Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 8

August 13, 2021

Lesbia's Sparrow

This post first appeared on The History Girls blog in April 2018 Gaius Valerius Catullus didn’t live long. Born into a wealthy family near Verona in around 84 BCE, he was dead by the age of thirty. But in this short space he made his mark as a lyric poet who, like Sappho perhaps, derived much of his extraordinary force from elements of his own life: he speaks so directly and so personally to the reader that we almost feel we know him. He wrote fiercely and wittily of both love and hatred. Many of his poems are savagely scatological (there’s a typical example here). He satirised Julius Caesar and was forgiven. His work survived in a single manuscript of 116 poems, so we’re lucky to have him. According to the Poetry Foundation website, Catullus' poetry addresses

...contradictory alternatives or tendencies: learning and passion; seriousness and frivolity; conservative values and revolutionary attitudes; ethical “piety” and vulgar obscenity; accounting and kissing; the great themes of Rome—love and betrayal, war and death; and lesser preoccupations with napkin stealing, urine, buggery, and bad breath.

Yes, well... It was probably in Rome that Catullus fell in love with the woman he names ‘Lesbia’ in his poems. She is usually identified as Clodia Metellus, a married lady who – from what he says – seems to given him the run-around and to have had a number of other lovers besides him. Two of the best known of the poems he wrote to her, or for her, or about her, concern her pet sparrow. Known in the canon as Catullus II and Catullus III, the first poem is a delicate, lively and distinctly eroticized account of the poet watching Lesbia playing with the sparrow and offering it her finger to nip. The strength of the poem is the tension set up between the girl’s apparent absorption with her pet, and Catullus’ voyeuristic gaze. You can read it at this link.

But it's the second poem I want to talk about. It's a lament: the sparrow is dead. Here’s the Latin:

Lugete, o Veneres Cupidinesqueet quantum est hominum venustiorum;passer mortuus est meae puellae,passer, deliciae meae puellae,quem plus illa oculis suis amabat; nam mellitus erat, suamque noratipsa tam bene quam puella matrem,nec sese a gremio illius movebat,sed circumsiliens modo huc modo illucad solam dominam usque pipiabat.qui nunc it per iter tenebricosumilluc unde negant redire quemquam.at vobis male sit, malae tenebraeOrci, quae omnia bella devoratis; tam bellum mihi passerem abstulistis. o factum male! o miselle passer! tua nunc opera meae puellae flendo turgiduli rubent ocelli.

Here is a prose translation by Leonard C. Smithers, published in 1894:

O mourn, you Loves and Cupids, and all men of gracious mind. Dead is the sparrow of my girl: sparrow, darling of my girl, which she loved more than her eyes; for it was sweet as honey, and its mistress knew it as well as a girl knows her own mother. Nor did it move from her lap, but hopping round first one side then the other, to its mistress alone it continually chirped. Now it fares along that path of shadows from where nothing may ever return. May evil befall you, savage glooms of Orcus, which swallow up all things of fairness: which have snatched away from me the comely sparrow. O wretched deed! O hapless sparrow! Now on your account my girl's sweet eyes, swollen, redden with tear-drops.

This little poem is so lovely, so tender - so playfully and deliberately conscious of the chiaroscuro created by sensuous physicality contrasted with death, it probably defies translation. So, I thought it would be interesting to look at a couple of different attempts. Put them together and maybe those of us who don’t read Latin (that includes me) can get an inkling of the original? Let’s start with Lord Byron who published his own translation at the age of nineteen in ‘Hours of Idleness’, 1807:

TRANSLATION FROM CATULLUS

Ye Cupids, droop each little head,Nor let your wings with joy be spread,My Lesbia's favourite bird is dead,Whom dearer than her eyes she lov'd: For he was gentle, and so true,Obedient to her call he flew,No fear, no wild alarm he knew,But lightly o'er her bosom mov'd:

And softly fluttering here and there,He never sought to cleave the air,He chirrup'd oft, and, free from care, Tun'd to her ear his grateful strain.Now having pass'd the gloomy bourn, From whence he never can return,His death, and Lesbia's grief I mourn,Who sighs, alas! but sighs in vain.

Oh! curst be thou, devouring grave!Whose jaws eternal victims crave,From whom no earthly power can save,For thou hast ta'en the bird away:From thee my Lesbia's eyes o'erflow,Her swollen cheeks with weeping glow;Thou art the cause of all her woe,Receptacle of life's decay.

Byron’s got the sweetness but misses the emotional strength. He apostrophises the Cupids but leaves out those more weighty ‘men of gracious mind’ from the first line, and the effect is to trivialise the poem. So does his omission of the line where Catullus says that Lesbia knows the sparrow as well as a girl knows her own mother – which speaks of a strong, tender, nurturing relationship. I’m not sure he’s hit off the playful mock-heroics either: Catullus portrays this sparrow almost as a sort of Aeneas descending into the underworld... Finally it would have made better poetry, and been truer to Catullus, to have changed the order of lines in the last verse, so:

Thou [ie: the grave] art the cause of all her woe,Receptacle of life's decay:From thee my Lesbia's eyes o'erflow,Her swollen cheeks with weeping glow.

The poem ought to end with the girl’s swollen, tear-filled eyes – which you can feel Catullus is longing to kiss – but Byron can’t manage it because the form he’s chosen demands that each eight-line verse rhymes AAAB/CCCB: the eighth and final line must rhyme with the fourth. And so he ends on a vision of the grave straight from an 18th century tombstone, ‘Receptacle of life’s decay’ – rather than leaving us with Catullus's erotically charged and tactile close-up of Lesbia’s face.

Sir Richard Burton does better. Here’s his translation, published in the same year as Smithers’ prose version, 1894:

LESBIA'S SPARROW

Weep every Venus, and all Cupids wail,

And men whose gentler spirits still prevail.

Dead is the Sparrow of my girl, the joy,

Sparrow, my sweeting's most delicious toy,

Whom loved she dearer than her very eyes;

For he was honeyed-pet and anywise

Knew her, as even she her mother knew;

Ne'er from her bosom's harbourage he flew

But 'round her hopping here, there, everywhere,

Piped he to none but her his lady fair.

Now must he wander o'er the darkling way

Thither, whence life-return the Fates denay.

But ah! beshrew you, evil Shadows low'ring

In Orcus ever loveliest things devouring:

Who bore so pretty a Sparrow fro' her ta'en.

(Oh hapless birdie and Oh deed of bane!)

Now by your wanton work my girl appears

With turgid eyelids tinted rose by tears.

He’s got the sweetness, the eroticism and the darkness too: he almost succeeds in the mock-heroics (‘evil Shadows low’ring/In Orcus ever loveliest things devouring/ ...Oh hapless birdie and Oh deed of bane...’) His choice of poetic diction is an interesting blend of the archaic and stiff – ‘Thither, whence life-return the fates denay’ – and the vernacular – ‘my girl’. I think it just about works in its own right, but it’s very mannered and doesn’t sound like somebody chatting to us.

The same cannot be said of Dorothy Parker’s wonderful riff on the poem (included in ‘The Original Portable’, 1944) – which gives Lesbia herself a voice, and some very distinct opinions!

From A Letter From Lesbia

... So, praise the gods, Catullus is away!

And let me tend you this advice, my dear:

Take any lover that you will, or may,

Except a poet. All of them are queer.

It's just the same – a quarrel or a kiss

Is but a tune to play upon his pipe.

He's always hymning that or wailing this;

Myself, I much prefer the business type.

That thing he wrote, the time the sparrow died –

(Oh, most unpleasant – gloomy, tedious words!)

I called it sweet, and made believe I cried;

The stupid fool! I've always hated birds...

It’s not, of course, a translation at all. But I reckon Catullus would have loved it.

Picture credits

Lesbia and her Sparrow by Sir Edward John Poynter

Lesbia weeping over her sparrow by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1866Catullus comforting Lesbia on the death of her sparrow by Antonio Zucchi (1726-1796)Dead Sparrow by E. Sloane Stanley, 19th c.

August 3, 2021

The Fairy Flag and the Paths of the Dead

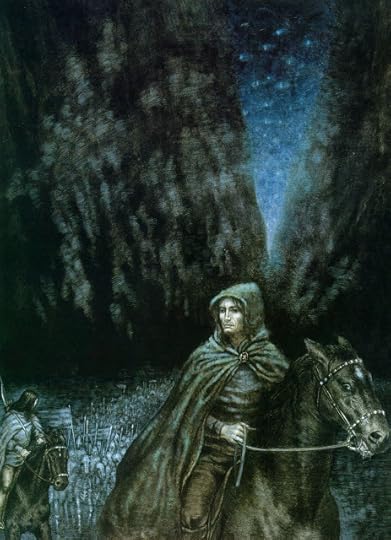

'To The Stone of Erech' by Inger Edelfeldt

'To The Stone of Erech' by Inger EdelfeldtYou remember the episode in JRR Tolkien’s ‘The Return of the King’ in which Aragorn, Gimli and Legolas dare to enter the Dwimorberg or Haunted Mountain, with the aim of gathering a host of the Dead to prevent the Corsairs of Umbar from coming to the aid of Mordor during the siege of Gondor? But which version do you remember – Tolkien’s or Peter Jackson’s? For the usually excellent Peter Jackson film goes full-on Indiana Jones at this point, with cathedral-vast caverns glowing in eerie green light, smoking dry ice and grimacing skeletal phantoms, climaxing in an avalanche of skulls which almost buries our heroes as they struggle out of the mountain.

