Feeling your way

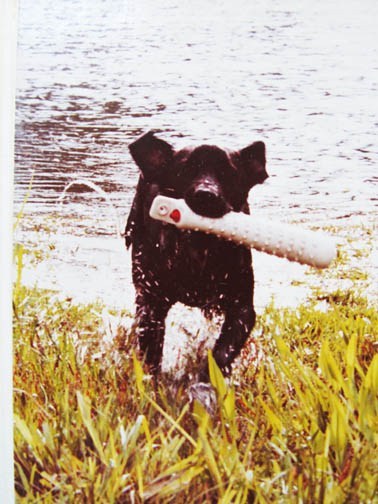

[Tess plunged in, spray flying, and then she’d dog-paddle as fast as she could.]

Editing while writing a draft is what I do. Then I revise—or cut.

“Be careful what you set your heart upon,” someone once said to me, “for it will surely be yours.” Well, I had said that I was going to be a writer, God, Satan, and Mississippi notwithstanding, and that color did not matter, and that I was going to be free. And, here I was, left with only myself to deal with. It was entirely up to me.”—James Baldwin, from the introduction to Nobody Knows My Name

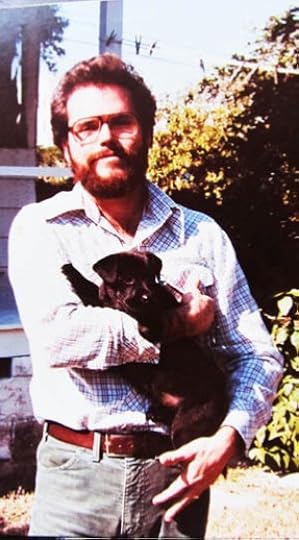

[Tess & I, early Spring 1981.]

I love it when I can write fast, with excitement. Inspired, you might say. But usually I plod, working and reworking sentences as I go. This is “Writing’s dangerous method,” according to a theorist I admire, Peter Elbow. That’s his term for the folly of trying to invoke at the same time the mind that creates along with its critical editor cousin. Hence my pleasure when a grouchier guru, Verlyn Klinkenborg, flatly declared that concept rubbish. There’s no difference, he said in A Few Short Sentences About Writing, between the critical and creative minds. I wrote about his book here, including “Writing by the think-system.”I seem to need to edit as I go because I enter the work that way. I learn what it’s about and find connections I hadn’t imagined. Now, sometimes I’ve ended up cutting, in revision, what I’ve so carefully edited and polished. In my defense, I have read many writers say they work this way.

My fast rate, when I know where I’m going, is a page an hour. But last week I wrote a page on my late dog Tess’s old leash and it took me three hours. I couldn’t have written it fast. Or so I feel. Well, maybe faster, but I’m unsure if it would have gotten me deeper into the story. And I feel it did. Yesterday I finished the first draft of “Tess,” which turned out to be 24 pages. Here’s some of yesterday’s new content, a snippet from the essay’s last section:

What most people wanted from a dog, I realized, was what I’d always had and enjoyed, a lovable couch slug. What I was doing with Tess was different. Much harder, more absorbing, and utterly thrilling when, obeying my command, Tess took me with her on her joyous retrieves. Our complex, challenging partnership was changing us both. I’d never even shot at a duck, however, and wondered how I’d also learn that craft. It appeared I’d have to—for Tess. Or maybe field trials would become our sport and substitute.

[On scored water retrieve, late Summer ’81.]

Imagine, then, Tess on her first retrieve before the watching field trial gallery, everyone gathered on the edge of a cow pasture. She went out like a shot and grabbed the bumper. She spun and ran back, her ears flying. Halfway back, she stopped. Lowered her head. Dropped the bumper. And began to roll ecstatically in the first cow patty she’d ever smelled. Laughter all around. Even I laughed—what could I do?—but my face burned. In the public park where we’d trained, I’d taught Tess to ignore Kentucky Fried Chicken scraps, not cow flops.

“Your first retriever?” someone asked.

Well, yes, actually. Training her from books!

I noticed too that Tess wasn’t as pretty as the other dogs. She was small, scrawny, and sharp-faced. Her coat wasn’t inky black but had a brown cast.

She did better on her water retrieve. She hit the water hard and swam fast, straight out and back.

“She’s a game little thing,” an older man said. She was. Tess was game. Whatever else she was or wasn’t, from her unknown lineage to my inept training, I took those words as truth.

The above may be cut, moved, edited, revised. But for now, it wasn’t just slapped in but written as well as I could. So I don’t do “vomit drafts.” Sure, I write “shitty first drafts,” per Anne Lamott—but not intentionally.

And Mr. Elbow may be right that it’s harmful to creativity to try to draft and perfect at the same time. Elbow’s approach to writing as a process with stages has changed the way composition is taught, from elementary school through college. But I’ve heard more famous writers say they strain, as they write, for perfection. Recently I read that the prolific novelist and celebrated memoirist Harry Crews wrote just 500 words a day—though seven days a week. Do you think he was vomiting? Or was he feeling his way?

[Daughter Claire dresses Tess in fancy neckwear, 1988.]

I have a hunch that Elbow’s way is perfect for young, beginning writes. They lack, as yet, the endurance for long sessions. But they learn to edit and even revise in later, separate sessions. Ultimately some of them put both stages together. Maybe at the same time.For me, polishing as I go works with writing for discovery. I rarely have much of an outline, or any, so I can’t just slam stuff down. Anyway, I’ve concluded that advance outlining seems to work best for journalism and biography and other researched nonfiction. John Irving’s famous outlining notwithstanding, for most people, what’s called creative writing—whether poetry or prose—seems to mean inching along. Dani Shapiro seems to favor such exploration in the first draft, saying in Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life:

It requires faith in the process. The imagination has its own coherence. Our first draft will lead us. There’s always time for thinking and shaping and restructuring later, after we’ve allowed something previously hidden to emerge on the page.

From the rest of her book, I know she writes each line as well as she can before moving on. In Ron Carlson Writes a Story, Carlson also casts a vote for scant preplanning in his primary line of work, short stories:

The process of writing a story, as opposed to writing a letter or a research paper, or even a novel, is a process involving radical, substance-changing discovery. If you let the process of writing a research paper on Romeo and Juliet change the advice the Friar gives to those young people, you’re headed for trouble. If you let the process of writing a story inform and change the advice an uncle gives his niece, you’re probably moving closer to the truth.

[Previously: “Learning to sit” and work.]

[My reading-writing board, above, from B&N makes my lap a desk. Note computer’s enlarged view and 16-point type.]

The post Feeling your way appeared first on Richard Gilbert.