Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 4

November 13, 2024

Another Novel Release Date

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Another Novel Release Date appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

Novel Release Date

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Novel Release Date appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

Audio Book Format Also

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Audio Book Format Also appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 5, 2024

Ramming of HMS Prince George 1903

The Ramming of HMS Prince George by HMS Hannibal, 1903

The Ramming of HMS Prince George by HMS Hannibal, 1903For some five decades from 1866, when the naval battle of Lissa, when victory was secured by the Austro-Hungarian fleet over its Italian enemy by means of ramming, naval architects were to be fixated on designing ram bows into warships of all sizes. They ignored the fact that victory at Lissa was possible only because of short effective gun ranges and that this factor was soon obviated by progress in gunnery and torpedoes. The ram, as a design feature, was to prove more dangerous to friends than to enemies and there were major disasters occasioned by it. There was however one serious ramming in which disaster did not follow, as a result of prompt and efficient damage control. This instance, which involved two British Pre-Dreadnoughts, HMS Hannibal and HMS Prince George, offers interesting insights into the efficiency of the Royal Navy at the start of the 20th Century.

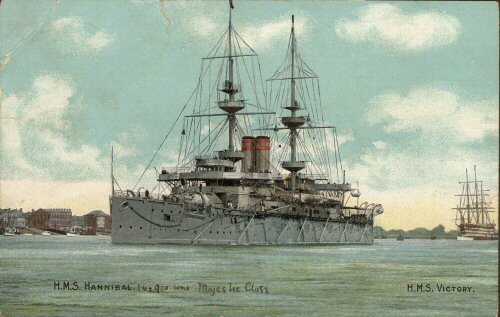

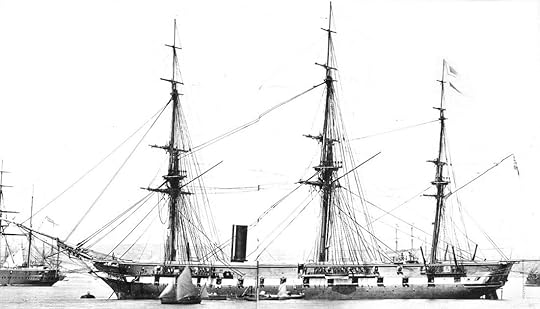

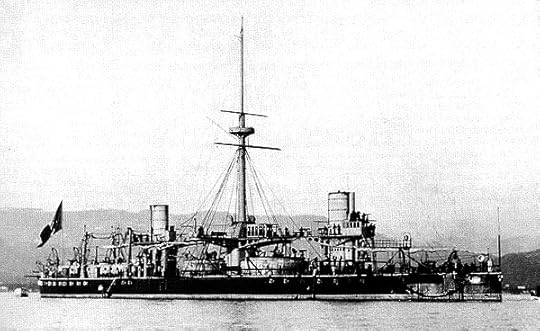

HMS Hannibal – contemporary postcard

HMS Hannibal and HMS Prince George both belonged to the nine-ship Majestic class which was brought into service in the late 1890s. These 16,000-ton, 421-feet long vessels were among the most powerful afloat when first commissioned. Capable of steaming at maximum 16 knots, and with a crew of 672, they could each bring into action four 12-inch and twelve 6-inch guns as a well as many smaller weapons and five 18-inch torpedo tubes. Heavily armoured, they had one great vulnerability that would apply to all ships afloat until the invention of radar – they were blind in darkness or fog.

On the night of 17th October 1903 Britain’s Channel Fleet, under the command of Admiral Lord Charles Beresford (1846-1919), was engaged in manoeuvres without lights off Cape Finisterre, on teh North-Western tip of Spain. The force included both Hannibal and Prince George . The idea of such monsters manoeuvring in close proximity in near total darkness held the seeds of disaster – and so it proved. At 2130 hrs two off-duty midshipmen of the Prince George were playing cards in the ship’s gunroom, close to the stern when, without warning, the bows of the Hannibal’s bows came crashing through. Both young men escaped without injury but the damage was serious.

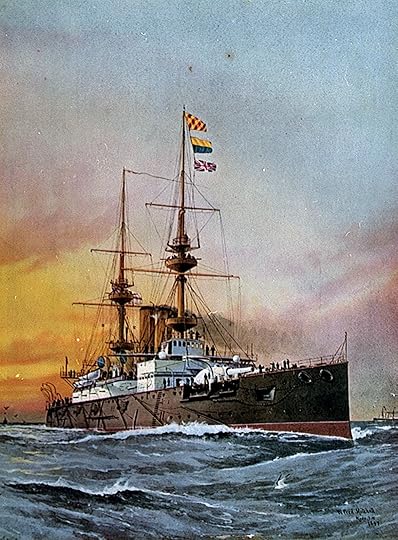

HMS Prince Geroge in splendid Victorian livery

Hannibal instantly signalled, “Have collided with the Prince George,” by flashing lights – radio had also not yet made its appearance – while measures were put in hand to assess the full extent of the damage. By 2210 hrs Prince George could signal that there was a large hole in her gun-room, and that the submerged steering compartment were full of water. Hannibal had impacted at a speed of nine knots, and had caused an 18-inch deep indentation in Prince George’s side. It was in the form of an inverted pyramid, the apex at the level of the protective steel deck, the base level with the upper deck, 24 feet in height, and over 6 feet across at the upper deck, and diminishing to a crack at the apex. In the centre of the indentation was a triangular rift, over three feet long and 18-inched wide at the top.

Beresford

Admiral Beresford – a controversial figure, but never one to fail to rise to a challenge – crossed to Prince George, examined into the damage and made a general signal to the Fleet to order all hand-pumps and 14 foot planks to be sent on board. Prince George’s Captain F. L. Campbell had ensured maintenance of perfect discipline. A collision mat had been placed over the injury and the crew were already working with hand-pumps and baling out with buckets.

The most serious problem was however that the rudder was out of action due to the steam-lines leading to its operating mechanism being full of water. The helm was however amidships and had the rudder jammed to starboard or to port, the fine-manoeuvring that would follow later would have been impossible. The bulkheads adjoining the flooded compartments, and all horizontal water-tight doors, were shored up with baulks of timber. Water was still entering however because, owing to the indentation in the side of the ship, the collision mat did not fit tightly.

The approach to Ferrol – the inlet’s intricacy is obvious

(with thanks to Google Earth)

Beresford ordered the fleet to proceed to the nearby Spanish naval base of Ferrol. This lay about half-way up a narrow ten-mile inlet which was known for sunken rock hazards. An earlier British battleship, HMS Howe, had gone aground there in 1892 and had been rescued only with difficulty, and three lesser ships had suffered the same indignity thereafter. Beresford was taking no chances and he sent a vessel ahead to mark known rocks by buoy. A message was also conveyed to the Spanish authorities to explain the situation.

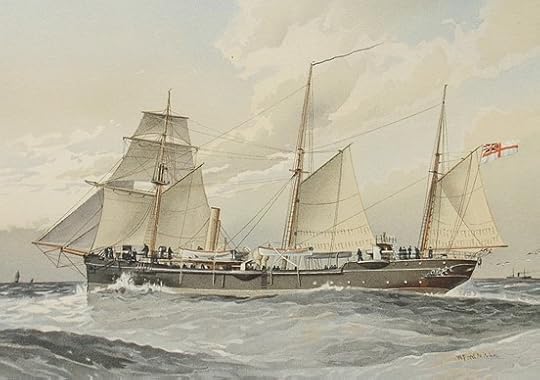

Captain Campbell of the Prince George was now responsible for a very impressive piece of seamanship. He brought the ship up the tortuous channel to Ferrol harbour, without benefit of a rudder and steered by engines alone. This involved proceeding a slow speed, sometimes with both screws ahead, sometimes astern, sometimes one ahead and the other in reverse, according to which way it was necessary to turn his ship’s head. His handling was faultless, despite the fact that during these operations Prince George was heavily down by the stern, drawing 25 feet forward and 34 feet aft. Her stern walk was flush with the water.

