Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 7

July 7, 2023

A splendid restoration – China’s Zhongshan Gunboat

China’s Zhongshan Gunboat – a splendid restoration

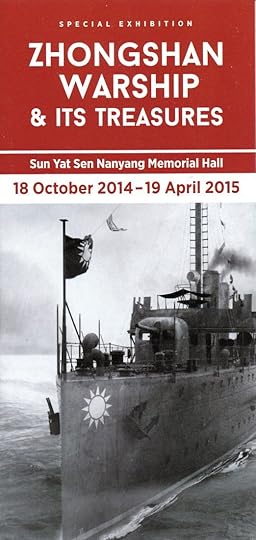

China’s Zhongshan Gunboat – a splendid restoration I was in Singapore in 2014 and on my way from the airport to the hotel I saw a large banner-like announcement for an exhibition entitled “The Zhongshan Warship” and its treasures. I had not previously heard of this vessel but I was very keen to learn more. I found the exhibition of great interest, relating as it did to China’s Zhongshan Gunboat, which played a significant historical role, and in this blog I’d like to share something about it.

I was in Singapore in 2014 and on my way from the airport to the hotel I saw a large banner-like announcement for an exhibition entitled “The Zhongshan Warship” and its treasures. I had not previously heard of this vessel but I was very keen to learn more. I found the exhibition of great interest, relating as it did to China’s Zhongshan Gunboat, which played a significant historical role, and in this blog I’d like to share something about it.

The exhibition – a travelling one – was organised by the Zhongshan Warship Museum of Wuhan, China, and was held in the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall Museum. This was formerly the residence of one of Singapore’s most successful Chinese merchants and philanthropists of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The museum covers not only the life of Sun Yat Sen (1866-1925), the revolutionary who brought about the fall of the Manchu (Qing) Dynasty in 1911 and who created the Chinese Republic that followed, but it also tells the story of the rise of the great Chinese business empires centred on Singapore. Sun’s story is dramatic in the extreme and I was not previously aware of what a large role was played in the revolution by the Overseas Chinese communities as regards funding and provision of support for political exiles and activists. The museum is splendidly housed and the organisation and range of exhibits make it a model of its kind. It is a must for any historically-minded visitor to Singapore.

The presence of the Zhongshan exhibition at the museum was explained by the fact that the vessel, named after Sun Yat Sen (his name in Mandarin being Sun Zhongshan), was strongly associated with him, as well as with a number of other significant events in the years 1911-1937.

The Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, Singapore

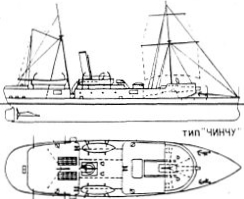

Initially called the Yongfen, the Zhongshan was one of two gunboats ordered by the Qing Imperial Government in 1910. They were built at the Mitsubishi yard at Nagasaki and their specifications were as follow:

Displacement: 830 Tons

Dimensions: 205 ft. long, 29.5 ft. beam and 15.3 ft. draught

Crew: 108-140

Armament: 1 X 105 mm at bow, 4 X 47 mm along sides, 1X 40 mm at stern

(2 X 39 mm Anti-Aircraft weapons added in 1920s/30s)

Machinery: 1350 hp triple expansion, twin screws, max speed 13.5 knots.

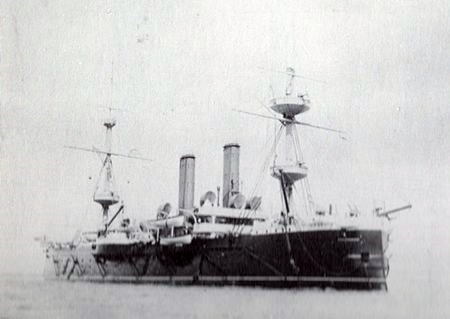

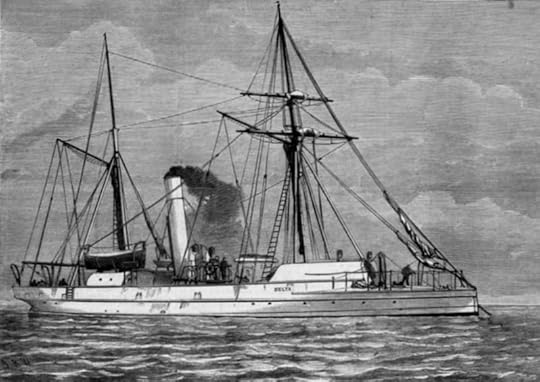

Zhongshan, as seen in the 1920s or 30s

The design was well suited to operation in sheltered coastal waters or on China’s vast inland river system. By the time the Yongfen and her sister Yonhsiang were delivered the Imperial Government had fallen. The new republic was to face many challenges, not least an attempt in 1915-16 by the first president, Yuan Shih Kai (1859-1916,) to proclaim himself emperor. Sun Yat Sen was a major force in frustrating this attempt. In the “Warlord Period” which followed, in which central authority was challenged by local strongmen who controlled vast areas with their private armies, naval units allied themselves with the “Constitution Protection Movement” which was pledged to defend the republic.

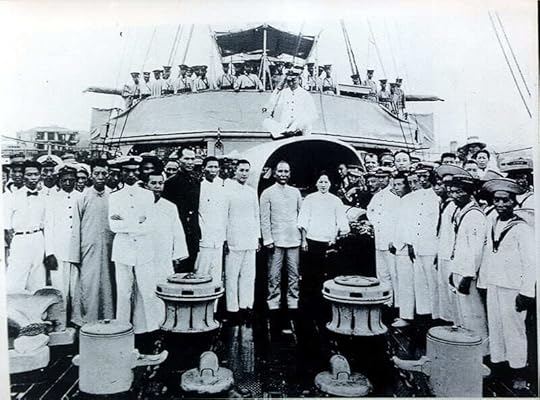

Sun Yat Sen and his wife, with crew, in 1922, when the Yongfen was his refuge

In 1922 during further internal strife, Sun Yat Sen, who was still actively attempting to unify the country, escaped danger by taking refuge on the Yongfen for a period of 55 days. This included running past the forts on the Pearl River, close to Guangdong (Canton), which were controlled by the warlord Chen Jiong Ming (1878-1933) with both Sun, and his protégée Chaiang Kai Shek on board. It was to commemorate this that the vessel was renamed Zhongshan.

Under its new name, the gunboat continued to have an active career, which included coastal operations against pirates. In 1937 however, when Japan invaded China (in what was essentially the opening of WW2, though few in the West wanted to recognise this at the time) she was deployed on the Yangtze River to oppose the Japanese advance westwards from Shanghai. On October 24th, near Wuhan, she was attacked and sunk by six Japanese aircraft, the captain and 20 of the crew being killed.

Hull seen on surface for the first tine in almost 60 years

Zhongshan refloated in 1997 – and in remarkably good condition

The wreck was to lie undisturbed until 1996 when it was resolved to raise and refurbish her as a memorial to Sun. The hull appears to have been in remarkably good condition and after an eight-man diving team removed some 1500 tons of silt from her it was possible to raise her, between two barges, in February 1997. The hull was winched onto a slipway for work to proceed on her and transported thereafter by means of a floating drydock to the custom-built viewing hall built for her near Wuhan. Final fitting out was done there, where she is now on permanent display. The photographs below give an idea of the very comprehensive work involved.

Restoration work in progress on slipway

Completely restored hull en-route to the display hall near Wuhan

Zhongshan being moved into display hall

As Zhongshan is currently displayed in Wuhan

The exhibition that I saw covered all aspects of the vessel’s history and operation. It included a splendid 1:50 model and a large display of artefacts recovered in good condition from the silt, which probably acted as a preservative. Seen together they present a poignant view of what life would have been on board Zhongshan as she patrolled the Chinese coast and penetrated deep into the interior on the country’s massive rivers.

1:50 model on display at exhibition

For me the exhibition proved an unexpected joy. Due to the lighting however, and the fact that I had only a mobile ‘phone with me, and not a proper camera, the photographs I took of the model through glass are therefore hazy. I have also taken the liberty of scanning photographs from the splendid exhibition guide and hope that by doing so I have not infringed copyright. I trust that my thanks to the Zhongshan Warship Museum and to the staff in Singapore, as well as my desire to share the pleasures of the exhibition with readers who cannot visit it in reality, may compensate for this.

Britannia’s GambleA Dawlish Chronicles Novel that earns consistent 5-Star Reviews It’s 1884. A fanatical Islamist revolt is sweeping all before it in the vast wastes of the Sudan and establishing a rule of persecution and terror. Only the city of Khartoum holds out, its defence masterminded by a British national hero, General Charles Gordon. His position is weakening by the day and a relief force, crawling up the River Nile from Egypt, may not reach him in time to avert disaster.

It’s 1884. A fanatical Islamist revolt is sweeping all before it in the vast wastes of the Sudan and establishing a rule of persecution and terror. Only the city of Khartoum holds out, its defence masterminded by a British national hero, General Charles Gordon. His position is weakening by the day and a relief force, crawling up the River Nile from Egypt, may not reach him in time to avert disaster.

But there is one other way of reaching Gordon…

A boyhood memory leaves the ambitious Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish no option but to attempt it. The obstacles are daunting – barren mountains and parched deserts, tribal rivalries and merciless enemies – and this even before reaching the river that is key to the mission. Dawlish knows that every mile will be contested and that the siege at Khartoum is quickly moving towards its bloody climax.

