Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 13

August 10, 2021

Admiral Walter Cowan – Fire-eating naval officer and the oldest Commando

I met Tim Chant at a Historical Novels Society in Scotland in 2018 and I was interested to learn that he was working on a novel set in the Russo-Japanee War of 1904-05. I found his projects of particular interest in view of my own fascination with this conflict. Tim’s novel is now coming available (see purchase link at the end of the article). To celebrate this, I invited him to write a guest blog – his choice of subject – and he has provided an article on one of the most fascinating and outlandish careers in the Royal Navy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Best Wishes: Antoine Vanner===============================================================

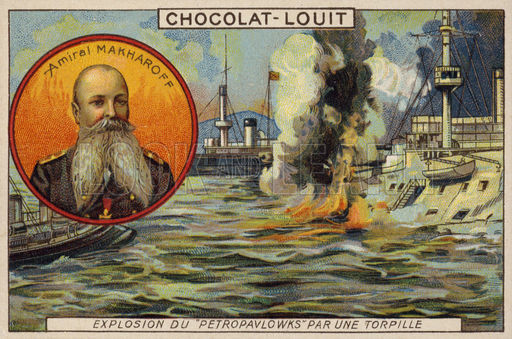

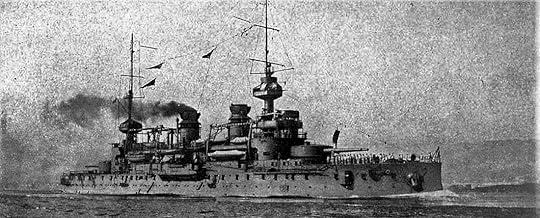

Admiral Walter Cowan – Fire-eating naval officer and oldest Commandoby Tim ChantMuch has been written, unsurprisingly, about the transition from the Age of Fighting Sail to that of Fighting Steam. Those simple phrases belie what was a staggering pace of change in naval technology and tactics, not just propulsion. While the advent of steam propulsion and then metal construction took a while to take off, from the launch of Gloire in 1859 naval warfare was subject to continual change. The half-century from the advent of ironclads saw the introduction of the torpedo, fully-effective shell artillery, all-metal construction and, latterly, the all-big-gun battleship designs, submarines and the birth of aviation. It’s fascinating that the first successful torpedo attack in history involved a young Stepan Osipovich Makarov in 1877; Makarov died in action during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/5 some months before a young Yamamoto Isoruku was almost invalided out of the Imperial Japanese Navy due to injuries sustained at Tsushima. Thirty-six years later, the IJN executed Yamamoto’s strategy in the opening of the Pacific War.

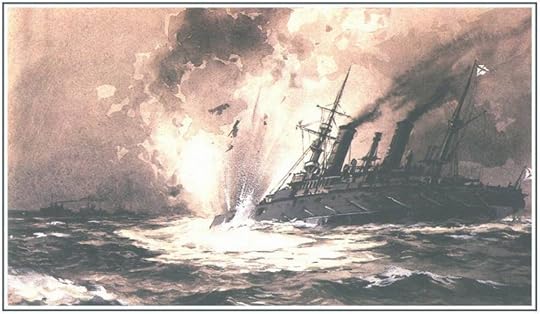

The sinking by mining of Makarov’s flagship Petropavlovsk. His death was a massive loss to the Russian war-leadership

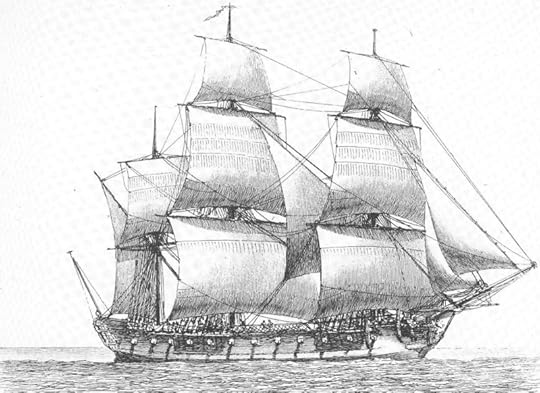

The late nineteenth century must have been an odd time indeed for naval officers who had grown up in the ‘Nelsonian’ tradition, with ships and tactics that hadn’t changed much in the preceding centuries. Royal Navy officer cadets training was aboard a vessel that wouldn’t have looked too out of place at Trafalgar. While the former HMS Prince of Wales had been launched in 1860 as a screw line of battleship, she was rendered obsolete by the arrival of HMS Warrior in 1861. Renamed HMS Britannia, she served as the training establishment from 1869 to 1905 (my great grandfather graduated as a midshipman in 1904). The officers who trained in that relic of the wooden walls adapted to a world of ironclads and torpedoes, having distinguished and often very long careers.

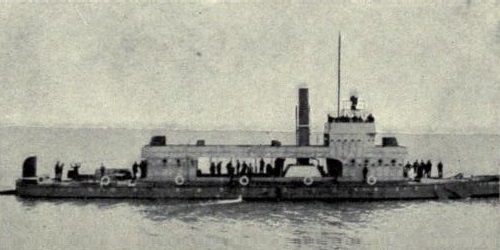

Jackie Fisher was one such, as was Roger Keyes. One particularly interesting character was Keyes’ great friend Walter ‘Tich’ Cowan. Cowan was born in Wales in 1871, the son of a Royal Welch Fusiliers officers. He entered Britannia at the same time as David Beatty, the two of them going on to serve together frequently. Between bouts of illness, Cowan managed to get involved in his fair share of action. A lot of this involved ‘in shore’ and river work, such as his command of the Nile gunboat Sultan supporting Kitchener’s army at Atbara and Omdurman, along with Beatty in command of Fateh, and then command of the whole gunboat squadron during the Fashoda Incident, winning his first DSO.

The gunboat Sultan which Cowan commanded in “The River War” of 1898 in the Sudan

Service as an ADC to the British commanders in the Boer War followed. One gets the impression that Cowan was a man who went looking for action, and didn’t much mind where he found it. He was, without doubt, a fire-eater. He developed a reputation as a fine destroyer commander after taking command of HMS Falcon and acting as Keyes’ deputy in the Devonport destroyer flotilla. In many ways, he was cut from the same cloth as Cochrane, Saumarez and other daredevil frigate captains. He was also a harsh disciplinarian, short-tempered and quick to judge, which did cause him some issues when he attained higher command.

Ships of Cowan’s Baltic Squadron at Libau in early 1919, HMS Caledon and destroyers HMS Wrestler and HMS Valhalla. Painting by Cecil King (1881 – 1942)

Cowan’sservice during and immediately after the 1st World War probably merits a blog post of its own, and his influence in the preservation of the independent Baltic states during the Russian Civil War is something I intend to return to. For current purposes, though, we will fast forward to the 2nd World War. Cowan had hauled his flag down for the last time in 1928, as a full Admiral and C-in-C of the Americas and West Indies Station. Although he was 68 at the outbreak of war in 1939, he wasn’t going to miss out on the chance to serve further and get into more fights.

Some sources suggest he was deemed too old for sea service but was approved for land service, which seems peculiar. What is certain is that he took a voluntary reduction in rank back to Commander (a rank he first achieved in 1901) and in 1941 was appointed by his old friend Admiral Roger Keyes(1872 – 1945), the first Director of Combined Operations, to liaise with the newly-formed Commando units and teach small boat handling – something that Cowan would have had a great deal of experience in the previous century.

Insect Class Gunboat in WW1, painting by W. L. Wyllie (1851 – 1931). Several survived to give further valuable service in WW2

Insect Class Gunboat in WW1, painting by W. L. Wyllie (1851 – 1931). Several survived to give further valuable service in WW2

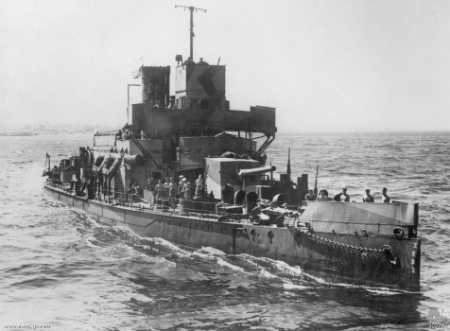

Cowan managed to find his way from this training post to active service with the Marines in the Mediterranean. During an abortive raid with the No.8 (Guards) Commando, he was often seen on the deck of the venerable Insect Classgunboat HMS Aphis blazing away at attacking aircraft with his Thomson SMG. The Guards decided he was seeking a glorious death in action – one feels that men who had volunteered from the Guards to be Commandos would be sufficiently hardbitten that they wouldn’t make this determination lightly!

HMS Aphis as Cowan would have known her when serving with her in WW2

From there, this venerable Naval officer somehow managed to attach himself to an Indian cavalry regiment (the 18th King Edward’s Own) and participated in the Battle of Bir Hakeim. Having shot his revolver empty, he was politely invited to surrender by the crew of the Italian tank he’d been shooting at (there are suggestions he captured a tank armed only with his revolver, before trying it on a second to less success). Released as part of a prisoner exchange but without the usual stipulation of not returning to service (one suspects his captors thought him too old), he wasn’t quite done. He returned to action with the Commandos in Italy and the Adriatic. No.2 Commando’s war diary records him being demobilised for the last time on the Croatian island of Vis, where he was seen off in great style by both local partisans and the Commandos.

