Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 11

March 3, 2022

Disaster by fire: SS City of Montreal 1887

Loss by fire: SS City of Montreal 1887

Loss by fire: SS City of Montreal 1887The history of maritime passenger transportation in the mid-nineteenth century is, in great part, a depressing catalogue of disasters. Many involved large loss of life and, if not wholly preventable, could have involved far lower death tolls had elementary precautions been observed. It’s therefore all the more heartening to read of the loss in the open sea of a major ship in which the vast majority of passengers and crew survived.

The horror of fire at sea has fascinated Artists, as here, by James Francis Danby (1816–1875)

Credit: Tameside Museums and Galleries Service: The Astley Cheetham Art Collection

Built in Glasgow in 1872, the SS City of Montreal, of the respected Inman Line, was a 4500-ton, 419-foot steamer that also carried a sailing rig, as was common at the time. Given her size it is surprising that her engine was rated as low as 600 horsepower. She was designed to accommodate passengers as well as cargo and she appears to have had an uneventful career on Trans-Atlantic service until 1887. She was neither a fashionable nor luxurious ship and her passengers were classed as “intermediate” (probably equivalent to second-class) and “steerage”, the latter being allocated very basic accommodation indeed. Her captain, F.S. Land, had previously commanded a trans-Atlantic liner, the SS City of Brussels, which had been sunk in collision in a fog off Liverpool some years before.

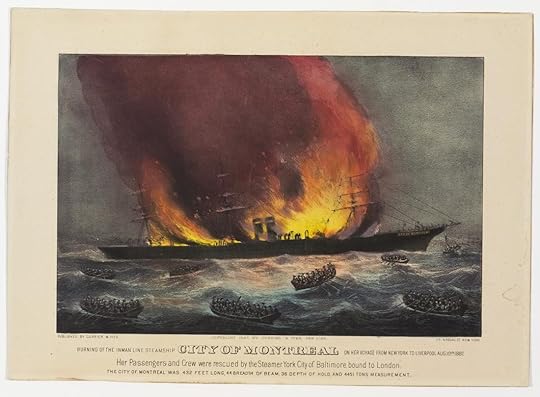

S.S. City of Montreal

Disaster struck on August 10th 1887 when the vessel was some 400 miles east of Newfoundland on a passage from New York to Liverpool with 133 passengers, mostly in steerage, and a crew of 94. She was also carrying 8000 bales of raw cotton, a cargo that was susceptible to spontaneous combustion. One account of the disaster mentions that no less than seventy-two vessels carrying similar cargoes had caught fire in the previous five months – one assumes that in most cases the fires had been got under control. That stronger preventive measures had not been put in place was, unfortunately, symptomatic of the attitude to safety in that era.

In the evening of August 10th cotton was found burning at the lowest level of the City of Montreal’s aft cargo-hold. Hoses were rigged to flood the compartment with water but in the coming hours the flames gained, moving up to the decks above. The majority of the passengers had been settled for the night but as smoke penetrated the cabins they came on deck. One can well imagine their terror. Some progress in fighting the blaze seemed to have been made during the night and Captain Land turned back for St. John’s, Newfoundland, the nearest port. He also ordered boats to be prepared for launching and to be stocked with provisions, but held off doing so as a high sea was now running and many of the crew, who would man the boats, were involved in fighting the blaze. Hopes of survival proved illusory however as fire burst through the after hatch and engulfed the deck.

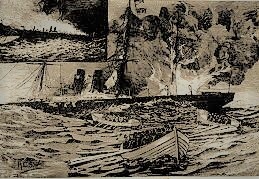

Contemporary artist’s impression: SS City of Montreal burning

Contemporary artist’s impression: SS City of Montreal burning

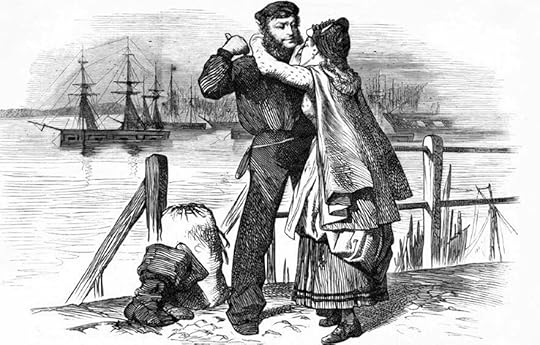

At dawn on August 11th the decision was taken to abandon ship and the passengers were mustered. It is an indication that by 1887, in contrast to disasters in earlier years, some account had been taken of safety and that passengers and crew were equipped with life preservers. An eyewitness, a Rev. J.M. Donaldson from Adelaide, Australia, described the scene: “A picture of human misery and almost helpless despair was presented, such as words cannot adequately describe. Mothers clasped to their bosom, with a fervency proportioned to the danger, their helpless children, husbands and wives embraced each other for what they felt in probability was the last time.”

Contemporary print of the disaster by Currier and Ives

The ship carried four full-sized lifeboats and four smaller craft. Unlike the situation on the Titanic a quarter-century later, there was sufficient room in the boats to accommodate everybody on board – luckily none of the boats had been damaged in the fire. Despite the high sea, the boats were launched successfully and passengers were transferred into them without loss. The Rev. Donaldson noted that “there was no panic, and no attempt was made to evade the rule of ‘women and children first’”. Several passengers and crew were however isolated on the after-part of the ship. Three boats returned and took them off. The captain and his officers had behaved well, both in fighting the fire and in the evacuation, as was recorded in a later testimonial by the passengers. Captain Land himself reported that “The heat and smoke affected my eyes, those of the chief officer and, in fact, those of all who were trying to put out the fire, rendering us all partially blind for some hours. The chief officer was led, totally blind and in great pain, over the side into the ship’s boat and did not get his eye-sight for two days after.”

Contemporary view of the passengers huddled on deck – inset drawing shows Captain Land

As the last boat was due to leave, a barque under full sail was seen bearing down on the burning ship. This proved to be the German Trabant. By the time she arrived the individual boats were widely dispersed and the search initiated for them was continued through the hours of darkness. Further help arrived in the form of the steamer SS York City, en route from Baltimore to London. Seven of the eight boats were recovered after as much as twelve hours in the water. Nobody was lost on any of these boats, despite having endured long buffeting. No trace was found of the last boat, which had seven passengers and six crew on board. The Rev. Donaldson recorded with righteously grim satisfaction that “the persons in charge of this boat, mostly men belonging to the ship, were guilty of gross selfishness, cowardice and inhumanity, going off in a boat half-full, whilst men whom they had seen were left to perish on the burning ship.”

Boats escaping into the night from the burning City of Montreal

The survivors were all gathered on the SS York City and “her manly, kind-hearted Captain Benn.” With the Trabant, she searched fruitlessly for the missing boat but finally abandoned the effort leaving the abandoned City of Montreal burning. She to be seen as a derelict by another steamer some time later, but which subsequently disappeared, presumed sunk. The SS York City carried the survivors to Queenstown (now Cobh) in Southern Ireland, from where they were transported onward to Liverpool. The loss of life could have been far higher and passengers and crew had a very lucky escape.

The last word on the event was had by the Scots poet, William McGonagall, who could be relied on at the time to provide verses recording every major national event, but most especially disasters. He was to draw a moral from the SS City ofMontreal’s loss:

So good people I warn ye all to be advised by me,

To remember and be prepared to meet God where’er ye may be;

For death claims his victims, both on sea and shore,

Therefore be prepared for that happy land where all troubles are o’er.

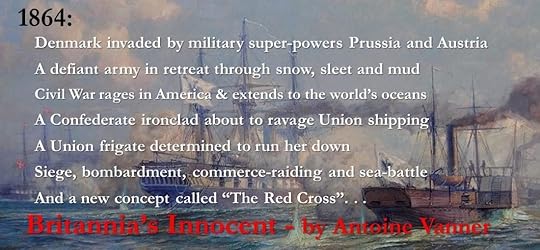

Click on the banner below for more details of: Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the seriesSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Disaster by fire: SS City of Montreal 1887 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 25, 2022

Destruction of HMS Crescent, 1808

For most officers and men, storms represented a greater threat to life than enemy action throughout the Age of Fighting Sail. The loss of HMS Crescent, off the coast of Denmark in December 1808, is an appalling example of how a well-built wooden ship could be pounded to pieces on a lee shore, without hope of survival, in the years before steam power gave greater independence of wind and weather.

