Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 17

November 25, 2017

"It's not just an [insert genre] book..."

I'm still engaged in writing the next book, so here's one from the archives - from three years ago. Still relevant though.

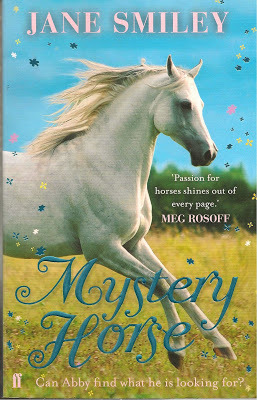

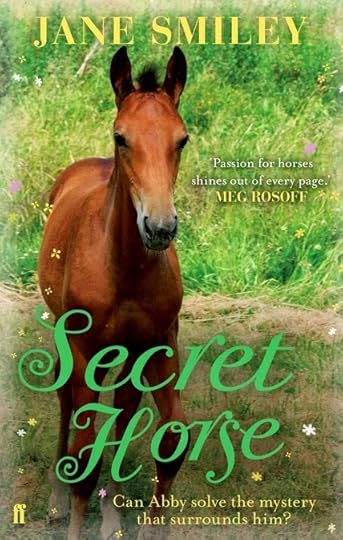

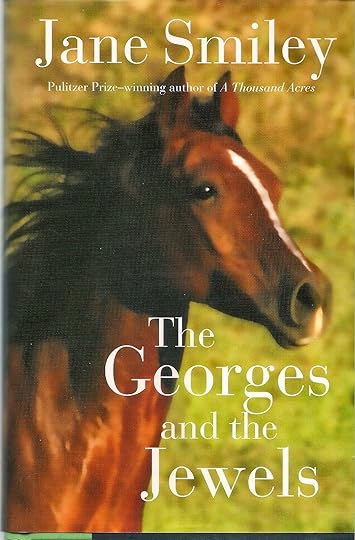

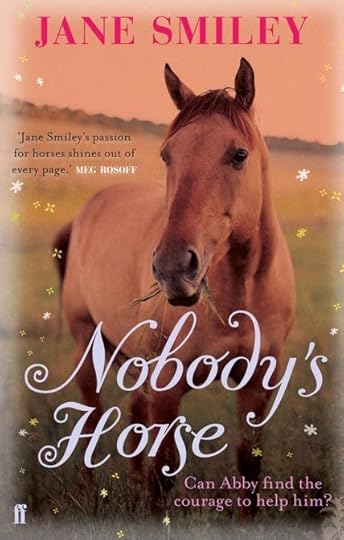

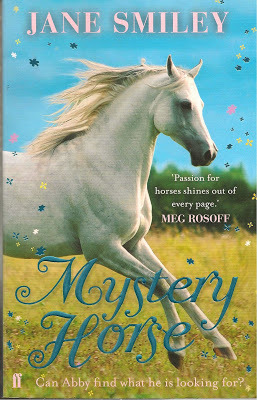

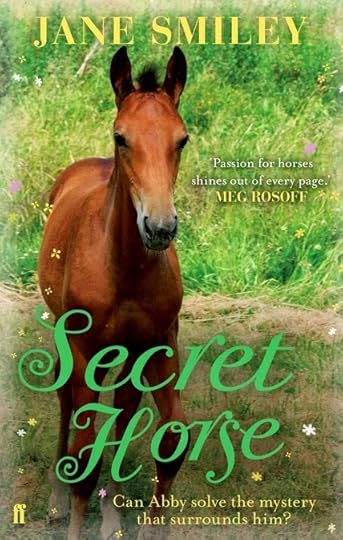

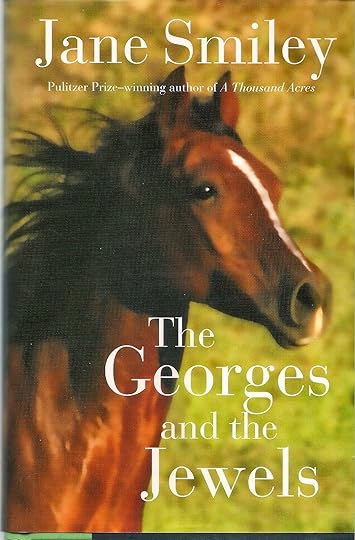

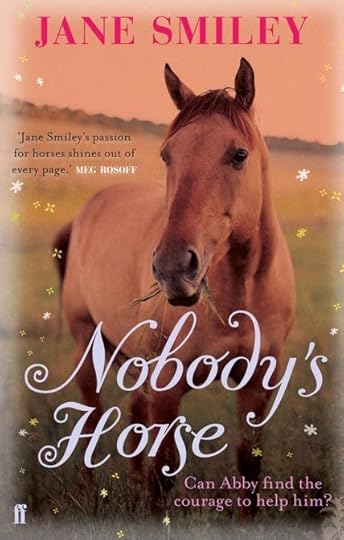

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. (If not remaindered, the deal is a disgraceful one.) I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and the selections here are often more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this: It’s the third in a series of horse books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. I do wish same-language publishers would keep to original titles, but Faber & Faber in the UK has changed them to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’, and in the process has designed covers that practically guarantee no-one except pony fanatics will ever read them. The US covers are way classier. But that's publishers for you. And who knows if any of them sold well? I mean, take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' –‘True Blue’ in the States – the gorgeous galloping white horse against the blue sky, with its blue foil title and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. But then, well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story.

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. (If not remaindered, the deal is a disgraceful one.) I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and the selections here are often more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this: It’s the third in a series of horse books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. I do wish same-language publishers would keep to original titles, but Faber & Faber in the UK has changed them to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’, and in the process has designed covers that practically guarantee no-one except pony fanatics will ever read them. The US covers are way classier. But that's publishers for you. And who knows if any of them sold well? I mean, take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' –‘True Blue’ in the States – the gorgeous galloping white horse against the blue sky, with its blue foil title and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. But then, well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/coverSet in 1960’s California, the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row. Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s independence. In the meantime Abby begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

UK title/coverSet in 1960’s California, the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row. Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s independence. In the meantime Abby begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/coverAnd YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are pretty much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse: “I think they [the boys] are like Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack, it wouldn’t make him stop running. It would make him run faster. If we whipped Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home. As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and ultimately all about Abby, so that the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra thrill.As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which – because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.‘“You built a Catholic mission?” “We all did.”’ It’s done with a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different. I love all of this. But would a child? Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post comes in. Genre fiction has an undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels. Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel. ‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s just a school story. ‘It’s just a romance.’

