Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 16

October 8, 2018

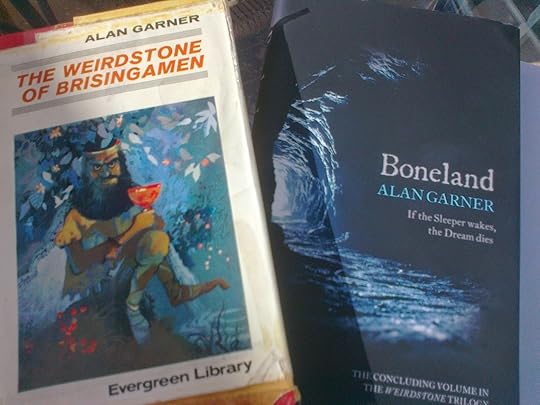

Alan Garner at Jodrell Bank

A post from the archives: Alan Garner's lecture, "Powsells and Thrums", February 2015

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell Bank

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell Bank

The lecture ‘Powsells and Thrums’, delivered by Alan Garner at Jodrell Bank on Wednesday night, was the first of a series designed to consider the nature of creativity and its importance to what Garner maintains is an arts/science spectrum – not two cultures, as CP Snow suggested, but a continuity. Powsells and thrums, he explained, are old words for the oddments of thread and scraps of cloth left over from weaving and kept for personal use: metaphors for the scraps of story and oddments of meaning which can be woven and pieced together to create something new. Which is exactly what he did in his lecture.

I’m not going to try and deliver a comprehensive report of the evening. Alan Garner spoke with wit, humour and quiet eloquence for a full hour, and I hope and trust the lecture will eventually appear in print. With many omissions, these are merely some of my impressions and memories of it – powsells and thrums, snippets and fragments which you can turn about and reshape for yourselves.

He began with a story from the introduction to Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems. Thomas tells the story of a shepherd who, asked why he made, from within fairy rings, ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a damned fool if I didn’t!’ Thomas adds, ‘These poems are written for the love of man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damned fool if they weren’t.’

Mow Cop

Mow Cop

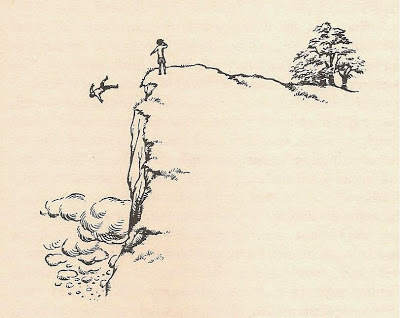

How does a story come into being? In 1956, ‘rummaging in a dustbin’, Garner saved a fragment of newspaper containing the story of two lovers who quarrelled. The boy threw a tape at the girl and stormed off. A week later he killed himself. Then she listened to the tape: it was an apology but also a threat: if she hadn't cared enough to listen to it within a week, he would conclude she didn’t love him… Nine years later, Garner heard a local story – dislocated from history – of Spanish slaves being marched north to build ‘a wall’, who ran away and found refuge on Mow Cop. Could this be a folk memory of the vanished Spanish Legion, the Ninth Hispana? Then there was the chilling history of the Civil War massacre at Barthomley Church, and finally in 1966 some graffiti at Alderley Edge station: two lovers' names and beneath them, written in silver lipstick: ‘Not really now, not any more.' Powsells and thrums: ‘Why should those words bring together all the other items? They come looking for us, or that’s the feeling.’ And so: ‘Red Shift’.

It’s not mysterious, Garner insisted. Creativity, he said, requires intelligence, which is linear and deals with the here and now – but also intuition, which is not under conscious control. Creativity is not polite: ‘It comes barging in and leaves the intellect to clean up the mess.’ Creativity, he said, is risk, and ‘without risk we can only stay as we are.’ What he proposed to give us would therefore be a collection of oddments, powsells and thrums: ‘stories rather than lecture, but woven to an end.’

‘Art interprets the inexplicable.’ The age of the universe is thirteen and a half thousand million years. How do we understand such numbers? The intellect cannot help. We must turn to stories, such as this: Far, far away there is a diamond mountain, two miles high, two miles wide and two miles deep. Every hundred years a little bird comes and sharpens its beak on the top of it, with two little strokes: whet, whet! and flies away. When by this process the entire mountain has been worn away to the size of a grain of sand – then, the first second of eternity will be at an end.

In 1957 Alan sat in his ancient farmhouse, Toad Hall, looking across the fields at Jodrell Bank’s recently completed Lovell Telescope and turning a ‘black pebble’ in his hand – a 500,000 year-old stone axe. ‘The telescope was moving – alert. It was watching a quasar… I needed to know the telescope.’ He went to see Bernard Lovell, taking with him another axe, three and a half thousand years old, beautifully polished and shaped with a hole bored through it for the haft. (Where did he find these axes? I should love to know.) With the words ‘I have something to show you,’ he dropped the axe on Lovell’s desk. ‘Thisis the telescope.’

Sir Bernard gave him a pass, understanding what he meant.

The axe is the forerunner of the telescope.

On their own, science and art hold piecemeal truths. The Garner lectures are designed to ‘repudiate the schism’ between CP Snow’s two cultures. They are part, said Garner, of what he and his wife have called ‘Operation Melting Snow.’ And, he said, ‘Sir Bernard was ahead of me. Risk taker, cosmologist, churchgoer, parish organist,’ Lovell was so distressed when the telescope was used for military purposes that he considered becoming a priest – but was dissuaded by a bishop who told him he’d be more use where he was because ‘creativity is prayer.’ And prayer, Garner said, is ‘a dialogue with the numinous. And we must give it form.’

It is impossible to look at the Lovell telescope as it in its turn looks into the deep past, and not feel a shudder of the numinous.

Science and art, the warp and the weft: both are needed to weave the fabric of human understanding.

Garner suggested we all instinctively know what is meant by a good place: a place of refuge from which we can look out in safety. His home, Toad Hall, is a ‘good place’, which is perhaps why the spot has been continuously occupied for 10,000 years. Lucky are those who have roots in such places. But also there are ‘bad places’: the valley of Glen Coe for instance, a certain church, a house in Cambridge which he enters only with reluctance. ‘And I defy you to be at ease in a multi-storey carpark.’

‘A businessman from an ancient culture said of California, “Even the light is a Hockney painting.” The land is our life force. Artists magnify the land.’ Wordsworth and Hardy interpreted and magnified the landscapes of the Lake District and Wessex with their intensity of vision. ‘Art makes people feel.’

Human beings need both refuge and prospect. We may have become human on the Pleistocene savannahs, standing up on two legs to find food and to spot danger. We recreate our places of refuge and prospect even in suburban homes and lawns. From our places of refuge we interpret the world with stories: from them we look outward, questioning, questing, looking towards ‘a different sort of pebble, waiting to be chipped.’

Art complements science, and science, art. ‘Zealots of all kinds block progress.’

Vishnu sat on a mountain top weeping. Hanuman came by. ‘What are you crying for, and what are those little ants of people down there, rushing about?’ ‘I have dropped the jewel of wisdom, and it has shattered. Everyone down there has grabbed a splinter, and each of them thinks they have the whole.’

And so at last the evening comes to an end. ‘I sit in the house in the wood, and watch the telescope and tell the stories...’ Alan Garner takes a breath. ‘I’d be a damned fool if I didn’t!’

Click here for a link to the Jodrell Bank website and a previously unpublished poem by Alan Garner: 'House by Jodrell'.

Click here for a link to the Jodrell Bank website and a previously unpublished poem by Alan Garner: 'House by Jodrell'.

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell Bank

The Lovell Telescope, Jodrell BankThe lecture ‘Powsells and Thrums’, delivered by Alan Garner at Jodrell Bank on Wednesday night, was the first of a series designed to consider the nature of creativity and its importance to what Garner maintains is an arts/science spectrum – not two cultures, as CP Snow suggested, but a continuity. Powsells and thrums, he explained, are old words for the oddments of thread and scraps of cloth left over from weaving and kept for personal use: metaphors for the scraps of story and oddments of meaning which can be woven and pieced together to create something new. Which is exactly what he did in his lecture.

I’m not going to try and deliver a comprehensive report of the evening. Alan Garner spoke with wit, humour and quiet eloquence for a full hour, and I hope and trust the lecture will eventually appear in print. With many omissions, these are merely some of my impressions and memories of it – powsells and thrums, snippets and fragments which you can turn about and reshape for yourselves.

He began with a story from the introduction to Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems. Thomas tells the story of a shepherd who, asked why he made, from within fairy rings, ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a damned fool if I didn’t!’ Thomas adds, ‘These poems are written for the love of man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damned fool if they weren’t.’

Mow Cop

Mow CopHow does a story come into being? In 1956, ‘rummaging in a dustbin’, Garner saved a fragment of newspaper containing the story of two lovers who quarrelled. The boy threw a tape at the girl and stormed off. A week later he killed himself. Then she listened to the tape: it was an apology but also a threat: if she hadn't cared enough to listen to it within a week, he would conclude she didn’t love him… Nine years later, Garner heard a local story – dislocated from history – of Spanish slaves being marched north to build ‘a wall’, who ran away and found refuge on Mow Cop. Could this be a folk memory of the vanished Spanish Legion, the Ninth Hispana? Then there was the chilling history of the Civil War massacre at Barthomley Church, and finally in 1966 some graffiti at Alderley Edge station: two lovers' names and beneath them, written in silver lipstick: ‘Not really now, not any more.' Powsells and thrums: ‘Why should those words bring together all the other items? They come looking for us, or that’s the feeling.’ And so: ‘Red Shift’.

It’s not mysterious, Garner insisted. Creativity, he said, requires intelligence, which is linear and deals with the here and now – but also intuition, which is not under conscious control. Creativity is not polite: ‘It comes barging in and leaves the intellect to clean up the mess.’ Creativity, he said, is risk, and ‘without risk we can only stay as we are.’ What he proposed to give us would therefore be a collection of oddments, powsells and thrums: ‘stories rather than lecture, but woven to an end.’

‘Art interprets the inexplicable.’ The age of the universe is thirteen and a half thousand million years. How do we understand such numbers? The intellect cannot help. We must turn to stories, such as this: Far, far away there is a diamond mountain, two miles high, two miles wide and two miles deep. Every hundred years a little bird comes and sharpens its beak on the top of it, with two little strokes: whet, whet! and flies away. When by this process the entire mountain has been worn away to the size of a grain of sand – then, the first second of eternity will be at an end.

In 1957 Alan sat in his ancient farmhouse, Toad Hall, looking across the fields at Jodrell Bank’s recently completed Lovell Telescope and turning a ‘black pebble’ in his hand – a 500,000 year-old stone axe. ‘The telescope was moving – alert. It was watching a quasar… I needed to know the telescope.’ He went to see Bernard Lovell, taking with him another axe, three and a half thousand years old, beautifully polished and shaped with a hole bored through it for the haft. (Where did he find these axes? I should love to know.) With the words ‘I have something to show you,’ he dropped the axe on Lovell’s desk. ‘Thisis the telescope.’

Sir Bernard gave him a pass, understanding what he meant.

The axe is the forerunner of the telescope.

On their own, science and art hold piecemeal truths. The Garner lectures are designed to ‘repudiate the schism’ between CP Snow’s two cultures. They are part, said Garner, of what he and his wife have called ‘Operation Melting Snow.’ And, he said, ‘Sir Bernard was ahead of me. Risk taker, cosmologist, churchgoer, parish organist,’ Lovell was so distressed when the telescope was used for military purposes that he considered becoming a priest – but was dissuaded by a bishop who told him he’d be more use where he was because ‘creativity is prayer.’ And prayer, Garner said, is ‘a dialogue with the numinous. And we must give it form.’

