Making life add up in art

Bruce Springsteen’s bio reveals a steel will & a fragile psyche.

Now look at me baby

Struggling to do everything right

And then it all falls apart

When out go the lights

I’m just a lonely pilgrim

I walk this world in wealth

I want to know if it’s you I don’t trust

‘Cause I damn sure don’t trust myself

—“Brilliant Disguise,” from Tunnel of Love

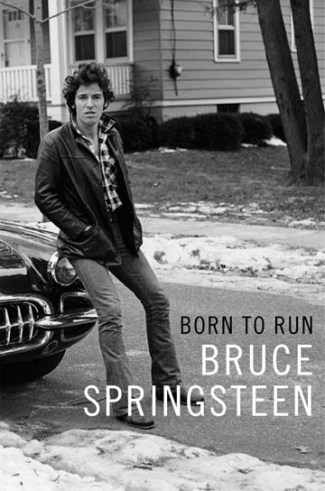

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen. Simon & Schuster, 508 pp.

One of Bruce Springsteen’s horde of mid-1970s fans, I began drifting away from The Boss in the mid-1980s after attending one of his mega Born in the USA concerts, in Cincinnati. Bruce is going for it, the faithful said ruefully. “It” being mega stardom. Here was our feral bard all cleaned up—a clean-shaven hunk with a headband and bulging muscles—finally fit for mass consumption. When he looks back on photographs of himself then, Springsteen says in his recent autobiography Born to Run, he looks “just gay.”

I saw him a couple of years ago at a typically joyous gathering in Columbus, impressed by his commitment to performance and by the endurance of his always-approachable persona. When he backed against a stadium bulwark, a fan reached down from his seat and kneaded Springsteen’s sweaty scalp, twisting his head to and fro, as if mauling a beloved dog. Good old Bruce just smiled and kept singing.

So I was surprised, even knowing Springsteen’s songs, when I heard him say, promoting Born to Run on Fresh Air, that he’s been in therapy since 1983. This was one of the reasons I bought Born to Run. How is that possible for such a beloved man? For rocker so incredibly charismatic and vibrant yet down to earth? For an American success story? What’s the deal, Bruce?

Springsteen answers my question early in Born to Run, revealing the details and circumstances of his exquisitely screwed-up family. And why and how he bore the brunt. But also the curse of depression, and maybe bipolar disorder, that plagues his kin and himself. A figure at once grounded and mythic, Springsteen reveals his behind-the-scenes heroic struggle with emotional baggage and mental illness. That’s his double-whammy, existential and biological. He experienced his father’s rage toward him—and outright contempt—plus he inherited his old man’s disease. Add to that how hard it is just being human, let alone a celebrity, and oh mercy.

The theme of his interior struggle isn’t incidental but, threaded through his massive book, it’s what he’s come to explore and to offer. He’s a good writer—no real surprise—whose prose is conversational and rhythmic. I wished an editor had nixed quotes around so many words used metaphorically and fixed Springsteen’s British usage “amongst,” used always in place of “among,” though a friend who read the book didn’t notice such nits. He shared my frustration, however, with Springsteen’s impressionistic timeline—especially early on, where you want it. Was that watershed gig in middle school or high school?

The matter of Springsteen’s songwriting—the nitty gritty of how he does it—is what some readers will miss. Instead we get his savvy and hyper aware analysis of his work. For instance, I’ve always thought his 1975 breakout album, Born to Run, sounds over-produced, but didn’t expect Springsteen’s confirming verdict on its flawed “bombastic big rock sound.” But, he adds, offering a deeper insight, that’s the dark side of its “beauty, power, and magic.” He’s exquisitely tuned to tradeoffs—he wants it all—and struggles to accept them. Many fans, including me, call that album’s first track, “Thunder Road” our favorite song. Its timeless story opens scenically, amidst a tinkling piano and plangent saxaphone—

The screen door slams

Mary’s dress waves

Like a vision she dances across the porch

As the radio plays

—and the song’s subsequent lines, the successful suitor’s nod to those who lost, helped get him placed on the covers of Time and Newsweek, in the same week, as the future of rock:

The ghosts in the eyes of all the boys

you sent away

they haunt this dusty beach road

in the skeleton frames of burnt-out Chevrolets

He can channel not only the yearning romance of male desire but its murderously destructive dark side, as in his haunting “State Trooper,” from 1982’s Nebraska. Springsteen sings in a Brando-esque sotto voce that he punctuates with psychotic yips:

Maybe you got a kid maybe you got a pretty wife

The only thing that I got’s

Been bothering me my whole life

Mister state trooper please don’t stop me

Please don’t stop me please don’t stop me

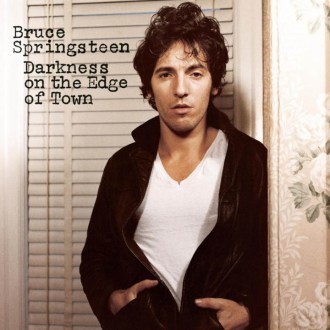

He’s especially good at pairing despair and hope. He does it with the bleak words and bouncy melody of “Born in the USA,” and in lines like these from “The Promised Land,” on my favorite Springsteen album, Darkness on the Edge of Town:

I’ve done my best to live the right way

I get up every morning and go to work each day

But your eyes go blind and your blood runs cold

Sometimes I feel so weak I just want to explode

Explode and tear this town apart

Take a knife and cut this pain from my heart

Find somebody itching for something to start

The dogs on main street howl,

’cause they understand,

If I could take one moment into my hands

Mister, I ain’t a boy, no, I’m a man,

And I believe in a promised land

The mating of words and music, a mystery to most of us, and what makes music such a profoundly moving art form, may be too hard to explain. Does any musician—can any musician—illuminate this? There are hints in Born to Run that Springsteen likes to hole up, immerse. Also that there’s a tension between that and being a family man. He’s demonstrably a steady, hard worker, which indicates a consistent approach. But the core of his process may be intuitive enough that he doesn’t want to jinx it by analyzing it for us. Or maybe it’s usually a slog while clutching a melody or a few lines, too blurry and tedious to explicate.

One thing’s for sure: it’s all he’s ever done. Born to Run reveals that the only other job he ever held was a summer spent as an uncle’s yard boy and neighborhood handyman when he was 15. Playing music in bars was his blue-collar apprenticeship, a genuine if unusual one. Against his father’s scarring rage and depression, his loving mother fed his dream.

Springsteen animates this journey with vivid profiles of his bandmates and others along the way. “Of course I thought I was a phony—that is the way of the artist—but also thought I was the realest thing you’d ever seen,” he says of himself, coming up. Springsteen and his E Street Band aspired to be “understood and accessible,” he says, and that’s his generous effort in Born to Run.

Again, however, there’s always the flip side, where the magic lives:

One plus one equals two. It keeps the world spinning. But artists, musicians, con men, poets, mystics and such are paid to turn that math on its head, to rub two sticks together and bring forth fire. Everybody performs this alchemy somewhere in their lives, but it’s hard to hold onto and easy to forget. People don’t come to rock shows to learn something. They come to be reminded of what they already know and feel deep down in their gut. That when the world is at its best, when we are at our best, when life feels fullest, one and one equals three.

[The Ultimate Classic Rock web site ranks Springsteen’s 20 studio albums from worst to best. Their top three: 1. Tunnel of Love 2. Nebraska 3. Darkness on the Edge of Town. Last October, Springsteen appeared at The New Yorker Festival for a talk with David Remnick.]

The post Making life add up in art appeared first on Richard Gilbert.