Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 12

July 29, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #23: CAP O’ RUSHES

This English fairy tale will remind you in equal parts of Cinderella and King Lear. A rich father orders his daughters to tell him how much they love him. (Never a wise thing to do.) When his youngest daughter gives him an answer he finds unacceptable, he banishes her from his house. Now destitute and homeless, she walks away into a fen, weaves herself a cloak and cap of rushes to hide her grand clothing and finds unpaid work as a scullery maid in another great house. Since she refuses to tell them her own name, they call her Cap o’ Rushes.

After this, the story conforms for a while pretty much to the Cinderella type, although apart from being unpaid she’s not badly treated: the other kitchen maids behave to her in quite a friendly manner. Evening after evening they try unsuccessfully to get her to come along with them to watch the grand people dancing. Cap o’ Rushes has her own fish to fry, though, and her eventual marriage is less an end in itself than an opportunity to teach her arrogant father a lessonThe tale seems to have first appeared in the Suffolk Notes and Queries of The Ipswich Journal. It was contributed by one A.W.T. along with the note: ‘Told by an old Servant to the Writer when a Child’. I have not found a date for this, but it was republished in Longman’s Magazine, Feb. 1889 and in Folk-Lore, Vol I, no III, September 1890.

Well, there was once a very rich gentleman and he’d three daughters, and he thought to see how fond they was of him. So he says to the first, ‘How much d’you love me, my dear?’

‘Why,’ she says, ‘as I love my life.’

‘That’s good,’ says he. So he says to the second, ‘How much do you love me, my dear?’

‘Why,’ she says, ‘better nor all the world.’

‘That’s good’ says he, so he says to the third, ‘How much do you love me, my dear?’

‘Why, I love you as fresh meat loves salt,’ says she.

Well, he were that angry. ‘You don’t love me at all,’ says he, ‘and in my house you stay no longer.’ So he drove her out there and then and shut the door on her.

Well she went away, and on and on till she came to a fen, and there she gathered a lot of rushes and made them into a cloak, with a kind o’ hood, to cover her from head to foot and to hide her fine clothes. And then she went on and on till she came to a great house.

‘Do you want a maid?’ says she.

‘No we don’t,’ says they.

‘I hain’t nowhere to go,’ says she, ‘and I’d ask no wages and do any kind of work,’ says she.

‘Well,’ says they, ‘if you like to wash the pots and scrape the saucepans, you may stay.’

So she stayed there and washed the pots and scraped the saucepans and did all the dirty work, and because she gave no name they called her ‘Cap o’ Rushes’.

Now one day there was to be a great dance a little way off, and the servants was let to go and look at the grand people. Cap o Rushes said she was too tired to go, so she stayed home. But when they was gone she offed with her cap o’ rushes and cleaned herself, and went to the dance. No one there was so finely dressed as she.

Well who should be there but her master’s son, and what should he do but fall in love with her the minute he set eyes on her? He wouldn’t dance with anyone else. But before the dance was done, Cap o’ Rushes she slipped off and away she went home. And when the other maids was back she was framin’ to be asleep with her cap o’ rushes on.

Next morning they says to her, ‘You did miss a sight, Cap o’ Rushes!’

‘What sight was that?’ says she.

‘Why, the beautifullest lady you ever see dressed right gay and gallant. The young master, he never took his eyes off her.’

‘I should ha’ liked to have seen that!’ says Cap o’ Rushes.

‘Well there’s to be another dance this evening, and perhaps she’ll be there.’

But come the evening, Cap o’ Rushes said she was too tired to go with them. Howsumdever, when they was gone she offed with her cap o’ rushes and cleaned herself, and away she went to the dance.

The master’s son had been reckoning on seeing her, and he danced with no one else and never took his eyes off her. But before the dance was over she slipped off and home she went, and when the maids came back she framed to be asleep with her cap o’ rushes on.

Next day they says to her again, ‘Well, Cap o’ Rushes, you should ha’ been there to see the lady. There she was again, gay and gallant, and the young master he never took his eyes off her.’ ‘Well, there,’ says she, ‘I should ha’ liked to ha’ seen her!’

‘Well,’ says they, ‘there’s a dance again this evening, and you must go with us, for she’s sure to be there.’

But come this evening, Cap o’ Rushes said she was too tired to go, and do what they would she stayed at home. But when they was gone she offed with her cap o’ rushes and cleaned herself, and away she went to the dance.

The master’s son was rarely glad when he saw her. He danced with none but her and never took his eyes off her. When she wouldn’t tell him her name or where she came from, he gave her a ring and told her that if he didn’t see her again, he should die. But afore the dance was over she slipped off and home she went, and when the maids came home she was framing to be asleep with her cap o’ rushes on.

So the next day they says to her, ‘There, Cap o’ Rushes, you didn’t come last night, and now you won’t see the lady, for there’s no more dances.’

‘Well, I should ha’ rarely liked to ha’ seen her,’ says she.

The master’s son he tried every way to find out where the lady was gone, but ask where he might and go where he might, he never heard nothing about her. And he got worse and worse for the love of her, till he had to keep to his bed.

‘Make some gruel for the young master,’ they says to the cook, ‘he’s dying for love of the lady.’ The cook, she set about making it, when Cap o’ Rushes came in.

‘What are you doin’?’ says she.

‘I’m going to make some gruel for the young master,’ says the cook, ‘for he’s dying for love of the lady.’

‘Let me make it,’ says Cap o’ Rushes.

Well the cook wouldn’t let her at first, but at last she said yes, and Cap o’ Rushes made the gruel. And when she had made it she slipped the ring into it on the sly before the cook took it upstairs. The young man, he drank it, and he saw the ring at the bottom.

‘Send for the cook!’ says he. So up she comes.

‘Who made this gruel?’ says he.

‘I did,’ says the cook, for she were frightened. And he looked at her.

‘No you didn’t,’ says he. ‘Say who did it, and you shan’t be harmed.’

‘Well then, ‘twas Cap o’ Rushes,’ says she.

‘Send Cap o’ Rushes here,’ says he. So Cap o’ Rushes came.

‘Did you make my gruel?’ says he.

‘Yes, I did,’ says she.

‘Where did you get this ring?’ says he.

‘From him as gave it me,’ says she.

‘Who are you, then?’ says the young man.

‘I’ll show you,’ says she, and she offed with her cap o’ rushes and there she was in her beautiful clothes.

Well, the master’s son got well very soon, and they was to be married in a little time. It was to be a very grand wedding, and everyone was asked, far and near. And Cap o’ Rushes’ father was asked. But she never told nobody who she was.

But before the wedding she went to the cook, and says she:

‘I want you to dress every dish without a mite of salt.’

‘That’ll be rarely tasty,’ says the cook.

‘That don’t signify,’ says she.

‘Very well,’ says the cook.

Well, the wedding day came, and they was married. And after they was married, all the company sat down to their vittles. When they began to eat the meat, that was so tasteless they couldn’t eat it. But Cap o’ Rushes’ father he tried first one dish and then another, and then he burst out crying.

‘What is the matter?’ said the master’s son to him.

‘Oh!’ says he, ‘I had a daughter. And I asked her how much she loved me. And she said, “As much as fresh meat loves salt.” And I turned her from my door, for I thought she didn’t love me. And now I see she loved me best of all. And she may be dead for aught I know.’

‘No, father, here she is!’ said Cap o’ Rushes. And she goes up to him and puts her arms around him.

And so they was happy ever after.

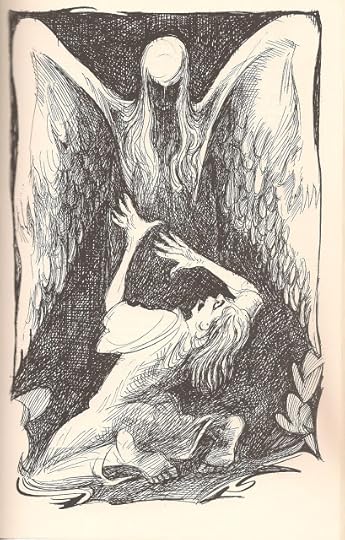

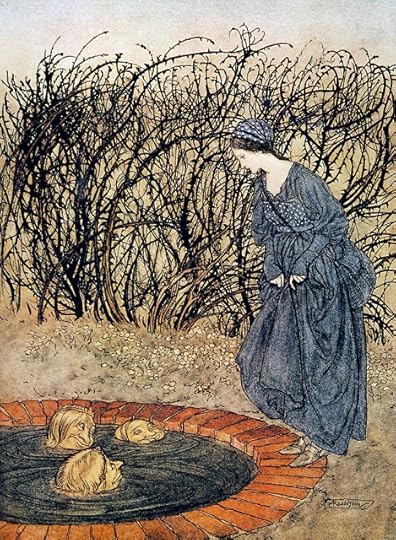

Picture credits:Cap o' Rushes by John BattenCap o' Rushes by Arthur Rackham

Picture credits:Cap o' Rushes by John BattenCap o' Rushes by Arthur Rackham

Published on July 29, 2020 07:04

July 21, 2020

Strong Fairy tale Heroines #22: THE FLYING HEAD

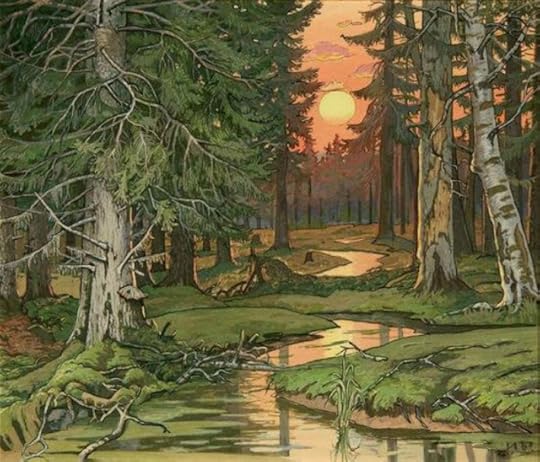

Home of the Leshy. "Fairy Forest at Sunset" by Ivan Bilibin, 1906.

Home of the Leshy. "Fairy Forest at Sunset" by Ivan Bilibin, 1906.This Russian fairy tale, collected by Ivan Khudyakov in the 1860s (and rather clunkily titled ‘The Stepmother’s Daughter and the Stepdaughter’) is outlined in ‘Russian Folk-Tales’ translated by WRS Ralston (1873). Ralston quotes just a couple of paragraphs of the story and merely summarises the second half. I cannot source any other English translation, so since it’s quite clear what happens, and it’s a great story, I’ve filled in the outline.

The basic motif (AT 480: ‘The Kind and the Unkind Girls’) is common to many fairy tales: the Grimms’ ‘Mother Holle’, Perrault’s ‘Diamonds and Toads’, and the Scots tale ‘The Well at the World’s End’ in this series are good examples. Are these kinds of heroines 'strong'? In what way are they not? They deal with their own problems in their own way. Men are quite unimportant in this type of tale, rarely even making an appearance: the message is that kindness, courtesy and hard work will be rewarded with riches, not marriage. Anyway, the details of this particular version are so peculiarly sinister, I can’t resist including it.

Magical disembodied heads in European fairy tales usually rise out of wells or springs, rather than flying (or rolling?) through woods, and they usually ask for the heroine to comb their hair, or wash them. (Do what they request, and do it nicely!) The one in this fairy tale may (possibly) be some incarnation of the Leshy, the spirit of the woods - or it may not: Russian fairy tale experts out there, please let me know! Interestingly though, forest-dwelling flying heads are to be found in North-East Coast Native American folklore. These whirl through the trees and may emit shrieks so terrible as to bring death to the hearer. The Passamaquoddy tell of a creature named K’Cheebellok, a head without a body, but with ‘heart, wings and long legs’ (Fewkes, ‘Contribution to Passamaquoddy Folk-Lore’, Journal of American Folklore 1890, 271); and in their collection of Native American stories for children, ‘When the Chenoo Howls’ (Walker, 1998), Joseph and James Bruchac tell a story based on Senecan and Iroquois legends, of Dagwaynonyent, a malevolent and voracious Flying Head. (Being polite to this one wouldn’t have worked.)

What’s also interesting that even the ‘kind’ heroine of this story seems to feel uneasy about the Head. Why else would she rely upon the clarion call of cock-crow to banish it – usually the cue for ghosts and evil spirits to depart?

There was once an old woodcutter who had two daughters, one by his first wife and one by his second. The second wife became jealous of her stepdaughter. She treated her badly and never stopped nagging her husband, telling him they were too poor to raise two girls. ‘You had better take her into the forest and leave her,’ she said. ‘She is no good to us!’

At last, ground down by her complaints, the woodcutter agreed. He took the girl away into the forest with him, and left her in a kind of hut, telling her to prepare some soup for their dinner while he was cutting wood.

At that time, there happened to be a gale blowing. The old man tied a log to a tree in such a way that when the wind blew, the log struck the tree and made a knocking sound. This made the girl think the old man was cutting wood nearby, but in reality he had gone away.

When the soup was ready, she called to her father to come to dinner. No reply came from him, so she called again and again.

Now, deep in the forest there was a human head, and it heard the girl calling out, ‘Come to dinner! Come to dinner!’

So it answered her: ‘I’m coming! I’m coming!’

And when the Head arrived, it cried, ‘Maiden, open the door!’

She opened the door.

‘Maiden, Maiden! Lift me over the threshold!’

She lifted it over.

‘Maiden, Maiden! Put the dinner on the table!’

She did so, and she and the Head sat down to dinner. When they had dined, ‘Maiden, Maiden!’ said the Head, ‘take me off the bench!’

She took it off the bench and cleared the table. It lay down to sleep on the bare floor; she lay down on the bench. As soon as she was fast asleep, the Head went into the forest and called its servants. When the maiden woke, the hut had become a house. Servants, horses and everything one could think of suddenly appeared.

The servants came to the maiden and said, ‘Get up! It’s time to go for a drive!’ So she got into a carriage along with the Head, but she took a cock along with her. As they drove along, she told the cock to crow, and it crowed. Again she told it to crow; it crowed again. And a third time she told it to crow. When it had crowed for the third time, the Head fell to pieces and became a heap of golden coins.

The girl told the servants to drive her back to her home. When her father and stepmother saw the gold treasure she had brought back with her, they were amazed, and the stepmother wanted her own daughter to have the same good fortune. ‘Take the girl into the woods with you,’ she told her husband, ‘and leave her in the hut!’ And the woodcutter did so.

Alone in the hut, the girl stirred the soup until it was ready, and then she called out, ‘Come to dinner! Come to dinner!’

Deep in the forest, the human head heard her.

‘I’m coming! I’m coming!’ it answered.

And when it arrived, it cried, ‘Maiden, open the door!’

So the girl opened the door. When she saw the Head, she was so frightened she hid behind the door and tried to push it shut. But the Head was in the way, and it said, ‘Maiden, Maiden! lift me over the threshold!’

‘No, I won’t touch a horrible Head like you!’

So the Head rolled itself into the hut.

‘Maiden, Maiden! put the dinner on the table!’

‘No, I won’t eat with a horrible Head like you!’

So the Head had to dish up its own dinner. The bowl and spoon flew on to the table, and the spoon worked hard and flew back and forth from the bowl, serving the Head until all the soup was gone.

‘Maiden, Maiden,’ said the Head. ‘Take me off the bench!’

But still the girl wouldn’t touch the Head, so it sprang down by itself and lay on the bare floor to sleep.

And the girl was too frightened to creep past it, so she lay down on the bench and was so weary that she fell asleep.

And when she was fast asleep, it ate her.

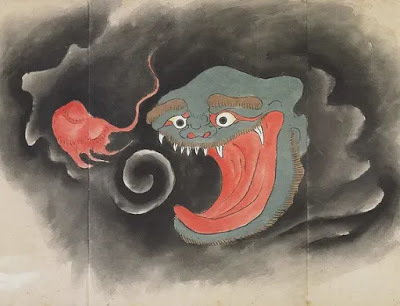

I can find no illustrations of this Russian fairy tale, but I have found some great depictions of flying heads from other cultures. This Japanese yokai, from the Bakemono zukushi scroll (Edo period, 18th/19th century) is a cloud dwelling monster with a mouth large enough to swallow the world!

Published on July 21, 2020 03:55

July 14, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #21: PRINCE LINDWORM

This fairy tale is often mistakenly claimed to be Norwegian – a mistake which can be traced back to the anonymous writer of the English preface to Kay Nielsen’s ‘East of the Sun and West of the Moon’ (1920) which states that all the stories in the collection come from Sir George Dasent’s 1859 translation of Asbjørnsen & Moe’s ‘Norske Folkeeventyr’ and then adds that ‘Prince Lindworm' has been ‘newly translated for this volume'– leaving the distinct impression that it too must be a Norwegian story.

But ‘Prince Lindworm’ is Danish. As ‘Kong Lindorm’ it was collected by N Levinson in 1854 from Maren Mathisdatter in Fureby by Løkken, and was published in Axel Olrik’s Danske Sagn og Aeventyr fra Folkemunde, 1913. (Thanks to Simon Roy Hughes's excellent blog 'Norwegian Folktales' for this information.) There is also a much longer and more complicated 'King Lindorm' in the Langs' 'The Pink Story Book', translated from Swedish.

