Reading as writers

[Sunrise over Melbourne Beach, Florida. March 2016.]

Teaching shorter versions of Baldwin’s & Lethem’s narrative essays.

Gay Talese’s essay in the current New Yorker, “The Voyeur’s Motel,” makes me wish I were still teaching journalism. It’s about a man who bought a motel near Denver in the late 1960s so he could spy on guests, which he did for decades. It’s creepy and horrifying, his behavior and Talese’s tale, but you can’t look away. Or stop thinking about the man and what he saw with his wife, including their aim, sex, but also lots of disquieting behavior, including a murder. Talese’s pleasurable but ethically problematic account is over 30 pages. Yet students would gobble it up like candy.

Reading this page-turner narrative essay coincided with my recent brooding about reading. This involves mine and the reading I assign to students. Most people seem to read largely to seek pleasure. Do we grow by tackling more difficult work? Probably—but so what, for casual readers? For students, must I stick with something that’s genius but to them not very enjoyable? Since I read largely as a writer now, I’ve agreed to the harder path, but most students haven’t.

After my share of classroom disasters, I’ve learned to meet students where they are. Which partly means assigning books, essays, and stories that they’ll at least tolerate . I also must admire the works, of course. Tobias Wolff’s This Boy’s Life is genius and so is Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. Which do you think a class of eighteen year olds would actually read? Most undergraduates, even many writing majors, cannot yet appreciate certain works.

For one thing, they aren’t yet old enough to identify readily with older folks and certain situations. For another, they lack endurance, especially for dense exposition.

///

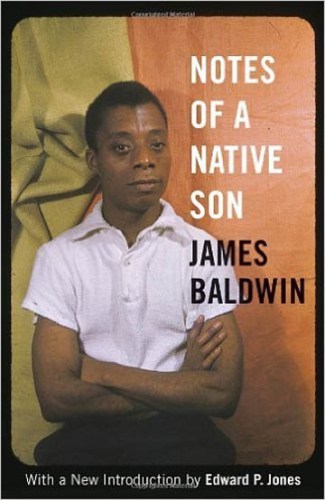

[Native Son: Baldwin was only 31.]

Teaching senior citizens this year in continuing studies classes, I expected a big difference. Indeed they could identify with a wider range of ages. But they were beginning writers, too, and they balked at demanding nonfiction. Such as James Baldwin’s classic essay “Notes of a Native Son,” which depicts his and his father’s cruel suffering caused by racism. These older students seemed to respect it, but most of them didn’t seem to enjoy it. Baldwin’s prose, to me, is delicious, his story compelling, his ideas profound. But “Notes of a Native Son” is dense, with long, unbroken expository paragraphs. And only two space breaks, which demarcate the essay’s numbered sections, emphasizing its classical three-act structure. Just two slender spaces where readers can regroup.From now on, for beginning writers—and probably for everyone except graduate students—I’ll probably assign the shorter version of “Native Son” that first appeared as “Me and My House” in Harper’s Magazine (it is available to subscribers as a pdf download; nonsubscribers must purchase the entire issue, on Harper’s website, for $6.99). This publication came in November 1955, when Baldwin was 31, and it’s a page and a half shorter than what appeared that same year in Baldwin’s collection Notes of a Native Son as its title essay. Whether Baldwin cut it himself to fit the magazine’s space, or whether an editor pared down his essay, it’s a brilliant editing job.

Probably worth studying in their own right, the truncated essay’s deletions are oddly unnoticeable—a few orotund clauses clipped on this page, an elaborating sentence shaved on the next. You’re aware only of the essay feeling crisper and reading more quickly. The editor, or Baldwin, also added seven space breaks within the essay’s numbered sections—three in the long first part, one in the second, and three in the third—where readers can rest and reflect.

The essay’s first cut is one of its most severe. Here’s the original paragraph about Baldwin’s father:

He had been born in New Orleans and had been a quiet young man there during the time that Louis Armstrong, a boy, was running errands for the dives and honky-tonks of what was always presented to me as one of the most wicked of cities. My father never mentioned Louis Armstrong, except to forbid us to play his records, but there was a picture of him on our wall for a long time. One of my father’s strong-willed female relatives had placed it there and forbade my father to take it down. He never did, but he eventually maneuvered her out of the house and when, some years later, she was in trouble and near death, he refused to do anything to help her.

Here’s the shortened version, which moves quickly away from the Louis Armstrong digression into the famous following passage in which Baldwin analyzes his father’s psyche:

He had been born in New Orleans and had been a [quiet] young man there during the time that Louis Armstrong, a boy, was running errands for the dives and hanky-tanks of what was always presented to me as one of the most wicked of cities. He was, I think, very handsome. Handsome, proud, and ingrown, “like a toenail,” somebody said. But he looked to me, as I grew older, like pictures I had seen of African tribal chieftains: he really should have been naked, with warpaint on and barbaric mementos, standing among spears. He could be chilling in the pulpit and indescribably cruel in his personal life and he was certainly the most bitter man I have ever met; yet it must be said that there was something else buried in him, which lent him his tremendous power and, even, a rather crushing charm. It had something to do with his blackness, I think—he was very black—and his beauty, and the fact that he knew that he was black but did not know he was beautiful.

Since this represents one of the few sustained cuts, it’s useful for debating whether the shorter version is better or lesser. To me, Baldwin elsewhere sufficiently depicts his father’s prickly nature and vindictiveness. A writer whose aesthetic judgment I usually respect, however, gave me grief when I first pondered teaching the Harper’s version. Granted, “Notes of a Native Son” is iconic. I call it America’s greatest essay because it’s about America’s great topic, race, and because of its memoiristic and structural brilliance.

Most people, like my writer friend, aren’t aware that “Notes of a Native Son” initially appeared in slightly more slender form. I say ”Me and My House” is better or lesser than the canonical version depending on its audience. I’d rather have students read it than zone out, or not be exposed at all, to Baldwin’s ideas, artistry, and moving story.

///

[Jonathan Lethem.]

What finally cemented my conviction was my experience this semester teaching another masterpiece, Jonathan Lethem’s thrilling postmodern essay about influence and loss, “The Beards.” It’s from his 2005 collection The Disappointment Artist. I’ve often taught Lethem’s in conjunction with “Notes of a Native Son,” which is how I first studied them myself, in an MFA seminar at Goucher College taught by Leslie Rubinkowski. Though both essays are very long, they helpfully demonstrate strikingly different approaches to writing about a parent’s death.Lethem’s account of his geeky, art-saturated adolescence occurs during and in the wake of his mother’s early death, from cancer, when he was 14. It’s a heavily segmented essay, with each segment dated according to his mother’s status (stage of illness or length of time dead). His disorientation, devastation, and ongoing sense of loss are mirrored in the essay’s disjointed structure, most obviously by the fact that the segments appear in non-chronological order. His grief from her death is ongoing, ever-present, endless.

As depicted in “The Beards,” Lethem’s intense saturation in cerebral rock music, foreign films, and countless classic and cult novels is awe-inspiring. Along with being a portrait of the sort of obsessions that can forge an artist, Lethem’s art-absorption is inseparable from his point about the particular nature of his loss. His mother, who gave young Jonathan a typewriter shortly before her death, emerges in the writer’s cool, elliptical way as loving and artistic. She was and remains his muse and his subject.

But Lethem’s arts analysis in “The Beards” also forms a hurdle for novice readers. My continuing studies students bounced right off it. “What was that? All that stuff about music?” asked a talented novice writer, a fan of segmentation, who’d stopped reading it early on. Thus I recalled that “The Beards” tends to exhaust and bewilder my undergraduates as well. For one thing, it challenges almost anyone’s own artistic depth. For another, it’s difficult for most readers to absorb stories about art they’re utterly unfamiliar with. I know it’s the teacher’s job to expose students to classics and help them through them. In practice, and partly because of time constraints, I think you must pick your battles.

Imagine my surprise when, after my latest disappointing performance in teaching “The Beards,” I went looking and found the version that the New Yorker originally published, in 2005, as an excerpt from The Disappointment Artist. Wow—way shorter. So far, I haven’t been able to quantify the full difference, but the magazine version includes 10 segments over seven and a half double-column pages while the book’s version features 11 segments over some 24 book-pages. Guess which version I’ll assign to freshmen composition students and novice writers? The other I’ll reserve for more experienced and ambitious readers and writers.

How do you get good at judging wine? You drink lots of wine! How do you develop your taste as a reader? You read a lot! You challenge yourself. But look, everyone starts with training wheels. And sometimes everyone needs to dismount into a warm bath. Even a teacher.

Sunrise near Frederick, Maryland. Easter 2016.]

The post Reading as writers appeared first on Richard Gilbert.