rule, be specific regarding the remembered gifts of time, talk, and events. This can be hard with a dog, or at least with its middle years, just as with a person. We remember beginnings and endings. I’ve stolen this notion from Jill Christman’s spooky little essay, with an aside on that phenomenon, “Family Portrait: in Third Person,” in superstition [review].

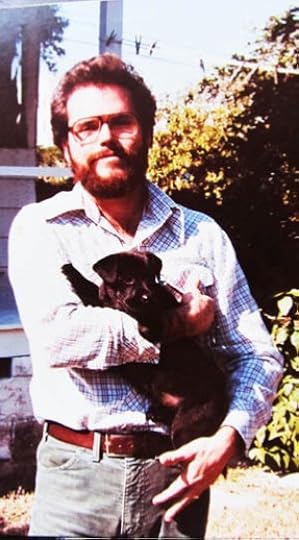

Maybe we remember and can depict the start and end of something because we return so easily to those emotional states. As Virginia Woolf says in “A Sketch of the Past,” strong emotion must leave a trace. But long middle acts blur in literature as in life. Many situations, and therefore emotions, were in play. You remember the day you got the puppy, remember who you were. There’s a snapshot in your mind. In my case, of a bearded newspaper reporter with hair like Elvis, dashing hectically—and heroically, he thought—around at age 26,. And you remember the end of something, when time briefly stopped. In my case, as a book publisher and father of two, age 39 and bald, with a creaky back. That was the guy standing here at Tess’s grave:

The last photograph I took of Tess was in our family room, aiming the camera at my son Tom. I caught only her hindquarters in the background, accidentally, as she moved unnoticed out of the frame. I inadvertently documented what I couldn’t see: as our children grew, Tess had moved to my periphery. She’d stood front and center with me for but a few years, in retrospect, and then shuffled to the edge of a stage grown larger than I’d dreamed possible. Increasingly she’d lived more in Claire and Tom’s world than in mine. Their gentle panting overweight buddy. Seventy-two pounds of love. She was their first animal friend, and their first incomprehensible loss.

My own stunned realization concerns how fast not just canine but human lives pass. (This insight will constantly be forgotten.) What I do understand forever, after Tess’s death so long ago now, is that when you encounter an aged dog, you regard a walking vestige of someone’s former life. You see an old dream. Explaining to others the nature of that dream, let alone understanding it yourself, isn’t simple.

I had a dog and then she died. There’s the basic plot, which lacks explanatory power. Knowing anything worthwhile about that event sequence takes knowing the meaning of “I” and “had” and “then.”

[Tess’s leash, age 34: in Ohio, on its fourth dog. Collar: hers in adolescence.]

I noticed and feared the tendency in “Tess” to plod through the years, our doing this and that. So, again, writing about dogs is the same as writing about people. Except dog lovers may give you a longer leash before they quit reading. Even so, the fundamentals apply. So yes, the middle of “Tess” is where I scratch my head. What’s the story here? Partly it’s who Tess was and what fun she sometimes caused—like the pointlessly exciting night she ate a container of caffeine pills—but also some milestones she was part of. So what links those milestones beyond Tess? As my son used to say in every essay for school, We shall see. I refer, of course, to revision.

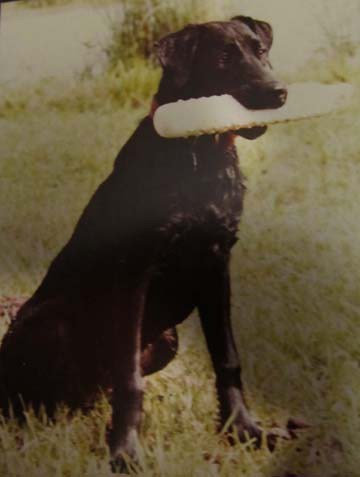

![[Tess: 1982 portrait.]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1475752155i/20761186.jpg)

[Tess: 1982 portrait. In her red collar.]

Now that I’m a grandparent, my past writing advice to my bereft students rings in my ears as I work on “Tess.” Charged with giving their grandchildren bottomless acceptance, endless love, and apt encouragement, grandparents break their little hearts one day. Temporarily. But that’s our job. The better we do it, the more wracking the eighteen-year-old’s sobs in her dorm room.But I know something else now. I’ve already given my Precious One a gift even if I die tomorrow and she never consciously remembers me. Grandparents are an experience. My advice to my students got at that—emphasized the overarching blessing, and its loss, that only details can approach. That’s what I didn’t fully understand when I gave my students advice before I became Little Kathy’s funny old Mokie in his soft stretchy cap. Oh how she laughs at me and at her equally silly dogs.

[Note: I have found a great company in Aurora, CO, that makes quality leather leashes like Tess’s pictured: Bold Lead Designs. This is the fourth and final (probably!) post in a series about writing “Tess.” The previous posts were “Feeling your way“; “Learning to sit“: and “In dogged pursuit.”]

The post Writing loss: God’s in the details appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 28, 2016

Feeling your way

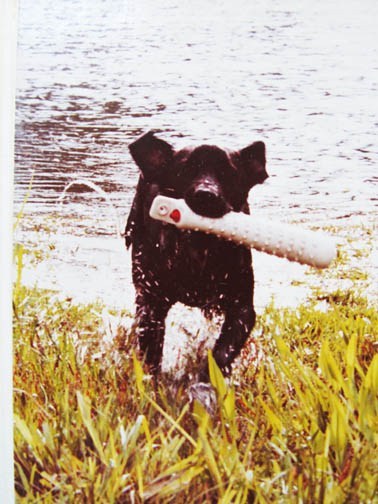

[Tess plunged in, spray flying, and then she’d dog-paddle as fast as she could.]