A 36-gun fifth-rate frigate launched in 1781, HMS Crescent has seen significant service in European, South African and West Indian waters. Her moment of glory had come on 20th October 1793 when she had fought a classic frigate to frigate duel with the French La Réunion off Cherbourg. The two-hour battle was ferocious, both ships losing sections of masts and rigging. HMS Crescent did manage however to retain enough manoeuvrability to allow her to be placed under La Réunion’s stern so as to rake her – the most effective tactic for inflicting massive damage on an enemy. The surrendered La Réunion was taken into the Royal Navy as HMS Reunion.

HMS Crescent’s day of glory, 20th October 1793. Crescent on left, La Réunion on right. Painting by John Christain Schetky (1778-1874)

In late 1808 HMS Crescent was headed for the Baltic (click here to see recent blog on operations there in this period) under command of Captain John Temple. She left Yarmouth, on England’s east coast, on 29th November. In the following days, initially favourable weather deteriorated to a gale from the southwest. At daylight, on 5th December, the coast of Norway was sighted to the north and the Danish region of Jutland lay south. In early afternoon soundings showed water-depth decreasing from twenty-five fathoms to thirteen in the space of two hours. Given the hazards of sailing in this hazardous area, HMS Crescent was carrying experienced pilots who allegedly knew it well. These now advised that they were familiar with the soundings and that in the present conditions the ship should be hove to with her head southwards and her topsails reefed until the weather should improve. HMS Crescent could then drift with safety in adequate water depth. This advice was immediately acted upon but the sounding nevertheless decreased to ten fathoms – still safe, but only if the depth would not lessen further.

The pilots were over-optimistic. HMS Crescent did indeed drift safely until 10 p.m. – and then she grounded. A boat was lowered immediately to sound the area and it reported that the current was running eastward – towards yet shallower water, at some two and a half knots. As set, the vessel’s sails were forcing the ship further on the shoal, so orders were given to furl them and to hoist out all the boats except the jolly-boat and gig. The current was now driving on HMS Crescent’s starboard bow and in an effort to draw her off the sails were loosed again. This proved led her to be canted over on one side. There was nothing for it now but to haul the vessel off by anchor. The sails were furled again and the launch, a large boat, took an anchor and cable on board. The other ship’s boats tried to tow the launch to a preferred position for dropping but the waves and current were too much for them. The anchor seems therefore to have been dropped short.

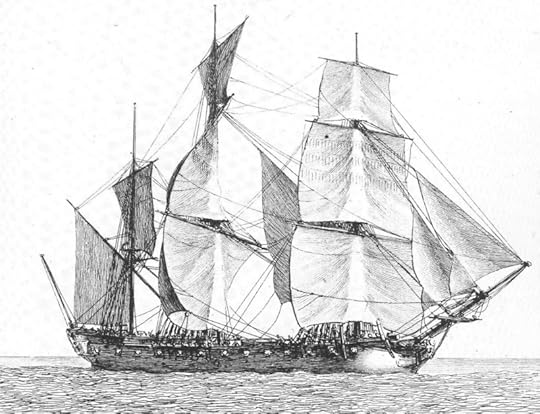

A typical frigate of the era – HMS Crescent would have looked generally similar in 1808

HMS Crescent’s situation was now desperate. The gale was yet stronger and veered round to the north-west, blowing direct onshore, forcing the vessel further on the shoal. As a last attempt to save her, Captain Temple directed that she be lightened by heaving the guns and shot overboard. As this was to no avail, the provisions followed. Badly battered, the hull was letting in water and pumping did not stop it rising to the hatches. Now the anchor cable parted and all hopes of saving the vessel were abandoned. It should be borne in mind that these desperate measures had gone on in darkness and wet cold.

At 6 a.m. on the 6th of December Captain Temple ordered the masts to be cut away. The boats which, until this time, had been lying astern on tow lines, broke their hawsers and the few men on board them found it impossible to get back to the ship due to the strong current. They made for the shore, and all succeeded reached it, with the exception of one of the cutters, which was lost with all her crew. In another boat, a Lieutenant Henry Stokes, fearing that she would be capsized, jumped overboard, and attempted to swim on shore, but was drowned in the attempt.

The storm worsened through the morning, and the men still on board the wrecked HMS Crescent were exhausted. They were nevertheless piped to breakfast and issued a tot of grog – it is amazing how, in such extreme conditions, formal procedures were still followed. Soon after noon, when it must have been obvious that the hull might soon break up entirely, construction of a raft commenced. It was ready by 2 p.m. and put under command of a Lieutenant of Marines and laden with the weakest of those still on HMS Crescent. It pushed off, but those on board found water washing over them to waist height and tearing seven of them away before the raft reached the Danish shore.

Few artists have ever conveyed the plight of a small boat in a stormy sea as well as Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

A second raft was begun on the Crescent but could not be completed. Waves were now breaking across the decks and the tiny jolly-boat was the only means of escape. It could carry only a few – and its own chances of survival would be slim, but she was launched anyway. Captain Temple was now left behind with some two hundred others. These men must have known that there was no hope for them – their state of mind must have been dreadful. Soon after the departure of the jolly-boat, HMS Crescent broke up. Including Captain Temple, not a single person still on board survived – and these included six women. and a child. Of some two hundred and eighty on board, all but sixty had perished.

The surviving officers of HMS Crescent subsequently faced court-martial for the loss of the vessel. The court’s decision was damning for the master, stating that “the loss of the Crescent proceeded from the ignorance and neglect of the pilots, and that the master was blameable, inasmuch that he did not recommend to the captain or pilots either coming to an anchor, or standing on the other tact, for the better security of H.M. late ship Crescent.” The efforts of the survivors were commended however: “The court was further of opinion that every exertion was made on the part of the remaining officers and crew for the safety of the Crescent.”

Wind, wave and current had done for HMS Crescent what enemy broadsides had not achieved fifteen years before.

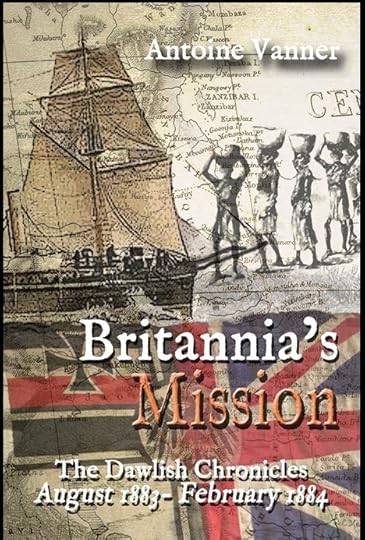

Britannia’s MissionClick image for details or to order

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and of a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Click here or on the cover image above for details or to orderThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner below for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Destruction of HMS Crescent, 1808 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 18, 2022

Trader vs. Privateer- An Unequal Duel 1744

An Unequal Duel: Trader vs. Privateer 1744

An Unequal Duel: Trader vs. Privateer 1744The story of war against maritime trade in the Age of Fighting Sail is usually told, whether in fact or in fiction, from the viewpoint of the naval commerce-raider intent on prize-money. One finds few accounts which view these contests from the side of the victims. I was therefore fascinated by stumbling recently on an account of a furious battle between a civilian trader – armed, as was essential at the time – and a French privateer in 1744, during the War of Austrian Succession.

A trading brig by Joseph Walter,1838 – the Isabella may have looked similar

A trading brig by Joseph Walter,1838 – the Isabella may have looked similar

The Wrightson and Isabella of Sunderland was a merchant ship engaged in trade across the North Sea and commanded by a Captain Richard Avery Hornsby (1699-1751). No details are available of this vessel but given the fact that she was manned by only five men and three boys, besides Hornsby, and that she mounted four carriage guns – which could only have been small ones – and two swivels, she cannot have been of large size, perhaps brig-rigged. On 13th June 1744 Hornsby arrived off the Dutch coast at Scheveningen, the coastal suburb of The Hague, in company with three smaller vessels with which he had sailed in convoy from Norfolk. The Isabella (it’s easier to refer to her as such) was laden with malt and barley. At this period there was no harbour at Scheveningen – one would not be constructed until 1904 – and trading vessels had to lie offshore and transfer cargoes ashore in smaller boats. Fishing boats were drawn up on to the beach (a subject for many painters, including Vincent van Gogh, for many years).