HMS Prince George, painting by W.F. Mitchell, 1897

Prince George arrived in Ferrol harbour on 18th October. Divers and working parties were sent to her from all the other ships, and the Spanish Government made dockyard resources available. The working parties laboured day and night for the next five days. On 19th October the armoured cruiser HMS Hogue, was placed alongside the Prince George to make her salvage pumps available.

In his memoirs Beresford gives a fascinating insight into the measures now undertaken. The first objective was to prevent further flooding and to pump out the water already on board. He wrote that “Mats were made of canvas, ‘thrummed’ with blankets, and these, with collision mats cut up, and shot mats’ were thrust horizontally through the holes in the ship’s side and wedged up so that the ends of the mats projected inside and out; and the moisture, causing them to swell, closed up the holes.”

In parallel with this a cofferdam was being constructed against the side of the ship, around the rupture. This was a formed a chamber “which was filled up with all sorts of absorbent and other material, such as seamen’s beds, blankets, rope, hammocks, pieces of collision mats, gymnasium mattresses, cushions, biscuit tins, etc. Thus the coffer-dam formed a block, part absorbent and part solid, wedged and shored over the site of the injury.” Beresford also recorded that the work involved 24 engine-room artificers, 24 stokers, 88 carpenter ratings, 27 divers and 16 diver-attendants. By 1903 a ship’s “carpenter” was no longer concerned with maintenance of wooden structures but with the ship’s steel framework and plating. The divers were drawn from all ships in the fleet and they, like the other staff involved, operated on a three-watch system so that the work proceeded night and day. While this was in progress over 145 tons of ammunition and stores were shifted in order to trim the ship. The total cost of the stores purchased locally at Ferrol was £116. 2s. 4d – one can only be impressed by the exactitude of the two shillings and fourpence!

On 24th October, just one week after the collision, Prince George departed Ferrol for Portsmouth, escorted by the armoured cruiser HMS Sutlej. The integrity of the cofferdam was attested by the fact that despite rough weather being encountered the total amount of water shipped during the voyage was estimated at one gallon.

SMS Friedrich Carl

SMS Friedrich Carl

Once repaired at Portsmouth Prince George was soon back in service. She seems to have been accident-prone as she suffered minor damage in another collision, this time with the German armoured cruiser SMS Frederick Carl at Gibraltar in 1905. She also suffered moderate damage in 1907 when she broke free from her anchorage at Portsmouth and struck the new armoured cruiser HMS Shannon. She was to prove lucky however in WW1 when she survived hits by Turkish shells at the Dardanelles and by a torpedo which failed to explode. Pieces of her still exist – she was sold to a German firm for scrap in 1921 but broke free from her tow and ran ashore off Kamperduin, on the Dutch coast. Firmly aground, she was stripped of valuable material and left in place as a breakwater of which glimpses can still be seen at low tide.

And the villain of the piece – HMS Hannibal? Judged to be useless in 1915, she was disarmed – her guns were placed on newly-built monitors – and she thereafter had a dull but worth career as a trooper and depot ship. She was scrapped in 1920.

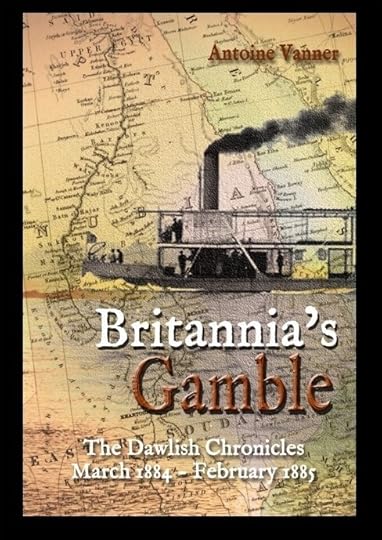

Do you want to read about the amazing Charles Beresford at an earlier stage in his spectacular career? You’ll meet him in Britannia’s Gamble, when Nicholas Dawlish encounters him during the 1884-85 Gordon Relief Expedition. Beresford’s real-life role made him a national hero and laid the foundation for his advancement to high command.Click on the cover image to learn more about Britannia’s Gamble. It’s available in Paperback and Kindle formats and if you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read it at no extra cost.From a review on Amazon.com: “This book had me reading deep into the early morning. I just didn’t want to stop reading. The author has the rare ability to transport the reader to another time and place. Any fan of historical fiction will almost certainly enjoy this book and the entire series.”Click below for purchase information:USA UK & Ireland Canada Austalia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

You’ll meet him in Britannia’s Gamble, when Nicholas Dawlish encounters him during the 1884-85 Gordon Relief Expedition. Beresford’s real-life role made him a national hero and laid the foundation for his advancement to high command.Click on the cover image to learn more about Britannia’s Gamble. It’s available in Paperback and Kindle formats and if you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read it at no extra cost.From a review on Amazon.com: “This book had me reading deep into the early morning. I just didn’t want to stop reading. The author has the rare ability to transport the reader to another time and place. Any fan of historical fiction will almost certainly enjoy this book and the entire series.”Click below for purchase information:USA UK & Ireland Canada Austalia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post Ramming of HMS Prince George 1903 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 14, 2024

Life at sea in the Royal Navy, 1860s

Life at sea in the Royal Navy, late 1860s

Life at sea in the Royal Navy, late 1860s

Scott, 1903

I’ve recently been dipping again into the memoirs of Admiral Sir Percy Scott (1853 -1924), one of the key figures in the modernisation of the Royal Navy in the late 19th and early 20th Century. Scott transformed the discipline of Gunnery, including improvements in accuracy and development of fire control. Though retired before World War I, he was called back to service by Admiral Lord Fisher and Winston Churchill. A talented engineer (who became wealthy through royalties for his inventions), Scott’s interests, besides naval gunnery, also included development of anti-aircraft guns, anti-submarine warfare and the employment of aircraft. He was one of the first to recognise that air-power had made battleships all but obsolete. A difficult and combative personality, who challenged established and conservative thinking, he managed to rise in the navy nonetheless on the basis of sheer excellence and pragmatism of his ideas. Given that he would build his career on mastery of new technology, it’s fascinating how his early days were spent in a mainly sailing navy that still carried much over from the Age of Fighting Sail. His memoirs provide fascinating insights to this.

Scott recounts that “on 25th August, 1868, I went to my first real seagoing ship, the Forte, a 50-gun frigate of 2,364 tons. She had engines, but of such small horsepower that they were only serviceable in a flat calm.”

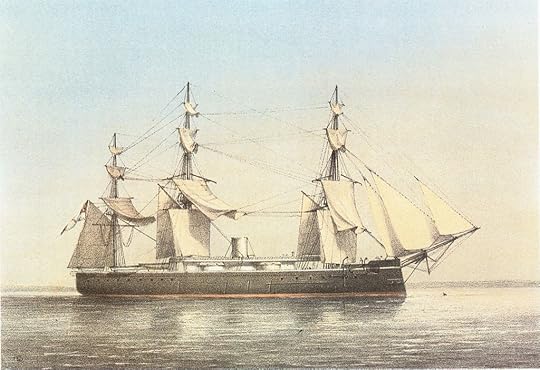

HMS Topaze, of the same size, armament and vintage as HMS Forte

For all practical purposes, HMS Forte was little different to frigates that had gone into action a half-century earlier in the Napoleonic Wars. The realities of handling a ship under sail, the daily routines, the food – and the enforcement of discipline – were little different either. This is borne out by Scott’s recollection of life on board, beginning with the first days of Forte’s deployment, while she was still in the English Channel. Scott took this in his stride: “We started from Sheerness, and en route to Portsmouth we youngsters were fortunately introduced under sail to a gale of wind. Four hours on deck, close-reefing the topsails and clearing away broken spars, probably cured every one of sea-sickness for the remainder of their lives . At any rate, it cured me. An excitement of this sort is, I believe, the only cure for sea-sickness.”

Arrival at the anchorage of Spithead, off Portsmouth, brought its own excitement since “we midshipmen were delighted at being turned out in the middle of the night for a collision. Colliding with or being rammed by another ship, or ramming another ship, is a necessary part of an officer’s education. In this case the barque Blanche Maria had got across our bows, at the change of the tide. There was a lot of crunching, but eventually we got clear without much damage. The Blanche Maria said that we had given her a foul berth; we declared she had dragged her anchor. However that may be, we midshipmen were all delighted at having seen a collision.”

Naval uniforms were in transition in the late 1860s, HMS Forte’s officers were unlikely to as shown in this late-Victorian illustration

Soon after, HMS Forte left to make a three-month sailing passage to Bombay, via the Cape of Good Hope. Scott remembered that “In those old sailing days in fine weather it was very delightful; a man-of-war was a gigantic yacht, scrupulously clean, for we were seldom under steam and as a consequence did not often coal”. This did however bring a major disadvantage: “Shortage of water for the purpose of washing was our great inconvenience; our Commander (i.e. First Lieutenant adb Executive Officer), either for economy or to save the dirt of coaling, made a great fuss about the coal used for condensing. Consequently, we were very often short of water for washing; water for drinking was not limited. On the main deck there was a tank with a tin cup chained to it, so that anyone could get a drink. But there was a little waste, as the men did not always drain the cup dry. In order to check this, the Commander introduced what was called a ” suck-tap”; the tap and the cup were done away with and a pipe placed in lieu of these, and anyone wanting a drink had to take the nasty lead pipe into his mouth and suck the water up; it was a beastly idea, which our new Commander immediately did away with.”

By the late 1860s the ironclad had arrived, with heavier reliance than hitherto on steam, but still carrying sailing rigs. Here’s HMS Monarch of 1868. Painting by Frederick Charles Mitchell (1845 – 1914)

By the late 1860s the ironclad had arrived, with heavier reliance than hitherto on steam, but still carrying sailing rigs. Here’s HMS Monarch of 1868. Painting by Frederick Charles Mitchell (1845 – 1914)

Scott recalled with affection that “In the evening the men always sang, and it was very fine to hear a chorus of about 800 men and boys, many of the latter with unbroken voices. We had one young man who used to sing “A che’ la morte” and other tenor songs from Verdi’s operas, as well as many singers that I have heard on the stage”. He did note however that “the songs, however, were not always of this high class” and that “the men’s songs, and their parlance, was sometimes strong. Many of their comparisons and similes were often witty and quite original.” What was meant by “strong” is probably best left to the imagination.

Writing as he was in 1919, Scott had little sympathy about civilians’ complaints about food rationing during World War I, noting that “some people seemed to think that milk, butter, cheese and vegetables were necessities of life.” He contrasted this with his service on his first ship, “where there were about 750 men and boys in the perfection of health and strength. Their rations at sea consisted of salt beef, salt pork, pea soup, tea, cocoa and biscuit, the last named generally full of insects called weevils.” Except for the addition of tea and cocoa, this was little different to the diet of seamen in Nelson’s day.

Into the 1890s, sail remained important for smaller vessels operating on distant stations where coal was not widely available. Here’s Mitchell’s view of gunboat HMS Thrush (1889)

During HMS Forte’s voyage to India, her captain, John Hobhouse Alexander, earned Scott’s respect as “a magnificent seaman”. The ship’s commander (first lieutenant) was a different matter and “We midshipmen had a terrible time with him. I contradicted him once, and as I happened to be right, he never forgave me.” The penalty was the same as many young gentlemen were subjected to in Nelson’s day: “I saw more of the masthead than I did of the gun-room mess. Sending a boy to sit up at the masthead on the cross-trees was a funny kind of punishment. In fine weather with a book it was rather pleasant; in bad weather you took up a waterproof.” There were more brutal penalties for men on the lower deck “Masthead for the midshipmen, and the cat for the men, was the Commander’s motto. I saw one man receive four dozen strokes of the cat on Monday and three dozen on Saturday, and he took them without a murmur.” Scott wrote in admiration: “That is the spirit which made this a great country; we love men who take punishment without flinching. This particular Commander revelled in flogging, and the sight of it seemed to be the only thing that gave him any pleasure. It was a form of self-indulgence which finally led to his ruin.”

HMS Bramble (1886), another gunboat operating into the 1890s, as painted by Mitchell

This un-named commander’s“ruin” was brought about after Captain Alexander went home after arrival at Bombay. “We became the Senior Officer’s ship on the East Indies Station, and flew the broad pennant of Commodore Sir Leopold Heath, K.C.B. He was a clever, kind and able seaman. He made me his A.D.C., an honour which I appreciated but which got me into further trouble with the Commander, as he did not approve of it. I had more leave stopped than ever and was continually under punishment.” Deliverance came when the Commodore was “up country” (possibly on a social visit or hunitng trip) in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. The commander was now in temporary control of the ship. “An able seaman refused one morning to obey an order. The case was investigated by the commander, and at one o’clock two hours later the offender received four dozen lashes. On the Commodore’s return the man laid his case before him, and complained that the King’s Regulations, which order commanding officers not to inflict corporal punishment until twenty-four hours after the offence, had not been observed.” The consequences for the commander were serious: he “was tried by court-martial and dismissed the ship.” Given that flogging was finally abolished in the Navy in 1879, and that its use was already uncommon, this may have been one of the last occasions it was employed.

Soon after this incident, Scott’s vessel was to be involved in Slave Trade suppression off the coasts of East Africa and Arabia.

Another young officer at sea in the 1860s:Start the Dawlish Chronicles series withStart with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post Life at sea in the Royal Navy, 1860s appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 6, 2024

London’s Princess Alice Disaster of 1878

The Princess Alice Disaster, 1878

The Princess Alice Disaster, 1878Though it is now largely forgotten, one of Britain’s worst maritime catastrophes occurred on the River Thames in 1878 , just downriver from London when the excursion steamer Princess Alice was sunk in a collision.

It is strange that some disasters, such as the loss of the Titanic in 1912, live on in the popular memory while others of comparable magnitude in terms of loss of life, such as the sinking of the liner Empress of Ireland after a collision in the St. Lawrence in May 1914, have been largely forgotten. The Empress of Ireland sinking did however claim 1012 lives as compared with 1514 in the Titanic disaster, almost exactly the same percentage, 68%, of those on board in both cases.

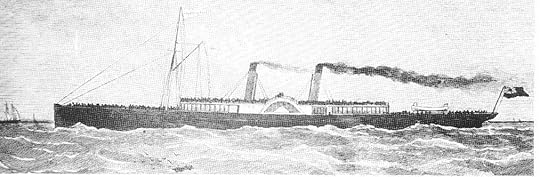

Princess Alice in service before the disaster

Princess Alice in service before the disaster

This line of thinking occurred to me, Antoine Vanner, when I visited the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and was struck by a contemporary model, as shown below, of the collision of the paddle steamer Princess Alice with the collier Bywell Castle in the Galleons Reach section of the Thames Estuary on September 3rd 1878. Though the accident occurred close to shore the death toll was in excess of 650. I find it strange that such a huge disaster, which occurred practically in London, and which claimed the lives of so many of its citizens, should be totally absent from popular memory and that it has not figured, as far as I know, in any novel, movie or television production (especially taking into account the British fixation on costume dramas).

Contemporary model of the Princess Alice disaster in the National Maritime Museum

Contemporary model of the Princess Alice disaster in the National Maritime Museum

The Princess Alice was a 219-foot, 171-ton, paddle steamer built as the Bute in Greenock in 1865 for ferry service on the Scottish west coast. She came south two years later, where she was renamed for service as an excursion steamer on the Thames estuary, under a succession of owners. At this time excursions downriver from London were popular outings for a growing urban population that was enjoying increased if modest prosperity.

On September 3, 1878, a Tuesday, the Princess Alice made a routine trip from the Swan Pier, near London Bridge, to Gravesend and Sheerness. For most passengers heading for Gravesend the attraction was the Rosherville Pleasure Gardens there– officially the “Kent Zoological and Botanical Gardens Institution” and in essence an early version of a theme park – which were a favourite destination for thousands of Londoners. The gardens had their own pier to allow docking of visiting steamers.

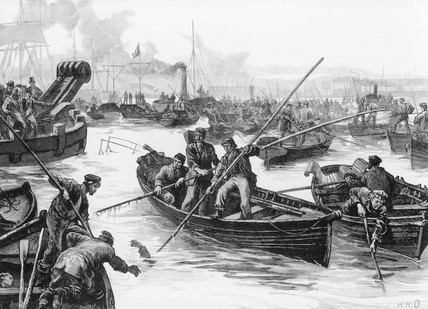

The moment of collision: Princess Alice run down by the Bywell Castle

The moment of collision: Princess Alice run down by the Bywell Castle

By 1940 hrs the Princess Alice was on her return journey, laden with over 700 passengers – an amazing number for such a small craft, on which there could have been little more than standing room. She was within sight of the North Woolwich Pier – where many passengers were to disembark – when she sighted the collier Bywell Castle coming downriver. At 904 tons this was a substantially larger ship than the paddle steamer and was unladen. Ignoring by the Princess Alice’s captain of the “Port to Port” rule for passing ships in the Thames estuary brought the paddler directly in the path of the collier and though the later did reverse engines, this was not done rapidly enough, making collision inevitable.

Contemporary artists left little to the imagination

Contemporary artists left little to the imagination

The Princess Alice was struck amidships by the Bywell Castle and she split in two, sinking in under four minutes and before either of its two boats could be launched – inadequate though these would have been for the number of persons carried. Many passengers were trapped below, as would be attested later when the wreckage was recovered. An added horror was the fact that the collision occurred at the point where large volumes of sewage was discharged – according to a contemporary account “At high water, twice in 24 hours, the flood gates of the outfalls are opened when there is projected into the river two continuous columns of decomposed fermenting sewage, hissing like soda water with baneful gases, so black that the water is stained for miles and discharging a corrupt charnel house odour”. It was thought that many who found themselves engulfed in this ghastly sludge died by asphyxiation.

[image error]

Recovery of bodies from Princess Alice

The exact death toll that resulted is not known with exactitude since there were no detailed passenger list and many bodies may have been washed downriver or buried in the Thames mud. The Thames River Police estimated the death toll as 640 and only 69 persons were saved, mainly through the efforts of the Bywell Castle’s crew, this vessel being scarcely damaged. As the collier was not laden she was however high out of the water, making it difficult to take survivors from the water.

The two sections of the Princess Alice were lifted and beached in the following week and unidentified bodies were buried in a mass grave in Woolwich Old Cemetery, where a granite cross still commemorates them. A distasteful aspect of the aftermath was that crowds of ghoulish sightseers came on trains from London to clamber over the wreckage. It appeared that “anything that could be chipped or wrenched off was carried off as curiosities by visitors”. The Princess Alice’s engines were salvaged. The Bywell Castle had its own appointment in Samarra and she was lost with all hands in the Bay of Biscay five years later.

The beached stern-section of the Princess Alice

The beached stern-section of the Princess Alice

The inevitable enquiry followed the disaster and the findings not unsurprisingly commented on the overloading, poor seamanship and lack of live-saving equipment on the Princess Alice. No doubt there were many statements at the time that “lessons must be learned”, as is always said in our own time after some dreadful incident, but just as in our own day little practical action seems to have accompanied the hand-wringing. The Titanic disaster was still 36 years in the future and application by then of general insights from the Princess Alice disaster could have lessened the death toll significantly.

I find that the loss of the Princess Alice has an almost unbearable poignancy about it. The victims were of all sexes and ages, and were probably in the main of modest wealth and income – I imagine Mr. Pooter and his wife Carrie of the Grossmiths’ “Diary of a Nobody” as being typical. They were returning from a day of innocent pleasure and had they survived they might well have remembered it as one of the happiest of their lives, spent with those they loved. From this humble pleasure they were plunged – literally – into a squalid maelstrom of filth in which their lives and happiness were torn from them and from the family members they left behind.

And so the final question remains – why has the Princess Alice disaster, on London’s doorstep and with its massive loss of life, faded from popular memory?

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s Innocent1864: What links war in Denmark with Civil War in America ?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post London’s Princess Alice Disaster of 1878 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 30, 2024

Pellew and the Dutton – rescue despite the odds

Pellew and the Dutton – rescue despite the odds

Pellew and the Dutton – rescue despite the odds

Edward Pellew

We’ve met Edward Pellew (1757 – 1833) on this blog before (Click here to read) and it’s probable that we’ll meet him again as he ranks just below Nelson, and certainly with Cochrane, as one of the Royal Navy’s most intrepid commanders during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. His earliest fighting experience came during the American War of Independence, when he was present at fighting on Lake Champlain, and his career was to culminate as Admiral Viscount Exmouth when he commanded a combined British-Dutch squadron in operations against Barbary pirates in Algiers in 1816. A humane, generous and decent man, his personal courage was legendary and although his career was studded with desperate naval actions one of his most notable feats of heroism was not to be in a combat situation, but rather a fearless rescue when the East Indiaman Dutton was driven aground in 1796.

1795, the third year of the Revolutionary War, saw Commodore Pellew commanding a squadron of frigates from his own HMS Indefatigable. Operating in the Western Approaches and off North-Western Coast of France, Pellew’s force was to score significant success through the year. By January 1796 however Indefatigable had been brought into Plymouth for refitting. It was an opportunity for Pellew to relax ashore on and 26th January he was on the way with his wife to dine at the house of a well-known clergyman, Dr. Robert Hawker. As the Pellew arrived Hawker ran out and called “Have you heard of the wreck of the ship under the Citadel? “ This was enough to send Pellew racing to the scene of the disaster.

The wreck of the Dutton by Thomas Luny

Note group on beach, hauling on hawsers

The ship involved was the East Indiaman Dutton – and as such manned by civilians. This vessel had been underway for the West Indies with no less than 400 troops for the strengthening of the garrisons there, together with a number of camp followers, not to mention the ship’s own crew – the total was estimated at somewhere between 500 and 600. It is an indication of the extreme dependence upon weather conditions during the Age of Sail that the Dutton had already been seven weeks at sea but had been driven back to Britain by adverse winds. Given the number of people crammed into a vessel less than 200 feet long it is not surprising that there should be a large number of sick on board. It had now been driven against Plymouth Hoe, an open space that slopes down towards the sea and on which the Citadel referred to by Dr. Hawker stands. It ends at low limestone cliffs with a beach below.

The plight of a ship in peril on a lee shore by the Russian master, Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

The plight of a ship in peril on a lee shore by the Russian master, Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

Pellew arrived on the beach to find – one can imagine that it was to his disgust – that most of the Dutton’s senior officers had already abandoned ship. They had made it by clinging to a single rope stretched between ship and shore. Others had also gained the shore but the process was slow and dangerous – one eyewitness wrote that “you would at one moment see a poor wretch hanging ten or twenty feet above the water, and the next you would lose sight of him in the foam of a wave”. It was obvious that this method alone would be incapably of saving the hundreds on board before the hull broke up. Despite Pellew’s exhortations to the ship’s officers to return to the ship – and an offer of five guineas each – they refused to do so, as too did local pilots who believed that the case was hopeless. Pellew realised that without his direction almost all on Dutton would be lost and he resolved to go out himself. He did so by getting dragged to the ship by the single rope. This was hazardous, since the vessel’s masts had collapsed towards the shore and he was at one stage dragged under the mainmast, only extricating himself with leg and back-injuries that were afterwards to confine him to bed. He did however finally reach the wreck and took command – he made it plain that absolute compliance with his orders would be essential and that he himself would be the last to quit the wreck. His reputation as a national hero was already well established and his presence alone did much to reduce any tendency to panic. A complication was however that some of the soldiers had broken into the spirit store and were already drunk. Pellew, sword in hand, made it plain that that he would have no hesitation in killing anybody exhibiting disobedience.

Aivazovsky again: the ordeal of rescue craft in violent surf

Aivazovsky again: the ordeal of rescue craft in violent surf

Back at HMS Indefatigable it was not known that Pellew was on the Dutton but efforts were made to get boats to her. Despite gallant attempts it proved impossible to bring them alongside. More successful however was a small boat from a merchant vessel. This was manned by a naval midshipman and the merchant vessel’s Irish mate, one Jeremiah Coghlan. With these men’s help Pellew managed to get two more hawsers stretched from the wreck to the shore. Pellew set men to work to fashion got cradles constructed that could be slung beneath the hawsers to be pulled to and fro. In order to avoid shock-loading of the hawsers as the wreck rolled, and to avoid the consequent risk of their snapping, they were not made fast at the shore end. Each line was instead held by a group of men who tightened and relaxed them so as to keep the tension steady. This must have been exhausting and was not the least impressive aspect of the entire rescue. Transfer by cradle now commenced but it was obviously unsuited to the weak and vulnerable – a category that included one three-week old baby on board. Coghlan in his small boat managed to get some 50 people to shore before any other craft reached the wreck.

While this was in progress a sloop and two large pulling-boats had managed to reach the Dutton from shore. In these the women children and the sick were landed, Pellew being adamant in ensuring that order was maintained despite the soldiers’ drunkenness – he was witnessed beating one looter with the flat of his sword. The handling of the rescue boats in such conditions was an epic in itself and they were in due course to get the soldiers to shore, followed by the ship’s company. Pellew was among the last to leave – passing ashore along a hawser – and the battered hull broke up soon afterwards. All on board had been saved.

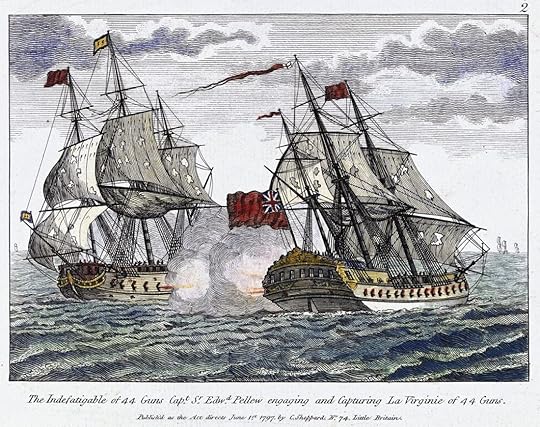

HMS Indefatigable in action under Pellew against French frigate La Virginie 1st June 1797

HMS Indefatigable in action under Pellew against French frigate La Virginie 1st June 1797

Coghlan in silhouette

It is typical of Pellew that the only mention made in the Indefatigable’s log was the statement “’Sent two boats to the assistance of a ship on shore in the Sound” with no reference to himself. A pleasing postscript – and a long one – was that Jeremiah Coghlan (1776 – 1844), the young civilian who had done such heroic work in his small boat, was to join the Navy and have an illustrious career. Pellew took him on board the Indefatigable as a midshipman and had him follow him when he took command of HMS Impetueux in 1799. Coghlan was given command of the cutter HMS Viper the next year and he was promoted further following a cutting-out operation, in which he snatched the French gun-brig Cerbère from a defended harbour. His subsequent career was to be the stuff of naval fiction – single-ship actions, storming shore-batteries, seizing Naples in 1815. When Pellew became Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, from 1811 Coghlan was to be his flag captain on HMS Caledonia. One of the heroes of the Age of Fighting Sail, he was to live long enough to see the birth of the steam navy.

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post Pellew and the Dutton – rescue despite the odds appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 8, 2024

Merchant Service Hell in the mid-19th Century

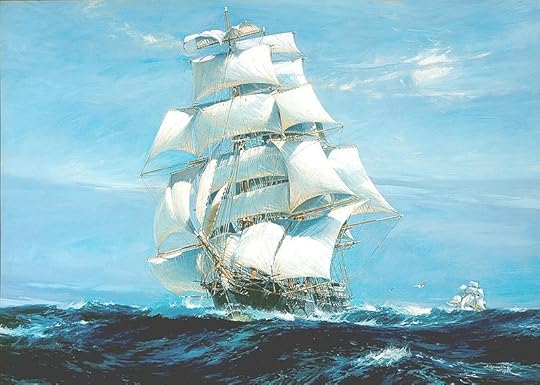

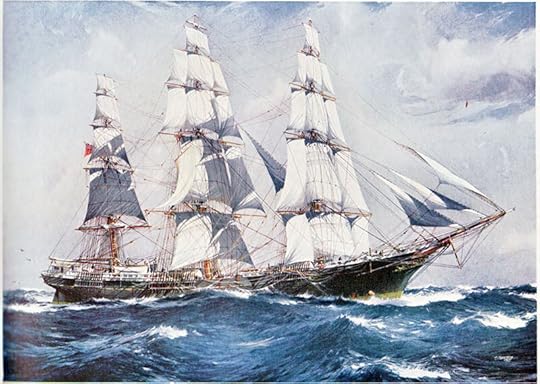

It is impossible to see images of the great clippers and other large vessels under sail in the mid to late 19th Century, a time when hull design and the technologies and disciplines of managing sail reached their apogee, without being fired with admiration. The great “tea races” – in which vessel as competed to be first to the year’s new crop from China to London – were spectacular events, admired and followed by the general public. The most notable these was in 1866, when the clipper Taeping docked 28 minutes ahead of her closest rival, the Ariel, after a 99-day passage logged at 15,800 miles. They had left China on the same tide, followed a route around the Cape of Good Hope and docked on the same tide in Britain. There were other equally remarkable voyages – some being mentioned later in this article.

Ariel leading Taeping, painting by Jack Spurling (1870-1933)

The beauty of these ships, and the spectacular sight they made under full sail, easily blind one to the fact that many of them were floating hells, on which seamen, enlisted for each voyage only, were driven to the limits of human endurance. Unprotected by the rules and regulations applying in national navies, and enjoying the scantiest of legal protection, they were often at the mercy of captains whose characters and behaviours bordered on the psychopathic.

Taeping and Ariel racing up the Channel, by Thomas G. Dutton (1820-1891)

Taeping and Ariel racing up the Channel, by Thomas G. Dutton (1820-1891)

Baron Walter Runciman

An interesting insight to such conditions comes from the memoirs of Baron Walter Runciman (1847 –1937), who was a classic case of a poor boy of high initiative “making good”. Born in Dunbar, Scotland, son of a schooner captain who later became a coastguard in Northumberland, he ran away to sea at the age of twelve. A ship’s master himself by 21, he founded a shipping line and in due course became a major force in the British mercantile industry up to his death. On the way he was elected also as a Liberal Member of Parliament and was subsequently raised to the House of Lords. He prefaced him memoir “Windjammers and Sea Tramps”, published in 1905, with the justifiably proud statement that “I went in at the hawse-hole and came out at the cabin window.”

Even in the days of his prosperity, Runciman appears to have been still so marked by the horrors of his early service that he entitled one of his chapters, “Brutality at Sea”. It’s worth quoting from it to get a feel for the world he entered. He described many a captain as a man “who would pace the poop or quarter-deck of his vessel with the air of a monarch. Sometimes a slight omission of deference to his monarchy would take place on the part of officers or crew. That was an infringement of dignity which had to be promptly reproved by stern disciplinary measures.”

Clipper Argonaut by Jack Spurling

An offending officer would get off relatively lightly by being “usually ordered to his berth for twenty-four hours—that is put off duty.” The seamen would fare worse, since often “offences were rigorously atoned for by their being what is called “worked up,” i.e., kept on duty during their watch below; or, what was more provoking still, they might be ordered to “sweat up” sails that they knew did not require touching. This idle aggravation was frequently carried out with the object of getting the men to revolt; they were then logged for refusing duty and their pay stopped at the end of the voyage. It was not an infrequent occurrence for grown men to be handcuffed for some minor offence that should never have been noticed.”

Runciman indicates that an element of deliberate sadism was often involved: “The sight of human suffering and degradation was an agreeable excitement to this class of officer or captain. If some of the villainy committed in the name of the law at sea were to be written, it would be a revolting revelation of wickedness, of unheard-of cruelty. Small cabin-boys who had not seen more than twelve summers were good sport for frosty-blooded scoundrels to rope’s-end or otherwise brutally use, because they failed to do their part in stowing a royal or in some other way showed indications of limited strength or lack of knowledge. The barbarous creed of the whole class was to lash their subjects to their duties.”

One suspects that one specific case mentioned might have referred to Runciman himself: “A little fellow, well known to myself, who had not reached his thirteenth year, had his eyes blacked and his little body scandalously maltreated because he had been made nervous by continuous bullying, and did not steer so well as he might have done had he been left alone. It is almost incredible, but it is true, some of these rascals would at times have men hung up by their thumbs in the mizzen rigging for having committed what would be considered nowadays a most trivial offence.”

Voyage’s End: “Mist in the Port of London” by Charles John de Lacy (1860-1936)

Voyage’s End: “Mist in the Port of London” by Charles John de Lacy (1860-1936)

Runciman noted the “captains who claimed public attention for reasons that would not now be looked upon with favour were usually known by the opprobrious name of ‘Bully this’ or ‘Bully that.’” and that “it was generally the fearless way in which they carried sail, and their harsh, brutal treatment of their crews that fixed the epithet upon them. I am quite sure many of them were proud of it.” Runciman drew attention to “One gentleman, well known in his time by the name of Bully W——, (who) stood on the poop of the square-rigged ship Challenge, and shot a seaman who was at work on the main yardarm.” He identified this captain as having “once commanded a crack, square-rigged clipper called the Flying Cloud.”

Robert H. Waterman

The “Bully W – – “ to whom Runciman referred was the American Robert Waterman (1808 – 1884). His reputation as a hard driver was confirmed in 1849 when he brought the clipper Sea Witch – carrying more sail a than a “74” ship of the line – from Hong Kong to New York vis the Cape of Good Hope in 74 days. His longest distance covered in a single day was 308 miles. Two years later Waterman took command of the new clipper Challenge, being offered a bonus of $10,000 if he could get her from New York to San Francisco within 90 days. The treatment of his crew was such as to trigger a minor munity, in which the first mate was almost killed, followed by Waterman’s flogging of the mutineers – something that had been outlawed by the US Congress the previous year. Waterman also slashed the cook’s scalp with a carving knife and broke the arm of one of the mutineers with a club, then had him shackled the fractured limb. A later incident, involving the death of a seaman, led to him having no further commands.

Clipper James Baines by Jack Spurling (1870-1933)

Runciman mentions that Waterman was said “never to have voluntarily taken canvas in. He was one of those who used to lock tacks and sheets, so that if the officers were overcome by fear they could not shorten canvas.” Paradoxically “His fame spread until it was considered an honour to look upon him, much less to know him. He became the object of adoration, and perhaps his knowledge of this swelled his conceit.”

“But this man was only one among scores like him,” Runciman recalls.

It’s a fact worth remembering when we look on images of the great square-riggers in all their glory.

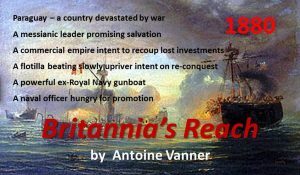

Naval Fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor Canada – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on any cover above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on any cover above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Merchant Service Hell in the mid-19th Century appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 2, 2024

HMS Thunderer 1879: death knell muzzle-loaders

HMS Thunderer 1879: the end of muzzle-loaders in the Royal Navy

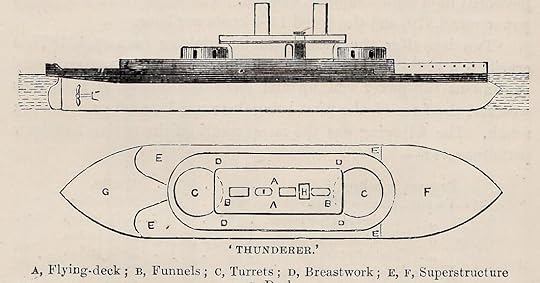

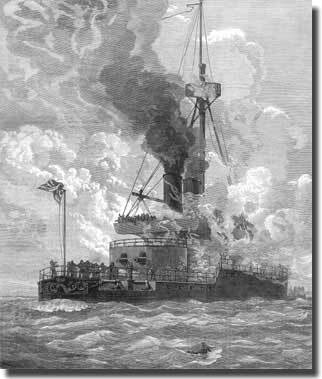

HMS Thunderer 1879: the end of muzzle-loaders in the Royal NavyThree ships of the Royal Navy in the 1870s, HMS Devastation, her close sister HMS Thunderer and her slightly larger sister HMS Dreadnought, can be fairly regarded as the models for subsequent mainstream battleship layout and development.

HMS Devastation, HMS Thunderer’s close sister, firing a salute

These ships were the first mastless battleships, armed with four 12-inch guns in rotating turrets and with a central superstructure layout. Armoured with 12” of iron from end to end, they were of 6000 tons on a length of 285 feet. Their hydraulic turret machinery and twin screw propulsion put them in the forefront of mechanical design and their coal bunkerage provided a range sufficient – in theory at least – to cross the Atlantic.

HMS Thunderer’s layout – turrets fore and aft, superstructure amidships

These vessels had however two serious weaknesses. One was irredeemable – that low freeboard ensured that even in relatively calm seas the foredeck was awash, thereby limiting fighting ability.

HMS Thunderer, her decks awash, in a heavy sea late in her career

The second weakness – the retention of muzzle-loading main armament – was one that could be recovered from, but not before a ghastly accident emphasised the need for change. During the 1860s the Royal Navy had made trials of breech-loading guns, but after a number of failures – mainly resulting from metallurgical problems – there was a reversion to muzzle-loaders, which had none of the complications of machining sealing and easily operating breech closures. Armstrongs, the great British gun-maker, did however persist with development and by the late 1870s much more reliable designs were to become available. In the meantime the Royal Navy relied on ever-larger muzzle loaders, culminating in the 80-ton, 16” calibre weapons mounted in HMS Inflexible (completed 1881). This was made possible by the use of hydraulic power for handling, loading and ramming these guns with their enormously heavy powder charges and shot. These weapons had remarkable strength, as shown in experiments with a 9-inch gun In 1869, the central tube splitting only when the 1,008th round was fired. The metal yielded gradually, and the strength of the outer jacket was thoroughly proved by firing a further 41 forty-one rounds after the barrel had split, and still the exterior remained perfectly sound.

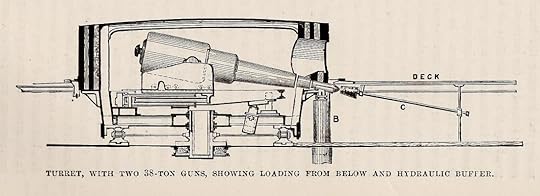

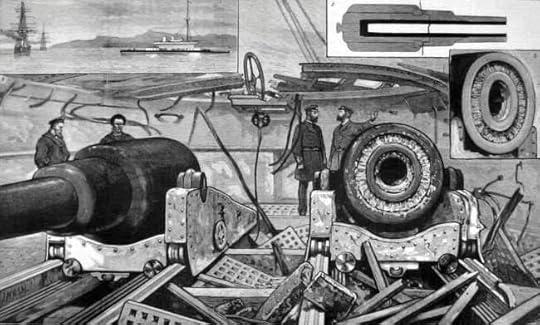

In the case of HMS Thunderer and her sisters, the guns were of 12” calibre and 38 tons weight. Mounted in turrets fore and aft they were run out for firing but were thereafter run back in again, and the muzzles depressed so that fresh projectiles could be loaded – the illustration below shows the process.

HMS Thunderer’s 12″ muzzle-loaders depressed for reloading

HMS Thunderer’s 12″ muzzle-loaders depressed for reloading

HMS Thunderer’s career was to be marked by two serious accidents. The first was not gunnery-related and involved a boiler explosion in July 1876 as she proceeded from Portsmouth Harbour to Stokes Bay to carry out a full power trial. This killed 15 people instantly, including her captain who was in the boiler room at the time, and injured around 70 others, of whom 30 later died. The reason for the explosion was that the pressure gauge was broken and the safety valves had seized through corrosion. The boiler explosion signalled the end of box boilers in favour of the Scotch cylindrical type, and it led directly to the writing of the first official RN Steam Manual in 1879. One also imagines that there was increased attention thereafter to the inspection and testing of safety valves!

[image error] HMS Thunderer enveloped in smoke and steam as a boiler explodes, July 1876

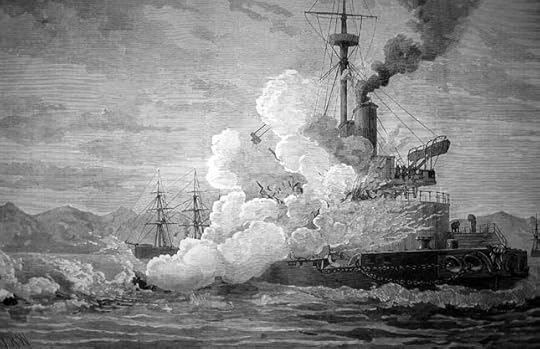

The second accident happened when HMS Thunderer, attached to the Mediterranean Fleet, was exercising in the Sea of Marmara on January 2nd, 1879. One of the 38-ton 12” guns mounted in the forward turret burst, killing two officers and eight men, besides wounding several others.

12″ gun explodes in HMS Thunderer’s forward turret, January 1879

12″ gun explodes in HMS Thunderer’s forward turret, January 1879

In view of the implications of the accident – the possibility that a class of weapon that armed the navy’s most powerful ships was fatally defective – the Admiralty appointed a commission of officers and scientific experts by to investigate its causes. This commission decided that the accident had been the result of a deplorable error in loading discipline, made worse by the inherent nature of the loading process and that on the day the gun had been fired when loaded with two complete rounds of powder and projectile.

The aftermath of the explosion – damage inside the turret

During the firing exercise it was intended to fire the two guns simultaneously, both being loaded with a battering charge of 110 lb. of powder and a Palliser projectile 800 lb. in weight. One gun, however, missed fire, although nobody was apparently aware of the fact – the concussion and the smoke made by the discharge of one gun was so great that it was considered difficult for anyone was on the look-out to tell that they were not due to both guns. The crews were drilled to run their guns in directly they fired, so as to be in readiness for reloading and, not observing that one of the guns had not gone off, they proceeded to run in. Both guns were reloaded through the muzzle, by the hydraulic system, with the result that the weapon with the double charge burst when the next round was fired.

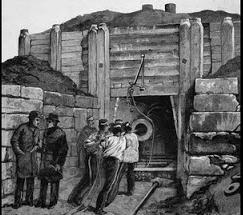

Surviving 12″ from turret in test cell at Woolwich Arsenal

Surviving 12″ from turret in test cell at Woolwich Arsenal

When the Admiralty received the report of the commission they determined, “in order that no question should arise in the future as to the correctness of the conclusions which the committee had arrived at”, to have the surviving gun brought back to Britain and subjected to trials, with a view of ascertaining under what other conditions it would burst. These tests were conducted at Woolwich Arsenal, the gun being enclosed in a protective bunker or “cell” to avoid further risk to life. After a series of experiments however, when every suggestion had been tried without injuring the gun, it was double loaded, just as the commission had reported that in their opinion the burst gun had been. When the smoke cleared away from the ceIl it was found that the gun had burst like its former companion, and that the fractures in the two guns were nearly identical.

Italy’s Caio Dulio – in her time one of the most heavily armed ships afloat

Italy’s Caio Dulio – in her time one of the most heavily armed ships afloat

Another accident, which, however, fortunately, was not attended by loss of life, occurred to one of the massive Armstrong 100-ton rifled muzzle-loading 17.7” guns mounted on the Italian battleship Caio Duilio. This followed close on the HMS Thunderer disaster, in March 1880, when the gun was being tested for acceptance. In this case the barrel was fractured, the rear portion being forced to the rear, and carrying with it the covering jackets, none of the superimposed coils, however, being injured.

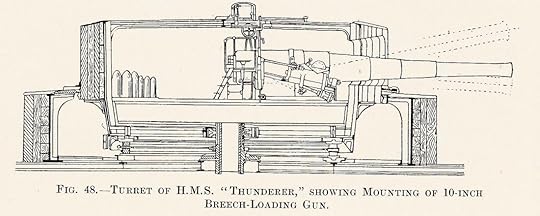

These accidents undoubtedly strengthened the feeling in favour of a return to breech-Ioaders which had been growing in the mind of the Navy for some time, since it was quite certain that no such mistake as double-loading could be made with a breech-loading gun, as it was impossible to force the projectile home beyond a certain distance, and consequently there would not be room for a second charge. By this stage advances in metallurgy had made breech-loading of even large weapons a practical option and over the coming years new breech-loaders were substituted for muzzle loaders still in service. Among the ships to be so upgraded were HMS Thunderer and her sisters, receiving 10” weapons, as per the diagram below.

HMS Thunderer turret re-gunned with 10″ breech-loader

This final acceptance of the superiority of the breech-loader brought to an end an era that had begun in the days of Drake and which encompassed all the great naval actions of the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was truly the end of a glorious era.

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post HMS Thunderer 1879: death knell muzzle-loaders appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 4, 2024

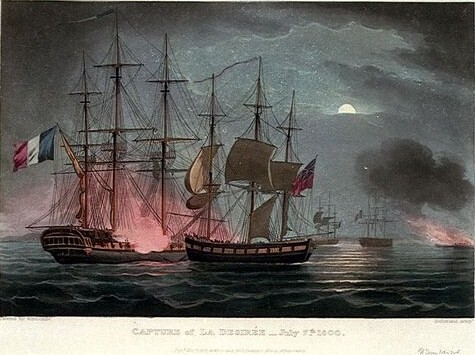

Fireship attack: HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800

Fireship attack: HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800

Fireship attack: HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800For many centuries fireships were to be some of the most dramatic and devastating of all naval weapons, albeit difficult to deploy and dangerous to their crews. The most effective and history-changing use ever of such ships was when they were used to attack the Spanish Armada at anchor off Gravelines in 1588. The effect was out of all proportion to the damage they did – or could do – as they panicked the Spanish captains into cutting their cables and running out into the North Sea. Adverse weather made a return via the English Channel impossible, ending hopes of landing a Spanish army on British soil and driving the majority of the ships to destruction on the Scottish and Irish coasts. Creasey, the historian, was to number this defeat among what he termed “The 15 Decisive Battles of the World”. One of the last deployments of fireships by the Royal Navy was to take place in July 1800 and a key role in the action would be played by a sloop-of-war of innovative design, HMS Dart.

Spanish Armada under fireship attack by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740 – 1812)

Spanish Armada under fireship attack by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740 – 1812)

Close inshore action against French shipping by aggressive British naval officers was to be a constant feature of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and the July 1800 attack, on the heavily defended French base at Dunkirk, was to be one of the most daring. The inspiration for the raid came from the noted frigate captain, Henry Inman (1762 – 1809), then in command of the 32-gun Andromeda, and the objective was destruction of four French frigates anchored in the Dunkirk roads – Poursuivante, Incorruptible, Carmagnole and Désirée. They lay under the protection of powerful coastal gun-batteries, the anchorage was patrolled by rowed gunboats and treacherous shoals and shallows made approach difficult. Fireships were to be a key feature of the operation and four obsolete brigs were prepared for such duty – Wasp, Falcon, Comet and Rosario.

Under Inman’s overall command, the squadron – what might now be termed a task-force – consisted of the frigates Andromeda and Nemesis, the brigs Boxer and Biter, the four fireships, two hired cutters, Kent and Ann and a hired lugger, Vigilant. There was in addition a most unusual vessel, HMS Dart, classed as a sloop since nobody knew what else to call her.

Samuel Bentham

HMS Dart, and her sister HMS Arrow, were experimental vessels, never indeed to be repeated. They were the brain-child of Sir Samuel Bentham (1757 – 1831) – brother of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. At this stage in his remarkable career as an engineer and naval architect, in Britain, Russia and China, Bentham held the position of Inspector General of Naval Works. Designed to operate in coastal waters, these two vessels were virtually double-ended and featured a large breadth-to-length ratio, structural bulkheads, and sliding keels. Of 150 tons and a mere 80 feet long overall, they packed an enormous punch for their size, all guns being carronades, (Click here for more on these weapons) HMS Dart and HMS Arrow carried twenty-four 32-pounders on their upper deck, two 32-pounders on their forecastle and another two on each quarterdeck. HMS Dart’s command had been assumed in 1799 by Commander Patrick Campbell (1773 –1841), who would later rise to flag rank and in this year, and the next, she would see active and successful service in Dutch coastal waters.

Bad weather delayed the start of the operation but it was finally launched on the night of 7th July, the vessels in line ahead with Campbell and HMS Dart – with her massive fire-power – leading. His objective was to attack the innermost French frigate while the fireships were to grapple the other three and so destroy them. HMS Dart drew ahead of the other British vessels and, as the night was dark, managed to come close enough by midnight for the nearest French vessel to challenge her. Campbell answered that his ship was French, from Bordeaux, and this appears to have been accepted. HMS Dart, unsuspected, moved on unhindered past the first two frigates until another French challenge asked what convoy was coming in her wake. The answer “Je ne sais pas” – “I don’t know” – was, quite amazingly, accepted. Suspicions were however aroused on the third French ship, which now opened fire. As she ran past her, HMS Dart unleashed a smashing broadside. Her carronades had been double-shotted with roundshot and grapeshot – almost 900 pounds of metal per broadside – and the effect was devastating.

HMS Dart (r) crashes into Désirée – note that she is virtually double-ended

HMS Dart (r) crashes into Désirée – note that she is virtually double-ended

Engraving after a painting by Thomas Whitcombe (1763-1824)

HMS Dart drove on to crash into her target, the fourth and innermost frigate, the Désirée. Her bowsprit ran into the foremast’s shrouds. Led by HMS Dart’s first lieutenant, James M’Dermeit, fifty men swarmed across. The inevitable man-to-man fighting ensued and M’Dermeit, wounded, called for reinforcement. Campbell managed to drag HMS Dart fully alongside so as to allow a second boarding party to get across. This decided the issue and the French were subdued and struck their colours. Captain Inman had been following in the lugger Vigilant, crewed by thirty volunteers from Andromeda, and under intense fire, came alongside Désirée, boarded, cut her cable and took her out to sea. The struggle had been vicious but one-sided – of Désirée’s 330-man crew over 100 were killed or wounded, with only a single midshipman surviving from her officers. HMS Dart, by comparison, suffered one man killed and eleven wounded – surprise had paid off.

The fireships had meanwhile launched their attack. Packed with combustible material and gunpowder, set ablaze by their volunteer crews, they were steered towards the remaining three French frigates while the Dart and the two brigs, Boxer and Biter, provided covering fire. Pulling boats accompanied them to take off the crews – the officers commanding the fireships remained on board until they were all but enveloped by flames. The French reacted as the Spanish had done over two centuries previously – they cut their cables and sailed under fire past Dart, Boxer and Biter into shoal-waters familiar to them where the British could not follow. Unmanned now, the fireships drifted until they exploded without doing any damage to the enemy. French rowed-gunboats came out from Dunkirk to join in the fray but were repulsed by the hired cutters.

Incorruptible, sister of the Désirée , of the same Romaine-class

Incorruptible, sister of the Désirée , of the same Romaine-class

She was one of the three French frigates to escape capture at Dunkirk

Recognising that the three surviving French frigates were now unreachable, Inman ordered withdrawal. With no room for prisoners and with large numbers of French wounded, he sent his captives back into Dunkirk. Success had been partial but the moral effect of the attack must have been considerable. Campbell of HMS Dart was deservedly promoted to post captain and given command of the sixth-rate HMS Ariadne. The Désirée was commissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Désirée under Inman’s command. She was to see much active service thereafter, including participation in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. Inman’s own subsequent career was also active but poor health led to his early death in India in 1809. It is notable that prize money was paid for Désirée’s capture but head money, an award made for enemy servicemen killed, wounded or captured, was not paid, probably because of the return of the French prisoners.

And what became of the innovative HMS Dart and her sister Arrow? Both were to have further active careers. Perhaps we’ll meet them on a future blog!

Naval Fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor Canada – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on any cover above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on any cover above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Fireship attack: HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.