Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 23

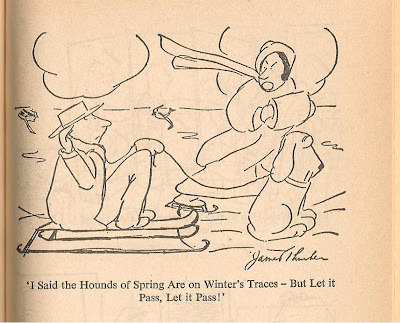

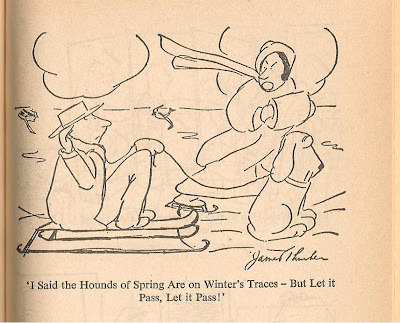

September 10, 2014

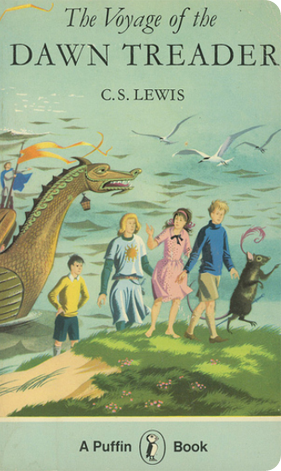

Re-reading Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

I have two very different personal memories relating to this book. One, vividly happy, is from childhood. The other comes from a time when I was a young adult working in London, and it still makes me cringe.

The childhood one first: aged nine, I woke one night to hear my parents criss-crossing the landing and my eight-year old brother crying in the bedroom next to mine. I called out and was told to be good, my brother was poorly, go back to sleep. Next morning I found he’d been rushed to hospital during the night. At a party the previous week, the children had been tossing each other cocktail sausages and trying to catch them in their mouths; my brother had swallowed one whole, stick and all. He hadn’t wanted to explain this in detail to my mother, as he thought she’d be cross. It perforated his intestine, and since the wooden stick didn’t show up on X-rays, the surgeon had to perform a major operation to find it. I’ve never felt comfortable around cocktail sticks since.

My brother stayed in hospital for some time. In those days the visiting rules were strict. I wasn’t allowed to see him, but I could see that he was (deservedly) being deluged with treats, toys and other goodies from friends and relations. To keep sibling rivalry in balance, my parents bought me the book I’d been longing for, the only Narnia book I hadn’t yet read: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. While they went visiting I curled up in an armchair – I can still feel its bristly upholstery against my knees – and was swept away into an open-air world drenched in light – the light of sunrise over the sea, the quiet sunlit passages of the Magician’s House, sunbeams slanting through the green waters of the undersea world, birds flying out of the rising sun to the table of the Three Sleepers, the almost painful light of the Silver Sea.

...when they returned aft to the cabin and supper, and saw the whole western sky lit up with an immense crimson sunset, and thought of unknown lands on the Eastern rim of the world, Lucy felt that she was almost too happy to speak.

Now for the second memory. I’m in my early twenties, chatting to a colleague, Richard. For some reason we are talking about the Narnia books, which he hasn’t read but is willing to try. Which one should he start with? ‘Oh,’ I say, ‘my favourites are The Silver Chair and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. I can quote from the beginning of that one.’ And I do: ‘“There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.”’ Richard starts to smile, and I continue from memory: “He didn’t call his father and mother ‘Father’ and ‘Mother’, but Harold and Alberta. They were vegetarians, non-smokers and teetotallers, and wore a special kind of underclothes.”’ Richard’s smile disappears. He says stiffly, flushing, ‘I call my parents by their first names, as it happens; and I’m vegetarian too.’

And thus I learned, not before time, that unthinking admiration for an old favourite can land you in the soup. What an idiot I was! Why hadn’t I noticed that Lewis was so prejudiced? Could he truly have believed that a dislike of tobacco, alcohol and meat makes a person some kind of prissy, unimaginative bore? Could he? Sigh.

TVDT doesn’t become the book I fell in love with until the story – and ship – gets beyond the Lone Islands. There are just too many unexamined value judgements going on before then. I don’t know if I need to pick them all apart, but how about this one, on only the second page of the story, where Lewis explains why Edmund and Lucy are staying with Eustace at all. Peter, it seems, is being coached for an exam by the old Professor. The children’s parents are going to America and taking Susan with them.

Grown-ups thought her the pretty one of the family and she was no good at school work (though otherwise very old for her age) and Mother said she “would get far more out of a trip to America than the youngsters”.

‘Pretty’ ‘no good at school work’ and ‘old for her age’ – a euphemism for sexual precocity – this, not The Last Battle, is the book in which Lewis dismisses Susan: and he never gives her another chance. Susan’s trip to America, though sanctioned by her mother, is viewed by Lewis as a dangerous frivolity, a trip to Vanity Fair or worse, and what she will ‘get out of it’ is – to use an old term of religious disapproval – worldliness. Why a liking for lipstick and nylons should be more worldlythan a taste for tobacco and beer, I don’t know, but this is farewell to Susan the archer, Susan the swimmer, Susan the gentle who ‘was so tender-hearted that she almost hated to beat someone who had been beaten already’. It’s all very silly.

Back to Eustace!

‘Still playing your old games?’ said Eustace Clarence, who had been listening outside the door and now came grinning into the room. Last year, when he had been staying with the Pevensies, he had managed to hear them all talking about Narnia and he loved teasing them about it. He thought of course that they were making it all up; and as he was far too stupid to make anything up himself, he did not approve of that.

As the story begins, Eustace is certainly spoiled, irritating, bad-tempered, self-centred and sneaky. This is staple fare for a children’s book: Roald Dahl does far nastier things with some of his characters, and anyway, in the tradition of Kipling’s ‘Captains Courageous’, the voyage will make a man of Eustace. But stupid’? No! Eustace isn’t stupid, just inexperienced and a bad mixer. He doesn’t enjoy fiction (or hasn’t been given much) and is therefore very ill-prepared for the adventure about to befall him. But his wonderful diaries full of self-deception, self-justification and complaints are the comical high point of the book, as funny as Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole – on whom Eustace must surely have been an influence.

6th SeptemberA horrible day. Woke up in the night knowing I was feverish and must have a drink of water. Any doctor would have said so. Heaven knows I’m the last person to try to get any unfair advantage but I never dreamed this water-rationing would be meant to apply to a sick man. In fact I would have woken the others up and asked for some only I thought it would be selfish to wake them. So I got up and took my cup and tiptoed out of the Black Hole we’ve been sleeping in, taking great care not to disturb Caspian and Edmund, for they’ve been sleeping badly since the heat and the short water began. I always try to consider others whether they are nice to me or not.

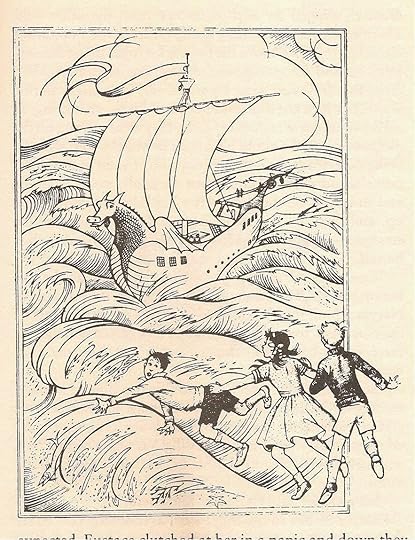

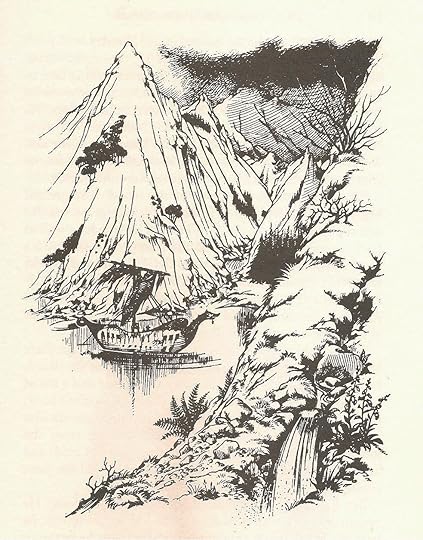

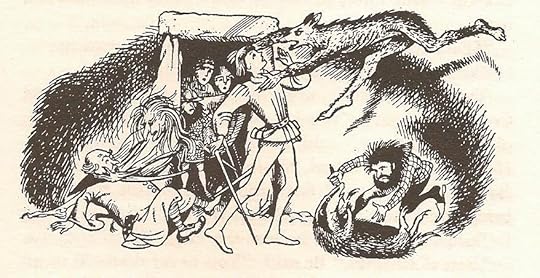

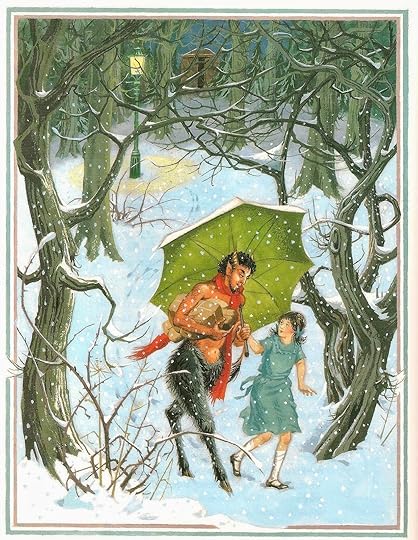

Eustace’s own adventure begins when the Dawn Treader drops anchor in a steep-sided valley – drawn here with a hint of Chinese delicacy by Pauline Baynes. Avoiding the work of setting the ship to rights he slips off into the interior and gets lost. Finding himself in a deep, bare, rocky ravine, he hears a noise behind him and turns to see…

The thing that came out of the cave was something he had never even imagined – a long, lead-coloured snout, dull red eyes, no feathers or fur, a long lithe body that trailed on the ground, legs whose elbows went up higher than its back like a spider’s. Bat’s wings that made a rasping noise on the stones, yards of tail.

