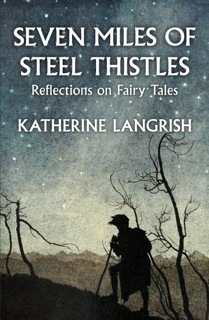

Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 20

July 22, 2016

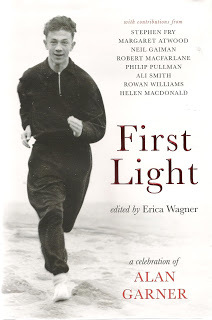

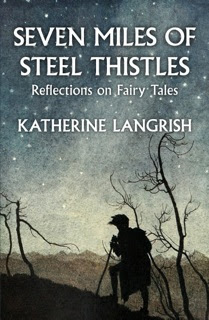

Four lovely reviews for Steel Thistles!

A quick post to highlight four lovely reviews of 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles' (the book) which as many of you will know, is a collection of some of my essays on folk-lore and fairy tales. Do please excuse me as I jump up and down!

The most recent comes from Kevin Crossley-Holland, poet, author, and translator of Anglo-Saxon texts such as 'Beowulf' and the 'Exeter Riddle Book'. He writes:

Katherine Langrish is a wonderful companion for an excursion into the otherworld of traditional tales. Highly readable, sharply perceptive about individual tales as well as engaging with wider motifs, this book is always down-to-earth, no matter how high flown the subject matter. We know we're in safe hands when we're invited to consider why folk-tale fools and saints can be rather frightening, or to take account of who is telling a story and why, to reflect on how some reports of ghostly happenings (as opposed to structured stories) are almost impossible to discount, and to recognise the role of princesses in fairy tales ('They tell us to be active, to use our wits, to be undaunted, to see what we want and to go for it.') The book is so generously furnished with apt quotations as to seem at times almost like an anthology, and it will appeal to absolutely everyone fascinated by the staying power of folk tales, fairy tales and ballads. 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles' is a fine book with a long life ahead of it.

Writer, editor and artist Terri Windling, reviewing the book on her blog Myth and Moor, wrote:

One of the very best books I've read this year isSeven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales by Katherine Langrish, the author of West of the Moon and other excellent works of myth-based fantasy for children.

Now while I might seem biased because Katherine is a family friend (her daughter and ours have been best friends for many years), in truth I am sharply opinionated when it comes to books about folklore and fairy tales; I was mentored in the field by Jane Yolen, after all, which sets the bar pretty damn high. Thus it is no small praise to say that Seven Miles of Steel Thistles is an essential book for practioners of mythic arts: insightful, reliable, packed with information...and thoroughly enchanting.

The whole review can be found here.

A third is from award-winning YA and children's author Linda Newbery. Here's part of what she has to say:

Katherine Langrish draws on her life-long enjoyment and appreciation of traditional tales, and her book combines wide reading and scholarship with personal insights and interpretations... Her book ranges widely, from Canadian Mi’kmaq stories to Japanese kitsune, Shakespeare’s fools and Alan Garner’s owl plates, with, of course, the Celtic and Norse mythology which is woven through Langrish’s own fiction. She is a most engaging companion – informed, curious and perceptive - and I highly recommend her book to students of the genre as well as to anyone who enjoys good stories and good writing.

You can read the whole review here: http://www.lindanewbery.co.uk/2016/07/15/seven-miles-of-steel-thistles-by-katherine-langrish/

Last but certainly not least, here's praise from the critic Nicholas Lezard in his weekly column for the Guardian:

What [Langrish] has done so brilliantly, either making general points or addressing specific stories or themes, is tell us stories about the stories: where they might have come from, what they might mean, or whether they are meant to mean anything. (Of faeryland, that “other place” which is neither the world, heaven, purgatory or hell, from where those we thought dead might, very rarely, be rescued, she says: “This is the fantasy of grief,” and I have never heard a better explanation.) It is all spun out so seemingly artlessly, or naturally, that you feel as if you are sitting cross-legged, gripped, like a child hearing one of these stories for the first time.

Read the whole review here: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/may/04/seven-miles-of-steel-thistles-review-katherine-langrish-fairytales-written-down-as-told

You couldn't wish for lovelier comments or more perceptive readers, and I'm very happy and thrilled. Seven Miles of Steel Thistles was published by the Greystones Press at the end of April, and is available from Amazon in paperback (here) and as an e-book (here). It's also available in paperback from Hive.co.uk (here). (As indeed are all my other books.) Finally, those living outside the UK can order copies from the Book Depository, which offers free delivery worldwide, here!

Right, that's the commercial over. Thankyou for your patience and thankyou even more to all the lovely people who've bought copies already. Where would I be without readers?

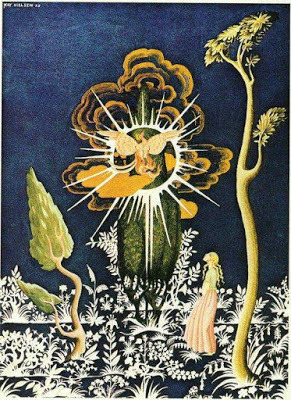

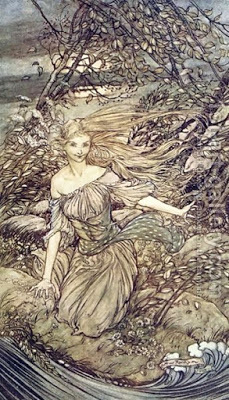

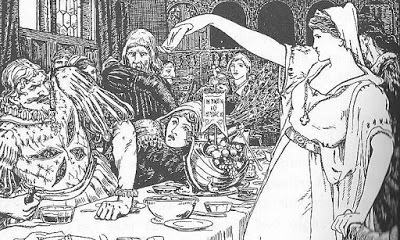

Picture credits

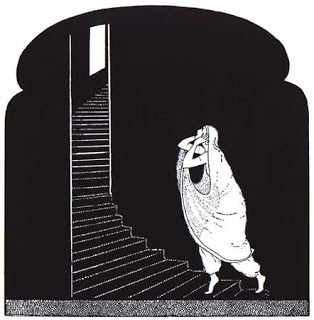

Illustrations of some of the fairy tales mentioned in the book:

The Juniper Tree by Kay Nielsen

Undine by Arthur Rackham

Mr Fox by John D Batten

Published on July 22, 2016 04:23

July 14, 2016

Secret Rooms, Bloody Chambers

When I was twelve, my brother and I had a den in an unused outbuilding belonging to the house we lived in. We trod a narrow winding path through a deep bed of green nettles to get to the flaking, rickety door; we whitewashed the walls and found some old broken stools and chairs to furnish it. It was our private place. We made a cardboard sign to hang on the door and ward off intruders: it read, in drippy red paint: ‘Beware! 10,000 Volts!’

A few years later when we were in our early teens, our parents bought an enormous old house in the Yorkshire Dales which had been empty for three years since the death of the last owner, an elderly spinster whose family had built the house in the early 18th century. There was no electricity, so for six months we went to bed with candles and oil lamps. One room, with a hole in the floor, was too dangerous to enter until the joists had been mended: we would peer in from the doorway at a clutter of mysterious objects: a half-rotted Jacobean table, a Victorian birdcage, knife-sharpening machines, stone floor-polishers. Another room had a pointed, arched doorway. My parents had the decorators in, and one of them peeled away damp wallpaper to discover a small, hidden cupboard. In great excitement he called us all to assemble before he opened it. But it was empty…

In ‘The Uses of Enchantment’, Bruno Bettelheim discusses secret or forbidden rooms in fairytales very much in Freudian terms: ‘ ‘Bluebeard’ is a story about the dangerous propensities of sex, about its strange secrets and close connection with violent and destructive emotions.’

The blood upon the key which betrays to Bluebeard that his wife has entered the forbidden chamber leaves little doubt that Bettelheim is right in this instance. Keys, locks, blood: you can’t get much more Freudian than that. But, in a related fairy tale, the Grimms’ ‘Fitcher’s Bird’, it’s an egg which the murderous magician bids his brides take with them as they explore his house. ‘Preserve the egg carefully for me,’ he says, ‘and carry it continually about with you, for a great misfortune would arise from the loss of it.’ The first two girls manage to drop the egg into a basin of blood which stands in the secret chamber: scrub as they will, the bloodstains won’t wash off. Now an egg is of course a female symbol, and this tale seems to me a case of infidelity worrying the magician, rather than defloration worrying the heroine – who brightly ignores the command and puts the egg carefully aside before unlocking the forbidden door. In fact, the obvious impracticality of having to carry an egg ‘continually about’ suggests to me a sly criticism of society’s unrealistic expectations of women.

There’s a well-known old riddle about eggs:

A box without hinges, key or lidYet golden treasure within is hid.