UK title/coverAnd YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are pretty much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse: “I think they [the boys] are like Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack, it wouldn’t make him stop running. It would make him run faster. If we whipped Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home. As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and ultimately all about Abby, so that the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra thrill.As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which – because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.‘“You built a Catholic mission?” “We all did.”’ It’s done with a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different. I love all of this. But would a child? Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post comes in. Genre fiction has an undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels. Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel. ‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s just a school story. ‘It’s just a romance.’

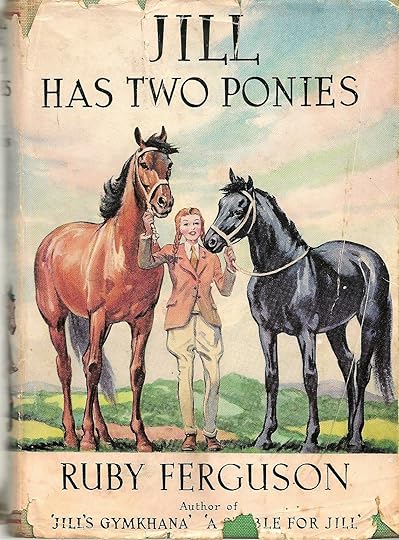

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.But there are books which do more, which are multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and ‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’ books don’t have and never aspired to. KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’, Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion, censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to persons they dislike.

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.But there are books which do more, which are multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and ‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’ books don’t have and never aspired to. KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’, Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion, censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to persons they dislike.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brothers, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important. Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored, impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader more than they expected. Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea. The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it, then what is left? Every category of books – novels, children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula Le Guin’s books aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to Le Guin? She chose to employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy. That is where she belongs. All it really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a book belonging to a genre which they believe – in spite of the evidence before their eyes – to be second-rate. Either we need to do away with categories and genres altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s books. Their excellence is no different in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses, and about life.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brothers, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important. Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored, impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader more than they expected. Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea. The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it, then what is left? Every category of books – novels, children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula Le Guin’s books aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to Le Guin? She chose to employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy. That is where she belongs. All it really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a book belonging to a genre which they believe – in spite of the evidence before their eyes – to be second-rate. Either we need to do away with categories and genres altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s books. Their excellence is no different in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses, and about life.

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. (If not remaindered, the deal is a disgraceful one.) I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and the selections here are often more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this: It’s the third in a series of horse books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. I do wish same-language publishers would keep to original titles, but Faber & Faber in the UK has changed them to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’, and in the process has designed covers that practically guarantee no-one except pony fanatics will ever read them. The US covers are way classier. But that's publishers for you. And who knows if any of them sold well? I mean, take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' –‘True Blue’ in the States – the gorgeous galloping white horse against the blue sky, with its blue foil title and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. But then, well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story.

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. (If not remaindered, the deal is a disgraceful one.) I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and the selections here are often more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this: It’s the third in a series of horse books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. I do wish same-language publishers would keep to original titles, but Faber & Faber in the UK has changed them to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’, and in the process has designed covers that practically guarantee no-one except pony fanatics will ever read them. The US covers are way classier. But that's publishers for you. And who knows if any of them sold well? I mean, take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' –‘True Blue’ in the States – the gorgeous galloping white horse against the blue sky, with its blue foil title and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child would want it. But then, well, then they might find this is more than your average pony story.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/coverSet in 1960’s California, the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row. Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s independence. In the meantime Abby begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

UK title/coverSet in 1960’s California, the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row. Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s independence. In the meantime Abby begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

US title/cover

US title/cover

UK title/coverAnd YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are pretty much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse: “I think they [the boys] are like Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack, it wouldn’t make him stop running. It would make him run faster. If we whipped Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home. As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and ultimately all about Abby, so that the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra thrill.As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which – because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.‘“You built a Catholic mission?” “We all did.”’ It’s done with a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different. I love all of this. But would a child? Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post comes in. Genre fiction has an undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels. Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel. ‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s just a school story. ‘It’s just a romance.’

UK title/coverAnd YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley suggests, are pretty much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse: “I think they [the boys] are like Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack, it wouldn’t make him stop running. It would make him run faster. If we whipped Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home. As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and ultimately all about Abby, so that the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra thrill.As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which – because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.‘“You built a Catholic mission?” “We all did.”’ It’s done with a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different. I love all of this. But would a child? Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post comes in. Genre fiction has an undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels. Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel. ‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s just a school story. ‘It’s just a romance.’

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.But there are books which do more, which are multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and ‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’ books don’t have and never aspired to. KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’, Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion, censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to persons they dislike.

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.But there are books which do more, which are multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and ‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’ books don’t have and never aspired to. KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’, Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion, censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to persons they dislike.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brothers, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important. Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored, impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader more than they expected. Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea. The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it, then what is left? Every category of books – novels, children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula Le Guin’s books aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to Le Guin? She chose to employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy. That is where she belongs. All it really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a book belonging to a genre which they believe – in spite of the evidence before their eyes – to be second-rate. Either we need to do away with categories and genres altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s books. Their excellence is no different in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses, and about life.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’ than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’. Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brothers, much as they loved each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important. Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored, impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader more than they expected. Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea. The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it, then what is left? Every category of books – novels, children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula Le Guin’s books aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to Le Guin? She chose to employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy. That is where she belongs. All it really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a book belonging to a genre which they believe – in spite of the evidence before their eyes – to be second-rate. Either we need to do away with categories and genres altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s books. Their excellence is no different in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses, and about life.