…It reached the pool and slid its horrible scaly chin down over the gravel to drink, but before it had drunk there came from it a great croaking or clanging cry, and after a few twitches and convulsions it rolled round on its side and lay perfectly still with one claw in the air. A little dark blood gushed from its wide-opened mouth. The smoke from its nostrils turned black for a moment and then floated away. No more came.

I said this book was full of light and so it is, but there’s a lot of darkness too. As a description of death, this is about as grotesque and physical as books for young children get. All the dragons I’d ever read about were strong and splendid, requiring a St George at least to quell them. This weary, repulsive creature dies alone of natural causes before it can even get a drink of water– a touch which makes it pitiable, too. A cave full of treasure, and all it wants at the end is a sip of water! Which may become Eustace’s own fate as, gloating over the dragon’s hoard, he falls asleep with a diamond bracelet pushed up over his elbow.

All children know the panicky moment when a sweater sticks as you pull it over your head, or when a ring won’t come off your finger and your mother tries to ease it over your bruised knuckle with soap.

The bracelet which had fitted very nicely on the upper arm of a boy was far too small for the thick, stumpy foreleg of a dragon. It had sunk deeply into his scaly flesh and there was a throbbing bulge on each side of it. He tore at the place with his dragon’s teeth but could not get it off.

It’s an unforgettable evocation of horror, self-loathing and the sensation of being trapped inside oneself. Behave like a dragon, and you’ll become one; you are what you do. It’s the obverse of Socrates’ ‘Be what you wish to seem.’ (All in Plato, it’s all in Plato…) Eustace’s priorities are about to be rearranged, and his first need is to communicate, even with dragon claws and muscles that can barely write:

I WNET TO SLEE … RGOS AGRONS I MEAN DRANGONS CAVE CAUSE IT WAS DEAD AND AINING SO HAR … WOKE UP AND COU … GET OFFF MI ARM OH BOTHER …

It takes Aslan to strip off the horny layers of dragon hide from which Eustace will emerge reborn, and CS Lewis summarises the pain, difficulty and satisfaction of the healing process in a brilliant metaphor any child can recognise: picking off a scab. ‘It hurts like billy-oh, but it is such fun to see it coming away.’

TVDT isn’t Eustace’s story alone, though. This is made clear in the next chapter, ‘Two narrow escapes’. So much happens in this book, I’d forgotten about the sea-serpent which almost crushes the ship to matchwood and then goes sniffing along its own body looking for wreckage with an expression of ‘idiotic satisfaction’ on its face. A purely physical danger, it’s a good contrast to the spiritual sickness embodied in the dragon. But a far graver peril awaits them at the next island.

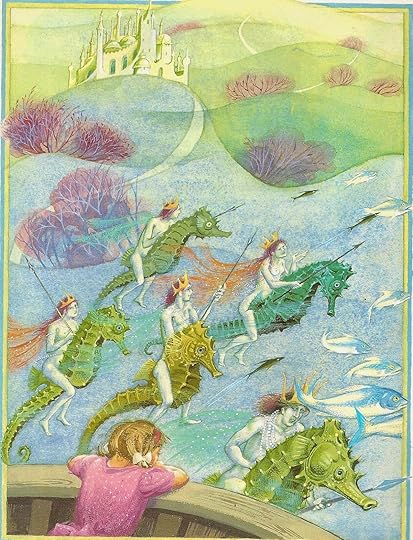

The bottom of the pool was made of large greyish-blue stones, and the water was perfectly clear, and on the bottom lay a life-size figure of a man, made apparently of gold. It lay face downwards with its arms stretched above its head. …Lucy thought it was the most beautiful statue she had ever seen.

But this water turns everything it touches to gold, and what seemed a statue is really a horror: the body of one of the seven lords they have come to seek. Only by chance have the children escaped the same fate. But there’s a worse danger.

‘The King who owned this island,’ said Caspian slowly, and his face flushed as he spoke, ‘would soon be the richest of all the Kings of the world. I claim this land forever as a Narnian possession. It shall be called Goldwater Island. And I bind all of you to secrecy. No one must know of this. Not even Drinian – on pain of death, do you hear?’

‘On pain of death’? It’s clear that Eustace is not the only one vulnerable to greed. Caspian is a King, and what do Kings do but acquire lands and power? In this passage he reveals a high-handed, bullying side to his character which suggests he could go either way – just ruler or cruel despot.

When Caspian threatens his friends for the sake of wealth and power, we see the story focussing on intangible, internal adventures more than on physical ones. Yes, there’s always plenty of action and excitement, but as with Frodo Baggins and the Ring, the real dangers are moral and spiritual. There may be squabbles and disagreements in other books, but this is the only one of the seven Narnia stories in which Lewis allows for the real possibility of ‘good’ characters changing for the worse. True, Aslan or his image steps in each time to avert real disaster, but the danger exists. Each of the main characters (save Edmund whose trial came in the first book) is put to the test. Like the knights on the Grail Quest, Caspian and even Lucy falter along the way, and only Reepicheep, Narnia’s Galahad, will succeed. For now, though, as Caspian and Edmund begin to quarrel and Lucy to scold, Aslan passes warningly along the hillside and recalls them to their senses.

When I was a child, the island-hopping voyage of Caspian and his friends to the End of the World seemed completely original, but I know now that C.S. Lewis was borrowing from the very old Irish voyage tales known as immrama, in each of which a hero or saint – Bran, Maelduin, Brendan – sets out for some kind of Otherworld, stopping at a number of fantastic or miraculous islands along the way. Written in the Christian era, they hark back to older pre-Christian Celtic voyage tales, and were probably themselves influenced by the classical tales of the Odyssey and Argonautika.

Saint Brendan, for example, puts out into the Atlantic Ocean in a hide boat – a curragh – with twelve companions. In search of Paradise, the Land of the Blessed, he spends years wandering the ocean from island to island: the island of the ‘Comely Hound’ which leads them to a hall with a table spread with food; the Island of Sheep, ‘every sheep the size of an ox’; ‘The Paradise of Birds’, on which some of the angels who fell with Lucifer live as small birds all rejoicing and singing the matins and the verses of the psalms.

The islands in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader – the dragon island, the Dark Island where dreams come true, the Island of the Dufflepuds, the island of The Three Sleepers – these are deliberate echoes of Brendan’s islands or those visited by the Irish hero Maeldune: thirty or so marvellous islands and other wonders, including this:

The Very Clear Sea

They went on after that till they came to a sea that was like glass, and so clear it was that the gravel and the sand of the sea could be seen through it, and they saw no beasts or monsters at all among the rocks, but only the clean gravel and the grey sand. And through a great part of the day they were going over that sea, and it is very grand it was and beautiful.

Saint Brendan too encounters a clear sea, while saying mass:

So clear that they could see to the bottom, and it was all as covered with a great heap of fishes. …And the fishes awoke and started up and came all around the ship in a heap, that they could hardly see the water for fishes. But when the mass was ended each one of them turned himself and swam away, and they saw them no more.

The clear water is repeated in C.S. Lewis’s ‘Silver Sea’:

'How beautifully clear the water is' said Lucy to herself as she leaned over the port side early in the afternoon...'I must be seeing the bottom of the sea; fathoms and fathoms down.'

Like the immrama, TVDT is the story of a spiritual quest. ‘Do you think,’ says Lucy, ‘Aslan’s country would be that sort of country – I mean, the sort you could ever sail to?’ The answer of the immrama is a qualified yes. Brendan and his companions reach the edges of their Blessed Land:

…clear and lightsome, and the trees full of fruit on every bough… and the air neither hot nor cold but always one way, and the delight that they found there could never be told. Then they came to a river that they could not cross but they could see beyond it the country that had no bounds to its beauty. Then there came to them a young man… and took [Brendan] by the hand and said to him…

‘Here is the country you have been in search of, but it is our Lord’s will you should go back again and make no delay… And this river you see here is the mering,’ he said, ‘that divides the worlds, for no man may come to the other side of it while he is in life; [and when he dies] it is then there will be leave to see this country towards the world’s end.’

Praising God and laden with fruit of the country and precious stones, Brendan returns to Ireland and dies, his whole mind set on the heaven he has already seen. In the same spirit, Reepicheep sails over the edge of the world in his coracle, ‘and since that moment no one can truly claim to have seen Reepicheep the Mouse. But my belief is that he came safe to Aslan’s country and is alive there to this day.’

No wonder Lewis wrote The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Reading these old tales, the writer in me longs to snatch up a pen and begin making one of my own. When the children catch a glimpse of Narnia’s own Land of the Blessed, Aslan’s country, over the top of the stationary wave at the world’s edge, Lewis recounts it in the same flat yet awed manner of the immrama – the voice of one simply reporting or recording genuine wonders.

Eastwards – beyond the sun – was a range of mountains. It was so high that either they never saw the top or they forgot it. None of them remembers seeing any sky in that direction. And the mountains must really have been outside the world. For any mountains even a quarter or a twentieth of that height ought to have had ice and snow on them. But these were warm and green and full of forests and waterfalls however high you looked. And suddenly there came a breeze from the east, tossing the top of the wave into foamy shapes and ruffling the smooth water all round them. …It brought a smell and a sound, a musical sound. Edmund and Eustace would never talk about it afterwards. Lucy could only say, ‘It would break your heart.’ ‘Why,’ said I, ‘was it so sad?’ ‘Sad!! No,’ said Lucy.

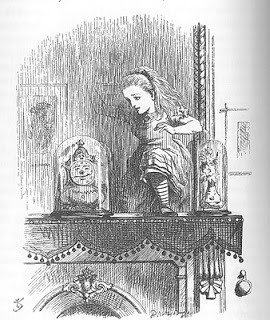

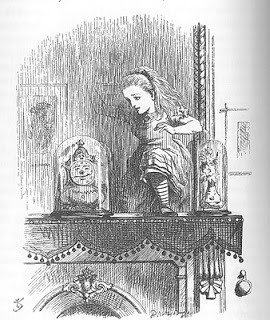

But I’m getting ahead of myself. After the adventure of Goldwater/Deathwater Island, the next landfall for the ship is the Island of the Voices – comic, if slightly sinister relief after the strain of the past few adventures. The invisible, thumping creatures whose voices (‘the isle is full of noises’) alarm Caspian and his friends turn out to be servants of a powerful and equally invisible magician, whose spell only ‘a little girl’ can undo. Alone, Lucy sets off upstairs into the quiet sunlit interior of the Magician’s House

… perhaps a bit too quiet. It would have been nicer if there had not been strange signs painted in scarlet on the doors – twisty, complicated things which obviously had a meaning and it mightn’t be a very nice meaning either.

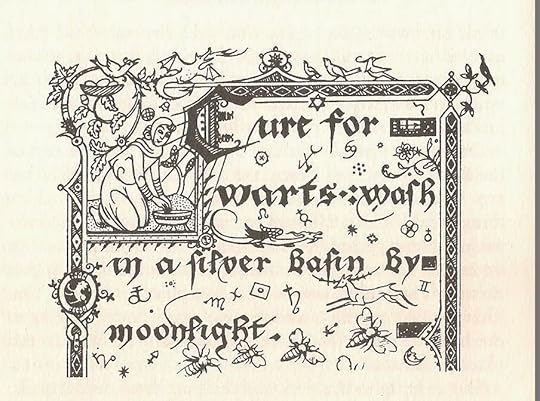

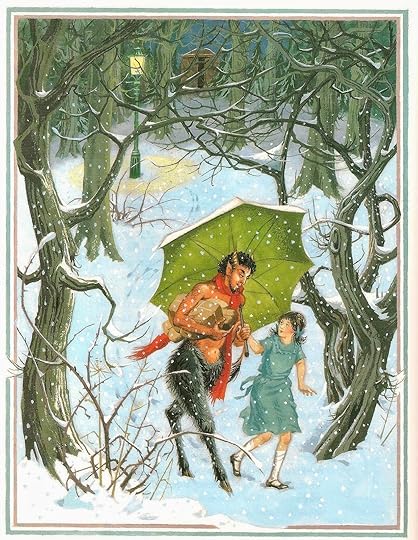

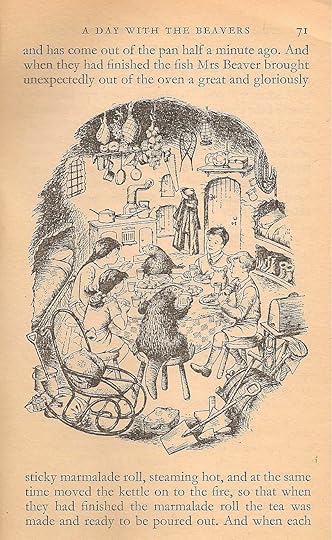

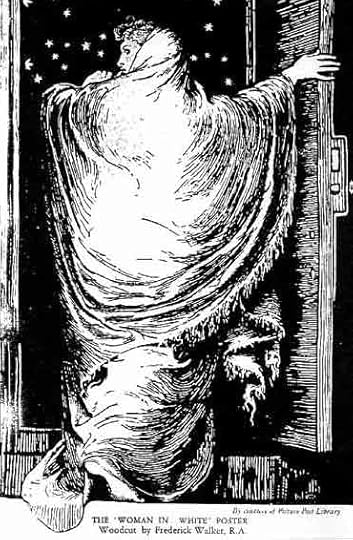

I’ve always loved this bit, rich and cosy and creepy – the silence, the masks, the strange Bearded Glass, and the Magician’s Book which you could only read if you turned your back on an open door. I loved the spells, too. Of course Lucy wants to try one – who wouldn’t? And Pauline Baynes’ gorgeous illustration only makes it all the more tempting.

An infallible spell to make beautiful her that uttereth it beyond the lot of mortals. Like Galadriel tempted by the Ring (‘All shall love me, and despair’) Lucy is tempted to speak the words which will transform her into another Helen, a cause of wars to lay Narnia and its neighbour countries waste. There’s also a strong dash of sibling rivalry: the magical book shows her Susan, ‘only plainer and with a nasty expression… jealous of the dazzling beauty of Lucy, but that didn’t matter a bit because no one cared anything about Susan now’. We knew Edmund was jealous of Peter, but Lewis has never told us before that Lucy is jealous of Susan (in reality it has to be that way around) and the effect here is both to humanise Lucy and demonise Susan even though we know it’s all Lucy’s fantasy.

‘I will say the spell,’ said Lucy. ‘I don’t care. I will.’

This book of spells is Lucy’s test and like Eustace-the-dragon and Caspian, she fails it. Once again Aslan has to intervene, his painted face appearing on the page ‘growling, and you could see most of his teeth’. Frightened, Lucy turns the page only to gabble another, lesser spell that ‘would let you know what your friends thought about you’, which teaches her the age-old lesson that listeners never hear good of themselves. Next comes a spell ‘for the refreshment of the spirit’, and finally the one she’s looking for, ‘A Spell to make hidden things visible’. On repeating it, Aslan himself appears,in tender but chiding mood – the Magician is revealed to be a sort of benign exiled Prospero, and we meet the Duffers or Monopods.

Lucy has succumbed to vanity and curiosity, which Lewis probably considered female faults. Unlike Susan, Lucy is forgiven them: the spell for ‘refreshment of the spirit’ with its Gospel hints of ‘a cup and a sword and a green hill’ seems to cleanse her.

Next comes the terrible Dark Island ‘where dreams – dreams, do you understand – come to life, come real. Not daydreams: dreams.’ More strong meat for my nine-year old self, who like most children knew plenty about the sorts of dreams ‘that make you afraid of going to sleep again’. Reading it as a child, I completely understood that the Dark Island is not a physical place at all; the ship never comes to land. All this terror and madness and horror is happening inside the minds of the crew. It’s fabulous writing. (‘Can you hear a noise … like … like a huge pair of scissors opening and shutting… over there?’) I understood that somehow, the characters have to escape from themselves – out of their own heads. The tension as they try to row out of the darkness… will they ever get out? Will anyone in the blackness of despair ever make it?

The stranger, who had been lying in a huddled heap on the deck, sat up and burst into a horrible screaming laugh. ‘Never get out!’ he yelled. ‘That’s it. Of course. We shall never get out. What a fool I was to have thought they would let me go as easily as that. No no, we shall never get out.’

But by Aslan’s help, they do. Is that too easy? I think not, because the emotion is true. The albatross which circles the ship crying in a ‘strong, sweet voice’ and which leads them back to the light may be Aslan, or Christ, or hope, or what you will, but Lewis knows help of some kind is necessary: there are few who can drag themselves out of depression unaided. The relief and joy of finding the sunlight once again is almost palpable.

More light follows this darkness at the ship’s next landfall, the Island of the Sleepers. Here the last three lost Narnian lords lie in an enchanted stupor, having touched the Stone Knife that lies on Aslan’s Table. Caspian and his company wait uneasily around the Table till dawn at the behest of Reepicheep the Mouse (‘no danger seems to me so great as that of knowing when I get back to Narnia that I left a mystery behind me though fear’) while strange constellations burn in the eastern sky. Here they meet Ramandu and his daughter, and see the birds flocking to the Table from the rising sun. From this point on, the story is all wonder and enchantment and Ramandu, the old star, hints they are on the edge of spiritual awakening or rebirth

‘Every morning a bird brings me a fire-berry from the valleys in the Sun, and each fire-berry takes away a little of my age. And when I have become as young as the child that was born yesterday, then I shall take my rising again (for we are at earth’s eastern rim) and once more tread the great dance.’

I haven’t yet said much about Reepicheep. He is truly Narnia’s Galahad, not its Lancelot. Lancelot is the Round Table’s best earthly knight, but he is fallible, he has passions and faults which make us love and admire him the more because we can see ourselves in him. Galahad is inhumanly virtuous, courteous and brave. TH White had some fun with him in The Once and Future King: looked at one way he’s a prig, it’s difficult to like him. Reepicheep is as virtuous, courteous and brave as Galahad, but he’s lovable simply because he isn’t human, but a gallant Talking Mouse about two feet high, with dark, almost black fur: ‘A thin band of gold passed around its head under one ear and over the other, and in this was stuck a long crimson feather.’ Reepicheep sets a high – almost too high – example to Caspian and his company. On Ramandu’s Island, Caspian’s crew begins to mutiny, longing for home like Alexander’s soldiers who refused to cross the Ganges.

‘Aren’t you going to say anything, Reep?’ whispered Lucy.

‘No. Why should your Majesty expect it?’ answered Reepicheep in a voice that most people heard. ‘My own plans are made. While I can, I sail east in the Dawn Treader. When she fails me, I paddle east in my coracle. When she sinks, I shall swim east with my four paws. And when I can swim no longer, if I have not reached Aslan’s country, or shot over the edge of the world in some vast cataract, I shall sink with my nose to the sunrise and Peepiceek will be head of the talking mice in Narnia.’

Perfection is inhuman. This is made clear when only Reepicheep is unmoved by the terror of the Dark Island. ‘There are some things no man can face,’ Caspian exclaims as he orders the retreat.

‘It is, then, my good fortune not to be a man,’ replied Reepicheep with a very stiff bow.

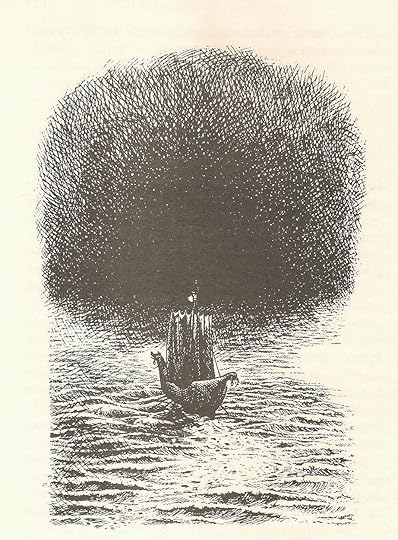

We can tolerate Reepicheep’s disapproval because he’s an animal. He doesn’t understand or share our fears. Nothing stands between him and the best. He is both less than us, and greater. When finally, ‘quivering with happiness’, he hurls his sword into the Silver Sea (like Arthur at the brink of Avalon) and sets off alone in the coracle, swooping up the green glassy breast of the wave to vanish forever over the crest, it still brings tears to my eyes.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is at an end. It is time for Caspian to turn back, even though he longs to go on. His last tantrum over, he accepts his duty and destiny to return to rule well and wisely over Narnia. For Edmund and Lucy, it is their last time here. Though they have come close, so close, to the fringes of Aslan’s country, like Caspian they must turn their faces towards their own world.

But we shall meet Eustace – and Caspian – again, in the next book.