He did not find the glorious death in battle that the Guards Commandos thought he was chasing, dying at 84 in 1956. Service in Italy had earned him a bar to his DSO, more than forty years after the first award, and he died a full Admiral and a Knight Commander of the Bath. By his own estimation, his greatest honour was being made the honorary Colonel of the 18th King Edward’s Own cavalry. I suspect he would also have been pleased to know that EML Admiral Cowan, a Sandown class minesweeper, has served the Estonian Navy since 2008.

===================================

Tim Chant, when not doing his day job, juggles far too many writing projects and his predictably geeky hobbies. He lives in Edinburgh with his partner and their two troublesome rabbits. As well as historical fiction, he also publishes science fiction as T.Q. Chant.

Tim Chant, when not doing his day job, juggles far too many writing projects and his predictably geeky hobbies. He lives in Edinburgh with his partner and their two troublesome rabbits. As well as historical fiction, he also publishes science fiction as T.Q. Chant.

The post Admiral Walter Cowan – Fire-eating naval officer and the oldest Commando appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 6, 2021

The “Royal Family” at War 1747

The “Royal Family” at War 1747The pursuit of the treasure ship Glorioso

The “Royal Family” at War 1747The pursuit of the treasure ship Glorioso

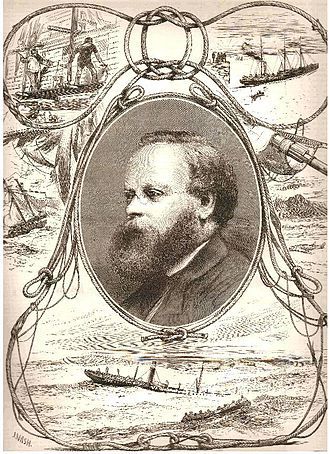

Pedro de la Cerda

The Glorioso’s captain

In 1747, at the height of the War of Austrian Succession, when Britain was (once more) at war with France and Spain, the departure of a Spanish warship from the Americas was to trigger a series of brutal naval engagements reminiscent of the pursuit of the Bismarck, two centuries later. The 70-gun ship-of-the-line Glorioso was carrying four-million silver dollars and as such was a prize well worth the taking. She was to be engaged both by the Royal Navy and by British privateers and it is the performance of the flotilla of the latter, nicknamed “The Royal Family”, which was the most remarkable.

The Glorioso’s first encounter with the enemy was off the Azores on July 25th when she encountered a British convoy of seven merchantmen, escorted by three Royal Navy vessels. The largest was HMS Warwick – a 60-gun ship comparable to the Glorioso, HMS Lark, a 40-gun frigate, and a 20-gun brig. The escort commander ordered the brig to stay with the merchant ships and the Lark to initiate the attack, with the slower Warwick following. By the time HMS Warwick arrived the Glorioso had badly damaged the Lark but was herself so badly raked that she was partially dismasted. The Spaniard sailed on, having taken structural damage and some casualties, and the British ships broke off the action – one indeed which they might have been victorious in had they persisted.

Outcome: Round One to Glorioso.

Nearing the Spanish coast, off Cape Finisterre, the Glorioso now encountered three further British ships, the same combination as before of a ship-of-the-line (HMS Oxford, 50-guns), a frigate (HMS Shoreham, 24 guns) and a brig (HMS Falcon 20 guns.) In an engagement lasting three hours all the British ships were damaged and the Glorioso, though she had lost her bowsprit, escaped to the harbour of Corcubión, in North-West Spain. There she off-loaded her silver cargo.

Outcome: Round Two to Glorioso .

Her repairs compete as much as Corcubión’s facilities would allow, the Glorioso headed for the well-equipped base of Ferrol, further north. Adverse winds, which damaged the rigging, made the Glorioso’s Captain de la Cerda to head south instead towards Cadiz. Fully aware of the presence of British units, he decided to stay far off the Portuguese coast. In the event however, this availed him nothing and on October 17th the Glorioso ran into a squadron of British privateers – not Royal Navy ships – close to Cape Saint Vincent.

George Walker

At this point it’s appropriate to pause to look at the nature and composition of this privateering squadron. It was commanded by teh 47-year old Captain George Walker but funded by private financial interests in London and Bristol. Walker’s reputation was already high and on a previous voyage each ordinary seaman under him had received £850 as his share of prize money – a quite enormous sum at the time. Walker had therefore no trouble in recruiting hands for his next venture and in April 1746 he sailed from Britain with four ships named King George, Prince Fredrick, Duke and Princess Amelia, carrying between them 960 men and 120 guns. By the time this force entered Lisbon eight months later prizes worth some £220,000 had been taken without the loss of a single man. After adding two more vessels to his squadron – the Prince George and the Prince Edward – Walker sailed out from Lisbon in July 1747 to resume commerce raiding. His six-ship task force had by now become commonly known as “The Royal Family”.

The Prince Edward was lost soon afterwards in an unusual accident. She had crowded on so much canvas that pressure above pulled the heel of the mainmast out of its step, the mast then plunging down to smash a hole in the ship’s bottom. Only three men survived the rapid sinking that followed. Despite this setback the Royal Family was to have a profitable cruise and in early October put in to Lagos Bay to take on water. From here, in the early morning of October 17th, a large ship was seen approaching – this was the Glorioso. Only two of Walker’s ships were ready to give chase, the King George, with thirty-two guns and 300 men, and the Prince Fredrick with twenty-six guns and 260 men.

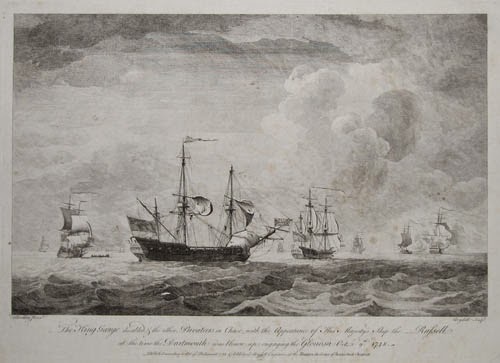

Glorioso (left) in action with King George and Prince Fredrick

Glorioso (left) in action with King George and Prince Fredrick

The chase continued until midday, when the King George came up to the Glorioso. At this point the wind fell to dead calm, leaving the Prince Fredrick too far back to render support to her consort. King George and Glorioso lay at a distance from each other, all but motionless, for some five hours, the latter with the lowest tier of guns run out. Only thereafter did a light breeze spring up and the Glorioso headed for Cadiz, with King George in close pursuit and the Prince Fredrick following at a distance. By 2000 hrs King George was close enough to pull alongside Glorioso and hail her – it appears that there might still have been some idea that the Spaniard was an armed merchantman that might decline to fight. Glorioso replied with a full broadside, knocking out two of King George’s guns and bringing down her main topsail yard. The fire was returned and what was to be a three-hour battle commenced.

What saved the King George from outright destruction appears to be that the Glorioso’s gun-ports were so small and her sides so thick that her guns could only be trained or depressed at a very limited angle. The consequence was that hitting a small vessel such as the King George was difficult in the extreme. Despite this however, three hours pounding at close range (how did flesh and blood endure it?) King George had suffered serious damage to her masts and most of her standing rigging had been shredded. Only after the Prince Fredrick, driven by a very light wind, arrived about 2230 hrs did the Glorioso break off the action and head for Cadiz.

OUtcome: Round Three to Glorioso, but only just.

Walker did not order immediate pursuit. In the morning however, realising that the King George’s injuries were not fatal and that his crew had sustained low casualties, and because the Duke and Prince George, and later the Princess Amelia, had now also joined him, he sent his other ships off after the Glorioso, following as best he could in King George.

A large ship was now seen approaching from the east and on recognising it as a British warship Walker sent a note by one of his boats to explain the situation. She was the 80-gun HMS Russell, homeward bound from the Mediterranean and her captain now joined the Royal Family in the chase.

Glorioso (left) in action against HMS Dartmouth

Glorioso (left) in action against HMS Dartmouth

Glorioso was still ahead of her pursuers when yet another British warship, the 50-gun Dartmouth, which had been cruising to the west and had been attracted by the sound of gunfire, now met her on an interception course. A running fight developed, in the course of which a fire reached HMS Dartmouth’s magazines and she blew up. Out of a crew of 325, only fifteen were saved. One of these was a young lieutenant, John O’Brien, who was picked up off a floating gun carriage. When taken on board the Duke it appeared that he had been blown through a gun port. Though his clothes were burnt and in tatters, he excused himself to the Duke’s captain with the words “Sir, you must excuse the unfitness of my dress to come aboard a strange ship, but, really, I left my own with so much precipitation that I had not time to put on better.”

Outcome: Round Four to Glorioso, and decisively so.

Glorioso engaging HMS Russell in her last fight

Glorioso engaging HMS Russell in her last fight

In the background: remains of HMS Dartmouth (left) and crippled King George (right)

The remaining pursuers, awed by the disaster to HMS Dartmouth held off attacking. At midnight however HMS Russell ran up beside Glorioso and began a five-hour long close engagement. After they had been through so much already one wonders how Glorioso’s crew were in a position to put up anything of a fight, yet they did so with great tenacity, despite 33 dead and 130 wounded. It was only at dawn that she finally struck her colours, dismasted and on the point of sinking.

Outcome: Round Five to the British, victory by knockout.

Or so it might have seemed. It appears to have been only after surrender that it was learned that the Glorioso’s silver had already been landed. Had this been known it could have been unlikely that Walker would have risked the Royal Family – the privateering enterprise was aimed at profit, not Britain’s national interest. One of Walker’s backers afterwards gave him “a very uncouth welcome for venturing the ship against a man-of-war”. Walker responded elegantly: “Had the treasure been aboard the Glorioso, as I expected, my dear sir, your compliment would have been far different. Or had we let her escape from us with the treasure aboard, what would you have said then?”[image error]

State of King George near the end of the last battle

State of King George near the end of the last battle

After surrender, the Glorioso’s Captain de la Cerda and his crew were brought to Britain as prisoners. De la Cerda was to be honoured as much by the British for his achievement as he was by Spain itself, which later rewarded him with promotion to commodore.

