Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 19

December 8, 2016

He rode at night with gilten spur and candle light...

Following on from my last post about lists of fairies and bogeymen, I can't resist sharing a marvellous passage in a book published in 1549 called The Complaynt of Scotland. The main aim of the anonymous author was to challenge Henry VIII of England’s attempts to marry the young Mary Queen of Scots to his son Edward and thus unite the two countries (in other words, annexe Scotland). So The Complaynt is a political work, but in the sixteenth century this means backing up your points with a great many stories, legends and allegories which demonstrate Scotland’s superiority to, and independence from, England. In one chapter, a number of literate and thoughtful Scottish shepherds have been discussing philosophy, and one of them suggests they might all now relax and tell stories. There follows an exhilarating list which deserves to be better known: here’s a version in modern spelling:

Some were in prose and some in were in verse: some were stories and some were short tales. These were the names of them as after follows: the Tales of Canterbury, Robert the Devil Duke of Normandy, the tale of the wolf of the world’s end, Ferrand earl of Flanders that married the devil, the tale of the Red Ettin with the three heads, the tale how Perseus saved Andromeda from the cruel monster, the prophecy of Merlin, the tale of the giant that ate men alive, ‘On foot by forth as I could found’, Wallace, the Bruce, Hippomedon, the tale of the Three-Footed Dog of Norway, the tale how Hercules slew the serpent Hydra that had seven heads, the tale how the King of Eastmoreland married the king’s daughter of Westmoreland, Skail Gillenderson the king’s son of Skellye, the tale of the Four Sons of Aymon, the tale of the Bridge of the Mantribil, the tale of Sir Ywain, Arthur’s knight, Ralf Collier, the Siege of Milan, Gawain and Gollogras, Lancelot du Lac, Arthur knight he rode at night with gilten spur and candlelight, the tale of Floremond of Albany that slew the dragon by the sea, the tale of Sir Walter the bold Leslie, the tale of the Pure Tint, Clariades and Maliades, Arthur of Little Britanny, Robin Hood and Little John, the Marvels of Mandeville, the tale of the Young Tamlane and of the bold Braband, the reign of the Roi Robert, Sir Egeir and Sir Grim, Bevis of Southhampton, the Golden Targe, the Palace of Honour, the tale how Acteon was transformed into a hart and then slain by his own dogs, the tale of Pyramus and Thisbe, the tale of the amours of Leander and Hero, the tale how Jupiter transformed his dear love into a cow, the tale how that Jason won the Golden Fleece, Orpheus King of Portingal, the tale of the golden apple, the tale of the Three Weird Sisters, the tale how Daedalus made the Labyrinth to keep the monster Minotaur, the tale how King Midas got two asses lugs [ears] on his head because of his avarice.

How diverse these stories are! Scottish of course, with Wallace, the Bruce, Young Tamlane, the bold Leslie – classical, with Perseus and Andromeda, the Minotaur, Midas – French, with Arthur of Little Britain and Lancelot du lac – English: the Canterbury Tales, Bevis of Southhampton, Robin Hood, Mandeville’s Travels – and probably also Scandinavian, with the now unknown story of Skail Gillenderson. Many more are also now unknown. ‘The Three-Footed Dog of Norway’ for example, just might be a version of ‘The Black Bull of Norroway’, but we’ll never know. And ‘The Wolf at the World’s End’ sounds a little bit like ‘The Well at the World’s End’ – but then a well is very different from a wolf. John Leyden, who edited the Complaynt of Scotland in 1801, suggests the tale ‘of the Pure Tint’ may be ‘Rashycoat’, the Scots Cinderella – though he doesn’t say why. (Did he perhaps know a version in which the maiden’s fine complexion was a key to her identity?) ‘The tale of the Three Weird Sisters' is also unknown - though perhaps Shakespeare knew it! It may have been a story about the Fates or perhaps the Norns. For me the most haunting line is the one about Arthur. You really need to say it in the Scottish way to get the real lilt and the internal rhymes: ‘Arthour knycht he rade on nycht/With gyltin spur and candil lycht’. John Leyden says of it:

This romance, of which these lines seem to have formed the introduction, is unknown, but I have often heard them repeated in a nursery tale, of which I only recollect the following ridiculous verses:‘Chick my naggie, chick my naggie!How mony miles to Aberdeagie?Tis eight and eight, and other eight,We’ll no win there wi candle light.’

It’s a great pity this is all Leyden could remember of the tale, but it sounds very similar to the English nursery rhyme: How many miles to Babylon? Three-score miles and ten.Can I get there by candlelight?Yes, and back again: If your heels be nimble and light, You may get there by candlelight.’

So perhaps the story wasn’t so much a story as a lullaby? And aren’t lullabies often mysterious and a little sad? At any rate, this I love this candle-lit vision of Arthur flashing through the night with his golden spurs, possibly at the head of a ghostly troop like Herla or Herne. ‘Fire and fleet and candlelight…’

Picture credits

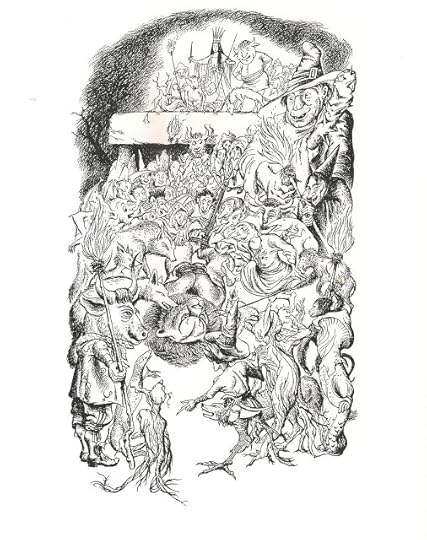

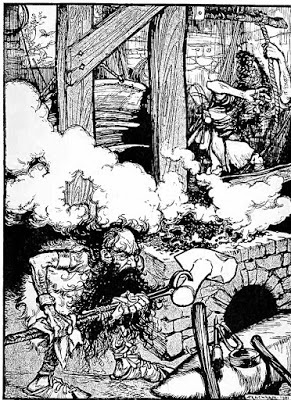

The Wild Hunt by Johann Wilhelm Cordes, Wikimedia Commons

Wild Hunt (engraving) Wikimedia Commons

Published on December 08, 2016 05:15

November 17, 2016

The 'man in the oke' and others

I love lists, especially lists of mysterious creatures like the oft-quoted one by Reginald Scot in his book debunking witches, The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), in which he takes the robust and sceptical line that even if witches, ghosts and fairies might exist, most actual instances are a load of old rubbish. ‘One knave in a white sheete hath cousened and abused many’ he declares; ‘Miracles are knaveries, most commonly’. In Chapter XV comes his famous, breathlessly delivered list of supernatural creatures fit to be believed in only by those who ‘through weaknesse of mind and bodie, are shaken with vain dreames and continuall feare’:

But in our childhood our mothers’ maids have so terrified us … with bull beggars, spirits, witches, urchens, elves, hags, fairies, satyrs, pans, faunes, sylens, Kit with the cansticke, tritons, centaurs, dwarfes, giants, imps, calcars, conjurors, nymphes, changelings, Incubus, Robin good-fellowe, the spoorne, the mare, the man in the oke, the hell waine, the fierdrake, the puckle, Tom thombe, hob gobblin, Tom tumbler, boneles, and such other bugs, that we are afraid of our owne shadows: in so much as some never fear the divell but on a darke night; and then a polled sheep is a perilous beast and manie times is taken for oure father’s soul, specialie in a churchyard…

This may or may not be a true indication of the range of creatures the Elizabethan populace actually believed in (satyrs, fauns, nymphs? Really?) but it’s a magnificent rant. It’s as though Scot has thrown together every single supernatural entity he can possibly think of: you can see how one suggests another. The classical ‘satyrs, pans, fauns, syl[v]ans’ run together easily, while ‘Robin good-fellowe, the spoorne, the mare, the man in the oke, the hell waine’ seem more homely night terrors. While many of them are still familiar, others are not. Bull beggars? Spoornes, calcars? What on earth are they?

In her Dictionary of Fairies Katharine Briggs says there is or was a ‘Bullbeggar Lane’ in Surrey which ‘once contained a barn haunted by a bull beggar’. It is probably some variant of bogeyman. ‘Kit with the Canstick’ or ‘candlestick’ may be a variety of will o’ the wisp, leading travellers astray, but there are no folktales about it and if I were writing one I might be tempted to turn it into a domestic spirit, and a sinister one at that. What is a ‘calcar’? I’ve no idea, unless it could by some stretch be a corruption of the Gaelic ‘Cailleach’ – divine hag or old woman. What ‘the spoorne’ might be, no one knows. (Spawn?) The ‘mare’ is the night-mare. The hell-waine is the Devil’s wagon in which he carries souls to hell. In my children's fantasy 'Dark Angels' there's a hill called Devil's Edge, loosely based on Stiperstones in Shropshire (and pictured at the top of this blog); it has earned its name because:

Up on the very top ... there was a road. A road leading nowhere, a road no one used. For if anyone was so bold as to walk along it, especially at night, he’d hear the clamour of hounds and the blowing of horns, the cracking of whips and the rumbling of a cart. And out of the dark would burst the Devil’s own dog pack, dashing beside a black wagon drawn by goats with fiery eyes, crammed full of screaming souls bound for the pits of Hell.

