Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 2

July 18, 2024

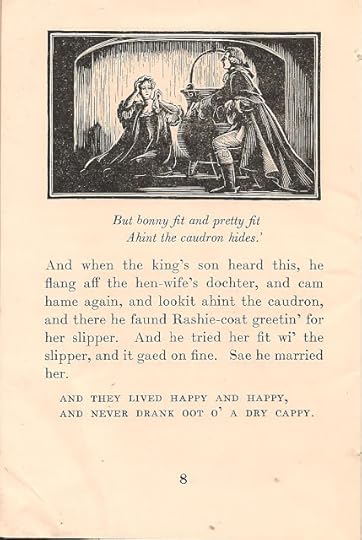

The Scottish fairy tale 'Rashie Coat' illustrated by Joan Hassall

For more than a decade from the mid 1970s the artist JoanHassall was a neighbour of my family in the Yorkshire Dales village of Malham. I wastwenty in 1976 when she inherited Priory Cottage in the village, and she livedthere until her death in 1988 at the age of 82. Joan was a skilled woodengraver who illustrated many, many books (you can read more about her life here). I was a bit too young to be a friend, but I knew her as a much-loved villagefigure, with her thick pebble glasses, beautiful smile and layers offlower-patterned skirts. She played a number of musical instruments and forsome time was organist at the parish church of St Michael the Archangel. She attendedour wedding there in 1987 – not to play the organ on that occasion, just to bethere – and we can never forget how she came up to us after the ceremony, andwith the sweetest smile said simply: 'Be happy!' It was a genuine blessingif ever there was one, and a command we've done our best to obey.

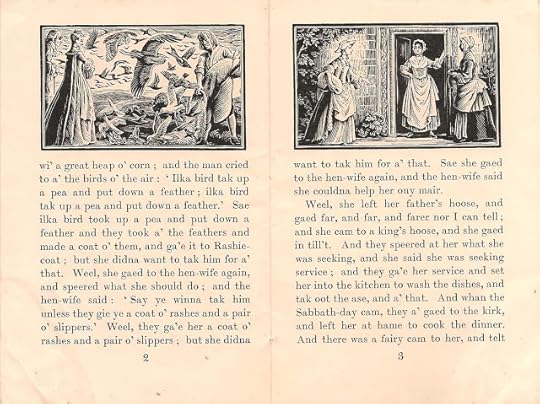

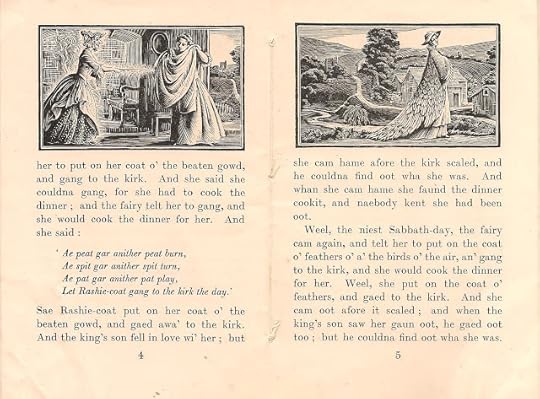

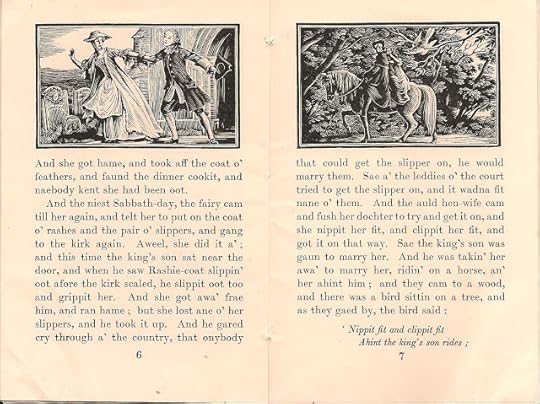

I have two or three books illustrated by Joan, and for meas a lover of fairy tales this one is special. She was commissioned to designand produce a series of chapbooks for the Saltire Society which was set up in1936 to ‘promote and celebrate the uniqueness of Scottish culture andheritage’. The books are tiny – approximately 13 x 9cm – but the work isexquisite. This is number 12, published 1951. It is the old Scottish fairytale of ‘Rashie Coat’ and I guess, though I cannot be sure, that the elegant signatureon the flyleaf is Joan’s own writing. She was a fine artist and a lovely person. I hope you'll enjoy her work.

Picture credit

Portrait of Joan Hassall see wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Joan_Hassall.jpg

May 2, 2024

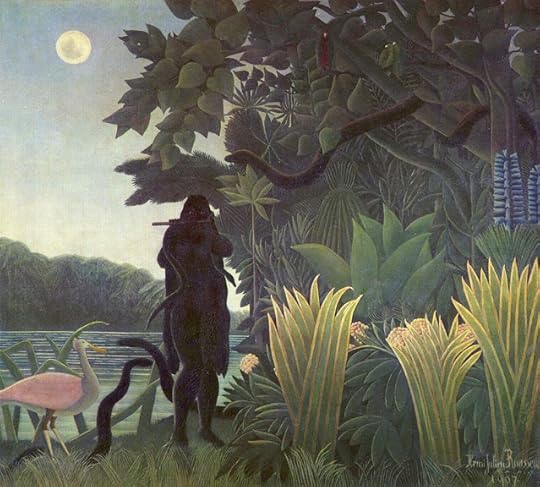

Portals and Paintings

A very long time ago inmy late teens, I wrote a book with the rather unimaginative title ‘The MagicForest’ which was (quite rightly) never published. Although derivative (I was inspiredby Walter de la Mare’s strange and wonderful novel ‘The Three Royal Monkeys’)it was nevertheless the closest I’d yet got to finding my own voice; and I’dbeen writing lengthy narratives ever since nine or ten years old. It was adream-quest story in which a girl goes through a picture into a magical world:the picture in question was a reproduction of Henri Rousseau’s ‘The Snake-Charmer’ which hung on my bedroom wall (see above). Myheroine, Kay, looks at it and sees

...the ripples of a lake reflecting the quick luminousafterglow of a sun’s sinking. There were night-flowering reeds and a tall,heron-like bird, and standing in the darkness of the trees, partly insilhouette against the night sky, was a human figure. It was wearing a darkcloak and piping on a flute. Answering the flute came snakes, great forest pythonspouring scarcely distinguishable from the branches and from the lake. Kay’s feetsank into shallow mud. She heard the low, hollow-sweet notes, saw the snakestwist about the charmer’s legs. A heavy, scaly body dragged over her foot.Midges stung and bit her, but a little coolness came breathing over the water.

And so begins an adventure which I won’t bore you with, it's enough to say that Kay goes on aquest with a yellow water-bird and a monkey, to find a sorcerer who has infestedthe forest with poisonous butterflies.

I knew that ‘going into a picture’ was not an original ideabut one which had appeared in several of my favourite children’s books. In C.S.Lewis’s ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ (1952) Lucy and Edmond Pevensie, andtheir cousin Eustace Scrubb, tumble into a painting of what looks like aNarnian ship at sea. When Eustace asks Lucy why she likes it, she replies, ‘because the ship looks as if it was really moving. And the water looks as ifit was really wet. And the waves look as if they were really going up and down.’She’s right, they are doing thesethings. The ship rises and falls over the waves, a wind blows into the roombringing a ‘wild, briny smell’, and ‘Ow!’ they all cry, for ‘a great, cold,salt splash had broken right out of the frame and they were breathless from thesmack of it, besides being wet through.’ As Eustace rushes to smash the paintingthe other two try to pull him back. Next moment all three are struggling on theedge of the picture frame, and a wave sweeps them into the sea.

Lewis didn’t invent the ‘picture as portal’ trope, either.It’s quite likely he found it in a Japanese tale, ‘The Story of Kwashin Koji’ from‘Yasō-Kidan’ (‘Night-Window Demon Talk’), a book of legends collected byIshikawa Kosai (1833-1918) and retold by Lafcadio Hearn in his 1901 book ‘AJapanese Miscellany’. It is the sort of thing Lewis would have read. It tellsof Kwashin Koji, a rather disreputable old fellow and a heavy drinker, who madea living ‘by exhibiting Buddhist pictures and by preaching Buddhist doctrine.’On fine days he would hang a large picture – ‘a kakemono on which were depictedthe punishments of the various hells’ – on a tree in the temple gardens andpreach about it. The painting was so wonderfully vivid that onlookers wereamazed.

Hearingthis, the ruler of Kyōto, Lord Nobunaga, commanded Kwashin Koji to bring it tothe palace where he could view it. The old man obliged and Nobunaga was deeply impressedby the painting. Noticing this, his servant suggested that Kwashin should offerit as a gift to the great lord. Since his livelihood depended upon the picture,Kwashin asked instead for payment in gold, which was refused. So he rolled up thepicture and left. But the servant followed him, killed him, and took the picturefor his lord. When the scroll was unrolled, however, it was found to be completelyblank – while Kwashin had mysteriously returned to life and was showing hispicture in the temple grounds as before. Some time later Nobunaga was himself murderedby Mitsuhidé, one of his captains, who invited Kwashin Koji to the palace, feastedhim and gave him plenty to drink. The old man then pointed to a large foldingscreen which depicted ‘Eight Beautiful Views of the Lake of Omi’, and said, ‘Inreturn for your august kindness, I shall display a little of my art’. Far off inthe background, the artist had painted a man rowing a boat, ‘occupying, uponthe surface of the screen, a space of less than an inch in length.’ As KwashinKoji waved his hand, everyone in the room saw the boat turn and begin to approachthem. It grew rapidly larger...

And all of a sudden, the water of the lake seemed tooverflow out of the picture into the room, and the room was flooded; and thespectators girded up their robes in haste as the water rose above their knees.In the same moment the boat appeared to glide out of the screen, and thecreaking of the single oar could be heard. Then the boat came close up toKwashin Koji, and Kwashin Koji climbed into it; and the boatman turned about, andbegan to row away very swiftly. And as the boat receded, the water in the roombegan to lower rapidly, seeming to ebb back into the screen... But still thepainted vessel appeared to glide over the painted water, retreating furtherinto the distance and ever growing smaller, till ... it disappeared altogether,and Kwashin Koji disappeared with it. He was never again seen in Japan.

The lakewater floodingout of the painted screen corresponds to the ‘great salt splash’ of the wave burstinginto the children’s bedroom in ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, while thecreaking oar finds an echo in Lewis’s description of ‘the swishing of waves andthe slap of water against the ship’s sides and the creaking and the overallhigh steady roar of air and water’.

John Masefield’s ‘The Midnight Folk’ (1927), and its sequel‘The Box of Delights’ (1935) contain some delightful ‘pictures as portals’. In‘The Midnight Folk’ little Kay Harker, left by his governess to learn the verb‘pouvoir’, looks up as the portrait of his great-grandpapa comes to life:

As Kay looked, great-grandpapa Harker distinctly took astep forward, and as he did so, the wind ruffled the skirt of his coat andshook the shrubs behind him. A couple of blue butterflies which had been uponthe shrubs for seventy odd years, flew out into the room. ... Great-grandpapaHarker held out his hand and smiled... “Well, great-grandson Kay,” he said, “nepouvez vous pas come into the jardin avec moi?” [....]

Kay jumped on to the table; from there,with a step of run, he leaped on to the top of the fender and caught themantelpiece. Great-grandpapa Harker caught him and helped him up into thepicture. Instantly the schoolroom disappeared. Kay was out of doors standingbeside his great-grandfather, looking at the house as it was in the pencildrawing in the study, with cows in the field close to the house on what was nowthe lawn, the church, unchanged, beyond, and, near by some standard yellowroses, long since vanished, but now seemingly in full bloom.

His great-grandfathertakes him into the house, where ‘A black cat, with white throat and paws, whichhad been ashes for forty years, rubbed up against great-grandpapa’s legs andthen, springing on the arm of his chair, watched the long-dead sparrows in theplum tree which had been firewood a quarter of a century ago’. This beautifullygentle transition into the past aswell as into a painting is something I’ve always loved: it depicts time past withyearning but without melancholy, and we see little orphaned Kay receive careand support from kind ancestors who watch over him. Exciting as it is, ‘TheMidnight Folk’ is a book a child can read and never feel unsafe. Later in the story,Kay realises that his governess is really a witch, and his grandmother’sportrait addresses him.

“Don’t let a witch take charge at Seekings. This is a housewhere upright people have lived. Bell her, Kay; Book her, boy; Candle her,grandson; and lose no time: for time lost’s done with, but must be paid for.”

He looked upat her portrait, which was that of a very shrewd old lady in a black silkdress. She was nodding her head at him so that her ringlets and earrings shook.“Search the wicked creature’s room,” she said, “and if she is, send word to the Bishop at once.”

“All right,”Kay said, “I’ll go. I will search.”

This time Kay doesn’tenter the picture, but his grandmother’s words give him strength, confidenceand purpose.

Astring of pack mules descend the mountain path, and near the end of the line trotsa white mule with a red saddle.

The first mules turned off at a corner. When it came to theturn of the white mule to turn, he baulked, tossed his head, swung out of theline, and trotted into the room, so that Kay had to move out of the way. Therethe mule stood in the study, twitching his ears, tail and skin against thegadflies and putting down his head so that he might scratch it with his hindfoot. “Steady there,” the old man whispered to him. “And to you, Master Kay, Ithank you. I wish you a most happy Christmas.”

At that, he swung himself onto the mule,picked up his theatre with one hand, gathered the reins with the other, said,“Come, Toby,” and at once rode off with Toby trotting under the mule, out ofthe room, up the mountain path, up, up, up, till the path was nothing more thana line in the faded painting, that was so dark upon the wall.

One of the many reasonsthis passage works so well is its detailed physicality, the realistic animalbehaviour of the mule quivering its skin and scratching its head and taking upso much room in the study. And as magic, it’s such a satisfactory way to foil the baddies.

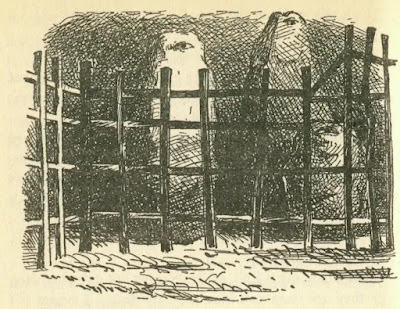

Towardsthe end of the book, Kay has ‘gone small’ via the magic of the Box of Delightsbut having temporarily lost the Box he cannot restore himself to his propersize. Finding Cole Hawlings chained and caged in the underground caverns whichAbner Brown is about to flood, he creeps into Cole’s pocket for a bit of leadpencil and a scrap of paper on which to draw, at Cole’s request, ‘two horsescoming to bite these chains in two’. Though plagued by the snapping jaws oflittle magical motor-cars and aeroplanes, he manages to draw the horses ratherwell.

The drawings did stand out from the paper rather strangely.The light was concentrated on them; as he looked at them the horses seemed tobe coming towards him out of the light; and no, it was not seeming, they weremoving; he saw the hoof casts flying and heard the rhythmical beat of hoofs. Thehorses wer coming out of the picture, galloping fast, and becoming brighter andbrighter. Then he saw that the light was partly fire from their eyes and manes,partly sparks from their hoofs. “They are real horses,” he cried. “Look.”

It was asthough he had been watching the finish of a race with two horses neck and neckcoming straight at him... They were two terrible white horses with flamingmouths. He saw them strike great jags of rock from the floor and cast them,flaming, from their hoofs. Then, in an instant, there they were, one on eachside of Cole Hawlings, champing the chains as though they were grass, crushingthe shackles, biting through the manacles and plucking the iron bars as thoughthey were shoots from a plant.

“Steady there, boys,” said Cole...

Cole places thediminutive Kay on one of the horses and leads them along the rocky corridor,but the water is coming in fast. ‘Draw me,’ says Cole, ‘a long roomy boat witha man in her, sculling her’ and ‘put a man in the boat’s bows and draw him witha bunch of keys in his hand.’ Kay does his best, although the man’s nose is ‘ratherlike a stick’, and Cole places the drawing on the water. It drifts away whilethe stream becomes angrier and more powerful.

“The sluice-mouth has given way,” Kay said.

“That isso,” Cole Hawlings answered. “But the boat is coming too, you see.”

Indeed, downthe stream in the darkness of the corridor, a boat was coming. She had a lightin her bows; somebody far aft in her was heaving at a scull which ground in therowlocks. Kay could see and hear the water slapping and chopping against heradvance; the paint of her bows glistened above the water. A man stood above thelantern. He had something gleaming in his hand: it looked like a bunch of keys.As he drew nearer, Kay saw that this man was a very queer-looking fellow with anose like a piece of bent stick.

With its boatman, boat,creaking oar and rush of oncoming water, this too is very reminiscent of thetale of Kwashin Koji, which I suspect Masefield as well as Lewis may have read.Whether it’s so or not, both the concept and the writing are wonderful.

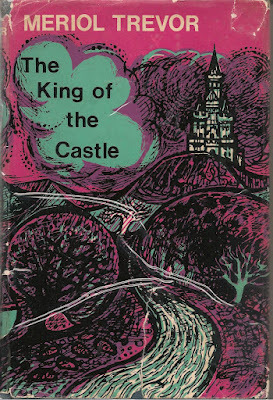

A novelwhich owes nothing to the Japanese story is Meriol Trevor’s ‘The King of theCastle’ (1966). A decade on from C. S. Lewis but largely forgotten today,Trevor’s books for children were well-written and sometimes powerful fantasieswith allegorical Christian themes; I would borrow them from the local library and enjoyed them.. They were less popular among children thanLewis’s books, probably because Trevor’s ‘Christ’ figures were human adults, whereLewis had a glorious golden lion. They follow in general the pattern of‘contemporary children find a way into magical worlds and go on quests’; herbest book is (I think) ‘The Midsummer Maze’, but ‘The King of the Castle’ is good too. It openswith a boy, Thomas, sick in bed (see mysteriousillnesses that keep children marooned in bed for weeks). Slowly recovering fromwhatever it was, he grows bored, so one day his mother gives him a gilt-framed pictureshe bought in a junk shop, so that he will ‘have something to look at insteadof the wallpaper’. This feels a bit forced; would a young boy really appreciate‘an old engraving in the romantic style’? But perhaps the castle swings it:

It showed a wild rocky landscape with twisted thorn treeson the horizon, bent by years of gales, and a few sheep prowling on the thingrass near a torrent which rushed turbulently out of a deep and shadowy ravine.Beside the river a road ran, white in the darkness, till it too disappearedbehind the steep shoulder of the gorge. Perhaps it led on to the castle whichbacked against a wild and stormy sky of clouds that rolled like smoke over thesombre hills.

Thomas thinks it ‘verymysterious’ and once it’s on the wall he lies looking at it.

He wondered where the road went after it turned the corner.He imagined himself walking along the road, rutted and dusty, stony as it was.The huge cliffs loomed above him.

“But I amwalking along the road,” Thomas thought suddenly. He looked down and saw hisfeet walking. They wore brown leather rubber-soled shoes. He was not wearingpyjamas but jeans and his thick sweater, but the wind seemed to cut through thewool. It was cold.

Following the road upbeside the rushing river, he turns to look back, wondering if he will see hisbedroom with himself lying in bed. But ‘what he saw was the wild country of thepicture extended backwards, the river running away and away towardsthick-forested hills. It was almost more unnerving to find himself totally inthe world of the picture.’ I like this acknowledgment of the unsettling side of suddenly entering an unknown world. Soon after, a young shepherd and his dog rescue Thomas from a wolf. The shepherd turns out to be this book’s Christ figure,and at the end of the story Thomas returns through the picture to find himselfback in bed.

Comparedwith with the other ‘paintings as portals’ discussed here, this is perhaps theweakest, since Thomas’s interaction with the engraving is entirely passive. It’s given to him and he doesn’t even need to leave his bed: just looking at it does the job. Characters in the other stories all have some degreeof agency in passing through the portals. Kwashin Koji is in full control of what happens: he can enter a painting at will. Lucy and Edmund topple into the Eastern Sea while actively trying to prevent Eustace breaking thepicture. Accepting his great-grandfather’s invitation, Kay Harkerclambers on to the mantelpiece to reach him. Like Kwashin Koji, Cole Hawlings chooses a painting to enter and escape through, while the rather older Kay Harker of ‘The Box of Delights’ draws the pictureswhich come to life and rescue them. (Do these drawings count as portals? Whileit’s true that Kay and Cole don’t pass through them, the horses, boats and boatmen emerge from the paper into this world, so I think they do.)

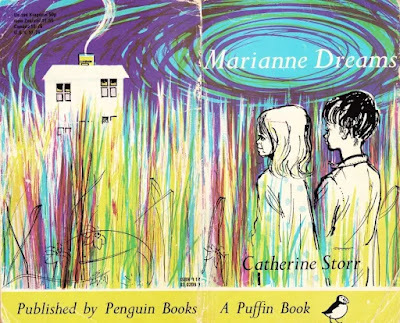

Kay’sdrawings of horses and boatmen bring me to the drawings in Catherine Storr’swonderfully sinister ‘Marianne Dreams’ (1958). Marianne is another child struckdown by an unnamed illness that keeps her in bed. Weeks on, bored and convalescent,she finds a stub of pencil in an old work-box and uses it to draw a house withfour windows, a door and a smoking chimney – to which she adds a fence, a gateand a path, a few flowers, ‘long scribbly grass’ and some rocks. Then she fallsasleep and dreams she’s alone in a vast grassland dotted with rocks. Walking towardsa faint line of smoke she arrives at a blank-eyed house with ‘a bare frontdoor’ ringed with an uneven fence and pale flowers. A cold wind springs up andshe’s frightened. ‘I’ve got to get away from the grass and the stones and thewind. I’ve got to get inside.’

Marianne’sdreams take her into the inimical ‘world’ of her drawing: what she finds theredepends on whatever she has recently drawn, plus the mood in which she drew it. The experience is uneasy from the start and becomes scarier at every visit. It’sarguable that the drawings (to which she keeps adding) are not portals at all, onlythe catalyst for dreams which express Marianne’s anger, fear and stress. Neverthelessthe strange ‘country’ in which she finds herself – and to a certain extent manipulates– feels psychologically serious and real; portals may work in more than oneway. She draws a boy looking out of the window, someone who can let her intothe house. Next night he is there. She discovers that his name is Mark: he isreal, very ill and unable to walk, and shares with her the same nice hometutor. In the dream world he is dependent on her: as the wielder of the pencilshe can draw things for his comfort – or not. In a fit of temper one day she scribblesthick black lines, like bars, all over the window where he sits – raises thefence, adds more stones in a ring around the house and gives to each one asingle eye. All these horrifying things become real in her next dream.

Marianne looked round the side of the window. From whereshe stood she could see five – six – seven of the great stones standingimmovable outside. As she looked there was a movement in all of them. The greateyelids dropped; there was a moment when each figure was nothing but a hunk ofstone, motionless and harmless. Then, together, the pale eyelids lifted andseven great eyeballs swivelled in their stone sockets and fixed themselves onthe house.

Mariannescreamed. She felt she was screaming with the full power of her lungs,screaming like a siren: but no sound came out at all. She wanted to warn Mark,but she could not utter a word. In her struggle she woke.

As the terrifying stoneWatchers crowd ever closer to the house, Marianne and Mark must escape.Marianne draws hills in the distance behind the house, with a lighthousestanding on them, for she knows the sea there, just out of sight. Eventuallythe children make it to the lighthouse on bicycles she has drawn. Here they aresafe, but Mark points out that they can’t stay forever. They must reach thesea, inaccessible below high cliffs. A helicopter is needed, but Mariannecannot draw helicopters. After struggling with herself to relinquish power (‘it’smy pencil!’) she draws the pencilinto the dream so that Mark can have it. He draws a helicopter which arrivesbefore Marianne can dream again, but leaves a message promising to make it comeback for her: in the end trust prevails.

Everything seemed to be resting; content; waiting. Markwould come: he would take her to the sea. Marianne lay down on the short,sweet-smelling turf. She would wait, too.

‘Marianne Dreams’ canbe genuinely frightening, nightmarish even; but the children’s bickering yetsupportive friendship enlivens the story and makes it accessible to youngreaders.

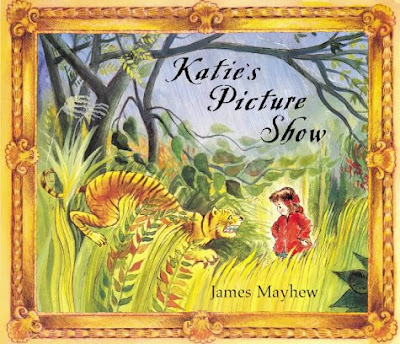

Lastly, I cannot resist mentioning James Mayhew’s much-lovedand utterly charming series of picture-books which introduce younger childrento art. ‘Katie’s Picture Show’ was the first, published in 2004 and followed byseveral others in which little Katie jumps into various famous paintings, meetsthe characters and has age-appropriate adventures.

Pictures,especially representative pictures, are like windows. We simultaneously look at them and through them. John Constable’s ‘The Cornfield’ lures the viewer in,past the young boy drinking from the brook, past the panting sheepdog and thedonkeys under the bushes, past the reapers busy in the yellow corn, and ontowards the far horizon. In imagination we enter not only the picture but also thelong-departed past of 1820s Suffolk – in much the same way as little Kay Harkerclambers into his great grandfather’s portrait and sees his home as it used tobe, generations before.

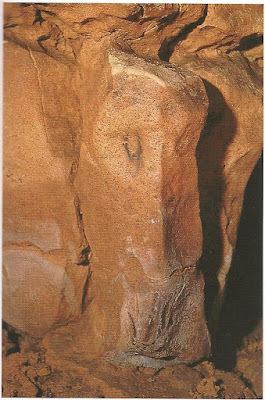

Who knowswhen the first person looked at a picture and imagined being inside it? Wecannot know, but it’s a natural thought and I would guess a very old one. Inhis remarkable analysis of prehistoric cave art, ‘The Mind in the Cave’ (2002),David Lewis-Williams suggests that ‘oneof the uses of [Paleolithic] caves was for some sort of vision questing’ andthat ‘the images people made there related to that chthonic [subterranean] realm.’Adding that sensory deprivation in such remote, dark and silent chambers mayhave induced altered states of mind, he continues:

In their various stages of altered states, questers sought,by sight and touch, in the folds and cracks of the rock face, visions ofpowerful animals. It is as if the rock were a living membrane between those whoventured in and one of the lowest levels of the tiered cosmos; behind the membranelay a realm inhabited by spirit animals and spirits themselves, and thepassages and chambers of the cave penetrated deep into that realm.

The Cave inthe Mind, David Lewis-Williams, p214

Locating lines, shapesand holes in cave walls reminiscent of animals or bits of animals, these earlypeople painted in eyes, nostrils, identity – making them emerge out of therock.

Here is a ‘mask’ from the deepest passage of Altamira Cave in Spain. It could be a horse, but it remains ambiguous. Lewis-Williams quotes anAmerican archeologist, Thor Conway, who visited a Californian rock art sitecalled Saliman Cave:

Red and black paintings surround two small holes bored intothe side of the walls by natural forces. As you stare at these entrance ways toanother realm, suddenly – and without voluntary control – the pictographs breakthe artificial visual reality that we assume.... Suddenly, the paintingsencompassing the recessed pockets began to pulse, beckoning us inward.

Painted Dreams, Native Americal Rock Art,T.Conway, p109-10

Lewis-Williams comments that certain South African rock paintings by the San, that 'seem tothread in and out of the the walls of rock shelters' may 'similarly came to life anddrew shamans through the ‘veil’ into the spirit realm.’ So is it possible that the notion of paintingsas portals may go back all the way to the Paleolithic? That’s quite a thought.

Picture credits:

The Snake-Charmer by Henri Rousseau, 1907, Musee D'Orsay, wikipedia

The Voyage of The Dawn Treader: illustration by Pauline Baynes

Marianne Dreams: illustration by Marjorie Ann Watts

Katie's Picture Show: illustration by James Mayhew

The Cornfield by John Constable, 1826, National Gallery

Photo from Altamira Cave: David Lewis-Williams, 'The Mind in the Cave'

March 1, 2024

Seal songs and legends

Stories about selkies areambiguous, evocative, sad.

This is largely because of the way seals themselvesaffect us. Bobbing curiously up around boats, they seem to feel as muchinterest in us as we feel for them, and there is something humanabout their round heads and large eyes. Basking on sunlit rocks they are partof our world, yet are also natural inhabitants of an unseen, underwaterworld in which we would drown. For most of our species' co-existence, only in imagination could we follow them there.

Mymother used to sing a lovely song called Song tothe Seals (words by Sir Harold Boulton, music by Granville Bantock) about asea-maid who sits on a reef calling the seals in a lilting, melancholyrefrain: ‘Hoiran oiran oiran eero… hoiranoiran oiran eero… hoiran oiran oiran ee la leu ran…’ You can listen to it here, sung by boy treble Sebastian Carrington.

And the sheet musicincludes a introductory note: ‘The refrain of this song was actually usedrecently on a Hebridean island by a singer who thereby attracted a quantity ofseals to gather round and listen intently to the singing.’

With so much inter-species interaction and fascinationgoing on, it’s no wonder there are many legends and songs about selkies: seal-peoplewho can cast off their thick pelts and appear in human form. The ballad of The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry existsin a number of variants, but the earliest was written down in 1852 byLieutenant F.W.L. Thomas of the Royal Navy, and it was dictated to him by anold lady of Snarra Voe, Shetland. The ballad tells the tragedy of a woman whohas borne a child to a unsettlingly Other selkie man, ‘a grumlie guest’ whobrings a waft of salt-sea terror as he appears. ‘I am a man upo’ the land, heannounces,

‘An’ I am a Silkie inthe sea;

And when I’m far and far frae lan’

Mydwelling is in Sule Skerrie.’

As Lieutenant Thomas explains:

The story is founded on the superstition of the Seals or Selkies beingable to throw off their waterproof jackets, and assume the more gracefulproportions of the genus Homo… Silky is a common name in the north country fora seal, and appears to be a corruption of selch,the Norse word for that animal. Sule Skerry is a small rocky islet, lying abouttwenty-five miles to the westward of Hoy Head, in Orkney, from whence it may beseen in very clear weather…

And he tells of coming infrom the cod-fisheries on a foggy, windless morning, rowing ‘for nearly a milethrough the narrow channels formed by a thousand weed-covered skerries’ andhearing the seals’ ‘lullaby’: ‘groans and sighs expressive of unutterable torment…followed by a melancholy howl of hopeless despair’.

A fewyears ago, wandering the fractured rocky shore of Longstone Island off thecoast of Northumberland, I too became aware of this eerie sound. Keening,moaning, huff-huff-huffing – hooting like children who make long quaveringghost noises – a group of twenty or so seals were crying to one another as theylay on a ridge at the edge of the tide.

Theunnamed woman in The Great Silkie isdestined to lose both her half-selkie child and its selkie father: the Silkiepredicts she will marry a mortal man, ‘a proud gunner’, who will shoot them whilethey play together in the bright summer sea.

The SuleSkerry selkie is male, but the best-known selkie tales tell of a seal-womancaptured by a fisherman who sees her dancing on a moonlit beach. He steals herdiscarded skin, preventing her from changing back into seal form. Such storiesgenerally end when the selkie bride recovers her hidden sealskin and returns tothe sea, abandoning her human husband and children. ‘I loved you well,’ shesometimes calls, ‘but I loved better my husband and children in the sea.’Unions between humans and faerie creatures rarely turn out well. These aredisturbing tales of constraint and capture, power and powerlessness. And theyare haunted by loss: the selkie’s longing for her own element and the heartacheof man and children left behind.

I wasthinking about this story while I was writing Troll Mill, the second of my fantasy trilogy for children set in aViking-Norway-that-never-was, and I found within it a metaphor for post-nataldepression. (That’s not to pin it down; folk and fairy tales are open to manyinterpretations.) But the thought gave me the heart of my book. Kersten is aseal-woman stolen – and named – by Bjørn, a fisherman. She lives with him inapparent content until one stormy evening she finds her sealskin cloak, racesto the shore and thrusts her new-born child into the arms of the young heroPeer, before hurling herself into the sea. Left literally holding the baby,Peer cannot catch her; he yells a warning to his friend Bjørn, who runs tointercept her –

And Kersten stopped. She threw herself flat and the wet sealskin cloakbillowed over her, hiding her from head to foot. Underneath it, she continuedto move in heavy, lolloping jumps. She must be crawling on hands and knees,drawing the skin closely around her. She rolled. Waves rushed up and sucked herinto the water. Trapped in those encumbering folds, she would drown. ‘Kersten!’ Peer screamed. The body in thewater twisted, lithe and muscular, andplunged forward into the next grey wave.

I wanted there to be anelement of doubt. Is Kersten really a selkie, or is it simply a story the othercharacters make about her, in an attempt to explain what she did, and why?Years earlier, the daughter of a friend and work colleague of mine had killedherself in the grip of post-natal depression, and a great part of the book – Irealised after I’d written it – turned out to be about motherhood and what itdoes to you, and the different ways people cope or don’t cope. I didn’t plan this,it just came out that way. There was Kersten, the mother who goes missing, lostor dead. There was Gudrun, older, capable, hard-working, the nurturing butsometimes short-tempered mother. There was a troll princess, drama-queen motherof the sort of spoiled brat other mothers dread. And there was GrannyGreenteeth, my version of the dangerous English water-spirit Jenny Greenteethwho drags children into the green depths of the stagnant water she inhabits. Sheclaims the motherless half-selkie baby, Ran, as her lawful prey even though thechild will drown. She is the destructively possessive mother.

Peer saw her, or thought he did: Granny Greenteeth in human form,sitting at the bottom of the millpond with Ran in her arms. A greenish lightclung around them. Granny Greenteeth’s hair was waving upwards in a terribleaureole and she bent over Ran, rocking her to and fro.

Granny or Jenny Greenteethis a fresh-water spirit, a nixie not a selkie, and her origin in Englishfolklore is likely to have been as a bogey to frighten children away fromdangerous ponds. Jacob Grimm in his TeutonicMythology (1835) says that the Danish water spirit, the nøkke, wears a green hat and that ‘whenhe grins you see his green teeth’. Grimm adds that ‘there runs through thestories of water-sprites a vein of cruelty and bloodthirstiness which is noteasily found among daemons of mountains, woods and homes… To this day, whenpeople are drowned in a river, it is common to say: “The river-sprite demandshis yearly victim,” which is usually an innocent child.’

Unlikenixies, selkies are not cruel, though they sometimes take revenge on those whohave mistreated them. They are not spirits, but creatures of flesh and bloodlike ourselves, as the Shetland and Orkney islanders who told selkie stories inthe 1940s to David Thomson for BBC radio (and published later in Thomson’s bookThe People of The Sea) knew fullwell. One story Thomson heard in the radio age was told by Shetlander GilbertCharlson, and it couldn’t be plainer about the physicality of the selkie race. Aband of men land on the Ve Skerries (the ‘Holy Skerries’) to stun the sealsthere and skin them alive:

‘Ye’d no sooner stun your seal than you’d set to and skin him, youunderstand, for if you left him there he might come back to life and go backinto the sea while you turned around. T’was hard to be sure if they were deador no, for it’s very hard to kill them…’

The tale was already overa century old, for it is also found in Samuel Hibbert’s Description of the Shetland Islands (1822). Hibbert’s account isjust as graphic:

They … stunned several of them and while they lay stupefied, strippedthem of their skins, with the fat attached to them. They left the nakedcarcasses lying on the rocks, and were about to get into their boats with theirspoils and return to Papa Stour, whence they had come.

As they prepare to leave,a huge swell rises; the men all leap for their boats… The Ve Skerries are thevery ones through which Lieutenant Thomas RN rowed in the 1850s coming back from his cod-fishing expedition,and he described them as “almost covered by the sea at high water, and in thisstormy climate, a heavy surf breaking over them generally forms an effectualbarrier to boats.” So the men are swift to leave: but one is left behind.Unable to bring the boats close enough for him to jump, his friends give up androw for home, knowing he’ll be washed away.

And now the seals return to the skerry, moaning and cryingfor the deaths of their kin; crying even more for those still alive, whowithout their skins can never return to their home in the sea – this glossesthe truth of actual, living, skinned seals still writhing on the rocks... The theone crying the loudest is a female selkie called ‘Geira’ – or ‘Gioga’ in the older version –for her son Hancie has lost his skin and must now be forever exiled.

Seeing the shivering, stranded fisherman fated to diefrom exposure or drowning, Geira offers to carry him on her back all the wayhome to Papa Stour, if in return he will find and restore her son’s sealskin.The man is willing, but he is desperately afraid of the turbulent waves. So heasks her permission to cut slots in the thick sealskin of her shoulders and flanks,two for his hands and two for his feet, so that he can hold on firmly ‘betweenthe skin and the flesh’ and will ‘no slip in tae the sea’. So dear is her sonto Geira that she agrees, and carries the man away through the storm and allthe way back to Papa Stour. The story ends:

‘And this man went across the island in the night, when he landed. Hewalked down by the Dutch Loch and on to Hamna Voe. He made sure his comradeswere sleeping. And he went there to the skeo [a little stone house used for the curing of fish]. And he choseout the longest and bonniest skin out o’ a’ that lay there and took it to theold mother selkie, Geira. It was the skin o’ her son, Hancie, and away wi’ thatshe swam.’

David Thomson: The People of the Sea

So there’s a tale ofco-operation between human and selkie, even though the man was part of a teamslaughtering and skinning the seals. The relationship between the two races isnot an equal one. The men prey upon the seals in order to live – to sell theskins, and make shoes and garments from them. They use the seals, and also theydepend upon them: they owe them. And they’re uneasy about it, uneasy aboutkilling these creatures who seem so much like… people. One more quotation from ThePeople of the Sea, from eighty year-old Osie Fea:

‘It’s no wonder they were thought to be like us,’ he said. ‘For theseals and ourselves were aye thrown together in our way o’ getting a living,and everything we feel, they feel, ye may be sure o’ that.’

‘I wouldna care to benear them,’ said Margaret Fae.

‘I have watchedthem,’ said Osie, ‘as near as I am to you. I have seen a mother out by the SealSkerry when the sea was full o’ wreckage. There was a ship wrecked out by andit was rough, and this wreckage was tumbling her young one about so he couldnawin ashore. I could see the anxiety gazing out o’ her eyes like a woman’s. Thevery same. The very same as a woman’s.’

It is surely from thissense of identification, of empathy and of guilt, that the stories were born.

Picture credits:

The Seal Woman of Kopakonan, Faroes. Read her story on the Faroes website at this link

The Seal Woman of Kopakonan: photo by Annebjorg Andreasen

January 26, 2024

The 'Little Dark People'

In ‘A Book of Folk-Lore’ (1913) the Devon folklorist SabineBaring-Gould recounts three instances in which he and members of his family‘saw’ pixies or dwarfs. I’ll let you read them: In the year 1838, when I was asmall boy of four years old, we were driving to Montpellier [France] on a hotsummer’s day, over the long straight road that traverses a pebble and rubblestrewn plain on which grows nothing save a few aromatic herbs. I was sitting on the box with myfather, when to my great surprise I saw legions of dwarfs about two feet highrunning along beside the horses – some sat laughing on the pole, some werescrambling up the harness to get on the backs of the horses. I remarked to myfather what I saw, when he abruptly stopped the carriage and put me insidebeside my mother, where, the conveyance being closed, I was out of the sun. Theeffect was that little by little the host of imps diminished in number tillthey disappeared altogether. When my wife was a girl offifteen, she was walking down a lane in Yorkshire between green hedges, whenshe saw seated in one of the privet hedges a little green man, who looked ather with his beady black eyes. He was about a foot or eighteen incheshigh. She was so frightened that she ranhome. She cannot recall exactly in what month this took place, but knows it wasa summer’s day. One day a son of mine, a lad ofabout twelve, was sent into the garden to pick pea-pods for the cook to shellfor dinner. Presently he rushed into thehouse as white as chalk to say that while he was engaged upon the task imposedupon him he saw standing between the rows of peas a little man wearing a redcap, a green jacket, and brown knee-breeches, whose face was old and wan andwho had a gray beard and eyes as black and hard as sloes. He stared so intently at the boy that thelatter took to his heels. I know exactlywhen this occurred, as I entered it in my diary, and I know when I saw the impsby looking in my father’s diary, and though he did not enter the circumstance,I recall the vision today as distinctly as when I was a child. In spite of the vivid and detailed nature of these visionsBaring-Gould didn’t believe he or his family had seen anything ‘real’. Hecontinues stoutly: Now, in all three cases, theseapparitions were due to the effect of a hot sun on the head. But such anexplanation is not sufficient. Why did all three see small beings of a verysimilar character? With ... temporary hallucination the pictures presented to the eye are neveroriginally conceived, they are reproductions of representations either seenpreviously or conceived from descriptions given by others. In my case and thatof my wife, we saw imps, because our nurses had told us of them… In the case ofmy son, he had read Grimms’ Tales and seen the illustrations to them.

Rational indeed – though still a little puzzling thatsun-stroke or heat-stroke should in each case have brought on visions of dwarfsor pixies. Perhaps it ran in thefamily. However that may be, Baring-Gould acknowledges that this explanationonly pushes the problem further into the past – ‘Where did our nurses, whencedid Grimm [sic] obtain their tales of kobolds, gnomes, dwarfs, pixies, browniesetc? … To go to the root of the matter, in what did the prevailing belief inthe existence of these small people originate?’ And he answers thus: I suspect that there did exist asmall people, not so small as these imps are represented, but comparativelysmall beside the Aryans who lived in all those countries in which the traditionof their existence lingers on.

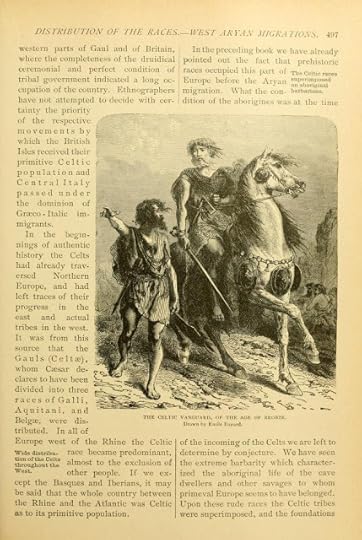

The grim events of the 20th century have taughtus to beware of the word ‘Aryan’, liberally scattered in the introduction tomany a 19th century collection. SirGeorge Dasent, introducing ‘Popular Tales from the Norse’ (his translation ofAsbjornsen and Moe’s 'Norske Folkeeventyr’) includes a section on ‘the Aryanrace’ which according to contemporary anthropological wisdom had spread across Europe‘in days of immemorial antiquity’. In1905, citing the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley as his authority, Charles Squirein ‘Celtic Myths and Legends’ writes confidently of ‘certain proof of twodistinct human stocks in the British Isles at the time of the Roman conquest’.He describes them: the early people who built Britain’s long barrows were‘Iberian’ or ‘Mediterranean’ in origin: ‘a short, swarthy, dark-haired’aboriginal race; but ‘the second of these two races was the exact opposite ofthe first. It was the tall, fair, light-haired, blue- or gray-eyed peoplecalled, popularly, the “Celts”, who belonged in speech to the “Aryan” family …It was in a higher stage of culture than the “Iberians”.’ In the illustration below from a history of the world published in 1897, we see how the heroic Celts were imagined, along with an account of the 'Aryan migration'. And they were supposed to have displaced a different race of indigenous people, driving them almost literally underground.

'The Celtic Vanguard' from 'Ridpath's History of the World', 1897

'The Celtic Vanguard' from 'Ridpath's History of the World', 1897This notion of ‘two races, two cultures’ has beendiscredited. Archaologists and geneticists now agree that Europe has been amelting-pot of racial groups from at least the early Neolithic. European Mesolithichunter-gatherers were neither replaced nor suddenly shunted out; instead, overseveral thousand years, they assimilated both the culture and the genes of agradually diffusing population of Neolithic farmers. It wasn’t until the BronzeAge (says Professor Barry Cunliffe in ‘Europe Between the Oceans, 9000 BC – AD1000’) that sea-faring and trading populations on the on the coasts of Europe,Britain and Ireland, developed the Celtic tongue as ‘an Atlantic façade linguafranca’. Isn't that wonderful? The Celts didn’t ‘come from’anywhere: they were in place already. The Celtic languages evolved because coastal peoples travelled and traded and intermarried and talked to one another. Britain wasn't isolated, it was always an integral part of Europe. So the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould was wrong. There never was a distinctly different race of ‘little dark people’ living on the edges ofa conquering population of tall, fair, confident ‘Aryans’. Nothing to giverise to a belief in a ‘hidden folk’ of pixies, dwarfs or elves. You can see why he liked the idea. It seemed to answer a lotof questions, besides lending to folk-lore a kind of scientific gloss:anthropological ‘truths’ preserved in tales. Many a writer has been honestly misled byit. In Rosemary Sutcliff’s tremendous novel ‘Sword at Sunset’, theRomano-British and nominally Christian hero Artos, fighting off the Saxon invasions in the 3rdcentury AD, takes as his allies ‘the little Dark People of the Hills’, who livehalf-underground in turf-covered bothies, use poisoned arrows and worship theEarth Mother. Their clan leader, the Old Woman, calls Artos ‘Sun Lord’ andtells him: ‘We are small and weak, and ournumbers grow fewer with the years, but we are scattered very wide, whereverthere are hills or lonely places. We can send news and messages racing from oneend of a land to the other between moon-rise and moonset; we can creep and hideand spy and bring back word; we are the hunters who can tell you when the gamehas passed by, by a bent grass-blade or one hair clinging to a bramble-spray.We are the viper that stings in the dark –’

And in the same author's if-anything-even-more-magnificent ‘TheMark of the Horse Lord’, the half-Roman half-British ex-gladiator Phaedrus,masquerading as Midir, Lord of the Dalriata (an actual 4th century AD Scots-Irish Gaelic kingdom),lays down his iron weapons to call upon an Old Man of the Dark People who lives like a badger in ‘a tumble of stones and turf laced together with brambles’ with ‘a darkopening in its side’: [Phaedrus] had heard before ofplaces such as this, where one left something that needed mending, together witha gift, and came back later to find the gift gone and the broken thing mended;it was one of those things no one talked of very much, the places where thelife of the Sun People touched the life of the Old Ones, the People of theHills. Like the bowls of milk that the women put out sometimes at night, inexchange for some small job to be done – like the knot of rowan hung over adoorway for protection against the ancient Earth Magic – like the stealing of aSun Child from time to time.’ This Old Man is ‘slight-boned … with grey hair brushed backfrom his narrow brow, and eyes that seemed at first glance like jetbeads…’ Sutcliff was writing in themid-1960s when the ‘two races’ hypothesis was still widely credited: she wrote with great imaginative empathy. I grew up with these stories and it was easyto be swept along by the idea: these Little Dark People or Painted People, these remnantsof the past clinging to the verge of cultures which had displaced them, werethe historical origin of the fairies. I was sorry for them. Despite Sutcliff’ssympathetic treatment, these marginalised archaic people seem nearlypowerless. Their magic – feared thoughit is – doesn’t really work on the more advanced Sun People. They are spies,not warriors: they creep through the heather with poisoned arrows, killing bystealth. They are in fact natives, withall the baggage that implied in colonial and post-colonial Britain. They mayhelp the heroes, but they can’t bethe heroes. Their time is past.

And in the same author's if-anything-even-more-magnificent ‘TheMark of the Horse Lord’, the half-Roman half-British ex-gladiator Phaedrus,masquerading as Midir, Lord of the Dalriata (an actual 4th century AD Scots-Irish Gaelic kingdom),lays down his iron weapons to call upon an Old Man of the Dark People who lives like a badger in ‘a tumble of stones and turf laced together with brambles’ with ‘a darkopening in its side’: [Phaedrus] had heard before ofplaces such as this, where one left something that needed mending, together witha gift, and came back later to find the gift gone and the broken thing mended;it was one of those things no one talked of very much, the places where thelife of the Sun People touched the life of the Old Ones, the People of theHills. Like the bowls of milk that the women put out sometimes at night, inexchange for some small job to be done – like the knot of rowan hung over adoorway for protection against the ancient Earth Magic – like the stealing of aSun Child from time to time.’ This Old Man is ‘slight-boned … with grey hair brushed backfrom his narrow brow, and eyes that seemed at first glance like jetbeads…’ Sutcliff was writing in themid-1960s when the ‘two races’ hypothesis was still widely credited: she wrote with great imaginative empathy. I grew up with these stories and it was easyto be swept along by the idea: these Little Dark People or Painted People, these remnantsof the past clinging to the verge of cultures which had displaced them, werethe historical origin of the fairies. I was sorry for them. Despite Sutcliff’ssympathetic treatment, these marginalised archaic people seem nearlypowerless. Their magic – feared thoughit is – doesn’t really work on the more advanced Sun People. They are spies,not warriors: they creep through the heather with poisoned arrows, killing bystealth. They are in fact natives, withall the baggage that implied in colonial and post-colonial Britain. They mayhelp the heroes, but they can’t bethe heroes. Their time is past.

Writing in 1913 Baring-Gould doesn’t even allow them the skillsto erect dolmens: They were not, I take it, theDolmen builders – these are supposed to have been giants because of thegigantic character of their structures. They were a people who did not build atall. They lived in caves, or if in the open, in huts made by bending branchesover and covering them with sods of turf. Consequently in folk-lore they arealways represented as either emerging from caverns or from under mounds.

This is to lend to folklore an authority far beyond its scope. Most of the nineteenth century collectors of the fairy talesand folk-lore which we all love so much were driven by nationalist impulses andracial pride. Each sought, as the Grimms did, the pure voice of their own‘folk’. As the century progressed what they in fact uncovered was theinextricably interrelated nature of European folk- and fairy- lore. Despite thenear-impossibility of claiming a particular version of any story as ‘original’,some went on to claim an ultimate ‘Aryan’ heritage for such tales, going so faras to assert that the Aryan master-race originated in Scandinavia – since,clearly, the Nordic peoples were the tallest, blondest and bluest-eyed of thelot. Most of these gentlemen meant only to generate pride in what they saw as their heritage. They did not recognise it as racism - the term had not yet been coined - but racism it was. As folklorists, as lovers of fairy tales, we need to be responsible for the ways we interpret the stories we tell.

While I was researching Mi’kmaq and Algonkin folk-lore for my children's fantasy 'TrollBlood' (HarperCollins 2007), I came across a salutary reminder of how untrustworthy some 19thcentury commentators can be when discussing origins: in a compilation called‘The Algonquin Legends of New England’ (1884) I found the linguist and folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland with a bee in his bonnet about what he claimed had to be a Norse influence on Mi’kmaqstories. Having decided that the Mi’kmaq tales were in effect too ‘noble’ tohave been the product of Native American minds, he made the wildly unsupportedassertion that the Norsemen must havetold stories from the Eddas to the indigenous peoples of what is nowNewfoundland and New Brunswick: that the Mi’kmaq culture-hero Kluskap(‘Glooscap’, in his account) ‘is the Norse god intensified … by far thegrandest and most Aryan-like character ever evolved from a savage mind’. Ialmost dropped the book and was forced to regard it ever after as compromisedand unreliable. If there was any contact at all between Norsemen and the NativeAmerican population in the 10th to 13th centuries (thelikely duration of occasional forays from treeless Greenland for much-neededNorth American timber), the Greenlanders’ Saga suggests that it was violent and short. Butthat’s not the point. The point is the mindset which says ‘this is too good tohave been created by [insert racial group]’.

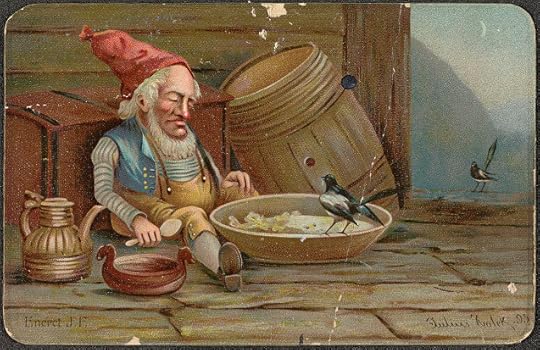

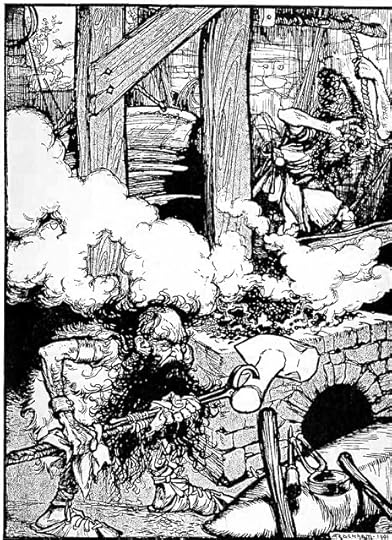

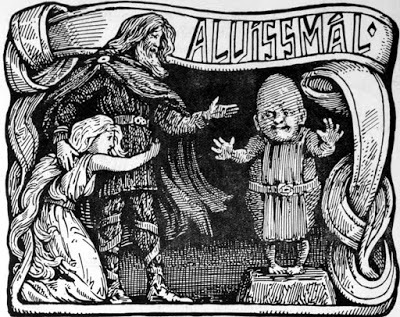

The dwarf Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir.

The dwarf Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir.Returning to the origin of pixies, elves and dwarfs – ifthey’re not a folk-memory of some once co-existing shy and inferior race, whatare they? As Baring-Gould says, thenotion must have come from somewhere. Well, Britain, Ireland and Northern Europe are dotted with burial moundsand barrows. The Irish story of the love of Midir for Étain (the Tochmarc Etaine) states plainly thatMidir is a king of the ‘elf-mounds’, the underworld, and the tale is full ofinstances of death and rebirth. As I argue in an essay called ‘TheLost Kings of Fairyland’ in my book of essays, 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles', fairies have long been associatedwith the dead. In a fascinating essay ‘The Craftsman in the Mound’ (Folk-Lore88, 1977) Lotte Motz discusses the figure of the dwarf as a smith and craftsmandwelling in hills, mounds and mountains, who may be heard hammering away inunderground smithies. Pointing to the many instances of ‘legends of dead rulerswho reside, sometimes in a magic sleep and often with their retinue, within amountain’, she continues: A relation to the dead appears tobelong also to the dwarfs of the Icelandic documents; so the dwarf Alviss[‘All-Knowing] is asked by Thor if he had been staying with the dead, and apoem in a saga tells of a doughty sword which had been fashioned by ‘deaddwarfs’. I would… assert that the mountain dwelling of the smith holds, ratherthan temporary wealth, eternal treasures in its aspect as the mountain of thedead. As if to emphasise his deathly character, like a ghostfleeing to its grave at cock-crow, the dwarf Alviss (the story is from thePoetic Edda) cannot endure daylight but turns to stone at sunrise.

‘The day hascaught thee, dwarf!’ cries triumphant Thor, who like Gandalf in ‘The Hobbit’has kept him talking…

‘The day hascaught thee, dwarf!’ cries triumphant Thor, who like Gandalf in ‘The Hobbit’has kept him talking… It's always been thought dangerous to see fairies. Like the Furies in Greek mythology, if you talked about themat all, you used flattering circumlocutions – the Good People, the Seely Court,the People of Peace. They came from the hollow hills, the land of death, and it was wise to befrightened of them. Maybe thevisions, the ‘legions of dwarfs’, the little green men or pixies which Baring-Gould and hiswife and child separately saw signified something more sinister thanfolk-memories.

After all, sunstroke can kill you.

Picture credits:

Pixie encounter - W. Measom, 1853Nisse eating barley porridge - Wikimedia CommonsThe dwarves Brokkr and Eitri making the hammer Mjölnir - Arthur Rackham - Wikimedia CommonsAlvissmal - Alviss answers Thor - Wikimedia Commons The Celtic Vanguard - Wikimedia Commons

Dolmen, Jersey, 1859 - Wikimedia CommonsPixies - John D Batten - Wikimedia Commons

January 8, 2024

Perilous Voyages

All voyages are voyagesof discovery; all voyages are dangerous. Even in these days when cruise liners arethought of as little more than floating hotels, disaster sometimes strikes. Departingon a voyage is already a little death, a farewell to loved ones who may neverbe seen again, either because of the dangers of the passage or because the travellersmean never to return. To the oppressed and poor of Europe in the nineteenthcentury, America seemed a promised land, a western paradise of plenty andequality. But they had to leave behind all that was familiar if they were tomake a better life across the sea. As a traditional Irish emigrant ballad TheGreen Fields of Canada says:

Oh my father is old and my mother’s quite feeble

To leave their own country it grieves their hearts sore:

The tears in great drops down their cheeks they are rolling

To think they must die upon some foreign shore.

But what matter to me where my bones may be buried

If in peace and contentment I can spend my life?

Oh the green fields of Canada, they daily are blooming:

It’s there I’ll put an end to my miseries and strife.

Anyone who’s stood at the seashore and watched the sun going down over the waves may have wonderedwhat it would be like to seek lands beyond the sunset. Voyages have been associatedwith Otherworld journeys since the days of Gilgamesh (second millennium BCE). Whenhis beloved friend Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh becomes afraid of death. He sets offto the end of the world – to the mountains where the sun rises and sets – andmakes the dark journey through a tunnel called the Path of the Sun, to emerge ina garden of jewelled trees. Here he begs the goddess Siduri for advice on howto cross the ocean to find Uta-napishti, hero of the Flood, who was grantedimmortality by the gods. Siduri tells him to find Ur-shanabi the ferryman, whowith his crew of Stone Ones can take him over the Waters of Death. Theenterprise is about as successful as most Otherworld journeys and Gilgameshlearns the usual lesson, that death is inevitable and had better be accepted.It’s fascinating to find the motif of the ferryman, and of the goddess in theparadisal garden, in this four-thousand year old text. The ferryman Charon, theGarden of the Hesperides, the island of Circe – how long has humanity beenimagining them?

The association of ships and suns is exemplified in the Egyptiansun god Re with his two boats: the sun boat or Mandjet (Boat of Millions ofYears) which carries him from east to west across the sky accompanied byvarious other deities and personifications, and the night boat, the Mesesket,on which the god travels through the perilous underworld from west to east, torise again in the morning.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew…

So speaks the agedUlysses to his companions in Tennyson’s poem. Unwilling ‘to rust unburnished’and die by his own hearth, he sets out for the lands beyond the sunset, home ofthe heroic dead. Yet in the Odyssey, Odysseus has already sailed to theOtherworld. Leaving the island of Circe he reaches the shores of Hades and thegroves of Persephone, fringed with black poplars, where he encounters manyspirits of the dead, including his own mother whom he vainly tries to embrace:

…Three times

I started towards her, and my heart was urgent to hold her,

and three times she fluttered out of my hands like a shadow

or a dream, and the sorrow sharpened at the heart within me.

The Odyssey of Homer,tr. Richmond Lattimore, Harper & Row 1965

In this beautiful red-figure oil jar, we see Charon the ferryman welcoming the soul of a young man into his ferry. Charon gently extends his hand towards a fluttering soul as delicate as a mayfly. It is an extraordinarily tender gesture.

On his death, the Norsegod Baldr is laid by the other gods on a pyre in his ship Ringhorn, which is setalight and pushed out to sea. The Old English poem Beowulf tells how thehero-king Scyld Shefing was laid with many treasures in ‘a boat with a ringedneck’ and sent to sea, where –

Menunder heaven’s

shiftingskies, though skilled in counsel,

cannotsay surely who unshipped that cargo.

Beowulf, tr. Michael Alexander, Penguin1973

Ship burials occur allover the world (for more information visit this link) – throughout all of Europe, Asia and South East Asia. Insome cases people were buried in boats or in boat-shaped coffins, while othersin burials which reference a sea-journey, such as this beautiful burial jar –the ‘Manunggul Jar’ – found in the Philippines’ Tabon Caves, and dated 890-710BCE:

The boatman […] is steering rather than paddling the “ship”. Themast of the boat was not recovered. Both figures appear to be wearing bandstied over the crowns of their heads and under their jaws; a pattern still foundin burial practices among the indigenous peoples in the Southern Philippines.The manner in which the hands of the front figure are folded across the chestis also a widespread practice in the islands when arranging the corpse.

The Tabon Caves, Robert BFox, Manila: National Museum, 1970

InNorthern Europe, high-status people were sometimes buried in their ships, like the king or warrior laid to rest in the East Anglian Sutton Hoo ship burial,circa 700 CE, and the two women in the famous Norwegian ‘Oseberg ship’, thoughtto have been buried in or after 834 CE.

The marvellous Welsh poemPrieddeu Annwfn or ‘The Spoils ofAnnwfn’ (dated by linguistic evidence to around 900 CE) tells of a raid byArthur in his ship Prydwen on the Welsh underworld, Annwfn. Most of the eightstanzas end with a variation on the recurrent line: ‘Except seven, nonereturned’. By ordinary standards the expedition sounds disastrous, but this isno ordinary poem. Fateful, gloomy, mysterious, we gain a vision of a venture bysea to an Otherworld mound or islandwhere a pearl-rimmed cauldron full of the magical life-giving mead of poetry isguarded in a four-peaked glass fortress with a strong door.

The hero Bran (keeperof another magical cauldron which restores the dead to life) is the subject ofone of the traditional Old Irish voyage tales known as immrama, in which a hero or saint sets out for an Otherworld,stopping at numerous fantastic or miraculous islands along the way. These islandshave a more sunlit appeal than that of Annwfn: Bran is invited by a mysteriouswoman to seek for the beautiful EmainAblach or ‘Isle of Women’ where there is peace and plenty and no one isever sick or dies. He puts to sea with twenty-seven companions and three curraghs– nine men in each boat. Eventually reaching the island, Bran’s boat is drawninto port by a ball of magical thread which the queen tosses to him. Each manis paired with a beautiful woman, Bran sharing the bed of the queen, and there they remain, unaware how much time is passing in the real world,until Nechtan son of Collbran becomes homesick and Bran resolves to return home.The queen warns against it, and especially against setting foot on land. When they reach Ireland, so many years have passed that Bran’s name is an ancient legend, and when Nechtan leaps out of the curragh he crumblesto dust. Seeing this, Bran and his companions sail away (presumably back to theIsland of Women) and never return.

The hero Maelduin's is a longer voyage and ahappier homecoming: he's advised by a hermit that he will return home only once he has forgiven his father’s murderer. This he finally does, and makes safelandfall. But on the long voyage he and his companions see such wonders as theIsle of Ants ‘every one of them the size of a foal’; an islandwhere demon riders run a giant horse race; an island of a miraculous apple treewhose fruit satisfy the whole crew for ‘forty nights’; an island of fiery pigs, an island of a little cat; anisland where giant smiths strike away on anvils and hurl a huge lump of red-hotiron after the boat (surely a volcanic eruption?) so that ‘the whole of the seaboiled up’. Here’s a lovely passage:

The Silver-Meshed Net

They went on then till they found a great silver pillar;four sides it had, and the width of each of the sides was two strokes of anoar; and there was not one sod of earth about it, but only the endless ocean;and they could not see what way it was below, and they could not see what waythe top of it was because of its height. There was a silver net from the top ofit that spread out a long way on every side, and the curragh went under sailthrough a mesh of that net.

Diuran, one ofMaeldune’s companions, strikes the net with his spear to obtain a piece:

“Do not destroy the net,” said Maeldune, “for we arelooking at the work of great men.” “Itis for the praise of God’s name I am doing it,” said Diuran, “The way my storywill be better believed; and it is to the altar of Ardmacha I will give thismesh of the net if I get back to Ireland.” Two ounces and a half now was theweight when it was measured after in Ardmacha. They heard then a voice from thetop of the pillar very loud and clear, but they did not know in what strangelanguage it was speaking or what word it said.

The Voyage of Maeldune,‘A Book of Saint and Wonders’, tr. Lady Gregory, Dun Emer Press 1906

I love the way thesestories delight in the marvellous inventions of God (or the poet) and the wondrousthings men find when they set out to cross the illimitable sea.

Stationed on thewestern edge of Northern Europe, the Irish were well positioned to wonder whatmight be beyond the watery horizon. Following a dream of ‘a beautiful islandwith angels serving upon it,’ the 6th century Saint Brendan set offinto the Atlantic in search of Paradise. In a hide boat, a curragh, with twelvecompanions he spent years wandering the ocean from one marvellous island toanother, including a landing upon the back of an amiable giant fish whichallowed him to celebrate Easter there. All nature is included in Brendan’s Christianity:when he says Mass, even the fishes attend ‘and came around theship in a heap, so that they could hardly see the water for fishes. But whenthe mass was ended each one of them turned himself and swam away, and they sawthem no more.’

After years of sailing,and coming near the borders of a hell of ice and fire which sounds suspiciouslylike Iceland, Brendan and his companions reached the Land of Promise, theblessed shore.

…clear and lightsome, and the trees full of fruit on everybough… and the air neither hot nor cold but always one way, and the delightthey found there could never be told. Then they came to a river that they couldnot cross but they could see beyond it the country that had no bounds to itsbeauty.

The Voyage of Brendan,‘A Book of Saint and Wonders’, tr. Lady Gregory, Dun Emer Press, 1906

The immrama combinedelight and discovery as well as spiritual journeys. And in fact it was the practiceof many early monks to set up their cells on remote islands such as the Arans. Saint Cuthbert on Inner Farne would pray all night, standing in thesea. Was it only for the solitude, or was the sea crossing itself a holy actwhich could bring the traveller to the shore of another world? Even before Christianity,were islands – liminally placed between earth and sea, like Lindisfarne, Iona,St Michael’s Mount – already considered holy? And it's worth considering that the rite of baptism is apassing through water to symbolic new life.

The age-old traditionof crossing water to the otherworld recurs in Thomas Malory's Le Morte D’Arthur when Arthur is taken away in a barge to the Isleof Avalon ‘to heal him of his grievous wound’. And he is not the only character to make such apost-mortem or near-post-mortem voyage: the Fair Maid of Astolat, dead Elaine, driftsdown the Thames to Westminster in her black barge.

During the quest for theHoly Grail, Sir Percival’s sister dies, having given a dish of her blood in order to heala lady. Perceval lays his sister’s body...

in a barge, and covered it with black silk; and so the windarose, and drove the barge from land, and all the knights beheld it till it wasout of their sight.

Soon after (in BookXVII Chapter 13), Lancelot is woken from sleep by a visionary voice whichcommands:

‘Lancelot, arise up and take thine armour, and enter intothe first ship that thou shalt find’. And when he heard these words he start upand saw a great clearness about him. And then he lift up his hand and blessedhim, and took his arms and made him ready; and so by adventure he came by astrand and found a ship the which was without sail or oar.

And as soon as he was within that shipthere felt he the most sweetness that he ever felt, and he was fulfilled withall thing that he thought on or desired. Then he said, ‘Fair sweet Father, Jesu Christ, I wot not in what joy Iam, for this joy passeth all earthly joys that ever I was in.’

And so in this joy he laid him down… andslept till day. And when he awoke he found there a fair bed, and therein lyinga gentlewoman dead, the which was Sir Perceval’s sister.

This unsteerable shipof the dead conveys Lancelot to a castle where he will encounter that ultimatesymbol of unknowable holiness, the Grail. Putting to sea in a boat without sailor oars – or for that matter in an overloaded inflatable run by traffickers inthe middle of one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes – is to cast yourself uponthe guidance of God. Such faith must be in the hearts of many of the brave, desperatepeople we call migrants.

In ballads too, as inlife, to sail the sea is to face danger and possible death. The eponymous Wifeof Usher’s Well sends her three sons ‘to sail upon the sea’. Barely three weekslater the news comes that they’ve drowned and the grieving mother tries tobring them back by cursing the elements that caused their death:

“I wish the winds may never cease

Nor fashes [disturbances]in the flood

Till my three sons come hame to me

In earthly flesh and blood.”

The Wife of Usher’sWell, Oxford Book of Ballads, 1969

So they do come home,at Martinmas, the liminal time between autumn and winter ‘when nights are longand mirk’. But their hats are made of the birch bark that grows on the trees ofParadise, and they can stay only one night.

‘I’ll set sail ofsilver and I’ll steer towards the sun’, a girl threatens in the folk song AsSylvie Was Walking, for then ‘my false love will weep for me after I’m gone.’ Asfor the foolish lady who betrays her lover and runs away to sea with aplausible suitor who has promised to show her ‘where the white lilies grow/On thebanks of Italie’ – he turns out to be The Daemon Lover of the title, who halfway over conjures up a storm to sink the ship, crying, ‘I’ll show you where the white liliesgrow/At the bottom of the sea!’

Over countless millenniavoyage tales have explored the marvels of life and the mystery of death. We humanshave always embarked upon hopeful voyages, seeking a new world, a better life, abetter self. But the tales acknowledge that we cannot always be in control. Afterthe fall of Troy, Odysseus wanted to go home, but instead he spent ten longyears wandering the Mediterranean, exposed to storms, shipwrecks and the whimsof the gods. Still, he made it in the end despite the odds. Death is a journeywe’re all going to take, but maybe not yet, not this time, although theferryman is always waiting. One day we willleave our friends behind, set sail of silver, steer for the sun and crossthe ocean to the undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveller returns.

One day… one day.

Picture credits

'The Last of England' - by Ford Madox Ford 1852 Wikipedia

Figure from 'The Chariot of the Sun' - by Peter Gelling & Hilde Ellis Davidson, Aldine, 1972

Red-figure oil jar attributed to the 'Tymbos painter', 500-450 BCE Ashmoleon Musuem Oxford Photo by Carole Raddato Wikimedia

The Manunggal Jar - Photo by Philip Maise - Wikipedia

The Fair Maid of Astolat - by Sophie Anderson, 1870 Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool Wikimedia

The Wife of Usher's Well - by H.M. Brock 1934

Petroglyph - 'The Chariot of the Sun' - by Peter Gelling & Hilde Ellis Davidson, Aldine, 1972

December 1, 2023

The Poem of Finn mac Cumhaill

This wonderful poem attributed to Finn wastranslated by Lady Augusta Gregory in Gods and Fighting Men (John Murray, 1904), and is part of the medieval tradition of poetry in praise of spring and summer (in comparison to the harshness of winter). As to the age of the poem, the Fenian Cycle whichrelates the deeds of Finn mac Cumhaill dates in written form to the 8thcentury. The poem follows a brief account of how Finn received his poetic powers (by accident).

The prophetic, wisdom-giving water of the well of the moon, guarded by three women of thesupernatural Tuatha de Danaan, reminds me of the well or spring of the dwarf Mimirin Norse mythology, from which Odin drank to obtain wisdom and understanding, giving one of his eyes for the privilege; also to the spring of Urđr (fate), guardedby the Norns, three maidens whose daily task was to water Yggdrasil theWorld-Tree with its pure waters. The accidental splash that gets into youngFinn’s mouth comes in addition to a previous adventure when, roasting theSalmon of Knowledge for the poet Finegas, he burns his thumb while ‘puttingdown a blister that rose on the skin’, and sucks the burn to cool it: ‘fromthat time Finn had the knowledge that came from the nuts of the nine hazels ofwisdom that grow beside the well that is below the sea.’ A similar story istold in the Mabinogion about the Welshbard Taliesin.

Whoeverwrote the poem clearly knew and loved landscape and nature.We’re there with him (or her), hearing the rustling of the rushes and the song of thecuckoo, the murmur of ‘the sad restless sea’: a paean of joy to ‘May without fault, of beautiful colours.’

There was a well of themoon belonging to Beag, son of Buan, of the Tuatha de Danaan, and whoever woulddrink out of it would get wisdom, and after a second drink he would get thegift of foretelling. And the three daughters of Beag, son of Buan, had chargeof the well, and they would not part with a vessel of it for anything less thanred gold. And one day Finn chanced to be hunting in the rushes near the well,and the three women ran to hinder him from coming to it, and one of them, thathad a vessel of the water in her hand, threw it at him to stop him, and a shareof the water went into his mouth. And from that out he had all the knowledgethat the water of that well could give.

And he learned the three ways of poetry; and this is thepoem he made to show he had got his learning well:–

“It is the month of Mayis the pleasant time; its face is beautiful; the blackbird sings his full song,the living wood is his holding, the cuckoos are singing and ever singing; thereis a welcome before the brightness of the summer.

“Summer is lessening the rivers, the swift horses arelooking for the pool; the heath spreads out its long hair, the weak whitebog-down grows. A wildness comes on the heart of the deer; the sad restless seais asleep.

“Bees with their little strength carry a load reaped fromthe flowers; the cattle go up muddy to the mountains; the ant has a good fullfeast.

“The harp of the woods is playing music; there is colour onthe hills and a haze on the full lakes, and entire peace upon every sail.

“The corncrake is speaking, a loud-voiced poet; the highlonely waterfall is singing a welcome to the warm pool, the talking of therushes has begun.

“The light swallows are darting; the loudness of music isaround the hill; the fat soft mast is budding; there is grass on the tremblingbogs.

“The bog is as dark as the feathers of the raven; thecuckoo makes a loud welcome; the speckled salmon is leaping; as strong is theleaping of the swift fighting man.

“The man is gaining; the girl is in her comely growingpower; every wood is without fault from the top to the ground, and every widegood plain.

“A flock of birds pitches in the meadow; there are soundsin the green fields, there is in them a clear rushing stream.

“There is a hot desire on you for the racing of horses;twisted holly makes a leash for the hound; a bright spear has been shot intothe earth, and flag-flower is golden under it.

“A weak little lasting bird is singing at the top of hisvoice; the lark is singing clear tidings; May without fault, of beautifulcolours.

“I have another storyfor you; the ox is lowing, the winter is creeping in, the summer is gone. Highand cold the wind, low the sun, cries are about it; the sea is quarrelling.

“The ferns are reddened and their shape is hidden; the cry ofthe wild goose is heard; the cold has caught the wings of the birds; it is thetime of ice-frost, hard, unhappy.”

Picture credit:

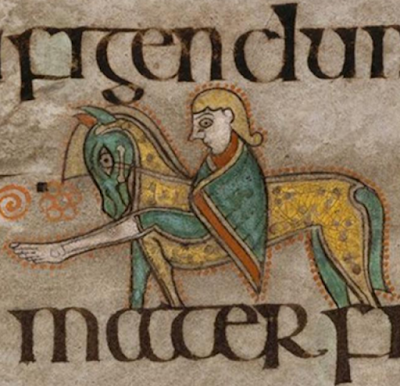

Horseman: detail from the Book of Kells, circa 800 AD: Trinity College Library MS A. I 58. (Wikimedia Commons)

November 18, 2023

'The Tale of the Three Weird Sisters: Lost Fairy Tales' for the Folklore Podcast

This is just to give notice that a week today, on Saturday 25th November at 8pm GMT, I'll be giving an online lecture for the wonderful Folklore Podcast about my search for 'Lost Fairy Tales of 16th & 17th Century England and Scotland'. I'll be talking about fairy tales of which we know nothing but the names, others which have survived by the skin of their teeth, and some which can be inferred from references in poems and plays. It's been a lot of fun to research!

Here's the link to all the lectures: if you'd like to find mine, just scroll down.

http://www.thefolklorepodcast.com/lectures.html

November 16, 2023

Spells of Sleep, Enchanted Apple Boughs

Following myseries of posts on 'Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers' (see links: #1, #2 and #3), here is a sort of appendix: three talesfrom Irish mythology. The Fenian Cycle tells how Finn son of Cumhail once triedto wed a woman of the Sidhe. He was hunting on the mountain Bearnas Morwith his companions of the Fianna, when a great wild pig turned on their hounds and killed most ofthem. Then Finn’s hound Bran got a grip on it. It began to scream, and at thenoise a tall man came out of the hill. He asked Finn to let the pig go. Finn agreed, and the man led them into the hill of the Sidhe and struckthe pig with his Druid rod. At once, it changed into a beautiful youngwoman whom he called Scathach, the Shadowy One. Whether this is the same Scathach who in the Ulster Cycle teaches warrior-craft to Cuchulain on the Isle of Skye, I do not know. Maybe! The extracts that follow are from Lady Augusta Gregory’s translations in Gods and Fighting Men, 1904.)

And the tall man made a great feast for the Fianna, and thenFinn asked the young girl in marriage, and the tall man, her father, said hewould give her to him that very night.

But whennight came on, Scathach asked for a harp to be brought to her. One string ithad of iron, and one of bronze, and one of silver. And when the iron stringwould be played, it would set all the hosts of the world crying and evercrying; and when the bright bronze string would be played, it would set themall laughing from the one day to the same hour on the morrow; and when thesilver string would be played, all the men of the whole world would fall into along sleep.

And it isthe sleepy silver string the Shadowy One played upon, till Finn and Bran andall his people were in their heavy sleep.

And whenthey awoke at the rising of the sun on the morrow, it is outside on themountain of Bearnas they were, where they first saw the wild pig.

In another legend, Branson of Febal also falls asleep to Otherworldly music: