Antoine Vanner's Blog, page 5

March 20, 2024

HMS Flora 1780: the Carronade arrives

HMS Flora 1780: the Carronade’s arrival

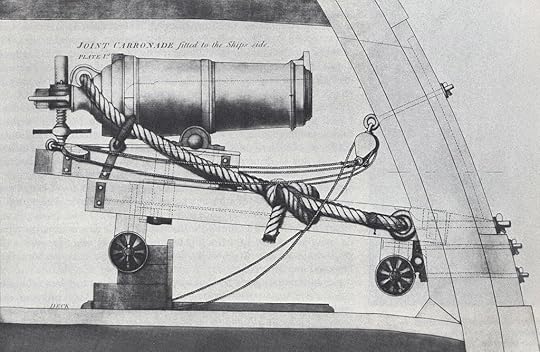

HMS Flora 1780: the Carronade’s arrivalIn sea battles from the 1780s to the end of the Napoleonic Wars a decisive factor was often the use of the carronade. Few of these guns were carried on any one ship, and they were not counted in a ship’s rated number of guns so that, in practice, the actual number of weapons carried might be significantly higher than the rating by which a ship was classed, such as a “74” or a “50”.

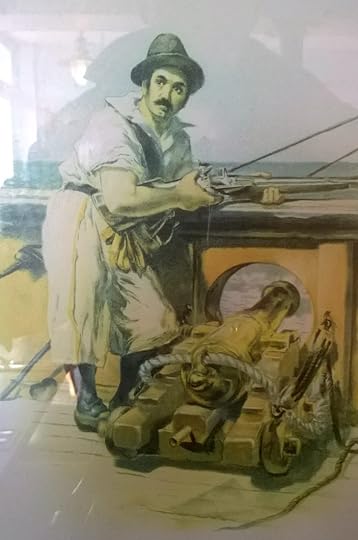

Carronade on slide mounting

The word “carronade” was an early, perhaps earliest, example of a trade-name becoming the accepted term for an entire class of products, in this case a short smoothbore cast iron cannon. It took its name from the original manufacturer, the Carron Company, which had an ironworks in Falkirk, in Scotland. The short barrel indicated that it was a short-range weapon, powerful against ships but even more so against personnel in close actions. A carronade weighed a quarter as much and used a quarter to a third of the gunpowder-charge for a long gun firing the same size of roundshot. The lower recoil forces meant that slider mountings, rather trucks, could be employed. The light weight of the carronade made it especially attractive for mounting at higher levels – and important factor when an enemy’s deck should be cleared by grapeshot before boarding. They could also provide a very powerful punch for a small vessel such as a gunboat or sloop. Though the basic concept remained unchanged, carronades were manufactured for a huge range, from 6 to 42-pounders, and 68-pounder weapons not unknown.

Antoine Vanner with 24-pdr Carronade

When introduced into the Royal Navy for trial in 1779, many captains had reported most unfavourably upon it, owing to its short range and tendency to overheat when fired rapidly. The comment on short range was justified for, devastating as a carronade could be in action, its weakness was its short range. The analogy may be a sub-machine gun which, if used at close quarters, can be murderous, but is useless against an enemy armed with a sniper rifle who prefers to stay out of its range and to count on his accuracy. Only by luring the sniper closer can the man armed with the sub-machine gun make use of its ability to unleash a devastating volume of fire. In the case of sailing warships encountering each other at sea the presence of carronades might not be immediately obvious and in many cases were to provide a very unpleasant surprise as the ships closed. The first occasion on which carronades were used in action, when the Royal Navy’s 36-gun frigate Flora encountered the French 36-gun frigate Nymphe, was a good example.

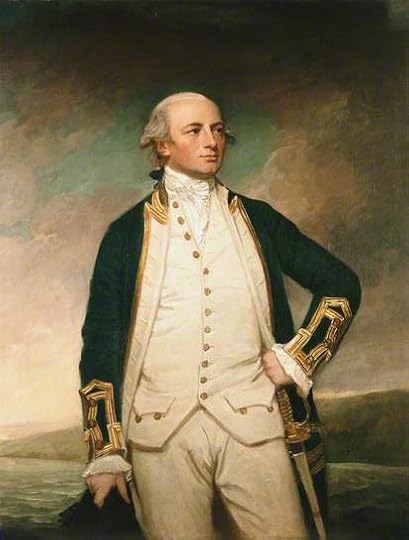

Peere Williams by George Romilly

In August 1780 the Flora was under the command of Captain William Peere Williams (1742 – 1832). He was to be one of the officers whose entire life spanned the classic Age of Fighting Sail and who lived on to see the dawn of steam-power. As a junior officer he had served under Hawke at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759 during the Seven Years’ War. By the time of the American War of Independence he had achieved command, first the frigate HMS Venus, in American waters, and subsequently as the first captain of HMS Flora with the Channel Fleet. She was a new ship, commissioned in 1780 and her performance in action later that year indicates that Peere Williams was relentless in training his crew to a high standard of gunnery.

The Flora’s rating as “36 guns” was deceptive though she did indeed carry that number of long guns – twenty-six long 18-pounders, and ten long 9-pounders – she also carried six of the new 18-pounder carronades, giving her a 333-pound broadside weight. On the afternoon of 10 August 1780 she was patrolling off Brest, a monotonous but war-winning duty that was familiar to the crews of hundreds of Royal Navy vessels for seven decades from the 1750s. The weather was hazy but two vessels were sighted some four miles distant. The smaller vessel made off but the larger stood her ground, obviously willing to accept battle. She was the French frigate Nymphe, of the French Royal Navy, her Captain the Chevalier de Runrain. She nominally superior to the Flora in everything but armament. She was the bigger ship by about 70 tons (868 to 737, important as regards enduring damage), sailed faster, and had the larger crew. She carried twenty-six long 12-pounders, and six long 6 – pounders, giving a broadside weight of only 174 pounds, just over half of the Flora’s.

Flora’s log summarised very clearly what happened in the resulting action:

“At 4.30 P.M. saw a ship and a cutter in the S.W. quarter, standing to the northward under easy sail. Made sail and stood for them, at which they tacked and stood towards the shore for some minutes, and then brought to, having French colours flying. We made the private signal to them, which we found they did not understand by the ship hoisting a blue flag at the ensign staff. We cleared for action, hauled down the signals of recognisance and hoisted our St George’s ensign, hauled up the fore-sail, bunted the main-sail and top-gallant-sai1, still running down on her to windward.”

The HMS Flora – Nymphe action by Dominic Serres (1722 – 1793)

HMS Flora’s log continued:

“At 5.15, being then about two cables, length distant from her, received her larboard broadside. We ran within one cable’s length of her and then began the action, which continued very hot on both sides till 6.15, when we had our wheel and tiller-rope shot away and fell alongside of her with our spare anchor hooking her fore-shrouds. They then attempted to board us, but were repulsed with great loss, we still keeping up a warm fire of great guns and musketry. At 6.80 boarded her, cleared her decks, and burnt their colours for them.”

The action was a punishing, straightforward fight to a finish, with little attempt on either side at finesse or manoeuvre. The total French loss was 60 killed and 71 severely wounded. Many of these casualties resulted from the ineffectual attempt to board and the havoc unleashed on them by six 18-pounder carronades mounted on the poop and quarter-deck of the Flora. In the heat of the action one of these weapons was manned only the boatswain and a single boy. The French captain was killed by a musket ball just before the two ships touched, the second-in-command fell on the deck of the Flora at the head of his boarders and the first lieutenant fell between the two hulls and was crushed to death. Almost every other French officer was wounded. The report by the Nymphe’s dangerously wounded second lieutenant, the Sieur de Taillard – written in Falmouth, to where the captured frigate was taken – stated that “I do not think it possible to speak too highly of the cool and collected courage shown by all the officers. We were twice on fire, and there was an explosion of cartridges”. The Flora lost fewer dead – nine in total – but sustained the same number of wounded as the Nymphe and her total casualties amounted to approximately one third of her crew.

Nymphe in British service as HMS Nymphe , capturing Résistance and Constance in company with HMS San Fiorenzo , 9 March 1797. Painting by Nicholas Pocock (1740 – 1821)

HMS Flora’s later career was useful rather than spectacular. While still commanded by Peere Williams she participated in the second naval relief of the Siege of Gibraltar in 1781 and thereafter her most notable contribution was support of Britain’s Egyptian campaign in 1801. She was wrecked in 1808. The Nymphe’s career in the Royal Navy – she retained her name after the change of ownership – was to be much more spectacular and we shall meet her again in a later war.

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post HMS Flora 1780: the Carronade arrives appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 14, 2024

Merchantman vs. a French Privateer, 1811

Throughout the Age of Fighting Sail merchant shipping – from small coastal craft to large vessels engaged in interoceanic trade – were at the mercy of privateers. These were privately owned vessels issued with “letters of marque” that authorised them to attack and capture enemy shipping. If captured they would be treated as prisoners of war but their payment was dependent on the value of prizes they captured. This financial incentive meant that privateers – of which the French and American were the most active and successful – were of necessity daring and ruthless. Since Britain had the largest merchant fleet in the world it was to the most tempting target, especially as, in the days before radio, there was no ability to transmit a distress call, even when friendly vessels might have been in the vicinity. Though convoys, escorted by Royal Navy vessels, played an important role from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, Britain’s global commitments meant that available naval assets were always stretched. As a consequence, many merchantmen sailed independently and were reliant on their own ability – and willingness – to defend themselves. One such vessel was the Three Sisters, which fought off a heavily armed French privateer in 1811.

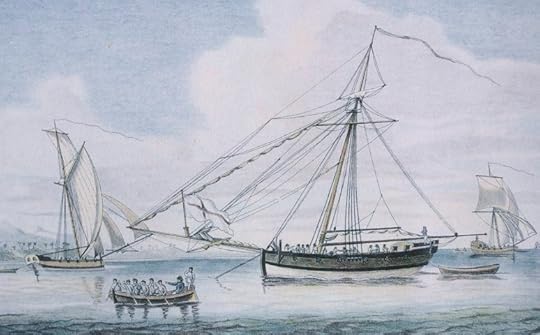

A trading brig – the Three Sisters, at largest, might have looked like this.

Painting by William Huggins (1820 – 1880)

I came across the story of the Three Sisters in a book entitled “Privateers and Privateering” by a Commander Edward Phillips Statham, R.N. and published in 1910. Rather than describe the action himself, Stataham very wisely decided to copy, in toto, the short report made by the captain of the Three Sisters, George Thompson, to the vessel’s owners on September 18th, 1811. I am repeating it myself below as I regard it as a small masterpiece of succinct and descriptive prose which, in an understated way, conveys the bloody-minded determination of Thompson and his crew to see off any attacker.

Thompson’s report does not specify the type of vessel that the Three Sisters was – no need to, as the owners already knew! I am therefore indebted to Mr. Ark Hodge, who contacted my immediately after this article appeared, for further information. He advised that, according to the Lloyds Register for 1811, the Three Sisters was owned by St Barbe & Co. and trading between London and Corfu. She was described as a British-built brig of 137 tons and twelve feet in draught, plank-sheathed, furnished with a berth-deck, and armed with four guns. The French privateer was possibly larger, judging by the heavy armament she carried. It is notable that the action took place in British coastal waters and that the French privateer involved was prepared to operate there. One is reminded of small German U-Boats in action along England’s southern coast in World War One.

A Royal Navy armed schooner – the French privateer that the Three Sisters encountered might have been similar . Painting by Thomas Butterworth (1768-1842)

Here is Thompson’s report:

“I have to acquaint you with a desperate engagement I have had with a French privateer, Le Fevre, mounting 10 guns—six long sixes, and four 12-pound carronades—with swivels and small arms, manned with 58 men, out from Brest fourteen days, in which time she captured the Friends schooner, from Lisbon, belonging to Plymouth, and a large sloop from Scilly, with codfish and sundries, for Falmouth. On the 11th, at nine p.m., we observed her on the larboard bow; we were then steering N.N.E. about ten leagues from Scilly, and nearly calm.

“I immediately set my royals, fore steering-sails, and made all clear for action. At two a.m., when all my endeavours to escape were useless, she being within musket-shot, I addressed my crew, and represented the hardships they would undergo as prisoners, and the honour and happiness of being with their wives and families. This had the desired effect, and I immediately ordered the action to commence, and endeavoured to keep a good offing; but which he prevented by running alongside, and immediately attempted to board, with a machine I never before observed, which was three long ladders, with points at the end, that served to grapple us to them. They made three desperate attempts, with about twelve men at each ladder, but were received with such a determination that they were all driven back with great slaughter, and formed a heap for the others to ascend with greater facility.

The traditional mental image of boarding. In the case of the Three Sisters the fighting would have been no less furious but the smart uniforms would have been lacking!

“Finding us so desperate, they immediately, on their last charge failing, knocked off their ladders, one of which they were unable to unhook from our side, and left it with me, and sheered off; but, I am sorry to say, without my being able to injure them, as they had shot away part of my rudder before they boarded me, and I am sorry to say wounded several of my masts and yards, for it seemed to be their aim to carry away some of my masts, but which, happily, they did not effect. The most painful part of my narrative is the loss of two men and a boy killed, and four wounded; but the wounded are doing well. Our whole crew amounted, officers and men, to twenty-six men and four boys, and deserve the highest applause that can be bestowed upon them. I arrived off here this afternoon, and, as it is fine weather, I have no doubt of reaching London in safety, as I have but little damage in my hull.”

End of Thompson’s report

One wonders what became of this magnificent man in later life – he deserved wealth, happiness and the thanks of his country. In the two world wars, other merchant captains were to be Thompson’s spiritual heirs. They showed the same qualities of courage and resolution in bringing their ships through even worse ordeals. Without them, the Battle of the Atlantic and other desperate campaigns could never have been won. We owe them.

The Dawlish Chronicles series:Start with Britannia’s InnocentWhat links war in Denmark in 1864 with the American Civil War?For more details, click below:For amazon.com For amazon.co.uk For amazon.ca For amazon.com.au The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

The Dawlish Chronicles – now up to twelve volumes, and counting …

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

Available in paperback and Kindle. Subscribers to Kindle Unlimited read all at no extra charge. Click on the banner above for details of the individual books.Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Merchantman vs. a French Privateer, 1811 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 2, 2024

Rome: An alternate world

For me, Antoine Vanner, one of the unexpected pleasures of becoming an author was encountering other writers and, though writing in different genres, forging bonds. Some twelve years ago I was welcomed by a group of about a dozen authors who met every month in a public house, “The Zetland Arms”, in South Kensington, London, for Saturday lunches. We discussed anything and everything to do with writing and publishing and they were wonderfully enjoyable occasions. We learned a lot from each other. Among the regulars was Alison Morton who, like me, had just published for the first time and she and I have been level pegging ever since, producing on average a book per year. My series is entitled The Dawlish Chronicles, naval and espionage adventures set in the later Victorian Era.

Alison at Claudium Virunum, a Roman city in the province of Noricum, today’s Austria. Here is where the new city of Roma Nova was established in Alison’s alternate universe

Alison’s brilliant Roma Nova series could not be more different to mine. It’s set in a convincing “alternate universe” and takes as its point of departure from actual history the idea that a remnant of the Roman Empire has survived into modern times. In novel after novel – ten so far, Alison sets her hard-boiled thriller plots in a convincing and internally consistent universe. Whether set in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries or, in the case of her new novel, EXSILIUM, set in the late fourth century, the action is credible since the Roma Nova universe has the same social structures and technologies of the same periods as in the actual world we live in. The characters have the values of their eras – especially important in the books set in the fourth century, such that they are real people of their time and not just twenty-first century people in re-enactors’ costumes. Were we, or our distant forebears, to be translated into that Roma Nova universe, we would function much as we do in our own – which often means “Not Well – but we’ll win through somehow!”

What I find especially interesting in this latest novel, EXSILIUM, is the picture it presents of a society that has much in common with the West today. It’s unsure of what it stands for anymore, has no widely supported vision of where it’s going and lacks the will to face, or even recognise, existential challenges. The unitary Roman Empire is by now split into the Western and Eastern Empires. In itself, this is an intelligent response to the challenges of administration over a vast area – but the success of the twin empires is dependent on cooperation, the more so since the barbarian tribes are pressing on the northern and north-eastern borders. Instead of cooperation however, there are constant plots, coups and civil wars between aspirants to the purple and, at times. open conflict between the Western and Eastern Empires.

The structure of governance in the Western Empire persists – the emperor, the imperial civil service, the armies (now dependent on recruits from barbarian tribes) and the senate – but all are hollow. The challenge of respectful coexistence of Christianity, the new state religion, with the remnants of traditional Pagan belief is being mishandled as the previously persecuted increasingly become persecutors in their turn. The writing is on the wall – this Western Empire is a doomed enterprise and nobody sees it, much less admit it. The Goths will be sacking Rome some two decades after the setting of EXSILIUM and within a century the Western Roman Empire will have disappeared, replaced by separate kingdoms established by barbarian tribes. The Dark Ages will soon be engulfing most of Europe and though the Eastern Empire will survive as a powerful entity for two centuries more, it too will then start its slow and irreversible decline towards belated extinction in 1453.

Alison conveys very convincingly how people of education, wealth and dwindling power are forced to recognise that the society that they know and love no longer has a place for them. Decisions, extremely hard decisions, must be taken – whether to remain and somehow survive a future that looks ominous for them, if not deadly, or to cut their losses and strike out for a new beginning whose success cannot be guaranteed. With a reluctance with which we can identify, the individual characters in EXSILIUM come to accept that, in reality, “There is no alternative.”

And accepting that alternative is the foundation of the seventeen-century epic of Roma Nova that Alison chronicles.

Highly recommended – Antoine Vanner

Click on any of the images below for details of all Alison’s books

Alison’s Bio

Alison Morton writes award-winning thrillers featuring tough but compassionate heroines. Her ten-book Roma Nova series is set in an imaginary European country where a remnant of the Roman Empire has survived into the 21st century and is ruled by women who face conspiracy, revolution and heartache but use a sharp line in dialogue. The latest, EXSILIUM, plunges us back to the late 4th century, to the very foundation of Roma Nova.

She blends her fascination for Ancient Rome with six years’ military service and a life of reading crime, historical and thriller fiction. On the way, she collected a BA in modern languages and an MA in history.

Alison now lives in Poitou in France, the home of Mélisende, the heroine of her two contemporary thrillers, Double Identity and Double Pursuit.

Social media links

Connect with Alison on her thriller site: https://alison-morton.com

Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/AlisonMortonAuthor

X/Twitter: https://twitter.com/alison_morton @alison_morton

Alison’s writing blog: https://alisonmortonauthor.com

Alison’s Amazon page: https://Author.to/AlisonMortonAmazon

Newsletter sign-up: https://www.alison-morton.com/newsletter/

The post Rome: An alternate world appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

March 1, 2024

Sailing Craft against U-Boats in World War 1

Sailing Craft versus U-Boats in World War 1

Sailing Craft versus U-Boats in World War 1Though the “Age of Fighting Sail” ended around 1840 as regards major warships, small sailing craft were to play a very important role in World War 1 in Britain’s battle against Germany’s U-Boats. One such heroine craft was the Lowestoft fishing smack Telesia, which was conscripted into naval service. A hero of this campaign was Skipper Thomas Crisp VC (1876 – 1917). The following may give some flavour of what such warfare involved for such men, and such vessels.

Typical small sailing coaster

The mental image that most of us have of sinkings of British merchant shipping by German submarines, U-Boats, in World War 1 is by means of torpedoes. This was to a great extent a last resort however. Only limited numbers of torpedoes could be carried in the small submarines of the time and as such were to be reserved for large targets. In this period a major portion of all seaborne freight was carried in small vessels, many of them still sailing craft. Until Britain’s introduction the convoy system in 1917 all merchant ships sailed individually. Encountered alone on an empty sea, and almost certainly without radio (an innovation confined to warships and larger merchantmen) a small ship could be approached with impunity by a surfaced U-Boat. Gunfire could then be used to sink her or, even more economically, she could be boarded so that explosive charges could be placed below the waterline. The names of the myriad of humble fishing and trading craft sunk by U-Boats are largely forgotten today, in contrast to major losses such as the Lusitania that live on in the public memory.

For much of the war Germany refrained from unrestricted submarine warfare and internationally accepted “Prize Rules” were applied, these dating, scarcely modified, from the Age of Fighting Sail. These stated that passenger vessels could not be sunk, that crews of merchant ships must be placed in safety before their ships were sunk (lifeboats were not considered a place of safety unless close to land) and only warships and merchant ships that were a threat to the attacker might be sunk without warning. Germany’s surface raiders – notably the SMS Emden – applied these rules scrupulously and so too did the U-Boats for a major portion of the war. Departure from these rules was ultimately to trigger American entry.

Anti-submarine technology was also in its infancy. Only limited progress had been made on detection methods – Sonar, or in British parlance, Asdic, would only become effective after the end of hostilities – and without them the use of the primitive depth charges of the time was likely to be ineffective. The most likely method of destroying a U-Boat was to catch her on the surface and to finish her by gunfire or ramming. The challenge was therefore to lure the U-Boat to the surface.

Typical Q-Ship crew. Note civilian garb

Observance of the “Prize Rules” was to make U-Boats vulnerable to being trapped by apparently innocent-looking merchant or fishing craft which carried concealed weaponry. These would sail under merchant colours and a naval ensign was to be run up only when the U-Boat was sufficiently close to allow fire to be directed on her. The crews wore civilian clothes and in many cases a “panic party” would drop a boat and row frantically away from the ship as the surfaced U-Boat approached so as to allay suspicion. A hidden crew would however remain on board and, once the U-Boat was in point-blank range, screens and other disguises would be dropped to allow the guns to be brought to bear. These vessels were known to the British as “Q-ships”, taking their initial letter from Queenstown (now Cobh), the port in the South of Ireland were most were based.

[image error]

U-Boat vs. Q-Ship

The Q-ship would typically cruise in areas where U-Boats were believed to operate. She would often be packed with light wood or cork so that even if torpedoed she would remain afloat, encouraging the U-Boat to surface and sink her with a deck gun. The Q-Ship’s appearance might be changed frequently, by painting or by erection of dummy funnels and deckhouses, to deter suspicion of the same merchant vessel being seen too frequently in the same area. Crews were made up of a combination of serving Royal Navy personnel and reservists. A total of 193 Q-ships were commissioned during the war, of which 38 were sunk. 51 of the total were fishing vessels, of which 11 were lost.

The typical Q-Ship – and “typical” is a loose term in this case, as no two were identical – was a small tramp steamer, sometimes very heavily armed and ideal for operation in the Atlantic shipping lanes to the south and west of Britain and Ireland where larger U-Boats would operate. The challenge was different in the North Sea where fishing craft, from sailing smacks as well as powered vessels, provided important food supplies. From mid-1915 small, 90-ft long, UB and UC-class German coastal U-Boats, were active in this area, typically carrying only two torpedoes and eight mines, plus a deck-gun for surface use. Besides being suited to mining British inshore waters they represented a significant threat to fishing craft – an example being three smacks from Lowestoft being sunk, after boarding by U-Boat personnel, in two days in early June 1915.

HMS Lightning (1895), Janus-Class destroyer, victim of mines laid off

the Thames Estuary by a UC-class boat in 1915

The response was to arm four fishing craft as Q-ships. The first success was by the unpowered sailing smack Inverlyon which was armed only with a single 3 pounder gun. Approached on the surface by the German UB-4 near Great Yarmouth on August 15th 1915, the Inverlyon pumped nine rounds into her at close range, sinking her with the loss of all hands. It is impressive to record that, as the UB-4 sunk, the Inverlyon’sfishing skipper, a man named Phillips, dived in to attempt to rescue, unsuccessfully, a German crewman in the water. Further such battles were to follow, including a second, though inconclusive, action involving the Inverlyon. Despite this, the German threat was to continue.

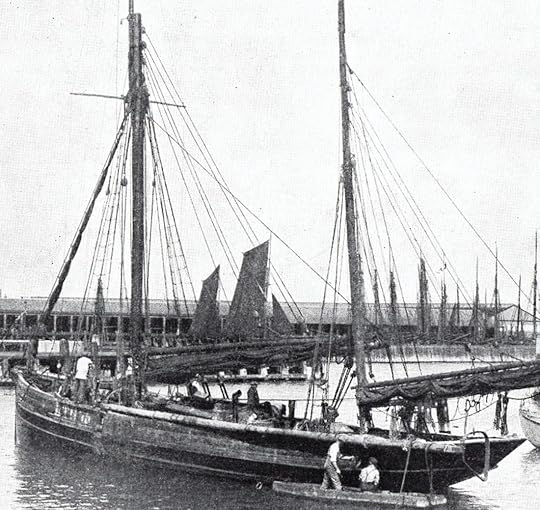

Telesia – humble fishing smack

The relentless pace of duty for these ships can be illustrated by reference to the armed Lowestoft smack Telesia. No less than six fishing craft had been boarded and sunk by explosive charges early in March 1916 and the Telesia’s crew was inevitably alert. On March 23rd 1916 the Telesia was simulating trawling some 35 miles E.E. of Lowestoft. A U-Boat approached at 1330 hrs, made a cautious inspection, and came within fifty feet of her bows. The Telesia’s crew kept their nerve and maintained the pretence. For some inexplicable reason the U-Boat commander submerged to periscope depth and disappeared, returning an hour later for a further look. The submarine again disappeared but came back at 1630 hrs but remained submerged, though identified by her periscope. From 300 yards a torpedo was launched – a case of a sledgehammer deployed against a gnat – but it missed the Telesia’s bow by some four feet. Her skipper, Wharton, ordered the vessel’s three-pounder to open fire, lashing fifteen rounds at the periscope before the U-Boat disappeared.

An hour later the U-Boat returned and she fired a second torpedo, which also missed, this time by forty feet, but surfacing immediately. As her conning tower was revealed the Telesia again opened fire, apparently scoring two non-fatal hits. The U-Boat now had had enough and she crash-dived so quickly that her propeller was revealed. She appeared to have headed back to her base on the Belgian coast.

The aftermath of the action provided a salutary lesson. The wind fell. The Telesia was becalmed and she would have been a sitting target had she been taken under gunfire. It was decided thereafter that all Q-smacks would be thereafter be equipped with auxiliary oil engines.

UC Class boat similar to that involved in the Cheero action 23rd April 1916

Telesia was again in action off the East Anglian coast a month later, on April 23rd, with her name changed to Hobbyhawk. She was now operating in company with a similar smack, the Cheero. In place of normal trawl nets these craft were towing 600 yards of nets with mines attached and this reduced their speed to 3 knots. They were now also equipped with rudimentary hydrophones, listening devices that could pick up the characteristic “whirring” sound of a submerged U-Boat running on electric motors. At 1900 hrs just such a sound was detected and both crews knew that a U-Boat was now stalking them. The tension must have been almost unbearable. 45 minutes passed, and then the Cheero’s towing wire suddenly went taut, then eased, then went taut again as if an enmeshed vessel below was fighting to free herself. An underwater explosion followed, throwing up a 20 ft plume and moments later there was a second, larger, explosion which left traces of oil on the surface. The hydrophones confirmed that the whirring had ceased but confirmation of the kill could only come when the net was hauled in. One of the net-mines had exploded and pieces of steel were entangled in the mesh. It was concluded that the second explosion resulted from detonation of the cargo of mines carried by the submarine herself. It later emerged that this vessel was UC-3.

The Telesia/Hobbyhawk was to see yet more action less than a month later, on May 13th when she had a hot but indecisive battle with another U-Boat. Other such vessels were to have equally dramatic encounters, all the more dangerous as the Germans became familiar with the tactics involved and as larger U-Boats replaced the UB and UC vessels. These were more heavily-armed, typically with a 4.1-in deck gun that outranged anything the smacks could carry.

Thomas Crisp VC – indomitable

In retrospect, it seems irresponsible to have kept the smacks in service and a particularly high price was to be paid in 1917 by the smacks Nelson and Ethel and Milly (a single vessel). On August 15th these craft were taken under fire by a U-Boat. Fire was returned – hopelessly in view of the range differences – and the Nelson was overwhelmed. Thomas Crisp, her skipper, was seriously wounded but he ordered resistance to continue as the vessel settled. With only five rounds remaining he ordered “Abandon Ship”, pigeons to be released with information on the position (a pigeon being the only form of communication available, as no radio was carried) and his son Tom to take charge of the ship’s boat. Crisp refused to be moved as he was too badly wounded – indeed in the message he dictated for the pigeons he stated “Skipper Killed”. He went down with his ship. The Ethel and Millie had also went down fighting and her seven-man crew were hauled aboard the German submarine, where the Nelson survivors last saw them standing in line being addressed by a German officer. They were never seen again, and controversy exists regarding their disappearance. Opinion at the time was that they were murdered and dumped overboard by the German crew or abandoned at sea without supplies, but neither theory can be substantiated. Another possibility was that they were taken prisoner aboard the boat and killed when the submarine was herself sunk.

The Nelson’s boat and her survivors were picked up by a British ship. Skipper Thomas Crisp was awarded a well-deserved posthumous Victoria Cross and his son received a Distinguished Service Medal.

The Telesia – again under her own name – still in service in the 1930s

What has been described here is only a small part of the work undertaken by these tiny vessels and their indomitable crews. The courage and tenacity demanded of these men was of the highest degree and in pure economic terms the kills they achieved must have been the cheapest ever recorded in anti-submarine warfare. The smacks which survived the war returned to their normal peacetime pursuits. One of the last of these splendid vessels was the Telesia herself, which was still in service in 1935 when she was chosen to represent her home-port of Lowestoft at the Silver Jubilee Naval Review at Spithead.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamIf you are a subscriber to Kindle Unlimited you can read all twelve volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post Sailing Craft against U-Boats in World War 1 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 16, 2024

HMS Venerable, 1804: Cool Heads in Crisis

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars locked Britain and France into almost twenty-two years of continuous warfare from 1793 and conflict at sea was a critical part of this. What is surprising however is how few ships were actually destroyed in combat. Whether in large fleet actions or in “single ship” duels, wooden ships tended to survive very heavy damage and could often be repaired sufficiently at sea to get them to port. When captured, such ships were often to get a new lease of life in the victor’s navy. Little use was made of explosive projectiles and though solid shot could inflict severe structural injury above the water-line, it seldom caused outright sinking. The relatively few ships that were lost due to combat mainly succumbed to magazine explosion, or to burning.

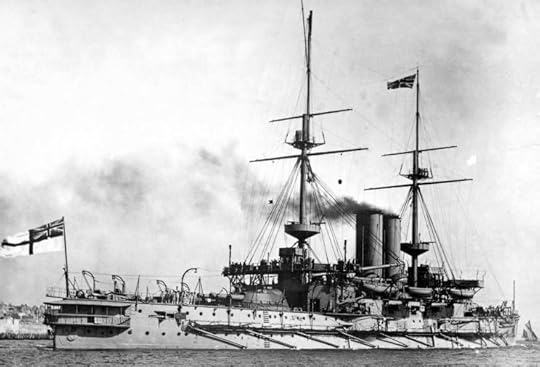

The Battle of Camperdown, 1797 – one of the few fleet actions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Eras

Painting by Thomas Whitcombe (1763 – 1824 ) – Venerable at centre engaging Vrijheid on left

The greatest threat to a wooden warship’s survival came from stormy weather, especially if it were to be cast on a lee shore, where it could be battered to matchwood. One such loss occurred in 1804 when a Royal Navy “74”, HMS Venerable, encountered disaster. Built in 1784, HMS Venerable had played an important role at the Battle of Camperdown in 1797 as Admiral Duncan’s flagship and assisting in the capture of the Dutch admiral’s flagship Vrijheid.

Much of HMS Venerable’s service – like that of so many other 74s – consisted of participation in the blockade of the French coast – gruelling work, often in atrocious weather conditions, that continued day-in, day-out for months on end. This was never more the case than in 1804-05 when fears of a French invasion were at their height and the Channel Fleet, under Admiral William Cornwallis (1744 –1819), represented Britain’s first line of defence.

On 24th of November, 1804, the Cornwallis’s fleet, including HMS Venerable, lay in the large anchorage at Torbay, in Devon. Deteriorating weather conditions, and an onshore gale, caused orders to be given to put to sea. HMS Venerable was under the command of Captain John Hunter (1737 –1821), whose portrait is shown on the left. Hunter who had not only had an active naval career but had also served from 1795 to 1800 as the second governor of New South Wales, Australia. There he encouraged exploration and his name is commemorated in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. As governor, Hunter combatted serious abuses of power by the military authorities. In this period a contemporary described Hunter as “devoid of stiff pride, most accomplished in his profession, and, to sum up all, a worthy man.” He is also notable for having sent back to Britain the first known sketch and pelt of a platypus (of which Dr. Stephen Maturin would certainly have approved).

On 24th of November, 1804, the Cornwallis’s fleet, including HMS Venerable, lay in the large anchorage at Torbay, in Devon. Deteriorating weather conditions, and an onshore gale, caused orders to be given to put to sea. HMS Venerable was under the command of Captain John Hunter (1737 –1821), whose portrait is shown on the left. Hunter who had not only had an active naval career but had also served from 1795 to 1800 as the second governor of New South Wales, Australia. There he encouraged exploration and his name is commemorated in the Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. As governor, Hunter combatted serious abuses of power by the military authorities. In this period a contemporary described Hunter as “devoid of stiff pride, most accomplished in his profession, and, to sum up all, a worthy man.” He is also notable for having sent back to Britain the first known sketch and pelt of a platypus (of which Dr. Stephen Maturin would certainly have approved).

Darkness was falling as HMS Venerable began raising anchor. The operation went awry however, one seaman being thrown into the sea. The alarm was given and orders were given to drop a cutter to rescue him. In the process one of the falls suddenly let go and the cutter plunged down into the water and filled. A midshipman and two seamen were drowned but a second cutter managed to rescue others in the water, including the man who had originally fallen overboard.

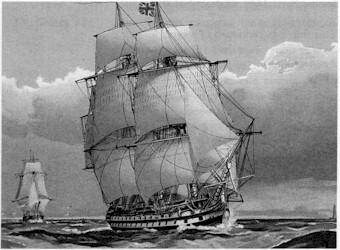

HMS Mars, a classic “74”. HMS Venerable was generally similar

While this drama was taking place, HMS Venerable was falling away before the gale and found it impossible to exit the bay. She was driven onshore at Paington, practically at the mid-point of the bay’s semi-circular arc. She was clearly stuck immovably and it could only be a matter of time before she broke up. Orders were given to cut away the masts, in the hopes of their falling between the ship and the shore and so providing an escape route. This proved impossible however as, in grounding, the hull had been canted over away from the land. Captain Hunter remained in full control however – “with undaunted fortitude he continued to animate the crew with hope, and encouraged them to acts of further perseverance, with the same calmness and self-possession as if he were simply conducting the ordinary duties of his ship. From the moment the ship struck, not the least alteration took place in his looks, words, or manner; and everything that the most able and experienced seaman could suggest was done, but in vain.”

HMS Thunderer – another “74” of the era

HMS Venerable’s plight had not gone unnoticed. Two other 74s, HMS Goliath and HMS Impetueux, approached as closely as they dared in the circumstances and a cutter, HMS Frisk, stood in nearer still. Frisk was requested to anchor as close to HMS Venerable as she could so as to receive survivors, carried to her by pulling boats from Goliath and Impetueux.

Discipline prevailed as HMS Venerable’s crew were transferred to the boats and Captain Hunter, and his officers, declared that they would not leave the ship until the last seaman had been taken off. (It should be noted that at this time Hunter was sixty-seven years old, but this did nothing to decrease his resolution). The sea conditions were now so bad that the rescue boats could only come in under HMS Venerable’s stern, from which men were lowered by ropes. These efforts continued through darkness, raging seas and driving sleet. HMS Venerable was now practically on her beam ends, such that Hunter and his officers were now directing operations while standing – or rather holding on – on the outer side of the hull. All this time, HMS Venerable was pounding on the shore and likely to break up at any moment. It was close enough to the land – some twenty yards – to shout to helpers on shore and a line was eventually secured between them and the ship. Several men attempt to haul themselves to land along it but were plucked away to their deaths by the surf.

HMS Venerable grounded – note hull canted out seawards and conditions in which the rescue boats are operating

Painting by Robert Dodd (1748 – 1816)

By five o’clock on the morning of the 25th – still dark and with the weather deteriorating yet further – only seventeen seamen remained on the ship with the officers. The sea was breaking over them and the fore part of the ship was wholly submerged. Only then did Captain Hunter order the final evacuation, his officers and himself to follow the men. One by one they dropped into the waiting boats – whose crews had by now been in action in the most dangerous conditions imaginable for more than six hours. Ultimately all, including Hunter himself, were brought across to HMS Impetueux. This was none too soon – shortly afterwards, HMS Venerable broke apart amidships and the part they had been huddled on capsized. Within sixteen hours of first striking, little remained of the ship but driftwood.

Only a handful of HMS Venerable’s crew were lost. Everybody involved on the Navy side came well out of this disaster – Hunter and his officers, his crew and the men who manned the Frisk and the boats of Goliath and Impetueux. Discipline and training had proved the keys to survival in the most desperate conditions, and the rescue – and the steadiness of officers and seamen alike – speak volumes about morale. Hunter himself was known as a humane and efficient commander and it is likely that this played no small part in his crew’s behaviour in extremis. Less impressive as the role played, or not played, by local people on shore. Not a single civilian boat put out from the fishing communities nearby and, according to a 19th Century commentator, “to add to this disgraceful conduct, the cowardly wretches were observed, when daylight broke, plundering everything of value as it floated ashore.”

It is pleasing to note that Hunter, when court-martialled for the loss of his ship, as he had to be, was fully acquitted. He promoted to rear admiral two years later and to Vice Admiral in 1810., and then to vice admiral on 31 July 1810, though he never hoisted his flag at sea. He died in 1821.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamSubscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read all twelve volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the photo-block below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post HMS Venerable, 1804: Cool Heads in Crisis appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 8, 2024

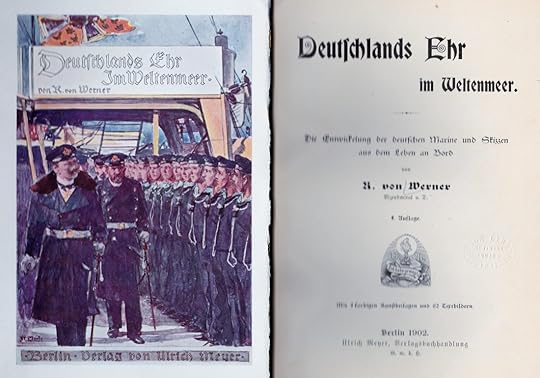

Life in the Imperial German Navy, 1902

Some time ago I stumbled on German publication of 1902 entitled “Germany’s Honour on the World’s Oceans” (Deutschlands Ehr im Weltenmeer) by a Vice-Admiral von Werner. The sub-title is “The development of the German Navy and sketches of life on board.” The illustrations, not less than the text, are fascinating and they’re worth recording below.

The timing of the book is significant – the German Navy was just starting the expansion which in just over a decade was to bring it from second-class status to the second most powerful one in the world. Enthusiasm for the Navy and naval affairs was high and was fostered by the government, Kaiser Wilhelm II seeing naval strength as essential for his personal prestige no less than for the nation. This is reflected in the book’s frontispiece – see above – in which the ridiculously mustachioed kaiser is seen inspecting naval personnel. Prior to this time the German Empire, building on traditions of the Prussian military, and its crushing defeat of France in 1870, had been primarily a land power with only a limited naval tradition. This was to change and the book seems to be part of the shift in cultural mindset. It is notable that it is printed in German Gothic font which is quite difficult to read at first (I hadn’t read in it for almost 50 years!), but which one gets quickly used to.

Painting entitled “Squadron at Sea”

Leading ship is a reconstructed central-battery ironclad of the 1874 “Kaiser” class

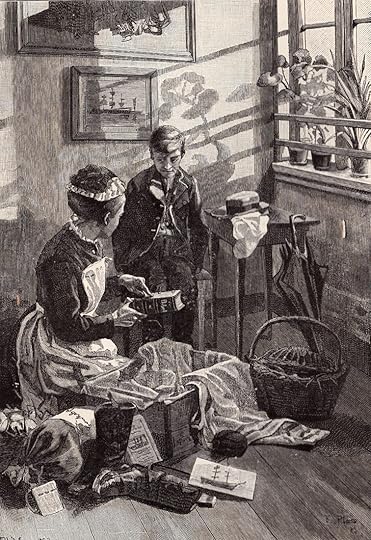

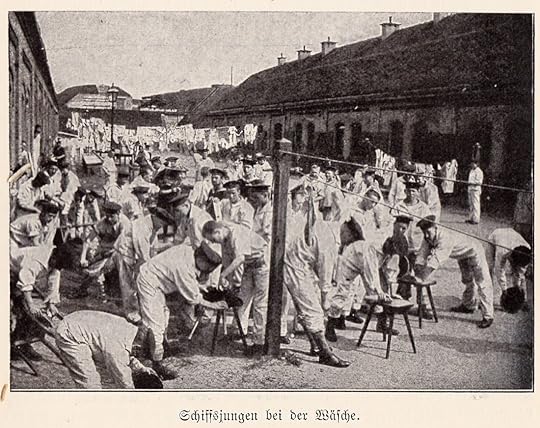

Much of book’s focus is on presenting life in the navy as attractive for young men, either as officers or seamen. The text is illustrated not just by photographs of ships, but with drawings – many not just idealised, but indeed sentimentalised – of life on board. There are some very attractive stylised capital letters at the start of each chapter, all incorporating a sketch. I have scanned many of the illustrations and have included them below. They tell as much about aspiration as about reality and as such give a unique insight to the thinking of the time.

A first step towards a naval career – a worried cadet, aged about 13, prepares to

leave home. Interesting that it is a maid, rather than a family member, who helps him pack

Fun in the gunroom – cadets enjoying themselves on board a training vessel

Boy recruits for the lower deck – washing from basins

A nap on deck for an exhausted recruit- hard to imagine this lasting for long!

Note blackened soles of feet!

Instruction by an older seaman

Sunday religious service conduc ted by a Lutheran chaplain

Young sailors dancing hornpipes – not sure if doing so voluntarily or under orders!

Catching a shark – presumably not an everyday occurrence!

Christmas overseas – note tropical uniforms and tree in background

The training ship SMS Nixe of 1883 was described in “Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905” as “a hopeless anachronism, with her full rig and wood and copper-sheathed bottom, but useful as a school ship, though a bad seaboat and awkward under sail” She served in this capacity to 1901.

Training ship SMS Gneisenau (of Bismarck class of iron flush-decked corvettes), commissioned 1880 but wrecked in Malaga harbour, Spain, during a storm in 1900. The captain and forty others died.

There is a terrible poignancy in these images. The young men shown would have been middle-ranking officers or NCOs by outbreak of war in 1914. Superb professionals by that time, they would have seen action in surface forces or in submarines. Many would not survive, even though they might otherwise have reasonably expected live on into the 1960s, could perhaps have watched the moon-landing on television with their grandchildren. Their futures were denied them through the stupidity and arrogance of lesser men. Kaiser Wilhelm and his counterparts in other European nations carried a heavy burden of guilt to their graves.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamSubscribers to Kindle Unlimited can read all twelve volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post Life in the Imperial German Navy, 1902 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

February 1, 2024

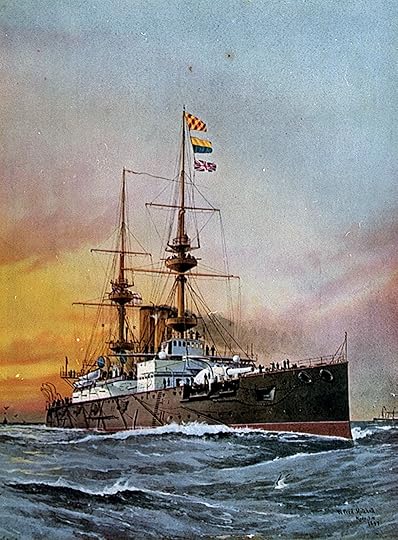

The Twilight of the Pre-Dreadnoughts, 1915

At the start of World War I all major navies had significant numbers of pre-dreadnought battleships which, though in many cases only eight or ten years old, had been rendered wholly obsolete by the commissioning of HMS Dreadnought in 1905. This, the first turbine-driven, all-big gun, battleship, mounted ten 12” guns, compared with the almost universal armament of four 12-inch guns for the average pre-dreadnought, and set the model for all subsequent capital ships. The painting on the left, by William Frederick Mitchell, shows HMS Prince George, commissioned in 1896, is typical of the type and is seen here in glorious “Victorian Livery”. By the outbreak of war in 1914 large numbers of “dreadnoughts” – the name had already come to symbolise a type – were in service in the larger navies. Putting obsolete pre-dreadnoughts into a battle-line which would have to face much more powerfully-armed dreadnoughts was likely to be little short of suicidal.

At the start of World War I all major navies had significant numbers of pre-dreadnought battleships which, though in many cases only eight or ten years old, had been rendered wholly obsolete by the commissioning of HMS Dreadnought in 1905. This, the first turbine-driven, all-big gun, battleship, mounted ten 12” guns, compared with the almost universal armament of four 12-inch guns for the average pre-dreadnought, and set the model for all subsequent capital ships. The painting on the left, by William Frederick Mitchell, shows HMS Prince George, commissioned in 1896, is typical of the type and is seen here in glorious “Victorian Livery”. By the outbreak of war in 1914 large numbers of “dreadnoughts” – the name had already come to symbolise a type – were in service in the larger navies. Putting obsolete pre-dreadnoughts into a battle-line which would have to face much more powerfully-armed dreadnoughts was likely to be little short of suicidal.

In 1914 the Royal Navy still has 39 pre-dreadnoughts while the French Navy had 26 (including several more heavily-armed “semi-dreadnoughts”). It was recognised that though they were unsuited to battle-fleet service they might still prove of value in secondary duties such as shore bombardment. In such cases low speed would be less of a concern and each ship would be capable of bringing four 12” weapons into play, plus large numbers of lower-calibre weapons.

It was the availability of large numbers of such pre-dreadnoughts that contributed to the decision to attempt forcing a passage through the Turkish-held Dardanelles Strait in 1915. Success in establishing a sea-route to the Russian Black Sea coast would allow supply of weapons and munitions to often-underequipped Russian land forces – and indeed some have argued that had this been achieved Russia might not have collapsed as it did in 1916/17 and that the Bolshevik Revolution might not have occurred or have been successful if it still did. There also appears to have been some thinking that, in view of the large number of obsolete pre-dreadnoughts available, significant losses could be tolerated to achieve success. This argument ignored the fact that these ships carried large crews and that the sinking of any one would mean a devastatingly high – and unacceptable – death tolls.

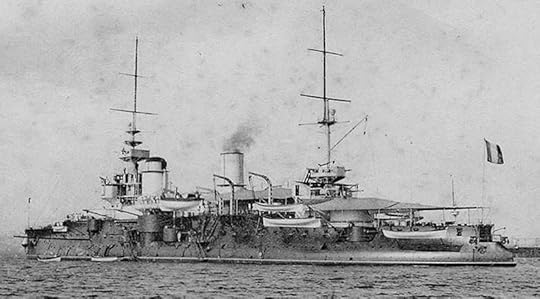

The Bouvet in French peacetime livery, black hull, light grey upperworks

The purely naval attempt to force the Dardanelles on 18th March 1915 saw no less than sixteen British and French pre-dreadnoughts, plus the new 15” dreadnought Queen Elizabeth and the lightly armoured battle-cruiser Inflexible advance up a strait that narrowed from four miles to one in some ten miles. The result was a disaster. Under fire from Turkish shore-batteries, and heading into upswept minefields, two British pre-dreadnoughts (Ocean and Irresistible) and one French one (Bouvet) were lost in little more than an hour. The Inflexible – which should not have been there, as speed rather than armour was intended as her protection – survived after hitting a mine. The loss of the Bouvet was particularly spectacular, blowing up and sinking in less than two minutes and taking 660 men with her. The impracticability of the scheme was finally realised and the massive naval force was withdrawn. The decision was now taken to land troops to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula that flanked the Dardanelles and poorly-planned and inadequately-supplied landings were made at several points on April 25th 1916. None of the forces landed reached their first-day objectives. The Turks managed to hold, to flood in reinforcements and to establish a trench-deadlock no less intractable than that on the Western Front. The eight-month agony of the Gallipoli campaign had begun, ending only with full evacuation of Allied forces in early 1916.

The role of the pre-dreadnoughts after the failure of March 18th was to be shore-bombardment in support of the landings, and thereafter of the forces onshore. Over-optimistic assumptions were made about the ability of naval guns to take-out pin-point targets – which was what the troops onshore needed – and the results were wholly incommensurate with the risks run by the ships involved. Three further British pre-dreadnoughts were to be lost before the decision was taken to withdraw them from the beaches. The ability of the enemy to strike back with either surface or submarine forces was wholly under-estimated, and indeed the arrival of a German U-Boat, the U-21, came as a very unpleasant surprise. HMS Triumph and HMS Majestic were to fall victims to her torpedoes on May 25th and May 27th respectively.

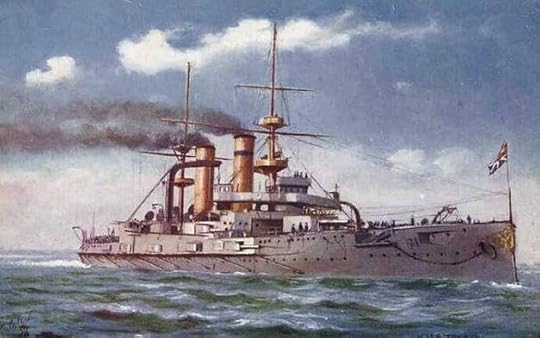

HMS Triumph – originally built, with her sister Swiftsure, for Chile in 1903 but taken over by the Royal Navy. Smaller, and with lighter main armament than the average British pre-dreadnought

The first of the losses off the Gallipoli beaches was however due to surface attack. Ever since the automotive torpedo had come into service in the late 1870s the possibility of torpedo-craft penetrating anchorages under cover of night was recognised as a major threat. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 had indeed begun with exactly such an attack by the Japanese even before war was declared. It is therefore surprising that lack of alertness – perhaps even complacency – may have characterised the sinking of the pre-dreadnought HMS Goliath in the early hours of May 13th 1915.

HMS Goliath

Of the Canopus class, the Goliath was a typical pre-dreadnought. Completed in 1900, of 13,000 tons and 430-feet long, she carried four 12-inch guns, twelve 6-inch and a large number of smaller weapons. She had served off the East African coast earlier in the war but was recalled to participate in the attempt on the Dardanelles. Her crew was over 700. She had provided fire support for the landings on April 25th and continued to do so thereafter, sustaining light damage from Turkish shore batteries. On the night of 12th-13th May she was anchored in Morto Bay, close to Cape Helles, the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula, in company with a similar vessel HMS Cornwallis. Five destroyers ad been assigned to protect them and visibility was low due to fog.

Muavenet-i Milliye on Turkish postcard

Following a period of stagnation, under-investment and a lack-lustre performance in the Balkan Wars 1912-13 the Turkish Navy was in the process of re-equipping in 1914. Britain’s refusal to deliver two dreadnoughts constructed in British yards and already paid for (and taken into British service as HMS Agincourt and HMS Erin) was a contributing factor in Turkey entering WW1 on the German side. Delivery had been taken of other new vessels however, most notably four modern torpedo-boats built by Germany’s Schichau-Werft company . These had originally been ordered for the Imperial German Navy but in 1910 they were sold, before completion, to Turkey. They were impressive vessels, designed only for one purpose, that of attack. Of 765 tons and 243-feet long, their two turbines delivering 17,700 HP, and 26 knots, they carried three 18-inch torpedo tubes as well as two 3-inch and two 2.25-inch guns. It was one of these vessels, the Muâvenet-i Millîye (National Support) that was to be the Goliath’s nemesis.

Ohlay (Right) & Firle (left)

Though the Muâvenet-i Millîye was commanded by Senior Lieutenant Ahmet Saffet Ohkay , a German officer, Lieutenant Rudolph Firle, one of many seconded to the Turkish Navy, was assigned to the vessel to give specialist advice on torpedo attack. Taking advantage of darkness and fog patches the torpedo boat passed through the Turkish minefields in early evening and then anchored under cover of the Turkish-held Gallipoli shore about seven miles north-east of the anchored pre-dreadnoughts. She remained there until shortly after midnight and in the meantime, around 23.30, the searchlights sweeping the anchorage from the British ships were switched off. (Why this was done is one of the mysteries of the entire operation).

The Muâvenet-i-Millîye now crept down along the shore and the Allied destroyers failed to detect her. Only at 0100 hrs were two of these destroyers, HMS Beagle and HMS Bulldog, sighted – but astern – and Goliath was spotted directly ahead. The Turkish vessel’s advance was now noticed and Goliath signalled a request for the night’s password. It was too late. The Muâvenet-i-Millîye was in torpedo-range and she launched three torpedoes. They proved to be equally spaced along the pre-dreadnought’s length – one hit below the bridge, a second below the funnels and the third near the stern. The Goliath capsized and sank almost immediately, so quickly in fact that 570 of her crew of more than 700 were lost, including the captain. The darkness and the fast current running – up to three knots – hampered rescue efforts significantly.

Turkish painting of the attack by Diyarbakirli Tahsin

(Turkish Naval Museum, Istanbul)

In the confusion following the attack the Muâvenet-i-Millîye escaped back safely up the Dardanelles. She returned to a hero’s welcome in Istanbul, with illuminations along the Bosporus in honour of her and her crew, and with the award of medals and decorations. Perhaps the best tribute paid to her and her crew came from General Sir Ian Hamilton, the British Army commander at Gallipoli, who wrote in his diary – “The Turks deserve a medal.”

Triumphant torpedo-crew: Firle is second from right in front of tube

The Goliath’s loss was to have serious consequences within the British Government, leading in turn to the immediate resignation of the First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher (who had conceived the Dreadnought and presided over the Royal Navy’s modernisation) and, shortly later, that of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. Two more pre-dreadnoughts, Triumph and Majestic, were to be sunk in the next fortnight, triggering the decision to withdraw all heavy units. The long, painful journey to final defeat and evacuation was now well advanced.

And the Muavenet-i -Milliye? She was to have an inglorious post-war career as an accommodation hulk until she was scrapped in 1953.

But in her one night of glory she had changed history.

The Dawlish Chronicles series brings historic naval fiction into the Age of Fighting SteamIf you are a subscriber to Kindle Unlimited you can read all twelve volumes at no extra charge.They are also available for purchase as Kindle editions or as stylish 9X6 paperbacks.Click on the banner below to read about the entire series. (Shown here in chronological order, they can also be read as “stand alones”)Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles mailing list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.The post The Twilight of the Pre-Dreadnoughts, 1915 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 25, 2024

Privateer action: the Ellen 1780

Privateers receive little attention in accounts of naval warfare right up to the time when the practice was banned by international Paris Declaration of 1856, which only the United States, among major nations, omitted to sign. Such privately-owned ships were authorised by a “letter of marque” to prey on enemy shipping. Usually small, and lightly armed enough to intimidate and capture merchant shipping, but not to fight warships, they tended to be small fast vessels. In an era before radio and radar, their victims were unable to raise the alarm as to their plight, so preventing them warning other ships in the vicinity of the danger. In the course of the Great Age of Fighting Sail, roughly 1700 to 1815, they were responsible for the capture of thousands, if not tens of thousands, of merchant ships, many of them small coastal traders. These actions that are almost universally forgotten today. In possession of a fast and suitably armed vessel, crewed by experienced seamen, the owner, or sometimes syndicate of owners, of a privateer was well placed to make a handsome profit in wartime. One such ship, the Ellen, captained by a James Borrowdale, was to demonstrate in 1780 just how effective such a ship could be.

Privateers could be small, such as this Baltimore sloop, and generally preyed on vessels of their own size and lightly armed, if at all

Described as “an armed merchantman”, the Ellen, of Bristol, seems to have engaged in trading as well as holding a letter of marque – her privateering was likely to have been on an opportunistic basis as an adjunct to her other business. Armed with eighteen six-pounders, and with a crew of sixty-four, half of them boys and landsmen on their first voyage, she set out in March 1780 for the West Indies. The American War of Independence was underway, with French and Spanish forces allied to the Americans. James Borrowdale had given passage to an army captain, a Captain Blundell of the 79th Regiment who was going out to join his unit in Jamaica and he undertook to train sixteen of the Ellen’s crew to act as marines. This would be an augmentation of the ship’s potency as marines were likely to be valuable in boarding operations, or to pouring down small-arms fire on opponents’ decks.

Small Neopolitan merchantman – typical of the sort of target that privateers might dream of

A month out, on April 16th, the Ellen sighted a vessel to windward, apparently of her own general size, and possibly as well armed. Unwilling to risk a fight, Borrowdale crowded on all his canvas and ran. He did however ready his guns and their crews, while Blundell mustered amateur marines. The stranger gained on the Ellen however, firing a gun as an indication that she should heave to, and ran up the Spanish ensign. Seeing that it was impossible to avoid a fight, Borrowdale shortened sail, and hoisted American colours as a ruse to gain time and to draw the enemy in close before opening fire. Each of his guns had been loaded with as bag of grape-shot as well as solid round-shot — a measure likely to particularly effective against sails and cordage. The guns were to be kept trained on the Spaniard as she neared.

HMS Orestes – a British sloop in revenue service, a vessel of the size and armament ideal for profitable privateering service

When the enemy was within hailing distance Borrowdale hauled down the American colours and ran up the British. This was simultaneous with Ellen’s first broadside and a volley of musket-fire from Blundell’s contingent. The unexpected and vigorous attack appears to caught the Spaniards unprepared – their captain may have been deceived by the false colours up to the last moment and seems not to have made sufficient preparations for action. In the confusion he lost control of his vessel’s handling. She fell off from the wind and passed under the Ellen’s lee, thereby allowing a broadside from that side also to be poured into her. Hit by two broadsides, the Spanish captain decided to run, pursed by the Ellen and slowed by damage aloft. The Ellen now ran alongside and attacked again. This time the Spanish defence was more determined and the two vessels lay yardarm to yardarm, blasting each other for an hour and a half. Both seem to have directed their fire at masts, sails and cordage – indication that they were both intent on taking a prize rather than on wrecking it. Only when his ship had been completely disabled aloft did the Spanish captain strike his colours.

A French brig-of-war, painted by Antoine Roux (1765-1835). The Spanish Santa Anna Gratia would probably have looked similar.

Captain Borrowdale found himself in possession of the Santa Anna Gratia, a regular Spanish Navy sloop-of-war that mounted sixteen six-pounders and several swivel guns. He had a crew of 104, of whom seven were killed and eight wounded. This compared with one killed and three wounded on the Ellen, the low butcher’s bill reflecting both captain’s focus on masts and rigging.

The Ellen proceeded to Port Royal in Jamaica with her prize in company, entering with British colours surmounting the Spanish – one of the few instances of a privateer taking on and vanquishing a regular warship.

s

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

Britain is neutral in this conflict, but large British interests – railway and mining enterprises – are at risk as the war-front edges ever closer. Investors in London are demanding British action to protect their assets.

Sub-Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is serving on the Pacific Station in the gunvessel HMS Sprightly. She, and her resourceful captain, are tasked with taking ‘appropriate’ action to guarantee the safety of these interests. The situation is complex – not only Juarista, French and Imperial Mexican forces but bandit groups, a volunteer Belgian Legion and ex-Confederate mercenaries are involved. And there’s a powerful ironclad, flying Imperial Mexican colours, commanded by an Austrian aristocrat who’s desperate for glory.

Dawlish is plunged into deadly action by land and sea and, with fluency in French and Spanish, he’ll be his captain’s right-hand man in a web of political intrigue, treachery and greed in which a single mistake can end both their careers.

But for Dawlish there’s something worse, a heart-breaking encounter with a figure from his past to whom he’s linked by a solemn promise that he can’t fulfill. What follows will be torment for his emotions and his conscience . . .

Available in Large Paperback and Kindle formats. Kindle Unlimited subscribers can read at no extra charge. Kindle version available for pre-order. Click the marketplaces below for ordering details:United States CanadaUnited Kingdom Australia & New ZealandBelow are the twelve Dawlish Chronicles novels published to date, shown in chronological order. All can be read as “stand-alones”. Click on the covers below for more information. All are available in Paperback or Kindle format and can be read at no extra charge by Kindle Unlimited Subscribers.

Six free short stories are available for download to your Kindle. Access them by registering for the Dawlish Chronicles ma iling list – just click on the banner below. You’ll be kept updated on new books and will receive other free stories at intervals.

The post Privateer action: the Ellen 1780 appeared first on dawlish chronicles.

January 5, 2024

The unlucky French battleship Suffren

Built to be unlucky? The French battleship Suffren

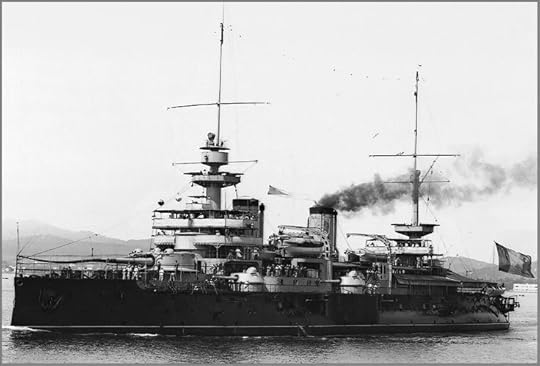

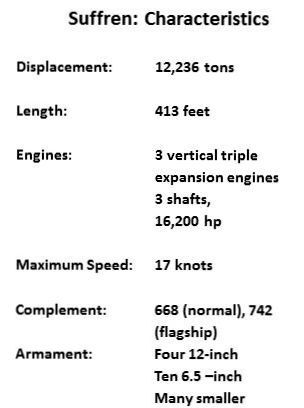

Built to be unlucky? The French battleship SuffrenThe splendidly-expressive Yiddish word “schlemiel” describes a person who is invariably unlucky and whose endeavours are doomed to failure – “so inept even inanimate objects pick on them”. One does come across such unfortunate individuals – who are usually likeable – but in reading naval history one is often struck by the fact that certain ships also have exactly the same characteristic. One such was the French pre-dreadnought battleship Suffren.

The Suffren – a handsome but unlucky ship

Launched in 1899 but not entering into service in 1904 – a year before the construction of HMS Dreadnought made all previous battleships obsolete – the Suffren was “an instant dinosaur”. Not a good start! Shortly before commissioning the Suffren was to participate in a hair raising (or wool-raising) test of new steel armour. A 22-inch thick plate was attached to the side of the forward turret and a succession of 12-inch shells were fired directly at it by the battleship Masséna, which was anchored only 100 yards away. The test was successful: the first three were training shells and merely struck splinters off the armour but the last two, fired with full charges, cracked the plate. The turret and its electrical fire-control system remained operational however. The Naval Minister, Camille Pelletan, who was observing the trials from the Massena, was lucky not to have been killed by a 110-lb splinter that landed next to him. The real heroes of the occasion were however six sheep who had been placed (presumably involuntarily) inside the turret. They were reported to have been unharmed but one does wonder about their subsequent hearing abilities and mental health.

Launched in 1899 but not entering into service in 1904 – a year before the construction of HMS Dreadnought made all previous battleships obsolete – the Suffren was “an instant dinosaur”. Not a good start! Shortly before commissioning the Suffren was to participate in a hair raising (or wool-raising) test of new steel armour. A 22-inch thick plate was attached to the side of the forward turret and a succession of 12-inch shells were fired directly at it by the battleship Masséna, which was anchored only 100 yards away. The test was successful: the first three were training shells and merely struck splinters off the armour but the last two, fired with full charges, cracked the plate. The turret and its electrical fire-control system remained operational however. The Naval Minister, Camille Pelletan, who was observing the trials from the Massena, was lucky not to have been killed by a 110-lb splinter that landed next to him. The real heroes of the occasion were however six sheep who had been placed (presumably involuntarily) inside the turret. They were reported to have been unharmed but one does wonder about their subsequent hearing abilities and mental health.

Henri IV – note the 5.5-inch turret superimposed over the 11-inch rear turret

It might be observed in passing that sheep close to a French naval shipyard in the early 1900s could not rely on life being a bed of roses. The battleship Henri IV, which entered service in 1903 was the first warship to have one turret superimposed over another – in this case a 5.5-inch weapon above the ship’s main after-turret, which carried a single 11-inch weapon. The effects of firing the smaller weapon on the occupants of the turret below were unknown. Doubts were resolved in this case also by herding in a number of sheep, and they too were regarded as having survived the ordeal without ill effects. Since hundreds, if not thousands, of warships were subsequently to employ superimposed turrets, naval architects the world over owe these unfortunate animals a debt of gratitude.

Back to the Suffren and the misfortunes that would bedevil her career. In 1906, during fleet exercises, she rammed the early submarine Bonite . The impact was a glancing one but enough for the frail craft to tear a gash large enough to flood two of Suffren’s compartments – which said a lot about her underwater integrity. The Bonite was even more badly damaged – not surprisingly – but managed to stay afloat by dropping her weighted keel, a feature of her class. There were no casualties on either vessel.

On 12th March 1907 the Suffren was to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. She was in drydock in Toulon close to the pre-dreadnought Iéna when this vessel’s magazines exploded accidently. The Iena was ripped apart, hurling burning fragments that started a small fire aboard Suffren, though no serious damage was done.

Democratie – collided with Suffren in May 1914

The following year, 1908, saw the Suffren’s port propeller fall off – which says a lot about the quality of her shafts – and two years later the starboard propeller followed suit. In 1911 and anchor chain broke (more metallurgical problems), killing a sailor. Another narrow escape was to follow in May 1914 when the Suffren lost power during fleet manoeuvres and collided with the later pre-dreadnought Démocratie, fortunately with only slight damage.

Suffren off Gallipoli – watercolour by Norman Wilkinson 1915

Given her unfortunate record, it is surprising that the Suffren not only delivered effective shore-bombardment service at Gallipoli in 1915 but that she survived some fourteen hits by Turkish shells, some as large as 9.2-inch, albeit suffering damage and deaths. She returned to Gallipoli after repair and during the evacuation of Allied troops in early 1916 she managed to collide with, and sink, the British horse-transport steamer Saint Oswald. She sustained serious damage herself and had to return to Toulon for repairs, after which she was deployed to the Salonica Front, where she saw no action.

Suffren bombarding Turkish positions, Gallipoli – watercolour by Norman Wilkinson 1915

Due for a full refit in late 1917 she was routed to the French naval base at Lorient, on the Atlantic coast of Brittany. She put in at Gibraltar, where she was delayed by bad weather, before setting out again, without an escort.

The Suffren’s luck, what little she had of it, had now finally run out. On the morning of 26th November, some 50 nautical miles off the Portuguese coast near Lisbon, she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-52, which was en-route to the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Cattaro. The U-52 had form – she had already sunk the Royal Navy’s light cruiser HMS Nottingham in the North Sea on 19th August 1916 and was to sink over 30 vessels in the course of her career. She was no less lethal on this occasion. Her torpedo detonated a magazine and the Suffren sank within seconds, taking her entire crew of 648 with her. U-52 searched the scene but found no survivors.

It was a tragic end to a career that had started inauspiciously and which had lurched from one accident to the other. Few ships can have been more consistently unlucky than the Suffren – a true maritime schlemiel.

s

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

1866: it’s four years since France invaded Mexico and set up a new ‘Mexican Empire’ with a puppet emperor imported from Europe but armies loyal to the republican government still resist. In a land devastated by battles, atrocities and reprisals, the tide of war is now turning in favour of the republic’s ‘Juarista’ supporters. France recognises that the war is unwinnable and evacuation inevitable, but first there will be bitter rearguard actions and old scores to settle.

Britain is neutral in this conflict, but large British interests – railway and mining enterprises – are at risk as the war-front edges ever closer. Investors in London are demanding British action to protect their assets.

Sub-Lieutenant Nicholas Dawlish is serving on the Pacific Station in the gunvessel HMS Sprightly. She, and her resourceful captain, are tasked with taking ‘appropriate’ action to guarantee the safety of these interests. The situation is complex – not only Juarista, French and Imperial Mexican forces but bandit groups, a volunteer Belgian Legion and ex-Confederate mercenaries are involved. And there’s a powerful ironclad, flying Imperial Mexican colours, commanded by an Austrian aristocrat who’s desperate for glory.

Dawlish is plunged into deadly action by land and sea and, with fluency in French and Spanish, he’ll be his captain’s right-hand man in a web of political intrigue, treachery and greed in which a single mistake can end both their careers.