Outnumbered and isolated, with only ingenuity, courage and fierce allies to sustain them, with safety in Egypt far beyond the Nile’s raging cataracts, Dawlish and his mixed force face brutal conflict on land and water as the Sudan descends into ever-worsening savagery.

And for Dawlish himself, one unexpected and tragic event will change his life forever.

Britannia’s Gamble is a desperate one. The stakes are high, the odds heavily loaded against success. Has Dawlish accepted a mission that can only end in failure – and worse?

Click here to read the opening chapters freeClick below for more details of hard copy and Kindle editions:For BritainFor United States & Canada and elsewhereFor Australia and New ZealandIf you’re a Kindle Unlimited subscriber you can read the whole book at no extra chargeThe Dawlish Chronicles are now up to eleven volumes, and counting.In paperback and Kindle – Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Click on the image below for further details of each bookSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post A splendid restoration – China’s Zhongshan Gunboat appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 28, 2023

Captain Death of the Privateer Terrible

Captain Death of the Privateer Terrible, 1756

Captain Death of the Privateer Terrible, 1756For the commander of a privateer to be named “Captain Death” seems over-theatrical, especially as his ship was called the Terrible (one imagines him an adversary of Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow). There was however such a real-life character, even if this name was probably originally De’Ath, as it is spelled today and can still be found in Britain – it may refer to a family originally coming from the town of Ath in Belgium. In 1756, at the beginning of the Seven Years War, Captain Death was to fight a murderous battle against a French warship, the equally appropriately named Vengeance.

The account that follows draws on a book entitled “Privateers and Privateering” by a Commander E.P. Statham, R.N. and published in 1910. It draws on yet earlier accounts, including testimony from the Terrible’s third lieutenant, but it is short of detail on the exact nature of the ships involved, other than mention the size of their armaments.

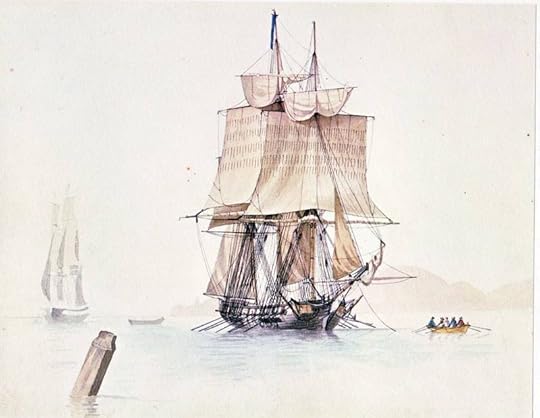

A becalmed French privateer, by Antoine Roux (1765-1835) – note the extended sweeps

Death’s vessel Terrible carried 26 guns and, judging by her crew of some 200 men, she may well have been a large brig, or even ship-rigged, and possibly a converted merchantman. In late 1756 she was cruising at the mouth of the English Channel off the French port (and heavily fortified base) of St. Malo. She had already captured an armed French cargo ship, the Alexandre le Grand, on to which Death had put a prize crew consisting of his the first lieutenant and fifteen men. The absence of the prize crew was to be sorely felt on Terrible as she could thereafter put only 116 men to work for, as her third lieutenant later told “the rest were either dead or sick below with a distemper called the spotted fever, that raged among the ship’s company.” This may have been typhus, or plague, and for fear of infection there may have led to reluctance to handle the dead bodies, some of which may have remained below deck. One suspects that lower hygiene standards might have obtained on a privateer than on ship of the Royal Navy, and that this may have lain at the root of the health problem.

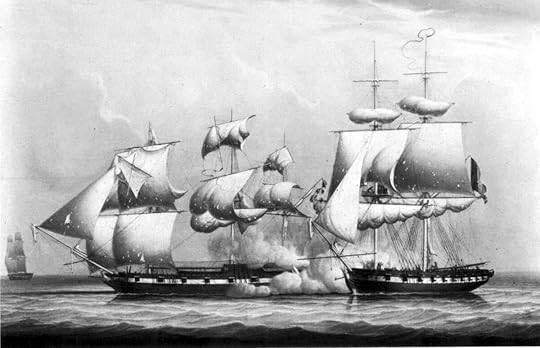

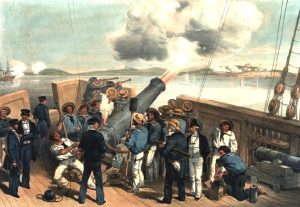

Merchantman Will of Liverpool under attack by a French privateer in 1804 – almost a half century on from the Terrible vs. Vengeance encounter, the essentials were unchanged

Merchantman Will of Liverpool under attack by a French privateer in 1804 – almost a half century on from the Terrible vs. Vengeance encounter, the essentials were unchanged

At daylight on December 27th, the undercrewed and fever-stricken Terrible was escorting her prize towards Plymouth when two vessels were sighted some twelve miles to the south. The larger steered for the Terrible and her prize and, as the latter was far astern, the Terrible was obliged to back her mizzen-topsail and wait for her, manning her guns as she did. Only when the stranger caught up, flying British colours until then, did she run up French colours and shorten sail.

HMS Observer, a brig, engaging the American Privateer Jack by night on May 29th 1782, off Halifax, Nova Scotia”. By Robert Dodd, 1784

The Terrible had her starboard guns manned, but her deep-laden prize, by this time close by, was a clumsy sailer and fell off from the wind. The French vessel, later identified as the 36-gun Vengeance (most likely a frigate, given her armament) and with a crew of some 400, gave the prize a broadside. She then came up close on Terrible’s port quarter and blasted another broadside diagonally across her deck, inflicting severe casualties. Terrible and Vengeance were so close together that the yardarms almost touched, but in spite of the mauling that Captain Death’s crew had just received, they returned a broadside of roundshot and grapeshot.

For five or six minutes both vessels surged on side by side. Boarding seemed a possibility – despite their losses, the French crew was numerically greater, but they held off and a succession of close-range broadsides followed, both sides sustaining heavy casualties. One factor weighed heavily against the Terrible – she was too short-handed by now to man her tops, while the Vengeance had eight or ten small-arms men in each of her own and firing down with muskets. This decided the action. Almost every man on Terrible’s deck was either killed or wounded. In parallel with this the French broadsides continued and took down the mainmast.

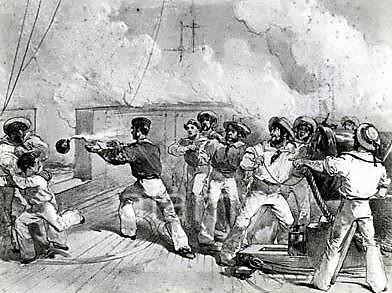

French Bellone engaging the East

Indiaman

Lord Nelson in close acti

on

in 1803 – “single ship actions” were always murderous affairs throughout the Age of Fighting Sail

French Bellone engaging the East

Indiaman

Lord Nelson in close acti

on

in 1803 – “single ship actions” were always murderous affairs throughout the Age of Fighting Sail

This was too hot to last. Terrible had taken over a hundred casualties. Only some twenty men, and one unwounded officer, were left to fight her. Captain Death had no option but to surrender but, while the colours were being hauled down, he was killed by a musket ball from one of the Vengeance’s tops.

Terrible’s third lieutenant, who survived, had been wounded in the cheek. His account of what followed was of little credit to the French victors: “They turned our first lieutenant and all our people down in a close, confined place forward the first night that we came on board, where twenty-seven men of them were stifled before morning; and several were hauled out for dead, but the air brought them to life again; and a great many of them died of their wounds on board the Terrible for want of care being taken of them, which was out of our doctor’s power to do, the enemy having taken his instruments and medicine from him. Several that were wounded they heaved overboard alive.”

Admiration for the Terrible’s heroic defence was widespread but, because she had been a privateer rather than a king’s ship, there a no question of compensation or pensions. A subscription was however raised at Lloyd’s Coffee House for Captain Death’s widow and those of his crew, and for the survivors, who had lost all their possessions.

The Terrible had met her fate at the end of the first year of a long war. There were another six to go.

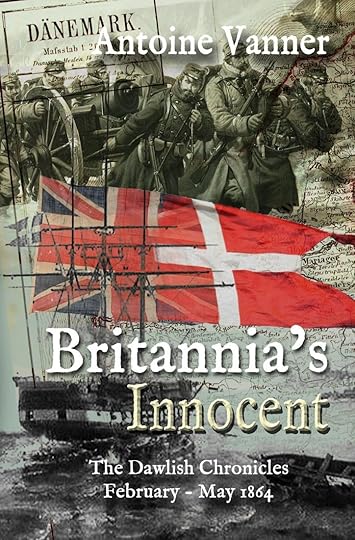

Start the 11-volume Dawlish Chronicles series with Britannia’s Innocent, the chronologically earliest of the Dawlish Chronicles 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish volunteers to support Denmark. He is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – not to mention divided loyalties . . .