The egg which the heroine keeps safe is a secret chamber in itself, but the treasure hidden within is not necessarily her virginity. We are free to interpret it in other ways – as her self-determination, even her very soul: folk and fairy tales world-wide tell of an external soul contained in an egg. In the Russian fairy tale ‘Koschei the Deathless’, the monstrous Koschei is killed when Prince Ivan bursts the egg in which his soul (or life, or death) is hidden; and in ‘The Young King of Easaidh Ruadh’ (collected by J.F. Campbell on Islay in 1859) the young king’s wife manages to get the giant who has imprisoned her to tell her where his soul is. Actually this story is so lovely, here’s a long piece of it –

‘It is not there that my soul is,’ said he. ‘There is a great flagstone under the threshold. There is a wether under the flag. There is a duck in the wether’s belly, and an egg in the belly of the duck, and it is in the egg that my soul is.’ When the giant went away in the morrow’s day, they raised the flagstone and out went the wether. ‘If I had the slim dog of the greenwood, he would not be long bringing the wether to me.’ The slim dog of the greenwood came with the wether in his mouth. When they opened the wether, out was the duck on the wing with the other ducks. ‘If I had the Hoary Hawk of the grey rock, she would not be long bringing the duck to me.’ The Hoary Hawk of the grey rock came with the duck in her mouth; when they split the duck to take the egg from her belly, out went the egg into the depth of the ocean. ‘If I had the brown otter of the river, he would not be long bringing the egg to me.’ The brown otter came and the egg in her mouth, and the queen caught the egg, and she crushed it between her two hands. The giant was coming in the lateness [of the evening] and when she crushed the egg, he fell down dead, and he has never yet moved out of that. They took with them a great deal of his gold and silver. They passed a cheery night with the brown otter of the river, a night with the hoary falcon of the grey rock, and a night with the slim dog of the greenwood. They came home…

Returning to ‘Fitcher’s Bird’, as soon as the heroine shows the magician the unblemished egg, ‘he now had no longer any power over her, and was forced to do whatsoever she desired.’ The girl goes on to revive and rescue her sisters and orchestrate the magician’s death. In a way, then, there are two secret rooms in this fairy tale: the Bloody Chamber which represents death and the Unbloody Chamber of the egg, which represents life and power and potential. Though other fairy tale rooms, such as the Sleeping Beauty’s chamber or Rapunzel’s tower, are often seen as symbolizing a closed virginal space in which nothing at all happens until it is penetrated by male activity, we should perhaps be wary. It is dangerous to take a Freudian interpretation as an explanation. Fairy tales are usually much richer than any particular common denominator.

How many books did you read as a child, where the discovery of a concealed room was one of the most exciting parts of the story? Enid Blyton had them by the dozen. I well remember one (in ‘The Rockingdown Mystery’) where the hero, blue-eyed Barney, spends several nights in the deserted, but poignantly furnished, nursery of an eerie abandoned house - full of old dolls and damp, moth-eaten blankets, with strange noises echoing up through the floor. You know he’s not going to stay there, he’s going to go down exploring through the dark abandoned house, he’s going to find …what?

Hidden rooms in children’s fiction are transitional places, they have meaning, they hold some clue that leads elsewhere. In Jane Langton’s 1962 classic ‘The Diamond in the Window’, Eleanor and Edward discover the ‘hidden’ room at the top of the tower – with, significantly, a keyhole-shaped stained-glass window – from which, years ago, two children with exactly the same names disappeared. This keyhole has no sexual implication. It stands for the unlocking of mystery.

[Eleanor] was blinded at first by the dimness. Then the many colours of the great keyhole window blossomed… and gradually illumined the objects in the room… a huge mirror that was sunk into the well of an enormous dresser across the room from the window. There was a table, and what was that on the table? …It was a castle, a castle made of blocks. And there were chairs and toys, and a little wagon. And what was that on either side of the window? Eleanor’s heart bounded into her throat.It was two narrow beds, and the covers were turned neatly down.

‘Two narrow beds’ – there are suggestions here of death, absence, the mysteries of time. Just as in the book by Enid Blyton, here are traces of long-ago children who have vanished. This is a recurrent theme in children’s books: for it’s a sad and certain, yet also glorious and fascinating truth that all children do disappear – into adulthood, and ultimately into death… which is presumably the meaning of that very unsettling short story by Walter de la Mare, ‘The Riddle’ – where, one after another, a whole family of children climb silently into a carved chest in the attic and disappear for ever.

Then there are bedrooms. Bedrooms, in children’s fiction, are places of magical refuge, yet full of possibility – as different as possible from the Bloody Chamber but perhaps with some similarity to the magical egg from which the young chick hatches and sets out to explore the world. A bedroom of one’s own, for a child, is a place of self-determination in which she can be and do and imagine whatever she wants. Rooms in children’s fiction, therefore, often reflect the desirable qualities of a perfect personal space.

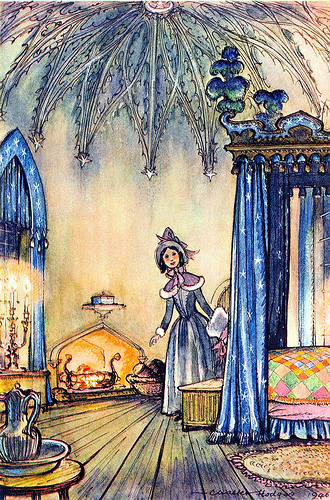

Elizabeth Goudge was good at this. Maria, heroine of ‘The Little White Horse’, coming to the magic and mystery of Moonacre Manor, is provided with a bedroom in a tower with a door too small for an adult to get through. The room has three windows, one with a window seat, a ‘silvery oak floor’, and a four-poster bed ‘hung with pale blue silk curtains embroidered with silver stars’. And ‘the fireplace was the tiniest she had ever seen,’ but big enough for ‘the fire of pine cones and applewood that burned in it… It was the room Maria would have designed for herself if she had had the knowledge and the skill.’ From such a base Maria can with confidence launch her campaign against the men of the sinister Black Castle in the pine wood.

In ‘Linnets and Valerians’, perhaps Goudge’s masterpiece, the quieter heroine Nan is given a parlour of her own by her austere Uncle Ambrose. It opens off a dark passage, but then:

The room inside was a small panelled parlour. There was a bright wood fire burning in the basket grate, and on the mantelpiece above were a china shepherd and shepherdess and two china sheep. Over the mantelpiece was a round mirror in a gilt frame… Nan sat down in the little armchair and folded her hands in her lap… It was quiet in here, the noises of the house shut away, the sound of the wind and rain seeming only to intensify the indoor silence. The light of the flames was reflected in the panelling, and the burning logs smelt sweet. And yet, in the heart of this paradise a snake lurks: the discovery, in a cupboard, of an old notebook written by the witch Emma Cobley. ‘Nan sat down in the armchair with shaking knees, but nevertheless she opened the book and began to read.’

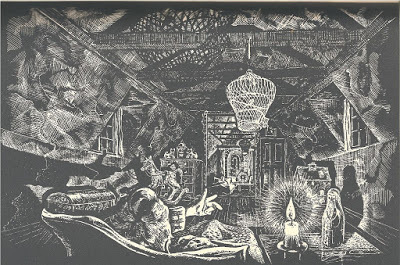

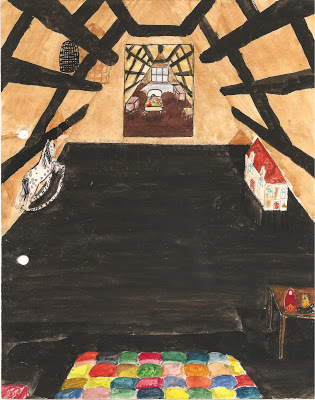

In each case, the rooms – though so utterly desirable – contain clues and hints of the past, of the passage of other people’s lives (often relations), and of mysteries which must be investigated. But the rooms give them the assurance to cope. Tolly’s delightful room in Lucy Boston’s ‘The Children of Green Knowe’ is filled with the toys, memories and ghostly presences of the children who lived there in the past and who become his companions. Though haunted, the room is magical and reassuring rather than scary, and Peter Boston's wonderful black and white illustration shows it as a tangle of enchanted shadows.

I adored the book so much as a child, I painted my own version of the room, complete with rocking horse, dolls' house, Russian doll, birdcage and mirror.

I adored the book so much as a child, I painted my own version of the room, complete with rocking horse, dolls' house, Russian doll, birdcage and mirror.

When Garth Nix’s heroine Sabriel comes for the first time to the house of the Abhorsen, escaping terrifying dangers, it is a place of refuge: 'The gate swung open, pitching her on to a paved courtyard, the bricks ancient, their redness the colour of dusty apples. The path wound up to…a cheerful sky-blue door, bright against whitewashed stone.’ And she wakes later, ‘to soft candlelight, the warmth of a feather bed…A fire burned briskly in a red-brick fireplace, and wood-panelled walls gleamed with the dark mystery of well-polished mahogany. A blue-papered ceiling with silver stars dusted across it faced her newly opened eyes.' Though Sabriel cannot stay here, the house strengthens her, providing not merely physical comfort but a very necessary sense of of identity and self-knowledge.

Betsy Byars’ ‘The Cartoonist’ takes this further. The only place in Alfie’s crowded house where he can be himself is in his attic. Here he expresses himself by drawing the cartoons that are his life-blood. As long as he has his attic, he can cope with the demands of his noisy, feckless family:

Nobody ever went up there but Alfie. Once his sister, Alma, had started up the ladder, but he had said, “No, I don’t want anybody up there…I want it to be mine.”

