Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 5

December 9, 2022

The Song of the Winter King

The Song of the Winter King

1

Hair of crystal and hands of ice –The snow sieves down above him,He shakes in his palm two silver dice,And whoever sees him loves him.

Now one of the dice is marked with a cross,The other is marked with a ring –And the cross is the seal of paradiseWhere the holy angels sing,

But the ring is the seal of the fairy queen,Queen Morgan is her name,Who dresses in red and elfin green And rules all fair Elfhame.

She and her train come riding byIn cloaks as red as blood:She lashes her seamed and grunting sowWith a switch of elder wood:

‘O young snow king, shake down your dice,Find what the chance shall be!’He shakes them once, he shakes them twice,He shakes them three times three –

O silver, silver fall the moonAnd golden fall the sun –The nine bright planets in the skyLeaped as Queen Morgan won.

Hair of crystal, hands of ice,The white snow falls about him.He drops from his palm the silver dice:Queen Morgan cannot doubt him.

She leads him up, she leads him down,Over the Seven Days,Where toothed heads grin from every pool And quickfire beacons blaze,

She leads him up, she leads him down,Over the Seven Days,Where toothed heads grin from every pool And quickfire beacons blaze,Under the hill, the hollow hill,The peaty darkness waits:She leads him down the fairy roadBehind the narrow gates,

She seats him by a dropping poolWhere ghostly fishes glide:‘And here you’ll stay for evermoreBy the dark fountain side.’

Hair of crystal and hands of ice,He counts the fishes’ scales,He strokes their armoured, slimy sides,Tickles their filmy tails.

2

Now Mary Queen of ParadiseOne day came riding byHer robe was made of fine new woolBright as a summer sky.

Light as a loaf she sat uponA milky-mouthed young lambAs big as any dappled horseThat pulls the plough for man.

She saw the double land lie warmUnder the standing sun – All the white spires of Castle CloudIn the blue distance shone.

Long, long the heath before her stretched,The clear miles shook with heat,Anemones like drops of bloodSprang up beneath her feet,And where she passed, the grinning headsPlopped back into the water.Said she, ‘I would the Queen of FaysWere one of Heaven’s daughters!’And all the harebells rang for her:She left the lamb to graze,Went strolling on the hollow hillsBehind the Seven Days And spied the dice like burning ice,Smoking where they lay.

Swift through the golden grate she stepsAnd down the golden stair:All the white daisies craned their necks To see her enter there;

Under the hollow hills she passed And called the young king’s name.Before the echoes copied her,The fairy challenge came: Queen Morgan as a cloud of bees –Then a red bitch, but lame –Last as a lady tall and proudTo rival Mary’s fame.

‘Why have you come, you Queen of HeavenWithin this land of mine?You may not steal the silver king,For he is none of thine.

‘He shook the dice and fell to me:Body and life and soul,And here he’ll sit for evermoreBy the dark fountain’s bowl.

‘He shook the dice and fell to me:I won the winter king.He shall be mine for evermore,Till these dumb fishes sing.’

‘You won his life but not his soul,’Tall Mary answered free, ‘For that was bought with iron cold Upon a hawthorn tree.

‘Keep what you can, but for my part,What I can do, I will’ – Shakes in her hand the crossways diceThrice, thrice beneath the hill –

And shadows fly, and blazing lightLeaps for the young king’s sake:‘Until the fishes sing, you sleep –But then you shall awake.’

Hair of crystal, hands of iceThe snow sieves down above him.Stone in the crystal cave he lies, And nobody sees or loves him,

And he dreams no dream, but the fishes dreamOf the day they will wake the king –When they poke their red snouts out of the poolAnd open their mouths and sing.

© Katherine Langrish

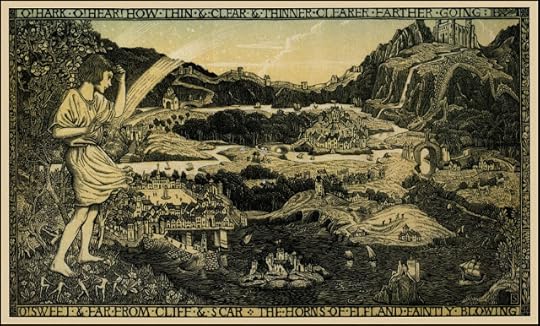

Illustrations

Knight in pen and ink by Aubrey Beardsley, illustration from the Morte d'Arthur, 1909, V&A

Other illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley: facsimile edition of his Morte d'Arthur, Dent 1990.

November 30, 2022

Falling Trees and Invisible Foresters

In his book of travels, ‘In The South Seas’ – subtitled ‘an account of experiences and observations in the Marquesas, Paumotus and Gilbert Islands in the course of two cruises on the yacht Casco (1888) and the schooner Equator (1889)’ – Robert Louis Stevenson relates a number of supernatural stories told to him by the islanders, according to whom the forest-clad slopes were full of ‘souls of the unburied dead, haunting where they fell, and wearing woodland shapes of pig, or bird, or insect; the bush is full of them; they seem to eat nothing; slay solitary wanderers apparently in spite; go down to villages and consort with the inhabitants undetected...’

So much I learned ... walking in the bush with a very intelligent youth, a native. It was a little before noon; a grey day and squally; and perhaps I had spoken lightly. A dark squall burst on the side of the mountain; the woods shook and cried; the dead leaves rose from the ground in clouds, like butterflies; and my companion came suddenly to a full stop. He was afraid, he said, of trees falling; but as soon as I had changed the subject of our talk he proceeded with alacrity.

We’re not told what Stevenson said, that disturbed his companion just before the sudden alarming squall, but I like the fact that he mentions it – and leaves the question of cause and effect open. This is merely the beginning though, as Stevenson goes on to relate more instances in which the sound of falling trees was attributed to some supernatural cause.

Take ... the experience of Rua-a-mariterangi on the isle of Katui. He had a need for some pandanus, and crossed the isle to the sea-beach, where it chiefly flourishes. The day was still, and Rua was surprised to hear a crashing sound among the thickets, and then the fall of a considerable tree. Here must be someone building a canoe; and he entered the margin of the wood to find and pass the time of day with this chance neighbour. The crashing sounded more at hand; and then he was aware of something drawing swiftly near among the tree-tops. It swung by its heels downward, like an ape, so that its hands were free for murder; the speed of its coming was incredible; and soon Rua recognised it for a corpse, horrible with age, its bowels hanging as it came. Prayer was the weapon of Christian in the Valley of the Shadow, and it is to prayer that Rua-a-mariterangi attributes his escape. No merely human expedition [expedient] had sufficed.

When I read this for the first time I was about thirteen; my family and I were then living in a lovely but lonely cottage on a Herefordshire hillside. The nearest village was a mile away down a rough track, the countryside was beautiful, the nights pitch-dark. At the bottom of the field, the track wound between two immensely tall elm trees, through which the wind made a mighty rushing. This story would return to me whenever I had to walk under them alone at night, and shiveringly I would imagine the upside-down corpse swinging towards me out of the branches... but I should have paid more attention. As Stevenson points out, the apparition was a daytime one.

This demon was plainly from the grave; yet you will observe he was abroad by day. And [...] it is no singular exception. I could never find a case of another who had seen this ghost, diurnal and arboreal in its habits; but others have heard the fall of the tree, which seems to be the signal of its coming. Mr Donat was once pearling on the uninhabited isle of Haraiki. It was a day without a breath of wind, such as alternate in the archipelago with days of contumelious breezes. The divers were in the midst of the lagoon upon their employment; the cook, a boy of ten, was over his pots in the camp. Thus were all souls accounted for except a single native who accompanied Donat into the wood in quest of sea-fowls’ eggs. In a moment, out of the stillness came the sound of the fall of a great tree. Donat would have passed on to find the cause. ‘No,’ cried his companion, ‘that was no tree. It was something not right. Let us go back to camp.’ Next Sunday [...] all that part of the island was thoroughly examined, and sure enough, no tree had fallen. A little later Mr Donat saw one of his divers flee from a similar sound, in similar unaffected panic, on the same isle. But neither would explain, and it was not till afterwards, when he met with Rua, that he learned the occasion of their terrors.

In the South Seas: Ch V1

Now of course trees fall in old forests for other reasons than woodcutters or strong winds. They may be rotten; insects may burrow into them and weaken them, but the sound, on a still night or day, must always be impressive. This common experience may explain why a similar folklore of falling trees is found in other wooded parts of the world.

When I was writing ‘Troll Blood’, the third book in my ‘Troll’ trilogy, I spent some time researching the folklore of the First Nations peoples who inhabit the still-extensive North-East Woods of North America. Elizabeth Frame, in ‘A List of Micmac Names’ (1892) name-checks an unseen – yet heard – woodsman known to the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick:

Ke’askunoo’gwejit: A mighty chopper, a fabulous being who cuts down trees; you hear the chopping, the workman is invisible, but the tree falls.

‘A fabulous being’ Frame calls it, and possibly she is trying to convey that this entity would not have been thought of as a spirit: the European soul/body dichotomy was literally foreign to the Mi’kmaq and their neighbours, as was our European sense of being somehow separate from, or above, nature. For the Mi’kmaq, humans, animals, stars, even trees and some rocks were – and I daresay still are – ‘people’ or ‘persons’.

Baptist missionary, ethnologist and linguist Silas Rand (1810-1889) spent 40 years as a pastor with the Mi’kmaq. He spoke Mi’kmaq, Mohawk and Maliseet, along with a shedload of modern and ancient European languages; he compiled a Mi’kmaq/English dictionary, and on his death left over 900 pages of personally recorded tales to be posthumously published as ‘Legends of the Micmac’ (Longmans, Green, 1894). He gives ‘We’gooaskunoogwejit’as a variant of the woodcutter’s name (the words were all written down long before any standardised spelling of the Mi’kmaq language), and describes him as:

An imaginary being who was supposed to cut down trees with one or two blows. The Indians say they sometimes hear in the woods, as it were, the sound of an axe upon a tree, and then see the tree fall, even on a calm day, though no one is visible.

‘An imaginary being’: his description echoes Frame’s construction and may predate it. Both Europeans carefully emphasise their personal disbelief in the phenomenon. But for whatever reason, both take equal care notto call it a spirit.

A third account occurs in ‘In Indian Tents: Stories told by Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Micmac Indians’ (Roberts Brothers, Boston 1897) compiled by Abby Langdon Alger (1850-1915), a Canadian ethnologist and translator. She collected the tales personally, but unfortunately was not very good at naming the storytellers or specifying the group to which they belonged. This account could be either Penobscot or Passamaquoddy:

Seeing a smoke come from the top of a mountain, the children asked the elders what it was, or who could live there, and the fathers told them, ‘That is Al-wus-ki-ni-gess, a tree-cutter, whose hatchet is made of stone. He throws it from him; it cuts the tree and returns to its master’s hand at each blow. One stroke of his hatchet will fell the largest tree. No one ever saw him save Glūs-kabé*, who often goes to the cave to visit him.

In Indian Tents, 51

Unlike the corpse-like spirits of the Paumotu Islands whose arrival is heralded by the sound of a tree falling (but who don’t seem involved in chopping them), none of these three brief North-East Woods stories suggest that the invisible treecutter is dangerous or even frightening – but a feeling of awe, mystery and power is attached to the phenomenon.

Japan is the home of my third example. According to ‘The Book of Yokai’ by Michael Dylan Foster (University of California Press, 2015), the sound of a tree crashing down in a forest may be attributed to a tengu-daoshi. A tengu (which literally means ‘celestial dog’ or ‘heavenly dog’) is, he says, one of the best known of all yōkai (a ‘weird or mysterious creature, a monster or fantastic being, spirit or sprite’) and is thought of as a kind of ‘mountain goblin’ which has morphed over the centuries from an invisible, malevolent spirit, to a winged human/bird-like creature, to a winged monk with a long red nose. Tengu range in their habits from helpful to mischievous to harmful. During the Edo period (c. 1600-1868):

... tengu became increasingly associated with mountain worship and deeply embedded in all manner of local folk belief. They were often invoked as an explanation for mysterious happenings. The sound of a tree falling in the forest, for example, might be attributed to the machinations of a tengu and called tengu-daoshi(tengu knocking-down). A loud guffaw echoing through the forest was called tengu-warai (tengu laugh).

The Book of Yōkai, 135

This illustration of a rather kindly, Gandalf-ish tengu is by writer and artist Matthew Meyer – who blogs about all kinds of yōkai at https://yokai.com. (Well worth a visit.) He provides a more detailed description of the tengu-daoshi, characterising it as ‘an audio phenomenon which occurs deep in the woods [...] the sound of a large tree falling down and the crashing vibrations of it hitting the forest floor. Often it is accompanied by a powerful gust of wind.’ This chimes with Stevenson’s account in which ‘a dark squall burst on the side of the mountain; the woods shook and cried; the dead leaves rose from the ground in clouds, like butterflies’, and his companion declared a sudden fear of ‘falling trees’. Meyer goes on to explain that tengu-daoshi, the phenomenon of trees knocked down by tengu –

is usually encountered only by people who spend much of their time in the mountains, such as woodcutters ... The sound of trees being chopped and crashing to the ground late at night comes from deep within the mountains. It can continue for some time. Occasionally voices can even be heard shouting, ‘Izuko!’ (the equivalent of shouting ‘Timber!’ as the tree falls). Woodcutters sometimes feel creatures shaking their sleeping huts during the night. However in the morning, there is no sign of fallen trees or any evidence whatsoever of what could have made the noise.

This absence of evidence echoes the Paumotu experience of ‘Mr Donat’ and the pearl-divers, when they searched the atoll without success for signs of the tree they had heard fall.

Such striking similarities in narratives so distant from one another – from the north-eastern woods of North America to the Paumotu Islands (known as the Tuamoto today) in the South Pacific – to Japan – begs the question, ‘Can there have been any continuity of tradition, or is this a case of convergence, in which the same conditions produce similar explanations?’ Myself, though without any real evidence – I lean to the first. But who knows? If anyone reading this knows any similar tales of supernatural foresters, I’d love to hear them.

Picture credits:

The Tikehau Islands, part of the Tuamotu group, Polynesia - Louis Choris, c1812

The Fairy Forest at Sunset - Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942)

Old Trees at Dusk (NW Coast) - Emily Carr (1871-1945)

Pine Tree - Ivan Bilibin

Forest - Theodore Kittelsen

October 31, 2022

The Dead in Fairy Tales

The dead are often very present in fairy tales: they have agency from beyond the grave. Some return in bodily form, in gratitude for favours done, or out of concern for the child they have left behind, or more simply to bid farewell to those who loved them. Some come in dreams. And sometimes their presence is more subtly expressed through the trees or flowers which spring from their graves.

The tales in which the hero pays for a dead man’s burial [The Grateful Dead Man: AT E341.1] are at least as old as the apocryphal Book of Tobit, dated 3rd or 2nd century BCE. Tobit, living in Ninevah, piously buries the murdered body of a fellow Jew, but that night he is blinded by sparrow droppings which fall into his eyes as he sleeps in the courtyard. Tobit prays God to release him from misery or else give him merciful death, while in distant Ecbatana, a young Jewish woman called Sarah is in even worse trouble. She’s been married seven times to seven husbands, for on each wedding night the demon Asmodeus arrives and kills the man before the union can be consummated. Accused of their murders, Sarah too prays for either assistance or death. Spotting an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone, God sends the angel Raphael to help both her and Tobit.

Ignorant of this, Tobit sends his son Tobias to fetch some money he deposited years previously with a colleague in a far-off town, Rages (near present-day Tehran). Tobias has never travelled, so Raphael disguises himself as a distant kinsman and offers to guide him. I love the next bit: ‘The boy and the angel left the house together, and the dog came out with him and accompanied them.’ (Please note the little dog in the bottom left-hand corner of this painting!)

We are now well into fairy tale territory: a huge fish jumps from the river to bite Tobias’s foot. The angel tells the boy to split the fish open and take its gall, heart and liver: the heart and liver can be used to fumigate anyone attacked by a demon, while the gall will cure blindness. Raphael guides Tobias to Sarah’s house in Ecbatana and advises the boy to marry her. Having heard the rumours Tobias hesitates, but the angel tells him to place the fishy heart and liver on the incense burner in the bridal chamber: ‘When the demon smells it he will make off and never be seen here any more.’ Success! Asmodeus flees to Upper Egypt where Raphael overtakes and binds him, while the young couple pray and sleep together in peace. Next, Tobias and Raphael go on to Rages, collect Tobit’s silver and return to Ninevah, where you’ll be pleased to know, ‘The dog went in with the angel and Tobias, following at their heels.’ (Faithful little dog!) Using the fish gall, Tobias restores Tobit’s sight and tells his rejoicing parents that their new daughter-in-law is on her way. Finally he offers to reward his faithful companion with half of all that he has won, but Raphael reveals himself: ‘I am Raphael, one of the seven angels who stand in attendance on the Lord and enter his glorious presence.’

Aspects of this story differ from later fairy tales: it names real places (albeit with a shaky grasp of the map), the person who buries the dead man is not the same person who goes on the journey, and an angel accompanies Tobias, not the dead man’s ghost. But the similarities are obvious, and most variants also include the rich young woman whose previous suitors have all been killed, the supernatural agent whose malignity brings about their deaths [The Monster in the Bridal Chamber, AT 507B] – along with the boy’s marriage and offer to split his wealth with his benefactor.

The best known fairy tale version is Hans Christian Andersen's The Travelling Companion. After paying the debts of a dead man, young Johannes is joined on the road by the travelling companion of the title, who helps him marry a princess whose suitors must answer three riddles, or die.

I was entranced as a child by Andersen’s description of the wicked princess who flies out of the castle on black wings to visit her lover – a troll king whose throne is supported on four skeleton horses with harnesses made of glittering red spiders. The travelling companion flies invisibly after her on white swan-wings, slashing her with a birch switch, the stinging blows of which she assumes to be hailstones. He learns the answers to the three riddles, kills the troll and disenchants the princess – who ‘was still a witch and didn’t love Johannes at all.’ Giving Johannes a bottle of liquid and three white swan feathers, the travelling companion tells him to pour the liquid into a tub of water by the marriage bed, cast the feathers on the water and duck the princess three times. She first turns into a black swan with fiery eyes, then into a white swan with a black ring around its neck, and last into a lovely princess who thanks him for breaking the spell. Johannes begs his companion to stay with them for ever, but he replies:

‘No, I must go. I have but paid my debt. Do you remember the dead man whom you protected from wicked men in the church? You gave all you had so he might rest in his grave. I am that dead man.’ And with that he vanished.

A more laconic version is Beauty of the World, told to William Larminie by Patrick Minahan of Mainmore, County Donegal and reproduced in ‘West Irish Folktales’ (1893).

There was a king then, and he had but one son. He was out hunting. He was going past the churchyard. There were four men in the churchyard and a corpse. There was debt on the corpse. The king’s son went in. He asked what was the matter.

The king’s son pays all the money in his purse (five pounds!) for the body to be buried, and shortly after is joined by a red-haired man who, on condition that his wages will be ‘half of all we gain, to the end of a year and a day’, sets out with him to find the beautiful woman ‘with a head as black as a raven’s wing and her skin as white as snow and her cheeks as red as the blood on the snow’ on whom the king’s son has set his heart. Along the way, the red man wins three magical objects from three giants: the ‘dark cloak’ of invisibility, ‘the slippery shoes’, and ‘the sword of light’. And he warns the king’s son that his wished-for bride is ferocious: ‘the woman you are approaching – there is not a tree in the wood on which a man’s head is not hung, except one tree which is waiting for your head.’

Each night this woman, the eponymous Beauty of the World, presents the king’s son with an object – a comb, a pair of scissors – and tells him that if he cannot show it to her next morning, she will have his head. Each night, the young man loses it.

He took hold of the comb. He put it down in his pocket. When they were going to bed, the red man said, ‘See if you have the comb.’ He put his fingers in his pocket. He had not the comb. His tears fell.

When she saw the giant was dead she gave one sweep, and she left not a chair or a table, nor anything on the table she did not make a smash of, so great was her anger.

I like her energy, but the convention in these tales is that the spell or evil spirit which causes the princess’s wickedness can only be driven out by thrashing her. Even Hans Andersen retains a version of this; his travelling companion thrashes the princess as they fly through the air, but he softens the ending when the princess is plunged into water as a kind of baptism. In Beauty of the World the king’s son and her father beat the princess until ‘a blaze of fire came out of her mouth’. They strike again till ‘another lump of fire came out’, and then a third.

‘Now,’ said the red man, ‘strike her no more. Those were the three devils that came out of her. Loose her now; she is as quiet as any woman in the world.’ They loosed her and put her to bed. She was tired after the beating.

‘Do you remember the day you were going past the churchyard? … You had five pounds. You gave them to bury the corpse. It was I in the coffin that day. […] Health be with you and blessing. You will set eyes upon me no more.’

Ah friend, thou blowest upon my bone!

Long have I lain beside the water;

My brother slew me for the boar,

And took for his wife the king’s young daughter.

The shepherd takes the horn to the king, who orders the ground below the bridge to be dug up, revealing the skeleton of the murdered boy. The wicked brother is sewn into a sack and drowned, while the bones are laid to rest in a beautiful tomb.

Bones speak even more directly in Rashin Coatie, a Scots version of Cinderella. A queen dies, leaving her daughter nothing but 'a little red calfy', which however will give her anything she needs. Then the girl's father marries a new wife, an ill-natured woman with 'three ugly dochters':

They took awa’ her a’ her brae claes [all her fine clothes] that her mother had gi’en her, and put a rashen coatie [coat of rushes] on her and gart [made]her sit in the kitchen neuk [nook], and a’body ca’d [everyone called] her Rashin Coatie.

The girl is is treated as a servant and given left-overs to eat, but the little red calf provides ‘good meat’ for her – until the stepmother finds out and has it killed. Rashin Coatie sits down and cries, but then:

The dead calfy said to her: [The dead calf said to her:

‘Tak me up, bane by bane, Take me up, bone by bone,

And pit me aneth yon grey stane, And put me underneath yon grey stone,’]

– and whatever you want, come and seek it frae me, and I will give it you.

The dead mother’s love extends beyond the death of her gift, the red calf – for even as buried bones it still provides advice and the fine clothes necessary for Rashin Coatie to visit the kirk over Yuletide and marry a visiting prince.

Most of the Cinderella versions for children are based on Charles Perrault’s Cendrillon, where the fairy godmother is the heroine’s magical mother-surrogate. Godparents were an insurance policy: they could be expected to help an orphaned godchild. But there is no godmother in the Grimms’ version, Aschenputtel (KHM21). Instead, the heroine plants a hazel tree on her mother’s grave:

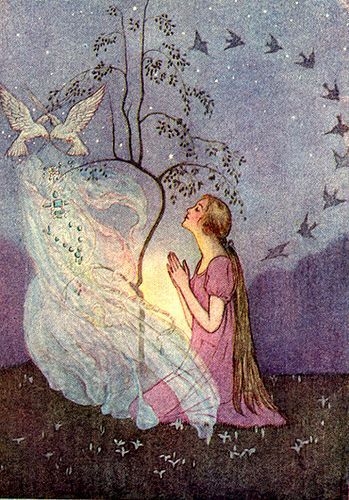

It grew, and became a handsome tree. Three times a day Cinderella went and sat beneath it and wept, and prayed, and a little white bird always came to the tree, and if Cinderella wished for anything, the bird threw down to her what she had wished for.

The white bird is surely her mother’s spirit, or messenger, protecting and nourishing the young woman just as the red calf does for Rashin Coatie. With this supernatural protection, Cinderella is able to call all the birds of the air to help her perform the tasks her stepmother has set (such as picking out lentils from the ashes) and when she needs beautiful dresses for the ball –

She went to her mother’s grave beneath the hazel tree and cried:

‘Shiver and quiver, little tree,

Silver and gold throw down over me.’

Then the bird threw a gold and silver dress down to her, and slippers embroidered with silk and silver.

The tree itself moves, shakes and shivers as the dead mother responds to her child’s need. This is paralleled in The Juniper Tree (KHM 47)in which a childless woman stands one winter day under a juniper tree in her yard, peeling an apple. She cuts her finger, blood falls on the snow, and she wishes for a child ‘as red as blood and as white as snow’. At once she knows it will happen: the months of her pregnancy blend with the blossoming of the year and the flourishing of the juniper, the berries of which she ‘greedily’ eats; in the eighth month she tells her husband to bury her under the juniper if she dies in childbirth. Her son is born white as snow and red as blood. She dies of joy, is buried under the juniper, and the father marries a new wife, by whom he has a daughter, Marlinchen. The stepmother is jealous of her stepson. She murders him, tricks Marlinchen into believing she is responsible, cuts up the child, stews him and gives the meat to her husband to eat. Little Marlinchen sits under the table weeping, and when the meal is done she gathers her brother’s bones (more bones!) in a napkin and lays them under the juniper tree.

Then the juniper tree began to stir itself, and the branches parted asunder, and moved together again, just as if someone were rejoicing and clapping their hands. At the same time, a mist seemed to arise from the tree, and in the centre of the mist it burned like a fire, and a beautiful bird flew out of the fire singing magnificently, and he flew high into the air, and when he was gone, the juniper tree was just as it had been before, and the napkin with the bones was no longer there.

As in the Grimms’ Cinderella, here is a dead mother buried beneath a tree that moves and stirs, with a spirit bird, the child’s soul, flying up from its branches. Via the tree, the mother gives her son second birth and new life, resurrects him in fact, for at the end the once-dead child changes from bird-form to human shape and ‘he took his father and Marlinchen by the hand, and all three were right glad, and they went into the house to dinner, and ate.’ (So we know he’s truly alive: the dead don’t eat.)

We still plant trees as memorials, for they are living beings. And the notion of trees or other green, growing things offering a kind of continued life for those who lie beneath is also found in ballads. Having repented too late of her cruelty to the boy who died of love for her, the eponymous Barbara Allen also dies.

Oh she was buried in the old churchyard,

Sweet William was buried nigh her,

And out of his grave sprung a red, red rose

Out of Barbara’s grew a green briar.

They grew and they grew up the old church tower

Till they couldn’t grow any higher,

And there they tied a true lover’s knot,

Red rose around green briar.

Whether symbolically or in a more real sense, these lovers are united after death. Other dead lovers sometimes return to their living sweethearts, to bid them farewell. The folk song The Grey Cock or The Lover’s Ghost begins with the extraordinary verse:

I must be going, no longer staying,

The burning Thames I have to cross.

Oh I must be guided without a stumble

Into the arms of my dear lass.

Perhaps the ‘burning Thames’ is the supernatural barrier between death and life? Having crossed it, the lover arrives soaking wet at his true love’s window and begs for admittance; she lets him in and they kiss and embrace ‘till that long night was at an end’ when she sees how deadly pale he is. And he admits, ‘Oh Mary dear, the clay has changed me’: he must flee at cock-crow, and they will never meet again until ‘the fish they fly, and the sea runs dry,/And the rocks they melt in the heat of the sun.’

Not all the returning dead are benevolent. The Deacon of Myrká, an Icelandic tale collected by Jón Árnason (1819-1888), tells how a deacon of the church of Myrká in Eyjafjördur had a sweetheart named Gudrún, who lived the other side of the river Hörgá. The deacon always rode a grey-maned horse called Faxi, and one year a few weeks before Christmas he crossed the frozen river to invite Gudrún to a Christmas Eve dance at Myrká, promising to call for her at a particular time to take her there. On the way back to Myrká however, a sudden thaw caused the ice to break beneath him. He fell into the river and though his horse struggled out, he was found drowned with a deep gash at the back of his head made by the ice. Because of the swollen river, no news of his death came to Gudrún. On the day of the dance she was ready and waiting, and hearing a knock at the door went out into the night, where the moon slipped between clouds. Faxi was standing by the door, and a man at his side who without a word lifted her on to the horse and sprang up in front of her. Off they rode, but –

When they reached the Hörgá, the ice-banks were quite high, and as the horse went over the edge, the deacon’s hat was lifted at the back, and Gudrún looked at his bare skull. At that very moment the clouds cleared from the moon, and the deacon said,

‘The moon is gliding.

Death is riding.

Don’t you see a white spot

at the nape of my neck,

Garún, Garún?’

It was a characteristic of Icelandic ghosts to repeat the last word of a clause, and no ghost could pronounce the name of God – which formed the first part of Gudrún’s name. Though alarmed, Gudrún kept silent, and when they came to the church at Myrká they dismounted in front of the lychgate. The deacon said to Gudrún,

‘Wait here for me, Garún, Garún,

While I take my Faxi, Faxi,

Over to the pasture, pasture.’

Off he went. Then Gudrún saw an open grave in the churchyard and became very frightened. She ran to ring the church bell; just as she clutched the rope the deacon grabbed her from behind, tearing the coat from her shoulders, but as the bell began sounding he hurled himself into the grave ‘and the earth rushed in over him as if swept from both sides.’ It was a narrow escape, and Gudrún was never the same afterwards.

Nevertheless, many of the dead are motivated by love. Mothers often return from death in person, if their children need them. The Danish ballad Svend Dyring tells how a mother lying in her grave hears her children crying. With God’s permission, she bursts from her tomb to comfort them – and to threaten the father and stepmother who have neglected them. (You can read the tale here.) There are also many tales of dead children who beg their parents to cease grieving, as in the Grimms’ tale The Little Shroud (KHM 109) in which a child of seven returns.

As the mother would not stop crying, it came one night in the little white shroud in which it had been laid in its coffin, and with its wreath of flowers around its head, and stood on the bed at her feet and said, ‘Oh mother, do stop crying, or I shall never fall asleep in my coffin, for my shroud will not dry, because of all your tears which fall upon it.’

Hearing this, the mother controls her tears and next night the child reappears to tell her that its shroud is almost dry, and it can sleep in peace.

Dead sweethearts, too, complain of the tears shed over them. In the ballad Sweet William’s Ghost a young man killed in the wars appears to his lover Lady Margaret, and asks for the gift he gave her when they plighted their troth. She refuses unless he will first marry her ‘with a ring’. He does, and she gives back the cross she’s worn, but he cannot stay:

Dead sweethearts, too, complain of the tears shed over them. In the ballad Sweet William’s Ghost a young man killed in the wars appears to his lover Lady Margaret, and asks for the gift he gave her when they plighted their troth. She refuses unless he will first marry her ‘with a ring’. He does, and she gives back the cross she’s worn, but he cannot stay: ‘The wind may blow and the cocks they may crow,

And it’s nearly breaking day,

And it’s time that the living would depart from the dead,

My love, I must away, away,

My love, I must away.’

In the ballad of The Unquiet Grave, the living partner mourns for ‘twelvemonth and a day’, after which her dead lover requests her to cease; he cannot sleep for her weeping, and ‘Your salty tears they trickle down/And wet my winding sheet.’

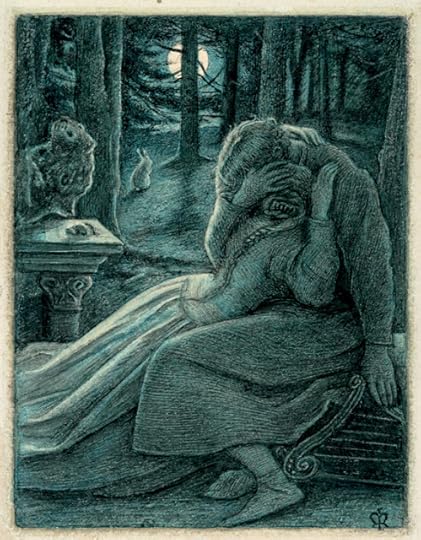

It seems to me that these particular tales and ballads offer to the bereaved not only an understanding of the depths of grief, but the possibility of closure and the permisson not to mourn forever. As even The Wife of Usher’s Well found, you have to let them go. She cast a spell to bring back her three sons drowned at sea, and though they return from the gates of Paradise to visit her, they cannot stay beyond daybreak and the crowing of the cocks, when the youngest bids a sorrowful but final farewell to life and all its chances.

‘Fare ye weel, my mother dear,

Farewell to barn and byre;

And fare ye weel, the bonny lass

That kindles my mother’s fire.’

Picture credits:

The Wife of Usher's Well - HM Brock: ill., The Book of Old Ballads, ed. Beverley Nichols

Tobias and the Angel - Filippo Tarchiani

The Travelling Companion - Anne Anderson

Rashin Coatie - John D Batten

Cinderella and the Hazel Tree - Elenore Abbott

The Juniper Tree - Kay Nielsen

Sweet William's Ghost - Gwen Raverat

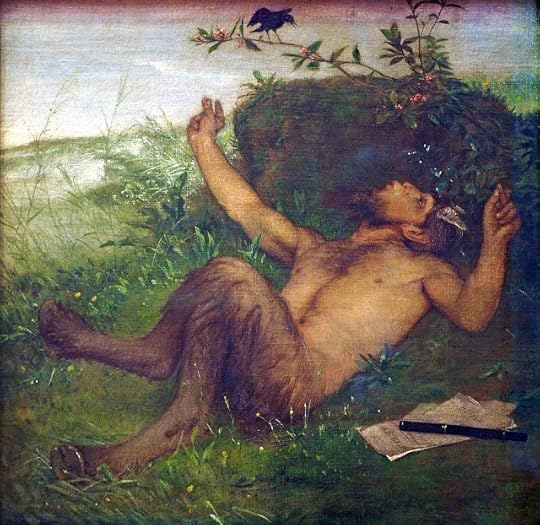

Love - Millais

The Wife of Usher's Well - HM Brock, as above.

October 25, 2022

The Little Children of Dyring: or The Buried Mother

October is a month for talking about ghosts, ghouls and the revenant dead... Here is a story I found in Le Foyer Breton (Emile Souvestre’s 1844 collection of Breton folk and fairy tales). After I’d translated it I realised it’s not Breton at all, but a prose version of a Danish ballad, ‘Svend Dyring’ – known in various 19th century English translations as ‘Childe Dyring’, ‘The Buried Mother’, ‘The Dead Mother’, ‘The Legend of the Stepmother’ and, in Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake, as ‘The Ghaist’s Warning’. (‘Childe’, by the way, is an archaic term for a young nobleman who has not yet won his spurs.)

Dyring went off to an island and married a pretty young girl. He lived with her for seven years and became the father of six children, but then what happened? Death swept through the countryside and his fair, pure lily succumbed.

Off went Dyring to a different isle and chose himself a new wife. Once the wedding was over he brought her back to his home, but alas, her nature was hard and cruel. She walked in, saw the poor little children peeping at her through their tears and roughly rejected them.

She gave them neither ale nor bread, telling them, ‘You shall suffer hunger and thirst.’ She took away their soft blue blankets, saying, ‘You will lie on straw.’ She took away their bright candles, telling them, ‘You will sleep in the dark!’

In the evenings the little children wept, and from her resting place under the earth their mother heard them. Lapped in her cold shroud she heard and resolved to return to them. Coming before Our Lord she begged, ‘Let me go back, to see my little children!’ And she went on pleading and imploring until he gave her permission to revisit this world, on condition she was back in her grave before cock-crow.

Raising heavy, tired limbs she crossed the graveyard wall. Dogs filled the air with their howls as she passed through the village. Coming to her home, she found her eldest daughter sitting on the doorstep.

‘What are you doing there, my dear daughter?’ she asked, ‘and where are your brothers and sisters?’

‘Why do you call me dear daughter?’ asked the child. ‘You’re not my mother! My mother is young and pretty, my mother’s cheeks are white and red, but you – you are as pale as a corpse.’

‘How could I be young and pretty? I’ve come from the land of the dead, that’s why my face is pale. How could I be white and red when I’ve been dead so long?’

She came into her children’s chamber, where they were all crying. She bathed the first and braided the hair of the second. She comforted the third and the fourth, and took the fifth in her arms as if to breast-feed it. Then she said to her eldest girl,

‘Go and ask Dyring to come here.’ And when Dyring came into the room, she cried out in anger,

‘I left ale and bread here, and my children are hungry. I left warm blue blankets and my children sleep on straw. I left bright candles to light them and my children are in darkness. If ever I have need to come back again, bad luck will fall on you! Hark – now the red cock is crowing: all the dead must return to the ground. Hark! – the black cock is crowing and the gates of heaven are opening. And now, hark! – the white cock is crowing. I can stay no longer.’

Ever since that day, whenever Dyring and his wife hear dogs barking they give ale and bread to the children, and whenever they hear dogs howling they are terrified that the dead woman will appear to them once more.

The vigour of the original Danish ballad can be seen in some verses from an 1860 century translation by R C Alexander Prior.

She gave them neither bread nor beer,

‘Hunger and hate will be your cheer.’

She took away their bolsters blue:

‘Bare straw shall be the bed for you.’

She took away their fire and light:

‘In blind-house ye shall sleep all night.’

They cried one evening, till the sound

Their mother heard beneath the ground.

She heard it as in her grave she lay,

‘But go I must, their pain to stay.’

At God’s high throne she bent her knee,

‘Oh let me, Lord, my children see.’

And such her prayer and tale of woe,

That God in mercy let her go.

‘But there on earth no longer stay

When cock shall crow the break of day.’

Out from her chest she stretched her bones,

And rent her way through earth and stones.

As through the street she glided by

Loud all the hounds howled to the sky...

The bursting of the coffin and rending of earth as the dead mother forces her way out of the grave demonstrates both her terrifying power and the strength of her love. Sir Walter Scott includes in his version the apparently irrelevant but haunting refrains usual to Danish ballads, which I think are lovely:

Wi’ her banes sae star a bowt she gae, [With her bones so [?] a bound she gave,

And O gin I were young! Oh that I were young!

She’s riven baith wa’ and marble gray. She’s riven both wall and marble gray.

I’ the greenwood it lists me to ride. In the greenwood I love to ride.]

In ‘Tales of a Wayside Inn’ (1860) a series of narrative poems linked in the style of ‘The Canterbury Tales’, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow includes yet another translation of the ballad, ‘The Mother’s Ghost’, also with refrains:

Svend Dyring he rideth adown the glade,

I myself was young!

There he hath wooed him so winsome a maid;

Fair words gladden so many a heart.

A mother’s love for her children, lasting beyond the grave, clearly held great appeal for 19thcentury sentiment, and the story of the ballad was very widely disseminated. As early as 1814, Robert Jamieson, touching on Scott’s version in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, goes on to mention an Scottish variant which must date from at least the 1770s.

On the translation from the Danish being read to a very antient [sic] gentleman in Dumfriesshire, he said the story of the mother coming back to her children was quite familiar to him in his youth, with all the circumstances of name and place. The father, like Child Dyring, had married a second wife, and his daughter by the first, a child of three or four years old, was once a-missing for three days. She was sought for everywhere with the utmost diligence, but was not found. At last she was observed, coming from the barn, which during her absence had been repeatedly searched. She looked remarkably clean and fresh; her clothes were in the neatest possible order; and her hair, in particular, had been anointed, combed, curled and plaited, with the greatest care. One being asked where she had been, she said she had been with her mammie, who had been so kind to her, and given her so many good things, and dressed her hair so prettily.

Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, pp 318-319

I’ll be talking more about the power of the dead in ballads and fairy tales, both for good and ill, in my next post.

Picture credit:

Woman and child - Richard Redgrave, RA, 1804-1888

October 13, 2022

Uncanny Whistlers

Whistling spirits aren’t the best-known of supernatural folkloric creatures, but they do occur, as I myself can tell you. The 'Seven Whistlers' was a death portent of seven crying birds - which Wordsworth describes in part of a sonnet about a poor old man who nevertheless ‘hath waking empire, wide as dreams’ since ‘rich are his walks with supernatural cheer’:

He the seven birds hath seen that never part,

Seen the seven whistlers on their nightly rounds

And counted them! And oftentimes will start,

For oeverhead are sweeping Gabriel’s hounds,

Doomed with their impious lord the flying hart

To sweep forever on aërial grounds.

'Supernatural cheer' seems an odd way to describe these dread omens, but perhaps the old man enjoyed telling Wordsworth the stories. The Whistler is among the 'fatal birds' Edward Spenser mentions in The Faerie Queene: 'the Whistler shrill, that whoso hears, doth dy.' (Book II, canto XII, verse 36)

I first came across the Seven Whistlers as a child reading one of Malcolm Saville’s well-known-at-the-time ‘Lone Pine’ adventure stories. Seven White Gates is set in Shropshire around and on the hill called Stiperstones. It’s a region full of folklore – Wild Edric and Lady Godda lead the Wild Hunt there, and the Devil sits on the rock formation on top of Stiperstones, known as the Devil’s Chair. Jenny, one of the characters in the story, tells the heroine Peter (yes) about the Seven Whistlers:

‘I remember Dad telling me once – and there are lots of others who’ll tell you too – that the Whistlers are seven mysterious birds somwtimes heard whistling together at night. When you hear them in the night like that it’s bad, and the miners round her often wouldn’t go to work because an accident might happen to them ... it’s horrid. I hate them.’

There’s a rather wonderful 19th century poem about the Whistlers by Alice E. Gillington (1863-1934), who collected folklore and folk songs. The first verse:Whistling strangely, whistling sadly, whistling sweet and clear,

The Seven Whistlers have passed thy house, Pentruan of Porthmeor;

It was not in the morning, nor the noonday’s golden grace,

It was in the dead waste midnight, when the tide yelped loud in the Race;

The tide swings round in the Race, and they’re ‘plaining whisht and low.

And they come from the gray sea-marshes, where the gray sea-lavenders grow;

And the cotton grass sways to and fro;

And the gore-sprent sundews thrive

With oozy hands alive.

Canst hear the curlews’ whistle through thy dreamings dark and drear?

How they’re crying, crying, crying, Pentruan of Porthmeor?

Though the Seven Whistlers were often associated with curlews calling, that didn’t mean they were not still feared:

‘I heard ‘em one dark night last winter,’ said an old Folkestone fisherman. ‘They come over our heads all of a sudden, singing “ewe, ewe,” and the men in the boat wanted to go back. It came on to rain and blow soon afterwards and it was an awful night, sir; and sure enough before morning a boat was upset, and seven poor fellows drowned. I know what makes the noise, sir; it’s them long-billed curlews, but I never likes to hear them.’

Folklore of the Northern Counties, William Henderson, Folk-Lore 1879, 137

So that’s the Seven Whistlers, but there are solitary whistlers too. JG Campbell’s Witchcraft and Second Sight in the Highlands and Islands records a tale from Tiree, ‘The Unearthly Whistle’. A young man was hurrying home late one moonlit night:

His way lay across a desolate moor called the Druim Buidhe (‘Yellow Ridge’), and when halfway he heard a loud whistle behind him but in a different direction from that in which he had come – at a distance, he thought, of above a mile. The whistle was so unearthly loud he thought every person in the island must have heard it. He hurried on, and when opposite an Carragh Biorach (‘the Sharp-Pointed Rock’) he heard the whistle again, as if at the place where he himself had been when he heard it first. The whistle was so clear and loud that it sent a shiver through his very marrow.

With a beating heart he quickened his pace, and when at the gateway adjoining the village he belonged to, he heard the whistle at the Pointed Rock. He made off the road and managed to reach home before being overtaken. He rushed into the barn where he usually slept, and after one look towards the door at his pursuer, buried himself below a pile of corn.

His father was in the house, and three times, with an interval between each call, heard a voice at the door saying. ‘Are you asleep? Will you not go to look at your son? He is in danger of his life and in risk of all he is worth.’

Each call became more importunate, and at last the old man rose and went to the barn. After a search he found his son below a pile of sheaves, and nearly dead. The only account the young man could give was that when he stood at the door he could see the sky between the legs of his pursuer, who came to the door and said it was fortunate for him he had reached shelter, and that he (the pursuer) was such a one who had been killed in the ‘Field of Birds’ in the Moss, a part of Tiree near at hand.

The Gaelic Otherworld, JG Campbell, ed Ronald Black, Birlinn 2005, 282

Another tale of a strange whistler was collected in Gaelic in 1891 by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray from John Robertson of Atholl (born c. 1829), carter and labourer. But ‘The Whistler of Glen Tilt’ was not malevolent:

There was a whistling spirit in Glen Tilt. It could be heard whistling up and down the glen but nobody ever saw it. A farmer called Paul lived in the glen. He had a flock of sheep and when he was out among the sheep Whistler would call to him, ‘Paul! Leave the sheep,’ and Whistler himself would keep the sheep safe. A thief went to steal Paul’s grey sheep and he tied the animal’s legs with garters and carried her off on his back. Whistler shouted, ‘Leave the grey sheep, Paul,’ and Whistler struck the man and he left the sheep. When the folk got up in the morning they found the sheep, tied up just as the thief had left it.

Tales from Highland Perthshire, Stewart Murray: tr. & ed. Robertson & Dilworth, Scottish Gaelic Text Soc. 2008, 139

In Glen Tilt there was a spirit called the Whistler. The shepherds would hear him chivvying along the sheep and they wouldn’t see him, but they could hear the whistle even though they couldn’t see him. One wet night the River Tilt was in spate, and the shepherds said to each other, ‘We won’t see the Whistler tonight’ and the Whistler said, ‘I created the spirit laws. I went round by the bridge and here I am.’

Tales from Highland Perthshire, Stewart Murray: tr. & ed. Robertson & Dilworth, Scottish Gaelic Text Soc. 2008, 287

A black wind blowing around the house and I don’t like getting up in the mornings because of the cold. Last night there was the whistling again, long fluctuating whistles like a farmer to his dog. The time was ten past midnight and it was fainter than before, and only lasted about ten minutes. I have heard it often, louder and longer; it can’t possibly be the wind and is like no owl I ever heard.

It wasn't a curlew either, I was used to hearing their long melancholy cries. They are rare now. And later that month, Sunday December 18th:

Whistling again: it’s a clear still night, midnight. Very clear, shrill and fluctuating; it’s not wind. Either man, bird or ghost!

Maybe it was one of the farmers, though they wouldn’t usually be moving sheep at midnight, or be whistling for so long, so close to the farms. I don't have a good explanation, but I wrote a small poem at the time.

Whistling after dark,

whether man, bird, ghost,

often seems to come

when the stream runs most:

while the beck’s rough and loud

it carries most plain,

the long sheep-dog whistle

again and again,

like somebody walking

unable to sleep,

whistling the lost collie,

the canny dog that knew the sheep.

Picture credits:

Turner: Breakers on a Flat Beach (1835-40), National Gallery, Wikimeda

Turner: Fishing Boats Bringing a Disabled Ship into Port, Tate Gallery

Katharine Holmes: Malham: Trees and Barn, ink and wash: in possession of author.

October 6, 2022

The Two Sisters and the Curse

This sinister story is recorded by John Gregorson Campbell in ‘Clan Traditions and Popular Tales of the Western Highlands and Islands’ (1895). In his notes, Campbell explains that the term ‘dun’, applied to a human being, could be an expression of contempt. He adds that the harvest custom was for the last handful of corn to be cut and taken home by the reaper – usually the youngest – and kept as ‘the harvest maiden’ until the following year; and that old women might go about from house to house begging from the harvesters, and whoever was last to finish reaping would have to maintain one of them for a year. (I wonder if ‘last to finish reaping’ implied ‘more furrows to reap’ and therefore more corn to share? Lastly, I think ‘my sickle will not cut garlic’ must be taken to mean that the sickle is not sharp.

Two sisters were living in the same township on the south side of Mull. One of them who was known as Lovely Mairearad had a fairy sweetheart, who came where she was, unknown to anyone, until one day she confided the secret to her sister, who was called Ailsa, and told her how she dearly loved her fairy sweetheart. ‘And now, sister,’ she said, ‘you will not tell anyone.’ ‘No,’ her sister answered, ‘I will not tell anyone; that story will as soon pass from my lips as it will from my knee!’ But she did not keep her promise; she told the secret of the fairy sweetheart to others, and when he came again, he found that he was observed, and he went away and never returned, nor was seen or heard of ever after by anyone in the place.

When the lovely sister came to know this, she left her home and became a wanderer among the hills and hollows, and never afterwards came inside of a house door to sit or stand, while she lived. The cattle herders often tried to to get near her and persuade her to return home, but they never succeeded further than to hear her crooning a melancholy song which told how her sister had been false to her, and that the wrong done would be avenged on her or her descendants – if a fairy has power. On hearing that Ailsa was married, she repeated, ‘Dun Ailsa is married and has a son Torquil, and the evil will be avenged on her or on him.’ And she sang like this:

My mother’s place is deserted, empty and cold,

My father who loved me is asleep in the tomb,

Friendless and solitary I wander the fields

Since there is none in the world of my kindred

But a sister without pity.

She asked, and I told her, out of the fullness of my joy,

There was none nearer of kin to know my secret:

But I felt, and this brought the tears like rain to my eyes

That a story comes sooner from the lip than the knee.

Then she was heard to utter these wishes:

May nothing on which you have set your expectations ever grow,

Nor dew ever fall on your ground.

May no smoke rise from your dwelling

In the depth of the hardest winter.

May the worm be your store,

And the moth under the lid of your chests.

If a fey being has power,

Revenge will be taken, though it be on your descendents.

Ailsa married and had one son. Her afflicted sister heard of it and added to her song –

Dun Ailsa has married,

And she has a son Torquil.

Brown-haired Torquil who can climb the headland

And bring the seal off the waves,

The sickle in your hand is sharp,

In two swathes you will reap a sheaf.

Whatever other gifts the brown-haired only child of her sister was favoured with, he was a notable reaper, but this gift proved fatal to him. When he grew up to manhood he could reap as much as seven men, and none among them could compete with him. Then he was told that a strange woman was seen coming into the harvest fields in autumn after the reapers had left, and that she would reap a whole field before daylight next morning, or any part of the field that the reapers could not finish that day, and in whatever field she began, she left the work of seven reapers finished after her. She was known as the Maiden of the Cairn (Gruagach a’ chúirn), from being seen to come out of a cairn over opposite.

One evening then, brown-haired Torquil, who desired to see her at work, being later than usual returning home looked back and saw her beginning to reap in his own field. He turned back, and finding his sickle where he had put it away, took it and went after her. Resolving to overtake her, he began to reap the next furrow and said, ‘You are a good reaper, but I will overtake you;’ but the harder he worked, the more he saw that instead of getting nearer to her, she was drawing further away from him. Then he called out,

‘Maiden of the cairn, wait for me, wait for me.’

She said, answering him, ‘Handsome brown-haired youth, overtake me, overtake me,’

He was confident that he would overtake her, and went on after her till the moon was darkened by a cloud; then he called to her,

‘The moon is cloud-smothered, delay, delay.’

‘I have no other light but her, overtake me, overtake me,’ she said.

He did not, nor could he overtake her, and on seeing again how far she was in advance of him, he said, ‘I am weary with yesterday’s reaping, wait for me, wait for me.’ She answered, ‘I ascended the round hill of steep summits, overtake me, overtake me,’ but he could not. Then he said, ‘My sickle would be better for being sharpened, wait for me, wait for me.’ She answered, ‘My sickle will not cut garlic, overtake me, overtake me.’ At this she reached the head of the furrow, finished reaping and stood still where she was, waiting for him.

When he reached the head of his own furrow, he caught the last handful of corn to keep it, as was the custom, it being the ‘Harvest Maiden’, and stood with it in one hand and the sickle in the other. Looking her steadily in the face, he said,

‘You have kept the old woman far from me, and it’s not my displeasure you deserve.’

She said, ‘It is an ill thing on Monday to reap the harvest maiden.’

On her saying this, he fell dead in the field and never more drew breath. The Maiden of the Cairn was never afterwards seen, or heard of; and that was how the sister’s wishes ended.

Picture credit:

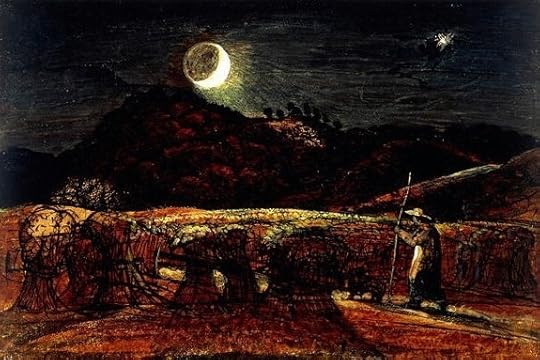

A Cornfield by Moonlight with the Evening Star (c.1830) - sketch by Samuel Palmer, British Museum

September 13, 2022

Defending VILLETTE

Way back in June 2016 I took part in an event for the Brontë Society at Haworth Parsonage called ‘The Great Charlotte Brontë Debate’. Up for friendly yet heated discussion was the question, ‘Whether Brontë’s greatest book was Jane Eyre or Villette?’ Jane Eyre was ably defended by Joanne Harris and Claire Harman, while Lucy Hughes-Hallett and myself took the part of Villette and its heroine Lucy Snowe. Tracy Chevalier presided and saw fair play, while the wonderful Maxine Peake read extracts from both novels. The audience, members of the Brontë Society, were asked to vote for their preferred title before the debate, then vote again afterwards to see if we had changed any minds. This was my contribution, and I began by reading a couple of paragraphs from about a third of the way through Villette, when a violent thunderstorm breaks over the town one night. While her colleagues and pupils in the seminary wake in panic and pray, Lucy reacts differently. ‘Roughly roused and obliged to live,’ she dresses, gets out of the window and sits on the outer ledge with her feet on the sloping roof below.

It was wet, it was wild, it was pitch dark. [...] I could not go in: too resistless was the delight of staying with the wild hour, black and full of thunder, pealing out such an ode as language never delivered to man – too terribly glorious, the spectacle of clouds, split and pierced by white and blinding bolts.

I did long, achingly, then and for four and twenty hours afterwards, for something to fetch me out of my present existence, and lead me upwards and onwards. This longing, and all of a similar kind, it was necessary to knock on the head, which I did, figuratively, after the manner of Jael to Sisera, driving a nail through their temples. Unlike Sisera, they did not die: they were but transiently stunned, and at intervals would turn on the nail with a rebellious wrench; then did the temples bleed, and the brain thrill to its core.

Villette, Chapter 12

This is an absolutely fabulous passage. Dramatic though it is, the thunderstorm Lucy climbs from her window to experience is less terrible than her mental anguish and that extraordinary simile of ‘turning on the nail with a rebellious wrench’. For the really striking thing is that Lucy’s communion with the storm, her delight in the wildness of nature, is not cathartic. It awakens more pain. And the only way she can deal with the pain is to try and kill something in herself: that awakening, that emotional response. There is no room in her cramped life for it: it cannot take her anywhere. It must be kept down. It will not quite die, but while it’s under control she can exist, and existence, not life, is all she can hope for.

‘I, Lucy Snowe, was calm.’ That’s the first thing this heroine tells us about herself, but of course she isn’t calm at all. ‘I had feelings’, she says... She just never allows herself to express them. Why? Because no one cares. She is just as passionate as Jane Eyre, but where Jane from her very childhood lets it out, Lucy shoves it all down out of sight – even out of our sight, for unlike Jane, Lucy makes no bid for our sympathy. If anything her opinion of us is low. She is abrasive and witty. She mocks, keeps secrets from us, makes wry, bitter comments about the gap between her experience and our illusions, satirises our complacence and naïvety.

On quitting Bretton [...] I betook myself home, having been absent six months. It will be conjectured that I was of course glad to return to the bosom of my kindred. Well! the amiable conjecture does no harm and may therefore be left uncontradicted. Far from saying nay, indeed, I will permit the reader to picture me, for the next eight years as a bark slumbering through halcyon weather, in a harbour still as glass [...] A great many women and girls are supposed to pass their lives something in that fashion; why not I with the rest?

Villette, Chapter 4

Villette is a book about constant mental suffering. No one has ever written better about the agony of powerlessness. Lucy is poor and plain. Jane Eyre is poor and plain too, or so we’re told – but we don’t really believe it any more than we believe Rochester is not handsome. We believe it about Lucy, though: she’s too painfully conscious of it. This lack of beauty, her social status and her sex require her to remain silent when she wants to speak, restrain herself when she wishes to act: there is no one even among her few friends in whom she can confide, for that would be to presume upon their affection – which is only affection, not love. She longs for love but she’s clear-sighted and knows the difference. To her friends the Brettons she’s ‘quiet Lucy Snowe’, not so much calm as nearly invisible. She can be drily funny about it, though never without pain. Handsome Dr John Bretton is smitten with shallow Ginevra Fanshawe and imagining Lucy to be hurt by her neglect, he feels the need to assure Lucy that ‘at heart, Ginevra values you’.

‘You are very kind,’ I said briefly. A disclaimer of the sentiments attributed to me burned on my lips, but I extinguished the flame. I submitted to be looked upon as the cast-off and now pining confidante of the distinguished Miss Fanshawe: but, reader, it was a hard submission.

Soon afterwards Lucy does lose patience and breaks out, ‘There is no delusion like your own. [...] On this exceptional point you are but a slave. I declare, where Miss Fanshawe is concerned, you merit no respect, nor have you mine.’ All this does is to cause coolness in their unequal but real friendship and she soon asks his forgiveness, which he warmly grants. But it’s a socially impossible relationship. When you can’t say what you want to say, you can’t be known. Out of kindness, Dr John promises to write to her: when she receives his first letter she draws out the happiness – saves up it for later. Will it be long or short? Cool or kind? She lives from letter to letter, but what’s vital emotional nourishment to her is little to him, and when the letters stop for weeks and she doesn’t know why and can’t ask – she’s like a starving animal in a cage desperate to be fed…

Villette is an extraordinary book. The heroine is in love with two different men at the same time and not a hint of censure. Charlotte Brontë looks us straight in the eye and dares us to blink. ‘This is how it is,’ she seems to say. ‘Accept it.’ Lucy buries Dr John’s letters in a casket in the garden, but is haunted by an image of golden hair growing irresistably out though the cracks of a coffin... Like the image of Sisera ‘turning on the nail with a rebellious wrench’, her feeling for Dr John cannot be killed. It’s folded up tight like a magical tent from the Arabian Nights which, released, could open into a vast pavilion... and at the same time, she’s growing into a different kind of love with her fellow teacher M. Paul Emanuel, the crotchety, fiery little man who sees her, who perceives the fire, the strength and the soul that no one else sees. Perhaps not even herself.

Villette is a pressure-cooker of a book, boiling with desperate, contained, suppressed passion. Every time some of the steam escapes, every time there’s a moment’s relief, it all gets battened down again. Close to the end, Lucy believes she’s lost Paul Emanuel, that he’s sailed for the Indies without a word of farewell. Wandering desolate among lively crowds at a midnight fete in the park, she suddenly glimpses him, and listen to this –

I clasped my hands very hard, and I drew my breath very deep; I held in the cry, I devoured the ejaculation, I forbade the start, I spoke and I stirred no more than a stone; but I knew what I looked on; through the dimness left in my eyes by many nights’ weeping, I knew him.

No sniggering please, at a word that did not then carry the only meaning it seems to have now. Not for another seventeen pages does the pressure cooker finally explode. At last, after she’s waited and waited and waited for him, Paul Emanuel comes to speak to Lucy but Madame Beck tries to prevent him from doing so, and the pressure can’t be contained any longer. Lucy cries aloud,

‘My heart will break!’

Four short, almost banal words: in a burst of anguish Lucy Snowe lets go her iron grip on herself and is recognised, acknowledged. ‘Trust me’, says Paul Emanuel, and his words ‘lifted a load, opened an outlet. With many a deep sob, with thrilling, with icy shiver, with strong trembling, and yet with relief – Lucy weeps.

The overflowing fountain of Lucy’s deeply repressed emotion, and the fiery banishment of Madame Beck by Paul Emanuel, which follows, form the climax of the novel. There is no ‘Reader, I married him’. There’s a brief, very brief interlude of happiness, followed by the famously ambiguous ending, which of course isn’t ambiguous at all unless you want it to be. As if speaking to children, Lucy Snowe says to us, ‘I know you can’t cope with the truth, so here’s the lie. Believe it if you wish. Human kind cannot bear very much reality.’ And she withdraws from us: ‘Farewell.’

Post-script: Which side won the Great Debate? Well, the votes cast before it began strongly favoured Jane Eyre as Charlotte Brontë’s greatest novel, but the votes cast at the end showed a distinct swing towards Villette. Although Jane Eyre still came out top, Lucy Hughes-Hallett and I can claim that we changed some minds, that evening. The Bronte Society's own post on the occasion can be read here: https://bronteparsonage.blogspot.com/2016/06/the-great-charlotte-bronte-debate.html)

Lucy Hughes-Hallett, Katherine Langrish, Maxine Peake, Tracy Chevalier, Joanne Harris and Claire Harman

Lucy Hughes-Hallett, Katherine Langrish, Maxine Peake, Tracy Chevalier, Joanne Harris and Claire HarmanPicture credits

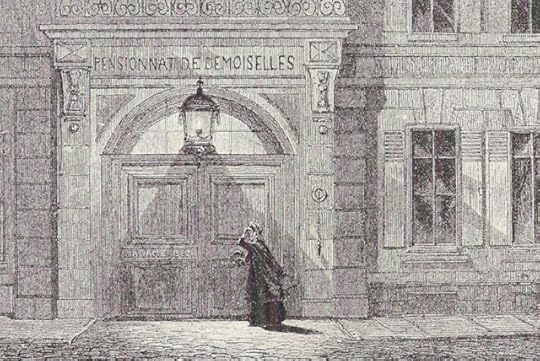

Lucy Snowe at the door of the Pensionnat de Demoiselles - by Edmund Morison Wimperis

Photo of the Great Charlotte Bronte Debate team - Brontë Society

August 23, 2022

Dunsany on the Comma

Another brief extract from the first of the three ‘Donellan Lectures’ which Dunsany gave in 1943 at Trinity College, Dublin. Here he amusingly bewails the tendency of 1940s printers to add superfluous commas to texts. (Modern copy-editors are more likely to remove them!)

[Commas] are little things, but to ignore these fatal pests when speaking of prose is as though I were to speak of the splendours of Africa and never mention the malarial mosquito. Between the African traveller and the ends of all his journeys hovers a veil of these nearly invisible insects, often only irritating, sometimes thwarting his enterprise; so, between every writer and his readers come these little commas bred in the printer’s office, as the anopheles breed in marshes. Certain words are like treacle to them, and any writer who makes use of the word perhaps, must expect them to come to him in swarms. Perhaps I exaggerate, but certainly two will come. The writer puts down, ‘I am going to Dublin perhaps, with Murphy’. Or he writes, ‘I am going to Dublin, perhaps with Murphy’. But in either case these pestilent commas swoop down, not from his pen, but from the darker parts of the cornices where they were bred in the printer’s office, and will alight on either side of the word perhaps, making it impossible for the reader to know the writer’s meaning; making it impossible to see whether the doubt implied by the word perhapsaffected Dublin or Murphy.

I will quote an actual case that I saw in a newspaper. A naval officer was giving evidence before a court, and said, ‘I decided on an alteration of course’. But since the words ‘of course’ must always be surrounded by commas, the printer’s commas came down on them, as surely as the mosquito upon a man’s ear, and the sentence read, ‘I decided upon an alteration, of course’. [...] I saw not long ago a story of my own in a New Zealand paper, where the commas seem to have bred more abundantly than they even do in our climate. I read for instance the words, ‘breathing, of course, ceased, too.’ Although this flight of commas looks absurd, it does no actual harm, but ... further on in the same story I had written, ‘for the surgeons had got his heart going again, and however the soul knew, it returned and got back in time’. But the word however is one of those sticky words which attract the printer’s commas, so down came two of them. It then read, ‘for the surgeons had got his heart going again, and, however,’ but I need read no further, for it is now merely nonsense.

Once when I had written upon this subject in some paper there came a hoot of triumph from a printer’s reader, or one of his friends, and he described how printers had ruined a line of Gray’s Elegy: he said that Gray had written a comma after the third word, the curfew tolls, but that a printer had improved the line by leaving the comma out. I don’t know how he knew, but the moment I read what he wrote I saw the harm the printer had done, and saw for the first time that Gray would never have opened his elegy in the solemn hour when the curfew tolled for the dying day with so jingling a line as the one that has been handed down to us: 'The curfew tolls the knell of parting day'.

Thismust have been, as that friend of printers stated, what Gray wrote:

'The curfew tolls, the knell of parting day'.

NB: I'm sceptical about this. (And how Dunsany can suggest that line is remotely 'jingling', I do not know!) It's true that adding the comma slows the pace to something more stately, transforming the second half of the line into a reverberant adjectival clause. (The tolling curfew does not produce, but IS 'the knell of parting day'.) However, the first lines of almost all the other verses flow smoothly and comma-less: 'Now fades the glimm'ring landscape on the sight' - 'The breezy call of incense-breathing morn' - 'Full many a gem of purest ray serene'... Still, it's interesting to see the difference that can be achieved by the placement of one little comma. [KL]

Picture credit:

Designs by Mr. R. Bentley, for Six Poems by Mr. T. Gray (1775)

August 16, 2022

Dunsany on Prose

Extracts from Lord Dunsany’s first 'Donellan Lecture' given at Trinity College Dublin, in 1943. Here he speaks about prose: its rhythms and its relationship to poetry.

It is usually dangerous for anyone whose gift is one art to attempt to follow another, unless it so happens that he has more than one artistic gift. The pitfalls of following poetry when your gift is prose are obvious enough to be a bye-word, and a very common error is to follow the dramatic art for no better reason that that someone has written a successful novel, and has heard that managers pay better than publishers. Now, the difference between prose and the drama I can show you very easily. For instance the novelist may write: ‘Far away to the left the sun was sinking under the hill, touching the treetops with pink and gold and orange, leaving long layers of crimson across the sky and turning stray clouds to purple’; and a great deal more; but the dramatist will write: “Sun sets left.” The electrician, or whoever is responsible for the lighting in a theatre, will do all the rest. Yeats told me once that a play had been sent to him with the stage direction: ‘A bee buzzes across the evening, leaving a track of silence in its wake.’ The novelist had been at work there.

But between prose and poetry I find it so difficult to define the line, that I have never known at what point prose strays over it. Therefore I cannot tell you where this line goes, nor can I define exactly what poetry is or what prose is; I can only faintly indicate to you the difference by saying to you that in Ecclesiastes there is a melody in the words, and a frequent hurrying past of grand images, which from my earliest years has always suggested poetry to me, and does so still; whereas in the works of Pope there is a certain precision, a scientific and philosophical logic, which has always seemed to me to be of the nature of prose. So the essential thing about poetry is neither rhyme nor metre, and yet all thoughts of a certain elevation appear to demand appropriate words for their dwelling. [...]

Once a man showed me the opening pages of a novel he was writing, and he had something of a name. It began something like this: ‘The mountains stretched away into the blue distance, rising up sheer from the sea, some of them a thousand feet and one of them eleven hundred and twenty.’ I suggested his cutting out the measurements, which he did, but I then saw I could help him no further, for every paragraph had something like this, and I had no time to rewrite the book for him. What was wrong was that altitude, colour and distance, mountains and sea, are all significant, and are materials as useful to the poet as any colours a painter keeps in his tubes; but measurement is arbitrary and has no eternal significance. [...] Of course the book in question was not poetry but a novel, but I believe that the rhythms of prose are able to hold poetry, as Japanese craftsmen inlay gold in their gun-metal. [... ] I think myself that prose is a vessel capable of containing the molten gold of poetry; but it has to be the best prose, or it will crack and the gold will escape. The rhythms of prose are subtler than those of verse: you cannot name the rhythm at once as you name an Iambic. On what then do its rhythms depend? I think they depend upon the spoken word; I think they are suited to our breathing; and just as no weapon or implement can be handily used if not properly balanced, so the weight of a sentence should be adjusted as carefully as that of a spear...

I would refer you to the last chapter of Ecclesiastes, beginning:

1. Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth, while the evil days come not, nor the years draw nigh, when thou shalt say, I have no pleasure in them;

2. While the sun, or the light, or the moon, or the stars, be not darkened, nor the clouds return after the rain:

For English prose has probably risen to few greater heights, especially perhaps the first eight verses, ending:

6. Or ever the silver cord be loosed, or the golden bowl be broken, or the pitcher be broken at the fountain, or the wheel broken at the cistern.

7. Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was: and the spirit return to God who gave it.

8. Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity.

It is this that first made me believe that the boundary between poetry and prose was only an arbitrary line. I will not go into the meaning of it, beyond saying that it is as full of images as a picture gallery, as poetry should be; and indeed, long before much meaning was clear to me in it at all, those images shone for me very clearly, being carried into the sight of my imagination by the melody of the lines, though there is no metre there, and no rhyme, except for those rhymes of which the Old Testament is particularly full, the rhyme of ideas, such for instance, to take a verse almost at random out of the Song of Solomon, Thine head upon thee is like Carmel, and the hair of thine head like purple.

But though prose has not metre, nor rhyme, it has its rhythms, and may share with poetry a certain chiming that is sometimes made with vowels, of which A.E. (George William Russell) was particularly fond, as he told me himself. He told me that, for this reason, his favourite poem in the whole of the Oxford Book of English Verse was that one that begins:

As ye came from the holy land

Of Walsinghame

Met ye not with my true love

By the way as you came?

To hear A.E. himself quote that poem was to understand the theory at once, and the loss of his voice is one that will be hard to repair. But I wander from prose over that invisible line that so slightly divides it from poetry. What is there, then, in the rhythm by which you can test great prose lying so near to poetry that the Muses can hear it from across their frontier and understand its language? Well, there is a proverb that guides us here. And I have never known a proverb that was not wise. This one is: ‘The proof of the pudding is in the eating.’ Prose, therefore, should be read aloud to test its quality, and with great prose it will always be found that the emphasis is balanced upon the rhythm as a rider upon his horse, easily and in the right place.

Picture credit:

Mountain Landscape by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

August 2, 2022

Lord Dunsany on the magic of poetry (2)

"There is a line of Homer, which I forget, which tells of mules going up a mountain pass, and you can hear the clatter of their hooves; and another tells of Apollo going back in anger to Olympus, and his quiver against his armour booms as it goes. And then there is Virgil’s line, though Latin can never quite equal Greek:

Quadrupedante putrum sonitu quatit ungula campum*