For me, Tolkien’s far more restrained treatment is more effective (and it’s easy to forget that in the book, Aragorn and his friends are also accompanied by a troop of the Dunedain, and Elladan and Elrohir, the two sons of Elrond). And the bargain between Aragorn and the Dead doesn't occur underground. The company passes through the dark tunnels under the mountain with the invisible, menacing host following at their heels; they emerge on the other side into a blue dusk and then ride for another whole day all the way up through Morthond Vale to the ancient Stone of Erech, where prophecy has decreed the oath-breaking dead must one day come. Here is a lightly abridged version of what happens next:

Long had the terror of the Dead lain upon that hill and upon the empty fields about it. For upon the top stood a black stone, round as a great globe, the height of a man, though its half was buried in the ground. … None of the people of the valley dared to approach it … for they said it was a trysting place of the Shadow-men, and there they would gather in times of fear, thronging round the Stone and whispering.

To that Stone the Company came and halted in the dead of night. Then Elrohir gave to Aragorn a silver horn, and he blew upon it; and … they were aware of a great host gathered all about the hill on which they stood; and a chill wind like the breath of ghosts came down from the mountains. But Aragorn dismounted, and standing by the Stone he cried in a great voice:

‘Oathbreakers, why have ye come?’

And a voice was heard out of the night that answered him, as if from far away:

‘To fulfil our oath, and have peace.’

Then Aragorn said, ‘The hour is come at last. Now I go to Pelargir upon Anduin, and ye shall come after me. And when all this land is clean of the servants of Sauron … ye shall have peace and depart for ever. For I am Elessar, Isildur’s heir of Gondor.’

And with that he bade Halbarad unfurl the great standard which he had brought, and behold! it was black, and if there was any device upon it, it was hidden in the darkness. Then there was silence, and not a whisper nor a sigh was heard again all the long night. The Company camped beside the Stone, but they slept little, because of the dread of the Shadows that hedged them around. […] But the next day there came no dawn, and the Grey Company passed on into the darkness of the Storm of Mordor and were lost to mortal sight; but the Dead followed them.

We hear the sequel from Legolas and Gimli: how, coming to Anduin, the Shadow Host swept over the Corsairs’ ships like a grey tide, till mad with terror they leapt overboard and, ‘reckless we rode among our fleeing foes, driving them like leaves’.

Now, ghostly armies are not uncommon in British folklore. Roman soldiers are glimpsed steadily marching along old roads, or even through the cellars of the Treasurer's House in York (pictured above), and Civil War battalions are seen fighting in the sky over Edgehill, Marston Moor and Naseby, but in all these cases the phantoms re-enact old battles rather than join new ones. The story of ‘The Angels of Mons’ is an exception, but that was based upon Arthur Machen’s short story ‘The Bowmen’, published in September 1914, in which the ghostly bowmen of Agincourt come to the aid of British troops. To Machen’s dismay his tale was mistaken by some to be a factual account, and swiftly morphed into an unstoppable legend.

Most phantom armies are visions or memories of past conflicts. But an unusual story from Skye has me wondering whether Tolkien knew of it, and if it influenced his account of Aragorn’s mustering the Hosts of the Dead. It is the tale of the Fairy Flag of the Macleods.

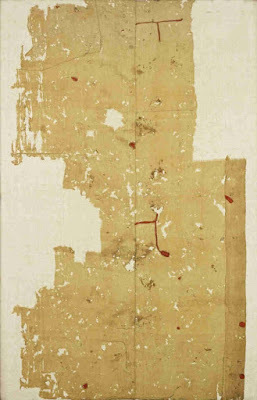

The flag really exists. It is a rectangle of very old silk, much tattered and worn, said once to have been bordered with red crosses which have now faded from sight, and spotted with red ‘elf-marks’. Experts at the ‘South Kensington Museum’ – as the V&A was known until 1899 – who examined it in the late 19thcentury thought it might be of Syrian origin, with a date sometime between the 4th and 7th centuries. It is still treasured in the Macleod stronghold of Dunvegan Castle on Skye.

How it came into the Macleods’ possession is lost to history, but legend says it was a fairy gift. There are various versions of the story, but the gist is that one of the early Dunvegan chieftains took a fairy bride. The couple were happy together until their son was born, but then ‘the call to return to her own people came to her. Against this order there was never, for her or for others, any appeal.’ At the Fairy Bridge – again, a real bridge, where the road south from Dunvegan Castle forks east towards Edinbane – they parted, never to meet again. In one version, the fairy gives him the Flag at their parting; in another, she comes invisibly to cover her child with it when he wakes cold and lonely in his cradle while a feast is held in his honour downstairs. In all versions, the Flag is given to the Macleods with the promise of immediate and powerful supernatural assistance, if it is waved in peril or trouble. There is one condition: only three times may it be used in this way. So far it is said to have been used twice.

One occasion was in 1578, when the Macleods’ hereditary enemies the Macdonalds landed eight boats at Trumpan on the Waternish peninsula of Skye while most of the inhabitants were at church, and set it alight. Those inside died in the fire, or were cut down as they tried to escape, but one person managed to raise the alarm: and the flames were also seen by the Macleod watchman from the top of Dunvegan Castle. Here’s what happened next: the account is from ‘Skye: The Island and its Legends’ by Otta Swire (1952):

The Macleods came with what strength they could muster close at hand. The Macdonalds had been delayed by a force of old people and boys whose strength they could not estimate. By the time they reached the shore the tide had gone down, and their galleys lay high and dry, while hidden from them the Macleod forces, which had crossed the loch, were already landing. A terrible battle ensued, in which it is said that the Macleods, much outnumbered, had recourse to waving the Fairy Flag, and that the Macdonalds immediately saw a great host approaching (which in fact was not of this world) and fled. Be that as it may, the Macleods were victorious, the Macdonalds being almost annihilated.

So, the Flag was given to the Macleods by a woman of the Sithe, an elf-woman who loved a mortal man but had to part from him. Now, Aragorn’s standard is also the gift of an elf-woman, Arwen Undomiel whom he has long loved and been parted from. It is brought to him by his kinsman Halbarad the Dúnadan, with the message:

‘She wrought it in secret, and long was its making. But she also sends word to you: The days now are short. Either our hope comes, or all hope’s end. Therefore I send thee what I have made for thee. Fare well, Elfstone!’

In both stories, possession of the Flag or the standard identifies the carrier: the Fairy Flag can only be borne and wielded by the Macleods. And though the Dead follow Aragorn to the Stone of Erech, they seem a threat not wholly tamed until the unfurling of the black elf-wrought standard sets the seal upon Aragorn’s claim to be Elessar, heir of Isildur to whom the original oath was sworn, and rightfully able to command them to fulfil their vow. And in both stories the one who wields the flag can, in extremis, call up supernatural reinforcements in the form of a terrifying phantom army.

Picture credits:

The Paths of the Dead: Inger Edelfeldt

Roman ghosts at the Treasurer's House: artist unknown: source website Imperium Romanum

The Fairy Flag, close-up: courtesy of the Dunvegan Castle website

The Fairy Flag in situ: courtesy of the Dunvegan Castle website

July 27, 2021

Concerning a Narnian fish

After I’d thanked the Hertfordshire gentleman whose thoughtful letter prompted my post of last week – and yes, it was a real letter that came through a real letter box – he has written to me again. And I have to share it with you. This time it concerns a Narnian fish called a pavender, which is mentioned not only in Prince Caspian, but also in The Silver Chair when Jill and Eustace enjoy one of the few good meals of their adventure, a royal feast in the great hall of Cair Paravel.

The banners hung from the roof, and each course came in with trumpeters and kettledrums. There were soups that would make your mouth water to think of, and the lovely fishes called pavenders, and venison and peacock and pies, and ices and jellies and fruit and nuts, and all manner of wines and fruit drinks.

I’d sometimes idly wondered if there really might be a fish called a pavender – after all, there are plenty of strangely named English fishes, such as gudgeon, chub, dace, roach, etc – or whether Lewis had simply invented it. Well, the answer is neither, and it’s far more fun! Here is the Hertfordshire gentleman to explain it all:

"In Prince Caspian, as you may remember, Trumpkin catches and cooks for the Pevensies some delicious little fish called pavenders. This, I believe, is a private scholarly joke of Lewis’s. It is a reference to a poem published originally in Punch, called ‘A False Gallop of Analogies’, by one Warham St Leger. The conceit of the poem springs from a reference to ‘the chavender, or chub’ in Isaac Walton’s The Compleat Angler. So it begins:

There is a fine stuffed chavender,

A chavender, or chub

That decks the rural pavender

The pavender, or pub,

Wherein I eat my gravender,

My gravender, or grub…

And so on, with references to ‘sweet lavender, or lub’ and administering a snavender, or snub, to an intrusive young cavender, or cub; and the ravender, or rub, of having to return to town. If you are interested, you can find the whole poem in full at: http://www.poetrynook.com/poem/false-gallop-analogies."

(In fact I suggest you visit this link without delay and read the poem in full; it will make you happy!) The Hertfordshire gentleman continues:

"I am only aware of the poem through encountering it in the Festival of Britain issue of Punch, which I was given by my father at the time. As well as topical items … it contained an anthology of notable cartoons and other snippets, from issues over the past century. Lewis would no doubt relish the reference to the ‘pavender, or pub’ and have stored it away for future use"

I don’t need to tell you how delighted I am to have learned the origin of this obscure Narnian fish (or dish) and (in the words of the other Lewis, Lewis Carroll) to have un-dish-covered the fish and dish-covered the riddle.

F ind my book, "From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with my nine year-old self" at Hive.co.uk, at Amazon.co.uk, and at all good bookshops.

July 19, 2021

Orphans in Narnia

About a month ago I was asked by the website Female First to write a short piece about families in Narnia, and I came to the conclusion that happy families are not easy to find there. You can read what I wrote here, but to summarise: the Pevensies’ parents are remarkable mainly for their absence; we never even set eyes on them until Lucy sees them waving from a distant “English” spur of Aslan’s holy mountain, by which time they are all of them dead. Eustace Scrubb’s parents send him to boarding school at the ominously named Experiment House, where he is bullied and made miserable. So do Jill’s. All we learn of Polly’s parents is that her mother sends her to bed for coming home late. Digory's father is far away in India, so he and his dying mother are forced to live with kindly but ineffectual Aunt Letty, and dangerously ‘mad’ Uncle Andrew.

So much for the children from our world. What about those born in Narnia itself? Shasta (aka Prince Cor of Archenland) is stolen at birth and raised by an abusive foster-father who tries to sell him into slavery. Aravis escapes from a father who is pressuring her into a detestable marriage. Prince Caspian’s father has been murdered by his usurping uncle, King Miraz, so that when his aunt, Queen Prunaprismia, gives Miraz an heir, Caspian’s own life is in immediate danger. Whether true fathers or surrogates, father-figures in the Narnia books tend either to be absent, or else very much part of the problem.

Orphaned children, or children with absent or neglectful parents are of course a recurrent theme in children’s fiction and in fairytales. Without adults to help them, such children have to solve their own problems: in narrative terms it gives them agency and establishes an immediate bond of sympathy between reader and character. Think of Hansel and Gretel, Cinderella, Snow-White, Heidi – or Harry Potter, Lyra and Will, and Seren Rhys in Catherine Fisher's enchanting middle-grade book The Clockwork Crow (which I highly recommend). Orphaned or neglected children frequently appear in adult fiction too, such as Jane Eyre, or Rudyard Kipling's Kim, or Cosette in Les Miserables, and are liberally scattered throughout the works of Dickens (David Copperfield, Little Dorrit, Pip, Oliver Twist, Jo the crossing sweeper and so on).

But there is a poignancy about the Narnian orphans that may ultimately derive from Lewis’s loss of his own mother to cancer when he was nine years old. As was then common practice, she was nursed and even operated upon at home, and in his autobiography Surprised by Joy he describes how her illness affected him and his brother: ‘Our whole existence changed into something alien and menacing, when the house became full of strange smells and midnight noises and sinister whispered conversations’. He tells of desperately praying God for a miracle to save his mother, and the terror of being taken into her bedroom ‘to see her’ when she had died.

Then, just a few weeks after this huge loss, his grieving father, probably with no idea what better to do with his small son, sent him to the English boarding school his brother already attended, an establishment which unfortunately was run by a sadistic headmaster who might have come straight out of Dickens. No one can mistake the emotion with which Lewis paints himself and his fellow pupils as ‘pale, quivering, tear-stained, obsequious slaves’. No wonder he never had a good word to say about schools in the Narnia series. He couldn't tell his father, partly because children often don't know how, but also because their relationship had suffered and, as he himself acknowledged, never really recovered, even after he was allowed to leave school to study with a tutor who recognised and encouraged his potential. Perhaps it's significant that (Aslan aside), Prince Caspian's tutor Dr Cornelius is the one Narnian father-figure whom Lewis depicts as entirely laudable.

Surprised By Joy was published in 1955, the same year as The Magician’s Nephew - the book in which he relives, re-writes, re-imagines the events of his mother's death and gives them the miraculously happy ending he’d longed for as a child. It's clear that the painful series of events surrounding his mother's death remained vivid in Lewis’s memory.

For there are many other boys in the Narnia stories whose mothers have died. Shasta is separated from his mother when he is kidnapped as a baby, but she then dies long before he can be reunited with her. And there is no particular narrative reason why this should be so. It just is – perhaps Lewis couldn't visualise such a reunion. Caspian’s parents are both already dead when we first meet him as a little boy: his father murdered by Miraz and his mother (perhaps) dying naturally, and earlier. Youthful Prince Rilian of The Silver Chair loses his mother – Ramandu’s daughter and Caspian’s Queen – when she is stung to death by a poisonous green serpent. This serpent is the Green Witch, who compounds her wickedness by enchanting and imprisoning Rilian: he loses ten years of his life with her and is reunited with his father Caspian only on the old king's deathbed.

Much of this post has been inspired by a letter I recently received from a gentleman in Hertfordshire who has pointed out something I hadn't noticed, near the end of The Last Battle. It comes after Peter has shut and locked the Stable Door and ‘Narnia is no more’. Lucy is in tears, but Peter chides her: ‘What, Lucy! You’re not crying? With Aslan ahead, and all of us here?’ Tirian replies for her: ‘Sirs, the Ladies do well to weep. See, I do so myself, I have seen my mother’s death. ...It were no virtue, but great discourtesy, if we did not mourn.’

My correspondent goes on to say:

‘I have seen my mother’s death.’Narnia began with Digory seeking something to prevent his mother’s death. The tree grown from the Narnian apple that does so provides wood for the wardrobe that is the first way into Narnia. The death of Rilian’s mother is the spring for the story of The Silver Chair, and now Narnia is mourned by Tirian as his dead mother. The cycle is complete. One might say that all his life Lewis was looking for his mother, though I don’t place too much stress on that. But certainly, to me Narnia has the air of a land of lost content.

So it is that Narnia, the beloved land that has nurtured him, is mourned by Tirian as deeply as if she were his dead mother. I find this and its implications very touching. One of the lovely things since the publication of Spare Oom at the beginning of May has been the conversations it’s provoked, both on and off line. There is always something more to say about Narnia.

You can find my book, "From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with my nine year-old self" at Hive.co.uk, at Amazon.co.uk, and from all good bookshops.

All the illustrations in this post are of course by the wondeful Pauline Baynes.

June 23, 2021

The Silver Apples of the Moon, the Golden Apples of the Sun

This was our apple tree last September, so laden with fruit that branches actually cracked and broke off under the weight, as though taking Keats’ lines from Ode to Autumn far too literally –

To bend with apples the mossed cottage-treesAnd fill all fruit with ripeness to the core…

The lawn was almost ankle deep in windfalls.

What is it about apples? Why are they so evocative? Why was the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – not actually named in the Bible – assumed to be an apple? Why did the Firebird, in Russian folklore, steal golden apples from the garden of the Czar? Why did golden apples of immortality grow in the Garden of the Hesperides, why was the Norse goddess Idun the keeper of golden apples which preserved the youth of the gods? Why was the Apple of Discord – with its inscription To the Fairest – an apple, and why were three golden apples so irresistible to Atalanta that she paused to pick them up and lost her race? (Mind you, that dress she's wearing wouldn't help.)

The apple as the fruit of immortality, or perhaps equally of death, appears as a symbol in Celtic mythology too. Heralds from the Land of Youth might bear a silver apple branch, with silver blossom and golden fruit whose tinkling music lulled the hearers to sleep – perhaps to everlasting sleep. Arthur, after his final battle, went to the island of Avalon, the island of apples, to be healed of his mortal wound. Then of course there’s the apple given by the wicked Queen to Snow-White, one bite of which sends the little princess into a death-like sleep.

Apples are tokens of love and promises of eternity. In Yeat’s ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, the lovelorn Aengus seeks forever the beautiful girl from the hazel wood.

