Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 8

March 17, 2023

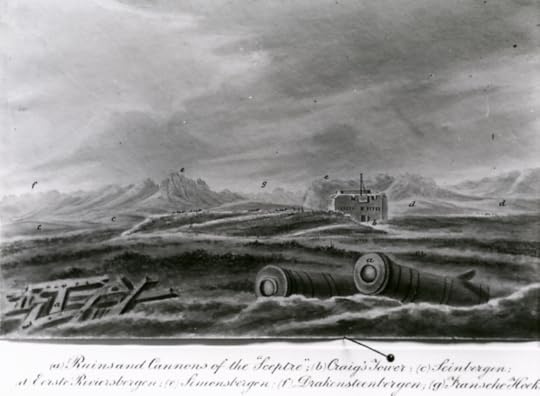

Surviving HMS Namur’s sinking, 1749

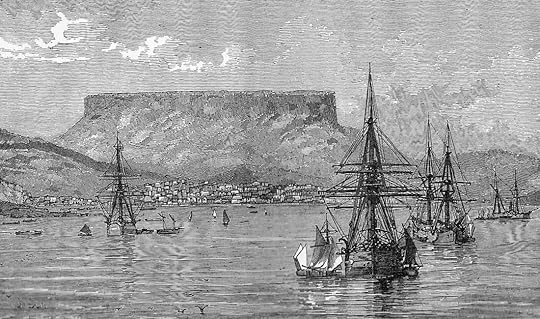

Two conflicts – the War of Jenkin’s Ear and the War of Austrian Succession – merged into one and lasted from 1739 to 1749. The various international alliances involved were complex, but for Britain the main enemies were to be – as usual! – France and Spain. The Royal Navy, by now well established as master of naval professionalism, fought gruelling campaigns in the Americas and in the Indian Ocean, as well as in European waters. This war saw the beginning of conflict between Britain and France for control of India, and in 1747, under Admiral Edward Boscawen (1711 – 1761) a large military and naval expedition was sent to capture Pondicherry, the most important French holding there. The effort was unsuccessful and further operations were brought to an end after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended hostilities in 1748. Boscawen had not taken Pondicherry but he had secured a valuable British base just to its south at Fort St. David, Cuddalore, some ninety miles south of Madras (now called Chennai) on India’s eastern coast. It was here, after the end of the war, that Boscawen’s flagship, the 74-gun second-rate HMS Namur, was to be wrecked with heavy loss of life, together with another vessel, HMS Pembroke.

Two conflicts – the War of Jenkin’s Ear and the War of Austrian Succession – merged into one and lasted from 1739 to 1749. The various international alliances involved were complex, but for Britain the main enemies were to be – as usual! – France and Spain. The Royal Navy, by now well established as master of naval professionalism, fought gruelling campaigns in the Americas and in the Indian Ocean, as well as in European waters. This war saw the beginning of conflict between Britain and France for control of India, and in 1747, under Admiral Edward Boscawen (1711 – 1761) a large military and naval expedition was sent to capture Pondicherry, the most important French holding there. The effort was unsuccessful and further operations were brought to an end after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended hostilities in 1748. Boscawen had not taken Pondicherry but he had secured a valuable British base just to its south at Fort St. David, Cuddalore, some ninety miles south of Madras (now called Chennai) on India’s eastern coast. It was here, after the end of the war, that Boscawen’s flagship, the 74-gun second-rate HMS Namur, was to be wrecked with heavy loss of life, together with another vessel, HMS Pembroke.

The Battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747, a victory in which Boscawen played a leading role – by Samuel Scott (1702-1772)

The Battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747, a victory in which Boscawen played a leading role – by Samuel Scott (1702-1772)

When reading of the Age of Fighting Sail one is often impressed by how often wooden vessels could survive brutal bombardments as long as the damage was sustained only above the waterline. Wrecking on shoals or on rocky shores was however usually fatal and frequently involved total break-up. What brings the wreck of HMS Namur to life however is a first-hand account, a letter to a friend, by one of the survivors, a James Alms, which is quoted from (in italics) later in this article. Alms’ role on HMS Namur is not clear but one assumes that he might have been a midshipman, as he was immediately thereafter appointed as a lieutenant on the sixth-rate post-ship HMS Syren, from which he sent the letter.

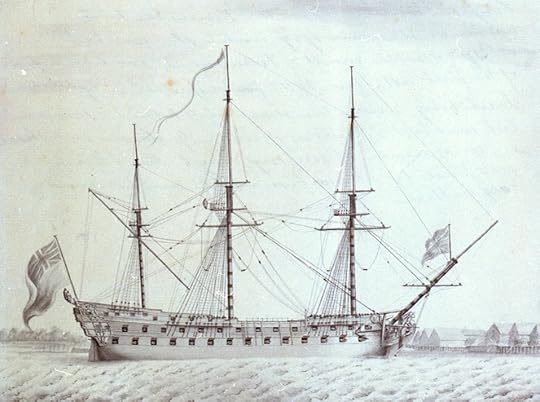

HMS Invincible

a “74” launched for the French Navy in 1744 and captured 1747. HMS Namur would have looked generally similar

HMS Invincible

a “74” launched for the French Navy in 1744 and captured 1747. HMS Namur would have looked generally similar

HMS Namur and other vessels of the squadron were moored off Fort St. David on April 12th 1749 when a strong wind began to blow from the north-north-west. By the following day this had grown into a violent storm. Admiral Boscawen, together with HMS Namur’s Captain Marshall and other officers, was ashore at the time. He did not return to his flagship, though Marshall did.

James Alms takes up the story on April 13th:

“In the morning it blew fresh, wind north-east. At noon we veered away to a half cable on the small bower. From one to four o’clock we were employed in setting up the lower rigging. Hard gales and squally, with a very great sea. At six o’clock the ship rode very well, but half an hour afterwards had four feet of water in her hold.”

Given the circumstances, the decision to put out to sea was a pragmatic one:

“We immediately cut the small bower cable, and stood to sea under our courses. Our mate, who cut the cable, was up to his waist in water at the bitts.”

The situation was still deteriorating however and extreme measures to lighten ship were now required. One is impressed that such brutal labour as ditching guns and cutting away masts could be undertaken in such conditions. That it was managed at all speaks highly of the discipline and professionalism of the crew:

“At half-past seven we had six feet of water in the hold, when we hauled up our courses and heaved overboard most of our upper-deck and all the quarter-deck guns to the leeward. By three-quarters after eight the water was up to our orlop gratings, and there was a great quantity between decks so that the ship was water logged; when we cut away all the masts, by which she righted. At the same time we manned the pumps and baled, and soon perceived that we gained upon the ship, which put us in great spirits. A little after nine we sounded, and found ourselves in nine fathoms of water: the master called, ‘Cut away the sheet-anchor!’ which was done immediately, and we veered away to a little better than a cable; but, before the ship came head to the sea, she parted at the chesstree (i.e. the hull’s structure at the bow). By this time it blew a hurricane. It is easier to conceive than to describe what a dismal, melancholy scene now presented itself—the shrieking cries, lamentations, ravings, despair, of above five hundred poor wretches verging on the brink of eternity!”

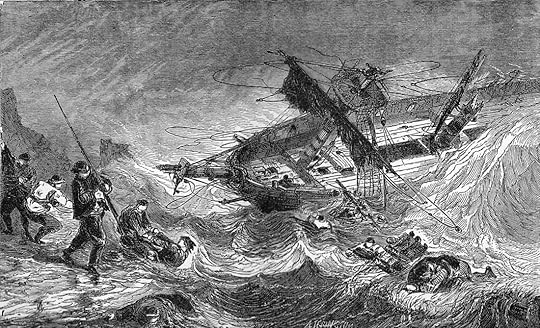

The horror of shipwreck has seldom been better conveyed than by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900)

The horror of shipwreck has seldom been better conveyed than by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900)

James Alms, like others, decided that his only hope was to abandon ship:

“I had, however, presence of mind to consider that the Almighty was at the same time all-merciful, and experienced consolation in the reflection that I had ever put my whole trust in Him. In a short prayer I then implored His protection, and jumped overboard. The water, at that time, was up to the gratings of the poop, from which I leaped. The first thing I grappled was a capstan-bar, by means of which, in company with seven more, I got to the davit; but, in less than an hour, I had the melancholy experience of seeing them all washed away, and finding myself upon it alone, and almost exhausted.”