Editing while writing a draft is what I do. Then I revise—or cut.

“Be careful what you set your heart upon,” someone once said to me, “for it will surely be yours.” Well, I had said that I was going to be a writer, God, Satan, and Mississippi notwithstanding, and that color did not matter, and that I was going to be free. And, here I was, left with only myself to deal with. It was entirely up to me.”—James Baldwin, from the introduction to Nobody Knows My Name

[Tess & I, early Spring 1981.]

I love it when I can write fast, with excitement. Inspired, you might say. But usually I plod, working and reworking sentences as I go. This is “Writing’s dangerous method,” according to a theorist I admire, Peter Elbow. That’s his term for the folly of trying to invoke at the same time the mind that creates along with its critical editor cousin. Hence my pleasure when a grouchier guru, Verlyn Klinkenborg, flatly declared that concept rubbish. There’s no difference, he said in A Few Short Sentences About Writing, between the critical and creative minds. I wrote about his book here, including “Writing by the think-system.”I seem to need to edit as I go because I enter the work that way. I learn what it’s about and find connections I hadn’t imagined. Now, sometimes I’ve ended up cutting, in revision, what I’ve so carefully edited and polished. In my defense, I have read many writers say they work this way.

My fast rate, when I know where I’m going, is a page an hour. But last week I wrote a page on my late dog Tess’s old leash and it took me three hours. I couldn’t have written it fast. Or so I feel. Well, maybe faster, but I’m unsure if it would have gotten me deeper into the story. And I feel it did. Yesterday I finished the first draft of “Tess,” which turned out to be 24 pages. Here’s some of yesterday’s new content, a snippet from the essay’s last section:

What most people wanted from a dog, I realized, was what I’d always had and enjoyed, a lovable couch slug. What I was doing with Tess was different. Much harder, more absorbing, and utterly thrilling when, obeying my command, Tess took me with her on her joyous retrieves. Our complex, challenging partnership was changing us both. I’d never even shot at a duck, however, and wondered how I’d also learn that craft. It appeared I’d have to—for Tess. Or maybe field trials would become our sport and substitute.

[On scored water retrieve, late Summer ’81.]

Imagine, then, Tess on her first retrieve before the watching field trial gallery, everyone gathered on the edge of a cow pasture. She went out like a shot and grabbed the bumper. She spun and ran back, her ears flying. Halfway back, she stopped. Lowered her head. Dropped the bumper. And began to roll ecstatically in the first cow patty she’d ever smelled. Laughter all around. Even I laughed—what could I do?—but my face burned. In the public park where we’d trained, I’d taught Tess to ignore Kentucky Fried Chicken scraps, not cow flops.

“Your first retriever?” someone asked.

Well, yes, actually. Training her from books!

I noticed too that Tess wasn’t as pretty as the other dogs. She was small, scrawny, and sharp-faced. Her coat wasn’t inky black but had a brown cast.

She did better on her water retrieve. She hit the water hard and swam fast, straight out and back.

“She’s a game little thing,” an older man said. She was. Tess was game. Whatever else she was or wasn’t, from her unknown lineage to my inept training, I took those words as truth.

The above may be cut, moved, edited, revised. But for now, it wasn’t just slapped in but written as well as I could. So I don’t do “vomit drafts.” Sure, I write “shitty first drafts,” per Anne Lamott—but not intentionally.

And Mr. Elbow may be right that it’s harmful to creativity to try to draft and perfect at the same time. Elbow’s approach to writing as a process with stages has changed the way composition is taught, from elementary school through college. But I’ve heard more famous writers say they strain, as they write, for perfection. Recently I read that the prolific novelist and celebrated memoirist Harry Crews wrote just 500 words a day—though seven days a week. Do you think he was vomiting? Or was he feeling his way?

[Daughter Claire dresses Tess in fancy neckwear, 1988.]

I have a hunch that Elbow’s way is perfect for young, beginning writes. They lack, as yet, the endurance for long sessions. But they learn to edit and even revise in later, separate sessions. Ultimately some of them put both stages together. Maybe at the same time.For me, polishing as I go works with writing for discovery. I rarely have much of an outline, or any, so I can’t just slam stuff down. Anyway, I’ve concluded that advance outlining seems to work best for journalism and biography and other researched nonfiction. John Irving’s famous outlining notwithstanding, for most people, what’s called creative writing—whether poetry or prose—seems to mean inching along. Dani Shapiro seems to favor such exploration in the first draft, saying in Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life:

It requires faith in the process. The imagination has its own coherence. Our first draft will lead us. There’s always time for thinking and shaping and restructuring later, after we’ve allowed something previously hidden to emerge on the page.

From the rest of her book, I know she writes each line as well as she can before moving on. In Ron Carlson Writes a Story, Carlson also casts a vote for scant preplanning in his primary line of work, short stories:

The process of writing a story, as opposed to writing a letter or a research paper, or even a novel, is a process involving radical, substance-changing discovery. If you let the process of writing a research paper on Romeo and Juliet change the advice the Friar gives to those young people, you’re headed for trouble. If you let the process of writing a story inform and change the advice an uncle gives his niece, you’re probably moving closer to the truth.

[Previously: “Learning to sit” and work.]

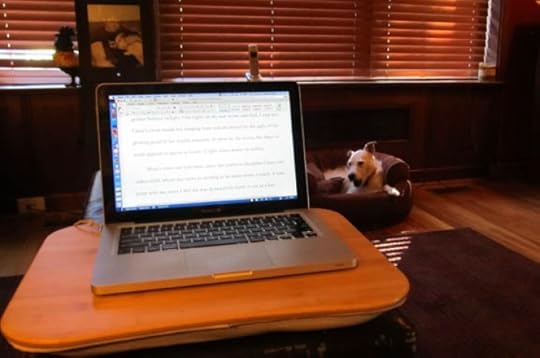

[My reading-writing board, above, from B&N makes my lap a desk. Note computer’s enlarged view and 16-point type.]

