Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 10

January 7, 2021

Portals: entrances to other worlds (1)

It’s January, the month of doorways and portals: the Roman god Janus presided over beginnings and endings, passages and transitions; his two faces look back to the past and on towards the future. So this month I’m taking a look at some portals in fantasy. How do you get characters from one world into another, and how do writers make us believe it? Even more interesting, how strongly are we intended to believe in those otherworlds beyond the portals, and why are the characters going there? For what purpose? Let's begin with a little girl sitting with her big sister on a bank, when a White Rabbit runs past.

It’s January, the month of doorways and portals: the Roman god Janus presided over beginnings and endings, passages and transitions; his two faces look back to the past and on towards the future. So this month I’m taking a look at some portals in fantasy. How do you get characters from one world into another, and how do writers make us believe it? Even more interesting, how strongly are we intended to believe in those otherworlds beyond the portals, and why are the characters going there? For what purpose? Let's begin with a little girl sitting with her big sister on a bank, when a White Rabbit runs past. There was nothing so very remarkable about that; nor did Alice think it so very much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late!” (when she thought of it afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet… and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and fortunately was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge. In another moment, down went Alice after it…

Moments later she’s falling down very deep well, absurdly lined with cupboards, shelves and maps – falling for so far and so long that it takes two and half pages for her to arrive at the bottom ‘not a bit hurt’, in the antechambers and hallways of Wonderland. Carroll takes us smoothly from the mundane to the incredible by his deadpan story-telling. Nothing’s happening; Alice is bored. A rabbit runs past: ‘nothing remarkable’. The rabbit’s exclamation ‘seems quite natural’. Only at the watch and waistcoat pocket does Alice jump to her feet; by this time we’re snagged, and Alice is so self-possessed that nothing, even falling for miles down a well, perhaps to the very centre of the earth, fazes her. Panic? Not she! She philosophises all the way down: if she can accept it, we can.

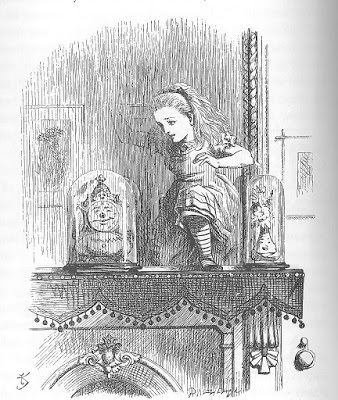

‘Wonderland’ was published in 1865; ‘Through the Looking Glass’ in 1871. In the second book, Carroll employs the same strategy of easing us from the everyday to the strange. Alice opens the way into Looking-glass land herself, towards the end of a five-page fanciful monologue to the black kitten. You remember that it wouldn’t fold its arms properly, and she held it up to the mirror ‘that it might see how sulky it was –

‘and if you’re not good directly,’ she added, ‘I’ll put you through into the Looking Glass-House…

‘Now… I’ll tell you all my ideas about the Looking-glass House. First, there’s the room you can see through the glass – that’s just the same as our drawing room, only the things go the other way. I can see all of it when I get upon a chair – all but the bit just behind the fireplace. Oh! I do so wish I could see that bit. I want so much to know whether they’ve a fire in the winter: you never can tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up in that room too – but that may be only pretence, to make it look as if they had a fire. Well then, the books are something like our books, only the words go the wrong way; I know that, because I’ve held up one of our books to the glass, and then they hold one up in the other room.’

Let’s stop for a moment and reflect (sorry!) on how creepy Alice’s chatter is. She comes up with the disquieting notion that the people who live beyond the glass are not ‘us’, and that they may be out to deceive us. And it isn't her own reflection holding up the book in the mirror, but one of those mysterious others: Alice isn’t tall enough to see her own face in it, so if she holds a book up over her head she sees it reflected, but not who's holding it... This detailed observation of how a looking glass works is enough to convince the reader of its reality, while Alice’s interpretations provide a frisson of the uncanny without being too sinister.

‘Let’s pretend the glass has got all soft like gauze, so that we can get through. Why, it’s turning into a sort of mist now, I declare! It’ll be easy enough to get through – ’ She was up on the chimney-piece while she said this, though she hardly knew how she had got there. And certainly the glass was beginning to melt away, just like a bright, silvery mist.

In another moment Alice was through the glass and had jumped lightly down into the Looking-glass room.

I'm sure this is just how passing through a looking-glass would feel… I once read, I think in an essay by C.S. Lewis, that to have an unusual protagonist in a fantasy world was gilding the lily: too much icing on a very fancy cake. And he cited Alice as an example of an ordinary child to whom strange things happen. But how ordinary is Alice, after all? Is she really just an innocent and rather pedestrian Every-little-girl in a mad, mad world? Or does she have her own brand of illogical weirdness with which to combat the weirdness she finds? I think she does, and we often miss it. We look at the blonde hair, the hairband, the blue dress and the white pinafore, and forget her speculative, inventive mind, her impatience – and passages like this:

And once she had really frightened her old nurse by shouting suddenly in her ear, “Nurse! Do let’s pretend that I’m a hungry hyaena, and you’re a bone!”

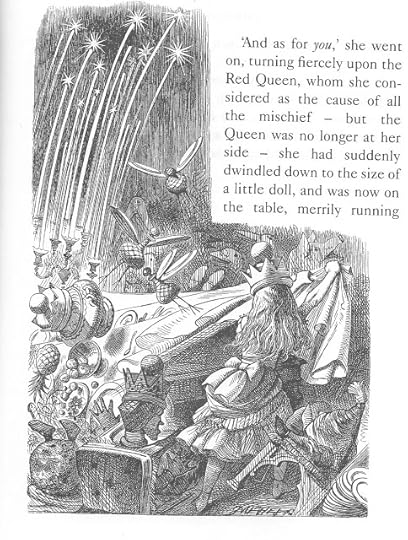

It’s Alice’s weird imagination that takes her into Looking Glass Land: she’s both a credibly strong-minded little girl, capable of defending herself in the White Rabbit’s house by kicking Bill the lizard up the chimney – and a surreal philosopher, as some children are. Herdream-adventures are her own creation, and when they get too chaotic, she ends them – amid considerable violence.

‘I can’t stand this any longer!’ she cried as she jumped up and seized the table-cloth with both hands. One good pull, and plates, dishes, guests, and candles came crashing down together in a heap on the floor.

In each case, Tenniel’s illustrations catch the vivid threat and drama of the situation. Some books with dream endings can feel like a cheat. ‘He woke up, and found it was only a dream’ seems to negate all that’s happened – John Masefield’s ‘The Box of Delights’ is an example. But Wonderland and Looking-glass land were never real. Alice hasn’t strayed into a pre-existing Narnia like Lucy Pevensie. She is the Alpha and Omega of her own worlds: and when she wakes from them, it is utterly logical that Wonderland and Looking-glass land cease to be.

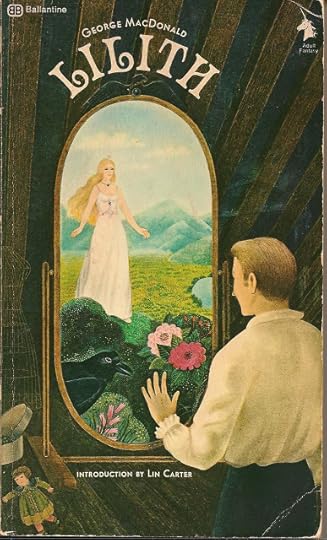

Children and wonderlands are compatible: fictional children usually take passing through a portal very much in their stride. Adults are a different matter. It is interesting to compare the natural ease of Alice’s transit through the Looking-glass with that of Mr Vane, the narrator of George MacDonald’s adult dream-fantasy ‘Lilith’. Written in 1895, it post-dates ‘Alice’, and the character’s transition through a mirror is not into a dreamland but into a ‘region of the seven dimensions’ – the meaning of which has been much discussed – which interpenetrates the ‘real’ world. Like Alice, Vane is in pursuit of someone who leads him to the portal: he follows the spectral figure of an old man, Mr Raven – who sometimes appears in raven form – up the many winding stairs of an old house into a garret room containing nothing but a dusty old mirror.

It had an ebony frame, on the top of which stood a black eagle with outstretched wings, in his beak a golden chain, from whose end hung a black ball.

Looking at rather than into the mirror – as we do too, since the description focuses on the frame and its decorations – Vane suddenly notices that it reflects neither him nor his surroundings. Instead it shows him a wild landscape. ‘[C]ould I have mistaken for a mirror the glass that protected a wonderful picture?’ he wonders

I saw before me a wild country, broken and heathy. Desolate hills of no great height but somehow of strange appearance, occupied the middle distance … nearest me lay a track of moorland, flat and melancholy.

Like Alice on seeing the White Rabbit, Vane is initially ‘no wise astonished’ at seeing an ancient raven hop towards him within the supposed picture. But when he stumbles forward over the frame and discovers himself ‘in the open air, on a houseless heath’, he is confused, shaken and afraid. Looking back he sees nothing comprehensible: ‘all was vague and uncertain’. The raven asks him who he is, and he cannot truly answer. Having stumbled into this strange place he rapidly stumbles out again through a ‘something with no colour’ hanging between trees; back in the garret he hurls himself downstairs in panic, swearing never again to climb ‘the last terrible stair.’ However, definitions of real and unreal are blurred: Vane has not returned to his own world at all and sets out on a spiritual journey to find the true life of heaven. Is this a physical parallel universe with objective reality, or a land of the psyche or spirit? Does he wake at the end of the book, or does he only dream he’s awake? What do such questions even mean…?