Published on November 25, 2017 14:28

November 17, 2017

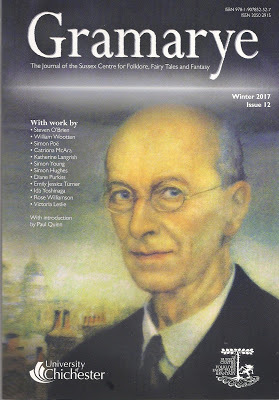

Gramarye

I am delighted to be in the new issue of GRAMARYE, the journal of the Sussex Folklore Centre and as usual an unmissable read for folk lore and fairy tale enthusiasts.This issue contains three marvellous articles on Arthur Rackham - whose self portrait adorns the cover. In 'A Walk Through Rackham Land,' Steven O'Brien takes us on a ramble through the deep history of the artist's beloved Sussex countryside. William Wootten tells how Rackham's silhouettes inspired his own verse narrative of The Sleeping Beauty, and Simon Poë interestingly compares Rackham's illustrations to 'Puck of Pook's Hill' with those of H.R. Millar. Catriona McAra contributes an article on fairy references in the work of the surrealist Leonora Carrington, while in 'Herne, the Windsor Bogey', Simon Young takes us into Windsor Great Park on a search for the controversial history of the great oak-tree of Herne the Hunter. 'The Signing Wife' is an original translation by Simon Hughes of a thought-provoking Norwegian folktale collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen. Finally, Diane Purkiss adds a touching and lyrical account of her childhood love for Andersen's story 'The Snow Queen'.

My own contribution is an analysis of the Grimms' fairytale 'MAID MALEEN':

Here's a little taster:

Maid Maleen (Kinder- und Hausmärchen, tale 198) isn’t particularly popular as fairy tales go. It was first published as Jungfer Maleen by Karl Müllenhoff in a collection called Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzoghümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg (1845), from whence the Grimms borrowed it for the 1850 edition of their Kinder- und Hausmarchen. I don’t know whether Müllenhoff wrote it down verbatim from some oral source: he may have touched it up, but the Grimms made several slight but significant changes to his version, transforming it into a fairy story that delves unusually deeply into the trauma caused by abandonment and suffering. ...

Why do I love this story so much? Isn’t it just another tale of a passive princess sitting in a tower? In fact there aren’t so very many stories of princesses shut up in towers, and those that do exist are less like the stereotype than you might suppose. As Maid Maleen does, heroines quite often rescue themselves. Even in the case of Rapunzel (KHM 12) the prince not only fails to rescue Rapunzel, but wanders blind in the desert until he is saved by her. In Old Rinkrank (KHM 196), a princess trapped in a glass mountain ultimately tricks her captor, and engineers her own escape. [...] These tales are listed in the Aarne-Thompson folk-tale index as tale type 870: The Entombed Princess or The Princess Confined in the Mound – though this description, as Torborg Lundell has pointed out, is hardly adequate. Instancing The Finn King’s Daughter, another tale in which an imprisoned heroine digs herself out from underground and rescues her lover from the false bride, Lundell writes:

Consistent with the Aarne and Thompson downplay of female activity, this folktale type, with its aggressive and capable female protagonist, has been labelled ‘The princess confined in the mound’ (type 870), which implies a passivity hardly representative of the thrust of the tale. ‘The princess escaping from the mound’ would fit better...

GRAMARYE issue 12 can be ordered for £5.00 from the Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy by following this link: http://www.sussexfolktalecentre.org/journal/

Published on November 17, 2017 04:21

October 26, 2017

Folklore Snippets: The Tailor and the Corpse

I love this story partly because it's such a good one to tell aloud - and also because the hero is one of those impudently brave tailors who turn up so often in fairy tales and folk tales. I think tales about tailors must have been so popular because the little, crooked-legged, short-sighted tailor was, like Mr Bilbo Baggins, such an incongruous hero: a little, ordinary chap who could best giants, bulls, boars and unicorns - and in this tale, a terrible revenant of the Norse type - a draug or animated corpse.

From: Highland Fairy Legends, collected from oral tradition by the Rev James MacDougall (1910)

A tailor once, living on the farm of Fincharn, near the south end of Loch Awe, having denied the existence of ghosts, was challenged by his neighbours to prove his sincerity by going at the dead hour of midnight to the burying place at Kilnure and bringing back with him the skull lying in the window of the old church that gives its name to the place. The tailor replied that he would give them a stronger proof even than that, by sewing a pair of trousers in the church between bed-time and cock-crow that very night.

They took him at his word and, as soon as ten o’clock came, the tailor entered the old church, seated himself on a flat grave-stone resting on four pillars, and, after placing a lighted candle beside him, he began his tedious task. The first hour passed quietly enough while he was sewing away and keeping up his heart singing and whistling the cheeriest airs he could think of. Twelve o’clock also passed, and yet he neither saw nor heard anything to alarm him in the least.

But sometime after twelve he heard a noise coming from a gravestone which was between him and the door, and on casting a side-look in that direction he thought he saw the earth heave under it. The sight at first made him wonder, but he soon came to the conclusion that it was caused by the unsteady light of the candle in the dark. So, with a hitch and a shrug, he returned to his work and sewed and sang as cheerily as ever.

Soon after this a hollow voice, coming from under the same stone, said: “See the great, mouldy hand, and it so hungry looking, tailor.” But the tailor replied: “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he sang and sewed away as before.

After another while the same great hollow voice said, in a louder tone: “See the great, mouldy skull, and it so hungry looking, tailor.” But the tailor again answered, “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he sewed faster and sang louder than ever.

A third time the voice spoke, and said in a louder and more unearthly tone: “See the great, mouldy shoulder, and it so hungry looking, tailor.” But the tailor replied as usual, “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he plied the needle quicker and lengthened his stitches.