After some two hours in the water “to my unspeakable joy, I saw a large raft with a great many men driving towards me. When it came near I quitted the davit, and with great difficulty swam to the raft, upon which I got, with the assistance of one of our quarter-gunners. The raft proved to be the Namur’s booms. As soon as we were able we lashed the booms close together, fastened a plank across them, and by these means made a good catamaran.” (One wonders if this is one of the earliest uses in English of the word ‘catamaran’.) “It was by this time one o’clock in the morning; soon afterwards the seas became so mountainous that they turned our machine upside down, but providentially, with the loss of only one man.”

This

Aivazovsky work, showing survivors escaping from a doomed ship, gives an idea of what HMS Namur’s crew faced

This

Aivazovsky work, showing survivors escaping from a doomed ship, gives an idea of what HMS Namur’s crew faced

The raft was finally driven ashore at the Dutch trading base at Porto Novo (Modern Parangippettai) about fourteen miles south of Fort Dt. David: “About four, we struck ground with the booms, and, in a very short time, all the survivors reached the shore. After having returned thanks to God for His almost miraculous goodness towards us, we took each other by the hand, for it was not yet day, and still trusting to the Divine Providence for protection, we walked forward in search of some place to shelter ourselves from the inclemency of the weather; for the spot where we landed offered nothing but sand. When we had walked about for a whole hour, but to no manner of purpose, we returned to the place where we had left our catamaran, and to our no small uneasiness found that it was gone. Daylight appearing, we found ourselves on a sandy bank, a little to the southward of Porto Novo, from which we were divided by a river that we were under the necessity of fording, soon after which we arrived at the Dutch settlement where we were received with much hospitality. From our first landing till our arrival at Porto Novo we lost four of our company, two at the place where we were driven ashore, and two in crossing the river.”

The Dutch commander proved helpful and “was so obliging as to accommodate me with clothes, a horse and a guide to carry me to Fort St. David, where I arrived about noon the following day, and immediately waited on the admiral (Boscawen), who received me very kindly indeed; but so excessive was the concern of that great and good man for the loss of so many poor souls, that he could not find utterance for those questions he appeared desirous of asking me concerning the particulars of our disaster.”

James Alms concluded his accounting by noting that only twenty-three men were saved, Captain Marshall among them, twenty of whom came ashore on the booms. Some 520 others died in this tragedy. Now, across almost three centuries, Alm’s unvarnished account still had the power to move.

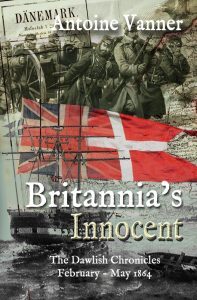

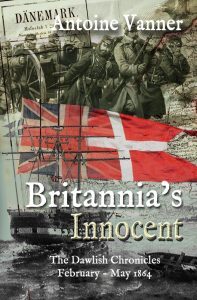

Start the 11-volume (so far!) Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the earliest chronologically:Britannia’s Innocent 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish volunteers to support Denmark. He is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – not to mention divided loyalties . . .

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting. In Kindle and paperback. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge. Click on image for details of each.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting. In Kindle and paperback. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge. Click on image for details of each.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Surviving HMS Namur’s sinking, 1749 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 3, 2023

Agony by ice: HMS Proserpine, 1799 Part 2

With a major portion of his crew and passengers having reached safety in Cuxhaven – albeit at the cost of a fearful trek across fissured ice – Captain Wallis remained on Neuwerk Island in the Elbe estuary with the remainder of his crew. Food was running short there and HMS Proserpine, abandoned as she was in the ice, but visible from Neuwerk, might well be still afloat. Supplies were to be had there if she could be reached. On 8th February Wallis accordingly sent a small group, led by the ship’s master, a Mr. Anthony, to fetch whatever they could from the wreck and bring it back to the island

How HMS Proserpine may have looked when Anthony’s party found it (Painting of a wreck in the Arctic by E. Robins, active 1882-1902)

How HMS Proserpine may have looked when Anthony’s party found it (Painting of a wreck in the Arctic by E. Robins, active 1882-1902)

Anthony’s party reached the ship with much difficulty – another nightmare six-mile plod over broken and stacked ice – and found her lying on her beam-ends, with seven or eight feet of water in her hold. With many of her timbers smashed, HMS Proserpine’s hull seemed held together only by the pressure of the surrounding ice. Anthony and his men managed to get back to the island and, based on what he was told, Captain Wallis thought it inadvisable to risk a second visit. Two days later however he changed his mind. Mr. Anthony set out again, accompanied by the surgeon, the boatswain, one midshipman, and two seamen. A day and a night passed and a violent storm arose. When it finally cleared, Wallis looked towards the wreck – and did not find it.

As HMS Proserpine could have looked

The outcome had proved however better than first feared. After reaching the wreck, Anthony’s group had plunged into the task of salvaging provisions. While they were busy a wide channel opened through the ice, cutting them off from Neuwerk Island and leaving them no option but to remain on board. During the night that followed the wind, previously from the south-east, now shifted to the north-west and built up to storm level. This gale, together with a rising tide, lifted the wreck off the shoal beneath her and tore away much of the belt of ice that surrounded her. By morning she was drifting seawards (the wind appears to have shifted again).

The fear was now that the remaining ice around the ship would be ripped free, leaving her to break up. There was no hope of grounding again in this area – sounding indicated eleven fathoms, almost seventy feet, below the ice. Even in these extremities, every effort for saving the ship was tried. Guns were fired to attract any other vessel in the vicinity, the pumps were manned and almost all the remaining guns were dumped overboard to lighten the vessel. The frigate’s cutter, a large and heavy boat, was still on board and they rigged tackles for lowering it. In reading of these brutal labours it should be borne in mind that these half-dozen men had been exposed to extreme cold, privation and exhaustion for almost two weeks. At this stage the only factor in their favour was that they had access to sufficient supplies.

At last, on the morning of 12th February, land was sighted. Distress signals were hoisted, and guns fired, but no assistance came. Soon afterwards HMS Proserpine grounded again, this time a mile and a half from the East Friesian island of island of Baltrum. She had drifted some forty miles since her first running aground.

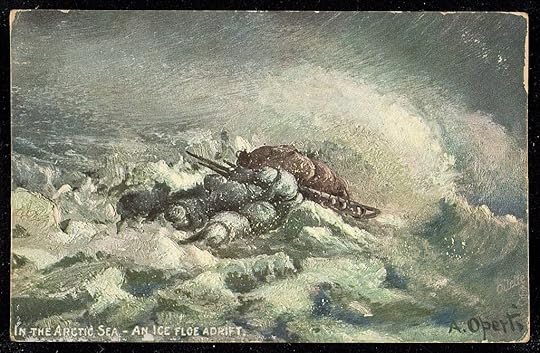

Wreckage adrift on ice – a 19th Century visualisation. It conveys the full horror of the situation.