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting.In paperback and Kindle – Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Click on the image below for further details of each book

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting.In paperback and Kindle – Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Click on the image below for further details of each bookSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Captain Death of the Privateer Terrible appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

June 22, 2023

The French Navy’s Iéna and Liberté Disasters, 1907 & 1911

The French Navy’s Iéna and Liberté Disasters, 1907 & 1911

The French Navy’s Iéna and Liberté Disasters, 1907 & 1911In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries all major navies, other than the German, lost large ships through magazine explosions of unstable ammunition. The first of such tragedies was in the US Navy, when the battleship USS Maine blew up in the harbour of Havana, Cuba, in January 1898. The explosion was initially blamed on sabotage by Spanish forces, and was a factor in precipitating the Spanish-American War of the same year (the recruiting slogan being “Remember the Maine!”) but it was only long afterwards when the cause was finally attributed to a magazine explosion.

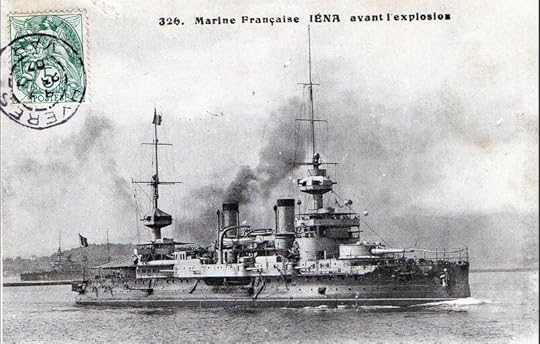

Iéna in service in happier times

Iéna in service in happier times

The French Navy was to be particularly unlucky in this respect in the years preceding World War 1, two pre-dreadnought battleships being lost while in the naval base at Toulon. The first disaster involved the 11500-ton, 401-feet long Iéna. In service since 1902, this vessel carried an armament – four 12”, eight 6” and many smaller – generally similar to those of her British contemporaries, such as the Formidable class, but on some 3000 tons less displacement.

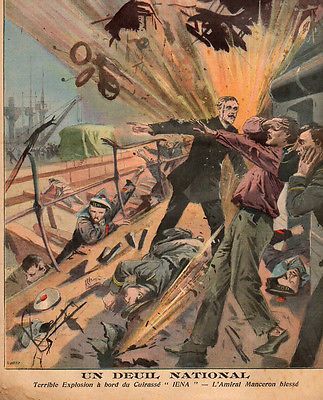

Contemporary image – Iéna exploding

On 12th March 1907 Iéna was in dry-dock at Toulon for maintenance of her hull and inspection of her rudder shaft (which had provided embarrassing problems on the ship’s first commissioning). The full complement was not therefore on board when a series of explosions erupted in the port-side magazines of the 4” anti- torpedo boat armament. The normal procedure in such cases would have been to flood the magazines, but this was impossible due to the ship being in dry-dock. The quick-thinking captain of the battleship Patrie, which was moored nearby, ordered a shell to be fired into the dock-gates to flood the dock but the shell failed to have any effect. Why it was not attempted to repeat this is not obvious. While this was going on, the violence of the explosions on the Iéna was enough to cause the battleship Suffren, moored close by, to heel over so far as almost to capsize. (The Suffren was an unlucky ship ever since her launching – click here to read more about her). The dock was finally flooded, thanks to the heroism of a young officer, Ensign de Vaisseau Roux, who was killed by fragments soon thereafter. Though the Iéna was damaged beyond repair the death toll – 120 lives – was lower than if the explosions had occurred at sea with her full 700-man crew on board.

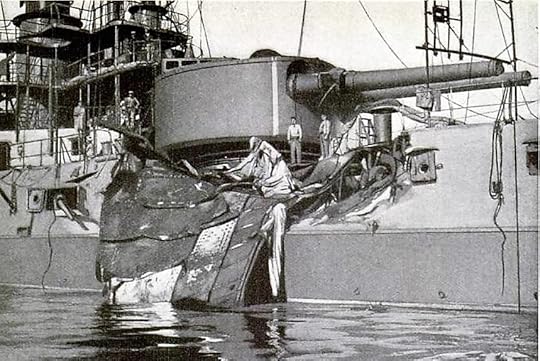

Iéna after the disaster

Iéna after the disaster

Investigation traced the origin of the explosion to the instability of the ammunition’s nitrocellulose-based propellant. Known as “Poudre B”, this was known to become unstable with age and to self-ignite. It was estimated that 80% of the contents of the ship’s magazines were the suspect at the time of the accident – which could have been far worse had the magazines of the main 12-inch weapons also detonated. Scandals – known as affairs – were one of the great institutions of the French Third Republic that lasted from 1870 to 1940 and the Iéna disaster was to trigger a choice specimen, referred to as “l’Affaire des Poudres” which resulted in the resignation of the Navy Minister, Gaston Thomson (1848 -1932). Like so many French politicians of the time, involvement in a scandal does not seem to have affected his future career negatively.

Liberté at speed

Liberté at speed

Lessons from the loss of the Iéna should have been sufficient to avoid similar tragedies in the future but three similar accidents occurred on smaller vessels over the next three years, with no ship lost and a small death-toll. A greater disaster was however to occur, again in Toulon, for years later. The Liberté, of 14630- tons and 430-feet length, was one of the four ships of the class to which she gave her name and which were the last pre-dreadnoughts to serve in the French Navy. Liberté was obsolete at time of her launch and she entered service in 1908, a year after Britain’s HMS Dreadnought had changed the battleship paradigm. Her four 12-inch cannon represented a puny armament when compared with the Dreadnought’s ten. Liberté did however also mount ten 7.6-inch weapons, six in single turrets and four in casemates.

Liberté exploding – contemporary artist’s impression

Liberté exploding – contemporary artist’s impression

Liberté was moored in the harbour in Toulon on 25th September 1911 when an explosion erupted in one of the forward magazines of the 7.6-inch guns. The situation was serious, but not yet fatal, and the commander, Captain Louis Jaurès, sent a party forward to flood the magazines to prevent an explosion in the main magazines. A major design fault was now manifested, for the flooding valves were located beneath the magazines. Two heroic attempts were made to reach the valves but were beaten back by fire and smoke. A third attempt was in progress when the main magazine exploded, tearing the ship apart. A

40-ton armour plate from the Liberté lodged in the side of the République

40-ton armour plate from the Liberté lodged in the side of the République

The violence of the detonation was sufficient for the pre-dreadnought République, moored over 200 yards away, to be damaged seriously when a 40-ton section of Liberté’s armoured plate was thrown against her side. The death-toll was some 250 and state funerals for these victims were attended by the president and a relief fund for the bereaved families received massive support across the nation.

The wreckage of the Liberté – hardly identifiable as a ship

The wreckage of the Liberté – hardly identifiable as a ship

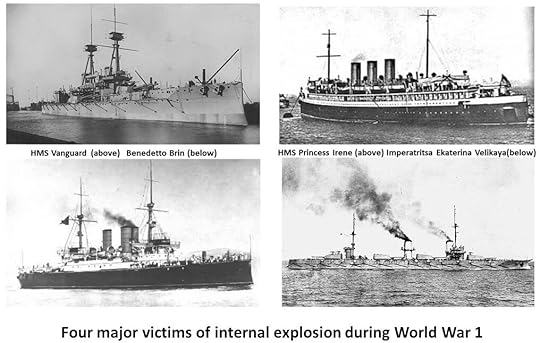

France had learned the hard way, but other nations were to suffer similar disasters during World War 1. Britain was to lose the pre-dreadnought HMS Bulwark in 1914, the mine-layer HMS Princess Irene in 1915, the armoured-cruiser HMS Natal in 1915 (click here to read an earlier blog about it) and the dreadnought HMS Vanguard in 1917. The Italian Navy was to lose the pre-dreadnought Bendetto Brin in 1915 and the Imperial Russian Navy was to lose the massive new dreadnought Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaya at Sevastopol in 1917. Japan’s first dreadnought, the Kawachi, blew up in 1918. In all cases the death toll was horrific.

Improvements in propellant stability ended this string of disasters after 1918 and internal explosions were not to punctuate World War 2, as they had the previous conflict.

Start the 11-volume Dawlish Chronicles series with Britannia’s Innocent, the chronologically earliest of the Dawlish Chronicles 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing. The Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish volunteers to support Denmark. He is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – not to mention divided loyalties . . .

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting.In paperback and Kindle – Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Click on the image below for further details of each book

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to eleven volumes, and counting.In paperback and Kindle – Kindle Unlimited subscribers read at no extra charge.Click on the image below for further details of each bookSix free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post The French Navy’s Iéna and Liberté Disasters, 1907 & 1911 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 25, 2023

First Winner of Victoria Cross – 1854

Ever since the Crimean War (1854-56) the Victoria Cross has been the highest award for British service personnel for gallantry in the face of the enemy. It takes precedence in order of wear over all other British orders, decorations, and medals, including the Order of the Garter. Instituted by Queen Victoria in 1856 it was revolutionary at the time of introduction in that the award made no distinction between officers and enlisted men. Of some 1358 awarded since then, only fifteen have been won since the end of WW2 (four of them by members of the Australian Army). The medal is of bronze taken from Russian cannon captured at Sevastopol.

Ever since the Crimean War (1854-56) the Victoria Cross has been the highest award for British service personnel for gallantry in the face of the enemy. It takes precedence in order of wear over all other British orders, decorations, and medals, including the Order of the Garter. Instituted by Queen Victoria in 1856 it was revolutionary at the time of introduction in that the award made no distinction between officers and enlisted men. Of some 1358 awarded since then, only fifteen have been won since the end of WW2 (four of them by members of the Australian Army). The medal is of bronze taken from Russian cannon captured at Sevastopol.

