Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 10

June 3, 2022

HMS Natal & SS Persia Losses 1915

It was remarkable how little attention waspaid in the media, in popular memory or in large-scale centenary-commemorations in 2014-18 to the events of World War 1 at sea, other than the Battle of Jutland. And yet, throughout the war, a brutal attrition of human life occurred at sea, where the mine and the submarine were proving themselves more deadly than anticipated. Magazine explosions also took their toll. Terrible examples of tragedies were occasioned both by accident and by enemy action in what should have been a season of goodwill, the Christmas to New Year period of 1915. These included the sinking of the Royal Navy’s armoured cruiser, HMS Natal, and the liner SS Persia. There were many other vessels sunk also, involving horrific losses that are today largely forgotten except by descendants of the victims.

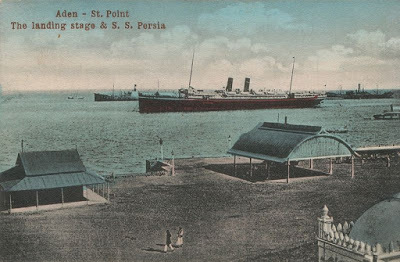

SS Persia – a victim oblivious of her approaching fate

At least 27 merchant and naval ships were lost to torpedoes and mines during the eight days of December 24th to 31st. A small but vicious naval conflict, the Battle of Durazzo, matched British, French and Italian naval forces against units of the Austro-Hungarian fleet off Albania with losses on both sides. Nor was enemy action alone a danger – in this era, when large numbers of sailing craft were still in use, bad weather represented a major threat. Approximately a dozen of such craft were wrecked in this short time and some brief summaries of their fates could have used wording identical to that for similar losses at any time in the previous two centuries. One such example was the three-masted Danish schooner Dana, “ driven ashore at Craster, Northumberland, United Kingdom, and wrecked.”

The most spectacular losses involved two British units, one naval, one civilian, which were lost within hours of each other on December 30th. Together, these two tragedies accounted for some 760 deaths.

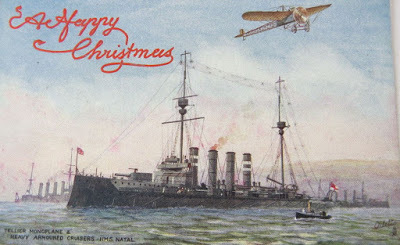

HMS Natal seen – ironically – on a Christmas card (perhaps pre-war, judging by the aircraft)

HMS Natal was among the last British armoured cruisers to be built before the type was superseded by the new (and equally ill-starred) battlecruiser concept. Launched in 1905, she was one of a four-ship Warrior class, three of which were to be lost in World War 1. These vessels were as large as many contemporary battleships, displacing 13,550-tons and 505-feet long. With 23,000-hp installed power they were capable of a top speed of 23 knots. Their armament was heavy for the type – six 9.2-inch and four 7.5-inch guns, plus many smaller weapons, as well as three 18-inch torpedo tubes. Their major advantage over almost all previous armoured cruisers was that all ten main weapons were carried in turrets rather than in casemates, allowing operation in rough sea conditions. Given the size of these ships, it is not surprising that each carried a crew of up to 790.

Individual gun-turrets on HMS Natal’s starboard flank

During 1915 HMS Natal was attached to the Royal Navy’s “Grand Fleet”, which was based at Scapa Flow, the vast semi-protected anchorage in the Orkney Islands, north-east of the Scottish mainland. The patrols she undertook in the North Sea were uneventful and, like the other vessels of the Grand Fleet, HMS Natal would have spent much of her time at her moorings, waiting for news of the German fleet venturing out from its own bases. In December 1915 however she moved south to the base in the Cromarty Firth, on the Scottish east coast, and at Christmas approximately a quarter of her crew were allowed ashore on leave. On December 30th, as a gesture of goodwill, HMS Natal’s captain, Erik Black, invited civilians aboard for a film-show – then still a novelty. These invitees included family members of the crew as well as personnel from a hospital ship moored nearby, HMHS Drina. In the event – and luckily – many of them could not attend and only eight civilians came on board, seven of them women and three of them children. The party had no sooner started than a succession of explosions commenced which were to rip the vessel apart within minutes.

HMS Natal’s wreckage remained visible for many years

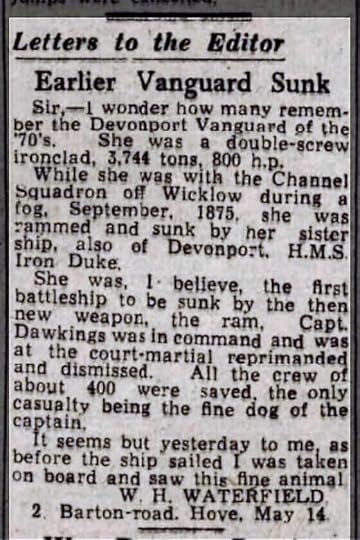

Boats rushed to the scene from nearby ships and some 170 survivors were dragged from the freezing water. Deaths, including the captain’s, were announced officially soon afterwards as 390, though the number has been estimated as being as high as 421, the increase perhaps due to later deaths occasioned by exposure. The immediate fear was that the anchorage had been penetrated by a German U-boat which had either fired a torpedo or dropped a mine, but evidence soon indicated spontaneous combustion of unstable cordite propellant charges stored in the after magazines. Such instability caused losses in several of the navies of the period, and the Royal Navy was to lose the pre-dreadnought HMS Bulwark to this in 1914 (750 dead) as well as the modern dreadnought HMS Vanguard in 1917 (804 dead).

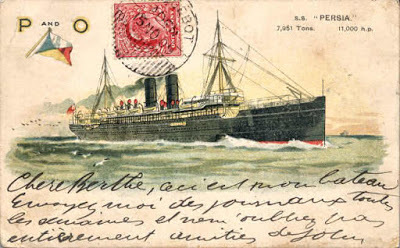

SS Persia, as seen on a peace-time postcard

“The Spirit of Ecstasy”

While HMS Natal’s tragedy was unfolding another, almost as dreadful, was taking place in the Eastern Mediterranean. SS Persia was an 8000-ton passenger liner which had been built in 1900. Still in civilian service in 1915, on December 30th she was en-route to India and carrying not only passengers but a large amount of gold and jewels belonging to the Jagatjit Singh, maharajah of the princely state of Kapurthala, in the Punjab, who had left the ship at Marseilles. At midday, just south of Crete, the Persia was struck by a torpedo fired by the German submarine U-38, which has sunk another ship, the freighter Clan Macfarlane, some hours earlier at a cost of 52 lives. U-38 was commanded by Kapitänleutnant Max Valentiner (1883 –1949), who was to prove himself one of the most outstanding – and ruthless – U-boat commanders of the war. The SS Persia sank in less than ten minutes, taking 343 of the 519 people on board with her. Among the survivors was the British motoring pioneer Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, though his secretary, Eleanor Thornton, drowned. This lady was allegedly the model for the “Spirit of Ecstasy” mascot that is still featured above the radiators of Rolls-Royce cars.

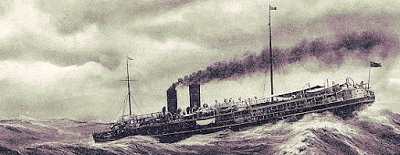

SS Persia’s sinking – contemporary view

The SS Persia’s sinking caused outrage since it was without warning and violated the so-called “Arabic Pledge” that Germany had given in August 1915 and which instructed U-boat commanders not to torpedo passenger ships without notice and without allowing passengers and crew to enter “a place of safety” – i.e. the ship’s boats. Kapitänleutnant Valentiner of the U-38 was to be accused of a total of fifteen generally similar incidents involving civilian shipping (out of a total of 34 ships sunk) and after the war the Allies demanded his extradition as a war-criminal. He got around this by temporarily changing his name and hiding, though he later followed a business career in his own name. He was to serve again in the Second World War, in support of the U-boat campaign, though not going to sea. He died in 1949.

There is a sad addendum to the loss of HMS Natal. HMHS Drina, the hospital ship moored close to her, was reconverted to freighter service in 1916. The following year, as she returned from a voyage to South America with vital supplies, she was sunk off the south-west coast of Wales by a U-boat. Fifteen lives were lost.