Attempts to launch the cutter were frustrated by more drift ice but they succeeded the following day. Due to the ice piled up on the island’s beaches it was only possible to get ashore by abandoning the boat and struggling across the blocks. They gained the shore by leaping from block to block. The islanders proved hospitable but they regarded the wreck as valid salvage and were to strip it of anything moveable and valuable. They did however recover the cutter and turned it over to Anthony. Several days later he and his party set out to sail to Cuxhaven in improved weather. They arrived on 22nd February. Given up as lost, their appearance caused amazement to the HMS Proserpine’s other survivors, including Captain Wallis and the men who had remained with him at Neuwerk, and who arrived themselves shortly afterwards. They returned to Britain on mail packets while the diplomat, Thomas Grenville, continued on to Berlin with his party.

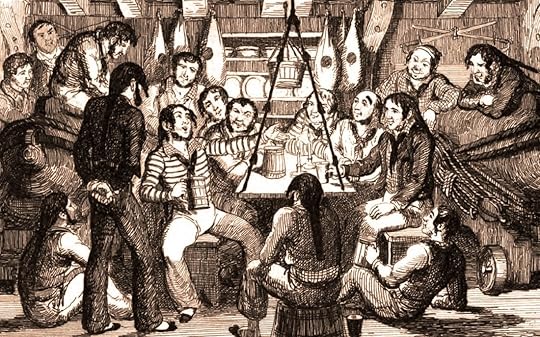

The Royal Navy seamen of the Age of Fighting Sail – rough, coarse and unlettered, but courageous, inventive and invincible in adversity

The Royal Navy seamen of the Age of Fighting Sail – rough, coarse and unlettered, but courageous, inventive and invincible in adversity

The most remarkable aspects of HMS Proserpine’s ordeal were the dogged fortitude of officers and crew alike, their inventiveness in the face of one setback after another and their ability to endure privations that by any rational expectation would have been enough to finish most of them. The death toll – sixteen seamen and a woman and her baby – was indeed tragic, but considering that there 187 people on board the frigate it could have been much higher. A Victorian chronicler remarked that “It speaks highly for the discipline and self-control of English seamen, that through the whole course of their adventures not one was heard to complain, not one was known to disobey an order. Their courage never quailed, their resolution never gave way and it was to their serene fortitude and persevering energy that they owed, under Divine Providence, their deliverance from so many perils.”

Sententious though it may sound today, it was a fair evaluation.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and with more still to come!Click on the image below for details of the individual booksClick Here or on the image above for more information on the individual books.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or Smartphone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. It will update you on new books and provide other free stories at intervals.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!FacebookTwitterReddit.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Agony by ice: HMS Proserpine, 1799 Part 2 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 25, 2023

HMS Proserpine’s agony by ice, 1799

HMS Proserpine was a 28-gun Enterprise-class frigate that entered Royal Navy service in 1777. Her career up to 1799 was worthy but unspectacular. In January 1799 when commanded by Captain James Wallis, she was tasked with carrying the diplomat Thomas Grenville (1755 –1846) on the first leg of his journey to the British Embassy at Berlin, the Prussian capital. This meant dropping him at Cuxhaven, on the west side of the vast estuary of the River Elbe. In that era, before dredged channels had arrived, sandbanks and shoals made navigation in the area difficult and necessitated the services of an experienced pilot.

A classic image of a British frigate of the era by the masterful Thomas Luny (1759 – 1837 )

HMS Proserpine sailed from Yarmouth on 28th January 1799, a mail packet, the Prince of Wales, sailing with her. They arrived off the island of Heligoland – then held and fortified by Britain – two days later and HMS Proserpine took a pilot on board there. A buoy, “the Red Buoy” marked the entrance to the navigation channel, and there both vessels anchored for the night. The other buoys that marked the approaches to the Elbe estuary had been removed to hinder access by hostile forces. Captain Wallis expressed doubts about proceeding further. The pilot was confident however that he would be capable of reaching Cuxhaven as long as the effort was made between half-ebb and half-flood tide, as the lowered water levels would expose sandbanks and show the necessary access channel. He would be further assisted by sight of known landmarks. Wallis yielded and the next morning HMS Proseprine began her passage up the Elbe, proceeded by the Prince of Wales.

All went well until late afternoon, when light was fading. Fog descended, snow began to fall and the pilot could not see his landmarks. HMS Proseprine anchored. In late evening however a strong gale swept in from the east, accompanied by heavy snow. The tide was soon following the direction of the wind and huge masses of ice began to strike the ship. Great effort was needed to fend off the ice from the anchor cables and HMS Proseprine managed to hold her ground.

Daylight revealed floating ice stretching far up the river and also that the Prince of Wales had grounded. The water was still clear seawards, so Wallis decided to retreat and to land his diplomat passenger at some other, safer, location. With no other canvas than her fore-topmast stay-sail, HMS Proserpine ran before a strong wind. All danger was supposed to be past, when, about half-past nine she struck with immense violence on the Scharhörn, a large sandbank some six miles north-west of the tiny but inhabited island of Neuwerk. Soundings indicted only ten feet of water. Boats were launched to carry out an anchor so that the vessel could be winched off but the arrival of more drifting ice prevented it.

“A frigate in a swell” by Samuel Atkins (active 1787 -1808)

Captain Wallis then ordered out the boats to carry an anchor to some convenient point of the shore; but the shoal-ice returned so rapidly that this could not be done. He ordered buttressing along each side with strong timbers set against the seabed to preen the hull heeling over. (One is impressed by the ingenuity and resourcefulness of this man in such a situation). It worked – when the tide fell, the frigate remained upright and hope rose that she might be floated off with the next rising tide. When this came however it brought huge masses of ice, enough to tear away the buttressing, strip the copper off the starboard quarter, and smash the rudder. Captain Wallis still hoped to drift off at high tide and ordered lightening by casting guns and supplies overboard. A Victorian writer was later to comment with admiration on the fact that though casks of wines and spirits were stove in, not a single case of intoxication occurred. This probably does as much credit to Wallis and his officers as much as to the men. HMS Proseprine was clearly a well-disciplined ship with high crew morale, as later events were to show.

Despite the lightening, the frigate did not lift clear at high-water. By late evening, when the tide should have been flooding, the south- easterly gale was so strong as to drive the waters back and leave her in even shallower water than when she had first struck bottom. The pounding by the ice continued and it was clearly only a matter of time before the vessel broke up. Darkness and snow enveloped her and the decks were so icy that it was all but impossible to retain a foothold. By morning the situation was worse still for the wind was yet higher. Drifting ice had reached as high as the cabin-windows and was pounding so hard that the ship was soon likely disintegrate.

[image error]

Destruction by ice – remains of ship in foreground. An illustration of how ice blocks can build up. A painting by Kasper David Friedrich (1774 – 1840), inspired by the loss of one of William Edward Parry’s ships during his North West Passage expedition in 1825

Thomas Grenville, the diplomat, now suggested that the only hope of escape was to cross the ice to Neuwerk Island. Captain Wallis agreed reluctantly. He divided the crew into four companies, each commanded by an officer. They carried ropes and planks for bridging chasms in the ice and each man took his own provisions with him. By three in the afternoon, the last party departed, led by Wallis and a Lieutenant Ridley of the marines. They had to head into the wind, faces stung with flying ice particles, eyes blinded by driving snow. Only availability of a pocket compass kept them on track. At some points they had to wade waist-deep through snow drifts, at others through deep pools of water, and at others still had to clamber over ice blocks. This appalling trek is a reminder of how much the climate of Northern Europe has changed since then – indeed seventeen years later would come “The Year Without a Summer” that would cause so much hardship.

The experience must have been worst of all for the two women in the party, both wives of seamen. One had actually given birth to a still-born child on HMS Proserpine’s first day out from Yarmouth and was still recovering. The other woman, described as “strong and healthy, and accustomed to a seafaring life” had a nine-months old baby with her. She and her infant died of exposure but the other woman survived, reaching Neuwerk Island in darkness. The resident community was tiny but it took the survivors in and did what it could for them.

The nightmare trek across the ice from HMS Proserpine to Neuwerk Island. Note the lady carrying the baby and the other lady following.

