Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 9

September 16, 2022

Hell and High Water: HMS Nautilus, Part 1

Hell and High Water: HMS Nautilus, 1807Part 1

Hell and High Water: HMS Nautilus, 1807Part 1In November 1806 a Royal Navy squadron commanded by Admiral Sir John Duckworth (1748 – 1817) was sent to reconnoitre the Dardanelles as a preliminary for a move against Constantinople (now Istanbul) in what would be the Anglo-Turkish War of 1807-1809. Attached to the force was an 18-gun sloop, HMS Nautilus, launched in 1804 and captained by a twenty-six year old officer named Palmer (Does anybody know more about him?)

Though this painting by Antoine Roux (1765-1835) is of a French brig, HMS Nautilus would have looked generally similar

On January 3rd 1807 HMS Nautilus was sent to Britain with despatches. Driven by a strong north-easterly and guided by a Greek pilot, she safely navigated through the cluster of Aegean Islands between Greece and Anatolia. When the pilot stated however that the had now passed his point of knowledge of the area, Palmer himself now took charge. By this stage he seemed to have been exhausted, having hardly slept for three nights, and, after setting a course on the chart for his coxswain, George Smith, to follow, went to bed. The wind was beginning to strengthen but, though the night was very dark, Palmer had been satisfied that constant lightning on the horizon provided sufficient illumination to identify any land ahead.

HMS Zebra – a typical Royal Navy brig of war, by Giovanni Schranz (1794-1882)

Under light sail, and with a following sea, HMS Nautilus was estimated to be making over nine knots. Around two-thirty in the morning, high land was detected ahead, and believed to be the island of Antikythera, between Crete and Peloponnese. HMS Nautilus’s course was altered to pass and she drove on for two hours until a look-out warned of breakers ahead. It was too late – the ship struck violently. Those below hurried on deck – water was already surging into the aftermost past of the hull.

Captain Palmer appeared, ensured calm, and went with his second lieutenant to inspect the damage. He saw that the situation was hopeless and he returned to his cabin to burn his papers and private signals. The sea was now lifting the hull and smashing it down again repeatedly on the rocks so that the decks became untenable and the crew – HMS Nautilus carried a total of 122 officers and men – were forced up the rigging to survive.

The lightning had ceased by now and the darkness was almost total. It was only a matter of time before the ship would break up completely. All boats were smashed but a whaler (whale-boat in American parlance) hanging over the quarter survived. In this an officer, George Smith the coxswain, and nine men, got away. For those left on board HMS Nautilus the only hope of survival lay in getting to the exposed rocks. Just before daybreak the mainmast fell over, falling towards the rocks, and this provided a bridge across which to scramble. By this stage several men had been drowned, and others were injured, but Palmer refused to cross until the last man had left. He was injured in the attempt and was dragged over by several seamen who came to his rescue.

The rock on which they found themselves was likely to be overwhelmed by the waves and safety now lay in wading to a larger rock. The first lieutenant managed to get across the intervening channel and encouraged the remainder to follow, the passage being made all the more dangerous by wreckage from the ship being carried through the channel by the waves. Many were injured while crossing and those not wearing shoes – this was an era when seamen worked barefoot – had their feet lacerated.

The survivors found with daylight that they were on a rocky outcrop, some 400 yards long and 200 wide, barely above water level. No other land was visible and the only hope now was that the whaler that had got away had survived, and the possibility that it might fetch assistance from a nearby Greek island.

The horror of shipwreck, as overcame HMS Nautilus, by Franciszek Ksawery Lampi (1782 – 1852)

Cold was now a major problem – there had been ice on the deck the previous day – but by using a flint and steel, and some damp gunpowder from a washed-up barrel, a fire was got going. A shelter was constructed of scraps of canvas and other flotsam. A signal was hoisted on a pole in the hope that a passing vessel would spot it.

The whaler had indeed survived and, despite a high sea, managed to reach what proved to be the island of Pera. Just a mile across, it was uninhabited but for a few sheep and goats belonging to the people of the nearby island of Kythira who came across in summer to take their young away. No fresh water could be found other than a small accumulation of rain. While the whaler had been underway, its occupants had seen the fire lit by the other survivors and the coxswain, George Smith, persuaded four of those with him to go back to them. (The 19th Century account on which this article is based makes no mention of what became of the officer in the whaler).

On the second morning after the shipwreck, Smith and the whaler reached the survivors on the rock. The surf was still too high to get in close but Smith hoped to take few men off. He called Captain Palmer to make the attempt but he refused, saying, “No, Smith, save your unfortunate shipmates, never mind me.” He asked however that the Greek pilot should be taken on board in the hope that he could help Smith reach Kythira, where he knew some families of fishermen. The pilot did manage to reach the whaler, and all hope now depended on it as it departed.

Escaping a wreck – as HMS Nautilus’s whaler did – painting by Hendrik Adolf Schaep (1826 – 1870)

The wind was rising again and dark clouds indicated a gathering storm. When it struck, it was with fury, lashing waves over much of the rock and dousing the fire. The survivors – approximately ninety of them – moved to the highest point but even here the surf threatened to drag them away despite by passing a rope around a protrusion to hang on to. Starving, many were by now at the end of their strength and became delirious and could hold on no longer. Others died through the following night of cold and of injuries sustained earlier.

Hope rose at daybreak when a ship under sail was seen heading towards the rock. Identifying the signals of distress, it hove to and dropped a boat. The survivors tried to fashion rafts to carry them through the surf to it. The boat “came within pistol-shot, full of men dressed in the European fashion, who after having gazed at them a few minutes, the person who steered, waved his hat to them and then rowed off to his ship,” thereby abandoning them. The disappointment was made yet more bitter when the unknown ship was seen picking up pieces of HMS Nautilus’s wreckage from the water before sailing away. The identity of the ship, and its nationality, have never been established. It is clear however that it was not a British vessel.

And here, at the end of Part 1, we leave Captain Palmer and the remaining survivors starving and dying of exposure on the rock, and the valiant whaler seeking assistance. What happened next will be told in Part 2 of this article, due next week.

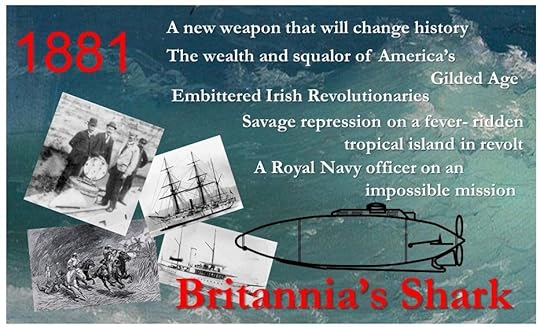

Naval fiction enters the Age of Fighting SteamSince its original publication, the Dawlish Chronicles novel Britannia’s Spartan has consistently scored 5-star reviewsFor more details, click on the image belowThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting …Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle, tablet or iPhone, Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and it facilitates e-mail contact between Antoine Vanner and his readers.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Hell and High Water: HMS Nautilus, Part 1 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 26, 2022

