Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 15

October 9, 2020

Guest Blog by Penelope Fisher – Lord Fisher

Guest Blog by Penelope Fisher“Sea Lord and Me”Introduction by Antoine Vanner:

Guest Blog by Penelope Fisher“Sea Lord and Me”Introduction by Antoine Vanner:

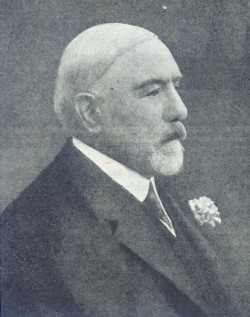

Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher Copyright R.Fisher

I have been fascinated for decades by the character and achievements of Admiral Lord John “Jacky” Fisher (1841 – 1920). A human whirlwind who revolutionized not just the Royal Navy, but the entire course of naval technology, by his creation of the Dreadnought battleship concept. His active career extended from the 1850s to World War 1. He joined a navy which officers who had fought in the Napoleonic Wars still held commands, yet lived to command a navy himself that utilised submarines, aircraft and wireless as well as surface warships of all types. He has been an inspiration for the Dawlish Chronicles novels, and in Britannia’s Spartan we meet him at the age of eighteen in the assault on the Taku Forts in China in 1859. It is therefore with the greatest pleasure to welcome, as guest blogger, Admiral Fisher’s great-great granddaughter, the film-maker Penelope Fisher, to write about her illustrious forebear. She is currently involved in a project to make a film about him (as mentioned in article below). I hope you’ll enjoy her article as much as I have.

Over to Penelope!

SEA LORD & ME By Penelope FisherWhat a delight to be invited by Antoine to write a guest blog about Admiral Lord John “Jacky” Fisher, my dynamic, determined infamous great great grandfather. He is one of Antoine’s heroes and inspirations for his fictional character Nicholas Dawlish, who is an absolutely fascinating protagonist.

Jacky was a huge personality, an exceptional man. He devoted his life and career to the defence of Britain and his huge, energetic personality shaped history. He was a fierce, stubborn, determined, energetic, charming and pragmatic man.

Admiral Lord “Jacky” Fisher was one of the most famous men of his age; an innovator who drove the transformation of the Royal Navy prior to the First World War, introducing the new big gun battleships while reforming gunnery, training and conditions. Born in Ceylon, he was sent away to live with his maternal grandfather in London and worked his way up through the ranks to become First Sea Lord. He was a colourful character with firm opinions, capable of inspiring loyalty and enmity in equal measures.

Having retired in 1910, he was brought back as First Sea Lord in October 1914 for a second term by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. Yet within the space of six months, the relationship between the two men had broken down over the failure of the Dardanelles operation, ultimately costing them both their jobs.

Long and Varied Life

H.M.S Calcutta – Fisher served on board as a Naval Cadet 1854-1856. Like others of his generation, he joined a navy commanded by veterans of the Napoleonic Era

There are truly so many stories and components of Jacky’s life, which I have spent many years researching to understand him as a man and one of the greatest Admirals the British Navy has ever seen. Jacky lived a long and varied life similar to Dawlish so there are lots of areas of his life which I’m sure you will find fascinating and already know a lot about, from when he joined the Navy at the age of 13, surviving the China War, captained his first ship at 19, to rising the ranks of the Navy as an outsider of the aristocracy, when he first became known to the British public in 1882 at the bombardment of Alexandria during the Egyptian War, his work with torpedoes and gunnery school, his swift action after the Battle of Coronel to send HMS Inflexible and HMS Invincible to the Falkland Islands to intercept the Imperial German Fleet and Admiral von Spee with great success, and his nickname “the godfather of oil” for converting ships from coal to oil.

Fisher served on HMS Warrior as a lieutenant, 1863-64. She is preserved today at Portsmouth

Friend of King Edward VII

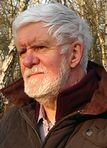

HMS Dreadnought

I believe he and the family loved their time in Malta when he was Commander of the Mediterranean fleet and of course becoming the father of the first all big gun battleship HMS Dreadnought, a game changer in the early 20th century arms race. He is well known as a long standing devoted friend to King Edward VII and confidant of Queen Victoria, his mother. His life-long rivalry with Admiral Charles Beresford is well documented. He was the first person to use the expression OMG (Oh My God) “OMG shower it on the Admiralty”

He was married for 52 years to Kitty Fisher, but in spite of being a religious man, lived with Nina, Duchess of Hamilton, 30 years his junior, with whom he was infatuated.

Head of the British Navy What an extraordinary life he lived from that little boy who left his parents in Ceylon at the age of six to surviving all that life threw at him to become head of the British Navy and sadly for all his hard work to disappear in history with the disaster at Gallipoli. When he died in 1920, he was given a public naval funeral at Westminster Abbey (see illustration of cortege passing Nelson’s column.) and was buried at Kilverstone Hall, his Norfolk home.

What an extraordinary life he lived from that little boy who left his parents in Ceylon at the age of six to surviving all that life threw at him to become head of the British Navy and sadly for all his hard work to disappear in history with the disaster at Gallipoli. When he died in 1920, he was given a public naval funeral at Westminster Abbey (see illustration of cortege passing Nelson’s column.) and was buried at Kilverstone Hall, his Norfolk home.

Perhaps because he died so soon after the war, perhaps because popular history has focused on the Western Front, or maybe because he did not command a fleet in battle, Fisher is now either forgotten or seen only as a footnote in biographies of Winston Churchill.

Sea Lord: the film

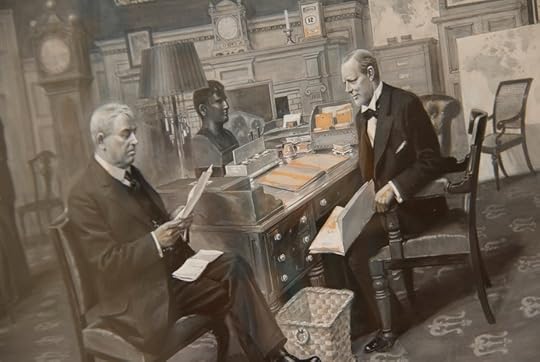

Fisher and Churchill, early in WW1

Inspired to tell his story through film since I was young, I am now producing “Sea Lord” through my film company Trident Films. This charts the remarkable rise and calamitous fall of Admiral John ‘Jacky’ Fisher, First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty. It is a dramatised account of the defining eight months of Fisher’s life from October 1914 to May 1915. A compelling and universal story of a self- made man’s attempt to write his name in history, the film explores how patriotism, conviction and bloody-mindedness which lifted Jacky Fisher to one of the great offices of state, but it was also the cause of his ultimate downfall. A man of many words, strategic strength, insight and religious beliefs I see this as a true intimate historical character-driven biography of Jacky.

The pull to bring Jacky’s character back to life is tremendous. Oh to have been a fly on the wall in the War Council and private meetings between Fisher and Churchill and to fully experience the man behind the Naval uniform!

The screenplay for “Sea Lord” has been professionally written and Trident Films is currently seeking investors and production companies to come on board. For more information please visit www.tridentfilms.co.uk; Twitter @FilmsTrident ; Instagram @trident_films_

“A Veritable Volcano” – online free event Tuesday 20 October 3pm to 5pmIn collaboration with the Churchill Archives Centre, I have organised an exciting online free event “A Veritable Volcano: The Life and Legacy of Admiral Lord ‘Jacky’ Fisher”. The event on Tuesday 20 October (3pm to 5pm) is being held to mark the centenary of Admiral Fisher’s death and to celebrate the transfer of new material to the Churchill Archives Centre. I will be appearing with my father Lord Patrick Fisher in a video where we will be discussing the new documents relating to the life of Admiral Fisher.Speakers at the symposium include Professor Barry Gough, Professor Andrew Lambert, Dr John Brooks, Captain Peter Hore, Professor Matthew Seligmann and Rear Admiral Dr Chris Parry. Closing remarks will be given by Admiral Sir Jock Slater (former First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff)Please register for tickets by clicking belowhttps://www.tridentfilms.co.uk/events Biography:

Penelope Fisher: Great, Great Granddaughter of Admiral Lord John “Jacky” Fisher

Penelope Fisher: Great, Great Granddaughter of Admiral Lord John “Jacky” Fisher

Producer: “Sea Lord” Trident Films

Penelope Fisher set up Trident Films this year with the aim to produce her own films, the first of which will be “Sea Lord.”

Her credits include working as Production Assistant to Timothy Burrill, producer of “La Vie en Rose”, the Edith Piaf biopic and Babylon AD starring Van Diesel.

Before this, she worked for Icon Films in the Entertainment and Distribution UK department for many major films such as “Apocalypto” directed by Mel Gibson. Other movies included “Romance and Cigarettes” starring Kate Winslet and Susan Sarandon, directed by John Turturro and “It’s A Boy Girl Thing” with Elton John as executive producer, featuring songs from his back catalogue. Penelope’s role entailed delivering the trailers and prints of films to different territories, coordinating with distribution departments and disseminating marketing material internationally.

Penelope studied film-making at the London Film Academy, attaining Distinction

The post Guest Blog by Penelope Fisher – Lord Fisher appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 2, 2020

HMS Pelorus, 2000 miles up the Amazon, 1909

A British cruiser 2000 miles up the Amazon:HMS Pelorus 1909

A British cruiser 2000 miles up the Amazon:HMS Pelorus 1909[image error]As a prisoner on HMS Bellerophon, prior to his exile on St. Helena, Napoleon told its commander, Captain Maitland, that, “If it had not been for you English, I should have been Emperor of the East; but wherever there is water to float a ship, we are sure to find you in our way.” This ability was to manifest itself on numerous occasions up to the middle of the next century. Small Royal Navy units were to operate in China on the Upper Yangtze, on Lake Tanganyika and on the Nile in the Sudan, in the Caspian Sea and on remote Russian rivers during the Russian Civil War and they were to reach Vienna, some 800 miles up the Danube from the Black Sea at the end of World War 1. More impressive of all these achievements was however that, not of a small gunboat, but of a cruiser of over 2000 tons that reached Peru in 1909. This does not perhaps seem remarkable – Peru has a long coast on the Pacific Ocean – until it is realised that the approach was from the east, up the Amazon River, almost to its headwaters.

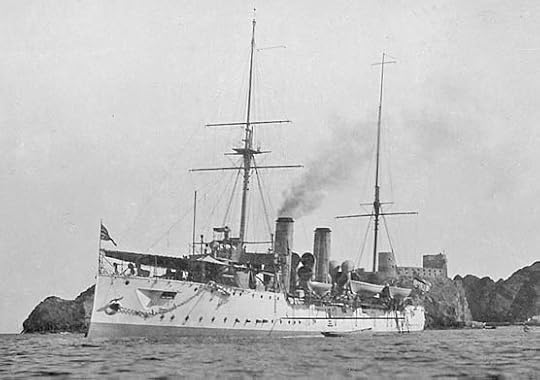

HMS Pelorous in late 1890s – resplendent in “Victorian Livery of black hull, white upperworks and buff funnel

HMS Pelorous in late 1890s – resplendent in “Victorian Livery of black hull, white upperworks and buff funnel

Launched in 1896, the name ship of a class of eleven, HMS Pelorus was a third-class protected cruiser. “Protected” meant that the vessel’s sides were not armoured but that an arched armoured deck protected the boilers, engines and other vital areas. “Third Class” implied a small vessel, suited to commerce-protection duties, or for scouting for larger units. Pelorus and her ten sisters were 2135-ton, 300-feet long vessels and their 7000-hp gave them a top speed of 20 knots. Crewed by 224 men, their main armament consisted of eight 4-inch breech loading guns for anti-ship use, supplemented by eight 3-pounder quick-firing weapons for defence against attack by torpedo boats. They also carried two 18-inch torpedo tubes.

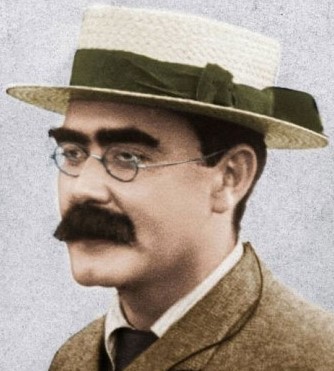

Kipling in the 1890s

HMS Pelorus served almost ten years in the “Channel Fleet” – that tasked with operations in the North Atlantic and the North Sea but in 1906 she was posed to the Cape of Good Hope Station. Although only a small unit in a navy made up of hundreds of ships, she had already achieved fame through a series of articles published in the Morning Post newspaper, and subsequently gathered into a small book entitled “A Fleet in Being”. The author was the writer and poet Rudyard Kipling, who was a friend of a Captain E.H. Bayley, who was then commanding HMS Pelorus. In 1897, as a guest of Bayly, Kipling was on board HMS Pelorus for two weeks during the Fleet’s summer exercises and he was to repeat the experience the following year. His writings about his time on HMS Pelorus give fascinating insights into shipboard naval life in the late nineteenth-century. There if however a strong impression of forced enthusiasm, of determination to see everything through rose-tinted glasses, and to give an epic quality to what were, in reality, peacetime manoeuvres. As with much of Kipling’s writings the treatment of individuals is condescending and patronising, and leaves a sour taste with at least one modern reader.

Manaus Opera House – best known symbol of the Amazon rubber boom

Manaus Opera House – best known symbol of the Amazon rubber boom

(photograph by Pontanegra via Wikipedia)

In 1909 the “Rubber Boom” in Brazil and Peru was in full swing. The rubber in question grew wild in the forests lining the Amazon and its tributaries as plantation-cultivation of rubber in Malaya had not yet taken off on the large scale it was to become. The arrival of the automobile had pushed the demand for rubber to unprecedented levels and fortunes were made by anybody who could organise its collection from trees growing wild in the forest. This was the era when the city of Manaus was to build its exotic opera house at the confluence of the Amazon and the Rio Negro, the period immortalised in Werner Herzog’s stunning movie “Fitzcaraldo”. British commercial firms were active in the trade and it was only by the investigations in 1910 and 1911 of a British consul, Roger Casement, that the true nature of their activities was revealed.

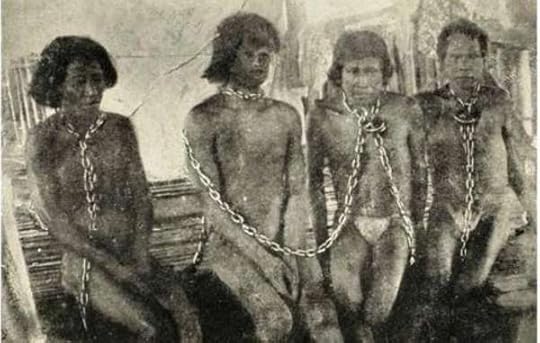

Enslaved Peruvian Indians during the rubber boom

Enslaved Peruvian Indians during the rubber boom

In the Putomayo area of north-eastern Peru Casement found that indigenous tribes were begin forced into unpaid labour – essentially slavery – to collect the forest rubber. Abuse of these innocent people included starvation-level feeding, physical abuse, rape of women and girls, branding and casual murder. The chief offender was the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC), which had been registered in Britain in 1908 and had a British board of directors and numerous stockholders. Casement’s report aroused public outrage in Britain but what in the end brought a complete end to the abuses was the arrival of cheaper, plantation-grown rubber from Malaya that made wild-rubber collection economically unattractive. (Casement was to be knighted for the exposure of these abuses, and of similar atrocities in the Congo. His career was to end in hanging in 1916 as an Irish Republican working closely with Imperial Germany).

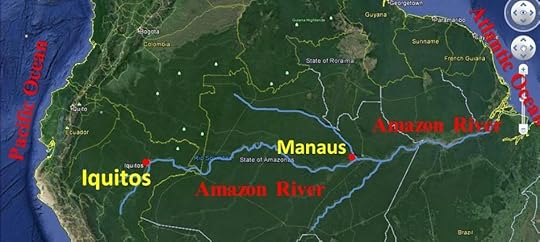

Pelorus’s 200-mile route up the Amazon

Pelorus’s 200-mile route up the Amazon

Casement’s uncovering of the realities of the rubber trade were still a year and more in the future when, in February 1909, HMS Pelorus arrived in the eastern Peruvian town of Iquitos, on the upper reaches of the Amazon. The objective of this good-will visit was to help promotion of British exports to Peru as the rubber boom had created an enormous demand for goods from the industrialised world. The arrival of a sophisticated warship was ample proof of similarly sized, or smaller, steamships, being well capable of following the same route. The achievement was a spectacular one – HMS Pelorus had navigated some 2000 miles of winding, often forest-lined, river from the river’s estuary on the South Atlantic coast. On arrival at Iquitos the nearer ocean was the Pacific, a mere 600 miles away, but with the Andes mountain range lying between. Despite its isolation, Iquitos, a town of 30,000, boasted electric lighting, tramways, a theatre and, apparently, a cinema. The seven day visit followed the usual pattern for such “showing the flag” missions – dinners, speeches, an open-day for the public, a football match, a concert and a “cinematograph show”. (One wonders what was shown at the latter.)

HMS Perseus, sister of HMS Pelorous, in tropical livery of white hull and ochre funnels. On her Amazon voyage HMS Pelorus was likely to be similarly painted. (Background suggests to Antoine Vanner that this photograph was taken at Muscat)

HMS Pelorus needed to replenish her bunkers before embarking on the return trip. Remarkably, she was to do so with Welsh coal which was apparently a normal import to the area from Britain for use on river craft. The costs of its transportation raised the price to more than four times its British level. With congratulations, well-wishes and handshakes all round, HMS Pelorus then commenced her voyage homewards, docking at Manaus and Belem en route to the Atlantic. She spent six-weeks in total on the Amazon and was a matter of pride for both captain and crew that the river passage had been a healthy one, with minimum sickness and, despite the prevalence of mosquitoes and insects, no cases of fever.

HMS Pryamus, sister of HMS Pelorous, in dull grey in 1914.

The Amazon voyage was HMS Pelorus’s last moment in the limelight. By the time of outbreak of war in 1914 she and the few of her sisters still in service were old, obsolete ships suited only to secondary duties. She was scrapped in 1920.

One wonders if the Indians in the Putomayo area, north of Iquitos, who laboured in slavery for the London-based Peruvian Amazon Company, ever heard of the visit. Even if they did it is unlikely that they would have been able to go on board during HMS Pelorus’s open day.

Do you enjoy Naval fiction?The eight novels (so far) of the Dawlish Chronicles series are set in the years 1864 to 1885 and are linked to real events of the period. It’s a time of rapid political, social and technological change, with established powers striving to maintain their position as new competitors appear and alliances shift. And in these challenging times, a Royal Navy officer, Nichols Dawlish, is intent on building his career…Click on the banner below for more detailsClick on any of the cover images below to join the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list and to receive six free short stories for downloading on your Kindle, computer or tablet.The post HMS Pelorus, 2000 miles up the Amazon, 1909 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 11, 2020

Nightmare at Sea 1874

Baron Walter Runciman

In a recent bog (click here to read it) I drew on the memoirs of Baron Walter Runciman (1847 –1937), a classic case of a poor boy of high initiative “making good”. Born in Dunbar, Scotland, he ran away to sea at the age of twelve. A ship’s master himself by 21, he founded a shipping line and in due course became a major force in the British mercantile industry up to his death. On the way he was elected also as a Liberal Member of Parliament and was subsequently raised to the House of Lords.

Runciman’s reminiscences, published in 1905, leave no doubt as to the brutalities of life in the merchant service in the nineteenth century. They sweep away any notions we may have of “The Romance of the Sea”, as beloved by so many armchair-bound Victorians. One story is particularly harrowing – it has much about it of a Joseph Conrad novel or short story. and I paraphrase it below, his own words being indicated in italics.

Small trading brigs were vulnerable in extreme weather. Here is the wreck of the

Copeland

at South Shields,1861, a vessel probably similar to the Ocean Queen featured in this article (Painting by John Newington Carter)

Small trading brigs were vulnerable in extreme weather. Here is the wreck of the

Copeland

at South Shields,1861, a vessel probably similar to the Ocean Queen featured in this article (Painting by John Newington Carter)

“There are, however, phases of bravery, endurance, and resourcefulness that test every fibre of the seaman’s versatile composition,” Runciman writes, “The pity is so much of it is lost to us, but this again is owing to the sailor’s habitual reticence about his own career.” A characteristic instance of this occurred to me about six months ago. I had business in a shipyard, and the gateman who admitted me is one of the last of the seamen of the middle of the century.”

This man had been “for many years master of sailing vessels belonging to a north-east coast port. He is a fine-looking, intelligent old fellow. I knew him by repute in my boyhood days; he had the reputation then of being a smart captain, and owners readily gave him employment. After greeting me with sailor-like cordiality, he commenced to converse about the old days, and as the conversation proceeded the weird sadness of his look gradually disappeared, his eyes began to sparkle, and joy soon suffused his ruddy face.”

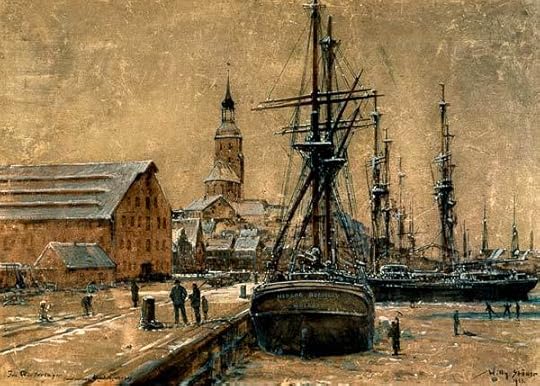

Small traders at the Baltic port of Wolgast (by Willy Stöwer 1864 – 1931)

Small traders at the Baltic port of Wolgast (by Willy Stöwer 1864 – 1931)

Runciman was however “reluctant to break the charm of it by introducing a subject that might be distasteful to him. It was my desire to hear from his own lips a tale of shipwreck which is virtually without parallel in its ghastly tragedy. I instinctively felt myself creeping on to sacred ground. As soon as I mentioned the matter his countenance changed and he became pensive. . . I saw the moisture come into his eyes and his breast heave with emotion, and it made me wish that I had not reminded him of it. At length he began to unfold the awful story.”

The old gateman had been master of a brig called the Ocean Queen. In her he sailed from a port in the Gulf of Finland in December, 1874, laden with timber. Close to the Swedish island of Gotland, a storm from the west “battered the vessel until she became water-logged and dismasted. The crew lashed themselves where they could, and huddled together for warmth to minimise the effects of the biting frost and the mad turmoil of boiling foam which continuously swept over the doomed vessel, and caked itself into granite-like lumps of ice. At intervals they would try to keep their blood from freezing by watching a “slant” when there was a comparative smooth, and run along the deckload a few times, keeping hold of the life-line that was stretched fore and aft for this purpose”

The horror of shipwreck doesn’t change through the ages. Two centuries before the loss of the Ocean Queen, the nature of the nightmare was conveyed by Pieter Mulier II (1637 – 1701).

The horror of shipwreck doesn’t change through the ages. Two centuries before the loss of the Ocean Queen, the nature of the nightmare was conveyed by Pieter Mulier II (1637 – 1701).

The storm abated after twelve hours “but they were without food and water, and no succour came near them. They held stoutly out against the privations for two days, then one after another began to succumb to the combined ravages of cold, thirst, and hunger. Some of them died insane, and others fought on until Nature became exhausted, and they also passed into the Valley of Death. There were now only the captain and a coloured seaman left.”

The wind – apparently from the north, now drove the shattered brig southwards towards the German coast. “On the fifth morning after she became water-logged the wreck stranded on a sandy beach two hours before daylight. The captain and his coloured companion attached themselves to a plank, and by superhuman effort reached the shore. They buried their bodies up to the waist in sand under the shelter of a hill, believing it would generate some warmth into their impoverished systems. Their extremities were badly frostbitten, and when they were discovered at daylight by a man on horseback who had been attracted to the scene of the wreck, they were both in a condition of semi-consciousness. He galloped off for assistance, and speedily had them placed under medical treatment, and under the roof of hospitable people.”

A small trading brig in a rough sea – merchant vessels in the era before wireless were “on their own” once out of sight of land. The great Ivan Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900) conveys this memorably.

A small trading brig in a rough sea – merchant vessels in the era before wireless were “on their own” once out of sight of land. The great Ivan Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900) conveys this memorably.

The consequences were dreadful for both men: A few days’ rest and proper attention made them well enough to be removed to a hospital. It was soon found necessary to amputate both of the coloured man’s legs, and also some of his fingers. The captain had the soles of his feet cut off; and he told me that he always regretted not having the feet taken off altogether, as he had never been free from suffering during all these years. He said the doctor advised it, but that he himself was so anxious to save them that he preferred to have the soles scraped to the bone, hoping that the diseased parts would heal; ‘but,’ said he with an air of sober melancholy, ‘they never have.’”

Runciman indicated that he had “been obliged to confine myself to a brief outline of this tale of shipwreck. There are incidents of it too painful to relate, and I am quite sure I am consulting the wishes of the narrator by abstaining from going too minutely into detail. The main facts are given, and they may be relied on as absolutely true.”

One wonders how many similar stories of extreme suffering at sea have been lost to us. The image of the crippled old captain eking out his last days as a gatekeeper, and of what the ultimate fate would have been of the man with him, is both haunting and disturbing.

Naval Fiction of the Age of Fighting SteamThe eight books of the Dawlish Chronicles series published so far are set the 1860s, 1870s and 1880s. These were the decades of massive technological change and of bitter conflicts , both major and minor. If you’re a Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime subscriber you can read any of the eight Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details.

If you’re a Kindle Unlimited or Kindle Prime subscriber you can read any of the eight Dawlish Chronicles novels without further charge. They are also available for purchase on Kindle or as stylish 9 X 6 paperbacks.Click on the image below for more details.

Click on any of the cover images below to join the

Dawlish Chronicles

mailing list and to receive six free short stories for downloading on your Kindle, computer or tablet.

Click on any of the cover images below to join the

Dawlish Chronicles

mailing list and to receive six free short stories for downloading on your Kindle, computer or tablet.The post Nightmare at Sea 1874 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 7, 2018

“Poor Jack Spratt” at Trafalgar

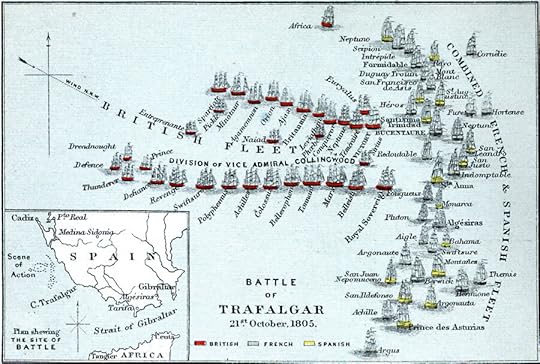

One’s mental image of the Battle of Trafalgar, when Nelson’s defeat of the French and Spanish fleets established the supremacy of British naval power for a century, is dominated by the death of Nelson himself. In this enormous battle – thirty-three British ships against forty-one of the enemy – a myriad of other dramas were played out. One that was well known at the time, and which deserves not to be forgotten, involved “Poor Jack Spratt” of HMS Defiance.

The opening of the battle – Nelson’s and Collingwod’s divisions breaking into the French and Spanish line. Defiance and Aigle can be clearly identified near the ends of their respective columns.

Eleventh in the second division, commanded by Vice-Admiral Collingwood, this ‘74’ attacked a French ‘74’, the Aigle, near the end of the French and Spanish line. These ships were well matched in size and gunpower – the ‘74’ two-decker ships of the line were the backbone of all major navies. Commanded by Captain Philip Durham (1763-1845), the Defiance had as Master’s Mate a James Spratt (1781-1853). The position was not one held by a commissioned officer and the master himself would have held a warrant. Though a veteran of the Battle Copenhagen, Spratt was still a Midshipman at the age of 34, a fact that implied that his naval career was going nowhere. He seems to have been popularly known as “Jack”, like the character in the nursery rhyme.

The Defiance was to have the best of the broadside exchanges. The Aigle’s fire of the latter had slackened so much that, although her colours were still flying, her power to resist further was almost exhausted. Both ships were now “within pistol shot” and Captain Durham saw that boarding would decide the issue. There was however a dead calm, and Defiance’s boats had been too badly damaged to launch. Hoping however for a slight breeze to bring the ships together, Durham had a fifty-man boarding party mustered. At this point, Master’s Mate James Spratt volunteered to swim across to Aigle. Durham at first refused initially, but finally consented to Spratt’s pleas.

Spratt now called out ” Boarders follow me!” and with his cutlass in his teeth and with a boarding axe in his belt leaped overboard. Whether he was not heard in the continuing roar of battle, or whether discretion proved the better part of valour, nobody followed. Spratt struck out for the Aigle however, heading for the stern. He was soon seen climbing up the rudder chains of the French ship and disappearing into one of her stern windows.

This painting by Nicholas Pocock (1740-1821) gives a good impression of the individual combats during the latter stages of the battle

A slight breeze had now arisen, enough to allow Durham to manoeuvre Defiance alongside Aigle to launch his boarders. Initially repulsed, they succeeded on the second attempt. In the meantime, Spratt had found his way up through internal passages to Aigle’s poop. Confronted by three French marines with fixed bayonets, he avoided their charge. He put two out of action but the third grappled with him. Together they crashed from the poop to the quarter-deck. The fall broke the unfortunate Frenchman’s neck but Spratt escaped uninjured.

Defiance’s boarding party were now on Aigle and Spratt joined them in vicious hand-to-hand fighting on the quarter-deck. O’Byne’s “Naval Biographical Dictionary” of 1849 records elegantly that Spratt “had the happiness of saving the life of a French officer from the fury of his assailants. Scarcely had he discharged this act of humanity when an endeavour was made by a grenadier to run him through with his bayonet. The thrust being parried, the Frenchman presented his musket at Mr. Spratt’s breast; and although the latter succeeded in striking it down with his cutlass, the contents passed through his right leg a little below the knee, shattering both bones.” Desperately wounded, Spratt stumbled into the space between two guns and managed to fend off further attacks until rescued by the other boarders.

The great naval painter William Lionel Wyllie (1851 – 1931) gave a sea-level view of the battle

The great naval painter William Lionel Wyllie (1851 – 1931) gave a sea-level view of the battle

Aigle stuck her colours – Captain Durham, in a private letter, stated that he saw the wounded Spratt holding his shattered leg, and calling out “Poor Jack Spratt is done up at last.” He appears to have got back to Defiance by swinging himself down by one of the boat-tackle falls to land on a lower-deck port which happened to be open. From there he was carried to the cockpit, where the surgeon has set up his station. Spratt refused to allow his injured leg to be amputated. In great pain, he was carried back to Gibraltar. He spent seventeen agonising weeks in the naval hospital there, emerging with one leg considerably shorter than the other.

In the meantime, Aigle had come to a brutal end. On the day after the battle the French prisoners overpowered the British prize crew, and recaptured her. Their victory was short-lived – caught in the storm that destroyed many of the other damaged ships, she was wrecked on the following day.

Though not himself a witness, Turner’s great Trafalgar painting well conveys the fury of battle

Thomas A.B. Spratt

Spratt’s heroism was rewarded with a commission as a lieutenant. His injury kept him on duty ashore for the next seven years. In charge of a signalling station, he invented a new method of semaphoring for which he received a silver medal for the Society of Arts. He returned to sea in 1813, on the North American Station, but his disability necessitated him being invalided back to Britain for less stressful duty.

Spratt had married in 1809 and one of his sons, Thomas A.B. Spratt (1811 – 1888) rose to the rank of vice-admiral and gained renown as a hydrographer and geologist. His greatest achievement was however for the survey that led to “Spratt’s Map”, which was the basis for the discovery of Troy.

What a life James Spratt could look back upon with pride!

New Book by Antoine Vanner – his first non-fiction titleBroadside and BoardingSmall scale action in the Age of Fighting Sail 1740 – 1815 Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

This new book refers to an earlier era, the Great Age of Fighting Sail that spanned the years 1740 – 1815. It tells largely forgotten real-life stories of small-scale actions, not of the great fleet battles like Trafalgar. Many involve little more than a handful of resolute men fighting their own lonely and desperate battles, small epics that still inspire.

Broadside and Boarding is not a formal history but a collection of some eighty articles. Reading times vary from ten to fifteen minutes. They’re ideal for coffee or tea breaks, for when one is waiting for a train or flight, for delays of all kinds and for when mood precludes a prolonged reading session. This is a book that belongs on bedside tables and in guest rooms, in cars’ glove compartments or, in Kindle format, in briefcases and handbags, always readily accessible.

Uncovering these stories demanded searches not just in classic and near-contemporary histories of the time but in smaller and obscure books perhaps unopened for decades. In many cases there are direct quotes from reports or letters written in the immedate aftermath of the events involved. These are often touching and sometimes inspirational, bridging the centuries through recognition of our shared humanity.

Publication date, Kindle and Paperback, is December 7th 2024Kindle editon available for preorder at 25% discocount on later published price.Click links below for details.USA UK and Ireland Canada Australia and New ZealandThe post “Poor Jack Spratt” at Trafalgar appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

April 24, 2018

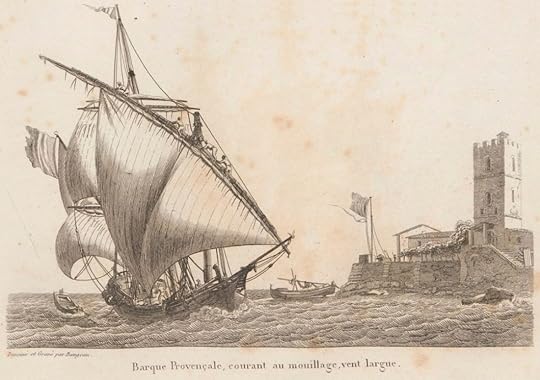

HMS Transfer: cold-blooded courage and service under four flags

Few warships can have sailed under the flags of four different nations, and to have seen action each time, in just eight years. This was however the distinction of the French-built privateer Quatre Frères, a 150-foot polacca commissioned in Bordeaux in 1796. Her name – Four Brothers – indicates that she was built by a family firm and that she might well have been used as a trader in earlier years. The polacca – a type of vessel common in the Mediterranean, and which appears often in the Aubrey-Maturin novels – could be two or three-masted, usually with a lateen hoisted on the foremast (which was slanted forward to accommodate the large lateen yard) and a gaff or lateen on the mizzen mast.

A classic Mediterranean polacca by Jean-Jérôme Baugean (1764 – 1819)

The Quatre Frères had only a short career in French service – though she did take two prizes – and she herself was captured in the Mediterranean by HMS Irresistible, a third-rate, in March 1797. She was taken into Royal Navy service, renamed as HMS Transfer and apparently re-rigged as a brig – a fact that indicates that she was probably two-masted to start with. Her armament now consisted of twelve 6-pounders.

Three-masted polacca – by Dominic Serres (1722-1793)

Lightly armed and most likely a fast sailing vessel, the Transfer was employed in carrying despatches and mail between Britain and the Royal Navy force blockading the Spanish naval base at Cadiz. It was in the course of these duties that her acting commander, a Lieutenant George Miller, was to display remarkable coolness when faced with potentially devastating odds. On 11th February 1799, HMS Transfer was returning from Britain and heading for the position where the blockading squadron was most likely to be found. Just before daybreak she found herself, in semi-darkness, in close proximity to other vessels and Lieutenant Miller assumed that they were British. As the light grew however, he realised that he was in the middle of a Spanish force which was protecting a number of merchant ships. This squadron had slipped out of Cadiz, when the British blockading force had been driven off by a gale. Before HMS Transfer could be identified as British, Lieutenant Miller had the presence of mind to run up America colours – thus giving the impression of a neutral ship. The ruse worked, though it must have taken an iron nerve to have carried it off. Miller ran past the Spanish line, as if heading directly for Cadiz, and was not challenged. Trailing the enemy squadron was what proved to be a small French privateer, the Escamoteur, armed with only three 6-pounders. Despite the proximity of the Spanish vessels, Miller attacked, boarded and captured this privateer and escaped, unharmed, to join the British squadron.

French brig-of-war by Antoine Roux (1765–1835). HMS Transfer would have looked generally similar after conversion from a polacca.

HMS Transfer saw significant action under British colours during the next three years but in 1802, during what proved to be the short-lived Peace of Amiens between Britain and France, she was sold at Malta to Ottoman Tripolitania, then coming under attack by the United States Navy in the First Barbary War. She was used as a blockade-runner but was captured in March 1804 by the brig USS Syren.

USS Syren (fourth from right) during bombardment of Tripoli, 1804. Painting by Michele Felice Cornè 1752-1845

Once again under new ownership, the ex- Quatre Frères, ex-Transfer was taken into American service as the USS Scourge. She was now turned on her previous owners and participated in US Navy’s attacks on Tripoli before being sent back to America late in 1804 for coastal duties. By the time war broke out between the United States and Britain in 1812, USS Scourge was judged unfit for further naval use and sold at auction. It would be interesting to know her ultimate fate.

Few vessels can have seen such rapid changes of ownership in an eight-year period as this small vessel did between 1796 and 1804.

New Book by Antoine Vanner – his first non-fiction titleBroadside and BoardingSmall scale action in the Age of Fighting Sail 1740 – 1815 Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

Antoine Vanner is a novelist, not a formal historian. Broadside and Boarding is hisfirst non-fiction work, though he has published twelve volumes so far of the Dawlish Chronicles series of naval adventure, set in the late 19th Century.

This new book refers to an earlier era, the Great Age of Fighting Sail that spanned the years 1740 – 1815. It tells largely forgotten real-life stories of small-scale actions, not of the great fleet battles like Trafalgar. Many involve little more than a handful of resolute men fighting their own lonely and desperate battles, small epics that still inspire.

Broadside and Boarding is not a formal history but a collection of some eighty articles. Reading times vary from ten to fifteen minutes. They’re ideal for coffee or tea breaks, for when one is waiting for a train or flight, for delays of all kinds and for when mood precludes a prolonged reading session. This is a book that belongs on bedside tables and in guest rooms, in cars’ glove compartments or, in Kindle format, in briefcases and handbags, always readily accessible.

Uncovering these stories demanded searches not just in classic and near-contemporary histories of the time but in smaller and obscure books perhaps unopened for decades. In many cases there are direct quotes from reports or letters written in the immedate aftermath of the events involved. These are often touching and sometimes inspirational, bridging the centuries through recognition of our shared humanity.

Available in Paperback and Kindle – subscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra costClick links below for details.USA UK and Ireland Canada Australia and New ZealandClick on the photo-block below to read about the entire Dawlish Chronicles series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)The post HMS Transfer: cold-blooded courage and service under four flags appeared first on dawlish chronicles.