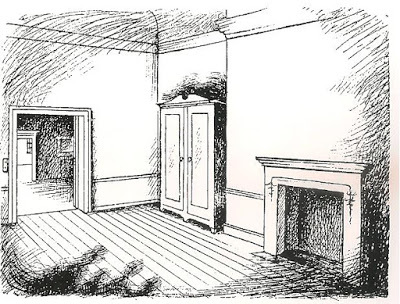

Lucy Pevensie’s passage into the snow-bound Narnian forest through the back of an old wardrobe in an empty room is reminiscent of Vane’s empty garret with its mirror: but Narnia is different from Wonderland and Looking-glass land, or the multi-dimensional visionary world of ‘Lilith’. It has physical existence and continuity: it endures. We see it being created and we see it end.

Lewis is extremely good at portals. He guides us through them, as Carroll does, by carefully describing the physical situation and sensations of passing from world to world. The sleek softness of fur coats gives way to prickly fir branches: ‘the hard, smooth wood of the floor of the wardrobe’ becomes ‘something soft and powdery and extremely cold’… Lucy, while not as in-your-face as Alice, possesses her own quiet confidence: ‘“This is very queer,” she said, and went on a step or two further’, until:

A moment later she found that she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

In every book the way into Narnia (and quite often the way out) is different, and always wonderfully vivid. In ‘Prince Caspian’ the children are dragged into Narnia by Susan’s magic horn. They never hear it – but suffer the effect: an urgent, physical tugging that wrenches them off the station platform and dumps them into a dense thicket. (It would have been terrifying to arrive in Narnia for the first time like this, but with their prior experience of travel between worlds, they can process it.) Then there’s that picture in ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, when the ship and painted waves begin to move and a ‘great, salt, splash’ breaks over the picture-frame. There’s the door in the wall of the school grounds, which opens for Scrubb and Jill at the beginning of ‘The Silver Chair’, and Uncle Andrew’s semi-scientific green and yellow rings in ‘The Magician’s Nephew’. Last of all is the railway accident which hurls Eustace and Jill back into Narnia to help Tirian in ‘The Last Battle’ – and through the ultimate portal of death.

While I was writing this essay it was pointed out on Twitter in a fascinating thread by Daniel Cowper (see @DanielCowper) that the painting of the ship in ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ may owe something to ‘The Story of Kwashin Kogi’ related by Lafcadio Hearn in his ‘Japanese Miscellany’ (1901), which Lewis may well have read. Kwashin Kogi is a Buddhist priest who paints landscapes and depictions of the heavens and hells: at the end of the tale he unfolds a eight-part screen painted with beautiful views of Lake Ōmi. The admiring onlookers notice a tiny boat in the painting, rowed by a boatman. It turns and comes closer and closer

– always becoming larger, – until it appeared to be only a short distance away. All of a sudden, the water of the lake seemed to overflow, – out of the picture into the room, and the room was flooded; and the spectators girded up their robes in haste, as the water rose above their knees.

Kwashin Kogi climbs into the boat. As the boatman rows him away all the water in the room flows back into the picture: he dwindles into it and is never seen again. Could this be the origin of the ‘great, salt splash’ from the Narnian ocean? Maybe, but there’s no way of telling: paintings make obvious portals, and writers do come up with such things independently. John Masefield twice uses a similar type of magic in ‘The Box of Delights’ (1935): in each case, the painting/portal offers an escape from danger. The first time is when Cole Hawlings escapes Abner Brown’s ‘wolves’ by entering the painting of a Swiss mountain that hangs on the wall of Kay’s house, Seekings:

As they stared at the picture, it seemed to glow and open, and to become not a picture, but the mountain itself. They heard the rush of the torrent. They saw how tumbled and smashed the scarred pine-trees were among the rolled boulders…

High up above there, in the upper mountain, were the blinding bright snows, and the teeth of the crags black and gleaming. ‘Ah,’ the old man said, ‘and yonder down the path come the mules.’

A white mule with a red saddle comes trotting out of the painting: the old man swings himself on to its back and rides ‘out of the room, up the mountain path, up, up, up, till the path was nothing more than a line in the faded painting, that was so dark upon the wall. Kay watched him until he was gone, and almost sobbed, “O, I do hope you’ll escape the wolves…” ’

The second instance is when Kay, currently only six inches high and imprisoned with Cole Hawlings in the flooding cellars beneath Abner’s lair at Chester Hills, uses a bit of pencil lead to draw pictures on a piece of notepaper – in particular a picture of a boat with a man sculling her, bringing a bunch of keys to set them free. Cole Hawlings sets the paper floating away on the water, and as ‘bigger waves rushed out of the darkness at them,’ the boat and the boatman Kay drew come to the rescue. Here, the association of ‘living’ paintings, boats, boatmen, and the shocking splash of water does seem suggestive of the Japanese tale.

Not all stories about entering painted landscapes are so comforting. In Catherine Storr’s ‘Marianne Dreams’ (1958) the eponymous heroine, sick in bed, employs a stub of pencil to make a drawing of a house, which she subsequently visits in a series of increasingly disturbing dreams. In ‘Bad Wednesday’ – Chapter 3 of PL Travers’ ‘Mary Poppins Comes Back’ (1935) – young Jane Banks, left on her own in punishment for bad behaviour, hurls her paintbox across the room and cracks the Royal Doulton Bowl on the mantlepiece with its painted scene of three little boys playing horses. ‘I say – that hurt!’ cries a voice, and Jane sees one of the painted boys bending down, clutching his knee in both hands. The boys invite Jane to come and play horses with them: the hurt one, Valentine, pulls her into the Bowl and she’s suddenly in a wide sunlit meadow.

William and Everard, tossing their heads and snorting, flew off across the meadow with Jane jingling the reins behind them. … On ran the horses, tugging Jane after them, drawing her away from the Nursery.

Presently she pulled up, panting, and looked back over the tracks they had made in the grass. Behind her, at the other side of the meadow, she could see the rim of the Bowl. It seemed small and very far away. And something inside her warned that it was time to turn back.

‘I must go back now,’ she said, dropping the jingling reins.

‘Oh, no, no!’ cried the Triplets, closing round her. And now something in their voices made her feel uneasy…

But she goes on through a dark alder wood to their cold, threatening house, where she meets their sister, and sinister grandfather, and hears that the three boys ‘have been watching you for ages! But they couldn’t catch you before – you were always so happy!’ She is to stay here for ever and never go home. As they surround her, Jane screams for Mary Poppins in sheer terror – and is finally rescued.

As a child I absolutely loved this very dark story, and I still do. It’s closer to George MacDonald’s work than Lewis’s or Masefield’s, and it’s far from Lewis Carroll’s, whose Alice never needs rescuing. Jane travels through the portal of the Doulton Bowl on a psychological vector from rage and defiance, via fear and abandonment, to rescue and reassurance. Even though the next morning, Mary Poppins’ checked scarf can be seen lying on the painted grass of the Doulton Bowl, I don’t think PL Travers means it to signify that the world in the Bowl is real – but Jane’s emotional experience is. In ‘Bad Wednesday’ Jane learns how frightening and alienating losing your temper can be – like being taken over by a stranger within you. Once Mary Poppins has answered her call for help, and comforted her in her sharp, no-nonsense way, Jane relaxes:

A tide of happiness swept over her. ‘It couldn’t have been I who was cross,’ she said to herself. ‘It must have been somebody else.’

And she sat there wondering who the Somebody was…

Alice apart, children in fantasies tend to be sent or called into imaginary worlds for purposes, which may be practical or moral or both. Jane, as we’ve seen, learns a lesson about the dangers of wilful tantrums. With Aslan’s assistance, Lewis’s children variously defeat the White Witch, dethrone the Telmarine King Miraz, rescue Prince Rilian and King Tirian and so on, but there’s another purpose that transcends physical adventures. We’re meant to understand that the children’s relationship with Aslan is precious in itself; to love him is to love Christ, leading to spiritual development and ultimate salvation. (How far this really works depends on the character and the book. Digory’s is the most moving emotional journey; Eustace’s the most character-changing. Edmund’s salvation, wonderfully delivered, really only transforms him into a decent sort of chap like Peter, and Peter is the least interesting of them all: he certainly never exhibits the touching clumsiness and frailty of his Gospel namesake.)

‘The Phantom Tollbooth’ by Norton Juster (1961) is often compared with Carroll’s books because Juster shares with Carroll an inventive delight in puns, puzzles and the light fantastic. Milo, far more bored and discontented than Alice, receives a mysterious parcel labelled ‘For Milo, who has plenty of time’ and unpacks it to discover ‘One Genuine Turnpike Tollbooth’ with associated signs, fare, map and directions. He assembles the Tollbooth and drives past it in his toy car to find himself ‘speeding along an unfamiliar country road’ with ‘neither the tollbooth nor his room nor even the house’ anywhere in sight. It’s the specificity of the Tollbooth’s construction that makes this easy to believe:

Following the instructions, which told him to cut here, lift there and fold back all around, he soon had the tollbooth unpacked and set up on its stand. He fitted the windows in place and attached the roof, which extended out on both sides, and fastened on the coin box. It was very much like the tollbooths he’d seen on family trips, except of course it was much smaller and purple.

