Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 12

December 17, 2021

Bayonnaise and HMS Ambuscade action, 1798

The Bayonnaise and HMS Ambuscade action, 1798

The Bayonnaise and HMS Ambuscade action, 1798On my blog I have dealt several times with single-ship actions during the Age of Fighting Sail, the protagonists being mainly British and French, though the Americans do figure in 1812-15. In most cases British victory over the French seems to have been all but pre-ordained, for the Royal Navy had reached a peak of professionalism in this period and the French officer corps had suffered badly in the revolution, a setback from which it never fully recovered. It is therefore somewhat of a surprise to learn not only of a French vessel, the Bayonnaise capturing a British one, HMS Ambuscade, in a single-ship action, but also that the French vessel was significantly smaller and less powerful.

The climax of the action. Bayonnaise (R) rams HMS Ambuscade and the latter’s mizzen falls

The climax of the action. Bayonnaise (R) rams HMS Ambuscade and the latter’s mizzen falls

Painting by Jean Francois Hue, 1751-1823

HMS Ambuscade was, by contrast, much more powerful, a 32-gun frigate that had seen successful service against the French in the American Revolutionary War. Though her dimensions were generally similar to the Bayonnaise , and though she carried a similarly sized crew, her armament was considerably heavier – 26 twelve-pounders, a total of eight six-pounder bow and stern chasers, four eighteen-pounder carronades on the quarterdeck and two on the forecastle. In any ship-to-ship action between the two vessels the Bayonnaise might have been expected to have little chance of survival.

From August 1798, at a time when the Royal Navy’s blockade of the French coast was becoming ever more effective, HMS Ambuscade, commanded by Captain Henry Jenkins, was ordered to patrol off the French Atlantic coast. At dawn on 14th December, when she was cruising off the Gironde estuary, and expecting to meet HMS Stag, she sighted a sail. Assuming this to be the Stag, she steered closer. The newcomer was in fact the Bayonnaise which, significantly as it later proved, was carrying a 40-man army detachment in addition to her own crew. The French ship, recognising that she was outsized and out-gunned, went about and fled. A stern-chase ensued and it was not until noon that the range closed sufficiently for the first shots to be fired.

The action might have ended when HMS Ambuscade crossed Bayonnaise’s stern. This was the most vulnerable part of any sailing man-of-war, as shot crashing through the stern could run longitudinally along the entire inner decks, destroying all in their path. The manoeuvre, if successfully executed, was the deciding factor in many naval battles. It was at this moment of greatest risk that Bayonnaise’s luck kicked in. One of HMS Ambuscade’s 12-pounders burst, killing thirteen around it and destroying the vessel’s boats. In the ensuing confusion Bayonnaise headed south and a new stern chase developed. HMS Ambuscade, recovered from her setback, drew level in mid-afternoon – when, on this winter’s day, only a few hours of daylight still remained.

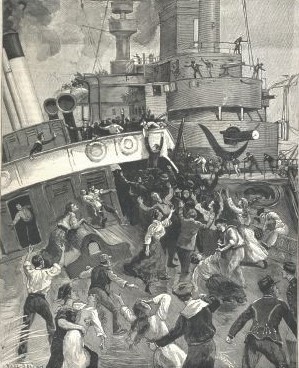

The moment of ramming (note damage to sails) – by naval artist Antoine Roux (1765-1835)

HMS Ambuscade was now sailing parallel to Bayonnaise and well placed to batter her to fragments. Desperate measures were called for if the latter was to survive. Richter, her captain, ordered sail to be backed and swung the helm hard over to port, smashing into HMS Ambuscade’s starboard flank close to the stern. Bayonnaise’s bowsprit crashed into the British frigate’s mizzen mast. It fell, and the tangle of cordage and wrecked spars locked both vessels together.

The extra men Bayonnaise carried – soldiers, accustomed to handling muskets – now proved decisive. A withering fire was directed on Ambuscade’s deck, so many of her officers being wounded that only a single lieutenant was left in command. Bayonnaise too was taking casualties – Captain Richter had an arm shot off – but the advantage now lay with her. French seamen and soldiers clambered across the bowsprit on to Ambuscade and a savage melee developed. Bayonnaise’s new-found luck continued, for a powder charge exploded on Ambuscade’s quarterdeck, inflicting yet more casualties. The fighting continued for another half-hour, but numbers told. When HMS Ambuscade’s colours were finally struck it was by her purser, the last Royal Navy officer still in action.

The most dramatic – and magnificent – representation of all

French boarders can be seen storming across the bowsprit to the Ambuscade

Painting by Louis-Philippe Crepin (1772-1851) in the Musee National de la Marine in Paris

The butcher’s bill for this action was 15 killed and 39 wounded on HMS Ambuscade while Bayonnaise had 25 killed and 30 wounded. The captains of both vessels were among the wounded, and many other officers beside. It should be borne in mind that “wounded” often implied the necessity of amputation of limbs and that death by gangrene was a serious possibility thereafter. As was normal when a captain lost his ship, Captain Jenkins was later court-martialled, though he was exonerated, despite what many considered poor leadership and tactical manoeuvring.

Both vessels were to have active careers thereafter. HMS Ambuscade was taken into French service as Embuscade – wooden ships were almost infinitely repairable if they had not exploded, burned or been sunk. She was however recaptured in 1803 by no less a prestigious ship than HMS Victory, and she resumed her old name. She had an active and successful career thereafter until she was broken up in 1810. Bayonnaise’s luck ran out in 1803, the same year in which Ambuscade/Embuscade’s turned for the better. Run down by HMS Ardent off Cape Finnisterre, her crew burned her rather than surrender.

French pride in the Bayonnaise/Ambuscade action was unbounded – probably because such victories were rare – and eminent artists of the time produced dramatic paintings of it. They convey much of the excitement and drama and some have been used to illustrate this article.

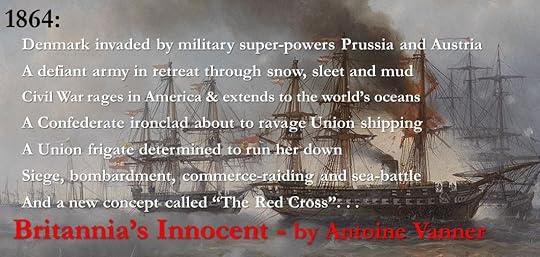

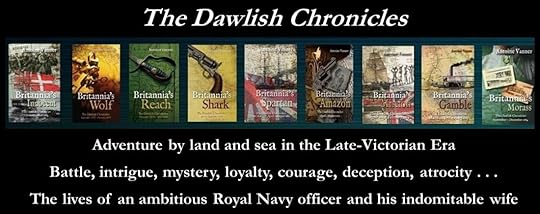

The new Dawlish Chronicles novel is publishedBritannia’s Guile 1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

But greater events are underway in Europe. The Russian and Ottoman Empires are drifting ever closer to a war that could draw in other great powers. And Britain cannot stand aside – a Russian victory would spell disaster for her strategic links to India.

The Royal Navy is preparing for a war that might never take place. Dozens of young officers, all as qualified as Dawlish, are hoping for their own commands. He’s just one of many . . . and he lacks the advantages of patronage or family influence. But only a handful of powerful men know how unexpectedly vulnerable Britain will be if war comes. Could this offer Dawlish his chance to advance?

Far from civilisation, dependent on a new and as yet unproven weapon, he’ll face a clever and ruthless enemy in unforeseeable and appalling circumstances.

Only stubborn resolution – and unlikely allies — can bring him through. But at what price?

Britannia’s Guile is set early in the Dawlish Chronicles series (directly ahead of Britannia’s Wolf) and tells how Dawlish met several people who will play major roles in his future career. And they may not all be as they seem . . .

For Kindle or Paperback ordering: US Click Here UK Click HereAustralia & New Zealand Click Here

Members of Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra chargeClick here, or on the banner below, to see details of all books in the Dawlish Chronicles series in chronological order. plus ordering links .fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Bayonnaise and HMS Ambuscade action, 1798 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

December 9, 2021

Indefatigable vs. Droits de l’Homme

HMS Indefatigable vs. Droits de l’Homme Desperate action in storm and darkness 1797

HMS Indefatigable vs. Droits de l’Homme Desperate action in storm and darkness 1797Besides their few major fleet actions, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars saw many vicious encounters between small numbers of French and British ships which have since provided the inspiration for much naval fiction. One of the most ferocious of these battles was fought in the darkness of a stormy winter night off the coast of Brittany in early 1797 and it established Sir Edward Pellew, later to be Lord Exmouth, then captain of HMS Indefatigable, as the foremost frigate captain of the era.

The battle off Brittany 13th January 1797: Painting by Leopold de Guen (1828-1895)

In December 1796, eager to exploit rebellious sentiment in Ireland against British rule, and urged on by Irish exiles, the French Revolutionary Government sent a huge naval and military expedition to open a new theatre of war in Britain’s own backyard. The choice of December may seem a strange one, due to the poor weather that could be expected, but the French relied on this to allow their ships to slip past the blockading Royal Navy squadrons.

The French force left their base at Brest, in Brittany, on December 16th 1796 – seventeen ships-of the-line, thirteen frigates, six corvettes, seven transports, and a storeship. They carried some 20,000 troops under the command of the renowned General Lazare Hoche (1768-97) who, but for his early death (possibly by poison), could have been a rival to Napoleon for supreme power in France. The overall commander was Admiral Morard de Galles, who had established his reputation as one of the great Admiral Suffren’s most successful captains.

Brest was under observation by the Royal Navy’s inshore squadron, under Captain Sir Edward Pellew (1757-1833), seen on the right, who was already on the way to proving himself one of the greatest commanders of the era. The squadron consisted of four frigates, Pellew himself in HMS Indefatigable, a 44-gun heavy frigate, as well as HMS Revolutionnaire (a French prize taken into British service), HMS Phoebe, and HMS Amazon. When Pellew saw the French emerge he sent off the Revolutionnaire to alert Admiral Sir John Colpoys, who with fifteen of the line would have normally been closer inshore, but who had been blown off station by the same strong easterly winds that facilitated the French departure.

Brest was under observation by the Royal Navy’s inshore squadron, under Captain Sir Edward Pellew (1757-1833), seen on the right, who was already on the way to proving himself one of the greatest commanders of the era. The squadron consisted of four frigates, Pellew himself in HMS Indefatigable, a 44-gun heavy frigate, as well as HMS Revolutionnaire (a French prize taken into British service), HMS Phoebe, and HMS Amazon. When Pellew saw the French emerge he sent off the Revolutionnaire to alert Admiral Sir John Colpoys, who with fifteen of the line would have normally been closer inshore, but who had been blown off station by the same strong easterly winds that facilitated the French departure.

The Revolution had deprived the French Navy of many of its most experienced officers and indiscipline was rampant. Insufficient attention had been paid to training and the presence of strong British forces offshore limited opportunities for acumulating ship-handling experience. The result was that, even in the absence of strong Royal Navy forces, de Galles’ fleet, badly handled in strong wind, lost cohesion on its first day at sea.

As darkness came on, Pellew edged down among the mob of French ships. When de Galles signalled with guns, rockets, and blue lights, Pellew did the same, with variations of his own, completely confusing the French captains. Amid the general disorder that followed, one of the French 74’s, the Seduisant, drove on to a rock and became a total wreck. From 1300 on board only some 600 were saved.

Despite this setback the French evaded Colpoys’ squadron and reached Bantry Bay, in South-West Ireland, in late December. Here storms and fog made landing impossible and the decision was taken to abandon the expedition and return to France. Had it landed, the course of Irish history might have been changed radically.

A contemporary British view of the failure of the Bantry Bay Expedition – Cartoon by Gillray

The French straggled home in ones and twos and threes, no longer a fleet. On January 13th, one of the French 74’s, the Droits de l’Homme, commanded by a Captain Raymond de Lacrosse, found herself alone off the coast of Brittany. Visibility was poor and Lacrosse decided to approach no nearer but to sail southward under easy sail, the wind on his starboard beam. In mid-afternoon two sails were spotted on the lee bow, between the Droits de l’Homme and the land. These proved to be Pellew’s HMS Indefatigable, in company with a 36-gun 18-pounder frigate, HMS Amazon, commanded by Captain Robert Reynolds (1745 – 1811). Pellew immediately signalled to HMS Amazon to give chase, and steered towards the enemy, sailing considerably faster than his smaller consort in the heavy sea.

On this winter day dusk fell about four-thirty and the wind, which had been fresh all day, blew a full gale. As darkness came on the Droits de l’Homme lost her fore and main topmasts in a violent squall. Fearing that there might be yet more British ships about, Lacrosse altered course to eastward, and ran straight before the gale, hoping to reach the channel leading to Brest. It was a dangerous decision, as he cannot have been certain about his exact position, and should he have mistaken his landfall, there would be no chance for a crippled ship on a lee shore in such conditions.

At five-thirty, HMS Indefatigable, in near darkness and under close-reefed topsails, surged across the Droits de l’Homme’s stern and raked her. The French ship had nearly a thousand troops on board and they peppered HMS Indefatigable with musket fire as she passed. Pellew’s manoeuvre brought the two vessels so close together that the ensign staff of the French ship fouled HMS Indefatigable’s mizzen rigging and British seamen dragged the tattered remains of the French tricolour on to their own quarterdeck. Lacrosse now tried to bring his vessel alongside, possibly with a view to boarding, difficult as the high seas running would make it, but Pellew managed to sheer away. The Droits de l’Homme’s bowsprit actually grazed HMS Indefatigable’s spanker boom, and she in turn suffered raking fire as she turned away.

HMS Indefatigable (on right) engages, mid-afternoon – HMS Amazon seen coming up on the horizon

For the next hour and more HMS Indefatigable engaged the French ship-of-the-line single-handedly. In her favour was the fact that in the heavy sea that was running Lacrosse hardly dared open his lower deck gun-ports, and thus lost use of his 36-pounders, his most formidable weapons. The Droits de l’Homme carried 18-pounders in her upper tier, while HMS Indefatigable had an unusually powerful armament for a frigate – 24-pounders on the gun-deck and 42-pounder carronades on the poop and forecastle. In spite of the sea, she fought her 24-pounders right through the action. The loss of his topmasts made it impossible for Lacrosse to steady his ship, and she rolled so furiously that her gunners and small-arms men found aiming difficult.

HMS Amazon arrived out of the darkness shortly before seven o’clock. She blasted a broadside into the Droits de l’Homme but swift action by Lacrosse avoided raking through the stern. Amazon’s manoeuvre had brought both British frigates on the same side of the French ship, masking each other’s fire, so at seven-thirty they both pulled ahead of the enemy. Pellew seems to have been particularly concerned to repair damage to his rigging.

The Droits de l’Homme also needed a respite badly – heavy casualties had been sustained and poor discipline and training had resulted in considerable confusion – but it proved a short one. An hour later Pellew’s two frigates resumed their attack, stationing themselves one on either side of the enemy, and manoeuvring so as to rake her alternately. The Droits de l’Homme attempted to yaw first one way and then the other in order to return their fire, but without much success.

The height of the action, night of 13/14th January – Le Droits de l’Homme sandwiched between Pellew’s two frigates

It is hard to visualise just how ghastly the scene must have been – the high waves, the screaming wind, the crashing guns, the cries of the injured and dying, the enveloping darkness and choking clouds of smoke illuminated by the deafening gunfire. This continued for over two hours.

At ten-thirty the Droits de l’Homme’s mizzen-mast went overboard, and the frigates now positioned themselves off her port and starboard quarter, firing grapeshot so as to hinder any attempt at rigging a jury-mast. Both British ships were rolling so violently that their guns’ breechings – their restraining ropes – were parting and iron ring-bolts in the deck, to which they were fastened were being torn free. The brutal pounding march continued through the night, so heavy that by midnight the French vessel’s store of roundshot was exhausted. And still the British ships blasted without let-up.

At four in the morning, long before daylight, a look-out on HMS Indefatigable reported land directly ahead. Pellew immediately signalled the danger to the Amazon, and hauled his wind southwards while the Amazon bore away to the north. The Droits de l’Homme, possibly oblivious to the danger, held straight on.

All three ships were now in extreme peril. Attack had proved the best form of defence for HMS Indefatigable – her crew’s superior gunnery skills had seen to that. Almost miraculously, no one had been killed and fewer than twenty were wounded, half of them only slightly. She had however suffered severe damage aloft – the French were known for aiming for masts, spars and rigging. The most significant damage was that the shrouds of the main top-mast had been severed. Should this mast fall then HMS Indefatigable could not hope to beat off a lee shore in strong wind under her fore and mizzen topsails only. The hero of the hour proved to be the seaman who was “captain of the maintop”. He went aloft and somehow reached the lurching topmast-head. The end of a hawser was passed up to him and he managed to secure it around the head of the mast. The other end was made fast below and the mast was stabilised. This was perhaps the most heroic exploit of the battle for it was accomplished in darkness, and in a gale, with the swaying topmast threatening to go over at every moment, taking the seaman with it.

All three ships fighting for survival in Audierne Bay

HMS Indefatigablestood to the south, close-hauled. Then, in the light of dawn, breakers were seen ahead, astern and to starboard. Blindly running before the gale during the night action, all three ships had been entrapped in Brittany’s Audierne Bay.

Pellew wore ship – he “jibed”, a difficult manoeuvre for a square-rigged ship at any time and a daunting one for a damaged one and in the teeth of a gale. Superb professionalism by officers and men alike proved it successful and through the morning Pellew worked towards the safety of the open sea.

HMS Amazon was less lucky. She had taken higher casualties – three killed and fifteen badly wounded – and her masts and spars were badly damaged. Her mizzen topmast, gaff, spanker -boom, and main-topsail yard were gone, and her sails were in shreds. She ran onshore and broke up, but not before all but six of her disciplined crew all came safely ashore on rafts. They were immediately surrounded by French troops and marched off into captivity. It is pleasing to learn that they were well treated. Amazon’s Captain Reynolds was later honourably acquitted by a court-martial for the loss of his ship, and his two lieutenants were promoted.

The destruction of Le Droits de l’Homme – Indefatigable seen escaping seawards on the left

A worse fate awaited the Droits de l’Homme. She too ran on to rocks but discipline seems to have broken down and officers proved incapable of regaining control. For the next four days, the survivors clung, cold and starving, to the remains of the wreck until a French brig managed to reach them and get them ashore. Among the survivors was General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert (1767 –1823), who the following year was successful in landing a small French army in Ireland. Humbert’s life was a fascinating – and unlikely – one and worthy of a separate blog in the future.

In the action, the Droits de l’Homme lost over 100 killed, and 150 wounded, from the gunfire of Pellew’s frigates. A British naval officer who was a prisoner on board, and survived, though barely, claimed that after she had run on the rocks about 1000 men drowned or died of starvation and exposure. Just over 400 were saved.

Pellew’s reputation and fame, already great, reached new levels after this action which was an unusual – and perhaps unique – instance of a ship-of-the-line being destroyed by frigates. The circumstances were however exceptional and few captains other than Pellew would have dared turn storm and darkness into weapons against the larger ship.

Few more desperate actions were fought in the Age of Fighting Sail.

The new Dawlish Chronicles novel is publishedBritannia’s Guile 1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

But greater events are underway in Europe. The Russian and Ottoman Empires are drifting ever closer to a war that could draw in other great powers. And Britain cannot stand aside – a Russian victory would spell disaster for her strategic links to India.

The Royal Navy is preparing for a war that might never take place. Dozens of young officers, all as qualified as Dawlish, are hoping for their own commands. He’s just one of many . . . and he lacks the advantages of patronage or family influence. But only a handful of powerful men know how unexpectedly vulnerable Britain will be if war comes. Could this offer Dawlish his chance to advance?

Far from civilisation, dependent on a new and as yet unproven weapon, he’ll face a clever and ruthless enemy in unforeseeable and appalling circumstances.

Only stubborn resolution – and unlikely allies — can bring him through. But at what price?

Britannia’s Guile is set early in the Dawlish Chronicles series (directly ahead of Britannia’s Wolf) and tells how Dawlish met several people who will play major roles in his future career. And they may not all be as they seem . . .

For Kindle or Paperback ordering: US Click Here UK Click HereAustralia & New Zealand Click Here

Members of Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra chargeClick here, or on the banner below, to see details of all books in the Dawlish Chronicles series in chronological order. plus ordering links .fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post Indefatigable vs. Droits de l’Homme appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

December 4, 2021

Crimean War’s North Pacific Theatre 1854

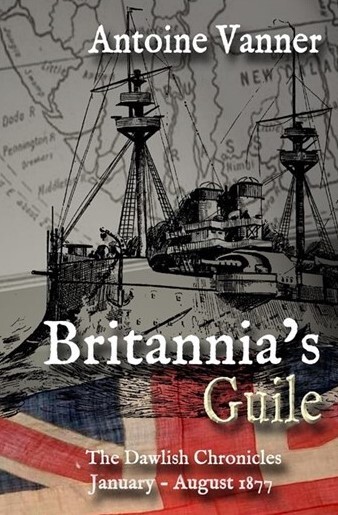

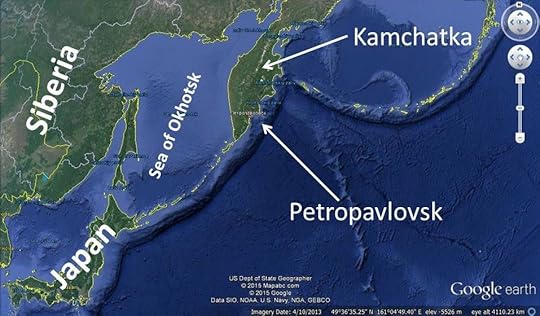

The Crimean War’s North Pacific Theatre:Petropavlovsk, August 1854

The Crimean War’s North Pacific Theatre:Petropavlovsk, August 1854The most common image of the Crimean War (1854 – 56) is of Britain’s Light Brigade charging to death and glory against Russian guns at Balaclava. Almost equally well known are the epics of the ”Thin Red Line” and of the Storming of the Redan, both in the Crimea itself. The more nautically- minded may think of the enormous and costly expedition to the Baltic that earned such scanty returns. Few have however heard of the most remote operation of the war, the Anglo-French assault on Petropavlovsk, Russia’s Northern Pacific port on the Kamchatka peninsula.

Even for Russians the word “Kamchatka” signified the back of beyond, difficult to the point of near impossibility to reach by land from European Russia. The Trans-Siberian railway had not yet been thought of and would not to be completed for another five decades and the only realistic way of supplying the settlements there was by sea. Kamchatka is a vast peninsula – almost 100,000 square miles – and contains some 160 volcanoes, 29 of them active today – and it is all but cut off from the rest of Siberia by the Sea of Okhotsk. In 1854 Russian presence there was scarcely a century old and the town of Petropavlovsk, founded by the navigator Vitus Bering (of “Strait” fame) in 1740, was important not only as an ice-free port but as a transit point for contact with Russian Alaska. Russia’s interest in Alaska was however never more than lukewarm and its potential was never recognised. It was to be sold to the United States at a knock-down price some thirteen years later.

Petropavlovsk is situated on what a Victorian writer described as “one of the noblest bays in the whole world—glorious Avatcha Bay”. By 1854 the city possessed an almost landlocked harbour, with a sand-spit protecting it from all fear of gales or sudden squalls. The shelter it offered, and its freedom from winter ice, made it an ideal maritime base, and in more recent times has been used as such by the Soviet and Russian Federation Pacific Fleets.

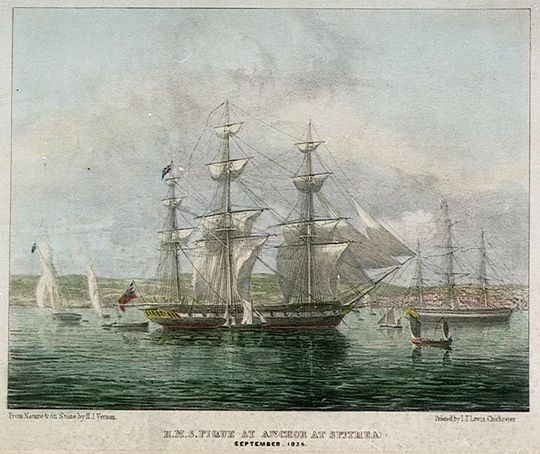

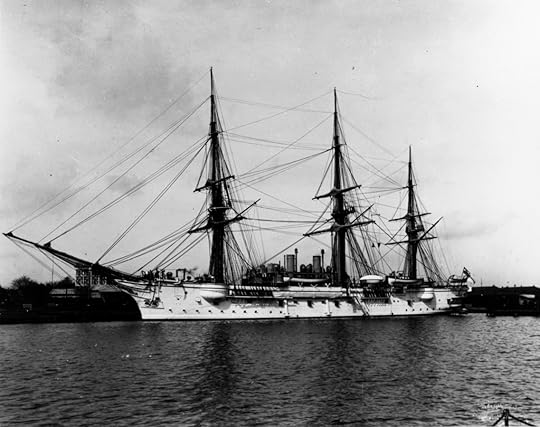

Petropavlovsk in 1856 – at the war’s end. Note the mole protecting the harbour

When Britain, France, Turkey and Piedmont went to war with Russia in 1854 the main theatres of war were to be the Crimea and the Baltic, both offering access by sea. Destruction of the Crimean naval base at Sevastopol and of the Russian fortifications in the Aland Islands, were seen as strategically significant and desirable. It is however impossible to understand how an expedition against Petropavlovsk could ever have been imagined to have any significant impact on the war. Even if held, the occupying force had nowhere else to go and the only Russians inconvenienced would be the two or three thousand engaged in trading in Alaska. Despite this, it was decided that a not-inconsiderable Anglo-French force should be sent against Petropavlovsk. This consisted of six vessels, the Royal Navy’s HMS President (Frigate, 38 guns), HMS Virago (paddle sloop, 6 guns), and HMS Pique (frigate, 36 guns), plus the French La Fort(frigate, 60 guns), Eurydice (corvette, 32-guns), and Obligado (sloop, 32 guns). As only Virago was steam-driven the force was in effect little different from one that might have set to sea in the Napoleonic Wars four decades only. The British commander, the 64-year old Rear-Admiral David Price was himself a veteran of that latter period, having been just promoted after 39 years as a post-captain. The French force was under a Rear-Admiral Auguste Febvrier-Despointes and, as always in allied operations, the potential for miscommunication and confusion was significant. On paper, the Allied force carried some 200 guns, though as almost entirely consisting of broadside ships only half this number could be brought to bear at any one time.

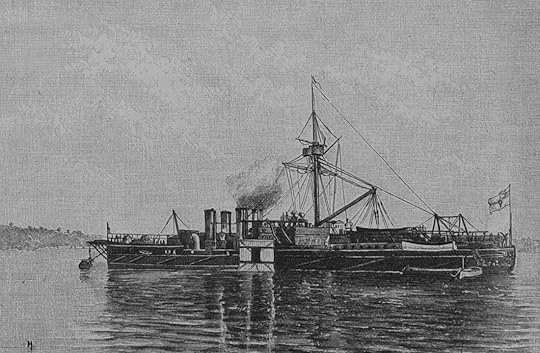

HMS Virago – the only steamship in the Allied force (with acknowledgement to the Australian War Memorial)

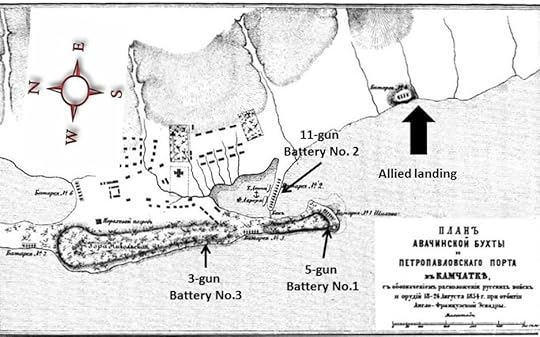

The Anglo-French force entered Avatcha Bay on August 28th 1854 (by the Western calendar) and the less wind-dependent Virago was sent to reconnoitre. The town – little more than a village – was protected from the outer bay by a long narrow peninsula on the west, and a sandbank on the east. Vessels passing between these entered the inner harbour and the passage could be closed by a chain. Protective batteries had been located as shown by superimpositions on the contemporary Russian map above – a 5 gun battery at the tip of the peninsula (Battery No.1), an 11 gun battery on the sandbank opposite (Battery No.2) and a 3 gun battery further back along the peninsula (Battery No.3). The total Russian force present amounted to 920 men, seamen as well as soldiers, plus two ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet (indeed almost the entire fleet!), the 44-gun frigate Aurora and the transport Dvina. These were moored inside of the sandpit and effectively protected by Battery No.2, which they supplemented with their own landed guns.

Contemporary Russian Map, with Vanner’s annotations to identify batteries etc.

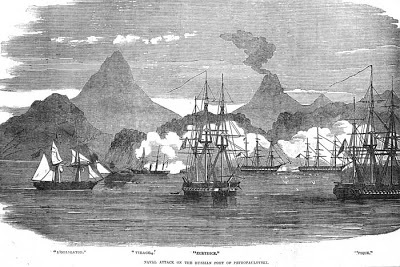

Virago’s reconnaissance complete, the allied force advanced to bombard the town on August 31st. Proceedings were opened by Rear-Admiral Price going below and shooting himself – whether deliberately or by accident, is unknown – leaving British command to devolve to Captain Nicholson of HMS Pique. The bombardment was suspended but on September 4th the force returned, Virago in the lead, followed by La Fort, President and Pique which were to concentrate fire on Battery No.1 while Eurydice and Obligado took on Battery No.3.

HMS Pique – one of the last sailing frigates, obsolescent when built in 1836

The bombardment proved successful and both batteries were silenced (an unusual occurrence when ships were pitted against shore batteries – indeed Nelson himself had warned that “A ship’s a fool to fight a fort”). Engaging Battery No2 on the sand spit closing off the inner harbour was however a more difficult proposition since insufficient room was available to being all the Allied ships’ guns to bear on it. Taking the town therefore meant landing men. It was however shut in by high hills on almost all sides and the only vulnerable point was in the south, outside the harbour, where a small valley opened out on land bordering the bay (see old Russian map above).

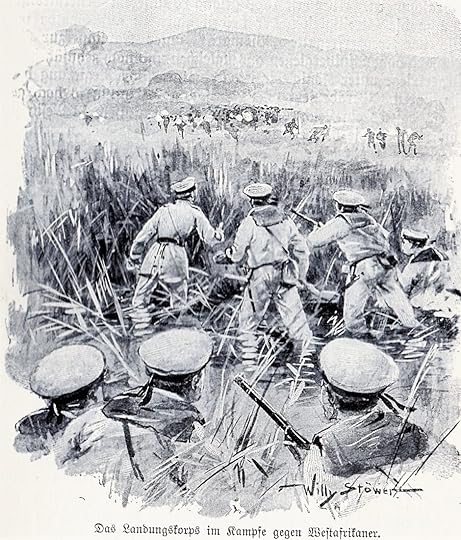

Petropavlovsk under bombardment – a contemporary impression

A landing party of some 680 British and French seamen and marines was hurriedly assembled and sent on shore in boats. The landing was unopposed and the Anglo-French force thrust inland in a straggling, ill-coordinated manner. The ground ahead, rising towards a ridge, was littered with scattered bushes and trees, behind which Cossack sharpshooters had been positioned. They opened a withering fire and picked off nearly every Allied officer. The men, not seeing their enemy and having lost their leaders, fell back in panic-stricken disorder. Many had lost their orientation in the brush and a series of small, vicious combats followed, some of the landed force being most likely shot accidentally by their own side. A number fled up a hill at the rear of the town and were hunted down mercilessly by the Cossacks while others died by falling over the steep cliff on one side of the hill. The guns of La Fort, Virago and Obligado covered the main retreat to the boats, but it was clearly a major defeat. The butcher’s bill was 107 British and 101 French dead or wounded out of the 680 landed. The Russians lost half these numbers and held the field. Allied defeat was total.

There was nothing to be done by the Allies to withdraw, smarting. The winter made the prospect of further action unattractive but a return in force was soon being planned for the following year. Unknown to allies the Russians had decided – wisely – that Petropavlovsk was of little value to themselves, and a potential liability for the Allies, should they take it. Accordingly, in early 1855, the Russian garrison was evacuated.

The Allies were meanwhile assembling a more massive force, with ships assigned to it from the China station. The new commander, Rear Admiral Bruce, organised supplies in Hawaii and a huge supply depot and hospital was organised at Esquimalt, near Vancouver to provide further support. On May 30th 1855 the combined Anglo-French flotilla arrived back at Petropavlovsk in thick fog and took up positions in anticipation of an attack. When the fog cleared two days later reconnaissance revealed the town as deserted. Bruce’s force occupied it without a shot being fired. It was to hold the city until the war came to an end in 1856.

Russian cannon of Battery No.3 looking out over the Bay of Avatcha today

The repulse of the Allies at Petropavlovsk was the only Russian success on any front in the Crimean War and as such is remembered better there than in the West. At a tactical level the operation had more in common with the Napoleonic period – sailing vessels, broadside muzzle-loading artillery, improvised landings – than with the era then dawning. The ironclad would arrive within a decade and, fast in its wake, breech-loaders, torpedoes, efficient steam power and ever-improving armour. At a strategic level the operation, whether a tactical success or failure, could only represent a dead-end squandering of lives and resources.

For Britain and France Petropavlovsk was an embarrassment. And that is, perhaps, why we have heard so little of it since.

The new Dawlish Chronicles novel is publishedBritannia’s GuileAvailable for preorder on Kindle at a reduced price to December 9th 2021 (Links at end of this note). 1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

1877: Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is hungry for promotion. He’s chosen service on the Royal Navy’s hazardous Anti-Slavery patrol off East Africa for the opportunities it brings to make his name. But a shipment of slaves has slipped through his fingers and now his reputation, and his chance of promotion, are at risk. He’ll stop at nothing to save them, even if the means are illegal . . .

But greater events are underway in Europe. The Russian and Ottoman Empires are drifting ever closer to a war that could draw in other great powers. And Britain cannot stand aside – a Russian victory would spell disaster for her strategic links to India.

The Royal Navy is preparing for a war that might never take place. Dozens of young officers, all as qualified as Dawlish, are hoping for their own commands. He’s just one of many . . . and he lacks the advantages of patronage or family influence. But only a handful of powerful men know how unexpectedly vulnerable Britain will be if war comes. Could this offer Dawlish his chance to advance?

Far from civilisation, dependent on a new and as yet unproven weapon, he’ll face a clever and ruthless enemy in unforeseeable and appalling circumstances.

Only stubborn resolution – and unlikely allies — can bring him through. But at what price?

Britannia’s Guile is set early in the Dawlish Chronicles series (directly ahead of Britannia’s Wolf) and tells how Dawlish met several people who will play major roles in his future career. And they may not all be as they seem . . .

For Kindle Pre-Ordering:

US Click Here ($2.99 to Dec 9th, $3.99 thereafter)

UK Click Here (£2.99 to Dec 9th, £3.99 thereafter)

Australia & New Zealand Click Here ($3.99 to Dec 9th, 43.99 thereafter)

Members of Kindle Unlimited can read at no extra charge

US Click Here ($12.49 )

UK Click Here (£9.49 )

Australia & New Zealand Click Here ($23.88)

The post Crimean War’s North Pacific Theatre 1854 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 26, 2021

Naval Artist Thomas Luny (1759–1837)

Naval Artists of the 18th Century – Part 3Thomas Luny (1759–1837)

Naval Artists of the 18th Century – Part 3Thomas Luny (1759–1837)In this article I want to tell of a hero, Thomas Luny, who is known as a great naval painter – but other details of whose life are less familiar. Two sorts of courage move me. The first is the sort of bravery that is called upon for a finite period, for minutes, hours, days or even on occasion months, and which demands a disregard for personal safety and a willingness to risk life and limb of the sake of others. The second is “fortitude”, the determination to endure suffering, privation or personal misfortune over an indefinite period, and still not be defeated. The latter is expressed, unforgettably, by the crippled poet William Ernest Henley (1849–1903):

These words come to mind – for reasons that will emerge later in this article – when looking at the career of the marine artist, Thomas Luny (1759–1837). His work is familiar to many of us, even if we don’t know his name, if we have seen illustration of the Age of Fighting Sail. At a time before photography Luny was one of the artists who had defined our perception of how that age looked and felt. (If you have missed earlier blogs in this occasional series click here and here)

The Bombardment of Algiers, August 1816, by Thomas Luny

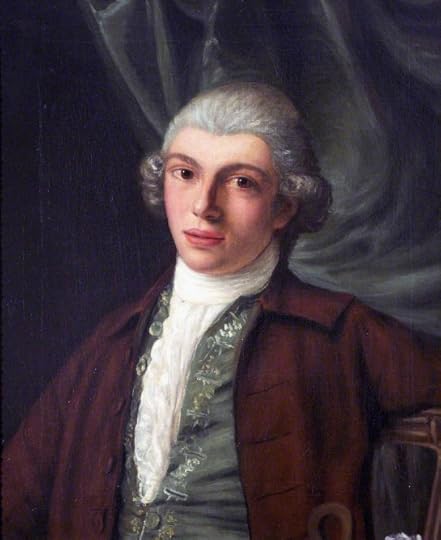

Self-portrait in youth

Luny was born in Cornwall – most appropriately in the famed “Year of Victories” when British forces were triumphant on land and sea In Europe and North America. He came to London at the age of eleven and was apprenticed to the marine painter Francis Holman (1729–1784), who was himself son of a master mariner. This apprenticeship proved significant in determining the course of Luny’s career since Holman’s younger brother, Captain John Holman (1733–1816), maintained the family shipping business. The relationship between the brothers appears to have been a close one. Francis would therefore have been in close contact with the maritime world and this showed in the wealth of detail and accuracy in his later work. Talented as Holman was however, it is partly because of his mentorship of the more illustrious Luny that he is now most remembered.

“A small shipyard on the Thames” by Francis Holman, Luny’s mentor

(National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PD-ART-LIFE-70

By 1780 Thomas Luny had shown sufficient talent that he was exhibiting marine paintings in the Royal Academy, and indeed he continued to do so up to 1802. From 1783 Luny lived in London’s Leadenhall Street, and here became acquainted with a dealer and framer of paintings called Merle who subsequently promoted Luny’s work very successfully.

The 18-year old Luny hits his stride: “Shipping off Dover” – 1777

Thomas Luny’s home address in Leadenhall Street was also significant in that it was where the British East India Company had its headquarters. It was from “John Company” that Luny was to receive many commissions for paintings and portraits. This relationship had non-monetary benefits also for, on occasions, Thomas Luny seems to have been invited as a guest on Company ships on special occasions and voyages. This probably accounts for the great detail and realistic look of many of his sketches of locations such as Naples, Gibraltar, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Between 1793 and 1800 Thomas Luny appears to have gone to sea with a purser’s warrant and served with Captain, afterwards Admiral, George Tobin (1768–1838).

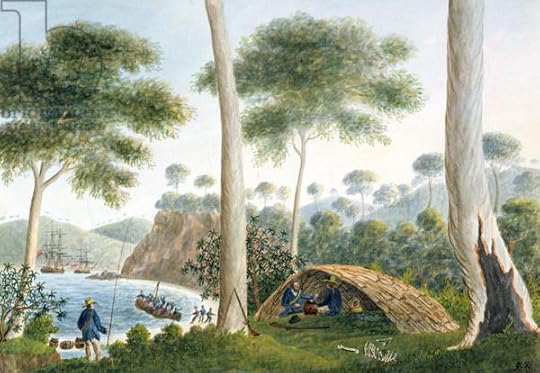

George Tobin: Aboriginal hut on Bruny Island, Tasmania, 1792 (Mitchell Library)

One suspects that under Captain Tobin the purser’s duties may have been nominal – a legal fiction for getting Luny to sea. One has the distinct impression that the relationship between Luny and Tobin was very similar to the fictional one between Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin, two men of very different characters and aptitudes who nevertheless valued their friendship dearly. One would like to think so. Tobin was himself an artist and the watercolours he made when he sailed with Captain Bligh to Van Diemen’s Land in 1790-1792 are in the Mitchell Library, Sydney (see example above). In this, once again, one sees the Aubrey-Maturin similarity, since in both cases the dissimilar personalities have one shared passion and talent, in the once case for music and in the other for art.

Engraving of Luny’s “The Glorious First of June”

Whether Thomas Luny was present at the battle of the ” Glorious First of June” in 1794 is uncertain, but he painted, among many other marine subjects, several of the incidents of this battle and of the subsequent bringing home of the prizes. It is equally uncertain whether he was on hand for the Battle of the Nile 1798, which he also illustrated spectacularly.

The Battle of the Nile, August 1st 1798, at 10 p.m.

Painted by Luny in 1835, over three decades after he was incapacitated

Up to 1800 Luny’s life had not only been dramatic and adventurous, but also triumphant in professional terms. It was now however that great misfortune fell upon him when he was attacked by rheumatoid of arthritis. It deprived him initially of the use of his feet, and later, cruelly for an artist, it closed his hands so firmly that he could not move his fingers. In this state he moved in 1807 to Teignmouth in Devon, apparently to be his friend Captain Tobin, who had also retired there.

Thomas Luny: “Boarding the ferry at Teignmouth” – painted 1821

(With acknowledgements to Wikigallery)

It was now that Luny’s fortitude and greatness of spirit asserted itself. Despite all his disabilities he continued to paint, receiving numerous commissions from ex-mariners and others, with the same success as before. He was to continue working up to 1835, chair-bound and only able to clutch his brush between hands which could not hold it in his fingers. For delicate manipulation he is said to have held the brush in his mouth. This had no obvious impact on the quality or pace of his artistic work. In fact, of his lifetime oeuvre of over 3,000 works, over 2,200 were produced between his disablement in 1807 and his death. His style is unmistakable.

Thomas Luny: “A frigate of the Royal Navy leaving Cork Harbour 1830”

Specimens of Thomas Luny’s work are exhibited at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, London, in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, and at The Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia. If you read this, and if you’re lucky enough to see any of Luny’s work, pay a silent tribute to the memory not only of a great artist, but of a great spirit.

Naval fiction in the Age of Fighting SteamBritannia’s Innocent is the first chronologically of the Dawlish Chronicles SeriesClick here, or on the image below, to read the opening chaptersFor more details regarding purchase in paperback or Kindle format, click below Note that Kindle Unlimited and Kindle Prime subscribers can read at no extra chargeFor amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to nine volumes, and with the tenth due for publication in December 2021. Click below for series overview.Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Naval Artist Thomas Luny (1759–1837) appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

November 19, 2021

Battle of Caulk’s Field 1814

Caulk’s Field: the Death of Captain Sir Peter Parker, 1814

Caulk’s Field: the Death of Captain Sir Peter Parker, 1814The British attack on Baltimore in mid-September 1814, and the heroic defence of Fort McHenry, is one of the most widely remembered incidents of the War of 1812, since it was to inspire the writing of the American national anthem. It was however preceded by a British amphibious attack on the eastern shore of Upper Chesapeake Bay, directly across from the city, on August 31st. A force of seamen and marines were landed from a British frigate and were soundly beaten in an engagement known as the Battle of Caulk’s Field. At this remove the landing appears to be an unwise one that could have achieved little or nothing as regards the larger operation against the city.

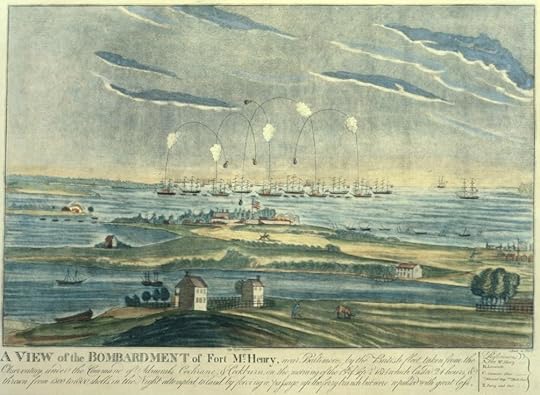

The attack on Fort McHenry – the inspiration for “The Star-Spangled Banner”

The attack on Fort McHenry – the inspiration for “The Star-Spangled Banner”

The Caulk’s Field battle did however result in the death of a young Royal Navy captain, Sir Peter Parker (1785-1814), and the manner of his passing was to be widely admired. The account that follows focusses on this, rather than on the battle. It draws heavily on Edward Giffard’s “Deeds of Naval Daring” (1852)and it casts light not only on the warmth of relations between enlisted seaman and admired officers, but on the discrepancies that arise between accounts from different sources, in this case British and American.

Parker – young, handsome and brave

Sir Peter Parker was the grandson of Vice Admiral John Byron (1713-1786), known as “Foul Weather Jack” and as such first cousin of Lord Byron. the poet. He had entered the navy in 1798 and by 1805 he was in command of the brig HMS Weazel which was the first British vessel to sight the enemy fleet exiting Cádiz prior to the Battle of Trafalgar. By 1810 he was not only a captain, but had been given command, at the age of 25, of the new frigate HMS Menalaus. His first duty was to provide assistance in suppression of a mutiny in the frigate HMS Africaine, after which he gave meritorious service in the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean. In 1813, with the “War of 1812” between Britain and the United States in full swing, the Menelaus was transferred to duties off the American eastern seaboard.

In August 1814 Parker was in the Upper Chesapeake with Menelaus and preparations were in hand for the British attack that would come a fortnight later. According to Giffard, Parker “received information from an intelligent black man that a body of militia were encamped behind a wood within sight of the ship.” Parker therefore decided on making a surprise landing, staging a night attack and storming the militia camp. He would lead the raid personally. Just before midnight on 30th August 1814 he landed a force of seamen and marines, some 140 in total and divided them into two groups headed by two of his Lieutenants, Crease and Pearce. He seems to have been well aware of just how dangerous – perhaps even foolhardy – the undertaking was and he wrote a short letter to his wife, as follows:

Menelaus, August 30, 1814

I am just going on desperate service, and entirely depend upon valour and example for its successful issue. If anything befalls me, I have made a sort of will. My country will be good to you and our adored children. God Almighty bless and protect you all!

Adieu, most beloved Marianne, Adieu!

HMS Pomone: a typical frigate of the time, which Menelaus would have resembled

(Painting by the great Thomas Luny)

Menelaus’s landing party captured several guards without apparently raising any great alarm and advanced in silence towards the militia camp. On arrival there they found that the enemy had moved. In strange country, and in darkness, discretion might have called for a return to the ship but Parker decided to press on. What followed was to be known as Battle of Caulk’s Field, near Fairlee. The naval force advanced some four to five miles only to find itself confronted by force of 500 militia, a troop of cavalry and five artillery pieces drawn up in line on a plain surrounded by woods. Faced with such superiority, Parker decided that his only hope lay in an immediate attack. “By a smart fire, and instant charge, the enemy was driven from his position, completely routed, and compelled to a rapid retreat behind his artillery, where he again made a stand; one of his guns was captured, but again abandoned. The attack was instantly renewed with the same desperate gallantry.”

It was at this point, as later reported in the London Gazette, that “while animating his men in the most heroic manner, that Sir Peter Parker received his mortal wound, which obliged him to quit the field, and he expired in a few minutes.”

Giffard stated that “The ball by which Parker fell entered his right thigh, and cut the main artery. On receiving his mortal wound he smiled, and said, “They have hit me, Pearce, at last; but it is nothing. Push on, my brave fellows, and follow me!” Cheering his men with undaunted heroism of spirit, that even his dying accents may be said to have been strains of triumph. The latter as enthusiastically returned his cheer. He advanced at their head a few paces further, when, staggering under the rapid flow of blood from his wound, he grew weak, fell into the arms of his Second Lieutenant, Mr. Pearce, and, faintly desiring him to sound the bugle; to collect the men, and leave him on the field, he finally surrendered, without a sigh or a pang, his brave spirit to the mercy of Heaven.”

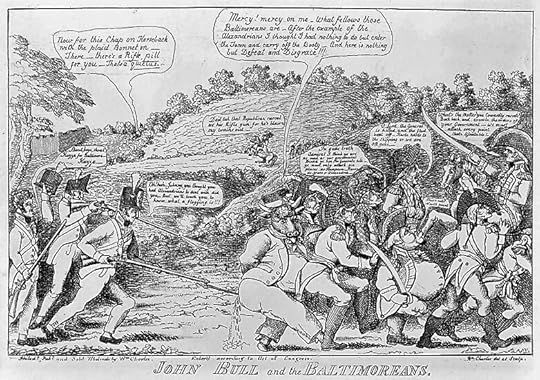

This cartoon conveys something of the American urge to resist the British. Note that John Bull is shown as a real bull!

A newspaper, the Boston Independent Chronicle, gave a different account on September 12, 1814 of Parker’s death. It estimated Parker’s force at between 200 and 300 – clearly too much to be landed from a single frigate. It attributed Parker’s wound to buckshot that hit him on the head as well as in the leg. (A son of a militiaman participant claimed later that his father had struck Parker down with by a ”blunder-buss loaded to the muzzle with all the hardware, bolts, nuts, nails, etc”). The newspaper reported five British dead, besides Parker, as well as five wounded, two of whom were to die. There appears to have been no American deaths and only three wounded.

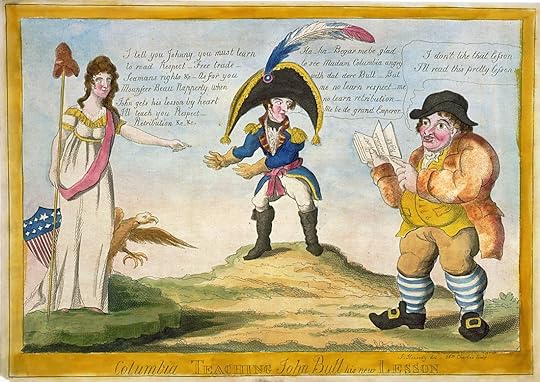

An American view of Britain during the War of 1812: Virtuous Columbia (l) admonishes t he coarse John Bull (r) while Napoleon, in the middle, enjoys the spectacle

Retreat was now the only option for the Menelaus landing party. It was now that the Parker’s crew was to demonstrate the respect and affection that inspirational leaders so often earned from the lower deck. Several of “his men collected around his body, and swore never to deliver it up to the enemy but with their lives.” Lieutenant Pearce had them carry the body on their shoulders ”who, relieving each other by turns, thus bore off to the shore (a distance of five miles) the body of their fallen and beloved commander. One of these, William Porrell, seaman, evinced on this occasion a personal bravery and attachment to his Captain that would have done credit to any mind. This man was near Sir Peter when he received the fatal wound, and immediately ran to his assistance, and supported him in his arms until further help was procured. The men who bore him off were changed occasionally, but Porrell refused to quit the body a moment, and, unrelieved, sustained his portion of the weight to the shore. When it was suggested by some present that the enemy might rally, and cut off their retreat, he exclaimed, ‘No d —d Yankee shall lay a hand on the body of my Captain while I have life or strength to defend it.’”

[image error]

“The Press Gang” by Luke Clennell (1781 – 1840) – an institution often inaccurately understood. Regardless of how recruited, seamen’s loyalty to admired officers was always high.

Porrell was not the only seaman to display remarkable resolution at Caulk’s Field. A twenty-four year old, James Perring, had been seriously wounded early in the action. In considerable pain he urged his companions to leave him and advance, swearing that “he would never become the prisoner of a Yankee. He subsequently crawled to a tree, against which, in great agony, he seated himself, with his cutlass in one hand and his pistol in the other.” He was found by the Americans after dawn when “finding the British had retreated, (they) returned to the field of battle for the humane purpose of collecting the wounded.” Perring was clearly dying and they summoned him to surrender. He answered that no American should ever take him alive. They assured him they only wanted to carry him off to the hospital. He persevered in refusing to receive succour from He was told, if he refused giving up they must fire on him. Collecting his strength, he exclaimed “Fire away, be d-d! No Yankee shall ever take me alive; you will only shorten an hour’s misery!” The Americans respected the heroism of this brave young man, and left him unmolested to die on the field.”

Parker’s body was sent home and was subsequently interred at the family vault at St Margaret’s, Westminster (the separate church adjoining Westminster Abbey), and the eulogy was delivered by his first cousin, Lord Byron. One wonders what would not subsequently have lain in the future for this dashing young frigate captain who was struck down at Caulk’s Field at the age of twenty-nine.

Reduced Kindle-Price offer: Britannia’s Gamble, November 19th to 22nd, 2021

Click on image to learn more

Like all the Dawlish Chronicles novels, Britannia’s Gamble can be read as a “stand alone”. It’s especially dear to me since the genesis of the plot goes back to my first reading about General Charles Gordon, the quintessential Victorian hero, when I was a boy.

Recent events in Kabul have reminded me of the plight that Gordon found himself in Khartoum in 1884-85. A fanatical Islamist revolt had swept across the vast wastes of the Sudan and was establishing a rule of persecution and terror. Only the city of Khartoum held out, the defence of its population masterminded by Gordon. Though his position was weakening by the day and a relief force might never reach him, he remained “the Good Shepherd who would not desert his flock.” It was an eric defence and it is at the heart of Britannia’s Gamble, which tells of Captain Nicholas Dawlish’s role in the rescue attempt, one not widely known about before . . .

I’m making the Kindle edition of Britannia’s Gamble available at half- price from Friday 19th November to Monday 22nd November inclusive.

On Amazon.com – Click: https://amzn.to/3FobyoL

Kindle: $1.99 (Usual Price $3.99)

On Amazon.co.uk – Click: https://amzn.to/3wUBt4m

Kindle: £1.99 (Usual Price £3.49)

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Battle of Caulk’s Field 1814 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 29, 2021

6ths at bay – HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford, 1760

HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford –Outgunned but Defiant, 1760

HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford –Outgunned but Defiant, 1760The term “post ship” was applied in the Royal Navy to Sixth-Rate vessels, and referred to the fact that they were the smallest ships that could be commanded by a post-captain. They were in effect miniature frigates, ship-rigged, some hundred feet long and around 500 tons armed with 20 to 26 long guns, typically nine pounders. They tended to be slow and for this reason were often used as convoy escorts.

A Sixth-Rate on the Stocks by John Cleveley the Elder (1712 – 1777)

A Sixth-Rate on the Stocks by John Cleveley the Elder (1712 – 1777)

Given competent and determined commanders, Sixth-Rates could however give a very good account of themselves. One of the most notable instances of this occurred during the Seven Years War, when two such vessels, HMS Bideford and HMS Flamborough, each of 20 guns, fought a spectacular action against two larger and more powerful French frigates.

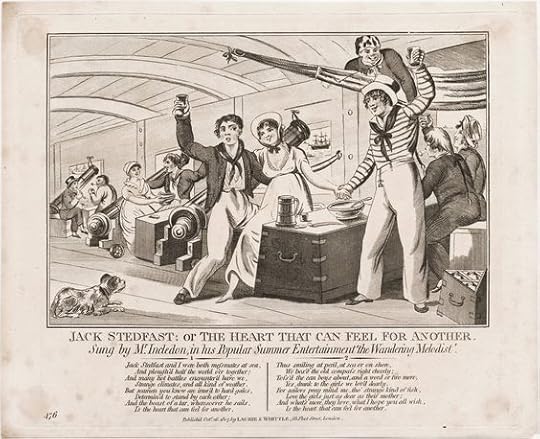

The spirit of “British Tar” was, no less than the professionalism of his officers, the foundation of the Royal Navy’s dominance in the Age of Fighting Sail. He was widely admired and often the subject of the pop-songs of the time, as shown here.

In April 1760 HMS Flamborough, commanded by a Captain Archibald Kennedy, and HMS Bideford, commanded by a Captain Skinner, were cruising off the Portuguese coast, close to the mouth of the Tagus. A valuable British convoy, escorted by a single sloop, was in the general area, but apparently out of sight. In the course of the day what appeared to be possibly four enemy ships were seen running before the wind. The two British ships were well to leeward and despite this, and the disparity in numbers, headed for the strangers.

HMS Brune, a frigate captured from the French in 1761. The French frigates engaged by HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford would have resembled this vessel. (Painting by John Cleveley the Elder, 1712 — 1777)

Captain Kennedy’s HMS Flamborough was the better sailer of the two British ships and by mid-afternoon got within distant gunshot range, opening fire on the closest ship – now clearly French. Rather than immediately engaging ship-to-ship, the French vessel signalled for two of her consorts to sail on and the third to join her in an attack on HMS Flamborough. Followed by the French – the frigates la Malicieuse (36 guns) and l’Omphale (32 guns) – Captain Kennedy retreated to join HMS Bideford. They met at around six o’clock. Despite the firepower advantage being in their favour, the French vessels now attempted to avoid action and ran.

As so often when reading accounts of combat in the Age of Fighting Sail, one is impressed by the aggressive self-confidence of Royal Navy officers. So it was in this case. The more powerful ships were in flight, the weaker in pursuit, as HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford chased the retreating French. HMS Flamborough, first came up with the sternmost French frigate, delivered a single broadside and pressed on, leaving her to be dealt with by Bideford. At half-past six o’clock, in twilight, HMS Flamborough came up with the leading French vessel, drew as close as possible without being able to board, or be boarded, and began a cannonade.

This slogging match continued until nine o’clock, by which time darkness had fallen. It’s hard to imagine what this must have sounded and felt like. Even a portrayal of a ship-to-ship action as realistic as that in the Master and Commander movie lasts only minutes on screen. HMS Flamborough and her opponent were at it for two and a half hours. By the time firing ceased – temporarily as it proved – the Flamborough’s masts, sails and running rigging were so badly damaged as to make her un-navigable and a number of serious hits had been sustained on the hull “betwixt wind and water”. During this pause, the British crew worked with such energy that control was regained within half an hour and the action resumed. At eleven o’clock, after another ninety minutes of close combat, the French frigate broke off the action and made off, pursued by the badly damaged Flamborough until noon on the following day.

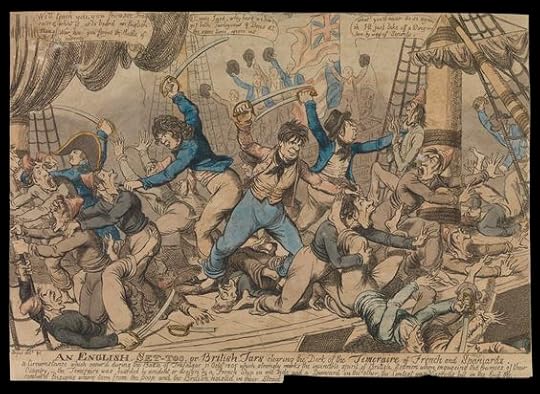

The aggressive and bloody-minded attitude of British seamen was widely admired – and feared.

HMS Bideford had also been heavily engaged. Shortly after seven o’clock – in darkness – she caught up with the French frigate that had been mauled by HMS Flamborough’s first broadside and attacked her. Bideford’s Captain Skinner was killed by a cannon-shot soon after and her Lieutenant Knollis, who now took command, fought on with determination for another hour until he was badly wounded and carried, dying, below. By this stage, Bideford’s spars and rigging had been damaged and casualties sustained. Morale remained high however and the master, a Mr, State, now senior officer, maintained the action. By ten o’clock the French ship’s fire slackened, her guns falling silent one by one. Intent on capturing her, Mr. State, who thought the enemy was going to strike, still continued his broadsides. In the last quarter-hour of combat, only four French guns fired. Under cover of darkness, but still being pounded, the French crew was however concentrating on repair of rigging. This proved so successful that the French frigate managed to draw away while Bideford, damaged and disabled, was unable to follow.

In an age when amputation was the only option for fighting gangrene, wounds sustained in battle could mean a lifetime of destitution in a nation that lauded its fighting men but didn’t care for them afterwards. (Has it really changed all that much?)

In the event, both French warships escaped, albeit seriously damaged, outfought by two smaller and more weakly armed ships. Considering the duration and intensity of the battle one is surprised that the British losses were relatively low – though grievous for the individuals concerned. Five officers and men were killed on board HMS Flamborough, and ten wounded, while HMS Bideford had ten killed and twenty-five wounded. Crews on each ship would have been around 130. Losses might have been higher had the action been fought in daylight, when accurate small-arms fire could have been poured down from fighting tops. Sending the French vessels to flight had the added advantage of protecting the convoy mentioned earlier. It was close enough to have heard the gunfire and it proceeded unmolested on its course.

The most remarkable feature of this action is the role played by morale. The decision of the British captains, outnumbered and outgunned as they were, to take the offensive from the start put the French on the back foot. They had lost the morale advantage even before Flamborough’s first broadside and it was never regained. The old saying that “what matters is not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog”, was once again proved valid.

Britannia’s MissionThis volume in the Dawlish Chronicle series is published in paperback and on Kindle, and is available to subscribers to Kindle Unlimited and Prime at no extra chargeClick image for details or to order

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery leading from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain is committed to its suppression but now there is pressure for more vigorous action . . .

Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Britain is reluctant to occupy them but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. But now the recently-established German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion . . .

With instructions that can be disowned in case of failure, Captain Nicholas Dawlish must plunge into this imbroglio to defend British interests. He’ll be supported by the crews of his cruiser HMS Leonidas, and a smaller warship. But it’s not going to be so straightforward . . .

Getting his fighting force up a shallow, fever-ridden river to the mission is only the beginning for Dawlish. Atrocities lie ahead, battles on land and in swamp also, and strange alliances must be made.

And the ultimate arbiters may be the guns of HMS Leonidas and those of her counterpart from the Imperial German Navy.

In Britannia’s Mission Nicholas Dawlish faces cunning, greed and limitless cruelty. Success will be elusive . . . and perhaps impossible.

Registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list by clicking on any one of the images below, will keep you updated on new books and facilitate e-mail contact between Antoine Vanner and his readers. You’ll also get six free short stories to upload to your Kindle or Tablet.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}

The post 6ths at bay – HMS Flamborough and HMS Bideford, 1760 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 22, 2021

Hoche Ramming Disaster 1892

Another peacetime ramming disaster:Hoche and Maréchal Canrobert 1892

Another peacetime ramming disaster:Hoche and Maréchal Canrobert 1892Ramming proved a successful manoeuvre in battle on only one naval battle – at Lissa in 1866 (click here to access an earlier blog-article about it) – but ram bows were seen as essential features for warships of almost all sizes in the half-century prior to WW1. Such bows – extended forward underwater to end in a sharp point that could gouge deep into an enemy hull – were to prove a major hazard in peacetime. Naval vessels exercising manoeuvres in close proximity to each other were obviously most at risk. Accidental ramming was to prove fatal in several major “blue on blue” disasters, several of which are described in the “Victorian Era” part of this site’s “Conflict” section (Click here to access). The tragedy of it all was that ramming would have been very difficult to achieve under modern battle conditions since improved long-distance gunnery, and higher ship speeds, would have made it virtually impossible to ram a major enemy vessel.

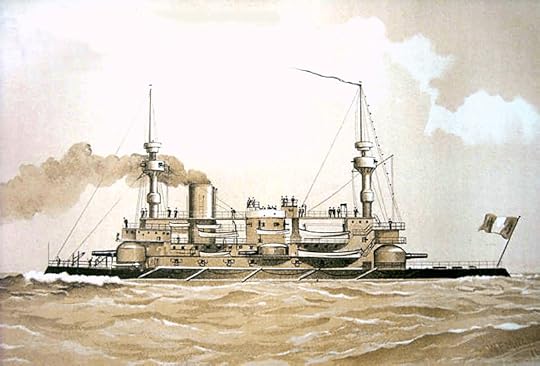

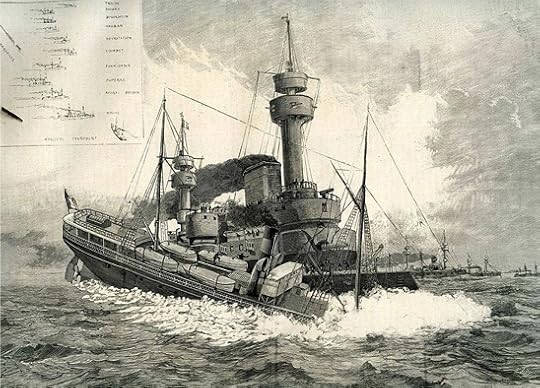

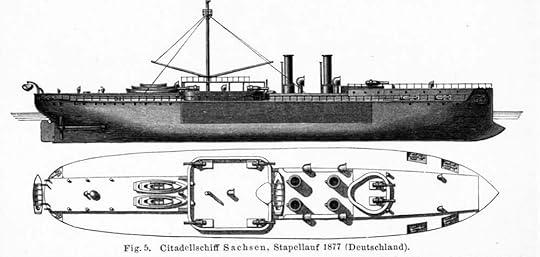

“Le Grand Hotel”

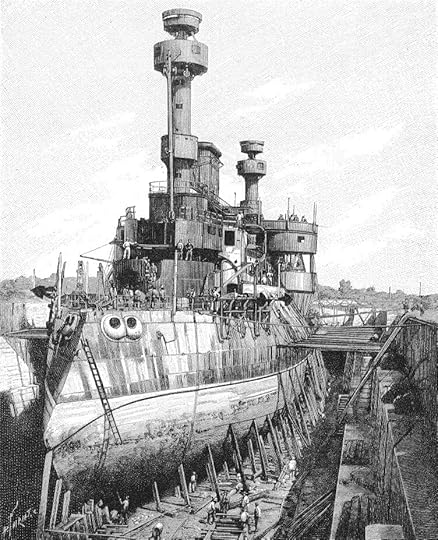

Another addition to the sad list of ramming disasters occurred in July 1892 and involved the French battleship Hoche. When she entered service in 1890, this vessel represented the epitome of a major warship designed as much for ramming as for carrying heavy guns. Entering service in 1890, this 12,000-ton, 322-foot vessel was protected along her waterline by an armoured belt 18-inches thick while her main armament, of two 13.4-inch and two 10.8-inch cannon, was protected by up to 16-inches of armour. Two features were especially notable – the enormous and untidy superstructure, that led to her the nickname of “Le Grand Hotel”, and the long ram-bow that ended in a vicious point some eight feet below water level.

Hoche in drydock. Note the pointed ram

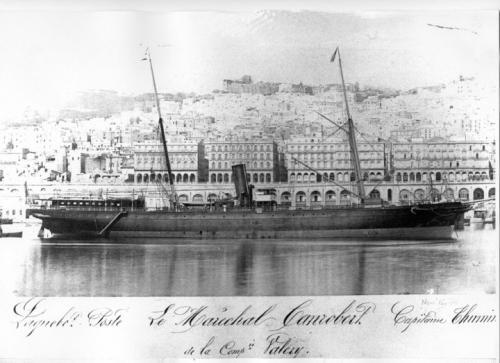

Heading for an unscheduled appointment with the Hoche on July 7th 1892 was the passenger steamer Maréchal Canrobert. Built in Scotland, and in service since 1881, this 1200-ton 250-foot iron-hull vessel carried mail and passengers between France itself and the French possessions in North Africa.

Maréchal Canrobert

On the day of the disaster, the Maréchal Canrobert was nearing Marseilles, following an uneventful passage from Bone (now known as Annaba) in Algeria. Some none miles south-west of her destination, the Maréchal Canrobert encountered the Hoche exercising in company with other naval units of the Mediterranean Fleet. Contemporary newspaper accounts are light on detail but an impression is gained that the Maréchal Canrobert’s captain brought his ship dangerously close to the warships, possibly to provide a better view of their manoeuvres to the passengers on deck. The Hoche had been firing her guns – and the propellants of the time yielded vast clouds of dense gunsmoke – and it was surmised that the Hoche’s officers did not see the passenger steamer until it was too late to take evasive action.

Contemporary illustration of the disaster

The Hoche’s ram bit deep into the Maréchal Canrobert, all but severing her in two. Naval disciple prevailed however and the shattered – and sinking – remains were secured to the battleship to facilitate transfer of survivors and boats were also launched. Despite these efforts the Maréchal Canrobert disappeared within eight minutes of the collision. The resulting death-toll amounted to 107. Blame for the disaster was placed on the captain of the Maréchal Canrobert.

Survivors being brought on board Hoche

The ram had claimed yet another peacetime victim but some two decades were to pass before such bows finally passed out of fashion. Such is the power of the paradigm.

Britannia’s SharkThis volume of the Dawlish Chronicles series of historical naval novels centres on the development – and role – of a prototype submarine. Based on actual events and personalities in the early 1880s, Britannia’s Shark paints a vivid picture of the skills and courage – bordering on madness – which was needed to operate such craft. Click here or on image below for more details.

Below are the nine Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Below are the nine Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the banner for more information or on the “BOOKS” tab above. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Prime Subscribers.

Six free short-stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;margin-top : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {padding-top : 0px !important;padding-right : 0px !important;margin-right : 1.92%;padding-bottom : 0px !important;padding-left : 0px !important;margin-left : 1.92%;}@media only screen and (max-width:1024px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}@media only screen and (max-width:640px) {.fusion-body .fusion-builder-column-0{width:100% !important;}.fusion-builder-column-0 > .fusion-column-wrapper {margin-right : 1.92%;margin-left : 1.92%;}}.fusion-body .fusion-flex-container.fusion-builder-row-1{ padding-top : 0px;margin-top : 0px;padding-right : 20px;padding-bottom : 0px;margin-bottom : 0px;padding-left : 20px;}The post Hoche Ramming Disaster 1892 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 14, 2021

18th Century Naval Artists Part 2

Naval Artists of the 18th Century – Part 2

Naval Artists of the 18th Century – Part 2Creating the Image of the British Seaman

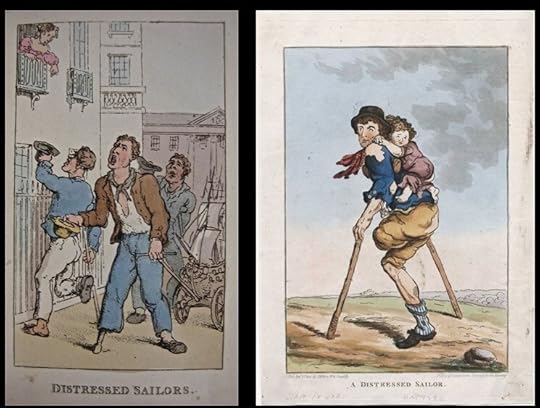

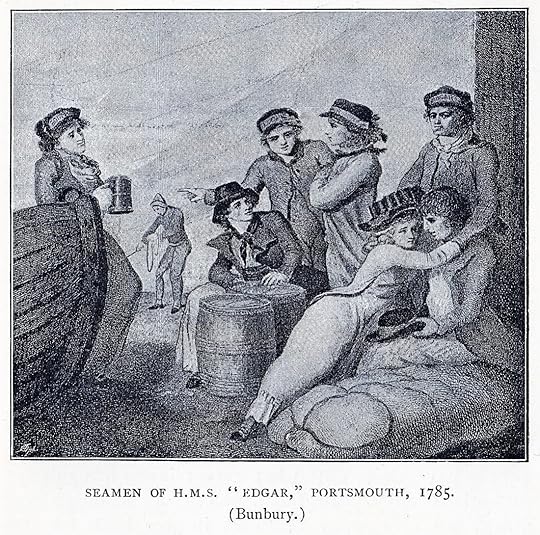

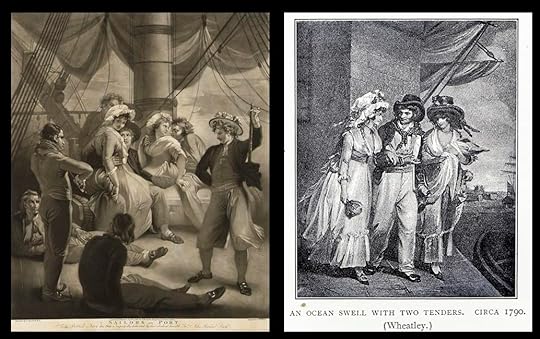

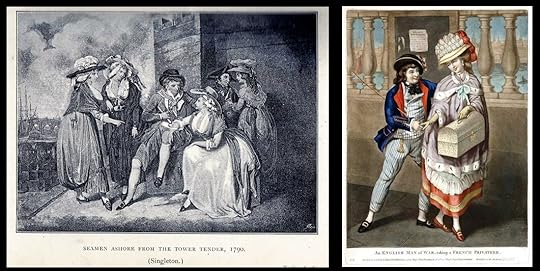

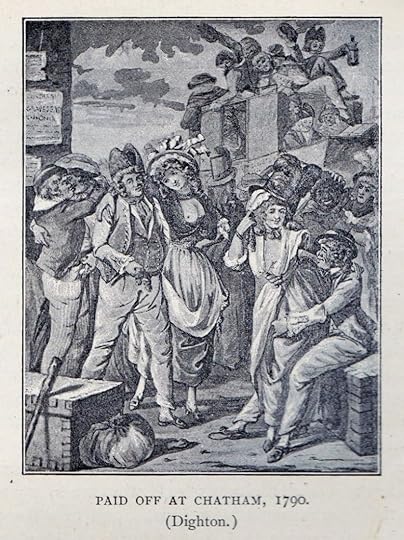

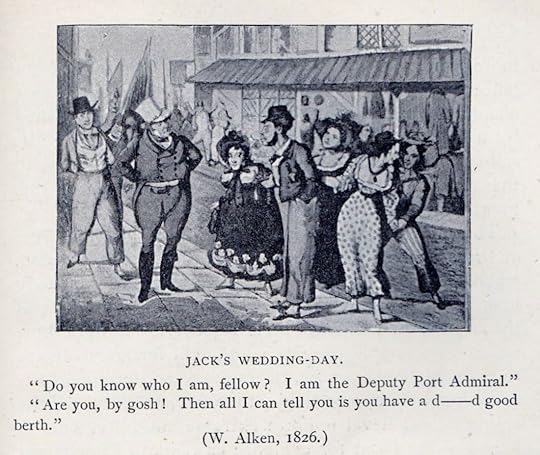

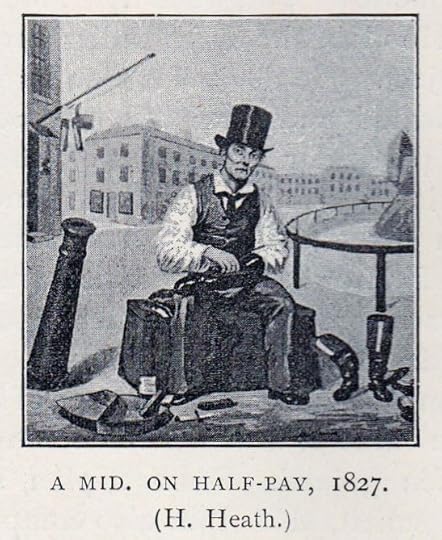

In the first part of this occasional series, which appeared on my blog recently, I discussed the remarkable career of Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg. (Click here to read if you missed it then.) He was a painter of considerable renown who produced remarkable pictures of naval actions but it is likely that the vast majority of people in that period never had the opportunity to see them, or others like them. In that age of great naval engagements, and in which the seaman came to be seen as a heroic – though poorly remunerated – figure, it is likely that the popular image was created by engravings and prints. Often, but not invariably, based on larger paintings, these could be cheaply produced and sold at prices affordable by all but the poorest homes. For residents of inland towns and rural areas, some of whom may have gone through life without seeing the sea or a seaman, these prints provided the image of “Rule Britannia” incarnate. Frequently framed, they were to prove of great longevity – and indeed a country public-house near my previous home has got a large number which have possibly hung there since they were purchased two centuries or more ago.

Cheap as such prints were they were often based on work by artists of the first order. They are frequently humorous, often sentimental, and though the tone is often unheroic, even anti-heroic, one gets a strong impression of the pride, brash confidence and carelessness for danger that characterised the seamen of the time. One can well imagine them squandering their meagre pay on drink and women, throwing away in an evening the prize-money they had dreamed of for years and grumbling and swearing incessantly – but one can also imagine them accepting cold, injury and brutal punishment stoically and fighting like tigers when the occasion demanded. From these prints a picture emerges of the men who beat the French in war after war through the 18th Century and who, at Trafalgar, were to secure British naval dominance for the next century.

Cheap as such prints were they were often based on work by artists of the first order. They are frequently humorous, often sentimental, and though the tone is often unheroic, even anti-heroic, one gets a strong impression of the pride, brash confidence and carelessness for danger that characterised the seamen of the time. One can well imagine them squandering their meagre pay on drink and women, throwing away in an evening the prize-money they had dreamed of for years and grumbling and swearing incessantly – but one can also imagine them accepting cold, injury and brutal punishment stoically and fighting like tigers when the occasion demanded. From these prints a picture emerges of the men who beat the French in war after war through the 18th Century and who, at Trafalgar, were to secure British naval dominance for the next century.

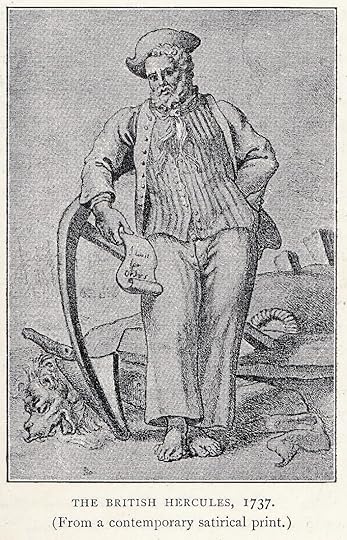

According to a Late-Victorian source (The British Fleet by C.N.Robinson, 1894), the earliest known depiction of a British blue-jacket was “The British Hercules”, dated 1737. He holds a scroll that says “I wait for orders” and this may refer to the two-years of fruitless negotiations with Spain which were then in progress – leading eventually to the splendidly-named War of Jenkin’s Ear. The most memorable exploit of the Royal Navy in this conflict was Anson’s voyage around the world in HMS Centurion.

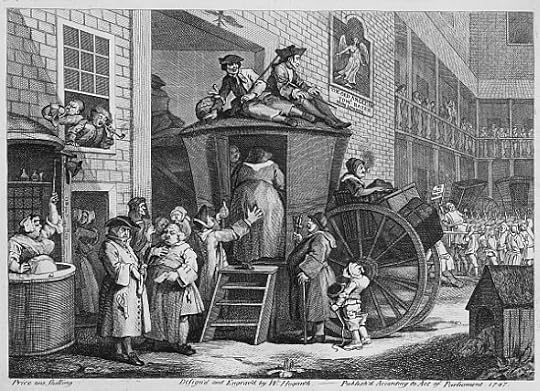

An engraving by Boitard entitled “The Sailor’s Return” shows an officer who has come back with Anson and in the background the treasure captured in the Spanish “Manilla Galleon” is being conveyed to London under the armed escort of sailors and marines. Louis Philippe Boitard was of French extraction, but settled in London. Robinson notes rather primly that “Some of Boitard’s pictures are too coarse for reproduction, notably that of “The Strand in an Uproar” – some sailors retaliating for the ill-treatment of one of their messmates in a house of ill-fame by throwing the furniture into the street”. I regret that I have been able to find a copy to include with this article!