[Orderly & perfect: “Bookshelf #8” by Eli Helman.]

John McPhee’s “Draft No. 4” & my penance for misusing a word.

You cannot cross the narrow bridge of art carrying all its tools in your hands. Some you must leave behind …—Virginia Woolf, “The Narrow Bridge of Art,” Granite and Rainbow

But a writer had better take words. And fair command of them. I’ll never forget the day in high school when my English teacher accused me of plagiarism because of a word. I was 16 or 17 and had shown off by using “belies” in an essay. Since I was disrespectful to him, and acted like a simpering idiot in his class, he had good reason to suspect and dislike me. True to form, I laughed in his face. But that was long before the internet, which has made plagiarism—and catching it—easy. So he couldn’t do much except glare.

I’m sorry Mr. X!

I was just showing off, using a new word I’d learned. Partly I was flattered that he thought I had taken a professional’s work. Wow, though. Really just one word had tipped the balance. Diction does give us away. But I catch plagiarism these days because a student who slams together bald syntax suddenly turns in flowing, clause-laden, prose. Cheaters have the sense to change words they don’t understand.

Teachers’ and writers’ occasional admonitions against thesaurus use have always struck me as odd. They fear a student or rookie is going to use an overblown, polysyllabic word. One he doesn’t understand and that stands out from his mundane diction. I suppose that has happened once or twice. What using the thesaurus does for me, in contrast, is to remind me of old, plain, short words.

Counting syllables and picking the simplest word

Late in the years of working on my book, one day I noticed that I’d begun counting syllables. I’d pick the word, all else being equal, that had fewer. How this happened, I don’t know. It wasn’t as if I had just read an essay advising it. More like years of reading and writing had finally sunk in. In the first draft of my book, there had been plenty of fat words—“moreovers,” “neverthelesses,” and “howevers.” The latter isn’t disgusting but it’s not very colloquial, so there are only a couple left and many buts.

Recently I revisited John McPhee’s fine essay about diction, “Draft No. 4,” in the New Yorker. As I wrote here previously, one Thursday night in April of 2013, I told my wife about my notion of calling my blog The Fourth Draft. At that point I was well into my fifth year of blogging, and was tired of its name, Narrative. Also, my book’s fourth draft was its transforming draft. The only thing was, The Fourth Draft sounded like a minor-league baseball team or a microbrewery.

[John McPhee, master wordsmith.]

Then Friday morning, I sat down with my oatmeal and opened my new

New Yorker to John McPhee’s “Draft No. 4.” So that’s what I renamed my blog. There was more poetry in his arrangement, plus it sounded like a small-batch bourbon.

That was his essay’s legacy to me—I merely noted his practice, in his final draft, of drawing boxes around distinctive adjectives, nouns, and verbs. Then he goes through the dictionary, and then the thesaurus, confirming and checking options. In the tradition, he’s kind of weird about the thesaurus, though.

I wish I’d had the sense to adopt his word-boxing practice then. Probably there was time to do it for my book’s final draft—at least the book was a full year from publication then. My thesaurus work had involved mostly newer work in the book. I was hit or miss on words that I had written so many years before that they were almost invisible to me. Which of course is an implicit point of McPhee’s boxes.

I pick the wrong word: on the mortification of misuse

After Shepherd: A Memoir came out, a reader named Sarah Buchanan mentioned in a nice review for Goodreads that I had misused a word. Though she didn’t name the word, I knew instantly which one it was. So I must’ve known at some level that I had misused it! This is the most mortifying experience I have had as an author, which is saying something, given my babbling at one book event.

[“The Gravel Page” is collected here.]

Using the wrong word feels more undermining to my authority as an author than any other error I can think of. Even grammatical errors seem less damning because they can be chalked up to haste. Authors are in the larger sense poets, and what poet uses the wrong word? They don’t because they’re talented but also because they look up words. It’s part of a writer’s craft, which sets professionals apart from duffers. I can barely stand to think about my error. Humiliating.

Totally.But amazingly, a few weeks ago I got the chance to fix it. What happened is that Barnes and Noble Booksellers placed an order for 266 copies. That brings the stock of the first printing low enough that, given anticipated reorders, my publisher is planning a reprint. And my editor has kindly let me correct my text for the new run.

Now you probably think it’s time for me to reveal the word. You have got to be kidding. As we used to say as kids, Wild horses couldn’t drag it out of me. I’m a fairly open person, and I reveal things in print that give some friends and loved ones the vapors, but of that I’m too ashamed. Read my book, and if you can find it, let me know and I’ll give you credit here. I may even reveal the word.

But don’t count on it.

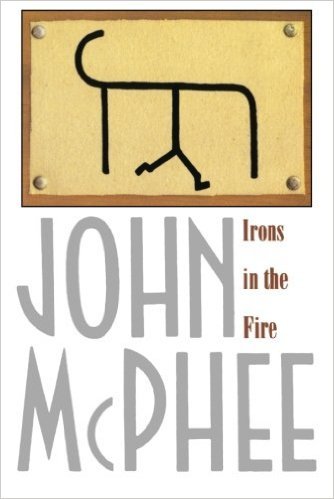

Read or download John McPhee’s famous “The Gravel Page Essay”Speaking of John McPhee, you can read or download his essay about geological crime forensics, “The Gravel Page,” collected in his 1998 book Irons in the Fire. The New Yorker, where the essay first appeared, makes it available only to subscribers, but someone from North Dakota State University has uploaded a copy from the book, which of course we all should buy.

The post Wrong word! appeared first on Richard Gilbert.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Ha! Now I feel embarrassed because I cannot recall the specific word you are referring to. I often do notice a misuse of a word in a book but choose not to hold it against the author. I can't imagine the courage to mention it to you, my admiration is with that brave soul. A very thoughtful blog. Now I am going to read her review!

Ha! Now I feel embarrassed because I cannot recall the specific word you are referring to. I often do notice a misuse of a word in a book but choose not to hold it against the author. I can't imagine the courage to mention it to you, my admiration is with that brave soul. A very thoughtful blog. Now I am going to read her review!