When the family decide over his head that his older brother should have the attic, Alfie’s entire personal existence – and his imaginative life – are threatened. He barricades himself in. And in Michael Ende’s ‘The Never-Ending Story’, Bastian hides himself in the school attic ‘crammed with junk of all kinds’:

Not a sound to be heard but the muffled drumming of the rain on the enormous tin roof. Great beams blackened with age rose at regular intervals… and lost themselves in darkness. Here and there spider webs as big as hammocks swayed gently in the air currents.

Sinister it may seem, but this is a safe place, a place where Bastian can open the Never-Ending Story and escape into fiction.

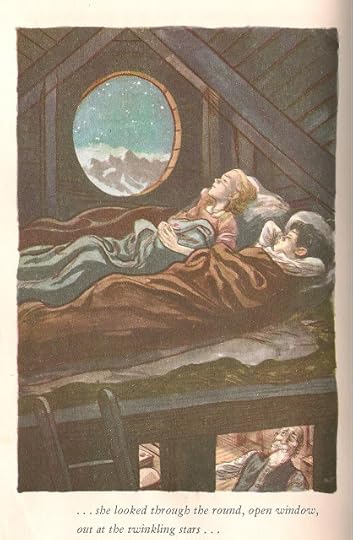

I remember wishing I, like Heidi, could have a bedroom up a ladder in a hay-loft, where Heidi sleeps ‘as soundly and well as if she had been in the loveliest bed of some royal princess’. And to this bedroom she returns later in the book with her rich, lame friend Klara:

They all stood round Heidi’s beautifully made hay bed…drawing deep breaths of the spicy fragrance of the new hay. Klara was perfectly charmed with Heidi’s sleeping place. ‘Oh Heidi! From your bed you can look straight out into the sky, and you can hear the fir trees roar outside. Oh I have never seen such a jolly, pleasant sleeping room before.’

This mountain home will give strength to Klara and heal her. And isn’t part of the charm in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s ‘A Little Princess’ the way in which Sara’s attic room is transformed, first by the power of her own imagination and then by a reality which she calls ‘the magic’, from a cold, inimical space into a place which comforts and sustains both body and soul?

‘Supposing there was a bright fire in the grate, with lots of little dancing flames,’ she murmured. ‘Suppose there was a comfortable chair before it – and suppose there was a small table nearby with a little hot – hot supper on it. And suppose”- as she drew the thin coverings over her – “suppose this was a beautiful soft bed, with fleecy blankets and large downy pillows. Suppose – suppose –’ And her very weariness was good to her, for her eyes closed and she fell fast asleep.

Of course she awakes and finds it’s come true…

Secret rooms in children’s fiction are not Freudian symbols of sexual awakening, nor do they represent a static no-place-and-no-time from which it is necessary to be rescued. They are miraculous, transformative spaces in which a child is protected and nourished,

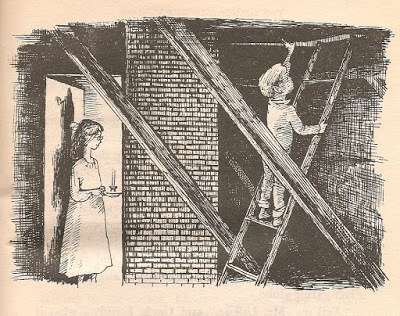

Picture credits

The room at the top of the tower, from 'Thorn Rose', by Errol le Cain, 1977Bluebeard, by Jenny Harbour, 1921 The Search Begins, from 'The Diamond in the Window', by Erik BlegvadMaria's Room from 'The Little White Horse', by C. Walter HodgesTolly's room, by Peter BostonTolly's room, by Katherine Langrish Heidi's hayloft, by William SharpHeid's dream, by William Sharp

Published on July 14, 2016 06:38

June 29, 2016

In the Green Chapel

On the last weekend in May my husband and I went down to Dorset for a two-day holiday, the first for many months. It was a fraught time; my mother was failing, increasingly frail after a prolonged hospital stay. But she was home at last, where she wanted to be. A wonderful friend was caring for her, and family members visited daily.

On the second (and final) day of our break we decided to explore a small wood tucked into a fold of the downs between Puncknowle and Little Bredy. Somewhere in the middle of it, according to the map, there was a ruined chapel. Leaving the car on the edge of a rutted track, we set out in the teeth of a cold wind along a deserted, stony lane. The tops of trees were visible over fields to our right, but the lane kept at a distance for some time. After about a mile it bent downhill; we climbed a stile and entered the wood.

It felt very old and very quiet, and maybe it was my mood, but it felt sombre. Fangorn Forest came to mind, though later another comparison occurred to us, Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood -- in which the naive and bewildered adventurer penetrates deeper and deeper into a limitless, terrifying, mythical past -- a scant square mile of English woodland from whose borders you may never emerge. Mossed-over tree trunks leaned this way and that, ferns grew on the boughs, all was wet and green. We crossed a slimy plank bridge. A crow crouched in the ditch beneath, sick perhaps, for it never moved.

The wood wasn't large, but it was remote, deep in the country, and it wrapped us in damp silence. As we followed the narrow path I felt a sort of awe. The place wasn't friendly. Not inimical, but it was secret, closed, watchful. We trod carefully, not sure what to expect or where to look for the ruins. Then we saw them. The path ran straight in under the archway.

We went through into the chapel. No one was there, and nothing was left of the chapel except the archway itself: the once-sacred space was now roofed by air and open to the whole wood, but a small altar and wooden crucifix at the eastern end gave an unexpected, powerful aura to the place. A simple ruin can seem anonymous, irrelevant, empty. This one still meant something. It had focus.

The outspread arms of the carved wooden Christ seemed to greet with measured, severe acceptance all comers, of whatever faith or none. Behind the altar lay a fallen tree. Someone with a chainsaw had cut the stump into a rustic throne, the raw yellow wood harsh and startling against the green.

Offerings lay on the altar. A jar full of bluebells, now dead. Twig crosses, coins, smooth pebbles from the beach, tea lights, sprigs of holly. People had come here recently, to bow their heads perhaps to Christ, perhaps to the spirit of the wood, and in either case - what? - perhaps to experience a sense of awe, humanity's shiver of insignificance before nature and the greatness of the world.

It was a space which felt more pagan than Christian, at least as we understand modern Christianity, though a medieval monk might have recognised it, for the Cistercians built this chapel and dedicated it to St Luke, traditionally a physician and healer. You could imagine Robin and Marian making their vows here.

Bluebells and ferns sprang from the stones of the altar, and someone had hung a dream-catcher from the crucifix. In the earth floor of the chapel were three grave-slabs, recent burials from the mid 1940s, presumably of some previous owners of the wood. 'And in that sleep of death, what dreams may come...?' Maybe the dream-catcher helps. Or maybe in this woodland setting, they sleep sound.

Some places do have auras; I remember years ago visiting Iona in the Hebrides, the Holy Isle: it was full of light, even the stones on the beach seemed to shine and the waves were like glass. This, by contrast, was an uncomfortable spot. Calm, intense: numinous even. But brooding, subduing. We left, glad to have seen it but glad too, on my part at least, to be gone.

The path took us uphill, out of the wood. We skirted an open field, crossed a farmyard, struck the lane and a narrow road running down valley. It was late morning, and my phone rang. My brother's voice. Bad news, he said. She's had another stroke. She's going. No, not yet, but very soon.

As we ended the call, I wished for a moment I had said a prayer in the Green Chapel, and then I thought, no. Whatever it may be like on other days, on the day we visited it wasn't the place in which to remember my mother, who was all sunshine. And yet it did speak to me -- in words of resignation, melancholy and loss, like fine rain that softens the earth and air and evaporates into mist.

Then again, maybe we simply take our moods with us. I don't know.

Published on June 29, 2016 06:24

June 17, 2016

Faerie-led

I had the good fortune recently to be able to attend the fourth annual Tolkien lecture at Pembroke College, Oxford, delivered by the inspiring writer, editor, artist, and my dear friend, Terri Windling. There can be few if any who are better read in fantasy literature both old and new, and her lecture, 'Reflections on Fantasy Literature in the Post-Tolkien Era' developed into an eloquent and heartfelt plea for 'slower, deeper, more numinous' fantasy. Terri set a challenge to all those of us who write, read, review and love modern fantasy: Tolkien's themes of epic conflict between forces of good and evil echoed the two great wars of the 20th century; his work was at the time both ground-breaking and relevant. Can we writing today find themes relevant to the problems our 21st century world now faces, such as the ecological and social disasters triggered by climate change? You can hear Terri speak by clicking the link below.

What does this mean? Should we be hunting for a theme and wrapping some fantasy around it? Of course not. You can't fake sincerity. Message-led fiction of whatever variety is rarely successful. Where there are exceptions (I'll give you 'Black Beauty') it's when such books emerge from long-held inner meditations and conviction. But as John Keats said, 'if poetry come not as naturally as the leaves to the tree, it had better not come at all.' By this he didn't mean 'don't write unless you're inspired'; he means that the words you write must spring from the truth within you. It can't be forced. But if there's no truth, you are short-changing the reader and cheating yourself.

So - can fantasy say anything true or profound? This sort of doubt levelled at fantasy was once levelled at all fiction. What makes a writer choose one genre over another, anyway? Why are some drawn to contemporary fiction, others to historical fiction, fantasy or thrillers? I know and admire a number of authors who can handle a variety of forms, but there are many like myself who stick to a single last. I began writing fairy tales when I was ten, and I've been faithful ever since. This doesn’t mean I haven’t had qualms. I’ve asked myself, in the past, what relevance tales of magic and fantasy have or can have to the problems of life. Can they ever really be serious? Shouldn’t I – shouldn’t I? – be writing something more meaningful?

I do find meaning in fairy tales. They offer the kind of metaphorical, personal, elusive meaning that poetry affords: and I have come to the conclusion that what is done with a whole heart, with love, and with as much truth as I can personally muster, must be good enough. More than that is out of my control. I have no choice. There is in writing, as in all art, something that feels remarkably like outside inspiration: a fierce compulsion that grasps you by the hair and demands and absolutely requires: this is what you will write about. This, and this alone. If you disobey it you feel restless, haunted. You can't forget or ignore it. You can't turn your back and decide to write about something else. (If you try, it's likely to go dead on you.)

The problem is that the divine or daemonic impulse only takes you so far. It sets you going and then leaves you to stumble along on your own, as best you can. If you’re lucky you’ll get occasional vivid flashes to light your path, but for the rest, you need to learn the craft. You need technique, patience, persistence and the ability to learn from criticism. This applies no matter what type of fiction you happen to have fallen in love with.

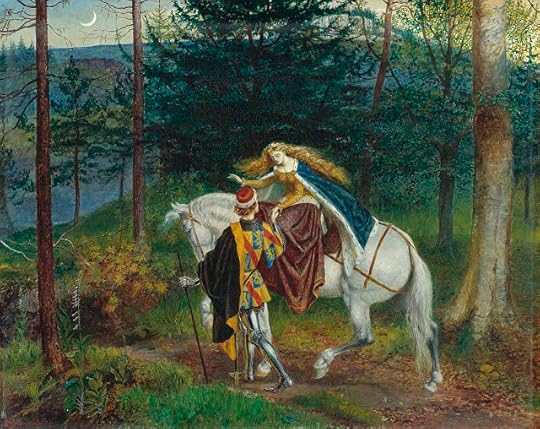

But it’s good to be aware of the particular pitfalls of your chosen genre. I wouldn’t like to speak for others, but in the early stages of my career as a fantasy writer I was anxious about the possibility of getting carried away by colourful but superficial effects, and forgetting or neglecting emotional truth. Fairies are after all notorious for their cold hearts. John Keats, something of a touchstone of mine, warns us in 'La Belle Dame Sans Merci' that playing with magic is perilous. The faerie lady's kisses may suck the living soul out of you; the magic casement opens on faerie seas 'forlorn', and: 'Forlorn! the very word is like a bell/That tolls me back from thee to my sole self...' Fancy, says Keats, is a 'deceitful elf'. Fantasy needs to keep faith with reality, to have at least one foot on solid ground while at the same time leading us away, lifting our eyes to the blue horizon, the edge of the known world, the white spaces on the map. That sense of never-attainable mystery, as Terri reminds us in her lecture, is one of the things which brings us back again and again to breathe the air of Narnia, Earthsea, and Middle Earth.

Characters, too, need space to breathe and live. I don't know about you but I'm far more interested in Aragorn as Strider, the weatherbeaten ranger from the North, than I would be if I only knew him as the heroic King of Gondor. Ulysses is more than a hero island-hopping from one marvellous adventure to another; he's a war-weary veteran desperate to get home. Malory’s Lancelot isn’t just the best knight in the world and a hero sans reproche, he’s a breathing, fallible man torn between his honour and his sense of sin, his love for Arthur and his love for Guinevere. He knows he’s unworthy of the Holy Grail – so when he’s finally allowed to perform a miracle of healing, he reacts with uncontrollable tears, weeping ‘like a child that has been beaten’.

'Slower, deeper, more numinous fantasy'? Yes, please.

Picture credits

La Belle Dame Sans Merci by Walter Crane, wikimedia commons

La Belle Dame Sans Merci by Frank Dicksee, wikimedia commons

Picture credit: Thomas Rhymer by Joseph Noel Paton

Published on June 17, 2016 06:33

June 2, 2016

'Malefice' - A guest post by novelist Leslie Wilson

The first witches I encountered were Macbeth's hags, and I was only five. That was because my mother, who was training to be a primary school teacher, had helped stage a glove puppet performance of the play, and afterwards I got her puppet to play with. She had a papier-maché head with bulging eyes and a hooked nose (of course), a lot of grey woollen hair, a pointy hat made of felt and a black dress under a rather elegant sleeveless purple satin overdress decorated with silver stars, testament to my mother's sense of style. You can't be terrified of a witch who lives in your toy box, and I just thought she was fun, as well as giving me the opportunity to happily (and incorrectly) chant 'Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble'.

The creature who did give me nightmares was the Witch Baby from 'Old Peter's Russian Tales,' with her iron teeth and insatiable appetite.

'Eaten the father, eaten the mother,

And now to eat the little brother.'

The thought of those pointed iron teeth (sharpened with a file) continued to be a terror to me, and it still wakes a residual shiver on me now. It's allied to the vampire fear, I suppose; something that looks human opens its mouth and there are the teeth all ready to eat you with.

In 1990, I found myself writing a poem I only partly understood, and called Hecate. It contained this verse:

This year, the night wrapped her

velvet around me

sheltered my

naked white flesh

- yet once I fled

devouring, iron-toothed hags -

this year

I have turned to the

shadows for healing.

And I said to myself: 'I'm going to write a novel about a witch.'

I wanted an English witch; a witch out of history, and preferably local, so I phoned up the County Archivist's office in Reading and asked if they had any record of witch prosecutions. The man I spoke to told me about Mabel Modwyn, of Waltham St Lawrence: 'widowe abact 68 years old arraigned for witch craft at Redding 29th Feb: and condemned on the 5th of March, 1655. Shee lived at ye south-wist cornr. of lower Innings in ye cornr. next to Binfield'.

Old house, Waltham St Lawrence, copyright David Wilson

Old house, Waltham St Lawrence, copyright David WilsonThe man couldn't understand why I was so delighted with this very scant piece of information. Clearly, if I'd been a historian it would have been disappointing, but it gave me a place to visit, and a period; from having the whole of English history to choose from, I had been given a date that was highly congenial to me, since it was within the Commonwealth period, which has always deeply interested me. It was also a period of great social upheaval. I was told that there was a typed book of extracts from the Waltham Parish Register in the library, and there I found the brief paragraph about Mabel again, and just below it, the story of a suicide who was secretly buried in the churchyard by her son and female relations. And that gave me the first chapter of my novel: my witch's daughter and son-in-law in the churchyard at midnight, fighting the flint-laden Berkshire clay with their spades. I sat down and wrote that chapter; it poured out of me and needed very little editing later on. I changed the witch's name, however, as it seemed to me that there was something slightly comedic about Mabell, particularly with two lls at the end.

Waltham St Lawrence Church

Waltham St Lawrence ChurchThe story of witchcraft is about the intersection of fairytale/folkore and history; it's about economic factors and social stresses, but also about long-held beliefs which one might call peri-religious, since they use Judaeo-Christian imagery, but are not, emphatically, the official doctrines of the Church. I'd thought I was going to write about the Great Witchhunt of the seventeenth century, but I soon discovered that it never really took off in England, not even when James the First came south from witch-hunting Scotland and introduced a much stiffer Witchcraft Act. The witches in Macbeth are probably a compliment to his beliefs. Only in a couple of cases, such as Matthew Hopkins's Essex witchhunt or the case of the Pendle Hill witches, did England see the active seeking out of possible witches and the naming of other witches by unfortunates under torture. As for the organised witch-cult of popular fantasy, there is no evidence for it.*

In England, witch accusations were a sporadic thing, and didn't inevitably end in conviction; when it did, the offenders were sometimes mildly dealt with by the Church courts, sometimes they were swum in ponds and drowned (which proved their innocence, since the water wasn't supposed to accept a witch; floating was evidence of guilt). Sometimes they were brought to court for maleficent witchcraft, and in a few cases, hanged. They were not burned alive (though the bodies sometimes were, which in an era that believed in bodily resurrection was just as bad). But it demonstrates how sparsely distributed English witch prosecutions were that people believed a witch would burn, and it's on record that once even a judge thought that was the penalty, and had to be corrected, in open court, by his clerk.

So, you might think, not much drama there. Yet drama can be just as powerful with a restricted cast, on a small stage, and the stresses and murderous tensions within a small community are the very stuff of drama, particularly when you're dealing with people whose lives are so very different from our own.

A German friend, who'd spent a year travelling in Latin America between university and starting work, told me that he came to small villages and towns that made him understand 'One Hundred Years of Solitude', because they simply had a different kind of reality. I kept that in my head while I was writing the book. This was a world without street lamps, for one thing, when if there was no moon the only light the poor had was a rushlight (a rush dipped in tallow). Anyone who's stayed anywhere in the depths of the country knows about that all-encompassing darkness, though street lamps have largely banished it (and the stars, though not, where I live, moonlight) from modern European life. What might be in those deep velvet shadows beyond the reach of the faint, fragile rush-light, or even the extinguishable candles of the wealthy? I can well remember the terror of the dark in our Victorian house in Kendal, where my mother and brother did see a ghost, though I never did, a little old lady who walked up and down the stairs.

To investigate those shadows, I turned to broadside ballads, as well as reading historical accounts of witch beliefs in England. When I went to Cecil Sharp house to read them, the librarian told me that they were the 'tabloids' of that time. I think we have a better parallel nowadays, in the stories that go viral on the Internet. Those stories went viral more slowly, as diseases moved more slowly before the age of jet travel; they trudged along the muddy roads of England in pedlar's packs, but they spread. So everyone knew that the Devil sometimes came to poverty-stricken old women, and sometimes old men, and bargained for their souls, the price of which was truly pitiful: often no more than about a penny a day for the rest of their lives, but also the power to harm their fellow creatures as well, and many an old creature scraped a living through her neighbours' nervousness about offending her (or him), and thus escaped starvation. The witch story had its utility - up to a point.

The image we often have of this scenario is the 'harmless old woman' wrongly accused, but the harm occurred, and if the victims had offended the woman, and if she'd scowled, or shaken her fist, or even worse, gone off muttering 'you'll pay for this', there was the story all ready to apply to the events. So when my witch, Alice was refused 'yeaste to make beere', when her bees were stolen by her neighbour, when she was insulted by the village no-good drunk, and the Squire's servant refused to buy her honey, her revenge was terrible; the butter turned rancid (offences against butter ranked high in the tally of witch's crimes, incidentally, hardly surprising when butter-making was such a difficult, chancy business, particularly in summer), a child's hands suddenly turned the wrong way round and couldn't be mended till she'd been made to scratch the witch's cheek; a beam fell on the offending servant's head, children and livestock died, the bee-stealer was lamed all along one side of her body, and the village drunk was pursued through the night-time lanes by the witch's black dog, with coal-red eyes. Alice once made a man walk on his two feet all the way up a wall and across the ceiling upside down, like a fly (drawn from a broadside ballad), but that was outside the village and only she knew about it.

Hare familiar

Hare familiar It's easy to patronise these beliefs, looking back from what we believe to be a more scientifically-oriented age, but throughout history human beings have made up narratives about the world and how it operates, and what we might nowadays dismiss as myths were as widely accepted in those days as narratives about strokes, hysteria, the effect of warmth on lactic products, and chance accidents would be nowadays. In any case, those other narratives still play in our modern world; horoscopes, 'healers' and 'dieticians' who diagnose by swinging a pendulum over you, fear of a single magpie, of the ladder over the pavement, touching wood - only we can reach for rationalism if we get spooked by these things, an option that wasn't so available to our forbears.

If you weren't sure who had harmed you, or you thought you knew, but wanted your suspicions confirmed, you could turn to a 'cunning person', analogous to witch doctors in Africa (though there, nowadays pentecostalist pastors are often involved). They used magic and quasi-religious rituals, many of them undoubtedly of great antiquity and pre-Christian, though Christian symbols were incorporated to placate the Church authorities. They found treasures and stolen property, undertook healings (some of them fairly scary, such as dragging people through bushes). The marjority of them were men, and sometimes middle-class men, too, but there were cunning women also. And they fingered witches. In England the cunning person's evidence was often crucial if a witch was brought to trial. In Scotland and continental Europe, the Great Witchhunt of continental Europe and Scotland scooped up cunning folk along with witches, which has confused many people's ideas of what a witch was. That's not to say that cunning folk weren't prosecuted for dubious magic in England - they were, and were even referred to as witches, sometimes 'white witches', but in England, it was very rare, though it did sometimes happen, that a cunning person was accused of maleficent witchcraft; ie, harming property and people and sometimes causing death. I did use this scenario, however, and therefore it was part of the story that the community has turned against Alice. People did say that 'you can't trust cunning folk.' They were slightly outside the community. Alice has always been lonely. But the key to her death lies in the relationships that have turned toxic.

Lychgate, Waltham St Lawrence (where coffins used to rest).

Lychgate, Waltham St Lawrence (where coffins used to rest). This story, then is about a woman who loved Alice and wished she didn't, a clergyman who turned his coat to match the times, a Royalist one moment, a Parliamentarian the next (like the Vicar of Bray), who loathed himself, about a mean-spirited, pernicketty woman with a skeleton in the family closet, a man with a grudge, a churchwarden with a guilty secret - all of whom have come to believe that the death of an old woman will make them safe. In that way, at least, the English witchhunt is related to the Continental orgies of torture and judicial murder. Norman Cohn, in his introduction to his history of the Great Witchhunt, 'Europe's Inner Demons', drew an analogy between that and the Holocaust, the 'Final Solution.' You find someone to wipe out, and then everything will go well, that's the story. We know it too well. Gretel pushes the witch into the oven and she turns to ashes, sister and brother return home. and not only have they found pearls and jewels in the witch's house, but the evil stepmother who wanted to get rid of them has died. The newly wealthy children are received only by their own penitent and joyful father. It's one of the most dangerous stories we tell ourselves. Alice knows that her death is mostly to do with the people who send her to the gallows; their fears, their hatreds, their darkness. 'You needed the harm,' she says to the Vicar.

But in the end, she's worn down, forced to accept her role in the fairytale. 'If I believe what they believe,' she thinks, 'I will not be completely cast out.' She's a human being; she needs her community, even if it means accepting that she's evil and has done the Devil's work. Indeed, one of the issues that fascinated me in writing the book was the way in which people do confess to crimes in 'appropriate' ways, and the ways in which guilt can be foisted onto people.

Talking to the Vicar in her cell, Alice says: 'You talk about truth and falsehood as if they could be weighed out like dried peas. But you don't really want the truth, nobody does. We all want short weight, and have it made up with falsehood. Then we feel safe.' In fact, only one person in the novel really wants the truth in all its bewildering complexity; Alice's daughter, Big Margaret, who begins by hating her mother, but who does find a measure of compassion and understanding through reflecting on Alice's story, particularly the last chapters. I wrote those in a kind of trance-state, just letting the words out onto the page. That is the strange thing altogether about this book. It's solidly rooted in research, but I've never been so little aware of the process of writing. It's the weirdest book I ever wrote, when I turned to the shadows.

Malefice is now available as a Kindle book (see this link)

Visit Leslie at her website: http://lesliewilson.co.uk/

*For information about the witch cult fraud, see

http://england.prm.ox.ac.uk/englishness-Margaret-Murray.html

Picture credits:

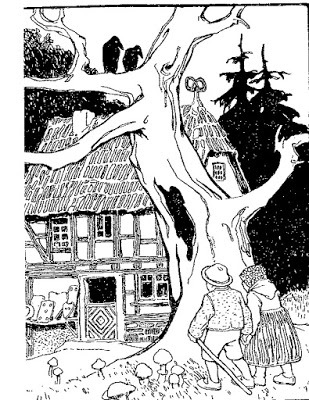

Hansel and Gretel - from a copy of Grimm's Fairy Tales, 1907, owned by Leslie Wilson

All photos copyright David Wilson

Published on June 02, 2016 00:30

May 17, 2016

Tiny Fairies

I am not entirely sure why tiny flower fairies are currently regarded by so many adults with such dislike. Believe me, they are: I was present at a session at the World Fantasy Convention in London in 2013 when a number of high-profile panel members reviled the Victorians for their infantilisation of the fairies. Maybe it’s something to do with the Celtic revival and the perennial desire – which I emphatically share – to get fantasy and fairy tales taken seriously, to present them as fit for grown-up attention. This is often done by emphasising the folk-roots of fairy tales and their relevance to adult concerns such as death and sex. I do get it. Frivolous tinselly things with wings hardly cut it in this context. The Flower Fairies, or pixies such as the one I read about as a child in Enid Blyton’s ‘A Story-Party at Green Hedges’, who painted the tips of the daisies pink – I didn't really mind them and I still don't, but how can these compare with the sexy Queen of Elphame? Well, I want to defend the Victorians. They were not responsible for the invention of the diminutive fairies so deeply unfashionable today. Indeed, my mission in this post is to convince you that tiny fairies are nothing to be ashamed of and that their ancestry is as ancient as that of any other supernatural being.

If you think about it even for a moment it's obvious that miniature fairies have been around for much longer than the Victorians. Our first stop is 1597, when Shakespeare’s Mercutio takes off in his long, exhilarating riff about Queen Mab:

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comesIn shape no bigger than an agate-stoneOn the forefinger of an alderman,Drawn with a team of little atomiesOver men’s noses as they lie asleep.Her wagon spokes made of long spinners legs, The cover, of the wings of grasshoppers;Her traces, of the moonshine’s watery beams,Her collars, of the smallest spider web,Her whip, of cricket’s bone, the lash of film,Her wagoner, a small grey-coated gnat,Not half so big as a round little wormPricked from the lazy finger of a maid.Her chariot is an empty hazelnutMade by the joiner squirrel or old grub,Time out of mind the fairies’ coachmaker...

And that’s not even half of it. Ebullient, unstoppable, Mercutio just keeps on going – telling how Mab tickles, blisters and frightens men and women with dreams, till finally, reverting from literary fancy to folklore, he identifies her with hobgoblins and the Nightmare – and of course, sex:

This is that very MabThat plaits the manes of horses in the night,And bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs,Which once untangled much misfortune bodes,This is that hag, when maids lie on their backsThat presses them and learns them first to bear,Making them women of good carriage.