Most of us have done this kind of thing as children or parents (often cutting out designs on the backs of cereal packets) and with the Tollbooth firmly established in our imaginations, we willingly accept the rest. Off Milo drives through the wonderful Kingdom of Wisdom, to visit the cities of Dictionopolis and Digitopolis ruled by the estranged brothers, King Azaz the Unabridged and the Mathemagician, and rescue the Princesses Rhyme and Reason from the Castle in the Air in the Mountains of Ignorance. By the time he returns he doesn’t need the Tollbooth any more, for he’s learned to appreciate life and all it offers.

There was so much to see, and hear, and touch – walks to take, hills to climb … voices to hear and conversations to listen to in wonder, and the special smell of each day.

And ... there were books that could take you anywhere, and things to invent and make and build and break, and all the puzzle and excitement of everything he didn’t know – music to play, songs to sing, and worlds to imagine and some day make real.

Milo’s adventures are such fun, and so charming, that readers are carried along with the enchantment. We positively enjoy the lessons: after all, that ‘knowledge is delightful’ is the whole point of the book, but is the Kingdom of Wisdom ‘real’, or a dream like Wonderland? It may be more than a dream, since Milo’s journey enables him to recognise knowledge and wisdom in real life – but it’s a lot less real than Narnia.

Join me in venturing through more portals in my next post.

Picture credits:

'Alice found herself falling...' illustration by W H Walker, 1907

Alice passes through the Looking Glass - three illustrations by Tenniel

Cover of 'Lilith' by George MacDonald, Ballantyne Books 1971, artist unknown

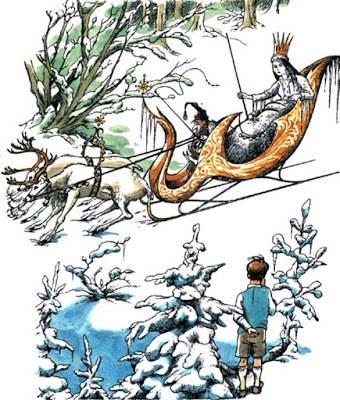

The Wardrobe, 'The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe' - illustration by Pauline Baynes

The Doulton Bowl, 'Mary Poppins Comes Back' - illustration by Mary Shepard

Milo and the Tollbooth, 'The Phantom Tollbooth' - illustration by Jules Feiffer

December 21, 2020

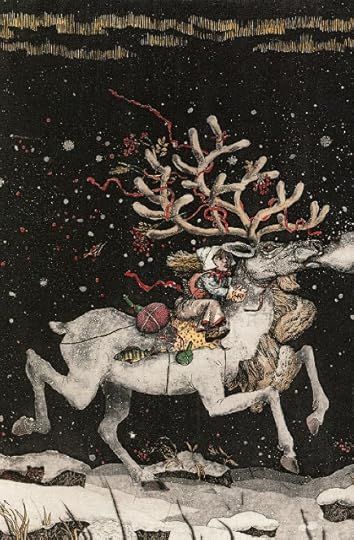

Flying Reindeer, Little Gerda, and the different histories of Father Christmas and Santa Claus

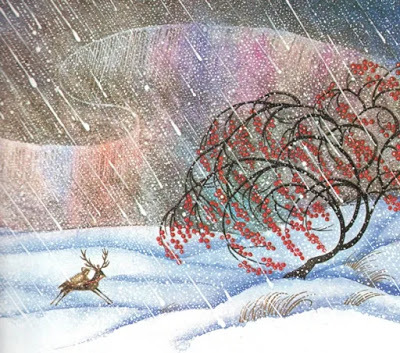

Re-reading Hans Andersen’s ‘The Snow Queen’ recently, I noticed how in this lovely illustration by Errol le Cain the reindeer turns its antlered head to watch as the Snow Queen stops to lift little Kay into her sleigh. In contrast to the Queen’s smile of welcome (as she opens her fur cloak to envelop Kay), the reindeer’s expression is narrow-eyed, even predatory. Then taking a closer look at the text I realised that in fact Andersen never specifies what animal – if any – draws the Snow Queen’s sleigh. In no matter what translation, the story only says:

One day, while the boys were playing, a great white sleigh came into the square, driven by someone in a thick fur coat and white fur hat. Kay quickly tied his little sled to the big sleigh and began to ride behind. They went faster and faster, out of the square and … out of the city gates. Kay was afraid and managed to loosen the rope at last. It was no good – the little sledge still sped after the big one; they flew like the wind.

‘They flew like the wind…’ but did they actually fly? I have always assumed they did, but the story doesn’t say so. Then, what about the reindeer little Gerda rides, the one given to her by the robber girl to take her north, and north, and further north? ‘Faster and faster the reindeer ran, day and night alike. The ham and the loaves came to an end – and then they were in Lapland.’ From Lapland the pair run on to Finland, and from there ‘the reindeer ‘ran till he came to the bush with the red berries, and there he set Gerda down’ near the Snow Queen’s palace.’ Nowhere does it say he flew – but surely such a long and magical journey could only be accomplished so swiftly by flight?

In his wonderful book ‘Reindeer People: Living with Animals and Spirits in Siberia’ (Harper Perennial, 2005) Piers Vitebsky introduces us to the Eveni people whose ancestors migrated from north-east China ‘and spread for thousands of miles across forests and tundra, swamps and mountain ranges, from Mongolia to the Arctic Ocean, from the Pacific almost to the Urals, making them the most widely spread indigenous people on any landmass.’ The animal that made such an immense distribution possible was the reindeer: and Vitebsky, an anthropologist who spent twenty years visiting, living and travelling with a small community of the Eveny people, goes on to describe the significance of this animal: the power of reindeer transport goes far beyond terrestrial journeys. In the 1980s, Vitebky listened as Nomadic elders of the people told his Eveny friend Tolya that:

Reindeer were created by the sky god Hövki, not only to provide food and transport, but also to lift the human soul up to the sun. From their childhood, seventy, eighty or more years before, they remembered a ritual that was carried out each year on Midsummer Day, symbolising the ascent of each person on the back of a winged reindeer.

The elders told how in the ‘white night’ of the Arctic summer a rope would be stretched between two trees to signify a gateway to the sky, and as the sun rose the gateway would be filled with aromatic smoke from two bonfires. The people would circle the fires, anti-clockwise to symbolize the death of the old year, then clockwise to celebrate the birth of the new one: prayers would be said for success in hunting, increase of the reindeer herds, and healthy children. ‘Then each person was said to be borne aloft on the back of a reindeer to a land of happiness and plenty near the sun.’

Vitebsky explains that ‘the association between reindeer and flying is very ancient – much, much older than European or American ideas about Santa Claus.’ More than 3000 years ago, across the steppes of western Mongolia, people were erecting ‘reindeer stones’ either to mark graves – ‘kurgans’ – or else places of ritual celebration and sacrifice. These stones are carved with representations of various animals: the reindeer being far the most frequent.

Sometimes the deer’s antlers hold a sun-disc, or ‘a human figure with the sun as its head.’ Over a period of about 500 years the reindeer carvings grew more elaborate: their legs stretch into a galloping leap, their bodies are elongated, and they have long flowing antlers whose prongs develop into the beaked heads of birds.

In a fascinating work ‘Fantastic Beasts of the Eurasian Steppes’, Petya Andreeva of the University of Pennsylvania says it’s possible to track over time how the representation of the reindeer travels ‘out of Northern Mongolia and the Transbaikal … in the direction of Pazyryk valley and the larger Altai region’, undergoing significant changes along the way. ‘The composition of fantastic flying deer diminishes its presence on carved monuments above ground as it reached the Sayan-Altai area, only to find a new life in portable goods which furnish underground burial spaces such as the frozen kurgan mounds of Pazyryk’. Here, the flying deer motif appears (along with other hybrid animals) on furnishings, head-dresses and textiles, and tattoos on the bodies of those interred – all preserved by the water which filled the graves and turned to ice. You can see drawings and photos of the tattoos at this link from The Siberian Times'

The Pazyryk burials date from 500 BC, Vitebsky tells us, but the climate was becoming too dry for reindeer to survive there. However, the animal:

… persisted in the imagination like a mythic or archetypal creature. By the second century AD one of the horses sacrificed in a grave wears a face-mask made of leather, felt and fur and adorned with life-size antlers [see above], clearly dressed up to imitate a reindeer. It seems a reindeer was still better than a horse for riding into the afterlife. Some 1500 years later, in the 17th century … a Mongolian chronicle tells us that the wife of the Kham Daldyn Bashig Tu rode into battle on ‘a reindeer with branching antlers.’ Since real reindeer had been absent from this region for 2000 years, this probably indicates a continuation of the custom of dressing a horse in a reindeer mask.

Is it pure coincidence that Santa Claus drives a sleigh drawn by flying reindeer? The answer is yes; there is no connection at all. Nor was St Nicholas, who is of course the origin of Santa Claus, though there is no historical evidence for his existence - associated with reindeer or with any other kind of deer. In ‘The Book of Christmas Folklore’ (Seabury Press, 1973) the American folklorist Tristram Potter Coffin (great name!) says there’s no doubt that the 17th century Dutch brought their tradition of the arrival of St Nicholas on December 6 to 'Nieuw Amsterdam', as New York then was. But by the 1820s the saint had been transformed into Santa by the author of the poem we usually call 'The Night Before Christmas' and by the German-born illustrator Thomas Nast. The former is usually considered to be Clement Clarke Moore, but Professor Coffin argues entertainingly that the credit should go to ‘a sometime Major in the Revolution … Henry Livingston Jr, 1748-1828’. Whoever wrote it, the poem provided Santa with a sleigh drawn by reindeer - in place of the white horse and wagon in which he had previously travelled. Thomas Nast popularised the image, producing an annual portrait of the ‘jolly old elf’, but as a staunch Republican and abolitionist, he often utilised it for propaganda.