It is impossible to look at the Lovell telescope as it in its turn looks into the deep past, and not feel a shudder of the numinous.

Science and art, the warp and the weft: both are needed to weave the fabric of human understanding.

Garner suggested we all instinctively know what is meant by a good place: a place of refuge from which we can look out in safety. His home, Toad Hall, is a ‘good place’, which is perhaps why the spot has been continuously occupied for 10,000 years. Lucky are those who have roots in such places. But also there are ‘bad places’: the valley of Glen Coe for instance, a certain church, a house in Cambridge which he enters only with reluctance. ‘And I defy you to be at ease in a multi-storey carpark.’

‘A businessman from an ancient culture said of California, “Even the light is a Hockney painting.” The land is our life force. Artists magnify the land.’ Wordsworth and Hardy interpreted and magnified the landscapes of the Lake District and Wessex with their intensity of vision. ‘Art makes people feel.’

Human beings need both refuge and prospect. We may have become human on the Pleistocene savannahs, standing up on two legs to find food and to spot danger. We recreate our places of refuge and prospect even in suburban homes and lawns. From our places of refuge we interpret the world with stories: from them we look outward, questioning, questing, looking towards ‘a different sort of pebble, waiting to be chipped.’

Art complements science, and science, art. ‘Zealots of all kinds block progress.’

Vishnu sat on a mountain top weeping. Hanuman came by. ‘What are you crying for, and what are those little ants of people down there, rushing about?’ ‘I have dropped the jewel of wisdom, and it has shattered. Everyone down there has grabbed a splinter, and each of them thinks they have the whole.’

And so at last the evening comes to an end. ‘I sit in the house in the wood, and watch the telescope and tell the stories...’ Alan Garner takes a breath. ‘I’d be a damned fool if I didn’t!’

Click here for a link to the Jodrell Bank website and a previously unpublished poem by Alan Garner: 'House by Jodrell'.

Click here for a link to the Jodrell Bank website and a previously unpublished poem by Alan Garner: 'House by Jodrell'.

Published on October 08, 2018 02:43

October 3, 2018

The Night She Dreamed of Being a Dental Assistant

I won't even go into what else has been happening in the past week, but two notable things occurred in the world of science. Firstly a Cern physicist, Alessandro Strumia – who really looks young enough to know better – was suspended for making the deliberately provocative claim that "physics was invented and built by men”, that "men prefer working with things and women prefer working with people" and that there is "a difference even in children before any social influence" can take place. The lofty heights of physics, he implies, are not for women.

Secondly, in one of those serendipitous coincidences, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to a woman for the first time in 55 years. Canadian physicist Donna Strickland is only the third woman winner of the award, along with Marie Curie, who won in 1903 and of whom presumably even Professor Strumia may have heard – and Maria Goeppert-Mayer, a theoretical physicist who was awarded the prize in 1963 for proposing the nuclear shell model of the atomic nucleus.

Let me show you something.

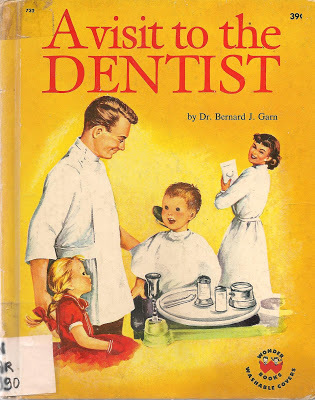

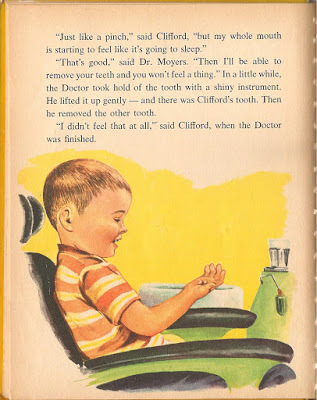

I’ve been saving this horror up for some time. It’s an educational ‘Wonder Book’ for children, published in the USA in 1959 with the laudable intention of reducing the childhood terror of going to the dentist. It’s full of cosy, colourful pictures and there is a total lack of any drama. As a nine-year old kid who once leaped out of a car to avoid a visit to the dentist, hid from my parents in bushes in a park and subsequently caught the bus home on my own, I can appreciate this aim… but let us follow Kathy and Clifford on their adventure.

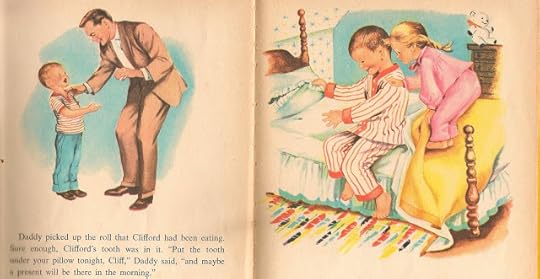

On page one, Clifford – who looks about six – loses a front tooth. ‘Everyone, including Clifford, laughed.’ This is only a baby tooth, but it prompts Daddy to tell Clifford he should put the tooth under his pillow, ‘and maybe there will be a present there in the morning’. (There will be a shiny new dime, though no mention of anything frivolous like tooth fairies). And Mommy remembers, ‘It’s time we saw Dr Moyers to have Clifford’s teeth checked. It would be a good idea to have Kathy’s teeth checked too.’ Notice how Kathy is an afterthought and everyone is looking at Clifford. Everyone looks at Clifford on the cover illustration too. And below, Kathy looks on as Clifford discovers his dime...

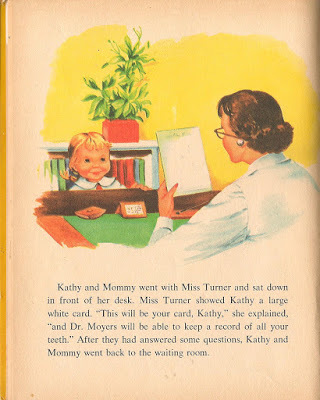

A week later, the children and Mommy arrive at the dentist’s. “Who is this pretty little girl?’ asks dental assistant Miss Turner. “This is my daughter Kathy,” says Mommy. “She is three years old and Dr Moyers is going to examine her teeth too.” Even though Kathy is for once the subject, in the picture Clifford is still the focus of attention. His hand is out, and since he is speaking to Miss Turner, it appears very much as though she is looking at him while Kathy stares up, dumb.

Miss Turner wears no glasses to greet the children, but she has to put them on for work, no matter whether close-up or distant – because wearing glasses makes a woman look serious. Here she is in one of only three pictures in the book in which Kathy is the focus. Even then it's not entirely clear whether she's looking at Kathy, or her notes.

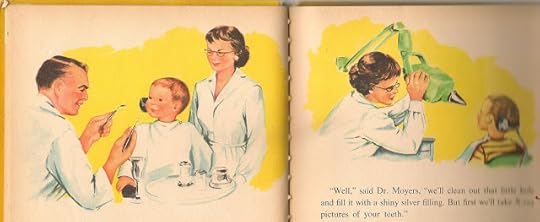

Clifford is the first to go in. He sees ‘a bright sparkling room with all kinds of wonderful machines.’ American hero Dr Moyers smiles and shakes hands with Clifford in a man-to-man fashion. ‘Sit down in the chair,’ he says, ‘and I’ll give you a ride.’ Clifford climbs into the chair with a giggle, ‘pretending that he was about to blast off in a space ship.’

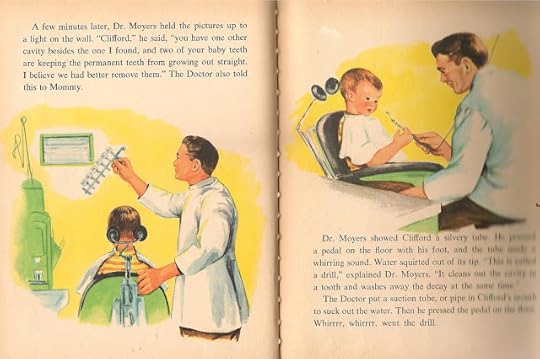

In the next few pages, Dr Moyers carefully explains to Clifford everything he is doing. He finds a small cavity. Then he asks Miss Turner to take an X-ray or six, finds a second cavity and decides to remove two more baby teeth to allow Clifford’s adult teeth to grow straight. He gives Clifford advice on dental hygiene. Miss Turner mixes the dental cement. In the left-hand picture, below, the 'space' references are clear. The X-ray pictures look like an antenna while Clifford is the astronaut in his chair.

Pretty soon Clifford has two more teeth in his chubby little hand. He looks thrilled. Two more shiny dimes!

Now it’s Kathy’s turn. Although she’s only three, Dr Moyers still takes X-rays of her teeth, but they are perfect (at three years old you’d hope so), so all he needs to do is polish them.

Kathy doesn’t fantasise about space ships or notice shiny machinery, but she does wish she had a ‘toothbrush with a motor’ at home. Dr Moyers provides more good advice on daily dental hygiene (‘Brush your teeth in the morning, then right after meals and before you go to sleep’) and the children trot off, happy to have been given new toothbrushes and medals ‘for being good patients.’ Notice how the artist makes Clifford look straight at the reader with a cheerful gappy grin. Kathy admires her good conduct badge with sweet expression and lowered eyes.

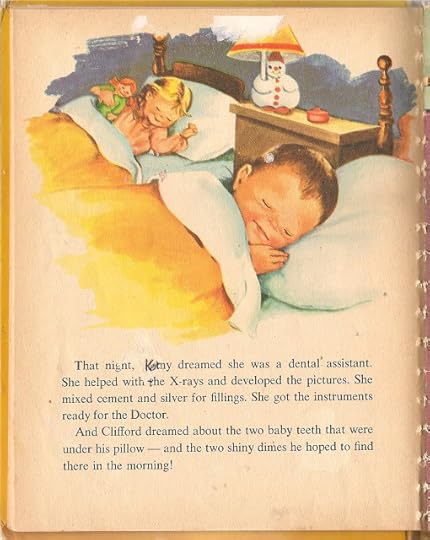

Though this book does a good job of carefully explaining dental procedures to children, it is very much of its time. The thing that really gets me, though - and the reason I feel this book is pernicious - comes on the last page where we see the children snuggled up in bed after their adventurous day, Clifford in the foreground, of course. “That night,” the story continues:

That night, Kathy dreamed she was a dental assistant. She helped with the X-rays and developed the pictures. She mixed cement and silver for the fillings. She got the instruments ready for the Doctor.

"She got the instruments ready for the Doctor." This is a book in which the little boy is older, the little girl younger. The boy sees exciting shiny machinery and imagines himself a spaceman. The little girl imagines herself a dental assistant. The boy has to be brave, have teeth drilled and extracted, is rewarded with dimes. The little girl follows in her brother’s footsteps and nothing particular interesting happens to her. The insidious, subliminal message would have sunk into the perceptions of children of both sexes, manipulating, and in the case of girls limiting, their expectations.

The book is nearly sixty years old. I feel sure the people who put it together felt fine about suggesting ‘dental assistant’ instead of ‘dentist’ as a possible career for a girl, even though women had been getting medical degrees in the States for 110 years already, ever since Elizabeth Blackwell's in 1849. They didn't see that. It wasn't relevant. Even on the cover, the male Doctor is in the foreground, his attractive female assistant remains in the background, smiling and supportive. This was the kind of myopic cultural fog in which most women over the age of fifty grew up and its effects are quite clearly still with us. The events of this week along with many another - just yesterday I heard a Conservative Party donor, Lord Ashcroft, speak unthinkingly of 'the voter and his family' - show how far we still have to travel. For it's certain that Lord Ashcroft is not alone in thinking of a voter as a man. A man and his vote, a man and his family.