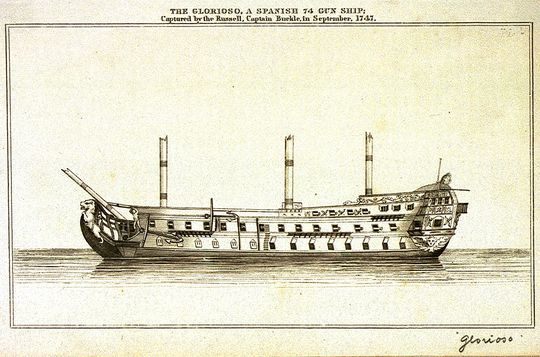

Glorioso as captured, too badly damaged to be taken into British service

Glorioso as captured, too badly damaged to be taken into British service

And Walker? He continued cruising until the end of the war, the Royal Family’s total prize money being reckoned as more than £400,000. His subsequent career was less glorious. He appears to have lost or squandered the money he had won with the Royal Family, got involved in a dispute with shipowners about accounts, and was imprisoned for debt in the late 1750s and died in 1777. No matter what happened later however, nothing could take away the fact that he had been one of the few captains who ever ran a small and outgunned ship against a 70-gun ship and engaged her yard-arm to yard-arm.

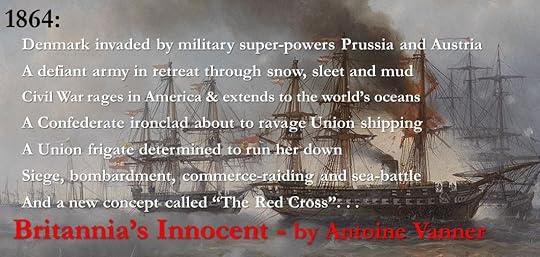

Start the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventures with the earliest chronologically:Britannia’s Innocent For more details regarding purchase in paperback or Kindle format, click below Note that Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read at no extra chargeFor amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to nine volumes, and counting, Click on the banner below for details.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The “Royal Family” at War 1747 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 9, 2021

Arrival of the Naval Mine

The Arrival of the Naval Mine

The Arrival of the Naval MineFrom the mid-19th Century onwards the naval mine developed into the general from we know today and which was to play a significant role in the American Civil War, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, both World Wars and the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88. The famous order by Admiral Farragut as he drove his squadron into Mobile Bay in 1864 – “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” – referred to mines, then often labelled at the time as torpedoes, and not the automotive weapons that emerged in the next decade. The concept of the floating mine had been around for centuries – often in the form of boats that would be allowed to drift downriver towards enemy bridges. The weakness was however that explosion would essentially be random, whether close to the enemy or not, as detonation would depend on a slow-burning fuze or a clockwork mechanism. The arrival of practical electrical technology in the 1850s and 60s got around this problem, allowing controlled detonation from shore of submerged mines, or detonation by systems integral to the mine itself and triggered by contact.

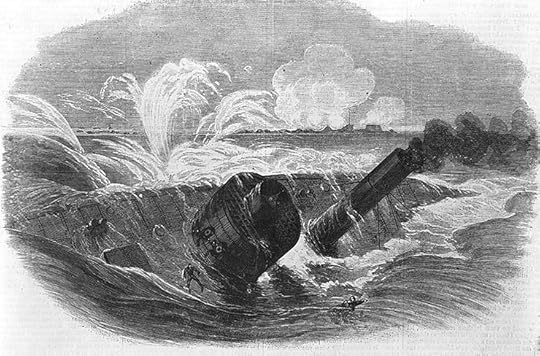

USS Tecumseh sunk by a mine in Mobile Bay, 1864

USS Tecumseh sunk by a mine in Mobile Bay, 1864

As the Confederate defences of Mobile Bay demonstrated, mines proved a very effective, and relatively cheap, way of defending harbour approaches – as was shown by the dramatic sinking of a unit of Farragut’s squadron, the monitor USS Tecumseh. (One episode in my novel Britannia’s Wolf describes the protection of a major Russian Black Sea anchorage in 1877 by mines anchored across the entrance and controlled through electrical cables connected to observation posts onshore).

[image error]

Destruction by mine of the Russian battleship Petropavlovsk off Port Arthur, 1904

Destruction by mine of the Russian battleship Petropavlovsk off Port Arthur, 1904

She took with her Russia’s best naval commander, Admiral Makarov

(Strange to see this tragedy used to decorate a box of chocolates!)

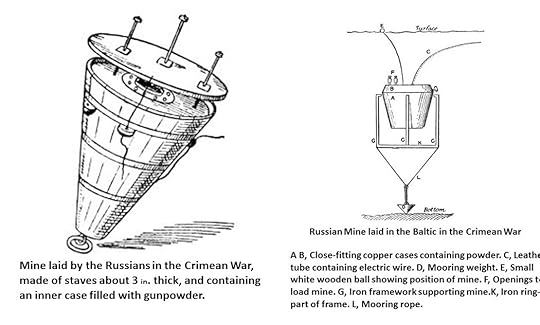

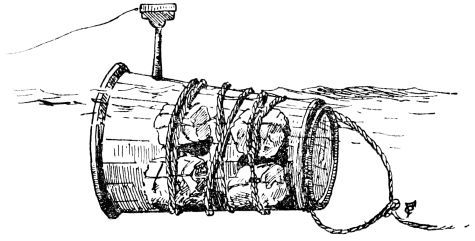

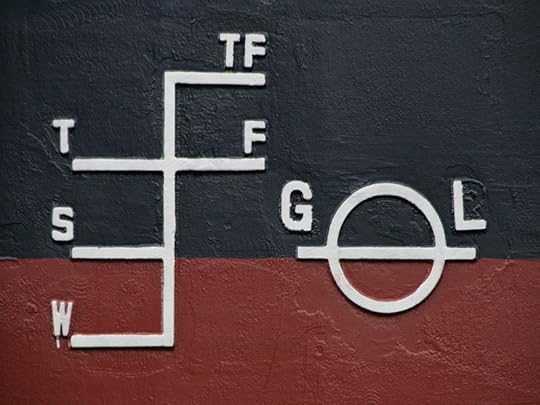

In view of my interest in such weapons systems, I was fascinated to find sketches of early mines in a publication called “The British Navy Book” by Cyril Field, apparently published in 1915/16. It indicated that the first large-scale use of practical mines occurred in the Crimean War (1854-56) when the Russians deployed them in both the Baltic and the Black Sea to limit the movements of British and French warships. The approaches to the great Russian naval base at Kronstadt, outside St. Petersburg, were protected in this way and some fifty mines were “trawled up” in ten days and destroyed by British forces. The improvised technique used was hazardous in the extreme – two pulling- boats suspended a long rope between them and it was sunk by heavy weights to a depth of ten or twelve feet, and held suspended at that depth by empty casks as floats. The boats then separated as far as the rope would allow, and rowed onwards. There appears to have been several types of mine, some of copper, others of wooden staves like those of a barrel, and the bursting charge was 700 pounds of gunpowder. Detonation seems to have been either by a “galvanic current” sent through a cable from a shore station or by contact, the exact mechanism being unspecified. The drawings below give details of Russian mines encountered by the British.

Britain was soon afterwards in conflict in war with China in the so-called Arrow War of 1856/60. The 890-ton screw corvette HMS Encounter came under attack by floating mines launched by the Chinese when operating in the Pearl River (now called the Guangdong) downstream of Canton (known as Guangzhou today). The book mentioned earlier provides extracts from a letter written by an officer on board Encounter.

HMS Encounter, shown here in China in 1862 (Note telescopic fummel)

HMS Encounter, shown here in China in 1862 (Note telescopic fummel)

The first attempt, on 24th December 1856, involved an explosive-laden sampan towed close by another craft, and then let loose to drift down towards Encounter’s bows. It was captured by a ship’s boat acting as guard and fuses burning inside bamboo tubes were extinguished in time to prevent explosion.

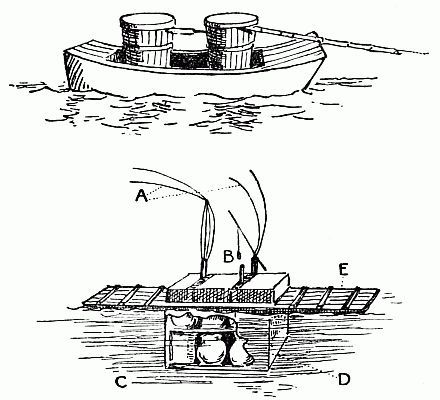

The second attempt, in the early hours of on 5th January was potentially more lethal. The officer’s letter states that the attack was by “two rafts, moored together, with about 20 fathom of line buoyed up, with hooks to catch cables or anything else, and, on the wires touching the ship’s side, to break by the little lead weight the lighted fuse on the top of the bamboo, which communicated with the powder. These were lighted and all ready, but fortunately observed by our guard-boat and towed clear of ship. Being only a raft it was just awash, and in each caisson at least 17 cwt. (i.e. 1904 pounds or 865 kilograms ) of gunpowder in open tubs and jars. The raft itself was made of 6-inch plank well bound together, and caulked.”

The second attempt, in the early hours of on 5th January was potentially more lethal. The officer’s letter states that the attack was by “two rafts, moored together, with about 20 fathom of line buoyed up, with hooks to catch cables or anything else, and, on the wires touching the ship’s side, to break by the little lead weight the lighted fuse on the top of the bamboo, which communicated with the powder. These were lighted and all ready, but fortunately observed by our guard-boat and towed clear of ship. Being only a raft it was just awash, and in each caisson at least 17 cwt. (i.e. 1904 pounds or 865 kilograms ) of gunpowder in open tubs and jars. The raft itself was made of 6-inch plank well bound together, and caulked.”

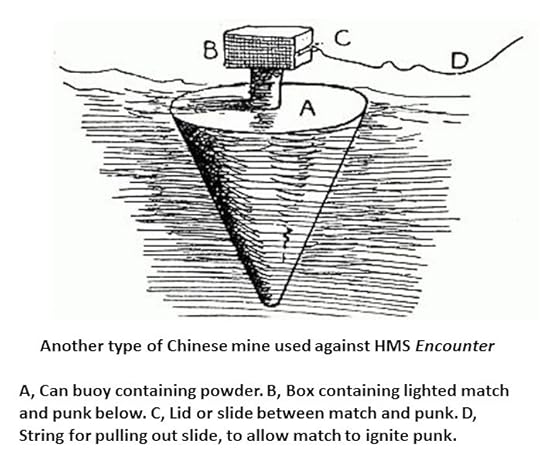

HMS Encounter was attacked again two days later, again in the early morning hours of darkness. It seems to have been guided into position by swimmers – an act of considerable heroism. According to the unnamed British officer “A pair of vessels in the shape of a can-buoy with a flag on the top, about 8 inches long; the fuse, with a tin box containing punk (i.e. tinder) over the fuse, then a cover with a lighted match on top; this had a string to it, which, when pulled, drew out the centre partition and communicated the fire to the punk, to allow the fellows who swam off with them towards the ship to make their escape; but they got frightened at some stir with the boats, and by accident one went off with a fearful explosion on the starboard bow, about 60 yards, and the other, being deserted, floated down on our booms. One of the men was caught and brought on board here, and had his brains blown out at the port gangway. The buoy-shaped vessel was capable of holding about 10 cwt. (i.e. half a ton) of gunpowder.”

One final attempt on the Encounter was again by two floating mines coupled together by a length of rope, each containing half a ton of powder. They were towed close by a small boat but it was detected by the ship’s look-outs and destroyed by gunfire. Had these attacks been successful it is hard to imagine the Encounter surviving and one is struck by the courage of the Chinese who manoeuvred these contraptions into position. Crude though they might have been, the era of mine-warfare had commenced.

One final attempt on the Encounter was again by two floating mines coupled together by a length of rope, each containing half a ton of powder. They were towed close by a small boat but it was detected by the ship’s look-outs and destroyed by gunfire. Had these attacks been successful it is hard to imagine the Encounter surviving and one is struck by the courage of the Chinese who manoeuvred these contraptions into position. Crude though they might have been, the era of mine-warfare had commenced.

It’s 1877 and the vicious Russo-Turkish War is reaching its climax.

It’s 1877 and the vicious Russo-Turkish War is reaching its climax.

A Russian victory will pose a threat to Britain’s strategic interests. To protect them an ambitious British naval officer, Nicholas Dawlish, is assigned to the Ottoman Navy to ravage Russian supply-lines in the Black Sea. In the depths of a savage winter, as Turkish forces face defeat on all fronts, Dawlish confronts enemy ironclads, Cossack lances and merciless Kurdish irregulars, and finds himself a pawn in the rivalry of the Sultan’s half-brothers for control of the collapsing empire. And in the midst of this chaos, unwillingly and unexpectedly, Dawlish finds himself drawn to a woman whom he believes he should not love.

Neither for his own sake, nor for hers…

Britannia’s Wolf features a naval hero who is more familiar with steam, breech-loaders and torpedoes than with sails, carronades and broadsides. Dawlish joined as a boy a Royal Navy still commanded by veterans of Trafalgar but he will help forge the Dreadnought navy of Jutland and the Great War. Other books in the series follow him further along that path. Click here, or on the cover image, for more details.

Below are the nine Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Arrival of the Naval Mine appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 11, 2021

The Aceh Wars begin 1873-74

The Dutch East Indies Ulcer – the Aceh Wars begin 1873-74

The Dutch East Indies Ulcer – the Aceh Wars begin 1873-74The history of the Netherlands in the 19th Century is a closed book for most non-Dutch, not least because of the incorrect perception that “little happened” and as the country was at peace in Europe from 1831 to 1940. The Netherlands were however involved in a series of colonial campaigns in the vast territory of the Dutch East Indies, which constituted most of what is the present-day nation of Indonesia.

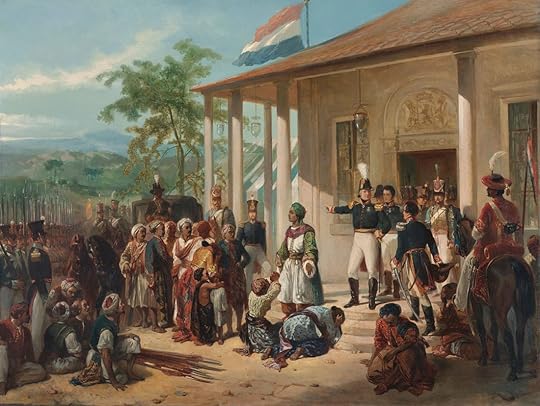

Dutch power in the East Indies – end of “The Java War” in 1830

Dutch power in the East Indies – end of “The Java War” in 1830Painting by Nicolaas Pieneman shows submission of a local prince.There had been a Dutch presence on the island of Java since the early seventeenth century and the island had become the focus of intense British and French rivalry during the Napoleonic Wars. Dutch power was spread more thinly elsewhere and the nineteenth century saw a succession of campaigns to bring the entire archipelago under control. The instrument for this was the KNIL – the Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army. Established in 1830, this force was not part of the Dutch Army (which only served at home) and was not entitled to make use of Dutch conscripts. Funded by the colonial budget, it fell under the command of the Governor-General of the East Indies. It accepted volunteers of other European nationalities in addition to many from the Netherlands itself – one unlikely example being the French poet Arthur Rimbaud (1854 –1891) who joined in 1876, served for four months and then deserted. The officers and non-commissioned officers were mainly European (typically Dutch, German, Belgian and Swiss) but the majority of the troops were indigenous Indonesians, mainly from Java. In the KNIL’s earlier years several thousand African soldiers were recruited from the small Dutch holdings on the Gold Coast (Modern Ghana).

Location of Aceh – with thanks to Google Earth

Location of Aceh – with thanks to Google Earth

The greatest – and most sustained – challenge faced by the KNIL was the series of difficult campaigns from 1873 to 1914 which became known collectively as the Aceh War. Though not a single continuous conflict, it never achieved outright resolution – traces of resistance persisted until the Japanese invasion in 1942 – and it represented a steady drain on Dutch resources. Aceh represented the northern tip of Sumatra and as a sultanate had its independence guaranteed by an Anglo-Dutch Treaty in 1824. In the following decades, it became a rich regional power, its wealth based on production of half the world’s pepper. Smaller local rulers were brought under control by the reigning sultan and Aceh power extended steadily southwards, coming into collision with the Dutch, who by this stage were extending their influence northwards. Piracy represented a profitable sideline for some of the coastal communities, leading to punitive expeditions by the US Navy in 1832 and 1838. (These will be the subject of a future blog). The situation was complicated by the fact that there were still British claims to Sumatra, though these were not pressed.

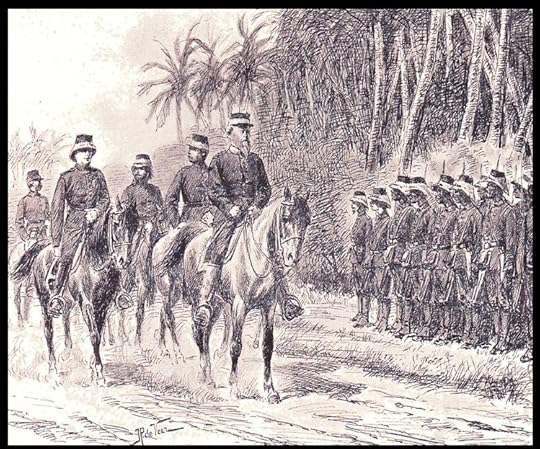

A senior KNIL officer inspecting local troops in 1870s

The situation changed in 1871 when a treaty was signed between Britain and the Netherlands which gave the Dutch a free hand in Sumatra, as well as the obligation to suppress piracy, in return for the Dutch giving up its holdings on the Gold Coast. While the Ache Sultanate remained independent it represented a major obstacle to Dutch control of the enormous 182,800 square mile island – the sixth-largest in the world. Concern was raised in the Dutch colonial government in 1873 when the Sultanate initiated negotiations with the American government about a bi-lateral treaty – potentially introducing another major player – and the decision was taken to annex Aceh militarily. The campaign for doing so was to prove hastily and inadequately planned and resourced. The over-optimistic objective was to bombard the Sultan’s capital at Bandar Aceh, at the island’s northern tip, and to seize the town as a base for further efforts to occupy the coastal areas. It was anticipated that seizure of the sultan and his palace would trigger a collapse in resistance.