In this engraving of 1863, in the two roundels we see a wife praying for her husband, a Civil War soldier, while in the upper right corner Santa’s sleigh visits the camps and alights on a house roof to the left. Nash went on producing Santa portraits until 1886: here's his Merry Old Santa Claus of 1881, in which Santa wears an army backpack to draw attention to a campaign for higher wages for soldiers.

In this engraving of 1863, in the two roundels we see a wife praying for her husband, a Civil War soldier, while in the upper right corner Santa’s sleigh visits the camps and alights on a house roof to the left. Nash went on producing Santa portraits until 1886: here's his Merry Old Santa Claus of 1881, in which Santa wears an army backpack to draw attention to a campaign for higher wages for soldiers.

As Arctic exploration gripped the imagination of the country, Nash situated Santa’s home at the still unvisited North Pole - thereby closing the circle to meet the flying reindeer of ancient Siberia of which neither he nor the poet could have had the slightest notion.

However! In Britain we have Father Christmas not Santa Claus: and Father Christmas has an entirely different history from his American counterpart. For a start, he has no connection with St Nicholas. Rather, he is a spirit or personification of the festive season: on St Thomas’s Day (then held on December 21st, the winter solstice) a man dressed as ‘Father Yule’ would ride through the city of York carrying a loaf of bread and a leg of lamb, until the custom was suppressed in 1572 by an annoyed Archbishop. We’re not told what Father Yule rode on, or drew him along: but see below. In masques and entertainments throughout the Tudor period, a ‘Captain Christmas’ or a ‘Sir Christmas’ might appear, and in a court masque of 1638 in which Shrovetide and Christmas vie for precedence, Christmas appears as ‘an old reverend Gentleman in a furr’d gown and cap’ who proclaims ‘I am the King of good cheere and feasting, though I come but once a yeare to raigne over baked, boyled, roast and plum-porridge…’

During the Interregnum following the English Civil War, the Puritans did their best to suppress Christmas, which – or whom – they portrayed as a popish relic. In a pamplet of 1658, ‘The Triall and Examination of Old Father Christmas’ (the earliest recorded use of that version of his name) the author Josiah King defends Christmas and the jury acquits. This was bold, for the restoration of the monarchy was still two years in the future. It seems to have taken Christmas a couple of centuries fully to recover from the Puritan suppression: when he does turn up again, he rides on a goat. In 1836 Thomas Hervey, later editor of the Athenaeum, wrote in 'The Book of Christmas’ how:

Old Father Christmas, at the head of his numerous and uproarious family, might ride his goat through the streets of the city and the lanes of the village, but he dismounted to sit for a few moments by each man’s hearth…

The illustration by Robert Seymour shows Father Christmas in a fur gown, crowned with holly and riding a goat. Apart from the unsettling way in which both he and the goat are regarding us (to say nothing of the bodiless head tucked under his arm) Seymour's Old Father Christmas is a clear influence on the classic illustration of the Ghost of Christmas Present, crowned with holly and wearing a furred gown – green like that of the Green Knight, another winter spirit – surrounded by a feast complete with plum pudding and wassail bowl.

And of course the Yule goat takes us right back to pagan times again. The Norse god Thor rode in a chariot pulled by two goats, which he could slaughter, devour and restore to life. Another goat, Heiðrún, stands on the roof of the gods’ hall Valhalla, nibbling the leaves of the tree Læraðr (which may be another name for Yggdrasil, the World Tree). Her udders run with mead which collects in a basin beneath her. A deer is her companion, the hart Eikþyrnir; he bites the branches while his horns drip water that is the fount of all rivers. As you can see in this charming 18th century illustration, these are clearly life-giving animals. (I love the flag with VH for Valhalla on the peak of the hall.)

Could there be any connection between the goat upon which Father Christmas rides, the goats which pull Thor’s chariot, the goat on the roof of Valhalla – and the flying reindeer of the Siberian shamans? Probably not, even if goat and reindeer are both semi-domesticated horned animals, both valued for transport and food, both connected with the otherworld... but – it’s worth pondering. Happy Christmas! Merry Yule!

Picture credits:

The Snow Queen, by Errol le Cain

Gerda and the Reindeer, by Boris Diodorev

Deer stones from Uushiglin-uver in the Mongolian province of Khövsgol -Wikipedia

A gilded wooden figurine from the Pazyryk burials, c. 5th century BCE - Wikipedia

Griffin holding in its jaws a reindeer whose antlers are tipped with beaked bird-heads: Pazyryk, late 4th - early 3rd century BCE. Huntingdon Archive for Buddhist and Related Art.

Mask with antlers for a horse's head:Pazyryk Barrow No. 1(excavations by M.P. Gryaznov, 1929). Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Santa Claus - two images by Thomas Nast, plus article: Smithsonian Magazine

Father Christmas in fur gown, crowned with holly and riding a goat - by Robert Seymour, British Library

The stag Eikþyrnir and the goat Heiðrún on top of Valhalla: Icelandic Manuscript, SÁM 66, Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies

Gerda and the Reindeer: from The Snow Queen - by Errol le Cain

December 17, 2020

Tales from the Elf-mounds of Ireland (3)

In a fascinating, closely argued book ‘In Search of the Irish Dreamtime’ (Thames and Hudson, 2016) archaeologist and linguist J P Mallory examines the suggestion that Irish mythological cycles preserve some memories and practices of the Irish Bronze or Iron Ages. He concludes (spoiler alert) that there is little or no evidence for this - and that early medieval clerks mostly back-projected legends on to these highly visible, mysterious monuments. The mound of Brú na Bóinne/Newgrange, for example, appears in the Tochmarc Étaine (The Wooing of Étain) as the palace of Oengus, foster-son of Midir, ‘king of the elf-mounds of Ireland’, but of course the mound of was never any kind of palace.

There is however one suggestive detail. Midir, this prince of the Sidhe, comes to Bru na Bóinne to ask his foster-son for a gift, and Oengus offers him the most beautiful woman in Ireland, Étain, for his wife. The story soon becomes very complicated: Midir’s original wife Fúamnach is understandably jealous. She transforms Étain into a purple, singing fly which lives for a thousand years before falling into a cup of wine, where it is swallowed by another woman who subsequently gives birth to Étain Mk II. (The accidental swallowing of small living things - insects or worms or even grains of wheat - causing pregnancy and birth or rebirth, is a recurrent theme in Celtic mythology.) The reborn Étain is then married to Eochaid king of Tara, and the immortal Midir, still in love with her, has to perform a number of what might well be termed Herculean tasks in order to win permission from Eochaid to embrace her. One of these tasks is to build a causeway over a bog called Móin Lamraige which no one had ever been able to cross.

¶8] After that, clay and gravel and stones are placed upon the bog. Now until that night the men of Ireland used to put the strain on the foreheads of oxen, (but) it was seen that the folk of the elfmounds were putting it on their shoulders. Eochaid did the same, hence he is called Eochaid Airem - or ploughman - for he was the first of the men of Ireland to put a yoke upon the necks of oxen. And these were the words that were on the lips of the host as they were making the causeway: ‘Put in hand, throw in hand, excellent oxen, in the hours after sundown; overhard is the exaction; none knoweth whose is the gain, whose the loss, from the causeway over Móin Lámraige.’ There had been no better causeway in the world, had not a watch been set on them. … Thereafter the steward came to Eochaid and brings tidings of the vast work he had witnessed, and he said there was not on the ridge of the world a magic power that surpassed it.

The Wooing of Etain, tr. online at https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T300012/index.html

This legendary causeway is similar to the great Iron Age timber causeway running out into Corlea Bog which was discovered in the 1980s during mechanical peat excavation. The timbers were dated by dendrochonology to 148 BC, and the construction took no longer than a single year. The causeway ended at a small island and is thought to have been made for a ritual purpose: it's estimated to have used the wood of three hundred oak trees: a thousand wagonloads of cut wood. Maybe the Sidhe were involved! JP Mallory points out that since “the bog swallowed up the trackway soon after it was constructed,” no tale-teller of a thousand years later would have been able to “generate a contemporary account of its construction.” And he therefore concludes that “it would be churlish not to accept … the argument that that the tale does retain remembrance that once a magnificent road had been built to cross a specific bog.”

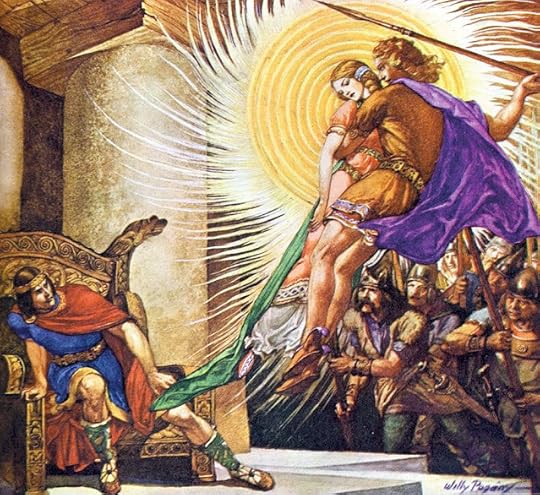

The millenium-long love story of Étain and Midir ends happily for them, if not for poor King Eochaid. When Midir finally succeeds in holding Etain in his arms, the two of them fly up through the rooflight in the shape of two white swans.