Fishing boats on the beach at Scheveningen, 1882 – by Vincent van Gogh

Fishing boats on the beach at Scheveningen, 1882 – by Vincent van Gogh

When the Isabella arrived, a large number of fishing boats were lying offshore and among them a French privateer, the Marquis de Brancas, had concealed herself. Commanded by a Captain André, this appears to have been a larger vessel that carried ten carriage guns and eight swivels, plus a crew of 75. She made straight for the Isabella, the other British ships turning away and escaping.

View of Scheveningen 1871 by Johannes Joseph Destree

View of Scheveningen 1871 by Johannes Joseph Destree

Note the vessels clustered offshore – among such a grouping the Brancas would have lurked

Given the disparities of armament and crew, resistance by the Isabella must have appeared suicidal. Hornsby seems however to have had the agreement of his crew to fight it out and he accordingly refused to comply when André of the Brancas called on him to strike his colours. Like any privateer André was naturally focussed on capture of a valuable prize rather than on her destruction and his initial attack on the Isabella was with small-arms fire only. Hornsby ordered his men to shelter and by skilful manoeuvring avoided two French attempts to board on the port quarter. By this stage the Brancas was bringing her guns as well as her small-arms into action and Hornsby was replying with his two port weapons.

This part of the action lasted – amazingly – for upwards of an hour but at two in the afternoon the privateer ran her bowsprit into the main shrouds on Isabella’s port side and held there. Captain André again demanded that Hornsby strike, and was one again rejected. Some twenty French now crossed only to be driven back by a hail of blunderbuss-fire. The Brancas broke free and attacked the Isabella on her starboard side. A new boarding attempt was made – this must have been a nightmare conflict, conducted as it was with hatchets and pole-axes as well as small arms. The two ships were by now lashed together and Hornsby’s men, concentrated at the Isabella’s stern, were somehow holding back the attackers, fresh men crossing from the Brancas to replace dead and wounded boarders. These attackers had taken shelter behind (or rather ahead of) the mainmast when Hornsby fired on them again with his blunderbuss. He had not realised that in the heat of the moment it had been doubly loaded and, as he fired, the weapon burst, throwing him down bruised but still defiant. Boarding proving too costly, Captain André now pulled his men back on board the Brancas and broke away, apparently determined on destruction – and revenge – rather than on capture of a prize.

Royal Navy brigantine, 18th Century – the Brancas might have looked roughly similar

Royal Navy brigantine, 18th Century – the Brancas might have looked roughly similar

As the French vessel sheered off Captain Hornsby managed to fire his starboard guns into her stern – raking her – and a new yard-arm to yard-arm gunnery battle commenced, a miniature version of the single-ship frigate actions of later decades. Isabella – not surprisingly – had the worst of it, her hull damaged, her sails and rigging torn to shreds and every mast and yard damaged to some extent. The resolve of Hornsby and his crew must have been almost superhuman but it was rewarded by landing a lucky hit on the Brancas “between wind and water” – i.e. along the waterline. This forced the French captain to draw away to plug the leak, thereby giving the Isabella enough respite to haul her fallen ensign up again.

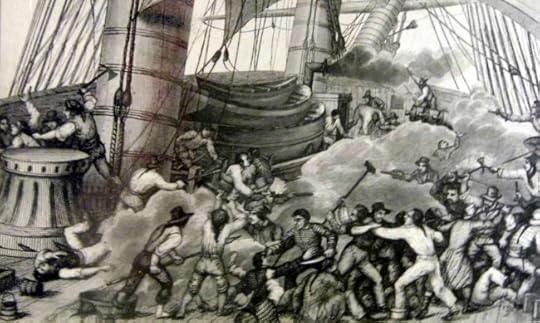

Boarding – the close-quarters horror of the Age of Fighting Sail

Boarding – the close-quarters horror of the Age of Fighting Sail

The contest was taking place close inshore and crowds had hurried to the beach on foot and by coach to view the spectacle. With her leak stopped, the Brancas now returned to deliver the crippled Isabella what must be her coup-de-grace. She crossed under the Isabella’s stern subjecting her to a volley of small-arms fire, one musket ball hitting Hornsby on the temple. He bled profusely but was not otherwise seriously wounded. Brancas now poured three broadsides into the Isabella but was again driven away by another lucky water-line strike. A hasty repair was enough to bring her back into action – another five broadsides were smashed into the Isabella’s hull and André once more called on Hornsby to strike her colours. With his demand once more rejected, he ordered his men to bring Brancas alongside to board once more and was answered with a refusal. They had had enough and there was nothing more to be done but for André to break off the fight.

A man-of-war exploding – by the Russian painter Ivan Aivazovsky

A man-of-war exploding – by the Russian painter Ivan Aivazovsky

The Brancas’s detonation would have been smaller, but no less deadly

What happened now was perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the encounter. As the Brancas drew away, Isabella fired on her for the last time. A shot passed through the French vessel’s already badly damaged stern and set off her magazine. The Brancas blew up in a spectacular explosion – so powerful in fact that only three survivors of her crew were picked up by Dutch fishing boats. Isabella herself, a floating wreck, had survived an engagement that had lasted for a seven hours. It would have been a creditable achievement for a warship but an unprecedented one for a civilian vessel.

The courage of Hornsby and his crew were deservedly recognised. Three months later, at Kensington Palace, King George II presented him with a gold medal and chain worth £100 while each of his crew members – who seem all to have survived – were awarded £5 each, though with only £2 for the boys. It is sad to note however that Hornsby lived only another seven years and died at sea “of a lingering illness”.

Hornsby and his men deserve to be remembered.

Britannia’s InnocentChronologically earliest of the Dawlish ChroniclesFor more details click the image below Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner below for more details

Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner below for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Trader vs. Privateer- An Unequal Duel 1744 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 10, 2022

War with Russia – HMS Implacable, 1808 & 1809

HMS Implacable at war with Russia – 1808 & 1809

HMS Implacable at war with Russia – 1808 & 1809Two events dominate the general impression of Russia’s role in the Napoleonic Wars. The first is the crushing defeat of Russian and Austrian forces at Austerlitz in 1805 – arguably Napoleon’s most impressive battle. The second was the French retreat from Moscow in late 1812, harried by Russian forces, a major factor in Napoleon’s downfall, culminating in the camping of Cossacks in the Champs Élysées in Paris, less than two years later. It is not so often remembered however that in part of the intervening time, 1807 to early 1812, Russia was an ally, though a not very active one, of Napoleon’s French Empire.

Napoleon at Friedland, June 1807 – by Horace Vernet (1789-1863)

The rapprochement between France and Russia followed the battle of Friedland in 1807 – another devastating defeat for the Russians. In its aftermath Napoleon met the Russian Czar, Alexander I, on a raft – neutral ground – moored on the Nieman river at Tilsit, now in Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast.

Napoleon and Alexander I meet on the raft, 25th June 1807 by Adolphe Roehn (1780-1867)

What resulted was a treaty that established peace between the French and Russian Empires but at the cost of requiring Russia to stop trading with Great Britain. This represented another link in Napoleon’s “Continental System” which aimed at establishing French-dominated Europe as a single economic entity and destroying Britain as a trading nation. Russia fell in line by declaring war on Britain in 1807, and the following year on Sweden, the only European country that refused to be part of Napoleon’s anti-British alliance. Sweden’s decision was to cost her dear, as it resulted in her loss to Russia of Finland, up to that time a Swedish possession. Russia’s Czar Alexander I generally restricted Russia’s contribution to the war to the bare requirement to close off trade. The British, understanding his position, limited their military response, most notably to naval operations in 1808 and 1809.

The threat to Britain’s trade with Finland was especially important since “Baltic Stores” – timber – were of critical importance to the Royal Navy. Britain’s response was to send a fleet to the Baltic in 1808, under command of Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez (1757-1836), to operate in concert with the Swedish Navy.