Published on October 03, 2018 02:53

September 27, 2018

Fairy- and folk-tales at the BBC Proms

I promised I would be writing more on this blog this summer, instead of which I'm in the middle of writing another book. And there have been other very pleasant interruptions, such as being asked to speak at one of the Proms Extra talks - this was in conjunction with a performance of some of Ravel's most gorgeous fairy-tale inspired music: Contes de ma mère l'Oye, Scheherezade, and L'Enfant et les Sortileges, under the baton of Simon Rattle. In the photo above, there's myself on the right and the composer Kerry Andrew in the middle, doing sound checks with presenter Rana Mitter before the talk in Imperial College Student Union Hall, close to the Albert Hall. Kerry's debut novel 'Swansong' is based on a Scottish fairy ballad, and here she is performing outdoors, live, a wonderful version of the folksong 'The Cutty Wren'.

It was lovely to meet her, and once we got started up there on the platform we could probably have gone on talking all night... If you'd like to hear us, click the BBC iplayer link, here:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio/play/p06j2938

I will posting more regularly again, now autumn's here.

Published on September 27, 2018 01:36

June 19, 2018

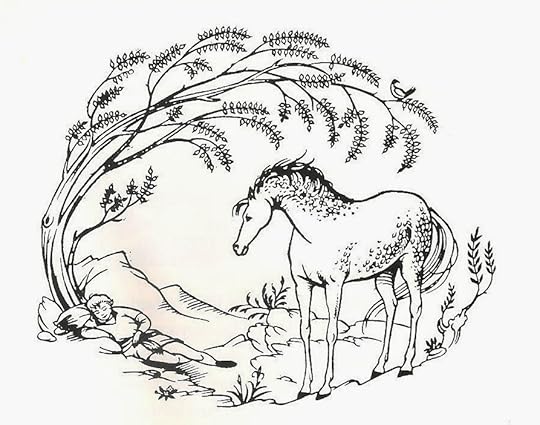

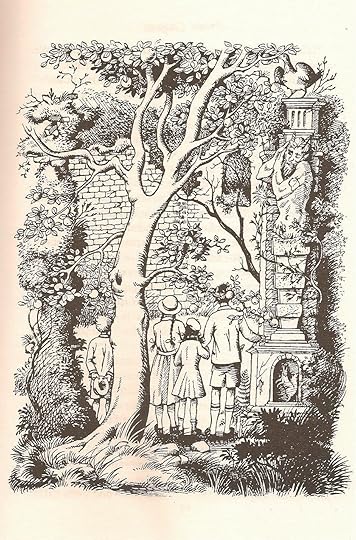

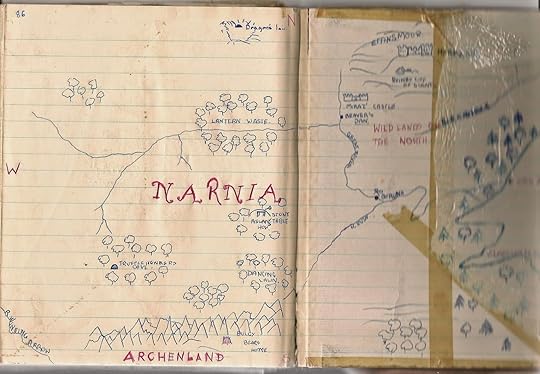

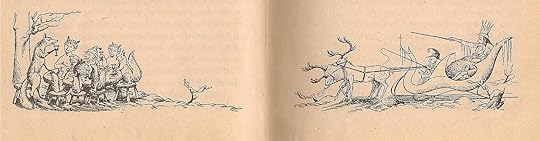

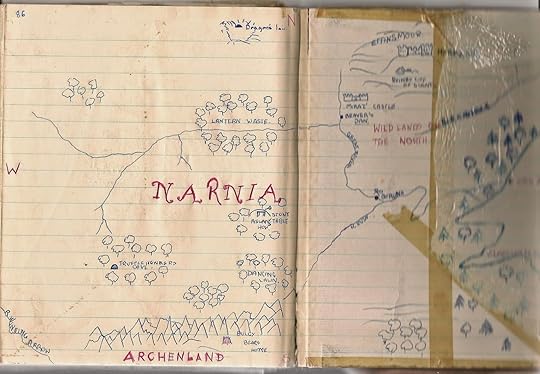

Re-reading Narnia: 'The Horse and His Boy'

I've been down with an 'orrible cough for the past month (so unfair in summer!) and once again the blog has been neglected. Now I'm back, I realise I forgot to repost my essay on 'The Horse and His Boy' - and as I haven't yet got around to finishing the one about 'The Last Battle' - I'll get there, I promise - here's this to be going on with.

This, the fifth Narnia book in order of publication, is the one I’ve thought about least since childhood. And it was never one of my particular favourites, which seems odd considering that next to Narnia, ponies were my passion. A book which combined Narnia and horses ought to have been a big hit.

This, the fifth Narnia book in order of publication, is the one I’ve thought about least since childhood. And it was never one of my particular favourites, which seems odd considering that next to Narnia, ponies were my passion. A book which combined Narnia and horses ought to have been a big hit.

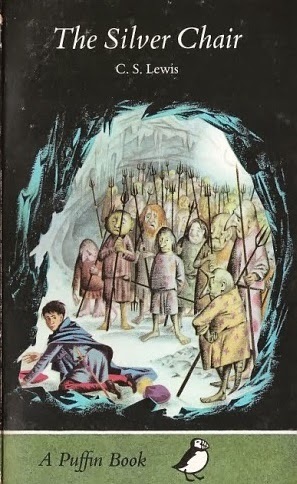

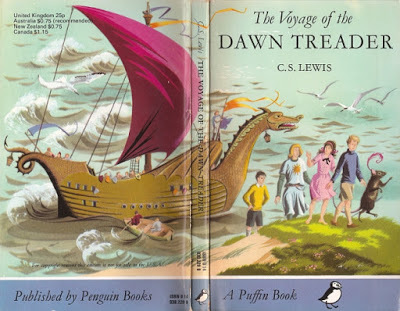

I enjoyed the book, but I didn’t love it the way I loved The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair. This may be because it’s the least complex, least layered of the Seven Chronicles. It’s a simple adventure story offering straightforward pleasures: appealing characters, obnoxious villains, touches of humour, an arduous journey and a nick-of-time rescue. What it doesn't offer – alone among the Narnia books – is anything much in the way of strong emotion, wonder or awe. Certainly nothing to match the moment when the Stone Table cracks in two, or when Reepicheep’s coracle vanishes over the crest of the wave at the end of the world, or the brilliant birds fluttering in the trees at the top of Aslan’s holy mountain, or the poignant death of old King Caspian. To use Lewis’s own words, I can find no ‘stab of joy’ in The Horse and His Boy. On this re-reading I was entertained and amused by the book, but seldom moved.

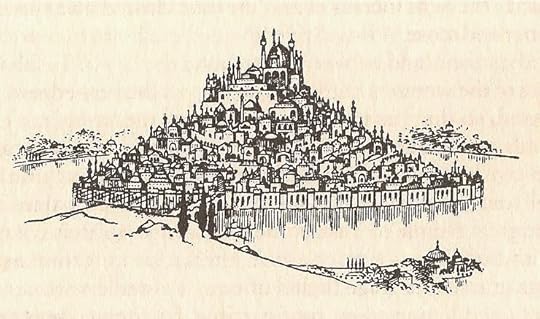

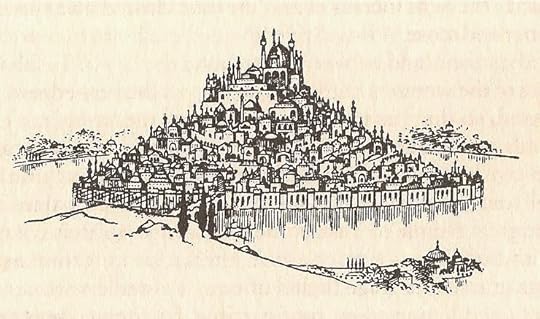

Told throughout from within – from the point of view of characters who were born in Narnia rather than in our world – The Horse and His Boy is set during the ‘golden age’ when the four thrones of Cair Paravel are filled by the four children of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. The hero of the book, the boy Shasta, has grown up to the age of perhaps twelve believing himself the son of Arsheesh, a poor fisherman in the southern land of Calormen, a country which will remind most readers of the Persia of the Arabian Nights. And we run into an immediate difficulty. The dark-skinned Calormens are depicted in a way that strikes me now as at best naively Orientalist, at worst upsettingly racist.

In an essay called ‘The Revolution in Children’s Literature’ (The Thorny Paradise, Writers on Writing for Children, ed. Edward Blishen, Kestrel 1975) the children's writer Geoffrey Trease recalled the sexism and racism prevalent in children’s books during the first half of the 20thcentury and rather bravely illustrated it with a toe-curlingly inappropriate extract from a story written by himself as a schoolboy in 1923:

‘The white dog!’ hissed the Arab leader, and his scimitar grated against my cutlass… I saw the dark triumphant face of my antagonist, the curved beam of reflected light raised to strike, and like a flash I ducked, and striking upwards with my left hand, administered a thoroughly British uppercut. And, because an Oriental can never understand such a blow, he reeled back, a look of almost comical surprise on his face. Ere he could recover, I lunged out with my cutlass and stretched him dead upon the ground.

While you’re recovering: I have a theory that classic children's books have a half-life of about fifty years of being read by actual children (after a century, most are relegated at best to academic study). They last this long mainly because adults give or read to children the books they themselves remember, and because books are durable physical objects that may sit for decades on dusty shelves to be pulled out by voracious young readers. This is how I gobbled down the jingoistic and now practically unreadable works of GA Henty, written in the last third of the nineteenth century. What modern ten year-old could tolerate ‘Under Drake's Flag, A Tale of the Spanish Main' (1883) or 'By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War' (1884)? They were eighty years old by the time I was reading them in the 1960s and surely I must have been in the last generation of children who could possibly have enjoyed them. But the sixty year-old Narnia stories are very much with us, kept alive like the Velveteen Rabbit by the love of real children. Henty's prejudices may no longer matter, but those of CS Lewis are still of concern. And I can't help feeling he should have known better. As an adult, Geoffrey Trease set out to combat the prejudice he’d parroted as a boy. His historical novels for children, like ‘The Red Towers of Granada’ (1966), are deliberately respectful of ‘other’ cultures like those of Judaism or Islamic Spain. In spite of his efforts, the range of literature available to me growing up in the sixties was still crammed with dodgy foreigners, cunning, or comic, or cowardly, or cruel. I noticed, without realising it was unfair. So long as an author spins a good story, children are accepting readers.

Lewis first introduces the Calormen in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

Two merchants of Calormen … approached. The Calormen have dark faces and long beards. They wear flowing robes and orange-coloured turbans, and they are a wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient people.

‘Wise, wealthy, courteous and ancient’ are all very well until we reach that word ‘cruel’: in its company all other virtues are contaminated. Lewis continues:

They bowed most politely to Caspian and paid him long compliments, all about the fountains of prosperity irrigating the gardens of prudence and virtue – and things like that – but of course what they wanted was the money they had paid.

The Calormen’s flowery language is critiqued in THHB as the language of insincerity, especially compared to the white-skinned Narnians’ free, frank speech. (Note that interesting word ‘frank’, with its derivation from the founders of western culture.) From the outset Lewis leaves no doubt that Calormen culture and society is morally inferior. One has only to look at the relationship between Shasta and his foster father Arsheesh to see how Lewis puts his hand in the scales. The fairytale motif of ‘noble baby set adrift’ is found world-wide, from Moses, to Perseus, to Perdita in The Winter’s Tale, and in most of these stories the foster parent, whether humble fisherman or noble princess, rescues and raises the child with unselfish tenderness. Lewis inverts this tradition. Arsheesh self-servingly explains to the Tarkaan who wishes to buy Shasta:

‘“Doubtless,” said I, “these unfortunates have escaped from the wreck of a great ship, but by the admirable designs of the gods, the elder has starved himself to keep the child alive, and has perished in sight of land.” Accordingly, remembering how the gods never fail to reward those who befriend the destitute, and being moved by compassion (for your servant is a man of tender heart) – ’

‘Leave out all these idle words in your own praise,’ interrupted the Tarkaan. ‘It is enough to know that you took the child – and have had ten times the worth of his daily bread out of him in labour, as anyone can see…’

There’s no love or tenderness between Arsheesh and Shasta: the latter is simply relieved to learn that he’s not the fisherman’s own flesh and blood. He even dreams of possible advancement (‘the lordly stranger on the great horse might be kinder to him than Arsheesh’). Lewis soon dispels this dream, and leaves an adult reader in some discomfort as to why this Tarkaan has suddenly taken a fancy to buy Shasta.

‘This boy is manifestly no son of yours. For your cheek is as dark as mine but the boy is fair and white like the accursed but beautiful barbarians who inhabit the remote north.’

Admiration for despised beauty is never a good sign. What is Bree the Talking Horse implying, when he warns Shasta in the strongest terms that the Tarkaan is bad – ‘Better be lying dead tonight than go to be a human slave in his house tomorrow’? Aged ten I simply assumed ‘hard work and beatings’. Now I wonder whether this might truly be a 'fate worse than death'.

Orientalism is a term employed by Edward Said to critically examine patronising Western perceptions of the East: it marks a subset of racism which views Eastern cultures as despotic, fanatic, mysterious, 'inscrutable' and inferior. Lewis’s characterisation of the dark-skinned Calormen, quoted above, as ‘wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient’ could be a textbook example. If Trease overcame his early conditioning, why couldn’t Lewis? Yes, there is Aravis, yes there is the gentle and courteous knight Emeth in The Last Battle. They remain exceptions.

But there is more going on. Narnia is a paradise of happy magical creatures and talking animals. By contrast, Calormen is a grown-up country of farms and roads, a religion and a class structure, a bureaucracy, a literature, slaves and soldiers and cities. Despite its supposed Arabian Nights exoticism, from a child’s perspective Calormen is a dull place.

How come? Where are all those flying carpets*, magical rings, terrifying jinni, sorcerers and enchantresses with which Scheherezade filled the Thousand and One Nights? Lewis ditched them all. He borrowed the trappings of the Arabian Nights but left out all the magic.

Shasta was not at all interested in anything that lay south of his home because he had once or twice been to the village with Arsheesh and he knew that there was nothing very interesting there. In the village he only met other men who were just like his father – men with long, dirty robes, and wooden shoes turned up at the toe, and turbans on their heads, and beards, talking to one another very slowly about things that sounded dull.

It’s not as though the Narnia books haven’t already carried us to foreign lands. The wilds of Ettinsmoor, the depths of Bism, the numinous islands of the Eastern Sea – these belong, these fit within the Narnian fairy world. But Calormen isn’t a fairytale land. It exists to oppose Narnia’s every quality. If Lewis had wanted, he could have incorporated peris and griffins, flying carpets and sphinxes into his story, but he didn’t want. Not even the ghouls of the Tombs are ‘real’.

In a fantasy series which happily blends classical and Norse mythologies, medieval legends and talking animals, why did Lewis instinctively (I doubt he thought about it) strip all the magic from the Arabian Nights? Where else in the Narnian world does this failure of enchantment occur? Answer: on the unmagical Lone Islands, in the least interesting episode of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, where the Calormen trade for slaves – and in King Miraz’s Narnia, where the only town, Beruna, is demolished by Aslan and the personified powers of nature, a destruction significantly presented as a restoration. Narnia at its most Narnian is a place of joyful and magical disorder, a place in which there is no need for rules because no one wants to do anything bad. It owns no villages like Shasta’s, no cities, no roads. Cair Paravel is a stand-alone fairytale castle. King Lune’s castle of Anvard in Archenland is similarly isolated.

Unlike the threat posed by the magical White Witch and Green Lady, the threat to Narnia from Calormen (and the Telmarine rule of Miraz) is a divorce from magic. The Calormen are enemies of the imagination, enemies of fairyland itself. Their rule would destroy Narnia's magic, substituting an order of economics, progress, trade, politics, scepticism: necessary but unromantic things which Lewis didn’t like and didn’t want in his fairy paradise. The be-turbaned, Arabian Nights-style Calormen represent these values however, only because Lewis chose they should. Historically it was the West which imposed its industrial and political values upon the rest of the world.

In some conservative Christian circles CS Lewis is the logic-chopping wielder of the Sword of Truth. But he could and did allow prejudice to blind him. No doubt at the back of his mind was the medieval clash between Islam and Europe: the Matter of France, the Song of Roland, the Battle of Lepanto. Compared with the magic of the pagan Greek myths (so important a component in western education as, paradoxically, to have become a part of Christian European identity) I suspect Lewis felt deep in his bones that the magic of the Arabian Nights was foreign,inimical, incompatible with Aslan’s. So he left it out, but his depiction of the Calormen people creates all sorts of problems. They are undoubtedly human, so where have they come from? Are they, like Peter and Edmund, Susan and Lucy, ‘sons of Adam and daughters of Eve’ - originally from our world? When Aslan sang Narnia into existence in The Magician’s Nephew, did he create the Calormen too? He made their land: Polly and Digory glimpse the desert sands from Fledge's back. And what about their gods, Zardeenah, Azaroth and Tash? There'll be more to say about these questions when we come to The Last Battle.

For now, though, on with the story!

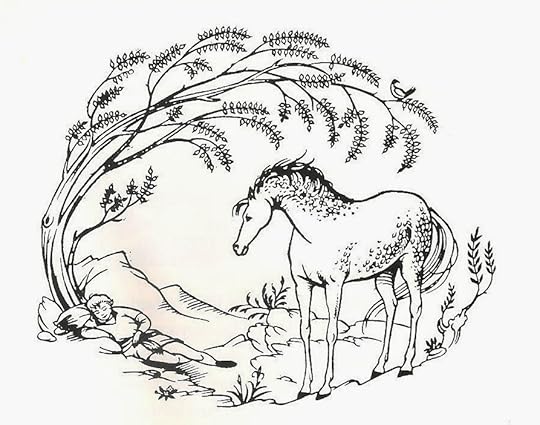

One of the things I truly loved about this book was the relationship between Shasta and Bree, the Narnian Talking Horse who, like Shasta, was kidnapped as a little foal.

“My mother warned me not to range the southern slopes, in Archenland and beyond, but I wouldn’t heed her. And by the Lion’s Mane I have paid for my folly. All these years I have been a slave to humans, hiding my true nature and pretending to be dumb and witless like their horses.”

A pony-mad little girl, I found the story of Shasta being taught to ride by his horse enchanting (“No one can teach riding so well as a horse”). Bree, or to give him his full name, Breehy-hinny-brinny-hoohy-hah – is a superb character. I loved and still love his good-humoured disdain for Shasta and for humans in general (“What absurd legs humans have!”) and his bracing lack of sympathy for Shasta’s aches and pains (“It can’t be the falls. You didn’t have more than a dozen or so.”). An experienced war-horse, Bree takes initial charge of the escape, but as the adventure continues it is the inexperienced Shasta who begins to make the difference, while Bree allows vanity and insecurity (would a true Narnian Talking Horse enjoy a good roll?) to undermine him.

Bree sees that escaping together will improve both their chances: he won’t be chased as a stray, and on his back Shasta can ‘outdistance any other horse in this country.’ With a final bit of riding advice from the Horse to his Boy, off they go:

“Grip with your knees and keep your eyes straight ahead between my ears. Don’t look at the ground. If you think you’re going to fall just grip harder and sit up straighter. Ready? Now: for Narnia and the North.”

One night after ‘weeks and weeks’ of journeying, Bree and Shasta hear another horse and rider accompanying them northwards between the forest and the sea.

“Ssh!” said Bree, craning his neck around and twitching his ears... “…That’s not a farmer’s riding. Not a farmer’s horse either. Can’t you tell by the sound? …I tell you what it is, Shasta. There’s a Tarkaan under the edge of that wood. Not on his war horse – it’s too light for that. On a fine blood mare, I should say.”

'Craning his neck around and twitching his ears': Lewis never forgets that Bree is a horse.

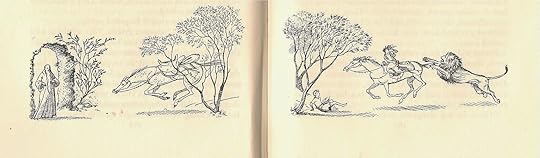

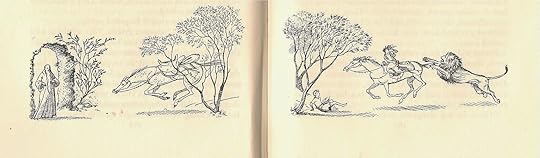

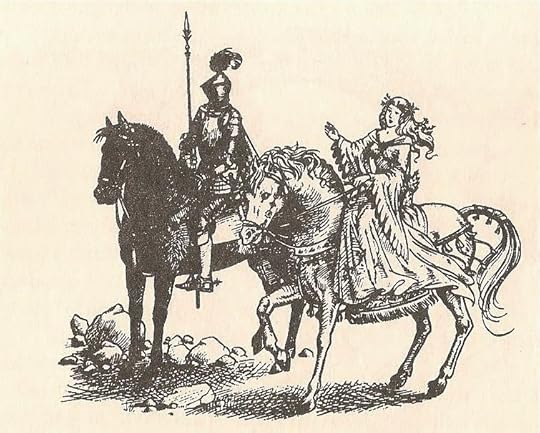

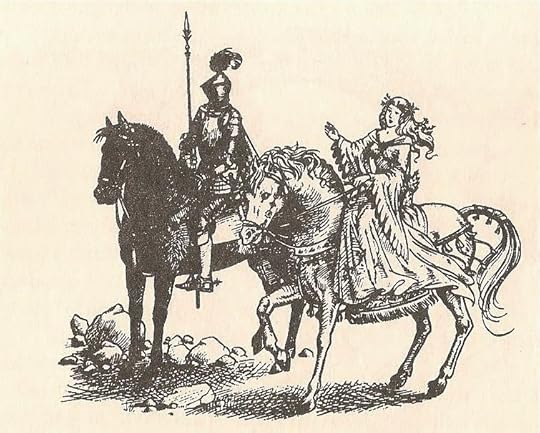

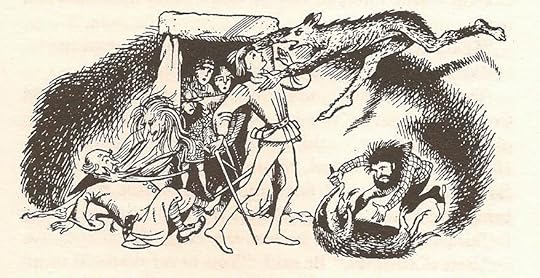

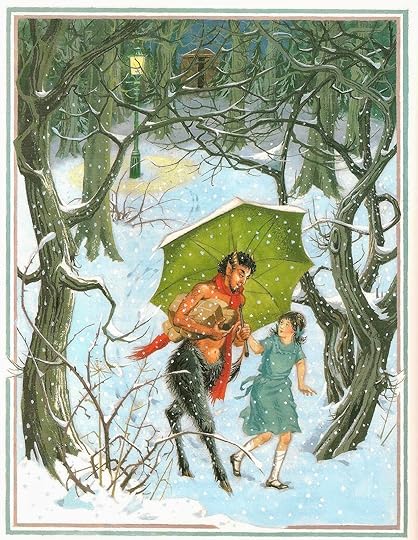

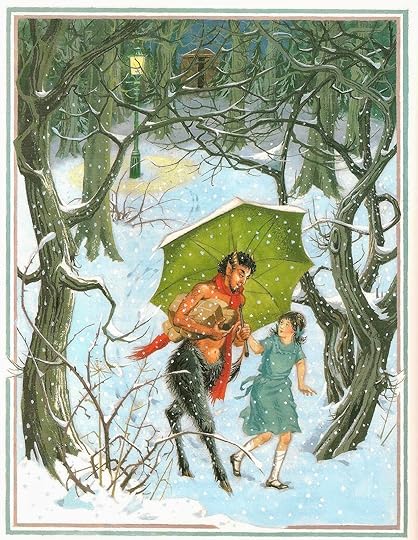

The strange ‘horseman’ seems as eager to avoid them as they are to avoid him, but lions attack. The two horses are driven together in a mad gallop across the sands, and the young rider – described as a ‘small, slender person, mail-clad … and riding magnificently’ is revealed as a girl, Aravis, with ‘her’ Talking Horse, Hwin. It’s a dramatic entrance, and Aravis takes no prisoners from the start.

“Broo-hoo-hah!” [Bree] snorted. “Steady there! I heard you, I did. There’s no good pretending, Ma’am. …You’re a Talking Horse, a Narnian horse, just like me.” “What’s it got to do with you if she is?” said the strange rider fiercely, laying hand on sword-hilt. But the voice in which the words were spoken had already told Shasta something. “Why, it’s only a girl!” he exclaimed. “And what business is it of yours if I am onlya girl?” snapped the stranger. “You’re only a boy: a rude, common little boy – a slave probably, who’s stolen his master’s horse.”

When the book was written fifty years ago, this ‘only a girl’ thing was everywhere, a universal pollutant we all breathed. In Little Women, in What Katy Did – in Enid Blyton’s books about the Famous Five, even in Geoffrey Trease – my friends and I encountered heroines who wished they were boys, and we didn’t always understand that this wasn’t because boys were naturally superior, but because society privileged them with better choices and opportunities. So it was great to meet competent, confident Aravis who rode a horse the way I wished I could, and wore a sword too. And when Shasta comes out with this classic put-down, ‘only a girl’, Aravis annihilates him. Later in the book, when Hwin quietly suggests it would be wise for them to keep going, Bree retorts crushingly: 'I think, Ma'am... that I know a little more about campaigns and forced marches and what a horse can stand than you do'. (Stallionsplaining!) And Hwin shuts up because she is 'a very nervous and gentle person who was easily put down.' But Hwin is right and Bree is wrong, and his decision is a bad one. In my mind, Lewis is certainly an equal-opportunities author.

This is as I’ve said, an adventure story, and it’s linear: Shasta and his friends must get from A (Calormen) to B (Narnia). It's an escape rather than a quest. We already know what Narnia is like (or we do if we’ve read the other books) so all the surprises, all the plot interest have to come from twists and turns and picaresque interludes along the way. The first is when Aravis relates her escape, and for once Lewis, via Bree, has something good to say about the formal and flowery Calormen narrative style (the sort of thing we expect of 'Eastern' tales but perhaps actually an artefact of Western translations: in her 2013 edition of The Thousand and One Nights, Hanan Al-Shaykh praises the original's 'flat, simple style'). However:

Bree… was thoroughly enjoying the story. “She’s telling it in the grand Calormen manner and no story-teller in a Tisroc’s court could do it better…”

Aravis’ story is effectively another fairytale: cruel stepmother persuades weak father to marry his daughter to a rich old man. In despair, Aravis is about to kill herself when Hwin her mare ‘magically’ begins to talk – the Animal Helper motif of so many fairystories – and to tell her about

The woods and waters of Narnia and the castles and the great ships, till I said, “In the name of Tash and Azaroth and Zardeenah Lady of the Night, I have a great wish to be in that country of Narnia.” “O my mistress,” answered the mare, “if you were in Narnia you would be happy, for in that land no maiden is forced to marry against her will.”

Aravis hatches a plot.

I put on my gayest clothes and sang and danced before my father and pretended to be delighted with the marriage which he had prepared for me. Also I said to him, “O my father and O the delight of my eyes, give me your licence and permission to go with one of my maidens alone for three days into the woods to do secret sacrifices to Zardeenah, Lady of the Night, as is proper and customary for damsels when they must bid farewell to the service of Zardeenah and prepare themselves for marriage.”

Here Lewis recalls a very dark Old Testament story (Judges 11, 34-39) when the warrior Jephthah, in another ancient fairytale motif, bargains with God for victory over his enemies in exchange for a burnt offering of the first thing that greets him on his return home:

And Jephthah came to Mizpah unto his house, and, behold, his daughter came out to meet him with timbrels and with dances; and she was his only child… And he rent his clothes, and said, Alas, my daughter! thou hast brought me very low… for I have opened my mouth unto the Lord and I cannot go back. And she said unto him, My father, if thou hast opened thy mouth unto the Lord, do to me according to that which hath proceeded out of thy mouth. … And she said unto her father, Let this thing be done for me: let me go alone two months that I may up and down upon the mountain and bewail my virginity, I and my fellows. And he said, Go. And he sent her away for two months: and she went with her companions and bewailed her virginity upon the mountains. And it came to pass at the end of two months that she returned unto her father, who did with her according to his vow which he had vowed.

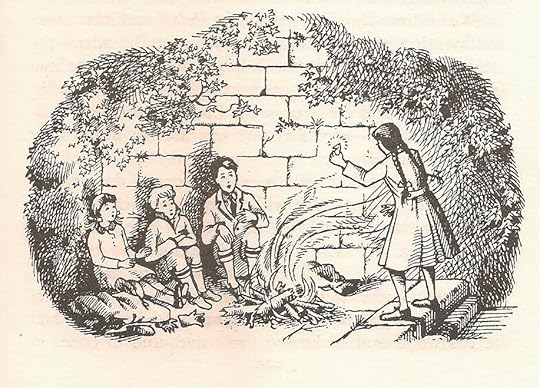

In this case Lewis redeems the story. Aravis does what we might all wish Jephthah’s unnamed daughter could have done. She tricks her father, obtains three days grace, drugs her maid, dresses in her brother’s armour and races for Narnia on Hwin – covering her tracks further by sending her father a letter as if from her betrothed husband claiming to have married already after a chance meeting in the woods. Aravis displays from the beginning great competence, cool-headedness and fortitude: she is, as Lewis later comments, ‘proud and could be hard enough but… as true as steel’. What she doesn’t have is empathy: it is left to Shasta the underdog to wonder what might have happened to the maid Aravis drugged and left behind.

“Doubtless she was beaten for sleeping late,” said Aravis coolly. “But she was a tool and spy of my stepmother’s. I am very glad that they should beat her.” “I say, that was hardly fair,” said Shasta. “I did not do any of these things for the sake of pleasing you,” said Aravis.

When I first read this book I can’t say that the fate of the maid upset me very much, and I appreciated tough, unsympathetic Aravis who does the necessary without wringing her hands. The adventure story is a genre which requires a brisk pace and little consideration of those who fall by the way or get in the way. But of course this isn’t your average adventure story and Lewis has a moral agenda. He wants his child readers to notice the collateral damage. Aslan is watching, and Aslan will repay – an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth:

“The scratches on your back, tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood, were equal to the stripes laid upon the back of your stepmother’s slave because of the drugged sleep you cast upon her. You needed to know what it felt like.”

“Tear for tear, throb for throb, blood for blood.” Does Aslan punish Aravis because her action got the slave-girl into trouble? No, it's because she wasn’t sorry about it and didn’t care. Aravis’ punishment cannot help the slave-girl, who will never even hear of it. “You needed to know what it felt like”: this is about Aravis herself, to correct a flaw in her character and teach her to empathise. It seemed fair to me as a child. (“Children, who are innocent, love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy,” GK Chesterton said.) But now? Now I think this is penny-in-the-slot justice. You do something bad: something bad happens to you: end. How neat it would be if, as Jesus said, ‘With what measure ye mete it shall be measured to you again’, but it doesn’t work that way in life and even if it did, where is the victim in this? Aslan lays no responsibility on Aravis to consider that slave-girl again, or to try and help her. In fact he discourages her from doing so, saying as he often does that it is ‘not your story’. Again: this is an adventure story and most adventure stories would never raise the issue of ‘what happened to the slave girl?’ in the first place – but having raised it, Lewis doesn’t seem to me to deal with it well. Aravis doesn't have to do anything but accept her lesson and grow in compassion and understanding. Oh, and trust in Aslan to see the slave-girl right... Isn't that just as self-centred? It’s easy but dangerous to relinquish earthly justice to one’s notion of the divine. Where was justice for Jephthah’s daughter? I don’t like Aslan very much, in this book.

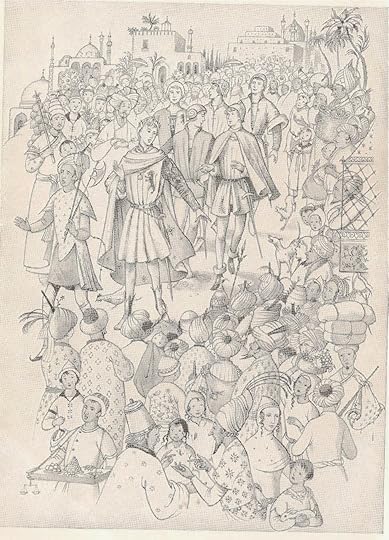

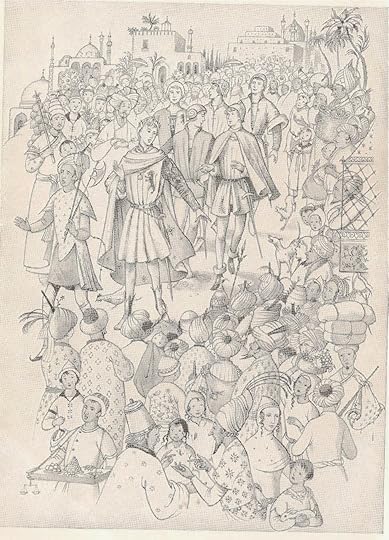

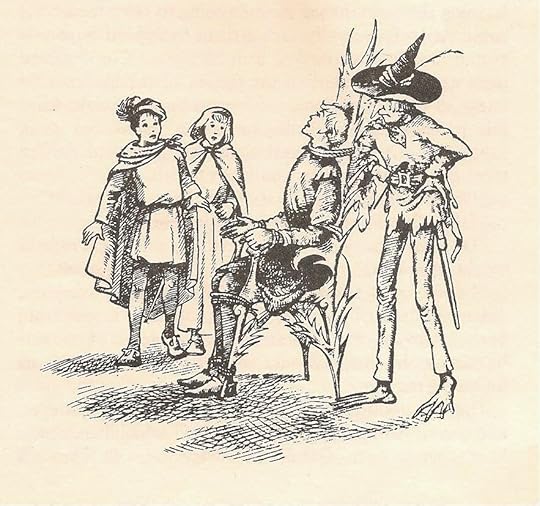

The next interlude is the journey through the city of Tashbaan, during which Shasta is separated from his friends. In an adventure pretty much borrowed wholesale from Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper, he is mistaken for his (as it will turn out) long-lost identical twin, young Prince Corin of Archenland who's come on a Narnian state visit to Tashbaan centred on a possible marriage between Susan of Narnia and Prince Rabadash, eldest son of the Tisroc. In comparison to the Calormen lords and ladies lolling on their litters carried by “gigantic slaves”, the Narnians are first seen on foot:

Their tunics were of fine, bright, hardy colours – woodland green, or gay yellow, or fresh blue. Instead of turbans they wore steel or silver caps… The swords at their sides were long and straight, not curved like the Calormen scimitars. And instead of being grave and mysterious like most Calormenes, they walked with a swing and … chatted and laughed. One was whistling. You could see they were ready to be friends with anyone who was friendly and didn’t give a fig for anyone who wasn’t. Shasta thought he had never seen anything so lovely in his life.