I don’t know who did this English translation; it might have been Kay Nielsen himself, who of course was a Dane. Some lines, such as ‘the Queen wanted a dear little child to play with, and the King wanted an heir to his kingdom’ do not have the ring of authentic oral storytelling to me and are probably attempts to make the story more accessible to children. Helpful old women in fairy tales are usually just helpful old women: in this story someone, likely the translator, has decided to call her a witch and then has to explain that ‘she was a nice kind of witch, not the cantankerous sort’. I’ve deleted it. (Neither am I convinced that this old woman lives in an oak tree, but let that pass.)

In fact this fairy tale is surprisingly violent! It starts like ‘Tatterhood’(#15 in this series): a queen who longs for a child must choose one of two flowers to eat, and eats both – but it rapidly turns splendidly sinister as the queen gives birth to twins, one of which is a malevolent lindworm.

It can be difficult to tell just from reading a fairy tale how it might come across in a live performance. The outrageous behaviour of the king and queen in this story is a good example: it’s related in a very poker-faced way on the page. But a good story teller would bring out all the black comedy – the selfishness of the human prince who wants his parents to sacrifice yet another ‘bride’ to his serpent brother (with no guarantee of any more success than the last time), the increasingly desperate scheming, the fearful king peeping through the keyhole, and the surely guilt-driven ‘love and kindness’ which king and queen finally lavish upon their new daughter-in-law… All of this could be very funny.

As for the shepherd’s daughter, by holding her nerve and following the old woman’s advice to the letter (as the queen neglected to do), she gets the better of her dangerous slimy serpent-husband, challenge for challenge. There’s a hint of ‘Tam Lin’ in the plot – you’ll remember how Janet saves her enchanted lover by holding him tight as he’s changed into all kinds of deadly forms? Unlike Janet, this girl’s actions are driven by self-preservation rather than love. In a fairy tale we can be sure that once Prince Lindworm is disenchanted, the two of them really will live happily ever after; but I’m afraid the other two princesses are simply collateral damage. As supporting cast they are expendable, like the anonymous redshirted crew of the Starship Enterprise who get blasted moments after beaming down to the alien planet. Fairy tales are more hard-hearted than you think.

[NB:When you get to it, 'lye' is a strong alkali solution obtained by mixing water with wood ash.]

Once upon a time there was a fine young king who was married to the loveliest of queens. They were exceedingly happy, all but for one thing – they had no children. And this often made them both sad, because the queen wanted a dear little child to play with, and the king wanted an heir to his kingdom.

One day the queen went out for a walk by herself and she met an old woman who asked, ‘Why do you look so sad, lady?’

‘It’s no use my telling you,’ said the queen, ‘no one in the world can help me.’

‘Oh, you never know,’ said the old woman. ‘Just let me hear your trouble, and maybe I can put things to rights.’

‘The king and I have no children, and that is why I am so distressed.’

‘I can set that right,’ said the old woman. ‘Listen, and do exactly as I tell you. Tonight, at sunset, take a little drinking-cup with two lugs and put it bottom upwards on the ground in the north-west corner of your garden. Go and lift it tomorrow morning at sunrise, and you will find two roses underneath it. If you eat the red rose, you will give birth to a little boy, if you eat the white rose, to a little girl, but whatever you do, do not eat both the roses, or you’ll be sorry – I warn you!’

The queen thanked the old woman a thousand times. She went home and did as she’d been told, and next morning at sunrise she crept out into the garden and lifted the drinking-cup. There were the two roses underneath it, one red and one white. And now she did not know which to choose.

‘If I choose the red one,' she thought, ‘I will have a little boy who may grow up to go to the wars and be killed. But if I choose the white one, and have a little girl, one day she will get married and go away and leave us. So whichever it is, we may be left with no child after all.’

At last she decided on the white rose, and she ate it, and it was so sweet she took and ate the red one too, without remembering the old woman’s warning.

Some time after this, the king went away to the wars, and while he was still away the queen gave birth to twins. One was a lovely baby boy, and the other was a Lindworm. She was terribly frightened when she saw the Lindworm, but he wriggled away out of the room and nobody seemed to have seen him but herself, so she thought that it must have been a dream. The baby prince was so beautiful and strong, the queen was delighted with him, and so was the king when he came home. Not a word was said about the Lindworm: only the queen thought about it now and then.

Years passed and it was time for the prince to be married. The king sent him off to visit foreign kingdoms, in the royal coach, with six white horses, to find a princess grand enough to be his wife. But at the very first cross-roads the way was barred by an enormous Lindworm, enough to frighten the bravest. He lay in the middle of the road with a great wide-open mouth, and cried,

‘A bride for me before a bride for you!’

Then the prince made the coach turn round and try another road, but it was all no use. For at the first cross-ways, there lay the Lindworm again, crying out, ‘A bride for me before a bride for you!’ So the prince had to turn back home again for the castle, and give up his visits to the foreign kingdoms. And his mother the queen had to confess that what the Lindworm said was true. For he really was the eldest of her twins, and so ought to have a wedding first.

There seemed nothing for it but to find a bride for the Lindworm, if his younger brother the prince were to be married at all. So the king wrote to a distant country and asked for a princess to marry his son, but of course he didn’t say which son, and presently a princess arrived. But she wasn’t allowed to see her bridegroom until he stood by her side in the great hall and was married to her, and then of course it was too late for her to say she wouldn’t have him. But next morning the princess had vanished. The Lindworm lay sleeping all alone, and it was quite plain that he had eaten her.

A little while after, the prince decided that he might now go journeying again in search of a princess. Off he drove in the royal carriage with the six white horses, but at the first cross-ways, there lay the Lindworm, crying with his great wide open mouth, ‘A bride for me before a bride for you!’ So the carriage tried another road, and the same thing happened, and they had to turn back again this time, just as before. Then the king wrote to several foreign countries, to know if anyone would marry his son. At last another princess arrived, this time from a very far distant land. And of course, she was not allowed to see her future husband before the wedding took place, – and then, lo and behold! it was the Lindworm who stood at her side. And next morning the princess had disappeared, and the Lindworm lay sleeping all alone, and it was quite clear that he had eaten her.

By and by the prince started on his quest for the third time, and at the first cross-roads there lay the Lindworm with his great wide open mouth, demanding a bride as before. And the prince went straight back to the castle and told the king he must find another bride for his elder brother.

‘Where shall I find her?’ said the king. ‘I have already made enemies of two great kings who sent their daughters here as brides, and I have no notion how I can obtain a third lady. People are beginning to talk, and I am sure no princess will come.’

Now down in a cottage near the wood lived the king’s shepherd, an old man with his only daughter. So the king came and asked him, ‘Will you give me your daughter to marry my son the Lindworm? I will make you rich for the rest of your life.’

‘No sir,’ said the shepherd, ‘that I cannot do. She is my only child and I need her to care of me. Besides, if the Lindworm would not spare two lovely princesses, he will not spare her either. He will gobble her up, and she is much too good for such a fate.’

But the king wouldn’t take no for an answer, and the old man at last had to give in.

Well, when the old shepherd told his daughter she was to be Prince Lindworm’s bride, she was utterly in despair. Into the woods she went, crying and wringing her hands and bewailing her hard fate. And while she wandered to and fro, and old woman appeared out of a big hollow oak tree and asked her why she was so so sad?

‘Oh it’s no use telling you,’ said the shepherd girl, ‘for no one in the world can help me.’

‘Oh, you never know,’ said the old woman. ‘Just let me hear what your trouble is, and maybe I can put things right.’

‘Ah, how can you?’ said the girl. ‘For I am to be married to the king’s eldest son, who is a Lindworm, and he has already married two beautiful princesses and devoured them, and he will eat me too!’

‘All that be set right,’ said the old woman, ‘if you will do exactly as I tell you.’ And the girl said she would.

‘Listen then,’ said the old woman. ‘After the marriage ceremony is over, and when it is time for you to go to bed, you must ask to be dressed in ten snow-white shifts. And you must ask for a tub full of lye, and a tub full of fresh milk, and and many whips as a boy can carry in his arms – and have all these brought into your bed-chamber. Then, when the Lindworm bids you shed a shift, you must bid him slough a skin. And when all his skins are off, you must dip the whips in the lye and whip him; next you must wash him in the fresh milk; and lastly, you must take him and hold him in your arms, if it’s only for one moment.’

‘The last is the worst,’ said the shepherd’s daughter, and she shuddered at the thought of holding the cold, slimy, scaly Lindworm.

‘Do as I say and all will be well,’ said the old woman.

When the wedding day arrived the girl was fetched in the royal chariot with the six white horses, and taken to the castle to be decked as a bride. And she asked for ten snow-white shifts to be brought to her, and the tub of lye, and the tub of milk, and as many whips as a boy could carry in his arms, and the king said she should have whatever she asked for.

She was dressed in beautiful robes and looked the loveliest of brides. She was led to the hall where the wedding ceremony was to take place, and saw the Lindworm for the first time as he came in and stood by her side. So they were married, and the wedding feast was held.

When the feast was over, the bridegroom and bride were brought to their apartment, and as soon as the door was shut, the Lindworm turned to her and said,

‘Fair maiden, shed a shift!’

The shepherd’s daughter answered him, ‘Prince Lindworm, slough a skin!’

‘No one has ever dared tell me to do that before!’ said he.

‘But I command you to do it now!’ said she. Then he began to moan and wriggle: and in a few minutes a long snake-skin lay upon the floor beside him. The girl drew off her first shift, and spread it on top of the skin.

The Lindworm said to her again, ‘Fair maiden, shed a shift.’

The Lindworm said to her again, ‘Fair maiden, shed a shift.’The shepherd’s daughter answered him again, ‘Prince Lindworm, slough a skin.’

‘No one has ever dared tell me to do that before,’ said he.

‘But I command you to do it now,’ said she. Then with groans and moans he cast off the second skin, and she covered it with her second shift. The Lindworm said for the third time,

‘Fair maiden, shed a shift!’

The shepherd’s daughter anwered him again, ‘Prince Lindworm, slough a skin.’

‘No one has ever dared tell me to do that before,’ said he, and his little eyes rolled furiously. But the girl was not afraid, and once more she commanded him to do as she bade.

And so this went on until nine Lindworm skins were lying on the floor, each of them covered with a snow-white shift. And there was nothing left of the Lindworm but a huge thick mass, most horrible to see. And the girl seized the whips, dipped them in the lye and whipped him as hard as ever she could. Next, she bathed him all over in the fresh milk. Lastly she dragged him on to the bed and put her arms around him. And she fell fast asleep that very moment.

Next morning very early, the king and the courtiers came and peeped in through the keyhole. They wanted to know what had become of the girl, but none of them dared enter the room. However, in the end they grew bolder and opened the door a tiny bit. And there they saw the girl, all fresh and rosy, and beside her lay no Lindworm, but the handsomest prince that anyone could wish to see.

The king ran out to fetch the queen, and after that there were such rejoicings in the castle as never were known before or since. The wedding took place all over again, with banquets and merrymakings for days and weeks. No bride was ever so beloved by a king and queen as this peasant maid from the shepherd’s cottage, and there was no end to their love and kindness towards her, because by her sense and her calmness and her courage she had saved their son, Prince Lindworm.

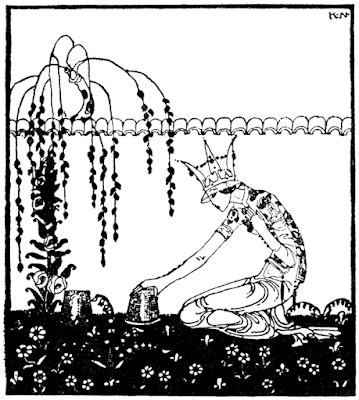

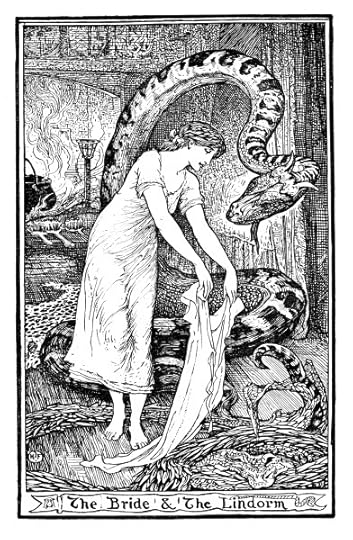

Picture credits:

Prince Lindworm, by Kay Nielsen from 'East of the Sun and West of the Moon'

The Queen lifts the drinking cup, by Kay Nielsen

Prince Lindworm, by the-sly-wink at Deviant Art: click this link

The Bride and the Lindorm, by HJ Ford

Published on July 14, 2020 03:36

July 7, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #20: MAOL A CHLIOBAIN

This story, collected by JR Campbell in ‘Popular Tales of the West Highlands’(1860) and told in Gaelic by Ann MacGillvray of Islay, is a rougher, tougher Highland version of the better known Lowland Scots fairy tale ‘Mollie Whuppie'. The heroine’s name, Maol a Chliobain, is pronounced something like: ‘Muell uh chlee pin’ – the ch sounding soft as in ‘loch’ and the ‘p’ very soft too. The second part of the name seems to mean something soft and flabby, like a cow’s dewlap, so she may have started out as one of those vivid, ugly heroines who (like Tatterhood) take no prisoners and eventually transform into beauties.And Maol a Chliobain is a fiery, determined character. When she and her two sisters set out to seek their fortunes, their mother bakes them bannocks and offers each daughter a choice between a small half-bannock and a blessing or a large half and a curse. The two eldest take the large half of the bannock and their mother’s curse; Maol a Chliobain, the youngest, takes the small half and her mother’s blessing. The two eldest try forcibly to dissuade the youngest from coming with them, but she persists. They spend the night at a giant’s house, sleeping in the same bed as his daughters, and Maol a Chliobain saves herself and her sisters by swapping the string necklaces they all wear for the amber necklaces the giant’s daughters wear. (This is not a story in which you are supposed to feel sorry for giants and their families.) She makes a getaway, throws a magic bridge of hair over a river, returns to rob the giant of various treasures, orchestrates his death…

I love the lengthening litany of challenge-and-answer between Maol a Chliobain and the giant. It not only serves to remind the listeners of all that has happened, it’s a drama in itself as the girl stands her ground and answers back, proudly owning her deeds: there was a convention that when dealing with a dangerous Otherworldly enemy, you should make sure always to have the last word. The story ends with Maol a Chliobaincompetently marrying her sisters and herself off to the sons of a rich farmer…

Or does it? JF Campbell has recorded another, slightly different telling of this story ‘very prettily told at Easter, 1859’ by ‘a young girl, a nursemaid to Mr Robertson, Chamberlain of Argyll, at Inveraray’. In this one the heroine drowns the giant. Towards the end of the telling, somebody asked, ‘And what became of Maol a Chliobain? Did she marry?’

‘Oh no,’ the girl replied, ‘she did not marry at all. There was something about a key hid under a stone, and a great deal more which I cannot remember. My father did not like my mother to be telling us such stories, but she knows plenty more –’ and the lassie departed from the parlour in great perturbation.

A key hidden under a stone! A great deal more of the story! Did she marry or didn't she...? If we only knew what happened! But maybe we're free to imagine our own endings. The storyteller's words serve to remind us (if we needed reminding) that none of these tales are set in stone. Everyone who told them would change them a little - even I, for I've tweaked it a little to make it read better. JR Campbell's version has a few passages where it's clear small points have been missed.

Vocabulary: A bannock is a cake baked on a griddle. A glave is a sword. A gillie is a manservant.

Long ago there was a widow who had three daughters, and they said to her that they would go to seek their fortune. She baked three bannocks and said to the eldest, “Which wilt thou have, the little half and my blessing or the big half and my curse?” “I like best,” said she, “the big half and thy curse.” She said to the middle one, “Which wilt thou have, the little half and my blessing or the big half and my curse?” “I like best,” said she, “the big half and thy curse.” She said to the little one, “Which wilt thou have, the little half and my blessing or the big half and my curse?”

“I like best the little half and thy blessing.”

This pleased her mother; she gave her the blessing and the two other halves as well.

The three daughters went away, but the two eldest didn’t want the youngest to be with them, and they tied her to a stone and left her; but her mother’s blessing came and freed her, and when they looked back they saw her coming with the rock on top of her! They let her alone a while, but coming to a peat stack they tied her to the peat stack and went on. But her mother’s blessing came and freed her. And when they looked back what did they see but her coming, and the peat stack on the top of her. They let her alone a turn of a while, till they reached a tree and tied her to the tree, but her mother’s blessing came and freed her, and what did they see but their sister coming with the tree on top of her! So they saw it was no good, and loosed her, and let her come with them.

On they went until nightfall. They saw a light a long way from them, but they made such speed they were not long in coming to it. When they knocked, what was this but a giant’s house! A carlin old woman opened the door: she was the giant’s mother. They asked to stay the night, she said they might, and they were put to bed with the giant’s three daughters, with a golden cloth spread over them. There were twists of knobs of amber about the necks of the giant’s daughters, and nothing but strings of horse-hair about their own necks. They all slept, but Maol a Chliobain did not sleep.

In the night, a great thirst came upon the giant. He called to his bald, rough-skinned gillie with the glave of light to bring him water, and the rough-skinned gillie said there was not a drop of water to be had. “Kill,” said the giant, “one of the strange girls and bring me her blood to drink.” “In the dark, how will I know them?” said the bald, rough-skinned gillie.

“There are twists of knobs of amber around the necks of my daughters, and nothing but twists of horsehair about the necks of the rest.”

Maol a Chliobain heard the giant, and quickly she put the horsehair strings about the necks of the giant’s three daughters, and the twist of amber knobs she put about her own neck and her sisters, and she lay down again so quietly. And the bald, rough-skinned gillie came and killed one of the giant’s daughters with the glave of light and took the blood to him. He drank it and asked for ‘MORE’, and the next one was killed. Again he asked for ‘MORE’, and the gillie killed the third one.

Maol a Chliobain woke her sisters and said there was need to be going; she took them on her back, and she took with her also the golden cloth that lay on the bed. The golden cloth cried out! The giant woke; he saw Maol a Chliobain leaving with her sisters, and he ran after her. So close was he, the sparks of fire she was putting out of the stones with her heels leapt up and struck the giant’s chin, while the sparks of fire the giant was bringing out of the stones with the points of his feet, they were striking Maol a Chliobain in the back of the head. And so they ran till they reached a river, and Maol a Chliobain plucked a hair from her head and flung it over the river to make a bridge, and she ran across the bridge and the giant could not follow.

“There thou art, Maol a Chliobain!”

“I am, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou didst kill my three bald brown daughters!”

“I killed them, though it is hard for thee.”

“When wilt thou come again?”

“I will come when my business brings me.”

They went on till they reached the house of a farmer, who had three sons. When they told what had happened to them, the farmer said to Maol a Chliobain, “I will give my eldest son to thy eldest sister, if thou wilt get for me the fine comb of gold and the coarse comb of silver that the giant has.”

“It will cost thee no more,” said Maol a Chliobain.

She went, she reached the giant’s house, she got in unseen, she took with her the combs and out she went. Loud cried the gold comb, loud cried the silver comb! The giant perceived her, and after her he went until they reached the river. She leaped the river, but the giant could not leap.

“Thou art over there, Maol a Chliobain!”

“I am, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou didst kill my three bald brown daughters!”

“I killed them, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my fine comb of gold and my coarse comb of silver!”

“I stole them, though it is hard for thee.”

“When wilt thou come again?”

“I will come when my business brings me.”

She gave the combs to the farmer, and her big sister and the farmer’s big son married. “I will give my middle son to thy middle sister, if you will get me the giant’s glave of light.”

“It will cost thee no more,” said Maol a Chliobain. Off went she, and when she reached the giant’s house, she climbed to the top of a tree that grew about the giant’s well. In the night the giant grew thirsty, and along came the bald, rough-skinned gillie with the glave of light to draw water from the well. When he bent to haul up the water, Maol a Chliobain came down. She pushed him into the well and drowned him, and she took with her the glave of light.

Loud cried the glave of light! The giant ran after her till she reached the river; she leaped the river and the giant could not cross.

“Thou art over there, Maol a Chliobain!”

“I am, if it is hard for thee.”

“Thou didst kill my three bald brown daughters!”

“I killed them, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my fine comb of gold and my coarse comb of silver!”

“I stole, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast killed my bald, rough-skinned gillie!”

“I killed, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my glave of light!”

“I stole, though it is hard for thee.”

“When wilt thou come again?”

“I will come when my business brings me.”

She reached the house of the farmer, with the glave of light, and her middle sister and the middle son of the farmer married. “To thyself, I will give my youngest son,” said the farmer, “if you will bring me a silver buck the giant has.”

“It will cost thee no more,” said Maol a Chliobain. Off she went and she reached the house of the giant, but the giant was lying in wait, and when she laid hold of the silver buck, the giant caught her.

“What,” said the giant, “wouldst thou do to me, if I had done as much harm to thee as thou hast done to me?”

Maol a Chliobain said, “If thou hadst done as much harm to me as I have done to thee, I would make thee burst thyself eating milk porridge! I would then put thee in a sack. I would hang the sack from the rooftree and and set a fire under it, and I would belabour thee with clubs till thou shouldst fall to floor like a bundle of sticks.”

The giant made milk porridge and made her drink it. She smeared the milk porridge over her mouth and face and laid herself over is as if she were dead. The giant put her in a sack, and hung it from the rooftree, and then he went away, he and his men, to fetch wood from the forest.

The giant’s carlin mother was within the house. When the giant was gone, Maol a Chliobain began – “Ah, the wonders I can see! ’Tis I that am in the light! ’Tis I that am in the city of gold. Ah, the wonders!”

“Let me in, let me see them!” said the carlin.

“I will not let you see them.”

“Let me in, let me see them!” The old woman let down the sack, Maol a Chliobain crept out and the carlin crept in. Maol a Chliobain hooked up the sack to the rooftree, took the silver buck and went away.

When the giant came back, he and his men lit the fire under the sack and set about belabouring it with their clubs. The carlin was calling, “’Tis myself that’s in it!” “I know ‘tis thyself that’s in it,” the giant kept saying as he laid on the blows. Down came the sack like a bunde of sticks and what was inside it but his own mother? When the giant saw how it was, he took after Maol a Chliobain; he followed her till she reached the river. Maol a Chliobain leaped the river, but the giant could not leap it.

“Thou art over there, Maol a Chliobain!”

“I am, if it is hard for thee.”

“Thou didst kill my three bald brown daughters!”

“I killed them, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my fine comb of gold and my coarse comb of silver!”

“I stole, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast killed my bald, rough-skinned gillie!”

“I killed, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my glave of light!”

“I stole, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast killed my mother!”

“I killed, though it is hard for thee.”

“Thou hast stolen my silver buck!”

“I stole, though it is hard for thee.”

“When wilt thou come again?”

“I will come when my business brings me.”

“If thou wert over here, and I over yonder,” said the giant, “what wouldst thou do to follow me?”

“I would stick myself down,” said Maol a Chliobain, “and I would drink and drink, and I would drink the river dry.”

The giant stuck himself down and he drank and drank until he burst. Then Maol a Chliobain and the farmer’s youngest son were married.

Picture Credits:

Maol a Chliobain is not a story which has been much illustrated, so the two illustrations to this post are from Errol le Cain's version of the story's Lowland counterpart 'Mollie Whuppie' - which is similar in plot but different in detail.

Published on July 07, 2020 02:34

June 30, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #19: THE LITTLE SEAMSTRESS

This Armenian story is a good example of a fairy tale with no fairies and no magic – but that’s more than made up for by the excellent trick the sharp-witted, poor-but-proud little heroine plays on a very gullible prince who is none of those things. His behaviour is outrageous harassment, the (doomed) ploy of a privileged, mannerless young man to get a girl’s attention. You wouldn’t think it could end well - but it does, and that’s entirely down to the heroine’s actions. Not only does she get her own back (in spades), she personally manufactures a situation in which the prince stands a good chance that his worried father will allow him to marry her. Seamstresses don’t usually marry princes – so perhaps she's had her eye on him, too!

Charles Downing who translated this story notes that the original title was Derdziki aghdjik: ‘The Tailor’s Daughter’ and that it was told in the 19th century “by a certain Ephrem Vasakian, of whom nothing but his name is known”. It was collected in Hay zhoghovrdakan heqiathner: ‘Armenian Popular Tales’ by I. Orbeli and S. Taronian. The English translation was published in the collection ‘Armenian Folk-tales and Fables’, tr. Charles Downing, OUP 1972

Once upon a time there was a tailor and his wife. They had a little daughter whom they loved dearly, and one day the tailor took his daughter and placed her with an old woman to learn how to sew.

Opposite the old woman’s house stood the royal palace, and every day the King’s son would walk up and down upon the balcony wondering what the girl looked like, and how he could get her to talk to him. For whenever she walked past, the little seamstress kept her eyes firmly on the ground and paid him no attention.

One day the prince thought of a way to make her speak to him, and he called to her from the balcony as she passed by,

“Hey there, tailor’s daughter, little bitch! How many threads are there in a piece of cloth?”

The girl did not reply.

The prince repeated his question three times, and then the little seamstress, still averting her head, said,

“Hey there, King’s son, son of a dog! How many stars are there in the heavens?” She repeated her question three times, and still she did not look up at the prince.

The prince thought and thought. How was he to play a trick on this girl and get his own back? He summoned the old woman who was teaching the girl how to sew.

“Grandmother,” said he, “I’ll give you whatever you want, but bring me to your little apprentice, so that I may give her a kiss.”

“Very well, prince,” said the old woman, “may I be a sacrifice to your head and life! Your wish is my command.”

She brought out a large, wooden chest, and next morning – without telling the little seamstress – she smuggled the prince into it and hid him, covering the top with various garments. Then she called her young apprentice:

“My child, when you have finished, put your needlework away in the large wooden chest.” The girl obeyed, and when she lifted the lid to put away her needlework, out popped the prince, who caught her around the waist and kissed her.

The little seamstress made no song and dance about it. She said nothing and went home where she lay in bed and pretended to be ill. She did not return to the old woman’s house for several days. “What shall I do to get my revenge?” she kept asking herself.

Her mother and father could see something had upset her. “Child,” said they, “what are you brooding about? Tell us what you want, and we shall do it for you if we can.”

“Father,” said the little seamstress. “Sew me a large white cloak. Make it so that only my eyes will be visible when I put it on. Stitch feathers on the back to look like angels’ wings, and cover it so thickly with little bells and baubles that there’ll be no room for even the head of a needle.”

Her father made the cloak and brought it to her. “It has given me a lot of trouble,” he said. “Try it on, my child, and let me see if it fits you.”

She put it on, flounced about and flapped the wings, and was satisfied she really did look like an angel in it. She took it off. “I am going to my sewing-mistress’s house now, and I shall not be back tonight.”

She went to the old woman’s house. “I am going to stay with you tonight,” she said. “My mother and father have had to go on a journey.”

“Very well, my child,” said the old woman. “If you want to stay here, stay.”

That night after supper the little seamstress secretly left the house and stole into the palace. While everyone was sleeping she crept into the prince’s antechamber, put on her costume and then tiptoed into the prince’s bedroom. Here she hopped about and flapped her wings, and the sound of tiny bells filled the room.

The prince opened his eyes; he saw the strange white figure standing over him and was terrified! “Ah! What are you? What do you want of me?”

“I am the angel Gabriel,” said the vision, “and I have come to take your soul!”

“I’m an only son!” cried the prince. “Take all my treasure, take my hidden gold, but do not take my soul!”

“If that’s the way of it,” said the apparition, “you shall have ten days’ grace. But I shall take a token from you in surety.”

The prince was trembling, shaking from head to foot. “Take what you wish!”

The angel picked up the prince’s golden wash-basin. “Be ready! In ten days time I shall return for your soul!” And she left.

The little seamstress took off her disguise, went home, wrapped the golden wash-basin in some old clothes and put it in a chest. Dawn broke. She sat down to work.

The prince was completely shattered by his meeting with the Angel of Death. He got up half-paralysed, then crawled out slowly on to the balcony.

“If I do have to die,” he said to himself, “I shall make that girl talk to me first.” And when she passed by he called out,

“Hey there, tailor’s daughter, little bitch! How many kisses are there in a wooden chest?”

He repeated his question three times.

The little seamstress raised her head. “Hey there, King’s son, son of a dog! How may angel Gabriels are there? How many golden wash-basins are there? How many ten days’ grace are there?”

The prince pondered these words. “The girl is an astrologer!” he said to himself. “She has read the stars and learned of my approaching death!” He went in and flung himself on his bed. “Woe is me, woe!” he wept. “I’m going to die!”

Then he began to think. “The girl knows all about my coming death, about the number of stars in the sky and about the angel Gabriel. She knows everything – I must marry her!”

He sent a valet to his father the King to tell him that he was dying, and his father and mother hurried to his bedside. “What does our kingdom lack, that you should lie there weeping?” they cried. “We shall send for a good doctor to cure you!”

“I want the tailor’s daughter in marriage,” said the prince. “Ask for her hand for me.”

“We shall fetch her!” said the King. “If she will come voluntarily, good; if not we shall make her. Anything, so long as you get better!”

He sent messengers to the tailor’s house to ask his daughter’s hand in marriage for the prince. When his daughter came home from work, her father said, “They have come from the court to ask for your hand, daughter. Do you want to marry the King’s son?”

“If you are willing to give me away, father,” said she, “I am willing to marry him.”

So the parents took the little seamstress to the palace and she was married to the prince. They were put to bed together. But her husband just lay there crying, “Woe is me, woe! I’m going to die!” and didn’t pay any attention to his new bride.

“King’s son, if you do not like me, why did you marry me?”

“Ah, tailor’s daughter!” sighed the prince, “what can I do? In six days time I am going to die!”

“If you have only six days left,” said his wife, “I am leaving you!”

She rose from the bed. She had brought her angel’s robe with her, along with her dowry and trousseau, so went out into the antechamber and donned the robe.

“My wife has left me,” wept the prince, “and I am going to die!”

Just as he said that, the girl came into his bedroom dressed in her angel’s robe with the feathery wings and the little bells, and flapped and fluttered.

“Alas!” lamented the prince. “The angel has come for me early!”

“I may as well take your soul right now!” said the angel. Then the prince fell dumb with fear and his knees knocked – and the little seamstress relented in case she frightened him to death.

“Silly boy!” she laughed – and nudged him with her elbow. “I am not the angel Gabriel. I am your wife!”

The prince could not believe it. “If you are my wife, take off that robe and let me see you!”

The little seamstress took off her disguise.

“Show me my golden wash-basin!”

The little seamstress went to the chest, took out the golden wash-basin and placed it before the prince.

“Wife, you must be a witch!” said the prince. “Tell me the truth. Are you on familiar terms with angels? Can you see the future?”

“I foresee that you will have a long life and never die – and will one day be king of this land!” said the little seamstress.

“How many stars are there in the heavens, then?” asked the prince. “For since you asked me, you must know.”

“You shall tell me the number of threads there are in a piece of cloth,” replied his wife, “for that is just the number of the stars in the heavens.”

The prince saw how he had been outwitted, and he laughed. He rose from his bed and the wedding feast went on for seven days and nights – and as they achieved their hearts’ desire, so also may you!

Picture credits:

The Little Seamstress as Angel Gabriel - illustration by William Papas, from ‘Armenian Folk-tales and Fables’, tr. Charles Downing, OUP 1972

Published on June 30, 2020 02:18

June 23, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #18: THE WOMAN OF PEACE

This fascinating story from JF Campbell’s ‘Popular Tales of the West Highlands’ (1860) opens with a mutually beneficial arrangement - perhaps of long standing - between a mortal woman and a ‘woman of peace’ from a nearby brugh or elf-mound. (Flattering circumlocutions were used when speaking of the fair folk. They didn’t like to be named, and you wouldn’t want to offend them.) Every day, the woman of peace visits a herder’s wife to borrow her kettle (a big iron cooking pot), and the herder’s wife lets her take it on condition it is returned in the evening, filled with a portion of meat and bones.

It sounds friendly, but the relationship is uneasy. It works only within a strict, formal framework. This is not like neighbours lending each other cups of flour and gossiping over the fence, it’s more like an armed truce. Make one mistake, put a foot wrong, and the bargain will be void, with penalties. Each sees the other as problematic and unsafe, each is dumb in the other’s territory. The woman of peace speaks no word to the herder’s wife, who on every visit has to repeat a kind of rhymed spell conjuring the power of the smith who forged the kettle and restating the payment required for its use. In the ‘brugh’ the roles are reversed: it's the herder’s wife who speaks no word there, while the fairy man, the old ‘carle’, employs a counter rhyming spell to challenge her and raise the alarm. “Silent wife,” he addresses her, “that came on us from the land of chase…” The meaning of ‘the land of chase’ isn't entirely clear to me (something to do with hunting?), but it sounds as if the old man regards the visitation of this mortal woman as something sudden, uncanny and perhaps dangerous.

On one level this is one of those stories where the wife leaves her husband to look after the house or perform some simple domestic task like rocking the cradle, and he makes a terrible mess of it. But most of those tales are comic fantasies designed to show men up as brash fools, helpless without their women. Although this story does that, it isn’t quite like that. It isn’t funny, it’s eerie and slightly sad. The herder’s wife is used to the silent appearance of the woman of peace and she knows the rules by which they operate. Her husband doesn’t. Maybe he listens with half a ear to what his wife tells him to say – he’s sure it will be easy – but when the woman of peace approaches, there’s something so strange about her that even her shadow terrifies him. His fearfulness and inability to speak the correct words and perform the correct ritual, brings this fragile relationship to an end, with loss to both sides.

NB: The hole in the (probably turf) roof would be to let the smoke out, and the lovely expression ‘in the mouth of the night’ means ‘in the evening’.

THE WOMAN OF PEACE

There was a herd’s wife in the island of Sanntraigh, and she had a kettle. A woman of peace would come every day to seek the kettle. She would not say a word when she came, but she would catch hold of the kettle. When she would catch the kettle, the woman of the house would say,

“A smith is able to makeCold iron hot with coal.The price of the kettle is bones,And to bring it back again whole.”

The woman of peace would come back every day with the kettle, and meat and bones in it. One day the housewife was for going over the ferry to Baile a Chaisteil, and she said to her man, “If thou wilt say to the woman of peace as I tell you, I will go to Baile Castle.”

“Ooh! I will say it, surely it’s I that will say it.”

He was spinning a heather rope to be set on the house. He saw a woman coming and a shadow from her feet, and he took fear of her. He shut the door. He stopped work. When she came to the door she did not find the door open, and he did not open it for her. She went above a hole that was in the house. The kettle gave two jumps, and at the third leap it went out at the ridge of the house. The night came, and the kettle came not.

The wife came back over the ferry, and she did not see a bit of the kettle within, and she asked, “Where is the kettle?”

“Well then, I don’t care where it is,” said the man, “I never took such a fright as I took at it. I shut the door and she did not come any more with it.”

