Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 6

December 8, 2023

Frigate Duel, 1782: HMS Santa Margarita vs. L’Amazone

Frigate Duel, 1782:HMS Santa Margarita vs. L’Amazone

Frigate Duel, 1782:HMS Santa Margarita vs. L’AmazoneIn reading about warfare in the Age of Fighting Sail one is invariably impressed by the aggression and sheer bloody-minded will to win that characterised the officers and crews of the Royal Navy. These were the factors that regularly brought victory even when the odds seemed stacked against British ships and the enemy, usually French or Spanish, never seems to have had the same single-minded focus on prevailing. Only in the War of 1812, when Britain again confronted the United States, did the Royal Navy consistently encounter enemies with the same ruthless commitment to victory.

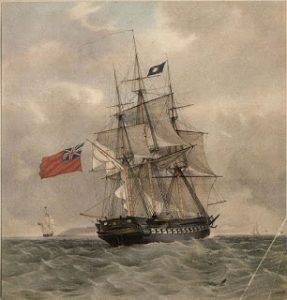

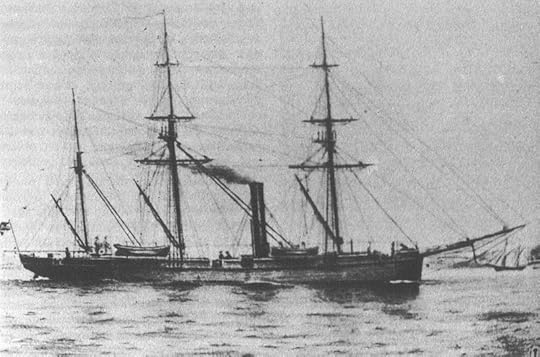

HMS Pomone, a typical frigate

These thoughts came to me this week when leafing again through the Victorian classic, “Deeds of Naval Daring” by Admiral Edward Giffard (1812-1867), and came on an action I had not previously known of. This was a duel between equally-matched British and French frigates, HMS Santa Margarita, an ex-Spanish prize, and the French L’Amazone in 1782. Built for the Spanish navy in 1774, HMS Santa Margarita had been captured off Lisbon in November 1779. Take into British service, she was refitted in 1780/81 and sent in June 1781, under the command of Captain Elliot Salter, to join a squadron off the American coast

In September 1781, French success in the Battle of the Virginia Capes was to be the deciding factor in ending the American War of Independence as it cut off supplies to British forces at Yorktown and necessitated their surrender. The final peace-treaty would not be signed for another year and a half but the war was effectively decided from that point. The outright British victory over a French fleet at the Battle of the Saintes in April 1782, impressive as it was at a tactical level, was a hollow one that had no impact on the outcome of the war.

Notwithstanding this, a French naval squadron was still operating off the American coast in July 1782 under Admiral de Vaudreuil (1724-1802), who had taken command of the remnant of the French fleet after the Saintes battle. It was this force that Salter in HMS Santa Margarita, on detached service, was to run into off Cape Henry, at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, on 29th July. Salter had initially spotted a frigate only – apparently a 36-gun unit like his own vessel – and gave chase. As Santa Margarita neared her quarry, eight French ships-of-the-line were seen bearing down on her. Salter turned to fly, caught as he was between the French squadron and a lee shore, and the frigate he had initially chased now turned and came on after him. With their superior speed, both frigates outran the heavier units but HMS Santa Margarita appears to have been the faster of the two. By mid-afternoon, the French unit – which proved to be L’ Amazone – decided to give up the chase and return to the squadron. Given the very powerful French force in the area, Salter might have been well-advised to continue on and to complete his escape. Instead, he came about and followed L’Amazone. Once again HMS Santa Margarita’s superior speed proved its value and within two hours both ships were within gunshot.

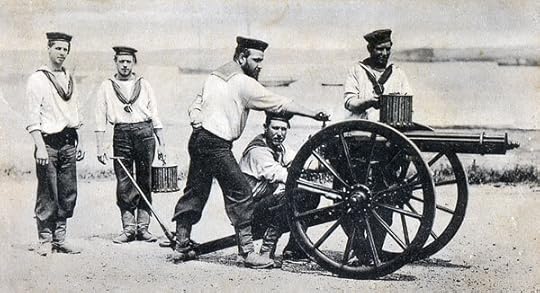

French gun crew with carronade – a rather idealised view, with formal and immaculate uniforms!

French gun crew with carronade – a rather idealised view, with formal and immaculate uniforms!

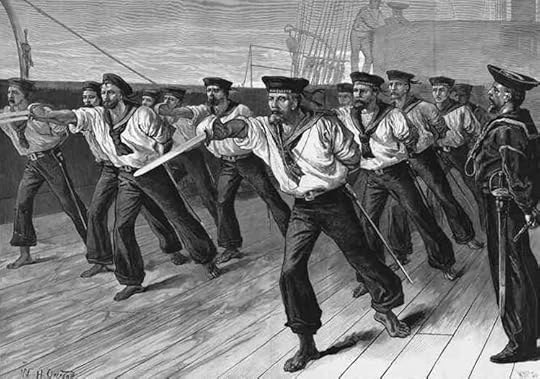

The opening broadside came from L’Amazone – one suspects that, in accordance with French practice, she may have been aimed at HMS Santa Margarita’s masts and rigging. Salter held his fire however and manoeuvred so as to rake his opponent – a devastating action that sent fire down the enemy’s central axis – and followed up by taking his ship “within pistol shot.” What is shocking to the modern reader is that the close-range slugging match that followed lasted an hour and a quarter. One can only imagine the hell of noise and smoke, injury and death that followed. Fighting a sailing warship demanded more than a single team, but rather a team of teams, each one – especially the individual gun crews and the marines in the tops – fighting its own battle and yet still an integral part of the larger team. Continuous exercising would have been one factor to guarantee this level of efficiency in action but one suspects that morale was even more important, and in this the British crews usually seem to have had the edge.

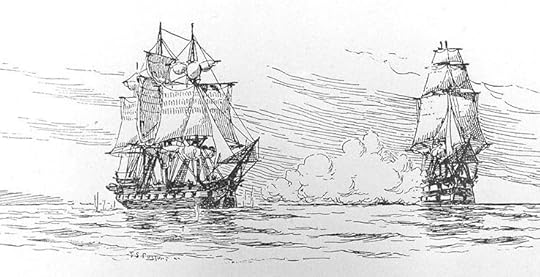

HMS Santa Margarita (l) in action with L’Amazone. She is seen after passing under her stern to rake her

Painting by Robert Dodd (1748–1815) and/or Ralph Dodd (circa 1756-1822) with thanks to Wikimedia Commons

Badly shattered, with seventy killed, and slightly more wounded from a crew of three hundred, with both main and mizzen masts toppled overboard, with several guns dismounted and with four feet of water in her hold, L’Amazone struck her colours. HMS Santa Margarita took her prize in tow. Salter’s crew worked through the night to repair L’Amazone’s damage sufficiently to sail her away. A start was made on transferring her surviving crew to HMS Santa Margarita as prisoners – a process hindered by the boats of both ships having been destroyed or damaged in the fighting. At dawn however, the French squadron was seen approaching. There was no option but to abandon L’Amazone. Salter’s preference would have been to burn her but, with large numbers of French prisoners still on the crippled ship, common humanity prevented it. By now faced with overwhelming force, HMS Santa Margarita once again made use of her speed and escaped. Her casualties were five dead and seventeen wounded. As in so many of such actions one is stuck by the disparity in casualties – perhaps because HMS Santa Margarita managed to rake her opponent.

HMS Santa Margarita cutting L’Amazone adrift: 30 July 1782.

Note French squadron coming up on the left. Painting by Robert Dodd

A pleasing aspect of the account given by Giffard is that it includes extracts from Salter’s official report. He gave considerable credit to the French captain, noting the“gallant and officer-like conduct of Viscomte de Montguiote in leading his ship into action”, who was killed early in the action, and even more to the second-in-command who took over, the Chevalier de Lepine. This gentleman “did everything that an experienced officer could possibly do, and did not surrender until he himself and all his officers but one, and about half the ship’s company were either killed or wounded.” After listing L’Amazone’s damage, Salter characterised it as “a situation sufficiently bad to justify to his king (sic) and country the necessity of surrender.” One suspects that had the outcome been reversed, the French captain’s report would have been equally generous of spirit.

I have been unable to find out any more about Elliot Salter, other than that the first mention of him was as a lieutenant in 1765 and that he died in 1790, how, or at what age or rank, I do not know. Would any of this article’s readers be able to shed some light on the career of this intrepid officer?

s

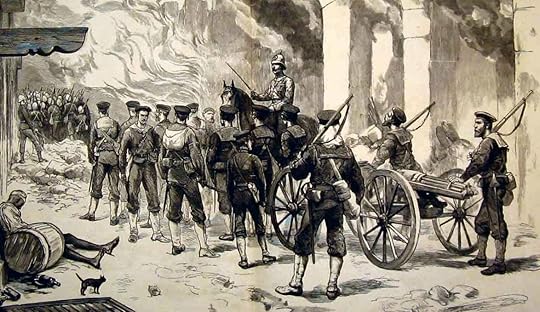

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

Britain is neutral in this conflict, but large British interests – railway and mining enterprises – are at risk as the war-front edges ever closer. Investors in London are demanding British action to protect their assets.

Sub-Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is serving on the Pacific Station in the gunvessel HMS Sprightly. She, and her resourceful captain, are tasked with taking ‘appropriate’ action to guarantee the safety of these interests. The situation is complex – not only Juarista, French and Imperial Mexican forces but bandit groups, a volunteer Belgian Legion and ex-Confederate mercenaries are involved. And there’s a powerful ironclad, flying Imperial Mexican colours, commanded by an Austrian aristocrat who’s desperate for glory.