The post Feeling your way appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 21, 2016

Learning to sit

[Nice place to write? Photo by Sarah Elizabeth Bailey in Aigues Mortes, southern France, Aug. 2016.]

Writing means hanging in there & discovering. Until a piece is done.

So a writer comes to the page with vision in her heart and craft in her hands and a sense of what a story might be in her head. How do the three come together? My thesis is the old one: they merge in the physical writing—inside the act of writing, not from the outside. The process is the teacher. . . .

The writer is the person who stays in the room.—Ron Carlson, Ron Carlson Writes a Story

[Tess with her beloved bumper.]

In the fine short book Ron Carlson Writes a Story (reviewed), the writer takes us with him as he writes a short story in real time at his desk. There are crises and desires to flee. Also steady work and unforeseen breakthroughs. I’ve thought of Carlson as I’ve worked on my new essay, “Tess,” about my late, beloved Labrador. As I explained in my last post on this essay, the story’s meaning is elusive at this point. Discovering that meaning is what makes writing challenging but addictive to me.The essay’s structure is roughed out, though subject to change. Don’t you almost have to have some structure in mind to start something? Experience gives you a better notion, perhaps, but the actual form and content shift in construction. I have the start drafted and most of the middle and end of “Tess.” I’ve been kind of stuck in finishing the middle’s first draft. I’ve stared at my jotted plan for the last part of this part, a few words, and haven’t felt it. But I’m there to write, so I jump to the essay’s start or its ending to fiddle and add. I know if I show up every day, my subconscious is going to cry uncle and help.

Here’s another snippet of “Tess”—like last week’s excerpt it’s from the essay’s final section, a part of it that’s in second-person address:

Before ice covers the Olentangy River, just a few blocks from your building, you’ll take Tess every afternoon to swim and fetch her Frisbee. The winter will be long for a Florida boy, but you’ll be cozy reading inside with Tess lying nearby on the thin carpet. You aren’t just a broke graduate student, his thick hair starting to thin, living in a clean but threadbare apartment: you’re a guy with a great young dog who loves and needs you. Once she growls at you when you take away her juicy steakbone, and you throw her down, yell into her face, teaching her humans have such rights. Once you blow air at her with your new hair dryer, and when you’re at school she chews it to pieces, teaching you dogs have rights too.

I laughed when I wrote those last two lines yesterday. I’m not sure if I’ll use the time Tess ate a box of NoDoz (caffeine pills) when we stayed overnight at a brother’s while on a road trip. What a night we had! Meantime I’m grateful for yesterday’s little breakthrough. I hadn’t known where, or if, I’d work in the anecdotes of the bone and the dryer. I sure hadn’t planned their juxtaposition and certainly hadn’t seen their amusing relationship when I started writing.

Actually I didn’t feel like writing yesterday. So I set a low bar, told myself I’d just read the essay through. But I’ve learned, with Carlson, that showing up is what matters over the long haul. Showing up gets a piece going and, one day, gets ‘er done. Here’s some ideas that have been helping me to sit there:

Try to be the best version of yourself you can be. Take care of yourself as a human being; be nice to others, if you possibly can. Own your passion and be thankful for it. Inwardly pretend you’ve succeeded wildly at this thing you love. Because if you’re doing it, you have. And because: if it had already made you famous or successful, would you be happier and nicer? Maybe, right? Self-actualized and all that? Then pretend it happened. Meantime, keep creating. Which you’d be doing if you had become all the rage at 29. Right?

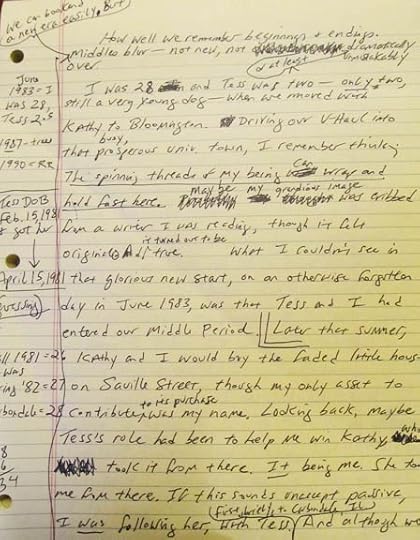

[An early page of “ Tess.”]

Change your location by writing in a different place or way. I usually compose on the computer keyboard at home, so writing in a coffee shop can make me feel more creative. Once in a while, so does writing by hand. But that lasts only briefly, because I hate my handwriting, and I’m prone to hand cramps after years of copious note-taking as a reporter. But if I feel more creative I am more creative. Dani Shapiro says in Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life (discussed) that she always hand-writes her first 30 or 40 pages. Lots of writers say they do, to slow down, to enjoy the tactile, to feel more creative. For good and ill, computers make writing look processed, not handmade; computers are cold and dead. Things you can hold like paper and pen or pencil feel alive; they might tap a different part of your brain.

Change your font. Lovely Baskerville is a recent fave. And so is zooming the display on my computer. Right now I’m writing my essay on Tess in the elegant Garamond serif typeface, enlarged to 16 points, with Word’s display zoomed to 225%. Wow, neat: big fat pretty words. Not the same boring Times New Roman I submit work in. Some pieces—usually less traditional ones, and always this blog—I write in Gill Sans, a delightful sans serif. With my computer’s view vastly enlarged these days, I feel like a mouse tiptoeing among tall buildings. Words. I can circle them, looking up. Gauge the distance to the next block of buildings. I feel myself pulled into this city of words, pulled into the story I’m assembling.