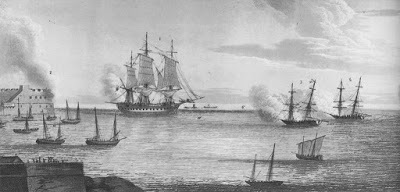

Russian ship Opyt engaged by a British frigate 11th July 1808 – many of the actions of the Anglo-Russian War were small scale. This painting is by Leonid Demyanovich Blinov(1868-1903)

On 22nd August 1808, a Russian force of nine ships of the line and eleven frigates advanced westwards along the northern shore of the Gulf of Finland to attack the Swedes. Accompanying the latter were two British “74s” ships-of-the-line, HMS Centaur and HMS Implacable. Russian resolve now faltered and a retreat ensured, the two British vessels outpacing their Swedish allies and catching up with a Russian straggler, the “74” Vsevolod on 24th August. Three other Russian ships in the vicinity offered no assistance as HMS Implacable subjected the Vsevolod to heavy fire and drove her aground. The Vsevolod “struck” – ran down her colours in surrender – but the main Russian force had by now turned back to come to her rescue. Outnumbered, HMS Implacable retreated and the Vsevolod was once more in Russian hands.

A Russian frigate, the Poluks, then towed the damaged Vsevolod towards Rågervik (now Paldiski, in Estonia, on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland), where the main Russian force was now heading for refuge. Some six miles outside the port, the Vsevolod ran aground again. HMS Centaur had continued to follow however and, on 25th August closed, chasing away the boats that were attempting to get the Vsevolod afloat again. HMS Centaur drove on and indeed grounded herself. Her crew managed to lash her mizzen mast to the Russian’s bowsprit to draw both ships together before opening fire. Attempts to board were made by both crews but the issue was decided when HMS Implacable arrived and, standing off, fired on the Vsevolod for some ten minutes. The Russian colours were once more run down and some of her crew jumped overboard and managed to reach land.

The burning of the Vsevolod (referred to here as Sewolod)

HMS Implacable succeeded in towing HMS Centaur off. The battle had cost the Centaur three killed and 27 wounded. The Vsevolod was however so firmly grounded that there was no hoping of getting her free also and the decision was taken to burn her after taking off the Russian crew. The decision must have been very bitter since the capture of an enemy ‘74’ would have resulted in substantial prize-money for all involved. The Vsevolod blew up a few hours afterwards. (We encountered HMS Centaur before, at Diamond Rock. Click here to read the blog about her then).

An equally daring operation occurred early in July the following year, again involving HMS Implacable, with support from the ‘74s’ HMS Bellerophon and the frigates, HMS Melpomene, and HMS Prometheus. On 6th July 1809 HMS Implacable had captured several merchant vessels in the Gulf of Narva (north of Estonia) but the Russian escort, an armed ship and some gunboat managed to escape. They took up a strong defensive position close inshore, where the larger British vessels could not follow. What ensued was a raid of the type in which the Royal Navy excelled – sending in ships’ boats for boarding and depending heavily on surprise and aggression for success.

Command was entrusted to a young Lieutenant Hawkey, and the boats of the other vessels, laden with seamen and marines, assembled around HMS Implacable and headed inshore in darkness. The report of Implacable’s Captain Thomas Byam Martin(1773 – 1854), later Admiral of the Fleet, deserves to be quoted, stating that the boats advanced with “an irresistible zeal and intrepidity towards the enemy (who had the advantage of local knowledge), to attack a position of extraordinary strength, within two rocks, serving as a cover to their wings, whence they could pour a destructive fire of grape on our boats, which notwithstanding advanced with perfect coolness and never fired a gun till actually touching the enemy, whom they boarded sword in hand, and carried all before them.” Lieutenant Hawkey was killed by grape-shot as he boarded a Russian gunboat, allegedly shouting at the moment that he was struck: “Huzza, push on, England for ever!”

Boarding was always a desperate undertaking (With thanks to the Napoleonic Guide for this illustration – www.napoleonguide.com)

The outcome was impressive and Captain Martin wrote that “I believe a more brilliant achievement does not grace the records of our naval history: of eight gunboats, each mounting a 32 and 24-pounder, and carrying 46 men, six have been brought out, together with the whole of the ships and vessels, twelve in number, under their protection — laden with powder and shot for the Russian army — a large armed ship taken and burnt, and one gunboat sunk.”

Those familiar with memorials in English parish churches to officers lost in the Napoleonic wars will not be surprised by the elegance of the language with which Captain Martin reported Lieutenant Hawkey’s death: “No praise from my pen can do adequate justice to this lamented young man. As an officer he was active, correct, and zealous to the highest degree; the leader in every kind of enterprise, and regardless of danger, he delighted in whatever could tend to promote the glory of his country.”

The butcher’s bill for this operation was not negligible: seventeen British killed and thirty-seven wounded. Large numbers of Russians were drowned in addition to sixty-three found killed and fifty-one wounded out of a hundred and twenty-seven prisoners.

And now, two centuries on, and with the benefit of full hindsight, one realises how futile all this was. Three years later these men would have been allies in the fight against Napoleon. But they never lived to know it.

Click on the banner below for more details Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the seriesSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post War with Russia – HMS Implacable, 1808 & 1809 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 3, 2022

van Speijk’s sacrifice – Antwerp, 1831

“I’d prefer to be blown up!” – van Speijk at Antwerp, 1831

“I’d prefer to be blown up!” – van Speijk at Antwerp, 1831The revolt that led to the creation of modern Belgium as an independent state was the background to an act of insane heroism by a young Dutch naval officer, Jan van Speijk, whose (alleged) last words were to become an expression still in use today. This is his story.

The Netherlands and Belgium are today two separate nations, and have indeed had separate existences, in one form or another, for most of the time since the late sixteenth century. Up until 1806, the Netherlands had a complex republican form of government, though allowing however a hereditary role to Princes of the House of Orange. The nation fell under French control in 1795 and in 1806 it became the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the Emperor Napoleon’s younger brother Louis installed as King. What is today Belgium (allowing for frontier adjustments) was ruled as a province of the Hapsburg Empire from the seventeenth century until the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars.

King William I’s son leading Dutch-Belgian forces during the Waterloo campaign

As Napoleon’s power waned, and as he was sent in exile to Elba, the Great Powers of Europe supported creation of a single unified state, combining both regions, and henceforth to be known as “The Kingdom of the Netherlands.” Its sovereign was to be the current Prince of Orange, who took the title of King William I and who was also made ruler, under the title of Grand Duke, of the separate state of Luxembourg. The new Kingdom was functioning when Napoleon came back from Elba during “The 100 days” in 1815, and Dutch-Belgian forces were to fight against him at Waterloo.

Belgian rebels in Brussels 1830

For the next 15 years the northern, Dutch, and the southern, Belgian, parts of the kingdom lived uneasily together. Though adherents of both religions lived in all areas, the north was predominantly Protestant and the south predominantly Catholic. The situation was further complicated by the southern provinces containing both French-speaking Walloon and Dutch-speaking Flemish communities. Tensions increased and in the south resentment grew against what was seen as the Protestant hegemony by the House of Orange and its adherents. This discontent exploded in outright rebellion in Belgium in 1830. King William attempted to restore order but was hampered by mass desertion of troops hailing from the southern provinces. Unable to restore order, despite bloody street-fighting in Brussels and elsewhere, William withdrew his forces, though he maintained a blockade of Antwerp, and appealed to the Great Powers to resolve the problem. This resulted in the London Conference of European powers which recognised Belgium as an independent country. Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg was installed as “King of the Belgians”.

Dutch cavalry under attack in a Belgian town

Unhappy with this outcome, King William of the now truncated Netherlands – essentially the territory it consists of today – was to oppose the separation, culminating in an unsuccessful invasion of Belgium known as De Tiendagse Veldtocht (“The Ten Days’ Campaign”) which lasted from the 2nd to the 12th of August 1831. Despite initial successes, French intervention forced the Dutch to agree to an indefinite armistice. Faced with such opposition, William had no option but to withdraw, humiliated and smarting, but it was not until 1839 the Netherlands accepted Belgian independence by signing the Treaty of London. As one of its signatories, it was in line with the terms of this treaty that Great Britain entered World War I when Belgium was invaded by Germany in 1914.

van Speijk’s romanticised youth

– admiring tomb of de Ruyter

Probably only one incident from this complex series of events is widely remembered in the Netherlands today. This was the exploit of the young Dutch naval lieutenant, Jan van Speijk (pronounced like “Spike” in English), who achieved immortality at Antwerp in February 1831. Dutch naval forces were maintaining a blockade of this important port – then as now, one of the largest in Europe, as it functioned as a commercial gateway to Germany. Van Speijk was in command of a small gunboat, one of many engaged in blockade duty, a more difficult task then than nowadays as many mouths of the Scheldt Delta, at the head of which Antwerp lies, were then open but which have since been closed off by dams.

Van Speijk’s background seems almost too good to be true for a popular hero. Born in Amsterdam in 1802, his parents died when he was a baby and he was brought up in an orphanage and subsequently trained as a tailor. Such a mundane career did not attract him and he instead joined the Royal Netherlands Navy in 1820. Thereafter he was to serve with distinction in the Dutch East Indies in the Boni Campaign of 1825 in the South Celebes. By 1830 he was a lieutenant – a very impressive achievement for a man who had started with such poor prospects. As the revolt in Belgium grew he was in command of Kanonneerboot Nummer 2 (Gunboat Number 2), a small sailing craft armed with a single cannon. On October 27th van Speijk performed so effectively in a bombardment of Antwerp that he was awarded a decoration.

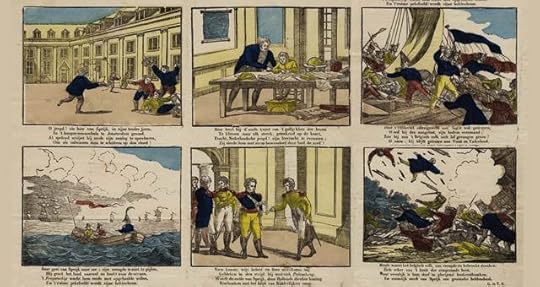

19th Century comic strip about va n Speijk’s li fe

The blockade continued through the winter and during this time van Speijk seems to have thought deeply – might have indeed been obsessed – about what he should do if his vessel were to fall into Belgian hands. In December 1830 he wrote to his niece that he would rather blow up his craft rather than surrender it, and he referred to an incident in 1606 when a Dutch captain had done just this to prevent seizure by the Spaniards. During new-year celebrations he told his crew the same and was allegedly applauded by them, though it is uncertain whether they thought that he was wholly serious.

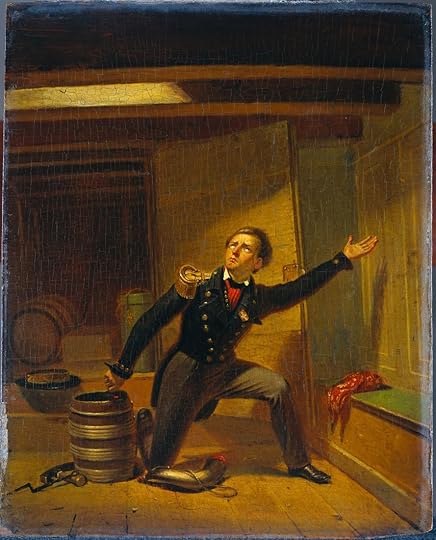

What van Speijk feared could happen, does happen- the mob storms the gunboat,

the ship’s boy knows what’s coming and jumps overboard. van Speijk himself goes below

The crunch came on February 5th 1831. Caught in a north-west gale, and with a dragging anchor, van Speijk’s gunboat was thrown up on the shore. A Belgian mob surged on board. What followed was the stuff of legend, the more so since few survived to tell a coherent story. Unable to prevent the vessel’s capture, van Speijk went below and with the reported words of “Ik ga liever de lucht in” (“I’d prefer to be blown up” – more literally: I’d prefer to go up into the air” ) he either fired his pistol or dropped his cigar into a barrel of gunpowder.

“Ik ga liever de lucht in!” and van Speijk shoots into the keg of gunpowder

The resulting explosion wrecked the gunboat and killed van Speijk himself and 27 of his crew of 30 as well as an unknown number of Belgians. Since there were only two survivors, one of whom was boy who, seeing what was intended, had jumped overboard before the explosion, it is not quite sure how van Speijk’s final words were recorded, or indeed if he ever spoke them.

The destruction of Gunboat Number 2, Antwerp in the background

The latest van Speijk

Van Speijk was immediately hailed as a national hero in the Netherlands, the admiration being led by King William himself, who within a week of his death issued an order that there should always be a ship called van Speijk in the Royal Netherlands Navy. This order has been honoured ever since and the current van Speijk, the eighth, is a Karel Doorman-class frigate launched in 1995. Van Speijk’s remains were buried with pomp in Amsterdam with the King present and his life was thereafter the subject of poems, paintings and even inspirational nineteenth-century versions of comic strips.

And the expression “Ik ga liever de lucht in!” entered the Dutch language and even today is used as a term of exasperated refusal.

Do you enjoy naval fiction?If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read any of the ten (s0 far!) Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post van Speijk’s sacrifice – Antwerp, 1831 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 27, 2022

Franz Josef Land Discovery 1873

The Discovery of Franz Josef Land 1873

The Discovery of Franz Josef Land 1873

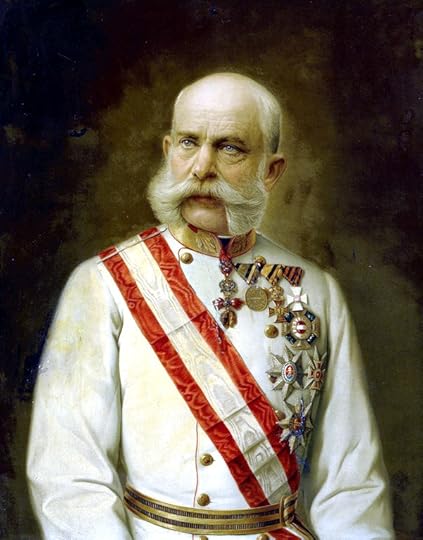

Franz Josef in 1910 – an old man

because of whom so many young men died

Emperor Franz Josef (1830 – 1916) of the Austro-Hungarian Empire reigned for an amazing 68 years and is probably best remembered today for his complicity in starting World War 1. Conscientious, unimaginative, hardworking, pig-headed, but essentially stupid, his tenure was to be marked by military defeat, political decline and personal tragedy. His wife was murdered, his son died in a suicide pact, his brother – the so-called Emperor of Mexico – was shot by a firing squad and his nephew’s assassination triggered disaster in 1914. His domains lay in Central and Southern Europe and it is therefore all the more surprising that the archipelago named after him – Franz Josef Land – should be located in the Arctic Ocean and be today a Russian possession of considerable strategic value. Another article (Click here to read it) on this site describes Austro-Hungary’s Novara scientific expedition of 1857-59. In this period, such expeditions were matters of international prestige comparable to space exploration in our own day and Austria (and later Austro-Hungary), which had only acquired a navy in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, was keen not to be left out.

The resulting Novara expedition was to be a triumph that included oceanographic and geomagnetic surveys as well as investigation of the onshore botany and geology of lands visited. It provided material for what would become Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum in such volume that some of it is still under examination today. My wife and I spent two full days in the museum in September 2016 and we could have spent an entire week there, with no less pleasure. We were impressed by two splendid models of ships that had participated in important scientific expeditions. The first was the previously mentioned Novara, but the second was of the later Tegetthoff, which was responsible for the discovery of Franz Josef Land.

The Novara model in Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum

The Novara model in Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum

By the 1870s the Arctic had become a major focus of exploration activity. It was not surprising therefore that when a major Austro-Hungarian scientific and exploration effort was launched in the early 1870s the focus was to be on the Arctic Ocean and investigation of a possible route to the North Pole. Financed by two noblemen, the exploration was to concentrate on the area north-west of Novaya Zemlya. It was under command of Captain Karl Weyprecht, who had himself served under the famous Admiral Tegetthoff, for whom the vessel was named. The crew was small – 24 in number, including scientific staff.

The Tegetthoff model in Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum

The Tegetthoff model in Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum

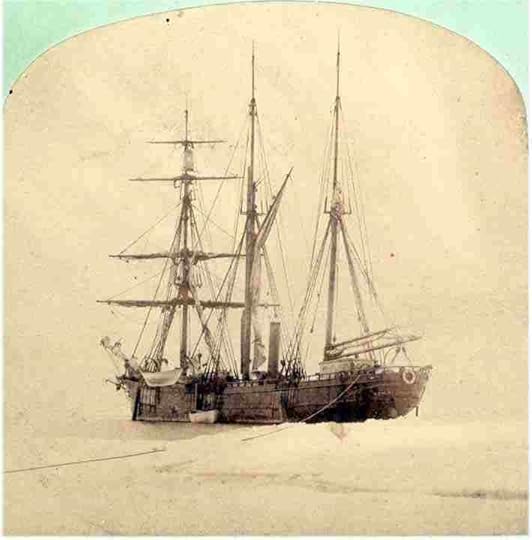

The Tegetthoff departed from Tromsø, in Norway, in July 1872. A month later she found herself locked in pack ice north of Novaya Zemlya. The phenomenon of ice-drift in the Arctic ocean was not yet known much less understood, and the ship was in the same nightmare situation as the American Jeanette expedition of 1878-81 (Click here to read a separate article on this).

Forecastle details

Forecastle details

Deck details

Deck details

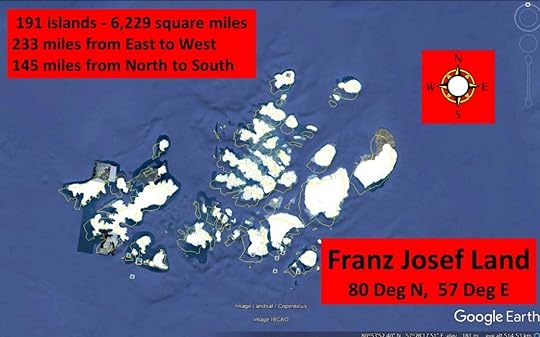

Though there was continued expectation that the ice would ultimately release its hold and give access to open water, the Tegetthoff was now drifting into the unknown. The ship was to remain locked during the winter of 1872-73, through the summer that followed, and through another winter, 1873-74. Hope, discipline and morale remained high however and when an obvious land mass was sighted a sledge expedition was despatched, under one of the expedition leaders, Julius von Payer, to investigate. The land discovered proved to be an archipelago, now known to consist of 191 islands, one of the most barren places on earth, and then wholly uninhabited. It was duly named after Emperor Franz Josef.

In our own day, accustomed as we are to instant global communication, it is difficult to imagine just how desperate was the plight in the past of any vessel held in the ice, with no definite prospect of being released, and no means of contacting the outside world to call for help. It is therefore all the more credit to the Tegetthoff expedition that, even in these potentially lethal circumstances, scientific work proceeded calmly and systematically.

Tegetthoff locked in the ice

Tegetthoff locked in the ice

Location of Franz Josef Land – with thanks to Google Earth

Location of Franz Josef Land – with thanks to Google Earth

It seems to have emerged later that this may not however have been the first sighting of the Franz Josef archipelago, since a Norwegian sealing vessel may have done so in 1865. Anxious however to keep secret what could be a fertile area for sealing and whaling, and to ensure that other vessels would not come to exploit it, no announcement was made by the captain responsible. The Tegetthoff Expedition’s objective was however less mercenary and the credit for the discovery is therefore due to it. One cannot be impressed by the cool-efficiency with which sledging parties were sent out throughout 1873, even though the prospects for the release of the ship from the ice became more grim by the day. On one of these sledge journeys, von Payer reached 81° 50′ North, the highest latitude achieved up to that time.

The Franz Josef archipelago – with thanks to Google Earth

The Franz Josef archipelago – with thanks to Google Earth

When spring arrived in May 1874 the expectation that the ice might free the ship was proved vain. The decision was accordingly taken to abandon the Tegetthoff and to strike out for the open sea, dragging the ship’s boats. The journey involved must have been a nightmare and it lasted almost three months, but on 14 August 1874 open water was reached. The boats carried the crew to Novaya Zemlya, from where a Russian fishing boat carried them to Northern Norway. Weyprecht, von Payer and their men were accorded a well-deserved hero’s welcome at each stage of their return to Austria through Norway, Sweden and Germany. Their entry to Vienna was greeted by a crowd numbered at over a hundred thousand. For all that the Tegettoff herself had been lost, her scientific contribution had been enormous.

The empire that Franz Josef had ruled lasted only two years after his death and is now a distant memory. It is ironic therefore that in the wastes of the Arctic, where he himself never set foot, his name should be preserved.

Do you enjoy naval fiction?If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read any of the ten (s0 far) Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Franz Josef Land Discovery 1873 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 21, 2022

Forging a partnership- Nelson and Hardy

Nelson and Hardy – forging a partnership

Nelson and Hardy – forging a partnershipWe have encountered HMS Blanche before, in her furious duel in January 1795, in the middle years of the Revolutionary War between Britain and France. In the process she captured the French frigate Pique, off Guadeloupe (Click here to read this earlier blog). Blanche, a 32-gun frigate, had still four years of life ahead of her before she was wrecked in 1799 and these involved considerable drama, in which two of the best known naval heroes of the era, Nelson and Hardy were to play a role.

End of the Blanche (L) vs. Pique action – both ships in states not unusual after such combats – Painting by John Thomas Baines with Acknowledgement to National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Blanche’s captain, Robert Faulknor, had been killed in the Pique action and was succeeded by Captain Charles Sawyer, who took her to Portsmouth for a refit and thereafter to the Mediterranean at the end of 1795. This theatre was to prove a difficult one for the Royal Navy in the following year, but for Sawyer personally it was to prove a personal disaster.

The Articles of War, under which Royal Navy ships operated, were merciless as regards punishment of homosexual acts, with the death penalty itself reserved for sodomy. The offence would have been regarded as even more serious if it involved a commissioned officer. It appears that Captain Sawyer had gained a reputation among his crew for such behaviour – accusations were made as regards relations with two young midshipmen, his coxswain and an ordinary seaman. The offence was compounded by the fact that the captain of a ship at sea represented absolute authority and that there was an assumption that this would be exercised fairly and conscientiously. A captain was to be respected, as well as on-occasion feared, and in Sawyer’s case this respect was wholly forfeited as his behaviour was common knowledge on board. Discipline deteriorated to the extent that Blanche’s first lieutenant, Archibald Cowan, wrote about it to the area commodore, Horatio Nelson. This step took considerable moral courage. To criticise a superior in this way was dangerous in the extreme as it could be construed as insubordination and lead to the quick ending of a career.

Nelson in 1796

In the event, the matter was handled with considerable pragmatism and adroitness, and indeed with humanity also. A charge of sodomy against a commissioned officer, which would involve embarrassing evidence that would be most likely challenged and debated, would have done nothing for the prestige of the service and might have had a terrible, possibly mortal, outcome for Sawyer personally. The charge brought against him in the unavoidable court-martial was related instead to the breakdown of discipline, specifying “odious misconduct, and for not taking public notice of mutinous expressions muttered against him“. Sawyer was found guilty in October 1796 and dismissed from the service.

Even before the court-martial was convened a new commander was required for the Blanche. This was to be Captain D’Arcy Preston, who was faced with the challenge of restoring discipline and respect for the chain of command. That he was successful in this was to be shown a few months later, in December 1796, when Blanche once more found herself in action.

During the year Britain’s position in the Mediterranean had weakened considerably in the face of French successes in Italy and Corsica. The Mediterranean Fleet commander, Sir John Jervis, took the unwelcome but realistic decision in October 1796 to withdraw to Gibraltar after evacuating British forces from Corsica and Elba. Nelson was to take charge of the latter operation and to initiate it he sailed from Gibraltar in December with two frigates, HMS Minerve and HMS Blanche. The Minerve had previously been French, having been captured in June 1795 by the frigates HMS Dido and Lowestoffe. Nelson was on board Minerve and her second lieutenant was Thomas Masterman Hardy (1769-1839), who was to play a very significant role in Nelson’s life – and death – such that the names of Nelson and Hardy are often linked in the public mind.

Capture of Minerve 1795 – Thomas Sutherland (engraver), Thoams Whitcombe (artist)

On 10th December, two Spanish frigates were spotted in the vicinity of Cartagena. These proved to be the Sabina and Matilde, each of 40 guns, fair matches for the British ships. The Sabina was the flagship of Commodore Don Jacobo Stuart, a descendent in the illegitimate line of James II of England.

Minerve engaged the Sabina while Blanche concentrated on holding off the Matilde. After three-hour combat, during which she lost her mainmast, and had her fore and mizzen badly damaged, the Sabrina surrendered. The Minerve had also been damaged, but her masts still stood. One has the impression, as so often in the case of frigate to frigate actions, of the British gunnery being markedly superior.

The Sabrina was then boarded by a 40-man prize crew headed by Minerve’s first and second lieutenants John Culverhouse and Thomas Hardy but her damage was such as to necessitate her being towed by the Minerve. At this point, the second Spanish ship, the Matilde, re-entered the fray and attacked the Minerve. She was driven off but a new Spanish force now appeared, the 112-gun ship-of-the-line Príncipe de Asturias and two frigates. Nelson realised that there was no hope of fighting this larger force, especially not if the Minerve had the Sabrina in tow. He took the unpalatable decision of cutting the tow and abandoning the Sabrina and her prize crew to the advancing Spanish.

Lieutenants Culverhouse and Hardy were to be prisoners of war for little over a month. Nelson was eager to have them back and he sent a message through to the Spanish authorities at Cartagena that he was prepared to exchange them for Don Jacobo Stuart. A pleasing statement in the letter was that “I have endeavoured to make the captivity of Don Jacobo Stuart, her brave Commander, as light as possible; and I trust to the generosity of your nation for its being reciprocal for the British officers and men.” The exchange was duly arranged and the two lieutenants arrived in Gibraltar at the end of January 1797.

Both men re-joined Minerve but on 11th February, shortly after leaving Gibraltar to join Sir John Jervis’s fleet, she was pursued by Spanish vessels. In the course of the chase, a seaman fell overboard and Hardy was dropped with a jolly-boat to rescue him. The unfortunate man could not be found and strong currents swept Hardy’s craft far from the Minerve so that his re-capture by the Spanish now became a distinct possibility. Despite the danger of engagement with a superior force, Nelson exclaimed “By God, I’ll not lose Hardy! Back that mizzen topsail!” so that the Minerve could drift down on Hardy’s boat and pick him up. The manoeuvre succeeded and once sail was again made Minerve’s superior speed drew her away from danger.

Battle of Saint Vincent by Richard Bridges Beechey, 1881

During the night that followed Minerve found herself in fog and sailing between dark shapes. These were those of the Spanish fleet but ineffective lookouts did not detect her. By morning she was clear and on her way to Jervis with news of the enemy fleet’s location. The scene was now set for Jervis’s victory over the Spanish at Cape St. Vincent two days later.

Jervis’s exchanges with Captains Robert Calder and Benjamin Hallowell on the quarterdeck of his flagship, HMS Victory, when it was discovered that his force was outnumbered almost two-to-one, were recorded:

“There are eight sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty-five sail of the line, Sir John”

“Very well, sir”

“There are twenty-seven sail of the line, Sir John”

“Enough, sir, no more of that; the die is cast, and if there are fifty sail I will go through them”

It was on HMS Victory that Nelson himself was to die eight years later. His admiration of Hardy had grown in this time. At the Battle of the Nile in 1798 Hardy commanded the corvette Mutine and when Nelson sent his flag captain back with news of the triumph he promoted Hardy to command of his flagship HMS Vanguard. When Nelson shifted his flag to HMS Foudroyant he took Hardy with him.

In 1801 Hardy was again to be Nelson’s flag captain and he distinguished himself at Copenhagen by surveying the route whereby the British fleet would enter the Danish anchorage. The relationship continued and in the period leading up to Trafalgar Hardy was not only flag captain on Nelson’s HMS Victory, but de-facto captain of the fleet. It was a meteoric but well-merited rise.

The death of Nelson in the cockpit of HMS Victory – the iconic image: Hardy takes his leave

Hardy as Admiral

Given the warmth and respect between these two men, it was appropriate that Hardy should be with Nelson when he was shot down at Trafalgar in 1805. As Nelson lay dying in Victory’s cockpit Hardy brought him news of the succession of French surrenders and when they came to part Nelson’s request was “Kiss me, Hardy”, which he did on the cheek. Nelson was by this time fading and Hardy kissed him a second time, this time on the forehead. The dying man asked “Who is that?” and, when told who it was, said “God bless you Hardy” – his last words.

The young lieutenant whom Nelson had once been forced to abandon, and whom he had once risked everything to save on another occasion, had come a long way in nine years. A long, varied and honourable career awaited him after Trafalgar, culminating in his appointment as First Naval Lord, the professional head of the navy, in November 1830.

The (re)capture of HMS Minerve, aground off Cherbourg, July 1803

The (re)capture of HMS Minerve, aground off Cherbourg, July 1803

One other player in this drama was also to have a dramatic further career. HMS Minerve, which had been captured from the French in 1795 was recaptured by them when she ran aground in a fog off Cherbourg in 1803. She was recommissioned in the French Navy as the Canonnière and saw active service in the Philippines, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. By 1809 she was considered worn out and was sold at Mauritius for merchant service, now renamed as the Confiance. She was captured by the Royal Navy in 1810 – as she was carrying goods worth £150,000 she was an exceptionally valuable prize and must have made the fortune of many of the crew of HMS Valiant, the ship that took her. Commissioned once more into the Royal Navy, this time as HMS Confiance, she saw little further service and was disposed of in 1814.

Do you enjoy naval fiction?If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read any of the ten (s0 far!) Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Forging a partnership- Nelson and Hardy appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 13, 2022

Fight against the Riff Pirates 1848-51

The Royal Navy vs. the Riff Pirates 1848-51

The Royal Navy vs. the Riff Pirates 1848-51The Barbary pirates of North Africa were a scourge to maritime trade for many centuries. It was only in the nineteenth century that major naval and military campaigns – most notably the US Navy’s and Marine Corps’ intervention on “the Shores of Tripoli”, the Anglo-Dutch action against Algiers in 1816 and the French conquest of Algeria in the 1830s – largely put an end to the menace. The qualification “largely” is however important as piracy did continue, albeit on a more spasmodic basis and limited scale than previously.

The Anglo-Dutch attack on Algiers, 1816, under command of Lord Exmouth (Edward Pellew), as painted by Thomas Luny (1759-1837)

Morocco was still independent through most of the nineteenth century and pirates still operated off its Northern Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts – known as the Riff area – in much the same way that Somali pirates have done in our own time. The proximity to important shipping routes passing through the confines of the Straits of Gibraltar or down the African coast ensured potentially rich pickings. Two examples, from as late as 1848 and 1851, and involving the Royal Navy, illustrate the risks to small merchant ships operating in the area. These will be detailed later in this article.

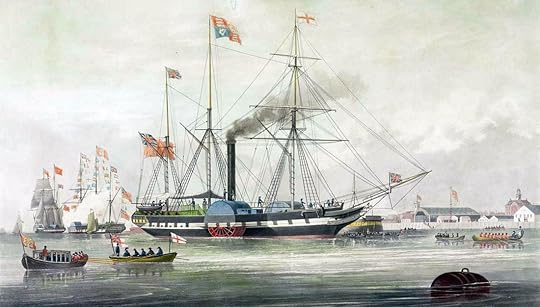

In both these cases, action was undertaken by paddle sloops, a new type of ship, of which 49 were built for the Royal Navy between 1830 and 1851. Though made up of individual classes, these vessels were generally similar as regards tonnage and length – typically less than 1000-tons and of approximately 180-feet long. They carried both sail and steam, the latter power in the form of a reciprocating engine of around 400-horsepower and driving paddlewheels.