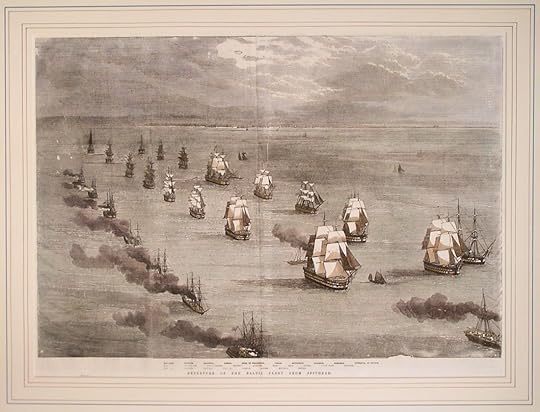

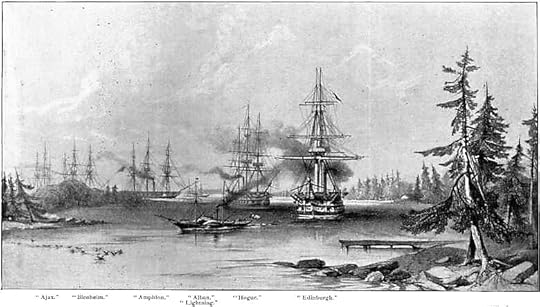

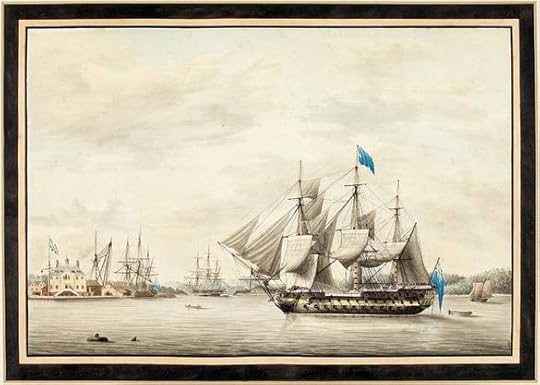

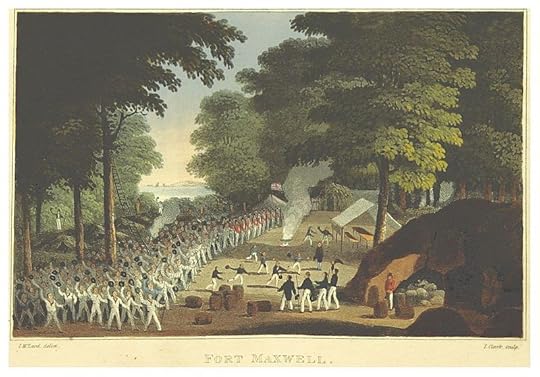

Departure of the Baltic Expedition from Spithead 1854

Though the first Victoria Cross was won in the Crimean War the heroism that won it took place not in the Crimea but in the Baltic. Britain and France entered the war against Russia in March 1854. In parallel with efforts to invade the Crimea measures were also put in hand to send a vast British fleet to the Baltic to neutralise fortifications protecting the approaches to St. Petersburg and seal it off.

The execution left much to be desired, however. “A finer fleet never sailed or steam from Spithead than that destined for the Baltic in 1854” according to the future Hobart Pasha. Referring however to the overall commander, Sir Charles Napier, known as ’Fighting Old Charley’, Hobart went on to write that “it was not long before we discovered that there was not much fight left in him.”

Approaching Bomarsund – steam vessel towing sailing warship through narrow channel

The initial British objective was the incomplete Russian fortress of Bomarsund in the Åland Islands. This was vulnerable to land attack since the designers had assumed that the narrow channels near the fortress would not be passable for the large ships needed to land troops. This assumption was valid for sailing vessels but it took no account of the fact that steamships could manoeuvre with greater ease and thus bring weakly defended sections of the fortress. One gets the impression that the focus on Bomarsund was due to its accessibility rather to any significant strategic importance and Hobart, in his memoirs, hints that dissatisfaction with the decision was widespread. He wrote: “if ever open mutiny was displayed – not by the crews of the ships, but by many of the captains, men who had attained the highest rank in their profession – it was during the cruise in the Baltic in 1854.”

Bombarding Bomarsund

On 21st June 1854, three British ships, Hecla, Odin and Valorous, came close enough to begin bombardment. Russian fortress-artillery replied and the action lasted most of the following night. At its height a live shell, its fuse hissing, crashed on to the deck of the Hecla, a wooden paddle-sloop. Given that this vessel was wholly unarmoured, it seems an act of the grossest folly to have exposed ever her in this way. Only seconds remained before the shell would explode and orders were shouted for everybody to throw themselves flat. On deck however was the twenty-year old Midshipman Charles Davis Lucas (1834 – 1914), who had already served seven years, a period that included the Second Burmese War. Rather than throw himself down Lucas grabbed the shell, dashed to the side and threw it overboard. It exploded on hitting the water. No further damage was done, nor were any of the crew wounded. The indecisive action was broken off shortly afterwards to wait until British and French reinforcements would arrive.

Contemporary illustration – Lucas throwing the shell overboard

Lucas VC in 1857

Lucas’s action had saved the Hecla, but given the reward structure in place at the time the only recognition possible was for her captain, W.H. Hall, to promote him to the rank of Acting Lieutenant. The Crimean War was the first to be covered extensively by the newspapers and Lucas’s behaviour, together with other individual acts of bravery, was widely reported. The outcome was a motion in Parliament “that an Order of Merit to persons serving in the army or navy for distinguished and prominent personal gallantry to which every grade should be admissible” should be created.

Though Lucas was the first winner, he was not however the first to receive his medal in the inaugural award ceremony in June 1857. This was held in London’s Hyde Park and it was estimated that over 100,000 people came to watch. Queen Victoria pinned the crosses on the recipients in strict order of Service precedence and seniority. Lucas was therefore fourth in line, following three more senior recipients, the first being Commander Henry Raby. Lucas may however have been lucky to miss the first slot – the Queen conducted the tricky operation of pinning on the medal from horseback. In the process, and by accident, she plunged the double-pronged pin for holding the medal into Raby’s chest. This was presumably a minor inconvenience compared with the dangers he had been exposed to while winning the medal!

Queen Victoria awarding the first Victoria Crosses, 26th June 1857

by George H. Thomas (1824-1868)

Rear-Admiral Lucas

Lucas went on to have a distinguished naval career, promoting to commander in 1862, to captain in 1868 and retiring in 1873, making rear-admiral on the retired list in 1885. It is pleasing to note that he married the daughter of Captain Hall of the Hecla, the ship on which he won his VC. He was to live on until 1914, another of those naval officers who joined a service still commanded by veterans of the age of Nelson, but who themselves lived to see technological innovations of the early 20th Century such as turbines, radio, aircraft and submarines which were to change the nature of sea warfare. (As was the life of Admiral Sir Nicholas Dawlish! Click here for details).

Technology changes but human nature doesn’t. The Victoria Cross remains today, as it did in 1854, the recognition of human courage at its most sublime.

Britannia’s Wolf:The Dawlish Chronicles: September 1877 – February 1878 The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The war is reaching its climax and aA Russian victory will pose a threat to Britain’s strategic interests. To protect them an ambitious British naval officer, Nicholas Dawlish, is assigned to the Ottoman Navy to ravage Russian supply lines in the Black Sea. In the depths of a savage winter, as Turkish forces face defeat on all fronts, Dawlish confronts enemy ironclads, Cossack lances and merciless Kurdish irregulars, and finds himself a pawn in the rivalry of the Sultan’s half-brothers for control of the collapsing empire. And in the midst of this chaos, unwillingly and unexpectedly, Dawlish finds himself drawn to a woman whom he believes he should not love. Not for her sake and not for his . . .

Available in paperback, Kindle. Amazon Prime subscribers read on Kindle at no extra cost.The Audiobook can be downloaded for free as an Audible trial.Click below for details and ordering in any format.For US & Canada For UK and Europe For Australia and New ZealandBelow are the eleven Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the image-block below for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post First Winner of Victoria Cross – 1854 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

May 19, 2023

A Sultan’s Salvage and Queen Victoria

It’s hard to imagine a sequence of events that links an Ottoman Sultan, Queen Victoria, the Royal Navy of 1889, an innovative epic of marine salvage and an 1870s warship which served in various capacities until the end of the Second World War. The link is however the ironclad HMS Sultan, built between 1870 and 1876.

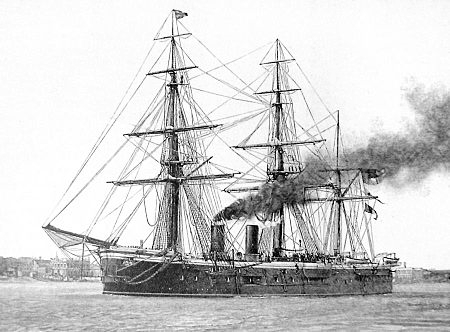

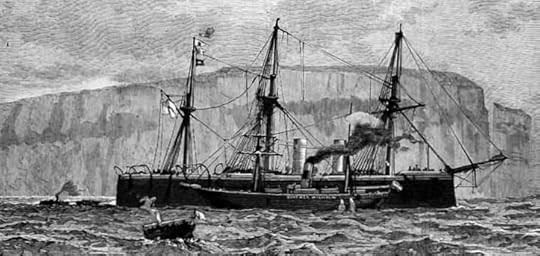

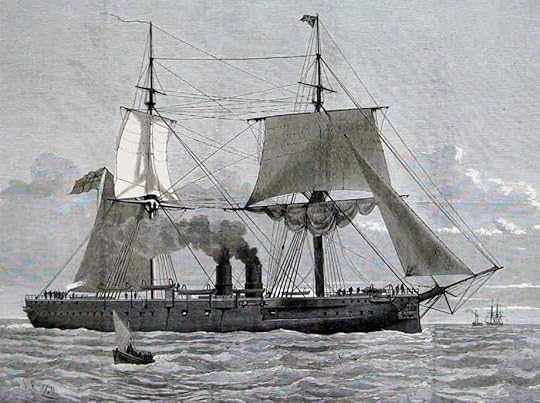

HMS Sultan in her early career

I was spurred to research and write this article by reading the memoirs of the great Royal Navy gunnery expert of the pre-World War period, Admiral Sir Percy Scott (1853-1924) who as a young officer played a peripheral role in the story. I will quote directly from him later in this article. (See photograph on right – Scott as a captain in mid-career).

I was spurred to research and write this article by reading the memoirs of the great Royal Navy gunnery expert of the pre-World War period, Admiral Sir Percy Scott (1853-1924) who as a young officer played a peripheral role in the story. I will quote directly from him later in this article. (See photograph on right – Scott as a captain in mid-career).

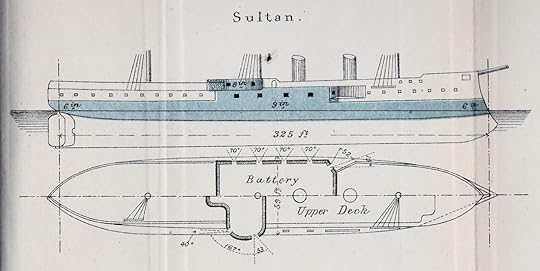

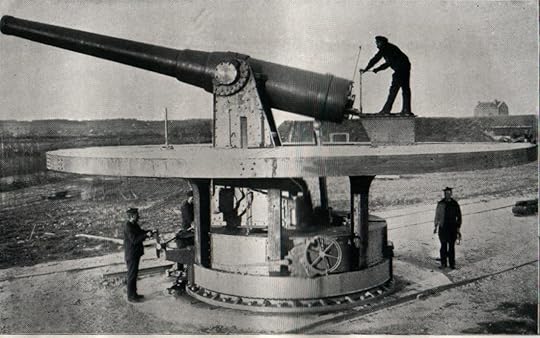

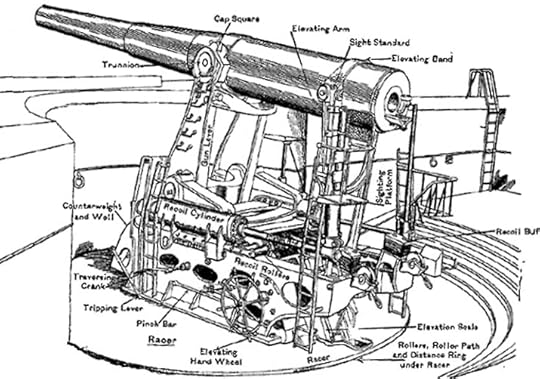

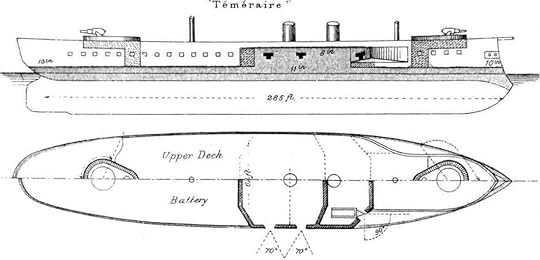

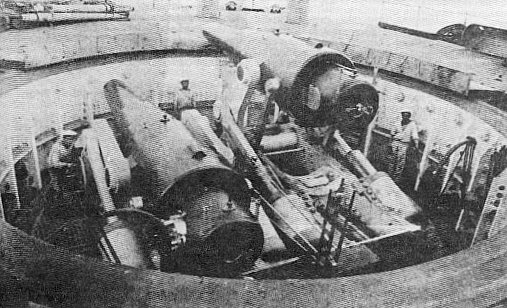

HMS Sultan was of 9290 tons and 325 feet long. A single-shaft 7720 HP engine drove her at a maximum 14 knots under steam but could only make 6 knots under sail. She was designed to carry her guns in a centrally-placed armoured-box battery, as will be seen in the contemporary diagram below which shows the battery’s two levels. The armament consisted of eight 10-inch and four 9-inch rifled muzzle-loaders. The weapons on the main deck guns provided broadside fire, with limited ahead fire from the foremost gun on each side, while those on the upper deck provided additional broadside fire and also could fire astern, by traversing the after gun on a turntable. Side armour – as seen in blue on the diagram below – was up to 9 inches thick. The ship, and her armour, were all of iron as steel was not yet the preferred construction material.

The Sultan was named in honour of the Ottoman Sultan, Abdülaziz, who admired Western progress and who hoped to reform and develop his empire as a modern state. A cultured man, he was the first Ottoman sultan to visit Western Europe; his trip included a visit to England in 1867, and while there he was honoured by Queen Victoria by a Royal Navy Fleet Review, during which he was invested with the Order of the Garter. A further gesture of respect was the subsequent naming of HMS Sultan in his honour. It should be remembered that in this period the Ottoman Empire was regarded by Britain as a bulwark against a Russian threat to communication with India and its friendship was accordingly highly valued. (Readers of my novel Britannia’s Wolf will appreciate this!)

Queen Victoria investing the Sultan with the Order of the Garter

on the deck of the Royal yacht – by George Housman Thomas (1824-68)

HMS Sultan was indeed to be of service of the Ottoman Empire, but after the death of Abdülaziz. This service occurred in early 1878 when the Sultan was part of British Squadron which moored off Istanbul at the moment, at the end of the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, when the victorious Russian armies had reached the city’s suburbs and were about to enter. This was unacceptable for Britain and the presence of the Royal Navy squadron showed determination to go to war with Russia to prevent it. Thus confronted, the Russians backed down and peace was made with the Ottomans.

British squadron, including HMS Sultan, steaming up

the Dardanelles to Istanbul, early 1878

Much of the Sultan’s active service was to be in the Mediterranean and in 1882 she was to participate in the bombardment of Alexandria, sustaining casualties of two killed and eight wounded from a single hit on her battery.

The most dramatic events in her life were to commence in March 1889. At this point I hand over to Sir Percy Scott, who was then serving on HMS Edinburgh at the time and who tells the story much better than I can:

Quote

It was on the 6th March, 1889, that H.M.S. Sultan, while practising firing torpedoes, struck on a rock in the Comino Channel. Every endeavour to tow her off failed, and seven days afterwards, during a northerly gale, she was washed off the rock and sank in 42 feet of water. An examination of the hull of the vessel by divers revealed that the damages sustained were so excessive that all hope of getting her up was abandoned. The Admiralty offered £50,000 to anyone who would raise her and bring her into a harbour, but the representatives of two or three firms who had a look at her agreed in regarding the task as impossible.

HMS Sultan, initially aground, attempts to pump her out in progress,

prior to being washed off the rock

Two months later, a French engineer, named Chambon, who was employed in the Corinth Canal, paid her a visit and, to the surprise of everyone, expressed an opinion that she could be raised quite quickly. A contract was at once made with the Admiralty by which they were to pay £50,000 if the Sultan was in Malta Harbour before the end of the year

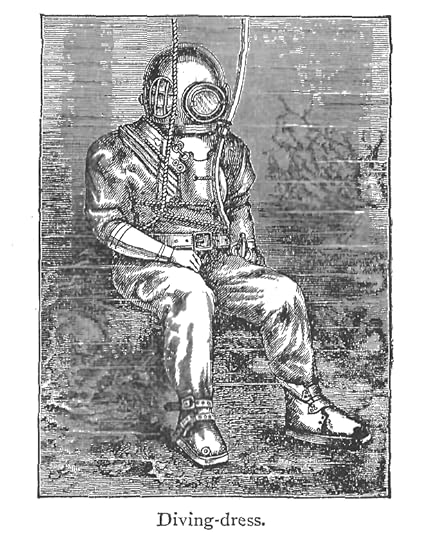

Speculation was rife as to how many men-of-war M. Chambon would require to assist him, and how much plant he would bring. He required no help, and arrived in a tiny steamer called the Utile, with a total crew of twelve, six of whom were divers. The only plant he brought was brains.

Speculation was rife as to how many men-of-war M. Chambon would require to assist him, and how much plant he would bring. He required no help, and arrived in a tiny steamer called the Utile, with a total crew of twelve, six of whom were divers. The only plant he brought was brains.

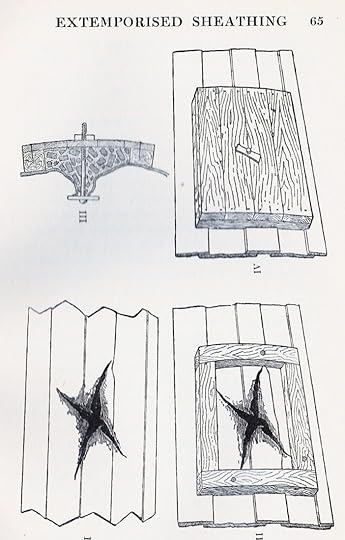

He started work on the 24th June by cautiously blasting away such rocks as were too close to- the ship’s side to enable the work to be undertaken on the holes that had been discovered. The task of closing up the larger fractures in the ship’s bottom was then begun and one by one the holes were sealed up in the- following ingenious manner.

From templates taken by the divers of the curvature of the ship’s bottom in the vicinity of the hole, a wooden frame was prepared. This was sent down, and the divers secured it round the hole. Across this frame planks were nailed, and as each plank was put in its, place, the space between it and the plating was -filled in with a mixture of bricks, mortar, and cement, and thus a solid sheathing was formed over the hole.

The excellence of this work can be seen from the pictures on the opposite page (reproduced above); it was a master-piece of diving skill. Meanwhile the work of making watertight the upper deck, including hatchways, ports, and ventilators, was proceeded with, and the various pumps put on board by the dockyard were got ready for pumping her out. At the end of a month, on the 27th July, all the holes were sealed up, the pumps were started, and the ship was lifted. Unfortunately a gale of wind sprang up. The Sultan sank again and in striking the bottom, did more damage to the hull.

The excellence of this work can be seen from the pictures on the opposite page (reproduced above); it was a master-piece of diving skill. Meanwhile the work of making watertight the upper deck, including hatchways, ports, and ventilators, was proceeded with, and the various pumps put on board by the dockyard were got ready for pumping her out. At the end of a month, on the 27th July, all the holes were sealed up, the pumps were started, and the ship was lifted. Unfortunately a gale of wind sprang up. The Sultan sank again and in striking the bottom, did more damage to the hull.

This disheartening occurrence only strengthened M. Chambon’s indomitable energy. Directly the weather moderated, the divers went down, repaired the hull and on the 17th August the pumps were started and the Sultan floated.

Then followed catastrophe number two. While she was being moved, the ship was caught by the current and knocked up against a rock, displacing a patch. She filled, and sank for the third time.

The reports of the divers as to the extent of the damage done by this third sinking were very discouraging; but nothing would deter M. Chambon from completing his work. Renewed energy was put into it, and, nine days afterwards, on the 26th August, the Sultan was up again and towed into Malta harbour. I was in charge of a large party of men from the Edinburgh to assist in docking and clearing her.

The ship must have been splendidly built. After sinking three times and being on the bottom for six months, she showed no signs of structural weakness. As the water was pumped out, we turned the engines and trained the guns, which showed she was not out of line. In a month or two she steamed home.

Unquote

This superb achievement was only made possible by the availability of Standard Diving Dress, which was then cutting-edge technology . The techniques employed were innovative at the time and were to become standard in the salvage industry thereafter.

After arriving back in Portsmouth the Sultan underwent modernisation and repair, at a rather leisurely rate, until 1896, losing her masts and yards in the process. Of little fighting capability, she stayed in reserve until 1906.

HMS Sultan post-modernisation

Scott’s remark that the Sultan “must have been splendidly built” appeared in his memoirs in 1919. By then her large and robust hull had been used, under different names, as an artificers’ training ship and as a mechanical repair ship. When Scott wrote she still had over a quarter-century’s service ahead of her as she was to be employed as a depot ship for minesweepers at Portsmouth during World War 2, being finally scrapped in 1947.

Scott’s remark that the Sultan “must have been splendidly built” appeared in his memoirs in 1919. By then her large and robust hull had been used, under different names, as an artificers’ training ship and as a mechanical repair ship. When Scott wrote she still had over a quarter-century’s service ahead of her as she was to be employed as a depot ship for minesweepers at Portsmouth during World War 2, being finally scrapped in 1947.

And what of Sultan Abdülaziz? His passion for modernisation led to mounting public debt and he was deposed by his ministers on May 30th 1876. He was dead five days later, allegedly by suicide. The method reported – getting hold of scissors in his tower prison cell and managing to cut his two wrists at once – sounded unlikely in the extreme and it was widely believed that he had been murdered.

The ship named in his honour was to outlive this tragic figure by seventy-one years.

Britannia’s Wolf:The Dawlish Chronicles: September 1877 – February 1878 The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The aftermath of the death of Sultan Abdülaziz and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78 provide the background to Britannia’s Wolf.

The war is reaching its climax and aA Russian victory will pose a threat to Britain’s strategic interests. To protect them an ambitious British naval officer, Nicholas Dawlish, is assigned to the Ottoman Navy to ravage Russian supply lines in the Black Sea. In the depths of a savage winter, as Turkish forces face defeat on all fronts, Dawlish confronts enemy ironclads, Cossack lances and merciless Kurdish irregulars, and finds himself a pawn in the rivalry of the Sultan’s half-brothers for control of the collapsing empire. And in the midst of this chaos, unwillingly and unexpectedly, Dawlish finds himself drawn to a woman whom he believes he should not love. Not for her sake and not for his . . .

Available in paperback, Kindle. Amazon Prime subscribers read on Kindle at no extra cost.The Audiobook can be downloaded for free as an Audible trial.Click below for details and ordering in any format.For US & Canada For UK and Europe For Australia and New ZealandBelow are the eleven Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the image-block belowfor more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post A Sultan’s Salvage and Queen Victoria appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 28, 2023

Silas Talbot – American Naval Hero

USS Constitution today

The USS Constitution – “Old Ironsides” – is apparently the only active ship in service in the United States Navy to have sunk an enemy ship in combat. She was launched 220 years ago and is a true national treasure. Immediately after commissioning in 1798 she was to plunge into more than a decade and a half of war, first against the French in the undeclared “Quasi-War”, thereafter in the Barbary Wars and lastly, and against the Royal Navy in the War of 1812, when in frigate-to-frigate “single ship actions” she defeated the British HMS Guerriere and HMS Java. It is with the Constitution’s second captain, Silas Talbot (1751 – 1813) that this blog is concerned, most especially regarding his service as a privateer during the American War of Independence, a type of combat largely overlooked in many accounts of the conflict. A man of many parts, Silas Talbot had experience in business, politics and armed service both ashore and afloat during his lifetime. He was wounded thirteen times and was credited with carrying five bullets in his body. Much of what follows is based, at second hand, on a book published in the United States in 1803 and entitled “The Life and Surprising Adventures of Captain Silas Talbot; containing a Curious Account of the Various Changes and Gradations of this Extraordinary Character.” It was apparently based on information by Silas Talbot himself.

Silas Talbot

Hailing from Massachusetts, Silas Talbot went to sea as a cabin boy at the age of twelve, working his way up so successfully that nine years later he could buy substantial property ashore. In the early stages of the American Revolution Talbot was appointed as a captain in a Rhode Island Regiment and one of his early exploits was the use of a fire ship to attack the Royal Navy’s “64”, HMS Asia, at New York in September 1776. The fire ship collided with the Asia and set fire to her, but the crew, with aid from nearby vessels, managed to extinguish the flames. Silas Talbot escaped but sustained severe burns. Undaunted, he next took part in the defence of Philadelphia in October 1777 – being wounded again – and thereafter in the Battle of Rhode Island ten months later.

HMS Asia – seen in 1797 at Halifax, almost twenty years after Talbot tried to destroy her

In 1779, having meanwhile been promoted to the rank of colonel, Silas Talbot commenced his career as a privateer commander. The British had a considerable number of private ships of war afloat on the American coast at that time and numerous American privateers were authorised to counter the. Talbot was placed in command of the Argo, a sloop of under 100 tons, armed with twelve 6-pounders, and carrying 60 men. She was described as having a single mast, being steered with a long tiller, havingvery high bulwarks and a wide stern. It was remarked that “her bottom was her handsomest part,” which indicated that her underwater hull form made her swift and handy.

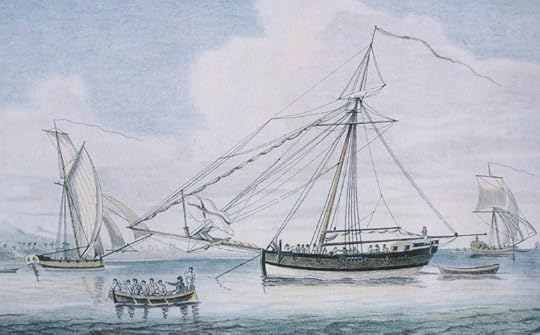

A Bermuda sloop, serving as a privateer. Talbot’s Argo might have looked very similar

The Argo’s first encounter with an enemy was with a privateer, the King George, commanded by a loyalist from Rhode Island, a Captain Hazard. This gentleman was described as having been an esteemed citizen until he elected to fight on the British side “for the base purpose of plundering his neighbours and old friends”. The King George was more powerfully armed than the Argo, carrying 14 guns and 80 men; but her captain may have mistaken the Argo for a merchant vessel. He permitted Talbot to come to close quarters without opposition, for the writer tells us that Talbot“steered close alongside him, pouring into his decks a whole broadside, and almost at the same instant a boarding party, which drove the crew of the King George from their quarters, and took possession of her without a man on either side being killed.”

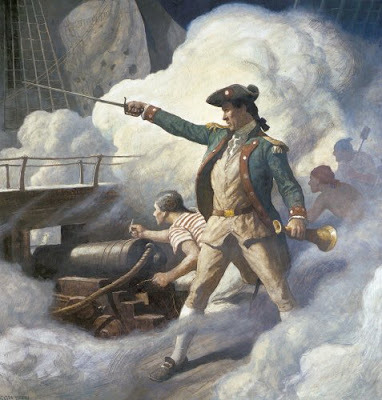

The iconic image of an American privateer – John Paul Jones at war

The Argo’s next antagonist was the British privateer Dragon, of 300 tons, 14 guns, and 80 men. This was a desperate engagement, carried on at pistol-shot range for four and a half hours. A large part of the men on deck—a vessel like the Argo certainly did not fight with any below—were either killed or wounded but the Dragon, losing her mainmast, at length struck her colours. The Argo was all but sinking, having sustained hits “between wind and water” but prompt action sealed them off.

After refitting the Argo, Talbot sailed in company with another privateer, the Saratoga, commanded by a Captain Munroe. Near New York, off Sandy Hook, they encountered the Dublin, a British privateer cutter carrying 14 guns. It was agreed that Talbot should first give chase, for fear that the sight of two vessels bearing down upon him should alarm the Dublin’s commander. The British vessel stood her ground however and awaited the attack. Argo and Dublin fought an inconclusive ship-to-ship gunnery duel before Munroe arrived with the Saratoga – there seems to have been some suspicion that he might have hung back. Once on the scene however, the Saratoga fired a single broadside that ended the affair and the Dublin, outnumbered, struck her colours.

Talbot’s next fight was one that seems almost straight from a novel. The Betsy, a British privateer of 12 guns and 38 men, was “commanded by an honest and well-informed Scotchman.” The Argo’s identity as a privateer seems, once more, not to have been suspected and Talbot came close before running up the stars and stripes and shouting, “You must now haul down those British colours, my friend!”

Courtesy (and elegant English) prevailed even at this juncture and the Scottish captain replied, “Notwithstanding I find you an enemy, as I suspected, yet, sir, I believe I shall let them hang a little longer, with your permission. So fire away!” The decision was an unwise one – the Argo’s opening fire decided the outcome in her favour.

Talbot was now formally appointed as a captain in the Continental Navy but with no naval ship available he took command of another privateer, the General Washington, in 1780. His luck was about to run out. He took only one prize, but soon thereafter ran into a British squadron – ironically at the scene of an earlier success, off Sandy Hook. A foiled attempt to run ended with him surrendering to a “74”, HMS Culloden. He was detained in squalid conditions on the Jersey prison-ship, off Long Island and thereafter brought as a prisoner of war to Britain, where he allegedly made four attempts at escape before being exchanged in December 1781. He must have had some grim satisfaction in learning that HMS Culloden had been destroyed by her crew to avoid capture after running ashore on Long Island in January 1781.

HMS Culloden

A prosperous man – largely, on suspects, on the basis of privateering success – Silas Talbot settled in New York State, buying the large estate of the British commander of Indian and colonial forces in the Seven Years War, Sir William Johnson. He was elected to Congress in 1793 but he seems to have retained naval ambitions. A year later President Washington was to appoint his as the third in the list of six captains of the newly constituted United States Navy. Resigning from Congress, Silas Talbot was entrusted with supervision of the construction of the USS President, one of the innovative “six frigates” that were to be the foundation of the new navy. For two years from mid-1799 he would command her sister, the USS Constitution, protecting American commerce from the depredations of French privateers in the West Indies. Silas Talbot resigned in 1801, possibly due to ill health – not surprising, in view of the wounds he had sustained during his career.

Little known today, Silas Talbot deserves to be remembered as one of the founding fathers of today’s US Navy. Bear him in mind if you are ever lucky enough to visit USS Constitution in Boston.

Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War? 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Cut off from the main Danish Army, and refusing to use the word ‘retreat’, a resolute commander withdraws northwards. Harried by Austrian cavalry, his forces plod through snow, sleet and mud, their determination not to be defeated increasing with each weary step . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Cut off from the main Danish Army, and refusing to use the word ‘retreat’, a resolute commander withdraws northwards. Harried by Austrian cavalry, his forces plod through snow, sleet and mud, their determination not to be defeated increasing with each weary step . . .

Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing . . .

But Denmark is not wholly without sympathisers. Britain’s heir to the throne is married to a Danish princess. With his covert backing, British volunteers are ready to fight for the Danes. And the Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish is induced to volunteer and is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – notwithstanding divided loyalties . . .

In other books of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Dawlish is met as an experienced and resourceful officer, but in 1864 he is still an innocent. But he will need to learn fast . . .

For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auBelow are the eleven Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are aailable in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Silas Talbot – American Naval Hero appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 14, 2023

Discipline and heroism in the aftermath of the loss of HMS Alceste

The aftermath of the wreck of the French frigate Medusa in 1816 is widely regarded as one of the most horrible events in maritime history. Abandoned on an overloaded raft by officers and crew, who took to the boats when the vessel grounded off the coast of modern Mauritania, only fifteen persons survived out of a total of 147. In the thirteen days the raft drifted, 132 died through thirst and starvation, fighting and suicide. Cannibalism sustained the survivors. Though the ship’s boats had reached safety no systematic search was made for the raft and it was only discovered, accidentally, by the British ship Argus. A major scandal at the time, the raft became the subject of an unforgettable painting by Théodore Géricault (1791-1824).

[image error]

“The Raft of the Medusa” – today in the Louvre, ParisThe breakdown in responsibility and discipline that led to this appalling disaster can be contrasted with the happy outcome of what could have been a similar tragedy when a Royal Navy frigate, HMS Alceste, was wrecked the following year. The value of professionalism and discipline has seldom been so dramatically illustrated.

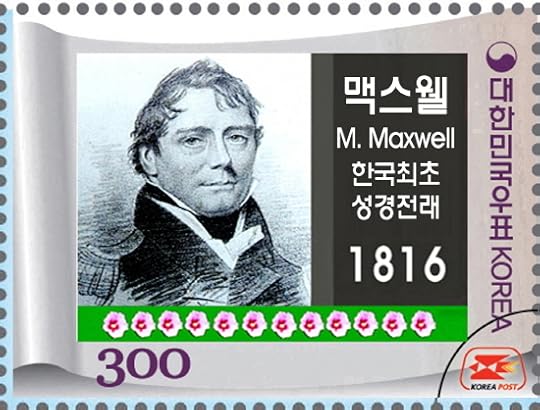

HMS Alceste was built in 1804, as the Minerve, for the French Navy – generally similar in fact to the Medusa. Two years later she was captured by the Royal Navy and taken into service as HMS Alceste, under command of Captain (afterwards Sir) Murray Maxwell, (1775 –1831). He was to be her captain for much of her Royal Navy career until her final loss. In 1811, in company with HMS Active, Maxwell and the Alceste captured the French frigate Pomome. Maxwell was to be congratulated on this in strange and unforeseeable circumstances six years later. HMSAlceste provided sterling service through the remainder of the Napoleonic Wars and in the War of 1812.

Painting by Pierre Julien Gilbert (1783-1860)

In 1816 HMS Alceste was assigned to carrying William Pitt Amehurst, the first Lord Amherst, on a diplomatic mission to China, the objective being to establish formal relations between Britain and the Chinese Empire. Amehurst was landed at Canton (Guangzhou) and travelled overland to Pekin (Beijing). In his absence, Captain Maxwell and HMS Alceste undertook extensive survey work in uncharted waters off the coasts of China, Korea, and Okinawa. This work is so well thought of, even today, that Maxwell has been honoured by a South Korean postage stamp.

On her return to China HMS Alceste required repairs to ready her for the long voyage home. This necessitated mooring in calm water in the Pearl River, close to Canton. A request to do so was refused by the Chinese authorities, who threatened to have the gun-batteries guarding the river open on HMS Alceste should she proceed. Captain Maxwell responded in the robust manner to be expected of the Royal Navy of his day – he bombarded and subdued the shore defences and some seventeen war-junks supporting them. He then moored, commenced his repairs and awaited Amehurst’s return.

As depicted by Alceste’s surgeon, John MacLeod, in his account of her final voyage

In the event Amehurst’s mission proved to be a total failure, doomed as it was by mutual incomprehension. Self-sufficient for millennia, China officials had little or no understanding of the outside world and regarded all other nations as inferior. Amehurst was informed that he could only be admitted to the Emperor’s presence if he were to kowtow – which meant kneeling and bowing so low as to touching the forehead on the ground. As representative of a proud nation that had opposed the might of France and her allies for over twenty years, and which had the previous year seen off the Emperor Napoleon, Amehurst had no intention of abasing himself or his country. Faced with an impasse, he had no option to head home. He rejoined HMS Alceste and she set out for England, he and his entourage, plus the frigates crew, adding up to 257 on board.

Disaster struck in the Java Sea – an area largely uncharted at the time. Despite continuous soundings, HMS Alceste ran onto a hidden reef on 18 February 1817, the damage so severe that the flooding was too much for the pumps to handle. Abandonment was now essential, the nearest island, Pulau Liat, being close enough for crew and passengers to be transferred safely to shore. In an uncanny resemblance to the Medusa wreck, a raft was used in the evacuation in addition to the ship’s boats. On this occasion however, order and discipline prevailed. Provisions and freshwater were at a premium however and it was decided that the boats would head for Batavia (now Djakarta), the Dutch administrative centre in Java, 200 miles to the south, to organise a rescue. Amehurst joined them.