As for the ‘man in the oke’, Katherine Briggs tells of '…scattered reference to oakmen in the North of England, though very few folktales about them…. Most people know the rhyming proverb “Fairy folks live in old oaks”; the Gospel Oak or King’s Oak in every considerable forest had probably a traditional sacredness from unremembered times, and an oak coppice in which the young saplings had sprung from the stumps of unfelled trees was thought to be an uncanny place after sunset…'

There was a huge and ancient Chêne Jupitre or ‘Jupiter Oak’ in the Forest of Fontainebleau when I lived near there in the 1990’s, but it died and was taken down. It’s hard to see how anyone could be frightened by the dimunitive Tom Thumb whom we know of from the fairy tales, but perhaps in the 16th century he was more of a plaguey fairy nuisance like Puck. At any rate his name seems to have suggested ‘Tom Tumbler’ of whom we know nothing.

I’m sure this list (which of course he knew) was behind the list of evil creatures which CS Lewis names in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, who gather behind the White Witch at the Stone Table to kill Aslan:

Ogres with monstrous teeth, and wolves, and bull-headed men; spirits of evil trees and poisonous plants; and other creatures whom I won’t describe because if I did the grown-ups would probably not let you read this book – Cruels and Hags and Incubuses, Wraiths, Horror, Efreets, Sprites, Orknies, Wooses and Ettins.

Still more exuberant is a list of supernatural creatures compiled by Michael Aislabie Denham (died 1859) a well-read Yorkshire merchant who collected and published various ‘Rhymes, Proverbs, Sayings, Prophecies, Slogans, etc.’ as well as pamphlets and anecdotes. Denham goes even further than Reginald Scot, whose list is incorporated – one might almost say buried – in the midst of his own: many of the creatures he names here appear nowhere else, but one must assume that they were once genuine traditions. Some are ancient. 'Portunes', for example, are to be found only in a single instance in the De Nugis Curialium or Courtly Trifles of 12th century man-of-letters Walter Map, who describes them as tiny fairy creatures like little old men who toast frogs in the hearth-ashes at night. It's highly unlikely Denham found any live oral tradition about them in the mid-19th century, and there's little chance of the name leaking back from the written to the oral tradition, as Map's Latin text was not published till 1850, nor translated into English until MR James's edition of 1914. So Denham is certainly overstating the case when he suggests that 'portunes', at least, were generally believed in ‘seventy or eighty years ago’. At this time, he claims,

... the whole earth was so overrun with ghosts, boggles, Bloody Bones, spirits, demons, ignis fatui, brownies, bugbears, black dogs, spectres, shellycoats, scarecrows, witches, wizards, barguests, Robin-Goodfellows, hags, night-bats, scrags, breaknecks, fantasms, hobgoblins, hobhoulards, boggy-boes, dobbies, hob-thrusts, fetches, kelpies, warlocks, mock-beggars, mum-pokers, Jemmy-burties, urchins, satyrs, pans, fauns, sirens, tritons, centaurs, calcars, nymphs, imps, incubuses, spoorns, men-in-the-oak, hell-wains, fire-drakes, kit-a-can-sticks, Tom-tumblers, melch-dicks, larrs, kitty-witches, hobby-lanthorns, Dick-a-Tuesdays, Elf-fires, Gyl-burnt-tales, knockers, elves, rawheads, Meg-with-the-wads, old-shocks, ouphs, pad-foots, pixies, pictrees, giants, dwarfs, Tom-pokers, tutgots, snapdragons, sprets, spunks, conjurers, thurses, spurns, tantarrabobs, swaithes, tints, tod-lowries, Jack-in-the-Wads, mormos, changelings, redcaps, yeth-hounds, colt-pixies, Tom-thumbs, black-bugs, boggarts, scar-bugs, shag-foals, hodge-pochers, hob-thrushes, bugs, bull-beggars, bygorns, bolls, caddies, bomen, brags, wraiths, waffs, flay-boggarts, fiends, gallytrots, imps, gytrashes, patches, hob-and-lanthorns, gringes, boguests, bonelesses, Peg-powlers, pucks, fays, kidnappers, gallybeggars, hudskins, nickers, madcaps, trolls, robinets, friars' lanthorns, silkies, cauld-lads, death-hearses, goblins, hob-headlesses, bugaboos, kows, or cowes, nickies, nacks, waiths, miffies, buckies, ghouls, sylphs, guests, swarths, freiths, freits, gy-carlins, pigmies, chittifaces, nixies, Jinny-burnt-tails, dudmen, hell-hounds, dopple-gangers, boggleboes, bogies, redmen, portunes, grants, hobbits, hobgoblins, brown-men, cowies, dunnies, wirrikows, alholdes, mannikins, follets, korreds, lubberkins, cluricauns, kobolds, leprechauns, kors, mares, korreds, puckles, korigans, sylvans, succubuses, blackmen, shadows, banshees, lian-hanshees, clabbernappers, Gabriel-hounds, mawkins, doubles, corpse lights or candles, scrats, mahounds, trows, gnomes, sprites, fates, fiends, sibyls, nicknevins, whitewomen, fairies, thrummy-caps, cutties, and nisses, and apparitions of every shape, make, form, fashion, kind and description, that there was not a village in England that had not its own peculiar ghost. Nay, every lone tenement, castle, or mansion-house, which could boast of any antiquity had its bogle, its spectre, or its knocker. The churches, churchyards, and crossroads were all haunted. Every green lane had its boulder-stone on which an apparition kept watch at night. Every common had its circle of fairies belonging to it. And there was scarcely a shepherd to be met with who had not seen a spirit!

You will have noticed the 'hobbits', about two-thirds of the way through? All I can say is that here, indeed, is scope for the creative imagination.

Picture credits:

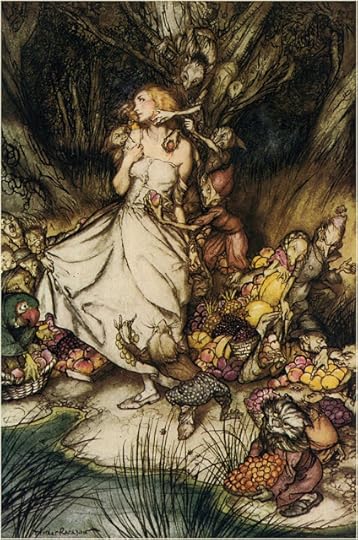

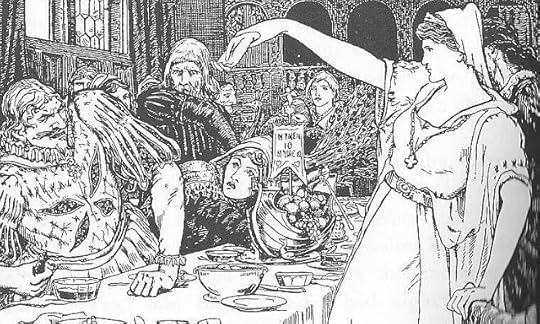

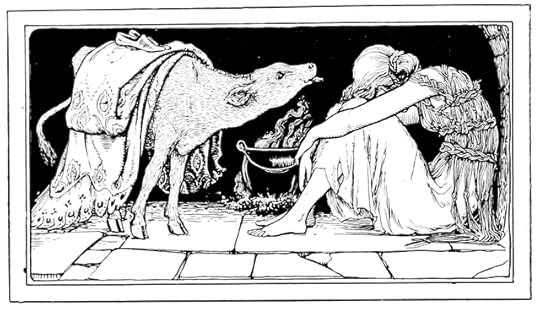

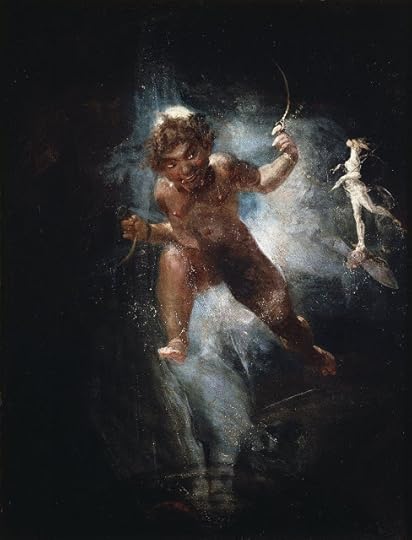

Witch and familiars: by Arthur Rackham

The fairy 'Yallery Brown': by John Batten

Aslan in the power of the White Witch: by Pauline Baynes

From 'Goblin Market': by Arthur Rackham

Published on November 17, 2016 00:53

October 26, 2016

Imagined Afterlives: Death in Classic Fantasy

What – if anything – happens after death? A fantasy world, no matter how beautifully constructed, lacks something if there’s no thought given to what happens when characters die, or at least to what beliefs they hold about what may happen. We live not only in the physical universe but in our mental construction of it. Death is a huge subject for humanity, and so not unnaturally Life and Death are recurrent themes in some of the fantasies I love best – The Lord of the Rings, the Narnia stories, Ursula K Le Guin’s Earthsea books, Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, and the Old Kingdom novels of Garth Nix.

To begin with Tolkien: though mortal, Hobbits don’t seem to have a theory of the afterlife. Innocent, rural, physical, they thoroughly enjoy this life’s pleasures and die with a sense of fulfilment: a long life well lived. Can Bilbo outlive the Old Took? He will if he can. We are told nothing of Hobbit funerals except at the very end of The Return of the King where the hobbits who fell at the Battle of Bywater are laid together ‘in a grave on the hillside, where later a great stone was set up with a garden around it.’ Their names live on in memory, but there’s no speculation about a hobbit heaven, just a practical disposal of the mortal remains – and an equally practical interest in inheritance.

Dwarves are mortal too. From the evidence of Balin’s tomb in Moria they build, as you’d expect, good solid stone monuments to commorate their dead. Again there’s little evidence of a dwarfish belief in an afterlife, but a mystical streak is apparent in Gimli’s hints about their creator-ancestor Durin, a hero-king asleep under the stone, who will one day awake – and who, according to Appendix A, is occasionally reincarnated in a child of his line. Then there are the Ents. Though some, like Treebeard, are immensely ancient, Ents are probably not immortal. Since they have lost the Entwives there can be no more Entlings and their race will dwindle. Some Ents become more and more like trees, and even the oldest tree eventually dies, though a truly tree-ish Ent may hardly notice. The Elves are immortal unless killed in battle, or unless like Lùthien and Arwen they choose mortality – but the trees of Lothlorien are in eternal autumn, their springtime long passed, and more and more of the Fair Folk are heading for the Grey Havens.

The point about Mortal Men in Middle-earth isthat they are mortal. The Riders of Rohan view death as a feasting-hall of the brave, like the Norse Valhalla; their poetry is full of Anglo-Saxon melancholy, laden as Legolas says, ‘with the sadness of Mortal Men’:

‘Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing? Where is the helm and the hauberk and the bright hair flowing? Where is the hand on the harpstring and the red fire glowing?’

In accordance with the Norse heroic code, Théoden on the Field of Pelennor dies contented, knowing he leaves behind him a good name: ‘I go to my fathers. And even in their mighty company I shall not now be ashamed. I felled the black serpent.’ Sad though it is, his death makes sense as part of a fitting and seamless succession which is emphasised by the stretcher-bearers’ response to Prince Imrahil:

‘What burden do you bear, Men of Rohan?’ he cried. ‘Théoden King,’ they answered. ‘He is dead. But Éomer King now rides in the battle: he with the white crest in the wind.’

When the Men of Gondor die, or at least their kings and stewards, they are laid to rest in tombs of stone in Rath Dínen, the Silent Street under Mount Mindolluin. It appears from Denethor’s words that they think of death as a long solitary sleep rather than ancestral companionship in an eternal feasting hall – but this may not always have been so:

‘No tomb for Denethor and Faramir! No tomb! No long slow sleep of death embalmed. We will burn like heathen kings before ever a ship sailed hither from the West…’

One way or another, Mortal Men must accept death. Clinging on to this world may lead to the worst possible thing that can happen: they may become wraiths like the Barrow-wights on the Barrow-Downs, or like the Ringwraiths.

Finally, for the Ring-bearers Frodo and Bilbo (and possibly later for Sam) there’s the unusual opportunity to go bodily into the West on an Elven ship. Unlike the film, in which Gandalf comforts Pippin with a description of Eressëa or possibly Valinor, the book makes clear that this is a special privilege. As Frodo’s ship passes into the West,

… it seemed to him that as in his dream in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise.

But to Sam the evening deepened into darkness as he stood at the Haven, and as he looked at the grey sea he saw only a shadow on the waters that was soon lost in the West.

A deep vein of nostalgic sadness runs through the heart of The Lord of the Rings. Except for Men, all of the different races are doomed either to fade or pass from Middle-earth. And in the process of his journey, Frodo leaves behind not only the comfortable rural beauty of the Shire, but the very person he was. Suffering, and his immense struggle with the Ring change him into someone different – nobler, wiser maybe, but maimed, changed, sadder. We can only hope that the West will heal him. We will never know.

The Narnia books contain little of this nostalgia. C.S. Lewis is very clear about life after death: it’s Aslan’s country, and several of his characters actually go there in life – Jill and Eustace start out for Narnia from Aslan’s holy Eastern mountain, for example, and the heroic Reepicheep sails there in his coracle.

Remarkably, through the first six books of the Chroniclesthis certainty does not negate the sorrow of mortality. Death, when it occurs, is given emotional weight. Aslan’s death in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is genuinely moving, partly because of the depth of grief of Lucy and Susan, and so is Caspian’s death in The Silver Chair, witnessed from a distance by Jill and Eustace. The very old King lifts his hand to bless his long-lost son, then falls back –

The Prince, kneeling by the the King’s bed, laid down his head upon it, and wept. There were whisperings and goings to and fro. Then Jill noticed that all who wore hats, bonnets, helmets or hoods were taking them off – Eustace included. Then she heard a rustling and flapping noise up above the castle; when she looked up she saw that the great banner with the golden Lion on it was being brought down to half-mast. And after that, slowly, mercilessly, with wailing strings and disconsolate blowings of horns, the music began again: this time, a tune to break your heart.

Aslan blows all these things away ‘like wreaths of smoke’ and the children find themselves once more in Aslan’s country ‘among mighty trees and beside a fair, fresh stream’. But the funeral music continues.

And there, on the golden gravel of the bed of the stream lay King Caspian, dead, with the water flowing over him like liquid glass. His long beard swayed in it like water weed. And all three stood and wept.

Their tears are shed, it seems to me, as much for age and feebleness and the sorrows of life, as they are for the fact of death. The deliberate parallel is with the New Testament story of Jesus weeping over Lazarus’s tomb: even though he knows he is about to bring Lazarus back to life. So too here. Caspian’s death is about to be reversed by a drop of Aslan’s blood. For me, this works. It’s not a facile trick. To obtain the blood, Eustace must drive a thorn ‘a foot long and as sharp as a rapier’ into the great pad of Aslan’s paw: we feel the cost and the pain. But at the end of The Last Battle, where Narnia itself is replaced by what we are meant to believe is a greater and better Kingdom, Lewis’s attempt is an artistic failure. The Christian agenda takes over; he tries to do too much: heaven isn’t Aslan’s holy mountain any more, it’s Narnia and Archenland and Calormen and England combined. It’s messy. I far prefer that numinous glimpse of mountains behind the rising sun at the eastern rim of the world, in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Heaven, a place of reward for a good life or of union with a good God, is not quite the same thing as the ‘land of the dead’ – that twilight place where ever since classical times the shades of the departed have swarmed in voiceless, strengthess hordes, unable to speak unless given a drink of sacrificial blood. (The notion that a blood sacrifice gives life to the dead must be one of the most ancient of beliefs.) Visiting Persephone’s kingdom beyond the Stream of Ocean, Odysseus attempts to embrace his mother’s shade, but she flutters out of his arms like a shadow and ‘sorrow sharpened at the heart within me’. This is what happens to everyone, his mother tells him, for once

‘the sinews no longer hold the flesh and the bones together,and once the spirit has left the white bones, all the restof the body is made subject to the fire’s strong fury,but the soul flitters out like a dream and flies away.’

The Odyssey, XI, 219-223, tr. Richmond Lattimore

Famous too is the rebuke of the dead hero Achilles when Odysseus tries to console him by telling him of the fame he has won among the living.

‘O shining Odysseus, never try to console me for dying.I would rather follow the plough as thrall to anotherman, one with no land allotted to him and not much to live onthan be a king of all the perished dead.’

The Odyssey, XI, 488-491, tr. Richmond Lattimore

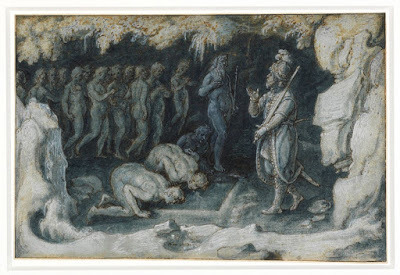

Odysseus in the Underworld, Johannes Stradanus

Odysseus in the Underworld, Johannes StradanusThis type of afterlife, a shadow-life devoid of human meaning, is found in Ursula K Le Guin’s Earthsea books. In A Wizard of Earthsea the young wizard Ged splits open the fabric of his world in arrogant anger to summon the spirit of the beautiful Elfarran, a thousand years dead. Through the gap he has made scrambles a ‘clot of black shadow’ which leaps at him and rips his face. It hunts him from one side of the Archipelago to the other, and not until Ged learns to confront his own darkness can he undo his deed.

The Earthsea books are deeply concerned with the interdependence of light and darkness, life and death, and in the early titles the land of the dead is conceived as a necessary counterweight to the world of the living. It’s a place of dust, darkness and silence, divided from life by a low wall of stones ‘no higher than a man’s knee’. The dead are passive, passionless:

No marks of illness were on them. They were whole, and healed. They were healed of pain, and of life. They were not loathsome as Arren had feared they would be, not frightening… Quiet were their faces, freed from anger and desire, and there was in their shadowed eyes no hope.

Instead of fear, then, great pity rose up in Arren, and if fear underlay it, it was not for himself, but for us all. For he saw the mother and child who had died together, and they were in the dark land together; but the child did not run, nor did it cry, and the mother did not hold it, nor even look at it. And those who had died for love passed each other in the street.