This went on for some time, the dead man showing next his haunch and finally his foot. Then he said in a fearful voice: “See the great, mouldy foot, and it so hungry looking, tailor.” Once more the tailor bravely answered: “I see that, and I will sew this.” But he knew that the time for him to fly had come. So, with two or three long stitches and a hard knot at the end, he finished his task, blew out the candle, and ran out at the door, the dead man following him and striking a blow aimed at him against one of the jambs, which long bore the impression of a hand and fingers.

Fortunately the cocks of Fincharn now began to crow, the dead man returned to his grave, and the tailor went home triumphant.

Art: Ruins of a Gothic Chapel by Moonlight, by Felix Kreutzer, 1835 - 1876

Published on October 26, 2017 05:02

October 5, 2017

The Terror of Trees

Ellum he do grieve,Oak he do hate,Willow do walkIf you travels late.

This old Somerset rhyme is quoted by KM Briggs in ‘The Fairies in Tradition and Literature’: she explains it thus: ‘The belief behind this is that if one elm tree is cut down the one next to it will die of grief: but if oaks were cut they will revenge themselves if they can. Willow is the worst of all, for he walks behind benighted travellers, muttering.’ I somehow imagine Tolkien knew a lot of tree-lore...

Elm used to be the wood coffins were made from, and elm trees had – before Dutch elm disease cleared them from England – a nasty reputation for dropping branches without warning. When I was a child two enormous elms grew on either side of the gate at the bottom of our field and for reasons I’ll explain later I was afraid of approaching them after dark.

Trees are beautiful, but can also be frightening and even dangerous. Trees, we know, are alive. When you cut them, they bleed. Maybe it hurts them? Then they may resent it. They have voices too, whispering secrets or roaring in anger. In ‘The Lore of the Forest’ Alexander Porteous writes, ‘In some districts of Austria forest trees are said to have souls, and to feel injuries done to them.’ In gales, trees become truly dangerous and frightening. Algernon Blackwood expresses this terror well near the end of a story, ‘The Man Whom The Trees Loved’:

The trees were shouting in the dark. There were sounds, too, like the flapping of great sails, a thousand at a time, and sometimes reports that resembled more than anything the distant booming of enormous drums. The trees stood up – the whole beleaguering host of them stood up – and with the uproar of their million branches drummed the thundering message out into the night. It seemed as if they had all broken loose. Their roots swept trembling over field and hedge and roof. They tossed their bushy heads beneath the clouds with a wild, delighted shuffling of great boughs. With trunks upright they raced leaping through the sky.

It behoves feeble humans to treat such creatures with care.

Elders are not tall or imposing trees – they are more like tall bushes – but they bleed so freely when cut, they are considered magical. Sometimes they themselves are witches. Christina Hole in ‘Haunted England’ gives a polite formula with which to address an elder before you attempt to cut it: “Old Gal, give me of thy wood, and I will give thee some of mine, when I grow into a tree.” In other tales, elders protect against witchcraft. (Perhaps on the principle, set a thief to catch a thief?)

Ash trees too could have a bad reputation. This may possibly be something to do with medieval demonising of the old Nordic mythology in which the Ash is Yggdrasil, the World Tree. In George Macdonald’s adult fairy novel ‘Phantastes’, the hero Anodos is warned by his hostess and her daughter to avoid the evil Ash, whose shadow threatens the fairy cottage in which he is sheltering.

‘Look there!’ she cried,‘look at his fingers!’ The setting sun was shining through a cleft in the clouds piled up in the west; and a shadow, as of a large distorted hand, with thick knobs and humps on the fingers … passed slowly over the little blind.

‘He is almost awake, mother; and greedier than usual tonight.’

‘Hush, child! You need not make him more angry with us than he is; for you do not know how soon something may happen to oblige us to be in the forest after nightfall.’

In Alison Uttley’s fictionalised autobiography, ‘A Country Child’ she describes how an ash tree tried to kill her. There was a swing fixed in it, where the child ‘Susan’ sat, swaying to and fro and looking out at the countryside.

Then Susan heard a tiny sound, so small that only ears tuned to the minute ripple of grass and leaf could hear it. It was like the tearing of a piece of the most delicate fairy calico, far away… An absurd, unreasoning terror seized her. The Things from the wood were free. She sat swinging, softly swinging, but listening, holding her breath, always pretending she did not care. Her heart’s beating was much louder than the midget rip,rip, rip, which wickedly came from nowhere... A voice throbbed in her head, ‘Go away, go away, go away,’ but still she sat on the seat, afraid of being afraid.

Then aloud, to show Them she was not frightened, she sighed and said, ‘I am so tired of swinging, I think I will go,’ and she slid trembling off the seat and walked swiftly away…Immediately the rip grew to a thunder like a giant hand tearing a sheet in the sky, and the whole enormous bough fell with a crash which sent echoes round the hills. The oaken seat of the swing was broken to fragments, and the great chains bent and crushed.

Even on a still, hot day a forest can be an awe-inspiring place, and those who walk or work within it may not be entirely comfortable. In the deep north-east woods of Canada, sometimes you may hear the sound of an axe chopping, in a distant glade where no one should be, and wonder… This may be Al-wus-ki-ni-kess, the unseen woodcutter of the Passamaquoddies. Or in winter, the terrible jenu of the Mi’kmaq may come running through the frozen forest: a human driven mad by famine who has turned into a cannibal monster with a heart of ice.

What about those elm trees in my childhood home? Why did they scare me? Well, I was thirteen and I’d been reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s book of his travels in Polynesia, ‘In the South Seas’. Here I found a passage which raised the hairs on my head. It’s the experience of a young man called Rua-a-mariterangi, on the island of Katui, who was on the forest margin of the beach looking for pandanus (a fruit which looks a bit like a pineapple).

The day was still, and Rua was surprised to hear a crashing sound among the thickets, and then the fall of a considerable tree.