Dawlish is plunged into deadly action by land and sea and, with fluency in French and Spanish, he’ll be his captain’s right-hand man in a web of political intrigue, treachery and greed in which a single mistake can end both their careers.

But for Dawlish there’s something worse, a heart-breaking encounter with a figure from his past to whom he’s linked by a solemn promise that he can’t fulfill. What follows will be torment for his emotions and his conscience . . .

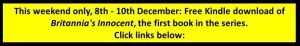

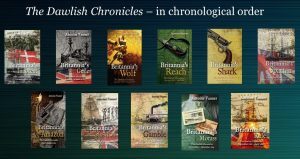

Available in Large Paperback and Kindle formats. Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read at no extra charge. Kindle version available for pre-order. Click the marketplaces below for ordering details:United States CanadaUnited Kingdom Australia & New ZealandBelow are the twelve Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited Subscribers. United States CanadaUnited Kingdom Australia & New Zealand

United States CanadaUnited Kingdom Australia & New Zealand

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Frigate Duel, 1782: HMS Santa Margarita vs. L’Amazone appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 29, 2023

HMS Queen Charlotte loss 1800

The loss of HMS Queen Charlotte, 1800

The loss of HMS Queen Charlotte, 1800During the twentieth century, damage-control was to become a naval discipline in itself, and was to result in many epics of courage. In earlier centuries such response was on a much more ad-hoc basis but the bravery and self-reliance of the crews involved were no less than those of later generations. One shining example of such heroism was provided by the young Lieutenant George Dundas in 1800, though it was not enough to prevent the loss of HMS Queen Charlotte.

In another blog I dealt with the disaster that overcame the line-of battle ship HMS Royal George, named after King George III, in 1782 (Click here to read it). Naming ships after the royal family of the time was to prove unfortunate since, 18 years later, on March 16th 1800, a newer ship, named HMS Queen Charlotte after the king’s wife, was to meet a no less spectacular end.

The Charlotte in the thick of it during the Battle of the Glorious First of June – painting by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740-1812)

Laid down in the same year as the Royal George was lost, MMS Queen Charlotte’s completion was to prove a lengthy affair as the fleet was run down in the aftermath of the American War of Independence. She was finally launched in 1790 when developments in France were making the prospects of a new war seemed more likely by the month. At 2286 tons, 190 ft length, and carrying a 100-gun armament, she was, next to the Ville de Paris, a captured French vessel taken into Royal Navy service, the largest British ship afloat. After war broke out again with France she was to serve as Admiral Lord Howe’s flagship at the Battle of the Glorious First of June in 1794 and the following year she was present at the controversial Battle of Groix, a British partial victory off the coast of Brittany.

Battle of Groix, 23rd June 1795; an aquatint by Robert Dodd, from an original by Captain Alexander Becher, RN

HMS Queen Charlotte was to play a less glorious role two years later when she was to become a focus of discontent during the Spithead Mutiny. After the mutiny’s suppression she seems to have retained a reputation for indiscipline and when she was sent to the Mediterranean in 1799 the Commander in Chief, Earl St.Vincent, informed the Admiralty that she “will be better here for she has been the root of all the evil you have been disturbed with.” Commanded by Captain James Todd, she was to serve as the flagship of Vice-Admiral Lord Keith.

A contemporary cartoon showing mutineers at Spithead holding an officer (l) to account

Hostilities against the French were now in full swing. On March 16th 1800 Lord Keith landed at Leghorn or Livorno, in Northern Italy and instructed Captain Todd to reconnoiter the French-occupied island of Carpalia, halfway between Sardinia and the Italian coast.

At 0600 hrs the following morning, while the Queen Charlotte was still close to shore, fire was detected in hay stowed close to the admiral’s cabin, close to a slow-match kept burning in a tub for use with the signal guns. Flames spread rapidly and ran up the mainmast, setting the mainsail on fire. The conflagration quickly took hold of the stowed boats, threatening this means of escape.

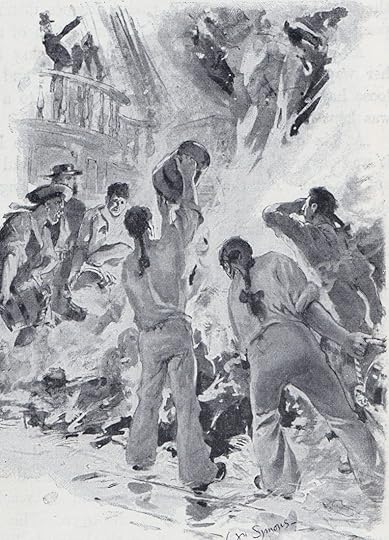

Fighting the fire – a Victorian illustration

In the midst of this Captain Todd and his first lieutenant, Bainbridge, remained on the quarterdeck and directed fire-fighting operations. The pumps were manned but without significant effect. Many of the officers were asleep in their berths, one being the 22-year old Lieutenant George Dundas who, after being woken by a marine, found it impossible to get up the after hatchway because of smoke. He then tried the main hatchway but, choking and half-suffocated, he fell back before getting out. He now went forward again, this time to the fore hatch, and he managed to reach the forecastle, where a crowd of petty officers and men had assembled.

The carpenter suggested sending men down to flood the lower decks and to batten down the hatches in between to prevent the fire higher up from reaching down. Dundas went down with seventy volunteers – it must have been hell below decks by that stage. They opened the lower deck ports, plugged the scuppers, cleared the hammocks and turned on the water-cocks. Burning wood and rigging were falling down the hatchways, filling the space with steam as well as smoke. Dundas and his men managed to get the hatches closed and covered with wet hammocks to keep the fire away from the lower deck and magazine.

By 0900 the middle deck was burned so badly that several of its guns crashed through it. The situation now being hopeless, Dundas and his men finally retreated to the forecastle by climbing from the lower deck ports. He found there some 150 men drawing up water in buckets and throwing it on the fire, but their efforts were futile.

By now all boats were burned, other than the launch, which managed to get away without mast, sails, oars or rudder. Many men tried to swim for her, but she was drifting too fast to leeward for them to catch. Now the mizzen mast also came down, throwing more men into the water. The ship’s guns, which were loaded, now began to go off in the heat, adding to the horror.

HMS Queen Charlotte was still close enough to shore for Admiral Keith to see the fire and he induced several Italian boatmen to send a half-dozen craft to her. As they neared, Queen Charlotte’s guns began going off and they turned away. A boat from an American ship did approach and drew alongside, but too many jumped in and they swamped her.

The remnants of HMS Queen Charlotte as found by the brig HMS Speedy

George Dundas

By now the entire ship was ablaze and dozens of men – perhaps even hundreds, had crawled out along the bow spirit and jib-boom, so many indeed that these failed under the weight and threw yet more men into the water. The Italian boatmen, under direction of a British officer, made one more attempt and succeeded in taking off the survivors at the bows. As they pulled away the flames finally reached the main magazine and the Queen Charlotte exploded. Only five hours had passed since the fire was detected but in that time 673 officers and men had died.

It is pleasing to learn that George Dundas, the indomitable hero of the day, was to be rewarded by command of the sixth-rate brig HMS Calpe, which he was to take into action in the Battle of the Gut of Gibraltar the following year. He was to have a distinguished naval and political career thereafter and at the time of his death in 1834 was First Naval Lord – the professional head of the Royal Navy.

The Twelfth Dawlish Chronicles Novel will be published in mid-December 2023If you’re not already familiar with the series, which takes historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting Steam, now’s the time to start!If you are a subscriber to Kindle Unlimited you can read all eleven volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the

Dawlish Chronicles ma

iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post HMS Queen Charlotte loss 1800 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 10, 2023

Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914: Part 2

The Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914: Part 2

If you missed the first part of this article, please click here to read it.

The Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914: Part 2

If you missed the first part of this article, please click here to read it.

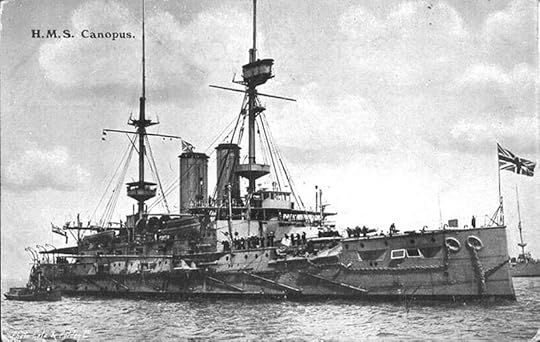

HMS Glasgow entered the Chilean port of Coronel to collect messages and news from the British consul. She found there a German supply ship which promptly radioed news of Glasgow’s arrival to von Spee. In line with the laws of neutrality HMS Glasgow could take no action in port against this vessel. On receipt of the news von Spee headed south to find the British cruiser. Alerted by German radio-traffic (the importance of radio silence does not appear to have been yet appreciated) Cradock turned north with his squadron to meet the Germans, leaving the pre-dreadnought HMS Canopus far behind and HMS Glasgow steaming south to join him.