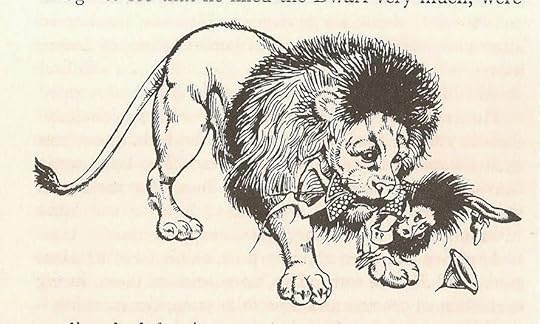

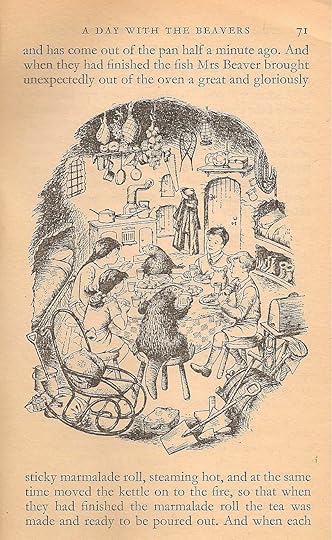

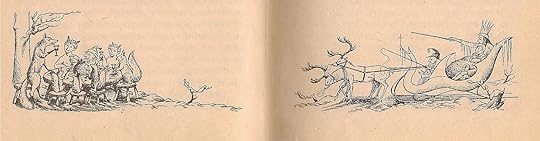

Picture credits:All artwork by the wonderful Pauline Baynes

Published on September 10, 2014 04:59

August 18, 2014

Re-reading Narnia: 'Prince Caspian'

Mad as I was about Narnia as a child, Prince Caspian was never my favourite among the Seven Chronicles, and the reason is as clear to me now as it was then, only then I put it differently: I just found the long fifty page back-story which tells the history of Caspian and Miraz – not dull, exactly, but certainly a distraction from where I really wanted to be, which was with Lucy and Peter and Susan and Edmund in the ruins of Cair Paravel. I still read it multiple times, of course - I'd have read the Narnian telephone directory, if such a thing had existed - but I felt it wasn't as good as some of the other books.

My eight or nine-year old self was correct. Prince Caspian is clumsily constructed. The first part is the best, in which the children are called back to Narnia and gradually realise that hundreds of Narnian years have passed since they were last there.

Often in writing, everything begins with an image and an emotion – a couple of things that come together like flint and iron, and strike the spark which kindles the book. I’ve got the feeling that in this book the spark of inspiration lasted Lewis through to about page 40, by which time he’d said everything he actually wanted to say. A book, however, has to be longer than that: so he had to work out a plot and people it with characters, and the story of Caspian’s childhood is reasonably entertaining, but it stops the narrative dead in its tracks for the whole middle part of the book. Then follows the children’s cross-country journey to Caspian’s aid - an unconvincing stratagem for a single combat between Peter and Miraz - a couple of treacherous Ruritanian-type lords thrown in for good measure - and Aslan at his worst: unfair, demanding and capricious. If Prince Caspian had been the only sequel to TLTW&TW, one would have to conclude that Lewis had lost his touch.

And yet it all begins so simply and so well, with the four children sitting despondently at the station waiting for the two trains which will separate them and send them away to school (‘Lucy was going to boarding school for the first time’) when –

Lucy gave a sharp little cry, like someone who has been stung by a wasp. ‘What’s up, Lu?’ said Edmund – and then suddenly broke off and made a noise like ‘Ow!’ ‘What on earth –’ began Peter, and then he too suddenly changed what he had been going to say. Instead he said, ‘Susan let go! What are you doing? Where are you dragging me to?’ ‘I’m not touching you,’ said Susan. ‘Someone is pulling me. Oh – oh – oh – stop it!’ Everyone noticed that all the others’ faces had gone very white. ‘I felt just the same,’ said Edmund in a breathless voice. ‘As if I were being dragged along. A most frightful pulling – ugh! it’s beginning again.’

So different is this magic summons from the easy transition through the wardrobe in the first book, I’m tempted to consider it a metaphor for the difficulty of writing a sequel. At any rate, it’s a brilliantly imagined and startling opening as the children are jerked out of England and – holding hands – find themselves ‘standing in a woody place – such a woody place that branches were sticking into them and there was hardly room to move.’

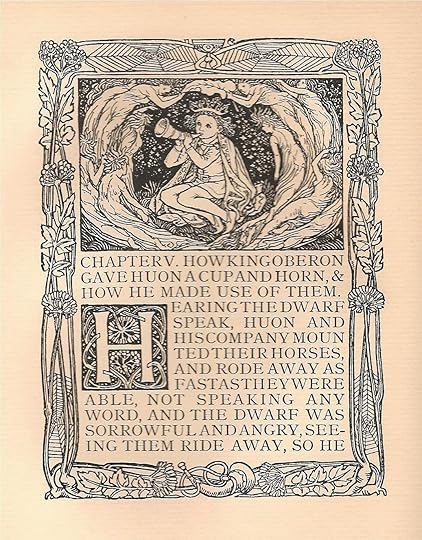

What the children (and the reader) don’t yet realise is that they’ve been called into Narnia by Caspian blowing on Queen Susan’s magic horn. How Lewis resisted the temptation to have the children actually hearthe note of a far-away faerie horn – ‘with dim cri and blowing’, as in the medieval romance Sir Orfeo - I just don’t know: but he was right. He fixes instead on the unpleasant physical sensations of being tugged, jerked, dragged out of one world and into another, and unceremoniously deposited in a highly inconvenient place.From Roland's to Boromir's, there are many wondrous horns in fantasy literature, but it seems to me that Susan’s horn is a version of the horn of Oberon in the late medieval romance ‘Huon of Bordeaux’, which Lewis knew well. In that tale (translated from the French by the Lord Berners who was Henry VIII’s Governor of Calais), the knight Huon, journeying to Jerusalem, meets the fairy king, Oberon, in a magic wood:

…the dwarf of the fairies, King Oberon, came riding by, wearing a gown so rich that it were marvel to recount… and garnished with precious stones whose clearness shone like the sun. He had a goodly bow in his hand, and his arrows after the same sort, and these had such a property that they could hit any beast in the world. Moreover, he had about his neck a rich horn, hung by two laces of gold… and whosoever heard it, if he were a hundred days journey thereof, should come at the pleasure of him that blew it.

Perhaps Susan's bow and arrows come from the same source. Characteristically inventive, Lewis shows us, not how it feels to blow such a horn, but what it’s like to be summoned by one ‘at the pleasure of him that blew it’. As the children remark, when a magician in the Arabian Nights calls up a Jinn, the Jinn has to come.

‘And now we know what it feels like for the Jinn,’ said Edmund with a chuckle. ‘Golly! It’s a bit uncomfortable to know that we can be whistled for like that.’

‘We’: original italics. Does Edmund mean ‘we public-school English children’, or ‘we kings and queens of Narnia’? In either case, the word speaks of privilege… these children have a strong sense of their own position in the world. But I like the way Lewis borrows the conventions of fairytales and medieval fantasy while turning around to look at them from the other side, so to speak: there's more of this to come.

Within a few minutes the children struggle out of the trees and find themselves

…at the edge of a wood, looking down on a sandy beach. A few yards away a very calm sea was falling on the sand with such tiny ripples that it made hardly any sound. There was no land in sight and no clouds in the sky. The sun was about where it ought to be at ten o’ clock in the morning, and the sea was a dazzling blue. They stood sniffing in the sea-smell. ‘By Jove!’ said Peter. ‘This is good enough.’

Of course, this is Narnia.

To begin with they behave like the children they are, paddling and enjoying the unexpected treat – ‘better than being in a stuffy train on the way back to Latin and French and Algebra!’ – but soon become hot, thirsty and hungry. Then they discover they are on an island, and the narrative swerves briefly into ‘shipwrecked sailor’ mode, Lewis poking a little light fun at ‘Boys’ Own’ type adventures:

Lucy wanted to go back to the sea and catch shrimps, until someone pointed out that they had no nets. Edmund said they must gather gulls’ eggs from the rocks, but when they came to think of it they couldn’t remember having seen any gulls’ eggs and wouldn’t be able to cook them if they found any. …Susan said it was a pity they had eaten the sandwiches so soon. One or two tempers very nearly got lost at this stage. Finally Edmund said,‘Look here. There’s only one thing to be done. We must explore the wood. Hermits and knight-errants and people like that always manage to live somehow if they’re in a forest. They find roots and berries and things.’‘What sort of roots?’ asked Susan.‘I always thought it meant roots of trees,’ said Lucy.

At this point the children's responses are very much derived from the books they've read, but the reference to hermits and knight-errants heralds a change of tone and the discovery of the ruined castle, along with memories of the chivalric past in which the children themselves once lived. At the end of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Lewis compressed a couple of decades of the children’s adult Narnian lives into a couple of faux-heroic pages:

Then said King Peter (for they talked in quite a different style now, having been Kings and Queens for so long), ‘Fair Consorts, let us now alight from our horses and follow this beast into the thicket, for in all my days I never hunted a nobler quarry.’ ‘Sir,’ said the others, ‘even so let us do.’

In this passage it was Queen Susan who didn’t want to follow the White Stag beyond the lamp-post – ‘By my counsel we shall lightly return to our horses and follow this White Stag no further’. When I was a child I had a good deal of sympathy for her point of view: if they’d done as she suggested, they’d all have stayed in Narnia, so she was right, wasn’t she? Looking at that passage now, I see the beginning of a characterisation of Susan which continues into this book too: Susan is gallant enough, and a skilled archer, but she is also cautious, and consistently reluctant to face challenges. This isn’t about ‘being a girl’: Lucy, and in later books Jill and Polly and Aravis are evidence for Lewis’s equal treatment of the sexes. It’s just the way Susan is: and also something to do with the dynamic of keeping four main characters ‘alive’ and distinguishable from one another. In fact Peter is the most boring of the lot: he never deviates an inch from decent, fair-minded, head-boy, big-brotherhood. If Susan is practical and sharp – unfair sometimes, sometimes a bit of a nag – at least she breathes.

And now the children find themselves here: in an ancient apple orchard, looking at an old stone wall, and it is Susan’s turn to make discoveries. ‘This wasn’t a garden,’ she says. ‘It was a castle and this must have been its courtyard.’ And,

‘It gives me a queer feeling,’ said Lucy.

As well it might. This quiet ruin is the emotional heart of the book, and the discovery the children are about to make is – I believe – the point of the entire story; the rest is just window-dressing.

It’s beautifully done. The ‘yellowish-golden’ apples on the ancient trees come with memories of the Hesperides, the secret garden, Eden – anywhere long-loved and lost. Because when the children do finally realise where they are the realisation is laden with melancholy: this is Cair Paravel, but not as it was: their Cair Paravel is gone for ever.

Still unaware, the children make camp. Susan goes to the well for a drink, and returns with something in her hand:

‘Look,’ she said in a rather choking kind of voice. ‘I found it by the well.’ She handed it to Peter and sat down. The others thought she looked and sounded as though she might be going to cry.

… ‘Well I’m – I’m jiggered,’ said Peter, and his voice also sounded queer. Then he handed it to the others. All now saw what it was – a little chess-knight, ordinary in size but extraordinarily heavy because it was made of pure gold; and the eyes in the horse’s head were two tiny little rubies – or rather one was, for the other had been knocked out.

‘Why,’ said Lucy, ‘it’s exactly like one of the golden chessmen we used to play with when we were Kings and Queens at Cair Paravel.’

In the Icelandic poem ‘The Deluding of Gylfi’, the tale is told of the end of the Norse Gods, the Aesir, at the day of Ragnarok: after which a new earth will rise out of the sea, fresh and green. Baldur will return from death, and the sons of the gods ‘will all sit down together and converse, calling to mind their hidden lore and talking about things that happened in the past… Then they will find there in the grass the golden chessmen the Aesir used to play with…’

Susan is crying because of the memories the little chess piece has brought back. ‘I can’t help it. It brought back – oh, such lovely times. And I remembered playing chess with fauns and good giants, and the mer-people singing in the sea, and my beautiful horse, and – and –’

And now Peter ‘uses his brains’ and declares that, impossible as it may seem, ‘We are in the ruins of Cair Paravel itself.’ Hundred of years must have passed in Narnia, and the four children are in the position of long-lost heroes who return to find only traces of themselves in a world which has almost forgotten them. The revelation is confirmed when they uncover the old treasury of Cair Paravel.

There are many folktales and legends in which people step into fairy rings, or disappear into a fairy kingdom for what seems a few hours, and return to find that a hundred or more years have passed, and no one now remembers them. Lewis would have been familiar with the 12th century story of King Herla, invited to a wedding by a goat-footed pygmy king who ruled underground halls of unutterable splendour. After the celebrations, the fairy king escorted Herla out of his kingdom -

…and then presented the king with a small blood-hound to carry, strictly enjoining him that on no account must any of his train dismount until that dog leapt from the arms of his bearer… Within a short space Herla arrived once more at the light of the sun and at his kingdom, where he accosted an old shepherd and asked for news of his Queen, naming her. The shepherd gazed at him in astonishment and said: ‘Sir, I can hardly understand your speech, for you are a Briton and I a Saxon, but they say… that long ago, there was a Queen of that name over the very ancient Britons, who was the wife of King Herla; and he, the story says, disappeared in company with a pigmy at this very cliff, and was never seen on earth again…’

In Prince Caspian Lewis has reversed the tradition, so that while in England only a year has passed, in Narnia hundreds or maybe a thousand years have sped by. It’s as if England is a fairyland, less real than Narnia. I’m sure Lewis was thinking of the story of Herla, because once the children realise what’s happened, Peter exclaims, ‘…And now we’re coming back to Narnia just as if we were Crusaders or Anglo-Saxons or Ancient Britons or someone coming back to modern England!’ ‘How excited they’ll be to see us –’ Lucy begins optimistically – and is interrupted by the sight of a boat rowed by armed men who have come to execute Trumpkin the dwarf by drowning.

The book never again reaches the emotional depth of these passages, in which a children’s magical adventure story unfolds into a poignant consideration of the mysteries of loss and time. Tell me where all past things are? Where beth they beforen us weren? Ou sont les neiges d’antan? Children do ask profound questions about life, the universe and everything, and adults are frequently stumped. I remember asking my mother, ‘What would there be if there was nothing?’ and she couldn’t give a satisfactory answer. The Narnia stories were my introduction to a good many metaphysical thought-experiments. What if time is relative and runs at different speeds in different places? What if there are multiple universes? What if something could be larger on the inside than on the outside? It was exhilarating.

CS Lewis throws into the first forty pages of Prince Caspian his own experience of sehnsucht, of longing for something unattainable. Childhood? A mother’s love? Security? Peace?

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highroads where I went

And cannot come again.

For me the rest of the book is an anti-climax. Trumpkin – or Lewis – interrupts the narrative with the history of Prince Caspian, a child version of Hamlet whose throne has been usurped by his wicked uncle Miraz, under whose alien Telmarine rule the magic of Narnia has been suppressed. It’s difficult to feel enthusiastic about Caspian – he doesn’t come alive until the next book. I tapped my foot through the story as a child, and I’m still impatient with it now, and with names like Queen Prunaprismia, and academic jokes aimed above children's heads, such as Caspian's grammar book written by one Pulverentulus Siccus, for goodness sake. With the help of the badger Trufflehunter, the trusty Red Dwarf Trumpkin and the untrustworthy Black Dwarf Nikabrik, Caspian escapes to lead the forces of the native Narnians, but finding his rebellion in trouble, blows on Susan’s horn for aid…

Bad Black Dwarves. I was always rather sorry for Nikabrik, bound for a bad end after trying to enrol a Hag and a Wer-wolf to Caspian’s cause. In fairytales and myths the colour black represents night and death – and by extension, evil. In the real world, I don’t need to say, the ‘white = good, black = bad’ equation has caused a great deal of trouble. Narnia isn’t the real world but a fairytale, so perhaps it’s unfair to vilify Lewis for employing the symbolism of fairytales. I merely note it’s a shame that all Black Dwarfs seem to be dodgy customers – as though hair-and-beard-colour determined your character.

Who are the usurping Telmarines? They come from a country named Telmar, beyond the Western Mountains, though it never appears on any of the maps drawn by Pauline Baynes. Prior to that they came from our human world – or Caspian would have no legitimate claim to the throne of Narnia, which by Aslan’s command must be ruled by a Son of Adam or a Daughter of Eve. This is of course a reflection of Genesis, in which Adam is given rule over the birds of the air and beasts of the field. So… how has Telmarine rule gone wrong?

‘It is… the country of the Waking Trees and Visible Naiads, of Fauns and Satyrs, of Dwarfs and Giants, of the gods and the Centaurs, of Talking Beasts. It was you Telmarines who silenced the beasts and the trees and the fountains, and who killed and drove away the Dwarfs and the Fauns, and are now trying to cover up even the memory of them,’ (says Doctor Cornelius to Caspian).

For Telmarines, read – who? What is Lewis trying to say? Who or what was it in our world which did its best to drive out belief in and cover up the memory of fauns, satyrs, the spirits of trees and fountains? The Church? The Puritans? The Education System? Is this a plea for freedom of imagination? I don’t quite know what’s going on, but it seems to be a muddled but sincere claim for the vital importance of myths and stories. Or – possibly and more controversially – for belief itself. At any rate, Narnia without its magic is a poor place.

When Aslan finally does turn up, he reveals himself at first only to Lucy, and there’s a reprise of TLTW&TW in which this time Edmund believes her, and Peter and Susan do not. Aslan is much less loveable, much more manipulative, in this book. He puts people to the test. He terrifies Trumpkin by seizing and shaking him – even though the children know that ‘Aslan liked the Dwarf very much.’ (And this is how to reward him?) He refuses to heal Reepicheep’s lopped-off tail until the other mice prepare to cut their own tails off in solidarity with their brave leader. You can see the difference most clearly in the bacchanal, Aslan's Romp with Bacchus and the wild girls, which so closely resembles Aslan's joyful gallop with Lucy and Susan through the springtime Narnian woods, in the previous book. But what in TLTW&TW was sheer delight, culminating in the release of the Witch's stone prisoners, in Prince Caspian becomes vengeful and aggressive. Aslan frightens a group of schoolgirls and their teacher:

Miss Prizzle… clutched at her desk to steady herself and found that the desk was a rosebush. Wild people such as she had never even imagined were crowding round her. Then she saw the Lion, screamed and fled, and with her fled her class, who were mostly dumpy, prim little girls with fat legs. Gwendolen hesitated.

One is led to assume – by disassociation – that by contrast to the fat legged, dumpy girls, Gwendolen is slender and pretty. And therefore good, brave, open-minded? Guilty of fat legs or not, Gwendolen joins in Aslan’s bacchanal. This passage has not stood the test of time very well, and neither has its companion piece a page later, in which Aslan terrifies a classroom of boys who jump out of the window and are turned into pigs: shades of the Gadarene Swine? We are meant to understand that this is all right because the boys had been persecuting their young teacher whom Aslan welcomes and addresses as ‘Dear Heart’ – but the general air of ‘it serves ‘em all right’ leaves a bad taste in the mouth. Prejudices run rife. No allowances are made. There is no quarter.

Finally, why have Peter and Susan, Edmund and Lucy been brought to Narnia at all? What is their narrative function? Not one of them really affects anything. Peter’s challenge to Miraz is ultimately a failure, ending in the very wholesale battle he had hoped to avoid. Only Aslan’s intervention with the trees, in a scene reminiscent of the march of the Ents in The Lord of the Rings, saves the day for the native Narnians: and one assumes Aslan could have roused the trees any time he liked. Susan and Lucy literally go along for the ride. Prince Caspian seems to me to have been hastily and carelessly written, with very little of the love and attention that is evident in the first book.

There are moments. I love the scene in which Lucy almost calls the trees awake, dancing through the moonlit wood. I love the descriptions of the rich loamy earth which the trees eat at the great banquet after the victory. And of course I love the first meeting with one of Narnia’s great characters, the chivalrous and martial mouse, Reepicheep. All in all, however, this is a book to be read for the sake of the first few chapters.

Things look up – a long way up – in the next title, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. But that is a post for next time.

Published on August 18, 2014 02:16

August 4, 2014

Re-reading Narnia: 'The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe'

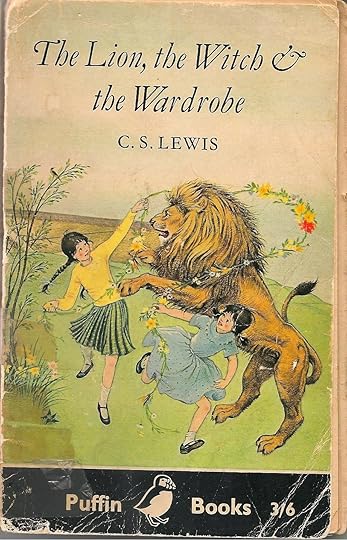

Here is my much-worn, much-loved childhood copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

I was given my first Narnia book, The Silver Chair, when I was seven years old – a little girl living in Yorkshire in the 1960s. I went on to read the series out of sequence, ending with The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: it depended on what I could buy with my pocket money or find in the public library. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was published in 1950, The Last Battle in 1956, the year of my birth: so I suppose I was among the first generation of child readers of these tales.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect the Narnia stories had on me. I adored them, I was super-possessive about them. I regarded Narnia as my own, private, secret kingdom – so much so that when my mother, who read aloud each night to me and my brother, suggested she might read us The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe, I vetoed the suggestion. Narnia was mine; I wanted to keep it all to myself. It was horribly selfish, but that was how passionate I felt. I read and reread them for years.

It’s decades now, though, since I sat down and read all of them through. Did the charm fade? I don’t know. The books were so much a part of my childhood that they still feel to be a part of me. So I’ve decided to begin again, to remind myself of what enchanted me and discover if it still has the power to do so. Over the next few months, I’ll be reading the Seven Chronicles of Narnia and letting you know my thoughts. Don’t expect academic crispness. These are likely to be long rambling posts with lots of digressions and asides as I follow wherever the fancy takes me. I hope you’ll tell me your own thoughts along the way.

So here goes: let’s talk about Narnia.

The first thing that strikes me now about The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is how short it is: 170 pages, many with full, half, or quarter page illustrations by Pauline Baynes. I’d guess the length is not more than 35,000 words – about right for a book for seven-year olds; but books for seven year olds written today do not commonly explore such rich emotional depths when dealing – if they deal at all – with subjects such as death, rebirth, police states, loyalty and treachery.

TLTW&TW is described by CS Lewis, in his dedication to his god-daughter Lucy Barfield, as a fairytale. Like a fairytale it deals in images, in strong, simple emotions, in primary colours, in poetic metaphor: and like a fairytale, it demands suspension of disbelief and a willingness to go along with the narrator.

Es war einmal ein König– There was once a King –

There were once four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy.

It doesn’t matter where or when a fairytale takes place, so Lewis disposes of the Blitz – the reason the children are sent away from London – in half a sentence. What they leave behind doesn’t matter. What matters is where they arrive: this house ‘in the heart of the country’. Which country? We aren’t told. It could be Scotland rather than England: the housekeeper has a Scottish name, and the children talk excitedly of mountains, woods, eagles and stags: but it’s the seclusion that matters. This is a secret and special place, and the further in you go, the more secret and more special it gets: inside the house there is a room, inside the room there is a wardrobe, inside the wardrobe there is Narnia…

Old houses and old castles are important places in fairytales, and there is often, too, a special hidden room. In The Twelve Dancing Princesses, the soldier must follow the princesses through an opening under the bed:

The eldest went to her bed and tapped it; whereupon it immediately sank into the earth, and one after another they descended through the opening…

and down a stair to a fabulous land where the trees have leaves of silver, gold and diamond, and where twelve princes row the princesses across a lake to a beautiful palace, to dance all night till dawn. This land is neither good nor bad (though one senses it is disapproved) but magical: other. Alternatively, as in Bluebeard or in the English folktale Mr Fox, the secret of the hidden room may be horror and death. Narnia will turn out to contain both beauty and terror.

So when Lewis chose a homely wardrobe for his doorway to Narnia (we all had wardrobes in our bedrooms back then, before the days of fitted cupboards) he was employing a device common in fairytales, where the domestic and ordinary frequently reveals the magical and the unexpected.

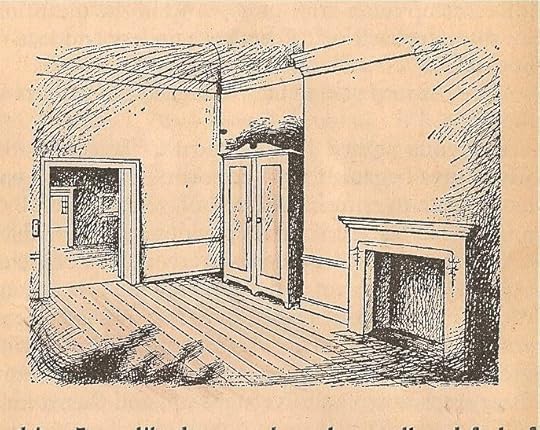

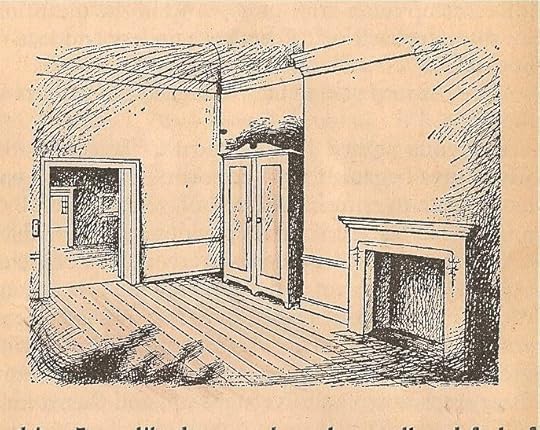

Here is the wardrobe – ‘the sort with looking-glass in the door’ – standing alone in an empty room. ‘Nothing there’, says Peter. But Lucy investigates. ‘This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!’ she thinks, pushing her way further in through the fur coats. And next:

Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

A word about Lucy. Philip Pullman has accused the Narnia books of being – among other bad things – sexist, of delivering the message ‘Boys are better than girls’. People who agree with this tend, I suspect, to be thinking of ‘the problem of Susan.’ But I was a little girl reading the Narnia books, and I was never in any doubt that the main character, the clear heroine of the three titles in which she takes a prominent part, is Lucy. Any child, boys included, reading TLTW&TW will identify with Lucy for the simple reason that it’s so unfair when her siblings don’t believe her about Narnia – and even more unfair when Edmund actually lies about it. It’s as easy to identify with Lucy as it is to identify with Jane Eyre, and for the same reason: children hate injustice.

Lucy’s main-character status has always been so obvious to me, I’m puzzled why Philip Pullman has failed to spot it. Is she too gentle for him? She may not be Lyra, or even Dido Twite, but the Narnia books were written for and about children, not teenagers - and quite young children at that. Judging by the games they play and the way they squabble, Lucy, the youngest of the Pevensies, is probably about seven years old in TLTW&TW – the same age as me when I first read it. This would make Edmund eight or nine, Susan perhaps ten and Peter between eleven and twelve. Seven year olds – of whatever sex – don’t tend to be feisty, kick-ass action heroes. Lucy is sensitive, courageous, honest and steadfast, and Lewis clearly cares for her far more than he does for any of the boys. Peter and Susan are ciphers in the way older children often are in family stories of the era. Like John and Susan in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, their main role seems to be that of surrogate parents to younger, livelier, more irresponsible siblings. Edmund is a very ordinary little boy whose silliness, jealousy and deceit are realistically sketched. Most children have occasionally behaved and felt like Edmund. But Lucy stands out. It is she who discovers Narnia, she who befriends the faun, Mr Tumnus. (And it’s Lucy and Susan, not the boys, who witness Aslan’s death and return to life: but more on the religious front later.)

Like Snow White, Lucy is quickly befriended by a denizen of the forest. And as in the seven dwarfs’ cottage, the cosy safety of Mr Tumnus’ house is soon compromised by the power of a dangerous queen. More terrifying still, Tumnus confesses himself to be a deceiver, an informer: ‘I’ve pretended to be your friend and asked you to tea, and all the time I’ve been meaning to wait till you were asleep and then go and tell Her.’ Because, and remember these books were written during the Cold War, Narnia is quite literally a police state.

‘We must go as quietly as we can,’ said Mr Tumnus. ‘The whole wood is full of her spies. Even some of the trees are on her side.’

Ashamed of himself, Tumnus is not now going to hand Lucy over to the White Witch, though this will put him at serious risk of torture and death –

‘…she’s sure to find out. And she’ll have my tail cut off, and my horns sawn off, and my beard plucked out, and she’ll wave her wand over my beautiful cloven hoofs and turn them into horrid solid hoofs like a wretched horse’s. And if she is extra and specially angry, she’ll turn me into stone and I shall be only a statue of a Faun in her horrible house until the four thrones at Cair Paravel are filled – and goodness knows when that will happen, or whether it will ever happen at all.’

This is strong stuff for young children – strong stuff for anyone. I think the reason why, in my experience at least, children aren’t very upset by it, is that they feel safe in the hands of the narrator. Lewis never forgets who he is writing for. The potential terror of Lucy’s predicament is modified by Tumnus’ repentance. The danger to her, once recognised, is already over. And for Tumnus himself, well – the danger is real enough, but this is clearly the kind of story in which good characters will, ultimately, be all right.

Children are sensitive to narrative voice, both as readers and auditors. A parent reading aloud to a child can offer reassurance at scary moments. Lewis-as-narrator offers reassurance partly by interposing himself between the child-reader and the text – commenting upon it or explaining it, thus keeping frightening or sad material at a safe distance; as in this passage from the chapter after Aslan’s death:

I hope no one who reads this book has been quite as miserable as Susan and Lucy were that night; but if you have been – if you’ve been up all night and cried till you have no more tears left in you – you will know that there comes in the end a sort of quietness. You feel as if nothing were ever going to happen again.

Is this condescension? I don’t think so. As a child, I never felt Lewis talked down to me, I felt he spoke as an equal, that he treated me seriously. He acknowledges the depth of children’s emotional experience, misery as well as happiness. By addressing the child reader directly, he turns Susan and Lucy’s grief into something we can share and understand, and the moment of Aslan’s death is thus softened and becomes more bearable.

The other method by which Lewis gently defuses fear or terror is a deft use of comedy – for example when the children and the Beavers bustle to get away from the White Witch.

‘…The moment that Edmund tells her that we’re all here she'll set out to catch us this very night, and if he’s been gone about half an hour, she’ll be here in about another twenty minutes.’

‘You’re right, Mrs Beaver,’ said her husband, ‘we must all get away from here. There’s not a moment to lose.’

The tension is both heightened and comically undercut by Mrs Beaver’s insistence on the careful and extensive packing of ham, tea, sugar, bread and handkerchieves –

‘Oh do please come on,’ said Lucy. ‘Well I’m nearly ready now,’ answered Mrs Beaver at last… ‘I suppose the sewing machine’s too heavy to bring?’

Hurry, hurry! –the child reader thinks, yet at the same time is both amused (Mrs Beaver is being funny) and reassured (Mrs Beaver is a mother figure, and if she’s not scared, neither need we be).

If Lewis were not so skilful, this could and would be a deeply unsettling book. There’s Edmund’s treachery – to his own brother and sisters, no less. There’s the scene of the Faun’s cosy house in ruins –

The door had been wrenched off its hinges and broken to bits. …Snow had drifted in from the doorway and was mixed with something black, which turned out to be the charred sticks and ashes from the fire. Someone had apparently flung it about the room and then stamped it out. The crockery lay smashed on the floor and the picture of the Faun’s father had been slashed to shreds with a knife.

It’s no small achievement to be this frank, this clear about spite and violence and hate – confirmed by the denunciation on the door signed ‘MAUGRIM, Captain of the Secret Police’ – in a book for small children which most of us remember as full of magic and delight. There’s the threat to Edmund himself from the White Witch, who is ready to murder him. There’s the truly upsetting scene when the Witch turns to stone a happy little party of fauns and animals, for the crime of telling the truth. (This is also the moment at which Edmund feels compassion for the first time.)

‘What is the meaning of all this gluttony, this waste, this self-indulgence? Where did you get these things?’‘Please, your Majesty,’ said the Fox, ‘we were given them …’‘Who gave them to you?’ said the Witch.‘F-F-F-Father Christmas,’ stammered the Fox.‘What?’ roared the Witch… ‘…How dare you – but no. Say you have been lying and you shall even now be forgiven.’At that moment, one of the young squirrels lost its head completely. ‘He has – he has – he has!’ it squeaked, beating its little spoon on the table.

All this, before we’ve even got to the death of Aslan.

As is well known, JRR Tolkien didn’t get on with Narnia, and one of the things that annoyed him about the series was Lewis’s carefree – or slapdash, depending on your viewpoint – world-building, bundling together everything and anything he’d ever loved in myth, legend and fairytales. Thus Narnia has not only talking animals out of Beatrix Potter or The Wind in the Willows, it also has nymphs, naiads, dryads and river gods from classical mythology, and giants and dwarfs out of the Northern legends. It borrows Green Ladies from medieval romances, and mystical islands from Celtic voyage tales and, in this one first book, it has Father Christmas.

But when a writer has come up with a lovely phrase like ‘Always winter and never Christmas’, well what is he to do? I don’t mind this single meeting with Father Christmas in Narnia, although I do think Lewis was wise not to invite him back. He seems to me to echo the appearance of Grandfather Frost in Russian fairytales – the white-bearded old spirit of the snowy woods who just may, if you address him politely, give you gifts (rather than freezing you to death). Personally I find Father Christmas in Narnia easier to accept than Tolkien’s facetious reference to golf in The Hobbit, when Bilbo’s ancestor Bullroarer Took knocks off the head of the goblin king Golfimbul. ‘It sailed a hundred yards through the air and went down a rabbit hole, and in this way the battle was won and the game of golf invented at the same moment.’ Such self-conscious flippancy was one of the things that put me off The Hobbit as a child.

And now for the vexed question of religion.

People talk a lot nowadays about the Narnia stories as religious allegories. They really aren’t. Lewis wrote a textbook about medieval allegory – ‘The Allegory of Love’ – and knew what it was and what it wasn’t. There is Christian symbolism in the books, but that is not at all the same thing. And it went clean over my head as a child. Aged about ten, I remember saying shyly to my mother that ‘it almost feels as if Narnia is real’. (What I actually wanted to say was ‘I believe Narnia is real’ – because the alternative, that Narnia had no existence except between the pages of a book – was almost unbearable.) My mother didn’t spoil the book for me by telling me that Aslan is meant to be Christ. She just replied quietly, ‘I think you’re meant to feel that.’ And so the religious message in the books remained invisible to me – at least until The Last Battle more or less rubbed my face in it. Indeed, talking to some teenage Muslim girls a year or two ago, I got surprised looks when I mentioned the Christian elements in the Narnia stories. They hadn’t noticed, either. There is a difference, I think, between the ways in which children and adults read. Children are more immersed in a book – more trusting, more literal. They take what they read at face value. They don’t come up for air and think, as adults do, ‘Just what is this author trying to say?’

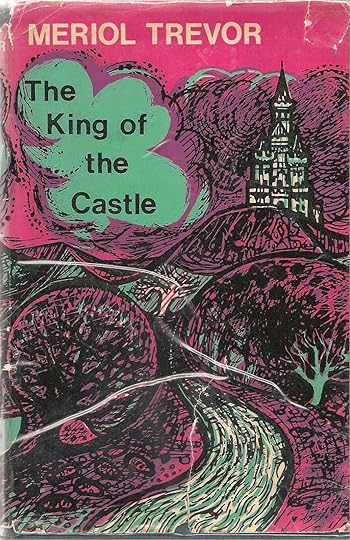

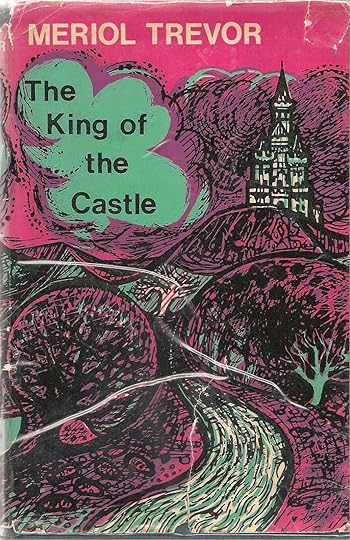

Does this make children potentially more vulnerable to prejudice and propaganda? Perhaps. But it’s interesting to look at a much more obvious attempt at Christian fantasy by the Catholic children’s author Meriol Trevor, written a decade after the Narnia books, in 1966. In The King of the Castle (Macmillan), a sick boy, Thomas, finds his way into the world of a picture hanging on his bedroom wall and meets Lucius, a shepherd with a phoenix ring, who believes himself to be the son of the High King. Reviled, disbelieved, eventually hanged, Lucius is restored to life by a Messenger of the High King, and claims his kingdom. The Christian message was obvious to me when I read the story as a child, but it didn’t capture my imagination, and a recent re-reading showed why: Lucius is wooden, the resurrection scene almost perfunctory, and there seems no narrative reason why the viewpoint character Thomas should be in this world at all. The book has nothing of the verve, the colour, the energy of the Narnia stories.

Philip Pullman speaks for many who consider the Narnia books outrageous propaganda for the pernicious doctrine of an all-powerful God who demands innocent blood to atone for the sins of a supposedly corrupt humanity. From this viewpoint TLTW&TW is dodgy stuff. For a Christian reader, however, such a view is a travesty of the New Testamant stories and the doctrine that declares Christ to be a facet of a living and loving God who shares in the suffering of the world. No one, least of all myself, is going to be able to reconcile such opposite perceptions.

But remember CS Lewis called his book a fairytale, and in fairytales the world over, good and innocent characters who die, come back to life. Think of Snow White in her glass coffin! In The Juniper Tree, the murdered boy is transformed into a beautiful, mysterious bird which deals out justice, rewarding the good and destroying the wicked, before turning back into a living child again. In Fitcher’s Bird, the third bride is able to restore her murdered sisters to life and escape the house of the sorcerer. Resurrections occur in fairytales because here, if nowhere else, there is a real chance that justice and goodness may prevail over evil and tragedy. Lewis came to Christianity through stories: he took them seriously: he regarded the incarnation, death and resurrection of Christ as a fairytale which really happened. We don’t have to follow him all the way. But we can still be moved by the tales.

It is perfectly natural for a child to read The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe and to see Aslan as no more and no less than the literal account makes him: a wonderful, golden-maned, heroic Animal. I know, because that’s the way I read it, and that is why I loved him. Though the death of Aslan at the hands of the White Witch is the heart of the book, that ‘deep magic from the dawn of time’ works just as well on a non-Christian level. A beautiful, icy queen: a golden lion. ‘When he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again…’ Of course Aslan comes back to life! Who can kill summer?

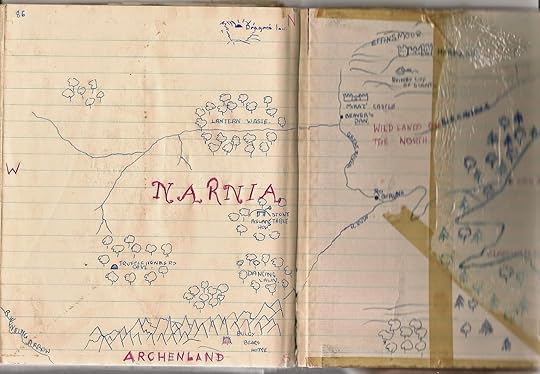

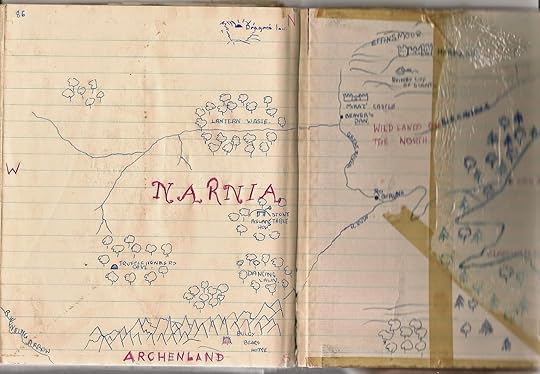

My childhood copy of the map of Narnia...

My childhood copy of the map of Narnia...Picture credits

All artwork by Pauline Baynes. The full colour illustration of Lucy and Mr Tumnus is from Brian Sibley's 'The Land of Narnia', Collins Lions, 1989

Published on August 04, 2014 03:12

'The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe': a re-reading

Here is my much-worn, much-loved childhood copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

I was given my first Narnia book, The Silver Chair, when I was seven years old – a little girl living in Yorkshire in the 1960s. I went on to read the series out of sequence, ending with The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: it depended on what I could buy with my pocket money or find in the public library. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was published in 1950, The Last Battle in 1956, the year of my birth: so I suppose I was among the first generation of child readers of these tales.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect the Narnia stories had on me. I adored them, I was super-possessive about them. I regarded Narnia as my own, private, secret kingdom – so much so that when my mother, who read aloud each night to me and my brother, suggested she might read us The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe, I vetoed the suggestion. Narnia was mine; I wanted to keep it all to myself. It was horribly selfish, but that was how passionate I felt. I read and reread them for years.

It’s decades now, though, since I sat down and read all of them through. Did the charm fade? I don’t know. The books were so much a part of my childhood that they still feel to be a part of me. So I’ve decided to begin again, to remind myself of what enchanted me and discover if it still has the power to do so. Over the next few months, I’ll be reading the Seven Chronicles of Narnia and letting you know my thoughts. Don’t expect academic crispness. These are likely to be long rambling posts with lots of digressions and asides as I follow wherever the fancy takes me. I hope you’ll tell me your own thoughts along the way.

So here goes: let’s talk about Narnia.

The first thing that strikes me now about The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is how short it is: 170 pages, many with full, half, or quarter page illustrations by Pauline Baynes. I’d guess the length is not more than 35,000 words – about right for a book for seven-year olds; but books for seven year olds written today do not commonly explore such rich emotional depths when dealing – if they deal at all – with subjects such as death, rebirth, police states, loyalty and treachery.

TLTW&TW is described by CS Lewis, in his dedication to his god-daughter Lucy Barfield, as a fairytale. Like a fairytale it deals in images, in strong, simple emotions, in primary colours, in poetic metaphor: and like a fairytale, it demands suspension of disbelief and a willingness to go along with the narrator.

Es war einmal ein König– There was once a King –

There were once four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy.

It doesn’t matter where or when a fairytale takes place, so Lewis disposes of the Blitz – the reason the children are sent away from London – in half a sentence. What they leave behind doesn’t matter. What matters is where they arrive: this house ‘in the heart of the country’. Which country? We aren’t told. It could be Scotland rather than England: the housekeeper has a Scottish name, and the children talk excitedly of mountains, woods, eagles and stags: but it’s the seclusion that matters. This is a secret and special place, and the further in you go, the more secret and more special it gets: inside the house there is a room, inside the room there is a wardrobe, inside the wardrobe there is Narnia…

Old houses and old castles are important places in fairytales, and there is often, too, a special hidden room. In The Twelve Dancing Princesses, the soldier must follow the princesses through an opening under the bed:

The eldest went to her bed and tapped it; whereupon it immediately sank into the earth, and one after another they descended through the opening…

and down a stair to a fabulous land where the trees have leaves of silver, gold and diamond, and where twelve princes row the princesses across a lake to a beautiful palace, to dance all night till dawn. This land is neither good nor bad (though one senses it is disapproved) but magical: other. Alternatively, as in Bluebeard or in the English folktale Mr Fox, the secret of the hidden room may be horror and death. Narnia will turn out to contain both beauty and terror.

So when Lewis chose a homely wardrobe for his doorway to Narnia (we all had wardrobes in our bedrooms back then, before the days of fitted cupboards) he was employing a device common in fairytales, where the domestic and ordinary frequently reveals the magical and the unexpected.

Here is the wardrobe – ‘the sort with looking-glass in the door’ – standing alone in an empty room. ‘Nothing there’, says Peter. But Lucy investigates. ‘This must be a simply enormous wardrobe!’ she thinks, pushing her way further in through the fur coats. And next:

Something cold and soft was falling on her. A moment later she found she was standing in the middle of a wood at night-time with snow under her feet and snowflakes falling through the air.

A word about Lucy. Philip Pullman has accused the Narnia books of being – among other bad things – sexist, of delivering the message ‘Boys are better than girls’. People who agree with this tend, I suspect, to be thinking of ‘the problem of Susan.’ But I was a little girl reading the Narnia books, and I was never in any doubt that the main character, the clear heroine of the three titles in which she takes a prominent part, is Lucy. Any child, boys included, reading TLTW&TW will identify with Lucy for the simple reason that it’s so unfair when her siblings don’t believe her about Narnia – and even more unfair when Edmund actually lies about it. It’s as easy to identify with Lucy as it is to identify with Jane Eyre, and for the same reason: children hate injustice.

Lucy’s main-character status has always been so obvious to me, I’m puzzled why Philip Pullman has failed to spot it. Is she too gentle for him? She may not be Lyra, or even Dido Twite, but the Narnia books were written for and about children, not teenagers - and quite young children at that. Judging by the games they play and the way they squabble, Lucy, the youngest of the Pevensies, is probably about seven years old in TLTW&TW – the same age as me when I first read it. This would make Edmund eight or nine, Susan perhaps ten and Peter between eleven and twelve. Seven year olds – of whatever sex – don’t tend to be feisty, kick-ass action heroes. Lucy is sensitive, courageous, honest and steadfast, and Lewis clearly cares for her far more than he does for any of the boys. Peter and Susan are ciphers in the way older children often are in family stories of the era. Like John and Susan in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, their main role seems to be that of surrogate parents to younger, livelier, more irresponsible siblings. Edmund is a very ordinary little boy whose silliness, jealousy and deceit are realistically sketched. Most children have occasionally behaved and felt like Edmund. But Lucy stands out. It is she who discovers Narnia, she who befriends the faun, Mr Tumnus. (And it’s Lucy and Susan, not the boys, who witness Aslan’s death and return to life: but more on the religious front later.)

Like Snow White, Lucy is quickly befriended by a denizen of the forest. And as in the seven dwarfs’ cottage, the cosy safety of Mr Tumnus’ house is soon compromised by the power of a dangerous queen. More terrifying still, Tumnus confesses himself to be a deceiver, an informer: ‘I’ve pretended to be your friend and asked you to tea, and all the time I’ve been meaning to wait till you were asleep and then go and tell Her.’ Because, and remember these books were written during the Cold War, Narnia is quite literally a police state.

‘We must go as quietly as we can,’ said Mr Tumnus. ‘The whole wood is full of her spies. Even some of the trees are on her side.’

Ashamed of himself, Tumnus is not now going to hand Lucy over to the White Witch, though this will put him at serious risk of torture and death –

‘…she’s sure to find out. And she’ll have my tail cut off, and my horns sawn off, and my beard plucked out, and she’ll wave her wand over my beautiful cloven hoofs and turn them into horrid solid hoofs like a wretched horse’s. And if she is extra and specially angry, she’ll turn me into stone and I shall be only a statue of a Faun in her horrible house until the four thrones at Cair Paravel are filled – and goodness knows when that will happen, or whether it will ever happen at all.’

This is strong stuff for young children – strong stuff for anyone. I think the reason why, in my experience at least, children aren’t very upset by it, is that they feel safe in the hands of the narrator. Lewis never forgets who he is writing for. The potential terror of Lucy’s predicament is modified by Tumnus’ repentance. The danger to her, once recognised, is already over. And for Tumnus himself, well – the danger is real enough, but this is clearly the kind of story in which good characters will, ultimately, be all right.

Children are sensitive to narrative voice, both as readers and auditors. A parent reading aloud to a child can offer reassurance at scary moments. Lewis-as-narrator offers reassurance partly by interposing himself between the child-reader and the text – commenting upon it or explaining it, thus keeping frightening or sad material at a safe distance; as in this passage from the chapter after Aslan’s death:

I hope no one who reads this book has been quite as miserable as Susan and Lucy were that night; but if you have been – if you’ve been up all night and cried till you have no more tears left in you – you will know that there comes in the end a sort of quietness. You feel as if nothing were ever going to happen again.

Is this condescension? I don’t think so. As a child, I never felt Lewis talked down to me, I felt he spoke as an equal, that he treated me seriously. He acknowledges the depth of children’s emotional experience, misery as well as happiness. By addressing the child reader directly, he turns Susan and Lucy’s grief into something we can share and understand, and the moment of Aslan’s death is thus softened and becomes more bearable.

The other method by which Lewis gently defuses fear or terror is a deft use of comedy – for example when the children and the Beavers bustle to get away from the White Witch.

‘…The moment that Edmund tells her that we’re all here she'll set out to catch us this very night, and if he’s been gone about half an hour, she’ll be here in about another twenty minutes.’

‘You’re right, Mrs Beaver,’ said her husband, ‘we must all get away from here. There’s not a moment to lose.’

The tension is both heightened and comically undercut by Mrs Beaver’s insistence on the careful and extensive packing of ham, tea, sugar, bread and handkerchieves –

‘Oh do please come on,’ said Lucy. ‘Well I’m nearly ready now,’ answered Mrs Beaver at last… ‘I suppose the sewing machine’s too heavy to bring?’

Hurry, hurry! –the child reader thinks, yet at the same time is both amused (Mrs Beaver is being funny) and reassured (Mrs Beaver is a mother figure, and if she’s not scared, neither need we be).

If Lewis were not so skilful, this could and would be a deeply unsettling book. There’s Edmund’s treachery – to his own brother and sisters, no less. There’s the scene of the Faun’s cosy house in ruins –

The door had been wrenched off its hinges and broken to bits. …Snow had drifted in from the doorway and was mixed with something black, which turned out to be the charred sticks and ashes from the fire. Someone had apparently flung it about the room and then stamped it out. The crockery lay smashed on the floor and the picture of the Faun’s father had been slashed to shreds with a knife.

It’s no small achievement to be this frank, this clear about spite and violence and hate – confirmed by the denunciation on the door signed ‘MAUGRIM, Captain of the Secret Police’ – in a book for small children which most of us remember as full of magic and delight. There’s the threat to Edmund himself from the White Witch, who is ready to murder him. There’s the truly upsetting scene when the Witch turns to stone a happy little party of fauns and animals, for the crime of telling the truth. (This is also the moment at which Edmund feels compassion for the first time.)