The nightmare trek across the ice from HMS Proserpine to Neuwerk Island. Note the lady carrying the baby and the other lady following.

Despite the horrors of the retreat across the ice, a roll call confirmed that of 187 people who had been onboard the frigate all but sixteen seamen and the woman with the baby had reached the island. Many of the survivors suffered severely from frostbite but all of them ultimately recovered. The blizzard continued for another four days and availability of food and clothing was now a problem – the scanty provisions brought from the frigate were running out. Neuwerk Island, even today, has a population of some thirty – it cannot have been much greater in 1799 and the arrival of almost three hundred survivors must have overwhelmed the community’s food resources. The solution was to get as many of the survivors as possible off the island by trekking across the ice to Cuxhaven. Some islanders acted as guides and Grenville was one of the party. Another nightmare journey followed, often wading through icy water, but in some twelve hours they managed to reach Cuxhaven without loss.

Captain Wallis, with a party of officers and men, had remained at Neuwerk, in the hope of saving a portion of the ship’s stores and a new chapter in this epic saga of survival was about to begin.

We’ll learn about that in the second part of this article, due next week.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and with more still to come!Click on the image below for details of the individual booksClick Here or on the image above for more information on the individual books.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or Smartphone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. It will update you on new books and provide other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Proserpine’s agony by ice, 1799 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 19, 2023

Loss of HMS Wasp 1884

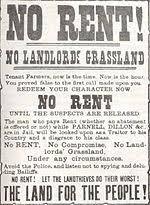

The Wreck of HMS Wasp, 1884An accidental victim of Ireland’s “Land War”

The Wreck of HMS Wasp, 1884An accidental victim of Ireland’s “Land War”Though it is likely that many in her crew disliked the task assigned them it is fair to say that the mission on which HMS Wasp was engaged at the time of her loss was one of the most inglorious ever undertaken by the Royal Navy.

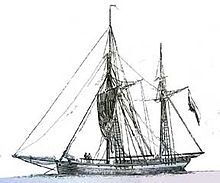

HMS Wasp under sail and steam

Built in the 1880-82 period, HMS Wasp was one of the 11-strong Banterer Class of gunboats. They were of composite construction, based on an iron frame but planked with wood, thus facilitating fitting of anti-fouling coppering. This was an important, if not to say essential, feature for ships which were to see considerable colonial and tropical service. They were 125 feet long, and displaced 465 tons. A single-screw 360 HP compound steam engine gave a top speed of a mere 9.5 knots but for the sort of service such vessels were intended endurance was a more important consideration than speed. A barquentine rig was carried on three masts to supplement the engine, or indeed to replace it on long voyages to conserve coal. For their size these vessels carried a heavy armament – two 6-inch 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifles, supplemented by two 4-inch breech-loaders as well as small-calibre Maxims, Gardners or Gatlings. The unsophisticated 6-inch weapons, were effective enough for shore bombardment and the vessel’s small size and sailing ability made them useful for colonial duties, for which armour was not required. The crew consisted of 60 officers and men. This is an indication of just how many men were employed in the Navy at this time – this single class of small gunboats alone required almost 700 men to crew them.

HMS Wasp – looking pristine, probably soon after commissioning

After commissioning, HMS Wasp was based at based in Queenstown (now Cobh) in County Cork in the south of Ireland, then still under British rule. Her duties appear to have fishery and lighthouse inspections or other official duties around the entire Irish coast. These were difficult and bitter years in Ireland, where the long and often violent social unrest known as the “Land War” was raging. Small tenant farmers were, at last, confronting the landlords – almost exclusively Anglo-Irish and different from them in religion and political affiliation – on issues of tenure and fair rent and were demanding distribution of land to them. Particular bitterness was felt towards absentee landlords who lived well elsewhere on the rents and who ploughed little back into the betterment of local society. Though the overall poverty of the country was not as extreme as during the Great Famine period of the 1840s, life was still miserably deprived for many in the rural population. A poor harvest could mean inability to pay rent and such failure frequently resulted in eviction of entire families, followed by demolition by battering ram of the dwelling to prevent its further occupation. Such evictions saw deployment of armed police to protect the bailiffs and demolition gangs – photographs of such occasions are heartrending in their pathos. Feelings ran high and there was a high level of violence on both sides. It was in this period that the “Boycott” weapon came to have its present meaning since the process was named from action used against a Captain Boycott, the agent of a particularly unpopular landlord.

After commissioning, HMS Wasp was based at based in Queenstown (now Cobh) in County Cork in the south of Ireland, then still under British rule. Her duties appear to have fishery and lighthouse inspections or other official duties around the entire Irish coast. These were difficult and bitter years in Ireland, where the long and often violent social unrest known as the “Land War” was raging. Small tenant farmers were, at last, confronting the landlords – almost exclusively Anglo-Irish and different from them in religion and political affiliation – on issues of tenure and fair rent and were demanding distribution of land to them. Particular bitterness was felt towards absentee landlords who lived well elsewhere on the rents and who ploughed little back into the betterment of local society. Though the overall poverty of the country was not as extreme as during the Great Famine period of the 1840s, life was still miserably deprived for many in the rural population. A poor harvest could mean inability to pay rent and such failure frequently resulted in eviction of entire families, followed by demolition by battering ram of the dwelling to prevent its further occupation. Such evictions saw deployment of armed police to protect the bailiffs and demolition gangs – photographs of such occasions are heartrending in their pathos. Feelings ran high and there was a high level of violence on both sides. It was in this period that the “Boycott” weapon came to have its present meaning since the process was named from action used against a Captain Boycott, the agent of a particularly unpopular landlord.

Demolition of tenant’s house by battering ram following eviction in the 1880s to prevent reoccupation. (Note that the tenants attempted to defend themselves by stuffing gorse in the windows as a primitive alternative to barbed wire)

A landlord or his agent overseeing eviction with police support. Note the lady on the horse to the right viewing the spectacle. Scenes like this sowed seeds of bitterness that ultimately led to independence.

Poverty was possibly at its worst on the small islands off the North and West Coasts. The most extreme case was perhaps Inishtrahull, a tiny speck which is the most northerly island of all. all. Six miles from the mainland, it is the most northerly point in the Irish Republic. Though uninhabited now, the last residents having left in 1929, the island supported several families in the 1880s as well as a lighthouse.

Inishtrahull – The Irish Republic’s most northerly point. (Photograph by author Kevin Dwyer http://blog.discoverireland.com/2010/09/the-joys-of-aerial-photography-over-ireland/ )

The battering ram’s work: a house left uninhabitable post-eviction. For many of those cast on the roadside, the best option would be to go to the United States if they could raise the money.

Difficult as life on Inishtrahull may have been, rent still had to be paid for the pitiful plots of land, basic humanity not always being a characteristic of the landlord class. In September 1884 three families on Inishtrahull were unable – or perhaps unwilling – to pay their rents and an example had to be made of them. HMS Wasp, then at Westport on the West Coast, and under the command of the 39-year old Lieutenant J. D. Nicholls, was accordingly ordered to Moville, the mainland village closest to the island. Here she was to take on board the bailiffs, police and other officials who would carry out the evictions. One can well imagine distaste among many of the gunboat’s crew for this task, but orders were orders.

In the early hours of September 22nd HMS Wasp was following a course that took her between the northwest coast of Donegal and the rocky coast of Tory Island, nine miles offshore. The vessel was under sail only, and the boiler was not fired, so that the advantage of improved maneuverability which steam would provide# was not available. Given this fact it was surprising that HMS Wasp would have followed the course that took her to the east of Tory Island, between it and the mainland, rather than gaining greater sea room had she sailed west of it. It also appears that Nicholls and other officers may have been sleeping.

