Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 7

December 2, 2021

Always Winter and Never Christmas?

Just a quick post. If you feel like snuggling under a blanket with a glass of mulled wine to listen to writer Julia Golding, poet, priest and writer Malcom Guite, and myself discussing Christmas in Narnia and Midwinter in Middle-Earth, please draw your armchair closer to the fire and click on the link below!

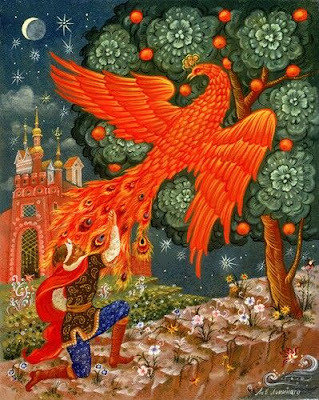

Under the aegis of the Oxford Centre for Fantasy, we cover the presence of Father Christmas in Narnia, tales of Russian frost spirits, CS Lewis's Nativity poems, 'The Father Christmas Letters' written and illustrated by JRR Tolkien for his children - and much much more, in a really enjoyable session during which each of us learned something new.

The link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zk2Y0IQebu4

November 25, 2021

LOVING MAD TOM

The first place I came across the extraordinary old ballad known variously as Loving Mad Tom or Tom o’ Bedlam’s Song was in Rosemary Sutcliff’s delightful children’s book Brother Dusty-Feet, which I must have borrowed from Ilkley Public Library when I was nine or ten. Set in Elizabethan times, it tells the story of orphan Hugh Copplestone who runs away from his unkind aunt’s West Country home with his dog Argos, and joins a band of travelling players. In the middle of Chapter 5 a ‘tall wild figure’ looms up out of the dusk and joins the players’ campfire. He is a Tom-o’-Bedlam, a Bedlam beggar, who sings softly to himself a magical verse which (Sutcliff explains) ‘was a song that all the Tom-o’-Bedlams sang as they came and went along the roads’:

With a host of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander,

With a flaming spear and a horse of air,

To the Wilderness I wander.

With a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end;

Methinks it is no journey.

Soon after, in a firelit ritual, the Tom-o’-Bedlam gives Hugh ‘seisin of the road’.

Not all very tall people look like kings, but this one did, at least to Hugh; the king of a lost country. […] He leaned down suddenly to stare into Hugh’s face, his mad dark eyes blazing in the firelight. ‘Have you kept your vigil?’ he demanded. ‘Have you kept it alone, with none but the stars and the Ancient Ones for company?’

Hugh assents, and the Tom-o’-Bedlam uses his dagger to cut a small square of turf which he places in Hugh’s hands.

‘Now swear fealty to the Brotherhood. Swear by the white dust of the road, and the red fire at the long day’s end, and by the thing that always lies over the brow of the next hill.’

The turf felt crumbly and damp in Hugh’s hands, and faintly warm from the fire; and rather breathlessly, he swore fealty.

‘So,’ said the Tom-o’-Bedlam. ‘That is your Seisin. Seisin of the Road; Seisin of the Brotherhood.’

He drew himself up to his full splendid height, and stood looking down at the gatherine round the fire. Then he dropped the dagger on the trampled turf, where it stuck point down, quivering and gleaming in the light of the flames.

And before it had stopped quivering, he turned away, flinging up his arms to the night sky with a strange wild gesture that made his ragged sleeves seem like wings; and als though he had suddenly lost interest in the whole thing, wandered off into the darkness. As he went, they heard him singing again:

‘With a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end;

Methinks it is no journey.

I loved Brother Dusty-Feet, and Tom-o’-Bedlam’s song was a strong enchantment. I had a good memory for verse, and it stuck. A few years later in my teens, I came across the whole poem in English and Scottish Ballads edited by Robert Graves, and around about the same time, the folk-rock band Steeleye Span released an album Please to See the Kingcontaining a song called Bedlam Boys which name-checked Tom-o’-Bedlam and sounded very similar, yet didn’t have the verses I remembered so well from Brother Dusty-Feet. Of course I knew ballads were found in many variants, so I assumed this was the reason – but it seemed odd that Steeleye Span would choose one that left out such wonderful lines.

But there I left the puzzle – if it was a puzzle – for more than twenty years until, married and living in America, my husband and I were invited to a regular folk-music session hosted by friends in their home. One evening I asked if anyone there could perform Tom-o’-Bedlam and lo and behold! a couple of very good musicians promptly gave a great rendition of Steeleye Span’s Bedlam Boys.

‘You know,’ said I as they finished, ‘I’ve always wondered why that version doesn’t have the wonderful lines about the host of furious fancies and the knight of ghosts and shadows. I know it exists; I remember reading it in Robert Graves’ book of English and Scottish ballads.’ The two guys who’d performed it grinned, and one of them suggested that Graves had probably written those lines himself, as they were obviously far too good to be true!

I was rather cast down. I couldn’t argue, having no proof, but although he might have had the poetic power to do it, and even the urge – Graves sometimes did rewrite other poets’ work in order to ‘correct’ their ‘faults’ – I didn’t think he would have meddled with an old ballad and passed it off as original. Still, there again it rested, only now whenever I thought of Loving Mad Tom, there was this question mark hanging over it.

Move on another couple of decades. I’m reading one of Rudyard Kipling’s collections of short stories, Debits and Credits. One story, The Propagation of Knowledge, concerns the schoolboy characters of Stalky & Co. in whose exploits Kipling exaggerates and glorifies the events and characters of his own schooldays. In this particular tale the short-sighted and bookish Beetle (based on Kipling himself) discovers an old book in the school library called Curiosities of Literature.

This evening he fell upon a description of wandering, mad Elizabethan beggars, known as Tom-o’-Bedlams, with incidental references to Edgar who plays at being a Tom-o’-Bedlam in Lear, but whom Beetle did not consider at all funny. Then, at the foot of a left-hand page, leaped out on him a verse – of incommunicable splendour, opening doors into inexplicable worlds – from a song which Tom-o’-Bedlams were supposed to sing. It ran:

With a heart* of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander,

With a burning spear and a horse of air

To the wilderness I wander.

With a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney,

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end –

Methinks it is no journey.

He sat, mouthing and staring before him, till the prep-bell rang…

There can be little doubt that this is the genuine experience of the young Rudyard Kipling, for the Tom-o’-Bedlam poem itself serves no further purpose in the story. Instead, Beetle and his friends ransack the book for other fascinating scraps of information – such as the theory that Bacon wrote Shakespeare – with which they can tease, provoke and distract their teachers.

Curiosities of Literature is a real book written by Isaac D’Israeli, father of Benjamin Disraeli, published in several volumes between 1791 and 1823. I went hunting online and found the lonely second volume of a three-volume set published in 1881 by Frederick Warne, going cheap. I snapped it up, and there at the foot of a left-hand page, just as Kipling describes, is the whole poem with that magical final verse. And more! D'Israeli introduces the ballad with a lengthy essay in which he describes this ‘race of singular mendicants’ whom he claims ‘appear to have been the occasion of creating a species of wild fantastic poetry’ (my italics). The resources of Bedlam (Bethlehem Hospital for the insane, founded 1247) were so limited that if the friends and relations of those it sheltered could not pay to feed and clothe them, they were released to wander abroad as beggars, ‘chanting wild ditties and wearing a fantastical dress to attract the notice of the charitable.’ The Acadamy of Armoury, compiled by Randal Holme prior to 1688, describes this costume in more detail and with some scepticism:

The Bedlam has a long staff, and a cow or ox-horn by his side; his clothing fantastic and ridiculous; for being a madman, he is madly decked and dressed all over with rubins [ribbons], feathers, cuttings of cloth and what not, to make him seem a madman, or one distracted, when he is no other than a wandering and dissembling knave.

Numbers of ordinary rogues adopted this ploy. In a coney-catching* pamphlet, English Villanies (c. 1608), Thomas Dekker complains of those who pretended madness to ‘work upon the sympathy … or terrify the easy fears of women, children and domestics’ who ‘refused nothing to a being who was as terrific to them as “Robin Goodfellow” or “Raw-head and Bloody-bones”’ that came ‘whooping, leaping, gambolling, wildly dancing, with a fierce or distracted look.’ And he records the canting patter of these real or pretended Tom-o’-Bedlams:

‘Now dame, well and wisely, what will you give poor Tom? One pound of your sheep’s-feathers to make poor Tom a blanket? or one cutting of your sow’s side, no bigger than my arm; or one piece of your salt meat to make poor Tom a sharing horn; or one cross of your small silver, towards a pair of shoes; well and wisely, give poor Tom an old sheet to keep him from the cold; or an old doublet and jerkin of my master’s; well and wisely, God save the king and his counsel.’

These beggars were also known as Abraham men. In a second pamphlet, The Belman of London, also 1608, Dekker has another shot at them: 'Of all the mad rascals (that are of this wing) the Abraham-man is the most fantastick: The fellow (quoth this old Ladye of the Lake unto me) that sat half naked at table today, is the best Abraham man that ever came to my house, and the notablest villaine: he sweares he hath beene in Bedlam, and will talk frantickly of purpose; you see pinnes stucke in sundry places of his naked flesh, especially in his armes, which paine he gladly puts himselfe to [...] he calls himself by the name of poore Tom, and comming nere any body, cries out Poore Tome is a colde...'

D’Israeli quotes from ‘a manuscript note transcribed from some of [John] Aubrey’s papers’:

‘Till the breaking out of the civil wars, Tom-o’-Bedlamsdid travel about the country; they had been poor distracted men, that had been put into Bedlam, where recovering some soberness [sanity], they were licentiated to go a-begging; ie., they had on their left arm an armilla, an iron ring for the arm, about four inches long… They could not get it off; they wore about their necks a great horn of an ox in a string or bawdry, which, when they came to a house, they did wind, and they put the drink given to them into this horn, whereto they put a stopple. Since the wars I do not remember to have seen any one of them.’

All this led me (and D’Israeli) to consider the character of Edgar in King Lear, a play that first appeared in print in 1608 about the same time as Thomas Dekker’s coney-catching pamphlet English Villanies. Edgar, the true son of the Duke of Gloucester, accused by his illegitmate brother Edmund of contemplating parricide, disguises himself as one of the Bedlam beggars:

… who, with roaring voices

Strike in their numbed and mortified arms

Pins, wooden pricks, nails, sprigs of rosemary

And with this horrible object from low farms,

Poor pelting villages, sheep-cotes and mills

Sometime with lunatic bans, sometimes with prayers

Enforce their charity. ‘Poor Turlygood, poor Tom.’

King Lear, Act 2 Sc. 2

Appearing to Lear in the storm, he goes into floods of lilting, frenzied, poetic prose:

‘Who gives anything to poor Tom, whom the foul fiend hath led through fire and through flame, through ford and whirlpool, o’er bog and quagmire; that hath laid knives under his pillow and halters in his pew, set ratsbane by his porridge, made him proud of heart to ride a bay trotting horse over four-inched bridges, to course his own shadow for a traitor. Bless thy five wits, Tom’s a-cold! Oh, do, de, do, de, do de. Do poor Tom some charity, whom the foul fiend vexes. There could I have him now, and there, and there again, and there.’

King Lear, Act 3, Sc. 4

‘An itinerant lunatic,’ says D’Israeli, ‘chanting wild ditties, fancifully attired … a mixture of character at once grotesque and plaintive …It is probable that the character of Edgar … first introduced the conception into the poetical world,’ and he claims that the composition of Tom-o’-Bedlam songs became for a while fashionable ‘among the wits’ of the later 17th century. This one however, the subject of his essay, is of more ancient date and ‘fraught with all the wild spirit of this peculiar character’:

Tom-o’-Bedlam’s Song

From the hag and hungry goblin

That into rags would rend ye,

All the spirits that stand by the naked man

In the Book of Moons defend ye!

That of your five sound senses

You never be forsaken,

Nor travel from yourselves with Tom

To beg your bread and bacon.

Chorus:

Nor never sing any food any feeding

Money, drink or clothing,

Come dame or maid,

Be not afraid,

For Tom will injure nothing.

Of thirty bare years have I

Twice twenty been enragèd;

And of forty been

Three times fifteen in durance soundly cagèd.

In the lovely lofts of Bedlam

In stubble soft and dainty,

Brave bracelets strong, sweet whips, ding dong,

And a wholesome hunger plenty.

And now I sing, etc

With a thought I took for Maudlin

And a cruse of cockle pottage,

And a thing thus tall, sky bless you all,

I fell into this dotage.

I slept not till the Conquest,

Till then I never wakèd,

Till the roguish boy of love where I lay

Me found, and stript me naked.

And now I sing, etc

When short I have shorn my sow’s face

And swigg’d my hornèd barrel,

In an oaken inn do I pawn my skin

In a suit of gilt apparel.

The moon’s my constant mistress

And the lovely owl my marrow

The flaming drake and the night-crow make

Me music to my sorrow.

While I do sing, etc

The palsie plague my pulses

When I prig your pigs or pullen [hens];

Your culvers [doves] take, or matchless make

Your chanticleer and solan [gander];

When I want provant, with Humphrey

I sup, and when benighted

I repose in Pauls with waking souls

And never am affrighted.

But I do sing, etc

I know more than Apollo,

For, oft when he lies sleeping

I behold the stars at mortal wars

And the rounded* welkin weeping.

The moon embraces her shepherd

And the Queen of Love her warrior;

While the first does horn the stars of the morn,

And the next the heavenly farrier.

While I do sing, etc

With a heart* of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander,

With a burning spear and a horse of air

To the wilderness I wander,

With a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney;

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end;

Methinks it is no journey!

So there it is! There’s the song and there is the verse I read and loved as a child* in Rosemary Sutcliff’s Brother Dusty-Feet: proof that whoever wrote them, it wasn’t Robert Graves and the suggestion that he might have passed off some of his own lines as Jacobean poetry can be completely dismissed. (He did dive down a rabbit-warren of alternative versions and speculative reconstructions in a 1927 essay, Loving Mad Tom, published in The Crowning Privilege, 1955: but he was up-front about it.)

D’Israeli’s source was ‘a very scarce collection entitled Wit and Drollery (1661). Graves attributes the title Loving Mad Tom to a 1683 edition of the same collection – which I’m unable to verify. However, the version Graves published in English and Scottish Ballads is subtly different from D’Israeli’s. It contains two extra verses, sourced from the earliest known version of Tom-o’-Bedlam: a manuscript book belonging to Giles Earle, a friend of the musicianThomas Campion, dating to 1615.

Nothing much seems to be known about Earle other than that he was an enthusiast who collected songs, music and lyrics in his commonplace book, Giles Earle His Booke, which was edited by the composer Peter Warlock and post-humously published in 1932. Here indeed are the two verses missing from D’Israeli’s version. They come directly before and after the verse about the host of furious fancies.

The gipsies Snap and Pedro

Are none of Tom’s comradoes,

The punk I scorn and the cut-purse sworn

And the roaring boy’s bravadoes.

The meek, the white, the gentle

Me handle, touch and spare not

But those that cross Tom Rhinoceros

Do what the panther dare not.

***

I’ll bark against the Dog-Star,

I’ll crow away the morning,

I’ll chase the moon till it be noon

And make her leave her horning,

But I’ll find merry mad Maudline,

And seek whate’er betides her,

And I will love beneath or above

The dirty earth that hides her.

Stepping back a little – and taking into account the role of Tom-o’-Bedlams in King Lear – it’s worth wondering who wrote this song; or possibly touched it up. Robert Graves believed it had ‘obviously been rewritten by an educated person: hence the references to Venus’s love affair with Mars, when she was unfaithful to her husband Vulcan, “the Heavenly Farrier”, and to the Moon-goddess Selene’s love affair with Endymion, the shepherd of Mount Latmos … though already married to Phosphoros, the Morning Star.’ More intriguingly, Graves suggests that the ballad ‘was probably sung in a Bankside theatre, because “Sky bless you all” is substituted for “God bless you all”; the Lord Chamberlain having forbidden God’s name to be taken in vain on the stage.’

I checked: and this statute ‘for the preventing and avoiding of the great abuse of the Holy Name of God in Stage plays’ dates from 1606 but was not strictly enforced until Sir George Buck became Master of the Revels in 1610 – a period which neatly brackets the 1608 date of the first printed ‘Quarto’ edition of King Lear.

Graves comments further that ‘No other play of that period, except King Lear, is known into which Loving Mad Tom could have been introduced’ – and speculating that it may have been sung by Edgar after his decision to disguise himself as ‘Poor Tom’, he adds that ‘if it does indeed come from King Lear (though not necessarily written by Shakespeare), it will have given the scene-shifters time to prepare the stage for:“Before Gloucester’s castle: Kent in the stocks.”’ But this cannot be the case; Kent is put in the stocks well before Edgar makes his entrance. A more likely moment for it to be sung would be in Act 3, between scenes 3 and 4. Scene 3 is a brief exchange between Gloucester and his wicked son Edmond, indoors in Regan’s castle. In contrast, Scene 4 is set outside in the storm on the blasted heath, as Lear, Kent and the Fool seek shelter in a hovel – likely placed at the back of the deep Jacobean stage. In his Tom-o’-Bedlam guise, Edgar is already concealed in the hovel and frightens the Fool, who cries: ‘Come not in here, nuncle! Here’s a spirit. Help me, help me!’

But this is Edgar’s first appearance asPoor Tom; wouldn’t it be more effective to have him come on to the empty stage in his mad rags, and sing Tom-o’-Bedlam’s song before disappearing into the hovel as Lear and his companions arrive? It would give the audience a good sight of him in this guise, and then – knowing where he’s hidden – they could anticipate the shock of his discovery.

Impossible to say it ever happened. Still, no less a personage than the American professor and literary critic Harold Bloom believed that this hauntingly strange ballad has something of Shakespeare’s touch. In his book How to Read and Why (2000), he called Loving Mad Tom ‘the greatest anonymous lyric in the language’, and of the verse which begins, ‘I know more than Apollo’ he writes:-

To know more than the sleeping sun god, Apollo, is also to know more than the rational. Tom looks up at the night sky of falling stars … and contrasts these battles to the embrace of the moon, Diana, with her shepherd-lover Endymion, and of the planet Venus with her warrior, Mars. A mythological poet, Mad Tom is also a master of intricate images: the crescent moon enfolds the morning star within the crescent horns, while the Farrier, Vulcan, husband of Venus, is horned in quite another sense, being cuckolded by the lustful Mars. …The stanza is magical in its effect, adding strangeness to beauty…

Bloom adds, ‘I think I hear Shakespeare himself in the extraordinary transitions of the next stanza, in the sudden tonal drop into tenderness of the fifth and sixth lines, followed by the defiant roar of lines seven and eight’

The gipsies, Snap and Pedro

Are none of Tom’s comradoes,

The punk I scorn and the cutpurse sworn

And the roaring boy’s bravadoes

The meek, the white, the gentle

Me handle, touch and spare not;

But those who cross Tom Rhinoceros

Do what the panther dare not…’

Who could this poet be, he wondered, but Shakespeare? (Here is Harold Bloom talking about the poem in an interview on Youtube.)

For after all, so much of King Lear is about madness and sadness, and poverty and beggars and fools, and the companies of ‘poor naked wretches’ who, in Lear’s self-accusatory words, must ‘bide the pelting of this pitiless storm’ –

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this.Take physic, pomp,

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

The persistent relevance of these words should give us all pause… Anyhow, I too like to think it’s at least possible that Shakespeare touched up – transformed – a street ballad about Tom-o’-Bedlams for a performance of King Lear.

But what about the Steeleye Span song, to which they gave the title Bedlam Boys? Well, it turns out not to be the same song at all. Remember Isaac D’Israeli’s claim that Shakespeare’s Edgar/Poor Tom prompted a whole fashion for songs written in his mad character? If true, it only adds to the likelihood of Tom-o’-Bedlam’s Song having been sung in the play; why should so many people imitate the ballad otherwise? For imitate it they did.

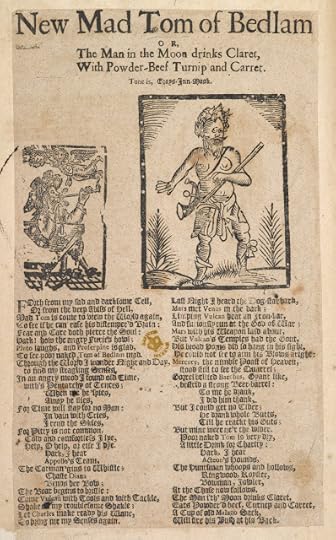

Many more can be visited at this link. Isaak Walton mentions William Basse (c.1583-1653), a minor poet known chiefly for an elegy on Shakespeare, as having written a ‘Tom o’ Bedlam’ song; this one, published by Bishop Percy in his influential Reliques of English Poetry (1765), may be his. It begins:

Forth from my sad and darksome cell,

Or from the deepe abysse of hell,

Mad Tom is come into the world againe

To see if he can cure his distempered braine.

Feares and cares oppresse my soule;

Harke, howe the angrye Fureys houle!

Pluto laughes, and Proserpine is gladd

To see poore naked Tom of Bedlam madd.

Through the world I wander night and day,

To seeke my straggling senses,

In an angrye moode I mett old Time,

With his pentarchye of tenses;

When me he spyed, away he hyed,

For time will stay for no man:

In vaine with cryes I rent the skyes,

For pity is not common.

This is pretty bad verse, but you can see how in the second stanza the poet has reverted to the swinging rhythm and internal rhyme-scheme of the older poem. The same is true of a deliberately satirical version written by the ‘witty Bishop Corbet’ (1582-1635) which is called The Distracted Puritan:

Am I mad, O noble Festus,

When zeal and godly knowledge

Have put me in hope to deal with the pope,

As well as the best in the college?

Boldly I preach, hate a cross, hate a surplice,

Mitres, copes, and rochets;

Come hear me pray nine times a day,

And fill your heads with crochets.

In the house of pure Emanuel

I had my education,

Where my friends surmise I dazel'd my eyes

With the sight of revelation.

Boldly I preach, &c.

They bound me like a bedlam,

They lash'd my four poor quarters;

Whilst this I endure, faith makes me sure

To be one of Foxes martyrs.

Boldly I preach, &c.

And so on. Both these ballads are clearly modelled on the original Tom-o’-Bedlam’s Song: evidence that it was well known enough to act as the template and reference for other versions. Basse’s ballad (if it’s his) is a poor imitation, while Bishop Corbet means merely to amuse his audience by likening a Puritan to a madman. There are so many other derivative versions that something must have set it all going! Let one final anonymous example stand for all. It can be found in Wit and Drollery; joviall poems: a collection compiled by one John Phillips between 1631-1706 and it too approximates the original scansion.

From forth the Elizian fields

A place of restlesse soules,

Mad Maudlin is come, to seek her naked Tom,

Hells fury she controules:

The damned laugh to see her,

Grim Pluto scolds and frets,

Caron is glad to see poor Maudlin mad,

And away his boat he gets:

Through the Earth, through the Sea, through unknown iles

Through the lofty skies

Have I sought with sobs and cryes

For my hungry mad Tom, and my naked sad Tom,

Yet I know not whether he lives or dies.

My plaints makes Satyrs civil,

The Nimphs forget their singing;

The Fairies have left their gambal and their theft

The plants and the trees their springing.

It goes on (and on, dragging in most of the Olympian pantheon) and concludes:

Stormy clouds and weather,

Shall call all souls together.

Against I find my Tomkin Ile provide a Pumkin,

And we will both be blithe together.

The voice in this rather lame attempt is that of Tom’s lover Mad Maudlin, but a much better version was chosen by Steeleye Span. It is Mad Maudlin, to find out Tom of Bedlam and was written by the playwright Thomas D’Urfey for his collection of songs and ballads Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy, published in various volumes between 1698 and 1720. D’Urfey, too, closely follows the rhythm and rhyme-scheme of the earlier ballad. I imagine that the song’s female perspective must have increased its appeal for Steeleye Span’s vocalist Maddy Prior, and I’m rather sorry they decided to rename it.

So at last I know why there’s no knight of ghosts and shadows, no burning spear and no horse of air in the Steeleye Span song. Mad Maudlin is not an imitation but a response to the older ballad. There’d been a fashion for poets to write responses to other poet’s songs. The best known is Walter Raleigh’s The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd (1600) which answers Kit Marlowe’s The Passionate Shepherd to His Love (1599). Marlowe’s poem received other replies too, right down to John Donne’s The Bait (1633). D’Urfey may even have been mocking the tradition with this exchange between two mad beggars; the point would have been entirely lost, however, if the original were not still well known.

D’Urfey’s ballad is vigorous and imaginative. It rivals some of the grotesqueries of the original – ‘To cut mince pies from children’s thighs/With which to feed the fairies’ is particularly striking. And it scans, which is more than some of the others quite manage. But the overall tone is rough and scurrilous: it doesn’t begin to attempt the lyric tenderness and heights of fantasy to which Tom-o’-Bedlam’s Song so effortlessly soars.

With a host of furious fancies

Whereof I am commander,

With a burning spear and a horse of air

To the wilderness I wander,

With a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney;

Ten leagues beyond the wide world’s end;

Methinks it is no journey.

For Rudyard Kipling these lines breathed ‘incommunicable splendour, opening doors into inexplicable worlds.’ Harold Bloom spoke of their astonishing power. Robert Graves did not commit to the ballad being ‘necessarily the work of Shakespeare’, but pointed to evidence suggesting it may have been sung during performances of King Lear in Shakespeare’s own lifetime. And for Isaac D’Israeli it was ‘delirious and fantastic; strokes of sublime imagination … mixed with familiar comic humour.’ He added, ‘The last stanza of this Bedlam song contains the seeds of exquisite romance; a stanza worth many an admired poem.’

I wholeheartedly agree. If ever a poem opened a magic casement on to the foam of perilous seas in faery lands forlorn, Tom-o’-Bedlam’s Song does it for me. And thankyou to Rosemary Sutcliff for introducing me to it, in a book which as the best children's books often do, has stayed with me for life.

*Coney-catching was a cant term used by the Elizabethan underworld. Petty thieves, card-sharps, pick-pockets and confidence tricksters were the ‘catchers’; their victims were the ‘coneys’ – which means rabbits.

*Not quite. In D’Israeli’s version, ‘heart’ may be a misprint for ‘host’, and ‘the rounded welkin’, though it makes sense, is more vividly ‘the wounded welkin’ in the earliest known version of Giles Earle.

Picture credits:

Beggar Looking Through his Hat, attributed to Jacques Bellange, Walters Art Museum Baltimore wiki

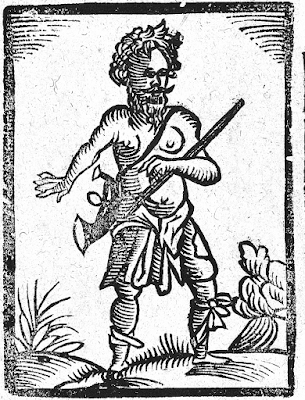

Bedlam Beggar: detail, woodcut, British Library

Abraham Man, Thomas Dekker, British Library

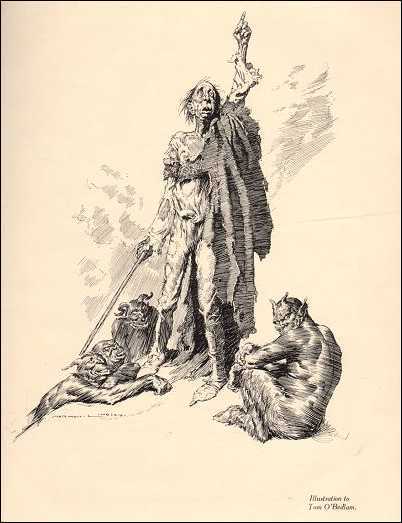

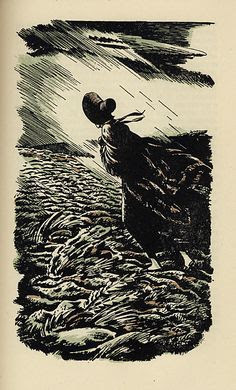

Tom o' Bedlam, by Norman Lindsay

Street Ballad: The New Tom o' Bedlam: British Library

November 18, 2021

Folklore Snippets: The Ship Beneath the Waves

From Le Folk-Lore de France, Paul Sebillot (1904), this tale is an odd twist on 'The Sleeping Beauty'.

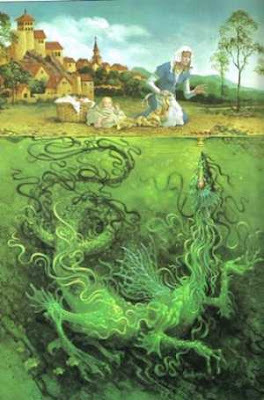

"Sailors seldom talk about ships or objects held by supernatural powers at the bottom of the sea. However, in the vicinity of Cap Fréhel (Côtes-du-Nord), it's said that an enchanted vessel lies intact under the waters of the Bay of La Fresnaye [in Brittany] and a number of accounts tell how it came to be down there.

A captain had kidnapped a young English girl and hidden her in his boat. Her fairy godmother tried to rescue her but was unable, for the captain was protected by the devil - and the devil is more powerful than the fairies. When she found that all her efforts were in vain, the fairy transformed the girl’s kidnapper into a dog, and attached him to the bottom of the ship with a huge chain. Then she put her goddaughter to sleep, dressed in beautiful clothes and precious jewels, and lowered the ship to the bottom of the sea. The devil, who witnessed all this and could not prevent it, promised the captain immortal life and swore that the girl would never belong to another. People say that if a priest would come down to the shore on a high tide, carrying the host, he could deliver the girl. Glimpses of the ship can be seen from time to time when the tide is very low; but the howling of the dog is often heard. It rages whenever a fishing boat strays over the vessel where it is chained; it believes the girl it guards is going to be taken from it, and it is ready to devour the unwary."

Tr: Katherine Langrish

Picture credit: 'Sleep of Time' by makkou4 on Deviant Art , spotted on Pinterest https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/295759900506789988/

October 28, 2021

DANSE MACABRE: a ghost story

“I’m bored,” Philip whined. “Can't we go now?”

“Hush!” said Mum.

He hadn’t been that loud. It was just that in this cold dim abbey every sound was magnified. A whisper rustled around the walls. A cough made you jump. Each shuffling footstep woke echoes that scurried off across the floor to bury themselves in nooks and crannies and little dark spaces. Philip longed to be outside, where the little lizards flickered over the hot stone steps in the sunshine.

His parents had stopped in front of another tomb: a sort of stone box with a marble bishop lying flat on top of it, scowling at the roof. His face was like a cake of dirty soap, half rubbed away by time. “Dad,” Philip pleaded. “Can we go?”

“We’ve hardly been here ten minutes yet,” said Dad. “Try to take an interest!”

“He’s only eight,” said Mum. “Phil, this is a famous place, a treat for Dad. He lectures about medieval things, remember? I could take him out, Mark, we can wait for you in the square.”

“But then I’ll feel I’ve got to rush. And you can’t miss seeing the Danse Macabre, it’s the reason we came. It’ll be exciting, Phil. Skeletons! You’ll like that, won’t you?”

“Real ones?”

“Of course not real ones, don’t be silly.” (Though why was it silly? There must be hundreds of skeletons in a place like this.) “It’s a painting,” Dad went on, “a marvellous painting. Come and see.”

He led them into a dismally lit side aisle. “Here it is!”

There were marks on the plaster, but Philip couldn’t see properly until Dad went to find one of the guides – a monk, a tall man in a grey robe. The monk had a torch. He switched it on and danced it over the wall. Philip gasped. Out sprang a horrible face – bald, bony, with hollow eyes and grinning teeth –

But it of course it was just a grubby old picture. The torchlight travelled down over a laddery chest, pinched waist and long spidery legs, then swung up to show that the creature had its arms round some person wearing a cloak and a crown.

“Un cadavre et l’Empereur,” said the monk. He glanced at Philip and dropped into English. “The Dance of Death, m’sieur, ’dame. Many such paintings were made after the Great Plague. Here you see Death meeting emperor, bishop, knight, peasant – all the estates.”

He swung the torch along the dirty plaster wall to pick out a procession of figures: people being waylaid by skeletons. Not clean Halloween ones. Their spindly limbs were clothed in withered muscle. They grinned with awful glee as they linked arms with the living to yank them away into the dance of shadows. And the living figures stood in frozen sadness at the surprise of death.

“Wonderful!” Mark paced along the wall, studying it. “Look at this group, Becky. So powerful.” He stopped near the end of the fresco, where one of the Deaths bent down coaxingly to a little child, hiding its pitiless face behind one crooked elbow, stretching out its other hand to touch.

“Oh…” Mum sounded breathless and odd. She stepped forward, blocking Philip’s view.

“Mark, it’s not very suitable –”

Dad wasn’t listening. “The fresco was never finished?” he asked the monk.

“That is correct, m’sieur. The drawings were made in charcoal, the background painted in. Then the artist went no further. The clothes, the faces, the figures were left as you see them – sketches, without colour.”

“Why?”

The monk shrugged. “No one knows.”

“Are there no records? When was it painted?”

“Quinzième siècle… perhaps 1470s. In the time of Abbot Renaud, it is thought. But nothing is known of the artist. He may have been a monk here…”

He droned on. And on. Losing interest, Philip saw something like a stone bed sticking out from the wall. What a funny thing! There was even a stone pillow at one end, and a strange hole, like the plug hole in a bath, at the other. Intrigued, he sat on the stone edge and poked a pencil down the hole to see how deep it was. The point went into something soft. Chewing gum? No; this felt mushy…

“Get up! You mustn’t sit there!” the monk shouted.

Philip jumped up. The pencil went flying. Mum and Dad glanced his way, shook their heads and went on talking. The pencil rolled into a gloomy corner and he scrambled after it. Horrible abbey! Horrible monk! He picked up the pencil and in revenge scrawled his own name on the wall.

His scream shocked the echoing spaces. All the murmuring and whispering and fidgeting went small and still. Mum and Dad came running to snatch and scold him.

“How could you, Philip? Scribbling on a wall, in a church, of all places – defacing a wonderful fresco – ” Dad drew a disbelieving breath. “What were you thinking?”

“I’d better take him out,” said Mum.

They waited in the strong, comforting sunshine for Dad to finish apologising. Philip hung his head while Mum ranted. “I don’t care how bored you were, there’s no excuse. And, goodness, what’s this on your trousers? It’s all black and sticky.” She whipped out a tissue and rubbed. “It’s some kind of tar, I believe – and it smells revolting. You’ve got it on your fingers, too. Where did it come from?”

“My pencil,” he whispered, pulling it out of his pocket.

“Throw it away!” She twitched it from his hand and sent it spinning down the steps, adding more gently, “But what made you scream?”

“A nasty man,” he whispered.

Unexpectedly, Mum was silent. “Those paintings,” she said at last. “I’m sorry, Phil. They were nasty, I agree.”

“Mum – ”

“Don’t think any more about them.” She gave him a brief hug. “We’ll do something fun this afternoon.” She turned as Dad emerged from the cold mouth of the abbey door. “Was he very angry, Mark?”

“It’s worked out well!” He was looking gleeful. “Phil’s silly scribble will clean off easily enough, and guess what? The monk who showed us the fresco is the librarian – Dom Raphael, he’s called. So I introduced myself, told him I’m a medievalist and asked if I could see the library – he says it’s full of old books and manuscripts. And he’s going to let me see them this afternoon! How about that?”

“Lovely,” Mum sighed.

That afternoon she and Philip went riding on rough little ponies through the resinous sunlit glades of the pinewoods. But the sunshine dazzled his eyes and his head ached. By suppertime he felt worse. Their guesthouse was in the village, a few crooked streets from the abbey. Madame Bertrand, the proprietress, was concerned. “He is pale, it is no good for children to look so. Can you not eat the tart, mon lapin? Non? Ah, quel dommage!”

“Bedtime,” said Mum rather grimly. She took Philip up to the room they all shared. There was a big four-poster bed for his parents, and a small couch against the wall for Philip. The ceiling sagged, the walls bulged as if the whole room might collapse with age. Up till now Philip had liked it. He hadn’t minded being left there while Mum and Dad had a last drink and an evening stroll. Tonight –

“Don’t go,” he begged, grabbing Mum’s hand.

“Now what’s wrong?” She stroked back his hair. “You’re not frightened, are you? Are you?” He nodded. “What of?”

“That man I saw in the abbey,” he muttered, picking at the covers.

“Oh Phil! It was only a picture, not a very nice one, but just a picture.”

“It wasn’t a picture. He spoke to me.”

“What?...In English?”

Philip looked confused. “No – I don’t know. But he did speak. He said, ‘I shall come and get you.’ And I didn’t like it. He hadn’t got any lips.”

She drew a sharp breath. “Phil. What an imagination you have! It was a nasty old wall painting, that’s all. Now lie down and go to sleep.”

Downstairs in the dining room, she said, “Mark, the fresco in the abbey has scared Philip stiff. It took ages to get him to sleep. He’s scared of a nasty man who’s going to come and get him.”

“Probably Dom Raphael! Phil’s upset, that’s all. He got in trouble for writing on the wall, and this is the reaction.”

“Well you can’t expect an eight year-old to enjoy trailing around old abbeys. I wish you pay him a bit more attention –”

They went to bed annoyed with each other. Philip was sound asleep, and Mark soon dropped off. Becky lay restless for a while, fretting and dozing, till she drifted into some kind of dream. She was lying back to back with Mark, but in the dream it was not him. It was someone else – someone long and stringy, who would presently turn and wind leathery arms around her…

She struggled out of sleep with a muffled shriek, and sat up. Nearby in the darkness, Philip was tossing and moaning. She was about to get up and go to him when she heard scratching on the outside of the bedroom door.

The cat…

She didn’t believe it was a cat. The door was old and loose-fitting. A clumsy bolt prevented it from drifting open in the middle of the night. The door rattled softly and the old-fashioned latch clicked as it lifted and dropped, but the bolt held. Then there was more scratching, like something picking at the edges of the door. It went on for a time, then stopped. A moment later, as if trying one last thing, there came a quiet, stealthy knock.

She sat frozen. The knock was not repeated.

It was much, much later before she could get to sleep.

Next morning at breakfast, pleasant Madame Bertrand was in a bad mood. Setting the croissants abruptly on the table, she launched into forthright French.

She was sorry to say it, but le petitPhilippe must have brought something in on his shoes yesterday. This morning she had found the passage covered in dirty marks, leading up the stone staircase to just outside their door. She had had to scrub the steps on her knees, and it was hard to remove, black and sticky, and of an ‘odeur pestilentiel’. She could not allow such a thing to occur again.

“I’m very sorry, Madame,” said Mark, “but it couldn’t be Philip; there were no dirty marks when we went to bed last night. Your shoes are clean, Phil, aren’t they? Show Madame!” Obediently, Philip stuck his feet out. He was pale, with black rings under his eyes. He said he had had bad dreams, that man had been trying to get into the room during the night.

“It was his footprints,” he said with a hysterical laugh. His parents looked at him uneasily, and Madame Bertrand suddenly patted him on the shoulder. “La, la, la,” she said. “It matters nothing. You are tired, mon pauvre. Boys should not be tired. Now, m’sieur” – she turned to Mark – “do not take him to the abbey. Let him run in the sunshine. It will be better.” She beckoned Philip. “Viens, mon petit. Come with me, I have a sucette for you,” and she led him away to the kitchen to give him sweets.

“And shall we?” Becky looked at Mark.

“Shall we do what?”

“Run about in the sunshine.”

“Ah…” He looked shifty. “I just wonder – would you mind very much if I went to the abbey again? There’s some fascinating old rolls of accounts which haven’t been touched for years. Dom Raphael says he needs more help. And I didn’t tell you last night, but we found an item relating to the fresco. A man called Jehan le Necre – ‘Black John’ – was given money ‘at the command of Abbot Renaud, to pay for a great brush of hogshair and two others of squirrel, for the Danse Macabre on the wall west of the choir.’ Of course we don’t know if he was the painter. But it’s likely, quite likely, and it would be such a coup if we could prove –”

“Yes, of course. I see.” She sighed. “I suppose so.”

“Becky, you’re a darling.” He took her hand. After a moment she withdrew it. “Mark, tell me something. Why did Dom Raphael shout at Phil yesterday for sitting on that little stone bed?”

“Ah – that.” He looked uncomfortable. “It’s not a bed, you see, though of course Phil would think it was. It’s a medieval funerary bench – a mortuary slab. They laid out all the dead monks there. That’s a drainage hole at the bottom end.”

“Ugh! Madame Bertrand is right. From now on, Phil and I are staying out of the abbey.”

She took him for a picnic. They climbed the hill above the village and she sat watching cloud shadows chase over the sloping fields while Philip played football with some English boys whose parents had stopped their car nearby.

“We’re staying at a campsite,” the boys boasted. “There’s a swimming pool, and table tennis, and barbecues every night. Is it just you and your mum? Where are you staying?”

“Down there.” Philip pointed. “In the town. My Dad’s working in the big abbey. See it?”

“In the abbey? Weird! Is he religious or something?”

“No. He just likes history.”

When the boys had left, he said, “I wish we could go camping.”

“Next year! If Dad agrees.”

The wind had whipped colour into Philip’s face and his eyes were brighter. But when she tucked him into bed that evening, he held her hand more tightly than ever, and looked at her pleadingly.

“Phil –” She didn’t know what to do. “We’re only downstairs. We’ll be coming to bed later, you won’t be alone. How I wish we’d never taken you into the abbey. Are you still scared of that painting?”

He shook his head. “I’m afraid of that man.” His lips trembled and his eyelashes were suddenly spiky and wet. He put his arms around her and buried his face. “Philip, dear…” She hugged him back. “You’re quite safe. Shall I stay till you go to sleep?”

He shook his head again. Just as she got to the door he said in a flat, tired voice, “It wouldn’t help. He won’t come until after you’ve gone.”

She went back, held his hand, looked him in the eye. “Philip. Listen to me. Nobody is going to come. Nothing bad will happen. I promise. I promise! Now lie down, and go to sleep.”

He was tired after all, and it didn’t take long. When she saw him breathing peacefully, she drew the covers up and switched off the light.

Downstairs, Mark was full of excitement. “We’ve found out more. The Abbot himself is interested now. It really was ‘Black John’ who made the Danse. But we don’t know much about him. He was probably from another monastery, on loan as it were, to do the work. Clearly a brilliant artist, but a bit of a troublemaker. Malicious. The other monks complained to the abbot that he quarrelled in the cloisters and ‘disturbs our peace.’ They may have got tired of him you see, and sent him away. That could be why the fresco was never finished.”

“I wish it had never been started! Phil’s still terrified. And I didn’t sleep well last night myself.”

“It is strong stuff,” Mark admitted. “Intended to be.” He hesitated. “I’m not surprised he’s nervous, it’s even affected me. While we were working on the Latin, Dom Raphael left the room to fetch something. But I felt I was not alone. I kept twisting about to see who was watching me. Just as he came back, I could swear I heard a voice say in a very strange accent, ‘Je vous mène à la danse.’ I asked Dom Raphael if he’d spoken, but he just looked at me and shook his head.”

“What did it mean?” Becky asked apprehensively.

“Well… ‘I will lead you in the dance,’ or ‘take you to the dance,’ I should think. It was my mind playing tricks: no one was there.”

“Mark…” Becky swallowed, and stopped.

“No! No, no, no!” Mark smacked his hand on the table. “And to show you all’s well, we’ll go for an evening walk. Yes, now! You mustn’t get into a silly, superstitious panic. We’ll just walk down towards the abbey and back. It’s a lovely evening.”

They set off arm in arm down the narrow street. Few people were about. The uneven roofs showed dark against a clear sky in which tremulous stars were opening. In the square, they looked up at the mighty bulk of the Abbey, reared high on its great flights of steps. A wonderful sound drifted from the glimmering windows: a sonorous humming that rose and sank, musical as a hive. The monks were chanting the evening prayers.

“Oh, you’re right, Mark,” said Becky softly. “No harm could come out of a place like this.”

They walked slowly, listening till it ended. “We’ve stayed too late. Philip might wake,” she said at last. As they turned to go back, something slipped from the dark Abbey doorway and scuttled down the steps. It was too dark to be sure –

“A very big dog?”

Becky shivered. “It moved like a spider.” They could not see where it had gone. “Hurry!” she said, grasping his hand.

The street was quiet. Ahead of them, someone else was out late. They could see his shoulders and head in silhouette, bobbing along about fifty metres ahead of them. He seemed very tall and thin, and, as he passed below a street lamp, wasp-waisted. “Isn’t there something odd about that chap,” began Mark. Becky did not reply. She tore her hand free from his and began to run.

With some dread knowledge stirring within him, he started after her. She was racing, hair flying, but he gained on her with long strides. Beyond, the figure she was pursuing passed below another lamp, and the head gleamed bald. It turned at the door of the guesthouse and vanished inside.

Mark crashed past his wife in the doorway and leaped upstairs three at a time. The treads were patched and soiled, the doorhandle sticky. He burst into the bedroom, hearing Becky sobbing as she clawed her way up behind him.

Philip lay asleep. Poised over him was a spindly figure, black and dripping as an oiled bird dragged from a slick. It reached out, hesitated. Hid its face in the crook of one arm. Jerkily, the other hand plucked at Philip.

The little boy woke. Screaming, he drew up his knees and thrust himself backwards. Heart thudding with revulsion, Mark snatched at the wiry black arm, feeling the skin break and ooze under his fingers, and flung the creature in one violent movement against the wall. Becky threw herself between, shielding her son. Phil was huddled against the headboard, his eyes like black pennies. “You promised he wouldn’t come!” he shrieked. “Mummy, you promised!”

Mark turned upon the thing, which had fallen and was crawling brokenly in the corner. “Go!” he stammered in unspeakable horror. “Go away!”

Feet hammered on the stone steps. Two men burst into the room in a swirl of grey robes. It was the Abbot and Dom Raphael, and after them puffed Madame Bertrand, shocked and open-mouthed. Towering over the thing on the floor, the Abbot lifted his right hand. With slow, emphatic ceremony he made the sign of the cross. “Jehan le Necre!” he commanded, and the creature writhed, “In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti, discede hinc in locum qui paratum est tibi. Vade, et reverte nunquam!”*

Madame Bertrand was wonderful. After a single glance at the mess on the floor, she swept them all into her private sitting room, where she made Philip drink a bowl of hot chocolate and plied the rest with tiny glasses of old cognac, strong and aromatic enough to exorcise any number of ghosts.

“How did you know to come?” Mark asked when, safe and warm at last, Philip had fallen asleep on Becky’s knees. “How did you know?”

“Dom Raphael feared you were in danger,” said the Abbot.

“But why?”

“He had found this piece of loose parchment. It may be in Abbot Renaud’s own hand, for this is what it says –

“ ‘The Danse Macabre will not be completed. For since the death of the painter, no one will undertake to begin where he left off. They say the Evil One came to claim him, and that he is as jealous in death as he was in life, and will not suffer another hand so much as to touch his work.’”

“And I thought” – stammered Dom Raphael – “I thought at once of your son, who in innocence had written his own name at the foot of the Danse Macabre. And I believed he was in danger. For here in the margin, see?” – he leaned over, pointing – “some other hand has written, ‘He died of the plague, but does not rest’.”

The Abbot said, “When Dom Raphael showed this to me, I doubted. But he said we should clean off the writing, and soon, for he had heard the whispering of the enemy, and it chilled his soul.

“I was still doubtful, though I have known Dom Raphael a long time. But after Vespers we went to look at the Danse together and he showed me with a torch where your son had written on the wall. So childish a thing, I almost laughed, but Dom Raphael did not laugh. No, he took my arm and led me along the wall past all the dancing Deaths, counting them as we went, and he said, and his voice shook, ‘Mon père, there have always been eight Deaths in the Danse, but here are only seven. There is one Death missing.’”

Dom Raphael said, “It was the one with the child.”

© Katherine Langrish 2021

* In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, be gone from this place to the place prepared for you. Go, and never return!”

Note: The Danse Macabre in this story is closely based upon that of the Abbey Church of St. Robert in the town of La Chaise Dieu, Auvergne, France. Needless to say, all events and personages in the story, including ‘Jehan le Necre’, are entirely fictional. The photographs of the Danse are from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Danse-macabre-chaise-dieu-panneau-1.jpg

October 21, 2021

True Ghost Stories

'The Ghosts' by Lord Dunsany, illustrated by Sidney Sime

'The Ghosts' by Lord Dunsany, illustrated by Sidney SimeThere is a great difference between a supposedly true ghost story and a fictional one. I used to live in a small Yorkshire village full of very old houses; the one my parents owned dated in part from the late seventeenth century. To the best of my knowledge we didn't have a ghost, but our neighbours in the even older whitewashed farmhouse down by the beck claimed to have a Red Lady who sometimes looked out of one of the small upstairs windows. And they were used to hearing footsteps cross the floor overhead when no one should be there. But that was it: there was no story attached.

Further down the road was a ford across the beck, accompanied by a medieval ‘clapper bridge’ of two huge stone slabs. This was (and still is) known as ‘Monks Bridge’ because in the days of the monasteries, Fountains Abbey had owned the land. The cottage beside the bridge was said to be haunted. Coming on foot up the narrow, unlit road one dark chilly night at about two o’clock in the morning, I was disconcerted to see someone lingering near the bridge, wearing a hooded garment which I took to be a cagoule. As I passed, the hooded person – whoever it was – slowly and very silently moved away from me, down towards the ford and the rushing water. I didn’t think ‘ghost’, I thought ‘oddball’ and hurried on. Later, I wondered.And on another occasion, close to the same spot on a pitch black night, I walked close past a person who was standing stock still in the centre of the road. I had no torch (which may have been just as well), and whoever it was did not move or speak, and it was the creepiest thing I have ever experienced.

The point about these stories is that there is no point. They have no real beginning, no middle, no end, no structure. In fact they aren’t stories at all, they are anecdotes. You hear them, you are impatient or fascinated according to your nature, and then you shrug, because there is no way to take them any further. People prefer explanations of course, so often there’s an attempt to provide some kind of Gothic rationale for the spectre, involving hidden treasure, wicked lords, seduced nuns, suicides and murders. These are rarely convincing. ‘Real’ ghost stories (and nearly everybody has one) are open-ended oddities, and quite frequently the person involved does not realise anything strange is happening until afterwards.

Few ‘true’ ghost stories are as good as the strange tale of Margaret Richard, reported in a book called ‘The Appearance of Evil: Apparitions of Spirits in Wales’ by Edmund Jones, an eighteenth century Welsh minister who compiled narratives of supernatural encounters in an attempt to prove the existence of both God and the Devil. Margaret’s sweetheart got her pregnant and then jilted her at the altar, sending word he was sick. Furious, Margaret fell on her knees and prayed he should have no rest in this world or the next. He may really have been sick though, for shortly afterwards he died and his ghost kept appearing to Margaret until finally she took his hand and forgave him. He vanished and never troubled her again, but here’s the creepy bit: ‘His hand did not feel like the hand of a man, but like moist moss.’

‘No one could have made that up!’ is the first reaction to this kind of thing. But of course, the ability to do just that is one of the prerequisites for writing a good fictional ghost story. If Edmund Jones had not been a minister, he had the imaginative and descriptive power to have become an excellent writer of such tales. Here he lies half-awake in a dank Monmouthshire bedroom, ‘partly underground and known to be an unfriendly place’, being assailed by Satan:

After I had slept some time and awaked, the enemy violently came upon me. I heard him say in my ear: ‘Here the devil comes in his strength.’ (And that was true.) He made a noise by my face, such as is made when a man opens his mouth wide and draws in his breath, as if he would swallow something. He also made a sound over me like that of dry leather and, by my left ear, a sound something like the squeaking of a pig. The clothes moved under me and my flesh trembled, and the terror was so great that I sweated under the great diabolical influence.

He must at least, if you will excuse the phrase, have been one hell of a preacher.

The least strained of traditional explanations for hauntings is that the troubled spirit cannot rest until some wrong it did or suffered in life has been put right. Here’s an account from Andrew Lang’s collection of true ghost tales, The Book of Dreams and Ghosts. Lang quotes verbatim from a seventeenth century pamphlet with the pleasing title: Pandaemonium, or the Devil’s Cloister Opened. Note the use of incidental details to lend verisimilitude:

About the month of November in the year 1682, in the parish of Spraiton, in the county of Devon, one Francis Fey (servant to Mr Philip Furze) being in a field near the dwelling place of his said master, there appeared to him the resemblance of an aged gentleman like his master’s father, with a pole or staff in his hand, resembling that he was wont to carry when living to kill the moles withal… The spectrum…bid him not to be afraid of him, but tell his master that several legacies which by his testament he had bequeathed were unpaid, naming ten shillings to one and ten shillings to another…

This restless spirit was considered to be of dubious origin, suspicions soon confirmed by events. The ghost was joined by that of his second wife, after which the neighbourhood was plagued with poltergeist activities which nowadays might point to the aptly named Francis Fey himself as the source of the problems:

Divers times the feet and legs of the young man have been so entangled about his neck that he has been loosed with great difficulty: sometimes they have been so twisted about the frames of chairs and stools that they have hardly been set at liberty.

Hmmm… However, Fey’s master and neighbours pitied him as the simple victim of the devil’s malevolence, and no further explanation seemed to be required.

Lang’s book touches upon all kinds of occult anecdotes, from premonitory dreams (“mental telegraphy”) to the full blown and richly detailed ghost story of the ‘Hauntings At Fródá’ from Eyrbyggja Saga. Too long to retell here, the tale follows the disastrous series of events following the death of a strange Hebridean woman, Thorgunna, at the farm of Fródá on Snaefellnes. The haunting begins when her hostess Thurid refuses to honour a promise she'd made at Thorgunna's deathbed to burn her guest's sumptuous bed-hangings (which Thurid herself had long coveted). It must be one of the best and most matter-of-fact accounts ever of ghost-as-reanimated-corpse – a phenomen which Iceland does particularly well – and it ends on another splendidly Icelandic note when the hosts of the dead are finally banished by a legal decision in a court of law. Though obviously ‘written up’ by the author of the saga, this tale retains much of the loose-ended mystery of the oral tradition. We never find out any more about Thorgunna, or quite why the violation of the taboo laid on her bed-hangings should have had such drastic consequences.

For me, the very best literary ghost stories are those which manage to combine both worlds – enough of a structure to provide a balanced, causal feel to the story, enough open-ended mystery to fascinate. A ghost story which is tied off too tightly is never entirely satisfying. They are very hard things to write, especially if you want to avoid Victorian pastiche. I recommend Alison Lurie's collection of short stories 'Women and Ghosts', Robert Westall's 'The Stones of Muncaster Cathedral' (Westall was very good at ghosts), Candy Gourlay's 'Shine' and Michelle Paver's brilliant, chilling novella 'Dark Matter'.

To end with, here’s a 'true' ghost story told to me many years ago by a friend...

We were living in France at the time, and my friend was an American woman married to a Frenchman. They lived in a modern house in Fontainebleau, but her husband had elderly aunts who owned a little chateau – one of those elegant small eighteenth century houses with shuttered windows and walled grounds that are scattered around the French countryside. This one was somewhere north of Paris, and the family would descend upon it for get-togethers at Christmas and Easter.

The bedrooms all had names, a charming custom – the Chambre Rouge, the Chambre Jaune, etc – but, said my friend, there was one bedroom everyone hoped they wouldn’t get, which latecomers would unavoidably be stuck with – the Chambre des Mouches: ‘The Bedroom of the Flies.’ It wasn’t just, my friend said, that there always seemed to be a number of flies in the room – big, sleepy, buzzy flies, crawling on the windows. One of the windows had been walled up, which was a little creepy. And there was a small powder room off the main chamber, which might once have used as a nursery. But mainly, you never got a good night’s sleep there. You lay awake listening to noises. As if something was shuffling about, or dragging something else across the floor. That was all. But she didn’t like it.

And so when a young woman called Meredith came visiting from the States – and a visit to the chateau was proposed – and she was given the Chambre des Mouches – no one in the family said anything. Because the house was full and no other bedroom was available, and really, the whole thing was probably nonsense… but there was a certain interest around the breakfast table next morning when Meredith came downstairs.

“How did you sleep?” they asked. Meredith hesitated. “Oh, I was comfortable enough – but I didn’t sleep too well because of that darned cuckoo clock. It went off every hour, bing bong, cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo, and kept waking me up.” “But, Meredith,” said my friend, as an indrawn breath went around the table – “there isn’t any cuckoo clock.”

September 30, 2021

Old Women (and some old men) in Fairy Tales

Probably every parent in a fairy tale should be considered old. They are the previous generation. We may hear something of their lives: how a queen is advised to eat a magical flower in order to bear a child, or how a king lost in the forest promises to marry his son or daughter to a witch or a bear – but only in order to set the scene for the adventures of their sons and daughters. Fairy tale parents cause problems for their children. They abandon them in the woods, or send them off to perform difficult tasks. They saddle them with obligations incurred before their birth, like Rapunzel's parents, or the king in a Hungarian tale who (in return for good fortune out hunting) promises to give an evil spirit ‘whatever you have not got in your house’ – which turns out to be his unborn daughter. Fathers threaten to marry their daughters, or demand proofs of extreme affection from them and then throw them out for not being sufficiently fulsome. Mothers usually die in the first paragraph and the husband remarries, leaving the child of the first marriage to the mercy of a stepmother. Stepmothers are nearly always bad, but are balanced on the male side by a whole parade of unreasonable, greedy, weak or incestuous fathers, and I do mean fathers, not stepfathers. The family, in fairy tales, is not a safe space. Just as in real life, it is often disfunctional, sometimes dangerous, and full of generational tension. It is a place to leave, as soon as possible.

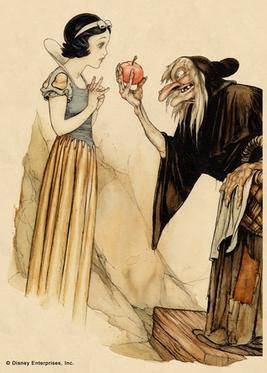

Look at the the murderous jealousy shown to Snow White by her stepmother the wicked queen, who resents seeing her beauty surpassed by that of a young girl. (Underlining the general uselessness of fathers, the King who is Snow White’s father gets a single mention and then apparently ceases to exist: we never hear of him again.) The cruelty of most fairy tale stepmothers is motivated by a preference for their own offspring over a step-child, but Snow White’s stepmother is unusual in being childless. Is her rage mere vanity? Or fear of mortality? Paradoxically, after learning from the magic mirror that Snow White still lives, she adopts the trappings of age.

…she thought and thought again how she might kill her, for so long as she was not the fairest in the whole land, envy let her have no rest. And when she had at last thought of something, she painted her face, and dressed herself like an old pedlar woman, and no one could have known her. In this disguise she went over the seven mountains to the seven dwarfs and knocked on the door and cried, ‘Pretty things to sell, very cheap, very cheap.’

In her attempt to remain young and fair, she makes herself old and ugly: everyone who’s seen the Disney cartoon will remember how through the second half of the film, she appears as an old hag with warts on her nose. Fairy tales are generally sceptical about attempts to reverse age, or cheat death. One person can perform such a miracle, and that is Our Lord who, stopping with St Peter one evening at a blacksmiths’ house in the Grimms’ tale ‘The Old Man Made Young Again’,takes pity on an aged beggar who asks for alms.

The Lord said kindly, ‘Smith, lend me your forge, and put on some coals for me, and then I will make this ailing old man young again.’ The smith was quite willing, and St Peter blew the bellows, and when the coal fire sparkled up large and high our Lord took the little old man, pushed him in the forge in the middle of the red-hot fire, so that he glowed like a rose bush, and praised God with a loud voice. After that the Lord went to the quenching tub, put the glowing little man into it, and after he had carefully cooled him, gave him his blessing, when behold the little man sprang nimbly out, looking … as if he were but twenty.

Unfortunately the smith has been studying this process, and next day after the Lord has gone on his way, he tries to replicate it with his mother-in-law, who gets horribly burned. (Yes, there are tasteless mother-in-law jokes in the Grimms’ fairy tales.)

‘Ugly old witch’ is a description which neatly combines misogyny and ageism. And there do seem to be many more old women in the Grimms’ tales than there are old men: by this I mean characters specifically described as old, rather than the parents we may assume belong to the older generation. I’ve counted twenty-seven old women including the twelfth Wise Woman in ‘Briar Rose’ but not her eleven sisters (who are narrative clones), and only five old men. The disparity is striking. It may be due to a perception of women as witches and magic-workers, or it may have something to do with 19th century rural society; possibly those women who escaped death in childbirth went on to outlive the men of their generation. But the split between good and bad old people is close to 50/50 for both sexes: twelve of the old women are helpful, fifteen are bad, while of the old men, two are good and three bad. Most of these old people are subsidiary characters with magical powers, briefly encountered either for good or ill. At the beginning of ‘The Six Swans’ for example, a King lost in the forest meets an old witch who guides him out on the promise that he will marry her daughter. He does so: the new Queen is also a witch, and we hear nothing more of her old mother.

But there are many helpful old women. The ones who keep house for bands of robbers nearly always take pity upon the hapless young man or woman who needs shelter for the night, and the same is true of ogres’ wives – and the Devil’s grandmother, a personage who appears in numerous fairy tales and is particularly active in teasing from her devilish grandson the answers to various puzzling questions the hero has been sent to ask.

An interesting Grimms’ tale ‘The Goosegirl at the Well’ plays with the presumption that any crooked old woman must be a witch. The countryfolk whisper, ‘Beware of the old woman. She has claws beneath her gloves’. When a kind young count offers to carry her load, it grows heavier and heavier as he toils up hill. He's unable to throw it off, and when the old woman springs on his back and hits his legs with stinging nettles to urge him on, we feel sure the countryfolk were right… but we’re wrong! The old woman turns out to be ‘no witch, as people thought, but a wise woman, who meant well.’ Having tested and proved the count's good nature, she jests that he may fall in love with her ugly daughter, but sends him off with a box carved from a single emerald, which contains a pearl wept by the king's daughter, banished for comparing her love for him to salt, The king has repented of his folly; the count promises to find the princess, and she turns out to be none other than the 'ugly' daughter of the wise woman, who has sheltered her all this time. The ugliness is only a disguise; she and the count marry, and all are reunited.

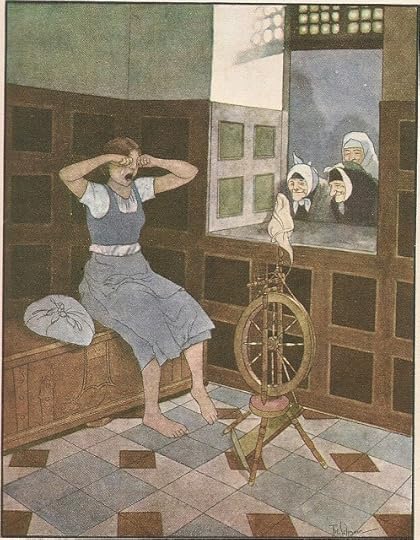

The magical old women of ‘The Three Spinners’ (pictured above) help a young woman to perform the impossible feat of spinning a room full of flax within three days. Unlike Rumpelstiltskin, they are benevolent; all they ask in return is to be invited to the girl’s wedding. And just as in the English version of this tale (‘Dame Habbitrot’), much is made of the ugliness of these three magical women:

When the feast began, the three women entered in strange apparel, and the bride said, ‘Welcome, dear aunts.’ ‘Ah,’ said the bridegroom, ‘how do you come by these odious friends?’ Thereupon he went to the one with the broad, flat foot and said, ‘How do you come by such a broad foot?’ ‘By treading,’ she answered, ‘by treading.’ Then the bridegroom went to the second and said, ‘How do you come by your drooping lip?’ ‘By licking, she answered, ‘by licking.’ Then he asked the third, ‘How do you come by your broad thumb?’ ‘By twisting the thread,’ she answered, ‘by twisting the thread.’ On this the King’s son was alarmed and said, ‘Neither now nor ever shall my beautiful bride touch a spinning wheel.’ And thus [the bride] got rid of the hateful flax-spinning.

Maybe to us this sounds like an invitation to laugh at such grotesque characters, but I’m not sure that’s how it works. The old women are helping a girl whose mother first beat her for laziness in spinning, then lied about it and landed her with this impossible task. They appear at the wedding with the deliberate intention of flaunting their deformities to save the girl from spending a lifetime spinning. Consider the likely audience for this story, and who might be telling it. It’s surely told for women by women, women who spent every spare moment spinning, who may even have been spinning while they listened. And it pays tribute to the sheer hard work, the endless, repetitive nature of domestic tasks, and the damage they do to the body. These powerful old women are ugly because they’ve worked and therefore deserve honour. I think the people listening to this story would have taken that in.

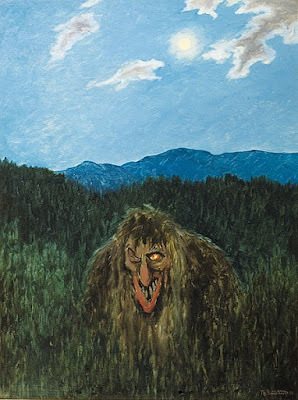

The most iconic crone of all is Baba Yaga, who is terrifyingly difficult to predict. She can be either helpful or very very dangerous, and it pays to address her with great courtesy. Her house stands on chicken legs and is ringed with a bone fence set with skulls whose eye sockets light up red as dusk falls. Of course she is ugly: she has iron teeth and bony legs, and flies through the woods in a mortar, steering with her pestle, but ugliness for Baba Yaga is no drawback, it's part of her mystique, her terror, her ambiguous power. She reminds me of the Hindu goddess and demon-slayer Kali who sometimes wears a garland of human heads. According to Dr Thomas Coburn's Devī-Māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition, “kālī is the feminine form of ‘time’ or ‘the fullness of time’ ... and by extension, time as the ‘changing aspect of nature that bring things to life or death’. Her other epithets include Kālarātri (the black night’) and Kālikā (‘the black one’).” In this context it's interesting to remember the Russian story of how as Vasilisa the Beautiful approaches Baba Yaga's hut, a white horse and rider gallop past her as dawn breaks, followed at noon by a red horse and rider, and a black rider on a black horse as dusk falls. Baba Yaga tells the girl that the white rider is Day, the red one is the Sun, and the black one, Night.

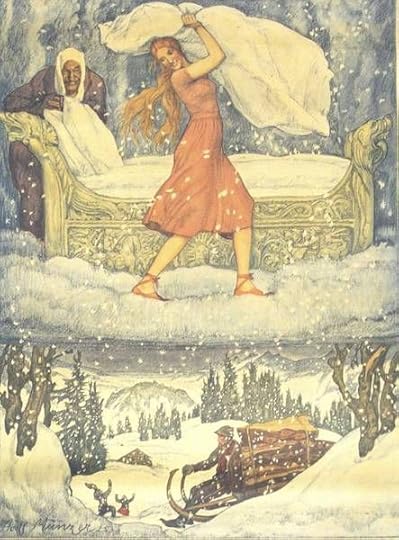

And talking of powerful goddesses, there’s Mother Holle in the tale of that name, who presides over a whole Otherworld at the bottom of a well. She has frighteningly ‘large teeth’ but calls reassuringly to the girl who has jumped down the well:

‘What are you afraid of, dear child? Stay with me; if you will do all the work in the house properly, you shall be the better for it. Only you must take care to make my bed well and to shake it thoroughly till the feathers fly – for then there is snow on the earth. I am Mother Holle.’

As the girl works hard and well, Mother Holle rewards her: a shower of gold will fall upon her whenever she crosses a threshold, while her lazy and rude stepsister ends up covered in a shower of pitch. Mother Holle is a folk memory of the Germanic goddess Holda or Hulde, whom Jacob Grimm describes as ‘a being of the sky’; like the Norse Freyja she ‘drives about in a waggon’ and ‘can ride on the winds, clothed in terror’. She is also a domestic goddess, visiting spinners and weavers and rewarding them for good work; she appears as either a beautiful white lady or ‘an ugly old woman’ (Grimm, Teutonic Mythology. Vol I, 265 et seq). I love the energy of this illustration in which the girl is having so much fun shaking out Mother Holle's feather bed. Work isn't always grind.

Whether they be wicked witches or wise women, fairy tales depict old women as repositories of knowledge and power. Like the witch in ‘Hansel and Gretel’ many live in cottages of their own, signifying their independence and autonomy. The notion that, in growing old, women lose beauty but gain wisdom is borne out by a peculiar little fairy tale in the Grimms’ collection, ‘Old Rink-Rank’. The story goes like this:

A king proclaims that his daughter’s suitors must cross a glass mountain without falling. When the princess’s sweetheart volunteers to try, she goes along to help him. Halfway over, she slips and the glass mountain opens and swallows her. Sweetheart and father mourn, unable to find her. Meanwhile inside the mountain the princess meets a greybearded man called Old Rinkrank, who threatens her with death unless she becomes his servant. She serves him for years until she too is old, when he names her Mother Mansrot. Then one day he goes out, and she shuts all the doors and windows except for one little window, and won’t let him in. He stands outside calling plaintively,

Here stand I, poor Rink-Rank

On my seventeen long shanks,

On my weary, worn-out foot,

Wash my dishes, Mother Mansrot.

The original of this strange rhyme is in the Frisian dialect and no one seems sure what it means, or even if this is a correct translation. Nor do we know what the names ‘Rink-Rank’ or ‘Mother Mansrot’ may imply; neither did the Grimms, who have nothing to say about any of it in their notes. Old Rink-Rank repeats the rhyme twice more, begging or ordering Mother Mansrot to make his bed, and to open the door, but she replies that she’s already done all these things for him. (I can’t help feeling she’s mentally adding, ‘And I’ve had enough!’) Then he runs around his ‘house’ to find a way in, and finds the little open window, but as he climbs through she shuts it, trapping his beard. Rinkrank screams and cries, but she refuses to release him until he tells her where to find a ladder. Tying a cord to the window, she ascends the ladder to the top of the mountain and pulls the cord to release Old Rinkrank. Then she marries her sweetheart, who is still alive, while the king has Old Rinkrank put to death and takes all his gold and silver.

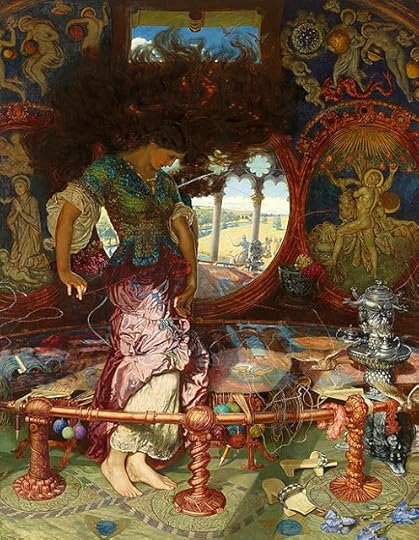

Time does curious things in this story. Maybe Old Rinkrank is an aspect of the difficult, possessive father. Fathers are always locking their daughters away in ‘princess in the mound’ tales, sometimes in anger and sometimes for their ‘safety’: either way, the princess generally gets no say. So perhaps the story’s about how she escapes from him, escapes the glass prison of her father’s control. In this, she out-performs the Lady of Shalott in Tennyson's poem – another young woman imprisoned in a tower to spin and weave, and forbidden even to look out of the window except indirectly through a mirror. (More of mirrors later.) Holman Hunt depicts the Lady as a self-consuming whirl of claustrophobic, imprisoned energy, ringed in brass, her hair floating in electrically-charged clouds – yet the only thing Tennyson can find for her to do in the outside world, once the mirror has cracked from side to side, is to lie down in a barge and drift to Camelot for Launcelot to admire her face in death. Given this kind of hopeless attitude to women's roles in the world, no wonder characters like Mother Mansrot were overlooked.

It’s when Old Rinkrank perceives the princess as old: no longer sexually attractive and therefore safe to leave – that Mother Mansrot gets her chance and reverses the power vector. Now he pleads and cries for her help while she punishes and deserts him. Men, after all, depended on women to look after them... But since her father and lover are still alive (‘The King rejoiced greatly and her betrothed was still there’) perhaps the ageing of the princess in the glass mountain is a metaphor more than anything else. She grows wise enough to trick Old Rinkrank and free herself. Wisdom is the gift of time and experience.

[This painting, 'If she would be his servant, she might live' is one of a wonderful series inspired by 'Old Rinkrank', by artist Emily C McPhie. See the rest at this link: emily c mc phie: an artist's journal.]