Engraving from one of Surgeon Macleod’s illustrations

Captain Maxwell had remained on the island and now organised a return to the wreck to recover whatever supplies remained as there were still some 200 mouths to feed. The attempt was interrupted by the arrival of Malay pirates and the salvage party, which had been unarmed, had to beat a hasty retreat. The pirates looted the wreck and burned it thereafter. Fearing further pirate attack, Maxwell supervised construction of a stockade – called appropriately “Camp Maxwell” – and readied it for defence. Another salvage party managed to recover some flour and wine from the Alceste’s burned-out hulk but the supplies-situation remained critical.

The anticipated pirate attack came on 26 February. A sortie led by Alceste’s second lieutenant led to an initial repulse – with several pirates killed – but further pirate reinforcements arrived thereafter. They made no attempt to land, contenting themselves with firing swivel guns towards the stockade. Yet more pirates arrived and on 1 March an assault, which promised to be overwhelming, seemed imminent. It was at this critical juncture that a ship was seen approaching. Her appearance, and a brief attack by Alceste’s marines, broke the pirates’ resolve and they fled. The vessel turned out to be an East-Indiaman, the Ternate, which Amehurst had encountered in Batavia. It was to here she returned the castaways – not a single life had been lost – and Amehurst chartered another ship, the Caesar, to take them back to Britain.

An engraving from one of Surgeon MacLeod’s illustrations

The Caesar put in to St. Helena on her voyage home and both Amehurst and Maxwell had an audience with the ex-Emperor Napoleon, now in his second year of exile there. Napoleon complimented Maxwell on his achievement and hoped that he would be exonerated (as he was to be) in the inevitable court-martial for her loss. He also referred admiringly – and sportingly – to Maxwell’s capture of the French Pomone in 1811. It was to Amehurst, when discussing his failed mission, that Napoleon made his celebrated remark “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep. For when she wakes, she will shake the world” – a prophesy which has to come to pass in our own day.

Maxwell was rightly hailed as a hero, was knighted in 1818. He was however seriously injured by a paving stone thrown from a mob opposing him when he stood for Parliament that same year. He returned to naval service and held a number of responsible positions but he never recovered from the paving stone injury. He died at 56 – too young. Amherst was to serve as Governor-General of India from 1823 to 1828.

And now, when we admire Géricault’s “Raft of the Medusa” we should remember the Alceste also. She and her gallant crew deserve it.

Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?Click as below for details:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au 1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Cut off from the main Danish Army, and refusing to use the word ‘retreat’, a resolute commander withdraws northwards. Harried by Austrian cavalry, his forces plod through snow, sleet and mud, their determination not to be defeated increasing with each weary step . . .

1864 – Political folly has brought war upon Denmark. Lacking allies, the country is invaded by the forces of military superpowers Prussia and Austria. Cut off from the main Danish Army, and refusing to use the word ‘retreat’, a resolute commander withdraws northwards. Harried by Austrian cavalry, his forces plod through snow, sleet and mud, their determination not to be defeated increasing with each weary step . . .

Across the Atlantic, civil war rages. It is fought not only on American soil but also on the world’s oceans, as Confederate commerce raiders ravage Union merchant shipping as far away as the East Indies. And now a new raider, a powerful modern ironclad, is nearing completion in a British shipyard. But funds are lacking to pay for her armament and the Union government is pressing Britain to prevent her sailing . . .

But Denmark is not wholly without sympathisers. Britain’s heir to the throne is married to a Danish princess. With his covert backing, British volunteers are ready to fight for the Danes. And the Confederacy is willing to lease the new raider to Denmark for two months if she can be armed as payment, although the Union government is determined to see her sunk . . .

Just returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies, the young Nicholas Dawlish is induced to volunteer and is plunged into the horrors of a siege, shore-bombardment, raiding and battle in the cold North Sea – notwithstanding divided loyalties . . .

In other books of the Dawlish Chronicles series, Dawlish is met as an experienced and resourceful officer, but in 1864 he is still an innocent. But he will need to learn fast . . .

For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auBelow are the eleven Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are aailable in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Discipline and heroism in the aftermath of the loss of HMS Alceste appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 7, 2023

Battling the curse of the Riff Pirates 1848-51

The Barbary pirates of North Africa were a scourge to maritime trade for many centuries. It was only in the nineteenth century that major naval and military campaigns – most notably the US Navy’s and Marine Corps’ intervention on “the Shores of Tripoli”, the Anglo-Dutch action against Algiers in 1816 and the French conquest of Algeria in the 1830s – largely put an end to the menace. The qualification “largely” is however important as piracy did continue, albeit on a more spasmodic basis and limited scale than previously.

Anglo-Dutch attack on Algiers, 1816, commanded by Lord Exmouth (Edward Pellew), by Thomas Luny (1759-1837)

Morocco was still independent through most of the nineteenth century and pirates still operated off its Northern Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts – known as the Riff area – in much the same way that Somali pirates have done in our own time. The proximity to important shipping routes passing through the confines of the Straits of Gibraltar or down the African coast ensured potentially rich pickings. Two examples, from as late as 1848 and 1851, and involving the Royal Navy, illustrate the risks to small merchant ships operating in the area. These will be detailed later in this article.

In both these cases, action was undertaken by paddle sloops, a new type of ship, of which 49 were built for the Royal Navy between 1830 and 1851. Though made up of individual classes, these vessels were generally similar as regards tonnage and length – typically less than 1000-tons and of approximately 180-feet long. They carried both sail and steam, the latter power in the form of a reciprocating engine of around 400-horsepower and driving paddlewheels.

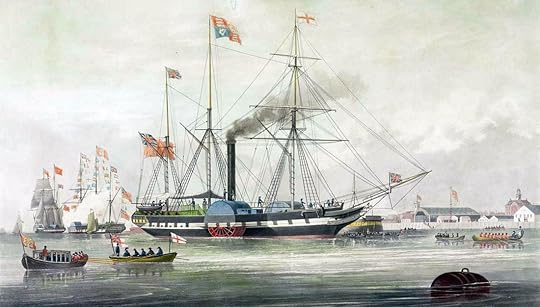

Paddle sloop HMS Trident carrying Queen Victoria on a visit to Woolwich Dockyard in 1842. Note size and vulnerability of paddlewheels. (Drawing by William John Huggins)

Though not intended for ship-to-ship combat, since their paddlewheels provided large and vulnerable targets, they carried a powerful armament for their size, typically four 32-pounder or 8-inch smoothbores. With this gun power, and with a crew of 130, of whom a major proportion could be sent ashore as “bluejackets” to constitute small naval brigades, they were ideally suited for action against shore targets or poorly armed adversaries. They saw an amazing range of action – one was to be the first steamer to circumnavigate the globe while others saw action in the Black Sea, North Pacific, Baltic against the Russians in the Crimean War and against the Chinese in the Arrow War whileothers still did valuable survey duty. This surveying, which produced maritime charts, which in updated form, are still in use today, was one of the greatest – and often forgotten and underestimated – achievements of the nineteenth-century Royal Navy.

“A trading brig drifting into a Continental harbour” by Charles John De Lacy (1856-1929) – the unfortunate Three Sisters mighthave looked generally similar.

In 1848 a British trading brig, the Three Sisters, was seized by pirates off the Riff coast. Her master and crew managed to escape but the vessel herself was towed close in to the shore. The duty of retaking her was entrusted to a Commander McCleverty, captain of the paddle sloop HMS Polyphemus. On moving in, he found a force of 500 pirates and tribesmen drawn up on the shore to defend their prize. As Polyphemus neared she was subjected to a hail of musketry. She responded with grapeshot and canister – the ideal method of attack on masses of men – and drove them back. Boats were now sent in under the command of a Lieutenant Allen Gardner to board the Three Sisters and take her out to sea. The pirates and their confederates had now regrouped and opened fire from the cover of rocks, wounding an officer and seven seamen as the oar-propelled boats towed the brig to the Polyphemus. It was a classic example of a small but effective anti-piracy action

Three years later, in 1851, a more serious act of piracy resulted in several deaths and the enslavement of the remainder of the crews, when the brigantine Violet and the schooner Amelia were captured off the Riff coast. When news of this was received at Gibraltar, another paddle slop, HMS Janus, commanded by a Captain Powell, was sent to retaliate. Both of the hijacked vessels were found wrecked on shore but Janus destroyed a number of pirate craft in the vicinity with gunfire. Others were drawn up on the shore and boats were sent in to destroy them. Large numbers of pirates and tribesmen had gathered however and they launched an attack so furious that the landing party had to retreat to Janus, with Captain Powell himself and some of his crew being wounded. The only bright spot was the liberation of the Violet’s crew. It would be interesting – and probably horrifying – to know what became of their counterparts from the Amelia.

These cases were typical of dozens of small and often bloody actions undertaken by the Royal Navy in this period. Forgotten today, they demanded initiative, courage and supreme professionalism, creating in the process a cadre of officers and seamen second to none.

And the paddle sloops? Their day was done by 1860, by which time the screw propeller, with the advantage of being hidden below the waterline, and thus less vulnerable to gunfire, reigned supreme. In their time they had rendered valuable service and they deserve to be remembered with respect.