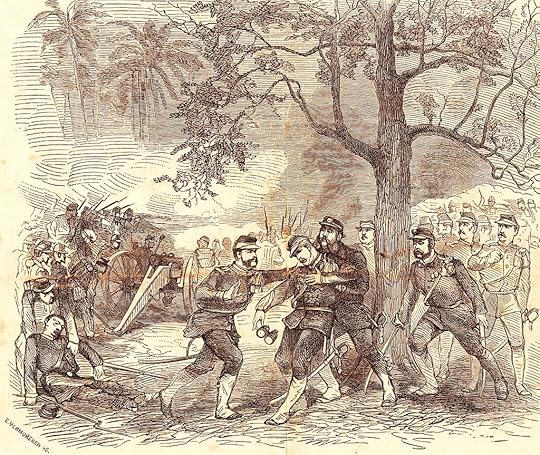

The death of

General Johan Köhler 14th April 1873

The death of

General Johan Köhler 14th April 1873

The sultanate’s ability to resist was badly underestimated as significant numbers of modern weapons had been imported to Aceh. In April 1873 the Dutch force’s attempt to storm the palace was bloodily repulsed and the commander, General Johan Köhler (1818 – 1873) was killed, together with some 80 of his troops. Recognising that the situation was impossible, Köhler’s deputy, now in command, ordered a retreat and the expeditionary force returned to Java. A Dutch naval blockade was now imposed and efforts by the sultanate to get support from the United States and from the Ottoman Empire proved fruitless. Aceh was on its own.

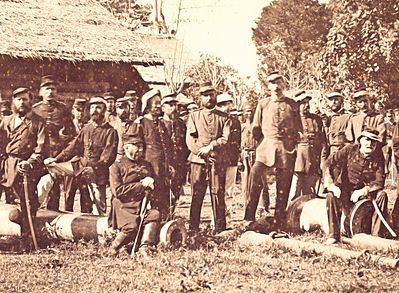

KNIL officers at Banda Aceh, January 1874

KNIL officers at Banda Aceh, January 1874

The defeat had been humiliating for Dutch prestige and a second, and larger, expedition was mounted later the same year. Commanded by General Jan van Swieten (1807 –1888), this was a much better-resourced effort. It was the largest offensive that the Dutch had yet mounted in the East Indies – 8,500 troops, 4,500 porters and labourers, with a further 1,500 troops being deployed after the initial landings. The timing proved disastrous as it coincided with a cholera outbreak that respected neither side. Recognising that direct confrontation was futile, the Sultan abandoned Bandar Aceh to the Dutch forces in early 1874. He relinquished the symbolically important palace and took to the hills and forests to the south to conduct a guerrilla campaign. In the six months from November 1873 to April 1874 the Dutch force lost 1,400 men – and this was only the beginning

KNIL officers – possibly with captured Sultanate artillery – Banda Aceh, 1874

A vicious six-year guerrilla conflict then began, with both sides suffering heavy casualties, and with tropical diseases continuing to represent as significant a hazard as enemy action. In 1880 the Dutch realised that, for now at least, outright conquest would prove impossible. The war was proclaimed to be at an end and Dutch forces settled down to defending the areas they controlled, primarily that around Banda Aceh. While using their naval forces to patrol the coastline they initiated an effort to draw up treaties with local leaders.

A two-year period of civilian rule followed – during which increasing violence showed that resistance to Dutch rule was not at an end. In late 1883 military rule was again imposed and, in a steadily worsening situation, it was recognised that the war had reignited and a new, and even deadlier, phase was beginning. But that’s another story!

Start the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventures with the earliest chronologically:Britannia’s Innocent For more details regarding purchase in paperback or Kindle format, click below Note that Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read at no extra chargeFor amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to nine volumes, and counting, Click on the banner below for details.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The Aceh Wars begin 1873-74 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 14, 2021

The Vega Expedition and the North-East Passage 1878-79

The Vega Expedition and the North-East Passage 1878-79

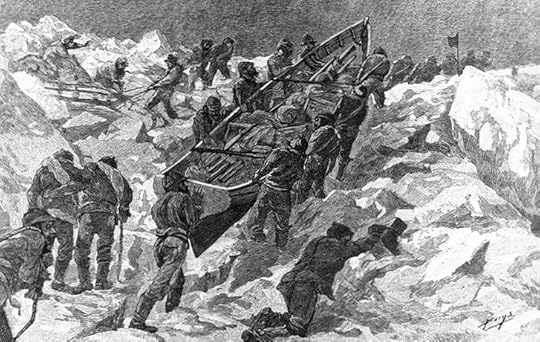

The Vega Expedition and the North-East Passage 1878-79In a recent blog, I described the disastrous American Jeanette expedition of 1878/81 – an attempt to reach the North Pole by sea after entering the Arctic via the Bering Strait. (Click here to read it if you missed it previously). The venture was all but doomed from the start as the plan was based on a false premise. This was that the ice on the edge of the Arctic Ocean was only a narrow barrier, with open water beyond, and the premise was based on scant – and misinterpreted – evidence and wild supposition. The officers and crew of the USS Jeanette were to endure appalling hardships and to display limitless courage in rescuing themselves – which not all were successful in doing.

Contemporary illustration: USS Jeannette’s crew hauling boats and sledges across the ice

Finding the North-West Passage, across the north of Canada, that would allow the Orient to be reached from Europe by a shorter route than around the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn, was to be the focus of exploration – and tragedy – for some three centuries. The search was to involve spectacular hardship, failure and loss of life and it was only in the years 1903 to 1906 that Roald Amundsen, in a tiny fishing boat called the Gjøa, navigated the entire route for the first time. Though an epic achievement – which included getting locked in the ice for two years – it also demonstrated that the route was not practical for regular traffic. The Jeannette’s is an inspiring story of valour and resourcefulness, but also one of greed and callousness on the side of the ruthless press-baron who financed the undertaking as a publicity stunt. While the Jeannette was setting out, it was known that a Swedish vessel, the Vega, was attempting the North-East Passage, and if she were to be successful might be emerging from the Bering Strait at around the same time that the Vega would be entering it. What follows is a very brief summary of the Vega’s achievement.

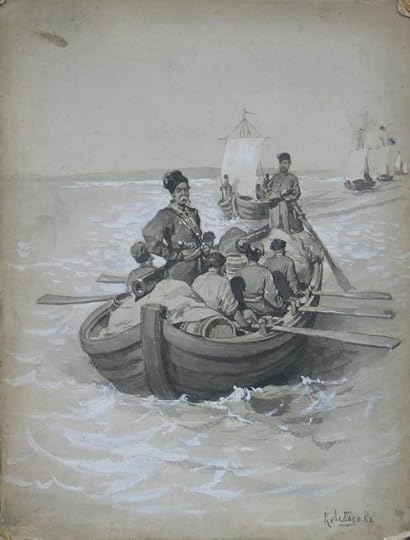

Dezhnev Expedition, as imagined by

a 19th Century illustrator

The North-West Passage’s counterpart was the North-East Passage, the route across the north of Europe and Asia, from Norway’s North Cape to the Bering Strait. From the sixteenth-century onwards British and Dutch ships had been trading with the White Sea in Northern Russia and had ventured as far east as the island of Nova Zembla – an amazing achievement considering the hazards involved. Further progress east was subsequently made eastwards, along the coast by Russian vessels, but winter ice always proved a block to a single continuous passage to the Bering Strait. The Russian achievement was however spectacular. The 17th Century saw the penetration of Russian explorers and settlers into Siberia, not only across the landmass but along the northern coast bordering the Arctic Ocean and reaching the estuaries of the vast rivers Ob, Yenesei and Lena. These efforts were facilitated by the use of “Koch” vessels – small sailing craft with reinforced skin-planking that were equipped to deal with ice. The greatest achievement of these years came in 1648 when a Russian explorer named Semyon Dezhnev descended the Kolyma river in north-eastern Siberia, reached the Arctic Ocean and travelled eastwards to emerge into the Northern Pacific through the Bering Strait. Of seven boats involved only two made it the whole way. (This expedition is largely forgotten outside Russia. (If any of my Russian blog-followers – of whom there are many – would like to contribute a guest blog on this I would be delighted to host it).

With Dezhnev’s heroic achievement left in obscurity, the credit for achieving the first North-East Passage has usually been attributed to Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskjold (1832 – 1901). First or not, Nordenskjold’s voyage was an epic in its own right, and a triumph of systematic planning and sound leadership. Born in Finland – which was at that time ruled by Russia – and from an aristocratic Swedish/Finnish family, Nordenskjold qualified as a geologist at the University of Helsinki and after graduation in 1853 undertook a mineralogical study in the Urals. Russian rule was resented by the Finns and Nordenskjold, outspoken on the subject, drew such unwelcome attention from the authorities that he moved to Sweden in 1857, establishing himself as curator of mineralogy at the Swedish Museum of Natural History. By now interested in the Arctic, he participated in an unsuccessful 1861 expedition which attempted to reach the North Pole by means of dog-sledges from the north coast of Spitzbergen. He returned to the Arctic several times in the following years and in 1868 reached the highest northern latitude yet attained in the eastern hemisphere. This was followed by an expedition to Greenland in 1870 and a return thereafter to Spitzbergen. In a series of voyages, he once more achieved a “furthest north” record and in 1875 he pushed as far eastwards as the mouth of the Yenisei, one of the three great rivers that flow north from Siberia into the Arctic Ocean. These expeditions established him as the most experienced Arctic explorer of his day and he was now convinced that – with correct timing to take account of summer ice-melting – it would be possible to complete the North-East Passage. He gained a powerful patron for this scheme, King Oscar II of Sweden.

Nordenskjold – meticulous planner

Systematic in all he undertook, Nordenskjold, set out his plans and schedule in detail: “It is my intention to leave Sweden in July 1878 in a steamer specially built for navigation among ice, which will be provisioned for two years at most. The course will be shaped for Nova Zembla, where a favourable opportunity will be awaited for the passage of the Kara Sea. The voyage will be continued to the mouth of the Yenisei, which I hope to reach in the first half of August. As soon as circumstances permit, the expedition will continue its voyage along the coast to Cape Chelyuskin, where the expedition will reach the only part of the proposed route which has not been traversed by some small vessel, and is rightly considered as that which it will be most difficult for a vessel to double during the whole North-East Passage; but our vessel, equipped with all modern appliances, ought not to find insuperable difficulties in doubling this point, and if that can be accomplished, we will probably have pretty open water towards Behring’s Straits, which ought to be reached before the end of September. From the Bering Strait the course will be shaped for some Asiatic port and then onwards round Asia to Suez.”

With Oscar II’s support, a subscription was raised to fund the expedition. A ship was purchased, the Vega, of 300 tons, formerly used in walrus-hunting in northern waters, and she was further strengthened to withstand ice. She left Sweden in early July 1878, carrying supplies for thirty people for two years. An especially impressive achievement was that fresh bread was to be baked during the whole expedition that followed.

Having rounded the North Cape and entered the Arctic Ocean, the Vega made good time through ice-free waters, passing into the Kara Sea east of Nova Zembla at the beginning of August, then anchoring briefly at mouth of Dickson Island, north of the Yenisei mouth. The Vega pushed on in fog and on 19th August reached Cape Chelyuskin, the most northerly point of the Asian landmass. It was appropriate that as the fog lifted there a polar bear was sighted. Nordenskjold was to write later that “here we reached the great goal, which for centuries had been the object of unsuccessful struggles. For the first time a vessel lay at anchor off the northernmost cape of the Old World. With colours flying on every mast and saluting the venerable north point of the Old World with the Swedish salute of five guns, we came to anchor.”

The Vega at Cape Chelyuskin, observed by a polar bear

The Vega at Cape Chelyuskin, observed by a polar bear

Painting by Jacob Hägg (Source Wikipedia)

Cape Chelyuskin had been named after one of the leaders of a Russian expedition that had reached it by a land journey in 1742 which had entailed terrible hardships and suffering. The Vega left a cairn there over a box that contained a message describing the status of the expedition at this point and headed eastwards on August 20th.

Nordenskjold & Vega in the ice

Painting by Georg von Rosa, 1886

Progress now became steadily more difficult as the Vega pushed on. Thick fog made navigation through increasing numbers of ice-floes dangerous. Notwithstanding this, the Vega reached the mouth of the Lena 27th August. From this point conditions improved and fast progress was made through an ice-free sea and hopes began to rise of completing the passage before the full onset of winter. This soon proved over-optimistic. Snow fell from September 1st and fog again descended. Ice was pushing down from the north and progress was only possible by hugging a narrow ice-free channel near the coast. Contact was however made with Chukchi, an indigenous people of North-Eastern Siberia. These were the first people the Vega’s crew has seen for six weeks and they were dressed in reindeer skins with tight-fitting trousers of seal-skin, shoes of reindeer-skin with seal-skin boots and walrus-skin soles. In very cold weather they wore hoods of wolf fur with the head of the wolf at the back. Nordenskjold, wrote later that “Although it was only five o’clock in the morning, we all jumped out of our berths and hurried on deck to see these people of whom so little was known. The boats were of skin, fully laden with laughing and chattering natives, men, women, and children, who indicated by cries and gesticulations that they wished to come on board. The engine was stopped, the boats lay to, and a large number of skin-clad, bare-headed beings climbed up over the gunwale and a lively talk began. Great gladness prevailed when tobacco and Dutch clay pipes were distributed among them. None of them could speak a word of Russian; they had come in closer contact with American whalers than with Russian traders.”

The mention of “American whalers” was significant since it indicated that some vessels at least had reached that point from the east, and that open water must exist for some part at least of the year. Nordenskjold therefore pressed on through snow and ice and fog in the hope of getting through to the Pacific before the sea was completely frozen over. But the ice was beginning to close. Large blocks were constantly hurled against the Vega, threatening her destruction.

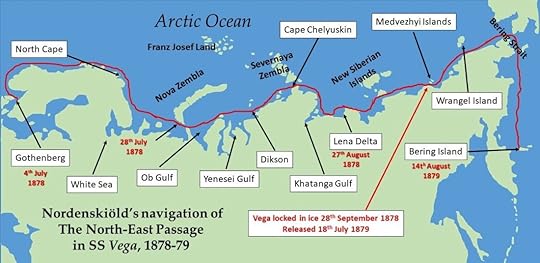

Vega’s voyage and key dates

On 28th September, the struggle eastwards ended and the Vega was frozen inextricably into the ice. Nordenskjold estimated that this was only 120 miles distant from the Bering Strait, a fact all the more galling as 2400 miles had already been covered since leaving Sweden. Nordenskjold’s meticulous planning stood the Vega and her crew in good stead for the coming winter months and food was not going to be a problem. Locked as she was in the ice, the vessel was close to a settlement of Chukchi. These hospitable people helped the crew to enliven the winter with short expeditions inland on dog-sledges when weather permitted. The trapped ship was enshrouded by snow and it was reported to penetrate every nook and cranny where the wind could find an opening. Morale remained high however and Christmas was celebrated in the traditional Swedish manner.

The first hopes of release came in the following April (of 1879) when large flocks of geese, eider-ducks, gulls, and little song-birds began to arrive, some perching on the Vega’s rigging. This proved a false dawn however and the ship remained locked in the ice during May and June. It was not until 18th July 1879 that, as Nordenskjold wrote, “the hour of deliverance came at last, and we cast loose from our faithful ice-block, which for two hundred and ninety-four days had protected us so well against the pressure of the ice and stood westwards in the open channel, now about a mile wide. On the shore stood our old (Chukchi) friends, probably on the point of crying, which they had often told us they would do when the ship left them.” The Vega pressed on between closely packed ice with occasional glimpses through the fog of the coastline until she could at last swing southwards to encounter the heave swell of the Pacific Ocean at what was the Bering Strait. On 14th August, less than a month after breaking free, the Vega anchored at the Russian settlement on Bering Island to be greeted by a voice calling out in Swedish, “Is it Nordenskiöld?”

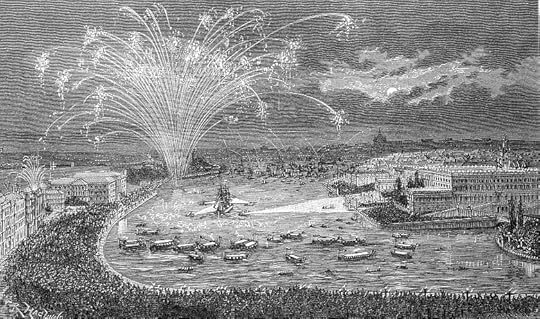

Vega’s welcome as she arrived back in Stockholm, 24th April 1880

Nordenskjold was to make one more Arctic expedition, in 1882-83, this time to Greenland, and again in the Vega. Thereafter his career was academic and in 1901 he was nominated to receive the first Nobel Prize for Physics though he died before the award. Relatively little-remembered today, he must count as one of the greatest of all Polar explorers, the meticulous nature of his planning and his strict scientific approach ensuring success. What followed was almost an anti-climax compared with what had gone before, a triumphal progress home that included Nordenskjold’s reception by the Emperor of Japan – who presented him with a medal. On 24th April 1880 the weather-beaten Vega, accompanied by flag-decked flotillas of admirers, sailed into Stockholm and an ecstatic welcome, led by Oscar II, who ennobled Nordenskjold as a baron.

He deserved the honour and deserves to be remembered.

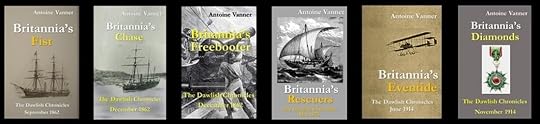

Do you enjoy naval fiction?You may enjoy Britannia’s Spartan

Click on image for details & reviews

It’s 1882 and Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

Dawlish has no forewarning of the nightmare of riot, treachery, massacre and battle he and his crew will encounter.

A new balance of power is emerging in the Far East. Imperial China, weak and corrupt, is challenged by a rapidly modernising Japan, while Russia threatens from the north. They all need to control Korea, a kingdom frozen in time and reluctant to emerge from centuries of isolation.

Dawlish finds himself a critical player in a complex political powder keg. He must take account of a weak Korean king and his shrewd queen, of murderous palace intrigue, of a powerbroker who seems more American than Chinese and a Japanese naval captain whom he will come to despise and admire in equal measure. With each step he must risk repudiation by his own superiors. And he will have no one to turn to for guidance…

Britannia’s Spartan sees Dawlish drawn into fierce battles on sea and land. Daring and initiative have already brought him rapid advancement and he hungers for more. But is he at last out of his depth?

Below are the nine Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The Vega Expedition and the North-East Passage 1878-79 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 23, 2021

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 2: HMS Glatton

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 2

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 2

Henry Trollope

In Part1 of this article (Click here to read it if you missed it) we met the “carronade crazy” Royal Navy officer Henry Trollope (1756-1839). His career was a distinguished one – he rose to full Admiral – but his long-term reputation rests on two spectacular actions in which carronades played a decisive role. Part 1 describes these large-bore but short-range weapons, which represented cutting-edge technology from the 1780s onwards, and Trollope’s brilliant use of them when he commanded HMS Rainbow in the last years of the American War of Independence.

The gap between the American War – in which France, as usual, sided against Britain – and the next conflict Britain would fight with France, the Revolutionary War, was a short one, just a decade long. In this decade however the British government did what governments have done through history – once victory was gained it was assumed that no further conflict was likely in the near future and that economic advantage could be achieved by standing down armed forces, disposing of warships and running down stores. This was to offer what is now called a “peace dividend”. It was to prove an illusion once revolution erupted in France and launched more than two decades of warfare on a global scale. Britain’s new was began in early 1793 and by then large numbers of warships that had proved so essential in the earlier conflict had by now been disposed of. More ships were needed –and as soon as possible. New construction was immediately committed to but, until these vessels were completed and commissioned, stopgaps were essential.

East Indiaman Woodford by Samuel Atkis (1787-1808) (with acknowledgement to the WikiGallery.org)

East Indiaman Woodford by Samuel Atkis (1787-1808) (with acknowledgement to the WikiGallery.org)

One such stopgap measure was to purchase ten “East Indiamen” – stoutly built trading vessels in the service of the East India Company and well suited to long ocean voyages. Typical of these was HMS Glatton, a 1253-ton ship, pierced with gun ports like all of her kind and carrying defensive armament to protect her against Algerine corsairs off North Africa and other pirates in Eastern Seas. By the time she was requisitioned by the Royal Navy in 1795, she had already participated in the capture of a French brig, Le Franc, while part of a trading convoy. On being taken into the Navy, command of her was assigned to Captain Henry Trollope, who had the responsibility for arming and commissioning her, and getting her into service as soon as possible. Trollope, building on his previous experience, made maximum use of the latitude allowed him and he armed HMS Glatton entirely with carronades rather than with the usual mix of long guns. A total of twenty-eight 68-pounder carronades were mounted on the lower deck and twenty-eight 32-pounder carronades on the upper. All were on slides rather than trucks but the vessel’s gun ports were too small to allow training other than on the beam. Added to this was the fact that the deck layout did not allow mounting of bow-chasers or stern-chasers. Careful manoeuvering of the entire ship would therefore be needed to bring her massive firepower to bear.

East Indiaman – contemporary engraving

Classed as a fourth-rate, HMS Glatton was assigned to the North Sea Fleet, under Admiral Adam Duncan. On the 14th July 1795, she was directed to sail to join a squadron of two ships of the line and several frigates cruising off the Dutch coast, the Netherlands being by this stage a French satellite. In the early afternoon of the 16th, close to the Dutch naval base of Helevoetsluis, Trollope and HMS Glatton sighted a powerful enemy squadron. This consisted of consisted of six large frigates, a brig, and a cutter. One of these, as far as could be made out, mounted 50 guns, two 36, and the other three 28. Given these odds, Trollope might be forgiven for judging discretion to be the better part of valour. He banked however on the same advantage that had proved so decisive in his earlier action with HMS Rainbow – the surprise element and the devastating firepower of the carronades if the range could be closed. He therefore ordered HMS Glatton to be cleared for action and steered towards the enemy.

It was now late evening, though still light, when Trollope drew level with the third ship in the enemy’s line. That he was allowed to come so close is a mystery, as is the fact that the enemy was so rigidly attached to line tactics in the circumstances. Trollope hailed this third ship, and confirming that she was French, ordered her commander to strike his colours. Instead of doing so, the Frenchman not surprisingly responded with a broadside. HMS Glatton, at a separation of only thirty yards, unleashed her own broadside, one comparable to that of a ship of the line. The other enemy ships now – at last – manoeuvred to surround HMS Glatton, the two headmost vessels tacking about so that one placed herself alongside to windward, and the other on HMS Glatton’s bow, while the remaining ships engaged her on her lee-quarter and stern.

French frigate Incorruptible – one of Glatton’s opponents

French frigate Incorruptible – one of Glatton’s opponents

HMS Glatton’s awesome firepower was mitigated by the fact that her crew was insufficient to man her guns on both sides simultaneously. The solution was to divide each gun-crew into two gangs. One loaded and ran out the gun, leaving the most experienced hands to aim and fire it while they rushed across and loaded and ran out the gun on the opposite side. Fire was now continuous, the range on each side so close that HMS Glatton’s yard-arms were nearly touching those of the enemy. Her carronades were by now inflicting serious damage and the French commodore tried to decide the issue by having his lead ship attempt to drive Glatton on to a nearby shoal. By skilful manoeuvring, Trollope tacked to avoid this and while the French vessel was herself doing the same he managed to rake her. His own masts yards and sails were by now badly damaged and though further damage was inflicted on the enemy it proved impossible to manoeuvre effectively to bring his cannonades into play. The enemy vessels stood off as darkness fell and through the night Trollope’s crew was occupied in strengthening masts and yards, and in bending fresh sails. By daylight, Glatton was in a fit state to renew the action – and the light also revealed that the enemy squadron was now running for the protection of the port of Flushing. Trollope followed for two hours but as he had no hope of reinforcement, and as the wind was blowing on shore, he was compelled to haul off and steer for Yarmouth Roads, where he arrived on the 21st.

Trollope with the mortally wounded Marine Captain Henry Ludlow Strangeways on HMS Glatton

Trollope with the mortally wounded Marine Captain Henry Ludlow Strangeways on HMS Glatton

It was subsequently found that all the enemy ships had been badly damaged, one sinking in Flushing harbour after arrival. The largest, with which HMS Glatton was chiefly engaged, was the Brutus, a “74” 300 tons larger and cut down to some 50 guns, of which 46 were 24-pounders. Also present were the frigates Incorruptible, Magicienne and Républicaine. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the action was that although the French losses must have been heavy (though undetermined), Glatton’s casualties were two wounded only, one of whom, the captain of Marines, died subsequently.

Trollope’s achievement was immediately recognised as unprecedented. He had deliberately engaged six other powerful ships simultaneously, and had put them to flight. He was rewarded with a well-deserved knighthood. He was to retain command of HMS Glatton for three more years, still in the North Sea fleet, and one of his notable achievements was persuading her crew not to join the Nore mutiny in 1797. He went further – by threatening to unleash Glatton’s firepower on two other ships that were in open mutiny, he induced their crews to return to duty. Promoted to command of the “74” Russell, he was to participate in Duncan’s victory at Camperdown later the same year.

The Battle of Camperdown, painted by Philip de Loutherbourg (1740-812).

And Glatton? She was converted in due course the more conventional armament – her “carronades-only” surprise value could only be of limited duration – and she was to see extensive action in the North Sea, Baltic and the Mediterranean until being hulked for harbour service in 1814.

Britannia’s MissionThis volume of the Dawlish Chronicles deals with Indian Ocean slave-trade suppressionClick image above for details

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Click on the image to order as a paperback or Kindle. If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read at no extra cost.Click on any of the cover images below to join the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list and to receive six free short stories for downloading on your Kindle, computer or tablet..fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 2: HMS Glatton appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 16, 2021

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 1

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 1

Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 1

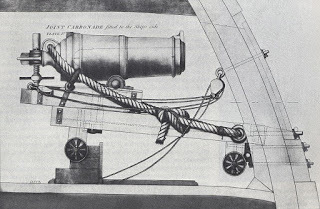

Carronade on slide mount

Carronades – large-calibre, short-range cannon throwing very heavy shot – were a game-changing weapon when introduced in the 1780s (Click here for the article “HMS Flora 1780: the Carronade’s arrival”). Their light weight allowed them to be mounted on smaller craft that would be incapable of carrying larger “long guns”, thereby giving such vessels an offensive capability wholly disproportionate to their size. They were to prove no less valuable on larger vessels, especially for raking the decks of enemy vessels at close quarters with grapeshot.

Henry Trollope

One notable British officer of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars period was to gain a reputation as “carronade crazy” and, though his career was to be a long and successful one, he is best remembered for two spectacular actions in which his use of these weapons proved decisive. Henty Trollope (1756-1839) had entered the Royal Navy at 14. In 1781, having seen extensive action in the American War of Independence, he achieved the coveted rank of “post captain” at the young age of 25. His first command was the frigate HMS Rainbow. Though the war was by then in its final stages, active hostilities between Britain and France were still in full swing and 1782 found Trollope on patrol off the northern coast of Brittany.

The classic frigate of the period – HMS Rainbow would have probably differed only in detail

The classic frigate of the period – HMS Rainbow would have probably differed only in detail

As Trollope commanded her, HMS Rainbow was an experiment – a 35-year old 44-gun frigate that had been re-armed entirely with carronades. She now carried a total of 48 of them – 20 68-pounders on her main-deck, 22 42-pounders on her upper deck, 4 32-pounders on her quarter-deck, and 2 32-pounders on her forecastle. This gave her a “weight of metal” – the total discharged in a single broadside – of 1238 pounds. This compared with a broadside weight of metal of only 318 pounds if she were to be armed as a conventional frigate mounting only long guns. It should also be noted that at the time the largest guns carried by line-of-battle ships were long 32-pounders. The disadvantage was however that Rainbow would have to come to very close range with an enemy before she could loosen her enormous firepower and during the approach she would be vulnerable to fire from conventional weapons. In a worst case, a skilful enemy commander might be able to manoeuvre nimbly so as to stay outside HMS Rainbow’s range and batter her into submission with long-range fire. In 1782 however, with the carronade still a novelty, and the possibility of any frigate being entirely armed with them was a remote one, her armament gave HMS Rainbow the potential for surprise.