Thinking it must be someone felling a tree to build a canoe, Rua went deeper into the wood to have a chat with this presumed neighbour, when:

The crashing sounded more at hand, and then he was aware of something drawing swiftly near among the tree-tops. It swung by its heels downward, like an ape, so that its hands were free for murder; it depended safely by the slightest twigs; the speed of its coming was incredible, and soon Rua recognised it for a corpse, horrible with age, its bowels hanging as it came. Prayer was the weapon of Christian in the Valley of the Shadow, and it is to prayer that Rua-a-mariterangi attributes his escape. This demon was plainly from the grave; yet you will observe he was abroad by day. … I could never find another who had seen this ghost, diurnal and arboreal in its habits; but others have heard the fall of the tree, which seems the signal of its coming. Mr Donat was once pearling on the uninhabited island of Haraiki. It was a day without a breath of wind… when, in a moment, out of the stillness, came the sound of the fall of a great tree. Donat would have passed on to find the cause. ‘No,’ cried his companion, ‘that was no tree. It was something NOT RIGHT. Let us go back to camp.’ Next Sunday … all that part of the isle was thoroughly examined, and sure enough no tree had fallen.

This was quite enough for me. Every time I had any reason to walk down after dusk, or at night, towards those two towering elm trees, and pass under the sighing, billowing darkness of their foliage, a creepiness stole down my spine and I could imagine all too clearly a decomposing corpse, swinging down out of the leaves to shove its upside-down face into mine.

Oh yes. Trees can be terrifying. Have you any stories to tell?

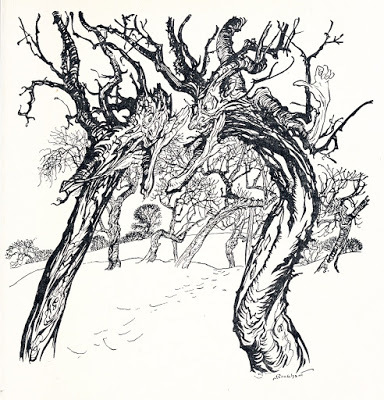

Picture credits:

Theodore Kittelsen: 'Into the Woods'

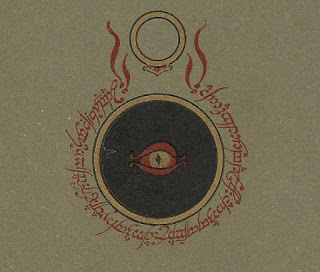

Arthur Rackham: Trees: from 'A Dish of Apples' by Eden Philpotts

Theodore Kittelsen: 'The Forest Troll'

Theodore Kittelsen: 'Creepy, Crawly, Bustling, Rustling'

Arthur Rackham: Black Cat: from 'Grimms Fairytales'

Published on October 05, 2017 01:14

September 12, 2017

A Conversation about Fairytales (1)

This is the first of two Youtube interviews at the Greystones Press, in which Mary Hoffman, my fellow-writer, publisher and friend, asks me some questions about fairy tales and my book Seven Miles of Steel Thistles which was published by Greystones last year (and longlisted for the Katharine Briggs Award 2016). I provide a rough transcript, below.

Mary: What was the first fairy tale you can remember?

Katherine: Probably Briar Rose, aka the Sleeping Beauty. I’d be about seven or eight and was sent to read the story of Briar Rose to the headmistress of my little school. Her office was quiet and filled with sunshine, and through the window I could see into a rose garden which only the teachers were allowed to use – so a secret garden filled with roses... I’ll never forget the still, special feeling of standing there reading aloud about the castle falling asleep and the roses twining up the walls.

And to me it doesn’t matter that ‘all she does is sleep’. That story isn’t about people – not all stories have to be about people. For me, a child, I was entranced by the notion that time could stop. That’s what the story tells, it’s a distillation of a particular feeling, the feeling you can get as a child (or if you’re very lucky as an adult) when you’re so engrossed in the world that a sunny hour can last for ever. Time is a mystery, wreathed in thorns and roses. That’s what that story said to me.

Mary: Why do fairytales matter in the 21st century?

Katherine: You might as well ask ‘what does the 21st century matter to fairytales?’ People have been telling and retelling fairytales for centuries, quite probably for millennia, and they certainly aren’t going away! In fact they show no sign of doing so. You’ve only got to look at what Hollywood is doing. In the last few years we’ve had Frozen, Tangled, Maleficent, Into the Woods, Beauty and the Beast, Snow White and the Huntsman… and so on. Though I do wish the studios would move beyond that one quite tiny handful of popular tales…

There will always be people who don’t like them. But I think there are modern adults who don’t quite understand them. Fairy tales are a particular form, with their own rules. Like a sonnet. You don’t blame a sonnet for not being an epic. In the same way, a fairy tale is never going to be like a novel. You mustn’t expect ‘realistic’ characters who change and develop. Fairytale characters don’t change. Fairytale characters are more like archetypes. They often don’t even have names. They’ll be ‘the king’s daughter’, ‘the king’s son’, ‘the lad’, ‘the child’, ‘the maiden’. If they are named, the names will be really common ones, like Hans and Jack, Kate and Gretel. This is to keep them impersonal. They are everyman and everywoman: they are us.

Some might think, well how can I identify with a princess? In fact the bareness and simplicity of the form make it easy. ‘Princess’ is just a starting point for an adventure; and many of the heroes and heroines aren’t royal at all. They’re peasants and tradesmen, farmers and beggars and pensioned-off soldiers, and as I say in ‘Seven Miles of Steel Thistles’:

‘If you think about it for a moment, the world is still full of peasants and tradesmen and farmers and beggars and pensioned-off soldiers. Just as it always was.’

Mary: Isn't there an argument that fairytales are rather sexist - that fairytale princesses are poor role models?

Katherine: Well, there’s a persistent misconception that fairy-tale heroines are passive. I remember hearing a discussion a couple of years ago on Radio 4 which dismissed the entire genre as projecting images of insipid princesses whose role is to lie asleep in towers waiting for princes to rescue them with ‘true love’s kiss’.

I think this is because a lot of people who may not have read a fairy tale in years remember the small handful they came across as children, remember Snow-White in her glass coffin and Cinderella weeping in the ashes, and assume they stand for all.