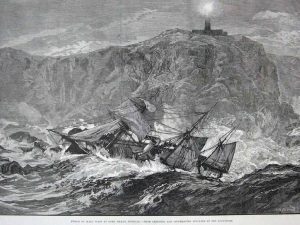

HMS Wasp on the rocks beneath the Tory Island lighthouse

HMS Wasp on the rocks beneath the Tory Island lighthouse

At 0345 the Wasp ran onto rocks directly under the Tory lighthouse. She sank within 30 minutes with the loss of fifty of the crew, leaving only six survivors. Only the mastheads were left protruding from the water and it was to these that the survivors clung. They were rescued by the islanders and sheltered until they could be picked up four days later by another ship assigned to Irish duty, HMS Valiant, which took them to the mainland. Valiant was a large Hector-class armoured frigate of 7000 tons, this class being smaller versions of HMS Warrior, which can be seen in Portsmouth today. A monument was erected in the churchyard of St. Ann’s, Church of Ireland Church, Killult, on the mainland coast opposite Tory Island, where some of the sailors are buried.

A Royal Navy enquiry subsequently found that HMS Wasp was lost “in consequence of the want of due care and attention…” but no one person was singled out for blame, possibly in view of the deaths of the officers and the distress it would inflict on their families. Apart from the questions raised about what was happening on board HMS Wasp, much debate since has focused on whether the Tory light was on or off before the vessel struck the rocks. What is known is that the light was certainly on after the collision. However, the question remains – was the light on when HMS Wasp was nearing Tory? Did animosity towards the British rulers of Ireland at the time and the duties in which HMS Wasp was sometimes involved cause the light to have been extinguished deliberately when the gunboat was passing through the channel between the island and the mainland?

Another less likely explanation, but one which became popular in the area was that HMS Wasp was the victim of a curse laid on it via “Cursing Stones” on the island. These are Neolithic remains involving individual stones resting in a larger cup-shaped one. Of all the speculative explanations of the tragedy, this is the one that can most easily be ruled out!

The latest Dawlish Chronicles novel has been published:Britannia’s Rule 1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

But Dawlish’s contest with the volcano is just the prelude to a longer association with the island. Its sovereignty is split – a British Crown Colony in the west, and in the east an independent republic established seven decades earlier by self-emancipated slaves. When wrenched from France through war, both seemed glittering economic prizes. Now they are impoverished backwaters where resentment seethes and old grudges fester. For many, the existence of a ‘black republic’ is resented, an affront to be excised. In France, a man of limitless ambition, backed by powerful interests, sees the turmoil as an opportunity that could bring him to absolute power. And, if he succeeds, perhaps trigger war in Europe on a scale unseen since the fall of Napoleon.

Through this maelstrom, Nicholas Dawlish must navigate a skillful course. Political concerns complicate challenges that can only be resolved by ruthless guile and calculated use of force. Lacking direct support from the Royal Navy, Dawlish must fight some of the most vicious battles of his career with inadequate resources and unlikely – and unreliable – allies.

Available in Paperback and Kindle (also readable on smartphones and tablets via Kindle App).Kindle Unlimited Subscribers can read it, or any of ten other Dawlish Chronicles, at no extra cost.For more details and for ordering, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au For amazon.caThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and with more still to come!Click on the image below for details of the individual booksSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or Smartphone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. It will update you on new books and provide other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Loss of HMS Wasp 1884 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 4, 2023

HMS Phaeton and Beaufort’s ruse, 1795

HMS Phaeton’s ruse to escape annihilation: 1795

HMS Phaeton’s ruse to escape annihilation: 1795

Cornwallis

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars saw very large numbers of battles at sea between small numbers of ships, but few in which entire squadrons engaged and yet fewer fleet actions on the scale of the Nile, Camperdown or Trafalgar. On one occasion however a medium-sized Royal Navy squadron escaped from a confrontation which, due to the disparity of forces, could have ended in annihilation. That it did not reflected the cool head and tactical mastery of the British commander, Admiral Lord William Cornwallis (1744 – 1819).

Cornwallis had come to prominence in 1782, in the four-day Battle of the Saintes, as captain of the “74” ship-of-the-line Canada. He had already engaged, and defeated, a similarly sized French ship, the Hector, when he saw the opportunity to close with the enemy flagship, the massive 104-gun Ville de Paris. Despite the disparity in size, Cornwallis continued his attack for two hours and though the larger vessel’s position proved to be hopeless, the French Admiral de Grasse (1723 –1788) saw it as a point of honour not to strike his flag to anybody but an enemy admiral. He only surrendered when Admiral Sir Samuel Hood (1724-1816) came up in the Barfleur, by which stage only de Grasse himself and two other men were alive and unwounded on the upper deck. He stated after the battle that Cornwallis’s Canada had done him more harm than all the rest of the Royal Navy force together.

Battle of the Saintes, 1782 – fleet action in which Cornwallis came to prominence. Artist: Thomas Mitchell (1735-1790)

Battle of the Saintes, 1782 – fleet action in which Cornwallis came to prominence. Artist: Thomas Mitchell (1735-1790)

On 7th June 1795 Cornwallis, in his flagship Royal Sovereign, was cruising on blockade duty off Belle Isle, on the southern coast of Brittany, with five “sail-of-the-line” and two frigates. A French convoy of merchantmen under escort of three ships-of-the-line and six frigates. In the subsequent action, in which the French escorts beat an ignominious retreat, eight merchantmen were captured. Cornwallis remained on station thereafter and just over a week later, on 16th June, one of his frigates signalled sighting of the French fleet – a huge force consisting of thirteen sail-of-the-line, several frigates, two brigs and a cutter. Retreat was now the better part of valour and Cornwallis decided – correctly – to decline combat. The wind at first falling and afterwards coming round to the north, the enemy’s ships were enabled to get to windward, and the next morning by daylight – in calm conditions – they were seen mooring on both quarters of the British squadron. Cornwallis’s force was now at risk of being the meat in the sandwich.

During the preceding day and through the night Cornwallis had led the retreating ships in the Royal Sovereign, so as to be able to take advantage of any favourable opportunity that might present itself in the night for altering course and escaping unseen by the enemy. With daylight however he changed his disposition, ordering his two slowest-sailing ships, the Brunswick and the Bellerophon, to lead, and the more nimble Mars and Triumph to form the rear. He himself, in Royal Sovereign, formed a connecting link, ready to come to the assistance of any of his squadron that might need support. It was now in the power of the French admiral to engage closely, and at about nine in the morning, a line-of-battle ship and a frigate opened fire on Mars.

HMS Mars’ even greater moment of glory came in 1798 when she engaged the French Hercule in a rare single-ship action between two ships-of-the-line. Artist: John Christain Schetky (1778-1874)

From this time an almost constant cannonade was kept up, the French ships firing at a distance as they came up – and making no attempt to close and board – and Mars, Triumph and Royal Sovereign returning fire, thereby protecting the slow-sailing Brunswick and Bellerophon. These latter two vessels were now making every effort to increase speed, lightening themselves by cutting away their anchors and boats, throwing some of their ballast overboard and crowding on all sail. This inconclusive chase continued through the day and into the afternoon. Only then did the enemy close upon the rear ship, the Mars. Four of the French ships of the line bore down on her. Had they concentrated their fire and laid themselves alongside, the outcome would have been fatal for her. At this critical juncture, a ruse already underway was to change the situation completely.

In the early morning, Cornwallis had called by signal for a boat from the frigate HMS Phaeton. The young officer who came across to get instructions to bring back to his captain would later be Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort (1774 –1857), creator of the Beaufort Scale for indicating wind force. He was met on Royal Sovereign’s deck by Cornwallis, who told him: “Stop, sir; listen: go back immediately and tell your captain to go ahead of the squadron a long way, and, when far enough off, to make the signals for seeing first one or two strange sail, then more, and then a fleet; in short, to humbug those fellows astern. He will understand me. Go.”

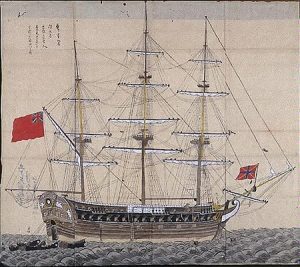

HMS Phaeton – by a Japanese artist – when she was at Nagasaki in 1808 waiting to ambush Dutch traders. (A long story – worthy of another blog article!)

HMS Phaeton – by a Japanese artist – when she was at Nagasaki in 1808 waiting to ambush Dutch traders. (A long story – worthy of another blog article!)

Beaufort as an admiral in later life

The Phaeton sailed well, but was not until three o’clock in the afternoon that she was sufficiently far ahead to signal back with credibility that initially one, then two, five, new sail had been sighted. She followed this up by signalling an even larger British force was approaching. It was known that the French had copies of the Royal Navy’s tabular signals, and Phaeton hoisted a signal to draw on the fictitious squadron. She then turned to sail back towards Cornwallis’s force, as if guiding the newcomers on. By sheer chance three small vessels were actually just visible over the horizon. Wholly taken in by the ruse, and apparently faced with the possibility of action with a larger force, the French broke off the action and retreated. Cornwallis’s entire force escaped without loss of a single ship,

One cannot but wonder if poor French morale in the aftermath of the brutal culling of the French naval officer-corps during the Revolution did not play a significant role. Defeat and failure could well be rewarded with the guillotine, and officers who still remained in service were likely to be highly risk-averse – as shown by the unwillingness to close, even when the British force was outnumbered. Cornwallis, by contrast, had command of a superbly confident and professional force. In his later report he gave special credit to the seamen and marines of the Mars and Triumph, which had the brunt of the French fire. He stated that, “instead of being cast down at seeing thirty sail of the enemy’s ships attacking our little squadron, they were in the highest spirits imaginable, and although circumstanced as we were, we had no great reason to complain of the conduct of the enemy, yet our men could not help repeatedly expressing their contempt of them. Could common prudence have allowed me to let loose their valour I hardly know what might not have been accomplished by such men.”

How the battle might have developed had the French exploited their numerical advantage –

Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg’s painting of the “Glorious First of June”, 1794

How the battle might have developed had the French exploited their numerical advantage –

Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg’s painting of the “Glorious First of June”, 1794

Cornwallis himself had given an example of calm resolution, shaving, dressing and powdering his hair during the morning chase according to his normal routine. He appeared to his flag captain that he had been in similar situations before, and knew very well what they, the French, would do.

What followed was to prove Cornwalis wholly correct in his evaluation of the enemy.

The latest Dawlish Chronicles novel has been published:Britannia’s Rule 1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

But Dawlish’s contest with the volcano is just the prelude to a longer association with the island. Its sovereignty is split – a British Crown Colony in the west, and in the east an independent republic established seven decades earlier by self-emancipated slaves. When wrenched from France through war, both seemed glittering economic prizes. Now they are impoverished backwaters where resentment seethes and old grudges fester. For many, the existence of a ‘black republic’ is resented, an affront to be excised. In France, a man of limitless ambition, backed by powerful interests, sees the turmoil as an opportunity that could bring him to absolute power. And, if he succeeds, perhaps trigger war in Europe on a scale unseen since the fall of Napoleon.

Through this maelstrom, Nicholas Dawlish must navigate a skillful course. Political concerns complicate challenges that can only be resolved by ruthless guile and calculated use of force. Lacking direct support from the Royal Navy, Dawlish must fight some of the most vicious battles of his career with inadequate resources and unlikely – and unreliable – allies.

Available in Paperback and Kindle (also readable on smartphones and tablets via Kindle App).Kindle Unlimited Subscribers can read it, or any of ten other Dawlish Chronicles, at no extra cost.For more details and for ordering, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au For amazon.caThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and with more still to come!Click on the image below for details of the individual booksSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or Smartphone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. It will update you on new books and provide other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Phaeton and Beaufort’s ruse, 1795 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

December 16, 2022

Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”

A Flawed Concept – The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”

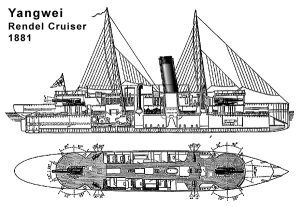

A Flawed Concept – The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”In my novel Britannia’s Spartan (click for details), set in 1882, an important role is played by a cruiser of the Imperial Chinese Navy, the Fu Ching. She is the fictional sister of two warships the Yang Wei and the Chao Yung, that did indeed serve in that navy. For a short period in the 1880s these vessels carried what was probably the heaviest armament for any ships of their sizes afloat. Built in British yards, their design had been evolved by Sir George Rendel, building on the success of his earlier concept, the “Flatiron Gunboat” which was armed with a single large-calibre weapon. (One of these gunboats is the heroine of my novel Britannia’s Reach (click for details). While these “Flatirons” were intended for use in estuaries and sheltered waters, the new design envisaged a small, cheap cruiser-type vessel suited for service in the open sea and carrying two of the most powerful guns then available. These were Armstrong 10” breech-loaders. With reasonable speed for the time, and with high mobility, these vessels would be suited, in theory at least, to engage larger and more heavily armoured, but less nimble ships. Despite the superficial attractiveness, the concept was turned down by the Royal Navy, due to concerns about seaworthiness in the English Channel and the North Sea. These areas might well become battlegrounds in any future war since France was perceived as Britain’s most likely potential enemy in this period.

Contemporary drawing – the sailing rig was unlikely to have been used except

Contemporary drawing – the sailing rig was unlikely to have been used except

during the initial delivery voyage from Britain to China

Overseas customers were now sought and the first ship of the type was laid down for Chile in 1879 as this nation’s war with Peru and Bolivia was commencing. In the event that war ended before the vessel was completed and she was taken over by the Imperial Japanese Navy as the Tsukushi. She was to serve without distinction in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.Her construction and completion was however overtaken by two generally similar vessels for another Far Eastern customer when an order was placed by China. In the early 1880s the corrupt and floundering Chinese Empire was wakening up to the threats posed by growing Russian and Japanese power on its northern and eastern borders, as well as the pressure from France the south, from what is now Viet-Nam, and which was to erupt into the Sino-French War of 1885 which ended in a humiliating Chinese defeat. The need for a strong navy to protect China’s long coastline was obvious but corruption and inefficiency was to make progress in this spasmodic and inconsistent. A few ships of limited capacity could be built at the Foochow Dockyard and equipped with imported guns, but the majority were contracted from European sources, German as well as British, resulting in a wide variety of calibres of guns and munitions.

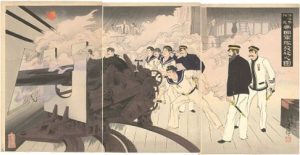

Japanese view of the Battle of the Yalu, 1897

Japanese view of the Battle of the Yalu, 1897

One of the superb woodblock prints made in Japan at the time

The two Chinese “Rendel cruisers”, named Yang Wei and Chao Yung were of a mere 1350 tons, length 220 feet and beam of 32 feet. Two compound engines, each of 1300 HP, ensured a maximum speed of 16 knots, a respectable speed at a time when the Royal Navy’s HMS Iris, then entering service, was regarded as a marvel for achieving just under 18 knots. Like the Iris, the Chinese cruisers were of all-steel construction, which was also an innovation, but their most remarkable feature was their armament. Each ship carried two 10-inch Armstrong breech-loaders, one forward, one aft. There were mounted so as to pivot inside fixed steel drums, armoured shutters being raised to allow bearing on limited arcs ahead and astern (45 °) and on either side (70 °). In addition each ship carried four 4.7 – inch breech-loaders, two on each broadside, as well as what would have been a fearsome collection of Gatling and Nordenvelt guns’ for protection against torpedo boats. The hulls had only low freeboard fore and aft and had to be built up for the delivery voyage from Britain to China. A simple fore and aft rig was carried to supplement the engines and was probably of most use during delivery. Like Royal Navy ships of the period – notably HMS Inflexible – electricity generation on shipboard represented a major innovation, allowing incandescent light fixtures, including arc searchlights. Hydraulic steering was another innovation – and perhaps a needless complication.

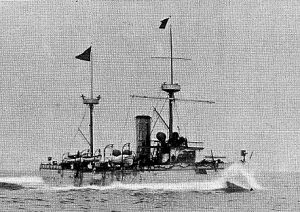

Chinese ensign, initially triangular, later a rectangle

The Yang Wei and Chao Yung entered service in 1881. Though spasmodic efforts were made to fashion the Chinese Navy into an effective force, the state of unrest, corruption and reluctance to challenge traditional thinking meant that the process was never effective. This was by comparison with the fast-modernising Empire of Japan, which already had ambitions to dominate the Far East and set out to build a powerful navy on the model of the Royal Navy. Japanese naval development was based on coherent planning, with the emphasis not only on the necessary “hardware” – the ships and weapons – but also on “software aspects” – structured organisation, training plans and an ethos of professionalism and pride. By contrast the Chinese navy acquired ships on a random and piecemeal basis, without reference to any single coherent plan. Corruption was rife and the navy was divided into as many as four different “fleets” which at any time might, or might not, cooperate with each other.

Chinese cruiser Chao Yung_1894

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 announced Japan’s arrival as a major power on the world stage and resulted in humiliating defeats of Chinese forces by both land and sea. By the time of the war’s outbreak, the Yang Wei and Chao Yung were in a very poor state of maintenance, little more than half their original top speed being achievable and probably several of their weapons being unserviceable. Extensive use of wooden partitioning, overlain with layers of varnish, made them particularly vulnerable to onboard-fire. The concept of the large but slow-loading gun-armament on a small vessel with limited armoured protection was by now overtaken by the development of smaller-calibre quick-loading weapons. In addition, lack of professionalism and corruption so serious that there were rumours of munitions being sold off by officers had made the Chinese Navy a hopeless adversary against the super-efficient Japanese.

Japanese cruisers in action at the Battle of the Yalu – note Chinese ships burning

In the key Battle of the Yalu on 17th September 1894 both the Yang Wei and the Chao Yung were placed in the Chinese line of battle. They were subjected to a hail of explosive 6-inch and 4.7-inch shells from the Japanese cruisers involved and both vessels were soon engulfed in flames as the wooden fittings took light.

The Yang Wei’s and Chao Yung’s Nemesis – Japanese guns in action

With her steering damaged the Yang Wei collided with the German-built Chinese cruiser Jiyuan and sank in shallow water, as did the Chao Yung, which may have been trying to save itself by beaching. It was a sad end for two vessels which in their time were mistakenly regarded as being at the cutting edge of naval development.

The latest Dawlish Chronicles novel has been published:Britannia’s Rule 1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

But Dawlish’s contest with the volcano is just the prelude to a longer association with the island. Its sovereignty is split – a British Crown Colony in the west, and in the east an independent republic established seven decades earlier by self-emancipated slaves. When wrenched from France through war, both seemed glittering economic prizes. Now they are impoverished backwaters where resentment seethes and old grudges fester. For many, the existence of a ‘black republic’ is resented, an affront to be excised. In France, a man of limitless ambition, backed by powerful interests, sees the turmoil as an opportunity that could bring him to absolute power. And, if he succeeds, perhaps trigger war in Europe on a scale unseen since the fall of Napoleon.

Through this maelstrom, Nicholas Dawlish must navigate a skillful course. Political concerns complicate challenges that can only be resolved by ruthless guile and calculated use of force. Lacking direct support from the Royal Navy, Dawlish must fight some of the most vicious battles of his career with inadequate resources and unlikely – and unreliable – allies.

Available in Paperback and Kindle (also readable on smartphones and tablets via Kindle App).Kindle Unlimited Subscribers can read it, or any of ten other Dawlish Chronicles, at no extra cost.For more details and for ordering, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au For amazon.caThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and with more still to come!Click on the image below for details of the individual booksSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or Smartphone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. It will update you on new books and provide other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers” appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 13, 2022

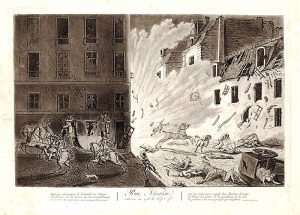

Ordeal by Fire – RMS Amazon, 1852

The Loss by Fire of the RMS Amazon, 1852

The Loss by Fire of the RMS Amazon, 1852Ships are still lost at sea in our own time, frequently as a result of regulations and standards being ignored rather than standards being established in the first place to ensure safe operation. When reading of seafaring in the 19th Century, and the vast numbers of maritime disasters, one is struck by the fact that not only had standards not been established, but that little thought went into recognising inevitable hazards and to identifying measures to mitigate or eliminate them. The most glaring example refers to provision of adequate numbers of lifeboats – a straightforward and obvious measure, the absence of which resulted in heavy loss of life for decades until the Titanic disaster in 1912 finally made action unavoidable. Similar shortcomings applied as regards protection against fire, an especially serious concern when steam-engines were installed in wooden ships. In addition, one is struck, when reading about Victorian-era, by what frequently amounted to an all but wilful blindness to signs of danger. This latter was to be a factor in one of the most horrific of passenger-trade tragedies, the loss by fire of the (Royal Mail Steamer) RMS Amazon, in 1852.

The horror of fire at sea, as conveyed by James Francis Danby (1816-1875)

The horror of fire at sea, as conveyed by James Francis Danby (1816-1875)

Constructed in 1850-51, the RMS Amazon, at 2256-tons and 300-feet long, and her four sisters were among the largest wooden-hulled steamers ever built, for by this time iron construction was becoming commonplace. Intended for the mail service between Britain and the West Indies, the 800-horsepower RMS Amazon was paddle-driven and capable, under steam, of a maximum of fifteen knots, though her usual cruising speed would have been closer to eleven. As with almost all steamers of the time she also carried a sailing rig, in her case of three-masted barque configuration. Her crew of 112 reflected the need to operate under sail as well as to feed the furnaces and tend the engine. There was accommodation for 50 passengers.

Commanded by a Captain Symonds, the RMS Amazon left Southampton on her maiden voyage to the West Indies on 2nd January 1852. According to accounts by survivors of the subsequent tragedy, alarm was felt immediately by many passengers as regards risk of fire. The two engines installed appeared to be overheating and the captain and engineer stopped them several times to allow them to cool. A Mr. Neilson was too worried by this to go below decks and another, a Mr. Glennie, attested that may of the crew were no less concerned. Despite this, Captain Symonds was not prepared to return to Southampton.

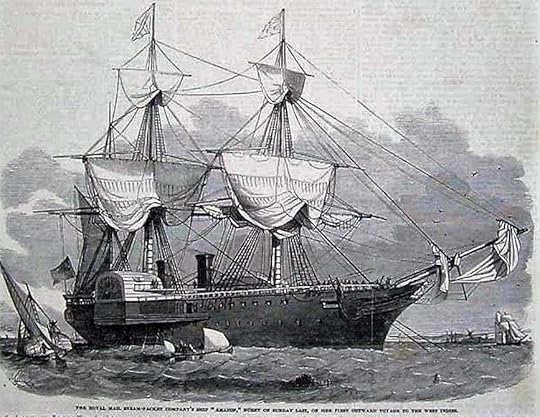

The impressive RMS Amazon, as seen before departure on her maiden voyage

The impressive RMS Amazon, as seen before departure on her maiden voyage

Thirty-six hours into her voyage the RMS Amazon ran into a high headwind in the Bay of Biscay and soon after midnight fire was seen erupting from just abaft the foremast. The watch-officer sent the quartermaster to rouse the captain, who was sleeping, and as he did alerted the passengers, apparently in a way that encouraged alarm. Even before the captain reached the bridge – which ran across between the paddle-boxes – the fourth engineer, a heroic man names Stone, attempted to go below to stop the engines but was driven back by heat and smoke. Efforts were in progress to drag a fire-hose forward when the blaze reached the oil and tallow store, worsening the inferno. Terrified passengers were now crowding on deck to be confronted with a wall of flame that spanned the deck and was as high as the paddle-boxes, isolating the officers, who were aft, with most of the crew, who were on the forecastle. The only way past the flames was to creep up the curved surface of the paddle-boxes and slide down the other side, a manoeuvre so dangerous that few attempted it.

By this stage panic was already manifesting itself among passengers and crew alike. An account of the tragedy in an 1877 publication leaves little to the imagination: “It would be needless to tell her o the screams and shrieks of the terrified passenger, mixed with the cried of the animals on board; of the wild anguish with which they saw before them only the choice of deaths, and both almost equally dreadful – the raging flames or the raging sea; and of these fearful moments when all self-control, all presence of mind, appeared to be lost, and no authority was recognised, no command obeyed.”

Every effort was made to prevent the flames extending aft. The RMS Amazon carried nine boats and, remarkably for this period, had in theory sufficient accommodation in them for all passengers and crew, but they could not be safely lowered as the unreachable engines were still running and driving the vessel forward at some thirteen knots. The captain hoped that the ship’s movement would finally be arrested by exhaustion of the contents of the boilers but it transpired that when fire was first detected one of the engineers, fearing a boiler explosion, had opened the feed line from the water cistern to maintain a continuous feed. As the ship’s headlong charge continued, Captain Symonds ordered all boats to be kept fast until he should order lowering. By the time he did, when the spread of the flames was clearly unstoppable, the forward life-boats were already on fire. According to the 1877 source: “When this was discovered, all order and discipline seemed to disappear immediately, and instead of fortitude and resolution, a selfish desire for preservation entered almost every breast.”

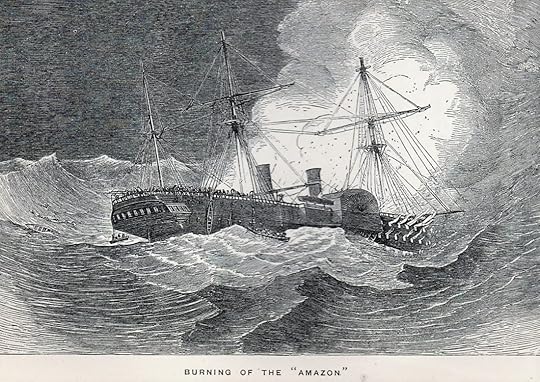

RMS Amazon ablaze – contemporary illustration. Note boat hanging from davit.

RMS Amazon ablaze – contemporary illustration. Note boat hanging from davit.

Unfamiliarity with the handling-equipment of the remaining boats now played its role – a sad indication of inadequate crew-training before departure. They were suspended from davits in the usual way but their keels were held in protruding cradles to prevent them swinging but the crew seemed unaware of this. Due to this at least three boats were flipped over as they were lifted and they dumped their occupants into the sea. The captain assisted in lowering the boats and when no more could be done went back to the wheel, took it from the steersman, and apparently perished at his post. The remaining boats did get away, the first to do so carrying sixteen people, including the Mr. Neilson previously referred to. It rescued a further five from a dinghy that had also got away – it was almost swamped and the occupants were bailing with boots – but the now empty dinghy drove into the stern of the lifeboat and wrecked her rudder.

The gale continued another three hours and all that could be done in the lifeboat was to keep her head to the wind by her oars and save her from swamping. The blazing RMS Amazon was visible in the distance, her masts toppling over in succession as the flames ate them away. A sailing vessel now appeared, heading out from the French coast, and passed within four hundred yards of the lifeboat, which hailed her. An answer was made by signal but she made no attempt to assist and continued on her course. Around dawn, an explosion was seen to engulf the RMS Amazon. The funnels toppled over and then she herself disappeared. The lifeboat pulled for the French coast and in mid-morning was picked up by a British brig, the Marsden, which landed the survivors in France.

[image error]Burning Ship by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900) – how the Amazon must have looked

The RMS Amazon’s pinnace had also got way although on launching its occupants had been tipped into the sea. A few managed to clamber back on to the ship though a lady clutching an eighteen-month old child, a Mrs. M’Lennan, managed to keep hold of the boat until it was righted. It finally got away with sixteen occupants, including the Mr. Glennie mentioned earlier. An ex-Royal Navy seaman called Berryman (“a fine fellow”) trailed a portion of a spar as a sea anchor to hold the over-loaded boat’s head to. the wind and later, when the sea had calmed, hoisted Mrs. M’Lennan’s shawl between two boat hooks as a sail. Mr. Glennie noted as he saw the RMS Amazon drew away that “a large hole was burnt out of her side immediately abaft the (port) paddlebox, part of which was also burnt. The hole was nearly down to the water’s edge and through it I could see the machinery.” The pinnace survived into the morning, a leak that threatened to swamp her being stopped by Stone, the heroic engineer, and it steered for the French coast. “the men plying their oars lustily, and Mrs. M’Lennan, as she lay in the sternsheets, cheering them to their work.” Later in the day another vessel was sighted and the lady’s shawl was again put to good use for signalling. It proved to be a galiot, a small Dutch trading vessel called the Gertruda, which picked up the pinnace’s occupants and set her course towards Brest to land them. On the way more survivors were picked up from another boat.

A Dutch Galliot

The disaster had occurred on January 4th and it was not until the 15th of the month that it emerged that another thirteen persons had also been saved. They had been rescued by another Dutch vessel, the Hellechina, en route to Leghorn, which transferred them to a British revenue-cutter which took them to Plymouth. These survivors’ experiences were no less horrific than those of the others. The boat had been lowered safely from the Amazon, though a stewardess had fallen out and been drowned in in the process. Command was adopted by a Royal Navy officer, a Lieutenant Grylls, who had been a passenger on the Amazon and who had been active helping fight the fire previously. The boat was however leaking badly – “Fox, a stoker, stopped the hole by taking off his drawers and cramming them into it, keeping them in position for three or four hours by the pressure of his own body; and when seized by violent cramps was relieved by Durdney and Wall.” Another ship passed between them and the burning RMS Amazon, though without seeing them – though it must have seen the Amazon. One wonders if it was not the same vessel that had acknowledged the lifeboat’s signal but had carried on regardless. Gryll’s boat lacked oars and attempts were made to paddle her with the bottom boards. In the course of the morning it passed over the area where the RMS Amazon had gone down, strewn as it was with wreckage, but with no sign of bodies. Later in the day rescue came in the shape of the Hellechina.

Of the 162 people on the RMS Amazon only 58 survived. The loss was regarded as a national tragedy with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert heading an appeal for the support of widows and orphans. A subsequent enquiry was inconclusive as regards the origin of the fire. Though blame was placed by some on the engine bearings running hot – and indeed insufficient testing had been done prior to committing to the maiden voyage – this seems to have been unlikely since the engines continued to operate without seizing until the ship consumed herself. A further consideration was that the crew was freshly raised, knew little of each other and had not exercised together. The rapid spread of the fire was attributed to the use of much “Danzig Pine” in the construction, a timber known to be particularly inflammable. The single most significant contributory factor was most likely however to be the haste in which the ship had been rushed into service without adequate shake-down of both crew and machinery.

The iron-hulled RMS Atrato by William Frederick Mitchell (1845-1918)

The iron-hulled RMS Atrato by William Frederick Mitchell (1845-1918)

And one lesson was most certainly learned. The next Royal Mail ship commissioned, the Atrato, was constructed of iron.