The Farthest Shore

Terrible as this is, it possesses a poignancy reminiscent of the Odyssey. In the three early Earthsea books you can’t have life without death:

Only in dark the light, only in dying life: bright the hawk’s flight on the empty sky.

The message of The Farthest Shore is that death is a natural and necessary end. The mage Cob is so terrified of dying that he tries to put an end to it, ‘to find what you cowards could never find – the way back from death.’ In doing so he threatens the balance of Earthsea and himself becomes an eyeless, nameless sorceror who belongs to neither life nor death. Mere continued existence, it turns out, is a curse. ‘You cannot see the light of day, you cannot see the dark,’ Ged tells him. ‘You sold the green earth and the sun and stars to save yourself. But you have no self.’

In the two later books, Tehanu and The Other Wind, Le Guin revisits Earthsea and remakes some of what she has done. Dragons and their relationship with humankind become important, and the very nature of the land of death is re-examined. In The Other Wind Alder, a young sorceror whose wife has died, is tormented by dreams in which she and others of the dead come to the wall of stones and beg to be set free. He tells Ged,

I thought if I called her by her true name maybe I could free her, bring her across the wall, and I said, ‘Come with me, Mevre!’ But she said, ‘That’s not my name, Hara, that’s not my name any more.’ And she let go my hands, though I tried to hold her. She cried, ‘Set me free, Hara!’ But she was going down into the dark.

These dead are neither passive nor passionless, and they recognise and commune with the living man Alder. Instead of maintaining the mystical equilibrium of Earthsea, the land of the dead is now seen to be upsetting it. Humankind and dragons were once one race which divided the world between them. Humans chose to own and make things; dragons chose freedom to fly ‘on the other wind’ in a timeless realm beyond the west. However, ‘the ancient mages craved everlasting life’ and used ‘true names to keep men from dying’. And – so the dragon Irian cries –

‘by the spells and wizardries of those oath-breakers, you stole half our realm from us, walled it away from life and light, so that you could live there forever. Thieves, traitors!’

It now seems the land of death is a dreadful compromise, an everlasting trap. It divorces those in it from the universe, which is the only life. The solution is to pull down the wall of stones and let the dead go free. Some rise up ‘flickering into dragons’ on the wind, but most come ‘walking with unhurried certainty’ to step across the ruined wall and vanish, ‘a wisp of dust, a breath that shone an instant in the ever-brightening light.’ And where have they gone? As Alder said, ‘It is not life they yearn for. It is death. To be one with the earth again. To rejoin it.’

It’s lovely, but I don’t think it quite works. It’s too complicated, too different from the earlier books. It takes a lot to undo the quietly terrible beauty of the dead land in A Wizard of Earthsea, its inhabitants ‘healed of life’. The dying child whom Ged fails to heal in A Wizard of Earthsea runs ‘fast and far away from him down a dark slope, the side of some vast hill’ – and that eagerness feels right. In these early books, the dead are shadows with no internal life. They feel no pain because they are already gone. It seems to me a mistake to reinvent this metaphor, and the events of The Other Wind make nonsense of the rebuke Ged delivers to Cob in The Farthest Shore.

The impulse to harrow hell and bring out the souls is felt also by Philip Pullman in The Amber Spyglass, the final book in the trilogy His Dark Materials. Like Lewis, Pullman has an agenda (Darwinian and anti-religious) and like Le Guin he turns to what one might call the Wordsworthian ‘back to nature’ view of death – the dissolution of personality and the blending of the body and its atoms with the physical universe.

No motion has she now, no force,She neither hears nor sees,Rolled round in earth’s diurnal courseWith rocks, and stones, and trees.

‘A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal’, William Wordsworth

The problem is to convince the reader that this is an acceptable personal outcome. Does that sound frivolous? My own belief, if you want it, is that Wordsworth and Pullman and Darwin are right. I don’t think there’s a life after death. I don’t find that scary, but neither does it give me joy. Only life can do that. In fiction, paradoxically, it seems the best way to make the no-afterlife option appear positive is to contrast it with an afterlife, but an unpleasant one – thus making the point via a sort of authorial sleight-of-hand. (‘You can have an afterlife, but you won’t enjoy it.’)

Aeneas and the Sibyl in Hades

Aeneas and the Sibyl in HadesPullman’s land of the dead is a considerably less attractive proposition even than Le Guin’s. It is modelled on the Hades of Virgil’s Aeneid, rather than on Homer’s Odyssey. In the Aeneid, after sacrificing to Night, Earth, Proserpina and Hades, Aeneas ventures underground guided by the Sibyl. He passes gates guarded by monsters and crosses the river Styx with the ferryman Charon, who at first refuses to carry a living man over:

‘… Thisis a realm of shadows, sleep and drowsy night. The law forbids me to carry living bodies acrossin my Stygian boat…’

The Aeneid, tr. Robert Fagles

In The Amber Spyglass, there are perhaps rather too many stages to death. Lyra and her friends begin their exodus from life via a farmhouse kitchen of the recently slain, following their shocked ghosts into a grey and ever-darkening landscape, ‘thousands of men and women and children … drifting over the plain’, drawn onwards and down to shantytown suburbs of death on the shores of a mist-bound lake. In my opinion the refugee metaphor gets away from Pullman and over-complicates the narrative. Living officials – I’m not sure why they’re alive – demand to see papers, and direct the travellers to ‘holding areas’ past ‘pools of sewage’. Taking shelter in a shanty, Lyra learns that each ghost must wait until his or her personified ‘death’ gives them leave to cross over the lake, so Lyra must call up her own death before she can continue. She does, but there is a further complexity. Returning to the classical norm, the ferryman refuses to carry Lyra across the lake unless she leaves behind her beloved daemon, spirit-self and other half, Pan:

‘It’s not a rule you can break. It’s a law like this one…’ [The ferryman] leaned over the side and cupped a handful of water, and then tilted his hand so it ran out again. ‘The law that makes the water run back into the lake, it’s a law like that.’

The Amber Spyglass

After this anguished parting Lyra, Will and the dragonfly-borne Gallivespians cross the river to land at a wharf and rampart. They pass through a great gate guarded by screaming harpies and find beyond it a vast and dismal plain crowded with listless, voiceless ghosts who, as ever, require blood.

They crammed forward, light and lifeless, to warm themselves at the flowing blood and the strong-beating hearts of the two travellers…

Once they can communicate, Lyra asks to be led to her friend Roger (for whose death she feels responsible), but when she finds him ‘he passe[s] like cold smoke through her arms’. Determining to release all the dead from this Hades, Lyra consults the alethiometer and explains to the ghosts what will happen to them:

‘… it’s true, perfectly true. When you go out of here, all the particles that make you up will loosen and float apart, just like your daemons did. … But your daemons en’t just nothing now; they’re part of everything. … You’ll drift apart, it’s true, but you’ll be out in the open, part of everything alive again.’

‘It’s true, perfectly true’. Here Pullman himself speaks through Lyra, pleading and passionate, promising no lies, no deceit. The science-based truth of this account of death is indisputable. The body does indeed return to the earth that gave it. The difficulty is that these ghosts’ bodies must – most of them – already have disintegrated, yet here their spirits inhabit an afterlife in which personality and personal memories survive as some form of post-mortem energy. Accepting Lyra’s offer, one of the ghosts says,

‘… the land of the dead isn’t a place of reward or a place of punishment. It’s a place of nothing...’

But is this true? Compared with Le Guin’s dark, neutral world under the unchanging stars, Pullman’s land of the dead is a place of punishment. As Roger’s ghost tells Lyra:

Them bird-things… You know what they do? They wait till you’re resting – you can’t never sleep properly, you just sort of doze – and they come up quiet beside you and they whisper all the bad things you ever did when you was alive … They know how to make you feel horrible … But you can’t get away from them.

The harpies have been set by the Authority ‘to see the worst in everyone’ and to feed on them. Lyra and her companions come up with a solution. From now on, instead of lies, each person who dies must nourish the harpies with a truthful account of all the things they’ve seen and heard, touched and learned. Experience of life, in other words, trumps death. I like this, a lot: and Roger’s final release into the physical universe, with a laugh of surprise and a ‘vivid little burst of happiness’ is moving. Nevertheless the effect of this joyful annihilation very much depends on Pullman’s depiction of the afterlife as a distinctly worse option.

Garth Nix, in his series of ‘Old Kingdom’ novels beginning with Sabriel, has so far as I can tell no particular religious or scientific points to make, and his fantasy has a corresponding air of freshness and freedom – even playfulness – all of its own. Life and Death are of paramount interest, since the Old Kingdom is a magical land under continuous threat of necromancy. It is divided by a Wall (perhaps suggested by Le Guin’s, though this is not a Life/Death boundary) from the non-magical southern land of Ancelstierre. I don’t know what happens to Ancelstierrans when they die, but those who die in the Old Kingdom cross an unseen border into the state of Death itself, a coldly flowing river without banks which sweeps them away through a series of nine Gates. In the stretches of river between these Gates – the Precincts – it’s possible for some Dead to cling on or even retrace their steps:

It had been human once, or human-like at least, in the years it had lived under the sun. That humanity had been lost in the centuries the thing spent in the chill waters of Death, ferociously holding its own against the current, demonstrating an incredible will to live again. ... Its chance finally came when a mighty spirit erupted from beyond the Seventh Gate, smashing through each of the Upper Gates in turn, till it went ravening into Life. Hundreds of the Dead had followed and this particular spirit… had managed to squirm triumphantly into Life.

Sabriel

The Lesser Dead, such as this one, need to take over human or animal bodies for their use. The Greater Dead who come from beyond the Fifth Gate are sufficiently powerful to exist in Life without a physical body. (A further danger are Free Magic Creatures, perilous elemental beings outside the ordered power of the Charter, but these are not the Dead.)

The returning Dead are uniformly malevolent, and it’s the job of the Abhorson – Sabriel herself – to return them to Death and send them down the River and past the Ninth Gate. This she does by means of a set of seven enspelled bells, infused with beneficent Charter Magic created – or perhaps discovered or formalised? – long ago by the immortal Seven Bright Shiners, each one of which is represented by a named bell.

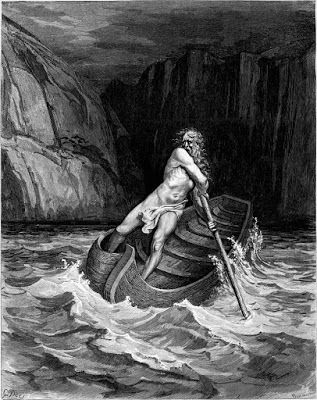

The idea of a River of Death is hardly a new one; it goes back to ferryman Charon rowing souls across the Styx, and further still to the boatman Ur-shanabi in the Epic of Gilgamesh – but what Garth Nix has done with it is different: instead of a boundary which must be crossed, his River of Death is a dynamic process – a progression, a vivid natural force which grasps the dying soul and sweeps it away. As such there is a ‘rightness’ about consenting to its power and a corresponding ‘wrongness’ when the dead struggle literally to swim against the stream. More than that, as a metaphor for death a river is nothing like the static, dusty dead lands which so trouble Ursula K Le Guin and Philip Pullman. A river is about motion, exhilaration and strength. A river has a direction and a purpose.

Not until the third book in the series, Abhorson, do we really learn the geography of Death as Nix takes the reader all the way down the River through every Gate with Lirael, the Abhorson-in-Waiting, along with her inseparable companion the Disreputable Dog. Each Gate has its own character, each Precinct its own perils, not only sneaking souls and monstrous foes but the River itself:

The Second Gate was an enormous hole, into which the river sank like sinkwater down a drain, creating a whirlpool of terrible strength.

Abhorson

While beyond it in the Third Precinct –

The river there was only ankle deep, and little warmer. The light was better too. Brighter and less fuzzy, though still a pallid grey. Even the current wasn’t much more than a trickle around the ankles. All in all, it was a much more attractive place than the First or Second Precincts. Somewhere ill-trained or foolish necromancers might be tempted to tarry or rest. If they did, it wouldn’t be for long – because the Third Precinct had waves…

Lirael and the Dog battle through mists, waterfalls, metamorphic waters, a ‘waterclimb’, floating flames – and finally the Ninth Gate, where the River finally does what rivers always do. It flows out into something greater than itself, ‘a great flat stretch of sparkling water’ – along with the souls it carries. Overhead is an immense sky ‘so thick with stars that they overlapped and merged to form one unimaginably vast and luminous cloud.’

Lirael felt the stars call to her and a yearning rose in her heart to answer. She sheathed bell and sword and stretched her arms out, up to the brilliant sky. She felt herself lifted up, and her feet came out of the river with a soft ripple and a sigh from the waters.

Dead rose too, she saw. Dead of all shapes and sizes, all rising up to the sea of stars.

This at last is the ‘final death from which there could be no return.’

For me, this is inexpressibly moving. There’s no judgement. Whatever has happened before, whatever the dead may have done during Life and after it, from this perspective looks insignificant. The journey through Death may be full of terrors; a spirit may go kicking and screaming all the way down the River, struggling to turn around and go back to Life. But once beyond the Ninth Gate the sight of the stars is revelatory and transformative. Letting go of Life at last, the dead fall serenely upwards into a tranquil universe.

All the classic fantasies I’ve looked at in this essay engage with the fact of death and what happens after, and all attempt answers. Tolkien and Lewis were both Christians, but their answers are very different. Tolkien’s Mortal Men have no assurance of an afterlife, for the immortality of Middle-earth is in the Undying Lands, and passage there is in the gift of the Elves. Gondor’s dead pass to an eternal sleep; the Rohirrim feast with their ancestors. For Narnians, there’s the happy certainty of Aslan’s country, a place which Lewis wishes to assure us is not less but more real than life: the Platonic solid of which the mortal Narnia is but a shadow. In Ursula K Le Guin’s early Earthsea books, the land of the dead is the darkness which is the other half of light: you can’t have one without the other. She rethought that in the last book, turning the duality into a unity from which the spirits of the dead evanesce into light. No more darkness. For Philip Pullman, passionately concerned to do away with what he considers to be the lies of heaven and hell, Lyra’s journey through the land of the dead becomes a sort of allegorical exposition in which the afterlife is shown to be a cruel and hollow sham and the truth of dissolution is the best happiness. And in Garth Nix’s metaphor of the river – with all its adventures, snags, gates, rapids and waterfalls – death is a natural force, to resist which is to become unnatural. In the end, the river will always win and sweep us on into vastness.

My final thought: we cannot think about death without making pictures.

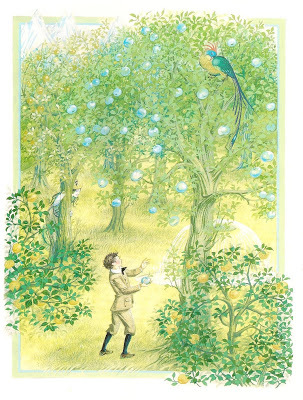

Picture credits:

Digory and the Tree of Life, from 'The Magician's Nephew', Pauline BaynesNight Falls on Narnia, from 'The Last Battle', Pauline BaynesOdysseus in the Underworld, by Johannes Stradanus, 1523-1605Aeneas and the Sybil in Hades, Anon, Wikimedia CommonsCharon, by Gustave DoreCrossing the Styx, by Gustave Dore

Published on October 26, 2016 04:05

October 8, 2016

"Where the Monsters Lurk"- a guest post by Garth Nix

Where the Monsters Lurk - by Garth Nix

I have an affinity with creatures, at least on the page. I like to make up horrible monsters and include them in my stories. Things that walk on spiked feet, striking sparks from stone; monsters made from gravemould and blood; misshapen spirits reemerging from Death; malignant spirits from some terrible ancient time, unwittingly awoken.

Where do these creatures come from? Until I was asked this question, I must confess I’ve never really thought about it. At various points in stories I need monsters, and they always seem to be in my head, waiting to be written down. Or at least the seed will be there, and as I begin to write about them, they grow and become fully-fledged. Fortunately, they are notthere until I need them: my mind is not constantly teeming with a zoo-full of terrifying monsters clamouring to be let out.

But even though they do seem to be there when I need to write them, I realize on examination that it’s not as straightforward as that. My subconscious is probably aware of the fact I will need a monster long before my conscious writing brain catches up on it, and the reason one will be there is almost certainly due to the fact that over my entire lifetime I have been equipping myself to be a maker of monsters. Mentally, that is, for literary purposes only. I have refrained from building a secret laboratory in my back garden to recombine insect and human DNA for example, and actually make my own. Honest.

I began, of course, with other people’s monsters. In picture books when I was very young, I particularly liked dragons and bears, and I guess at that age (and to some degree still) preferred it when the creatures turned out to have much nicer and kinder than their fangs and spikes suggested. But not soon after, as I moved on to chapter books and full-sized novels, I wanted stories with monsters who were inimical. Creatures to be defeated, or tamed, or banished. I wanted that growing sense of dread as their presence was hinted at, the thrill of their first appearance, and then the rush of excitement as they were dealt with by the protagonist or their allies.

Many of my first encounters with such monsters came from children’s books about myth and legends, typically from the Greek and Norse myths. I have Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedia and the magazine Look and Learn to thank for meeting the Minotaur, and Pegasus, the Midgard Serpent, Frost Giants, Medusa and many more.

While I loved these myths and legends, they were often told in a way that made them feel like history. I am fascinated by history and I read a great deal of it, but when I was a child this storytelling technique was often a distancing one. So the creatures of myth and legend were not less alive, but they felt more distant to me than more modern fiction where I could feel that I was with the main character experiencing it all, or in fact, I was the main character, going up against these monsters. Or running away from them, which as I grew older appeared more and more sensible and realistic.

These very identifiable stories of monster experience possibly began for me with The Hobbit, which was first read to me by my parents around the age of six or seven and I started reading it myself to get ahead. I not only identified with Bilbo, but also with the Dwarves and Gandalf. Reading it, I was with them, and I was them, and we were all out on that winding road having adventures, which necessarily including meeting monsters.

The Hobbit also has very distinctive monsters, never just stage pieces rolled out to get an “ooh” from the crowd before they trundle around a bit and disappear. From very early on, we have the Trolls who combine humour with dread (which is quite difficult to do); the goblins who I think embody the fear of hostile crowds (the individuals are not so scary, but en masse it is quite different), a fear greatly magnified by darkness; Gollum, who is both creature and major character; the spiders of Mirkwood, which for an Australian arachnophobe were particularly daunting, again made somewhat easier to cope with by humour; and of course, Smaug, who like Gollum is both a monster and a major character.

Many other books taught me how to make monsters and what to do with them. I’m writing this while somewhat jetlagged after flying from Sydney to Boston, so this is by no means an exhaustive list and I’m bound to forget some important examples, but here are just some of the authors whose creatures impressed me deeply at a young age, and in so doing, inadvertently helped me prepare to make up and use monsters in my own fiction.

Alan Garner for the Brollachan in The Moon of Gomrath, and generally for his creatures that feel very deeply connected to myth and legend.

Tolkien, beyond The Hobbit, for the Nazgul and Shelob, the Balrog, the classic creature of fantasy (so often imitated), the many varieties of Orc, for Sauron himself and more.

Ursula Le Guin, for many things, but for the dragons in A Wizard of Earthsea and sequels, as important monster characters, and for the sense of their enormous age and deep connection to the earliest history of Earthsea.

Andre Norton, who across numerous books made monsters that I loved in my childhood reading, but most particularly whatever it was that the archaeological machine in her sci-fi novel Catseye almost brought back from the past, its time shadow, as it were, enough to drive people insane . . . the hint of a monster and the effects of its presence as effective or perhaps even more effective than any description.

There are many more, of course, too many to list or for my jetlagged mind to immediately produce. These books, and others, provided me with something of an apprenticeship in monster-making, and of course began to equip my mind with the tools for storytelling in general.

But in addition to my reading, something else helped me along in my monster-making endeavours. When I was twelve years old, I saw in a games shop a small white box that contained three booklets named Men & Magic; Monsters & Treasure; and The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures. In other words, Dungeons and Dragons.

I already liked games, and had recently started playing miniature wargames, but these three booklets were a revelation to me, because they were about playing games that were fantasy stories, basically about being in a story. Within a day of reading the rulebooks I recruited five friends from school and we started playing. Perhaps because I’d bought the rules, I was the dungeonmaster, though I suspect it was more to do with my natural authorial tendencies that were already in evidence back then. I wanted to direct the story as much as be part of it.

Dungeons & Dragons, as required for game purposes, gave monsters characteristics. I could look up a creature in Monsters and Treasure and see its armour class, and hit dice, and its attacks values and so on. There was also a brief description, sometimes including special characteristics that were not easily handled by the games’ basic mechanics. In those early days, these characteristics and game mechanics were far simpler than they later became, but in some ways I think that was useful because it gave more leeway to me as a dungeonmaster to use the creatures in my own way and I am glad that even at twelve, I fully took on that the three booklets were a skeleton structure to make something of one’s own, not a restrictive or exhaustive set of rules.

This was made explicit by D&D authors Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, but even so, some players and dungeonmasters treated the rules as set in stone.

To me, and most other players, the open nature of D&D and later role-playing games provided enormous scope to develop our own adventures, and one of the main parts of this was, of course, developing new monsters beyond those in the original rulebooks and later supplements (of which there would be a veritable plethora, continuing to this day).

I first started by adapting monsters that weren’t in the rule books, taking monsters and creatures out of my favourite books and working out their characteristics in D&D terms. What I didn’t realize back then, though, was that one of the primary reasons these monsters would work in a role-playing game adventure wasn’t because I’d got their game attributes right, it was because they were already so well-defined and real from the stories I’d got them from (which the players had invariably read as well), so the mere mention of some distinguishing part of their appearance or behavior would lead to the players knowing what they were up against, with the consequent emotional impact derived from the shared experience of the story.

I guess what I’m saying here is that you can work out all the mechanistic details of a creature and its description and so on, as if defining it for a game or an encyclopedia or some data file, but this does not make it come alive and does not make it feel real to either roleplayers or readers. What does do this is story, and the monster’s place in it. In fact, as in Catseye I mentioned above (and in many horror stories), it is quite possible that never actually describing or detailing a monster might make it all the more effective. A reader needs to be provided with just enough information (which might be overt description, it might be character’s reactions to the creature, it might be dialogue, it might be mere allusion) to enable them to imagine the creature themselves, and whatever the reader thinks up themselves will be invariably more terrifying and effective than a huge amount of text from the author.

So, my apprenticeship in monster-making began with reading and continues to this day with reading; later to be enhanced by the once-a-week D&D sessions I ran for a good part of my teenage years; and then continued with writing, as I began to want not just to read stories, and co-create them in an RPG environment, but also to make stories that were my own.

Many fantasy writers begin with their worlds, working them out in a great deal of detail, and often this will include the creation and development of creatures. Sometimes they will be entirely original, sometimes they will be drawn from myth or legend, and sometimes they will be orcs from Tolkien. (Orcs are a very invasive species, it seems, given their ability to infest so many different fantasy books. Sometimes they are called something different, though we all know “that which we call an orc by any other name would smell as foul.”)

Developing the world first is a very effective technique, one adopted by many great writers, but it’s not one that I follow. I tend to discover my fantasy world as I go along, I only work out what I need for the story as I need it, and this also applies to creatures.

So from my very earliest stories, I would be writing away and then all of a sudden I would need a monster, and as I said at the very beginning of this piece, I would usually find one waiting in my head. Or at least the beginnings of one, often just a sense of what kind of feeling I want to evoke with that creature, or perhaps some minor point of physical description. And there I will pause for a while, sometimes for a few minutes, sometimes for a few days, while the necessary minimum I need to know about that monster rises to my conscious and can be used in the story. I say the necessary minimum because as I’ve mentioned above, I don’t want to give too much to the reader, I want to supply the catalyst for their imagination to finish creating the monster for themselves.And now, because I am writing this while on tour for Goldenhand, I’m afraid I must away. Perhaps appropriately to New York Comic Con, where I will see depictions of many monsters, but not I trust, encounter any real monsters lurking within. Which leads to a closely related topic: about how humans are the real monsters . . .

Garth Nix, October 2016

Published on October 08, 2016 08:11

"Where the Monsters Lurk"- a guest post by Garth NixI ha...

"Where the Monsters Lurk"- a guest post by Garth Nix

I have an affinity with creatures, at least on the page. I like to make up horrible monsters and include them in my stories. Things that walk on spiked feet, striking sparks from stone; monsters made from gravemould and blood; misshapen spirits reemerging from Death; malignant spirits from some terrible ancient time, unwittingly awoken.

Where do these creatures come from? Until I was asked this question, I must confess I’ve never really thought about it. At various points in stories I need monsters, and they always seem to be in my head, waiting to be written down. Or at least the seed will be there, and as I begin to write about them, they grow and become fully-fledged. Fortunately, they are notthere until I need them: my mind is not constantly teeming with a zoo-full of terrifying monsters clamouring to be let out.

But even though they do seem to be there when I need to write them, I realize on examination that it’s not as straightforward as that. My subconscious is probably aware of the fact I will need a monster long before my conscious writing brain catches up on it, and the reason one will be there is almost certainly due to the fact that over my entire lifetime I have been equipping myself to be a maker of monsters. Mentally, that is, for literary purposes only. I have refrained from building a secret laboratory in my back garden to recombine insect and human DNA for example, and actually make my own. Honest.

I began, of course, with other people’s monsters. In picture books when I was very young, I particularly liked dragons and bears, and I guess at that age (and to some degree still) preferred it when the creatures turned out to have much nicer and kinder than their fangs and spikes suggested. But not soon after, as I moved on to chapter books and full-sized novels, I wanted stories with monsters who were inimical. Creatures to be defeated, or tamed, or banished. I wanted that growing sense of dread as their presence was hinted at, the thrill of their first appearance, and then the rush of excitement as they were dealt with by the protagonist or their allies.

Many of my first encounters with such monsters came from children’s books about myth and legends, typically from the Greek and Norse myths. I have Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedia and the magazine Look and Learn to thank for meeting the Minotaur, and Pegasus, the Midgard Serpent, Frost Giants, Medusa and many more.

While I loved these myths and legends, they were often told in a way that made them feel like history. I am fascinated by history and I read a great deal of it, but when I was a child this storytelling technique was often a distancing one. So the creatures of myth and legend were not less alive, but they felt more distant to me than more modern fiction where I could feel that I was with the main character experiencing it all, or in fact, I was the main character, going up against these monsters. Or running away from them, which as I grew older appeared more and more sensible and realistic.

These very identifiable stories of monster experience possibly began for me with The Hobbit, which was first read to me by my parents around the age of six or seven and I started reading it myself to get ahead. I not only identified with Bilbo, but also with the Dwarves and Gandalf. Reading it, I was with them, and I was them, and we were all out on that winding road having adventures, which necessarily including meeting monsters.

The Hobbit also has very distinctive monsters, never just stage pieces rolled out to get an “ooh” from the crowd before they trundle around a bit and disappear. From very early on, we have the Trolls who combine humour with dread (which is quite difficult to do); the goblins who I think embody the fear of hostile crowds (the individuals are not so scary, but en masse it is quite different), a fear greatly magnified by darkness; Gollum, who is both creature and major character; the spiders of Mirkwood, which for an Australian arachnophobe were particularly daunting, again made somewhat easier to cope with by humour; and of course, Smaug, who like Gollum is both a monster and a major character.

Many other books taught me how to make monsters and what to do with them. I’m writing this while somewhat jetlagged after flying from Sydney to Boston, so this is by no means an exhaustive list and I’m bound to forget some important examples, but here are just some of the authors whose creatures impressed me deeply at a young age, and in so doing, inadvertently helped me prepare to make up and use monsters in my own fiction.

Alan Garner for the Brollachan in The Moon of Gomrath, and generally for his creatures that feel very deeply connected to myth and legend.

Tolkien, beyond The Hobbit, for the Nazgul and Shelob, the Balrog, the classic creature of fantasy (so often imitated), the many varieties of Orc, for Sauron himself and more.

Ursula Le Guin, for many things, but for the dragons in A Wizard of Earthsea and sequels, as important monster characters, and for the sense of their enormous age and deep connection to the earliest history of Earthsea.

Andre Norton, who across numerous books made monsters that I loved in my childhood reading, but most particularly whatever it was that the archaeological machine in her sci-fi novel Catseye almost brought back from the past, its time shadow, as it were, enough to drive people insane . . . the hint of a monster and the effects of its presence as effective or perhaps even more effective than any description.

There are many more, of course, too many to list or for my jetlagged mind to immediately produce. These books, and others, provided me with something of an apprenticeship in monster-making, and of course began to equip my mind with the tools for storytelling in general.

But in addition to my reading, something else helped me along in my monster-making endeavours. When I was twelve years old, I saw in a games shop a small white box that contained three booklets named Men & Magic; Monsters & Treasure; and The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures. In other words, Dungeons and Dragons.

I already liked games, and had recently started playing miniature wargames, but these three booklets were a revelation to me, because they were about playing games that were fantasy stories, basically about being in a story. Within a day of reading the rulebooks I recruited five friends from school and we started playing. Perhaps because I’d bought the rules, I was the dungeonmaster, though I suspect it was more to do with my natural authorial tendencies that were already in evidence back then. I wanted to direct the story as much as be part of it.

Dungeons & Dragons, as required for game purposes, gave monsters characteristics. I could look up a creature in Monsters and Treasure and see its armour class, and hit dice, and its attacks values and so on. There was also a brief description, sometimes including special characteristics that were not easily handled by the games’ basic mechanics. In those early days, these characteristics and game mechanics were far simpler than they later became, but in some ways I think that was useful because it gave more leeway to me as a dungeonmaster to use the creatures in my own way and I am glad that even at twelve, I fully took on that the three booklets were a skeleton structure to make something of one’s own, not a restrictive or exhaustive set of rules.

This was made explicit by D&D authors Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, but even so, some players and dungeonmasters treated the rules as set in stone.

To me, and most other players, the open nature of D&D and later role-playing games provided enormous scope to develop our own adventures, and one of the main parts of this was, of course, developing new monsters beyond those in the original rulebooks and later supplements (of which there would be a veritable plethora, continuing to this day).

I first started by adapting monsters that weren’t in the rule books, taking monsters and creatures out of my favourite books and working out their characteristics in D&D terms. What I didn’t realize back then, though, was that one of the primary reasons these monsters would work in a role-playing game adventure wasn’t because I’d got their game attributes right, it was because they were already so well-defined and real from the stories I’d got them from (which the players had invariably read as well), so the mere mention of some distinguishing part of their appearance or behavior would lead to the players knowing what they were up against, with the consequent emotional impact derived from the shared experience of the story.

I guess what I’m saying here is that you can work out all the mechanistic details of a creature and its description and so on, as if defining it for a game or an encyclopedia or some data file, but this does not make it come alive and does not make it feel real to either roleplayers or readers. What does do this is story, and the monster’s place in it. In fact, as in Catseye I mentioned above (and in many horror stories), it is quite possible that never actually describing or detailing a monster might make it all the more effective. A reader needs to be provided with just enough information (which might be overt description, it might be character’s reactions to the creature, it might be dialogue, it might be mere allusion) to enable them to imagine the creature themselves, and whatever the reader thinks up themselves will be invariably more terrifying and effective than a huge amount of text from the author.

So, my apprenticeship in monster-making began with reading and continues to this day with reading; later to be enhanced by the once-a-week D&D sessions I ran for a good part of my teenage years; and then continued with writing, as I began to want not just to read stories, and co-create them in an RPG environment, but also to make stories that were my own.

Many fantasy writers begin with their worlds, working them out in a great deal of detail, and often this will include the creation and development of creatures. Sometimes they will be entirely original, sometimes they will be drawn from myth or legend, and sometimes they will be orcs from Tolkien. (Orcs are a very invasive species, it seems, given their ability to infest so many different fantasy books. Sometimes they are called something different, though we all know “that which we call an orc by any other name would smell as foul.”)

Developing the world first is a very effective technique, one adopted by many great writers, but it’s not one that I follow. I tend to discover my fantasy world as I go along, I only work out what I need for the story as I need it, and this also applies to creatures.

So from my very earliest stories, I would be writing away and then all of a sudden I would need a monster, and as I said at the very beginning of this piece, I would usually find one waiting in my head. Or at least the beginnings of one, often just a sense of what kind of feeling I want to evoke with that creature, or perhaps some minor point of physical description. And there I will pause for a while, sometimes for a few minutes, sometimes for a few days, while the necessary minimum I need to know about that monster rises to my conscious and can be used in the story. I say the necessary minimum because as I’ve mentioned above, I don’t want to give too much to the reader, I want to supply the catalyst for their imagination to finish creating the monster for themselves.And now, because I am writing this while on tour for Goldenhand, I’m afraid I must away. Perhaps appropriately to New York Comic Con, where I will see depictions of many monsters, but not I trust, encounter any real monsters lurking within. Which leads to a closely related topic: about how humans are the real monsters . . .

Garth Nix, October 2016

Published on October 08, 2016 08:11

September 15, 2016

Be bold, be bold! (But not too bold.)

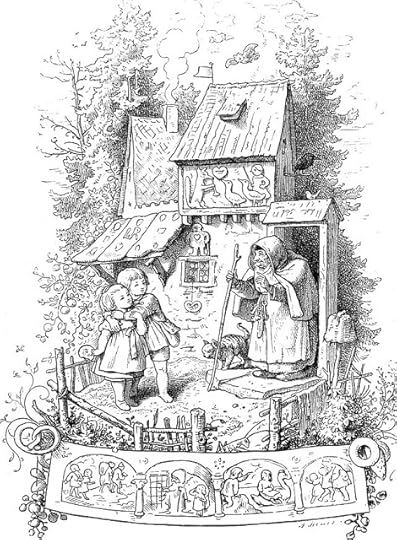

People often assume there aren’t very many English fairy tales. There are, of course, but they were eclipsed in popularity by the much better-known German and French tales of the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault. During the 19th century the English were, on the whole, keener on translating other peoples’ fairy tales than collecting their own: possibly (as I say in another place) because the Europe-wide fashion for collecting traditional tales was driven by nationalism, and Victorian Englishmen didn’t feel they had anything much to prove. So generations of English children grew up knowing about Rumpelstilskin and Cinderella, and nothing about Tom Tit Tot and Ashie-Coat.

It took an Australian Jew, Joseph Jacobs, to notice this and do something about it. ‘Who says that English folk have no fairy-tales of their own?’ he asks in the introduction to his 'English Fairy Tales’, 1898. ‘The present volume contains only a selection out of some 140, of which I have found traces in this country. It is probable that many more exist.’ One of those tales is an all-time favourite of mine, ‘Mr Fox’. It’s the oldest known version of the ‘Bluebeard’ story, and I wrote about it in my recent book ‘Seven Miles of Steel Thistles’, where I explain why I think it’s about a million times better than ‘Bluebeard’. It’s about a girl called Lady Mary who becomes curious – maybe even suspicious – when her fiancé, the suave Mr Fox, is unwilling to let her visit his castle. So when he announces he has to go away for a day just prior to their wedding, she sets off deep into the woods to find the place for herself.

And there it is, a beautiful castle: but above the gateway a strange motto is carved into the stone: ‘Be bold, be bold’. Lady Mary passes under the gateway and into the courtyard. The place is quite empty, not a soul anywhere about. Crossing the yard to the the doorway of the keep, she finds the same motto again, this time longer: ‘Be bold, be bold, but not too bold’. On she goes:

Still she went on till she came into the hall, and went up the broad stairs till she came to a door in the gallery, over which was written:

Be bold, be bold, but not too boldLest that your heart’s blood should run cold.

But Lady Mary was a brave one, she was, and she opened the door, and what do you think she saw? Why bodies and skeletons of beautiful young ladies all stained with blood. So Lady Mary thought it was high time to get out of that horrid place…

As she hurries down the stairs she sees Mr Fox himself coming into the hall, dragging a beautiful young woman behind him who seems to have fainted. Lady Mary hides behind a cask, and witnesses Mr Fox cutting off the young woman’s hand:

Just as he got near Lady Mary, Mr Fox saw a diamond ring glittering on the finger of the young lady he was dragging, and he tried to pull it off. But it was tightly fixed … so Mr Fox cursed and swore, and drew his sword, raised it, and brought it down upon the hand of the poor lady. The sword cut off the hand, which jumped into the air, and fell of all places into Lady Mary’s lap. Mr Fox looked about a bit but did not think of looking behind the cask, so at last he went on dragging the young lady up the stairs into the Bloody Chamber.

Lady Mary runs home, but that’s not the end. Next day this self-possessed and steely heroine meets Mr Fox at a splendid family breakfast where the contract of their marriage is to be signed. ‘How pale you are this morning, my dear,’ exclaims Mr Fox.

‘Yes,’ said she, ‘I had a bad night’s rest last night. I had horrible dreams.’‘Dreams go by contraries,’ said Mr Fox; ‘but tell us your dream, and your sweet voice will make the time pass till the happy hour comes.’‘I dreamed,’ said Lady Mary, ‘that I went yestermorn to your castle, and I found it in the woods, with high walls and a deep moat, and over the gateway was written: Be bold, be bold.’‘But it is not so, nor it was not so,’ said Mr Fox.

As Lady Mary continues and the mottoes intensify their warnings, so Mr Fox’s denials become stronger: ‘It is not so and it was not so. And God forbid it should be so’ – till finally Lady Mary springs to her feet.

‘It is so and it was so. Here’s hand and ring I have to show,’ and pulled out the lady’s hand from her dress and pointed it straight at Mr Fox. At once her brothers and her friends drew their swords and cut Mr Fox into a thousand pieces.

This is a great story with a brave, intelligent heroine, and it’s beautifully structured. I’ve told it aloud many times to children and they always love it. But where did Joseph Jacobs find it? Well, he found it as an addendum to Edmond Malone’s 1790 edition of the complete works of Shakespeare ( ‘Malone’s Variorum Shakespeare’).

This of course isn't the original 1790 edition, which I couldn't find, but from 1821.

This of course isn't the original 1790 edition, which I couldn't find, but from 1821. There’s a bit in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ Act I, Sc 1, where Benedick says to Claudio: ‘Like the old tale, my lord: it is not so, nor ‘twas not so; but, indeed, God forbid it should be so.’ A certain Mr Blakeway contributed a note to explain this reference:

I believe none of the commentators have understood this; it is an allusion, as the speaker says, to an old tale, which may perhaps still be extant in some collections of such things, or which Shakspeare may have heard, as I have, related by a great aunt, in his childhood.

Mr Blakeway then recounts the whole tale, though with less artistry than Joseph Jacobs: he’s supplying a note, after all, not writing a story:

Over the portal of the hall was written: ‘Be bold, be bold, but not too bold:’ she advanced: over the stair-case, the same inscription: she went up: over the entrance of a gallery, the same: she proceeded: over the door of a chamber, – ‘Be bold, be bold,but not too bold, lest that your heart’s blood should run cold.’ She opened it; it was full of skeletons, tubs of blood, &c. She retreated in haste…

Blakeway concludes,

Such is the old tale to which Shakspeare evidently alludes, and which has often ‘froze my young blood’ when I was a child. I will not apologize for repeating it, since it is manifest that such old wives’ tales often prove the best elucidation of this writer’s meaning.

John Brickdale Blakeway was born in Shrewsbury in 1765, the eldest son of Joshua Blakeway and Elizabeth Brickdale. He studied law, was ordained in 1793, became a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1807 and died in 1826. His great-aunt probably told young John this tale when he was about ten, and she must have heard it in her own childhood some time between say 1710 and 1725. This is still over a century since Shakespeare’s death, but the story happens to be one which is very easy to remember, full of repetition – the tale is actually told twice – and memorable phrases. (I’ve known children who could tell it well having heard it only once.) In 1598 Shakespeare’s Benedick quotes one of these phrases:‘It is not so and it was not so and God forbid it should be so’, and calls it an ‘old tale’.

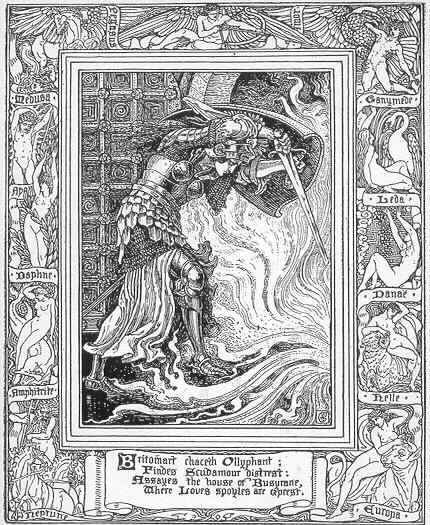

Edmund Spenser’s immensely long narrative poem ‘The Faerie Queene’, references the other quotable quote from 'Mr Fox' in Book 3, Canto XI, verses 50 to 54: when the gallant ‘warlike Maid’ Britomart (allegorically Chastity) is exploring the House of Busirane (the House of Violence and Lust) to find and rescue the enchanter Busirane’s tortured victim Amoret. As Britomart makes her way through room after room decorated with pictures and tapestries of ravished women (and one boy), she notices something else:

Over the door thus written she did spyBe bold: she oft and oft it over-read…

Just like Lady Mary, Britomart is not dismayed - ‘But forward with bold steps into the next room went’. And just as in ‘Mr Fox’, the castle is silent and empty - ‘Strange thing it seemed’! Eventually,

…as she looked about, she did beholdHow over that same door was likewise writBe bold, be bold, and everywhere Be bold,That much she mazed, and could not construe itBy any riddling skill or common wit.At last she spied at that room’s upper end,Another iron door, on which was writ,Be not too bold…

The first three books of ‘The Faerie Queene’ were published in 1596. This therefore appears to be the earliest reference to the ‘old tale’ of ‘Mr Fox’. It must once have been very well known. But if John Blakemore hadn’t written it down, it would have disappeared. His account is the only complete source for this English fairy tale.

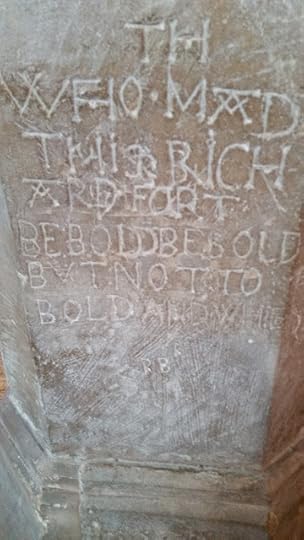

I was talking about all this this recently with a good friend, the author John Dickinson (who writes wonderful fantasy and sci-fi): in fact it was he who pointed me in the direction of ‘The Faerie Queene’. He electrified me by telling me that in his local church of St Mary in Painswick, Gloucestershire, the words ‘Be bold, be bold’ are actually cut into one of the pillars. Local tradition has it that the words were carved by one of a group of Parliamentarian soldiers besieged in the church during the English Civil War, and that they are a quotation from ‘The Faerie Queene’. I was so excited about this that John invited me to come over and see the inscription. And here it is.

TH. WHO. MADTHIS. RICHARD FORTBE BOLD BE BOLDBUT NOT TOBOLD AND WHE

RB

Let’s take the first bit first. In modern spelling: ‘THOU WHO MADE THIS RICHARD FORT BE BOLD BE BOLD BUT NOT TOO BOLD’. Some man named Richard Fort is addressing God (who ‘made’ him) and adding an – appeal? a prayer? a command? a warning? – perhaps to God, perhaps to himself, to ‘be bold, be bold, but not too bold.’

Painswick Church was indeed besieged in the year 1644. There’s an account in ‘A Cotteswold Manor; being the history of Painswick’ written by the wonderfully named Welbore St Clair Baddeley and published in 1907. In 1644 the countryside around the city of Gloucester (which had survived a siege by Royalist forces the previous autumn) was in turmoil, with Royalists and Parliamentarians exchanging raids and committing atrocities on both sides. Enter the fearsome Colonel Mynne, leading a regiment of Royalist Catholic infantry raised in Ireland. Arriving in Bristol, Mynne and his men stormed their way across Gloucestershire and in February 1644 arrived at Painswick. The Parliamentarian Attorney General, Backhouse, quartered in Gloucester, writes:

‘We heard … that Colonel Mynne and St Leger with the Irish forces march’t to Painswicke for subsistence, but indeed to plunder the country, to prevent which, our Governor (Massey) drew out a party of Horse and Foot, where there was a skirmish and some losse on both sides.’

Whether this skirmish was successful or not, some time later Mynne’s Royalist forces withdrew and a garrison of Massey’s Parliamentarian troops moved into Painswick. In the back-and-forth of that wretched time, they were not to remain there long. The King’s man Sir William Vavasour marched on Painswick with ‘a strong brigade’ and two ‘culverins’ or light cannons. The Parliament soldiers, who had taken up a defensive position in a house near the church, were not strong enough to hold off anything much bigger than a plundering party, and had been told to make good their retreat down the steep hill towards Brookthorp if the Royalist force was substantial. But the lieutenant commanding them, ‘… not understanding the strength of the (opponents) army’ and encouraged by ‘many willing people of the neighbourhood in that weak hold’, instead of withdrawing, remained to fight. Finding himself overwhelmed ‘upon the first onset’, he deserted the house and took his men into the church. It was a move from the frying pan into the fire: the Royalists burned down the door and threw ‘hand-granadoes’ into the church where ‘some few were slain in defending the place, and the rest taken prisoners.’ [This contemporary account is quoted in the ‘History of the Church of St Mary at Painswick’ by Welbore St Clair Baddeley, 1902]