Picture credits

The Corlea Trackway in County Longford, Ireland, 2009 (a reconstruction): Kevin King at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corlea_Trackway

Midir and Etain flying up out of Eochaid's hall: “The Frenzied Prince, Being Heroic Stories of Ancient Ireland” 1943. Illustration by Willy Pogány

December 10, 2020

Tales from the Elf-Mounds of Ireland (2)

This is a side view of the magnificent passage grave of Brú na Bóinne or Newgrange, in Co. Meath, Ireland, explained in later legend as the palace of Oengus, foster-son of Midir, king of the Sidhe, lord of the elf-mounds of Ireland. The facade has been restored, and the restoration has raised eyebrows in various quarters; in fact when things gets really nasty the word 'Disneyfication' is thrown around - but when we visited in 2018, personally I rather appreciated the attempt to try and give the visitor some idea of the way the place used to look. Or might have looked.

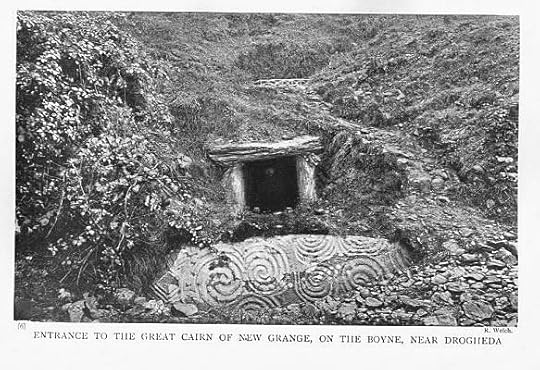

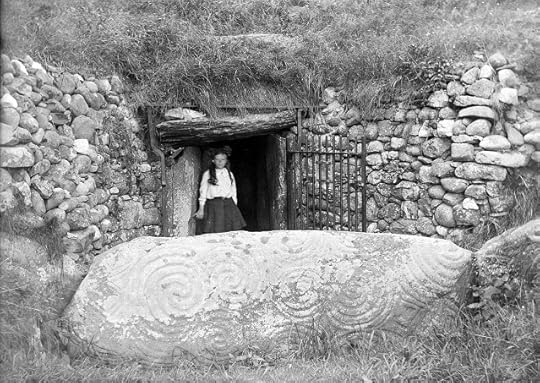

It's not as though we'd inherited a pristine site to begin with. The exterior of the great mound had suffered much damage in the past. It was dug into during the 1600s, and by the early 19th century a folly had been built close to the site, using stones taken from it (it's still there). By the late 19th century the entrance of Brú na Bóinne looked like this. (My God, look at those spirals!)

By the early 1900s some of the debris and earth had been cleared away and it looked like this:

Between 1962 and 1975 the site was excavated by Professor Michael J. O'Kelly, who decided to reconstruct the facade of the monument from the collapsed stones lying at its base: an intriguing mixture made chiefly (here I quote from Wikipedia) of "white quartz cobblestones from the Wicklow Mountains about 50 km to the south." But there were also "dark rounded cobbles from the Mourne Mountains about 50 km to the north; dark gabbro cobbles from the Cooley Mountains; and banded siltstone from the shore at Carlingford Lough." Noting where the stones had fallen, Professor Kelly looked at how the ratio of white quartz to dark cobblestones changed along the facade, and restored it according to his own impressions of how it might have appeared. I particularly like the gradation from dark at the far edges, to white in the middle.

Here's a close-up of the whiter part, studded with those round dark 'statement' boulders.

It's been much hated. In 1983 the French archeologist Pierre Roland Giot said it looked like "cream cheesecake with dried currants distributed about" while more recently the tv archeologist Neil Oliver has criticized as "a bit overdone, kind of like Stalin does the Stone Age". Maybe so... especially since the stones of the new wall have been set in reinforced concrete. "Another theory is that some, or all, of the white quartz cobblestones had formed a plaza on the ground at the entrance." Who can say? As a Yorkshirewoman I have a lot of respect for the dry-stone-walling techniques of our ancestors. Today however, the entrance looks like this (see below) and those dark cut-outs on either side, faced in black stone, are unashamedly modern, making room for the steps by which visitors can come and go - serving the practical purpose of protecting the vast carved stone in front of the doorway from people who might otherwise scramble over it.

I know what Neil Oliver means, though... but however the stones were once arranged, their presence is still impressive, and the vast kerbstones which rim the foot of the mound are in their original places. Just protected from rainfall erosion here and there. Here's myself and my husband, book-ending one of them.

If the impressive, restored exterior leaves doubts as to its authenticity, the interior has not been touched. The stone-lined passage into the mound (where amateur photography is forbidden), and the amazingly high, corbelled chamber like the inside of a witch's hat, with its intricate spiral and chevron carvings, and the two huge stone dishes laid in the side chambers - these remain just as they were in prehistory, as incredibly moving as they must always have been.

The marvellous website Voices from the Dawn tells how when Professor O’Kelly began the excavation in the early 1960s he became aware of a recurrent local tradition that the sunrise used to light up the triple-spiral stone at the end recess far within the tomb. Professor Kelly wondered, having recently uncovered Newgrange’s unusual ‘roof-box’ - that rectangular aperture you can see in the photo above the entrance - whether it had been intended to admit the light of the rising sun. He tried it out at the winter solstice on 1967, and two years later repeated the experiment:-

"At exactly 8.54 hours GMT the top edge of the ball of the sun appeared above the local horizon and at 8.58 hours, the first pencil of direct sunlight shone through the roof-box and along the passage to reach across the tomb chamber floor as far as the front edge of the basin stone in the end recess. As the thin line of light widened to a 17 cm-band and swung across the chamber floor, the tomb was dramatically illuminated and various details of the side and end recesses could be clearly seen in the light reflected from the floor. At 9.09 hours, the 17 cm-band of light began to narrow again and at exactly 9.15 hours, the direct beam was cut off from the tomb. For 17 minutes, therefore, at sunrise on the shortest day of the year, direct sunlight can enter Newgrange, not through the doorway, but through the specially contrived slit that lies under the roof-box at the outer end of the passage roof.”

Since the light-box had been blocked with stones, and covered for many centuries with the collapsed walls of the mound (see the early black and white photos above) no one could possibly have seen this effect in modern times until the professor uncovered it.

This, then, may be a very old memory indeed.

Quartz stone and round river boulders

Quartz stone and round river boulders Photos copyright Katherine Langrish except for the two black-and-white ones which can be found on the Wikipedia entry for Newgrange

December 4, 2020

Tales from the Elf-Mounds of Ireland (1)

A couple of years ago, on our way to visit a friend in Ireland's County Donegal, we broke the journey by staying a couple of nights in the Boyne Valley, home to some of the most impressive Neolithic monuments anywhere in the world. Brú na Bóinne, also known as Newgrange, and its companion mounds Knowth and Dowth are stupendous megalithic passage graves dating to around 3,300 BC, hundreds of years older than the earliest Egyptian pyramid.

We struck lucky: the place we stayed turned out to be a beautiful old house with lovely views next door to the great mound of Dowth: and I mean next door – the mound towered right up over the garden fence; we could go out before breakfast or last thing in the evening with our dog Polly and walk around it and over it and have it completely to ourselves. Dowth, or Dubad, is not a tourist site like its companion tombs, Knowth and Newgrange. No shuttle buses visit it. There is a huge crater at its centre, the result of the local landlord blasting a hole in it with dynamite sometime in the 19th century. If he hoped to find treasure, he was disappointed. But the mound was so massive and so well built that even the explosion did not damage either of the two passage graves deep within. Here's one of the two entrances, with Polly nosing around to give it scale: in the foreground is one of the huge carved sill-stones which edge the entire perimeter of the mound. This one is carved with spirals.

You can't go in; there's a locked iron gate. I tried to take a picture through it, and maybe you can just make out the passage running back into the mound towards the inner chamber.

We walked over and all around the mound. One of the great kerb-stones is carved with seven suns; the picture I took didn't come out too well:

... but there's a lovely Youtube timelapse of it taken during a winter sunrise by Anthony Murphy of the blog Mythical Ireland:

Of course there is a legend about this amazing place: the story goes like this. Long ago in the time of a king called Bressal Bó-dibad, a plague struck down all the cattle of Ireland until at last there were only eight left, one bull and seven cows. (The second part of the king’s name means ‘lacking in cattle'.) So Bressal Bó-dibad decided to build a tower ‘like the Tower of Nimrod’, so that he could pass into heaven. Who knows what he meant to do there? Challenge God to restore his cattle? The tale doesn't say, but men from all over Ireland came to help him build the tower – the mound, that is – but there was a condition: the work must be completed within a single day. So the king’s sister told him that she would ‘stay the sun's course in the vault of heaven, so that they might have an endless day to accomplish their task’. She worked her magic and the sun halted in mid-sky, as it did for Aaron and Moses in the Bible. But Bressal Bó-dibad went after his sister and committed incest with her; he raped her. Then her spell was undone, darkness fell and the men of Ireland abandoned their work. And the king’s sister cursed the mound, saying: 'Dubad [darkness] shall be the name of this place for ever.'