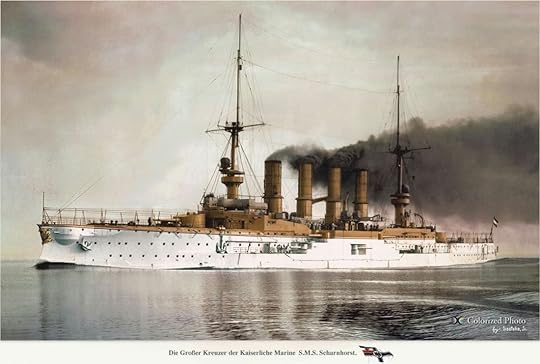

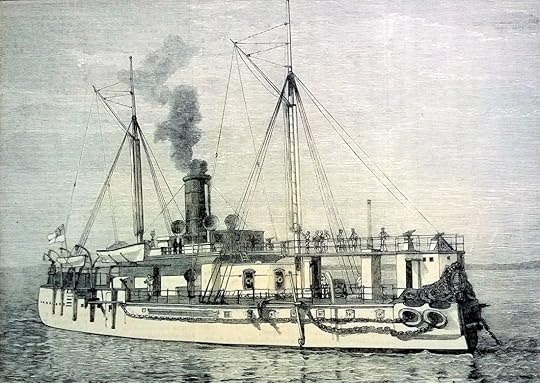

HMS Canopus – heavily armed but too slow to support Cracock

HMS Canopus – heavily armed but too slow to support Cracock

The British and German squadrons were now on a collision course and, given the disparity in strength, Cradock’s decision to advance seems almost inexplicable, the more so since he would lack HMS Canopus’s support. It was said later that he was “constitutionally incapable of refusing action”. Another explanation is that, knowing his mission was impossible, Cradock wanted to damage von Spee’s ships and to force him to use ammunition he could not replace.

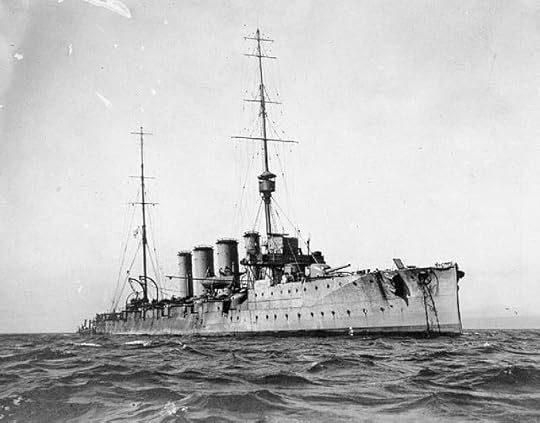

HMS Glasgow joined HMS Good Hope, HMS Monmouth and HMS Otranto early on November 1st, in seas too rough to allow inter-ship transfer, messages being sent across by line instead. In early afternoon Cradock deployed his ships in line of battle and at 1617 hrs the German squadron sighted British smoke. Von Spee took Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig ahead, leaving the slower Dresden and Nürnberg to follow.

Confronted by this overwhelming force, Cradock ordered a turn away so that both squadrons rushed south in a chase that was to last 90 minutes. The slow, 16 knot, Otranto was now Cradock’s millstone and he knew that he must choose between abandoning her and continuing to run south with Good Hope, Monmouth and Glasgow or to stand and fight to protect the useless converted liner. Cradock decided he must fight, and he accordingly drew his ships closer together, turning to the south-east to close with the German vessels while the sun was still high. Von Spee, meanwhile, was manoeuvring his force to ensure that the British ships to the west would be outlined against the setting sun.

Sharnhorst in action – note rough sea

Sharnhorst in action – note rough sea

Von Spee responded to Cradock’s manoeuvre by turning his own faster ships away, maintaining the distance between the forces at 14,000 yards as they steamed in parallel. Cradock now ordered the Otranto, which was too weakly armed to influence the outcome, to escape west at full speed. At 1818 hrs, with little daylight left, Cradock again tried to close, but von Spee once more turned away to open the range. The sun set at 1850 hrs and the British ships were now silhouetted against the last light in the west.

Von Spee closed the range to 12,000 yards and opened fire.

What followed was a massacre. The British 6-in weapons were outranged by the German 8.2’s and, when Cradock made another attempt to close, the German fire became even more devastatingly accurate. By 1930 hrs both Good Hope and Monmouth were on fire, easy targets for the German gunners now that darkness had fallen, whereas the German ships were shrouded in darkness. Monmouth’s guns fell silent but Good Hope continued firing until 1950 hrs when she too ceased fire, then exploded and disappeared. Scharnhorst maintained a merciless fire on Monmouth, while Gneisenau joined Leipzig and Dresden in engaging Glasgow. HMS Glasgow was still relatively undamaged but her captain turned away to escape in the darkness, recognising that continuing the battle would be futile.

HMS Glasgow – Cradock’s most modern ship

HMS Glasgow – Cradock’s most modern ship

HMS Monmouth, badly damaged, but still afloat, tried to run eastwards to beach herself on the Chilean coast. The Germans lost her temporarily in the darkness but the Nürnberg, the slowest of von Spee’s ships, found her. The German captain directed his searchlights on to Monmouth’s ensign in an invitation to surrender but she refused to do so. Nürnberg then opened fire reluctantly and sank her. Aware that Canopus might be somewhere in the vicinity von Spee turned north and the action ended.

HMS Good Hope on fire: painting by eminent marine artist William Lionel Wyllie

HMS Good Hope on fire: painting by eminent marine artist William Lionel Wyllie

All sea battles are horrible but Coronel seems particularly ghastly. The rough seas, the all but impotent British armoured cruisers being pounded with salvo after salvo, the darkness, the raging fires, Good Hope’s explosive end, the hope raised on Monmouth that she might yet survive, only to have it dashed, all combine to give the encounter a nightmare quality. There were no survivors from either Good Hope or Monmouth, 1,600 British officers and men, including Cradock, having been killed. Glasgow and Otranto both escaped, neither with fatalities. Two British shells, both duds, hit Scharnhorst, and four shells struck Gneisenau. Three German seamen were wounded. The greatest loss to von Spee was the expenditure of ammunition which could not be replaced. When his ships next faced British forces, as they would a month later at the Falklands, the German squadron would do so with depleted magazines.

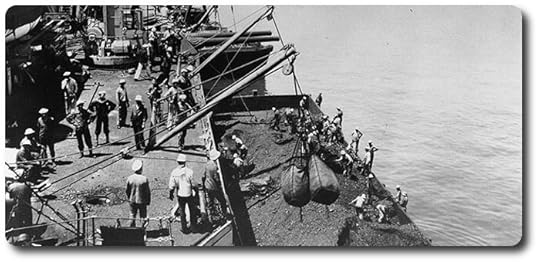

von Spee’s squadron in Valpariso Nov. 3rd 1914

von Spee’s squadron in Valpariso Nov. 3rd 1914

There also appear to be Chilean ships present, nearer the camera

Von Spee was aware that his victory would not be enough to save his squadron, far from home as it was and without German bases between. When, two days later, his squadron entered Valparaiso to the cheers of the German residents, he refused to join in the celebrations. Presented with a bouquet of flowers, he remarked “These will do nicely for my grave”.

Von Spee was aware that his victory would not be enough to save his squadron, far from home as it was and without German bases between. When, two days later, his squadron entered Valparaiso to the cheers of the German residents, he refused to join in the celebrations. Presented with a bouquet of flowers, he remarked “These will do nicely for my grave”.

The defeat at Coronel, the first surface action in over a century which the Royal Navy had lost, was both shocking and unexpected. Only by swift and total annihilation of von Spee’s squadron could the humiliation be avenged. Massive forces were sent south from Britain to ensure this – as they did a month later.

But that’s a different story!

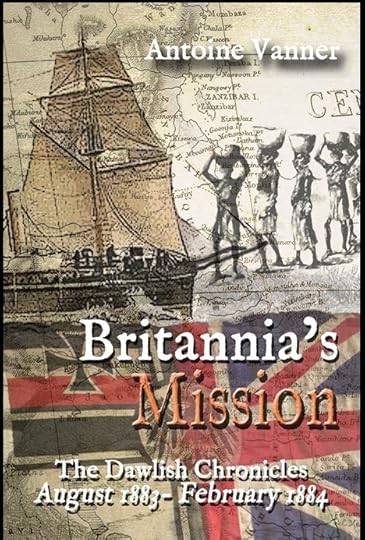

The young Imperial German Navy plays a key role in Britannia’s MissionThe eighth Dawlish Chronicle is published in paperback and Kindle, and is available to subscribers to Kindle Unlimited and Prime at no extra charge. It can be read in sequence or as a standalone.Click image for details or to order

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Click here for an 8-minute video in which Antoine Vanner talks about Britannia’s Mission

Six free short-stories are available for download to on your Kindle or iPhone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and it facilitates e-mail contact between Antoine Vanner and his readers.

The post Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914: Part 2 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 2, 2023

Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914 – Part 1

The Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914 – Part 1

The Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914 – Part 1The Battle of Coronel, the first defeat to be suffered at sea by Britain’s Royal Navy in a century, was fought in stormy seas and fading light off the coast of Chile and was to result in the loss of over 1600 men. The circumstances were dramatic – and tragic – in the extreme.

The tragic HMS Good Hope ( Attribution unknown – found on Pinterest)

Imperial German Navy ships stationed outside home waters at the outbreak of WW1 were in an unenviable position. German possessed only one fortified naval base overseas – at Tsingtao in China. The various German colonies around the world – Togo, Cameroon, South-West Africa, Tanganyika, Northern New Guinea and various Pacific island groups, could provide only limited coaling and maintenance facilities. Tanganyika held out – in a brilliantly conducted land campaign – until the end of the war but all other colonies were conquered by Britain and her allies in the opening months. As her coast was blockaded from the beginning, Tanganyika could provide no facilities to support naval operations.

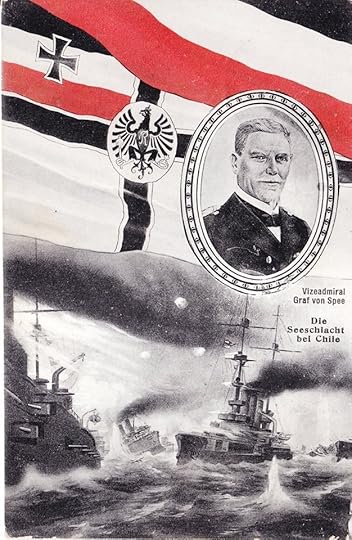

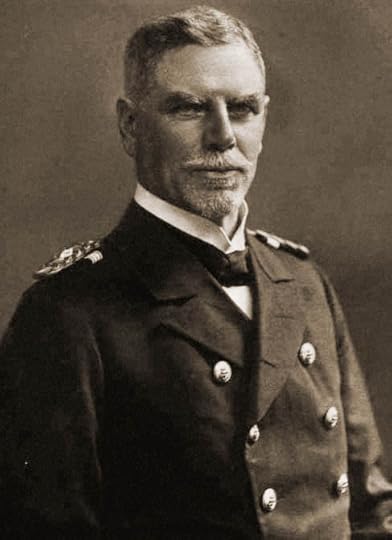

von Spee

Germany’s main overseas naval force was the East Asia Squadron, based in Tsingtao. Commanded in 1914 by Vice Admiral Maximilian, Reichsgraf von Spee, its main strength lay in two modern armoured Cruisers, the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and four modern light cruisers, Dresden, Emden, Leipzig and Nürnberg. There were a number of gunboats and a single destroyer, mainly for policing-type actions along the coast of China. Impressive as this force might seem, it was puny by comparison with the naval forces of Britain’s ally, Japan, which not only deployed large numbers of superb ships and manned them with seasoned professionals, but which nine years before had achieved the greatest naval victory in history up to that time. There were in addition British ships in the area, and the Royal Australian Navy’s flagship, the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, was alone superior to von Spee’s entire squadron.

When war broke out in August 1914 most of the warships of the East Asia Station were dispersed at various island colonies on routine missions. Von Spee recognised that Tsingtao could not be held indefinitely – the Japanese declared war on German in August 23rd, after which they joined Britain in a blockade and siege of the base. Von Spee accordingly ordered his ocean-going vessels to rendezvous at Pagan Island in the northern Marianas.

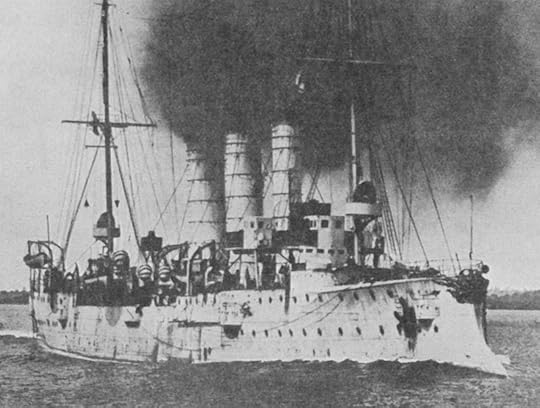

SMS Leipzig – other German light cruisers essentially similar

In conference with his commanders at Pagan, von Spee planned, probably with little expectation of success, a return across the world to Germany. The key factor would be coal supply by chartered colliers, which would have to meet the squadron at various points, their movements being coordinated by radio. Organising this, and making it happen operationally in the teeth of massive sweeps by the British and Japanese, was likely to be difficult in the extreme. The Emden was detached to conduct a separate – and very successful – campaign in the Indian Ocean (Click here to read an article about this). Von Spee was starved of news as all German undersea cables through British controlled areas had been cut, and radio capabilities were still very limited. The Nürnberg was therefore dispatched to Hawaii – neutral territory – to gather war news. Von Spee headed for German Samoa with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, then east, towards the French possession of Tahiti, where they made a brief bombardment. Reunited, the squadron coaled at Easter Island from German colliers.

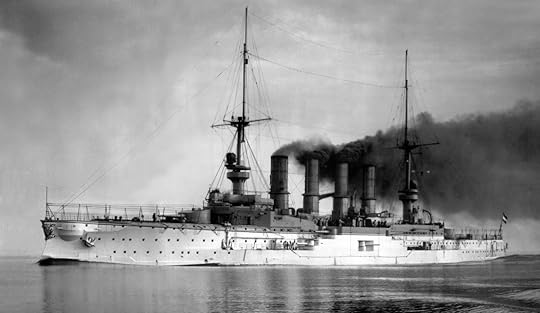

SMS Gneisenau, identical to her sister Scharnhorst, in pre-war ochre and white livery

SMS Gneisenau, identical to her sister Scharnhorst, in pre-war ochre and white livery

An obsolete cruiser SMS Geier, failed to make the rendezvous at Pagan, and had to intern herself at then-neutral Hawaii because of technical problems (Click here to read an article about her). Left behind at Tsingtao were four small gunboats Iltis, Jaguar, Tiger, Luchs and the torpedo boat S-90. This latter craft was to score a significant success by torpedoing and sinking the old Japanese cruiser Takachiho on October 29th. All these craft were scuttled prior to surrender of Tsingtao to the British and Japanese in November.

SMS S-90, Nemesis of the old Japanese cruiser Takachiho

SMS S-90, Nemesis of the old Japanese cruiser Takachiho

The British Admiralty made destruction of von Spee’s squadron a high priority. The futile German bombardment of Papeete, Tahiti, and the destruction of an old French gunboat there (wasting ill-afforded ammunition in the process) led the British to concentrate the search in the Western Pacific. This seems very unwise in retrospect since Japan, Britain’s ally, already had substantial forces in this area. It was only in early October that an intercepted radio message indicated that von Spee was heading for the west coast of South America to destroy British merchant shipping there.

Good Hope, soon after commissioning

Good Hope, soon after commissioning

Drawing by the eminent marine artist William Lionel Wyllie

The British squadron sent into the Pacific from the South Atlantic to counter such a move was almost wholly made up of obsolescent or poorly-armed vessels, crewed by naval reservists called back to service without time for refresher training. The force commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock consisted of the near-obsolete armoured cruisers HMS Good Hope (flagship), and HMS Monmouth, the modern light cruiser HMS Glasgow and a weakly-armed converted liner, the HMS Otranto. For heavy backup Cradock was assigned the slow, but powerfully-armed, pre-dreadnought HMS Canopus. In the event, the latter’s worn-out machinery made it impossible, despite heroic efforts by her engine-room crew, to keep pace with the cruisers.

HMS Monmouth

HMS Monmouth

Except for two individual 9.2-inch turret-mounted guns on HMS Good Hope, and four 6-inch similarly mounted on HMS Monmouth, the remaining twenty-six 6-inch weapons carried by the armoured cruisers were positioned in casemates built into the sides of the hulls. Some of these casemates were “two-storey” ones, with the lower positions inoperable in any significant seaway. This made a substantial portion of the armament essentially unusable and, as the weakness was so obvious – and must have been noticed during exercises – one wonders why naval architects persisted with this feature through successive design classes.

SMS Scharnhorst in peacetime – ( Attribution unknown – found on Pinterest)

By contrast, von Spee’s armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau each carried four 8.2-inch weapons in double-gun turrets and each ship’s six 5.9-inch weapons, though casemate-mounted, were higher above the waterline than on the British ships. The German 8.2-inch weapons were markedly superior as regards range and firepower and both vessels had proved themselves as “crack gunnery ships” in peacetime firing exercises. Add to this the superior German armouring and Cradock’s force can be seen to have been wholly outmatched. Though the light cruiser Glasgow was a superb new vessel, and individually superior to any one of her German counterparts, she was outnumbered by Dresden, Leipzig and Nürnberg.

The weakness of Cradock’s force was recognised, but the Admiralty seems to have placed excessive trust in the presence of the Canopus and the four 12-inch guns of her main armament. Cradock was told to use Canopus as “a citadel around which all our cruisers in those waters could find absolute security”.

Cradock

It is notable that both Cradock and von Spee were largely similar personalities – decent and honourable men who shared the same enthusiasm and dedication to their profession and who would have been good friends in other circumstances. There was a chivalry and delicacy about both of them that belonged to an age which had even by then almost disappeared. The Royal Navy was Cradock’s whole life – he never married – and he had said that his preferred death would be either in a hunting accident or during action at sea. A quote from book he wrote in 1908, “Whispers from the Fleet,” describes the operations of a cruiser squadron in near-poetic terms and prefigures, uncannily, the actual death which was to be so close to that he wished for:

“The Scene: – A heaving unsettled sea, and away over to the western horizon an angry yellow sun is setting clearly below a forbidding bank of the blackest of wind-charged clouds. In the centre of the picture lies an immense solitary cruiser with a flag – ‘tis the cruiser recall – at her masthead blowing out broad and clear from the first rude kiss given by the fast rising breeze. Then away, from half the points of the compass, are seen the swift ships of a cruiser squadron all drawing into join their flagship: some are close, others far distant and hull down, with nothing but their fitful smoke against the fast fading lighted sky to mark their whereabouts; but like wild ducks at evening flighting home to some well-known spot, so are they, with one desire, hurrying back at the behest of their mother-ship to gather around her for the night.”

In late October both the British and German forces were close to the coast of Chile, von Spee off Valparaíso and Cradock further south, but no contact had yet been made.

And there we’ll leave them for now, and in a blog next week we’ll learn of the tragic encounter that lay ahead.

Start the Dawlish Chronicles series with the chronologically earliest novel: Britannia’s InnocentTypical Review, named “The most thoughtful Naval adventure series, ever.”“Each of the Dawlish Chronicles is better than the last. Combines the action and adventure of Tom Clancy or Bernard Cornwell, with the sensibility of Henry James or Jack London. The hero perseveres in the face of adversity and remains true to his principles and evolving moral sensibilities: becoming more complete with each challenge. Not jingoistic, but a determined ethical man, who will fulfill his duty to the ends of the earth. I can’t wait for the next novel in this series! Thank you Mr Vanner for this fabulous hero placed so aptly into a backdrop of eminent Victorians.”

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting …Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle or iPhone. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and it facilitates e-mail contact between Antoine Vanner and his readers.

The post Battle of Coronel, November 1st 1914 – Part 1 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 28, 2023

HMS Leopard – USS Chesapeake Incident, 1807

The USS Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807

The USS Chesapeake – HMS Leopard Incident, 1807The three-year “War of 1812“between Britain and the United States, brought no great benefit to either nation. Though the issues involved were complex, one in particular, the British claim of the right to search neutral vessels for deserters from the Royal Navy, had the power to trigger American outrage and breathe new life into resentments that harked back to the War of Independence and before. Though it was not until 1812 that the United States declared war, the issue of recovering deserters had almost brought the two nations into conflict five years earlier, in what became known as the Chesapeake – Leopard Incident.

The action between HMS Leopard (r) and the USS Chesapeake (Drawing by Fred S. Cozzens)

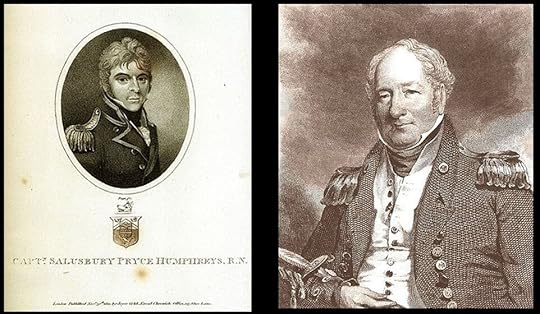

In 1807 news reached the British base at Halifax, Nova Scotia, that several Royal Navy deserters had been accepted into service on the American frigate USS Chesapeake. In what might be considered an over-reaction, the station commander despatched the 50-gun frigate HMS Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys (1778-1845), to bring orders to the captains of other vessels of the British squadron off the American coast. They were to insist on the right to search the Chesapeake for deserters should they fall in with her outside the territorial waters of the United States. In the event, it was HMS Leopard herself that was to make the demand.

Humphreys and Barron – the two captains whose lives were to be changed by their encounter

Launched in 1785, the 50-gun fourth-rate HMS Leopard (fourth rates occupied an ambiguous position between frigates and ships-of-the-line) had had a useful but undistinguished career since the outbreak of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. (She was to have a fictional as well as an actual career before her loss by grounding in 1814, for Captain Jack Aubrey was to command her in Patrick O’Brian’s novel Desolation Island.)

[image error]

USS Chesapeake – one of the US Navy’s original “Six-Frigates”

Having delivered her despatches, HMS Leopard was lying with the rest of the British squadron off the Hampton Roads when the USS Chesapeake was sighted on June 1st 1807, en route to the Mediterranean. The squadron commodore signalled HMS Leopard to detain her. The American captain, James Barron (1768-1851), did not appear to sense anything untoward – both nations were at peace. When HMS Leopard hailed to say that she carried message from the British commander-in-chief, Barron, replied “Send it on board—I will heave to.” HMS Leopard’s first lieutenant went across and when the matter of deserters was raised Barron stated that he had no such men on board.

Chesapeake’s reply to Leopard

After the lieutenant had returned to the Leopard, Captain Humphries again hailed the Chesapeake. He did not consider the answer satisfactory and saw that there were signs of preparation for action on the American ship. To emphasise his demands he now ordered a shot to be fired across her bow. He continued firing at two-minute intervals. Increasingly frustrated by what he considered evasive answers from Barron, which he thought were only to gain time, he at last ordered fire to be opened in earnest. After receiving three broadsides, and after replying with only a few shots, the Chesapeake struck her colours. An American lieutenant came across with a verbal message from Barron, stating that he considered his ship to be HMS Leopard’s prize.

Captain Humphries did not accept the Chesapeake as a prize but he did send two of his lieutenants across, with several petty officers and men, to search for the deserters. One seaman, who was dragged out of the coal-hole, was recognised as Jenkin Ratford, a deserter from HMS Halifax. Three others were found, who had deserted from HMS Melampus, and about twelve more from various British warships. The first four were however to only ones to be brought across to the Leopard. Now – and quite bizarrely – Barron again offered to deliver up the Chesapeake as a prize. Captain Humphreys told him however that he had fulfilled his own instructions and that the American ship was free to proceed. He regretted having been compelled to attack and offered all the assistance in his power.

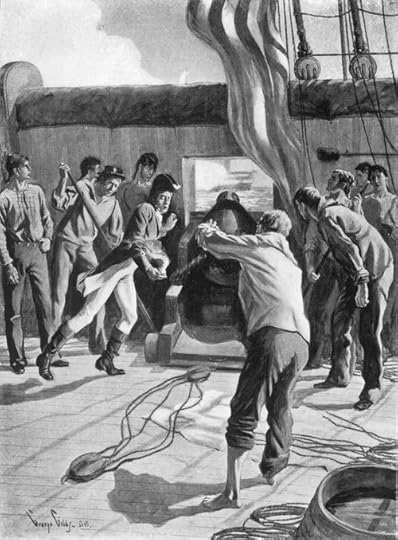

Barron tries to surrender USS Chesapeake as a prize

The Chesapeake had suffered severely from HMS Leopard’s broadsides. Twenty-two shot were lodged in her hull and her masts and rigging were badly damaged. She had lost three seamen killed, while Barron, one midshipman, and sixteen seamen and marines had been wounded. Since the Chesapeake was all but unready for battle, Barron’s unwillingness to continue the engagement was understandable if not necessarily heroic.

When HMS Leopard arrived at Halifax, the unfortunate Jenkin Ratford was found guilty of mutiny and desertion, and was hanged at the foreyard-arm of the ship from which he had deserted. The three other men, though found guilty of desertion, were initially sentenced to 500 lashes, but they had their sentence commuted and were later allowed to return to America.

It was inevitable that the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair would trigger outrage and demands for war in the United States. Protracted diplomatic negotiations failed to reach a mutually satisfactory outcome – Britain indeed reaffirmed its claim to right of impressment. As a sop to American feeling however, Captain Humphreys of HMS Leopard was given no further commands. The United States backed off from declaring war but President Thomas Jefferson resorted to economic warfare by means of a trade embargo that was aimed as much against France as against Britain.

The career of James Barron of the Chesapeake was also ruined. He was court-martialled in January 1808 on the charge of not having his ship ready for action and he was suspended for five years without pay. Though this ended in 1812, the Navy refused his requests to be accepted back for service during the war that began that year. One of the members of the court was Stephen Decatur (1779 –1820) and Barron appears to have held a grudge against him thereafter. Bad blood between the two men escalated to the extent of Barron challenging Decatur, now a national hero, to a duel with pistols in 1820. Both men were hit and badly wounded. As they were carried from the field Barron called out “God bless you, Decatur” and Decatur replied in a weak voice “Farewell, farewell, Barron.” Decatur died of his wound but Barron survived. It was a sad and futile postscript to the Leopard – Chesapeake affair.

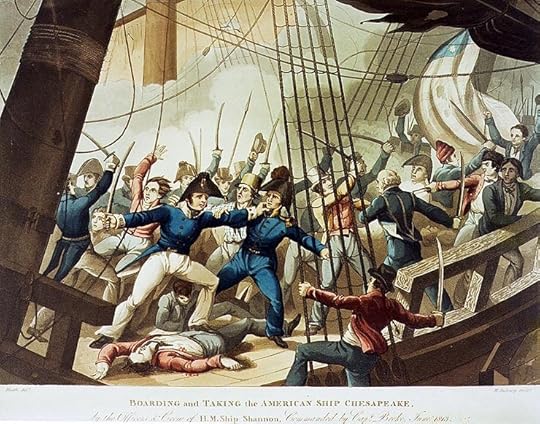

Contemporary print: HMS Shanon’s crew boarding USS Chesapeake in 1813

By that time USS Chesapeake herself was a thing of the past. She was captured by HMS Shannon after an epic duel on June 1st 1813, exactly six years after her encounter with HMS Leopard. Taken into Royal Navy service as HMS Chesapeake, was broken up in 1819. Some of her timbers are now incorporated in the structure of the Chesapeake Mill emporium in Wickham, Hampshire.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamIf you are a subscriber to Kindle Unlimited you can read all eleven volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post HMS Leopard – USS Chesapeake Incident, 1807 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 21, 2023

HMS Alexander at bay, 1794

HMS Alexander at bay, November 1794

HMS Alexander at bay, November 1794

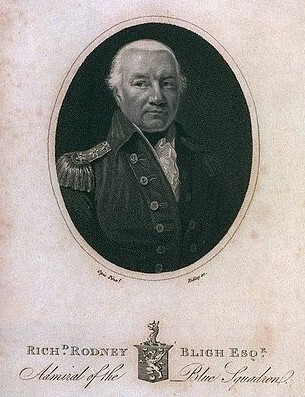

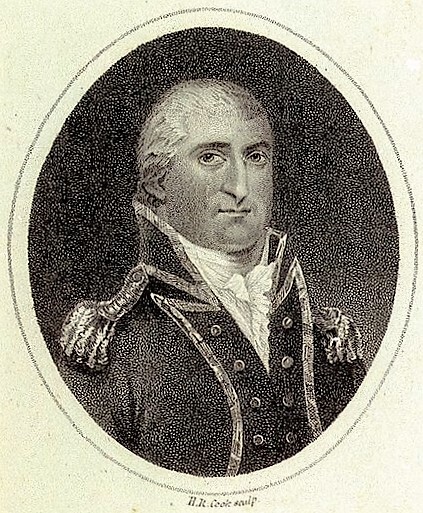

Richard Bligh as Admiral

Captain William Bligh – “Bligh of the Bounty” – is one of the best-remembered officers of the Age of Fighting Sail, not only because of the loss of his ship through mutiny but for his 3618-mile, 47-day voyage to safety in an open boat, an epic of navigation and leadership. There was however another Bligh – William’s third cousin – whose memory also deserves to be honoured. This was Captain (later Admiral) Sir Richard Rodney Bligh (1737 –1821) whose career had begun as early as the Seven Years War, when he had served with the doomed Admiral Byng in the failed attempt to capture Minorca in 1756. He served with distinction during the rest of that war, and in the American War of Independence 1775-82. By the time France declared war on Britain in 1793 – thus starting what would be the two decades of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars – Bligh, now a captain, was in command of HMS Excellent, a “74” ship-of-the-line. He was transferred the following year to command another 74, HMS Alexander. In her, he was to fight one of the most unequal battles of the era. HMS Alexander was typical of the 74s, the class that formed the backbone of Britain’s naval power, and was armed on the broadside with twenty-eight 32-pounder sand an equal number of 18-pounders, while some eighteen 9-pounders were mounted as chaser weapons fore and aft.

The launch of HMS Alexander at Deptford, 1778 – she is seen on the stocks in the background. Note large numbers of small boats with spectators. Painting by John Cleveley the Younger (1747-1786) – Public Domain, thanks to Wikipedia

On 6th November 1794, off Brittany, Bligh in HMS Alexander, together with another 74, HMS Canada, was returning to Britain after escorting an outbound convoy. Around three o’clock in the morning, other ships were detected in the vicinity and passed as close to them as was estimated to be half a mile. Unsure of their nationality, but fearing the worst, Alexander and Canada bore up, shook the reefs out of their topsails, and set their studding-sails. This caution proved wise for as daylight dawned the other vessels proved to be a very powerful French squadron, consisting of five ships-of-the-line, three frigates and a brig, which now initiated a chase. The best chance of saving Canada, Alexander or both from falling into the enemy’s hands was to split up in the hope that the enemy force would also divide. Crowding all the sail they could carry, the two British each steered a different course. This resulted in two of the French ships-of-the-line and two frigates chasing HMS Canada, while three ships-of-the-line and two frigates went in pursuit of HMS Alexander.

Canada managed to escape but HMS Alexander was cornered after a five-hour chase. She was now faced with overwhelming odds as the entire French force concentrated on her, HMS Canada’s pursuers also having turned back to join the battle. HMS Alexander was pounded mercilessly for the next three hours, returning fire the whole time. At last, his vessel almost a complete wreck, Bligh requested his officers’ opinion on whether resistance should be maintained. The consensus was that she was too badly damaged for this. In Bligh’s later words “Then, and not till then, painful to relate, I ordered the colours to be struck.”

HMS Alexander, surrounded, shortly before striking her colours. Painting in public domain according to Wikipedia

Despite the punishment HMS Alexander had taken, the casualty list was surprisingly low – some 40 dead and wounded. The explanation may have been that the French, as often their practice, had concentrated their fire on masts and rigging to prevent escape while doing minimum damage to the hull. The French loss and damage must have been much more severe, as the whole squadron was obliged to quit their cruising ground and to return to Brest for refitting.

The aftermath did the French no credit and showed none of the consideration usually shown by chivalrous foes to defeated antagonists in previous wars, or indeed later in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. This may have reflected the need for French officers as well as seamen to display ostentatious revolutionary contempt for established norms. The Reign of Terror had only recently ended, the shadow of the guillotine hung over anybody whose fervour was suspect and whose chivalry was, for now at least, out of fashion. It is possible that it was dedication to the ideal of “Equality” that led to HMS Alexander’s officers and men being confined together once they were taken ashore and provided with the bare minimum of food. So serious did their hunger become that an unfortunate dog they found was killed and eaten by them. One prisoner, in a state of delirium, threw himself into the prison’s well and his dead body was left there for some time before being removed. This well remained the only available source of drinking water afterwards. Even worse was that an English lady and her daughters (possibly tourists who had not got out in time when the war started?) were confined along with the men. A subsequent account noted that “all their privacy was supplied by the generous commiseration of the sailors, who, standing side by side close together, with their backs towards their fair fellow captives, formed a temporary screen while they changed their garments.”

The Battle of Groix, 23rd June 1795, in which Alexander was recaptured from the French. Two other ships of the line were taken, Formidable (90 guns) and Tigre (74) and entered Royal Navy service afterwards.

The Battle of Groix, 23rd June 1795, in which Alexander was recaptured from the French. Two other ships of the line were taken, Formidable (90 guns) and Tigre (74) and entered Royal Navy service afterwards.

Bligh – who, unknown to himself, had been promoted to Rear Admiral a fortnight before the action – returned to Britain as part of a prisoner exchange six months later. He was required to undergo the inevitable court-martial for the loss of his ship but, equally inevitably, he was acquitted, with honour. He remained in active service until 1804, retiring as a full admiral.

The French flagship Orient at the Battle of the Nile. HMS Alexander was one of the vessels that took her under fire. Her end was to come in a spectacular explosion (Painting by Thomas Luny 1759 – 1837)

The French flagship Orient at the Battle of the Nile. HMS Alexander was one of the vessels that took her under fire. Her end was to come in a spectacular explosion (Painting by Thomas Luny 1759 – 1837)

Heavily damaged though she had been, HMS Alexander also had an active career ahead. Repaired, she was brought into French service as the Alexadre but was retaken by the Royal Navy in the Battle of Groix a scant seven months after Bligh’s action. Once more HMS Alexander, she was to have her moment of glory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, engaging the flagship, L’Orient, as well as other French ships.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamIf you are a subscriber to Kindle Unlimited you can read all eleven volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post HMS Alexander at bay, 1794 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 7, 2023

A Franco-Prussian Battle off Havana, 1870

The Franco-Prussian Battle of Havana, 1870

The Franco-Prussian Battle of Havana, 1870The Prussian navy, a weak force composed mainly of gunboats, played an insignificant, if sometimes heroic, role in the three wars that led to proclamation of the German Empire in 1871. These were against Denmark (1864), Austria, Bavaria and other German States (1866) and France (1870-71). Small as it was, the Prussian Navy has a significant role in the earliest chronologically of the Dawlish Chronicles novels, Britannia’s Innocent, which plays out against the background of the Danish War. It is however with an incident in the later Franco-Prussian War that this blog is concerned, focussing on an action fought off Cuba: the small-scale but intense Battle of Havana in 1870. Single-ship actions, in which a lone ship from one navy is matched against a lone ship of the enemy’s, represent some of the most dramatic battles in naval history. The captains and crews cannot depend on support or rescue through the intervention of a larger force and the battle represents the moment in which training, skill and discipline all come together to determine victory or defeat. Some of the most dramatic of such actions – Quebec vs Surveillante (1779), Indefatigable vs. Droits de l’Homme (1797) and Shah vs. Huascar (1877) – and the Naval War of 1812 consisted largely of similar encounters. Each of these actions took place in the context of larger tactical or strategic objectives.

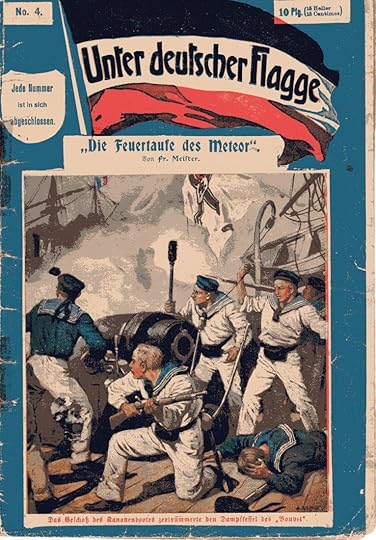

.The Battle of Havana, November 9th 1870. A card issued by a margarine manufacturer – SMS Meteor on left

.The Battle of Havana, November 9th 1870. A card issued by a margarine manufacturer – SMS Meteor on left

By contrast, the more obscure 1870 Battle of Havana was one which was radically different to these, in that it could have had no bearing, however remote, on the outcome of a greater conflict. It was indeed triggered by almost medieval concepts of pride and honour. In 1870 the French Second Empire, under the rule of Napoleon III, entered unwisely into war with Prussia, the pre-eminent power in Germany. Within weeks of the start of hostilities French land forces had been defeated in battle after battle. Napoleon III himself had been surrounded and forced to surrender with an entire army and Prussian forces, supported by other German allies, had invaded Northern France and had brought Paris itself under siege. France had a large navy, Prussia a few ships only, and those small, but the French found themselves incapable of using their powerful modern ironclads to gain any strategic advantage.

After French surrender at Sedan, Prussia’s chancellor, Bismarck (right) comforts defeated Emperor Napoleon III

After French surrender at Sedan, Prussia’s chancellor, Bismarck (right) comforts defeated Emperor Napoleon III

By November 1870, as winter came, siege conditions inside Paris were beginning to bite. Food was running short (even elephants in the zoo were eaten) and political upheaval had resulted in proclamation of a republic. Without agreement by various hostile factions as to what this meant, attempts at breakout by the defenders and of relief by other French forces were unsuccessful. Communication with the outside world was by balloon only. Elsewhere in France efforts were being made to regroup whatever forces had so far escaped defeat – futile efforts which in turn were to lead to yet further defeats.

While Metropolitan France was enduring this agony, a wooden-hulled French sloop of the three-ship Guichen class, the Bouvet, was serving in the more idyllic surroundings of the French West Indies. Launched five years earlier, of 750 tons and 182 feet long, she carried auxiliary sails to complement the 575 hp steam engine that gave her, at best, 10.7 knots. Like many similar vessels in other navies, she was intended for “colonial service” only, with shore bombardment of unsophisticated enemies her most likely hostile duty. This said, she was heavily armed for her size – one 6.4” and four 4.7” guns.

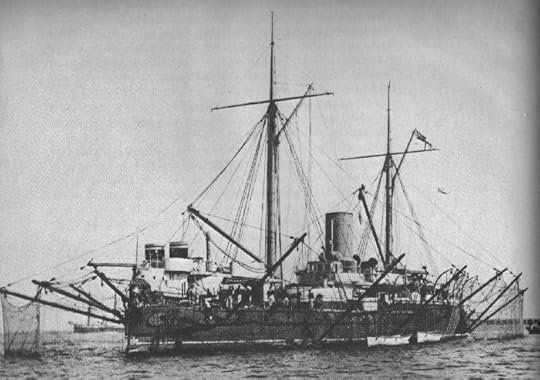

SMS Meteor

SMS Meteor

Also in the area was the Prussian gunboat Meteor of the eight-ship Chamaeleon class. She too was wooden-hulled, of 415 tons and 142 feet long. She carried sail as well as steam – a 320 hp engine urged her to just over 9 knots maximum. She was more weakly armed than the French Bouvet, carrying only one 24 pounder and two 12 pounders. On November 7th the Meteor steamed into Havana, then the capital of what was still the Spanish-ruled colony of Cuba. The Bouvet arrived from Martinique a few hours later. Both ships moored and it is easy to imagine the suspicion with which their crews viewed each other. They were however in a neutral port and no offensive action could be undertaken. Also in the harbour was a French mail steamer, the Nouveau Monde. On the following day the Nouveau Monde left Havana, en route for Veracruz in Mexico. Fearing however that the Prussian Meteor might emerge, overtake and capture her, the mail steamer’s captain appeared to lose his nerve and he returned to Havana. The Meteor’s potential as a commerce raider had been recognised – but to realise it she had to get away from Havana, and that meant neutralising the Bouvet. Events now took a turn that seemed to belong more to the days of chivalry than to those of total war in which Prussia and France were already locked. The Meteor’s captain issued a formal challenge to the captain of the Bouvet to fight a battle – not indeed a wise move since the Meteor was heavily outgunned and as both ships were evenly matched as regards speed, making flight unlikely if defeat threatened. The Bouvet duly accepted the challenge and she left Havana to wait for the Meteor outside Cuban/Spanish territorial waters. Since Spain was not a party to the conflict, internationally-recognised neutrality conventions demanded that the Prussian warship had to wait another day before she could leave harbour,

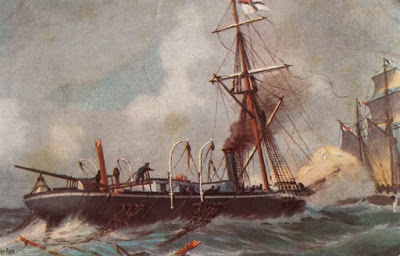

The Bouvet (right) pounds the Meteor

The Bouvet (right) pounds the Meteor

Meteor– 1911 image

The Meteor duly steamed out from Havana on November 9th. She headed towards the Bouvet, which was waiting 10 miles offshore, just outside the Spanish/Cuban territorial waters. The French opened fire immediately and the Prussian vessel returned it. The action, at very close range, lasted upwards of an hour and the Meteor, not surprisingly, got the worst of it, losing both main and mizzen masts. The Bouvet now moved in to finish the job by boarding but, at the critical moment, a steam pipe was damaged, leaving her dead in the water. Had the Meteor been more heavily armed, this might have been her opportunity to destroy the Bouvet. The French did however succeed in getting their ship into neutral Spanish territorial waters under sail and the struggle could no longer be continued. (This is perhaps the only instance of sail power proving of utility under battle conditions with a steam-powered warship).

SMS Meteor – dismasted and damaged, but still full of fight

Though both ships survived the encounter, the Bouvet was to come to an equally dramatic end some ten months later when she was wrecked near Haiti. Inconclusive as it was, and without any potential to influence the outcome of the main conflict, the Battle of Havana was one of the few naval encounters of the Franco-Prussian War. It was however of great symbolic significance to the Prussians – who within three months, and with the support of their other German allies, were to proclaim the establishment of the new German Empire – the Second Reich. Humiliatingly for the French, the proclamation was to take place in Louis XIV’s huge palace of Versailles. A fledgling navy had stood up to a larger and longer established one and it had held its own. The courage of the Meteor’s crew had served notice to the world that, however small its naval power might still be, Germany had the determination and skills to make her a force to be reckoned with at sea in the future. And the rest is history…

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post A Franco-Prussian Battle off Havana, 1870 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 17, 2023

The Heroic Schooner Betsey 1805

THE EPIC OF THE SCHOONER BETSEY, 1805

THE EPIC OF THE SCHOONER BETSEY, 1805Some time ago I came across a book – undated, but clearly late 19th Century – entitled “Thrilling Narratives of Mutiny, Murder and Piracy”. It was published in New York, though the author is not named. It is however a treasure house of accounts of obscure maritime events. One of the most remarkable describes the loss of the schooner Betsey in 1805. I’ve found no other references to the case, other than a very brief mention in Wikipedia. The privations of the Betsey’s crew would make a good movie, rather like The Heart of the Sea.

The classic perception of a schooner – trim, elegant and practical. The Betsey may have looked more mundane than in this painting: Topsail schooner Amy Stockdale off Dover – by William John Huggins (1781-1845)

The classic perception of a schooner – trim, elegant and practical. The Betsey may have looked more mundane than in this painting: Topsail schooner Amy Stockdale off Dover – by William John Huggins (1781-1845)

The Betsey was a small British schooner of about 75 tons and in November 1805 she departed from the Portuguese colony of Macao, on the Chinese coast, bound for the settlement of New South Wales. Other than her captain, William Brooks, and the mate, Edward Luttrell, none of the other eight crew members were British – one was Portuguese, three Filipino and four Chinese. By November 21st the Betsey had reached a point in the South China Sea about 270 miles West of Palawan, and about the same from the Northern tip of Borneo. Here, in the early hours of the morning, she ran on to a reef. An attempt was made to drag her off by sending a boat astern to drop an anchor. When hauling, the cable parted, resulting in both cable and anchor being lost, but no lives. With destruction of the ship now a distinct possibility the crew worked on through the hours of darkness on construction of a raft from water casks – the boat appears to have been too small to accommodate the entire crew. According to the book’s account, “the swell proved so great that they found it impossible to accomplish their purpose.” All the time the weather was driving the damaged vessel onward across the reef – as far, as was estimated, as some five miles. At last lodged at a point where the water was only two feet deep, further attempts over the next three days and nights to free her proved futile.

A small vessel at risk in a large sea – as was the Betsey’s plight. (Aviazovsky Painting)

A small vessel at risk in a large sea – as was the Betsey’s plight. (Aviazovsky Painting)

There was no option now but to take to the boat and to the raft that had at last been completed. The intention was to head for the island of Balambangan, off the northern tip of Borneo. Captain Brooks, Luttrell the mate and three others were in the boat – with a bag of biscuits between them – while the remainder of the crew were on the raft. Soon after leaving the Betsey a gale arose from the north-west and the boat lost sight of the raft, which was never seen again. The gale continued for another three days “accompanied by a mountainous sea.” By this time the boat had run out of fresh water and the remaining biscuit was saturated with seawater. This forced Brooks and his group to resort to the measure which was often essential in such cases to drink their own urine. The storm had one advantage – it had blown the boat south eastwards so that on November 29th the cost of Borneo was sighted but it was not until dawn the following day that they managed to land.

The first objective was fresh water – luckily soon found – and while hunting for food they encountered two “Malays”. (One assumes that these were people of one of the indigenous tribes – nineteenth century accounts are seldom specific on such points). These two returned in the afternoon with two coconuts and a few sweet potatoes, which they exchanged for a silver spoon. Brooks and his group remained with their boat on the beach through the night but the next morning five more Malays appeared with more food to exchange for spoons. (One is impressed by Captain Brooks’ foresight in bringing the schooner’s cutlery with him).

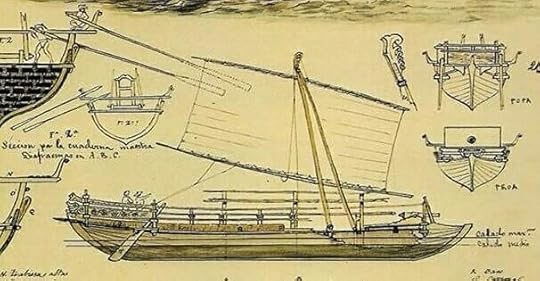

Malay Proa – 19th Century Drawing

Malay Proa – 19th Century Drawing

The next group of Malays to appear – eleven in total – were less friendly and mounted an attack. Captain Brooks received a spear thrust in his stomach – the weapon lodged there – but the mate Luttrell managed to hold off his own assailant with his cutlass and ran to the boat. Captain Brooks managed to drag out the spear and also tried to run but he was overwhelmed and both his legs were cut off by the attackers. Another crew member – identified as “the gunner” was also badly wounded but managed to reach the boat. The survivors pushed her out and saw Brooks’ body being stripped. A sail was raised but shortly afterwards the gunner also died.

“A Piratical Proa in Full Chase”: 19th C illustration by Charles Ellms. Luttrell may have been attacked by something similar.

“A Piratical Proa in Full Chase”: 19th C illustration by Charles Ellms. Luttrell may have been attacked by something similar.

Course was now set for the Straits of Malacca where friendly shipping might be encountered – this was still some thousand miles away and the provisions consisted of ten corncobs, three pumpkins, and two bottles of water. Progress for the next ten days was good and showers provided fresh water. The survivors were however badly weakened by exposure and hunger. By December 15th they had reached islands off the coast of Sumatra and were immediately attacked by two proas – fast Malays outrigger sailing craft. (The general area was to remain a hotbed of piracy for decades to come.) One of the Betsey’s seamen was run through with a spear and died instantly, while another was wounded. Luttrell, the mate, had a very narrow escape from a spear piercing his hat. Now prisoners, Luttrell and one other survivor were taken in three days to “an island called Sube” (which I have been unable to identify – names having changed so much over the years).

The Rajah of Simalungun, Northern Sumatra in early 20th Century – the Betsey’s crew’s captors would have looked similar. (With thanks to the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, part of the National Museum of World Cultures)

The Rajah of Simalungun, Northern Sumatra in early 20th Century – the Betsey’s crew’s captors would have looked similar. (With thanks to the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, part of the National Museum of World Cultures)

They were handed over to the local rajah, who kept them prisoners, fed only on sago, for the next four and a half months. In late April 180s the Rajah decided to release them and had a proa take them to the Riau Islands (just south of modern Singapore, which would not be founded for another thirteen years). Here they were handed over to a “Mr. Koek of Malacca”, who could have been a Dutch trader – no further details are given in the book. The rajah’s motivation for releasing the two men is not clear – he did perhaps fear retaliation by Royal Navy vessels if the continued detention got heard of.

Mr. Koek treated Luttrell and the other survivor “in the kindest manner” and they were then carried on to the trading centre of Malacca by a British ship, the Kandree. Thereafter they disappear from history.

If any reader can fill in some of the blanks in this remarkable story – a small epic – I would be glad to hear from them. Brooks, Luttrel and their companions were indeed iron men and worth remembering.

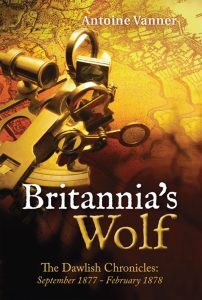

Britannia’s Wolf The Dawlish Chronicles: September 1877 – February 1878 The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The war is reaching its climax and aA Russian victory will pose a threat to Britain’s strategic interests. To protect them an ambitious British naval officer, Nicholas Dawlish, is assigned to the Ottoman Navy to ravage Russian supply lines in the Black Sea. In the depths of a savage winter, as Turkish forces face defeat on all fronts, Dawlish confronts enemy ironclads, Cossack lances and merciless Kurdish irregulars, and finds himself a pawn in the rivalry of the Sultan’s half-brothers for control of the collapsing empire. And in the midst of this chaos, unwillingly and unexpectedly, Dawlish finds himself drawn to a woman whom he believes he should not love. Not for her sake and not for his . . .

Available in paperback and Kindle.Amazon Prime subscribers read on Kindle at no extra cost.The Audiobook can be downloaded for free as an Audible trial.Click below for details and ordering in any format.For US & Canada For UK and Europe For Australia and New ZealandBelow are the eleven Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the image-block below for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post The Heroic Schooner Betsey 1805 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 3, 2023

HMS Hector 1782

Inman in later years

Captain Henry Inman (1762 –1809), a noted frigate commander who was in overall command of operations off Dunkirk in 1800 in which the French frigate Désirée was captured in dramatic circumstances. This ship was commissioned into the Royal Navy and Inman was to command her at the Battle of Copenhagen in the following year. Though a man of great ability, Inman’ was to be one of those tragic men whose careers were to be dogged by ill health and he died before achieving his full potential. His most impressive single achievement was however in his youth – he was only twenty years old at the time – and it was characterised by leadership and seamanlike skills of the highest order. This was when he brought HMS Hector through a nightmare of battle and shipwreck – without him, some 200 lives might almost certainly have been lost.

The Battle of the Saintes, April 1782 – by Thomas Whitcombe (1763-1824)

Promoted to lieutenant in 1780, Inman had already survived two separate shipwrecks. He was on shore duty in the West Indies in April 1782 and thereby missed participation in the large fleet action, The Battle of the Saintes, off Dominica . This had culminated in a crushing British victory over the French. In the course of this engagement, the French “74” line-of-battle ship Hector was captured. Though badly damaged in the action she was commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Hector. Under the command of Captain John Bourchier (approx. 1755 – 1819) she was ordered to return to Britain. Henry Inman joined her as First Lieutenant. Getting the battered HMS Hector seaworthy for the Atlantic crossing involved removal of 22 of her guns and replacement of her masts with shorter ones, presumably so as not to over-strain her hull. Her crew was significantly short-handed, some 300 men, many of whom were invalids. In normal circumstances, a ship of this size would carry a crew of 500 to 700 men and it is therefore obvious that her fighting ability was very seriously impaired. She sailed in late August, none on board suspecting that she would have to survive a violent hurricane that was to spell doom for other survivors of the Saintes Battle and killed over 3500 men.

A French frigate by Antoine Roux (1765-1835 ) – L’Aigle and Gloire would have looked similar

Before the unanticipated hurricane, another enemy had to be confronted. On the evening of September 5th HMS Hector was found by two 40-gun French frigates, L’Aigle and Gloire. These fresh, undamaged vessels quickly perceived HMS Hector’s decrepitude and one placed herself on her beam, and the other on her quarter and began to pour fire into her. Poorly manoeuvrable, HMS Hector was badly placed to avoid several rakings but she returned fire sufficiently to damage both attackers. It was a very creditable performance for a ship so weakly manned and armed. Even so, had the French vessels continued the bombardment from a distance they might have sunk HMS Hector. Instead they made the mistake of attempting to board and their efforts were bloodily repulsed. The action was broken off after six hours and both French ships bore off. (They were to be captured by a British force off the Delaware coast a week later – the damage sustained in the conflict with HMS Hector quite possibly a contributory factor).

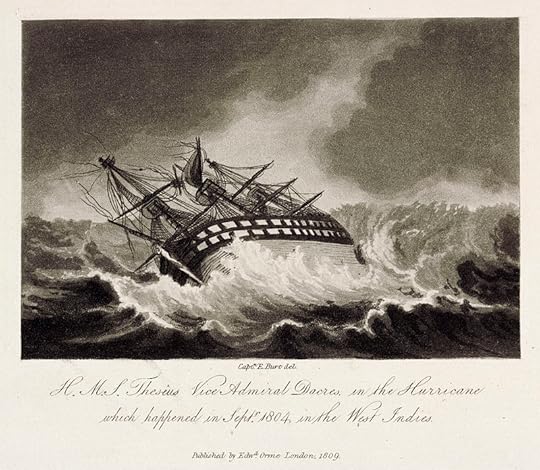

The “74” HMS Theseus surviving a hurricane in 1804

HMS Hector’s plight would have been even worse as she had lost both masts and rudder

Hector’s survival had been dearly bought. 46 of her crew had been killed or wounded, an especially serious concern when so many of her complement were already invalids. Captain Bourchier had been so badly wounded as to be incapacitated and effective command now passed to the twenty-year-old Henry Inman. The ship herself had been weakened yet further – the hull had sustained more injury, as had the masts, rigging and sails.

“All Hands to the Pumps” 1889

by Henry Scott Tuke

It was in this state that HMS Hector was to encounter the massive hurricane that swept through the Central Atlantic on September 17th. Battered by high seas, she lost her rudder and all her masts. Leaks were sprung and incoming water reached a level at which a major portion of the provisions and fresh water was spoiled. Survival now became a matter of continuous pumping, a labour that demanded physical exertion on an open wind and spray-lashed deck which would have been severe for a fit and healthy crew, but almost impossible for one so debilitated. The pumping ordeal was to last two weeks, with Inman – himself driven to the limits of exhaustion – needing at times to resort to the threat of his pistols to keep men at the task. Many appear to have died from fatigue while those who had finished their turns had no energy to do other than lie, washed over by surging water, in the scuppers. Despite these efforts, the water level was still rising inside the stricken hulk. Men already sick were dying daily and in the last four days of these two weeks the ship was without drinking water even as the hull structure began to disintegrate.

It was at this extremity, when hope was all but abandoned, that a sail was spotted. This was the tiny snow Hawke, of Dartmouth, Devon, under the command of a Captain John Hill. Though the seas were still high Hill brought her alongside HMS Hector, remained with her through the night, and in the morning commenced transfer of the survivors, now only some 200 in total, including the wounded Captain Bourchier. Henry Inman remained on HMS Hector until the last man had left. She sank ten minutes after he reached the Hawke.

A naval snow, 1759, by Charles Brooking

The figures on deck give an idea of just how small a craft such a vessel was

The situation was now only slightly less desperate. The Hawke was small – it is unlikely that she would have been longer than 100 feet – and to make room for Hector’s survivors necessitated dumping much of her cargo overboard. Even at that, she was so grossly overcrowded, and the extra weight taken on gave such concern for stability, that Hill and Inman had to enforce orders regarding how many men could be on deck at any one time. Food was quickly depleted, despite rationing, and the water allowance was only a half pint per man per day. Despite this caution, only a single cask of fresh water remained when land was sighted close to St. John’s, Newfoundland.