Paddle sloop HMS Trident carrying Queen Victoria on a visit to Woolwich Dockyard in 1842. Note size and vulnerability of paddlewheels. (Drawing by William John Huggins)

Though not intended for ship-to-ship combat, since their paddlewheels provided large and vulnerable targets, they carried a powerful armament for their size, typically four 32-pounder or 8-inch smoothbores. With this gun power, and with a crew of 130, of whom a major proportion could be sent ashore as “bluejackets” to constitute small naval brigades, they were ideally suited for action against shore targets or poorly armed adversaries. They saw an amazing range of action – one was to be the first steamer to circumnavigate the globe while others saw action in the Black Sea, North Pacific, Baltic against the Russians in the Crimean War and against the Chinese in the Arrow War and others still did valuable survey duty. This surveying, which produced the maritime charts which, in updated form, are still in use today, was one of the greatest – and often forgotten and underestimated – achievements of the nineteenth-century Royal Navy.

“A trading brig drifting into a Continental harbour” by Charles John De Lacy (1856-1929) – the unfortunate Three Sisters would have looked generally similar.

In 1848 a British trading brig, the Three Sisters, was seized by pirates off the Riff coast. Her master and crew managed to escape but the vessel herself was towed close-in to the shore. The duty of retaking her was entrusted to a Commander McCleverty, captain of the paddle sloop Polyphemus. On moving in, he found a force of 500 pirates and tribesmen drawn up on the shore to defend their prize. As Polyphemus neared she was subjected to a hail of musketry. She responded with grapeshot and canister – the ideal method of attack on masses of men – and drove them back. Boats were now sent in under the command of a Lieutenant Allen Gardner to board the Three Sisters and take her out to sea. The pirates and their confederates had now regrouped and opened fire from the cover of rocks, wounding an officer and seven seamen as the oar-propelled boats towed the brig to the Polyphemus. It was a classic example of a small but effective anti-piracy action

Three years later, in 1851, a more serious act of piracy resulted in several deaths and the enslavement of the remainder of the crews, when the brigantine Violet and the schooner Amelia were captured off the Riff coast. When news of this was received at Gibraltar, another paddle slop, HMS Janus, commanded by a Captain Powell, was sent to retaliate. Both of the hijacked vessels were found wrecked on the shore but the Janus destroyed a number of pirate craft in the vicinity with gunfire. Others were drawn up on the shore and boats were sent in to destroy them. Large numbers of pirates and tribesmen had gathered however and they launched an attack so furious that the landing party had to retreat to the Janus, with Captain Powell himself and of his crew being wounded. The only bright spot was the liberation of the Violet’s crew. It would be interesting – and probably horrifying – to know what became of their counterparts from the Amelia.

These cases were typical of dozens of small and often bloody actions undertaken by the Royal Navy in this period. Forgotten today, they demanded initiative, courage and supreme professionalism, creating in the process a cadre of officers and seamen second to none.

HMS Acheron – a typical paddelsloop of the 1840s and 1850s

HMS Acheron – a typical paddelsloop of the 1840s and 1850s

And the paddle sloops? Their day was done by 1860, by which time the screw propeller, with the advantage of being hidden below the waterline, and thus less vulnerable to gunfire, reigned supreme. In their time they had rendered valuable service and deserve to be remembered with respect.

Britannia’s MissionIn which the new Imperial German Navy plays a significant role . . .Click image to read first chapters

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and of a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Click Below for details or to orderFor US and Canada For UK &Ireland For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles– now up to ten volumes and counting …Below are the ten Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones.” Click on the banner for more information about all of them. They’re available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited Subscribers.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Fight against the Riff Pirates 1848-51 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 7, 2022

Royal Navy Exhibition 1891

The Royal Navy Exhibition of 1891

The Royal Navy Exhibition of 1891The Royal Navy was to attain enormous popularity in Britain in the 19th Century, especially in its last decades. It was seen to be at the cutting edge of the technology of the time and to be the guarantor of imperial greatness against the machinations of the French, Russians and any other potential enemies, real or imagined. The main fleets in the Channel and the Mediterranean represented the most majestic concentrations of power afloat, dozens of cruisers and gunboats protected British commerce and interests in every part of the globe, and the navy was pre-eminent in charting the world’s oceans and coastlines and in creating the science of oceanography.

The Navy’s popularity was seized on for use by commercial interests. When HMS Swallow was quarantined outside Montevideo in 1889, due to a yellow-fever outbreak, her captain was alleged to have sent to shore for three boxes of Beecham’s Pills (“worth a guinea a box“). This advertisement commemorates this by flag semaphore!

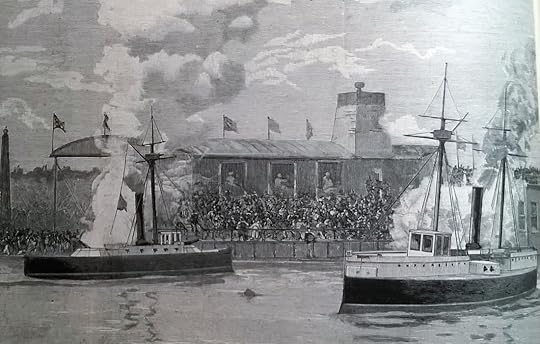

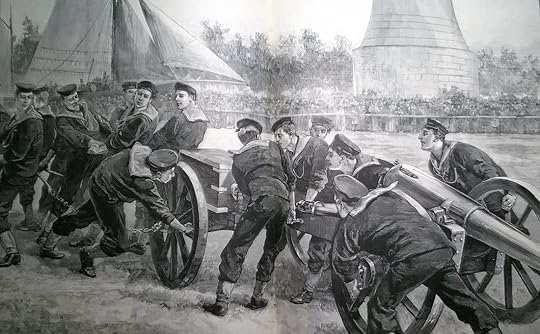

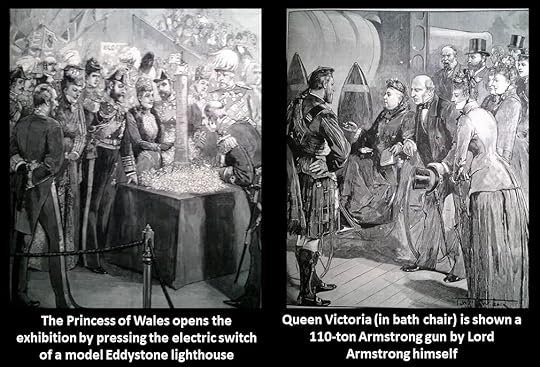

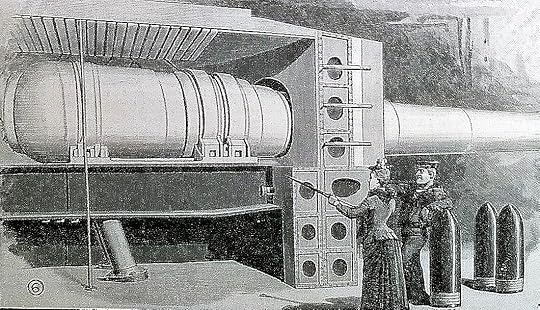

Pride in the navy crossed class boundaries and it was to cater for this that a spectacular exhibition was staged at the Royal Hospital grounds at Chelsea in 1891. Lasting some five months, the exhibition displayed paintings, models and memorabilia lent by private owners, as well as stands at which many of the main armament suppliers and shipbuilders displayed their wares. (See cover of the exhibition catalogue on the left)

Pride in the navy crossed class boundaries and it was to cater for this that a spectacular exhibition was staged at the Royal Hospital grounds at Chelsea in 1891. Lasting some five months, the exhibition displayed paintings, models and memorabilia lent by private owners, as well as stands at which many of the main armament suppliers and shipbuilders displayed their wares. (See cover of the exhibition catalogue on the left)

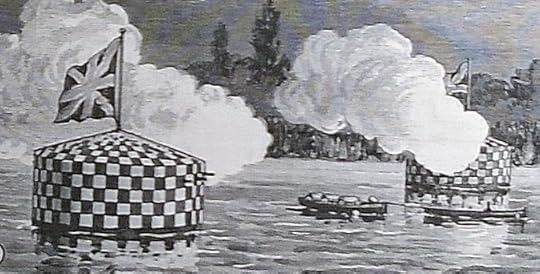

A large lake was constructed on which 25-ft models of the ironclads HMS Edinburgh and HMS Majestic blasted each other daily while smaller craft ran the gauntlet between two sea-forts, not unlike those in the approaches to Portsmouth harbour. These displays were immensely popular for their sound and fury.

Small craft run the gauntlet between two sea-forts

HMS Majestic versus HMS Edinburgh