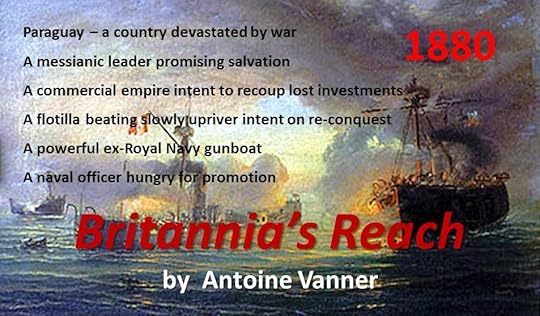

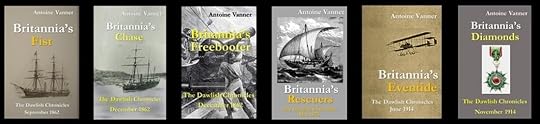

Naval fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamSince its original publication, the Dawlish Chronicles novel Britannia’s Reach has consistently scored 5-star Amazon reviewsFor details:For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Natal & SS Persia Losses 1915 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 26, 2022

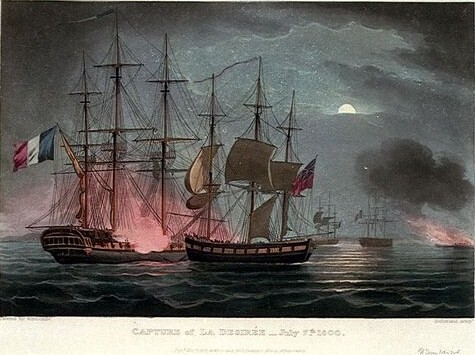

HMS Dart & Désirée 1800

One of the last fireship attacks:HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800

One of the last fireship attacks:HMS Dart & Désirée, 1800For many centuries fireships were to be some of the most dramatic and devastating of all naval weapons, albeit that they were difficult to deploy and dangerous to their crews. The most effective and history-changing use ever of such ships was when they were used to attack the Spanish Armada at anchor off Gravelines in 1588. The effect was out of all proportion to the damage they did – or could do – as they panicked the Spanish captains into cutting their cables and running out into the North Sea. Adverse weather made a return via the English Channel impossible, ending hopes of landing a Spanish army on British soil and driving the majority of the ships to destruction on the Scottish and Irish coasts. Creasey, the historian, was to number this defeat among what he termed “The 15 Decisive Battles of the World”. One of the last deployments of fireships by the Royal Navy was to take place in July 1800 and a key role in the action would be played by a sloop-of-war of innovative design, HMS Dart.

Spanish Armada under fireship attack by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740 – 1812)

Spanish Armada under fireship attack by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740 – 1812)

Close inshore action against French shipping by aggressive British naval officers was to be a constant feature of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and the July 1800 attack, on the heavily defended French base at Dunkirk, was to be one of the most daring. The inspiration for the raid came from the noted frigate captain, Henry Inman (1762 – 1809), then in command of the 32-gun Andromeda, and the objective was destruction of four French frigates anchored in the Dunkirk roads – Poursuivante, Incorruptible, Carmagnole and Désirée. They lay under the protection of powerful coastal gun-batteries, the anchorage was patrolled by rowed gunboats and treacherous shoals and shallows made approach difficult. Fireships were to be a key feature of the operation and four obsolete brigs were prepared for such duty – Wasp, Falcon, Comet and Rosario.

Under Inman’s overall command, the squadron – what might now be termed a task-force – consisted of the frigates Andromeda and Nemesis, the brigs Boxer and Biter, the four fireships, two hired cutters, Kent and Ann and a hired lugger, Vigilant. There was in addition a most unusual vessel, HMS Dart, classed as a sloop since nobody knew what else to call her.

Samuel Bentham

HMS Dart, and her sister HMS Arrow, were experimental vessels, never indeed to be repeated. They were the brain-child of Sir Samuel Bentham (1757 – 1831) – brother of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. At this stage in his remarkable career as an engineer and naval architect, in Britain, Russia and China, Bentham held the position of Inspector General of Naval Works. Designed to operate in coastal waters, these two vessels were virtually double-ended and featured a large breadth-to-length ratio, structural bulkheads, and sliding keels. Of 150 tons and a mere 80 feet long overall, they packed an enormous punch for their size, all guns being carronades, (Click for more on these weapons) HMS Dart and HMS Arrow carried twenty-four 32-pounders on their upper deck, two 32-pounders on their forecastle and another two on each quarterdeck. HMS Dart’s command had been assumed in 1799 by Commander Patrick Campbell (1773 –1841), who would later rise to flag rank and in this year, and the next, she would see active and successful service in Dutch coastal waters.

Bad weather delayed the start of the operation but it was finally launched on the night of 7th July, the vessels in line ahead with Campbell and HMS Dart – with her massive fire-power – leading. His objective was to attack the innermost French frigate while the fireships were to grapple the other three and so destroy them. HMS Dart drew ahead of the other British vessels and, as the night was dark, managed to come close enough by midnight for the nearest French vessel to challenge her. Campbell answered that his ship was French, from Bordeaux, and this appears to have been accepted. HMS Dart, unsuspected, moved on unhindered past the first two frigates until another French challenge asked what convoy was coming in her wake. The answer “Je ne sais pas” – “I don’t know” – was, quite amazingly, accepted. Suspicions were however aroused on the third French ship, which now opened fire. As she ran past her, HMS Dart unleashed a smashing broadside. Her carronades had been double-shotted with roundshot and grapeshot – almost 900 pounds of metal per broadside – and the effect was devastating.

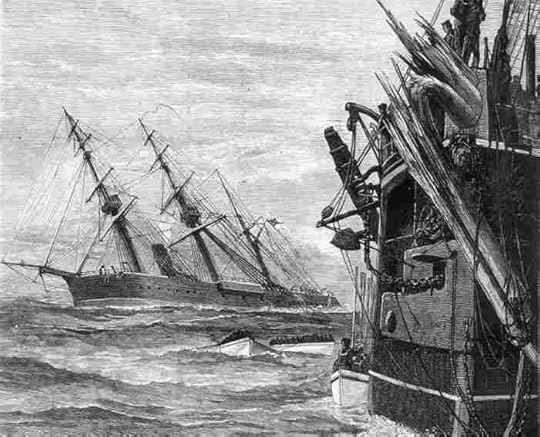

HMS Dart (r) crashes into Désirée – note that she is virtually double-ended

HMS Dart (r) crashes into Désirée – note that she is virtually double-ended

Engraving after a painting by Thomas Whitcombe (1763-1824)

HMS Dart drove on to crash into her target, the fourth and innermost frigate, the Désirée. Her bowsprit ran into the foremast’s shrouds. Led by HMS Dart’s first lieutenant, James M’Dermeit, fifty men swarmed across. The inevitable man-to-man fighting ensued and M’Dermeit, wounded, called for reinforcement. Campbell managed to drag HMS Dart fully alongside so as to allow a second boarding party to get across. This decided the issue and the French were subdued and struck their colours. Captain Inman had been following in the lugger Vigilant, crewed by thirty volunteers from Andromeda, and under intense fire, came alongside Désirée, boarded, cut her cable and took her out to sea. The struggle had been vicious but one-sided – of Désirée’s 330-man crew over 100 were killed or wounded, with only a single midshipman surviving from her officers. HMS Dart, by comparison, suffered one man killed and eleven wounded – surprise had paid off.

The fireships had meanwhile launched their attack. Packed with combustible material and gunpowder, set ablaze by their volunteer crews, they were steered towards the remaining three French frigates while the Dart and the two brigs, Boxer and Biter, provided covering fire. Pulling boats accompanied them to take off the crews – the officers commanding the fireships remained on board until they were all but enveloped by flames. The French reacted as the Spanish had done over two centuries previously – they cut their cables and sailed under fire past Dart, Boxer and Biter into shoal-waters familiar to them where the British could not follow. Unmanned now, the fireships drifted until they exploded without doing any damage to the enemy. French rowed-gunboats came out from Dunkirk to join in the fray but were repulsed by the hired cutters.

Incorruptible, sister of the Désirée , of the same Romaine-class

Incorruptible, sister of the Désirée , of the same Romaine-class

She was one of the three French frigates to escape capture at Dunkirk

Recognising that the three surviving French frigates were now unreachable, Inman ordered withdrawal. With no room for prisoners and with large numbers of French wounded, he sent his captives back into Dunkirk. Success had been partial but the moral effect of the attack must have been considerable. Campbell of HMS Dart was deservedly promoted to post captain and given command of the sixth-rate HMS Ariadne. The Désirée was commissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Désirée under Inman’s command. She was to see much active service thereafter, including participation in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. Inman’s own subsequent career was also active but poor health led to his early death in India in 1809. It is notable that prize money was paid for Désirée’s capture but head money, an award made for enemy servicemen killed, wounded or captured, was not paid, probably because of the return of the French prisoners.

And what became of the innovative HMS Dart and her sister Arrow? Both were to have further active careers. Perhaps we’ll meet them on a future blog!

Naval Fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Dart & Désirée 1800 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 19, 2022

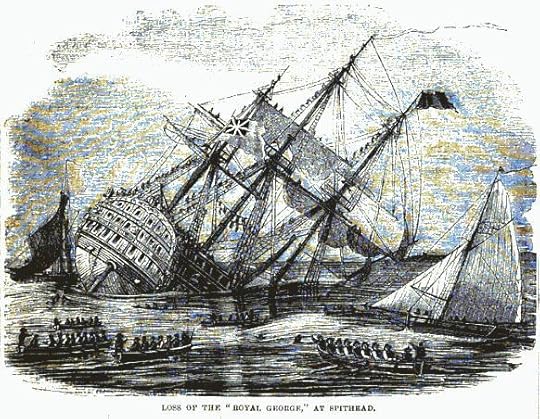

The HMS Royal George Disaster 1782

The loss of HMS Royal George 1782

The loss of HMS Royal George 1782The disaster that overcame the first-rate ship of the line HMS Royal George in 1782, while anchored in calm water in sight of shore, was to have as strong an impact on the contemporary public mind as the loss of the RMS Titanic was to have one hundred and thirty years later. The tragedy was all the more terrible for the fact that it would have been avoidable if the simplest of precautions had been taken – and without them over 900 men and women were to die.

When launched in 1756 the Royal George was the largest warship in the world at some 2000 tons, a length of 180 feet and armed with over a hundred guns. The 28 42-pounders and equal number of 24-pounders she carried gave her massive ship-smashing power. She was to see significant action in the Seven Years War, then commencing, and was to serve during it as flagship for two of the Royal Navy’s greatest names, Admirals Anson and Hawke. It was from her that Hawke was to command the fleet that inflicted such a crushing defeat on the French at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759, in the course of which she sank the French ship Superbe. She was to render equally valuable service during the American War of Independence, operating against the French and Spanish fleets in the Eastern Atlantic and participating in the “First Relief” of the Siege of Gibraltar in 1780 when troop reinforcements and supplies were landed on The Rock. Thus was not the end of the siege however and it was destined to drag on for another three years.

When launched in 1756 the Royal George was the largest warship in the world at some 2000 tons, a length of 180 feet and armed with over a hundred guns. The 28 42-pounders and equal number of 24-pounders she carried gave her massive ship-smashing power. She was to see significant action in the Seven Years War, then commencing, and was to serve during it as flagship for two of the Royal Navy’s greatest names, Admirals Anson and Hawke. It was from her that Hawke was to command the fleet that inflicted such a crushing defeat on the French at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759, in the course of which she sank the French ship Superbe. She was to render equally valuable service during the American War of Independence, operating against the French and Spanish fleets in the Eastern Atlantic and participating in the “First Relief” of the Siege of Gibraltar in 1780 when troop reinforcements and supplies were landed on The Rock. Thus was not the end of the siege however and it was destined to drag on for another three years.

First Relief of Gibraltar, 1780 – painting by Dominic Serres (1722 – 1793)

The Royal George returned to Britain for a major refit in 1780 and saw service with the Channel Fleet thereafter. By August 1782, with the siege still in progress, she was to join a new expedition to relieve Gibraltar as flagship of Admiral Richard Kempenfelt (1781-1782, see portrait on left). She was moored off Spithead – the Royal Navy’s Portsmouth anchorage – and was taking on supplies on August 28th when, during deck washing, the ship’s carpenter discovered that the pipe used to draw clean seawater on board was defective. The inlet of this pipe, on the starboard side, was some three feet below the waterline and to access it would demand heeling the ship over to expose it. This was done by running out the guns on the ship’s port side as far as they could go and drawing in the starboard guns, securing them amidships. This action not only exposed the mouth of the pipe to starboard but brought the sills of the open gun-ports on the port side within inches of the water’s surface.

The Royal George returned to Britain for a major refit in 1780 and saw service with the Channel Fleet thereafter. By August 1782, with the siege still in progress, she was to join a new expedition to relieve Gibraltar as flagship of Admiral Richard Kempenfelt (1781-1782, see portrait on left). She was moored off Spithead – the Royal Navy’s Portsmouth anchorage – and was taking on supplies on August 28th when, during deck washing, the ship’s carpenter discovered that the pipe used to draw clean seawater on board was defective. The inlet of this pipe, on the starboard side, was some three feet below the waterline and to access it would demand heeling the ship over to expose it. This was done by running out the guns on the ship’s port side as far as they could go and drawing in the starboard guns, securing them amidships. This action not only exposed the mouth of the pipe to starboard but brought the sills of the open gun-ports on the port side within inches of the water’s surface.

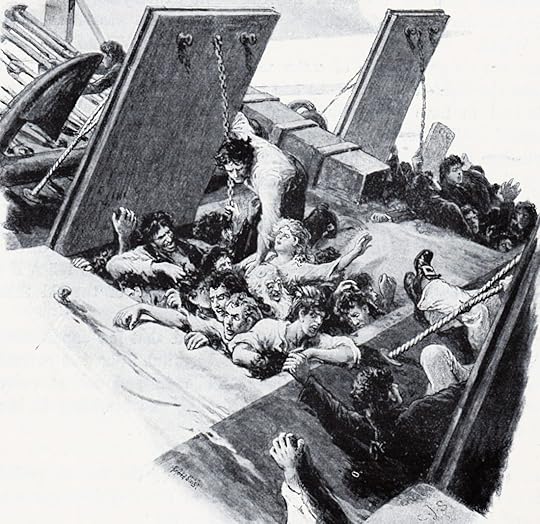

Though the exact number could never be confirmed it was estimated that up to 1200 people were on board, including some 300 women and 60 children. Many were undoubtedly family members taking leave of their menfolk but contemporary accounts also refer – delicately – to ladies “who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war”. A number of traders and pedlars also appear to have been present. One suspects that the scene below decks was a bizarre mix of the domestic, the poignant and the debauched, brief moments of happiness, sadness and orgiastic pleasure snatched in brief hard lives.

Though the exact number could never be confirmed it was estimated that up to 1200 people were on board, including some 300 women and 60 children. Many were undoubtedly family members taking leave of their menfolk but contemporary accounts also refer – delicately – to ladies “who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war”. A number of traders and pedlars also appear to have been present. One suspects that the scene below decks was a bizarre mix of the domestic, the poignant and the debauched, brief moments of happiness, sadness and orgiastic pleasure snatched in brief hard lives.

In mid-morning a slight breeze began to ruffle the water and it lapped occasionally over the port-sills on the port side. This appeared to drive up mice from the lower part of the ship and they began to be hunted as a game. The wind was freshening further and yet more water began to spill in, but nobody had yet perceived the situation as dangerous. A 50-ton sloop, the Lark, had come alongside with supplies of rum and she was secured to the port side to allow transfer of kegs.

Royal George starts her fatal roll (Victorian-era illustration)

It was the carpenter who first awoke to the hazard and he went to the nineteen-year old lieutenant of the watch, Philip Charles Durham (1763-1845), to request an order to right the ship. He was ignored at first attempt but at the second Durham told him “If you can manage the ship better than I can, you had better take the command.” Only when the ship heeled lurched further did the lieutenant order the drummer to beat to “right ship”. It was too late – a gust of wind heeled her still further and many of the starboard guns appear to have broken loose and rolled to port. Water was now pouring in through every gunport. The huge ship rolled on her side until her masts lay flat on the water, the mainmast bearing down on the sloop Lark alongside. HMS Royal George now sank like a stone, taking the sloop with her.

Contemporary view – HMS Royal George sinks close to the rest of the fleet

Admiral Kempenfelt was being shaved in his quarters as the ship rolled but the movement jammed the doors and he could not be got out. Hundreds of others were equally unlucky and the majority of 255 saved were already on deck. These were to save themselves by running up the rigging, while only about 70 were able to scramble out from below through the gunports. The presence of so many other ships in the anchorage meant that rescue boats were quickly on the scene but this was little help for the wretches trapped below deck.

The scramble through the open gunports (Victorian-era illustration)

One survivor, named Ingram, managed to get out through a port and looking back saw the opening “as full of heads as it could cram, all trying to get out.” He went on “I caught hold of the best bower anchor, which was just above me, to prevent falling back into the porthole and, seizing hold of a woman who was trying to get out of the same porthole I dragged her out.” He was sucked down with the vessel but rose clear to the surface and swam to a block floating near. Using this to support him he saw the Admiral’s baker in the shrouds of the mizzen-topmast, which was just above water, and behind him, still floating, the woman he had pulled free. With the baker’s help he managed to catch her and secure her to the rigging. A rescue boat took her to HMS Victory – Nelson’s future flagship – and she appears to have survived. Another survivor was a child who was playing on deck with a sheep as the vessel rolled and as he spilled into the water he managed to keep hold of the animal’s fleece. It swam about, supporting him, until a boat reached them. The Royal George’s captain was another survivor, but the carpenter drowned.

The final roll – note the figures in the rigging

(incorrect depiction – HMS Royal George rolled to port!)

The final death toll was estimated to be over 900, including all but a few of the women and children. A few days after the ship sank bodies started to come up. It is a sad commentary on human nature that many of the watermen who made their living by ferrying families and traders to and from the ships stripped the bodies of buckles, money and watches. One witness wrote of these bodies “towed into Portsmouth harbour in their mutilated condition, in the same manner as rafts of floating timber, and promiscuously (for particularity was scarcely possible) put them into carts, which conveyed them to their final sleeping place in an excavation prepared for them in Kingston churchyard”.

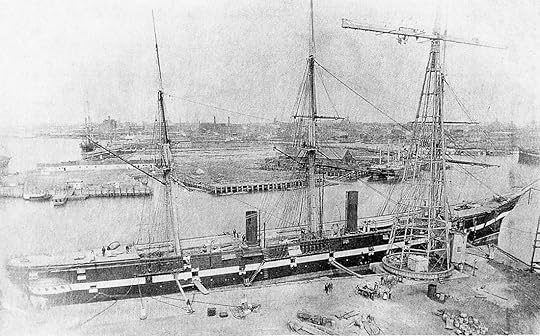

The Royal George’s mast-tops

The Royal George had sunk in relatively shallow water and she righted herself of her own accord so that the tops of her masts were still visible seventeen years later. All attempts to salvage her failed until the 1840s, when the wreck was blown apart with gunpowder charges and advances in diving equipment allowed recovery of guns and equipment. Her surviving timbers were raised, much of the wood being sold as relics.

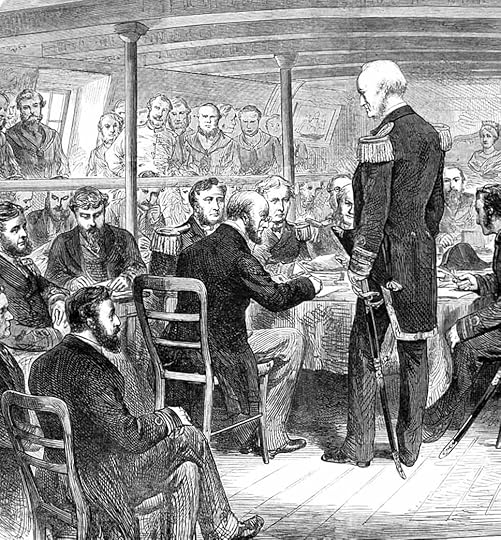

The inevitable court-martial in the aftermath of the sinking acquitted the officers and crew of responsibility and blamed the accident on the “general state of decay of her timbers”, suggesting that part of the frame of the ship gave way under the stress of the heel. One of the few survivors was the man perhaps most responsible for the loss, Lieutenant Philip Charles Durham, was a survivor (see at left in 1820). He was to have a very active further career throughout the Napoleonic wars, once being reprimanded for being “over zealous”. For some time he commanded HMS Anson, the largest frigate in the Royal Navy and he was to command HMS Defiance at Trafalgar. He acted as a pall-bearer at Nelson’s funeral. He was a very colourful – indeed controversial – figure both ashore and afloat and he ended as a full admiral, dying in 1845 at the age of 81.

The inevitable court-martial in the aftermath of the sinking acquitted the officers and crew of responsibility and blamed the accident on the “general state of decay of her timbers”, suggesting that part of the frame of the ship gave way under the stress of the heel. One of the few survivors was the man perhaps most responsible for the loss, Lieutenant Philip Charles Durham, was a survivor (see at left in 1820). He was to have a very active further career throughout the Napoleonic wars, once being reprimanded for being “over zealous”. For some time he commanded HMS Anson, the largest frigate in the Royal Navy and he was to command HMS Defiance at Trafalgar. He acted as a pall-bearer at Nelson’s funeral. He was a very colourful – indeed controversial – figure both ashore and afloat and he ended as a full admiral, dying in 1845 at the age of 81.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post The HMS Royal George Disaster 1782 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 22, 2022

HMS Thunderer 1879: end of RN muzzle-loaders

HMS Thunderer 1879: the end of muzzle-loaders in the Royal Navy

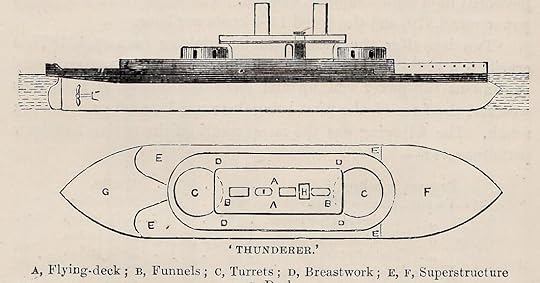

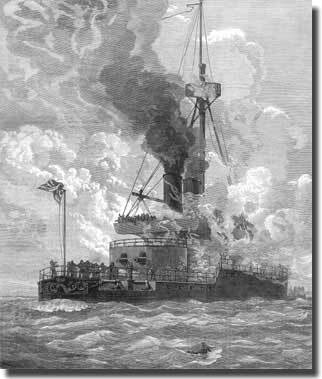

HMS Thunderer 1879: the end of muzzle-loaders in the Royal NavyThree ships of the Royal Navy in the 1870s, HMS Devastation, her close sister HMS Thunderer and her slightly larger sister HMS Dreadnought, can be fairly regarded as the models for subsequent mainstream battleship layout and development.

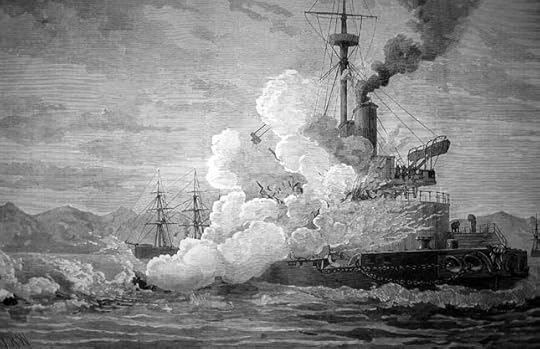

HMS Devastation, HMS Thunderer’s close sister, firing a salute

These ships were the first mastless battleships, armed with four 12-inch guns in rotating turrets and with a central superstructure layout. Armoured with 12” of iron from end to end, they were of 6000 tons on a length of 285 feet. Their hydraulic turret machinery and twin screw propulsion put them in the forefront of mechanical design and their coal bunkerage provided a range sufficient – in theory at least – to cross the Atlantic.

HMS Thunderer’s layout – turrets fore and aft, superstructure amidships

These vessels had however two serious weaknesses. One was irredeemable – that low freeboard ensured that even in relatively calm seas the foredeck was awash, thereby limiting fighting ability.

HMS Thunderer, her decks awash, in a heavy sea late in her career

The second weakness – the retention of muzzle-loading main armament – was one that could be recovered from, but not before a ghastly accident emphasised the need for change. During the 1860s the Royal Navy had made trials of breech-loading guns, but after a number of failures – mainly resulting from metallurgical problems – there was a reversion to muzzle-loaders, which had none of the complications of machining sealing and easily operating breech closures. Armstrongs, the great British gun-maker, did however persist with development and by the late 1870s much more reliable designs were to become available. In the meantime the Royal Navy relied on ever-larger muzzle loaders, culminating in the 80-ton, 16” calibre weapons mounted in HMS Inflexible (completed 1881). This was made possible by the use of hydraulic power for handling, loading and ramming these guns with their enormously heavy powder charges and shot. These weapons had remarkable strength, as shown in experiments with a 9-inch gun In 1869, the central tube splitting only when the 1,008th round was fired. The metal yielded gradually, and the strength of the outer jacket was thoroughly proved by firing a further 41 forty-one rounds after the barrel had split, and still the exterior remained perfectly sound.

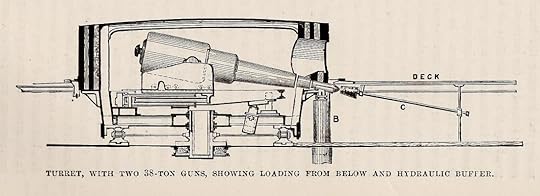

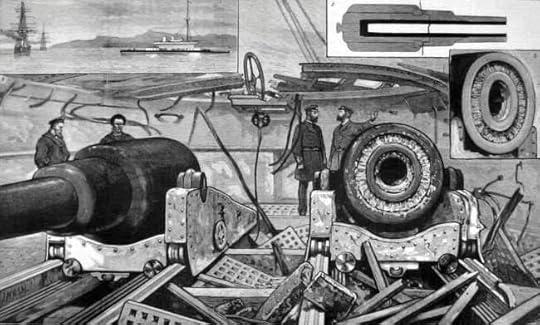

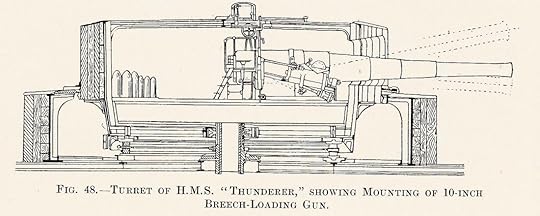

In the case of HMS Thunderer and her sisters, the guns were of 12” calibre and 38 tons weight. Mounted in turrets fore and aft they were run out for firing but were thereafter run back in again, and the muzzles depressed so that fresh projectiles could be loaded – the illustration below shows the process.

HMS Thunderer’s 12″ muzzle-loaders depressed for reloading

HMS Thunderer’s 12″ muzzle-loaders depressed for reloading

HMS Thunderer’s career was to be marked by two serious accidents. The first was not gunnery-related and involved a boiler explosion in July 1876 as she proceeded from Portsmouth Harbour to Stokes Bay to carry out a full power trial. This killed 15 people instantly, including her captain who was in the boiler room at the time, and injured around 70 others, of whom 30 later died. The reason for the explosion was that the pressure gauge was broken and the safety valves had seized through corrosion. The boiler explosion signalled the end of box boilers in favour of the Scotch cylindrical type, and it led directly to the writing of the first official RN Steam Manual in 1879. One also imagines that there was increased attention thereafter to the inspection and testing of safety valves!

[image error] HMS Thunderer enveloped in smoke and steam as a boiler explodes, July 1876

The second accident happened when HMS Thunderer, attached to the Mediterranean Fleet, was exercising in the Sea of Marmara on January 2nd, 1879. One of the 38-ton 12” guns mounted in the forward turret burst, killing two officers and eight men, besides wounding several others.

12″ gun explodes in HMS Thunderer’s forward turret, January 1879

12″ gun explodes in HMS Thunderer’s forward turret, January 1879

In view of the implications of the accident – the possibility that a class of weapon that armed the navy’s most powerful ships was fatally defective – the Admiralty appointed a commission of officers and scientific experts by to investigate its causes. This commission decided that the accident had been the result of a deplorable error in loading discipline, made worse by the inherent nature of the loading process and that on the day the gun had been fired when loaded with two complete rounds of powder and projectile.

The aftermath of the explosion – damage inside the turret

During the firing exercise it was intended to fire the two guns simultaneously, both being loaded with a battering charge of 110 lb. of powder and a Palliser projectile 800 lb. in weight. One gun, however, missed fire, although nobody was apparently aware of the fact – the concussion and the smoke made by the discharge of one gun was so great that it was considered difficult for anyone was on the look-out to tell that they were not due to both guns. The crews were drilled to run their guns in directly they fired, so as to be in readiness for reloading and, not observing that one of the guns had not gone off, they proceeded to run in. Both guns were reloaded through the muzzle, by the hydraulic system, with the result that the weapon with the double charge burst when the next round was fired.

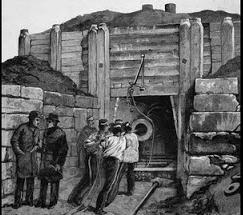

Surviving 12″ from turret in test cell at Woolwich Arsenal

Surviving 12″ from turret in test cell at Woolwich Arsenal

When the Admiralty received the report of the commission they determined, “in order that no question should arise in the future as to the correctness of the conclusions which the committee had arrived at”, to have the surviving gun brought back to Britain and subjected to trials, with a view of ascertaining under what other conditions it would burst. These tests were conducted at Woolwich Arsenal, the gun being enclosed in a protective bunker or “cell” to avoid further risk to life. After a series of experiments however, when every suggestion had been tried without injuring the gun, it was double loaded, just as the commission had reported that in their opinion the burst gun had been. When the smoke cleared away from the ceIl it was found that the gun had burst like its former companion, and that the fractures in the two guns were nearly identical.

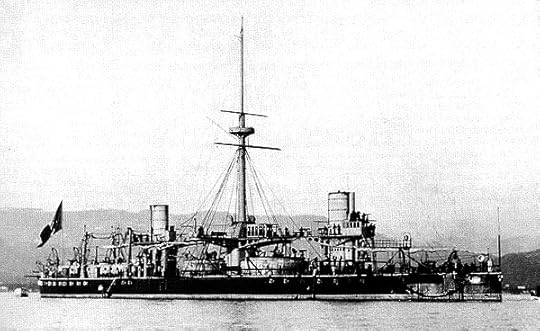

Italy’s Caio Dulio – in her time one of the most heavily armed ships afloat

Italy’s Caio Dulio – in her time one of the most heavily armed ships afloat

Another accident, which, however, fortunately was not attended by loss of life, occurred to one of the massive Armstrong 100-ton rifled muzzle-loading 17.7” guns mounted on the Italian battleship Caio Duilio. This followed close on the HMS Thunderer disaster, in March, 1880, when the gun was being tested for acceptance. In this case the barrel was fractured, the rear portion being forced to the rear, and carrying with it the covering jackets, none of the superimposed coils, however, being injured.

These accidents undoubtedly strengthened the feeling in favour of a return to breech-Ioaders which had been growing in the mind of the Navy for some time, since it was quite certain that no such mistake as double-loading could be made with a breech-loading gun, as it was impossible to force the projectile home beyond a certain distance, and consequently there would not be room for a second charge. By this stage advances in metallurgy had made breech-loading of even large weapons a practical option and over the coming years new breech-loaders were substituted for muzzle loaders still in service. Among the ships to be so upgraded were HMS Thunderer and her sisters, receiving 10” weapons, as per the diagram below.

HMS Thunderer turret re-gunned with 10″ breech-loader

This final acceptance of the superiority of the breech-loader brought to an end an era that had begun in the days of Drake and which encompassed all the great naval actions of the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was truly the end of a glorious era.

Naval Fiction set in the Ironclad Age:Britannia’s Wolf It’s 1877 and the vicious Russo-Turkish War is reaching its climax.

It’s 1877 and the vicious Russo-Turkish War is reaching its climax.

A Russian victory will pose a threat to Britain’s strategic interests. To protect them an ambitious British naval officer, Nicholas Dawlish, is assigned to the Ottoman Navy to ravage Russian supply-lines in the Black Sea. In the depths of a savage winter, as Turkish forces face defeat on all fronts, Dawlish confronts enemy ironclads, Cossack lances and merciless Kurdish irregulars, and finds himself a pawn in the rivalry of the Sultan’s half-brothers for control of the collapsing empire. And in the midst of this chaos, unwillingly and unexpectedly, Dawlish finds himself drawn to a woman whom he believes he should not love.

Neither for his own sake, nor for hers…

Britannia’s Wolf features a naval hero who is more familiar with steam, breech-loaders and torpedoes than with sails, carronades and broadsides. Dawlish joined as a boy a Royal Navy still commanded by veterans of Trafalgar but he will help forge the Dreadnought navy of Jutland and the Great War. Other books in the series follow him further along that path. Click here, or on the cover image, for more details.

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Thunderer 1879: end of RN muzzle-loaders appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 14, 2022

HMS Southampton off Toulon, 1796

“Bring me out the enemy’s ship if you can…”HMS Southampton off Toulon, 1796

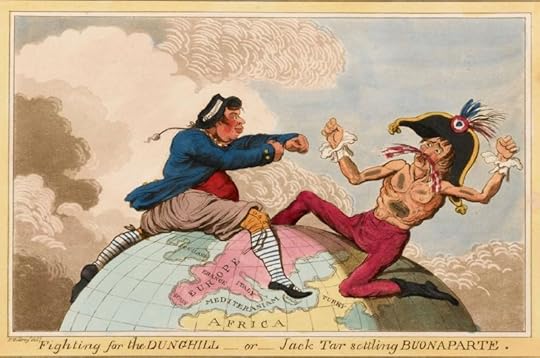

“Bring me out the enemy’s ship if you can…”HMS Southampton off Toulon, 1796Close blockade of the coasts of French-occupied countries in the Napoleonic era was the most important weapon in Britain’s armoury. It may indeed also have been the single most important factor in securing Napoleon’s ultimate defeat. He all but acknowledged this by his remark during his exile of St. Helena: “If it had not been for the English I should have been emperor of the East, but wherever there is water to float a ship we are sure to find them in our way.” A superb example of this occurred in 1796 when HMS Southampton was part of the squadron blockading Toulon.

The cartoonist James Gillray’s view of Britain’s Jack Tar as Napoleon’s Nemesis

Other articles on this site have focussed on the confident aggression that was such a characteristic of Royal Navy personnel involved in such operations. In this article, we look at an example of what was perhaps the most difficult – and all but suicidal – action of the period, the capture of an enemy vessel anchored under the protection of powerful shore batteries.

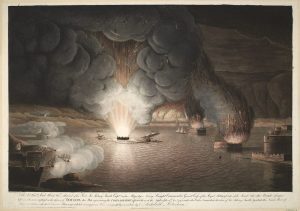

Destruction by the Royal Navy of French ships and arsenal at Toulon, 18 December 1793

The great French naval base of Toulon, in Southern France, had been the scene of fierce fighting in 1793, after Britain has entered the war against France. It was occupied by French Royalists, supported by the Royal Navy, and came under siege by French Revolutionary armies. The turning point – the capture of the base, was due to the actions of Napoleon Bonaparte, then a young, and unknown, artillery captain. This was the beginning of his ascent to power. Before evacuating, the Royal Navy destroyed many of the French warships there but the action was less than complete, thereby allowing the French Republic to make full use of it again.

In July 1796 Toulon, again the main base for the French Navy in the Mediterranea, was under close blockade by forces under the command of Sir John Jervis (1735 –1823) – not yet Earl St. Vincent – who was then flying his flag in HMS Victory. On July 9th a French corvette, which later proved to be l’Utile, armed with twenty-four 6-pounders, was detected creeping along the coast into the bay of Hyères, separated from Toulon by a jutting peninsula. Lying to the east of the latter’s tip were three islands, that of Porquerolles and the dual Illes d’Hyères. l’Utile anchored there, very close inshore, behind the islands and overlooked by powerful French shore batteries. Her officers might well have regarded her position as invulnerable.

For Jervis l’Utile represented a challenge. He signalled for Captain James McNamara (1768 –1826) of HMS Southampton to come on board Victory. McNamara was an officer of known daring who was to establish an enviable reputation as a frigate captain. HMS Southampton, his present command, was a “sixth-rate” of 670 tons, 124-feet long and carrying twenty-six 12-pounders and six 6-pounders. She had a crew of some 210. Jervis was well aware of the hazards of attempting l’Utile’s capture but he had obviously decided that if any man could manage it then it would be McNamara. He was not prepared however to give a direct order in writing and was prepared to allow McNamara a high degree of discretion. He pointed towards l’Utile and said “Bring out the enemy’s ship if you can, but take care of the King’s ship under command.” The implication was clearly that if McNamara found it too dangerous to persist then no shame would accrue from breaking off the attempt.

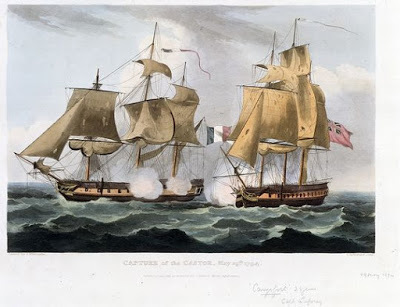

1794: Capture of the French Castor by HMS Carysfort – a 6th rate similar to HMS Southampton

1794: Capture of the French Castor by HMS Carysfort – a 6th rate similar to HMS Southampton

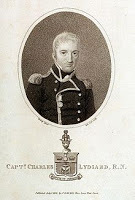

McNamara took HMS Southampton inshore in the hours of darkness and navigated through the ”Grand Pass”, the four-mile wide channel between Porquerolls and the Illes d’Hyères. L’Utile lay directly ahead, under the guns of Fort de Brégançon on the coast. In his report the next day to Jervis McNamara stated “I had got within pistol-shot of the enemy’s ship before I was discovered.” In splendid terminology of the day he “cautioned the (French) captain, through a trumpet, not to make a fruitless resistance; when he immediately snapped his pistol and fired his broadside.” McNamara then laid HMS Southampton alongside l’Utile and launched a boarding party under the command of his First Lieutenant, Charles Lydiard (circa 1770 – 1809). Of him McNamara was to write that “his intrepidity no word can describe” and that Lydiard “entered and carried her in about ten minutes, although he met with a spirited resistance from the captain (who fell) and a hundred men at arms.”

Charles Lydiard

Presumably to get his prize away as quickly as possible – Fort de Brégançon had now opened fire – McNamara had the two vessels lashed together, HMS Southampton having sails set and the time needed to set them on l’Utile too great a luxury in the circumstances. It was quickly realised however that l’Utile was going nowhere. In the darkness it had not been seen that in addition to her anchor-cable – which can be presumed to have been cut free by now – she was also secured to the shore by a hawser. Lydiard found it and hacked through it by repeated blows of his sword. By one-thirty in the morning of July 10th both ships had emerged from the treacherous waters of the Grand Pass and had joined the blockading squadron.

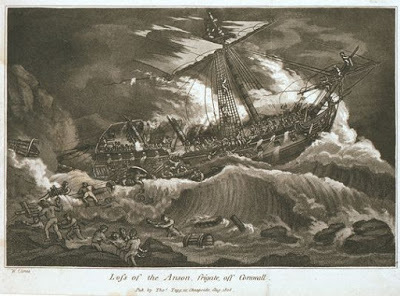

Lydiard was promoted to command of the prize and later, as captain of HMS Anson, was to distinguish himself in, in company with HMS Arethusa, in capture at Havana of the Spanish frigate Pomona which was guarded by twelve gunboats and, like l’Utile, by a shore battery. He was to win further praise by his participation in the capture of the Dutch base of Curacao. HMS Anson returned to Britain thereafter and was assigned to blockade duty off the French Atlantic coast. This was to bring Lydiard’s promising career to a tragic end. During a gale in December 1807, HMS Anson was driven towards the Cornish coast. Attempts to anchor failed and Lydiard attempted to beach her to save his crew. Many were able to get to shore along the fallen mainmast but Lydiard was among the 60 dead, remaining on board to get as many away as possible and at last being washed off and drowned when he tried to leave. His was a noble death.

The loss of HMS Anson, December 1807

McNamara’s career was to be longer. He seems to have been a Jack Aubrey type, and his colourful record included killing an army colonel in a duel. The origin of the quarrel was a petty one – one’s dog attacked the other’s while they were walking in Hyde Park. The owners took sides and unacceptable language appears to have been used – in his subsequent trial for manslaughter McNamara claimed that he had no option but to fight if he was to maintain his dignity as a naval officer. Senior naval officers, including Nelson, Hood, Troubridge – and, it is pleasant to record, Lydiard – testified that he was the “reverse of quarrelsome”. He was acquitted and was to have an active career that culminated in promotion to rear-admiral.

Britannia’s Reach 1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

1881: On a broad river deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers thrashes slowly upstream. Laden with troops, horses and artillery, intent on conquest and revenge.

Ahead lies a commercial empire that was wrested from a British consortium in a bloody revolution. Now the investors are determined to recoup their losses and are funding a vicious war to do so.

Nicholas Dawlish, an ambitious British naval officer, is playing a leading role in the expedition. But as brutal land and river battles mark its progress upriver, and as both sides inflict and endure ever greater suffering, stalemate threatens.

And Dawlish finds himself forced to make a terrible ethical choice if he is to return to Britain with some shreds of integrity remaining . . .

For US – click hereFor UK – click hereFor Australia and New Zealand – click hereAnd, as always, Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read it at no extra cost. The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more details

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to ten volumes, and counting. Click on the banner above for more detailsSix free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post HMS Southampton off Toulon, 1796 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 7, 2022

Crimean War’s White Sea Theatre, 1854

The Crimean War’s White Sea Theatre, 1854

The Crimean War’s White Sea Theatre, 1854This article tells about British naval operations in the White Sea in 1854. The Crimean War (1854 – 56) is most remembered for images of the charge of Britain’s Light Brigade at Balaclava, the privations suffered by the ill-equipped besiegers of Sevastopol through a deadly winter and the achievements of Florence Nightingale, all episodes that took place in the Crimea itself. Earlier blogs have however pointed out that lesser-known operations took place in the Baltic and on the Kamchatka peninsula on Russia’s Northern Pacific coast. (Click here to read about the latter). The least-known operations of all took place however on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, in the White Sea and in the Kola Inlet. Both these locations were to play roles in both World Wars as landing points for aid sent by the Western Allies to Russia, most notably via the epic Arctic Convoys of WW2. They were also to provide bases for ineffectual British support of White Russian forces against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War.

[image error]

British and Dutch shipping had been accessing Russia for trade through this area since the late sixteenth century – indeed the Dutch navigator Willem Barents (1550 – 1597) had given his name to the sea north of which forms part of the Arctic Ocean. Arkhangelsk, a major city at the southern end of the White Sea had remained a major trading port ever since. Murmansk, at the head of the Kola inlet further to the west, also had port facilities, though minor.

When Britain and France entered the war in early 1854 to support the Turks, who had already been fighting the Russians for several months, the decision was taken to send a small Royal Navy squadron to harry Russian presence in these northern waters by attacking shipping and forts. The Russian Navy had no significant presence in the area and weather conditions in winter made it advisable to confine operations to the summer months.

Erasmus Ommanney

The British squadron that was sent was under the overall command of Captain Erasmus Ommanney (1814 – 1904). He had been present at the Battle of Navarino when he was thirteen years old – naval careers began early in those days! He had previous experience in high latitudes as he had been second-in-command of the expedition sent in 1850 to search for Sir John Franklin and his ships Erebus and Terror which had disappeared during an effort to find the North-West Passage. It was Ommanney who discovered “fragments of stores and ragged clothing and the remains of an encampment on Beechey Island ” though no further trace could be found. Ommanney was awarded the Arctic Medal for this and he was to spend of his later years in Arctic-related scientific work, for which he was knighted. He rose to the rank of vice-admiral.

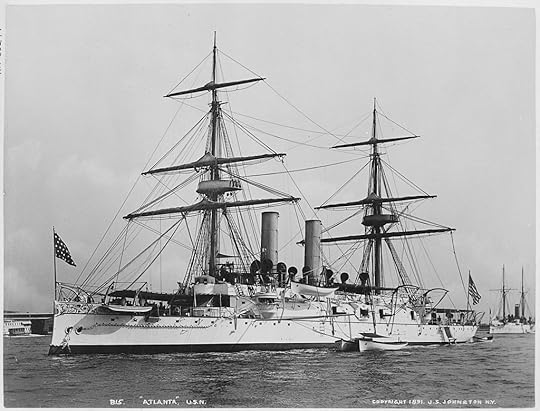

The squadron sent against Russia in 1854 under Ommanney’s command consisted of the 26-gun frigate HMS Eurydice and two near-identical steam sloops, HMS Miranda and HMS Brisk, carrying 15 and 16 guns respectively. The 910-ton, 140-foot Eurydice carried sail only and though she entered service in 1843 she was little different to frigates of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic War eras. Her ultimate fate was to be a tragic one (Click here to read a separate article about this) but at the time of the White Sea expedition that still lay some three decades in the future. All her guns were truck-mounted 32-pounder muzzleloaders, no different to those in service at Trafalgar some fifty years before.

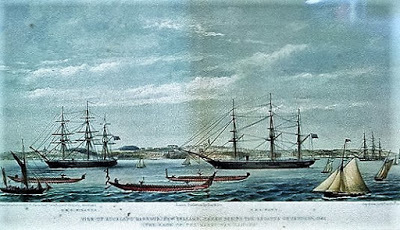

HMS Miranda (on right) later seen in service in New Zealand waters

Though commissioned only a few years later, the Miranda and the Brisk, though also wooden-hulled, represented major technological advances. Improved versions of HMS Rattler, the first screw-driven warship in Royal Navy service, these two 1,523-ton, 196- foot vessels could make just over 10 knots maximum under steam power. This advantage was however offset by the fact that, like Eurydice, they were still armed only with 32-pounders on the broadside.

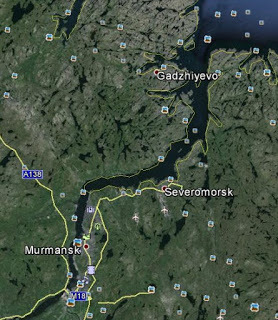

The White Sea – thanks to Google Earth

The small force arrived off the north Russian coast in July 1854 and the campaign started by advancing towards the southern end of the White Sea. Here, on a small archipelago called the Solovetsky Islands was something of a curiosity – a Russian fortress that was also a monastery. Much of this massive construction dated from the 16th century and then and in the early 17th century, it had withstood attacks by the Livonian Order (a branch of the Teutonic Knights) and by the Swedes. It is hard at this remove to understand what was thought to be gained by attacking this fortress. (In other blogs I have approvingly quoted Nelson’s dictum that “A ship’s a fool to fight a fort”).

Even had Ommanney destroyed this fortress-monastery – in itself an impossibility given the limited forces at his disposal – the strategic value would have been essentially zero. In the event, the bombardment lasted two days – 6th and 7th July. It achieved nothing and had the fort been better armed the British ships might have stood a good chance of being destroyed themselves. Two weeks later, on July 23rd, Miranda and Brisk, operating close inshore, bombarded the small town of Novitska.

Solovetsky Fortress-Monastery in 2009 (courtesy of Wikipedia entry)

From Russian pamphlet showing bombardment of Solovetsky Fortress

The only other significant action was further west, in the Kola inlet. Miranda sailed southwards – that is upriver – towards the settlement of Kola, just south Murmansk. Here steam propulsion was a major advantage since the thirty miles distance to be covered was against a strong current and in waters sometimes so narrow that there was scarcely room to swing the ship.

Kola Inlet today

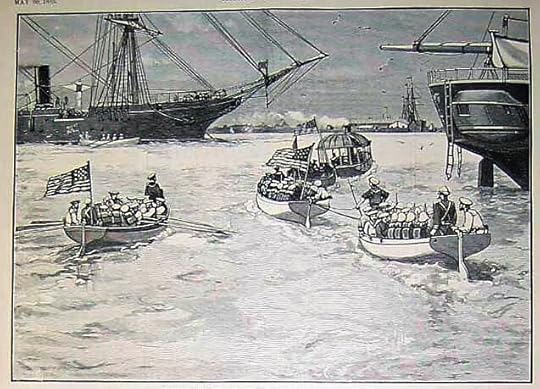

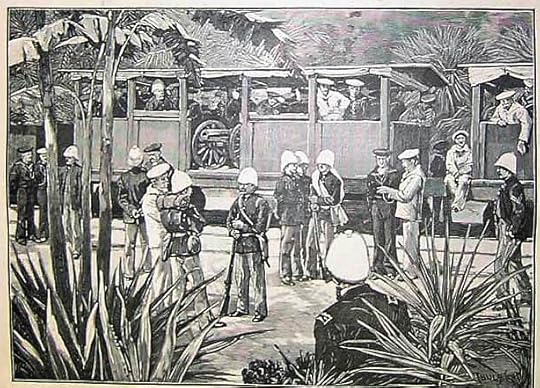

Miranda anchored off Kola on August 23rd and under a flag of truce a demand was made that the fort there, its, garrison and all government property be surrendered. The crew remained at their stations through the night and when no answer was returned in the morning, the flag of truce was hauled down, and the Miranda, getting within 250 yards of the shore battery, opened a fire of grape and canister. This suppressed opposition enough to allow a landing party of bluejackets and marines to storm ashore. They succeeded in dislodging the enemy from the batteries and in capturing the guns. A hot fire was opened on them from the towers of a nearby monastery but its defenders were also driven out. Government stores and buildings were set on fire and completely consumed. Miranda then dropped downriver again.

That was the end of the campaign and the squadron returned to Britain. Miranda proceeded thereafter to the Black Sea to support the main Allied effort. Captain Edmund Moubray Lyons (1819 -1855), who had manoeuvred her up the Kola Inlet with considerable skill, died of wounds in June 1855. Miranda herself had an active career thereafter, mainly in Australian and New Zealand waters, and was broken up in 1869. Brisk was to have a similarly active career, most notably including service on the West Africa Anti-Slavery Patrol. She survived to 1870. The Eurydice, by then an anachronism, was to come to a tragic end in 1878. (Click here) ].

And the final verdict on the operations in the White Sea in 1854? It is easy to be critical with the advantage of hindsight, but even so one can only question why lives – both British and Russian – should ever have been squandered in such a pointless exercise. The same applies to the operation in the Northern Pacific. What, in either case, was the strategic value?

There was to be a terrible postscript. In 1923, after its monks had been murdered, the Solovetsky Monastery was to become a slave-labour camp for alleged enemies of the new Soviet Marxist state. Further camps were built on the adjoining Solovetsky Islands. As such it was to earn the unenviable name of “Mother of the Gulag” since it established a model for other camps in the vast structure of Marxist tyranny. By 1930, “about 50,000” prisoners were held there, with another 30,000 held on the nearby mainland, many of the prisoners being sent to work as slaves on construction of the White Sea to Baltic Canal. How many died at Solovetsky, as at other Gulag camps will never be known. One is reminded of the chilling words at the end of Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago that summarise the unknown fate in the Gulag of Lara, the heroine: “She was just another name on a long list, that later got mislaid.”

We must value Freedom while we have it.

Britannia’s Gamble This volume of the Dawlish Chronicles is set against the background of the murderous revolt in the Sudan by the Isis of its day, and which triggered one of the most dramatic campaigns of the British Army and the Royal Navy in the Victorian era. It’s available in paperback and Kindle, and subscribers to Kindle Unlimited and Prime can read at no extra charge

This volume of the Dawlish Chronicles is set against the background of the murderous revolt in the Sudan by the Isis of its day, and which triggered one of the most dramatic campaigns of the British Army and the Royal Navy in the Victorian era. It’s available in paperback and Kindle, and subscribers to Kindle Unlimited and Prime can read at no extra chargeExtract below from review by A. Belfrage in “Historical Novels Review” – November 2018

“Some authors have so researched their period that they seem to live the events, the surroundings, the details they describe. Antoine Vanner is one of these. He breathes such life into his narrative that you would think him a correspondent in the 1880s Sudan writing what he sees, rather than a man of today looking back . . . The opening chapter is a tour de force, leaving this reader emotionally exhausted after surviving nail-biting action when wave after wave of insurgents attack the British formations. After such an opening, an author has much to live up to, but Vanner does so with aplomb, guiding the reader through the political complexities of the time while generously lacing his narrative with period detail.

Captain Dawlish finds himself commanding a desperate rescue operation that more than explains the title of the book. It is tense, gripping action at its best, enhanced by the sympathetic and introspective Nicholas Dawlish. Vanner does not shy away from the brutalities of war: some descriptions are so harrowing I had to take the odd moment before going on. But go on I must, desperate to know how this fantastic adventure would end.”

Click here, or on the cover image above, for more detailsDo you enjoy naval fiction?If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read any of the ten (s0 far!) Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Crimean War’s White Sea Theatre, 1854 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 31, 2022

Royal Edward & UB-14, 1915

Massacre at Sea: Royal Edward and UB-14, 1915

Massacre at Sea: Royal Edward and UB-14, 1915In both World Wars the greatest danger many troops faced, especially if they were in support or non-frontline roles, may well have been that of sinking of their transports. It is a tribute to the efficacy of convoy and escort provisions that in practice only few of the millions of men who were transported by ocean did experience such nightmares. When the worst did happen however the chances of escape from below decks on an overcrowded troopship could well be low and the casualty numbers correspondingly high. One such disaster, largely forgotten today, involved the liner Royal Edward in August 1915.

1915 can be fairly regarded as the year in which the submarine first demonstrated its full potential far from home bases. The sinking by German U-boats of the Lusitania, the attacks on naval vessels off the beaches of Gallipoli (click here for a blog article on this) and the campaign against Britain’s fishing fleet were examples. In the second half of the year U-boats operating out of Austro-Hungarian bases on the Adriatic found new hunting grounds the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. The Dardanelles expedition was stalled, but still manpower-intensive. The Turkish threat to the Suez Canal remained and Mesopotamia – modern Iraq – sucked in more and more troops as British advances there met increased opposition. Together, these demands necessitated major Allied shipping movements, including troop transportation, in the Mediterranean.