If that doesn’t give you the shivers, I don’t know what will. And then to find the stone with the seven suns, half buried in the grasses… well!

You can read more about the legend and the mound at Anthony Murphy’s blog Mythical Ireland, here: http://blog.mythicalireland.com/2016/06/dowth-and-story-of-hunger-ancient.html

November 26, 2020

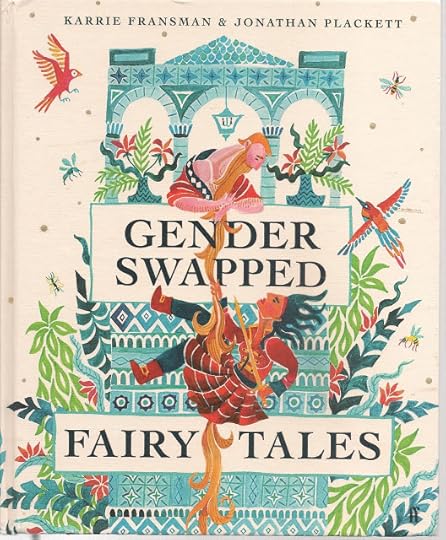

'GENDER SWAPPED FAIRY TALES': a review

In this sumptuous book (published by Faber) wife-and-husband team Karrie Fransman and Jonathan Plackett have chosen twelve classic fairy tales, and flipped the genders of all the characters. As they explain in their introduction:

Fairytales are the ideal genre to gender swap. They are some of the earliest stories we are exposed to as children and form the very building blocks of story-telling. … Most importantly they teach us the difference between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ and about the moral codes that govern our society: that boys should bravely scale giant beanstalks to claim what is rightfully theirs, or that little girls should be wary of talking to strangers in dark woods.[…] However, if we can imagine a world where harps sing and rats transform into coachmen, can we not … also imagine a world where kings want kids and where old women aren’t witches?

I approached the book with a mixture of interest and trepidation. It has long been my mission to try and correct the misapprehension so many people unfortunately have, that fairy tales are all about insipid princesses asleep in towers waiting for true love’s kiss. There are shedloads of fairy tales about bold, active, witty young women and passive, forgetful or foolish young men; in fact I’ve recently compiled a series of thirty such tales which you can visit at this link. But the fairy tales we know best, the ones Disney has made so popular, do tend to depict the type of gentle, patient heroine which suited the social preferences of 19th century editors. So for example the ‘Cinderella’ of most children’s fairy books is the beautiful, long-suffering, forgiving heroine of Charles Perrault’s version, not the Grimms’ more active, headstrong one.

Of the twelve well-known tales which Fransman and Plackett have chosen for their gender-flipping experiment, some are more successful than others. ‘Cinder’ – based on Perrault’s version of ‘Cinderella’ – works remarkably well, since the ambiance is that of the 17th century salons, where to appear suitably dressed, fashionable young gentlemen might spend a great deal of time and money. Here we find Cinder’s two step-brothers preparing for the Queen’s daughter’s ball:

‘For my part,’ said the eldest, ‘I will wear my red velvet suit with French trimmings.’

‘And I,’ said the youngest, ‘shall have my usual pantaloons: but then, to make amends for that, I will put on my gold-flowered cloak, and my diamond chest-piece, which is far from being the most ordinary one in the world.’

They sent for the best tire-man they could get to make up their head-dresses and adjust their neckerchiefs, and they had their red brushes and patches from Monsieur de la Poche.

The authors deliberately have not rewritten these tales, which are faithfully based on those in the Langs’ Blue, Red and Yellow Fairy Books. Gendered articles of clothing are flipped: ‘petticoat’ becomes ‘pantaloons’, for example. ‘Wigs’ might have been a better swap for the original ‘head-dresses’: but the tale’s emphasis on fashion and civility works well for Cinder the aspiring young gentleman. It was a wise choice to go for Perrault’s version and not the Grimms’, with its wilder heroine and more vengeful ethos.

A few of the other tales don’t work quite so well. Almost nothing happens when ‘Hansel and Gretel’ becomes ‘Gretel and Hansel’, since the brother-and-sister pair of the original fairy tale share the action equally: Hansel’s idea is to leave the trail of pebbles and later of crumbs so they can find their way home, while Gretel rescues Hansel by shoving the witch into the hot oven. Reversing their roles doesn’t strengthen the tale, in fact it makes Gretel appear more of the victim. ‘Rapunzel’ doesn’t really work for me either: in the Grimms’ original tale a man climbs a wall into a witch’s garden to steal the herbs his pregnant wife longs for. (She can’t climb into the garden herself because she’s pregnant.) In the gender-swapped version she’s still pregnant, but climbs into the (wizard’s) garden anyway to get the herbs her husband longs for; why couldn’t he do it himself? Then she promises to give the wizard her unborn child. This wreckage of narrative sense bothers me considerably more than the mildly ludicrous vision of the boy Rapunzel imprisoned in the tower with his long beard. (‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your beard!’ cries the Princess.)

‘Jaccqueline & the Beanstalk’ (although I wish she had been Jill), and ‘Handsome & the Beast’ are both very effective. In the one, we have a girl climbing a beanstalk and chopping it down; in the second, the love story works just as well with a female Beast and a male ‘Beauty’ – and it’s nice that Handsome’s mother is a prosperous merchant.

‘Snowdrop’ opens with a King who longs for a child and does embroidery. And why not? Both in and out of fairy tales, Kings have longed for children, especially heirs. At first I wasn’t convinced that the motive of the child’s stepfather (the Wicked King, so to speak) would be jealousy of Snowdrop’s looks, but then I thought further. The story forced me to imagine a fairy tale world in which a man‘s status and privilege would depend upon his beauty – where his power would depend upon the favour of women. And if that seems unnatural, well, it’s worth considering why, isn’t it? I also enjoyed the rather Amazonian Huntswoman who spares Snowdrop’s life, and it was fun to meet female dwarfs at last, who as we might suppose, work away just as diligently as the male ones.

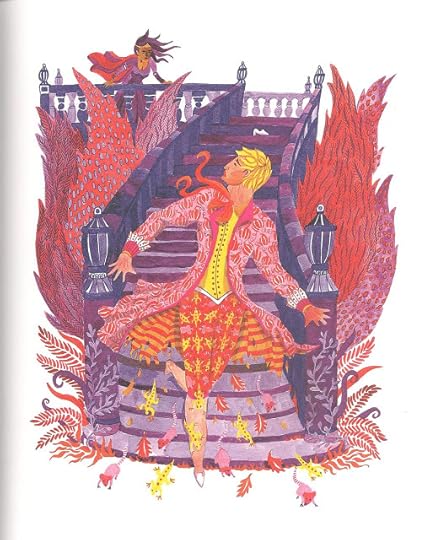

As a title, ‘The Sleeping Handsome in the Wood’ feels clumsy in English though it might work in French: Perrault’s ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ turning to ‘Le Beau au Bois Dormant’. (‘The Sleeping Prince in the Wood’ might have been better?) Once again, Charles Perrault’s story is so decorated and fanciful that we can easily believe it is a lively Prince who ‘diverts himself by running up and down the palace’, runs a spindle into his hand and falls asleep looking ‘like a little angel’. I like the daring Princess who penetrates the wood to reach the castle and wake him. But the second half of the tale, which I’ve always viewed as an addendum, in which the couple’s children and their mother (in this case, their father) are almost eaten by the Prince’s ogress mother (in this case, the Princess’s ogre father) works less well, since while it’s possible to imagine the Princess – daring as she is – hiding her marriage from her parents while still living with them, it’s far more difficult to imagine her hiding two pregnancies. It’s a pleasant touch to see the children’s roles reversed so that the little girl learns to fence, and is naughty, while the little boy is the quiet one.

In ‘Thumbelin’ – based of course on Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘Thumbelina’ – the gentle little boy who tends the sick swallow actually works better than the original little girl. Or so I think. ‘Thumbelina’ itself was probably inspired by the English fairy tale of ‘Tom Thumb’; but that story is all accidents and adventures as Tom gets into mischief, is swallowed by cows and fishes and ends up at King Arthur’s court. (Might we see a gender-swapped ‘Tom Thumb’ one day?) Where Tom Thumb is active, Thumbelina/Thumbelin is reactive: typically of Andersen, the tale is about suffering, social rejection and loneliness, as the child avoids a series of forced marriages and at last finds a place to belong. In the gender-swapped version, here’s the bit where a beetle, a cockchafer, discards the tiny boy she has flown off with.

All the other cockchafers who lived in the same tree came to pay calls; they examined Thumbelin closely and remarked, ‘Why, he has only two legs! How very miserable!’

‘He has no feelers!’ cried another.

‘How ugly he is!’ said all the gentleman cockchafers – and yet Thumbelin was really very pretty. […] There he sat and wept, because he was so ugly that the cockchafer would have nothing to do with him; and yet he was the most beautiful creature imaginable…

‘Gender-Swapped Fairy Tales’ is well worth a look. Its use of 19th century texts may make it less accessible to children; though there is no reason why they shouldn’t enjoy them, they might struggle to read them alone. (And anyone reading it aloud to a child should be warned that this tough version of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ends with the child being gobbled up by the wolf. No rescue, no woodcutter!) But for fairy tale fans, it offers a thought-provoking take on some over-familiar old tales. It is also beautifully produced, and the artwork by Karrie Fransman is truly gorgeous.