“Good-for-nothing wretch, what didst thou do? There are two that will be ill off – thyself and I!”

“She will come tomorrow with it.”

“She will not come.”

She hasted herself and went away. She reached the knoll, and there was no one within. It was after dinner, and they were out in the mouth of the night. She went in, she saw the kettle and she lifted it. It was heavy for her with the remnants they had left in it. Then an old carle that was hidden within saw her going out, and he said,

“Silent wife, silent wifeThat came on us from the land of chase,Thou man on the surface of the brugh,Loose the black and slip the fierce.”

The two dogs were let loose; and she was not long away when she heard the clatter of the dogs coming. She kept the remnant that was in the kettle so that if she could take it with her, well, but if the dogs should come close she might throw it at them. She saw the dogs coming. She took the lid from it and threw them a quarter of what was in it: that kept them busy for a while. They were coming again, and she threw another piece at them when they closed upon her. Off she went, making all the haste she could; when she got near the farm she up-ended the pot and threw down for them all that was left in it.

The dogs of the farm struck up a-barking when they saw the dogs of peace stopping.

The woman of peace never came more to seek the kettle.

Picture credit:

A Highland Gypsy, Thomas Faed, 1870

Published on June 23, 2020 00:48

June 16, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #17: THE WATER KING AND VASILISSA THE WISE

This very long Russian fairy tale was collected by Alexander Afanasiev and translated by W.R.S. Ralston in ‘Russian Folk-Tales’ Smith, Elder, 1873. A 1945 translation by Norbert Guterman gives the title as ‘The Sea-King and Vasilissa the Wise’, but Ralston’s version is so readable I’ve stuck with him and only tweaked a few words here and there. This is just the second half of the story, effectively a tale in its own right; but here is a brief account of the first part.

A King is befriended by an Eagle, whose life he has spared out hunting. This Eagle carries the King through the air and over the sea to visit his mother and three sisters. At the end of the visit he gives the King two chests, green and red, with advice not to open them until he gets home, and provides a ship to carry him back across the sea. Pausing at an island on his voyage home, the curious King opens the red chest to find what’s in it. Out comes a vast quantity of cattle, so numerous the island barely has room for them. The King is dismayed. How will he ever put them back in the chest again?

But a man comes out of the sea. “Why are you crying?” he asks – and offers to put the cattle back in the chest if the King will give him “whatever you have at home that you don’t know about.”

Believing he knows everything of value that he has at home, the King agrees – and of course when he arrives, his wife has given birth to a baby boy. Without daring to tell her what he has promised, he opens the red chest, and out come herds of cows and oxen, and flocks of fine sheep. He opens the green chest: a wonderful garden appears. He’s so delighted he forgets his bargain. Years go by, the Prince grows into a young man, and one day, walking by the river, the King is confronted by the same man as before – who rises from the water and demands that he pay his debt.

Elements of this story will remind you of others. The assistance lent on condition of a reciprocal promise to give ‘whatever greets you on your homecoming’, or ‘the first thing you see’, or ‘the thing you carry’ – it always turns out to be a child – is a motif at least as old as the story of Jephtha’s daughter in the Old Testament. ‘Rapunzel’ comes to mind, and the beginning of the Irish tale, ‘The Woman Who Went to Hell’, (#12 in this series). The second half of the story, as you will see, follows the pattern of ‘The Mastermaid’,( #7 in this series): the heroine is the active, canny, magic-working daughter of a supernatural father - sea-king, troll, enchanter, ogre, giant, etc - who saves the hapless prince’s life, orchestrates his escape and reclaims him after he has forgotten her.

Then doesn’t this make them ‘all the same story’? No, no and no! ‘The Water King and Vasilissa the Wise’ is very different in character from the forthright Norwegian comedy of ‘The Mastermaid’. A Baba Yaga in unusually amiable mood helps the urbane Prince, perhaps because he politely calls her ‘granny’: the tasks he must perform are on a palatial scale far removed from mucking out stables or catching horses, and the episode in the bath-house is linked to Russian peasant customs (or at least Eastern European customs, since something similar is also to be found in the Romanian tale ‘Iliane of the Golden Tresses’, (#3). Though the same motifs recur in fairy tales across Europe, the resulting tales are delightfully individual variations on themes – which is all part of the pleasure.

We begin at the point where the King confesses the truth: his son is promised to the man from the sea.

The King went home full of grief and told the truth to the Queen and Prince. They mourned and wept together, but there was no help for it: the Prince must be given up. So they took him to the mouth of a river and left him there alone.

The Prince looked around, saw a footpath and followed it, trusting God to lead him. He walked and walked till he came to a dense forest: in the forest stood a hut: in the hut lived a Baba Yaga.

“Suppose I go in,” thought the Prince, and went in.

“Good day, Prince!” said the Baba Yaga. “Are you looking for work or avoiding it?”

“Eh, granny! Give me something to eat and drink first, then ask me questions.” So she gave him food and drink, and the Prince told her where he was going and for what purpose.

Then the Baba Yaga said: “My child, go to the sea-shore. You will see twelve spoonbills come flying in; they will turn into maidens and begin bathing. You must creep quietly up and steal the eldest maiden’s shift. When you have struck a bargain with her, go to the Water King; and on your way you will meet with three heroes: Obédalo [‘the Eater’], Opivalo [‘the Drinker’], and Moroz Treskun [‘Crackling Frost’] – take them with you; they’ll do you good service.”

The Prince bid the Yaga farewell. Down to the sea-shore he went, and hid behind the bushes. Soon twelve spoonbills came flying in, struck the moist earth, turned into fair maidens and began to bathe. The Prince crept from the bushes, stole the eldest one’s shift and hid again – he didn’t move an inch. The girls finished bathing and came to shore: eleven put on their shifts, turned into birds and flew away leaving only the eldest, Vasilissa the Wise. She began praying and begging the good youth.

“Do give me my shift!” she says. “I know you are on your way to the house of my father, the Water King. When you come, I will befriend and help you.”

So the Prince gave back her shift, and immediately she turned into a spoonbill and flew off after her companions. Going further on his way, the Prince met the three champions, Obédalo, Opivalo and Moroz Treskun: he took them with him and went on the Water King.

The Water King greeted him: “Hail, my friend! Why have you been so long in coming to me? I have grown tired of waiting for you. Now get to work. Here is your first task. In one night you must build me a great crystal bridge: it must be ready by tomorrow. If you don’t build it – off with your head!”

Leaving the Water King, the Prince burst into floods of tears. Vasilissa the Wise opened the window of her upper chamber. “Prince, what are you crying about?”

“Ah, Vasilissa the Wise, how can I help crying? Your father has ordered me to build him a crystal bridge in a single night, and I don’t even know how to handle an axe.”

“No matter! Lie down and sleep; the morning is wiser than the evening.”

She ordered him to sleep, but she herself went out on to the steps and called aloud with a mighty, whistling cry. From all sides, carpenters and workmen came running; some levelled the ground, others carried bricks. Soon they had built a crystal bridge and painted it with marvellous devices; then they vanished to their homes.

Early next morning Vasilissa the Wise called the Prince: “Get up, Prince! the bridge is ready; my father will be coming to inspect it.”

Up jumped the Prince, seized a broom, took his place on the bridge and began sweeping here, clearing up there.

The Water King praised him. “Thanks!” says he. “You have done me one service; now here is another. By tomorrow morning you must plant me a garden green – big and shady. It must be full of song-birds and blossoming trees, with ripe apples and pears dangling from the branches.”

Away went the Prince from the Water King, dissolved in tears. Vasilissa the Wise opened her window and asked, “What are you crying for, Prince?”

“How can I help crying? Your father has ordered me to plant a garden in one night.”

“That’s nothing! Lie down and sleep: the morning is wiser than the evening.”

She made him go to sleep, but she herself went on to the steps, called and whistled with a mighty whistle. From every side gardeners of all sorts came running, and they planted a garden green, and birds sang in the garden, flowers bloomed on the trees, and ripe apples and pears dangled from the branches.

Early in the morning Vasilissa the Wise awoke the Prince: “Get up, Prince! the garden is ready and Papa is coming to see it.”

The Prince snatched up a broom and ran to the garden. He swept a path here, trimmed a twig there. The Water King praised him and said, “Thanks, Prince! You’ve done me good and trusty service. Now choose yourself a bride from among my twelve daughters. They all look exactly alike: in face, in hair and in dress. If you can pick out the same one three times running, she shall be your wife, but if you fail I shall put you to death.”

When Vasilissa the Wise knew about this she seized the chance to say to the Prince: “The first time I will wave my handkerchief, the second time I will be arranging my dress, the third time you will see a fly above my head.” So three times running the Prince guessed which was Vasilissa the Wise, and he and she were married, and a wedding feast was got ready.

The Water King prepared so much food of all kinds that more than a hundred men could not have got through it, and he ordered his son-in-law see that everything was eaten. “If anything’s left over, the worse for you!” says he.

“My father,” begs the Prince, “there’s an old fellow of mine here. Please allow him to take a bite with us.”

“Let him come!”

At once appeared Obédalo, the Eater. He gobbled up everything in sight and even then he wasn’t full. So the Water King set out forty barrels of all kinds of strong drink and ordered his son-in-law to see that they were all drained dry.

“My father,” begs the Prince again, “there’s another old man of mine here; let him too come and drink your health.”

“Let him come!”

Opivalo the Drinker appeared, emptied all forty barrels in a twinkling, and asked for a drop more to wash it all down. The Water King saw he couldn’t win that way, so he gave orders to prepare a bathroom for the young couple – an iron bath-room! – and to heat it as hot as possible. Twelve loads of firewood were set alight, and the stove and walls became red-hot – it was impossible to come within five versts of it.

“My father!” says the Prince; ‘let an old fellow of ours go into the bath-room first for a good scrub, just to try it out.

“Let him do so!”

So Moroz Treskun – Crackling Frost! – went into the bath-room. He blew into one corner, blew into another – next moment, icicles were hanging there. The young couple followed him into the bath-room, scrubbed and steamed themselves and came home.“Let us go,” said the Prince. At once they saddled their horses and galloped off into the open plain. They rode and rode; many an hour went by.

“Jump down from your horse, Prince, and lay your ear to the earth,” said Vasilissa. “Can you hear the sound of those pursuing us?”

The Prince bent his ear to the ground but he could hear nothing. Then Vasilissa herself leapt down from her steed. She laid herself flat on the earth and said, “Ah, Prince! I hear a great noise of those chasing after us.” She turned the horses into a well and herself into a basin and the Prince into a very old man. Up came the pursuers. “Hey, old man!” said they, “have you seen a young man and maiden pass by?”

“Indeed I did, my friends, but it was long ago. Why, I was a just a young man myself at the time I saw them ride by.”

The pursuers returned to the Water King. “No trace of them at all,” they said, “no news: we saw nothing but an old man beside a well, and a basin floating on the water.”

“Why didn’t you seize them?” cried the Water King. He ordered them to be put to a cruel death and sent another troop after the Prince and Vasilissa the Wise.

In the meantime the fugitives had ridden far and fast. Vasilissa the Wise heard the noise of the fresh troop coming after them, so she turned the Prince into an old priest and she herself became an ancient church, its walls crumbling and covered in moss. Up came the pursuit. ‘Hey, old man! have you seen a young man and maiden pass by?”

“I saw them, my children! but it was a long, long time ago. I was only a young man when they rode by; it was while I was building this church.”

So the second set of pursuers returned to the Water King, saying, “Your royal majesty, there is neither trace nor news of them. All we saw was an old priest and an ancient church.”

“Why did you not seize them?” cried the Water King louder than ever, and putting the pursuers to a cruel death he galloped off himself in pursuit of the Prince and Vasilissa the Wise. This time Vasilissa turned the horses into a river of mead, with banks made of pudding, and she changed the Prince into a drake and herself into a grey duck. The Water King flung himself on the mead and the pudding, and he ate and ate and drank and drank until he burst! And so he gave up the ghost.

The Prince and Vasilissa rode on. At last they drew near to the home of the Prince’s parents. Then said Vasilissa, “Go on in front, Prince, and announce your arrival to your father and mother while I wait for you by the wayside. But remember these words: kiss everyone else, but don’t kiss your sister; if you do, you will forget me.”

The Prince reached home, greeted everyone – kissed his sister too – and no sooner had he kissed her, he forgot all about his wife. It was as if she had never even entered his mind.

Vasilissa the Wise waited for three days. On the fourth day she dressed herself like a beggar, went into the city and took up lodging in an old woman’s house. By now the Prince was preparing to marry a rich princess, and orders had been sent throughout the kingdom for everyone to bring a wheaten pie to the palace to congratulate the bride and bridegroom. So, like everyone else, the old woman began sifting flour to make a pie.

“Why are you making a pie, Granny?” asked Vasilissa.

“Why, don’t you know? The King is giving his son in marriage to a rich princess: everyone must go to the palace to serve the dinner to the young couple.”

“Well now! I will bake a pie too, and take it to the palace. Perhaps the King will give me some gift in reward.”

“Bake away in God’s name!” said the old woman.

Vasilissa took flour, kneaded dough and made a pie. And inside it she put some curds, and a pair of live doves.

Well, the old woman and Vasilissa the Wise reached the palace just as dinner was being served. What a feast it was, fit for all the world to see! Vasilissa’s pie was set on the table before the bridegroom. As soon as it was cut in half, the two doves flew out. The hen bird seized a piece of curd, and her mate said to her,

“Give me some curds too, Dovey!”

“No I won’t,” replied the other dove, “else you’d forget me, as the Prince has forgotten his Vasilissa the Wise.”

Then the Prince remembered his wife. He jumped up from the table, caught her by her white hands and seated her close to his side. And from that time on they lived together in happiness and prosperity.

Picture credit:

The Water King: Russian lacquer box painted by Aleksey Zhiryakov

Published on June 16, 2020 02:20

June 9, 2020

Strong Fairy Tale Heroines #16: THE WELL AT THE WORLD'S END

This is another story from Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’. It's told in Scots and the original spelling of the title is ‘The Wal at the Warld’s End’. It likely dates back to at least the mid 16thcentury, since a list of titles in ‘The Complaynt of Scotland’ (1548) includes one called ‘The Wolf of the Warldis End’ which is a probable misprint of this one.

I’ve anglicised the spelling just a little, but you need to know that ‘to flit’ means ‘to move’ in the context of relocating an animal to a new pasture or moving one’s abode – that ‘hecklepins’ are the sharp prickly combs used for teasing out flax – and that ‘scaud’ means ‘scalded’; I've consulted a Scottish friend who suggests that in this context it may mean 'scabby'! To ‘weird’ is to foretell or prophesy, like the ‘weird sisters’ in Macbeth.

This heroine succeeds without the assistance of any prince (the one who turns up at the end has nothing to do with the story; he's introduced simply to underline her good fortune and contrast it with her step-sister's). She is rewarded for her kindness and courtesy. But her ride 'far and far' over the wild moorland to the well at the world's end reminds me of the Lyke Wake Dirge (hear it here): it seems her adventurous journey takes her to the edge of the Otherworld.

If you would like to read more about eerie heads floating in wells, and the stories which contain them, I’ve written about some of them here: 'Haunted By Heads'.

There was a king and a queen, and the king had a daughter, and the queen had a daughter. And the king’s daughter was bonnie and guid-natured and a’body liked her; and the queen’s daughter was ugly and ill-natured, and naebody liked her. And the queen didna like the king’s daughter, and she wanted her awa’. So she sent her to the well at the world’s end, to get a bottle o’ water, thinking she would never come back.

Weel, she took her bottle, and she gaed and she gaed till she came to a pony that was tethered, and the pony said to her,

“Flit me, flit me, my bonnie May For I havna been flitted this seven year and a day.”

And the king’s daughter said, “Ay will I, my bonnie pony, I’ll flit ye.” So the pony gave her a ride ower the moor of hecklepins.

Weel, she gaed far and far, and farther than I can tell, before she came to the well at the world’s end; and when she came to the well it was awful deep, and she couldna get her bottle dipped. And as she was lookin’ doon, thinking how to do, there looked up to her three scaud men’s heads, and they said to her,

“Wash me, wash me, my bonnie May, And dry me wi’ your clean linen apron.’

And she said, “Ay will I; I’ll wash ye.” So she washed the three scaudit men’s heads, and dried them wi’ her clean linen apron; and syne [then] they took and dipped her bottle for her.

And the scaud men’s heads said the tane to the tither [one to the other] “Weird, brother, what’ll ye weird?”

And the first ane said, “I weird that if she was bonnie afore, she’ll be ten times bonnier.” And the second ane said, “I weird that ilka [each] time she speaks, there’ll be a diamond and a ruby and a pearl drop oot o’ her mouth.” And the third ane said, “I weird that ilka time she kaims her hair, she’ll get a peck o’ gold and a peck o’ siller oot o’ it.”

Well, she came hame to the king’s court again, and if she was bonnie afore,she was ten times bonnier; and ilka time she opened her lips to speak, there was a diamond and a ruby and a pear droppit oot o’ her mouth, and ilka time she kaimed her hair, she got a peck o’ gold and a peck o’ siller oot o’ it. And the queen was that vexed, she didna ken what to do, but she thought she would send her own daughter to see if she could fall in wi’ the same luck. So she gave her a bottle and telled her to gang awa’ to the well at the world’s end, and get a bottle o’ water.

Weel, the queen’s daughter gaed and gaed till she came to the pony, an’ the pony said,

“Flit me, flit me, my bonnie May For I havna been flitted this seven year and a day.”