In fact, women and girls in fairytales are often very active; the majority of heroines in the Grimms’ tales are the chief agents in their own stories. They rescue brothers and sweethearts, they save themselves or their fathers or their sisters. It’s partly that these stories aren’t nearly so well known (possibly reflecting early 20th century editorial choices) and partly that the stories themselves aren’t always well understood.

In spite of the Disney song ‘One day my prince will come’, ‘Snow-White’ is not a love story. It’s a tale of a cruel queen, a lost child, a dark forest, a magic mirror. The arrival of the prince at the end is no more than a neat way to wrap the story up.

If we approach fairy tales expecting nothing but sexist stereotypes, we will miss the irony, the inflections, we won’t get the jokes.

In Grimms’ ‘The Twelve Huntsmen’, a princess dresses herself and eleven ladies-in-waiting as huntsmen and goes to work for her lover, a king who has promised his dying father to marry a different woman. This king has a talking lion. The lion suspects the twelve young huntsmen of being women. He sets several traps to get them to betray themselves – such as an array of twelve spinning wheels which he assures the king these ‘women’ will be unable to resist. Remember, this is a story which was once told aloud in mixed company, and that spinning was a woman’s repetitive, endless work. It’s as if, in a modern version, the lion had set out a line of twelve vacuum cleaners. Readers who take this at face value are missing the comedy of the princess’s satirical aside to her followers as they stride past: ‘Hold back, control yourselves, don’t give those spinning wheels a glance…’ This is a story which directs sly humour at male assumptions about female ability. If we fail to notice when a story is inviting us to laugh, it’s we who are naïve.

Mary: What drew you to write the blog Seven Miles of Steel Thistles, which led to the book of the same title?

Katherine: I started the blog in 2009 as a way of starting a dialogue with other writers and readers of fairy tales, folklore and fantasy – all of which which I’ve loved since childhood. The name of the blog and title of the book comes from an Irish fairytale ‘The King Who had Twelve Sons’ in which the hero rides his pony over ‘seven miles of hill on fire and seven miles of steel thistles and seven miles of sea.’ (I have much more to say about that story in the book!)

Creating the blog has been a great experience. I’ve made many friends through it, both in this country and in the US and Australia, many wonderful writers have been contributed posts on their favourite fairy tales. I’ve learned a great deal through it, and have also had opportunities that wouldn’t have come my way without it, invitations to speak at conferences, for example, and to contribute essays and reviews to a number of academic or semi academic publications.

And then of course the Greystones Press suggested publishing the book!

Published on September 12, 2017 01:46

August 17, 2017

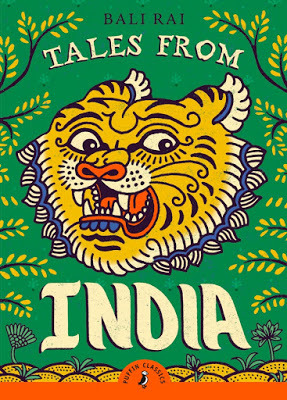

"Tales from India" - by Bali Rai

Wicked magicians, wise priests, handsome princes, beautiful princesses - along with greedy tigers and sly jackals. What's not to love? I'm delighted to welcome Bali Rai to the blog to talk about his new book of fairy tales and folk tales from India. Prepare for enchantment!

This collection came about after a lunchtime conversation. It was one of those casual, almost throwaway moments. As a British-born child of Indian parents, my knowledge of Asian folk tales was shamefully limited. Of course I knew the famous ones, but they were just the beginning. My parents never had the privilege of hearing such stories at school, because they never went to school. As a result, they had no way of passing these tales on to their children.

And in my British schools, the concept of Indian storytelling was almost non-existent. We were never taught about India’s rich folk tale heritage and ancient cultures (likewise China and Africa). Most of us didn’t realise that fairy tales and stories of talking animals existed in our parents’ traditions too. Folk tales, and stories generally, seemed to be a Western thing. It was as though we were being invited into a secret club, to which our ancestors had not previously belonged.

So when a casual idea became a concrete project, I had to discover India’s rich folk tale heritage as a beginner. I found amazing and often magical tales, full of adventure and trickery, and infused with deeper messages about morality, Life and the world around us. From wicked magicians to wise old priests, charming princes and beautiful princesses – every aspect of the Western tales I’d heard in childhood were present here, too.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect was how similar these Indian tales were to those of the Western tradition. Of particular interest were the Indian tales compiled by Joseph Jacobs (1854-1916). These were published in 1912, and form the basis for much of this collection. Punchkin immediately reminded me of Rumpelstiltskin, and many of the animal tales would find a happy home in Aesop or Kipling.

Of course, there are many differences, too. The Indian tales feel darker in places, and perhaps more moralistic too. Neither do they make allowances for the sensitivity or age of readers. Whilst ostensibly a children’s story, in The Peacock and The Crane the penalty for pride and boastfulness is death rather than a lesson well-learnt. Ditto any modern concepts of political correctness. There are helpless and passive princesses, and wizened old crones aplenty, not to mention heroes who seem only to relish the acquisition of material wealth. However, this tallies with their western counterparts, so perhaps I shouldn’t be too critical.

The rest of the collection comprises retellings of the Akbar and Birbal tales from India’s Mughal period, and other gems that I discovered in passing. Better known than most other Indian tales and widely read in the sub-continent, the Akbar and Birbal stories are wonderfully simple yet leave a lasting impression. Birbal is the patient and wise teacher and Akbar an often impetuous and boastful pupil. Their friendship is warm and full of charm and makes these tales a delight.

In reworking these stories, I will admit to plenty of creative licence. I wanted to make these stories accessible and readable for western audiences of all stripes. As such, many of the previously published versions needed polishing and editing. Joseph Jacob’s original versions were of particular concern and have seen the greatest changes, although the others have been re-imagined too. Keen to keep this collection secular, I have steered clear of religion where possible. I have also removed archaic and often offensive terms, as well as re-working the roles of women in one or two cases.

