Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 2

July 2, 2025

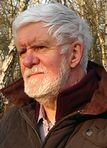

Vitus Bering: forgotten explorer

Soviet Stamp: 300th Anniversary of Bering

When thinking of the exploration of the Pacific the name that most immediately comes for mind is that of Captain James Cook (1728 – 1779) whose three voyages in the 1760s and 70s added immensely to knowledge of that ocean. These expeditions, meticulously planned, splendidly resourced and staffed by excellent officers, seamen, cartographers and scientists, were the equivalent in their own day of the Apollo Program. The focus in the first two voyages was on the South Pacific and Australasia but the third, which was to see Cook murdered in Hawaii, focussed on the Northern Pacific and its North American coastline. In the course of this voyage Cook penetrated the Bering Strait between Asia and Alaska and entered the fringes of the Arctic Ocean.

Cook’s achievement was impressive, but the initial exploration of the Northern Pacific had been almost a half-century earlier by a man who had to cope with far greater challenges as regards resourcing and back-up. Though he gave his name to the Strait that separates Asia and America , Vitus Jonassen Bering (1681-1741) is largely unknown outside Russia. His achievement in the face of almost insuperable odds make him however one of the true giants of exploration.

Born in Denmark, and at sea from the age of 18, Bering was one of the many foreign officers recruited by Czar Peter the Great (1672 – 1725) who was rapidly modernising his country and establishing it as a great European power. A key element in his strategy was not only securing a Russian outlet on the Baltic – which became the new capital, St. Petersburg – but the creating from scratch of a navy to defend it. “The Great Northern War” that raged between Russia and Sweden from 1700-1721 saw Peter’s ambitions realised.

Bering had been with the Russian Navy since 1704 and though he resigned briefly in 1724 he re-enlisted almost immediately, around the time of Peter’s death. Rule of the vast empire now passed to Peter’s widow Catherine (1684 –1727), a woman of obscure and lowly origin who was to prove herself surprisingly capable in government affairs. She inherited Peter’s ambition to have Eastern Siberia’s Pacific coastline and the seas beyond mapped for the first time. At this time Russian settlers, very few in number, were established on a scattering of small settlement communities on the Sea of Okhotsk and on the vast peninsula of Kamchatka. None of these places possessed port or shipbuilding facilities and any exploration expedition would be expected to build the vessels it needed once it got to the coast there.

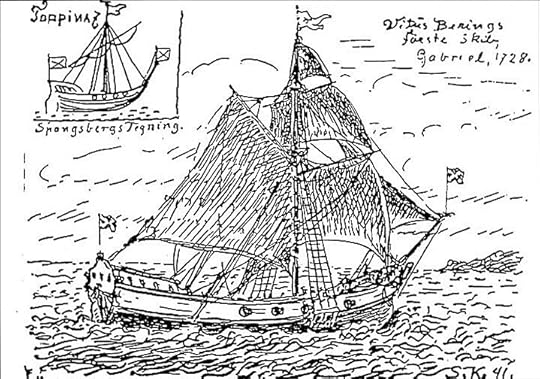

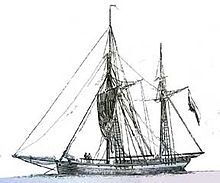

The choice of Bering as expedition leader seems to have reflected some prior experience of distant navigation, notably in the Indian Ocean and the North American East Coast. Supported by a cartographer and several experienced officers, Bering’s instructions were to move up Kamchatka’s east coast and to determine whether a strait did indeed exist – as was suspected – between Asia and America. Bering’s first challenge was to get to Russia’s Far East. Leaving St. Petersburg on February 5th, 1725, and crossing Siberia – much of it still all but unexplored – by horse, foot and boat, and enduring food-shortages and savage winters, Bering, his men and their equipment took two years to reach Okhotsk. By early 1728 they had crossed to Kamchatka, where, on the 4th of April building commenced of a boat called the Gabriel. This was based on the design of a Baltic packet-boat. The challenge of doing so was immense for timber had to be cut down and dressed into planks for construction. It is therefore all the more impressive that this craft was ready enough to set sail some three months later, in mid- July.

The Gabriel as drawn by Martin Spangsberg in 1827. Picture: Danish Geografisk Tidsskrift

The Gabriel as drawn by Martin Spangsberg in 1827. Picture: Danish Geografisk Tidsskrift

In conformance with his orders Bering crept north-eastwards alone the coast, discovering St. Lawrence Island. He passed through what is now known as the Bering Strait, into the Chukchi Sea. It was still however impossible to say with certainty that the Asian and American landmasses were separate, although it was suspected, but rapidly advancing ice in mid-August forced Bering to the decision to return to Kamchatka. The voyage had lasted seven weeks. His return overland journey to report his findings in St. Petersburg now commenced, arriving in early 1730. He was ennobled for his work and his had findings aroused sufficient questions for a second expedition to be necessary to resolve them.

It seems amazing by modern standards that it should have taken a decade before the next expedition, once more under Bering’s command, finally set sail from Kamchatka. (The contrast with the will to mount Cook’s three expedions in a decade is obvious). The intervening years had been occupied by political manoeuvring, command issues and logistics challenges. Supplies were once more carried across Siberia, a proposal to send them by sea around Cape Horn being rejected. Two new vessels were constructed at Okhotsk, the Michael and the Nadezhda, in addition to refurbishment of the Gabriel. Thereafter three other vessels, St. Peter, St. Paul and Okhotsk , followed – these were to form Bering’s exploration flotilla, he himself on board the St. Peter.

1966 Soviet postage-stamp showing course of Bering’s last voyage

1966 Soviet postage-stamp showing course of Bering’s last voyage

It was 1741 before the new expedition sailed from Kamchatka. The three-ship flotilla was dispersed in a storm soon afterwards and Bering decided to press on alone. He headed for the American coast and pressed eastwards along it, touching at Kayak Island and sighting Mount Saint Elias, on the northern end of what is now Alaska’s Panhandle. A second ship got separately as far as Prince of Wales Island before turning back. Scurvy, the cause of which was then not understood, was now however hitting Bering’s crew so badly that they were barely capable of working the ship. There was no option but to turn back towards Kamchatka, discovering several islands of the Aleutian chain in the process.

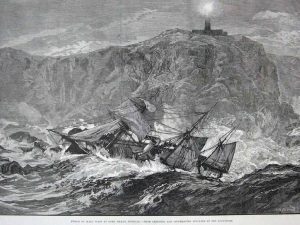

Shipwreck on Bering Island

Shipwreck on Bering Island

Bering was by now too ill to leave his cabin. Nearing the peninsula in early November, at what was later to be called Bering Island, the St. Peter was hit by a storm that drove her towards rocks offshore. Attempts to moor failed but the sea was powerful enough to wash the damaged vessel bodily over the rocks into quieter water, where it was trapped. Salvation was illusory – the island was barren, devoid of trees, and with little driftwood. With the ship no longer a place of refuge, small ravines were roofed over to provide shelter. Many of the scurvy-racked crew died during transfer ashore. Bering himself survived this landing but had to be moved about on a wheel-barrow and he directed survival efforts as long as possible. He died a month later in a shelter which was already collapsing – it proved necessary to dig him out before he could be formally buried.

Given the challenges they faced, it is surprising that 45 of the St. Peter’s 75-man crew were to survive the freezing privations of the winter, doing so by eating the carcasses of dead whales that had been driven ashore. In the following spring they managed to construct a boat from the wreckage of their ship and in it they reached Kamchatka.

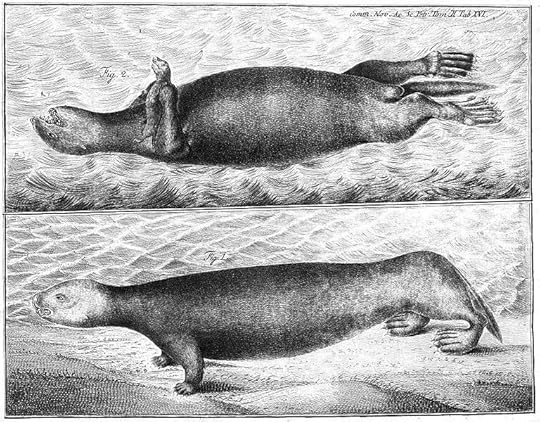

A Sea Otter drawn by Georg Wilhelm Steller. (Wikipedia Commons)

A Sea Otter drawn by Georg Wilhelm Steller. (Wikipedia Commons)

Despite its disastrous cost in human terms, Bering’s last expedition yielded valuable geographical and scientific information. This included mapping of much of the coast of present day Alaska. The expedition’s German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709 – 1746) identified six new species of birds and animals. He continued his studies while marooned on Bering Island and was subsequently to write a book describing its fauna. Steller’s fate was to be a sad one. He spent two years exploring Kamchatka after he returned there but because of his sympathy for the indigenous population he was accused of instigating a rebellion. Summoned back to St. Petersburg, he died of illness on the way.

Bering’s discoveries were the impetus for the halting, poorly-conceived, badly managed and under-resourced efforts to establish of a Russian presence in North America. Fort Ross, 65 miles north of San Francisco, was the most southerly of the settlements and lasted until 1841. Had more attention been paid to developing these opportunities, and should there have been any clear vision of what could have been achieved, it is unlikely that the Czarist government would have sold Alaska to the United States for a pittance in 1867. Doing so could have had incalculable strategic and epoch-changing consequences – one of the great “What Ifs” of history.

Britannia’s Spar tanRead it as a stand-alone novel or as part of the Dawlish Chronicles series 1882: Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

1882: Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

Dawlish has no forewarning of the nightmare of riot, treachery, massacre and battle he and his crew will encounter.

A new balance of power is emerging in the Far East. Imperial China, weak and corrupt, is challenged by a rapidly modernising Japan, while Russia threatens from the north. They all need to control Korea, a kingdom frozen in time and reluctant to emerge from centuries of isolation.

Dawlish finds himself a critical player in a complex political powder keg. He must take account of a weak Korean king and his shrewd queen, of murderous palace intrigue, of a powerbroker who seems more American than Chinese and a Japanese naval captain whom he will come to despise and admire in equal measure. And he will have no one to turn to for guidance…

Available in Paperback and in Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle unlimited read at no extra charge. Click below for purchase details.

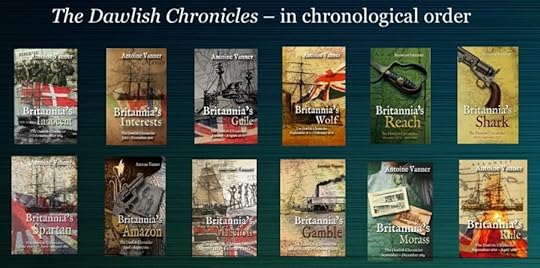

For USA For UK & Ireland For Canada For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post Vitus Bering: forgotten explorer appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 19, 2025

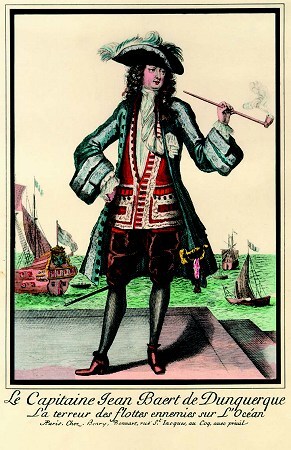

Jean Bart – Sea Devil Incarnate

The French Navy’s record through the centuries never achieved the string of memorable victories won by Britain’s Royal Navy – though one French triumph, that of the Virginia Capes in 1781, was decisive in assuring American Independence. One French naval hero was however to achieve a status in his countrymen’s eyes comparable to Nelson in British ones. This was Jean Bart (1650 – 1702), a man whose career was so dramatic, and whose character was so outlandish, that only the most daring of authors would create a similar figure in fiction.

The French Navy’s record through the centuries never achieved the string of memorable victories won by Britain’s Royal Navy – though one French triumph, that of the Virginia Capes in 1781, was decisive in assuring American Independence. One French naval hero was however to achieve a status in his countrymen’s eyes comparable to Nelson in British ones. This was Jean Bart (1650 – 1702), a man whose career was so dramatic, and whose character was so outlandish, that only the most daring of authors would create a similar figure in fiction.

The name Dunkirk evokes today images of the almost miraculous evacuation of British and French forces in 1940 from the harbour and nearby beaches of this port on the French side of the English Channel. It played an equally important role in the late seventeenth century, when Britain, France and the Netherlands were locked in an almost continuous series of wars, as it represented the most northerly French naval base. As such it provided a fortified refuge and source of supply not only for formal naval forces but also for privateers. Its possession was vital for supporting French efforts to control the Channel and the North Sea and for harrying British and Dutch maritime commerce.

The boyhood of Jean Bart – French chocolate label!

It was here that Jean Bart was born, in 1650, to a seafaring family. It may not have been French – there is some evidence that his original name was Jan Baert, indicating a Flemish origin, and that he spoke both languages. (Even today the French/Flemish linguistic boundary lies around a dozen miles north-east of Dunkirk). Details appear scarce but he seems to have first gone to sea in Dutch service, under the illustrious Admiral Michiel de Ruyter in the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664-67), from which the Dutch emerged victorious.

The price of Louis XIV’s glory – French atrocities during the invasion of the Netherlands

In 1672 France invaded the Dutch Republic, the so-called United Provinces. The Dutch fought back ferociously, so initiating six-years of warfare in which, surprisingly in view of later history, Britain was to be France’s ally for the first two years. Jean Bart now entered French service, not as a naval officer – a rank not open to men of humble birth – but as a privateer operating out of Dunkirk. Such privateers were privately-owned ships sailing under a “letter of marque”, with government backing, and were frequently funded by syndicates of investors. Bart’s raids on Dutch commerce during the first years of the war were so fruitful that in 1675, at his own expense, he could afford to equip a sloop carrying two guns and 36 men. With this he at once captured a Dutch warship mounting eighteen guns and crewed by 65 men. He continued to take prizes and could now afford to fit out a 10-gun ship, promptly capturing a Dutch 12-gun vessel. He then was given command of five frigates, and on March 4th, 1676, captured an 18-gun Dutchman. Shortly afterwards he met eight British merchant ships, escorted by three warships. He promptly captured one of the escorts, drove the others off, and took the merchantmen into Dunkirk. In September of the same year he captured the Neptune, a 36-gun frigate, and her entire convoy. During the six years the war lasted he took 49 vessels in total.

French ship under attack by Barbary corsairs, mid-17th Century

With peace restored Bart, despite his lowly birth, was awarded a lieutenant’s commission – a first step in the Royal French Navy that was ultimately to carry him to the rank of admiral. He was now given command of a 14-gun ship and sent to cruise off North Africa against the Barbary corsairs who were to be a scourge of European – and later American – shipping for another century and a half. This resulted in capture of a large armed-xebec which was brought back to Toulon as a prize.

In 1683 France was at war again, this time with Spain. It lasted less than a year but it gave Jean Bart the opportunity to take a Spanish vessel carrying 350 troops, which he sent in to Brest. He followed this up by capturing two warships off Cadiz, receiving a severe thigh-wound in the process.

King Louis XIV’s territorial ambitions were to trigger war again in 1688, a nine-year conflict which was to pitch France against the so-called “Grand Alliance” of the Dutch, British, Holy Roman Empire and several lesser principalities. For Jean Bart this was the start of the most spectacular part of his career. He now commanded a 24-gun frigate, and immediately took a Dutch privateer, but his luck ran out when he ran into met two 50-gun British ships. Taken prisoner, he was brought to Plymouth but was to make a daring escape, stealing a boat and rowing in two and-a-half days across the Channel to near St. Malo on the coast of Brittany.

The long row home – Jean Bart escaping from Plymouth to St. Malo

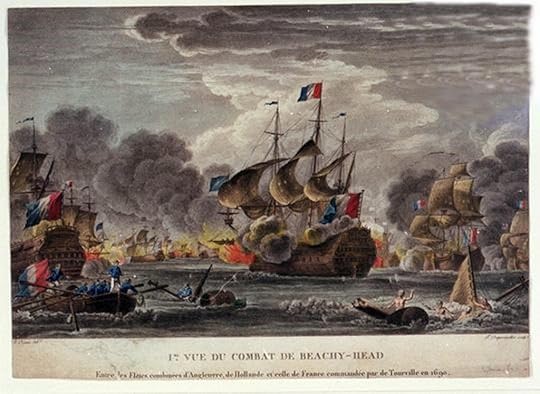

Now a national hero, Jean Bart was promoted to captain and given command of the frigate Alcyon. In her he was to fight under the Count de Tourville at the Battle of Beachy Head (1690) in the English Channel – known by the French as the Battle of Béveziers – a French tactical victory which resulted in British and Dutch losses of eleven ships for no French loss. This gave the French temporary control of the English Channel but de Tourville did not follow up the victory. The battle is unique in that both commanders, British and French, were to lose their commands because of their poor performances.

The Battle of Beachy Head, July 1690, by Nicholas Ozanne

Jean Bart’s next assignment was escorting merchant shipping from Hamburg to Dunkirk, an activity he combined with successful commerce-raiding in the North Sea. By 1691 however enemy forces had blockaded Dunkirk. Bart escaped with several small vessels, slipped out at night and opened fire on the blockading squadron as he passed. The following evening he captured two British ships, of 40 and of 50 tons respectively, together with merchant ships he took in to Bergen, in neutral Norway. He then directed his attention to savaging a large Dutch fishing fleet, burning most of them, seizing their escorts and landing their crews in England coast, then going on north to plunder and burn villages on the Scottish coast. Again blockaded in Dunkirk , he once more broke out successfully in October 1693 and immediately hurled himself on British shipping, sustaining his record of captures, raiding the English coast near Newcastle and returning with enormous spoils. Sallying out again from Dunkirk with three frigates, he captured more merchant vessels before engaging a convoy escorted by three men-of-war. Two of these he captured but the third, a 54-gun vessel, fought off three attempts to board her. She made her escape, abandoning the convoy to Bart.

The Battle of Texel, June 1694, by Eugene Isabey

The battle that was to earn Jean Bart his title of nobility was fought off the Dutch island of Texel on 29th June 1694 when, with a flotilla of seven ships, he recaptured a French convoy which had earlier that month been taken by the Dutch. He also took three warships of the eight-strong escort. Greeted with rapture on his return to Dunkirk, he found himself invited to Versailles to receive the personal congratulations of Louis XIV.

Bart’s last triumph in the North Sea was at the Battle of the Dogger Bank on 17th June 1696. It was initiated by his locating a Dutch convoy of 112 merchantmen, escorted by five warships. Speed was essential, because a large British squadron under Admiral John Benbow was searching for Bart’s force of seven ships. Bart threw his own ship nevertheless at the Dutch flagship, the Raadhuis van Haarlem, capturing it in a three-hour battle. Four more Dutch warships surrendered. Bart then burned 25 merchant ships, making away to the east only as Benbow’s squadron hove into sight. A year later the Treaty of Rijswijk brought the war to an end, and with it Bart’s fighting career. He died five years later, still a relatively young man, yet one who had packed more into a single life than the vast majority of men ever dream of.

A lesson in courage – Jean Bart ties his son to the mast during a

battle

A lesson in courage – Jean Bart ties his son to the mast during a

battle

Jean Bart was to achieve mythic status in death, the embodiment of an “up and at them” tactical commander rather than a strategist. Records indicate that he captured a total of 386 ships, besides sinking or burning many more. Some of the stories told of him may or may not be true, but even the fanciful ones hint at the nature of his character. One tale has him causing outrage among courtiers at Versailles by smoking his pipe in the ante-room while waiting for an audience with Louis XIV. On the king asking him how he broke the blockade at Dunkirk, he is said to have arranged the courtiers present in a line, then attacking them with his fists, knocking them down, as a practical demonstration. In 1697, towards the end of the war, he was tasked with carrying the Prince de Conti (François-Louis de Bourbon), the French candidate for the Polish crown, to Danzig. This demanded slipping six frigates through a tight enemy blockade. When clear of danger, the prince asked Bart if he had not been afraid that the enemy might have captured them. Much to the Prince’s horror, Bart informed him that not the slightest danger of such a contingency had existed, as his son had been stationed with a match in the magazine to blow up the ship upon receiving a pre-arranged signal. Another story has him tying his own son to a mast during an action to cure him of fear of death and gunfire.

Jean Bart under attack from USS Ranger planes 1942

Jean Bart’s memory has been preserved in the French Navy, some 27 ships being named for him since his death. The most famous was France’s last battleship, which in November 1942, when only partly completed, was to fire on American warships during the Casablanca landings until silenced by dive bombers from the carrier USS Ranger and five 16-inch hits by the USS Massachusetts. This was one of the last occasions when American forces fought the French. Finally completed after WW2, she was to remain in French service until 1961. The current vessel is an anti-aircraft frigate launched in 1988.

The name of Jean Bart lives on.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent Typical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below: For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post Jean Bart – Sea Devil Incarnate appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 4, 2025

RMS Amazon – Ordeal by Fire, 1852

Ships are still lost at sea in our own time, frequently as a result of regulations and standards being ignored rather than standards being established in the first place to ensure safe operation. When reading of seafaring in the 19th Century, and the vast numbers of maritime disasters, one is struck by the fact that not only had standards not been established, but that little thought went into recognising inevitable hazards and to identifying measures to mitigate or eliminate them. The most glaring example refers to provision of adequate numbers of lifeboats – a straightforward and obvious measure, the absence of which resulted in heavy loss of life for decades until the Titanic disaster in 1912 finally made action unavoidable. Similar shortcomings applied as regards protection against fire, an especially serious concern when steam-engines were installed in wooden ships. In addition, one is struck, when reading about Victorian-era, by what frequently amounted to an all but wilful blindness to signs of danger. This latter was to be a factor in one of the most horrific of passenger-trade tragedies, the loss by fire of the (Royal Mail Steamer) RMS Amazon, in 1852.

The horror of fire at sea, as conveyed by James Francis Danby (1816-1875)

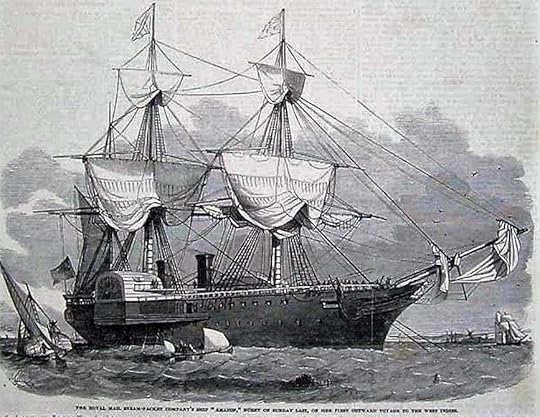

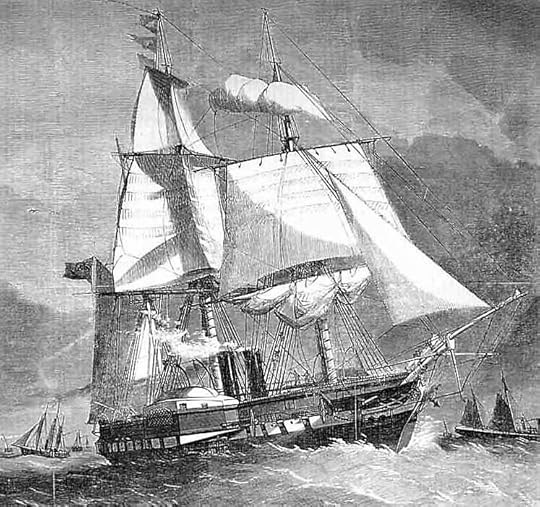

Constructed in 1850-51, the RMS Amazon, at 2256-tons and 300-feet long, and her four sisters were among the largest wooden-hulled steamers ever built, for by this time iron construction was becoming commonplace. Intended for the mail service between Britain and the West Indies, the 800-horsepower RMS Amazon was paddle-driven and capable, under steam, of a maximum of fifteen knots, though her usual cruising speed would have been closer to eleven. As with almost all steamers of the time she also carried a sailing rig, in her case of three-masted barque configuration. Her crew of 112 reflected the need to operate under sail as well as to feed the furnaces and tend the engine. There was accommodation for 50 passengers.

Commanded by a Captain Symonds, the RMS Amazon left Southampton on her maiden voyage to the West Indies on 2nd January 1852. According to accounts by survivors of the subsequent tragedy, alarm was felt immediately by many passengers as regards risk of fire. The two engines installed appeared to be overheating and the captain and engineer stopped them several times to allow them to cool. A Mr. Neilson was too worried by this to go below decks and another, a Mr. Glennie, attested that may of the crew were no less concerned. Despite this, Captain Symonds was not prepared to return to Southampton. The impressive RMS Amazon, as seen before departure on her maiden voyage

The impressive RMS Amazon, as seen before departure on her maiden voyage

Thirty-six hours into her voyage the RMS Amazon ran into a high headwind in the Bay of Biscay and soon after midnight fire was seen erupting from just abaft the foremast. The watch-officer sent the quartermaster to rouse the captain, who was sleeping and, as he did, alerted the passengers, apparently in a way that encouraged alarm. Even before the captain reached the bridge – which ran across between the paddle-boxes – the fourth engineer, a heroic man names Stone, attempted to go below to stop the engines but was driven back by heat and smoke. Efforts were in progress to drag a fire-hose forward when the blaze reached the oil and tallow store, worsening the inferno. Terrified passengers were now crowding on deck to be confronted with a wall of flame that spanned the deck and was as high as the paddle-boxes, isolating the officers, who were aft, with most of the crew, who were on the forecastle. The only way past the flames was to creep up the curved surface of the paddle-boxes and slide down the other side, a manoeuvre so dangerous that few attempted it.

By this stage panic was already manifesting itself among passengers and crew alike. An account of the tragedy in an 1877 publication leaves little to the imagination: “It would be needless to tell her o the screams and shrieks of the terrified passenger, mixed with the cried of the animals on board; of the wild anguish with which they saw before them only the choice of deaths, and both almost equally dreadful – the raging flames or the raging sea; and of these fearful moments when all self-control, all presence of mind, appeared to be lost, and no authority was recognised, no command obeyed.”

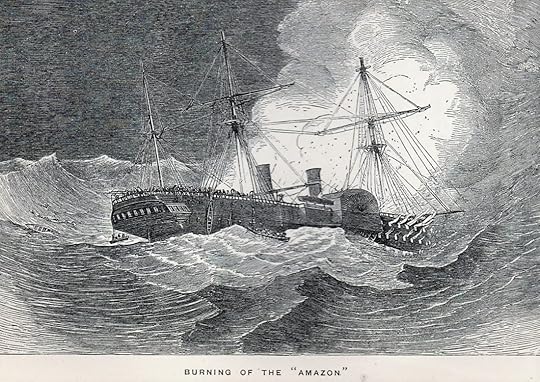

Every effort was made to prevent the flames extending aft. RMS Amazon carried nine boats and, remarkably for this period, had in theory sufficient accommodation in them for all passengers and crew, but they could not be safely lowered as the unreachable engines were still running and driving the vessel forward at some thirteen knots. The captain hoped that the ship’s movement would finally be arrested by exhaustion of the contents of the boilers but it transpired that when fire was first detected one of the engineers, fearing a boiler explosion, had opened the feed line from the water cistern to maintain a continuous feed. As the ship’s headlong charge continued, Captain Symonds ordered all boats to be kept fast until he should order lowering. By the time he did, when the spread of the flames was clearly unstoppable, the forward life-boats were already on fire. According to the 1877 source: “When this was discovered, all order and discipline seemed to disappear immediately, and instead of fortitude and resolution, a selfish desire for preservation entered almost every breast.” Amazon ablaze – contemporary illustration. Note boat hanging from davit.

Amazon ablaze – contemporary illustration. Note boat hanging from davit.

Unfamiliarity with the handling-equipment of the remaining boats now played its role – a sad indication of inadequate crew-training before departure. They were suspended from davits in the usual way but their keels were held in protruding cradles to prevent them swinging but the crew seemed unaware of this. Due to this at least three boats were flipped over as they were lifted and they dumped their occupants into the sea. The captain assisted in lowering the boats and when no more could be done went back to the wheel, took it from the steersman, and apparently perished at his post. The remaining boats did get away, the first to do so carrying sixteen people, including the Mr. Neilson previously referred to. It rescued a further five from a dinghy that had also got away – it was almost swamped and the occupants were bailing with boots – but the now empty dinghy drove into the stern of the lifeboat and wrecked her rudder.

The gale continued another three hours and all that could be done in the lifeboat was to keep her head to the wind by her oars and save her from swamping. The blazing RMS Amazon was visible in the distance, her masts toppling over in succession as the flames ate them away. A sailing vessel now appeared, heading out from the French coast, and passed within four hundred yards of the lifeboat, which hailed her. An answer was made by signal but she made no attempt to assist and continued on her course. Around dawn an explosion was seen to engulf the RMS Amazon. The funnels toppled over and then she herself disappeared. The lifeboat pulled for the French coast and in mid-morning was picked up by a British brig, the Marsden, which landed the survivors in France.

[image error]Burning Ship by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900) – how Amazon must have looked

RMS Amazon’s pinnace had also got way although on launching its occupants had been tipped into the sea. A few managed to clamber back on to the ship though a lady clutching an eighteen-month old child, a Mrs. M’Lennan, managed to keep hold of the boat until it was righted. It finally got away with sixteen occupants, including the Mr. Glennie mentioned earlier. An ex-Royal Navy seaman called Berryman (“a fine fellow”) trailed a portion of a spar as a sea anchor to hold the over-loaded boat’s head to. the wind and later, when the sea had calmed, hoisted Mrs. M’Lennan’s shawl between two boat-hooks as a sail. Mr. Glennie noted as he saw the RMS Amazon drew away that “a large hole was burnt out of her side immediately abaft the (port) paddlebox, part of which was also burnt. The hole was nearly down to the water’s edge and through it I could see the machinery.”

The pinnace survived into the morning, a leak that threatened to swamp her being stopped by Stone, the heroic engineer, and it steered for the French coast. “the men plying their oars lustily, and Mrs. M’Lennan, as she lay in the sternsheets, cheering them to their work.” Later in the day another vessel was sighted and the lady’s shawl was again put to good use for signalling. It proved to be a galiot, a small Dutch trading vessel called the Gertruda, which picked up the pinnace’s occupants and set her course towards Brest to land them. On the way more survivors were picked up from another boat.

A Dutch Galliot

The disaster had occurred on January 4th and it was not until the 15th of the month that it emerged that another thirteen persons had also been saved. They had been rescued by another Dutch vessel, the Hellechina, en route to Leghorn, which transferred them to a British revenue-cutter which took them to Plymouth. These survivors’ experiences were no less horrific than those of the others. The boat had been lowered safely from the Amazon, though a stewardess had fallen out and been drowned in in the process. Command was adopted by a Royal Navy officer, a Lieutenant Grylls, who had been a passenger on the Amazon and who had been active helping fight the fire previously. The boat was however leaking badly – “Fox, a stoker, stopped the hole by taking off his drawers and cramming them into it, keeping them in position for three or four hours by the pressure of his own body; and when seized by violent cramps was relieved by Durdney and Wall.” Another ship passed between them and the burning RMS Amazon, though without seeing them – though it must have seen the Amazon. One wonders if it was not the same vessel that had acknowledged the lifeboat’s signal but had carried on regardless. Gryll’s boat lacked oars and attempts were made to paddle her with the bottom boards. In the course of the morning it passed over the area where the RMS Amazon had gone down, strewn as it was with wreckage, but with no sign of bodies. Later in the day rescue came in the shape of the Hellechina.

Of the 162 people on the RMS Amazon only 58 survived. The loss was regarded as a national tragedy, with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert heading an appeal for support of widows and orphans. A subsequent enquiry was inconclusive as regards the origin of the fire. Though blame was placed by some on the engine bearings running hot – and indeed insufficient testing had been done prior to committing to the maiden voyage – this seems to have been unlikely since the engines continued to operate without seizing until the ship consumed herself. A further consideration was that the crew was freshly raised, knew little of each other and had not exercised together. The rapid spread of the fire was attributed to the use of much “Danzig Pine” in the construction, a timber known to be particularly inflammable. The single most significant contributory factor was most likely however to be the haste in which the ship had been rushed into service without adequate shake-down of both crew and machinery. The iron-hulled RMS Atrato by William Frederick Mitchell (1845-1918)

The iron-hulled RMS Atrato by William Frederick Mitchell (1845-1918)

And one lesson was most certainly learned. The next Royal Mail ship commissioned, the Atrato, was constructed of iron.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent Typical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post RMS Amazon – Ordeal by Fire, 1852 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 29, 2025

SMS Geier: a vulture under Two Flags, 1894 – 1918

SMS Geier: an odyssey Under Two Flags, 1894 – 1918

SMS Geier: an odyssey Under Two Flags, 1894 – 1918

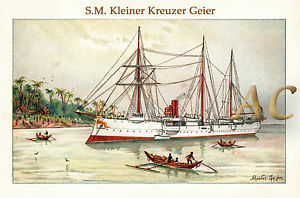

SMS Geier in tropical waters

When one thinks of the Imperial German Navy, the image that immediately comes to mind is of the mighty battle-fleet that confronted the Royal Navy at the start of World War 1. In the two decades prior to this, however, the most active service seen by the German Navy was by small ships in far-flung corners of the globe where Germany, a latecomer to the scramble for colonies, was constructing an overseas empire. One focus was on Africa, with very large territorial holdings in South-West Africa and East Africa, and smaller ones in Togoland and the Cameroons in West Africa. The other main focus was on the Western Pacific, with holdings in Northern New Guinea (“Kaiser Wilhelmsland”), the Bismarck Archipelago and several island groups whose names were to become familiar in World War 2. Germany has significant trading interests in China and this led in turn to establishment of a naval base on the Chinese coast at Tsingtao (modern Qingdao) to rival the British and Russian bases at Hong Kong and Port Arthur respectively. The distances involved in “policing” this vast area – essentially using naval power, whether for bombardment or by landing parties, to quell local unrest – required small and relatively unsophisticated vessels. These had to be capable of operating alone for extended periods, often far from reliable coal-supplies. They represented an ideal opportunity for young and ambitious officers to display initiative and seamanship in a way that would never be possible in the “big-ship navy” in home waters. This article tells of of one such humble vessel, SMS Geier.

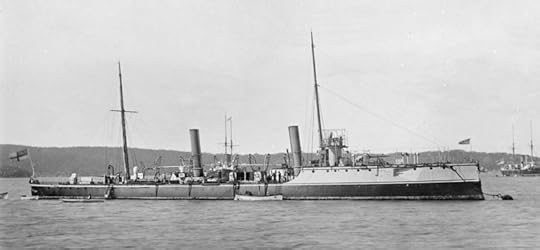

SMS Bussard, sister of the Geier and lead ship of the class

(With acknowledgement to the Deutsche-Schutzgebiete website)

Launched in 1894, SMS Geier, was a sophisticated ship for her size. One of the Bussard class of six, all named after birds (Geier meaning Vulture) she was an 1868-ton, 271-foot, twin-screw unprotected cruiser with a maximum speed of 15.5 knots. Such speed was rarely called for and endurance was more important in view of the distances she would operate over – she was consequently designed to steam on her bunkers for 3000 miles at 9 knots without resorting to her auxiliary sail-power. Since shore-bombardment was likely to be a requirement on occasion she was heavily armed for her size, carrying eight 4.1-inch guns and several smaller weapons. Given her expected duties it is surprising that she should have in addition two 14-inch torpedo tubes. Her crew amounted to 161, allowing her to land a potent and well-disciplined force should circumstances demand.

SMS Schwalbe, an immediate predecessor of Bussard Class and generally similar

Over the next two decades SMS Geier, like her sisters, was to see service in all the German colonial areas as well as in the Caribbean, where she evacuated German nationals from Cuba during the Spanish-American War. In 1900 she supported international efforts to suppress the Boxer Rising and she was to spend the next five years patrolling the China coast – a hotbed of piracy – and the German possessions in the South-West Pacific. A return to Germany for overhaul was the start of a deployment in European waters, including protection of German interests in the Mediterranean during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-12 and the Balkan Wars of 1912-13.

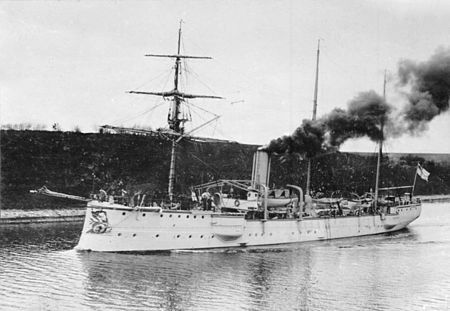

SMS Geier in her later years, when her sailing rig had been removed

(With acknowledgement to the splendid Kaiserliche-Marine website)

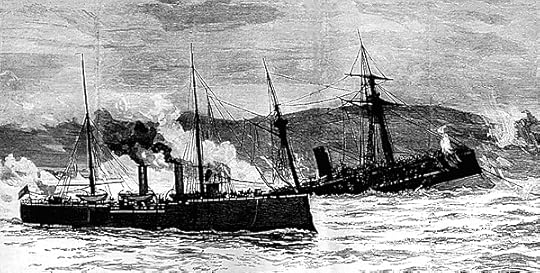

Thereafter SMS Geier was sent east again, but had not yet reached the German base of Tsingtao when the World War broke out in August 1914. She departed hastily from the British-held harbour of Singapore only days before Britain’s declaration of war. Obsolete, slow and with inadequate coal reserves, SMS Geier was now one of the German Navy’s nomads. Recognising that the Tsingtao base was untenable once Japan had also declared war on Germany, and was likely to capture this base quickly, the powerful German East Asia squadron, under the command of Admiral Graf von Spee, was already heading south-east across the Pacific in what proved to be a futile effort to return to Germany. SMS Geier tried bravely but hopelessly to follow the squadron, even capturing but not sinking a British merchant steamer on the way, a source of coal that helped extend her range. Her machinery was now at its limits however and by early October, though she had managed to escape the extensive British, Japanese and French forces scouring the Pacific, the game was up. Making use of her last coal supplies she crawled into Honolulu and surrendered herself for internment.

SMS Geier’s crew being marched by US troops into internment at Honolulu, October 1914

SMS Geier’s crew being marched by US troops into internment at Honolulu, October 1914

SMS Geier spent almost three inactive years at Honolulu (not a bad place for her crew to be interned!) but when the United States entered the war in April 1917 she was seized by the American government. Renamed the USS Schurz and hastily overhauled, she escorted a convoy consisting of three submarines to San Diego, then onwards through the Panama Canal to the Caribbean. Following further maintenance, she was allocated convoy duty in the Caribbean and off the United States’ East Coast. Here she was to meet her end. Rammed on 19th June 1918 off the Outer Banks of North Carolina by one of the freighters she was escorting, the Schurz sank quickly with the loss of one crew member killed and twelve injured.

It was a fate that could never have been predicted for SMS Geier when she had embarked on her busy and useful career in the Imperial German Navy almost a quarter-century before.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent Typical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post SMS Geier: a vulture under Two Flags, 1894 – 1918 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 22, 2025

de Loutherbourg: Naval Artist of the Age of Fighting Sail

Naval Artists of the Age of Fighting Sail, Part 1:Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg

Naval Artists of the Age of Fighting Sail, Part 1:Philippe-Jacques de LoutherbourgIn my non-fiction title Broadside and Boarding I describe the Royal Navy’s “cutting-out” of the French corvette Chevrette in 1801. I had stumbled on this incident through finding in an 1894 publication a most dramatic engraving depicting it. It was based on a painting by somebody referred to simply as “de Loutherbourg”. Given that the name was an unusual one for an apparently British artist I decided to find out more. Not only did I discover a quite fascinating and unexpected story, but the quest introduced me to a number of other artists of the 18th and early 19th Centuries who specialised in maritime subjects. Several of these painters had stories – and backgrounds – as unusual as de Loutherbourg’s and I’ll return to them in later blogs. It is through the eyes of these men that we have come to form our mental pictures of the Age of Fighting Sail. It came as a surprise to me to learn that severa of these painters, far from being studio-bound, had direct experience of life at sea, and even of combat, as I’ll tell in future posts.

de Loutherbourg’s “The Glorious First of June”

Lord Howe’s victory 1794

It was during the 18th Century that Britain gained the global-power status which was to be confirmed during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Through much of the period the performance of British land forces was patchy, and occasionally disastrous. Where at all possible Britain avoided land campaigns and instead used the wealth accruing from her maritime trade to subsidise European powers – such as Prussia – to do the fighting on her behalf. In establishing commercial as well as naval supremacy it was the Royal Navy which was to prove the decisive weapon, one unrivalled not only as regards power and size but as regards professionalism and bloody-minded dedication to victory. This fact was widely recognised throughout British society and, even if there was reluctance to provide adequate remuneration and acceptable terms of service, the Navy and its personnel were held in high esteem. Songs such as Rule Britannia (1740) and Heart of Oak (1760), both still loved and heard, bore witness to this. It was therefore no great surprise that painters specialising in naval subjects should find a ready market for their paintings with the more affluent, and for engravings of them for the less prosperous. It is in this context that de Loutherbourg and other artists like him should be seen.

de Loutherbourg in later life

Of Polish extraction, Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg was born in Strasbourg in 1740 and at the age of 15 was apprenticed in Paris to the eminent and fashionable artist Charles-André van Loo. His talent was quickly recognised and in 1767 he was elected to the French Academy, even though below the age normally set for this. His range of subjects was wide and already included sea storms and battles as well as landscapes. At an early stage however he was fascinated by the opportunities offered by stage productions and he experimented with a model theatre to produce effects such as running water, achieving this with clear sheets of metal and gauze.

de Loutherbourg’s increasing fascination with the theatre led him to accept an offer by David Garrick, the greatest actor of the day (who wrote Heart of Oak ) to move to London. Here, at the Drury Lane Theatre, de Loutherbourg designed scenery, costumes and, most significantly, stage effects of ever-greater sophistication. The latter depended heavily on coloured lantern-slides and lighting effects. de Loutherbourg was to spend the rest of his life in Britain, anglicising his name to Philip James. It is likely that, like many Frenchmen of his background, he would have found his country a most uncongenial place during and after the revolution.

de Loutherbourg’s “The Battle of Camperdown 1797”

British victory over the Dutch fleet

In the midst of his theatre activities de Loutherbourg continued painting, encouraged by the friendship of Britain’s premier artist, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Though his range continued to be wide, it was de Loutherbourg’s naval paintings which were to be most prestigious. Several were commissioned to commemorate great naval victories such as the Glorious First of June (1794) and are now in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Not surprisingly, given his links to the theatre, these paintings are intensely dramatic. He made no attempt the fact that a degree of licence was taken for the sake of effect and in the prospectus for the engraving of his painting of the Battle of Camperdown (1797) it was frankly stated that:

“Mr. Loutherbourg has availed himself of the privilege allowed to painters, as well as epic and dramatic poets, of assembling in one point of view such incidents as were not very distant from each other in regard to time. These incidents have been associated as fully as the limits of the distinct picture would admit; and although many principal events, in which particular ships distinguished themselves, may not have been brought forward, yet the artist is satisfied that the officers of the navy will be indulgent for whatever it was not practicable to introduce; especially as it has been Mr. Loutherbourg’s plan to compose his pictures with an adherence to the principles of the art not usually consulted in marine painting.”

“The cutting-out of the Chevrette, 1801″

It is notable that in the case of the picture that first roused my interest in de Loutherbourg, “The Capture of the Chevrette”, the drama may seem extreme, yet the work was based on sketches made by officers who were actually present, and many of the faces are portraits of them. Given that his career had taken off under the Ancien Regime in France it is interesting to note that he was to live on to be fascinated by the very different world of the industrial revolution and to find it a challenging subject.

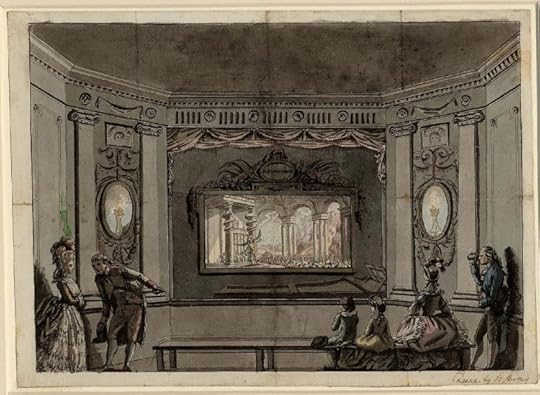

de Loutherbourg’s 1801 “Coalbrookdale by Night”: iron foundries in action

de Loutherbourg continued to be interested in the technology of spectacle and one could well image that had he been born a century and a half later he would have flourished as a movie-director in the Abel Gance mould. His most notable achievement in this area was his invention of the “Eidophusikon”(Image of Nature), a small mechanical theatre that used lighting, stained glass, mirrors and pulleys to achieve spectacular effects. Shows were given to audiences as large as 130 and the subject matter was – as could be expected – spectacular in the extreme. The most remarkable appears to have been the scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost in which Satan marshals his followers on the shored of a lake of fire and the rising of the Palace of Pandemonium. Impressive and popular as it was, the venture could not justify its costs and it had to close, leaving de Loutherbourg to return to more conventional work. One can well imagine how, today, he would have gloried in the possibilities offered by CGI.

de Loutherbourg’s “Eidophusikon”

de Loutherbourg died in 1812 and though his career had been a very unusual one it was not the only one in which great maritime art was to emerge in this period from unlikely backgrounds. I’ll return in later blogs with some very surprising instances.

p.s. Some years ago I was delighted to encounter one of his paintings, “The Hermit” in the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest:Britannia’s InnocentTypical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post de Loutherbourg: Naval Artist of the Age of Fighting Sail appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 15, 2025

The Fate of Zeppelin L-19, February 1916

It is now over a century since bombing from the air became an integral feature of warfare, with civilian populations being at the mercy, at best, of collateral damage and, at worst, of deliberate targeting. It is therefore all the more difficult to comprehend the indignation and loathing aroused by the first deliberate bombing of civilian targets early in World War I. The large Zeppelin forces fielded by Imperial Germany’s separate Army and Navy organisations began the practice. They were used to strike British towns and cities, apparently in the hope of arousing widespread panic among the civilian population and thereby cutting into industrial production. The physical results were wholly disproportionate to the demands made on strategic resources (notably aluminium) and the most concrete single result was to give a gift to Allied propagandists who could label the Germans “baby killers” since children were inevitably among the victims. Imposing and ominous sights these airships might have been, but their load-carrying ability was limited and they were underpowered in relation to the vast forces imposed on them by weather. If they could be detected by defending aircraft – and that was a major “if” at night, and even in daytime, in those pre-radar days – these hydrogen- laden airships were spectacularly vulnerable to fixed-wing aircraft firing incendiary bullets. Adding to these drawbacks was the difficulty of navigation and inability to locate even city-sized targets with any hope of success – the necessary technology did not emerge until the early years of World War II. The vulnerability and essential uselessness of these airships as an offensive weapon are epitomised by the fate of Zeppelin L-19 in February 1916, a case that also raised serious ethical issues.

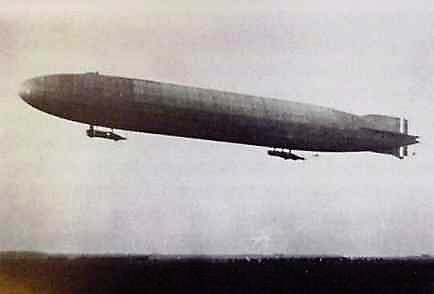

L-19 in flight

L-19 was a 536-feet long rigid airship powered by four 240-Hp Maybach petrol engines which gave it a maximum speed in still air of 60-mph. Any headwind would obviously cut into this speed and winds from the flank would cause drift off course. Her bomb capacity was significant for her day – rated at 3530-lbs (just over one and a half tons.) She entered service German Navy service in late November 1915 and in the next two months made reconnaissance flights over the North Sea. On 31st January 1916 she joined eight other airships the largest air-raid yet mounted on Britain. Leaving the base at Tondern in Schleswig at noon she headed westwards across the North Sea, the objective being “targets of opportunity” in England, including Liverpool, if it could be reached. Heavy rain and snow were encountered and the Zeppelins crossed the English coast individually some six to seven hours after departure, meaning that they were by then flying in darkness. The L-19 was the last of the force to arrive, passing over Norfolk and locating Burton-on-Trent some 140 miles further west in the English Midlands. Here she dropped part of her bombs before flying south-west towards Birmingham where the remainder were unloaded. It was possible that the commander did not know where he was – the crew of one of other Zeppelins that reached Burton believed that they had bombed Liverpool, in actuality far to the North West. The damage inflicted by the L-19 was minimal – a public house destroyed, some farm animals killed, but no people injured. The raid as a whole killed 61 people on the ground and injured 101. The effect on Britani’s ability to wage war was undiminished but anti-German feeling would be raised to a new pitch.

Inside a Zeppelin gondola – illustration from 1917

The L-19’s tragedy was now just beginning however. She had problems with her engines – a new design that was showing signs of unreliability in service – and indeed more than half of the other airships involved in the raid had such troubles also. As she headed back eastwards over England and out into the Southern North Sea, the L-19 signalled by radio the results of her bombing and requested a position-fix by radio-triangulation. By the time of her final signal, at 0400 hours on 1st February, she reported problems with her radio and that three of her four engines were out of action, leaving her wholly at the mercy of the weather. She was then some 20 miles north of the Friesan Island of Ameland, off the northern Dutch coast. Some while later she drifted across Ameland itself and Dutch forces there, though neutral, fired on her – ineffectively – with rifles. The L-19 seems to have remained powerless through the day that followed and a southerly wind carried her northwards. Sometime during the nights of 1st – 2nd February the L-19 came down in the sea. The captain dropped a bottle – it contained a report of the airship’s predicament and letters to his family. It was only picked up long afterwards. Without information on L-19’s position, it is not surprising that German efforts to locate her proved futile.

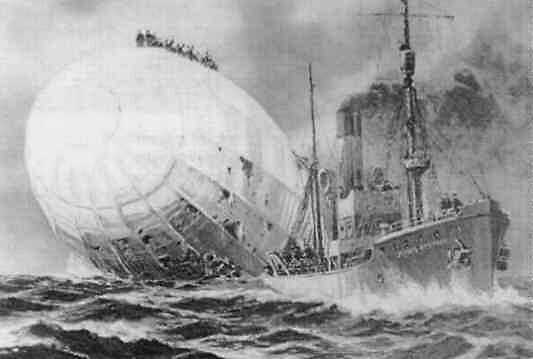

Morning 2nd February, rescue apparently at hand – contemporary illustration

The airship was still afloat, with her sixteen-man crew clustered on top. They had fired flares during the night and these drew the attention of a British fishing vessel, the civilian King Stephen steam-trawler, commanded by a Skipper William Martin (1869–1917). Hope of rescue rose as the English-speaking German airship captain hailed the King Stephen and asked for his crew to be taken aboard. Skipper Martin of the King William refused, on the grounds that his own unarmed nine-man crew could be overpowered and his vessel taken to a German port. Pledges by the German captain of honourable behaviour and offers of financial reward did not shake Martin’s resolve. He did however undertake to report the airship’s location to any British warships he would encounter. He was to meet none and the incident was not reported until the King Stephen docked at the fishing port of Grimsby on the British East coast. The weather had been worsening as she left the L-19. No trace of the airship was found thereafter by searching British warships though several more messages in bottles and the body of a single crew member were later washed up.

The King Stephen sails away – note crew on top of L-19 – by German artist Adolf Bock

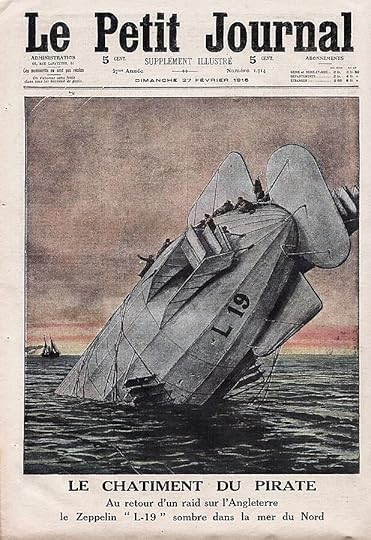

L-19 as imagined by a French magazine

Skipper William Martin’s dilemma was a terrible one, and, on balance, it is hard to condemn his decision to leave sixteen men to their fate provided he reported their location. Even allowing for anti-German “baby killer” propaganda, concern for his crew offered an arguable justification. Pro and contra views were taken in Britain and Martin received mail both praising and excoriating him. The Anglican bishop of London was a stalwart supporter of his action. Martin died of a heart attack the following year, brought on perhaps by the controversy. The incident proved counterproductive in propaganda terms, allowing Germany to counter “baby killer” accusations by referencing the L-19’s men being left to their death when deliverance was at hand.

The King Stephen / L-19 incident may not however have been as straightforward as portrayed at the time. Investigation of Admiralty archives in the early 1960s, and interviews with the trawler’s two surviving crew members, indicated that the position reported by Skipper Martin may have been deliberately incorrect, resulting in the Royal Navy’s futile search efforts being concentrated in a wrong area. The reason appeared to be that he had been fishing in a forbidden zone and that he did not want to reveal the fact. The King Stephen’s own remaining life was to be short one – taken into Royal Navy service she was sunk twelve weeks after L-19 had gone to the bottom.

Over a century later it is difficult to judge or to condemn any of the parties involved – unless Skipper Martin was in fact lying. Total war, with all its horrors, was a new reality and hard decisions would lie ahead in land, sea and air combat. The ultimate responsibility for the fate of the L-19’s crew – dedicated professionals doing a difficult job – lies far from them and rests forever on other shoulders.

Britannia’s Gamble Like all volumes of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Gamble, may be read as a standalone or as chronologically part of the series.

Like all volumes of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Gamble, may be read as a standalone or as chronologically part of the series.

It’s 1884 and a fanatical Islamist revolt is sweeping all before it in the vast wastes of the Sudan and establishing a rule of persecution and terror. Only the city of Khartoum holds out, its defence masterminded by a British national hero, General Charles Gordon. His position is weakening by the day and a relief force, crawling up the Nile from Egypt, may not reach him in time to avert disaster.

But there is one other way of reaching Gordon…

A boyhood memory leaves the ambitious Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish no option but to attempt it. The obstacles are daunting – barren mountains and parched deserts, tribal rivalries and merciless enemies – and this even before reaching the river that is key to the mission. Dawlish knows that every mile will be contested and that the siege at Khartoum is quickly moving towards its bloody climax.

Outnumbered and isolated, with only ingenuity, courage and fierce allies to sustain them, with safety in Egypt far beyond the Nile’s raging cataracts, Dawlish and his mixed force face brutal conflict on land and water as the Sudan descends into ever-worsening savagery.

And for Dawlish himself, one unexpected and tragic event will change his life forever. . .

Extract from a review of Britannia’s Gamble in “Historical Novels Review” – November 2018:

“Some authors have so researched their period that they seem to live the events, the surroundings, the details they describe. Antoine Vanner is one of these. He breathes such life into his narrative that you would think him a correspondent in the 1880s Sudan writing what he sees, rather than a man of today looking back.”

Available in paperback and Kindle formats. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra charge. Details for purchase below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Fate of Zeppelin L-19, February 1916 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 1, 2025

HMS Wasp: An accidental victim of Ireland’s “Land War”, 1884

Though it is likely that many in her crew disliked the task assigned them it is fair to say that the mission on which HMS Wasp was engaged at the time of her loss was one of the most inglorious ever undertaken by the Royal Navy.

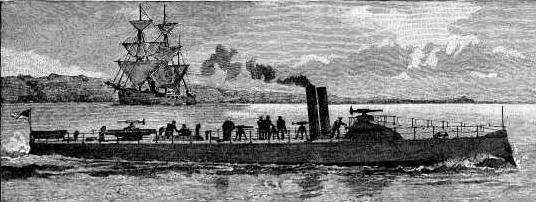

HMS Wasp under sail and steam

Built in the 1880-82 period, HMS Wasp was one of the 11-strong Banterer Class of gunboats. They were of composite construction, based on an iron frame but planked with wood, thus facilitating fitting of anti-fouling coppering. This was an important, if not to say essential, feature for ships which were to see considerable colonial and tropical service. They were 125 feet long, and displaced 465 tons. A single-screw 360 HP compound steam engine gave a top speed of a mere 9.5 knots but for the sort of service such vessels were intended endurance was a more important consideration than speed. A barquentine rig was carried on three masts to supplement the engine, or indeed to replace it on long voyages to conserve coal. For their size these vessels carried a heavy armament – two 6-inch 64-pounder muzzle-loading rifles, supplemented by two 4-inch breech-loaders as well as small-calibre Maxims, Gardners or Gatlings. The unsophisticated 6-inch weapons, were effective enough for shore bombardment and the vessel’s small size and sailing ability made them useful for colonial duties, for which armour was not required. The crew consisted of 60 officers and men. This is an indication of just how many men were employed in the Navy at this time – this single class of small gunboats alone required almost 700 men to crew them.

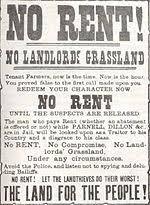

HMS Wasp – looking pristine, probably soon after commissioning

After commissioning, HMS Wasp was based at based in Queenstown (now Cobh) in County Cork in the south of Ireland, then still under British rule. Her duties appear to have fishery and lighthouse inspections or other official duties around the entire Irish coast. These were difficult and bitter years in Ireland, where the long and often violent social unrest known as the “Land War” was raging. Small tenant farmers were, at last, confronting the landlords – almost exclusively Anglo-Irish and different from them in religion and political affiliation – on issues of tenure and fair rent and were demanding distribution of land to them. Particular bitterness was felt towards absentee landlords who lived well elsewhere on the rents and who ploughed little back into the betterment of local society. Though the overall poverty of the country was not as extreme as during the Great Famine period of the 1840s, life was still miserably deprived for many in the rural population. A poor harvest could mean inability to pay rent and such failure frequently resulted in eviction of entire families, followed by demolition by battering ram of the dwelling to prevent its further occupation. Such evictions saw deployment of armed police to protect the bailiffs and demolition gangs – photographs of such occasions are heartrending in their pathos. Feelings ran high and there was a high level of violence on both sides. It was in this period that the “Boycott” weapon came to have its present meaning since the process was named from action used against a Captain Boycott, the agent of a particularly unpopular landlord.

After commissioning, HMS Wasp was based at based in Queenstown (now Cobh) in County Cork in the south of Ireland, then still under British rule. Her duties appear to have fishery and lighthouse inspections or other official duties around the entire Irish coast. These were difficult and bitter years in Ireland, where the long and often violent social unrest known as the “Land War” was raging. Small tenant farmers were, at last, confronting the landlords – almost exclusively Anglo-Irish and different from them in religion and political affiliation – on issues of tenure and fair rent and were demanding distribution of land to them. Particular bitterness was felt towards absentee landlords who lived well elsewhere on the rents and who ploughed little back into the betterment of local society. Though the overall poverty of the country was not as extreme as during the Great Famine period of the 1840s, life was still miserably deprived for many in the rural population. A poor harvest could mean inability to pay rent and such failure frequently resulted in eviction of entire families, followed by demolition by battering ram of the dwelling to prevent its further occupation. Such evictions saw deployment of armed police to protect the bailiffs and demolition gangs – photographs of such occasions are heartrending in their pathos. Feelings ran high and there was a high level of violence on both sides. It was in this period that the “Boycott” weapon came to have its present meaning since the process was named from action used against a Captain Boycott, the agent of a particularly unpopular landlord.

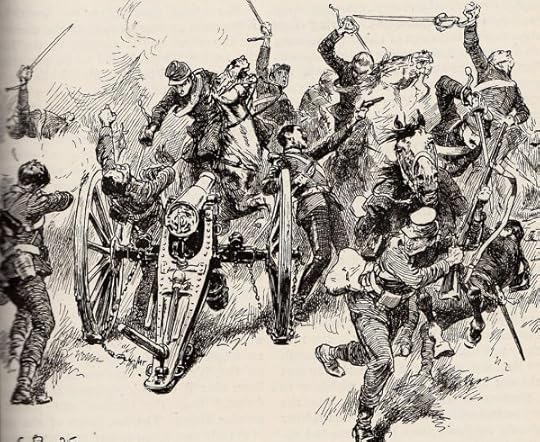

Demolition of tenant’s house by battering ram following eviction in the 1880s to prevent reoccupation. (Note that the tenants attempted to defend themselves by stuffing gorse in the windows as a primitive alternative to barbed wire)

A landlord or his agent overseeing eviction with police support. Note the lady on the horse to the right viewing the spectacle. Scenes like this sowed seeds of bitterness that ultimately led to independence.

Poverty was possibly at its worst on the small islands off the North and West Coasts. The most extreme case was perhaps Inishtrahull, a tiny speck which is the most northerly island of all. all. Six miles from the mainland, it is the most northerly point in the Irish Republic. Though uninhabited now, the last residents having left in 1929, the island supported several families in the 1880s as well as a lighthouse.

Inishtrahull – The Irish Republic’s most northerly point. Photograph by author Kevin Dwyer http://blog.discoverireland.com/2010/09/the-joys-of-aerial-photography-over-ireland/

The battering ram’s work: a house left uninhabitable post-eviction. For many of those cast on the roadside, the best option would be to go to the United States if they could raise the money.

Difficult as life on Inishtrahull must have been, rent still had to be paid for the pitiful plots of land, basic humanity not always being a characteristic of the landlord class. In September 1884 three families on Inishtrahull were unable – or perhaps unwilling – to pay their rents and an example had to be made of them. HMS Wasp, then at Westport on the West Coast, and under the command of the 39-year old Lieutenant J. D. Nicholls, was accordingly ordered to Moville, the mainland village closest to the island. Here she was to take on board the bailiffs, police and other officials who would carry out the evictions. One can well imagine distaste among many of the gunboat’s crew for this task, but orders were orders.

In the early hours of September 22nd HMS Wasp was following a course that took her between the northwest coast of Donegal and the rocky coast of Tory Island, nine miles offshore. The vessel was under sail only, and the boiler was not fired, so that the advantage of improved maneuverability which steam would provide# was not available. Given this fact it was surprising that HMS Wasp would have followed the course that took her to the east of Tory Island, between it and the mainland, rather than gaining greater sea room had she sailed west of it. It also appears that Nicholls and other officers may have been sleeping.

HMS Wasp on the rocks beneath the Tory Island lighthouse

HMS Wasp on the rocks beneath the Tory Island lighthouse

At 0345 the Wasp ran onto rocks directly under the Tory lighthouse. She sank within 30 minutes with the loss of fifty of the crew, leaving only six survivors. Only the mastheads were left protruding from the water and it was to these that the survivors clung. They were rescued by the islanders and sheltered until they could be picked up four days later by another ship assigned to Irish duty, HMS Valiant, which took them to the mainland. Valiant was a large Hector-class armoured frigate of 7000 tons, this class being smaller versions of HMS Warrior, which can be seen in Portsmouth today. A monument was erected in the churchyard of St. Ann’s, Church of Ireland Church, Killult, on the mainland coast opposite Tory Island, where some of the sailors are buried.

A Royal Navy enquiry subsequently found that HMS Wasp was lost “in consequence of the want of due care and attention…” but no one person was singled out for blame, possibly in view of the deaths of the officers and the distress it would inflict on their families. Apart from the questions raised about what was happening on board HMS Wasp, much debate since has focused on whether the Tory light was on or off before the vessel struck the rocks. What is known is that the light was certainly on after the collision. However, the question remains – was the light on when HMS Wasp was nearing Tory? Did animosity towards the British rulers of Ireland at the time and the duties in which HMS Wasp was sometimes involved cause the light to have been extinguished deliberately when the gunboat was passing through the channel between the island and the mainland?

Another less likely explanation, but one which became popular in the area was that HMS Wasp was the victim of a curse laid on it via “Cursing Stones” on the island. These are Neolithic remains involving individual stones resting in a larger cup-shaped one. Of all the speculative explanations of the tragedy, this is the one that can most easily be ruled out!

Dawlish Chronicles novel: Britannia’s Rule 1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

1886: Captain Nicholas Dawlish, commanding a flotilla of the Royal Navy’s latest warships, is at Trinidad when news arrives of a volcanic eruption on a West Indian island. The situation is worsening and only decisive action can avert massive loss of life. He races there with his ships to render help. His enemy will be an angry mountain, vast in its malevolent power, a challenge that no naval officer has faced before.

But Dawlish’s contest with the volcano is just the prelude to a longer association with the island. Its sovereignty is split – a British Crown Colony in the west, and in the east an independent republic established seven decades earlier by self-emancipated slaves. When wrenched from France through war, both seemed glittering economic prizes. Now they are impoverished backwaters where resentment seethes and old grudges fester. For many, the existence of a ‘black republic’ is resented, an affront to be excised. In France, a man of limitless ambition, backed by powerful interests, sees the turmoil as an opportunity that could bring him to absolute power. And, if he succeeds, perhaps trigger war in Europe on a scale unseen since the fall of Napoleon.

Through this maelstrom, Nicholas Dawlish must navigate a skillful course. Political concerns complicate challenges that can only be resolved by ruthless guile and calculated use of force. Lacking direct support from the Royal Navy, Dawlish must fight some of the most vicious battles of his career with inadequate resources and unlikely – and unreliable – allies.

Available in Paperback and Kindle (also readable on smartphones and tablets via Kindle App).Kindle Unlimited Subscribers can read it, or any of eleven other Dawlish Chronicles, at no extra cost.For more details and for ordering, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au For amazon.caThe Dawlish Chronicles series – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post HMS Wasp: An accidental victim of Ireland’s “Land War”, 1884 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 17, 2025

Almirante Lynch, 1891 – sea combat in the Pacific

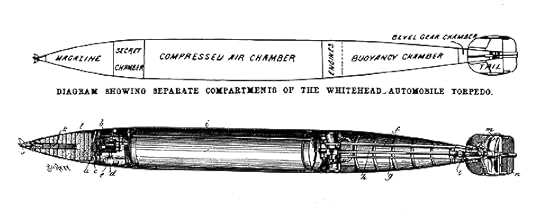

The appearance of the successful self-propelled torpedo occurred in the mid-1870s, at the same time as light, efficient steam engines allowed the development of a new type of warship, the torpedo boat. Fast by the standards of the time – typically 18 to 20 knots – and cheap to build, these small vessels carried a weapon that, for the first time, allowed attack below the waterline. To this, even the most heavily armoured ships were vulnerable.

14″ Whitehead Torpedo – late 19th Century. The warhead had not yet the domed shape that would later be standard

Some nations, such as France, which remained a possible enemy for Britain in any war likely at this time, saw flotillas of such gunboats as an economic and effective way of countering the numerical advantages of a larger navy. In the French navy this concept was central to the strategy advocated by the so calledJeune École, and other nations, including many smaller ones, followed suit. Swarms of torpedo boats were believed capable of swamping the onboard defences of their targets and, as when the airborne attack emerged as a threat in the 1920s, many came to believe that the day of armoured units, particularly battleships, was over. Though early torpedo boats were suited to inshore use only – as for defence of ports and naval bases – size and sea-keeping ability increased through the 1880s, thus allowing more aggressive deployment. Typical of such larger boats was the Falke, built by the British company Yarrow for the Austro-Hungarian Navy in 1885 and carrying two torpedo tubes and two 37mm quick-firing guns. 135 feet long and displacing 100 tons, she was capable of 22 knots at a time when the fastest armoured ships were lucky to make 16.

Falke of the Austro-Hungarian Navy 1885

Protection of heavy units against torpedo boat attack consisted of what today would be regarded as both “point defence” and “area defence”. In the former case the objective was to destroy any attacker that had come close to an individual ship. Effective weapons were available for this, in the form of Gatling, Nordenvelt and Gardner semiautomatic weapons of up to one inch calibre which were well capable of tearing a lightly constructed torpedo craft apart in a hail of fire. The solution to this was to swamp the target ship by simultaneous attack from different directions. Countering this meant area defence by craft that were capable of detecting and breaking up such swarms of attackers, ideally long before they could reach heavier units.

HMS Niger of the Alarm class – became a minesweeper in 1909

Torpedoed by U-12 off Deal on 11th November 1914

Given that the Royal Navy had the most to protect, it was not surprising that it was the first navy to develop a counter to the threat. This was in the form of the “torpedo gunboat”, essentially a small cruiser armed both with torpedoes and with heavier guns than those of any torpedo boat, and were of a size that guaranteed superior sea-keeping capability. The Royal Navy was to build 33 such units between 1885 and 1894. The Alarm class of the late ‘80s was perhaps typical of the type as a whole. 230 feet long and of 810 tons, she carried five torpedo tubes, which gave a useful offensive capability against larger ships, and a heavy gun armament for dealing with torpedo craft – two 4.7 inch guns, located fore and aft, as well as smaller quick-firers and Gardner semi-automatics. Like others of the type the eleven Alarms were handsome ships, all the more when seen in black, white and buff Victorian livery.

HMS Boomerang of the Sharpshooter class

Any torpedo boat that came within range of such a unit was to have only short life expectancy. The problem was however to get within range for the typical torpedo-gun boat was slower by two to three knots, and significantly less maneuverable than the craft they were designed to hunt down and kill. By the mid ‘90s this fact had been amply demonstrated in exercises and another solution was needed to counter the torpedo boat threat. The answer was to be a “super torpedo boat”, larger and faster and carrying heavier armament, becoming in the process a “torpedo boat destroyer” and the progenitor of the ever larger destroyers that were to play such key roles in both world wars.

The torpedo gunboats were quickly made obsolete by these new destroyers though, as well-built craft some were to survive in secondary roles, as depots, patrol craft or minesweepers and play useful roles in the Great War, being broken up in the early 1920s. This eclipsing of the torpedo-gunboat by the more spectacular destroyer as resulted in them having received a bad press over the years, and they are usually regarded as a misguided concept and a technical dead end. This evaluation, though harsh, is correct.

Depressing as this record of mediocrity might be, one torpedo gunboat was to prove very successful, and indeed make naval history in an unlikely location – Chile.