Antoine Vanner's Blog

October 16, 2025

The Great Siege of Gibraltar, 1779 – 1783

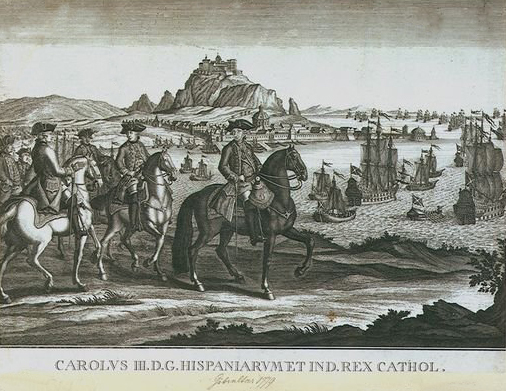

What was later hailed as The Great Siege of Gibraltar (1779-1783) was one of the great epics of the American War of Independence , even though it took place far from American shores. Gibraltar had been captured by Britain in 1704 and in the intervening years “The Rock” was heavily fortified, batteries and tunnels being hewn out of the rock itself. Its availability as a naval base in the Anglo-French wars of the mid-18th Century was of major strategic value to Britain, lying, as it did, on the entrance to the Mediterranean. It was not surprising therefore that during the American War of Independence (1775-83) its capture was an objective of the greatest importance for Britain’s enemies. France had joined the conflict in 1778 and Spain was to do likewise in the following year. Plans were immediately put afoot to seize Gibraltar. Spanish troops constructed siege-lines across the mile-wide isthmus connecting Gibraltar to the Spanish mainland and a close-blockade was initiated by Spanish vessels operating out of Algeciras, across the bay from The Rock. A more powerful Spanish naval force – eleven line-of-battle ships and two frigates – was based at Cadiz, some 60 miles to the west so as to intercept British reinforcements.

British forces – some 5300 troops under Governor-General, General George Eliott, and including Hanoverian and Corsican contingents – had already begun strengthening the defences. This was to make an attack across the isthmus difficult and increased the importance of the naval blockade. General Elliott placed special emphasis on the value of heated shot and ordered building of more furnaces and grates for the purpose. However, strong the Gibraltar defences might have been, the nature of the terrain meant that its ability to provide sufficient food, whether vegetable or animal, was limited in the extreme. By the end of 1779 bread was being made available only to children and the sick, the rest of the garrison being fed with increasingly scarce salt meat, hard-tack biscuits and a little rice. Given this diet, and the shortage of vegetables, it was not surprising that scurvy should make its appearance.

Relief arrived in January 1780 when Admiral George Rodney, after defeating the Spanish Cadiz fleet in the First Battle of Cape St. Vincent, arrived with over 1000 reinforcements and sufficient supplies to allow Gibraltar garrison to continue to hold out, albeit still on short-commons. The siege continued however through another increasingly hungry year, with indecisive fighting along the landward siege-lines and a few small fast blockade-runners carrying limited supplies from the British base at Minorca.

It was not until April 1781 that a massive British naval force – 29 ships of the line escorting 100 store ships – commanded by Vice Admiral George Darby reached Gibraltar despite Spanish efforts to intercept it. (The analogy with the huge “Operation Pedestal” convoy to relieve Malta in 1942 is very striking). The enemy was unable to prevent Darby carrying Gibraltar’s civilian population to Britain when he withdrew, thus reducing the pressure of “useless mouths” on food supplies.

In late November 1781, fearing that the enemy land-forces were about to make an attack from the siege lines, General Eliot launched half the British garrison on a pre-emptive strike or “sortie”. This succeeded brilliantly, carrying trenches, spiking batteries and destroying supplies. The British attackers then withdrew, having done enough damage to prevent an immediate assault. But the siege still dragged on.

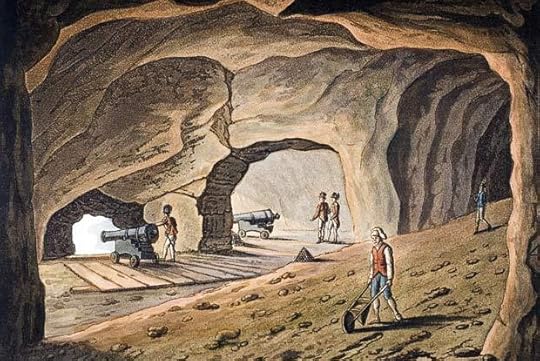

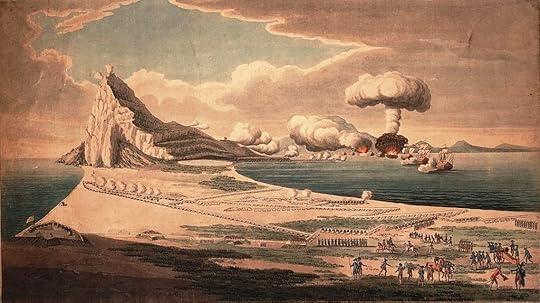

The climax was to come in September 1782 when combined French-Spanish forces launched a massive attack. Some 35,000 Spanish and 8000 French troops, supported by heavy artillery, were dedicated to the land assault but the threat from seaward was even more daunting. Eighteen ships-of-the-line, 40 gunboats and 20 bomb ketches were deployed. The most notable innovation was however use of “floating batteries”, mounting 138 heavy cannon, which were towed into position to take Gibraltar’s shore fortifications under fire. Designed by an eminent French engineer, D’Arcon, these batteries were supposed to be impervious to “heated shot”. This latter point is of special significance.

Accounts of naval operations against shore fortifications in the “Age of Fighting Sail” make frequent references to the use of “heated shot” – cannon balls warmed to white heat in furnaces before firing. When used against wooden ships such shot was capable of setting their targets ablaze. For obvious reasons the ability of sailing vessels to respond in kind was all but impossible and heated shot remained the perquisite of shore batteries, many of which equipped with specially built furnaces. Each glowing ball was carried to the gun by two men, having between them a strong iron frame. The gun was loaded with a powder charge in the usual way, but with two heavy wads, one dry and the other slightly damped, to separate the powder and the ball. The chance of the wadding taking fire must always have been present and the consequences of this would have been deadly. Loading guns in this way must have been a nerve-racking business.

French confidence in their floating batteries ability to withstand such attack was misplaced – the heated shot was about to come into its own. To supplement the usual portable furnaces, which were insufficient to supply the demands of the artillery, Governor Eliot ordered large bonfires to be kindled. On these the cannon-balls were thrown – they were referred to by the gunners as “hot potatoes”. Heated almost to incandescence the shot was transported to the guns in wheelbarrows filled with sand.

The floating batteries, unable to manoeuvre without assistance, proved to be highly vulnerable. Three took fire and exploded while another seven were so heavily damaged that they had to be withdrawn with high casualties. The Count d’Artois (1757-1836), brother of the doomed French King Louis XVI, and himself fated to reign as Charles X from 1824-1830, had hastened from Paris to observe this “Grand Assault”, in full expectation of a capitulation. He arrived instead in time to see the total destruction of the floating batteries and a large part of the combined fleet. The land attack was repulsed no less successfully. (It is ironic to note that Charles would later be a refugee, and an honoured guest, in Britain from 1805-1814, living in comfort in London’s South Audley Street, London, only returning to France when Napoleon fell and the Bourbons were restored).

Recognising that this “Grand Assault” had failed, the French and Spanish continued the siege as before, still in the hope of starving out the desperately poorly supplied British garrison. Measures were meanwhile afoot in Britain to send a large relief force –34 ships-of-the-line and 31 transports laden with food and ammunition as well as further troop reinforcements – under Admiral Richard Howe. It arrived off Cape St Vincent in early October and the French-Spanish force sent to intercept it was fortuitously scattered by a gale, allowing Howe an easy entry into Gibraltar.

Now strongly reinforced, the Gibraltar garrison held out until the end of hostilities in February 1783 the siege was lifted. With a duration of three years and seven months it was the longest siege in British history and the battle-honour of “Gibraltar” was to one of the most highest prized that any regiment might justly boast of.

The siege was recognised as an epic in its own time, as witnessed by the paintings made of it by several distinguished artists. The ultimate accolade was perhaps a “bardic song” about the relief set to music by Mozart and of which only a fragment remains. Unfortunately, Mozart didn’t like the style of the poem and never completed the work!

Nautical Fiction of the Age of Fighting Steam:Britannia’s Spartan It’s 1882 and Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

It’s 1882 and Captain Nicholas Dawlish RN has just taken command of the Royal Navy’s newest cruiser, HMS Leonidas. Her voyage to the Far East is to be a peaceful venture, a test of this innovative vessel’s engines and boilers.

Dawlish has no forewarning of the nightmare of riot, treachery, massacre and battle he and his crew will encounter.

A new balance of power is emerging in the Far East. Imperial China, weak and corrupt, is challenged by a rapidly modernising Japan, while Russia threatens from the north. They all need to control Korea, a kingdom frozen in time and reluctant to emerge from centuries of isolation.

Dawlish finds himself a critical player in a complex political powder keg. He must take account of a weak Korean king and his shrewd queen, of murderous palace intrigue, of a powerbroker who seems more American than Chinese and a Japanese naval captain whom he will come to despise and admire in equal measure. And he will have no one to turn to for guidance…

Britannia’s Spartan sees Dawlish drawn into his fiercest battles yet on sea and land. Daring and initiative have already brought him rapid advancement and he hungers for more. But is he at last out of his depth?

For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.auThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Great Siege of Gibraltar, 1779 – 1783 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

October 2, 2025

Royal Navy warship, daily routine, late-19th Century

Routine on a Royal Navy warship, late-19th Century

Routine on a Royal Navy warship, late-19th CenturyWhen one is interested in the navies of the late 19th Century, and especially when writing naval fiction set in that era, as I do in the Dawlish Chronicles, it is relatively easy to access information about the ships themselves, their armament, their machinery and their performance. Somewhat more difficult is running down information on operations of the period, especially the myriad of small actions undertaken by the Royal Navy, many which involving landing of “naval brigades” of anything from a few dozen to several hundred men. What is hardest of all to pin down information on are the realities of daily shipboard-routine and the life led by officers and men.

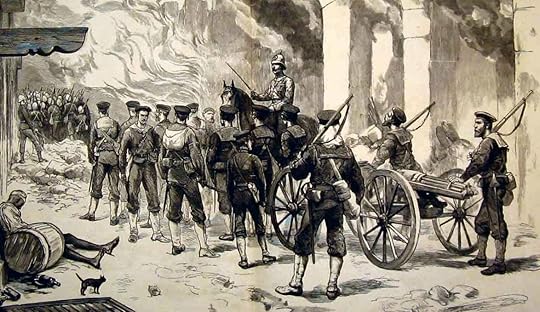

A Naval brigade quelling rioting in Alexandria in 1882.

Much of the Royal Navy’s active service in this era consisted of interventions onshore

In view of this, I was recently delighted to run down a volume, published in 1901 and entitled “The Handy Man, Afloat and Ashore”. The term “Handy Man” was used in this period to refer to seamen, recognising the fact that, living in a self-contained world for weeks or months, they were called on to manage or cope with any emergency or problem that might confront them. The author of this work was the Reverend G. Goodenough, an Anglican chaplain who, by virtue of his position and duties, gained insights to the culture, attitudes and behaviour of “the lower deck” which other officers could not easily get.

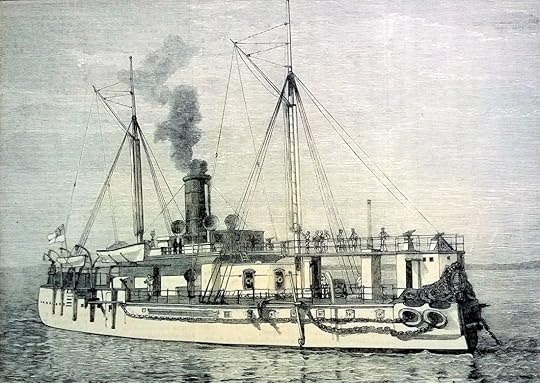

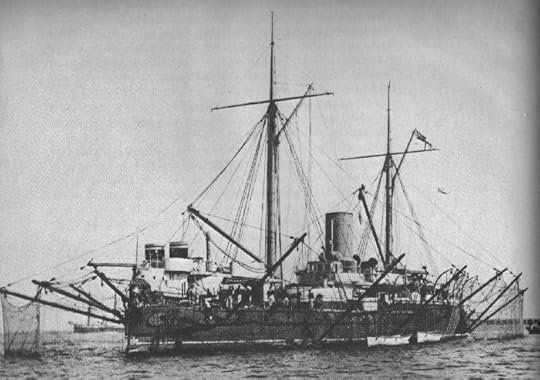

HMS Hotspur, a small and badly designed ironclad of the period. Note absence of torpedo nets at this early stage in her career

I have found of particular interest the details of the typical daily training routine for a large ship when in harbour. It was very intense and in the case of a battleship, such as HMS Trafalgar of 1887, on which Goodenough served, some exercises would involve several hundred men out of a total crew of 580. Sunday was a day of rest, other than for the morning religious service, but the six other days were well filled, as below:

Monday

Forenoon – General drill. Prepare for action and rig out torpedo nets.

Afternoon – Small-arm drill and gymnastics. 6 p.m. wash clothes. Inspection of guns.

HMS Hotspur again, but now equipped with a “crinoloine” of anti-torpedo netting to be deployed when at anchor. This shows the vessel in the middle of the process of their deployment. Like all such other activities, ships competed to reduce the time needed for this to the minimum – hence the drills on Monday afternoons and Tuesday mornings.

Tuesday

Forenoon – Scrub hammocks every other week. Torpedo exercise. Drill by divisions.

Afternoon – Boat-sailing. Small-arm drill. Gymnastics. Inspection Of guns. Exercise manoeuvres of steamboats.

Wednesday

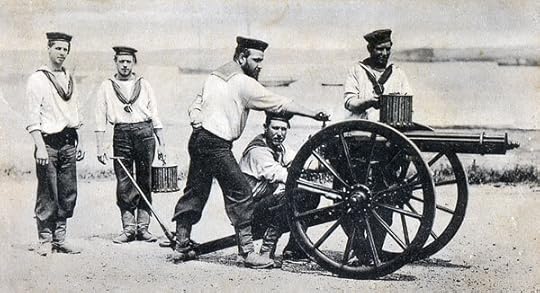

Forenoon – Torpedo exercise. Out torpedo-nets. Field-gun drill on shore if possible. Marines drill.

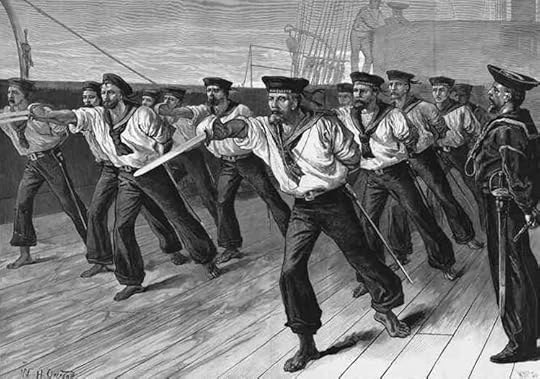

Afternoon – Cutlass exercise. Inspection of mines, electric cables,and circuits of guns. Midshipmen and boys at gun, small-arm drill.

Cutlass drill in the 1880s – note the bare feet, still normal at this time

Thursday

Forenoon – Exercise landing parties-ashore if possible. Drill in passing up ammunition. Test hydraulic machinery. Muster clothes and bedding.

Afternoon – Make and mend clothes. Smoking permitted.

Landing party excercising with a Gatling on a field carriage. At sea this weapon would be most likely mounted in one of the tops. Larger ships also carried seven or nine-pounder field guns that could be broken down into parts for easy manhandling.

Friday

Forenoon – General quarters for action

Afternoon – Boat drill. Test gun-cotton. Once a month fire quarters.

HMS Trafalgar, in which the Rev. G. Goodenough served

Saturday

Clean ship. Test ship’s pumps.

On one Monday in the month the bedding was aired on the ridge ropes and hammock nettings – photographs of ships from all navies of the period sometimes show them festooned with drying bedding and clothing. Thursdays were muster day twice a month and once a quarter the Articles of War are read and new regulations are made known.

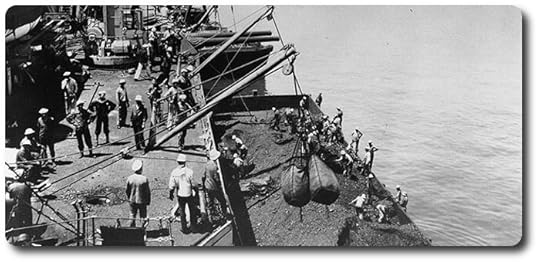

In addition, the ships of the period needed to take on coal at intervals – thousands of tons in the case of larger ships. The entire crew was involved in transferring the coal from lighters or colliers alongside, swinging it across on slings and dumping it down openings to the bunkers below. The worst duty of all fell on the trimmers who, working in confined space and often in very high temperatures, were required to distribute the coal evenly using shovels and wheelbarrows. Individual ships vied with each other to set coaling records – by World War 1 rates of 200 to 300 tone per hour were being achieved.

Coaling – always a filthy job. Seen here on an American battleship circa 1909

The Reverend Goodenough, who did not take part in the physical labour involved, had a breezy, even patronising, view of how crews approached it. He noted that “The men are as cheery as the (black) minstrels they resemble. In spite of the noise and the filth it is a jolly scene. Indeed, I rather liked coaling ship days (when I couldn’t get ashore) up to the time when the last bag was in and stowed, and then I wanted to be elsewhere. For, without a moment’s delay, hoses were got out, branch- pipes fitted and the ship presented a weird scene of grimy figures, up to the in liquid dirt, sending cascades of water into every nook and corner and driving me from post to pillar, and Pillar to post in the vain search for rest the sole of my foot, even my cabin being no longer a sure refuge, for that was possession Of by my servant busily trying to remove the fine coating of coal-dust that in spite of all precautions manages to find its way everywhere. So I learnt that it is the part of a wise man to be out of the ship when they are washing down, if he isn’t himself employed on that particular job of work.”

The chaplain also recounted what he described as “laughable incident at Port Said in my old troopship days.” On this occasion contracted local labour, rather then the ship’s own crew, undertook the coaling. One suspects that these Egyptians were not paid generously, for they “struck for more pay, and, not getting what they demanded, refused to ship (the coal) for us. So our own men were told off to do the job, which no sooner did the natives perceive than they repented and tried to begin work. But this didn’t suit our fellows at all. So the next thing we knew was that the bluejackets and marines were taking these gentlemen by the scruff of the neck, as they tried to board the coal- barges, and chucking them with infinite zest into the canal.”

Man of the cloth or not, the reverend chaplain’s attitude tells much about the values of the time and reflects little Christian Charity . There could only be a residue of bitterness following such an incident, which one suspects was not unique. It’s therefore not surprising that payback-time would eventually come when the Egyptians would nationalise the Suez Canal a half-century later, triggering a major crisis that culminated in Britain’s 1956 Suez debacle.

Having as far as possible avoided the hardships of coaling the chaplain ends on what today sounds like a patronising note: “Coaling over and the ship washed down, the forecastle is always alive in the evening with music, vocal and instrumental. Banjos, mandolins, guitars, fiddles, are brought out and the night resounds with song after song. The harder the day’s work has been the heartier is the singing, as a rule.” One suspects that this may be closer to Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore than to reality.

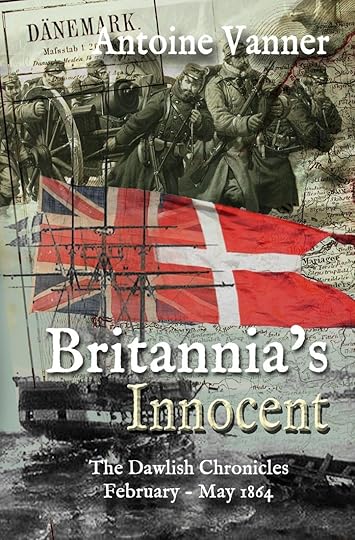

Start the 12-volume (so far) Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

Across the Atlantic, another conflict rages. The American Civil War spills onto the world’s oceans as Confederate raiders strike Union shipping as far away as the East Indies. Now a powerful new ironclad, nearing completion in a British shipyard, threatens to shift the balance—if she can ever be armed. The Union wants her destroyed. The Confederacy wants her unleashed. And Denmark may yet gain her, if secret bargains can be struck.

Into this maelstrom steps a young Royal Navy officer: Nicholas Dawlish. Newly returned from service in the West Indies, Dawlish volunteers to aid Denmark, drawn by duty, adventure – and divided loyalties. Thrust into the brutal realities of siege, bombardment, and bitter fighting on the cold waters of the North Sea, he must learn fast if he is to survive.

In later years, Dawlish will be known as a shrewd and battle-hardened commander. But in 1864 he is still untested—an innocent on the brink of war.

The first novel in the acclaimed Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Innocent begins the saga of a man whose fate will be shaped by courage, conflict, and the tides of history.

For more details, click below: For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post Royal Navy warship, daily routine, late-19th Century appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 25, 2025

Admiral Charles Wager’s meteoric career – the first step

I dipped some time ago into a magnificently titled 19th Century book called:

“THRILLING NARRATIVES OF MUTINY, MURDER AND PIRACY, a weird series of tales of shipwreck and disaster,from the earliest part of the century to the present time,with accounts of providential escapes and heart-rending fatalities”

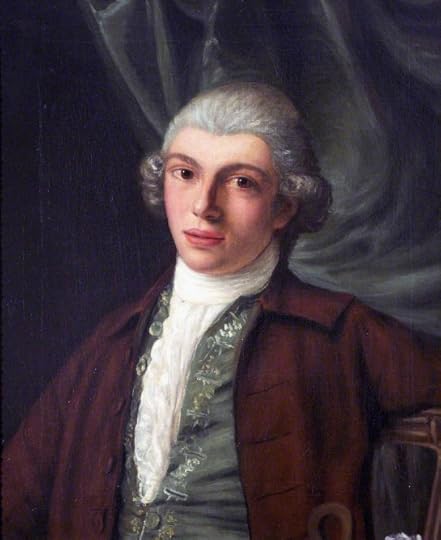

Charles Wager in later life

The anonymous author might not have been gifted in thinking up short, snappy titles, but there’s no doubt about what this volume published in New York contained. I was particularly taken by a short account of an exploit in the early years of a cabin boy who galvanised a ship’s crew to withstand attack by a French privateer – a story that sounds too good to be true. A little further digging did indicate however that the case was a true one and that the boy in question, Charles Wager, was to ascend to dizzy heights in his later life. I’ll quote extensively (in italics) from the account in the book as its period-style gives it a charm of its own.

Though the father and grandfather of Charles Wager (1666-1743) had seen service at sea under both Cromwell and Charles II, he lacked the patronage that would have allowed him easy entry to the Royal Navy. His mother had married a Quaker merchant in London after his father’s death – this being a time when Quakers were a new and often suspect sect. Through his step-father however, Wager gained an apprenticeship with a Quaker from Barnstable, Massachusetts, a merchant ship’s captain called John Hull who sailed regularly between Britain and the Americas. The key event of Wager’s early career, as told below, must have happened before 1689, the first year in which he appears in the Royal Navy’s records.

The Battle of La Hogue, 1692, the decisive Royal Navy victory of this period, ending the threat of a French invasion, as Trafalgar was also to do in 1805 (by Benjamin West 1738-1820)

Britain was at war with France in the late 1680s – a condition that was to be almost the norm from this period until 1815, interspersed with only brief intervals of peace. Though war was being waged at sea, and with merchant shipping the much sought-for quarry of privateers, Captain John Hull, as a Quaker, refused to arm his ship. On one of his voyages from America and close to the British coast, his vessel was chased, and ultimately overhauled, by a French privateer. Hull “had used every endeavor to escape, but seeing from the superior sailing of the Frenchman, that his capture was inevitable, he quietly retired below: he was followed into the cabin by his cabin boy, a youth of activity and enterprise, named Charles Wager. He asked his commander (Hull) if nothing more could be done to save the ship—his commander replied that it was impossible, that everything had been done that was practicable, there was no escape for them, and they must submit to be captured.”

Notwithstanding his age – and obviously unconvinced by Quaker pacifism, however much he might be beholden to Hull – Wager went on deck, summoned the crew and told them what their captain intended. Then, “then, with an elevation of mind, dictated by a soul formed for enterprise and noble daring, he observed, “if you will place yourselves under my command, and stand by me, I have conceived a plan by which the ship may be rescued, and we in turn become the conquerors.” The sailors no doubt feeling the ardor, and inspired by the courage of their youthful and gallant leader, agreed to place themselves under his command. His plan was communicated to them, and they awaited with firmness, the moment to carry their enterprise into effect.”

The Battle of Lagos, 1693, a French victory over British-Dutch forces escorting a convoy. Half the merchant ships were lost – 90 in total, 40 taken as prizes and the remainder burned. (By Théodore Gudin (1802 – 1880)

When French vessel grappled the surrendered ship shortly after and a boarding party began to cross to claim their prize, these “exhilarated conquerors, elated beyond measure, with the acquisition of so fine a prize, poured into the vessel cheering and huzzaing; and not foreseeing any danger, they left but few men on board their ship. Now was the moment for Charles Wager, who, giving his men the signal, sprang at their head on board the opposing vessel, while some seized the arms which had been left in profusion on her deck, and with which they soon overpowered the few men left on board; the others, by a simultaneous movement, relieved her from the grapplings which united the two vessels.”

Battle of Beachy Head, 1690, another murderous encounter of the period, this time a French tactical victory over the British and Dutch. (By Théodore Gudin (1802 – 1880)

Wager had managed the near-impossible, essentially hijacking the attacker. “Our hero now having the command of the French vessel, seized the helm, and placing her out of boarding distance, hailed, with the voice of a conqueror, the discomfited crowd of Frenchmen who were left on board of the peaceful bark he had just quitted, and summoned them to follow close in his wake, or he would blow them out of water, (a threat they well knew he was very capable of executing, as their guns were loaded during the chase.)”

It is probably an understatement that the French “sorrowfully acquiesced with his commands, while gallant Charles steered into port, followed by his prize. The exploit excited universal applause—the former master of the merchant vessel was examined by the Admiralty, when he stated the whole of the enterprise as it occurred, and declared that Charles Wager had planned and effected the gallant exploit, and that to him alone belonged the honor and credit of the achievement.”

The battle off Cartagena, 28 May 1708 known as “Wager’s Action”, in which

he became a rich man through prize money. Painting, via Wikipedia, by Samuel Scott (1702-1772)

The battle off Cartagena, 28 May 1708 known as “Wager’s Action”, in which

he became a rich man through prize money. Painting, via Wikipedia, by Samuel Scott (1702-1772)

This exploit gained for Wager what had previously been beyond his reach – a footing in the Royal Navy. He was appointed a midshipman, and by 1689 was listed as a lieutenant on the frigate HMS Foresight. His career thereafter was to be an active one in both naval and diplomatic service, one that, culminated in appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty – the head of the Royal Navy – from 1733 to 1742. Prize money was to make him immensely rich but “it is said that he always held in veneration and esteem, that respectable and conscientious Friend (i.e. Quaker), whose cabin boy he had been, and transmitted yearly to his OLD MASTER, as he termed him, a handsome present of Madeira, to cheer his declining days.”

The cabin boy had come a very long way.

Britannia’s Wolf Read it as a stand-alone novel or as part of the Dawlish Chronicles series

The year is 1877, and the Russo-Turkish War is entering its final, brutal phase…

With a Russian victory threatening Britain’s strategic interests, naval officer Nicholas Dawlish is dispatched on a daring and dangerous mission. Seconded to the Ottoman Navy, his task is to disrupt Russian supply lines in the storm-tossed waters of the Black Sea. But winter tightens its grip, and the Turkish military teeters on the brink of collapse.

As ironclads clash and savage fighting rages on land, Dawlish must contend with Cossack cavalry, ruthless Kurdish irregulars—and the deadly intrigues of the Ottoman court, where rival princes vie for power amid the empire’s decay.

In the heart of war and betrayal, Dawlish is drawn into a love he neither seeks nor dares to accept. A love that may cost him everything…

Duty, ambition, honour—and forbidden desire—collide in this gripping volume of the Dawlish Chronicles.

Available in Paperback and in Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle unlimited read at no extra charge. Click below for purchase details.

For USA For UK & Ireland For Canada For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post Admiral Charles Wager’s meteoric career – the first step appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 11, 2025

The Survival of the SS Chimborazo, 1880

The Survival of the SS Chimborazo, 1880

The Survival of the SS Chimborazo, 1880 The second half of the nineteenth century saw steam power at sea come to maturity and, in combination with the linking of continents by submarine telegraph cables, underlie creation of a trading system of unprecedented global reach. Steam power allowed not only fast and cheap transportation of people and goods but regular scheduled services. The results were to be so impressive that it is easy to overlook the fact that such transportation remained dangerous in the extreme, and that the hazards involved were accepted as inevitable not only by wider society, but by those must directly affected, crews and passengers alike, with much stoicism, if not complacency. A good example is provided by the narrow escape of the steamer SS Chimborazo in February 1880.

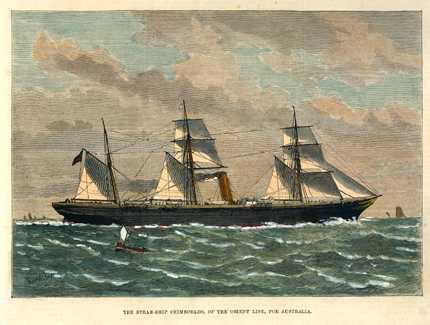

SS Chimborazo Image courtesy State Library of Victoria, H31030, Public Domain

Built in Glasgow in 1871, the 3,847-ton, 384-foot Chimborazo was to be employed in combined passenger and freight services between Britain and Australia until 1889. She was a well-regarded vessel, operated by respected and responsible owners from the Orient shipping group. As was common for the time she carried a sailing rig in addition to her steam engine. What is remarkable to modern eyes is that the engine should have been of such low power – 550 hp. This was not unique to the SS Chimborazo, since it applied to many steamers of her time, but it meant that there was no significant extra power to draw on in emergencies.

“The Last of England” by Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893). Emigration to Australia, seen here in 1850s, was a major feature of British life in the mid-19th Century

On February 8th 1880 the SS Chimborazo left the British port of Plymouth for what promised to be another routine voyage to Australia. Unlike many vessels of her time, she carried a Plimsoll Line loading mark and this was not exceeded. What seems strange to modern eyes is that she carried sheep on the foredeck – how many, and whether for consumption on board, or for improvement of stock in Australia, is not clear. For whatever reason, given the time of year and the likely weather conditions to be encountered, the conditions for these poor creatures must have been unenviable. The following day, February 9th, the Chimborazo was in the Bay of Biscay. There she encountered severe, but not yet alarming, weather.

The owners were subsequently to write that “the Chimbozaro was making good weather, merely taking a little water over her bow, which made it desirable to move the sheep from that part of the ship to further aft. The passengers were standing about the deck enjoying the bright morning.” This bland statement disguised the fact that the sheep were moved for cover into the smoking room, apparently a small deckhouse, and that the human occupants were evicted. The owners’ statement continued: “There was no cause for apprehending danger… until a large wave was seen approaching on the starboard bow side. It was hoped that it would break before reaching the ship but unfortunately, it fell upon the deck and the whole mischief was the work of a few seconds”

The SS Chimborazo heeled over on to her port side and the wave lashed across the spar-deck for some fifty feet abaft the funnel. The heavy steam launch which was stored there was torn from its berth and washed overboard, taking with it everything in its path. Six out of eight lifeboats carried were swept away, as were the skylights to the engine room and galley, and the saloon companion, all of which allowed water to cascade down within, as well as various other deck fittings. The entire smoking room, with the unfortunate sheep inside, was also wholly washed away. There were other animal victims also, for it appears that hens were kept in coops on deck and “the chief engineer, who hastened down into the stoke hole expecting to find water, found the firemen scrambling among themselves for the poultry which had been blown down the ventilators.” Three people had been washed overboard, another died almost immediately from injuries and a large number of passengers and crew suffered lesser injuries. The death toll would have been higher had the smoking room not have been cleared of smokers to provide shelter for the sheep.

Few painters have conveyed the fury of a storm with such skill as Russian master Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900)

The SS Chimborazo turned back to Plymouth and in order to get her back to sea as quickly as possible missing fittings were replaced by others taken from her sister ship SS Cuzco, which was then in port. By February 18th she was back at sea again, with 330 passengers and a large cargo, and heading to Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. Her problems seemed to be about to start all over again for that night she encountered south-west winds of hurricane strength and she was to lie-to for the next two days. No damage was sustained however and the subsequent voyage to Australia proved uneventful.

What is remarkable about this affair is how everybody involved seemed to take it in their stride – not just the authorities, who did not investigate what could have been a major disaster, and did not delay a very fast return to sea, but the passengers themselves. They seem to have accepted the hazards as somewhat of a normal feature of sea travel. The SS Chimborazo’s owners reported that “Not a word of complaint has been received from any passenger and we understand that they have as a body as well as individually expressed to Captain Trench and to others their high appreciation of the ship and of their treatment generally, a handsome sum having been subscribed soon after the accident in recognition of the good conduct of the crew.”

The SS Chimborazo had another fifteen years of useful life ahead of her, retiring from Australian service in 1889 and thereafter serving as a cruise liner that visited the Norwegian fjords until she was finally retired in 1895. All but forgotten today, her name would have been associated with a major disaster if events had turned out only so very slightly differently.

Britannia’s Wolf Read it as a stand-alone novel or as part of the Dawlish Chronicles series

The year is 1877, and the Russo-Turkish War is entering its final, brutal phase…

With a Russian victory threatening Britain’s strategic interests, naval officer Nicholas Dawlish is dispatched on a daring and dangerous mission. Seconded to the Ottoman Navy, his task is to disrupt Russian supply lines in the storm-tossed waters of the Black Sea. But winter tightens its grip, and the Turkish military teeters on the brink of collapse.

As ironclads clash and savage fighting rages on land, Dawlish must contend with Cossack cavalry, ruthless Kurdish irregulars—and the deadly intrigues of the Ottoman court, where rival princes vie for power amid the empire’s decay.

In the heart of war and betrayal, Dawlish is drawn into a love he neither seeks nor dares to accept. A love that may cost him everything…

Duty, ambition, honour—and forbidden desire—collide in this gripping volume of the Dawlish Chronicles.

Available in Paperback and in Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle unlimited read at no extra charge. Click below for purchase details.

For USA For UK & Ireland For Canada For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Survival of the SS Chimborazo, 1880 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

September 4, 2025

Merchant Service Nightmare in the Baltic, 1874

Baron Walter Runciman

Baron Walter Runciman (1847 –1937) was a classic case of a poor boy of high initiative “making good”. Born in Dunbar, Scotland, he ran away to sea at the age of twelve. A ship’s master himself by 21, he founded a shipping line and in due course became a major force in the British mercantile industry up to his death. On the way he was elected also as a Liberal Member of Parliament and was subsequently raised to the House of Lords.

Runciman’s reminiscences, published in 1905, leave no doubt as to the brutalities of life in the merchant service in the nineteenth century. They sweep away any notions we may have of “The Romance of the Sea”, as beloved by so many armchair-bound Victorians. One story is particularly harrowing – it has much about it of a Joseph Conrad novel or short story. and I paraphrase it below, his own words being indicated in italics.

Small trading brigs were vulnerable in extreme weather. Here is the wreck of the

Copeland

at South Shields,1861, a vessel probably similar to the Ocean Queen featured in this article (Painting by John Newington Carter)

Small trading brigs were vulnerable in extreme weather. Here is the wreck of the

Copeland

at South Shields,1861, a vessel probably similar to the Ocean Queen featured in this article (Painting by John Newington Carter)

“There are, however, phases of bravery, endurance, and resourcefulness that test every fibre of the seaman’s versatile composition,” Runciman writes, “The pity is so much of it is lost to us, but this again is owing to the sailor’s habitual reticence about his own career.” A characteristic instance of this occurred to me about six months ago. I had business in a shipyard, and the gateman who admitted me is one of the last of the seamen of the middle of the century.”

This man had been “for many years master of sailing vessels belonging to a north-east coast port. He is a fine-looking, intelligent old fellow. I knew him by repute in my boyhood days; he had the reputation then of being a smart captain, and owners readily gave him employment. After greeting me with sailor-like cordiality, he commenced to converse about the old days, and as the conversation proceeded the weird sadness of his look gradually disappeared, his eyes began to sparkle, and joy soon suffused his ruddy face.”

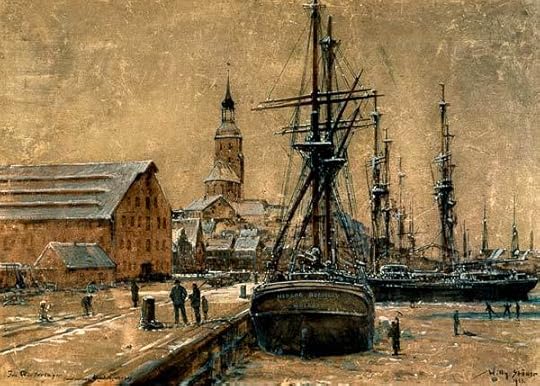

Small traders at the Baltic port of Wolgast (by Willy Stöwer 1864 – 1931)

Small traders at the Baltic port of Wolgast (by Willy Stöwer 1864 – 1931)

Runciman was however “reluctant to break the charm of it by introducing a subject that might be distasteful to him. It was my desire to hear from his own lips a tale of shipwreck which is virtually without parallel in its ghastly tragedy. I instinctively felt myself creeping on to sacred ground. As soon as I mentioned the matter his countenance changed and he became pensive. . . I saw the moisture come into his eyes and his breast heave with emotion, and it made me wish that I had not reminded him of it. At length he began to unfold the awful story.”

The old gateman had been master of a brig called the Ocean Queen. In her he sailed from a port in the Gulf of Finland in December, 1874, laden with timber. Close to the Swedish island of Gotland, a storm from the west “battered the vessel until she became water-logged and dismasted. The crew lashed themselves where they could, and huddled together for warmth to minimise the effects of the biting frost and the mad turmoil of boiling foam which continuously swept over the doomed vessel, and caked itself into granite-like lumps of ice. At intervals they would try to keep their blood from freezing by watching a “slant” when there was a comparative smooth, and run along the deckload a few times, keeping hold of the life-line that was stretched fore and aft for this purpose”

The horror of shipwreck doesn’t change through the ages. Two centuries before the loss of the Ocean Queen, the nature of the nightmare was conveyed by Pieter Mulier II (1637 – 1701).

The horror of shipwreck doesn’t change through the ages. Two centuries before the loss of the Ocean Queen, the nature of the nightmare was conveyed by Pieter Mulier II (1637 – 1701).

The storm abated after twelve hours “but they were without food and water, and no succour came near them. They held stoutly out against the privations for two days, then one after another began to succumb to the combined ravages of cold, thirst, and hunger. Some of them died insane, and others fought on until Nature became exhausted, and they also passed into the Valley of Death. There were now only the captain and a coloured seaman left.”

The wind – apparently from the north, now drove the shattered brig southwards towards the German coast. “On the fifth morning after she became water-logged the wreck stranded on a sandy beach two hours before daylight. The captain and his coloured companion attached themselves to a plank, and by superhuman effort reached the shore. They buried their bodies up to the waist in sand under the shelter of a hill, believing it would generate some warmth into their impoverished systems. Their extremities were badly frostbitten, and when they were discovered at daylight by a man on horseback who had been attracted to the scene of the wreck, they were both in a condition of semi-consciousness. He galloped off for assistance, and speedily had them placed under medical treatment, and under the roof of hospitable people.”

A small trading brig in a rough sea – merchant vessels in the era before wireless were “on their own” once out of sight of land. The great Ivan Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900) conveys this memorably.

A small trading brig in a rough sea – merchant vessels in the era before wireless were “on their own” once out of sight of land. The great Ivan Aivazovsky (1817 – 1900) conveys this memorably.

The consequences were dreadful for both men: A few days’ rest and proper attention made them well enough to be removed to a hospital. It was soon found necessary to amputate both of the coloured man’s legs, and also some of his fingers. The captain had the soles of his feet cut off; and he told me that he always regretted not having the feet taken off altogether, as he had never been free from suffering during all these years. He said the doctor advised it, but that he himself was so anxious to save them that he preferred to have the soles scraped to the bone, hoping that the diseased parts would heal; ‘but,’ said he with an air of sober melancholy, ‘they never have.’”

Runciman indicated that he had “been obliged to confine myself to a brief outline of this tale of shipwreck. There are incidents of it too painful to relate, and I am quite sure I am consulting the wishes of the narrator by abstaining from going too minutely into detail. The main facts are given, and they may be relied on as absolutely true.”

One wonders how many similar stories of extreme suffering at sea have been lost to us. The image of the crippled old captain eking out his last days as a gatekeeper, and of what the ultimate fate would have been of the man with him, is both haunting and disturbing.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

Across the Atlantic, another conflict rages. The American Civil War spills onto the world’s oceans as Confederate raiders strike Union shipping as far away as the East Indies. Now a powerful new ironclad, nearing completion in a British shipyard, threatens to shift the balance—if she can ever be armed. The Union wants her destroyed. The Confederacy wants her unleashed. And Denmark may yet gain her, if secret bargains can be struck.

Into this maelstrom steps a young Royal Navy officer: Nicholas Dawlish. Newly returned from service in the West Indies, Dawlish volunteers to aid Denmark, drawn by duty, adventure – and divided loyalties. Thrust into the brutal realities of siege, bombardment, and bitter fighting on the cold waters of the North Sea, he must learn fast if he is to survive.

In later years, Dawlish will be known as a shrewd and battle-hardened commander. In 1864 he’s professionally competent for his age — but an innocent in the deceits and betrayals of the world. He’ll learn the hard way.

The first novel in the acclaimed Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Innocent begins the saga of a man whose fate will be shaped by courage, conflict, and the tides of history.

For more details, click below: For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for details

The post Merchant Service Nightmare in the Baltic, 1874 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 21, 2025

“I’d prefer to be blown up!” – van Speijk at Antwerp, 1831

The revolt that led to the creation of modern Belgium as an independent state was the background to an act of insane heroism by a young Dutch naval officer, Jan van Speijk, whose (alleged) last words were to become an expression still in use today. This is his story.

The Netherlands and Belgium are today two separate nations, and have indeed had separate existences, in one form or another, for most of the time since the late sixteenth century. Up until 1806, the Netherlands had a complex republican form of government, though allowing however a hereditary role to Princes of the House of Orange. The nation fell under French control in 1795 and in 1806 it became the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the Emperor Napoleon’s younger brother Louis installed as King. What is today Belgium (allowing for frontier adjustments) was ruled as a province of the Hapsburg Empire from the seventeenth century until the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars.

King William I’s son leading Dutch-Belgian forces during the Waterloo campaign

As Napoleon’s power waned, and as he was sent in exile to Elba, the Great Powers of Europe supported creation of a single unified state, combining both regions, and henceforth to be known as “The Kingdom of the Netherlands.” Its sovereign was to be the current Prince of Orange, who took the title of King William I and who was also made ruler, under the title of Grand Duke, of the separate state of Luxembourg. The new Kingdom was functioning when Napoleon came back from Elba during “The 100 days” in 1815, and Dutch-Belgian forces were to fight against him at Waterloo.

Belgian rebels in Brussels 1830

For the next 15 years the northern, Dutch, and the southern, Belgian, parts of the kingdom lived uneasily together. Though adherents of both religions lived in all areas, the north was predominantly Protestant and the south predominantly Catholic. The situation was further complicated by the southern provinces containing both French-speaking Walloon and Dutch-speaking Flemish communities. Tensions increased and in the south resentment grew against what was seen as the Protestant hegemony by the House of Orange and its adherents. This discontent exploded in outright rebellion in Belgium in 1830. King William attempted to restore order but was hampered by mass desertion of troops hailing from the southern provinces. Unable to restore order, despite bloody street-fighting in Brussels and elsewhere, William withdrew his forces, though he maintained a blockade of Antwerp, and appealed to the Great Powers to resolve the problem. This resulted in the London Conference of European powers which recognised Belgium as an independent country. Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg was installed as “King of the Belgians”.

Dutch cavalry under attack in a Belgian town

Unhappy with this outcome, King William of the now truncated Netherlands – essentially the territory it consists of today – was to oppose the separation, culminating in an unsuccessful invasion of Belgium known as De Tiendagse Veldtocht (“The Ten Days’ Campaign”) which lasted from the 2nd to the 12th of August 1831. Despite initial successes, French intervention forced the Dutch to agree to an indefinite armistice. Faced with such opposition, William had no option but to withdraw, humiliated and smarting, but it was not until 1839 the Netherlands accepted Belgian independence by signing the Treaty of London. As one of its signatories, it was in line with the terms of this treaty that Great Britain entered World War I when Belgium was invaded by Germany in 1914.

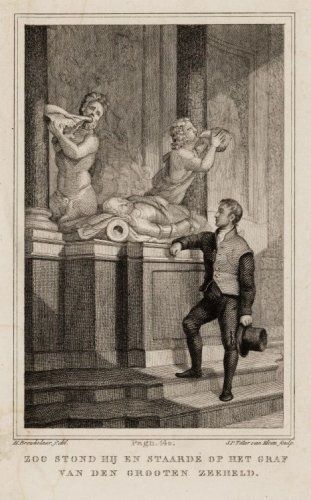

van Speijk’s romanticised youth

– admiring tomb of de Ruyter

Probably only one incident from this complex series of events is widely remembered in the Netherlands today. This was the exploit of the young Dutch naval lieutenant, Jan van Speijk (pronounced like “Spike” in English), who achieved immortality at Antwerp in February 1831. Dutch naval forces were maintaining a blockade of this important port – then as now, one of the largest in Europe, as it functioned as a commercial gateway to Germany. Van Speijk was in command of a small gunboat, one of many engaged in blockade duty, a more difficult task then than nowadays as many mouths of the Scheldt Delta, at the head of which Antwerp lies, were then open but which have since been closed off by dams.

Van Speijk’s background seems almost too good to be true for a popular hero. Born in Amsterdam in 1802, his parents died when he was a baby and he was brought up in an orphanage and subsequently trained as a tailor. Such a mundane career did not attract him and he instead joined the Royal Netherlands Navy in 1820. Thereafter he was to serve with distinction in the Dutch East Indies in the Boni Campaign of 1825 in the South Celebes. By 1830 he was a lieutenant – a very impressive achievement for a man who had started with such poor prospects. As the revolt in Belgium grew he was in command of Kanonneerboot Nummer 2 (Gunboat Number 2), a small sailing craft armed with a single cannon. On October 27th van Speijk performed so effectively in a bombardment of Antwerp that he was awarded a decoration.

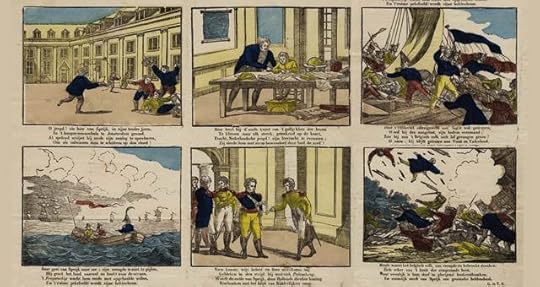

19th Century comic strip about va n Speijk’s li fe

The blockade continued through the winter and during this time van Speijk seems to have thought deeply – might have indeed been obsessed – about what he should do if his vessel were to fall into Belgian hands. In December 1830 he wrote to his niece that he would rather blow up his craft rather than surrender it, and he referred to an incident in 1606 when a Dutch captain had done just this to prevent seizure by the Spaniards. During new-year celebrations he told his crew the same and was allegedly applauded by them, though it is uncertain whether they thought that he was wholly serious.

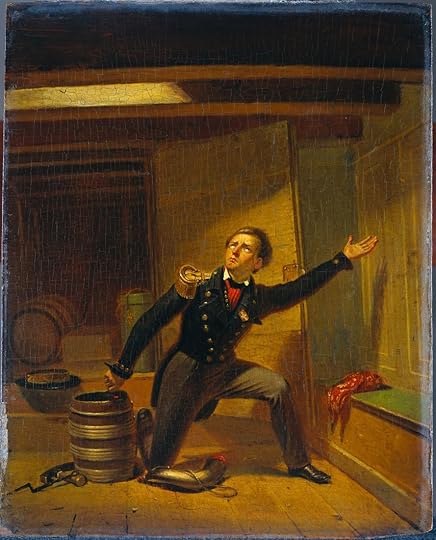

What van Speijk feared could happen, does happen- the mob storms the gunboat,

the ship’s boy knows what’s coming and jumps overboard. van Speijk himself goes below

The crunch came on February 5th 1831. Caught in a north-west gale, and with a dragging anchor, van Speijk’s gunboat was thrown up on the shore. A Belgian mob surged on board. What followed was the stuff of legend, the more so since few survived to tell a coherent story. Unable to prevent the vessel’s capture, van Speijk went below and with the reported words of “Ik ga liever de lucht in” (I’d prefer to be blown up) he either fired his pistol or dropped his cigar into a barrel of gunpowder.

“Ik ga liever de lucht in!” and van Speijk shoots into the keg of gunpowder

The resulting explosion wrecked the gunboat and killed van Speijk himself and 27 of his crew of 30 as well as an unknown number of Belgians. Since there were only two survivors, one of whom was a boy who, seeing what was intended, had jumped overboard before the explosion, it is not quite sure how van Speijk’s final words were recorded, or indeed if he ever spoke them.

The destruction of Gunboat Number 2, Antwerp in the background

The latest van Speijk

Van Speijk was immediately hailed as a national hero in the Netherlands, the admiration being led by King William himself, who within a week of his death issued an order that there should always be a ship called van Speijk in the Royal Netherlands Navy. This order has been honoured ever since and the current van Speijk, the eighth, is a Karel Doorman-class frigate launched in 1995. Van Speijk’s remains were buried with pomp in Amsterdam with the King present and his life was thereafter the subject of poems, paintings and even inspirational nineteenth-century versions of comic strips.

And the expression “Ik ga liever de lucht in!” entered the Dutch language and even today is used as a term of exasperated refusal.

Start the 12-volume Dawlish Chronicles series of novels with the chronologically earliest: Britannia’s Innocent It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

It’s 1864. War has come to Denmark – brought on by political folly and waged against the mighty forces of Prussia and Austria. With no allies to turn to, a determined Danish commander leads his men northward, refusing to call it a retreat. Pursued by Austrian cavalry through snow, sleet, and mud, their resolve is tested with every punishing mile.

Across the Atlantic, another conflict rages. The American Civil War spills onto the world’s oceans as Confederate raiders strike Union shipping as far away as the East Indies. Now a powerful new ironclad, nearing completion in a British shipyard, threatens to shift the balance—if she can ever be armed. The Union wants her destroyed. The Confederacy wants her unleashed. And Denmark may yet gain her, if secret bargains can be struck.

Into this maelstrom steps a young Royal Navy officer: Nicholas Dawlish. Newly returned from service in the West Indies, Dawlish volunteers to aid Denmark, drawn by duty, adventure – and divided loyalties. Thrust into the brutal realities of siege, bombardment, and bitter fighting on the cold waters of the North Sea, he must learn fast if he is to survive.

In later years, Dawlish will be known as a shrewd and battle-hardened commander. But in 1864 he is still untested—an innocent on the brink of war.

The first novel in the acclaimed Dawlish Chronicles series, Britannia’s Innocent begins the saga of a man whose fate will be shaped by courage, conflict, and the tides of history.

For more details, click below: For amazon.com For amazon.ca For amazon.co.uk For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post “I’d prefer to be blown up!” – van Speijk at Antwerp, 1831 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

August 6, 2025

Thomas Luny: Great Naval Artist, Heroic Soul

Thomas Luny: Great Naval Artist, Heroic Soul

Thomas Luny: Great Naval Artist, Heroic SoulIn this article I want to write of a hero, Thomas Luny, who is known as a great naval painter – but other details of whose life are less familiar. Two sorts of courage move me. The first is the sort of bravery that is called upon for a finite period, for minutes, hours, days or even on occasion months, and which demands a disregard for personal safety and a willingness to risk life and limb of the sake of others. The second is “fortitude”, the determination to endure suffering, privation or personal misfortune over an indefinite period, and still not be defeated. The latter is expressed, unforgettably, by the crippled poet William Ernest Henley (1849–1903):

These words come to mind – for reasons that will emerge later in this article – when looking at the career of the marine artist, Thomas Luny (1759–1837). His work is familiar to many of us, even if we don’t know his name, if we have seen illustration of the Age of Fighting Sail. At a time before photography, Luny was one of the artists who had defined our perception of how that age looked and felt.

The Bombardment of Algiers, August 1816, by Thomas Luny

Self-portrait in youth

Luny was born in Cornwall – most appropriately in the famed “Year of Victories” when British forces were triumphant on land and sea In Europe and North America. He came to London at the age of eleven and was apprenticed to the marine painter Francis Holman (1729–1784), who was himself son of a master mariner. This apprenticeship proved significant in determining the course of Luny’s career since Holman’s younger brother, Captain John Holman (1733–1816), maintained the family shipping business. The relationship between the brothers appears to have been a close one. Francis would therefore have been in close contact with the maritime world and this showed in the wealth of detail and accuracy in his later work. Talented as Holman was however, it is partly because of his mentorship of the more illustrious Luny that he is now most remembered.

“A small shipyard on the Thames” by Francis Holman, Luny’s mentor

(National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PD-ART-LIFE-70

By 1780 Thomas Luny had shown sufficient talent that he was exhibiting marine paintings in the Royal Academy, and indeed he continued to do so up to 1802. From 1783 Luny lived in London’s Leadenhall Street, and here became acquainted with a dealer and framer of paintings called Merle who subsequently promoted Luny’s work very successfully.

The 18-year old Luny hits his stride: “Shipping off Dover” – 1777

Thomas Luny’s home address in Leadenhall Street was also significant in that it was where the British East India Company had its headquarters. It was from “John Company” that Luny was to receive many commissions for paintings and portraits. This relationship had non-monetary benefits also for, on occasions, Thomas Luny seems to have been invited as a guest on Company ships on special occasions and voyages. This probably accounts for the great detail and realistic look of many of his sketches of locations such as Naples, Gibraltar, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Between 1793 and 1800 Thomas Luny appears to have gone to sea with a purser’s warrant and served with Captain, afterwards Admiral, George Tobin (1768–1838).

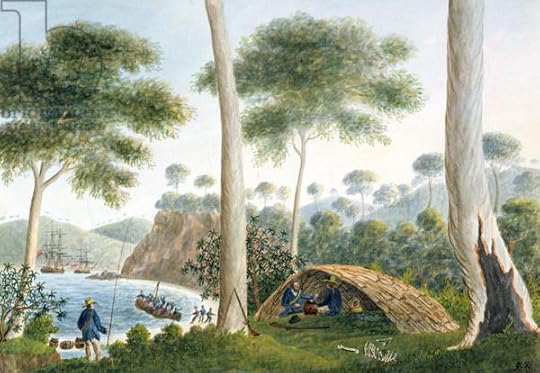

George Tobin: Aboriginal hut on Bruny Island, Tasmania, 1792 (Mitchell Library)

One suspects that under Captain Tobin the purser’s duties may have been nominal – a legal fiction for getting Luny to sea. One has the distinct impression that the relationship between Luny and Tobin was very similar to the fictional one between Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin, two men of very different characters and aptitudes who nevertheless valued their friendship dearly. One would like to think so. Tobin was himself an artist and the watercolours he made when he sailed with Captain Bligh to Van Diemen’s Land in 1790-1792 are in the Mitchell Library, Sydney (see example above). In this, once again, one sees the Aubrey-Maturin similarity, since in both cases the dissimilar personalities have one shared passion and talent, in the once case for music and in the other for art.

Engraving of Luny’s “The Glorious First of June”

Whether Thomas Luny was present at the battle of the ” Glorious First of June” in 1794 is uncertain, but he painted, among many other marine subjects, several of the incidents of this battle and of the subsequent bringing home of the prizes. It is equally uncertain whether he was on hand for the Battle of the Nile 1798, which he also illustrated spectacularly.

The Battle of the Nile, August 1st 1798, at 10 p.m.

Painted by Luny in 1835, over three decades after he was incapacitated

Up to 1800 Luny’s life had not only been dramatic and adventurous, but also triumphant in professional terms. It was now however that great misfortune fell upon him when he was attacked by rheumatoid of arthritis. It deprived him initially of the use of his feet, and later, cruelly for an artist, it closed his hands so firmly that he could not move his fingers. In this state he moved in 1807 to Teignmouth in Devon, apparently to be his friend Captain Tobin, who had also retired there.

Thomas Luny: “Boarding the ferry at Teignmouth” – painted 1821

(With acknowledgements to Wikigallery)

It was now that Luny’s fortitude and greatness of spirit asserted itself. Despite all his disabilities he continued to paint, receiving numerous commissions from ex-mariners and others, with the same success as before. He was to continue working up to 1835, chair-bound and only able to clutch his brush between hands which could not hold it in his fingers. For delicate manipulation he is said to have held the brush in his mouth. This had no obvious impact on the quality or pace of his artistic work. In fact, of his lifetime oeuvre of over 3,000 works, over 2,200 were produced between his disablement in 1807 and his death. His style is unmistakable.

Thomas Luny: “A frigate of the Royal Navy leaving Cork Harbour 1830”

Specimens of Thomas Luny’s work are exhibited at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, London, in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, and at The Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia. If you read this, and if you’re lucky enough to see any of Luny’s work, pay a silent tribute to the memory not only of a great artist, but of a heroic spirit.

Britannia’s Innocent The chronologically earliest of the 12-Volume (so far) Dawlish Chronicles series1864: Europe in turmoil. Two wars. One young man tested to the limit.

While the American Civil War rages across continents and oceans, another conflict erupts closer to home. Denmark, isolated and defiant, faces invasion by the combined might of Prussia and Austria. As defeat looms, a determined Danish commander refuses to retreat, leading his weary troops north through blizzard, mud, and blood.

While the American Civil War rages across continents and oceans, another conflict erupts closer to home. Denmark, isolated and defiant, faces invasion by the combined might of Prussia and Austria. As defeat looms, a determined Danish commander refuses to retreat, leading his weary troops north through blizzard, mud, and blood.

Across the North Sea, Britain watches uneasily. Her heir is married to a Danish princess, and sympathies stir beneath official neutrality. When a modern Confederate ironclad nears completion in a British yard, a daring covert deal is struck: Denmark may lease her, if she can be armed — and if she can survive the Union’s attempts to destroy her.

Into this cauldron steps Nicholas Dawlish (1845-1918), newly returned from Royal Navy service in the West Indies. Young and ambitious, he volunteers to fight for Denmark. What follows is a brutal education — in siege and skirmish, naval bombardment. And in betrayal, and the grey ethics of war.

Long he rose to be an admiral, Dawlish was an innocent. But not for long . . .

Available in Paperback and in Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle unlimited read at no extra charge. Click below for purchase details.

For USA For UK & Ireland For Canada For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post Thomas Luny: Great Naval Artist, Heroic Soul appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 31, 2025

The Royal Navy’s last major ship-of-the-line action

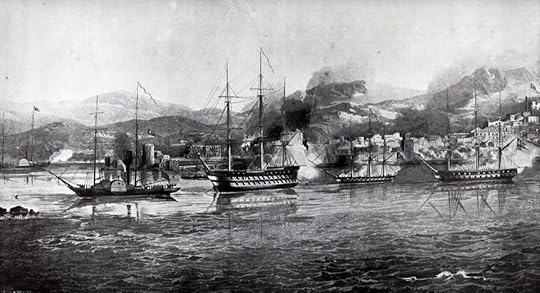

Though steam propulsion was first applied to warships, on a small scale, in the late 1830s, it was to take over half a century more before sail was finally abandoned by the world’s navies. The process was paralleled with the replacement of wood by metal – initially iron and later steel – for construction. 1840 was however to see the last major action by the Royal Navy in which a sailing wooden line-of-battle ship, of a type almost identical to those which fought under Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805, was to play the leading role. It was however supported by small steamers. The scene was to be Sidon the coast of Lebanon, then regarded as part of the Ottoman – and temporarily Egyptian – province of Syria, in 1840.

Bombardment of Sidon, September 27th 1840

Present conflicts in the Middle East are only the latest in a long series of struggles for power which go back to the dawn of history. In the last two centuries however these clashes have arisen from the weakening and eventual demise of the Ottoman Empire – a development which still has massive influence on events today.

In the early nineteenth century the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul ruled, in theory at least, a vast empire that stretched from Libya in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from what is now Romania and Serbia in the north to the Sudan in the south. A weak central government, all too often bedevilled by corruption and by difficulties in communication over such a vast area, made it easy for local governors to set themselves up as semi-independent rulers.

The massacre of the Mamluks in the

citadel of Cairo, March 1811

The most notable of these ambitious local governors was Muhammad Ali (1769 – 1849), an Albanian general in the Ottoman Army who was appointed governor of Egypt in 1805. His first step in consolidating his power was to eliminate the Mamluks, the warrior caste which had ruled Egypt, under the Sultan, for over 600 years. He did so in 1811 by inviting the Mamluk leaders to a celebration at the Cairo Citadel. Once gathered there, they were surrounded by Muhammad Ali’s troops and slaughtered. He was now de-facto ruler of Egypt and the Sudan. By the 1820s he was arguably as powerful as the Sultan himself.

[image error]

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali’s only setback in this period stemmed from Intervention in the Greek War of Liberation, which began in 1821. The Sultan’s army proved incapable of putting down the revolt and Muhammad Ali was offered the island of Crete in exchange for his support. Over 16,000 Egyptian soldiers, supported by the modern fleet that was being built up in Egypt, went to Greece under the command of Muhammad Ali’s son, Ibrahim Pasha. This led to intervention on behalf of the Greeks by Britain, France and Russia, culminating in the battle of Navarino in 1827 in which the entire Egyptian navy was sunk by an allied fleet, under the command of Admiral Edward Codrington (1770–1851). This was the last major fleet action under sail and, most appropriately, Codrington had been one of Nelson’s “Band of Brothers”. He had joined the Royal Navy in 1783 and had been present at the battles of the Glorious First of June (1796) and Trafalgar (1805), commanding HMS Orion at the latter.

The destruction of the Egyptian fleet at Navarino, October 1827

In compensation for the loss of his fleet, Muhammad Ali asked the Sultan for Syria – a term which then included modern Lebanon and Israel in addition to the country now known as Syria. The Sultan refused and in the early 1830s Muhammad Ali, successfully seized Syria, and much of Arabia, in a campaign that was notable for Ottoman ineptitude.

A mixture of medieval despot and enthusiast for modernisation, Muhammad Ali now concentrated on building Egypt into a powerful and independent European-style state. No opposition was allowed and the process was often brutal. He set out to streamline the economy, train a professional bureaucracy, and build a modern military machine. He not only encouraged agriculture – the global demand for cotton was insatiable – and he built an industrial base, primarily focused on weapons production. By the end of the 1830s, Egypt’s war industries had constructed nine 100-gun warships and were turning out 1,600 muskets a month.

Muhammed Ali demanding construction of modern warships

In 1839, the Ottoman Empire, now ruled by the young Sultan Abdülmecid, attempted to retake Syria. Ottoman ground forces were once again routed. In June 1840, the entire Ottoman navy defected to Muhammed Ali. The French Government, with aspirations to regain control of the area which Napoleon had won briefly, then lost, decided to offer full support to Muhammad Ali. This would involve a major strategic reorientation in the Middle East and indeed held the seeds of a general European conflict (WW1 seven decades too soon!). Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia decided that preservation of the Ottoman Empire was paramount and decided to intervene jointly to prevent total collapse.

Western negotiations with Muhammed Ali 1839

By the “Convention of London”, signed in July 1840, these powers offered Muhammad Ali and his heirs permanent control over Egypt, the Sudan and the “Eyalet of Acre” (an area roughly corresponding to modern Israel and Southern Lebanon) as nominal territories of the Ottoman Empire. Muhammad Ali hesitated, believing that he could rely on French support. This was a fatal miscalculation.

British and Austrian naval forces moved into action in September 1840. Faced with the possibility that confrontation with Britain could mean war, France, pragmatically but ingloriously, changed sides the following month, aligning itself with the other European nations against Muhammad Ali. By this time the Royal Navy and the Austrian Navy had already been in action. Alexandria, to where the defecting Ottoman fleet had withdrawn, was blockaded and forces were concentrated on Sidon and Beirut on the Lebanese coast.

HMS Gorgon

HMS Gorgon

At Sidon the withdrawal of the Egyptian garrison was demanded by the British commander, Commodore Charles Napier (1786-1860). A refusal bought bombardment by Napier’s squadron on September 27th. This force was led by the HMS Thunderer, a two-deck 84-gun second rate ship of the line, launched in 1831 but not significantly different to ships of the Napoleonic era. In support was a relic of that period, the 18-gun brig-sloop HMS Wasp, launched in 1812. Significantly however, these two sailing vessels were supported by four steam vessels, Cyclops, Gorgon, Stromboli and Hydra. Further support was provided by the Austrian sailing frigate Guerrierea of 48-guns and the Ottoman corvette Gulsefide.

The contemporary illustration below – by A Lieutenant J.F.Warre RN (of whom I have no further details) – shows the Thunderer at the centre and the Ottoman and Austrian vessels to the right. The paddle steamers to the left could be any of the four such British vessels present.

Bombardment of Sidon, September 27th 1840

The bombardment seems to have driven the Egyptian defenders from their positions and, in the best Royal Navy tradition, a naval brigade landed under Napier’s personal command suppressed any remaining opposition and captured many prisoners. Beirut was subjected to similar treatment but did not yield until October 9th, after Napier had again landed and had conducted a vigorous and successful land campaign.

[image error] Paddle sloop HMS Phoenix in action at Acre

Sir Charles Napier

Acre (just north of Haifa) was the remaining Egyptian stronghold on the Eastern Mediterranean coast. British and Austrian forces, attacked again, led by HMS Thunderer. Following a bombardment on November 3rd 1840 a small landing party of Austrian, British and Ottoman troops, led personally by the Austrian fleet commander, Archduke Friedrich, took the citadel after the Egyptian garrison had fled.

Muhammad Ali now accepted the inevitable and assented to the terms of the Convention of London on November 27th. He renounced his claims over Crete and Western Arabia and agreed to hand back the Ottoman fleet and to downsize his remaining naval forces and standing army. In return, he and his descendants would enjoy hereditary rule over Egypt and the Sudan. The dynasty he established was to rule Egypt – not always gloriously or successfully – until its final representative, King Farouk, was ousted in the 1952 Revolution.

HMS Thunderer was to serve on towards the dawn of a new age of naval technology and 1863 was fitted with iron plates for trials of new armour-piercing guns. She survived as a storage hulk until 1901, initially renamed Comet, and subsequently Nettle, one of the last links with the Age of Fighting Sail.

Britannia’s Reach Read it as a stand-alone novel or as part of the Dawlish Chronicles series 1880: Deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers, crammed with troops, horses, and artillery, pushes slowly up a broad river — driven by ambition, vengeance, and cold profit. Its mission: to crush the forces of a messianic leader who seized a once-thriving commercial empire from British hands during a bloody revolution. Now, British investors are determined to reclaim their losses—at any cost.

1880: Deep in the heart of South America, a flotilla of paddle steamers, crammed with troops, horses, and artillery, pushes slowly up a broad river — driven by ambition, vengeance, and cold profit. Its mission: to crush the forces of a messianic leader who seized a once-thriving commercial empire from British hands during a bloody revolution. Now, British investors are determined to reclaim their losses—at any cost.

At the heart of the expedition is Commander Nicholas Dawlish, a rising star in the Royal Navy, but now on temporary leave of absence, and acting essentially as a mercenary.

But as the campaign descends into savage fighting on land and river alike, progress slows, atrocities mount, and victory slips from reach. Faced with a bitter stalemate, Dawlish must confront a harrowing moral dilemma—one that could define his future, or destroy it.

A tale of ruthless ambition, unforgiving terrain, and the price of honour.

Available in Paperback and in Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle unlimited read at no extra charge. Click below for purchase details.For USA For UK & Ireland For Canada For Australia & New ZealandThe Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …Click on image below for detailsThe post The Royal Navy’s last major ship-of-the-line action appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

July 24, 2025

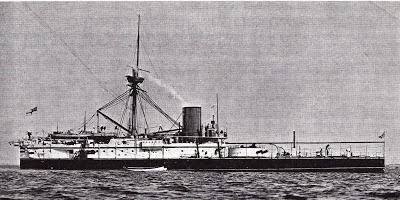

HMS Hero – the Player’s “Navy Cut” battleship

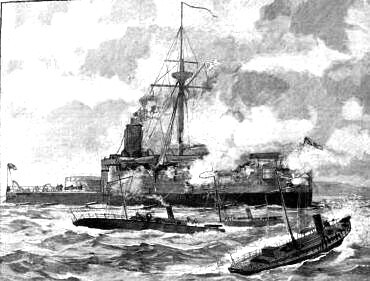

HMS Hero and her sister, HMS Conqueror, both commissioned in the late 1880s, were described by Dr.Oscar Parkes, the ultimate authority on British battleships, as “two of the most useless turret ships ever built for the Navy”. Despite this damning evaluation, which was supported by many officers during her lifetime, HMS Hero was to achieve a bizarre degree of fame for over another century. The reason for this had little to do with the unfortunate vessel herself and depended on her being named on the cap-band of the seaman featured in the logo of Player’s Navy Cut cigarettes. In late Victorian uniform, the sailor’s head and torso were seen though a life-belt, with two poorly-defined ironclads in the background, that on the right possibly HMS Hero herself.

The cigarettes were launched by the tobacco company John Player Ltd. in the same period as the ship herself. These were years in which there public pride and interest in the Navy was growing – and would continue to do so up the Great War – as evidenced by the popularity of HMS Pinafore and of sailor suits for children. In the early years the sailor in the logo was apparently sometimes bearded, sometimes clean-shaven, but the bearded version seems to have been standardised in 1907 and has continued almost up to our own day. The name “Navy Cut” originated from a sailors’ practice of binding a mixture of tobacco leaves and leaving them to mature under pressure. A slice of this slab came to be known as a “cut”.

Commercially successful and widely recognised as the cigarette brand was, the ship associated with it was to have a much less stellar career. Both HMS Hero and her sister HMS Conqueror were designed in a period of transition, when there were conflicting views on how line-battleships should be armed and armoured. Large calibre breech-loading rifles were coming into their own, breakthroughs in metallurgy were providing much more effective armour, and compound steam engines were promising greater power and fuel-efficacy. Smaller-calibre quick-firing guns, up to 6”, were proving their potential and there was intense debate as to whether the ram was still a viable weapon in action. Allied to this was the question of tactics – no fleet action had been fought with such ships and theories abounded as to how to employ them. The problem was not the availability of technology but rather how disparate available elements were to be integrated into a single concept which would function efficiently in line with an agreed tactical doctrine.

HMS Hero in glorious Victorian livery – by William F. Mitchell (1845–1914)

The controversies of the 1880s were to be resolved in the next decade with the appearance of the Royal Sovereign class which was to set the line of evolution that almost all battleships would thereafter follow, not only in Britain but elsewhere as well. Getting to this point however involved pursuing number of technical and tactical dead ends, the most notable being perhaps HMS Hero and HMS Conqueror. Their basic design premise was that they would combine large calibre guns (two 12”) in a single rotating turret, strength enough for ramming, a substantial secondary armament (four 6” quick-firers), six above-water 14” torpedo tubes, a plethora of small-calibre weapons, heavy armour and, for good measure, a small torpedo-boat carried on deck which could be lowered to launch its own separate attacks.

HMS Conqueror soon after completion

These naval camels (“horses designed by a committee”) tried to do everything and succeeded in nothing. With 6200 tons on a 270 ft. hull the freeboard was inevitably low (9.5 feet) and seakeeping was going to abysmally poor. Parkes writes “When HMS Benbow was rolling 5° in a moderate swell the Conqueror worked through 18° to 20°. In the 1890 manoeuvres she actually rolled 35° one way so that the cutter stored at bridge level was washed from its davits” Service on these ships in such conditions must have been terrifying and living conditions little better since “the bows were usually buried in a cataract of foam and the mess deck on the main deck forward became uninhabitable in anything of a seaway due to leaky forecastle fittings.”

The offensive capability was equally inadequate. The 12” weapons in the turret could not be fired on a bearing of more than 45° to either side of the central axis due to blast damage to the superstructure. This was underlined in a report on the 1889 manoeuvres which stated that “What they would have become after the big guns had been fired over them a few times is at present left to the imagination.”