Reading this for the first time I was of course thrilled to back in the company of real Narnians at last, and Lewis makes them sound attractive indeed – a breath of fresh air. Now I can’t help noticing how every word is loaded so that even the Narnians’ dress choices appear ‘better’ than those of the Calormen. Do Calormen people never dress in blue, yellow or green? And why in any case should those colours be preferred to red, purple or gold? Because those are colours associated with luxury, and by further implication with moral degeneracy? It would be even sillier to say out loud that the ‘straight’ Narnian swords suggest directness and honesty while the ‘curved’ Calormen scimitars denote indirectness and treachery – but that’s what this passage manages, on a subconscious level, to imply.

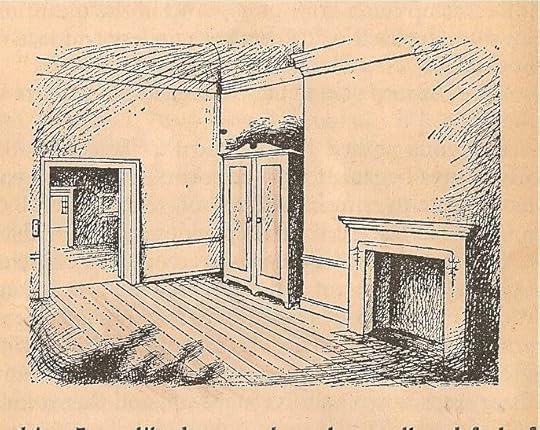

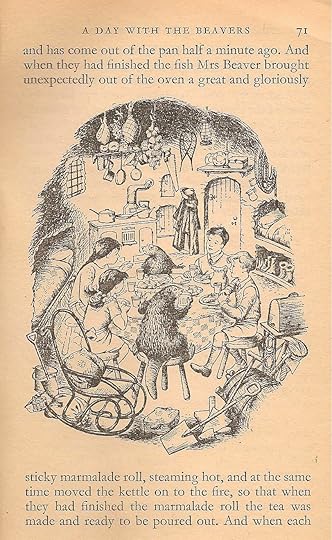

Snatched from his friends, Shasta is taken away to the Narnians’ guest suite in a great palace, where he is scolded as a truant. In the same way that young Tom Canty in The Prince and the Pauper is mistaken for King Henry VIII’s son Prince Edward and assumed to have lost his memory from ‘too much study’, Mr Tumnus (hooray!) suggests to Edmund and Susan that the ‘little prince’ must have a touch of sunstroke. ‘Look at him! He is dazed. He does not know where he is.’ Told to rest on a sofa and given iced sherbert to drink, Shasta overhears all the Narnians’ discussions. Queen Susan no longer wishes to marry Prince Rabadash who is turning out – in Edmund’s words - ‘a most proud, bloody, luxurious, cruel and self-pleasing tyrant’. In the course of their discussions Shasta learns of a secret desert route which he and his friends will take once reunited. But the Narnians intend to escape by sea, and now Shasta hopes to go with them.

He only hoped now that the real Prince Corin would not turn up until it was too late and that he would be taken away to Narnia by ship. I am afraid he did not think at all of what might happen to the real Corin when he was left behind in Tashbaan. He was a little worried about Aravis and Bree waiting for him at the Tombs. But then he said to himself, “Well how can I help it?”

This is disconcerting selfishness. If it weren’t for Corin’s sudden return (having got into a fight and been arrested by the Watch) Shasta would abandon his friends. His readiness to make excuses for himself and to think badly of Aravis may be realistic but it's not endearing. Lewis dedicated THHB to David and Douglas Gresham, the young sons of the American writer Joy Davidman whom he was to marry in 1956, two years after the book was published, and I wonder if he chose a boy protagonist for their sake? Shasta is the first main male protagonist in the Narnia books (in order of publication), but Lewis doesn’t really love him. Aravis has more flair, Bree more personality, Hwin more compassion... From the beginning Shasta is starved of depth. In his memoir Surprised By Joy Lewis recalls how uncomfortable he and his brother were when their father engaged them in emotional conversations after their mother's death. Did he think the Gresham boys would find emotion - other than fear - soppy?

You must not imagine that Shasta felt at all as you or I would feel if we had just overheard our parents talking about selling us for slaves. For one thing, his life was already little better than slavery… For another, the story about his own discover in the boat had filled him with excitement and with a sense of relief. He had often been uneasy because, try as he might, he had never been able to love the fisherman.

Here is no regret, no sense that Shasta might wish Arsheesh could have loved him. Shasta’s life is an emotional void and he doesn’t seem to know or care. Ambition stirs, but no longing:

And now, apparently, he was no relation to Arsheesh at all. That took a great weight off his mind. “Why, I might be anyone!” he thought. “I might be the son of a Tarkaan myself – or the son of the Tisroc (may he live forever) – or of a god!”

Shasta is inexperienced and naïve, and he wants to be something better. He is awkward with and rude to Aravis not just because she's a girl, but because he is jealous of her status, confidence and manners: and there is some shrewd comedy at his expense:

Aravis produced rather nice things to eat from her saddlebag. But Shasta sulked and said No thanks, and that he wasn’t hungry. And he tried to put on what he thought very grand and stiff manners, but as a fisherman’s hut is not usually a good place for learning grand manners, the result was dreadful. And he half knew it wasn’t a success and then became sulkier and more awkward than ever.

This is not unsympathetic, but it’s likely to make us smile at Shasta rather than love him. His main characteristics are anxiety and self-pity: he has no core strength like Lucy or Jill or Aravis. Perhaps his inarticulacy is touching: a revelation of the fears and inadequacies that boys so often conceal. Still, as the story progresses, Shasta and Aravis learn to judge one another more fairly, and Shasta does take responsibility for the desert march. Though it seems to come out of the blue, he proves himself finally at the moment when he jumps off Bree's back to defy the lion that is attacking Aravis – and when he runs on at the Hermit’s urging to warn King Lune of Rabadash’s approaching force. But even when he finds himself to be Prince Cor, eldest son of King Lune of Archenland, the emotional drought continues. The dam never breaks, the rain never comes, the revelation is all cogs and clockwork. Still worried about what Aravis will think of him, he continues to express himself in tongue-tied clichés like a prep-school boy:

Father’s an absolute brick. I’d be just as pleased – or very nearly – at finding he’s my father even if he wasn’t a king. Even though Education and all sorts of horrible things are going to happen to me.

Two throwaway moments in THHB show what Lewis could have done with Shasta. One is when Bree presses the question of whether Shasta can eat grass:

“Ever tried?”“Yes, I have. I can’t get it down at all. You couldn’t either if you were me.”

The other is when Shasta tries dismounting (to spare the horses) on the desert ride:

As his bare foot touched the sand he screamed with pain and got one foot back in the stirrup and the other half over Bree’s back before you could have said knife.

A child who tries to eat grass, a child whose shoeless feet scorch in the hot sand: here is poverty made pitiable and tangible.

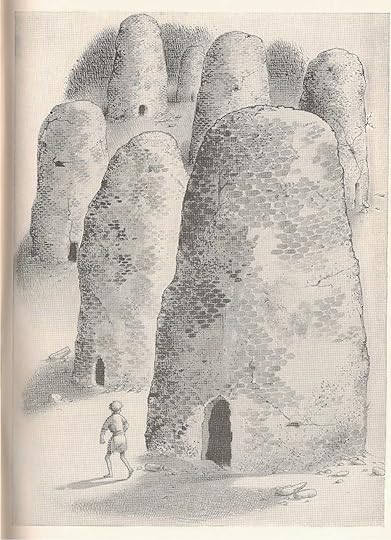

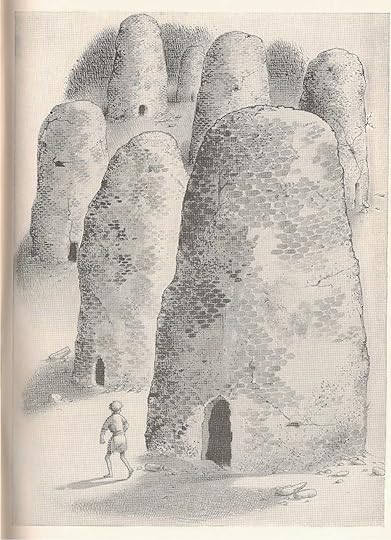

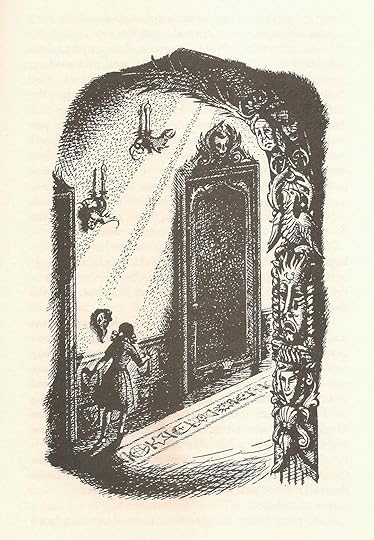

Moving on: after the 'real' Prince Corin reappears, Shasta hurries to the Tombs of the Ancient Kings, where he and his friends agreed to meet if they become separated in Tashbaan. '[A]nd now the sun had really set. Suddenly from somewhere behind him came a terrible sound. Shasta's heart gave a great jump and he had to bite his tongue to keep himself from screaming. Next moment he realised what it was: the horns of Tashbaan blowing for the closing of the gates.' In one of the most atmospheric chapters in the book Shasta spends the night alone beside the Tombs, which are like 'gigantic beehives ... black and grim', later even more scarily personified as '... horribly like huge people, draped in grey robes that covered their heads and faces'.

Aravis meanwhile has been having her own adventures: recognised by her girly friend Lasaraleen, she effects a hair-raising escape from the palace at night during which, crushed behind a sofa, she and Lasaraleen overhear Rabadash and the Tisroc plotting treacherously to attack King Lune's castle of Anvard - and witness the cringing, sycophantic behaviour of her affianced husband, Ahoshta the Vizier. With Lasaraleen's help, Aravis and the horses rejoin Shasta at the Tombs where they pool their information. Aravis carries the news of Rabadash's plans; Shasta knows the secret route across the desert. The race is on to reach Archenland ahead of Prince Rabadah, and warn King Lune.

It will turn out that Aslan has been masterminding nearly the whole plot of THHB – as he himself explains, walking unseen in the mist unseen beside Shasta when he is lost.

I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead. I was the lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the Horses the new strength of fear for the last mile so that you should reach King Lune in time. And I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore…

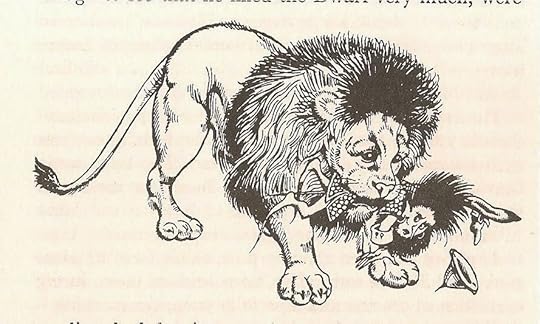

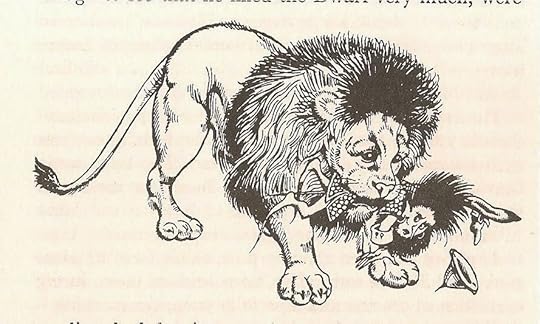

Lewis wants us to find this moving, perhaps even comforting. At ten years old I accepted it but it didn’t move me, and to me now it seems manipulative, reducing the characters to puppets as Aslan reconfigures Shasta’s account of his misfortunes to show that all the ‘bad’ things which have happened to him were in fact for the good. There is something uncomfortably controlling about Aslan’s sequential incursions into the lives of Shasta, Aravis and Bree, even though Bree certainly deserves to be taken down a peg or two. As a child I found the scene irresistibly comic in which Bree confidently asserts that Aslan is not a real lion – while Aslan creeps up behind him.

“No doubt,” continues Bree, “when they speak of him as a Lion they only mean he’s as strong as a lion or (to our enemies of course) as fierce as a lion. …it would be quite absurd to suppose he is a real lion. … Why!” (and here Bree began to laugh) “If he was a lion he would have four paws, and a tail, and Whiskers!... Aie, ooh, hoo-hoo! Help!

For just as he said the word Whiskers one of Aslan’s had actually tickled his ear.

It is still funny. Just not as funny as it was.

The religious message in THHB seems to me painting-by-numbers. A series of events is worked out to illustrate a set of propositions: God ordains all things; God knows and judges all things; God will reward the good and punish the sinner; God is with us always. It reminds me of those ‘footprints in the sand’ posters which can be bought from Christian bookshops with a little parable in which God reassures us that ‘when you thought you were walking alone, that is when I was carrying you.’ Such parables undoubtedly do comfort some people, and heaven knows we all need comfort. However, sincerity is required to make these things work, and in The Horse and His Boy I’m not convinced Lewis is sincere. It’s all a little too clever. There is no sense that anything springs from a deep emotional source and this is evident at the end of Chapter XI when Aslan at last reveals himself to Shasta. Lewis strains unsuccessfully for affect: at least it doesn't work for me.

It was from the Lion that the light came. No-one ever saw anything more terrible or beautiful. … After one glance at the Lion’s face [Shasta] slipped out of the saddle and fell at its feet. He couldn’t say anything but then he didn’t want to say anything, and he knew he needn’t say anything.

The High King above all kings stooped towards him. Its mane, and some strange and solemn perfume that hung about its mane, was all around him. It touched his forehead with its tongue.

This is a stern, remote, High Church Aslan far removed from the flesh and blood Lion who played so joyfully with Lucy and Susan in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe – as far removed perhaps as the Jesus of the Gospels seems from the mosaic Christs in Byzantine basilicas. The Aslan who sacrificed himself for Edmund, whose blood and pain restored Caspian to life, youth and strength, has become the Aslan who tears bloody stripes in Aravis's back and even scratches Shasta in retaliation for having once thrown stones at a cat. It's a harsh and retributive transformation.

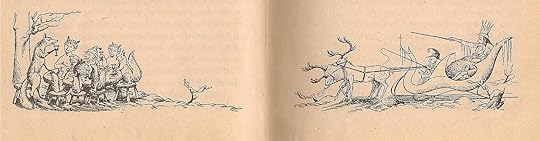

Still, as a child, I felt the adventure had been wrapped up very satisfactorily. The story ends in slapdash humour. Prince Rabadash makes a fool of himself (“The bolt of Tash falls from above!” – “Does it ever get caught on a hook half-way?”) and is transformed by Aslan (punitive to the last) into a donkey so he can do no more harm. Shasta is reinstated as Prince of Archenland. Bree casts off his anxiety and has a good roll. Cor and Aravis’s eventual marriage, in order to go on quarrelling ‘more conveniently’, seemed to me a reasonable and un-sloppy basis for a relationship; they were clearly good friends. I closed the book and reached for the next.

What has surprised me most on this re-reading isn't so much that I found myself addressing questions of racism; I knew I would have to do that. What really surprised me is how didactic, how prescriptive I've found a book which I've remembered as perhaps the least 'religious' of the Narnia stories. I suspect that it turned out this this way because Lewis never really put his heart into the story at all... except for the character of Bree, horsiest of horses.

* Flying carpets though, as Ruth B. Bottigheimer has recently pointed out in an interesting essay in Gramarye, Issue 13, are not in fact native to the Arabian Nights tales.

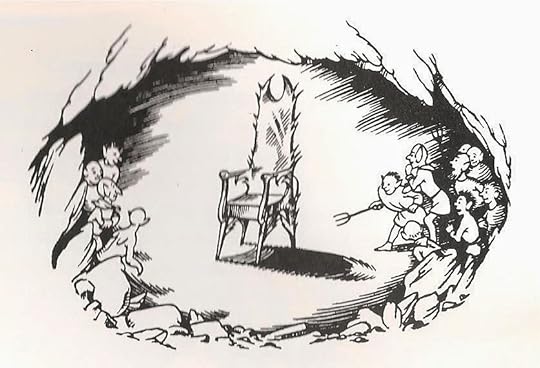

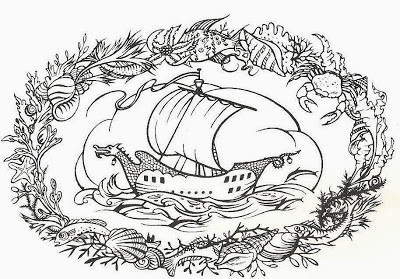

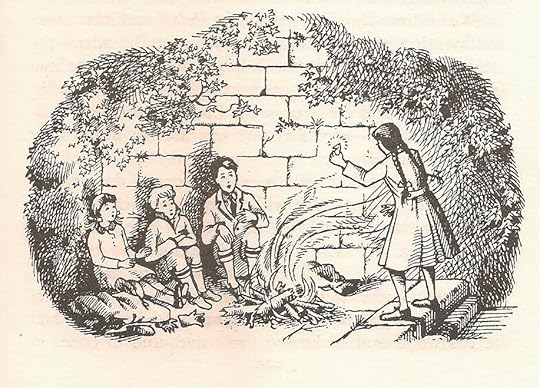

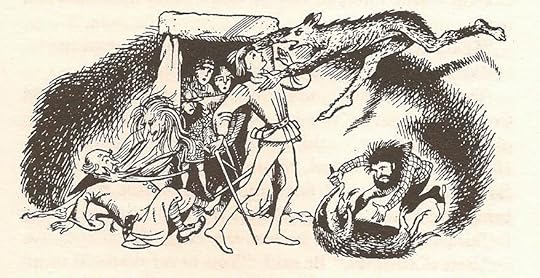

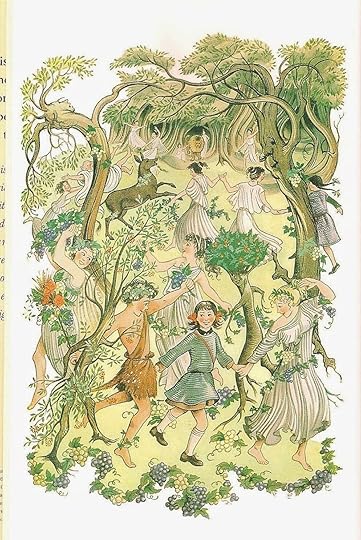

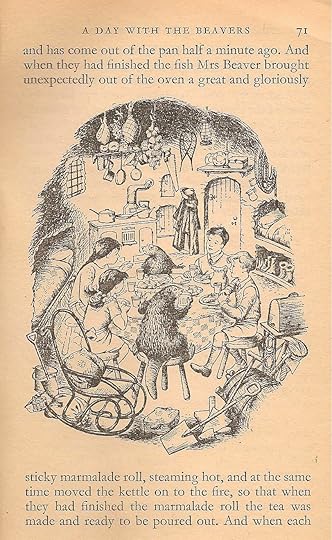

Picture credits:

All artwork from 'The Horse and His Boy', by the magnificent Pauline Baynes. Visit her website here: http://www.paulinebaynes.com/

This, the fifth Narnia book in order of publication, is the one I’ve thought about least since childhood. And it was never one of my particular favourites, which seems odd considering that next to Narnia, ponies were my passion. A book which combined Narnia and horses ought to have been a big hit.

This, the fifth Narnia book in order of publication, is the one I’ve thought about least since childhood. And it was never one of my particular favourites, which seems odd considering that next to Narnia, ponies were my passion. A book which combined Narnia and horses ought to have been a big hit.I enjoyed the book, but I didn’t love it the way I loved The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair. This may be because it’s the least complex, least layered of the Seven Chronicles. It’s a simple adventure story offering straightforward pleasures: appealing characters, obnoxious villains, touches of humour, an arduous journey and a nick-of-time rescue. What it doesn't offer – alone among the Narnia books – is anything much in the way of strong emotion, wonder or awe. Certainly nothing to match the moment when the Stone Table cracks in two, or when Reepicheep’s coracle vanishes over the crest of the wave at the end of the world, or the brilliant birds fluttering in the trees at the top of Aslan’s holy mountain, or the poignant death of old King Caspian. To use Lewis’s own words, I can find no ‘stab of joy’ in The Horse and His Boy. On this re-reading I was entertained and amused by the book, but seldom moved.

Told throughout from within – from the point of view of characters who were born in Narnia rather than in our world – The Horse and His Boy is set during the ‘golden age’ when the four thrones of Cair Paravel are filled by the four children of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. The hero of the book, the boy Shasta, has grown up to the age of perhaps twelve believing himself the son of Arsheesh, a poor fisherman in the southern land of Calormen, a country which will remind most readers of the Persia of the Arabian Nights. And we run into an immediate difficulty. The dark-skinned Calormens are depicted in a way that strikes me now as at best naively Orientalist, at worst upsettingly racist.

In an essay called ‘The Revolution in Children’s Literature’ (The Thorny Paradise, Writers on Writing for Children, ed. Edward Blishen, Kestrel 1975) the children's writer Geoffrey Trease recalled the sexism and racism prevalent in children’s books during the first half of the 20thcentury and rather bravely illustrated it with a toe-curlingly inappropriate extract from a story written by himself as a schoolboy in 1923:

‘The white dog!’ hissed the Arab leader, and his scimitar grated against my cutlass… I saw the dark triumphant face of my antagonist, the curved beam of reflected light raised to strike, and like a flash I ducked, and striking upwards with my left hand, administered a thoroughly British uppercut. And, because an Oriental can never understand such a blow, he reeled back, a look of almost comical surprise on his face. Ere he could recover, I lunged out with my cutlass and stretched him dead upon the ground.

While you’re recovering: I have a theory that classic children's books have a half-life of about fifty years of being read by actual children (after a century, most are relegated at best to academic study). They last this long mainly because adults give or read to children the books they themselves remember, and because books are durable physical objects that may sit for decades on dusty shelves to be pulled out by voracious young readers. This is how I gobbled down the jingoistic and now practically unreadable works of GA Henty, written in the last third of the nineteenth century. What modern ten year-old could tolerate ‘Under Drake's Flag, A Tale of the Spanish Main' (1883) or 'By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War' (1884)? They were eighty years old by the time I was reading them in the 1960s and surely I must have been in the last generation of children who could possibly have enjoyed them. But the sixty year-old Narnia stories are very much with us, kept alive like the Velveteen Rabbit by the love of real children. Henty's prejudices may no longer matter, but those of CS Lewis are still of concern. And I can't help feeling he should have known better. As an adult, Geoffrey Trease set out to combat the prejudice he’d parroted as a boy. His historical novels for children, like ‘The Red Towers of Granada’ (1966), are deliberately respectful of ‘other’ cultures like those of Judaism or Islamic Spain. In spite of his efforts, the range of literature available to me growing up in the sixties was still crammed with dodgy foreigners, cunning, or comic, or cowardly, or cruel. I noticed, without realising it was unfair. So long as an author spins a good story, children are accepting readers.

Lewis first introduces the Calormen in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

Two merchants of Calormen … approached. The Calormen have dark faces and long beards. They wear flowing robes and orange-coloured turbans, and they are a wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient people.

‘Wise, wealthy, courteous and ancient’ are all very well until we reach that word ‘cruel’: in its company all other virtues are contaminated. Lewis continues:

They bowed most politely to Caspian and paid him long compliments, all about the fountains of prosperity irrigating the gardens of prudence and virtue – and things like that – but of course what they wanted was the money they had paid.

The Calormen’s flowery language is critiqued in THHB as the language of insincerity, especially compared to the white-skinned Narnians’ free, frank speech. (Note that interesting word ‘frank’, with its derivation from the founders of western culture.) From the outset Lewis leaves no doubt that Calormen culture and society is morally inferior. One has only to look at the relationship between Shasta and his foster father Arsheesh to see how Lewis puts his hand in the scales. The fairytale motif of ‘noble baby set adrift’ is found world-wide, from Moses, to Perseus, to Perdita in The Winter’s Tale, and in most of these stories the foster parent, whether humble fisherman or noble princess, rescues and raises the child with unselfish tenderness. Lewis inverts this tradition. Arsheesh self-servingly explains to the Tarkaan who wishes to buy Shasta:

‘“Doubtless,” said I, “these unfortunates have escaped from the wreck of a great ship, but by the admirable designs of the gods, the elder has starved himself to keep the child alive, and has perished in sight of land.” Accordingly, remembering how the gods never fail to reward those who befriend the destitute, and being moved by compassion (for your servant is a man of tender heart) – ’

‘Leave out all these idle words in your own praise,’ interrupted the Tarkaan. ‘It is enough to know that you took the child – and have had ten times the worth of his daily bread out of him in labour, as anyone can see…’

There’s no love or tenderness between Arsheesh and Shasta: the latter is simply relieved to learn that he’s not the fisherman’s own flesh and blood. He even dreams of possible advancement (‘the lordly stranger on the great horse might be kinder to him than Arsheesh’). Lewis soon dispels this dream, and leaves an adult reader in some discomfort as to why this Tarkaan has suddenly taken a fancy to buy Shasta.

‘This boy is manifestly no son of yours. For your cheek is as dark as mine but the boy is fair and white like the accursed but beautiful barbarians who inhabit the remote north.’

Admiration for despised beauty is never a good sign. What is Bree the Talking Horse implying, when he warns Shasta in the strongest terms that the Tarkaan is bad – ‘Better be lying dead tonight than go to be a human slave in his house tomorrow’? Aged ten I simply assumed ‘hard work and beatings’. Now I wonder whether this might truly be a 'fate worse than death'.

Orientalism is a term employed by Edward Said to critically examine patronising Western perceptions of the East: it marks a subset of racism which views Eastern cultures as despotic, fanatic, mysterious, 'inscrutable' and inferior. Lewis’s characterisation of the dark-skinned Calormen, quoted above, as ‘wise, wealthy, courteous, cruel and ancient’ could be a textbook example. If Trease overcame his early conditioning, why couldn’t Lewis? Yes, there is Aravis, yes there is the gentle and courteous knight Emeth in The Last Battle. They remain exceptions.

But there is more going on. Narnia is a paradise of happy magical creatures and talking animals. By contrast, Calormen is a grown-up country of farms and roads, a religion and a class structure, a bureaucracy, a literature, slaves and soldiers and cities. Despite its supposed Arabian Nights exoticism, from a child’s perspective Calormen is a dull place.

How come? Where are all those flying carpets*, magical rings, terrifying jinni, sorcerers and enchantresses with which Scheherezade filled the Thousand and One Nights? Lewis ditched them all. He borrowed the trappings of the Arabian Nights but left out all the magic.

Shasta was not at all interested in anything that lay south of his home because he had once or twice been to the village with Arsheesh and he knew that there was nothing very interesting there. In the village he only met other men who were just like his father – men with long, dirty robes, and wooden shoes turned up at the toe, and turbans on their heads, and beards, talking to one another very slowly about things that sounded dull.

It’s not as though the Narnia books haven’t already carried us to foreign lands. The wilds of Ettinsmoor, the depths of Bism, the numinous islands of the Eastern Sea – these belong, these fit within the Narnian fairy world. But Calormen isn’t a fairytale land. It exists to oppose Narnia’s every quality. If Lewis had wanted, he could have incorporated peris and griffins, flying carpets and sphinxes into his story, but he didn’t want. Not even the ghouls of the Tombs are ‘real’.

In a fantasy series which happily blends classical and Norse mythologies, medieval legends and talking animals, why did Lewis instinctively (I doubt he thought about it) strip all the magic from the Arabian Nights? Where else in the Narnian world does this failure of enchantment occur? Answer: on the unmagical Lone Islands, in the least interesting episode of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, where the Calormen trade for slaves – and in King Miraz’s Narnia, where the only town, Beruna, is demolished by Aslan and the personified powers of nature, a destruction significantly presented as a restoration. Narnia at its most Narnian is a place of joyful and magical disorder, a place in which there is no need for rules because no one wants to do anything bad. It owns no villages like Shasta’s, no cities, no roads. Cair Paravel is a stand-alone fairytale castle. King Lune’s castle of Anvard in Archenland is similarly isolated.

Unlike the threat posed by the magical White Witch and Green Lady, the threat to Narnia from Calormen (and the Telmarine rule of Miraz) is a divorce from magic. The Calormen are enemies of the imagination, enemies of fairyland itself. Their rule would destroy Narnia's magic, substituting an order of economics, progress, trade, politics, scepticism: necessary but unromantic things which Lewis didn’t like and didn’t want in his fairy paradise. The be-turbaned, Arabian Nights-style Calormen represent these values however, only because Lewis chose they should. Historically it was the West which imposed its industrial and political values upon the rest of the world.

In some conservative Christian circles CS Lewis is the logic-chopping wielder of the Sword of Truth. But he could and did allow prejudice to blind him. No doubt at the back of his mind was the medieval clash between Islam and Europe: the Matter of France, the Song of Roland, the Battle of Lepanto. Compared with the magic of the pagan Greek myths (so important a component in western education as, paradoxically, to have become a part of Christian European identity) I suspect Lewis felt deep in his bones that the magic of the Arabian Nights was foreign,inimical, incompatible with Aslan’s. So he left it out, but his depiction of the Calormen people creates all sorts of problems. They are undoubtedly human, so where have they come from? Are they, like Peter and Edmund, Susan and Lucy, ‘sons of Adam and daughters of Eve’ - originally from our world? When Aslan sang Narnia into existence in The Magician’s Nephew, did he create the Calormen too? He made their land: Polly and Digory glimpse the desert sands from Fledge's back. And what about their gods, Zardeenah, Azaroth and Tash? There'll be more to say about these questions when we come to The Last Battle.

For now, though, on with the story!

One of the things I truly loved about this book was the relationship between Shasta and Bree, the Narnian Talking Horse who, like Shasta, was kidnapped as a little foal.

“My mother warned me not to range the southern slopes, in Archenland and beyond, but I wouldn’t heed her. And by the Lion’s Mane I have paid for my folly. All these years I have been a slave to humans, hiding my true nature and pretending to be dumb and witless like their horses.”

A pony-mad little girl, I found the story of Shasta being taught to ride by his horse enchanting (“No one can teach riding so well as a horse”). Bree, or to give him his full name, Breehy-hinny-brinny-hoohy-hah – is a superb character. I loved and still love his good-humoured disdain for Shasta and for humans in general (“What absurd legs humans have!”) and his bracing lack of sympathy for Shasta’s aches and pains (“It can’t be the falls. You didn’t have more than a dozen or so.”). An experienced war-horse, Bree takes initial charge of the escape, but as the adventure continues it is the inexperienced Shasta who begins to make the difference, while Bree allows vanity and insecurity (would a true Narnian Talking Horse enjoy a good roll?) to undermine him.

Bree sees that escaping together will improve both their chances: he won’t be chased as a stray, and on his back Shasta can ‘outdistance any other horse in this country.’ With a final bit of riding advice from the Horse to his Boy, off they go:

“Grip with your knees and keep your eyes straight ahead between my ears. Don’t look at the ground. If you think you’re going to fall just grip harder and sit up straighter. Ready? Now: for Narnia and the North.”

One night after ‘weeks and weeks’ of journeying, Bree and Shasta hear another horse and rider accompanying them northwards between the forest and the sea.

“Ssh!” said Bree, craning his neck around and twitching his ears... “…That’s not a farmer’s riding. Not a farmer’s horse either. Can’t you tell by the sound? …I tell you what it is, Shasta. There’s a Tarkaan under the edge of that wood. Not on his war horse – it’s too light for that. On a fine blood mare, I should say.”

'Craning his neck around and twitching his ears': Lewis never forgets that Bree is a horse.

The strange ‘horseman’ seems as eager to avoid them as they are to avoid him, but lions attack. The two horses are driven together in a mad gallop across the sands, and the young rider – described as a ‘small, slender person, mail-clad … and riding magnificently’ is revealed as a girl, Aravis, with ‘her’ Talking Horse, Hwin. It’s a dramatic entrance, and Aravis takes no prisoners from the start.

“Broo-hoo-hah!” [Bree] snorted. “Steady there! I heard you, I did. There’s no good pretending, Ma’am. …You’re a Talking Horse, a Narnian horse, just like me.” “What’s it got to do with you if she is?” said the strange rider fiercely, laying hand on sword-hilt. But the voice in which the words were spoken had already told Shasta something. “Why, it’s only a girl!” he exclaimed. “And what business is it of yours if I am onlya girl?” snapped the stranger. “You’re only a boy: a rude, common little boy – a slave probably, who’s stolen his master’s horse.”

When the book was written fifty years ago, this ‘only a girl’ thing was everywhere, a universal pollutant we all breathed. In Little Women, in What Katy Did – in Enid Blyton’s books about the Famous Five, even in Geoffrey Trease – my friends and I encountered heroines who wished they were boys, and we didn’t always understand that this wasn’t because boys were naturally superior, but because society privileged them with better choices and opportunities. So it was great to meet competent, confident Aravis who rode a horse the way I wished I could, and wore a sword too. And when Shasta comes out with this classic put-down, ‘only a girl’, Aravis annihilates him. Later in the book, when Hwin quietly suggests it would be wise for them to keep going, Bree retorts crushingly: 'I think, Ma'am... that I know a little more about campaigns and forced marches and what a horse can stand than you do'. (Stallionsplaining!) And Hwin shuts up because she is 'a very nervous and gentle person who was easily put down.' But Hwin is right and Bree is wrong, and his decision is a bad one. In my mind, Lewis is certainly an equal-opportunities author.