The Battle of Heligoland 1864

War in the North Sea, 1864 – The Battle of Heligoland

War in the North Sea, 1864 – The Battle of Heligoland

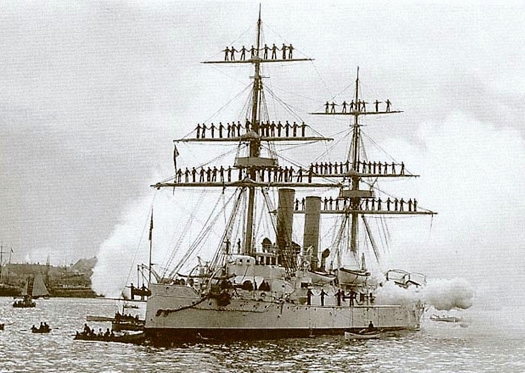

Tegetthoff

In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries the “K.u.K” – “Imperial and Royal” – Navy was probably the most efficient and well-equipped part of the Austro-Hungarian armed services. Operating out of bases on the Adriatic coast of what would later become Yugoslavia, and well provided with excellent ships, armed with the highly-regarded products of the Skoda arsenals in Bohemia, this navy was to represent a potent threat “in being” during World War 1 which tied up large Allied naval resources to contain it. The navy only became “Austro-Hungarian” in 1867 when the “Dual Monarchy” was formally established but the navy had existed since 1815 as the “Austrian Navy.” Its day of greatest glory was however almost a half-century before World War 1, when Austria-Hungary’s most famous admiral, Wilhelm von Tegetthoff (1827 –1871) led his fleet to an overwhelming victory over the Italians at Lissa in 1866. A daring and inspirational commander who was to die tragically young, Tegetthoff established a reputation in Austro-Hungarian popular consciousness which was comparable to that of Nelson in Britain. His success at Lissa was however preceded by a narrow tactical defeat two years earlier, not in the Austrian Navy’s normal operational area of the Adriatic and Mediterranean, but in the distant waters of the North Sea at the Battle of Heligoland 1864.

The Danish War of 1864 was to be the first of three conflicts deliberately instigated by Prussia’s chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, in the 1864 -1870 period to establish the primacy of Prussia over the other separate German Kingdoms and to unite them as a single empire under Prussian leadership. The ostensible reason for the war with Denmark was resolution of “The Schleswig-Holstein Question”, the control of two linguistically-German duchies lying directly south of modern Denmark and at that period under Danish control. The political, dynastic and diplomatic complexities of this “Question” were so impenetrable that the British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, was to quip that “Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business—the Prince Consort, who is dead—a German professor, who has gone mad—and I, who have forgotten all about it.”

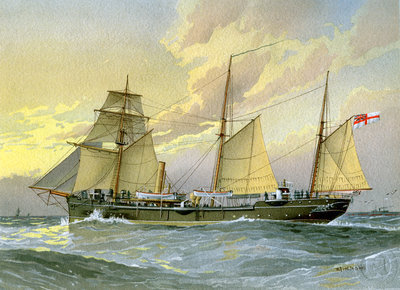

The Danish screw-frigate Jylland – wooden-hulled, steam and sail-driven, 44 guns

The Danish screw-frigate Jylland – wooden-hulled, steam and sail-driven, 44 guns

Though it was to put up a valiant defence, the small Kingdom of Denmark was to find itself heavily outnumbered and outgunned by the combined land forces of Prussia and Austria. The latter had allowed itself to be drawn into the conflict – stupidly as it was to find out two years later, when Prussia was to attack it in turn. It was only at sea that the Danes were to have a degree of superiority since it had a well-equipped and competent navy, whereas Prussia still had negligible naval forces – little more than a gunboat flotilla – and the more formidable Austrian Navy was operating far from its home bases in the Adriatic. The Danes were to use their resources effectively in support of land operations as well as imposing a blockade on Prussian ports.

[image error]

The most significant encounter of the short-duration (effectively February – May 1864) war was to occur close to its end, when significant naval forces clashed close to the then British-controlled island of Heligoland.

The most significant encounter of the short-duration (effectively February – May 1864) war was to occur close to its end, when significant naval forces clashed close to the then British-controlled island of Heligoland.

Heligoland – exchanged by Britain with Germany for Zanzibar in 1890

Heligoland – exchanged by Britain with Germany for Zanzibar in 1890

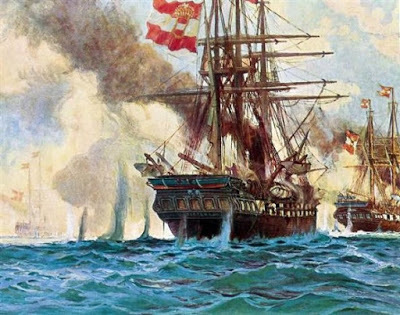

On May 9th a squadron of three powerful Danish vessels under the command of Admiral Edouard Suenson – the 42/44-gun screw frigates, Niels Juel and Jylland, supported by the 16-gun screw corvette Hejmdal – approaching from the north, sighted the neutral British frigate HMS Aurora on station off the island. Beyond her however, to the south-west, five other vessels came into view. These were the powerful Austrian screw frigates Schwarzenberg (51 guns) and Radetzky (37-guns), accompanied by three insignificant Prussian gunboats mounting three or for guns each. This squadron was under Tegetthoff’s overall command.

The Niels Juel in action – superb battle-painting by Christian Mølsted (1862-1930)

The Niels Juel in action – superb battle-painting by Christian Mølsted (1862-1930)

Both forces advanced to engage and at 13.15 hours the action commenced when Tegetthoff’s flagship, the Schwarzenberg, opened fire. This was returned by the Danes only when the range had shortened to a mile. An attempt by Tegetthoff to execute the classic “crossing the T” manoeuvre failed. Had it been successful it would have allowed his two vessels to concentrate their combined broadsides on the Danes’ lead ship. Instead, a Danish turn allowed the squadrons to pass each other in line. By this stage the three Prussian gunboats had fallen behind and Tegetthoff turned to prevent them being cut off by the Danes. This brought the opposing squadrons running south-westwards in two parallel lines. The Niels Juel concentrated her fire on the Schwarzenberg, while Jylland and Hejmdal directed theirs on the Radetzky.

Schwartzenberg, burning, leading the Austrian line, Danish ships on right of painting

Schwartzenberg, burning, leading the Austrian line, Danish ships on right of painting

The action lasted for some two hours and culminated in the Schwarzenberg sustaining such serious damage that she took fire. With her loss a definite possibility, Tegetthoff decided to make for the neutral zone around Heligoland. The pursuit by the Danes had to be abandoned as the British Aurora, which had observed the action, was standing by to enforce neutrality if so needed. There was no option but to remain outside the three-mile limit while Tegetthoff managed to get the fire on the flagship under control. In the course of the following night he managed to evade the Danish squadron and bring his ships to the nearby Prussian-controlled port of Cuxhaven.

Radetsky following Schwartzenberg – painting by German naval artist Willy Kirchner

Radetsky following Schwartzenberg – painting by German naval artist Willy Kirchner

The action was generally judged to be – narrowly – a Danish tactical victory. The butcher’s bill had been small – 17 Danes killed and 37 wounded as compared with 37 dead and 93 wounded on the Austrian ships – though the losses would have been bitter indeed for the families of the men involved. Victory or defeat was irrelevant however. Three days later, on May 12th, an armistice was implemented which brought the fighting by land and by sea to an end. By the subsequent settlement Denmark lost control of the two duchies in contention and they were in due course incorporated into what became the German Empire. One was returned to Denmark after World War 1, a conflict in which the nation had been neutral.

The Jylland’s officers after the battle (note the dog!)

The Jylland’s officers after the battle (note the dog!)

Denmark may have lost the war, but her resistance had been heroic and considerable national pride is still taken in it, justifiably so. The 2400-ton Jylland, one of the largest wooden warships ever built, and which had sustained major damage in the battle, has been preserved as a national monument. She is today on display in a dry dock at Ebeltoft.

This engagement off Heligoland was to prove the last major action before iron and steel replaced wood as the main construction material for ships. When Tegetthoff was to go into action again two years later – this time during a war which would pit Austria against its former ally Prussia, as well as against Italy – it was to be in a battle dominated by ironclads. On that occasion there would be no doubt as to who had gained victory, whether it tactical or strategic or both.

This war of 1864 is the background to Britannia’s Innocent, Start the 10-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the earliest chronologically of the Dawlish Chronicles 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish volunteers to support Denmark. He is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – not to mention divided loyalties . . .

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and ordering. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and ordering. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The Battle of Heligoland 1864 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 19, 2022

The Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807

The Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807

The Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807The three-year “War of 1812“between Britain and the United States, brought no great benefit to either nation. Though the issues involved were complex, one in particular, the British claim of the right to search neutral vessels for deserters from the Royal Navy, had the power to trigger American outrage and breathe new life into resentments that harked back to the War of Independence and before. Though it was not until 1812 that the United States declared war, the issue of recovering deserters had almost brought the two nations into conflict five years earlier, in what became known as the Chesapeake – Leopard Incident.

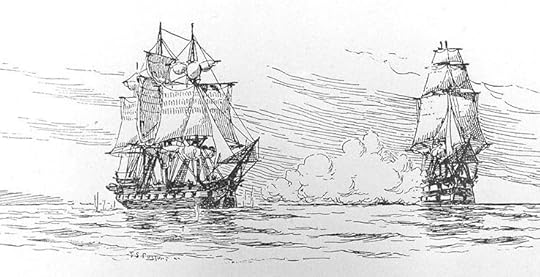

The action between HMS Leopard (r) and the USS Chesapeake (Drawing by Fred S. Cozzens)

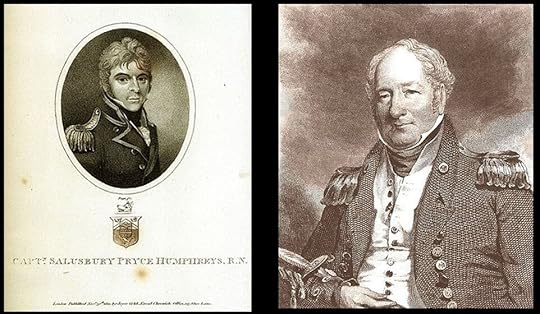

In 1807 news reached the British base at Halifax, Nova Scotia, that several Royal Navy deserters had been accepted into service on the American frigate USS Chesapeake. In what might be considered an over-reaction, the station commander despatched the 50-gun frigate HMS Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys (1778-1845), to bring orders to the captains of other vessels of the British squadron off the American coast. They were to insist on the right to search the Chesapeake for deserters should they fall in with her outside the territorial waters of the United States. In the event, it was HMS Leopard herself that was to make the demand.

Humphreys and Barron – the two captains whose lives were to be changed by their encounter

Launched in 1785, the 50-gun fourth-rate HMS Leopard (fourth rates occupied an ambiguous position between frigates and ships-of-the-line) had had a useful but undistinguished career since the outbreak of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. (She was to have a fictional as well as an actual career before her loss by grounding in 1814, for Captain Jack Aubrey was to command her in Patrick O’Brian’s novel Desolation Island.)

[image error]

USS Chesapeake – one of the US Navy’s original “Six-Frigates”

Having delivered her despatches, HMS Leopard was lying with the rest of the British squadron off the Hampton Roads when the USS Chesapeake was sighted on June 1st 1807, en route to the Mediterranean. The squadron commodore signalled HMS Leopard to detain her. The American captain, James Barron (1768-1851), did not appear to sense anything untoward – both nations were at peace. When HMS Leopard hailed to say that she carried message from the British commander-in-chief, Barron, replied “Send it on board—I will heave to.” HMS Leopard’s first lieutenant went across and when the matter of deserters was raised Barron stated that he had no such men on board.

Chesapeake’s reply to Leopard

After the lieutenant had returned to the Leopard, Captain Humphries again hailed the Chesapeake. He did not consider the answer satisfactory and saw that there were signs of preparation for action on the American ship. To emphasise his demands he now ordered a shot to be fired across her bow. He continued firing at two-minute intervals. Increasingly frustrated by what he considered evasive answers from Barron, which he thought were only to gain time, he at last ordered fire to be opened in earnest. After receiving three broadsides, and after replying with only a few shots, the Chesapeake struck her colours. An American lieutenant came across with a verbal message from Barron, stating that he considered his ship to be HMS Leopard’s prize.

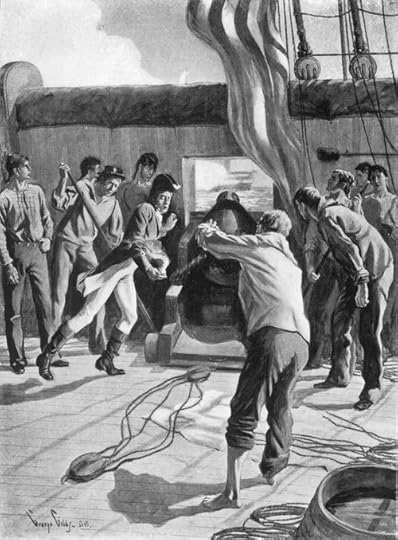

Captain Humphries did not accept the Chesapeake as a prize but he did send two of his lieutenants across, with several petty officers and men, to search for the deserters. One seaman, who was dragged out of the coal-hole, was recognised as Jenkin Ratford, a deserter from HMS Halifax. Three others were found, who had deserted from HMS Melampus, and about twelve more from various British warships. The first four were however to only ones to be brought across to the Leopard. Now – and quite bizarrely – Barron again offered to deliver up the Chesapeake as a prize. Captain Humphreys told him however that he had fulfilled his own instructions and that the American ship was free to proceed. He regretted having been compelled to attack and offered all the assistance in his power.

Barron tries to surrender USS Chesapeake as a prize

The Chesapeake had suffered severely from HMS Leopard’s broadsides. Twenty-two shot were lodged in her hull and her masts and rigging were badly damaged. She had lost three seamen killed, while Barron, one midshipman, and sixteen seamen and marines had been wounded. Since the Chesapeake was all but unready for battle, Barron’s unwillingness to continue the engagement was understandable if not necessarily heroic.

When HMS Leopard arrived at Halifax, the unfortunate Jenkin Ratford was found guilty of mutiny and desertion, and was hanged at the foreyard-arm of the ship from which he had deserted. The three other men, though found guilty of desertion, were initially sentenced to 500 lashes, but they had their sentence commuted and were later allowed to return to America.

It was inevitable that the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair would trigger outrage and demands for war in the United States. Protracted diplomatic negotiations failed to reach a mutually satisfactory outcome – Britain indeed reaffirmed its claim to right of impressment. As a sop to American feeling however, Captain Humphreys of HMS Leopard was given no further commands. The United States backed off from declaring war but President Thomas Jefferson resorted to economic warfare by means of a trade embargo that was aimed as much against France as against Britain.

The career of James Barron of the Chesapeake was also ruined. He was court-martialled in January 1808 on the charge of not having his ship ready for action and he was suspended for five years without pay. Though this ended in 1812, the Navy refused his requests to be accepted back for service during the war that began that year. One of the members of the court was Stephen Decatur (1779 –1820) and Barron appears to have held a grudge against him thereafter. Bad blood between the two men escalated to the extent of Barron challenging Decatur, now a national hero, to a duel with pistols in 1820. Both men were hit and badly wounded. As they were carried from the field Barron called out “God bless you, Decatur” and Decatur replied in a weak voice “Farewell, farewell, Barron.” Decatur died of his wound but Barron survived. It was a sad and futile postscript to the Leopard – Chesapeake affair.

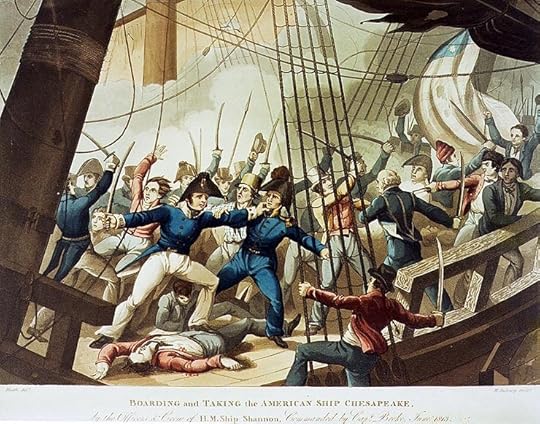

Contemporary print: HMS Shanon’s crew boarding USS Chesapeake in 1813

By that time USS Chesapeake herself was a thing of the past. She was captured by HMS Shannon after an epic duel on June 1st 1813, exactly six years after her encounter with HMS Leopard. Taken into Royal Navy service as HMS Chesapeake, was broken up in 1819. Some of her timbers are now incorporated in the structure of the Chesapeake Mill emporium in Wickham, Hampshire.

Naval fiction enters the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 4, 2022

Battle of Ushant 1778 – its farcical aftermath, the guillotine and a “Citizen King”

The indecisive Battle of Ushant 1778 – and its farcical aftermath, the guillotine and a “Citizen King”

The indecisive Battle of Ushant 1778 – and its farcical aftermath, the guillotine and a “Citizen King”France’s entry into the American War of Independence was to prove a critical factor is assuring the survival of the United States. It did so by winning the only strategically-significant victory in all French naval history – that off the Virginia Capes in 1781, which starved British forces at Yorktown of supplies and made their surrender unavoidable. The unforeseen cost to the French monarchy of supporting this upstart republic founded on democratic principles was however to be enormous. French officers returned from America with the conviction that France’s governmental system was rotten and unsustainable. Once that fact was widely recognised revolution was inevitable and the whole bloody process would commence in 1789. The opening event in the sequence, the Battle of Ushant 1778, was to have a farcical aftermath and be the first step towards the guillotine for one of the main players, and to the throne of France for his son.

The British surrender at Yorktown – made inevitable by a French naval victory

The driver for France’s involvement in the war was the adage that “My enemy’s enemy is my friend” (an often-dangerous assumption, as it was in this case) and the objective was to strike at Britain, the old enemy with which she had fought a long sequence of wars over the hundred years. France’s supply of arms to the American rebels and her formal recognition of the United States in February 1778 made it inevitable that Britain would declare war on France in the following month. The initial confrontations had to be naval, since control of sea routes to and from North America was essential for both sides.

Bien-Aimé, typical 74, in First Division of French White Squadtron at Ushant, by François Roux

Bien-Aimé, typical 74, in First Division of French White Squadtron at Ushant, by François Roux

Admiral Keppel by Sir Joshua Reynolds

France possessed a fleet in the Mediterranean and a second, based at Brest in Brittany, to operate in Atlantic and Channel waters. An important strategic decision for Britain was concentrating its resources in the Channel Fleet so as to blockade French forces at Brest. By doing so, attacks on merchant shipping to and from Britain, and any French attempt at mounting an invasion, could be countered. The situation changed however when a French naval force slipped out of the Mediterranean and headed for the Americas. There was no option but to detach forces from the Channel Fleet to follow this force. This still left the French and British navies in rough numeric balance in and off Brest and made a French break-out more feasible.

The Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet was commanded by Admiral Augustus Keppel (1725 – 1786), who can be described as competent but not brilliant. Like many officers of the era he had a parallel political career as a Member of Parliament and bad blood existed between him, as a committed Whig, and the First Lord of the Admiralty, the Navy’s professional head and a dedicated member of the opposing group known as “The King’s Friends”. The depth of bitterness was such that Keppel feared that the First Lord would be glad for him to be defeated. Further bad feeling existed between Keppel and one of his subordinate admirals, Sir Hugh Palliser (1723–1796), another politically active officer and previously a member of the Admiralty Board, which Keppel blamed for the running down of the Royal Navy in the aftermath of the Seven Years War. These personal enmities did not bode well for mutual trust and cooperation in the heat of battle.

British line at Ushant: HMS Foudroyant, identified in print block third from right, was captained by Sir John Jervis, later Viscount St. Vincent

The clash – the first major naval action of the war – came on 23rd July some 100 miles west of Ushant, a small island off the coast of Brittany. The numbers of ships on both sides were large and all but equal. The British force consisted of 29 ships of the line and faced 30 similar French ships and two smaller ones. The French held the weather-gage – that is, they were upwind of their opponents, a usually critical advantage in the age of Sail – but this was largely nullified by the orders given to the French commander, Admiral Comte d’Orvilliers (1708 – 1792) to avoid battle. (The concept of “a fleet in being” had existed since the late 17th Century). The result was to pit two fleets against each other, one of which had a less than unified command while the other was commanded by an admiral who was instructed not to fight.

Battle of Ushant by Theodore Guediin, painted circa 1848

Note British and French lines passing on opposite tacks

Shifting winds and a heavy rain squall made weather conditions unfavourable as the British force manoeuvred to bring itself parallel to the French, and on the same course, while maintaining a less-than perfect column – inevitable under the circumstances. The French objective was however to escape rather than give battle. Wearing – a reversal of course – brought the French on an opposite course and still to windward. Fire was opened and the head of the British column – led by HMS Victory, whose greatest triumph was still 27 years in the future – sustained little damage but the rearmost division, commanded by Admiral Palliser, was battered more heavily as the French passed. Keppel signalled for the British column to wear so as to follow the French. For whatever reason, Palliser to not comply. The result was that the French fleet escaped. Neither side had lost a ship but the butcher’s bill was heavy nonetheless. The British lost 407 men killed and 789 wounded while the corresponding figures for the French were 126 and 413.

The massive 90-gun Ville de Paris was present at Ushant, but was captured by Britain in 1782

The massive 90-gun Ville de Paris was present at Ushant, but was captured by Britain in 1782

Bitter recriminations followed on both sides. Keppel praised Palliser in his official report but staged a campaign against him with the support of the Whig press. Palliser responded in kind such that both men all but accused each other of treason. This led to both Keppel and Palliser being court-martialled, both being acquitted, though Palliser was censured. Keppel’s political cronies ensured that he became in due course an undistinguished First Lord of the Admiralty while Palliser’s career continued with no great distinction. The whole affair had done nothing for the morale of the service or for the good of the country.

d’Orleans a.k.a. “Philippe Égalité”

The aftermath of the battle on the French side had more of farce than of drama about it. One of the officers serving in d’Orvilliers’ fleet was Louis Philippe d’Orléans, Duc de Chatres (1747 – 1793), who belonged to a junior branch of the Bourbon family and thus a relative of the reigning King Louis XVI. He was to be better known to history as “Philippe Égalité” but that lay in the future when he was despatched to the Palace of Versailles with news of the battle. He arrived in the early morning hours, had the king woken, and provided a highly coloured account that represented the action as a French victory. The news spread and when Louis Philippe attended the opera he was greeted with a twenty-minute standing ovation. This was followed up by burning of Keppel’s effigy in the garden of Louis Philippe’s home in the Palais Royale. Glowing with pride after this reception, he returned to Brest only to find that more accurate accounts were now being issued which made it very plain that there had been no victory. Deeply embarrassed, and quickly made a figure of ridicule, he had no option but to resign from the navy. He succeeded to the title of Duc d’Orleans in 1785 and was now next in line to succeed to the throne should the direct royal line die out. He thereafter got embroiled in bitter enmity and mutual loathing with Queen Marie-Antoinette. She regarded him as treacherous and hypocritical, and he regarded her as frivolous and extravagant. (Both assessments were essentially correct).

In the years leading up to the revolution that would break out in 1789 d’Orleans allied himself with the movement for reform, reinforcing the anti-royalist image he had had for some time. This might be regarded as an early example of “radical chic” and d’Orleans made his residence, the Palais Royale, available for meetings of the extremist Jacobin Club. He gained sufficient popularity that when the Paris mob invaded the Palace of Versailles in October 1789 the cry was heard of “Long live our King d’Orléans!” In the four years of revolution that followed, a bewildering period of upheaval and shifting alliances, d’Orleans renounced his titles to become Citizen Philippe Égalité (Equality) and a member of the Constituent Assembly. When King Louis XVI was put on trial for his life in January 1793, Philippe Égalité to voted for his cousin’s execution.

Execution of Louis VVI, January 1793 – Philippe Égalité voted for it

He died himself on the same scaffold ten months later

“Citizen King” Louis Philippe in 1842

For all his identification with republican ideals, Philippe Égalité was not however to survive long in the snake-pit of revolutionary turmoil. As the Reign of Terror took hold he was to be another of those consumed by the revolution they had brought about. He went to the guillotine in November 1793, doing so however with dignity and calmness that did him credit.

Philippe Égalité, had he lived to know it, had the last laugh. The Second French Revolution, in 1830, brought his son (1773 – 1850) to the throne as King Louis-Philippe I, who reigned as “The Citizen King” for eighteen years until a Third Revolution, in 1848, deposed him. He lived out his last years once again in exile in England, where he had previously spent the years 1793-1815. His daughter Louise married Leopold, first King of the Belgians in 1832, so that Philippe Égalité’s bloodline runs on today through the monarch who reigns today in Brussels.

It all seems far removed from the farcical aftermath of the Battle of Ushant 1778. One wonders however whether the 533 men killed and the hundreds wounded in it would have appreciated the ironies.

Britannia’s Innocent: The first chronologically of the Dawlish Chronicles Series:In which we meet the 19-year old Nicholas Dawlish on the threshold of promotion to Sub-Lieutenant …

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish volunteers to support Denmark. He is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – not to mention divided loyalties . . .

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auAs with all Dawlish Chronicles novels, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Battle of Ushant 1778 – its farcical aftermath, the guillotine and a “Citizen King” appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 24, 2022

HMS Royal George Salvage

The salvage of HMS Royal George, 1782 – 1844

The salvage of HMS Royal George, 1782 – 1844

HMS Royal George in her glory

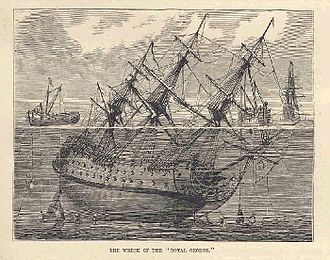

The loss, while at anchor at Spithead, off Portsmouth, of the ship-of-the-line HMS Royal George on August 29th 1782 was a disaster that had an impact on British society comparable to the loss of RMS Titanic one hundred and thirty years later. The catastrophe was described in an earlier article on this site (click here to read it if you missed it then). The sinking was not however the end of the story and the salvage of HMS Royal George, which was to be completed six decades later, was to be an epic in itself and to make innovative use of new diving technology.

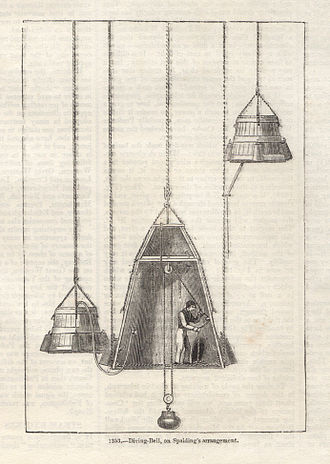

Lying as she was in only sixty-five feet of water, in the middle of a busy anchorage and the approaches to Britain’s largest naval base, this enormous vessel, largely intact, represented a major hazard. The sinking had been witnessed by a surgeon on an East Indiaman, Thomas Spalding, whose brother, Charles Spalding (1738 – 1783) already had experience of using diving bells for salvage operations.

HMS Royal George in the aftermath of her sinking,

Charles Spalding’s Bell – the two smaller bells seemed to have been used for bringing fresh air supplies to the main bell. Note tube running to it from the small bell on the left

Charles Spalding’s Bell – the two smaller bells seemed to have been used for bringing fresh air supplies to the main bell. Note tube running to it from the small bell on the left

Innovative and courageous, Charles originally a confectioner with a shop in Edinburgh, had made significant safety and operational improvements to existing bell designs. Large enough to accommodate two men, and with glass windows to provide light, Spalding’s bell was lowered by a counterweight system – which allowed fast recovery – and had a rope-based signalling system. Thomas Spalding immediately saw that the wreck of HMS Royal George could be an opportunity for his brother. He therefore suggested to the Admiralty that they could recover valuable stores and weapons from her wreck.

Work in progress by the Spaldings – note bells, for which working on the hull was difficult

Work in progress by the Spaldings – note bells, for which working on the hull was difficult

Having gained agreement, the Spaldings got to work quickly. In little over a month – most of October and early November – and despite poor weather, they managed to raise fifteen guns, for which the Admiralty paid £400. It is remarkable that the Spaldings achieved as much as they did – the bell was unsuitable for working on a large object that rose well clear of the seabed. (see illustration) There does however appear to have been a substantial amount of debris on the ground – it is easy to imagine heavy items like cannon breaking free as HMS Royal George heeled over. The Spaldings might have returned to the work after the winter had another, and potentially a more lucrative, opportunity arise. This was the sinking of the East-Indiaman Count de Belgioso on the Kish Bank, outside Dublin. She had been carrying silver and lead – salvage of even a part would have been vastly profitable. In the event the effort proved disastrous – in June 1783 Charles Spalding and a worker with him died in the bell and operations ceased.

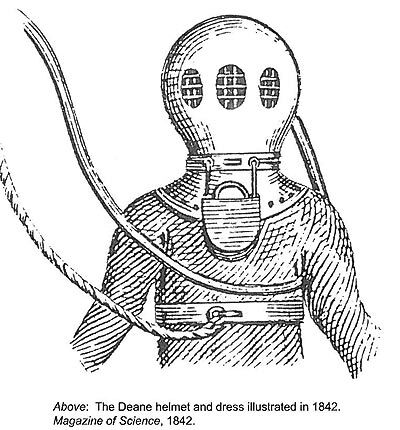

Deane helmet, 1842

The next attempt at salvage had to wait until 1834. By then the first and rudimentary first air-pumped diving helmets had become available, invented by the brothers Deane, Charles Anthony (1796-1848) and John (1800 – 1884). For them too, the Royal George wreck represented an opportunity. By this time the hull had partly disintegrated, making it possible to recover more from the debris. The brothers worked for two years, 1834-36, recovering a total of twenty-eight guns. It proved impossible to reach any more as they were buried beneath mud and shattered hull-timbers. It was during this time that the Deans were asked by local fishermen to investigate another wreck close by that was damaging their nets. The brothers did so and thereby located the Mary Rose, Henry VIII’s flagship that had been lost in 1545. (Sections of the Mary Rose’s hull are on display today at the Portsmouth dockyard).

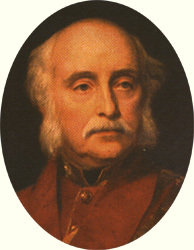

Sir Charles Pasley

The final, and most complete, salvage effort came in 1839 and was to last until 1844. The work was entrusted to the army’s Corps of Royal Engineers under the direction of Colonel (and later General) Charles Pasley (1780-1861). He was systematic, thorough and persistent. Basing his plans on previous demolition of wrecks in the Thames estuary by explosive charges, he determined to blast the remained of HMS Royal George’s hull apart, step by step, and pick up the resulting debris. He had the advantage of air-pumped diving helmets – as developed by the Deanes – as well as having a team of disciplined men as divers. Significant technical progress was also made in underwater blasting. The initial approach was to use gunpowder packed in wooden barrels and sheathed with lead, the detonators being chemical fuses. Given the uncertainty as to how long such detonators would take to explode, placing these charges must have been nerve-racking. Copper cylinders were used later, with electrically-triggered detonation. This allowed a number of such charges to be placed around the wreck and detonated simultaneously from a distance. The largest of the explosions, in 1840, that which finally smashed the remainder of the hull to fragments, was powerful enough to shatter windows in nearby Portsmouth. A total of thirty cannon were recovered, as well as other ironwork, but the chief objective was the removal of the debris as a shipping hazard. An account written in 1877 indicated that the divers were frequently “six to eight hours a day underwater” – if true, it was appalling labour. It was noted that “by long experience they had come to economise time and effort in so skilful a manner, that all of them sent up to the boats in attendance on them their bundles of staves, casks or timber as closely packed together as a woodman would make up his faggots in the open air.”

When Pasley’s team finished work in 1844, the seabed was at last clear of the remains of HMS Royal George, a ship that had proudly flown the flag of Admiral Lord Hawke at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759. Sic transit…

Britannia’s Innocent: The first chronologically of the Dawlish Chronicles Series:Typical 5-star review on Amazon, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.““Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfil his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auAs with all Dawlish Chronicles novels, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Royal George Salvage appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 7, 2022

Training Tragedies – HMS Eurydice & HMS Atalanta

Training Tragedies: the losses ofHMS Eurydice and HMS Atalanta

Training Tragedies: the losses ofHMS Eurydice and HMS Atalanta[image error]

At first glance, the picture of a frigate such as HMS Eurydice, as above, immediately evokes visions of single-ship actions of the Napoleonic period. It is therefore all the more surprising that this ship was still in service in 1878 and that her destruction was witnessed by the young Winston Churchill who would live on to oversee development of Britain’s nuclear deterrent. HMS Eurydice’s story, and that of her successor, HMS Atalanta, are some of the most tragic ever to occur in peacetime service in the Royal Navy.

This begs the question of “Why were such vessels still in service when steam was already established as the most reliable and efficient method of propulsion?”

[image error]

Armoured-cruiser HMS Warspite of 1884 – her sailing rig was removed

Armoured-cruiser HMS Warspite of 1884 – her sailing rig was removed

early in her career and she served thereafter under steam power only

[image error]

Not only the Royal Navy retained sailing rigs.

Here is the American protected cruiser USS Atlanta of 1884

Not only the Royal Navy retained sailing rigs.

Here is the American protected cruiser USS Atlanta of 1884

The answer is that warships in all navies carried sail as well as steam power right up to the end of the 19th Century. Boilers were still inefficient, though improving, and their furnaces were ravenous for coal. For long-distance cruising, away from easy coal supply, retention of sail made sense, even though the presence of masts and yards was likely to be a major point of vulnerability in combat. As innovations in boiler and engine design improved efficiency, and reduced coal demand, the need for sail decreased. In the 1880s sailing rigs were phased out for major vessels but even thereafter retention continued to make sense through the 1890s for smaller craft on remote stations. Typical examples were small, slow gunboats such as those of the Redbreast class, powerfully armed with six 4-inch breech-loaders and ideal for colonial service.

[image error]

HMS Thrush – a Redbreast class gunboat of 1889

HMS Thrush – a Redbreast class gunboat of 1889

Training of officers and men in managing sail as well as steam was therefore of the utmost importance. For many years after steam had replaced sail for all operational purposes there was a strong body of opinion remained that mastery of sail, and of “work aloft”, was essential for character-building, even when this meant training on masts set up on land.

This is the background to the retention of HMS Eurydice as a Royal Navy training ship. She had been built in 1843 as a very fast 26-gun frigate designed with a very shallow draught to operate in coastal waters. Wholly sail-dependent, her design and armament were little different to those of the frigates commanded by captains such as Pellew and Cochrane some four decades earlier. Over the next eighteen years she saw service worldwide, including an uneventful assignment to the White Sea during the Crimean War. She was converted to a stationary training ship in 1861 and remained in this role until re-commissioned as a sea-going vessel in 1877. HMS Eurydice departed on a three-month training cruise to the West Indies in the November of that year, carrying 319 crew and trainees.

Contemporary artist’s impression of HMS Eurydice capsizing

Contemporary artist’s impression of HMS Eurydice capsizing

The cruise appears to have been uneventful. A fast, 18-day, voyage from Bermuda brought HMS Eurydice back to the Isle of Wight by March 24th 1878 prior to entering Portsmouth. At this point she was engulfed in a heavy snow storm and capsized and sank. There were only two survivors as those not brought down in the ship itself died of exposure in the freezing water. Her captain, Captain Marcus Hare, went down with his ship after ordering every man to save himself and then clasping his hands in prayer. The wreck was in shallow enough water for the masts to protrude and it was refloated later in the year. It is not surprising however that this old wooden vessel was past repair and she was accordingly broken up. The subsequent enquiry held her officers and crew blameless and found that the disaster had been caused stress of weather. There was however some concern expressed on the suitability of HMS Eurydice as a training ship because of known concerns as to her stability.

The remains of HMS Eurydice, as Churchill remembered her over five decades later

The remains of HMS Eurydice, as Churchill remembered her over five decades later

Winston Churchill, who was four at the time, was at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight and he witnessed the tragedy. It obviously made a lasting impression on him, as he recounted fifty-two years later in his memoir “My Early Life”:

“One day when we were out on the cliffs near Ventnor, we saw a great splendid ship with all her sails set, passing the shore only a mile or two away… Then all of a sudden there were black clouds and wind and the first drops of a storm, and we just scrambled home without getting wet through. The next time I went out on those cliffs there was no splendid ship in full sail, but three black masts were pointed out to me, sticking up out of the water in a stark way… The divers went down to bring up the corpses. I was told and it made a scar on my mind that some of the divers had fainted with terror at seeing the fish eating the bodies… I seem to have seen some of these corpses towed very slowly by boats one sunny day. There were many people on the cliffs to watch, and we all took off our hats in sorrow.”

Contemporary illustration of salvage efforts.

Note diver (tiny dot) being lowered towards the quarterdeck

Salvage operations in progress

Salvage operations in progress

The poet Gerald Manley Hopkins was sufficiently moved by the tragedy to write very powerfully on “The Loss of the Eurydice”. Space precludes copying his poem in full here but the following verses are especially memorable:

They say who saw one sea-corpse cold

He was all of lovely manly mould,

Every inch a tar,

Of the best we boast our sailors are.

Look, foot to forelock, how all things suit! he

Is strung by duty, is strained to beauty,

And brown-as-dawning-skinned

With brine and shine and whirling wind.

O his nimble finger, his gnarled grip!

Leagues, leagues of seamanship

Slumber in these forsaken

Bones, this sinew, and will not waken.

It is normal – today more than ever – to state solemnly after every disaster that “Lessons have been learned” though in practice this seldom seems to happen. This was especially the case in the aftermath of the Eurydice catastrophe. The Admiralty proceeded to replace her with HMS Juno, another 26-gun frigate of identical tonnage but slightly less radical hull-lines, built in 1844. She was renamed HMS Atalanta and she made two successful training cruises to the West Indies before disappearing at sea in 1880 with the loss of all 281 crew and trainees while en route from Bermuda to Britain. It was presumed that she sank in a powerful storm which crossed her route a couple of weeks after she sailed. A gunboat HMS Avon did however report that near the Azores “she noticed immense quantities of wreckage floating about… in fact the sea was strewn with spars etc.”

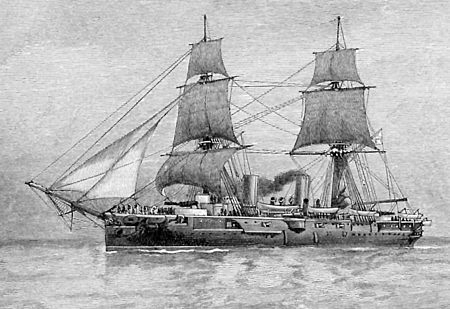

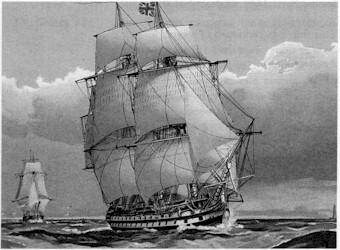

HMS Atalanta

HMS Atalanta

Investigation of the disaster was hampered by lack of evidence but a former crew member stated that “she rolled 32 degrees, and Captain Stirling is reported as having been heard to remark that had she rolled one degree more she must have gone over and foundered. The young sailors were either too timid to go aloft or were incapacitated by sea-sickness.” The witness added that many “hid themselves away” in such circumstances and “could not be found when wanted by the boatswain’s mate.”

The most devastating verdict on the disaster was delivered by The Times, then at the height of its prestige. It denounced “the criminal folly of sending some 300 lads who have never been to sea before in a training ship without a sufficient number of trained an experienced seamen to take charge of her in exceptional circumstances. The ship’s company of the Atalanta numbered only about 11 able seamen, and when we consider that young lads are often afraid to go aloft in a gale to take down sail… a special danger attaching to the Atalanta becomes apparent.”

Both tragedies – claiming 600 lives in two years – shook public confidence in the Royal Navy. A new breed of professional was however emerging, men who understood the demands and opportunities of new technology. Chief among these officers was to be Sir John Fisher, later Lord Fisher, who would create the Dreadnought navy that Britain took into World War 1. It is therefore all the more ironic that one of the officers to lose his life on HMS Atalanta was his younger brother, Lieutenant Phillip Fisher.

HMS Eurydice under sail

HMS Eurydice under sail

Click image for details or to order

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and of a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Click below for details or to order:For US & CanadaFor UK and IrelandFor Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner below for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Training Tragedies – HMS Eurydice & HMS Atalanta appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 30, 2022

HMS Venerable, 1804

Cool Heads in Crisis: HMS Venerable, 1804

Cool Heads in Crisis: HMS Venerable, 1804The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars locked Britain and France into almost twenty-two years of continuous war from 1793 and conflict at sea was a critical part of this. What is surprising however is how few ships were actually destroyed in combat. Whether in large fleet actions or in “single ship” duels, wooden ships tended to survive very heavy damage and could often be repaired sufficiently at sea to get them to port. When captured, such ships were often to get a new lease of life in the victor’s navy. Little use was made of explosive projectiles and though solid shot could inflict severe structural injury above the water-line, it seldom caused outright sinking. The relatively few ships that were lost due to combat mainly succumbed to magazine explosion, or to burning.

Camperdown, 1797 – one of the few fleet actions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

Painting by Thomas Whitcombe (1763 – 1824 ) – Venerable at centre engaging Vrijheid on left

The greatest threat to a wooden warship’s survival came from stormy weather, especially if it were to be cast on a lee shore, where it could be battered to matchwood. One such loss occurred in 1804 when a Royal Navy “74”, HMS Venerable, encountered disaster. Built in 1784, HMS Venerable had played an important role at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797 as Admiral Duncan’s flagship and in assisting in the capture of the Dutch admiral’s flagship Vrijheid.

Much of HMS Venerable’s service – like that of so many other 74s – consisted of participation in the blockade of the French coast – gruelling work, often in atrocious weather conditions, that continued day-in, day-out for months on end. This was never more the case than in 1804-05 when fears of a French invasion were at their height and the Channel Fleet, under Admiral William Cornwallis (1744 –1819), represented Britain’s first line of defence.

On 24th of November, 1804, Cornwallis’s fleet, including HMS Venerable, lay in the large anchorage at Torbay, in Devon. Deteriorating weather conditions, and an onshore gale, caused orders to be given to put to sea. HMS Venerable was under the command of Captain John Hunter (1737 –1821), whose portrait is shown on the left. Hunter had not only had an active naval career but had also served from 1795 to 1800 as the second governor of New South Wales, Australia. There he encouraged exploration and his name is commemorated in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. As governor, Hunter combatted serious abuses of power by the military authorities. In this period a contemporary described Hunter as “devoid of stiff pride, most accomplished in his profession, and, to sum up all, a worthy man.” He is also notable for having sent back to Britain the first known sketch and pelt of a platypus (of which Dr. Stephen Maturin would certainly have approved).

On 24th of November, 1804, Cornwallis’s fleet, including HMS Venerable, lay in the large anchorage at Torbay, in Devon. Deteriorating weather conditions, and an onshore gale, caused orders to be given to put to sea. HMS Venerable was under the command of Captain John Hunter (1737 –1821), whose portrait is shown on the left. Hunter had not only had an active naval career but had also served from 1795 to 1800 as the second governor of New South Wales, Australia. There he encouraged exploration and his name is commemorated in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. As governor, Hunter combatted serious abuses of power by the military authorities. In this period a contemporary described Hunter as “devoid of stiff pride, most accomplished in his profession, and, to sum up all, a worthy man.” He is also notable for having sent back to Britain the first known sketch and pelt of a platypus (of which Dr. Stephen Maturin would certainly have approved).

Darkness was falling as HMS Venerable began raising anchor. The operation went awry however and one seaman was thrown into the sea. The alarm was given and orders were given to drop a cutter to rescue him. In the process, one of the falls suddenly let go and the cutter plunged down into the water and filled. A midshipman and two seamen were drowned but a second cutter managed to rescue others in the water, including the man who had originally fallen overboard.

HMS Mars, a classic “74”. HMS Venerable was generally similar

While this drama was taking place, HMS Venerable was falling away before the gale and found it impossible to exit the bay. She was driven onshore at Paignton, practically at the mid-point of the bay’s semi-circular arc. She was clearly stuck immovably and it could only be a matter of time before she broke up. Orders were given to cut away the masts, in the hopes of their falling between the ship and the shore and so providing an escape route. This proved impossible however as, in grounding, the hull had been canted over away from the land. Captain Hunter remained in full control however – “with undaunted fortitude he continued to animate the crew with hope, and encouraged them to acts of further perseverance, with the same calmness and self-possession as if he were simply conducting the ordinary duties of his ship. From the moment the ship struck, not the least alteration took place in his looks, words, or manner; and everything that the most able and experienced seaman could suggest was done, but in vain.”

HMS Thunderer – another “74” of the era

HMS Venerable’s plight had not gone unnoticed. Two other 74s, HMS Goliath and HMS Impetueux, approached as closely as they dared in the circumstances and a cutter, HMS Frisk, stood in nearer still. Frisk was requested to anchor as close to HMS Venerable as she could so as to receive survivors, carried to her by pulling boats from Goliath and Impetueux.

Discipline prevailed as HMS Venerable’s crew were transferred to the boats and Captain Hunter and his officers declared that they would not leave the ship until the last seaman had been taken off. (It should be noted that at this time Hunter was sixty-seven years old, but this did nothing to decrease his resolution). The sea conditions were now so bad that the rescue boats could only come in under HMS Venerable’s stern, from which men were lowered by ropes. These efforts continued through darkness, raging seas and driving sleet. HMS Venerable was now practically on her beam ends, such that Hunter and his officers were now directing operations while standing – or rather holding on – on the outer side of the hull. All this time, HMS Venerable was pounding on the shore and likely to break up at any moment. It was close enough to the land – some twenty yards – to shout to helpers on shore and a line was eventually secured between them and the ship. Several men attempt to haul themselves to land along it but were plucked away to their deaths by the surf.

HMS Venerable grounded – note hull canted out seawards and conditions in which the rescue boats are operating.

Painting by Robert Dodd (1748 – 1816)

By five o’clock on the morning of the 25th – still dark and with the weather deteriorating yet further – only seventeen seamen remained on the ship with the officers. The sea was breaking over them and the fore part of the ship was wholly submerged. Only then did Captain Hunter order the final evacuation, his officers and himself to follow the men. One by one they dropped into the waiting boats – whose crews had by now been in action in the most dangerous conditions imaginable for more than six hours. Ultimately all, including Hunter himself, were brought across to HMS Impetueux. This was none too soon – shortly afterwards, HMS Venerable broke amidships and the part they had been huddled on capsized. Within sixteen hours of first striking, little remained of the ship but driftwood.

Only a handful of HMS Venerable’s crew were lost. Everybody involved on the Navy side came well out of this disaster – Hunter and his officers, his crew and the men who manned the Frisk and the boats of Goliath and Impetueux. Discipline and training had proved the keys to survival in the most desperate conditions, and the rescue – and the steadiness of officers and seamen alike – speak volumes about morale. Hunter himself was known as a humane and efficient commander and it is likely that this played no small part in his crew’s behaviour in extremis. Less impressive as the role played, or not played, by local people on shore. Not a single civilian boat put out from the fishing communities nearby and, according to a 19th Century commentator, “to add to this disgraceful conduct, the cowardly wretches were observed, when daylight broke, plundering everything of value as it floated ashore.”

It is pleasing to note that Hunter, when court-martialled for the loss of his ship, as he had to be, was fully acquitted. He promoted to rear-admiral two years later and to Vice Admiral in 1810, though he never hoisted his flag at sea. He died in 1821.

Naval Fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Venerable, 1804 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 24, 2022

French oared-galleys in British Waters – 1707

Royal Navy frigate vs. French oared galleys – 1707

Royal Navy frigate vs. French oared galleys – 1707When one thinks of battles involving oared galleys one thinks automatically of actions in the Mediterranean. The lot of a galley slave chained to an oar must have been dreadful enough in the warm and usually calm waters of that sea, but it must have been infinitely worse in the cold, rough waters off the French Atlantic coast and in the North Sea. The galley’s day as a fighting vessel – a long one, stretching back two thousand years – ended in the early eighteenth century and as such they do not figure in most accounts of sea warfare of that era, as “Fighting Sail” reached its apogee of efficiency. I was therefore all the more surprised to come on an account in a Victorian publication of a battle with galleys in the Thames estuary in 1707. This was during the War of Spanish Succession, the last of Louis XIV’s wars, that which began the long decline of French power through much of the remaining century.

A réale galley of Louis XIV’s Mediterranean fleet.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

A réale galley of Louis XIV’s Mediterranean fleet.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Louis XIV (a man much given to his own comfort and luxury, as his creation of the palace at Versailles testifies) appears to have been favourable to use of galleys and ordered that courts should sentence convicted criminals to serve as oarsmen in them as far as possible, even in peacetime. Though the idea was never implemented, he appears to have considered substitution of galley service for the death penalty. Considering that execution in France in this period was by the barbaric method of breaking on the wheel, being chained to an oar would probably have represented a marginally preferable fate.