November 19, 2020

Searching for Janet, Queen of the Fairies

This essay first appeared in issue 19 of Gramarye, Winter 2019

The little village of Malham in the Yorkshire Dales is set in a landscape of stunning natural beauty close to the great curved cliff of Malham Cove and the dramatic gorge of Gordale Scar. Romantic painters flocked to it. Turner painted the Cove (see above), and the engraver William Westall published a set of views of the area that inspired Wordworth to write sonnets on the Cove and the Scar, though he never personally set eyes on either of them. ‘Pensive votary!’ he exclaimed in 1818,

… let thy feet repair

To Gordale chasm, terrific as the lair

Where the young lions couch; for so, by leave

Of the propitious hour, thou mayst perceive

The local deity, with oozy hair

And mineral crown, beside his jagged urn

Recumbent: him thou mayst behold, who hides

His lineaments by day, yet there presides,

Teaching the docile waters how to turn…

These efforts earned the dry comment from the author of an 1850 guide to the area: ‘Had they been written on the spot, instead of suggested by the engravings of Westall, they might have been of interest.’ Romantic visions of the kind Wordsworth encouraged may well have shaped a local legend, however, as we shall see.

You can walk to the Scar along the road from the village, but it’s prettier to take the path by the side of Gordale Beck. (A goreor geir is an ancient name for an angular or triangular piece of land: an appropriate term for the ever-narrowing valley into the gorge.) The streamside path runs through sloping pastures into a wooded limestone ravine called Little Gordale. In springtime it’s full of the starry white flowers of wild garlic, the beck rushing ever down over stones at your right hand. Before you reach Gordale Scar itself, at about the half-way point in fact, the winding up-and-down path brings you to the brink of a deep pool at the foot of a small and beautiful waterfall – Janet’s Foss. On the far side of the pool is a shallow cave tucked under a ledge of rock which can be reached by crossing the natural stepping stones that dam the pool. If you’re feeling adventurous though, and the water isn’t roaring down too hard, you can clamber up the rock-face to the right of the waterfall and wriggle your way into a much smaller cave that’s actually hidden behind the fall itself. It’s pretty damp. Never mind: it is the home of Janet, the local fairy queen.

Everyone in Malham knows this, but though I lived in the village for years and my parents lived there for decades I was never able to find out any more about Janet the fairy queen. No-one local knew any stories about her. And I began to wonder… well, is she a genuine piece of folklore? Or was she invented relatively recently, as a tourist attraction perhaps? My starting point was a brief paragraph in Arthur Raistrick’s classic book about the dale: Malham and Malham Moor (1947):

Foss is the old Norse name for a waterfall, and Janet was believed to be the queen of the local fairies … The fall is not high, but is remarkable for the beautiful tufa

It’s striking that this late Victorian writer turns what is really a set of walking instructions (‘take the right-hand stile opposite the row of thorn-bushes’) into something far more picturesque. Gray wants to remind us that a rowan is a ‘witch-tree’; he brings in classical nymphs and fauns; ‘airy little’ fairies dance in the silver moonlight of the ‘witching hour’ – before the prosaic conclusion:

Emerging from this cool and shady recess the visitor descends a field path to a small gate, whence the return to Malham may be made l. by the high-road; or r.to Gordale Scar.

Flowery as it is, this account shows that a tradition of a fairy queen named Janet was already associated with the spot by 1895 although her name was attached to the cave rather than to the ‘foss’ or waterfall itself.

Ten years earlier however, a party from the Blackburn Teacher’s Association visiting Malham for a day out in June 1885, received a rather different account of Janet. They lunched at the Buck Hotel, walked to the Cove and Gordale Scar where they viewed the waterfall, and then visited:

‘Janet’s Cave, where the legend runs that the witch Janet and her followers used to assemble at the cave’

In 1839 Robert Story of Gargrave, a village about eight miles from Malham, published a remarkable play in Shakespearian blank verse. He dedicated it to ‘Miss Currer of Eshton Hall’. She was an accomplished woman who collected historical manuscripts and rare printed works, and Eshton Hall was one of the most important houses around, situated in parkland a mile outside Gargrave on the Malham road.

Story, born in Northumberland in 1795 and whose father was a farmhand, worked as a shepherd and gardener before discovering a love of poetry. He moved to Gargrave in 1820, where he gained a reputation as ‘the Craven poet’. His play – unlikely ever to have been performed – is The Outlaw

The scheming Norton disguises himself as Henry disguised as a monk – impersonating him in order to frame him, if you follow me – and sets up an ambush for Lady Margaret at Gordale Scar where she has come to view the chasm: here Robert Story lets himself go with some vivid Romantic scene painting:

All gaze in silence

NORTON

Your silence moves no wonder. Gordale hath,

In its first burst of unexpected grandeur

A spell to awe the soul and chain the tongue.

How great its Maker then!

LADY MARGARET

… it might seem a tower

Whose architects were giants, did yon stream

Mar not the fancy.

RODDAM

Or a cavern hewn

From out the solid rock by genii!

LADY EMMA

Or fairy palace, by enchantment raised

To hold the elfin court in!

LADY MARGARET

‘Tis a scene

Too stern and gloomy for those gentle beings,

That love the green dell and the moonlight ring.

I like my first impression.

Like Lady Margaret, people visiting the Lakes or the Dales – not yet an easy journey in the early 1800s – were determined to get their money’s worth out of the experience. Writing at the more hard-headed end of the century, Johnnie Gray points out that some early accounts almost double the true heights of certain hills, representing Whernside and Pen-y-ghent as mountains well over 5000 feet high, for instance. This tendency to exaggerate and romanticize local attractions means we cannot assume, when the lovelorn Fanny talks about the Fairy Queen Gennet, that her words are based on genuine folklore.

This is the Fairy’s cave. Hast seen her, Norton?

But she ne’er shows herself, except to eyes

That soon must close in death.

Similar stories were told at Walton-le-Dale, at Warrington, and at Fairfield near Buxton in Derbyshire as well as Manchester, where in about 1800 a stream called ‘Shooter’s Brook’ passed in a culvert under the aqueduct which carried the Manchester and Ashton-under-Lyme canal over Store Street, near the London Road Station (now Manchester Piccadilly):

At that period there existed an opening or break left in the culvert forming a dangerous spot for children to play beside, and yet they often selected it. Their mothers tried to destroy the fascination by stating that Jenny Greenteeth laid in wait at the bottom to ‘nab’ children playing there.

And was Jenny Greenteeth once more than a nursery tale? Responding to John Higson’s piece in ‘Notes and Queries’, a correspondent named James Bowker claimed that ‘the water spirits of the Gothic mythology, although in other respects endowed with marvellous and seductive beauty, had green teeth…’ He provides no reference, but Jacob Grimm, in his ‘Teutonic Mythology’ (1835) says that the Danish water spirit, the nøkke, wears a green hat and that ‘when he grins you see his green teeth’

Picture Credits:Malham Cove by Turner, Tate BritainJanet's Foss, Gordale, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Fairy's Lake by Jon Anster Fitzgerald 1866, TateGordale Scar, James Ward, 1811, Tate Britain, part of a collection entitled "Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale)" Nøkken, Theodor Kittelsen, 1904, National Musem of NorwayNäcken (Water Spirit) by Ernst Josephsen, National Museum of SwedenGordale Scar, James Ward, Tate Britain.

November 10, 2020

Lord Dunsany and the magical power of poetry

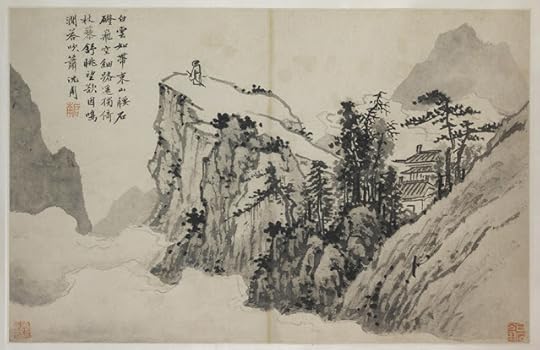

Here is Lord Dunsany speaking beautifully about poetry, in 'The Donellan Lectures' delivered at Trinity College, Dublin, 1943:

"Nothing at all separates a poet in China from a poet in Ireland: both feel that beauty is sacred and is the outward and obvious expression of what is right and fitting: both labour to express those feelings worthily; their separation is only by centuries, and down these their thoughts travel until they meet in any land. And how does this strange magic work?

"If I revealed that secret, the magicians of the world would be angry with me, for they have always guarded their mysteries. But they need have no fear that this great mystery will escape from my lips, because I do not know it; I can only guess that our minds, which are strangely different from that lumber with which they are stored and that we call facts, are created in harmony with many ancient things like ripples on water, or the wind going over the trees, and even inhuman and undisciplined things like the singing of birds; and that words that are attuned to this ancient harmony, to the voice of the woods and the hills, the old voice of the earth, come to us when we hear them like his own language suddenly spoken at night to a wanderer in a far country.