Hébé’s sister Prosperine, seen here as HMS Amelia, following capture in 1785 in painting by John Christian Schetky (1778 – 1874)

On 4th September 1782, off the Isle du Bas, Rainbow sighted a French frigate which was escorting a small convoy from Saint-Malo to Brest. Trollope immediately ordered a chase. The enemy proved to be the Hébé and her armament was typical for a French or British frigate of the period – 28 18-pounders and 12 8-pounders. The French commander, the Chevalier de Vigney, could reasonably expect an evenly matched contest and – unwisely – allowed Trollope’s vessel to close. It was only when Rainbow opened fire with her bow-chasers, and when several large shots struck the Hébé, was it apparent that something unusual was involved.

Hébé’s sister Sibylle seen here as HMS Sibylle after capture by HMS Romney in 1794, as painted by Anton Schranz d. 1839

As Trollope’s prize, Hébé was purchased into the Royal Navy. Her hull-form was regarded as outstanding and she subsequently served as an inspiration for future British frigate designs. She retained her own name initially – as was the custom with captured warships – but she was renamed HMS Blonde in 1805, serving a further five years thereafter. Rainbow’s useful life was nearing an end and she was demoted to harbour service from 1784 until her disposal in 1802.

Trollope’s career was however only taking off and in 1795 he was to fight an even more remarkable action in which carronades were again to prove a critical factor. Part 2 of this article will tell about it – so watch out!

Start the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventures with the earliest chronologically:Britannia’s Innocent For more details regarding purchase in paperback or Kindle format, click below Note that Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read at no extra chargeFor amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to nine volumes, and counting, Click on the banner below for details.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Captain Trollope and the Carronades – Part 1 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 19, 2021

France’s Farfadet Submarine Disaster 1905

France’s Farfadet Submarine Disaster 1905

France’s Farfadet Submarine Disaster 1905Courage of the highest order was demanded of the officers and men of the navies that first employed submarines in the early twentieth centuries. Designs were still experimental and operating experience limited, so that every dive was an adventure. Accidents were frequent – and usually fatal when they did occur – and progress was achieved by learning very hard lessons.

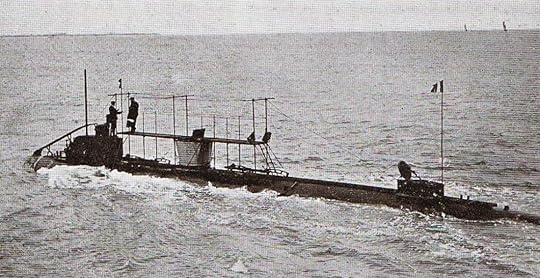

The French navy was one of the first to commit to large-scale submarine construction. It looked to the new weapon, as it had looked to torpedo boats two decades before, as a cheap method of compensating for relative weakness in battleship numbers by comparison with potential rivals. At this stage submarines were primarily seen as suited to coastal and port-defence and the second –and so-far largest – design class, the four Farfadet units, launched between 1901 and 1903 were intended for this purpose.

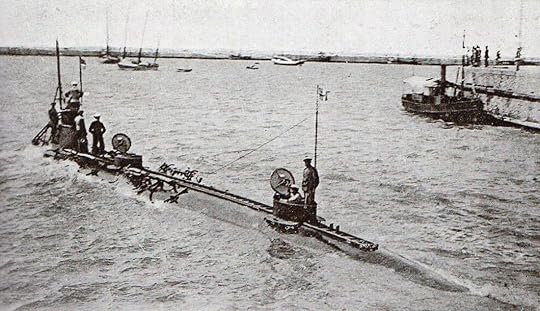

The Farfadet in service

The Farfadet in service

135-ft. long and of 185/ 202 tons (surface/submerged), units of the Farfadet class were propelled by a single electric motor driving a variable-pitch propeller. The latter was an innovative item that dispensed with the need to provide reversing capability for the motor. Range, determined by the batteries that had to be charged at the operating base, was limited to 115 miles surfaced and 28 submerged, and the maximum speeds attainable were 6.1 knots on the surface and 4.3 knots when submerged. Small as they were, these units packed a potentially powerful punch – four 18-inch torpedoes carried on external drop collars. The potency was proved when one unit of the class, the Korrigan, succeeded in hitting the cruiser Tempete with a practice torpedo while remaining unobserved – possibly the first time a target had been hit by a torpedo launched by a submarine. This considerable feat demanded the Korrigan and her sixteen-man crew remaining submerged for some twelve hours, somewhat of a record.

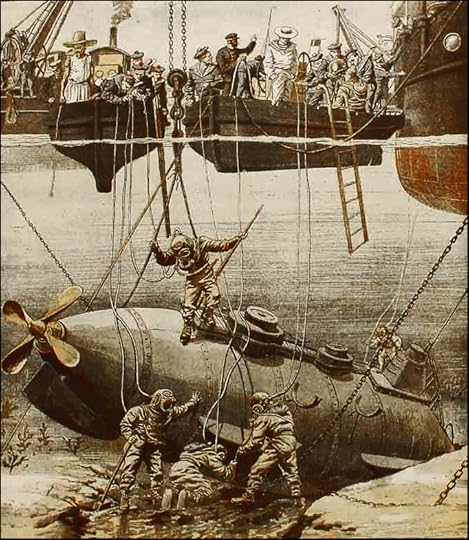

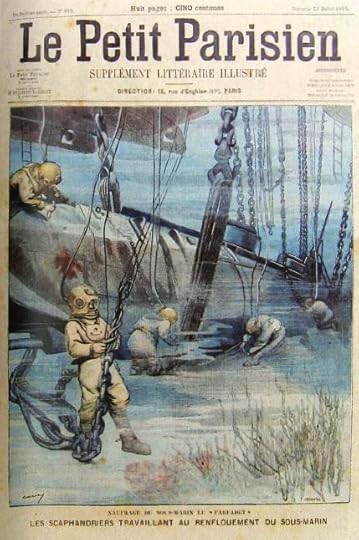

A contemporary artist’s impression of salvage operations. Shallowness of water is exaggerated

Both Korrigan and Farfadet were towed from La Rochelle, on the French Atlantic coast to the naval base at Bizerte, in Tunisia, in 1904 to provide port-defence. It was here that disaster was to overcome the Farfadet on July 6th of the following year when the vessel was undertaking diving exercises some 500 yards from the arsenal. Commander Cyprien Ratier ordered water to be admitted to the ballast tanks and the craft began to settle very quickly – too quickly, for the hatch was not closed properly. (It will be seen from the photographs that the hatches were a point of vulnerability as they were very close to the waterline when surfaced and there was no tower as such). Ratier, his mate and the quartermaster struggled unsuccessfully to close the hatch. Large volumes of water where now cascading into the boat’s interior and Ratier and his two assistants were blasted out through the hatch by the escaping air. The Farfadet sank, head-foremost, and buried her bows in the mud. Fourteen men had gone down with her.

Immense public interest

in the salvage

The stricken craft was lying in approximately thirty feet of water and some salvage equipment was immediately available at the base. There were obviously still men alive inside, for they were hammering on the hull. By the following morning divers had managed to get four steel hawsers passed around the hull and a floating crane managed to lift it in the early afternoon so as to lash it to a pontoon. Sufficient of the hull had been exposed for air-valves to be accessed and air passed in to the survivors. It was now attempted to move the craft into shallow water, so as to ground her. The process was a slow one and in the early hours of the following morning the hawsers parted and the Farfadet dropped again. Further efforts failed to lift her before the victims trapped inside died. No further sounds were heard after July 8th, two days after the disaster. (One notices dreadful similarities to the HMS Thetis disaster in Liverpool Bay in 1939, when the stern of the sunken submarine had been raised above the surface).

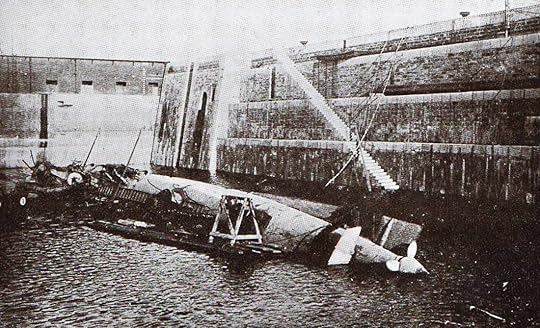

Salvage efforts continued, a floating dock being used to lift the Farfadet – once again, the role of divers would have been crucial in passing hawsers under, and around, the hull. On July 9th, the Minister of Marine, Gaston Thomson, arrived from Paris to observe operations. On July 15th, the floating dock and the submarine suspended underneath were towed into a dry dock. The floating dock lowered the Farfadet, was then removed, and the dry dock was pumped out to expose the vessel.

The Farfadet – recovered and lying on her side in the dry dock.

The Farfadet – recovered and lying on her side in the dry dock.

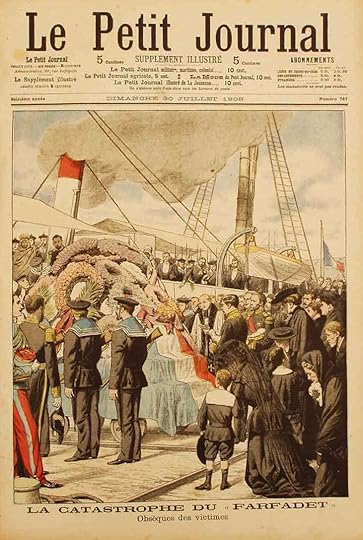

Repatriating the bodies