Though I am old with wanderingThrough hollow lands and hilly landsI find out where she has gone,And kiss her lips and take her hands;And walk among long dappled grassAnd pluck till time and times are done,The silver apples of the moon,The golden apples of the sun.

But such an eternity is probably also the land beyond death.

Where do apples even come from, why are they so ubiquitous? Why, even today, are so many varieties available even in supermarkets, usually the home of homogeneity? I went into our local Sainsburys the other day and counted eleven different named varieties of apple all on sale at once: Empire, Royal Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Cox’s Orange Pippin, Russets, Granny Smiths, Pink Ladies, Jazz, Braeburns and Bramleys. By contrast, there were only four named varieties of pears, and everything else was generic – bananas, strawberries, oranges, etc.

Apples are related to roses, I’m delighted to tell you. According to a rather lovely book called ‘Apples: the story of the fruit of temptation’, by Frank Browning (Penguin 1998):

‘In the beginning there were roses. Small flowers of five white petals opened on low, thorny stems, scattered across the earth in the pastures of the dinosaurs, about eighty million years ago. …These bitter-fruited bushes, among the first flowering plants on earth, emerged as the vast Rosaceae family and from them came most of the fruits human beings eat today: apples, pears, plums, quinces, even peaches, cherries, strawberries, raspberries and blackberries.

‘The apple [paleobotanists believe]… was the unlikely child of an extra-conjugal affair between a primitive plum from the rose family and a wayward flower with white and yellow blossoms of the Spirea family, called meadowsweet.’

Isn’t that wonderful? Apples as we know them today developed in Europe and Asia. The Pharoahs grew them. The Greeks and Romans grew them. And they keep. You can store apples overwinter, eat them months after you’ve picked them: fresh fruit in hard cold weather when there’s nothing growing outside. So perhaps you would think of them as life-giving, immortal fruit. They smell fragrant. They feel good too: hard-fleshed, smooth, a cool weight in the hand.

The medieval lyric 'Adam lay y-bounden' provocatively celebrates the Fall of Man when Adam ate the forbidden fruit:

And all was for an appil An appil that he tokeAs clerkes findenWritten in her boke.

It ends on the mischievously subversive thought that if Adam had not eaten the apple, Our Lady would never have become the Heavenly Queen:

Blessed be the timeThat appil take was!Therefore we maun singen:Deo gratias.

Here is a poem by John Drinkwater (surely the most poetically-named poet ever!) which captures some of those mystical coincidences of apples, eternity, sleep, moonlight, magic and death.

MOONLIT APPLES

At the top of the house the apples are laid in rows,And the skylight lets the moonlight in, and those Apples are deep-sea apples of green. There goesA cloud on the moon in the autumn night.

A mouse in the wainscot scratches, and scratches, and thenThere is no sound at the top of the house of menOr mice; and the cloud is blown, and the moon againDapples the apples with deep-sea light.

They are lying in rows there, under the gloomy beamsOn the sagging floor; they gather the silver streamsOut of the moon, those moonlit apples of dreamsAnd quiet is the steep stair under.

In the corridors under there is nothing but sleep.And stiller than ever on orchard boughs they keepTryst with the moon, and deep is the silence, deepOn moon-washed apples of wonder.

Picture credits:

Apple tree: Author's gardenAtalanta racing Hippomenes: Willen van Herp, c1650Silver Apples: Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

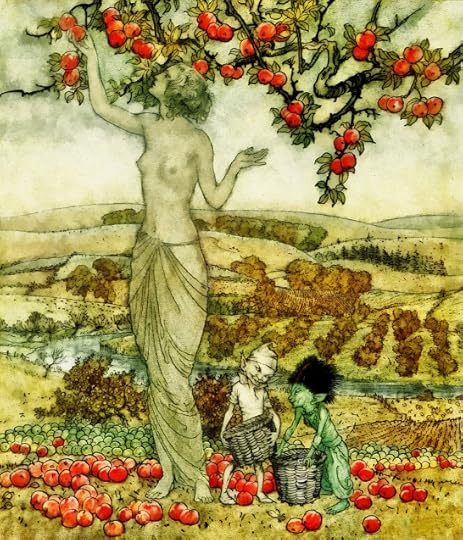

Adam and Eve: Lucas Cranach, 1537Apple Tree: Arthur Rackham

Labels: Apple of discord, Apples, Eden, Forbidden fruit, John Drinkwater, Katherine Langrish, Keats, Tree of Knowledge, Yeats

June 18, 2021

A Fine Song of Love

The past is another country. and it can take a great deal of research and imaginative effort to recreate its multilayered richness of sights, sounds, smells, textures and tastes. Visiting the Chiltern Open Air Museum a few years ago I found myself shouting to be heard over the almost unbearable thunder of iron-rimmed cartwheels rolling over cobbles. I’d had no idea carts made so much noise – and that was a single, large, four-wheeled wagon pulled by a single horse. Imagine the din around the warehouses of London Docks in the 1880s!

Music goes beyond natural sound, though. Music is a cultural construct full of meaning; it reflects, interprets, and to a large extent creates the manners and desires of its own time. It's natural to refer to music as we construct history. Swingtime, jazz, rock and roll, punk, reggae, hip-hop – all tell something about the decades in which they flourish. Impossible to imagine the sixties without the Beatles or the Kinks. The same must be true for the deeper past. I once thrilled to a British Museum reconstruction of a Roman trumpet call, and what about the prehistoric bone flutes that were played in caves like Lascaux? (And why were they played, and for whose attention? The earth spirits?)

My children’s novel Dark Angels (HarperCollins) is set on the Welsh borders in the 1190s, and features a flawed heroic figure, Lord Hugo de La Motte Rouge, Norman warlord and ex-crusader who believes his dead wife may – just may – not be dead after all, even though seven years have passed since he buried her. She may have been spirited away by the elf-folk and taken into the tunnels under the hill. In which case, there might be a chance he could rescue her.

There are a quite a few 12th century legends on this mysterious subject, the idea of lost lovers re-encountered in some fairy land of the dead. Walter Map, a courtier at the court of Henry II, tells the story of a Breton knight who rescued his dead-and-buried wife when, months later, he saw her whirling in a fairy dance. And the 13th century retelling of the Orpheus myth, Sir Orfeo, probably ultimately dates from this time, translated from a Breton lai into Middle English.

So there I was with the idea that my knight Lord Hugo would be a sort of Orpheus figure. Therefore he needed to be musical. Now the Breton lais are lengthy stories in verse; they were performed by minstrels who probably chanted them with a musical prelude and interludes. And of course the 12th and 13th centuries were also the time of the troubadours of southern France, whose songs were primarily songs of fin’ amour – of romantic love in high society.

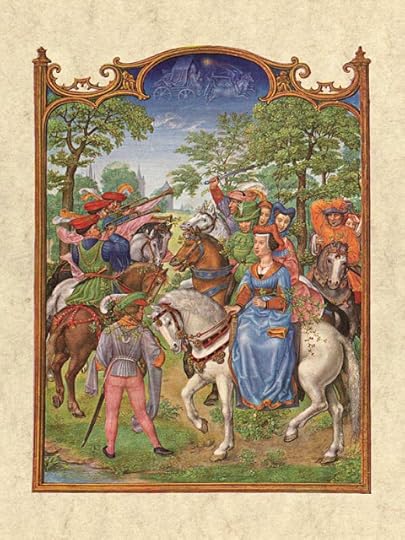

Garden of Pleasure, Harley 4425, 15th C. It’s been suggested that the notion, even the emotion of romantic love was created by the troubadours: a product of the hot-house needs of often very young noblemen and noblewomen living in close proximity in small castles, with nothing much to do – spending time together every day, yet with sex strictly off-limits, marriage being a formal affair of property and alliances arranged by their elders. So this new music arose, a music of youth, full of expressions of forbidden desire: subversive, exciting, dangerous and fashionable.

Garden of Pleasure, Harley 4425, 15th C. It’s been suggested that the notion, even the emotion of romantic love was created by the troubadours: a product of the hot-house needs of often very young noblemen and noblewomen living in close proximity in small castles, with nothing much to do – spending time together every day, yet with sex strictly off-limits, marriage being a formal affair of property and alliances arranged by their elders. So this new music arose, a music of youth, full of expressions of forbidden desire: subversive, exciting, dangerous and fashionable.Many troubadours were high-born men and women, whose songs would usually be performed for them by a joglar or jongleur, a professional singer. Still, it seemed to me quite possible that my own Lord Hugo might on occasion be prevailed upon to sing his own songs – especially if he thought that doing so might help win back his wife from the dead land.

So now I needed to listen to troubadour songs. Here's an anonymous 13th century song performed by Arnaud Lachambre; it's known by its first line: 'Voulez vous que je vous chante?' I made a free translation of it to get myself in the mood for writing songs for Lord Hugo.

Volez vous que je vous chante Would you like me to sing to youUn son d’amours avenant? A fine song of love? Vilain nel fist mie, By no peasant was it made, Ainz le fist un chevalier But a gentle knight who laySous l’ombre d’un olivier With his sweetheart in his armsEntre les bras s’amie. In an olive tree’s shade.

Chemisete avoit de lin She wore a linen chemise,Et blanc peliçon hermin A pelisse of white ermine – Et bliaut de soie Of silk was her dress,Chauces ot de jaglolai Her stockings were of iris leavesEt solers de flours de mai And slippers of mayflowersEstroitement chauçade Her feet to caress.

Ceinturete avoit de feuille Her girdle was of leavesQue verdist quant li tens meuille, Which grow green when it rains,D’or est boutonade Her buttons of gold so fine,L’aumosniere estoit d’amour Her purse was a gift of loveLi pendant furent de flours And it hung from flowery chainsPar amours fu donade. As it were a lovers’ shrine.

Et chevauchoit une mule And she rode on a mule,D’argent ert la ferruere The saddle was of gold,La sele ert dorade; All silver were its shoes;Sus la croupe par derriers To provide her with shade, Avoit plante trois rosiers On the crupper behind herPour faire li ombrage. Three rose-bushes grew.

Si s’en va aval la pree As she passed through the fieldsChevaliers l’ont encontree She met gentle knightsBeau l’on saluade: Who demanded courteously:“Belle, dont estes vous nee?” “Fair one, where were you born?”“De France sui la louee, “From France am I come.De plus haut parage.” And of high family.”

“Li rossignol est mon pere “The nightingale is my fatherQui chant sor la ramee Who sings from the branchesEl plus haut boscage. Of the forest’s highest tree.La seraine est mon mere The mermaid is my motherQui chante en la mer sale Who sings her sweet notesLi plus haut rivage.” Bythe banks of the salt sea.”

“Belle, bon fussiez vous nee! “Fair one, well were you born! Bien estes emparentee Well fathered, well motheredEt de haut parage. And of high family.Pleüst á Dieu nostre pere Now would God only grantQue vous ne fussiez donee That you might be givenA femme esposade.” In marriage to me!”

Could a song be more sensual, the object of desire more dangerous? The lady in this chanson is a headily-erotic blend of wildwood flowers, songs and the fairy world, and that purse which hangs from her girdle on flowery chains ‘like a lover’s shrine’ is certainly a metaphor Freud would have recognised. No wonder the young knights acknowledge her ‘high degree’ and long for her hand in marriage. It’s enough to turn their parents’ hair grey.

Lady out riding, 16th C, by Gerard Horenbout Troubadour songs often use images such as the coming of the green leaves in spring, and the song of the nightingale, to express the pain and delight and longing of love. Here’s Guillem de Peiteus, Count of Poitiers and Duke of Aquitaine, comparing love to a hawthorn bough:

Lady out riding, 16th C, by Gerard Horenbout Troubadour songs often use images such as the coming of the green leaves in spring, and the song of the nightingale, to express the pain and delight and longing of love. Here’s Guillem de Peiteus, Count of Poitiers and Duke of Aquitaine, comparing love to a hawthorn bough:As for our love, you must know howLove goes – it’s like the hawthorn boughThat on the living tree stands, shakingAll night beneath the freezing rainTill next day, when the warm sun, waking,Spreads through green leaves and boughs again.

(Tr. W. D. Snodgrass.)

In the end I wrote this for Hugo to sing of his love:

When all the spring is bursting and blossoming,And the hedge is white with blossom like a breaking wave,That’s when my heart is bursting with love-longingFor the girl who pierced it, for that sweet wound she gave,

And I hear the nightingale singing in the forest – Singing for love in the forest: “Come to me, I am alone…Better to suffer love’s pain for a single kissThan live for a hundred years with a heart of stone.”

It’s Hugo’s love and pain that drives the plot of Dark Angels and I needed the plangent, beautiful music of the 13th century to get it right.

Labels: 13th century, 13th century music, Dark Angels, fin'amour, medieval Provence, Music, Orpheus, Troubadours

June 7, 2021

Thresholds

Aged nine and passionate about Narnia, I wrote a set of my own stories about that magical country, and that far-off labour of love resulted in the publication this year of my book 'Spare Oom'. (So great is the power of childhood reading to reverberate down the years!) Now my friend and fellow author Elizabeth Kay has sent me a poem she wrote about her own experience of reading the Chronicles of Narnia when she was a child of ten. It’s so lovely I’ve asked her to let me share it with you, so this is her introduction.

For me, aged ten, the Chronicles of Narnia produced one of those lightbulb moments. I can remember sitting up in bed and thinking, ‘hang on – died and came back to life three days later? Where have I heard that before?’ It was my discovery of subtext, and the moment I made the connection, decoding the rest of the books became an obsession.

Vera Rich, poetry translator extraordinaire who died ten years ago, knew all sorts of people and told me that Tolkien had tackled Lewis as to why everyone in Narnia spoke English. The Magician’s Nephew was written retrospectively to explain this, as well as being a convenient parallel for Genesis.

My French teacher at school, a Dr Moore, lived with her elderly father who had been an Oxford don and a friend of all the Inklings. How I wish I’d asked a few more questions! But those books left such a lasting impression that when I wrote my own fantasy, The Divide, I wanted to recapture some of that feeling of exploring anther world peopled with all the mythical beings of my childhood. It also led to my poem The Threshold, which was, incidentally, published by Vera Rich in her magazine Manifold.

THE THRESHOLD

When I was ten I found a door.

I turned the key; there was a catch,

Once opened, there were many more.

I’d always wanted to explore -

To cure that itch I couldn’t scratch.

When I was ten I found a door.

I heard a paper lion roar;

I watched a magic molehill hatch -

Once opened, there were many more.

I learnt about an ancient law,

And how the empress met her match;

When I was ten I found a door.

I thought about it, and I saw

The worlds that I could now unlatch;

Once opened, there were many more.

I put the book down on the floor

(I’d only read the briefest snatch)

When I was ten I found a door,

Once opened, there were many more.

© Elizabeth Kay: Manifold Magazine, Spring 1998

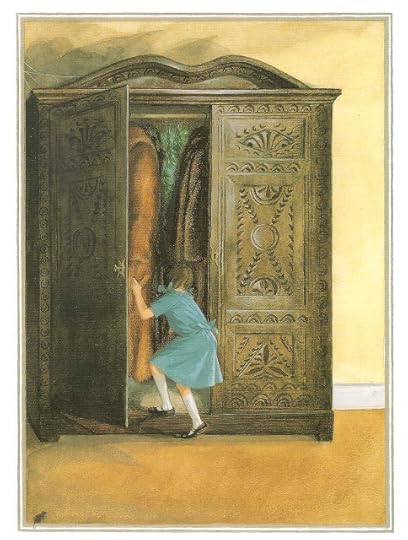

Picture credits:

Lucy enters the wardrobe: Pauline Baynes illustration to the deluxe edition of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (HarperCollins 1998)

The wardrobe: Pauline Baynes illustration, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, Geoffrey Bles, 1950

May 25, 2021

Dwarfs, Pixies and the “Little Dark People”

In ‘A Book of Folk-Lore’ (1913) the Devon folklorist Sabine Baring-Gould recounts three instances in which he and members of his family ‘saw’ pixies or dwarfs. Here is what he says:

In the year 1838, when I was a small boy of four years old, we were driving to Montpellier [France] on a hot summer’s day, over the long straight road that traverses a pebble and rubble strewn plain on which grows nothing save a few aromatic herbs.

I was sitting on the box with my father, when to my great surprise I saw legions of dwarfs about two feet high running along beside the horses – some sat laughing on the pole, some were scrambling up the harness to get on the backs of the horses. I remarked to my father what I saw, when he abruptly stopped the carriage and put me inside beside my mother, where, the conveyance being closed, I was out of the sun. The effect was that little by little the host of imps diminished in number till they disappeared altogether.

When my wife was a girl of fifteen, she was walking down a lane in Yorkshire between green hedges, when she saw seated in one of the privet hedges a little green man, who looked at her with his beady black eyes. He was about a foot or eighteen inches high. She was so frightened that she ran home. She cannot recall exactly in what month this took place, but knows it was a summer’s day.

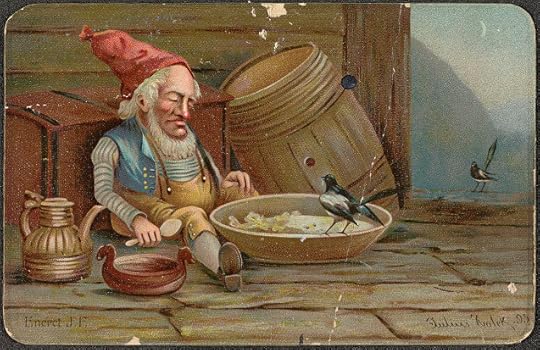

One day a son of mine, a lad of about twelve, was sent into the garden to pick pea-pods for the cook to shell for dinner. Presently he rushed into the house as white as chalk to say that while he was engaged upon the task imposed upon him he saw standing between the rows of peas a little man wearing a red cap, a green jacket, and brown knee-breeches, whose face was old and wan and who had a gray beard and eyes as black and hard as sloes. He stared so intently at the boy that the latter took to his heels. I know exactly when this occurred, as I entered it in my diary, and I know when I saw the imps by looking in my father’s diary, and though he did not enter the circumstance, I recall the vision today as distinctly as when I was a child.

In spite of the vivid and detailed nature of these visions Baring-Gould didn’t believe he or his family had seen anything ‘real’. He continues stoutly:

Now, in all three cases, these apparitions were due to the effect of a hot sun on the head. But such an explanation is not sufficient. Why did all three see small beings of a very similar character? With ... temporary hallucination the pictures presented to the eye are never originally conceived, they are reproductions of representations either seen previously or conceived from descriptions given by others. In my case and that of my wife, we saw imps, because our nurses had told us of them… In the case of my son, he had read Grimms’ Tales and seen the illustrations to them.

Rational indeed – though still quite puzzling that sun-stroke or heat-stroke should in each case have brought on visions of dwarfs or pixies. But perhaps it ran in the family. However that may be, Baring-Gould acknowledges that this explanation only pushes the problem further into the past – ‘Where did our nurses, whence did Grimm [sic] obtain their tales of kobolds, gnomes, dwarfs, pixies, brownies etc? … To go to the root of the matter, in what did the prevailing belief in the existence of these small people originate?’ And he answers thus:

I suspect that there did exist a small people, not so small as these imps are represented, but comparatively small beside the Aryans who lived in all those countries in which the tradition of their existence lingers on.

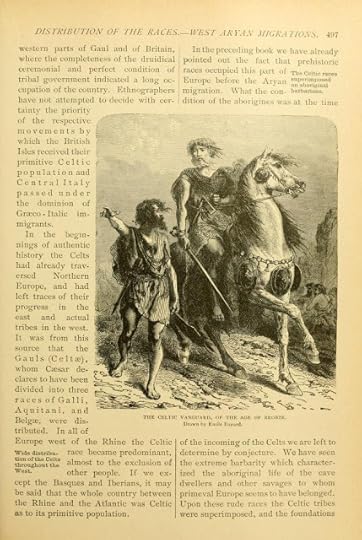

The grim events of the 20th century have taught us to beware of that word ‘Aryan’, liberally scattered in the introduction to many a 19th century collection. Sir George Dasent, introducing ‘Popular Tales from the Norse’ (his translation of Asbjornsen and Moe’s 'Norske Folkeeventyr’) includes a section on ‘the Aryan race’ which according to contemporary anthropological wisdom had spread across Europe ‘in days of immemorial antiquity’. In 1905, citing the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley as his authority, Charles Squire in ‘Celtic Myths and Legends’ writes confidently of ‘certain proof of two distinct human stocks in the British Isles at the time of the Roman conquest’. He describes them: the early people who built Britain’s long barrows were ‘Iberian’ or ‘Mediterranean’ in origin: ‘a short, swarthy, dark-haired’ aboriginal race; but ‘the second of these two races was the exact opposite of the first. It was the tall, fair, light-haired, blue- or gray-eyed people called, popularly, the “Celts”, who belonged in speech to the “Aryan” family … It was in a higher stage of culture than the “Iberians”.’ In the illustration below from a history of the world published in 1897, we see how the heroic Celts were imagined, along with an account of the 'Aryan migration'. And they were supposed to have displaced a different race of indigenous people, driving them almost literally underground.

'The Celtic Vanguard' from 'Ridpath's History of the World', 1897

'The Celtic Vanguard' from 'Ridpath's History of the World', 1897This notion of ‘two races, two cultures’ has been discredited. Archaologists and geneticists now agree that Europe has been a melting-pot of racial groups from at least the early Neolithic. European Mesolithic hunter-gatherers were neither replaced nor suddenly shunted out; instead, over several thousand years, they assimilated both the culture and the genes of a gradually diffusing population of Neolithic farmers. It wasn’t until the Bronze Age (says Professor Barry Cunliffe in ‘Europe Between the Oceans, 9000 BC – AD1000’) that sea-faring and trading populations on the on the coasts of Europe, Britain and Ireland, developed the Celtic tongue as ‘an Atlantic façade lingua franca’. Isn't that wonderful? The Celts didn’t ‘come from’ anywhere: they were in place already. The Celtic languages evolved because coastal peoples travelled and traded and intermarried and talked to one another. Britain wasn't isolated, it was always an integral part of Europe.

So the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould was wrong. There was never a distinctly different race of ‘little dark people’ living on the edges of a conquering population of tall, fair, confident ‘Aryans’. Nothing to give rise to a belief in a ‘hidden folk’ of pixies, dwarfs or elves.

You can see why he liked the idea. It seemed to answer a lot of questions, besides lending to folk-lore a kind of scientific gloss: anthropological ‘truths’ preserved in tales. Many a writer has been honestly misled by it. In Rosemary Sutcliff’s tremendous novel ‘Sword at Sunset’, the Romano-British and nominally Christian hero Artos, fighting off the Saxon invasions in the 3rdcentury AD, takes as his allies ‘the little Dark People of the Hills’, who live half-underground in turf-covered bothies, use poisoned arrows and worship the Earth Mother. Their clan leader, the Old Woman, calls Artos ‘Sun Lord’ and tells him:

‘We are small and weak, and our numbers grow fewer with the years, but we are scattered very wide, wherever there are hills or lonely places. We can send news and messages racing from one end of a land to the other between moon-rise and moonset; we can creep and hide and spy and bring back word; we are the hunters who can tell you when the game has passed by, by a bent grass-blade or one hair clinging to a bramble-spray. We are the viper that stings in the dark –’

And in the same author's if-anything-even-more-magnificent ‘The Mark of the Horse Lord’, the half-Roman half-British ex-gladiator Phaedrus, masquerading as Midir, Lord of the Dalriads (actually a 4th century AD Scots-Irish Gaelic kingdom), lays down his iron weapons to call upon an Old Man of the Dark People who lives like a badger in ‘a tumble of stones and turf laced together with brambles’ with ‘a dark opening in its side’:

[Phaedrus] had heard before of places such as this, where one left something that needed mending, together with a gift, and came back later to find the gift gone and the broken thing mended; it was one of those things no one talked of very much, the places where the life of the Sun People touched the life of the Old Ones, the People of the Hills. Like the bowls of milk that the women put out sometimes at night, in exchange for some small job to be done – like the knot of rowan hung over a doorway for protection against the ancient Earth Magic – like the stealing of a Sun Child from time to time.’

This Old Man is ‘slight-boned … with grey hair brushed back from his narrow brow, and eyes that seemed at first glance like jet beads…’ Sutcliff was writing in the mid-1960s when the ‘two races’ hypothesis was still widely credited: she writes with great imaginative sympathy. I grew up with these stories and it was easy to be swept along by the idea: these Little Dark People, Painted People, remnants of the past clinging to the verge of cultures which had displaced them, were the historical origin of the fairies. I felt sorry for them. Even in Sutcliff’s sympathetic treatment, these imagined, marginalised archaic people are nearly powerless. Their magic – feared though it is – doesn’t really work on the more civilized Sun People. They are spies, not warriors: they creep through the heather with poisoned arrows, killing by stealth. In fact they’re natives, with all the baggage that implies in colonial and post-colonial Britain. They may help the heroes, but they can’t bethe heroes. Their time is past.

Writing in 1913 Baring-Gould doesn’t even allow them the skills to erect dolmens:

They were not, I take it, the Dolmen builders – these are supposed to have been giants because of the gigantic character of their structures. They were a people who did not build at all. They lived in caves, or if in the open, in huts made by bending branches over and covering them with sods of turf. Consequently in folk-lore they are always represented as either emerging from caverns or from under mounds.

This is to lend to folk-lore an authority far beyond its deserts.

Most of the nineteenth century collectors of the fairy tales and folk-lore which we all love so much were driven by nationalist impulses and racial pride. Each sought, as the Grimms did, the pure voice of their own ‘folk’. As the century progressed what they in fact uncovered was the inextricably interrelated nature of European folk- and fairy- lore. Despite the near-impossibility of claiming a particular version of any story as ‘original’, some went on to claim an ultimate ‘Aryan’ heritage for such tales, going so far as to assert that the Aryan master-race originated in Scandinavia – since, clearly, the Nordic peoples were the tallest, blondest and bluest-eyed of the lot. Most of these gentlemen intended only to generate pride in what they saw as their heritage. They did not recognise it as racism - the term had not yet been coined - but racism it was. As folklorists, as lovers of fairy tales, we need to be responsible for the ways we interpret the stories we tell.

While I was researching Mi’kmaq and Algonkin folk-lore for my book 'Troll Blood', I came across a salutary reminder of how untrustworthy some 19thcentury commentators can be when discussing origins: in a compilation called ‘The Algonquin Legends of New England’ (1884) I found the anthropologist Charles G. Leland with a bee in his bonnet about what he claimed had to be a Norse influence on Mi’kmaq stories. Having decided that the Mi’kmaq tales were in effect too ‘noble’ to have been the product of Native American minds, he made the wildly unsupported assertion that the Norsemen must have told stories from the Eddas to the indigenous peoples of what is now Newfoundland and New Brunswick: that the Mi’kmaq culture-hero Kluskap (‘Glooscap’, in his account) ‘is the Norse god intensified … by far the grandest and most Aryan-like character ever evolved from a savage mind’. I almost dropped the book and was forced to regard it ever after as compromised and unreliable. If there was any contact at all between Norsemen and the Native American population in the 10th to 13th centuries (the likely duration of occasional forays from treeless Greenland for much-needed North American timber), the Greenlanders’ Saga suggests that it was violent and short. But that’s not the point. The point is the mindset which says ‘this is too good to have been created by [insert racial group]’.

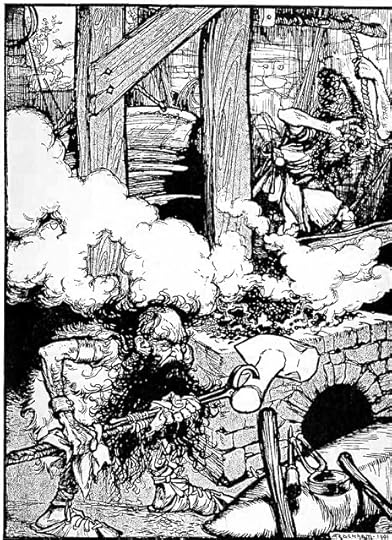

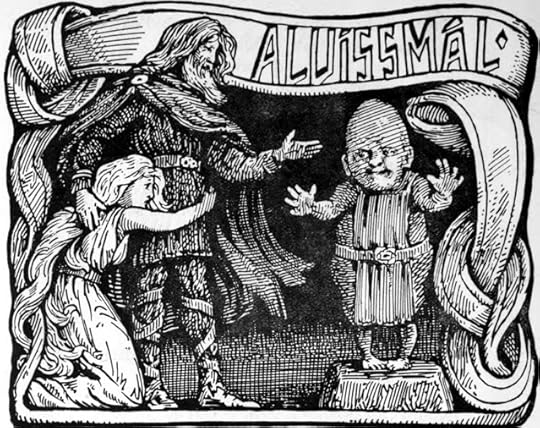

The dwarf Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir.

The dwarf Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir.Returning to the origin of pixies, elves and dwarfs – if they’re not a folk-memory of some once co-existing shy and inferior race, what are they? As Baring-Gould says, the notion must have come from somewhere. Well, Britain, Ireland and Northern Europe are dotted with burial mounds and barrows. The Irish story of the love of Midir for Étain states plainly that Midir is a king of the ‘elf-mounds’, the underworld, and the tale is full of instances of death and rebirth. As I argue more closely in an essay called ‘The Lost Kings of Fairyland’ in my recent book, fairies have long been associated with the dead. In a fascinating essay ‘The Craftsman in the Mound’ (Folk-Lore 88, 1977) Lotte Motz discusses the figure of the dwarf as a smith and craftman dwelling in hills, mounds and mountains, who may be heard hammering away in underground smithies. Pointing to the many instances of ‘legends of dead rulers who reside, sometimes in a magic sleep and often with their retinue, within a mountain’, she continues:

A relation to the dead appears to belong also to the dwarfs of the Icelandic documents; so the dwarf Alviss [‘All-Knowing] is asked by Thor if he had been staying with the dead, and a poem in a saga tells of a doughty sword which had been fashioned by ‘dead dwarfs’. I would… assert that the mountain dwelling of the smith holds, rather than temporary wealth, eternal treasures in its aspect as the mountain of the dead.

As if to emphasise his deathly character, like a ghost fleeing to its grave at cock-crow, the dwarf Alviss (the story is from the Poetic Edda) cannot endure daylight but turns to stone at sunrise.

‘The day has caught thee, dwarf!’ cries triumphant Thor, who like Gandalf in ‘The Hobbit’ has kept him talking…

It's always been thought dangerous to see fairies. Like the Furies in Greek mythology, if you talked about them at all, you used flattering circumlocutions – the Good People, the Seely Court, the People of Peace. They came from the hollow hills, the land of death, and it was wise to be frightened of them. Maybe the visions, the ‘legions of dwarfs’, the little green men or pixies which Baring-Gould and his wife and child separately saw signified something more sinister than folk-memories.

After all, sunstroke can kill you.

Picture credits:

Pixies - John D Batten - Wikimedia CommonsNisse eating barley porridge - Wikimedia CommonsThe dwarves Brokkr and Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir - Arthur Rackham - Wikimedia CommonsAlvissmal - Alviss answers Thor - Wikimedia Commons The Celtic Vanguard - Wikimedia Commons

Dolmen, Jersey, 1859 - Wikimedia Commons

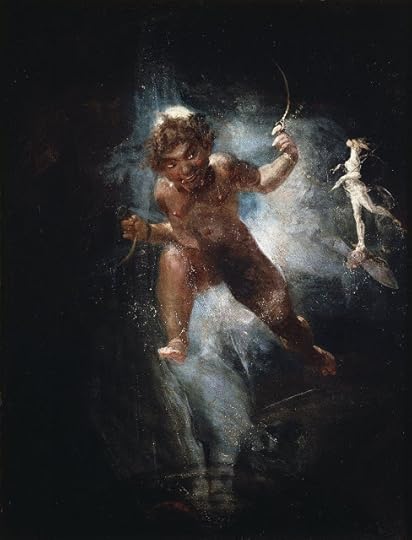

Puck - by Fuseli - Wikimedia Commons

May 13, 2021

On schoolyard rhymes and natural storytelling

In Thomas Gray's beautiful 'Elegy Written in a County Churchyard', he muses over the unknown, uncelebrated talent of the humble country people who lie buried there:

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood.

We tend not to think of ordinary people as particularly eloquent or colourful in their speech. But they often are. Robert Burns was untaught, and John Clare, and many 'mute inglorious Miltons' may, as Gray suggests, have gone to their quiet graves without being appreciated by more than the handful of folk amongst whom they lived.

From such ordinary yet extraordinary folk sprang the great poet Anonymous, without whom we would have no Iliad or Odyssey, no Border ballads, no Thomas the Rhymer or Tam Lin… no fairy tales, no myths, no legends – no Bible – all of which were made up and told aloud by Anon long before they got trapped and written down in big, thick books. Without Anon we’d have no proverbs, no skipping rhymes, no riddles, no jokes. We humans are just naturally good at lively, colourful, poetic speech. We really and truly do not have to be taught how to read and write, still less do we need to be taught the rules of reading and writing – in order to express ourselves.

I was reminded of this by a section in a rather lovely book called ‘Folklore on The American Land’ by Duncan Emrich (Little, Brown & Company, 1972). Here are some extracts.

An exuberant skipping rhyme from a school in Washington:

An exuberant skipping rhyme from a school in Washington:Salome was a dancerShe danced before the kingAnd every time she dancedShe wiggled everything.‘Stop,’ said the king,‘You can’t do that in here.’‘Baloney,’ said Salome,And kicked the chandelier.

And another:

Grandma Moses sick in bedCalled the doctor and the doctor said‘Grandma Moses, you ain’t sick,All you need is a licorice stick.’

I gotta pain in my side, Oh Ah!I gotta pain in my stomach, Oh Ah!I gotta pain in my head,Coz the baby said,Roll-a-roll-a-peep! Roll-a-roll-a-peep!Bump-te-wa-wa, bump-te-wa-wa,Roll-a-roll-a-peep!

Downtown baby on a roller coasterSweet, sweet baby on a roller coasterShimmy shimmy coco popShimmy shimmy POP!Shimmy shimmy coco popShimmy shimmy POP!

Children make these things up! Children!

Because children naturally love the sounds of words and the rhythms they can make with them. A book is an alien thing to many children – an intimidating, unpleasurable thing. Reading can be a difficult struggle that gets them nowhere slowly and makes them feel like failures. Yet they can all tell stories. On a school visit several years ago now, I said to the children, "I've never been into a school that didn't have a ghost story. When I was at school, there was a disused railway station just along the road, and there were tales of a severed hand that crawled around the platform in the broken glass. Nobody ever saw it, of course, but the story was there. All schools have ghosts."

Hands went up. "We have Bloody Mary in the toilets!" two girls remarked. Now Bloody Mary, in this context, is a supernatural being half feared, half delighted in: she lives in mirrors, and if you stare too long into them, she scratches your eyes out. 'There was a ghost at my mum's school,' a boy told me, 'the ghost of a cleaner who got locked in.' "There you are!" I was saying. "You tell these stories though nobody knows who made them, because they're fun to hear. And every now and then some of them do get put into books, BUT – and this is the important thing – they don't COME from books. They come from the real world and from real people."

These kids were a great, lively bunch, in a school that didn't get many author visits, and they enjoyed my talk partly because I did a lot of interactive stuff: riddles, some drama; and told stories from the viking sagas and medieval chronicles. You cannot just waltz into a classroom and start talking to twelve year-olds about elves (even though the book I was there to talk about, 'Dark Angels' is all about elves) because twelve year-olds think of elves as little green-stockinged things with red hats dancing around Christmas trees and making toys. And why would they want to hear about that?

So I'd begin by talking about UFO's, and about people who think they've been abducted by aliens and operated on, and even had their brains removed (like Spock in the old StarTrek episode) - and then I'd tell them a genuinely creepy story from a 13th century chronicle about a young squire, who is abducted by elves and has his brain removed. And I'd try to show them how people have been telling the same kinds of stories for hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years, and how some of these stories can end up becoming woven into the books I and others write.

Anybody can make a story; anybody can tell one. It's a tragedy for children to feel disempowered and divorced from the process of storytelling, because it's one of the things we were all born to do. Trammelling the writing of especially primary school children by marking them on how many adjectival clauses or adverbs or 'wow words' they've used, is a sin. Forget about the wretched fronted adverbials! Stories are meant to be fun! Why should we value the tales children tell one another when they're collected by adults and printed in the Journal of the Folklore Society, yet dismiss them in the playground? I want our children to know that the stories they tell one another are just as real as the ones that get written down in books. And if they know that, perhaps they'll lose their fear of reading and writing them. Returning to Duncan Emlich's book briefly, here from the Ozarks – from the French ‘Aux Arks’, Arks being the shortened form for Arkansas – are a number of wonderfully colourful phrases and turns of speech, all of them coined by ordinary folks:

Of a man who had been stung by yellowjackets: “He was actin’ like a windmill gone to the bad.” (That's comedy!)

In Boone County, Arkansas, a barefoot young farmer to his sweetheart: “The days when I don’t git to see you are plumb squandered away and lost, like beads off’n a string.” (That's a love poem.)

A fat little man with a square head and no neck worth mentioning: “He looks like a young jug with a cork in it.” (Worthy of Dickens!)

In Baxter County, Arkansas, a fellow professed dislike for the Robinson family: “Hell is so full of Robinsons that you can see their feet stickin’ out of the winders.” (Wonderful comic hyperbole, and makes his point.)

And perhaps my favourite: on a very hot day an old woman says: “Ain’t it awful? I feel like hell ain’t a mile away and the fences all down.”

Miltons: the lot of them. Uncelebrated, maybe! But definitely not mute.

May 2, 2021

May Morning in Oxford

This post first appeared on The History Girls blog in 2015, all of six years ago! Judging by the apple blossom, the spring weather must have been warmer that year: today the blossom's only half out. And owing to lockdown, I doubt there were any crowds gathering below Magdalen Tower on May Day morning to hear the choirboys singing madrigals. But this is a happy memory; and maybe, next year...

So on the First of May we got up in the grey twilight at 4.45am and drove into Oxford to listen to the choirboys singing the May in from the top of Magdalen Tower.

The sky was crimson, every moment changing and brightening towards amber and gold. We found a parking place somewhere near the station and hurried up through the town, which was strangely awake for such a time in the morning. Scattered pedestrians striding purposefully. Cyclists creaking by on ancient bicycles. Groups of worse-for-wear students who’d been up all night, noisy, laughing, hugging one another, stumbling along. Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young… All of us heading the same way and for the same reason. Kebab and burger vans on Queen Street were doing a great trade. The air was chill, the buildings still shadowed. Towery city and branchy between towers, cuckoo-echoing, bell-swarmèd, lark charmèd, rook-racked, river-rounded… On the High, a homeless man sat in a college doorway and watched the crowd passing downhill towards Magdalen College and its bell tower.

No one is quite sure, it seems, how old this ceremony is, but it’s been going on for many hundreds of years. Every year at 6am on May Day, the choir of Magdalen College climbs to the top of Magdalen Tower to sing from the roof to celebrate the spring – first the Hymnus Eucharisticus and then English country songs and madrigals.

As the crowd around the base of the tower became thicker, we came to a halt among a happy bunch of May morning sightseers – many in May costumes, crowned with real flowers and greenery. Tipping our heads back, we could just see the white robes of the choir moving between the finials of the tower top, and imagine the scene up there as Holman Hunt depicted it in his painting ‘May Morning on Magdalen Tower’. (Did they really scatter a carpet of flowers for the boys to tread upon?)

It must be the most popular of Oxford’s colourful college traditions. Some are stranger than others. All Souls (full name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed) for example, owns to a custom as weird as anything out of Gormenghast: the Hunting of the Mallard. Once a century, the respectable Fellows of this wealthiest of colleges partake of a feast followed by a crazy ritual in which, led by a ‘Lord Mallard’ carried in a chair, they parade through the college with flaming torches in pursuit of a man carrying a wooden duck tied to a pole. This is to commemorate a huge mallard which, startled by workmen digging a drain, supposedly flew out of the foundations when the college was being built in 1437. Whilst parading, the participants sing the Mallard Song, which dates from about 1660.

The Griffine, Bustard, Turkey & CaponLet other hungry Mortalls gape onAnd on their bones with Stomacks fall hard,But let All Souls’ Men have the Mallard.

Chorus: Hough the bloud of King Edward.By the bloud of King EdwardIt was a swapping, swapping mallard!

I have sometimes wondered if Mervyn Peake knew of this ceremony – and if so, whether it inspired any of Gormenghast’s strange rituals, such as the ceremony to Honour the Poet? Barquentine, Master of Rituals, outlines the requirements to Steerpike. Have the cloisters been painted the correct shade of darkest red? Has the Poet completed his poem? Has he been told about the magpie?

‘I told him that he must rise to his feet and declaim within twelve seconds of the magpie’s release from the wire cage. That while declaiming his left hand must be clasping the beaker of moat-water in which the Countess has previously placed the blue pebble from Gormenghast river.’ ‘That is so, boy. And that he shall be wearing the Poet’s Gown, that his feet shall be bare, did you tell him that?’ ‘I did,’ said Steerpike. ‘And the yellow benches for the Professors, were they found?’

All Souls’ Mallard ceremony was last held in 2001 and so will not be held again until 2101, but the song (which has six verses) is apparently still sung twice a year. I don’t know if the Fellows have re-included the fifth verse which was ‘expunged on grounds of decency’ in 1821 – but most 21stcentury sensibilities will find it enjoyably ridiculous rather than obscene. Anyhow, no one prepared to canter through college after a duck on a pole has any right to complain.

Hee was swapping all from bill to eye,Hee was swapping all from wing to thigh,His swapping tool of generationOute swapped all the winged Nation.

Chorus: Hough the bloud of King Edward.By the bloud of King EdwardIt was a swapping, swapping mallard!

Hunting the Mallard is a ceremony exclusively for the lofty Fellows of All Souls College, but the Magdalen College ceremony is for everyone, town and gown. As we watched, the corner of the tower slowly glowed in the sunrise. The clock chimed six. The crowd, five thousand strong by now, hushed. The chimes faded and the choir at the tower top began to sing. Their voices were amplified – and for a moment, braced as I’d been to listen for the high, clear, distant notes, I was disappointed. Then I realised that it was the only practical solution, given the numbers waiting below. And it was still lovely.

After the Latin hymn, a prayer was read thanking God for the light of morning, remembering St Mary Magdalene and the women who were witnesses to the resurrection of Jesus at the break of day, and praising God’s creation Mother Earth with all her spring flowers. As a happy combination of Christianity and nature worship, it seemed faultlessly medieval. Then the choir sang Thomas Morley's songs ‘Now is the Month of Maying’ and 'My Bonnie Lass She Smileth' – and it was over, the sun was up, and it was time to wander back through the city with the rest of the teeming multitude and find somewhere to eat breakfast. Our attention was caught by someone waving aloft a hand-written placard declaring the existence of ‘Free Bacon Sandwiches at the Wesley Memorial Church on New Inn Hall Street’ – but that seemed too far away from the action.

The thump of a big drum lured us into Radcliffe Square where we found a colourful band playing oddly dirge-like marches on the cobbles around the Radcliffe camera. Then we looped back to the High for an expensive but delicious breakfast of scrambled egg and smoked salmon, bacon rolls and coffee. And one Bucks Fizz, which we shared between us. It was still only 7am.

Merry May!