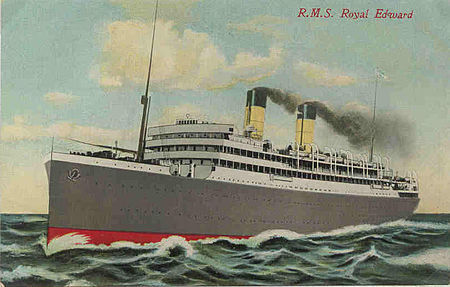

Contemporary postcard: Royal Edward in civilian service, pre-WW1

The Royal Edward was a large, modern and virtually new liner when, like her identical sister Royal George, she was requisitioned for service as a British troopship in 1914. Of 11,117 tons and 523 feet long, and originally named Cairo and Heliopolis, these vessels had been built for fast mail-service between Marseilles and Alexandria. Steam turbines and three shafts gave them a top speed of 19 knots and they had accommodation for 1114 passengers, 344 of them in first class. In 1909 both ships were sold on to the “Royal Line”, a subsidiary company of the Canadian Northern Railway, to establish a service between Britain and Canada. They were renamed Royal Edward and Royal George. Under these names, they were to become troopships, a role for which their size and speed made them ideal.

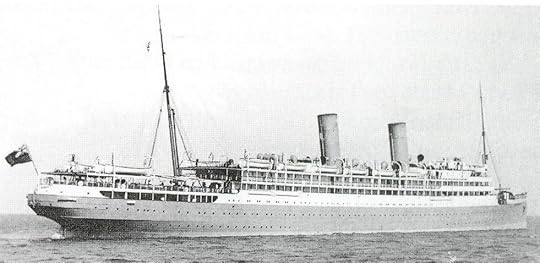

Royal Edward as a troopship, 1914

In July-August 1915 the Royal George transported troops from Britain who were intended to reinforce the British 29th Division at Gallipoli. A brief stop was made at Alexandria before heading north-west up into the Aegean towards the main British staging base at Mudros. Sources vary as to the exact total of men carried but it appears to have been around 1600, of whom some 200 represented crew. By this stage German – and to a lesser extent Austro-Hungarian – submarine presence had been making itself felt in the area. Among these craft was the tiny coastal submarine UB-14.

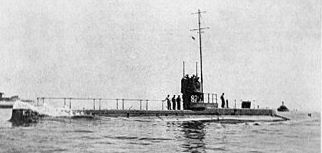

UB-14 and her crew – tiny but very, very dangerous

Constructed at Bremen in North Germany and a mere 92 feet long and of only 125 tons surface displacement, the UB-14 was a new vessel. She had been transported overland, in sections, by rail from Germany before being reassembled at the Austro-Hungarian base at Pola. Her armament was limited – two 17-inch torpedo tubes and a single machine gun. She had a crew of fourteen and diesel and electric power on a single shaft only. Despite her small size and puny armament, she was destined to inflict higher losses on the enemy than many larger and more potent vessels.

UB-14’s sister, UB-13, being transported by rail – in sections – from Germany

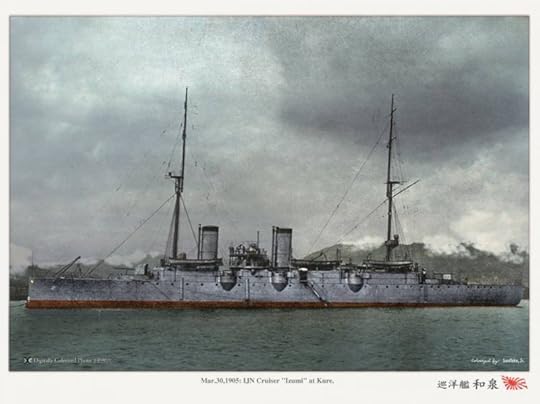

Her debut was spectacular. Under her first commander, Oberleutnant Heino von Heimburg (1889-1945), she sank the 9800-ton Italian armoured cruiser Amalfi off Venice in July 7th 1915. This was von Heimburg’s second victory, for while previously commanding UB-15 he had sunk the Italian submarine Medusa on June 10th. Following the Amalfi sinking, UB-14 received orders to proceed to Turkey – a passage achieved only with difficulty, and under tow for part of the way by an Austro-Hungarian destroyer, due to her limited range.

UB-14’s first victim – the 9800-ton Italian armoured cruiser Amalfi

On August 13th UB-14 sighted two ships, unescorted, some 60 miles north of Crete. The first proved to be a hospital ship, the Soudan, and, marked as such, von Heimburg allowed her to pass safely. The second was the Royal Edward. It seems that an evacuation drill had taken place on board her only shortly before and a major part of the troops carried was now below and re-stowing their kit, a fact that was to have tragic consequences. At one-mile range UB-14 launched a single torpedo. It struck the troopship close to the stern and she began to settle quickly. Though the radio operator had time to transmit a distress signal the huge ship went down in six minutes. Many of the troops, trapped below, went down with her but many also found themselves in the water.

von Heimburg with Blue Max – 1917

Alerted by the radio message, the Soudan came about and spent the next six hours recovering some 440 men. Two French destroyers and some trawlers also arrived and rescued another 221. Despite this, the final death toll was still high – some 935 according to some accounts. UB-14had already departed from the scene and the lack of British escorts had almost certainly contributed to her success.

UB-14’s career was only beginning. Three weeks later, on September 2nd 1915, still in the Aegean, she torpedoed the 11,900-ton transport Southland, then carrying Australian troops. Though 40 of the 1400 men on board died, the remainder got away in lifeboats. The Southland herself was saved from sinking by being beached on a nearby island. Though repaired, her luck was not to last and she was to be torpedoed and sunk in 1917 off the north-west coast of Ireland.

In late 1915 the UB-14 made the dangerous passage up the Dardanelles but was forced to put into port for repairs. Her next victim was not to be by torpedo but due to a personal exploit by Oberleutnant von Heimburg. On September 4th a Royal Navy submarine, the E7 had also made the passage dangerous through the strait but had become entangled in nets below the surface. Turkish craft had dropped several mines around her, but without result. von Heimburg took matters into his own hands. He rowed out to the site with the UB-14’s cook and used a plumb weight to locate the E7. On finding metal and knowing he was directly over the trapped submarine he dropped a further charge. Deciding that the game was up, the E7 surfaced and came under fire from Turkish shore batteries. Her commander ordered “abandon ship” and set scuttling charges, thereby sinking his vessel. von Heimburg somehow survived this maelstrom and was subsequently – and deservedly – awarded the Pour le Mérite, the coveted Blue Max.

HMS E7, similar to E20, also sunk by von Heimburg

UB-14 was to operate thereafter in the Black Sea, where she was to sink two Allied vessels in October 1915, and in the Sea of Marmara, where she sank the British submarine E20 in November. Von Heimburg was replaced as commander early in 1916 but the UB-14’s Black Sea career was to continue to the end of the war. She ended by being scuttled off Sevastopol in early 1919 following Germany’s surrender.

And von Heimburg’s later career? He was to retire from the German Navy as an admiral in 1943, following which – one regrets to record – he became a judge on a Nazi “People’s Court”. He was captured by the Soviets in 1945, taken to Russia, and died in captivity there. It was an ignominious end, in both moral and personal terms, for an undoubtedly brave man.

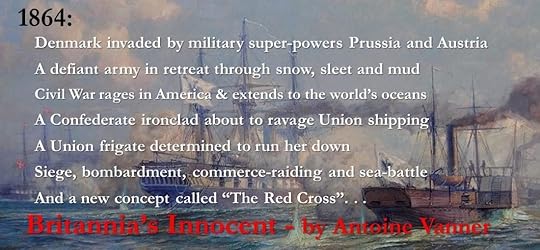

Do you enjoy naval fiction?If you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read any of the ten (s0 far!) Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.

Click on the image below to read the opening chapters of Britannia’s Innocent, the first in the series.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Royal Edward & UB-14, 1915 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 25, 2022

Heroic Merchantman vs. a French Privateer, 1811

Three Sisters Merchantman vs. a French Privateer, 1811

Three Sisters Merchantman vs. a French Privateer, 1811Throughout the Age of Fighting Sail merchant shipping – from small coastal craft to large vessels engaged in interoceanic trade – were at the mercy of privateers. These were privately owned vessels issued with “letters of marque” that authorised them to attack and capture enemy shipping. If captured they would be treated as prisoners of war but their payment was dependent on the value of prizes they captured. This financial incentive meant that privateers – of which the French and American were the most active and successful – were of necessity daring and ruthless. Since Britain had the largest merchant fleet in the world it was to the most tempting target, especially as, in the days before radio, there was no ability to transmit a distress call, even when friendly vessels might have been in the vicinity. Though convoys, escorted by Royal Navy vessels, played an important role from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, Britain’s global commitments meant that available naval assets were always stretched. As a consequence, many merchantmen sailed independently and were reliant on their own ability – and willingness – to defend themselves. One such vessel was the Three Sisters, which fought off a heavily armed French privateer in 1811.

A trading brig – the Three Sisters, at largest, might have looked like this.

Painting by William Huggins (1820 – 1880)