Continuity and plotting were also an issue. For some of these tales, my starting point was just a few badly translated lines found online, or in obscure, often self-published books. For others, I had dense passages to work through, most of which lacked clarity. In one case, an entire section seemed to be missing. Where possible, I stuck to the original plot lines rigidly. For others, this was almost infeasible, and so I imagined and wrote new connecting scenes. All of this was done to enhance the reading experience and simplify often complicated language.

They aim of this project is to widen potential readership, and take these tales to an audience yet to benefit from reading them. Reworking folk tales can be a hazardous business, and often people become attached to their own versions of a particular tale. I meant no disrespect in modernising these tales. Think of them simply as remixes, intended to engage and enchant modern readers, and to lure them further into Indian folklore.

'Tales from India' by Bali Rai is published by Puffin Classics

Bali Rai is the multi-award winning author of over 30 young adult, teen and children's books. His edgy, boundary-pushing writing style has made him extremely popular on the school visit circuit across the world and his books are widely taught. Passionate about promoting reading and literacy for young people, he is an ambassador for the Reading Agency’s Reading Ahead project, was involved in the BBC’s Love To Read campaign, and also speaks about issues around diversity, representation, and in defence of multiculturalism. Regularly invited to speak on panels and at conferences, he is also patron of an arts charity and a literature festival. Bali is a politics graduate and was recently awarded an honorary doctorate of letters. His first novel, (Un)arranged Marriage was published in 2001, and his most recent YA novel,

Web of Darkness

, won three awards and received widespread acclaim. He is currently working on a new YA title, as well as two series for younger readers. His latest title,

TheHarder They Fall

, is available now.

Bali Rai is the multi-award winning author of over 30 young adult, teen and children's books. His edgy, boundary-pushing writing style has made him extremely popular on the school visit circuit across the world and his books are widely taught. Passionate about promoting reading and literacy for young people, he is an ambassador for the Reading Agency’s Reading Ahead project, was involved in the BBC’s Love To Read campaign, and also speaks about issues around diversity, representation, and in defence of multiculturalism. Regularly invited to speak on panels and at conferences, he is also patron of an arts charity and a literature festival. Bali is a politics graduate and was recently awarded an honorary doctorate of letters. His first novel, (Un)arranged Marriage was published in 2001, and his most recent YA novel,

Web of Darkness

, won three awards and received widespread acclaim. He is currently working on a new YA title, as well as two series for younger readers. His latest title,

TheHarder They Fall

, is available now.

Published on August 17, 2017 00:29

August 3, 2017

The Silver Cup from Dagberg Daas

Here is a version of an old tale I used in my first book, Troll Fell’. I love the practical but horrific way this 'berg-woman' deals with her long, drooping breasts. A berg-man or berg-woman is a mound dweller, elf or troll.

In Dagberg Daas there formerly lived a berg-man with his family. It happened once that a man who came riding past there took it into his head to ask the berg-woman for a little to drink. She went to get some for him, but her husband bade her take it out of the poisoned barrel. The traveller heard all this, however, and when the berg-woman handed him the cup with the drink, he threw the contents over his shoulder and rode off with the cup in his hand, as fast as his horse could gallop. The berg-woman threw her breasts over her shoulders, and ran after him as hard as she could. (The man rode off over some ploughed land where she had difficulty in following him, as she had to keep to the line of the furrows.) When he reached the spot where Karup Stream crosses the road from Viborg to Holtebro, she was so near him that she snapped a hook (hage) off the horse’s shoe, and therefore the place has been called Hagebro ever since. She could not cross the running water, and so the man was saved. It was seen afterwards that some drops of the liquor had fallen on the horse’s loins and taken off both hide and hair.

From Scandinavian Folklore, ed William Craigie, 1896

'Troll Fell' by David Wyatt

'Troll Fell' by David WyattIn my book 'Troll Fell' the children's father Ralf tells the tale to Gudrun his wife, and his three children:

"I was halfway over Troll Fell, tired and wet and weary, when I saw a bright light glowing from the top of the crag, and heard snatches of music gusting on the wind."

“Curiosity killed the cat,” Gudrun muttered.

“I turned the pony off the road and kicked him into a trot up the hillside. I was in one of our own fields, the high one called the Stonemeadow. At the top of the slope I could hardly believe my eyes. The whole rocky summit of the hill had been lifted up, like a great stone lid! It was resting on four stout red pillars. The space underneath was shining with golden light and there were scores, maybe hundreds of trolls, all shapes and sizes, skipping and dancing, and the noise they were making! Louder than a fair, what with bleating and baaing, mewing and catetwauling, horns wailing, drums pounding, and squeaking of one-string fiddles!”

“How could they lift the whole top of Troll Fell, Pa?” asked Sigurd.

“As easily as you take off the top of your egg,” joked Ralf. He sobered. “Who knows what powers they have, my son? I only tell what I saw, saw with my own eyes. They were feasting in the great space under the hill: all sorts of food on gold and silver dishes, and little troll servingmen jumping about between the dancers, balancing great loaded trays and never spilling a drop, clever as jugglers! It made me laugh out loud.

“But the pony shied. I'd been so busy staring, I hadn't noticed this troll girl creeping up on me till she popped up right by the pony's shoulder. She held out a beautiful golden cup filled to the brim with something steaming hot - spiced ale I thought it was, and I took it gratefully from her, cold and wet as I was!”

“Madness!” muttered Gudrun.

Ralf looked at the children. “Just before I gulped it down,” he said slowly, “I noticed the look on her face. There was a gleam in her slanting eyes, a wicked sparkle! And her ears, her hairy, pointed ears, twitched forward. I saw she was up to no good!”

“Go on!” said the children breathlessly.

Ralf leaned forwards. “So, I lifted the cup, pretending to sip. Then I jerked the whole drink out over my shoulder. It splashed out smoking, some on to the ground and some on to the pony's tail, where it singed off half his hair! There's an awful yell from the troll girl, and the next thing the pony and I are off down the hill, galloping for our lives. I've still got the golden cup on one hand – and half the trolls of Troll Fell are tearing after us!”

Soot showered into the fire. Alf, the old sheepdog, pricked his ears. Up on the roof the troll lay flat with one large ear unfurled over the smoke-hole. Its tail lashed about like a cat’s and it was growling. But none of the humans noticed. They were too wrapped up in the story. Ralf wiped his face, his hand trembling with remembered excitement, and laughed.

“I daren’t go home,” he continued. “The trolls would have torn your mother and Hilde to pieces. I had one chance. At the tall stone called the Finger, I turned off the road on to the big ploughed field above the mill. The pony could go quicker over the soft ground, you see, but the trolls found it heavy going across the furrows. I got to the mill stream ahead off them, jumped off and dragged the pony through the water. I was safe! The trolls couldn't follow me over the brook. They were spitting like cats and hissing like kettles. They threw stones and clods at me, but it was nearly dawn and off they scuttled back up the hillside. And I heard – no, I felt, through the soles of my feet, a sort of far-off grating shudder as the top of Troll Fell sank into its place again...”

Troll Fell by Katherine Langrish, HarperCollins: all three books of the Troll Trilogy are currently available in an omnibus edition entitled 'West of the Moon'

Picture credits: 'Troll Fell', unpublished illustrations by David Wyatt in author's possession: copyright David Wyatt 2004

Published on August 03, 2017 03:35

July 20, 2017

The Naming of Dark Lords!

It's summer, the sun is actually shining (or it was): hopefully we've all got better things to do than sit indoors - and I've got a book I need to finish writing. So I'll be taking a break from this blog for a few months. While I'm away I'll be putting up some posts 'from the archives'. This one first appeared in June 2015; whether you've read it before or missed it first time around, I hope it will amuse. See you in the autumn! The Naming of Dark Lords: a difficult matter: it isn't just one of your fantasy games...

At the age of nine or so, one of my daughters co-wrote a fantasy story with her best friend. By the time they’d finished it ran to sixty or seventy pages, a wonderful joint effort – they’d sit together brainstorming and passing the manuscript to and fro, writing alternate chapters and sometimes even paragraphs. There were two heroines - one for each author - and sharing their adventures was a magical teddybear named Mr Brown, who spoke throughout in pantomime couplets. Transported to a magical world on the back of a dove called Time – who provided the neat title for the story: ‘Time Flies’ – the trio found themselves battling a Dark Lord of impeccable evil with the fabulous handle of LORD SHNUBALUT (pronounced: ‘Shnoo-ba-lutt’.) The two young authors had grasped something critical about Dark Lords. They need to have mysterious, sonorous, even unpronounceable names.

Imagine you’re writing a High Fantasy. You’ve got your world and you’ve sorted out the culture: medieval in the countryside with its feudal system of small manors and castles; a renaissance feel to the bustling towns with their traders, guilds and scholar-wizards. The forests are the abode of elves. Heroic barbarians follow their horse-herds on the more distant plains. Goblins and dwarfs battle it out in the mountains.

And lo! your Dark Lord ariseth. And he requireth a name.

Let’s take an affectionate look at the names of a few Dark Lords. The first to come to mind is of course Tolkien’s iconic SAURON from The Lord of the Rings. A name not too difficult to pronounce, you’d think – except that when the films came out I discovered I’d been getting it wrong for years. I’d always assumed the ‘saur’ element should be pronounced as in ‘dinosaur’, and ‘Saw-ron’, with its hint of scaly, cold-blooded menace, still sounds better to me than ‘Sow-ron.’ I was only 13 when I first read The Lord of the Rings, and although I was blown away, and keen enough to wade through some of the Appendices, I never got as far as Appendix E in which Tolkien explains that ‘au’ and ‘aw’ are to be pronounced ‘as in loud, how and not as in laud, haw.’ But who reads the Appendices until they’ve read the entire book? - by which time I’d been getting it wrong for months and my incorrect pronunciation was fixed. Still, there it is. Peter Jackson got it right and I was wrong.

Not content with one Dark Lord, Tolkien created two - three, if you count the otherwise anonymous Witch-King of Angmar, leader of the Nazgul and the scariest of the bunch if you want my opinion. In The SilmarillionMelkor is given the name MORGOTH after destroying the Two Trees and stealing the Silmarils. In Sindarin the name means ‘Dark Enemy’ or ‘Black Foe’, but Tolkien must have been aware that its second element conjures the 5thcentury Goths who sacked Rome and that, additionally, the name carries echoes of MORDRED, King Arthur’s illegitimate son by his half-sister Morgan le Fay. Of course Mordred is not a high fantasy Dark Lord, but he’s certainly a force for chaos and darkness. Though the name is actually derived from the Welsh Medraut(and ultimately the Latin Moderatus), to a modern English ear it suggests the French for death, ‘le mort’, along with the English ‘dread’: a pleasing combination for a villain. Mordred and Morgoth are names redolent of fear, death and darkness, and the ‘Mor’ element appears again in Sauron’s realm of ‘Mordor’, the Black Land.

The name of JK Rowling’s LORD VOLDEMORT is also suggestive of death and borrows some of the dark glamour of Mordred, but the circumlocutory phrase HE-WHO-MUST-NOT-BE-NAMED (used by his enemies for fear of conjuring him up) certainly owes something to H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha, SHE WHO MUST BE OBEYED. Interestingly, males become Dark Lords but females are never Dark Ladies – which doesn’t have the same ring at all*. They turn into Dread Queens, such as Galadriel might have become if she had succumbed to temptation and taken the Ring from Frodo:

In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and Lighting! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!

Coming down to us from many an ancient goddess, Dread Queens are usually beautiful, sexual women of great power and cruelty, like T.H. White’s MORGAUSE, Queen of Orkney from The Once And Future King, busy – on the first occasion we meet her – boiling a cat alive. In his notes about her, T.H. White wrote: