Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 3

March 12, 2025

The Sinking of Hospital Ship HMHS Anglia, November 1915

The Loss of Hospital Ship HMHS Anglia, November 1915

The Loss of Hospital Ship HMHS Anglia, November 1915It was very noticeable in 2014/18 that though commemoration of the First World War opened with a fanfare – and in Britain at least focussed on the Western Front almost to the exclusion of all else – its profile in the media dwindled steadily thereafter. Throughout the years up to 2018 there were however a number of 100th anniversaries of losses and tragedies which provoked shock and anger at the time, but which are now remembered, if at all, only by the families of the victims. It is with one such case that this article deals, for though all shipwrecks are terrible an extra degree of horror is involved when the vessel in question is carrying sick and wounded troops – as was the case with the hospital ship HMHS Anglia.

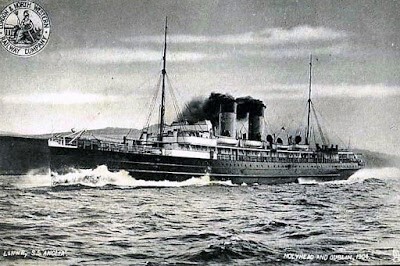

SS Anglia – seen in peacetime service in 1904

Away from the Western Front 1915 was not only the year of Gallipoli, but also of the first German unrestricted U-boat campaign. From February to August commercial shipping was especially targeted and two incidents in particular, the sinking of the liner RMS Lusitania in May and of SS Arabic in August, both involving loss of American citizens, came close to drawing the United States into the war. It was to avoid this that in September orders were given that the German High Seas U-Boat flotillas be withdrawn from the commerce war. This did not mean the end of the killing however and merchant ships and fishing vessels continued to be vulnerable should they be considered to be contributing to the Allied war effort. In the month of November 1915 some 60 non-naval ships were sunk by U-boat action, either by torpedoes, by shelling, by explosive charges placed by boarding parties, or by laying of mines in coastal waters. This last was a role for which the submarine was particularly suited.

Le Calvados – 740 lives lost

The vast majority of these craft were sunk in the North Sea, in the English Channel and Western Approaches, and in the Mediterranean. In addition two major troopships were torpedoed off the North African coast by the submarine U-30, the French Le Calvados on 4th November, with the loss of 740 lives and the Italian Ancona, sunk four days later with some 200 lost. The most terrible loss of all, smaller in number of casualties but even more dreadful in detail, was the sinking of HMHS Anglia. The 100th anniversary of this tragedy was on 17th November 2015.

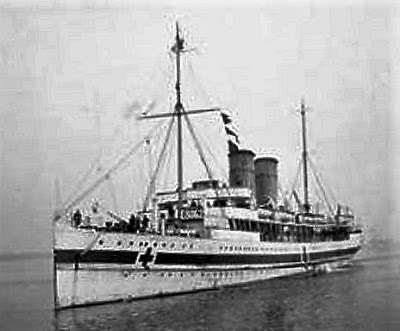

HMHS Anglia, identified as a hospital ship by her white hull and markings

Built in 1900, the Anglia was a 1862-ton, 362-foot passenger ferry had served in peacetime on routes across the Irish Sea from Liverpool and Holyhead to Dublin. Her extensive public spaces and high speed – 21 knots – suited her for conversion into an auxiliary hospital ship in mid-1915. Serving on routes across the English Channel, she was an ideal vessel for carrying wounded back to Britain from France. She was sufficiently well thought of that when King George V, visiting France to review troops, suffered a riding accident it was on HMHS Anglia that he was brought back to Britain.

UC-5 after capture by Royal Navy

Considering the vast numbers of troops who were carried across the English Channel in the war years, it is surprising that so few hospital or troop ships were sunk. This is the more so since German capture of most of the Belgian coast allowed U-boat flotillas to be based in the ports of Ostende and Zeebrugge. Nets and minefields offered some, but not impenetrable, defence against U-boats passing through the Straits of Dover, and the majority that managed to do so were focussed on raiding or mine-laying further west. The success of the mixed force known as “The Dover Patrol” in securing the safety of troop movements to and from France was to be one of the great, and now largely forgotten, epics of the First World War.

HMHS Anglia was to be one of the victims of a U-boat which did pass safely through the British defences. This was UC-5, a small 168-ton minelayer submarine which entered service in mid-1915. In a career lasting just one year the mines she planted accounted for no less than 28 ships, including the British submarine E-6, as well as damaging several more.

In the morning of 17th November 1915, HMHS Anglia left Boulogne harbour and headed for Britain – a passage of a few hours only. On board she carried some 366 wounded men, of whom 166 were “cot cases” accommodated on beds or stretchers. She headed for a gap in the British sub-surface defences known as “The Folkestone Gate”, reaching it just after noon. Close to it she struck a mine, the explosion being sufficiently powerful to rupture a hole on the port side, just ahead of the bridge. She immediately began to settle by the bows, listing heavily to port as she did. The bridge had been wrecked, though the captain, Lionel John Manning, had survived. He immediately tried to have a radio-SOS transmitted but the set was damaged and the operator was injured.

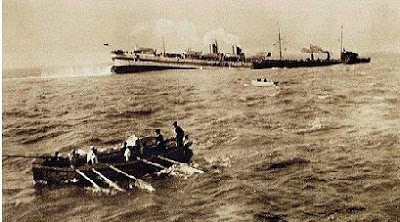

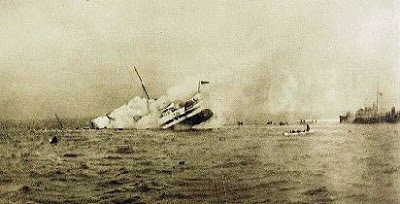

Photograph from rescue ship – HMHS Anglia is down by bows, Ure standing close by

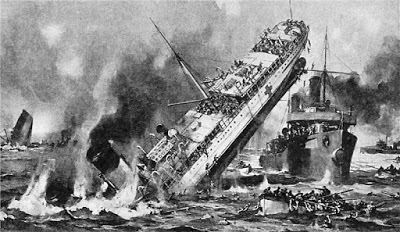

The scene on deck as visualised by the Illustrated London News

All now depended on the Anglia’s escort, the River-class destroyer HMS Ure, and other vessels in the vicinity. HMHS Anglia had begun to settle so quickly that two of its hospital wards were flooded almost immediately and it appears that few escaped from them. Other wards became quickly awash and crew, nurses and the less badly-wounded patients now attempted to get the more severely injured cases to safety. Due to the listing only one lifeboat could be got away – this was on the port side and could take no more than 50 people. Despite this order was maintained and the behaviour of all involved appears to have been beyond praise as regards selfless courage and discipline. Stories abounded of nurses staying by the wounded as the ship settled and of amputees finding the strength to struggle on deck or even to swim.

HMS Ure drew close to take off as many as she could, transferring them to a nearby collier, the SS Lusitania (a namesake of the liner torpedoed earlier in the year) and to HMS Hazard, an 1894-vintage Dryad Class torpedo-gunboat that had been converted for use as a submarine depot ship. By now HMHS Anglia’s stern had risen so high that her propellers were uncovered, still rotating. The Lusitania had been just to the west as the mine exploded and she had immediately put about and launched two boats. Despite the hazard represented by the propellers these boats pulled in under HMHS Anglia’s stern and allowed some 40 men to jump into them. As Anglia’s head dipped further the Ure’s captain placed the destroyer across the sunken bows and managed to get yet more survivors away. The last off appears to have been a fourteen-year old assistant steward called Herbert Scott.

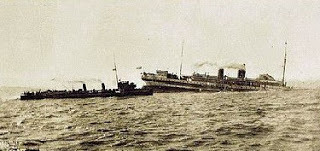

HMS Ure (l) and HMHS Anglia (r), sinking

Artist’s impression of HMHS Anglia’s final plunge. Note the inaccuracies – HMS Ure is shown too large (r) while the Lusitania, sinking in right background, went down later. Good propaganda but bad history!

HMHS Anglia went down some twenty minutes after the explosion, and settled on the shallow seabed, her masts rising above the water’s surface. The tragedy was not yet over however.

The actuality: HMHS Anglia’s final plunge caught on camera

The Lusitania’s survivor-laden boats had just drawn alongside her when she too touched off a mine. As she settled, and rolled over, her boats managed to get her crew off. She floated for some time, keel up. By now however other ships had arrived on the scene and the survivors were quickly transferred to them.

Given the short time between explosion and sinking, and the incapacity and vulnerability of the passengers HMHS Anglia carried, the casualty list could have been much longer had not such discipline prevailed. The 164 dead were made up of one nursing sister named Mary Rodwell, nine Royal Army Medical Corps staff, and 129 wounded men. 25 of the Anglia’s own crew died.

UC-5 on display in Central Park, New York, after the US entered the war

And UC-5? Her fate was a bizarre one. She ran aground off the British coast in April 1916. She was recovered and put on display in the Thames in London and afterwards, then the United States entered the war, in New York’s Central Park. Few who saw her there could have imagined the horror she had unleashed on HMHS Anglia – yet dreadful as it had been it was just one more tragedy in a month of tragedies.

Britannia’s Spartan Like all volumes of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Spartan ,amy be read as a standalone or as chronologically partmof the series. The main action is set in April – August 1882.

Like all volumes of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Spartan ,amy be read as a standalone or as chronologically partmof the series. The main action is set in April – August 1882.

Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

Dawlish has no forewarning of the nightmare of riot, treachery, massacre and battle he and his crew will encounter.

A new balance of power is emerging in the Far East. Imperial China, weak and corrupt, is challenged by a rapidly modernising Japan, while Russia threatens from the north. They all need to control Korea, a kingdom frozen in time and reluctant to emerge from centuries of isolation.

Dawlish finds himself a critical player in a complex political powder keg. He must take account of a weak Korean king and his shrewd queen, of murderous palace intrigue, of a powerbroker who seems more American than Chinese and a Japanese naval captain whom he will come to despise and admire in equal measure. And he will have no one to turn to for guidance…

Britannia’s Spartan sees Dawlish drawn into his fiercest battles yet on sea and land. Daring and initiative havealready brought him rapid advancement and he hungers for more. But is he at last out of his depth?

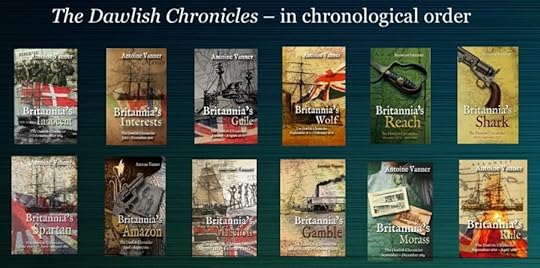

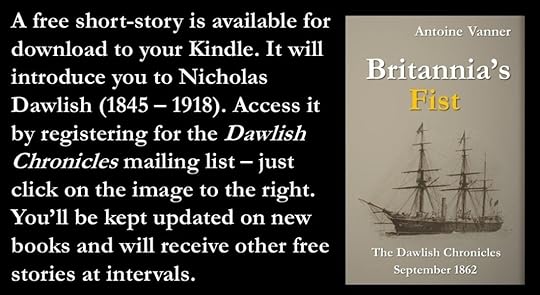

Available in paperback and Kindle formats. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra charge. Details for purchase below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Sinking of Hospital Ship HMHS Anglia, November 1915 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 6, 2025

The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”

A Flawed Concept – The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”

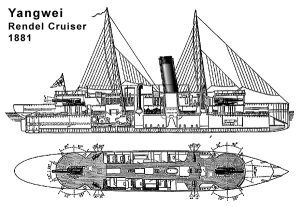

A Flawed Concept – The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers”In my novel Britannia’s Spartan (click for details), set in 1882, an important role is played by a cruiser of the Imperial Chinese Navy, the Fu Ching. She is the fictional sister of two warships the Yang Wei and the Chao Yung, that did indeed serve in that navy. For a short period in the 1880s these vessels carried what was probably the heaviest armament for any ships of their sizes afloat. Built in British yards, their design had been evolved by Sir George Rendel, building on the success of his earlier concept, the “Flatiron Gunboat” which was armed with a single large-calibre weapon. (One of these gunboats is the heroine of my novel Britannia’s Reach (click for details). While these “Flatirons” were intended for use in estuaries and sheltered waters, the new design envisaged a small, cheap cruiser-type vessel suited for service in the open sea and carrying two of the most powerful guns then available. These were Armstrong 10” breech-loaders. With reasonable speed for the time, and with high mobility, these vessels would be suited, in theory at least, to engage larger and more heavily armoured, but less nimble ships. Despite the superficial attractiveness, the concept was turned down by the Royal Navy, due to concerns about seaworthiness in the English Channel and the North Sea. These areas might well become battlegrounds in any future war since France was perceived as Britain’s most likely potential enemy in this period.

Contemporary drawing – the sailing rig was unlikely to have been used except

Contemporary drawing – the sailing rig was unlikely to have been used except

during the initial delivery voyage from Britain to China

Overseas customers were now sought and the first ship of the type was laid down for Chile in 1879 as this nation’s war with Peru and Bolivia was commencing. In the event that war ended before the vessel was completed and she was taken over by the Imperial Japanese Navy as the Tsukushi. She was to serve without distinction in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.Her construction and completion was however overtaken by two generally similar vessels for another Far Eastern customer when an order was placed by China. In the early 1880s the corrupt and floundering Chinese Empire was wakening up to the threats posed by growing Russian and Japanese power on its northern and eastern borders, as well as the pressure from France the south, from what is now Vietnam, and which was to erupt into the Sino-French War of 1885 which ended in a humiliating Chinese defeat. The need for a strong navy to protect China’s long coastline was obvious but corruption and inefficiency was to make progress in this spasmodic and inconsistent. A few ships of limited capacity could be built at the Foochow Dockyard and equipped with imported guns, but the majority were contracted from European sources, German as well as British, resulting in a wide variety of calibres of guns and munitions.

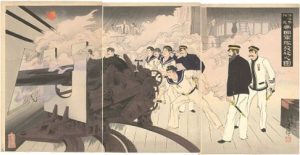

Japanese view of the Battle of the Yalu, 1897

Japanese view of the Battle of the Yalu, 1897

One of the superb woodblock prints made in Japan at the time

The two Chinese “Rendel cruisers”, named Yang Wei and Chao Yung, were built by Charles Mitchell & Co. in Newcastle-on-Tyne. They were of a mere 1350 tons, length 220 feet and beam of 32 feet. Two compound engines, each of 1300 HP, ensured a maximum speed of 16 knots, a respectable speed at a time when the Royal Navy’s HMS Iris, then entering service, was regarded as a marvel for achieving just under 18 knots. Like HMS Iris, the Chinese cruisers were of all-steel construction, which was also an innovation, but their most remarkable feature was their armament. Each ship carried two 10-inch Armstrong breech-loaders, one forward, one aft. There were mounted so as to pivot inside fixed steel drums, armoured shutters being raised to allow bearing on limited arcs ahead and astern (45 °) and on either side (70 °). In addition each ship carried four 4.7 – inch breech-loaders, two on each broadside, as well as what would have been a fearsome collection of Gatling and Nordenvelt guns’ for protection against torpedo boats. The hulls had only low freeboard fore and aft and had to be built up for the delivery voyage from Britain to China. A simple fore and aft rig was carried to supplement the engines and was probably of most use during delivery. Like Royal Navy ships of the period – notably HMS Inflexible – electricity generation on shipboard represented a major innovation, allowing incandescent light fixtures, including arc searchlights. Hydraulic steering was another innovation – and perhaps a needless complication.

Chinese ensign, initially triangular, later a rectangle

The Yang Wei and Chao Yung entered service in 1881. Though spasmodic efforts were made to fashion the Chinese Navy into an effective force, the state of unrest, corruption and reluctance to challenge traditional thinking meant that the process was never effective. This was by comparison with the fast-modernising Empire of Japan, which already had ambitions to dominate the Far East and set out to build a powerful navy on the model of the Royal Navy. Japanese naval development was based on coherent planning, with the emphasis not only on the necessary “hardware” – the ships and weapons – but also on “software aspects” – structured organisation, training plans and an ethos of professionalism and pride. By contrast the Chinese navy acquired ships on a random and piecemeal basis, without reference to any single coherent plan. Corruption was rife and the navy was divided into as many as four different “fleets” which at any time might, or might not, cooperate with each other.

Chinese cruiser Chao Yung_1894

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 announced Japan’s arrival as a major power on the world stage and resulted in humiliating defeats of Chinese forces by both land and sea. By the time of the war’s outbreak, the Yang Wei and Chao Yung were in a very poor state of maintenance, little more than half their original top speed being achievable and probably several of their weapons being unserviceable. Extensive use of wooden partitioning, overlain with layers of varnish, made them particularly vulnerable to onboard-fire. The concept of the large but slow-loading gun-armament on a small vessel with limited armoured protection was by now overtaken by the development of smaller-calibre quick-loading weapons. In addition, lack of professionalism and corruption so serious that there were rumours of munitions being sold off by officers had made the Chinese Navy a hopeless adversary against the super-efficient Japanese.

Japanese cruisers in action at the Battle of the Yalu – note Chinese ships burning

In the key Battle of the Yalu on 17th September 1894 both the Yang Wei and the Chao Yung were placed in the Chinese line of battle. They were subjected to a hail of explosive 6-inch and 4.7-inch shells from the Japanese cruisers involved and both vessels were soon engulfed in flames as the wooden fittings took light.

The Yang Wei’s and Chao Yung’s Nemesis – Japanese guns in action

With her steering damaged the Yang Wei collided with the German-built Chinese cruiser Jiyuan and sank in shallow water, as did the Chao Yung, which may have been trying to save itself by beaching. It was a sad end for two vessels which in their time were mistakenly regarded as being at the cutting edge of naval development.

Britannia’s Spartan The early days of the Imperial Japanese Navy are an important element of this volume of the Dawlish Chronicles series, thhe main action being in the period April – August 1882.

The early days of the Imperial Japanese Navy are an important element of this volume of the Dawlish Chronicles series, thhe main action being in the period April – August 1882.

Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

Dawlish has no forewarning of the nightmare of riot, treachery, massacre and battle he and his crew will encounter.

A new balance of power is emerging in the Far East. Imperial China, weak and corrupt, is challenged by a rapidly modernising Japan, while Russia threatens from the north. They all need to control Korea, a kingdom frozen in time and reluctant to emerge from centuries of isolation.

Dawlish finds himself a critical player in a complex political powder keg. He must take account of a weak Korean king and his shrewd queen, of murderous palace intrigue, of a powerbroker who seems more American than Chinese and a Japanese naval captain whom he will come to despise and admire in equal measure. And he will have no one to turn to for guidance…

Britannia’s Spartan sees Dawlish drawn into his fiercest battles yet on sea and land. Daring and initiative havealready brought him rapid advancement and he hungers for more. But is he at last out of his depth?

Available in paperback and Kindle formats. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra charge. Details for purchase below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Imperial Chinese Navy’s doomed “Rendel Cruisers” appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 27, 2025

Nelson and Hardy – the forging of a partnership

The frigate HMS Blanche was famous for a furious “single ship action” in January 1795, in the middle years of the Revolutionary War between Britain and France. In it she captured the French frigate Pique, off Guadeloupe Blanche, a 32-gun frigate, had still four years of life ahead of her before she was wrecked in 1799 and these involved considerable drama, in which two of the best known naval heroes of the era, Nelson and Hardy, were to play roles.

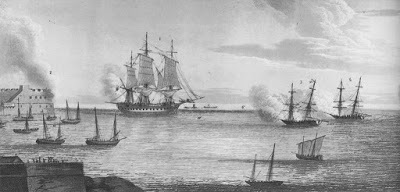

End of the Blanche (L) vs. Pique action – both ships in states not unusual after such combats – Painting by John Thomas Baines with Acknowledgement to National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Blanche’s captain, Robert Faulknor, had been killed in the Pique action and was succeeded by a Captain Charles Sawyer, who took her to Portsmouth for a refit and thereafter to the Mediterranean at the end of 1795. This theatre was to prove a difficult one for the Royal Navy in the following year, but for Sawyer personally it was to prove a personal disaster.

The Articles of War, under which Royal Navy ships operated, were merciless as regards punishment of homosexual acts, with the death penalty itself reserved for sodomy. The offence would have been regarded as even more serious if it involved a commissioned officer. It appears that Captain Sawyer had gained a reputation among his crew for such behaviour – accusations were made as regards relations with two young midshipmen, his coxswain and an ordinary seaman. The offence was compounded by the fact that the captain of a ship at sea represented absolute authority and that there was an assumption that this would be exercised fairly and conscientiously. A captain was to be respected, as well as on-occasion feared, and in Sawyer’s defence in this respect was wholly forfeited as his behaviour was common knowledge on board. Discipline deteriorated to the extent that Blanche’s first lieutenant, Archibald Cowan, wrote about it to the area commodore, Horatio Nelson. This step took considerable moral courage. To criticise a superior in this way was dangerous in the extreme as it could be construed as insubordination and lead to the quick ending of a career, if not worse.

Nelson in 1796

In the event the matter was handled with considerable pragmatism and adroitness, and indeed with humanity also. A charge of sodomy against a commissioned officer, which would involve embarrassing evidence that would be most likely challenged and debated, would have done nothing for the prestige of the service, and might have had a terrible outcome for Sawyer personally. The charge brought against him in the unavoidable court-martial was related instead to the breakdown of discipline, specifying “odious misconduct, and for not taking public notice of mutinous expressions muttered against him“. Sawyer was found guilty in October 1796 and dismissed from the service.

Even before the court-martial was convened a new commander was required for the Blanche. This was to be Captain D’Arcy Preston, who was faced with the challenge of restoring discipline and respect for the chain of command. That he was successful in this was to be shown a few months later, in December 1796, when Blanche once more found herself in action.

During the year Britain’s position in the Mediterranean had weakened considerably in the face of French successes in Italy and Corsica. The Mediterranean Fleet commander, Sir John Jervis, took the unwelcome but realistic decision in October 1796 to withdraw to Gibraltar after evacuating British forces from Corsica and Elba. Nelson was to take charge of the latter operation and to initiate it he sailed from Gibraltar in December with two frigates, HMS Minerve and HMS Blanche. Minerve had previously been French, having captured in June 1795 by the frigates HMS Dido and Lowestoffe. Nelson was on board Minerve and her second lieutenant was Thomas Masterman Hardy (1769-1839), who was to play a very significant role in Nelson’s life – and death – such that the names of Nelson and Hardy are often still linked in the public mind.

Capture of Minerve 1795 – Thomas Sutherland (engraver), Thoams Whitcombe (artist)

On 10th December, two Spanish frigates were spotted in the vicinity of Cartagena. These proved to be the Sabina and Matilde, each of 40 guns, fair matches for the British ships. Sabina was the flagship of Commodore Don Jacobo Stuart, a descendent in the illegitimate line of James II of England.

Minerve engaged Sabina while the Blanche concentrated on holding off Matilde. After a three-hour combat, during which she lost her mainmast, and had her fore and mizzen badly damaged, Sabrina surrendered. Minerve had also been damaged, but her masts still stood. One has the impression, as so often in the case of frigate to frigate actions, of the British gunnery being markedly superior.

Sabrina was the boarded by a 40-man prize crew headed by Minerve’s first and second lieutenants , John Culverhouse and Thomas Hardy but her damage was such as to necessitate her being towed by Minerve. At this point the second Spanish ship, Matilde, re-entered the fray and attacked Minerve. She was driven off but a new Spanish force now appeared, the 112-gun ship-of-the-line Príncipe de Asturias and two frigates. Nelson realised that there was no hope of fighting this larger force, especially not if Minerve had Sabrina in tow. He took the unpalatable decision of cutting the tow and abandoning Sabrina and her prize crew to the advancing Spanish.

Lieutenants Culverhouse and Hardy were to be prisoners of war for little over a month. Nelson was eager to have them back and he sent a message through to the Spanish authorities at Cartagena that he was prepared to exchange them for Don Jacobo Stuart. A pleasing statement in the letter was that “I have endeavoured to make the captivity of Don Jacobo Stuart, her brave Commander, as light as possible; and I trust to the generosity of your nation for its being reciprocal for the British officers and men.” The exchange was duly arranged and the two lieutenants arrived in Gibraltar at the end of January 1797.

Both men re-joined Minerve but on 11th February, shortly after leaving Gibraltar to join Sir John Jervis’s fleet, she was pursued by Spanish vessels. In the course of the chase a seaman fell overboard and Hardy was dropped with a jolly boat to rescue him. The unfortunate man could not be found and strong currents swept Hardy’s craft far from Minerve so that his re-capture by the Spanish now became a distinct possibility. Despite the danger of engagement with a superior force Nelson exclaimed “By God, I’ll not lose Hardy! Back that mizzen topsail!” so that Minerve could drift down on Hardy’s boat and pick him up. The manoeuvre succeeded and, once sail was made again , Minerve’s superior speed drew her away from danger.

The Battle of Cape Saint Vincent, Richard Brydges Beechey, 1881

The Battle of Cape Saint Vincent, Richard Brydges Beechey, 1881

During the night that followed Minerve found herself in fog and sailing between dark shapes. These were those of the Spanish fleet but ineffective lookouts did not detect her. By morning she was clear and on her way to Jervis with news of the enemy fleet’s location. The scene was now set for Jervis’s victory over the Spanish at Cape St. Vincent two days later.

Jervis’s exchanges with Captains Robert Calder and Benjamin Hallowell on the quarterdeck of his flagship, HMS Victory, were recorded as it was discovered that his force was outnumbered almost two-to-one:

“There are eight sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty-five sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty-seven sail of the line, Sir John”

“Enough, sir, no more of that; the die is cast, and if there are fifty sail I will go through them”

It was in HMS Victory that Nelson himself was to die eight years later. His admiration of Hardy had grown in this time. At the Battle of the Nile in 1798 Hardy commanded the corvette Mutine and when Nelson sent his flag captain back with news of the triumph he promoted Hardy to command his flagship HMS Vanguard. When Nelson shifted his flag to HMS Foudroyant he took Hardy with him.

In 1801 Hardy was again to be Nelson’s flag captain and he distinguished himself at the Battle of Copenhagen by surveying the route whereby the British fleet would enter the Danish anchorage. The relationship continued and in the period leading up to Trafalgar Hardy was not only flag captain of Nelson’s HMS Victory, but de-facto captain of the fleet. It was a meteoric but well-merited rise.

The death of Nelson in the cockpit of HMS Victory – the iconic image: Hardy takes his leave

Hardy as Admiral

Given the warmth and respect between these two men it was appropriate that Hardy should be with Nelson when he was shot down at Trafalgar in 1805. As Nelson lay dying in Victory’s cockpit Hardy brought him news of the succession of French surrenders and when they came to part Nelson’s request was “Kiss me, Hardy”, which he did on the cheek. Nelson was by this time fading and Hardy kissed him a second time, this time on the forehead. The dying man asked “Who is that?” and, when told who it was, said “God bless you Hardy” – his last words.

The young lieutenant whom Nelson had once been forced to abandon, and whom he had once risked everything to save on another occasion, had come a long way in nine years. A long, varied and honourable career awaited him after Trafalgar, culminating in his appointment as First Naval Lord, the professional head of the navy, in November 1830.

The (re)capture of HMS Minerve, aground off Cherbourg, July 1803

The (re)capture of HMS Minerve, aground off Cherbourg, July 1803

One other player in this drama was also to have a dramatic further career. HMS Minerve , which had been captured from the French in 1795 ,was recaptured by them when she ran aground in a fog off Cherbourg in 1803. She was recommissioned in the French Navy as the Canonnière and saw active service in the Philippines, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. By 1809 she was considered worn out and was sold at Mauritius for merchant service, now renamed Confiance. She was captured by the Royal Navy in 1810 – as she was carrying goods worth £150,000 she was an exceptionally valuable prize and must have made the fortune of many of the crew of HMS Valiant, the ship that took her. Commissioned once more into the Royal Navy, this time as HMS Confiance, she saw little further service and was disposed of in 1814.

New Book by Antoine Vanner – his first non-fictionBroadside and BoardingSmall scale action in the Age of Fighting Sail 1740 – 1815 Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

This new book refers to an earlier era, the Great Age of Fighting Sail that spanned the years 1740 – 1815. It tells largely forgotten real-life stories of small-scale actions, not of the great fleet battles like Trafalgar. Many involve little more than a handful of resolute men fighting their own lonely and desperate battles, small epics that still inspire.

Broadside and Boarding is not a formal history but a collection of some eighty articles. Reading times vary from ten to fifteen minutes. They’re ideal for coffee or tea breaks, for when one is waiting for a train or flight, for delays of all kinds and for when mood precludes a prolonged reading session. This is a book that belongs on bedside tables and in guest rooms, in cars’ glove compartments or, in Kindle format, in briefcases and handbags, always readily accessible.

Uncovering these stories demanded searches not just in classic and near-contemporary histories of the time but in smaller and obscure books perhaps unopened for decades. In many cases there are direct quotes from reports or letters written in the immedate aftermath of the events involved. These are often touching and sometimes inspirational, bridging the centuries through recognition of our shared humanity.

Click links below for details.USA UK and Ireland Canada Australia and New ZealandThe post Nelson and Hardy – the forging of a partnership appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 20, 2025

HMS Eden and Liner SS France Disaster June 1916

I have always admired – and been somewhat disturbed by – Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Convergence of the Twain” in which he meditated on how the Titanic and the iceberg that was to sink her were brought separately into existence, and how they met for one decisive moment:

I was rminded of this poem, and of the terrible image of inexorable, unforgiving destiny which it evokes, when I read recently of the collision of two vessels four years after the Titanic disaster. Collisions at sea occur even in our own day, and did so much more frequently in the days before radar, so at first glance there was nothing unusual about this event. What did strike me however was that the two vessels involved were so dissimilar – one the epitome of luxury, the other’s accommodation so Spartan that its crew was entitled to compensation for their discomfort.

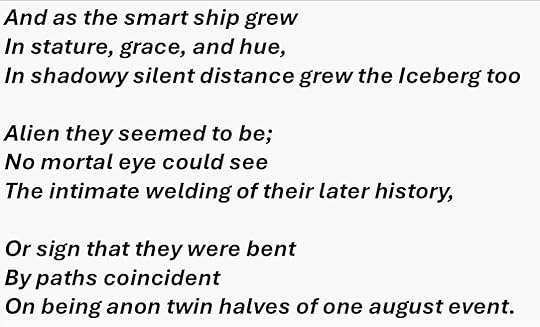

SS France in her full glory

In the early years of the twentieth century giant ocean liners were as much symbols of national pride as they were means of mass transportation. Ever larger and more luxurious British and German liners competed on the North Atlantic but it was not until 1912 – “Titanic Year” – that France was to provide a worthy competitor. She was named, with obvious pride, the SS France, a 712-foot long vessel capable of carrying 2020 passengers. Driven by four Parsons steam turbines of total 45,000-hp – the first such units installed in a French passenger ship – she was capable of a top speed of 23.5 knots. Like the foreign liners she would compete with, she carried the ultimate status symbol of the era – a dummy fourth funnel.

Even before SS France, French liners had a reputation for luxury. The illustration above refer to an earlier vessel, SS La Provence of 1905

At 24,666-tons the France was smaller than her British and German competitors – her Cunard contemporary, the Lusitania was of 44,060-tons – but what she lacked in size was more than made up for by the unprecedented luxuriousness of her accommodation. Her first-class interiors, decorated in style Louis Quatorze were perhaps the most opulent on any liner, resulting in the nickname of “The Versailles of the Atlantic”.

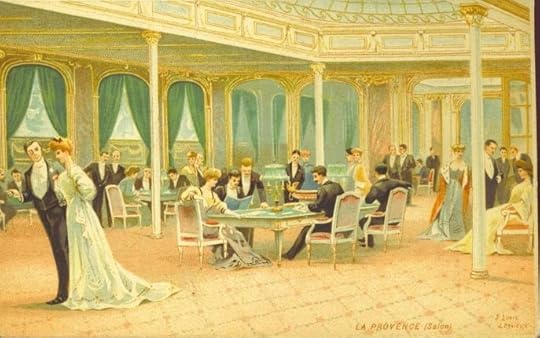

First Class music room on SS France

Salon on SS France. Note fireplace and portrait of the “Sun King”

The ship with which the France’s destiny would “converge”, in Hardy’s phrase, could not have been more different. HMS Eden was one of thirty-four destroyers of the “River Class” commissioned into the Royal Navy between 1903 and 1905 (the sheer numbers of vessels in the navy of this period is remarkable by modern standards). One of only three of these ships to be driven by turbines, the Eden’s installed 7000-hp drove her at a maximum of 25.5 knots. On her 550-tons and her 226-foot length she carried four 12-pounder guns and a half-dozen smaller, these being primarily intended for use against other destroyers and torpedo craft. Her two 18-inch torpedo tubes would make her a threat to larger enemy vessels in any fleet action. Accommodation of her 70 strong crew was by necessity basic – her beam was a mere 24 feet – and like all destroyer crews of the period they were entitled to “Hard Lying Money” as a compensation.

HMS Eden

HMS Eden’s career was to be spent in home-waters. Even before outbreak of war she was to prove an unlucky ship for in 1910 she broke loose from her moorings in Dover harbour in story weather and sank. She was refloated and returned to service thereafter.

HMS Eden sunken at Dover 1910

The France’s career on the North Atlantic was cut short after two years by the commencement of World War 1. She was taken into naval service – initially, and unsuitably due to her high coal consumption, as an armed merchant cruiser and thereafter as a troop carrier. HMS Eden meanwhile had been assigned to “The Dover Patrol”, the British naval force tasked with ensuring the safe passage of men and materials between Britain and France across the English Channel. The success of the Dover Patrol in keeping losses to a minimum, despite the presence of German U-boats operating out of bases on the nearby Belgian coast, was one of the Royal Navy’s most remarkable achievements in World War 1.

It was in the early hours of 18th June 1916 that the convergence of this twain was to occur in the English Channel, off the French port of Fécamp on the Normandy coast. Wartime conditions inevitably meant manoeuvring with limited lighting of ships and collision was a constant danger. The consequences for HMS Eden were fatal, her 550 tons no match for the France’s more than 40-times times greater tonnage. The Eden’s commander, Lieutenant A.C.N. Farquhar, and 42 officers and men went down with her and 33 survivors were picked up by the France. Within the larger scale of World War 1, and occurring only three weeks after the Battle of Jutland, HMS Eden’s tragedy was quickly forgotten by all but the families of those who had perished.

The France in service as a hospital ship in the Mediterranean

Essentially undamaged, the France went on with busy war service. The sinking in late 1915 of Titanic’s sister, the Britannic, which had been converted to a hospital ship, demanded provision of another ship of high capacity. This need was to be met by the France and she was to serve in this role in the Mediterranean until entry of the United States into the war increased the demand for troop transportation. The France once again changed role and as a trooper proved capable of carrying up to 5000 men at a time across the Atlantic, shipping them to Europe in 1918 and back home in 1919. One suspects that the comfort level for these troops was substantially lower than for the 2020 passengers she would carry in peacetime. She went back into commercial service from 1920 to 1932 and was broken up in 1935.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest:Britannia’s InnocentTypical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post HMS Eden and Liner SS France Disaster June 1916 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 5, 2025

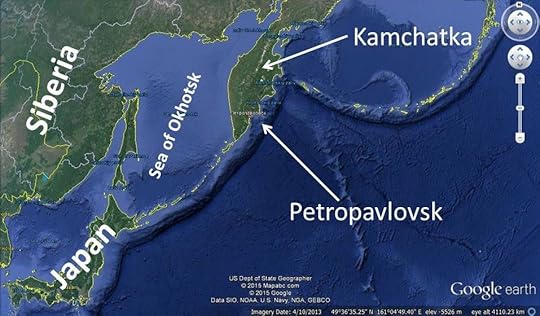

Petropavlovsk, August 1854: The Crimean War’s remotest theatre

The most common image of the Crimean War (1854 – 56) is of Britain’s Light Brigade charging to death and glory against Russian guns at Balaclava. Almost equally well known are the epics of the ”Thin Red Line” and of the Storming of the Redan, both in the Crimea itself. The more nautically- minded may think of the enormous and costly expedition to the Baltic that earned such scanty returns. Few have however heard of the most remote operation of the war, the Anglo-French assault on Petropavlovsk, Russia’s Northern Pacific port on the Kamchatka peninsula.

Even for Russians the word “Kamchatka” signified the back of beyond, difficult to the point of near impossibility to reach by land from European Russia. The Trans-Siberian railway had not yet been thought of and would not to be completed for another five decades and the only realistic way of supplying the settlements there was by sea. Kamchatka is a vast peninsula – almost 100,000 square miles – and contains some 160 volcanoes, 29 of them active today – and it is all but cut off from the rest of Siberia by the Sea of Okhotsk. In 1854 Russian presence there was scarcely a century old and the town of Petropavlovsk, founded by the navigator Vitus Bering (of “Strait” fame) in 1740, was important not only as an ice-free port but as a transit point for contact with Russian Alaska. Russia’s interest in Alaska was however never more than lukewarm and its potential was never recognised. It was to be sold to the United States at a knock-down price some thirteen years later.

Petropavlovsk is situated on what a Victorian writer described as “one of the noblest bays in the whole world—glorious Avatcha Bay”. By 1854 the city possessed an almost landlocked harbour, with a sand-spit protecting it from all fear of gales or sudden squalls. The shelter it offered, and its freedom from winter ice, made it an ideal maritime base, and in more recent times has been used as such by the Soviet and Russian Federation Pacific Fleets.

Petropavlovsk in 1856 – at the war’s end

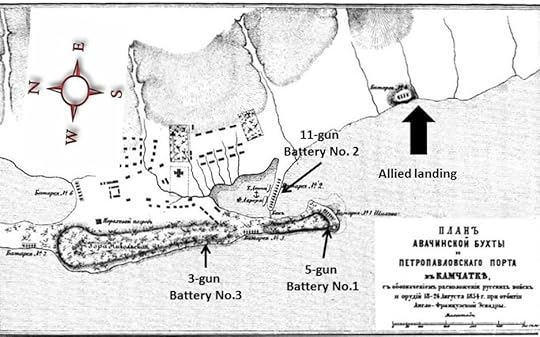

When Britain, France, Turkey and Piedmont went to war with Russia in 1854 the main theatres of war were to be the Crimea and the Baltic, both offering access by sea. Destruction of the Crimean naval base at Sevastopol and of the Russian fortifications in the Aland Islands, were seen as strategically significant and desirable. It is however impossible to understand how an expedition against Petropavlovsk could ever have been imagined to have any significant impact on the war. Even if held, the occupying force had nowhere else to go and the only Russians inconvenienced would be the two or three thousand engaged in trading in Alaska. Despite this it was decided that a not-inconsiderable Anglo-French force should be sent against Petropavlovsk. This consisted of six vessels, the Royal Navy’s HMS President (Frigate, 38 guns), HMS Virago (paddle sloop, 6 guns), and HMS Pique (frigate, 36 guns), plus the French La Fort(frigate, 60 guns), Eurydice (corvette, 32-guns), and Obligado (sloop, 32 guns). As only Virago was steam driven the force was in effect little different from one that might have set to sea in the Napoleonic Wars four decades only. The British commander, the 64-year old Rear-Admiral David Price was himself a veteran of that latter period, having been just promoted after 39 years as a post captain. The French force was under a Rear-Admiral Auguste Febvrier-Despointes and, as always in allied operations, the potential for miscommunication and confusion was significant. On paper the Allied force carried some 200 guns, though as almost entirely consisting of broadside ships only half this number could be brought to bear at any one time.

HMS Virago – the only steam ship in the Allied force (with acknowledgement to the Australian War Memorial)

The Anglo-French force entered Avatcha Bay on August 28th 1854 (by the Western calendar) and the less wind-dependent Virago was sent to reconnoitre. The town – little more than a village – was protected from the outer bay by a long narrow peninsula on the west, and a sand bank on the east. Vessels passing between these entered the inner harbour and the passage could be closed by a chain. Protective batteries had been located as shown by superimpositions on the contemporary Russian map above – a 5 gun battery at the tip of the peninsula (Battery No.1), an 11 gun battery on the sand bank opposite (Battery No.2) and a 3 gun battery further back along the peninsula (Battery No.3). The total Russian force present amounted to 920 men, seamen as well as soldiers, plus two ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet (indeed almost the entire fleet!), the 44-gun frigate Aurora and the transport Dvina. These were moored inside of the sandpit and effectively protected by Battery No.2, which they supplemented with their own landed guns.

Contemporary Russian Map, with Vanner’s annotations to identify batteries etc.

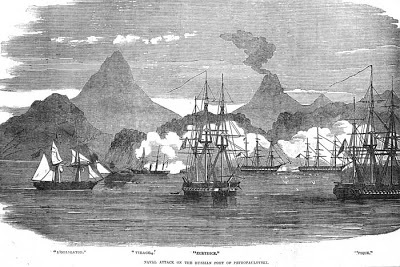

Virago’s reconnaissance complete, the allied force advanced to bombard the town on August 31st. Proceedings were opened by Rear-Admiral Price going below and shooting himself – whether deliberately or by accident, is unknown – leaving British command to devolve to Captain Nicholson of HMS Pique. The bombardment was suspended but on September 4th the force returned, Virago in the lead, followed by La Fort, President and Pique which were to concentrate fire on Battery No.1 while Eurydice and Obligado took on Battery No.3.

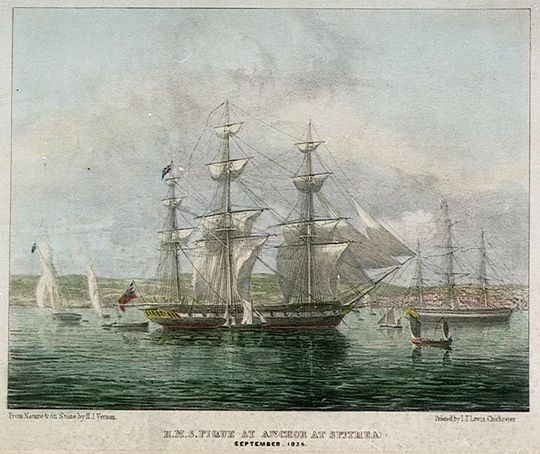

HMS Pique – one of the last sailing frigates, obsolescent when built in 1836

The bombardment proved successful and both batteries were silenced (an unusual occurrence when ships were pitted against shore batteries – indeed Nelson himself had warned that “A ship’s a fool to fight a fort”). Engaging Battery No2 on the sand spit closing off the inner harbour was however a more difficult proposition since insufficient room was available to being all the Allied ships’ guns to bear on it. Taking the town therefore meant landing men. It was however shut in by high hills on almost all sides and the only vulnerable point was in the south, outside the harbour, where a small valley opened out on land bordering the bay (see old Russian map above).

Petropavlovsk under bombardment – a contemporary impression

A landing party of some 680 British and French seamen and marines was hurriedly assembled and sent on shore in boats. The landing was unopposed and the Anglo-French force thrust inland in a straggling, ill-coordinated manner. The ground ahead, rising towards a ridge, was littered with scattered bushes and trees, behind which Cossack sharpshooters had been positioned. They opened a withering fire and picked off nearly every Allied officer. The men, not seeing their enemy and having lost their leaders, fell back in panic-stricken disorder. Many had lost their orientation in the brush and a series of small, vicious combats followed, some of the landed force being most likely shot accidentally by their own side. A number fled up a hill at the rear of the town and were hunted down mercilessly by the Cossacks while others died by falling over the steep cliff on one side of the hill. The guns of La Fort, Virago and Obligado covered the main retreat to the boats, but it was clearly a major defeat. The butcher’s bill was 107 British and 101 French dead or wounded out of the 680 landed. The Russians lost half these numbers and held the field. Allied defeat was total.

There was nothing to be done by the Allies to withdraw, smarting. The winter made the prospect of further action unattractive but a return in force was soon being planned for the following year. Unknown to allies they Russians had decided – wisely – that Petropavlovsk was of little value to themselves, and a potential liability for the Allies, should they take it. Accordingly, in early 1855, the Russian garrison was evacuated.

The Allies were meanwhile assembling a more massive force, with ships assigned to it from the China station. The new commander, Rear Admiral Bruce, organised supplies in Hawaii and a huge supply depot and hospital was organised at Esquimalt, near Vancouver to provide further support. On May 30th 1855 the combined Anglo-French flotilla arrived back at Petropavlovsk in thick fog and took up positions in anticipation of an attack. When they fog cleared two days later reconnaissance revealed the town as deserted. Bruce’s force occupied it without a shot being fired. It was to hold the city until the war came to an end in 1856.

Russian cannon of Battery No.3 looking out over the Bay of Avatcha today

The repulse of the Allies at Petropavlovsk was the only Russian success on any front in the Crimean War and as such is remembered better there than in the West. At a tactical level the operation had more in common with the Napoleonic period – sailing vessels, broadside muzzle-loading artillery, improvised landings – than with the era then dawning. The ironclad would arrive within a decade and, fast in its wake, breech-loaders, torpedoes, efficient steam power and ever-improving armour. At a strategic level the operation, whether a tactical success or failure, could only represent a dead-end squandering of lives and resources.

For Britain and France Petropavlovsk was an embarrassment. And that is, perhaps, why we have heard so little of it since.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest:Britannia’s InnocentTypical Review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on block below for details.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting. Click on block below for details.

The post Petropavlovsk, August 1854: The Crimean War’s remotest theatre appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 28, 2025

Discipline and heroism after the loss of HMS Alceste 1817

The aftermath of the wreck of the French frigate Medusa in 1816 is widely regarded as one of the most horrible events in maritime history. Abandoned on an overloaded raft by officers and crew, who took to the boats when the vessel grounded off the coast of modern Mauritania, only fifteen persons survived out of a total of 147. In the thirteen days the raft drifted, 132 died through thirst and starvation, fighting and suicide. Cannibalism sustained the survivors. Though the ship’s boats had reached safety no systematic search was made for the raft and it was only discovered, accidentally, by the British ship Argus. A major scandal at the time, the raft became the subject of an unforgettable painting by Théodore Géricault (1791-1824).

[image error]

“The Raft of the Medusa” – today in the Louvre, ParisThe breakdown in responsibility and discipline that led to this appalling disaster can be contrasted with the happy outcome of what could have been a similar tragedy when a Royal Navy frigate, HMS Alceste, was wrecked the following year. The value of professionalism and discipline has seldom been so dramatically illustrated.

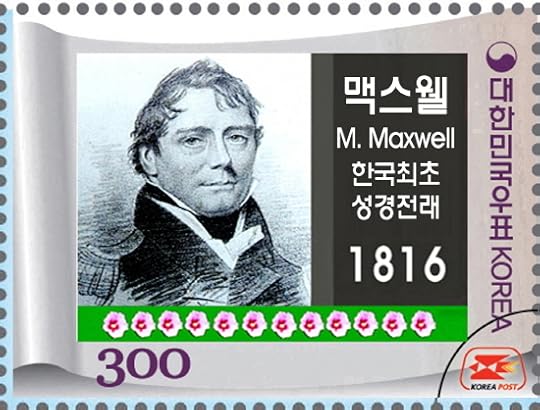

HMS Alceste was built in 1804, as the Minerve, for the French Navy and generally similar to the Medusa. Two years later she was captured by the Royal Navy and taken into service as HMS Alceste, under command of Captain (afterwards Sir) Murray Maxwell, (1775 –1831). He was to be her captain for much of her Royal Navy career until her final loss. In 1811, in company with HMS Active, Maxwell and the Alceste captured the French frigate Pomome. Maxwell was to be congratulated on this in strange and unforeseeable circumstances six years later. HMSAlceste provided sterling service through the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars and in the War of 1812.

Painting by Pierre Julien Gilbert (1783-1860)

In 1816 HMS Alceste was assigned to carrying William Pitt Amehurst, the first Lord Amherst, on a diplomatic mission to China, the objective being to establish formal relations between Britain and the Chinese Empire. Amehurst was landed at Canton (Guangzhou) and travelled overland to Pekin (Beijing). In his absence, Captain Maxwell and HMS Alceste undertook extensive survey work in uncharted waters off the coasts of China, Korea, and Okinawa. This work is so well thought of, even today, that Maxwell has been honoured by a South Korean postage stamp.

On her return to China HMS Alceste required repairs to ready her for the long voyage home. This necessitated mooring in calm water in the Pearl River, close to Canton. A request to do so was refused by the Chinese authorities, who threatened to have the gun-batteries guarding the river open on HMS Alceste should she proceed. Captain Maxwell responded in the robust manner to be expected of the Royal Navy of his day – he bombarded and subdued the shore defences and some seventeen war-junks supporting them. He then moored, commenced his repairs and awaited Amehurst’s return.

As depicted by Alceste’s surgeon, John MacLeod, in his account of her final voyage

In the event Amehurst’s mission proved to be a total failure, doomed as it was by mutual incomprehension. Self-sufficient for millennia, China officials had little or no understanding of the outside world and regarded all other nations as inferior. Amehurst was informed that he could only be admitted to the Emperor’s presence if he were to kowtow – which meant kneeling and bowing so low as to touching the forehead on the ground. As representative of a proud nation that had opposed the might of France and her allies for over twenty years, and which had the previous year seen off the Emperor Napoleon, Amehurst had no intention of abasing himself or his country. Faced with an impasse, he had no option to head home. He rejoined HMS Alceste and she set out for England, he and his entourage, plus the frigates crew, adding up to 257 on board.

Disaster struck in the Java Sea – an area largely uncharted at the time. Despite continuous soundings, HMS Alceste ran onto a hidden reef on 18 February 1817, the damage so severe that the flooding was too much for the pumps to handle. Abandonment was now essential, the nearest island, Pulau Liat, being close enough for crew and passengers to be transferred safely to shore. In an uncanny resemblance to the Medusa wreck, a raft was used in the evacuation in addition to the ship’s boats. On this occasion however, order and discipline prevailed. Provisions and freshwater were at a premium however and it was decided that the boats would head for Batavia (now Djakarta), the Dutch administrative centre in Java, 200 miles to the south, to organise a rescue. Amehurst joined them.

Engraving from one of Surgeon Macleod’s illustrations

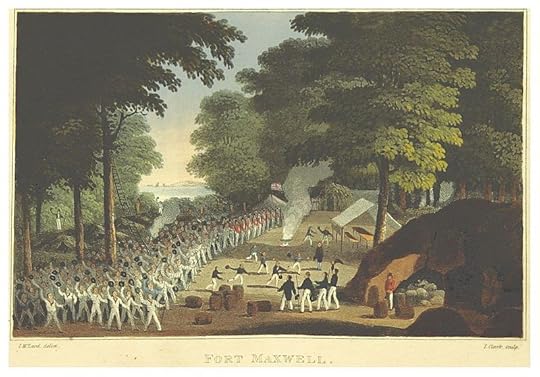

Captain Maxwell had remained on the island and now organised a return to the wreck to recover whatever supplies remained as there were still some 200 mouths to feed. The attempt was interrupted by the arrival of Malay pirates and the salvage party, which had been unarmed, had to beat a hasty retreat. The pirates looted the wreck and burned it thereafter. Fearing further pirate attack, Maxwell supervised construction of a stockade – called appropriately “Camp Maxwell” – and readied it for defence. Another salvage party managed to recover some flour and wine from the Alceste’s burned-out hulk but the supplies-situation remained critical.

The anticipated pirate attack came on 26 February. A sortie led by Alceste’s second lieutenant led to an initial repulse – with several pirates killed – but further pirate reinforcements arrived thereafter. They made no attempt to land, contenting themselves with firing swivel guns towards the stockade. Yet more pirates arrived and on 1 March an assault, which promised to be overwhelming, seemed imminent. It was at this critical juncture that a ship was seen approaching. Her appearance, and a brief attack by Alceste’s marines, broke the pirates’ resolve and they fled. The vessel turned out to be an East-Indiaman, the Ternate, which Amehurst had encountered in Batavia. It was to here she returned the castaways – not a single life had been lost – and Amehurst chartered another ship, the Caesar, to take them back to Britain.

An engraving from one of Surgeon MacLeod’s illustrations

The Caesar put in to St. Helena on her voyage home and both Amehurst and Maxwell had an audience with the ex-Emperor Napoleon, now in his second year of exile there. Napoleon complimented Maxwell on his achievement and hoped that he would be exonerated (as he was to be) in the inevitable court-martial for her loss. He also referred admiringly – and sportingly – to Maxwell’s capture of the French Pomone in 1811. It was to Amehurst, when discussing his failed mission, that Napoleon made his celebrated remark “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep. For when she wakes, she will shake the world” – a prophesy which has to come to pass in our own day.

Maxwell was rightly hailed as a hero, was knighted in 1818. He was however seriously injured by a paving stone thrown from a mob opposing him when he stood for Parliament that same year. He returned to naval service and held a number of responsible positions but he never recovered from the paving stone injury. He died at 56 – too young. Amherst was to serve as Governor-General of India from 1823 to 1828.

And now, when we admire Géricault’s “Raft of the Medusa” we should remember the Alceste also. She and her gallant crew deserve it.

New Book by Antoine Vanner – his first non-fiction titleBroadside and BoardingSmall scale action in the Age of Fighting Sail 1740 – 1815 Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

This new book refers to an earlier era, the Great Age of Fighting Sail that spanned the years 1740 – 1815. It tells largely forgotten real-life stories of small-scale actions, not of the great fleet battles like Trafalgar. Many involve little more than a handful of resolute men fighting their own lonely and desperate battles, small epics that still inspire.

Broadside and Boarding is not a formal history but a collection of some eighty articles. Reading times vary from ten to fifteen minutes. They’re ideal for coffee or tea breaks, for when one is waiting for a train or flight, for delays of all kinds and for when mood precludes a prolonged reading session. This is a book that belongs on bedside tables and in guest rooms, in cars’ glove compartments or, in Kindle format, in briefcases and handbags, always readily accessible.

Uncovering these stories demanded searches not just in classic and near-contemporary histories of the time but in smaller and obscure books perhaps unopened for decades. In many cases there are direct quotes from reports or letters written in the immedate aftermath of the events involved. These are often touching and sometimes inspirational, bridging the centuries through recognition of our shared humanity.

Publication date, Kindle and Paperback, is December 7th 2024Kindle editon available for preorder at 25% discocount on later published price. Click links below for details.USA UK and Ireland Canada Australia and New ZealandThe post Discipline and heroism after the loss of HMS Alceste 1817 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 26, 2024

Britannia’s Wolf audio-book

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Britannia’s Wolf audio-book appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

Blast from the past 3

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Blast from the past 3 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

Blast from the past 2

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Blast from the past 2 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 13, 2024

Blast from the past

Britannia’s Wolf is also available as an audio-book. It’s been read by the distinguished American actor David Doersch. If you haven’t previously ordered an audio-book from audible.com you can download it without cost as part of a 30-Day Free Trial. You can listen on your Smart Phone, Tablet or MP3 Player. Click here for details.

The post Blast from the past appeared first on dawlish chronicles.