"However the magic may work, the power that metre has is best explained by Keats when, describing a kindred power, the song of the nightingale, he says that it

oft-times hath

Charmed magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

"It is almost like the call of a horn heard in the morning by a busy man in a town, heard far off behind him from grassy uplands beyond the woods, with dew still on the grass and on the spider’s web … and sunlight streaming down valleys, that has not yet come to the town, for the golden morning has not yet peered over the high roofs. The man turns to the sound of the horn, but he cannot follow, for it is far away and he has much to do, and he has not the right clothes or boots for this: those distant valleys are not for him. Bodies are not moved so easily. But … the spirit, if once aroused, is up and away with a speed of which our bodies know nothing, and which cannot indeed be compared with the movement of any body, though the sudden dart of a snipe out of Irish marshes is something more like it than anything we can attain.

"But how is the spirit aroused by that haunting call, by that chiming of words that we call metre and rhyme? Our ears, our thoughts, our hearts, call it what you will, are made one way, and metre is made on the same plan, and so the two respond as two birds calling; singing and answering over a wide valley. How it is so I can only guess, but … it is certain that poets have the power to cast such spells.

"The certainty can be readily demonstrated by a single experiment. Take for instance a sentence such as: ‘She and I were born about the same time, and used to live at Brighton.’ You may anticipate a story when you hear those words, but you cannot be thrilled by the anticipation. Now take something similar, but said by a magician, Edgar Allan Poe:

I was a child and she was a child

In a kingdom by the sea.

"There you have a spell at once, or at least the beginning of one, one is half enchanted already, one’s spirit is prepared already for a far journey, and a very far journey: those simple words call to it far from here, for a kingdom by the sea is far on the way to fairyland. We have no such kingdoms here; kingdoms with coastlines we have in abundance, but a kingdom by the sea is a long way off, like little countries of which our nurses might have read tales to us a very long while ago."

Picture credits:

Poet on a mountain top by Shen Zhou, 1427 - 1509, Wikipedia

Miranda by John William Waterhouse, 1916, Wikimedia Commons

Val d'Aosta by John Brett, 1858 Wikimedia Commons

Walton on the Naze, Ford Madox Brown, 1860, Birmingham Museums Trust

October 27, 2020

Wicked Witches in Children's Fiction

From goddesses and witch queens, I turn to witches of a more mundane sort, ranging in age from (apparently) sweet old ladies to (apparently) sweet little girls. The examples are all taken either from children's classics or from less well known children's books which in my judgement are classics anyway... Some of these writers intend us to take the wickedness of the witches in their stories very seriously, and I’ll tackle those first. Others revel in the transgessive naughtiness of their witches and fully expect their readers to enjoy this, too.

The first Seriously Bad Witch I want you to meet is Emma Cobley, from what I consider Elizabeth Goudge’s best children’s book, Linnets and Valerians (1964). Goudge was a religious, spiritual writer and an intelligent, questioning one who wrote movingly about mental illness in some of her adult books. She was conscious of goodness as a great force, and of evil as a force almost as strong… Emma Cobley is an elderly woman of humble background who – at the beginning of the 1900s – keeps the post office and shop of High Barton, a small Dartmoor village. As a young, vivid girl she was deeply in love with Hugo Valerian, the squire, but when he married the doctor’s daughter Alicia, in her jealous hatred she cast spells upon him and his wife and child. Emma’s shop is full of tempting sweets like the witch’s house in Hansel and Gretel, and she owns a black cat which can change size. Her main adversary is the brave and gentle Nan Linnet, eldest of four children who’ve come to stay in the village with their Uncle Ambrose, the vicar. Emma’s snarling cat scratches the children when they first ‘fall into’ the shop to buy sweets and postcards, but Emma – who wears ‘an old fashioned white mob cap, a voluminous black dress and little red shawl crossed over her chest’ seemskind and helpful… though she warns them against climbing Lion Tor, the hill above the village: ‘Something nasty might happen to you there.’ But her sweets! The children choose:

…a pennyworth of peppermint lumps that looked like striped brown bees, a pennyworth of boiled lemon sweets the colour of pale honey, a penny-ha’pennyworth of satin pralines in colours of pink and mauve, and a pennyworth of liquorice allsorts. And out of pure goodness of heart Emma Cobley added for nothing a packet of sherbet. They did not know what that was, and she had to show them how to put a pinch of powder on their tongues and then stand with their tongues out enjoying the glorious refreshing fizz.

But their dog Absolom has his tail between his legs. And later, Nan discovers Emma’s spell book hidden in the little parlour which her uncle has given her – with spells for ‘binding the tongue’, loss of memory and for ‘a coolness to come between a man and a woman’. Later she learns the tragic story of Lady Alicia up at the manor, who lost her little boy twenty years ago in a mist on Lion Tor, and whose husband Hugo is missing. And she meets a dumb, wild man living on the moors – and at last with the help of the gardener Ezra, a sort of white hedge-wizard, the children find a set of little figures carved from mandrake root, with pins driven into them. As Ezra says,

‘What Emma did to these figures she did to the people. She ’as the power. It be all in the mind, lad, the mind and the will, an’ Emma, she’s strong-minded and strong-willed. Now, maid, you read out o’ that book the spell for binding the tongue.’Nan found the place and read it out and Ezra picked up one of the little images and brought it to the light. …It was of a little boy about eight years old and his had his tongue out. … They looked closer and saw that the pins pierced the tongue. They had been thrust in while the mandrake root was still supple and now it was like hard wood and they were rusted in firmly.

This reflects a rather different light on that picture of the children sticking out their tongues in Emma’s shop to enjoy the fizz of the sherbet. The witchcraft in this book is an expression of the capacity of the human soul to cling to destructive passions, but it is defeated by Ezra’s white magic, and the good magic of honeybees, and by acts of kindness and love.

The acquisitiveness of the next witch, Dr Melanie D. Powers of Lucy Boston’s An Enemy at Green Knowe (1964), is more difficult to deal with. (For those not familiar with them the Green Knowe books are a series of sensitive ghost stories set in the author’s 11th century manor house in Cambridgeshire.) The grandson of the house, Tolly, and his friend Ping pit themselves against his grandmother’s new neighbour, a prying, malicious woman who is a Cambridge don and scholar of the occult and has – we slowly realise – struck a Faustian bargain with the devil. Believing an ancient occult manuscript is hidden somewhere in the house, she will stop at nothing to get hold of it. Miss Powers, who has an unaccountable dislike of passing in front of a mirror, invites herself to tea at Green Knowe where she makes ultra-sweet conversation with such ominous lines as, ‘One can sense that yours is a very happy family. Happy families are not so frequent as people make out. And unfortunately they are easily broken up. Very easily.’ And she refuses a small cake with the words, ‘Grown-ups do better without extra luxuries like that. It is enough for me to look at them’. However she can’t stop greedily eyeing them…

About half an hour later when tea was over… Mrs Oldknowe offered to lead the way upstairs to see the rest of the house. Miss Powers was standing with her back to the table, her hands clasped behind her, lingering to look at the picture over the fireplace, when Tolly… saw one of the little French cakes move, jerkily, as if a mouse were pulling it. Then it slid over the edge of the plate… and into the twiddling fingers held ready for it behind Miss Powers’ back.

This tells us everything we need to know about Miss Powers. She is petty, deceitful, covetous and malicious, sends a series of almost Biblical plagues on the house (snakes, feral cats that kill the songbirds, etc) and causes real harm. The boys’ beloved grandmother Mrs Oldknowe is nearly defeated by her, and the eventual triumph of good in the midst of a total eclipse of the sun, when Miss Power's demon is driven out, is precariously achieved at the cost of considerable damage to the house.

Emma Cobley and Melanie Powers come to different ends. After Emma’s book of spells is burned on Ezra’s fire, where the pages writhe ‘like snakes in the flames and then were consumed to nothing,’ Emma and her husband Tom change from being the leaders of the village coven to ‘quite nice old people’. They make amends and are forgiven for the harm they have done. Wickedness has gone for ever and the village is happy again; but what has happened to Emma’s ‘strong mind and strong will’? We may hope she now uses her strength for good, but the lukewarm phrase ‘quite nice’ doesn’t promise much.

Miss Powers comes to a more disturbing end: she is broken. The two boys have learned her full, demonic name – Melusine Demogorgona Phospher – and hiding in a tree they chant it aloud to her through paper trumpets, diminishing it by one syllable on each repetition in a ritual of dissolution. On the last and final syllable, ‘pher!’ she collapses, crying to her demon lord, ‘Don’t leave me!’

With a last convulsion the writhing form, now on the ground, broke up into two, and an abomination the mind refuses to acknowledge stood over her, and spurned her, and sped away hidden by a line of hedge.

Now harmless, Miss Powers is dreadfully damaged, a ‘pop-eyed, huddled little woman’ who runs aimlessly about like a hen.

‘I’ve lost my Cat.’ She turned and scurried away. ‘I’ve lost…’ For the last time the boys watched her going away down the garden path – nervous, running, stumbling, diminishing. The gate clicked.

It’s wonderful writing, though rather a shame that it's a woman scholar who gets to be evil while the male scholar in the story, the quiet but dependable Mr Pope (named in contrast to the equally meaningfully named Miss Powers) helps save the day by declaiming an Invocation of Power from a manuscript he's working on: 'The Ten Powers of Moses'. But Tolly's grandmother Mrs Oldknowe is good (as in children's fiction, grandmothers nearly always are) and a bad male scholar does figure in the tale, for as ever at Green Knowe, the story has its roots in the past of the house, when a Faustian 16th century alchemist named Dr Vogel had his own brush with the devil. It's his book Miss Powers is ambitious to find.