Change your rhythm. Write for 45 minutes and break for 15. During break, no email and the like—instead, I walk around, look at the yard, drink coffee, pull a few weeds, sweep the porch, collect my laundry. I love this, as ideas often flood in during the 15 minutes. My desired total session is three hours, which usually results in three new pages. Usually I take only two 15-minute breaks, skipping it for the last hour, so I get in two-and-a-half hours of work in my three-hour session. Gillian wrote about this technique on Life Moves.

Regardless: read. Especially when stuck or procrastinating. Reading comforts; reading teaches; reading (eventually) inspires. I love Heather Sellers’s advice in Chapter After Chapter (discussed) to pick out three books you want to emulate and read them while you work. Repeatedly reread and study them. I did that when writing my book—a whole series of triplets over those years of writing and revision. Sometimes with an essay I use three model essays. Lately Shapiro’s Still Writing has encouraged me because it’s about living with the emotional rollercoaster of regular writing.

[Next: Do you “vomit draft” or feel your way? What’s best? Why?]

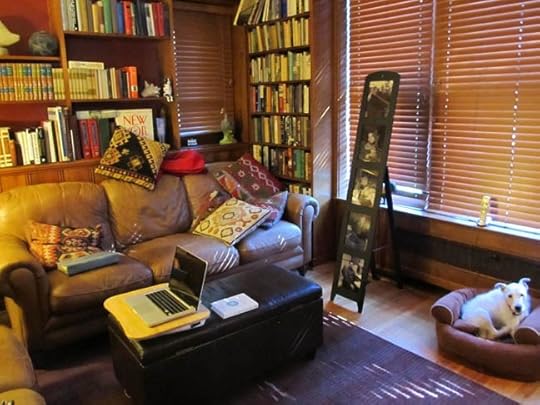

[Where I write lately in our university-owned house. Note: reading-writing board under laptop—found at Barnes & Noble, it makes your lap a comfy desk.]

The post Learning to sit appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 14, 2016

In dogged pursuit

Endings are elusive, middles are nowhere to be found, but worst of all is to begin, to begin, to begin!—Donald Barthelme

[Intent: with Tess at Tallahassee field trial, 1981.]

Lately I’ve been writing essays. I’m in the midst of one right now about Tess, the dog I had when I met Kathy, my wife. Tess took me from youth to middle age. She helped raise our kids.It’s hard to say at this point what the essay is about, other than Tess. Love, I suppose. But as I feel my way through the story, Tess is the frame for what appears. She’s been dead now 22 years, so I’m dealing with the odd mystery of the past.

Which is interesting, and scary—my initial structure helps but provides scant guidance for what should or must or might appear. Every sentence feels like a gift, every paragraph a golden miracle. I could be making a mess. Well, it’s practice. And sometimes it takes my shelving an essay for two years to see how to salvage it.

Having written other essays, though, I know I must try to enjoy this process. Because essays come and go. Their comparatively quick turnaround is great. So is getting a few published here and there. What’s been hard, sometimes, is starting a new one. No basking in a book draft’s long narrative arc—it’s time for the next one. Already. Again.

“Tess” is structured, so far, in reverse chronological order, starting with her death. This morning, I got kind of stuck in the middle and jumped ahead, to near the essay’s end. A snippet:

“What about your choice of a retrieving breed? You didn’t ask me when you picked your wife. If you’re satisfied with that choice, you ought to be able to pick out a dog. If you didn’t do well in that choice, you should have learned something.”—Richard Wolters, Water Dog

As your puppy grows up your old wooden house in Cocoa Village, what most surprises you is that she doesn’t know how to stop when she runs at you to give and receive love. A couple times, you turn out the light before putting Tess in her crate and climbing into your own bed. Your puppy is black; your house is dark. Tess is like an iron cannonball coming at you, hard and fast, across your bedroom floor. She hits your shins just below your knees. You holler and bend double.

You’ve just learned you’ve won a fellowship to Ohio State. You don’t know how hard it will be to rent a decent apartment near campus with a dog. You’re a reporter, gainfully employed, but you’re becoming a student with a dog. You’ll look at some awful places in scary neighborhoods. You’ll rent a decent one, finally, in an ancient brick building in a student ghetto. Look, there’s a place to sell your blood plasma on the corner. You’ll pay extra rent each month for Tess, and keep the place spotless.

But your sleazy landlord will keep your damage deposit when you leave town, because he can. That $300 will be a fortune to you. In time, though, it will be as if he returned it—no, like he gave you a gift—because you’ll never forget the sum, which, like anyone’s remembered past, accrues interest.

As I’ve said before, a reluctance to start, and sometimes to keep working, seems based on fear. It sure is in my case, and I read others say that’s their demon. Fear of failure, I guess. If I really build up a story in my mind, delaying beginning is more likely. Some say the problem resides in having too high standards. “Lower the bar,” they say, and they’re right.

Think of writing for a while as just carpentry, I tell myself. Because the literal truth, if not the largest one, is that writing is just working, moment to moment, piecing together sentences. Quantity creates quality—you must have something to revise. And yet, though it’s work, writing is different from corporeal crafts like carpentry or masonry. Words are symbols, and what’s made from them on the page is actually built in the mind.

For the writer at work, of course, the best metaphor for what s/he’s doing doesn’t matter. I urge myself Just get a draft.

Barthelme’s quote above seems to nail the issue, however, of beginning: starting is hard because you’re starting. Nothing’s yet there. Such work is taxing; such labor is effortful. Dinty W. Moore has indicated he dislikes creating his first drafts, at least compared with revision, which he adores. Although I say I love making sentences, and I do, I can relate. An acquaintance, a man who has published many books, once said to me, “Some people can’t sit there. It’s not that I’m more talented or smarter or anything like that. But I can sit there, hour after hour.” This is what it takes to have a practice instead of relying on inspiration.

[Smiles: Bloomington, Indiana, wedding day, 1983.]

Meantime, I chip away at “Tess,” already past its literal start though without a completed first draft. Since narratives I get excited about while composing are seldom as successful initially as I’ve presumed, I’m hopeful this one works the other way. Maybe it isn’t as muddled as it sometimes appears, coming out. As our Hoosier housekeeper Shirley taught me to say, everything in life or art is what it is “To a point.” So I’m trying to take my doubts less seriously, to a point. Which holds a lesson for all feelings, even positive ones.Art is about the transmission of emotion, as Leo Tolstoy helpfully codified in What is Art? (A gem, but I’d advise skipping or skimming the first four chapters, an academic discussion of what “beauty” means, and plunging right into Chapter V. Maria Popova recently excerpted it brilliantly on Brain Pickings.) But the feelings that arise from trying to make art can be pests. Panic. Doubt. Despair. Even joy—though I’ll take it. In the past, I’ve been driven to my knees in prayer. Lately I employ a less disruptive move, a Buddhist meditation principle of not taking feelings so seriously.

Ah, an emotion has arisen. Hello excitement. Hello hope. Hello frustration. Hello fear, my old foe. How interesting you’ve joined me! All the same, I’ll keep working. Or at least trying. Or just sitting here. Maybe I’ll discover what lies ahead.

[Previous: writing’s high values challenge me. Next: what helps me sit and write.]

The post In dogged pursuit appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 7, 2016

Word by word

[My writing desk one recent day at Panera.]

Writing’s values—intelligence, sensitivity & beauty—challenge me.

“The ability to forgive oneself … is the key to making art, and very possibly the key to finding any semblance of happiness in life.”—Ann Patchett

English departments inherently espouse reverence for thoughtfulness, sensitivity, and comely expression. I codified this recently for myself while speaking with my college’s enrollment director. Strolling down a sidewalk, we’d begun discussing a sharp drop in English majors at our institution. This is endemic nationwide, actually—part of a falloff across the board in the traditional liberal arts. Kids are understandably aiming at paying careers. Across academe, however, lamentation ensues. Today, college seems viewed primarily as career training, not primarily as preparation for living a good (conscious) life. A student can still major in creative writing, say, and get a decent job upon graduation—if she’s been canny enough to obtain internships along the way. But increasingly, in doing so she’s actually seen as bucking the system.

[Patchett & friend from her memoir. AP photo.]

Later, I was writing and got wondering what, exactly, I was trying to do. At the sentence level, where I was laboring, what was I trying to achieve? I’ve been writing with my screen zoomed to 225% and in a font enlarged to 16-point type. The hugeness of the display means only about a paragraph shows on the screen. And it makes each word and sentence I see feel huge. This reminds me to place emphasis where I am, because that’s where the reader is going to be.Feeling my way syntactically and thematically, I’m discovering the story—so that’s one big thing I’m doing. Another is trying to be clear. Another is trying to be elegant. To do those things I fiddle with words, vary sentence structure, and try to end sentences and paragraphs and passages with emphasizing words or ideas. All in an overarching effort to both convey and discover insight. Where, I wondered, before stopping myself so I could work, are such values coming from?

As an undergraduate, I didn’t major in English but in journalism. Trying to be practical myself! Of course the virtues and values of thoughtfulness, sensitivity, and comely written expression are broadly espoused in academe. A good English department concentrates them, and good professors there try to model them. But thankfully, reading itself inculcates such values by example and by implication.

Still, when you’re working at the sentence level, you’re aiming at a mountain in the distance—at story, insight, and impact—while trying to build the trail that . . . leads to the mountain you’re building. This mountain slowly takes form, whether in the bliss of discovering it or in the dread of its impossible slopes. Pondering this contrast between snail’s-pace progress and desired major end result, I think of a sign a friend gave my father for his office: “When you’re up to your ass in alligators, it’s hard to remember that your initial objective was to drain the swamp.”

In writing, your initial objective is to make sentences that make something bigger. You don’t know for a while if it’s mountain or swamp or mirage. And as Ann Patchett’s quote at the top indicates, your final task is to forgive yourself when your story, poem, or essay doesn’t equal what, in a flash, you dreamed.

[Ann Patchett’s quote is from her memoir-in-essays This is the Story of a Happy Marriage, discussed and excerpted brilliantly recently by Maria Popova on Brain Pickings. Next: sometimes you must trick yourself into starting something new—beginning is challenging.]

[Purple mountains majesty . . . Arches National Park-NPS/Kait Thomas.]

The post Word by word appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

September 1, 2016

My essay in Assay

[James Baldwin (1924–1987)]

The fall 2016 issue of Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies, online today, includes my essay “Classics lite: Teaching the Shorter, Magazine Versions of James Baldwin’s ‘Notes of a Native Son’ and Jonathan Lethem’s ‘The Beards.’ ”These are beloved essays. And as my title indicates, they exist in longer and shorter versions—in fact, the periodical versions are technically the “originals,” since they were excerpted to advance the writers’ subsequently published collections. But since the book versions are canonical, condensations may seem heretical. Especially since the famous book version of “Notes of a Native Son” also deals with America’s great topic, race, and tampering with it, in particular, seems at first blush a sacrilege.

In a seminar in graduate school, I studied these two classic American essays—their longer, book versions—together. Both concern the loss of a parent, but they take very different approaches. Hence they’re a nice pair for writers to study and for teachers to teach. Baldwin’s, about the demise of his preacher father when Baldwin was 19, unrolls in a warm, formally structured, and syntactically orotund procession. Lethem’s essay employs a modernistically fractured and conversational approach to portraying his devastation in the wake of his mother’s death, when he was 14.

Here’s a famous passage, and one of my favorites, the same in both iterations of Baldwin’s “Notes of a Native Son”:

He was, I think, very handsome. Handsome, proud, and ingrown, “like a toenail,” somebody said. But he looked to me, as I grew older, like pictures I had seen of African tribal chieftains: he really should have been naked, with warpaint on and barbaric mementos, standing among spears. He could be chilling in the pulpit and indescribably cruel in his personal life and he was certainly the most bitter man I have ever met; yet it must be said that there was something else buried in him, which lent him his tremendous power and, even, a rather crushing charm. It had something to do with his blackness, I think—he was very black—and his beauty, and the fact that he knew that he was black but did not know he was beautiful.

Talk about beauty—what gorgeous prose. The paragraph’s halting rhythm signals deep, stoppered feeling and a hard-won effort to speak the truth. This comes early in the long, dense classically three-act essay.

Lethem’s essay shows his loss structurally: “The Beards” is organized according to his mother’s state of health or length of time dead—but the segments aren’t in chronological order. This implicitly helps show Lethem’s grief as transforming and ongoing. He steadily but subtly plants this notion until he shatters the cool, elliptical façade of “The Beards” with a few heartfelt statements. Here’s one:

The Collected Works of Judith Lethem—

(1978-present, blah-blah-blah.)

. . . What’s one supposed to say when the mask comes off? Is there an etiquette I’m breaking with? John Lennon recorded a song, for his first album after the breakup of the Beatles (what a grand beard that was, art and companionship blended together, and the worshipping world at his feet!), called “My Mummy’s Dead.” I suppose this is my version of that song. I sing it now in order to quit singing it. Mine has been a paltry beard anyway, the peach-fuzzy kind a fifteen-year-old grows, so you still see the childish face beneath. Each of my novels, antic as they may sometimes be, is fuelled by loss. I find myself speaking about my mother’s death everywhere I go in this world.

[Jonathan Lethem: 1964–.]

That’s also from the essay’s book version, in Lethem’s collection The Disappointment Artist. In this example, the book’s and the magazine’s passages are essentially identical, though otherwise the version in the New Yorker has been radically truncated. While I think the lightly edited magazine version of Baldwin’s essay is benign—in fact, the seven space breaks added for Harper’s give welcome resting points for readers—I’m ambivalent about the shortened “The Beards.” However, a coup I scored for my “Classics lite” essay in Assay was an interview with Lethem. He takes a realistic view toward the need by periodicals to shorten long essays. And he’s happy with the shortened one.So I guess I must be, too. At least for certain audiences. As I explain in Assay, college underclassmen and continuing studies students have seemed overwhelmed by the length, intricacy, density, and cultural references in the originals. I’m eager to try the “lite” versions for beginning readers and writers.

In both essays, I can still show how structure can underscore meaning. That may be even easier to show in Lethem’s shortened “The Beards.” And I’ll be more confident that students will actually finish reading it. Teachers, to a degree, must meet students where they are—or at least this one feels he must. To get students to read what they don’t find “relatable” takes a whale of a lot of fear or charisma.

The post My essay in Assay appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 24, 2016

The writing life’s mysteries

Do what you love. Know your own bone; gnaw at it, bury it, unearth it, and gnaw it still.—Henry David Thoreau

[Shapiro on the serial memoirist’s plight.]

Neat sentiment, Henry David, and it seems apt for writer Dani Shapiro, who has quoted it herself. Her love is writing, and especially chewing over the past in memoir. Recently in the New York Times Book Review, however, Shapiro discussed the dilemma of being a serial memoirist.When I write a book, I have no interest in telling all, the way I absolutely do long to while talking to a close friend. My interest is in telling precisely what the story requires. It is along the knife’s edge of this discipline that the story becomes larger, more likely to touch the “thread of the Universe,” Emerson’s beautiful phrase. In this way, a writer might spiral ever deeper into one or two themes throughout a lifetime —theme, after all, being a literary term for obsession—while illuminating something new and electrifying each time.

But some readers of memoir are looking for secrets, for complete transparency on the part of the author, as if the point is confession, and the process of reading memoir, a voyeuristic one. This idea of transparency troubles me, and is, I think, at the root of the serial memoirist’s plight. My goal when I sit down to write out of my own circumstances is not to make myself transparent. In fact, I am building an edifice. Stone by stone, I am constructing a story. Brick by brick, I am learning what image, what memory belongs to what.

Shapiro makes subtle and profound distinctions. Distinctions between publishing memoir and privately journaling. Between personal writing and mainstream journalism. Between life stories and idle gossip. Between settling scores and discovering deeper truths. This is invaluable in extending the conversation on memoir, and in helping refine understanding of the burgeoning genre.

Maybe she counts among her four memoirs referred to in the Times her latest book, which I’ve been reading, Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life. Her website says it’s “at once a memoir, meditation on the artistic process, and advice on craft . . .” I’m impressed by Shapiro’s frankness and depth. She addresses directly critics’ charges or anyone’s fear of wallowing, of having a different story than your siblings do, of inflicting on others your navel-gazing. Given this backdrop, and our societal and human interest in moving on, she seems rather brave. I flagged a couple passages on Page 135:

To write is to have an ongoing dialogue with your own pain. To scream to it, with it, from it. To know it—to know it cold. Whether you’re writing a biography of Abraham Lincoln, a philosophical treatise, or a work of fiction, you are facing your demons because they are there. To be alone in a room with yourself and the contents of your mind is, in effect, to go to this place, whether you intend to or not. . . .

The mess is holy. What we inherit—and how we come to understand what we inherit—is all we have to work with. There is beauty in what is. Every day, when I sit down to work, I travel to that place. Not because I’m a masochist. Not because I live in the past. But because my words are my pickaxe . . .

Maybe this is why writers, or at least memoirists, get comfortable with using memories that might disturb others to broadcast. The wonder is why some writers—we’ve all read them—are not crippled by guilt or pain. The reasons for resilience must vary. But it seems to me that, at base, everyone must start with love for literary art. Love for its beauty in form and content, a beauty that rests finally on honesty.

That’s such a high bar! Implied in it is the highest honesty—the ability to see your story from different angles, to see another’s burden and story, to interrogate your own settled master narrative. I think this is what Shapiro means when, reflecting the influence of Buddhism, she quotes Jack Kornfield, author of A Path with Heart: A Guide Through the Perils and Promises of Spiritual Life:

all of life can be summed up in these three words: not always so.

She mentions Steven Millhauser’s impressive New Yorker story, “Getting Closer,” about a nine-year-old boy’s sudden awareness of time—after which, everything for him is forever changed. Memoirists might well ask themselves, Shapiro suggests, why they’re telling the story now? What has changed? This of course points, once again, to the fair-minded writer at the desk now, struggling to understand, and gracefully share, the meaning of what happened to her so long ago.

The post The writing life’s mysteries appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

August 17, 2016

Survivor. Sufferer. Witness.

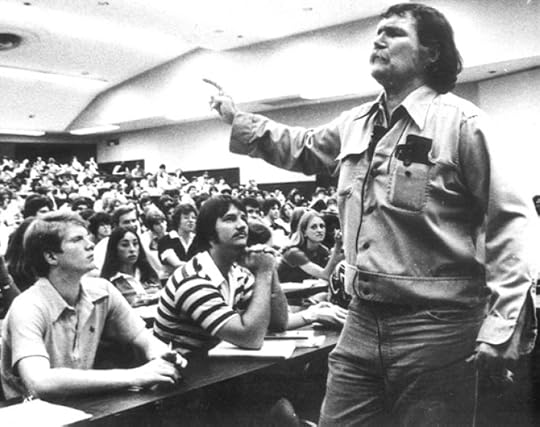

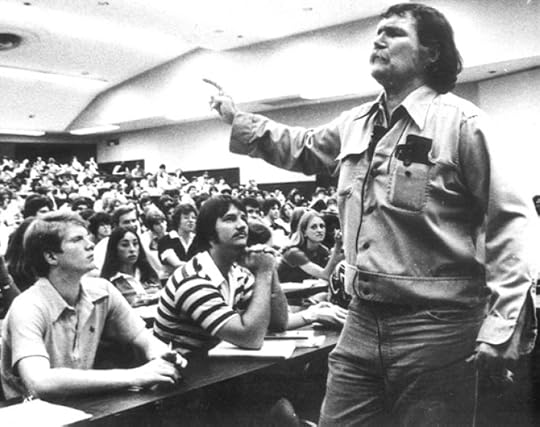

[Harry Crews holds forth. He was at University of Florida when I attended.]

New biography of writer Harry Crews reveals the pain he carried.

Blood, Bone and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews by Ted Geltner. University of Georgia Press, 360 pp.

People yearn simply to be good. But that’s a hard wish because most people are good but they sure aren’t simple. Take the late Harry Crews (1935–2012), a prolific novelist and nonfiction writer who became infamous for his drinking, brawling, infidelity, and outrageous public behavior. Even when at last long-successful and revered, Crews consciously strove to alienate others. He wore grungy clothes, drove junker cars, sported a Mohawk hairstyle, and tattooed on his arm alarming words from a poem by E.E. Cummings:

How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mister Death?

What kind of man believes himself to be a freak, declares writers freaks, writes solely about freaks and misfits—including, in his journalism, Hollywood celebrities, prostitutes, and dog fighters—and makes being a freakish outsider the core of his personal and aesthetic ethos?

Ted Geltner answers this conundrum in his absorbing Blood, Bone and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews. I hadn’t read a literary biography in a long time, and read this one because I’m writing a review of Crews’s classic memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place for River Teeth; A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative in the fall.

My interest also was kindled because I recently wrote a 15-page essay about my time at University of Florida when Harry Crews was there as the famous writing teacher. I’d had a near miss with a bad man when I was 19, working on a farm in Melbourne, and my essay is about that and my writing apprenticeship at UF and how the two connect. How I really needed Crews to teach me how to use the incident properly instead of writing around it in fiction and nonfiction as I did. At last I’ve written that story of my close call and included Crews.

[Crews was a legendary & scary teacher.]

Oh, the appeal and fear Harry Crews held for me. My father having sold our Georgia farm when I was a boy, I’d grown up in a Florida beach town and felt Crews, a true Georgia grit, would smell it on me. He was authentic; I wasn’t. I did take a fiction-writing class from one of his graduate students, a burly fellow with a shaved head, fairly intimidating itself in the mid-70s.Geltner’s book made we want to read Crews’s darkly comic novels, and I was able to read a key part of his unfinished second memoir, Assault of Memory. The excerpt was published as the essay “Leaving Home for Home,” in the Winter 2007 issue of Georgia Review (you can access the essay here by clicking on Read Online Free and setting up a temporary JSTOR account). I was spurred by Geltner’s revelations about the abuse Crews suffered as a boy. Crews writes in this essay that he and his young friends were molested by male and female motorists when they hitchhiked.

And he also reveals that his much-older brother abused him emotionally, physically, and apparently sexually. The essay is set when Crews was ten and flees a Greyhound bus because of a racist who is threatening him for being friendly toward the black people seated behind them. Crews wanders across a landscape beset by thugs and sexual predators, trying to get home, but must also avoid his brother waiting there. A kindly prostitute gives him shelter for the night.

My God, I thought, the man suffered enough trauma for ten lifetimes. I don’t mean to reduce him to this—he was gifted, and pursued that gift. He wrote his 500 words daily. He’d never see himself as a victim, it was clear from Geltner’s study, or even as a “survivor” probably. But one can’t help but think his brother’s cruelties along with incidental abuses scarred him. I also thought of such a different writer, Virginia Woolf, who likewise late in life began to write about being sexually abused by her stepbrothers.

In truth, Crews’s masterpiece, his memoir A Childhood: The Autobiography of a Place, cannot be understood, at least it wasn’t by me, in the traumatic terms Crews spoke of his childhood without knowing what he was reluctant to reveal. Even allowing for the way I romanticize agrarian life, despite the poverty and illness and accidents he depicts in A Childhood, he also conveys a world that seemed cohesive and possessed magical elements. So I was shocked several months ago after my most recent rereading by his comments. I figured I’d missed something. Really there was so much beneath the surface he hadn’t yet addressed. As an apparent indicator of the psychic pain A Childhood stirred up, afterward Crews didn’t complete another book for eleven years. Before the memoir, he’d published eight novels in eight years,

As I begin another reading of A Childhood for my review, I hope to focus on the precise reasons why I and others revere this unusual memoir. But Geltner’s Blood, Bone and Marrow and Crews’s “Leaving Home for Home” have imparted knowledge that inescapably casts its own shadow.

The post Survivor. Sufferer. Witness. appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

Survivor. Witness.

[Harry Crews holds forth. He was at University of Florida when I attended.]

New biography of writer Harry Crews reveals the pain he carried.

Blood, Bone and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews by Ted Geltner. University of Georgia Press, 360 pp.

People yearn simply to be good. But that’s a hard wish because most people are good but they sure aren’t simple. Take the late Harry Crews (1935–2012), a prolific novelist and nonfiction writer who became infamous for his drinking, brawling, infidelity, and outrageous public behavior. Even when at last long-successful and revered, Crews consciously strove to alienate others. He wore grungy clothes, drove junker cars, sported a Mohawk hairstyle, and tattooed on his arm alarming words from a poem by E.E. Cummings:

How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mister Death?

What kind of man believes himself to be a freak, declares writers freaks, writes solely about freaks and misfits—including, in his journalism, Hollywood celebrities, prostitutes, and dog fighters—and makes being a freakish outsider the core of his personal and aesthetic ethos?

Ted Geltner answers this conundrum in his absorbing Blood, Bone and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews. I hadn’t read a literary biography in a long time, and read this one because I’m writing a review of Crews’s classic memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place for River Teeth; A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative in the fall.

My interest also was kindled because I recently wrote a 15-page essay about my time at University of Florida when Harry Crews was there as the famous writing teacher. I’d had a near miss with a bad man when I was 19, working on a farm in Melbourne, and my essay is about that and my writing apprenticeship at UF and how the two connect. How I really needed Crews to teach me how to use the incident properly instead of writing around it in fiction and nonfiction as I did. At last I’ve written that story of my close call and included Crews.

[Crews was a legendary & scary teacher.]

Oh, the appeal and fear Harry Crews held for me. My father having sold our Georgia farm when I was a boy, I’d grown up in a Florida beach town and felt Crews, a true Georgia grit, would smell it on me. He was authentic; I wasn’t. I did take a fiction-writing class from one of his graduate students, a burly fellow with a shaved head, fairly intimidating itself in the mid-70s.Geltner’s book made we want to read Crews’s darkly comic novels, and I was able to read a key part of his unfinished second memoir, Assault of Memory. The excerpt was published as the essay “Leaving Home for Home,” in the Winter 2007 issue of Georgia Review (you can access the essay here by clicking on Read Online Free and setting up a temporary JSTOR account). I was spurred by Geltner’s revelations about the abuse Crews suffered as a boy. Crews writes in this essay that he and his young friends were molested by male and female motorists when they hitchhiked.

And he also reveals that his much-older brother abused him emotionally, physically, and apparently sexually. The essay is set when Crews was ten and flees a Greyhound bus because of a racist who is threatening him for being friendly toward the black people seated behind them. Crews wanders across a landscape beset by thugs and sexual predators, trying to get home, but must also avoid his brother waiting there. A kindly prostitute gives him shelter for the night.

My God, I thought, the man suffered enough trauma for ten lifetimes. I don’t mean to reduce him to this—he was gifted, and pursued that gift. He wrote his 500 words daily. He’d never see himself as a victim, it was clear from Geltner’s study, or even as a “survivor” probably. But one can’t help but think his brother’s cruelties along with incidental abuses scarred him. I also thought of such a different writer, Virginia Woolf, who likewise late in life began to write about being sexually abused by her stepbrothers.

In truth, Crews’s masterpiece, his memoir A Childhood: The Autobiography of a Place, cannot be understood, at least it wasn’t by me, in the traumatic terms Crews spoke of his childhood without knowing what he was reluctant to write about. Even allowing for the way I romanticize agrarian life, despite the poverty and illness and accidents he depicts in A Childhood, he also conveys a world that seemed cohesive and possessed magical elements. So I was shocked several months ago after my most recent rereading by his comments and figured I’d missed something. Really there was so much beneath the surface he hadn’t yet addressed. As an apparent indicator of the psychic pain A Childhood stirred up, after, having produced eight novels in eight years, Crews didn’t complete another book for eleven years.

As I begin another reading of A Childhood for my review, I hope to focus on the precise reasons why I and others revere this unusual memoir. But Geltner’s Blood, Bone and Marrow and Crews’s “Leaving Home for Home” have imparted knowledge that inescapably casts its own shadow.

The post Survivor. Witness. appeared first on Richard Gilbert.