It really is this magnificent flight of fancy which establishes Mercutio’s charisma, and lends such poignancy to his death.

Shakespeare clearly expected his audiences to be unfazed by tiny Queen Mab, or by the notion that the lesser fairies of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ might ‘creep into acorn-cups’, or that Ariel in ‘The Tempest’ might lie in a cowslip’s bell or ride on a bat’s back. Of course the actors playing such characters were adult-human-sized – although probably at least some of the non-speaking fairies were children, as in many performances today. The point is that Shakespeare asks his audience to imagine that his fairies are tiny, and there would be little point to this if the notion of miniature fairies had been an unfamiliar one. It wasn’t. Even in Shakespeare's day, tiny fairies had already been around for a long time.

Twelfth-to-thirteenth century Gervase of Tilbury tells a number of supernatural or fairy tales in his Otia Imperiala written to amuse the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto IV. One of these is about some tiny English fairy creatures he names ‘Portunes’. Here is a translation of his account, taken from Thomas Keightley’s ‘The Fairy Mythology’(1828):

It is their nature to embrace the simple life of comfortable farmers, and when on account of their domestic work, they are sitting up at night, when the doors are shut, they warm themselves by the fire, and take little frogs out of their bosom, roast them on the coals and eat them. They have the countenance of old men, with wrinkled cheeks, and they are of a very small stature, not being quite half an inch high.

Half an inch – about one and a quarter centimetres – is startlingly small, and Keightley suggests at this point that by a copyist’s error, pollicis– ‘thumb’ – has been subsituted for pedis –‘foot’. Six inches high would seem much more credible for a creature capable of roasting little frogs. Gervase continues:

They wear little patched coats, and if anything is to be carried into the house, or any laborious work is to be done, they lend a hand, and finish it sooner than any man could. It is their nature to have the power to serve, but not to injure. They have, however, one mode of annoying. When in the uncertain shades of night the English are riding anywhere alone, the Portune sometimes invisibly joins the horseman, and when he has accompanied him a good while, he at last takes the reins, and leads the horse into a neighbouring slough; and when he is fixed and floundering in it, the Portune goes off with a loud laugh, and by sport of this sort he mocks the simplicity of mankind.

This sort of behaviour is just what we expect of Puck or Robin Goodfellow in the 16th century, three hundred years later. House-fairies are generally quite small. An example is the Grimms’ tale of ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’. In the original German text the tiny shoemakers are ‘zwei kleine niedliche nackte Männlein’, ‘two pretty little naked men’, and the title is ‘Die Wichtelmännchen’, which Margaret Hunt in 1884 chose to translate as ‘The Elves’ – but such creatures more properly belong with the Scots brownies, English boggarts, and the Scandinavian nisses and tomtes. According to Keightley, the Norwegian Nis is ‘of the size of a one-year-old child, but has the face of an old man.’ Nisses dress in grey, wear pointed red caps, help in house and farmyard, and can be seen in winter jumping about the yard in the moonlight. They are mischievous. The Swedish Tomte can be much smaller:

In Sweden the Tomte is sometimes seen at noon, in summer, slowly and stealthily dragging a straw or an ear of corn. A farmer, seeing him thus engaged, laughed and said, ‘What difference does it make if you bring that away or nothing?’ The Tomte in displeasure left his farm and went to that of his neighbour; and with him went all prosperity from him who had made light of him, and passed over to the other farmer.

Gervase of Tilbury’s much earlier Portunes seem to be house fairies of this same type.

In the account of his journey through Wales in 1188, Gerald of Wales tells the story of Elidor, a twelve year-old boy who, hiding from his cruel teacher by a river bank, was rescued by ‘two little men of pygmy stature’ who led him away into a subterranean fairyland inhabited by many other pygmies ‘of the smallest stature, but well-proportioned for their size’ who rode on horses the size of greyhounds. In another legend related by the 12th century courtier Walter Map, a British king called Herla meets an unnamed, goat-footed pygmy king who dwells in splendid underground halls: ‘a pygmy in his low stature, not above that of a monkey’; and John Bourchier, Lord Berners, translating the French romance ‘Huon of Bordeaux’ in the early 16th century, describes the fairy King Oberon as only three feet high, with a beautiful face.

Shakespeare’s Oberon is apparently of human size – nothing in the text of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ directly suggests otherwise – but Shakespeare may well have read ‘Huon of Bordeaux’, so we cannot be sure: it’s possible he imagined all the fairies to be of less than human stature, varying only in degree. After all, Titania sends her fairies on miniature errands –

Some to kill cankers in the musk-rose buds,Some war with rere-mice for their leathern wings,To make my small elves coats…

Then fashion caught on. The folklorist Katherine Briggs writes in her 1959 book ‘The Anatomy of Puck’: ‘In the beginning of the Jacobean times, a little school of friends among the poets, Drayton, Browne, Herrick, and the almost unknown Simon Steward, caught by the deliciousness of Shakespeare’s fairies, and coming from counties where the small fairies belonged to local tradition, [my italics] amused themselves and each other by writing fantasies on littleness.’ In 1625 Robert Herrick (best known for ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may’) tells in his poem ‘Oberon’s Feast’ how Oberon sits at a mushroom table and quaffs a dewdrop from a violet:

And now we must imagine, firstThe elves present, to quench his thirst,A pure seed-pearl of infant dewBrought and besweetened in a blueAnd pregnant violet (etc etc…)

And Michael Drayton’s mock-heroic ‘Nimphidia’ (1627) describes the diminutive knight Pigwiggen arming himself with a cockleshell shield, a hornet’s-sting rapier and a beetle’s head helmet, before riding to the fray on a frisky earwig. In his ‘The Muses Elyzium’, 1630, a fairy wedding gown is composed ‘Of Ransie, Pincke and Primrose leaves’, while Browne has fairies who teach ‘the little birds to build their nests’ and serve up banquets of stuffed grasshoppers, roast ants, soused fleas and chine of dormouse. Enough already! Stop blaming the Victorians.

You might suppose that this kind of whimsy is a consequence of the decline of an actual belief in fairies and it may partly be so: but the whimsy lies more in the treatment than in the size of the creatures. People still could and did believe in tiny fairies and find them frightening. Katherine Briggs cites several 17thcentury spells to summon fairies and conjure them into a crystal glass:

An excellent way to gett a Fayrie … First gett an broad square christall or venus glass in length and breadth 3 inches, then lay that glass or christall in the blood of a white henne 3 wednesdayes or 3 fridayes…

And:

I.Coniure.thee.Elaby.Gathen.by.these.holy.names.of God.Saday.Eloy.Iskyros.Adonay. Sabaoth.that thou appear presently.meekly.and mildly.in.this.glasse.without.doeinge.hurt.or. daunger.unto.me.or any other.living. creature. and to this I binde.thee.by.the.whole.power. and.vertue.of.our.Lord.Jesus.Christ…

This particular spell goes on for pages, employing as safeguards every name of God and the Trinity which the magician can think up. The fairy may have been small, to be conjurable into a crystal glass three inches square, but her conjuror was clearly terrified of her.

I’ve said enough, I hope, to show that the diminutive fairies of late nineteenth and early twentieth century children’s fiction weren’t a Victorian invention. Tiny fairies have always been with us, and flower fairies appear to have originated with Shakespeare, Herrick and Drayton. Certainly by late Victorian times, at least for the educated classes, all terror had departed from the word ‘fairy’, and the troupes of little girls who danced in pantomimes dressed as gauzy-winged fairies in frilly dresses were purely decorative. But even Victorian flower fairies are not always as milk-and-watery as you might suppose. In George MacDonald’s 1858 fantasy novel 'Phantastes' the hero Anodos finds himself in fairyland and strolls at evening though a cottage garden at the edges of an enchanted wood full of beauty and horror. There are flower fairies in the garden, but they are a wild bunch.

The whole garden was like a carnival… From the cups or bells of the tall flowers, as from balconies, some looked down on the masses below, now bursting with laughter, now grave as owls; but, even in their deepest solemnity, seeming only to be waiting for the next laugh. Some were launched on a little marshy stream at the bottom, on boats chosen from the heaps of last year’s leaves …

Anodos witnesses a fairy funeral procession for a primrose ‘whose death Pocket [one of the other flower fairies] had hastened by biting her stalk’ and then, in true fairy fashion:

The party which had gone towards the house rushed out again, shouting and screaming with laughter. Half of them were on the cat’s back, and half more held on by her fur and tail, or ran beside her; till, more coming to their help, the furious cat was held fast; and they proceeded to pick the sparks out of her with thorns and pins, which they handled like harpoons.

MacDonald’s flower fairies are feral, amoral, unpredictable. As Anodos walks deeper into the forest, things become more sinister: the path is lined by glowing flowers:

From the lilies, from the campanulas, from the foxgloves, and every bell-shaped flower, curious little figures shot up their heads, peeped at me, and drew back. They seemed to inhabit threm as snails their shells, but I was sure some of them were intruders, and belonged to the gnomes or goblin fairies, who inhabit the ground and earthy creeping plants. From the cups of Arum lilies, creatures with great heads and grotesque faces shot up like Jack-in-the-Box, and made grimaces at me; or rose slowly and slily over the edge of the cup and spouted water at me, slipping suddenly back … and I heard them saying to each other, evidently intending me to hear … ‘Look at him! Look at him! He has begun a story without a beginning, and it wll never have any end. He! he! he! Look at him!’

No wonder Anodos soon finds that ‘a vague sense of discomfort possessed me, as if some evil thing were wandering about in my neighbourhood…’ (Which indeed there is.)

Summing up: tiny fairies shouldn’t be regarded simply as childish, Victorian to modern inventions. I can’t help thinking that household fairies such as brownies and boggarts and nisses may have descended from the even more ancient household gods – the Latin laresand penates, or the teraphim which Rachel stole from her father Laban without telling her husband Jacob. In one of the more comic episodes of the Bible, Laban pursues and catches the errant family and demands his gods back:

Jacob did not know that Rachel had stolen the gods. So Laban went into Jacob’s tent, and Leah’s tent and that of the two slave girls, but he found nothing. When he came out of Leah’s tent, he went into Rachel’s. Now she had taken the household gods and put them in the camel bag and was sitting on them. Laban went through everything in the tent and found nothing. Rachel said to her father, ‘Do not take it amiss, sir, that I cannot rise in your presence: the common lot of woman is upon me.’ So for all his search, Laban did not find his household gods. [Genesis 31, 33-35]

These gods must have been small and portable, probably small fired-clay images like the ones pictured below. The other common lot of woman was to do cook and clean and bear children: if the household gods could help with that, no wonder Rachel wanted to keep them. (Her sister Leah was probably in on the theft too.)Compared with Jehovah, the little household gods weren’t much, but they were personal, friendly and domestic: as imbued with imagined personality as a child’s teddybear – and as interested in the fortunes of their possessors.

Picture credits:Fairy Song, Arthur RackhamPuck and Fairy, Arthur RackhamElves and Shoemaker, prob. by George CruickshankFairies Attacking a Bat, John Anster FitzgeraldThe Quarrel of Oberon and Titania, Sir Joseph Noel Paton Fairy Banquet, John Anster FitzgeraldDeath of a Fairy, John Anster GitzgeraldTeraphim from Ur, probably similar to those Rachel hid: http://www.womeninthebible.net/Menstr...

Published on May 17, 2016 01:27

May 7, 2016

The Weirdstone of Talybont and FIRST LIGHT

On a bright spring day last year I was sitting on a bank beside a deep-cut track high up in the Brecon Beacons. I’d walked far enough, but my husband David wanted to get to the top of the next little peak. He went on ahead with our brown-spotted Dalmatian dog Polly. I sat on the bank admiring the view over the Talybont reservoir, when a blue sparkle caught my eye. From the track near my feet I picked up an extraordinary stone. It had weathered out of the layers of old red sandstone of which the hill was formed, tumbled on to the track and split in two – probably not long before, for the break was still sharp-edged and clean. On each of the fractured faces was traced a glittering blue lozenge. My mind leaped to a much-loved childhood classic. ‘It’s a Weirdstone’, I thought...

It so happened that a week later I was at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, listening to Alan Garner argue with forthright wit and passion that there is no fracture, no true gap between the arts and the sciences. All human creative endeavour is part of a whole – as my stone was before it split in two.

And a month later I was honoured (to my great surprise and delight) by an invitation to contribute to ‘First Light’, a collection of essays written in celebration of Garner’s 80th birthday. I was frankly awed by the other contributors. Not only writers but archeologists, physicists, artists, historians – Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, Francis Pryor, Rowan Williams: the list runs on.

As I wrote of how Alan Garner’s books had changed my imaginative life, it was the finding of the Weirdstone that opened the way into what I wanted to say and how to say it. I shan’t repeat any of that, but here’s something I didn’t include in the essay: as soon as I picked that stone up, it was as if I’d entered a world of fiction. I looked up the track to the place where it vanished over the skyline, a quarter of a mile away. High on the sharp summit to its right I could see the distant figures of David, and Polly the dog. I waved to David. He waved back, then pointed. You remember how in ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ the svart-alfar come pouring out of the Devil’s Grave to attack the children, Colin and Susan? Right on cue, over the skyline came a band of goblin riders – half a dozen of them, bucketing down the track on little buzzing black motorcycles, the sun glinting off their black helmets.

I knew what they were but the dog didn’t, and she didn’t like the look of them. And she could tell they were heading my way. Within seconds of their appearance she was hurtling down the hillside after them, racing to my aid, as white against the green as the standard of Theoden King himself (if I may change fantasies for a moment). It was terribly funny but also very heroic and touching. With Polly pounding up behind, the goblin riders reached me and passed, each raising a gauntleted hand in courteous acknowlegement.

These things do happen if you pick up Weirdstones. Coincidence and magic seem to follow Alan Garner as seagulls follow ploughs.

I haven’t had time yet to read all of the essays in ‘First Light’, but enough to be able to tell you it’s a treasure trove. You’ll find essays by Elizabeth and Joseph Garner, by Teresa Anderson, the Director of the Discovery Centre at Jodrell Bank, by Philip Pullman, Elizabeth Wein, Bel Mooney, Robert Macfarlane… by David Almond, Frank Cottrell Boyce and Amanda Craig… and of course by the editor Erica Wagner, whose marvellous idea it was. It was crowd-funded, published by Unbound, and testifies to the extraordinary impact of Alan Garner as a writer and a man on so many different people in so many different walks of life.

Published on May 07, 2016 05:07

May 4, 2016

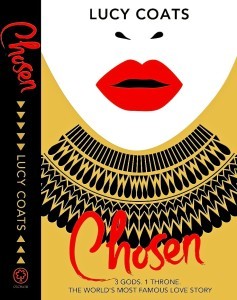

'Cleo' and 'Chosen' - the young Cleopatra novels by Lucy Coats

Full disclosure here. Lucy Coats is a friend of mine. This basically means that a couple of years ago she told me she was writing a YA novel about Cleopatra’s childhood and coming-of-age, set in a magical version of Ancient Egypt where the gods really exist, and first of all I fell over with jealousy-tinged admiration at the the sheer brilliance of the idea, and afterwards I got to read some of the drafts, which were also brilliant. The first book, ‘Cleo’, came out last year and the second, ‘Chosen’ has just been published by Orchard. I love them both - and what luscious covers!

Though everyone has heard of Cleopatra the Queen, her childhood remains a mystery. As Lucy says: Nobody knows much about Cleopatra’s path to the Pharoah’s throne, beyond the bare minimum of speculative dates, and even those are disputed. Who her mother was, when exactly she was born, what she really looked like are all mysteries. Her early life is a big fat hole in history, which I have jumped into with both feet and tried to fill. Such lack of solid information may be infuriating to the historian but for a writer it’s a gift beyond dreams, and the stuff of dreams is exactly what Lucy has woven into these two splendid historical fantasies. In ‘Cleo’ we first meet the child Cleopatra in a crowded palace room, fighting back tears at her mother’s deathbed. But this Cleopatra can see the gods themselves.

My mother opened her pale, bluish lips slightly and sighed. Only I could see the misty golden ka soul form that rose upwards from her body – a perfect mirror image of her mortal self. Only I could see the door opening in the air, the tall jackal-headed figure stepping from his reed boat and slipping into the mortal world. Only I could see his immortal hand stretching out to draw my mother’s soul through and sail off with her to the underworld realm. She held out her own hand to him and didn’t even look back once.

Threatened with murder by her two half-sisters, Cleo escapes from Alexandria with her best friend and slave-girl Charm, finds sanctuary in a far-off temple of Isis and becomes a priestess. There she learns her beloved goddess has plans for her. It’s up to Cleo to return to Alexandria, find a map locating the ancient shrine of the goddess, wipe out the treachery of those who betrayed her, and rescue Egypt from the evil god Am-Heh. Luckily Cleo has allies. Not only Charm, but the handsome young Khai, whose dark eyes stir many a heartbeat as Cleo grows into a warm-hearted, susceptible teenager. But not just any teen. Cleo may be as flirtatious and funny as Louise Rennison’s Georgia Nicholson, but she’s also a princess of Egypt, brave and ambitious, proud of her status and descent, royal to her fingertips. Lucy Coats never forgets the future fame of this young girl. Throughout both books we find little hints of Shakespeare’s ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ – Cleo’s maid Charm, for example, must be that very Charmian who ‘loves long life better than figs’ but who (we know) one day will follow her mistress into death. The friendship between the two girls is as just as much if not more important than Cleo’s romantic interests – and it will be lifelong.

In ‘Chosen’ (which if anything is an even better book than the first), Cleo as ‘the Chosen One of Isis’ journeys through the deserts of North Africa to the oracle at Siwah, and thence to Rome to bring back her exiled father, sweep Berenice from the throne and destroy the evil Am-Heh. And she meets a young Roman soldier called Marcus Antonius on the way…

What I love about Lucy’s version of Egypt is how rich, colourful and intense it is, full of sounds, scents and warm breezes. In a passage from ‘Cleo’, our sensual girl enjoys a massage after a temple dance:

The smell of rose-and-cinnamon oil filled the warm air, and the thin coverlet lay heavy on my naked hips and legs, almost too hot for this summer day. Through my half-closed eyes I could see the black silhouettes of swallows, dipping and darting against the harsh blue of the the early Akhet sky, hunting for airborne bugs over the Nile…

In ‘Chosen’, in more warlike mood, Cleo and her comrades approach an oasis after a long and grimy desert march:

We rode up out of the black sand in the heat of the afternoon and arrived at the oasis the desert tribes called Shore of the Sea. …The camels started to run as they smelt the fresh water … The green was intoxicating to my eyes, and the smell of it almost an assault on my nostrils. I slid down from Lashes as she dipped her muzzle in the water, snorting, shaking her lips and blowing great clouds of bubbles as she slurped and sucked. Total immersion in the past! You can sense how much fun the author is having, and it’s infectious. Quite simply, I enjoyed both books enormously. The two titles are suitable for older children, perhaps from thirteen up. Lucy doesn’t flinch from the dark side – there’s a fair bit of physical violence; you’ve got to be able to cope with some characters being eaten by crocodiles, for example – as well as a non-explicit, off-stage rape which is handled seriously but sensitively. However great the danger though, we can be sure Cleo and her friends will win through, with the supernatural power of Isis at their back and, leading from the front, Cleo herself, crackling with energy, life, and determination to fulfill her destiny as one of the most famous Queens who ever lived.

"CLEO" and "CHOSEN" by Lucy Coats are published by Orchard Books. You can find out more about Lucy and her books at her website, http://www.lucycoats.com/

Published on May 04, 2016 08:24

April 28, 2016

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: the book

"There are seven miles of hill on fire for you to cross, and there are seven miles of steel thistles and seven miles of sea."

The quotation is from an Irish fairy tale, 'The King Who Had Twelve Sons': the hero has to ride his pony over three-times-seven miles of punishing obstacles to reach the islanded castle where lives 'the daughter of a king of the eastern world, with a pearl of gold on every rib of her hair'. When I first read it, years ago, it seemed to me a metaphor not only for the creative effort and difficulty of writing a book, which was what I was currently engaged on, but of life and its struggles in general. Nothing worthwhile comes easy. And so this is what I named my blog, and now here is a book.

‘Seven Miles of Steel Thistles’ is a collection of my essays on fairy tales and folklore, published by the Greystones Press. Many of the essays began life as blog posts, but since blog posts tend to be ephemeral things, often written in haste, I went back to each and every one to revise and rewrite them. So at least half of the material here is new. You'll find me talking about fairy brides, Japanese fox-spirits, selkies and White Ladies - taking a new look at Cinderella and the Sleeping Beauty and other fairy-tale heroines - following the fortunes of the Lost Kings of Fairyland - finding what happened when William Butler Yeats successfully summoned the Queen of the Fairies, and wondering why and in what circumstances people actually believe in fairies.

On a personal note, the last year has been a difficult one. Much of my time has been taken up with caring for my increasingly-frail and much-loved mother; those of you who are dealing with similar situations will know what this means. Time has been scarce either to write or to update this blog, yet here it is, coming back to life, like the thin blades of green thrusting up through the sooty dust on the scorched hills.

Seven miles of hill on fire and seven miles of steel thistles and seven miles of sea to cross, and yet:

'He gave his face to the way, and he would overtake the wind of March that was before him, and the wind of March that was after would not overtake him.'

‘Seven Miles of Steel Thistles’ is available from Amazon in both print

and e-book formats

Published on April 28, 2016 01:14

April 16, 2016

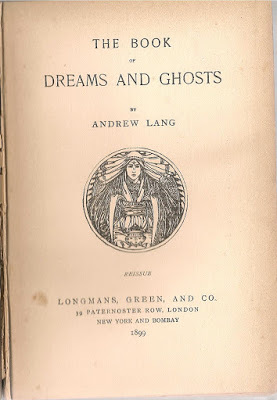

Dreams and Ghosts

I do love old books. They don't make them like that any more. I love the smell, the thick silky quality of the paper, the rough-cut, uneven edges, the gilt-embossed covers, the blackness of the print, and the tactile sense of so many other hands which have held it and turned the pages... A few years ago, wandering the labyrinthine passageways of our local second hand bookshop, I came across this 1899 edition of Andrew Lang’s The Book of Dreams and Ghosts. Even if I’d never heard of Andrew Lang I couldn’t have resisted that title. I bought it for a couple of pounds.

What it is, is pretty much what it says on the cover. A collection of supernatural or ghostly anecdotes taken from all kinds of sources: the key element being that none of them were originally offered as fiction. They are all, for what it’s worth, ‘true stories’. Many are contemporary accounts sent to Andrew Lang by various friends. Some are historical, but even the ones from old Icelandic sagas were intended to be read as factual accounts.

Lang was interested in recording and investigating what might loosely be termed supernatural phenomena, and in 1911 he was President of the Society for Psychical Research, but he was neither a believer nor a sceptic; of course his other interests lay in folklore, anthropology and fairy tales.

The author has frequently been asked, both publicly and privately: “Do you believe in ghosts?” One can only answer: “How do you define a ghost?” I do believe, with all students of human nature, in hallucinations of one, or of several, or even of all the senses. But as to whether such hallucinations, among the sane, are ever caused by psychical influences from the minds of others, alive or dead, not communicated through the ordinary channels of sense, my mind is in a balance of doubt. It is a question of evidence.

There is a great difference between a supposedly ‘true’ ghost story and a fictional one. I once lived in a small Yorkshire village full of very old houses (the one I myself lived in dated in part from the late seventeenth century). Our neighbours in the even older whitewashed farmhouse down by the beck had a Red Lady who sometimes looked out of one of the small upstairs windows. And they were used to hearing footsteps cross the floor overhead, when no one should be there. But that was it: there was no story attached. Further down the road there was a ford across the beck, and a medieval ‘clapper bridge’ made of two huge stone slabs known as ‘Monks Bridge’, probably because Fountains Abbey used to own much of the land. The cottage nearby was said to be haunted. Coming on foot up the unlit road one dark chilly night at about two o’clock in the morning, I was disconcerted to see someone lingering near the bridge, wearing a hooded garment which I took to be a cagoule. As I passed, the hooded person – whoever it was – slowly and very silently moved away from me down towards the ford and the rushing water. I didn’t think ‘ghost’, I thought ‘oddball’ and hurried on. Later, I wondered… And my own aunt was well known in the family for seeing the dead, including her husband, who once – pipe in hand – politely drew back to allow her to pass through a door in her Leeds Victorian terrace, some months after he had died.

The point about these stories is that there is no point. They have no real beginning, no middle, no end, no structure. They aren’t stories at all – just anecdotes. You hear them, you are impatient or fascinated according to your nature – and then you shrug, because there is no way to take them any further. People love explanations, of course, so sometimes there is an attempt to provide some kind of Gothic rationale involving hidden treasure, wicked lords, seduced nuns, suicides and murders. These are rarely convincing. ‘Real’ ghost stories (and nearly everybody knows one) are open-ended oddities, and quite frequently the person involved does not realise anything strange is happening until afterwards.

Here’s an example from Lang’s book:

The brother of a friend of my own, a man of letters and wide erudition, was, as a boy, employed in a shop. The overseer was a dark, rather hectic-looking man, who died. Some months afterwards the boy was sent on an errand. He did his business, but, like a boy, returned by a longer and more interesting route. He stopped at a bookseller’s shop to stare at the books and pictures, and while doing so felt a kind of mental vagueness. It was just before his dinner hour and he may have been hungry. On resuming his way, he looked up and found the dead overseer beside him. He had no sense of surprise, and walked for some distance, conversing on ordinary topics with the appearance. He happened to notice such a minute detail as that the spectre’s boots were laced in an unusual way. At a crossing, something in the street attracted his attention; he looked away from his companion, and, on turning to resume their talk, saw no more of him.

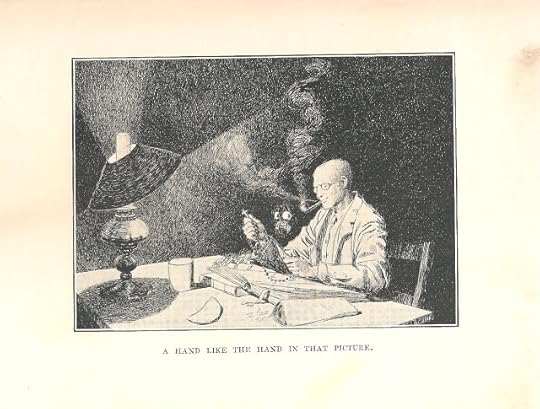

Here a number of details (the ‘dark and hectic’ features of the dead man; the curiously-laced boots), are presented as corroborative evidence. If the boy could describe the boots so minutely – well, he must have seen something! This sort of ghost story is very much alive and well in the oral tradition. ‘A funny thing happened…’ ‘A friend of mine told me…’ We enjoy listening; at least I do – but the teller is excused the structure of the literary ghost story. Because what happened is ‘real’, no other framework is necessary. M.R. James is very, very good at convincing his readers that his ghosts are real, and one of the ways he does it is to build in these inconsequential details ("the red cloth just by his left elbow") that underwrite the supernatural invasion. Here his scholarly hero Dennistoun is murmuring peacefully (for the moment) to himself, as he studies Canon Alberic's scrapbook: