Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 9

April 28, 2021

Fairy Tales and Realism

When we were children my brother and I would sometimes bemoan our bad luck in never having any adventures. We were big fans of Enid Blyton, in whose books groups of children from nice safe middle-class backgrounds not very dissimilar to our own got into amazing adventures every single holiday. Every single Christmas, or Eastertime, or 'summer hols', something would happen to these children. The circus would arrive and the bad-tempered clown would turn out to be an international jewel thief. The tutor hired as a Latin coach would be either a spy or a detective. Those lights flashing out to sea beyond the ruined castle would be signals from an enemy submarine waiting to rendezvous with the tall stranger whose bad character had been clear from the moment he kicked Timmy the dog, and whose briefcase contained the stolen blueprints. The strange noises in the empty house could only come from smugglers’ barges gliding along the underground river gurgling beneath the trapdoor in the cellar.

Although these adventures were in one sense sheer fantasy, they were presented with a veneer of realism which could deceive our inexperience. I loved to read of dragons and flying horses, but I never expected to meet one. The dilapidated old barn a mile up in the fields near the edge of the woods, however – with the shotgun cartridges scattered around the doorway – surely that was something my brother and I ought to investigate? So we did, and were shouted at by the farmer for walking over his crops.

Well, we should have known better. Just because a book has a contemporary setting and contains nothing magical doesn't make it more realistic than a fairy tale: in fact some of them are fairy tales. Jacqueline Wilson’s nitty-gritty stories tussle with all sorts of issues: her young heroines and heroes live with unreliable parents, or in children’s homes, or have big stepbrothers who bully them, or are young carers themselves, or try shoplifting and smoking to impress their glamorous ‘bad’ best friend… isn’t this realism? Well, maybe not! I have great admiration for Wilson’s books, and my children loved them – but they are fairy tales. Like Cinderella, her characters go through all kinds of tribulations but always end up wiser, happier and in a better place than where they started. These are fairy tale endings – which I say with no shadow of disparagement.

Alison Lurie, in her book of essays on children’s literature ‘Don’t Tell the Grownups’ (Bloomsbury 1990), recounts how at the age of five she was given ‘The Here and Now Story Book’ written in 1921 by a writer named Lucy Sprague Mitchell whose credo was that fairy tales delayed ‘a child’s rationalising of the world’ and left him/her ‘longer than is desirable without the beginnings of scientific standards’. Lurie writes:

Inside, I could read about The Grocery Man (“This is John’s Mother. Good morning, Mr Grocery Man”) … The children and parents in these stories were exactly like the ones I knew, only more boring. They never did anything really wrong, and nothing dangerous or surprising ever happened to them – no more than it did to Dick and Jane, whom I and my friends were soon to meet in first grade.

To be fair to Sprague Mitchell, Lurie has picked the dullest story in the book (you can view them all here at project Gutenberg: some of them are charming), but learning to read in the early sixties, I too encountered such children in the ‘Janet and John’ readers, and in the safe, sunny, pedestrian world of the Ladybird books, where all families were made up of a Mummy who stayed at home and baked, a Daddy who went to work carrying a briefcase, a little boy in shorts, a little girl in a frilly dress, and a spaniel. Plots would revolve around picnics, kite-flying, the collection of tadpoles in jam-jars, and the making and icing of fairy-cakes. (The Ladybird collection included an excellent series of illustrated fairy tales, but it’s their 1960s ‘contemporary’ stories I’m talking about.)

Lurie continues with devastating truth:

After we grew up, of course, we found out how unrealistic these stories had been. The simple, pleasant adult society they had prepared us for did not exist. As we suspected, the fairy tales had been right all along – the world was full of hostile, stupid giants and perilous castles and people who abandoned their children in the nearest forest.

To succeed in this world you needed some special skill or patronage, plus remarkable luck, and it didn’t hurt to be very good-looking. The other qualities that counted were wit, boldness, stubborn persistence, and an eye for the main chance. Kindness to those in trouble was also advisable – you never knew who might be useful to you later on.

And this still seems to me the best argument against those who still think that fairytales are unreal, or at least more unreal than books set in the everyday here-and-now. How much do we need to be taught, in Lucy Sprague Mitchell’s phrase, to ‘rationalise the world’? Do we really need protection from the obviously fantastic? Richard Dawkins appeared to think so, as quoted in The Guardian on 5th June 2014:

“I actually think there might be a positive benefit in fairy tales for a child's critical thinking ... Do frogs turn into princes? No they don't. But an ordinary fiction story could well be true ... So a child can learn from fairy stories how to judge plausibility.’

He added: “Fairy tales might equip the child to reject supernaturalism when the time comes… Santa Claus again might be a very valuable lesson because the child will learn that there are some things you are told that are not true. Now isn’t that a valuable lesson?”

It’s not completely clear from this quotation exactly what he means (the ellipses indicate that parts of what he said have been left out), but it looks as if he’s saying that children can usefully learn to distinguishbetween unbelievable stories (tales and fantasies with supernatural elements) and believeable ones (‘ordinary fiction’). But my brother and I were never deceived by fairy tales or fantasies. We never went looking for dragons or unicorns. We could, however, very well imagine ourselves in an Enid Blyton-style adventure – and so doing, explored potentially dangerous deserted barns and houses – because her books contained no obvious impossibilities. Yet fiction is fiction is fiction.

Sir Philip Sidney in his famous ‘Apologie for Poetrie’ – a defence of invention written some time in the 1580s to counter those of his contemporaries who felt uneasily that anything non-factual was somehow deceptive – wrote:

I think truly, that of all writers under the sun the poet is the least liar… for the poet, he nothing affirms, and therefore never lieth. For the poet never maketh any circles about your imagination, to conjure you to believe for true what he writes.

‘No circles about your imagination’: if you know that what you are reading is pure invention without any pretensions to be history or fact, you can stop worrying about belief. The poet ‘nothing affirms’ – makes no claims. You are left free to apprehend the truth of the poetic imagination. Sidney recognised that the perceived gulf between fiction and non-fiction is more mirage than fact: he goes on to point out that – surely – only a fool would describe Aesop's fables as lies, or mistake a play for a real happening...

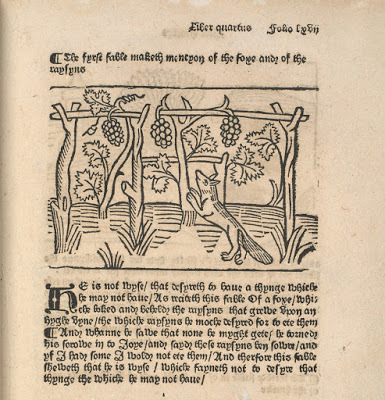

None so simple would say that Aesop lied in his tales of the beasts; for whoso thinks that Aesop writ it for actually true were well worthy to have his name catalogued among the beasts he writeth of. What child is there that, coming to a play, and seeing Thebes written in great letters upon an old door, doth believe that it is Thebes?

Aesop's fictions are not really about animals. Instead, they present succinct points about human morals and behaviour. To miss that would indeed be to miss the entire point – and Sidney shows more faith in the average child’s ability to suspend disbelief than Dawkins does. Where Dawkins suggests that ‘an ordinary fiction story could well be true’, Sidney says boldly that while every kind of fiction is of its nature untrue, it is the story masquerading as realism which is the most likely to deceive. A history book may be plausible and convincing while containing many errors and biases.

I would unhesitatingly put my money on the basic stuff of fairy tales being far more likely to happen to the average child than the chance of capturing an enemy spy or discovering a nest of coiners. Your parents may abandon you, or die, or abuse you. You may be ignored and disregarded. Later in life your lover may forget you; you may have to work hard for little or no reward or recognition.

Though at first sight fairy tales may appear simple or childish with their pre-industrial characters and settings, they offer a rich harvest of metaphors for life, as well as delighting in the beautiful world and applauding courage, kindness, innocence, wit and endurance. Stories are real and not-real at the same time. We need to allow ourselves and our children to discover the power of the imagination to transform experience. Fairy tales we have read as children may stay with us forever. Some are frightening, of course, for fairyland is a dangerous place: but so is this world, and we do children no favours by pretending otherwise. Fairy tales do not attempt to deceive and pull no punches. They tell us life often looks quite overwhelming, but they offer hope too. You may have to journey to the back of the north wind, ride over seven miles of steel thistles, weave shirts from nettles, suffer insults in silence, scale glass mountains – but ‘pack courage, leave fear at home’ and you will find a way.

Picture credits:

The Goosegirl: Arthur Rackham

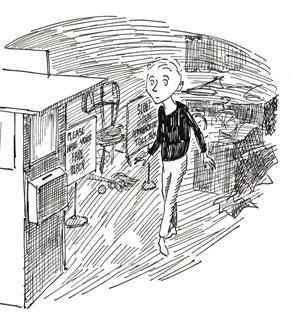

Illustration by Gilbert Dunlop to The Rockingdown Mystery by Enid Blyton:

Aesop's Fables, printed by Caxton: British Library

The Knight gallops up the Glass Mountain: Theodore Kittelsen

April 14, 2021

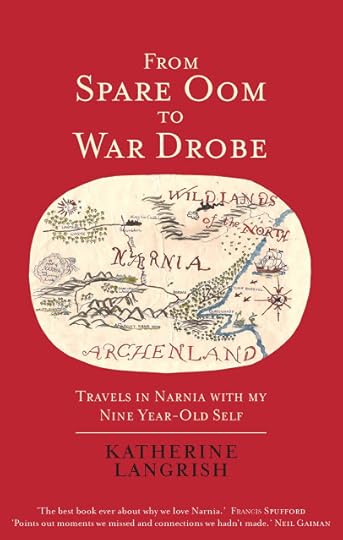

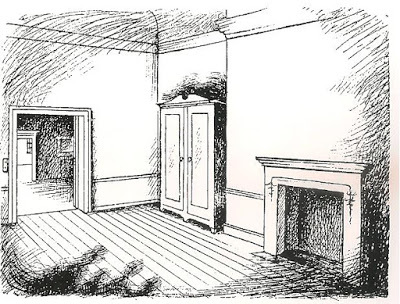

'From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with my nine year-old self'

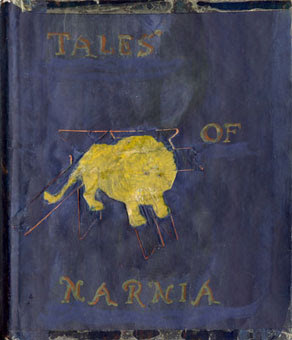

At the end of this month my book about Narnia will be published – 'From Spare Oom to War Drobe', Darton Longman and Todd, 29th April 2021, £16.99: https://bit.ly/3wHaOYw – and available from all good book retailers. The map on the cover is one I copied as a child from Pauline Baynes' map of Narnia in Prince Caspian. I apologise for blowing my own trumpet! But this book had its genesis both here on my blog and more importantly, in the absolute and utter love I had for the Seven Chronicles when I was a child. I read and re-read them until the covers were dog-eared and creased and coming to pieces. I almost – almost! – believed Narnia to be real, and I desperately wanted to read more stories about that magical land.

Do you remember this passage from The Last Battle? It comes near the end, when Tirian, Jill and Eustace, with Puzzle the donkey and Jewel the Unicorn, are walking through the springtime woods hoping (it is a forlorn hope) to meet Roonwit the Centaur leading reinforcements from Cair Paravel to defeat the forces of evil. While they walk, Jewel begins telling Jill about the long and mostly peaceful history of Narnia:

He spoke of Swanwhite the Queen who had lived before the days of the White Witch and the Great Winter, who was so beautiful that when she looked into any forest pool the reflection of her face shone out of the water like a star by night for a year and a day afterwards.

Isn’t that lovely? Elvish enough for Tinúviel.

He spoke of Moonwood the Hare who had such ears that he could sit under Cauldron Pool under the thunder of the great waterfall and hear what men spoke in whispers at Cair Paravel. He told how King Gale, who was ninth in descent from Frank the first of all Kings, had sailed far away into the Eastern seas and delivered the Lone Islands from a dragon, and how, in return, they had given him the Lone Islands to be part of the royal lands of Narnia for ever. … And as he went on, the picture of all those happy years, all the thousands of them, piled up in Jill’s mind till it was rather like looking down from a high hill on to a rich, lovely plain full of woods and waters and cornfields…

I wanted very badly to know these stories in full. So I tried to write some of them myself, and this was the result: my very own 'Tales of Narnia'!

I was wise enough not to attempt a story about Swanwhite, whose whiteness by the way – the warm whiteness of a swan’s feathers – is wonderfully different from the stark whiteness of the witch Jadis whose skin is variously described as white as salt (strong and bitter), white as paper (blank) or white as icing sugar (chokingly sweet).

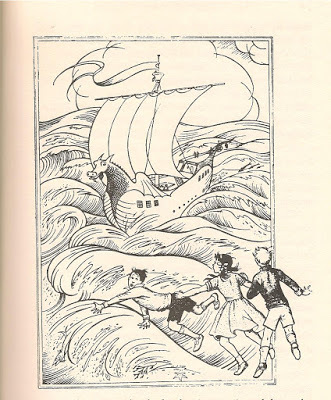

No, I plumped for King Gale and his dragon. In my story a Talking Stag brings King Gale and his Best Flying Horse Friend, Diamond, terrible news of a dragon attack on the Lone Islands. Leaping into action, Gale and Diamond fly to Cair Paravel where a ship is waiting, and are soon at sea with exciting adventures along the way – like this one:

Suddenly, from the fighting top, the lookout shouted, “Land Ho!” “That’ll be Galma and Terebinthia, won’t it?” the King remarked to Drinian. “Yes Sire,” said Drinian. “And I think –” the King never knew what Drinian thought, because just at that minute, he was interrupted by the lookout yelling “Pirate ship on the starboard side, bearing up on us fast.” “Hm. Terebinthian by her rig,” muttered the King. He was roused by Drinian shouting orders. “All hands on deck, man the guns, look lively!” At once all the crew came rushing to man and prime the guns… Meanwhile, the pirate was bearing down on them fast. Drinian waited till it was within range, then “Fire!!!” rang out across the ship. When the smoke cleared they could see that she (the pirate) was holed and slowly sinking. “Shall I fire again, Sire?” asked Drinian. “Aslan’s Mane! No! Aslan forbid that I should ever fire upon a sinking ship!” cried the King. “Your Majesty is the mirror of honour,” replied Drinian gravely. … Slowly she sank, until only a whirling, troubled patch of water showed where she had been.

I’m amused by the stiff Narnian dialogue, also that I felt it necessary to explain in brackets that ‘she’ was the ship; and I bet you never knew that Narnian ships carried cannons, let alone such effective ones. And it now seems to me rather a pity that in spite of his vaunted chivalry, Gale makes no attempt to rescue any of the drowning pirates. But in my view back then, baddies were baddies and deserved what they got.

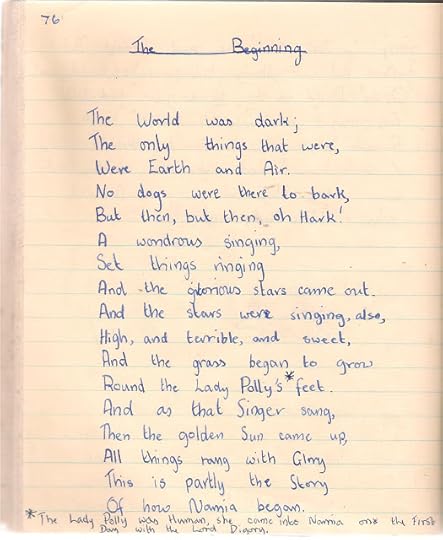

I loved writing these stories, and they taught me at least two important things. First, I found out that I couldn’t write as well as C. S. Lewis. 😕 Second, I found that writing’s a very different pleasure from reading: you don't experience the story, live in it, in quite the same way. I didn't want to stop, though. I went on to write stories about the Seven Brothers of Shuddering Wood and the Lapsed Bear of Stormness and other marginal Narnian characters. My poem about The Beginning of Narnia (no less!) with its awkward rhymes and solemn footnote will probably make you both wince and smile; it does me, but oh, it was heartfelt!

None of these tales of mine really succeeded in satisfying my longing for Narnia. Yet in the process of writing ‘Spare Oom’ over a year ago, I did feel I had at last got back there – in revisiting, reliving my childhood passion for the stories, and exploring with delight the many vivid threads Lewis has woven into the tapestry of his world with references not only to Christianity and the Bible, but to medieval and Renaissance poetry, fairy tales, Shakespeare, Plato and Socratic logic, Lewis Carroll, George MacDonald, Edith Nesbit… he poured into them everything that he loved. Like Lewis himself, the books have their faults, but they still offer a great richness of experience to any child who reads them. I count myself lucky to have been one.

In a free online event on Friday 7th May I will be discussing the book and the world of Narnia with the novelist and critic Amanda Craig.

Register to attend at this link: bit.ly/SpareOomLaunch !

April 8, 2021

Banquets, Stews and Picnics: Food in Fantasy

Diana Wynne Jones, in The Tough Guide to Fantasyland, warns travellers that the only thing they’ll ever be offered to eat on their Quest – whether in Tavern, Alehouse or Camp – will be Stew. Unless of course they are entertained by an Enchantress who intends to seduce them, in which case jellies soother than the creamy curd, and lucent syrops, tinct with cinnamon will be the least of it.

Stew… she has a point, of course. Given all the stuff we have to provide for our characters so that they can make it over the mountains, through the forest, and across the desert – backpacks, ponies, waterflasks, sacks of oatmeal – most authors draw the line at dreaming up menus. Much easier to picture a cooking pot slung over the flames with something indeterminate bubbling away inside – and throw in a couple of references to rabbits spitted over the flames. What else after all can you cook in a pot over an open fire, except stew? Or possibly porridge?

And whenever I watch the movie of The Fellowship of the Ring (that’s at least once a year), I wonder again about the fry-up of sausage, eggs and ‘nice crispy bacon’ the hobbits cook on the slopes of Weathertop. Days out from Bree, wouldn’t the eggs have smashed and the sausages gone off? Or been eaten already: how many eggs and sausages did they set out with? And that scene where Aragorn returns to camp with a dead deer slung over his shoulders: they’ll be moving on next day, so how much raw meat are they prepared to cart around with them? That's down to Peter Jackson rather than Tolkien of course, but no wonder the elves invented lembas. Portable, nutritious and clearly vegetarian, it is the culinary equivalent of the useful phosphorescent stuff that appears on the end of wizards' wands (or simply clings to the walls) to illuminate otherwise lightless caves.

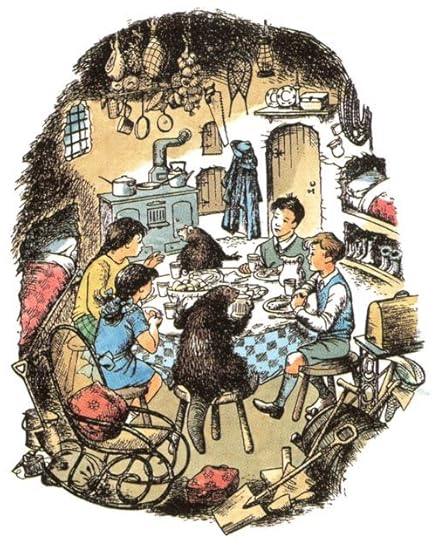

But there is a lot more to food in Fantasyland than Wynne Jones' witty account allows. I must hold my hand up; I have occasionally given my characters stew (andmysterious glowing lights), but in my own Dark Angels, set in the late 12th century, I had fun referencing real medieval dishes such as blancmange – that’s ‘white food’: minced chicken with pounded almonds – for the meals at the high table of Lord Hugo's motte-and-bailey castle, La Motte Rouge. One character in the book is a very food-centric house-hob:

The hob yawned, showing a lot of yellow teeth. “What's for supper tonight? Roast pork and crackling?”

“It's Friday,” said Nest, wiping her eyes.

“Is it?” The hob's face fell. “No meat,” it grumbled. “Fasting on Friday. Who thought that one up? What's the point?”

Nest sat up. “Fasting brings us closer to the angels,” she said coldly. “Angels never eat. They spend all their time praising God.”

“Only cos they ain't got stummicks,” the hob muttered. “Go on then, what's for supper? Herbert's not the worst cook I've ever known. We won't starve. Fish, I s'pose? A nice bit of carp, or trout?”

And the meal turns out to consist of fish in batter with a sharp sauce, followed by a sweet omelette.

Many fantasies are not affected – may even be enhanced – by the appearance of anachronistic or otherwise out-of-place types of food. In that affectionately ‘English’ area of Middle-Earth, the Shire, no reader will mind references to potatoes, fish and chips, buttered toast, birthday cake, etcetera. Early on in The Hobbit, Gandalf and the dwarves demand all kinds of food from poor Bilbo, all of it either very English or, like coffee, at least easily available in England. “Tea?” exclaims Gandalf, rejecting it –

“No thankyou! A little red wine, I think for me.”

“And for me,” said Thorin.

“And raspberry jam and apple tart,” said Bifur.

“And mince pies and cheese,” said Bofur.

“And pork-pie and salad,” said Bombur.

“And more cakes – and ale – and coffee, if you don't mind,” called the other dwarves through the door.

... “Put on a few eggs, there's a good fellow,” Gandalf called... “And just bring out the cold chicken and pickles!”

Much of The Hobbit is lighter in tone and more frivolous than The Lord of the Rings (and I disliked the book as a child, I felt talked-down to) – so this stodgy English fare works well as comedy. But it’s impossible to imagine coffee or tea being offered to guests anywhere else in Middle-Earth – in Rivendell, Edoras or Minas Tirith. Even Sam’s throwaway remark about fish and chips to Gollum in Ithilien (in the chapter ‘Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit’) makes me a little uneasy: Middle-Earth is so clearly European in its culture/s that I feel there shouldn't be any potatoes. I can cope with pipe-weed because Tolkien has (thinly) disguised it. It might not be nicotiana: people smoke all kinds of things. But potatoes?

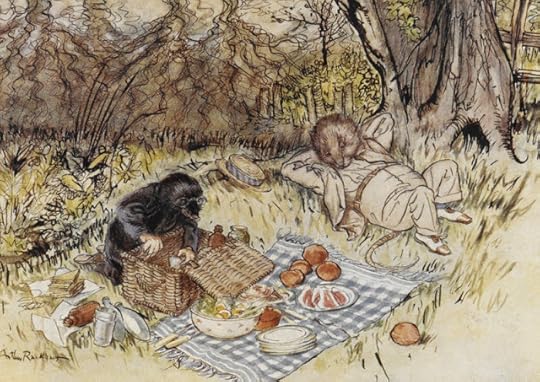

I was more comfortable with the frivolous tone in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows. Here for example, the Water Rat (a charming Oxbridge type) packs this magnificent picnic into a 'fat wicker luncheon basket':

“What's inside it?” asked the Mole, wriggling with curiosity.

“There's cold chicken inside it," replied the Rat briefly, “coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscresssandwichespottedmeatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater –”

“Oh stop, stop,” cried the Mole in ecstasies: “This is too much!”

“Do you really think so?” inquired the Rat seriously. “It's only what I always take on these little excursions, and the other animals are always telling me that I'm a mean beast, and cut it very fine.”

Kenneth Grahame's animals are so anthropomorphised that even their size is indeterminate – the Toad drives a car and can pass himself off in human society as a washerwoman – so it feels all right for them to eat human food. Even bubble and squeak, that peculiarly British concoction of fried potato and cabbage, makes its appearance in The Wind In The Willows, and the jailer’s daughter, pitying the poor imprisoned Toad, brings him:

…a tray, with a cup of hot tea steaming on it; and a plate piled up with very hot buttered toast, cut thick, very brown on both sides, with the butter running through the holes in it in great golden drops, like honey from the honeycomb. The smell of that buttered toast simply talked to Toad…

As well it might. Mmmmmm... And thinking of comfort food, I read John Masefield’s classic The Box of Delights to my daughters when they were small. There’s a point when young Kay despairs of ever managing to explain to the warm-hearted but slow Police Inspector that the villainous wizard Abner Brown is masquerading as the principal of a nearby religious college. The good Inspector advises him:

“You get that good guardian of yours to see you take a strong posset every night. But you young folks in this generation, you don’t know what a posset is. Well, a posset,” said the Inspector, “is a jorum of hot milk; and in that hot milk, Master Kay, you put a hegg, and you put a spoonful of treacle, and you put a grating of nutmeg, and you stir ‘em well up and then you take ‘em down hot. And a posset like that, taken overnight, will make a new man of you, Master Kay, while now you’re all worn down with learning.”

Both daughters insisted that I make it. I did, and it’s delicious, and they had it often over the years of their ‘school learning’… Try it! For treacle I’ve always used Tate and Lyle’s Golden Syrup, in the traditional green and gold tin – not molasses. A little later in the book, Kay is entertained by the Lady of the Longwise Cross in her home in the oak tree, where:

…the squirrel, the moles, the most beautiful little mice and seven little foxes brought Kay strawberries, raspberries, red and white currants, ripe mulberries, plump blackberries, red and yellow cherries, black cherries, walnuts, beechnuts, hazel-nuts, filberts, little round radishes, little pointed wild strawberries, sloes all cracking with ripeness, a mushroom for a relish, a chip cut from a turnip, an apricot from the south wall, and a peach almost bursting its skin.

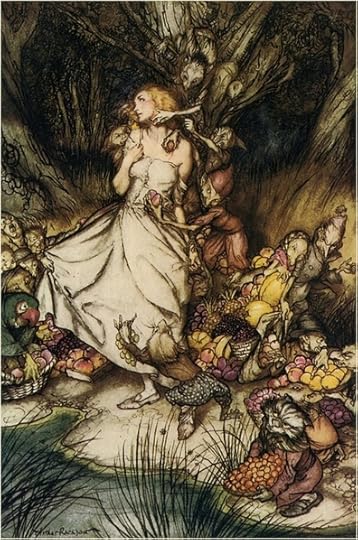

This rivals the tempting but far less wholesome fruit of Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market:

Plump unpeck’d cherries,

Melons and raspberries,

Bloom-down-cheek’d peaches,

Swart-headed mulberries,

Crab-apples, dewberries,

Wild free-born cranberries,

Pine-apples, blackberries,

Apricots, strawberries,–

All ripe together

In summer weather,–

Morns that pass by,

Fair eves that fly;

Come buy, come buy…

In The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, the Beavers eat impossibly English food. They do fry fish, which Mr Beaver has caught. But how do they manage ‘a jug of creamy milk for all the children (Mr Beaver stuck to beer) and a great big lump of deep yellow butter in the middle of the table, from which everyone took as much as he wanted to go with his potatoes’? Where are the cows? And the meal ends with ‘a great and gloriously sticky marmalade roll, steaming hot,’ and cups of tea. But it doesn't matter, any more than the appearance of Father Christmas matters, for this book is like The Wind in The Willows: to demand consistency is to miss the point.

In Prince Caspian, things have gone badly wrong in Narnia: under King Miraz the land is in a worse state than under the White Witch: so the children meet few comforts and have to eat what they can find. They start with apples, plucked from the wild orchard that has sprung up around the ruins of abandoned Cair Paravel; later they add bear steaks from a bear (not a Talking Bear) which they have shot. “Each apple was wrapped up in bear’s meat … and spiked on a sharp stick and then roasted. And the juice of the apple worked all through the meat, like apple sauce with roast pork…” This opportunistic feast is in some ways more convincing than stew, for which in any case the children have no cooking pot, but I think Lewis is way too optimistic about the success of the recipe. I’m sure it would have been both tough and very messy. But he manages to make the soil which the trees eat at the banquet at the end of the book sound delicious.

They began with a rich brown loam that looked almost exactly like chocolate…When the rich loam had taken the edge off their hunger, the trees turned to earth of the kind you see in Somerset, which is almost pink. They said it was lighter and sweeter.At the cheese stage they had a chalky soil and then went on to delicate confections of the finest gravels powdered with choice silver sand.

I was with him through most of it, but he lost me at the gravels.

Patricia McKillip, whose beautiful fantasies sustained me through much of the first lockdown, writes wonderfully about food. In The Book of Atrix Wolfe, a lost, mute child, Saro – daughter of the Queen of the Wood and the dangerous Hunter – is taken in and set to work as a scullery maid in the kitchens of the castle Pelucir. McKillip brings the busy kitchens and the people who work there to vivid life.

It was late; the King’s hunt had returned long before; supper and its confusion of plates and pots and tales carried down the stairs, coming in the back door, was long over. … The King had retired in fury and despair to his chamber, slamming the door so hard, the boom down the long corridor sounded, servants said, like one of the prince’s explosions. Supper – roast, peppered venison, tiny potatoes roasted crisp, hollowed and filled with cheese and onions and chive, cherries marinated in brandy and folded into beaten cream – sailed over the tray-bearer’s head and splashed in lively patchwork on the wall behind him. Brandy was taken up, and later, another tray which at least made it through the door. Dirty pots came to an end, fires were banked…

By dawn of the next day it’s all to do again:

… the spit-boys, groping, half asleep, sat up to toss wood on the fires beneath the bread ovens. The head-cook entered later to the smell of hot bread, followed by hall servants and yawning undercooks, and the tray mistress, red-eyed and grim.

“Hunt,” the head-cook said tersely. The dogs were barking in the yard. “Again. Take up bread and cheese, smoked fish and cold, sliced venison. Mince the rest of the venison for pie. Also onions, mushrooms, leeks. Take up spiced wine.”

“Again.” I love the implied groan, and I love the attention McKillip pays to the actual work, the craft of cookery and running a kitchen. Though the King and his nobles are engaged in high matters – the terrifying Hunter may return – McKillip shows their interdependence with the servants, who make all kinds of decisions for them. No way does the head-cook intend to to waste all that perfectly good uneaten venison; the King and his party are going to be made to eat it one way or another! Next day’s breakfast for these pampered (yet worthy) nobles consists of “silver urns of chocolate, trays of butter-pastries, hams glazed with honey and cut thin as paper, eggs poached in sherry, birds carved out of melons and filled with fruit…” Lyrical as these descriptions are, they are functional as well: for with so much carrying of trays and setting of tables, and waiting upon them, the servants know and discuss all that’s going on: they are invested in the events of the story, for the return of the Hunter would be disastrous for them too. And all the time, mute little Saro is listening.

Patricia McKillip’s is the cordon bleu of fantasy food: I doubt it has ever been equalled. So... what fantasy banquet would you most like to be invited to?

Picture credits:

Histoire d'Olivier de Castille et d'Artus d'Algarbe: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8449031h/f368.image

Cooking pot: wikimedia commons

Rat and Mole's Picnic from The Wind in the Willows: Arthur Rackham

Animals bringing berries, from The Box of Delights: Judith Masefield

Illustration to Goblin Market; Arthur Rackham

The Beavers' home, from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: Pauline Baynes

Illustration of feast, from Prince Caspian: Pauline Baynes

April 2, 2021

Personal names in historical fiction

'Fair Rosamund' by John William Waterhouse

'Fair Rosamund' by John William WaterhouseHere, in the imagination of John Waterhouse, is Fair Rosamund leaning out of a rose-bedecked tower window, longing for her lover King Henry II while her cruel rival and soon-to-be-murderer Queen Eleanor peers at her from behind the arras. Most of this is pure fiction. The reason I'm showing her here is that back in the 12th century 'Rosamund' was an extremely unusual given name. It was possibly unique to this particular woman, and was rare throughout the entire medieval period, probably because rosa munda (pure rose) and rosa mundi (rose of the world) were epithets reserved for the Virgin Mary.

One of my pet bug-bears about novels set in ‘medieval times' is when authors call their characters by names which are unhistorical for the century in which the story is set. After all, 'medieval' covers about half of a millenium during which a great many changes occurred in laws, society, languages and fashions. Fantasies (I'm sorry to say) are some of the worst offenders, perhaps because a vague medieval ambiance is sometimes all the author really wants. This is not a problem if the story is set in some fantasy- or fairy- land where dragons dwell, where wicked knights in black plate-armour inhabit grim stone castles at one end of the village, fair damsels live in rose-smothered cottages at the other, honest peasants toil in the fields somewhere in the middle, and the whole is surrounded by darksome woods. But – but! – if you tell me the wicked knights are Normans and the peasants and the heroine are Saxons, and if you set the story ‘just after the Norman Conquest’, then I feel you, the author, ought to do your best to present a reasonably accurate picture of the time.

The period of active Saxon rebellion against the Norman invaders lasted till about 1070: after that, any widespread popular resentment, if indeed it existed, was probably short-lived. True, the Normans displaced or eliminated most of the Saxon nobility, but for the peasants, free or unfree, life did not change very much. So in a novel set during the century after 1066, the wicked knight will be wearing chain-mail, not plate armour. Unless he is very important indeed he will live not in a stone castle but in a wooden fort on a mound surrounded by a stockade (as the Montgomery lords did at Hen Gomen, not building their stone castle until 1223). And though the peasants will certainly still be toiling in the fields, the fair damsel’s cottage will have no red roses around the door, since cultivated roses would have been a hugely expensive rarity. Moreover, if she’s a Saxon she ought to be called something like Aelfthryth or Eadburh or Edith – not Mary or Alison, names which won't appear for about another two hundred years. If your heroine is a Norman lady you may name her Rose so long as you spell it Roheis, Rothais or Roesia, but be aware that after the 12th century the name goes out of use for about seven hundred years. (Who knows why?)

Here for the benefit of us all is a masterclass from Lord Raglan (1885-1964) in nomenclature for the early medieval period. “Let us start with the Saxons,” he begins:

... and note without surprise that they were called by Saxon names. Examples of such names may be found in any history – Godwin, Stigand, Siward, Leofric. The Saxons were not called William, Walter or Robert, because these were Norman-French names which were introduced into England by the Normans. A pre-Conquest Saxon would be no more likely to be called by a Norman-French name than a modern Englishman to be called Marcel or Gaston.

So much for the Christian names of the Saxons; now to surnames. The Saxons had no surnames. A 'Godric' might be referred to as ‘the timberer’ or ‘the son of Guthlac’, but these were not his names; whether he was earl or churl he had one name, and one name only. This single name was never a place name. Like the Scandinavians, Irish and Welsh, the Saxons never used place-names as personal names. It is clear then that when a Saxon ‘ancestor’ is claimed to have been called Bertram Ashburnham or William Pewse, he must be a fake, since no Saxon was ever called Bertram or Ashburnham or William or Pewse.

The case of the Normans is different. During their residence in France the Normans had almost completely dropped their Norse names, and had adopted such Frankish names as Richard, Hugh and Baldwin. William [the Conqueror’s] army contained many Frenchmen and Flemings, as well as Normans, but their names were much the same. There was also a contingent of Bretons, who had some names of their own. Of these, Alan was the commonest, though the ancestor of the FitzAlans ... did not come over till the next century.

In that century [the 12th] a few Biblical names began to creep in, probably under the influence of the Crusades [the First Crusade began in 1095]; previously such names as John and Thomas are not found among either Normans or Saxons.

Unlike the Saxons, the Normans had surnames, but before about 1150 these were personal and not hereditary. William, son of Hugh and lord of Dinard, would be called William FitzHugh and William de Dinard, or both. His son would be called Richard FitzWilliam, and would be called Richard de Dinard only if he owned it. If we find Robert de Dinard succeeding Richard de Dinard, it by no means follows that they were relatives; Richard might have sold, or died without heirs, or been dispossessed.

About 1400 place-names began to be borne as surnames without ‘de’ or ‘of’ before them, and it was then, and not till then, that it became possible for men to be called Bertram Ashburnham or William Pewse.

‘The Hero’, Lord Raglan (1936): Ch 2

And what about women? Well, ‘the most popular names’ for the 12thcentury look quite unusual to us now. They include (see ) Edith, Aethelflaete, Alfgyth, Burwenna, Botilda, Annora, Rikilda, Cecily, Godeva, Ingrid... all much more common than ‘Rosamond’ or ‘Rosmunda’ which turns up only three times between 1206 and 1282. Of course there were unusual names in every century. I really adore the wonderful Dayluue or ‘Daylove’ [OE *Dæglufu], which also turns up three times.

In the 13th century (see ) Matilda comes top of the list, followed by Alice, Agnes or Agneta, Edith, Emma, Margaret, Mabel, Alviva, Isabella or Ysabel, Christiana and Juliana. Most of these are still common in the 14th and 15th centuries, but Joan or Johana now joins the list, as do Katherine and Elizabeth.

By the 16th century (see ) Elizabeth seems most popular, along – in diminishing order – with Margaret, Jane, Agnes, Isabel, Anne, Alice, Katherine, Jennet, Elinor, Margery, Mary, Dorothy, Ellen, Barbara and Susanna. Returning briefly to the Fair Rosamund: she was born circa 1148 at Clifford Castle in Herefordshire, became Henry II's mistress probably around 1166, and died in 1176, not yet thirty. Her wikipedia entry calls her Rosamond Clifford, but as Raglan points out, that wouldn't have been how she was known during her life. She was Rosamund, daughter of Walter FitzRichard (aka Walter de Clifford). Her mother was Margaret. And she had two sisters, Lucy and Amice.

Rosamund, Lucy and Amice: that is, Rose of the World, Light, and Beloved... I wonder which parent it was who chose such delightful names for their three beautiful daughters?

Picture credits

Fair Rosamund by Waterhouse, Wikimedia Commons Fair Rosamund by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Wikimedia Commons

March 23, 2021

"The sweet of the year": Shakespeare’s spring flowers

It’s Act 4, Scene 3 of ‘The Winter’s Tale’ and Autolycus the thief is singing a song about spring.

When daffodils begin to peerWith hey, the doxy over the dale,Why then comes in the sweet of the yearFor the red blood reigns in the winter’s pale.

The white sheet bleaching on the hedgeWith hey, the sweet birds, O how they sing…

Introducing himself to the audience as a follower of Mercury (god of thieves) and a ‘snapper-up of unconsidered trifles’, he intercepts a country yokel heading to market to buy provisions for the sheep-shearing festival – a shopping list which includes sugar, currents, rice, saffron, mace, nutmegs, ginger, prunes and raisins. (How and why did the English turn away from these yummy, spicy groceries and end up with the 19th and 20th century cuisine of the plain and boiled?) Relieving him of his money, Autolycus heads for the festival itself, where he expects to ‘make this cheat bring out another’.

Next scene: Perdita arrives at the sheep-shearing festival like a vision of spring – ‘No shepherdess/But Flora, peering in April’s front’ – to hand out flowers like a more positive version of Ophelia. ‘Reverend sirs,’ she welcomes Polixenes and Camillo, ‘For you there’s rosemary and rue. These keep/Seeming and savour all the winter long./Grace and remembrance be to you both/And welcome to our shearing/.’ When the middle-aged Polixenes protests with mild irony: ‘Well you fit our ages/With flowers of winter’, Perdita adds to them ‘flowers of middle summer’: ‘lavender, mints, savory, marjoram,/The marigold, that goes to bed wi’ the sun/And with him rises, weeping.’ If it’s springtime though, how does she have these summer flowers to hand?

The answer is simple: it isn’t springtime. As Thomas Tusser points out in ‘Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry’ (printed in 1557, a year before Elizabeth I became queen and seven years before Shakespeare was born) sheep-shearing happens in June.

Wash sheepe (for the better) where water doth run,And let him go cleanly and drie in the sun,Then shear him and spare not, at two daies an end,The sooner the better his corps will amend.

Besides reminding us with his jog-trot lines just how wonderful Shakepeare’s poetry is, Tusser underscores the rural reality that lies behind the play. Though probably not with quite so many expensive ingredients, English as well as Arcadian farming wives were cooking plentifully for the sheep-shearing feasts.

Wife make us a dinner, spare flesh neither corne Make wafers and cakes, for our sheepe must be shorne, At sheepe-shearing neighbours none other thing crave But good cheere and welcome like neighbours to have.

Act 4 of ‘The Winter’s Tale’ is, therefore, set firmly in the month of June and that is why Perdita has only summer flowers to distribute. (And rosemary and rue, which are available all year round). But then why has Autolycus just been singing so merrily of spring? And Perdita herself conjures spring in her next words as, speaking to Florizel, to Mopsa and Dorcas, she wishes she had some springtime flowers to gift and suit their youth.

…daffodilsThat come before the swallow dares, and takeThe winds of March with beauty; violets dimBut sweeter than the lids of Juno’s eyes,Or Cytherea’s breath; pale primrosesThat die unmarried ere they can beholdBright Phoebus in his strength – a maladyMost incident to maids; bold oxlips and The crown imperial; lilies of all kinds,The flower de luce being one. O these I lackTo make you garlands of.

Well, Shakespeare is able to have it all ways: and why not? Sheep-shearing happens in early summer, but Autolycus’s song and Perdita’s speech conjure up springtime too. Both are times of rejuvenation and hope, the sweet of the year… and the young lovers Perdita and Florizel represent the hope of healing for their parents’ breach. ‘The Winter’s Tale’ is a tisane of flowers.

‘With fairest flowers,’ says Arviragus in ‘Cymbeline’, speaking sad words over the body of the boy Fidele (actually his sister Imogen, not really dead, just drugged):

Whilst summer lasts and I live here, Fidele,I’ll sweeten thy sad grave. Thou shalt not lackThe flower that’s like thy face, pale primrose, norThe azured harebell, like thy veins; no, norThe leaf of eglantine, who not to slanderOutsweetened not thy breath... [Act 4 Sc 2]

Shakespeare associates primroses with youth and beauty, but often in contexts of fragility and death. (Although growing en masse, these delightful flowers appear as ‘the primrose path’ of worldliness or temptation: Ophelia begs Laertes to avoid ‘the primrose path of dalliance’ and the Porter in Macbeth claims to have ‘let in some of all professions that go the primrose way to th’ everlasting bonfire.’) Perdita’s primroses ‘die unmarried’: a sentiment echoed by Milton in ‘Lycidas’: ‘the rathe primrose that forsaken dies’. The archaic word ‘rathe’ means ‘over-eager’, ‘too early’. Primroses don’t live to see the summer… but then neither do daffodils, and no poet seems ever to have regarded them as emblematic of early death. Flowers affect us in very different ways. Our native daffodils ‘come before the swallow dares/And take the winds of March with beauty’: they are tall, daring, triumphant flowers with actual golden trumpets. In ‘Shakespeare’s Wild Flowers’ (1935) Eleanour Sinclair Rohde says:-

"In Shakespeare’s day daffodils were favourite flowers for chaplets, and he refers to this fact in ‘The Two Noble Kinsmen’:

… I’ll bring a bevy,A hundred black-eyed maids that love as I doWith chaplets on their heads of daffodillies… " [Act 4 Sc 1]

In fact Shakespeare’s collaborator John Fletcher was probably responsible for these lines, and the context in which they occur is an obvious borrowing from the death of Ophelia – a mad, lovesick girl, knee-deep in a lake, singing and plaiting garlands of waterflowers. It’s nothing like as good, though. I’m tempted to imagine a dialogue between two professional playwrights, writing to deadlines:

[John Fletcher, scratching his head:] ‘Will, what am I going to do with the Jailer’s Daughter?’ – ‘You mean the girl with the unrequited love for Palamon?’ – ‘Yup.’ – ‘The usual, I suppose. Can’t she run mad?’ – ‘I suppose so. What do mad girls do?’ – ‘I don’t know… mess about with flowers? Look, Jack, I’m busy. Read this and do your own version.’ [Will tosses over a copy of Hamlet…]

Primroses are pale, low, poignant, early, ‘rathe’ – they come before the spring is well advanced and we wonder if they’ll survive the next frost. Gertrude’s words at Ophelia’s funeral – ‘I thought thy bride-bed to have deck’d, sweet maid, And not t’have strewed thy grave’ – might echo the sentiments of many an onlooker at a spring funeral, as the wastage of winter took its toll of young people made ‘lean’ by January blasts.

But spring is always a time of resurrection. Fidele lives and, revealed as Imogen, is reunited with her repentant father and husband. Perdita’s mother Hermione, long thought dead, descends from her plinth to embrace her daughter and bless her marriage with Florizel. Wounds are healed, families are made whole. It is the sweet of the year, and time to rejoice.

Picture credits

John Fawcett plays Autolycus in The Winter's Tale (1828) by Thomas Charles Wageman

Perdita distributes flowers in Act 4 of The Winter's Tale [untraced origin]

Flower de luce, or yellow flag iris: Redouté's Les Liliacées, 1808

Primroses and Bird's Nest: William Hunt, 1790-1864

Wild Daffodils, Narcissus Pseudonarcissus:, Antoine de Pinet, 16th century

Ophelia, detail: John Millais, 1852, Tate

March 4, 2021

From the Wild Hunt to the Fairy Rade

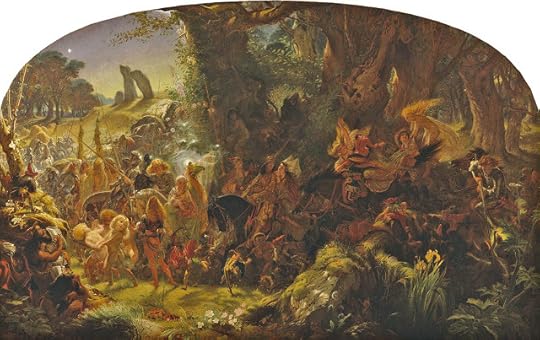

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's Eve'

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: 'The Fairy Rade: Carrying Off A Changeling - Midsummer's Eve'

This account from an unnamed 'old woman’ of Nithsdale tells of a Fairy Rade or cavalcade of the fairies which she had witnessed as a lass. It was recorded by Allan Cunningham and R.H. Cromek in Remains of Nithdale and Galloway Song (1810) and is repeated verbatim in Thomas Keightley’s Fairy Mythology (1828). It is strangely convincing, as folk accounts often are. (Translation below!)

“In the night afore Roodmass I had trysted with a neebor lass a Scots mile frae hame to talk anent buying braws i’ the fair. We had nae sutten lang aneath the haw-buss till we heard the loud laugh of fowk riding, wi’ the jingling o’ bridles, and the clankin’ o’ hoofs. We banged up, thinking they wad ride owre us. We kent nae but it was drunken fowk ridin’ to the fair i’ the forenight. We glow’red roun’ and roun’ and sune saw it was the Fairie-fowks Rade. We cowred down till they passed by. A beam o’ light was dancin’ owre them mair bonnie than moonshine: they were a wee wee fowk wi’ green scarfs on, but ane that rade foremost, and that ane was a good deal larger than the lave wi’ bonnie lang hair, bun about wi’ a strap whilk glinted like stars. They rade on braw wee white naigs, wi’ unco lang swooping tails, an’ manes hung wi’ whustles that the win’ played on. This an’ their tongue when they sang was like the soun’ of a far-away psalm. Marion and me was in a brade lea fiel’, where they came by us; a high hedge o’ haw-trees keepit them frae gaun through Johnnie Corrie’s corn, but they lap owre it like sparrows, and gallopt into a green know beyont it. We gaed i’ the morning to look at the treddit corn; but the fient a hoofmark was there, nor a blade broken.”

Here is my tamer English version:

In the night before Roodmas [the Feast of the Cross, May 3rd] I had met up with a neighbour lass a Scots mile from home [a Scots mile was about 220 yards longer than an English mile], to talk about buying pretty things at the fair. We hadn’t been sitting long under the hawthorn bushes when we heard the loud laugh of folk riding, with jingling bridles and clattering hoofs. We jumped up, thinking they would ride over us. We assumed it was drunken folk riding to the fair in the early evening. We stared round and about and soon saw it was the Fairy-folks Ride. We cowered down as they passed by. A beam of light was dancing over them, prettier than moonshine: they were tiny little folk with green scarves on, all but the one who rode in front, who was a good deal bigger than the rest, with lovely long hair bound about with a band that glinted like stars. They rode on fine little white horses, with uncommonly long sweeping tails, and manes hung with whistles which the wind played on. This, and their voices when they sang, was like the sound of a far-away psalm. Marion and I were in a broad pasture field, where they came by us; a high hedge of hawthorn trees barred them from going through Johnnie Corrie’s corn, but they leaped over it like sparrows and galloped into a green hill beyond it. We went next morning to look at the trodden-down corn, but devil a hoofmark [ie: not a single hoofmark] was to be seen, nor a blade broken.

Charming as this seems, it’s quite clear that the young women’s experience was startling, even alarming. Hearing the loud, possibly drunken laughter, jingling bridles and thudding hoofs, they leap up in fear of being trampled – but when they see the fairy troop, they cower down.

The Lowland Scots word ‘rade’ means ‘raid’. It’s derived from Old English rād(‘road’) used in the sense of a (usually military) expedition or incursion upon horseback, ‘a foray, an inroad’ as the OED states. So a fairy rade really is a ‘raid’: an implicitly threatening intrusion into the everyday world. No matter how beautiful fairies may be, they are always dangerous, and the Fairy Rade is related to the phenomenon of the Wild Hunt or familia Herlequini, the host of the dead. Related, yet no longer the same, for superstitions are in constant evolution. The Fairy Rade branched off, you might say, from the Wild Hunt, stories of which of course continued to exist in parallel. Jacob Grimm, in his Teutonic Mythology, connected the Germen wilde Jagt (wild hunt) or wütende heer (furious horde) with Wotan – Odin, the wild or mad god who goes ‘driving, riding, hunting … with valkyrs and einheriar in his train’, and versions of the Wild Hunt led by demi-gods and legendary characters both male and female have been recorded across Europe: it was always bad luck to see it – a harbinger of death. But how did the ancient and fearsome host of the dead evolve into the green-clad trooping fairies of early 19thcentury Nithsdale?

The Wild Hunt by Johann Corde

The Wild Hunt by Johann CordeIn a marvellous book, Elf Queens and Holy Friars (Uni. of Pennsylvania Press, 2016) Professor Richard Firth Green suggests that medieval clerical commentators put a deliberately dark spin on the Europe-wide concept of the Wild Hunt. I’m not entirely convinced by this, for I suspect the familia Herlequini had its frightening side well before Christianity. However, it could certainly be adapted to a Christian agenda, and Green contrasts two of the earliest accounts. The Anglo-Norman monk Orderic Vitalis, writing of an event ‘witnessed’ in 1091, depicts a grim procession of dead knights, priests, ladies and commoners suffering dreadful torments for their sins. A half century or so later, Anglo-Norman courtier Walter Map tells in his book De Nugis Curialium the story of the British king Herla who, returning from attendance at a fairy king’s wedding, finds that centuries have elapsed and he and his company are now doomed to wander the hills forever. Green drily comments: ‘People could hardly be allowed to believe that Herla and his followers were living happily in fairyland.’ Reading this, I was struck by the memory of Aucassin’s famous defiance – ‘To Hell will I go!’ – in the 13thcentury French romance Aucassin and Nicolette:

For to Hell go the fine scholars and the fair knights who are slain in the tourney and the great wars, and the good men-at-arms and all noble men. With them I will go: and there go the lovely courteous ladies who have two or three lovers as well as their lords, and there go the gold and silver and ermine and miniver, and there go the harpers and minstrels and kings of this world: I will go with them, so only that I have Nicolette my sweetest love beside me.

Aucassin & Nicolette (artist unknown to me)

Aucassin & Nicolette (artist unknown to me)One might well imagine that Aucassin has Orderic’s gloomy vision of the trooping dead clearly in his mind, and is deliberately subverting, diverting it. This gaily-clad cavalcade will surely end up in fairyland – not hell – and Aucassin’s vehement, emotional rejection of the stark hell/heaven binary may express a more general sense that alternatives had to be available. Could love as romantic as Aucassin’s really be a sin? Where did the unbaptised babies go, and men who died in battle unshriven, and mothers who died in childbirth?

They were taken away into fairyland, according to the anonymous author of the late 13th century romance Sir Orfeo, for when Orfeo is admitted to the fairy king’s subterranean crystal castle, he sees lying all about him in the courtyard: ‘folk that had been brought here, and were thought to be dead, but weren’t…’ And there follows a grim catalogue of the headless, maimed, wounded, mad, drowned and burned… ‘Wives lay there in child-bed … and wondrous many others lay there too: as they had fallen asleep at noon each was taken from this world and carried there by fairy magic.’ It’s got to be better than hell.

‘Queen of heaven ne am I naught,’ says the fairy queen to Thomas of Ercildoune, in the medieval Scots romance of that name:

‘For I took never so high degree.

But I am of another countree.’

Illustration: HM Brock

Illustration: HM BrockHer counterpart in the much later ballad of Thomas the Rhymer(first published in Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, 1802/3) points out to Thomas three ways that diverge ahead of them: the thorny path of righteousness, the easy road of wickedness, and lastly the ‘bonny road that winds about the ferny brae’ which will lead them to fair Elfland. It must have been tempting! And once you’ve imagined fairy land as a place, and a sumptuous, royal place at that, what remains but to wonder what the people of Elfland do? The answer was obvious: they danced, and they rode out. Not just because of the living tradition of the Wild Hunt, but because this was the way kings, queens and nobles always displayed themselves to the people. Like earthly kings, fairy kings and queens rode out in procession for three main purposes – ceremony, hunting or war – so that the Seelie Court and the Unseelie Court are aspects of the same thing.

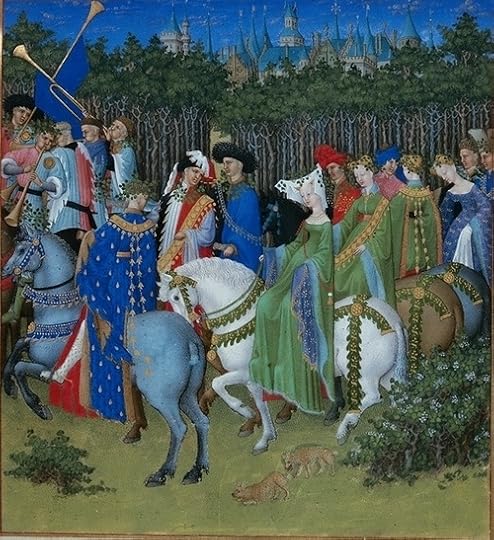

Les Tres Riches Heures, Musée de Condé, Chantilly, France by the Limbourg brothers

Les Tres Riches Heures, Musée de Condé, Chantilly, France by the Limbourg brothers

The medieval romances emphasise the courtly aspects of the fairies: in Walter Map’s 12th century tale of King Herla, the unnamed pigmy fairy king may be grotesque in appearance but his entourage is dressed in splendid livery and jewels. He eats and drinks from vessels and plates carved of single precious stones and his underground palace is lit by innumerable lamps as if it were the palace of the sun. The fairy king of Sir Orfeo comes by with a company of more than two hundred knights and damsels dressed in white and riding on snow-white steeds; the king’s crown is made neither of gold or silver, but all of one precious stone that shines as bright as the sun. And in the late medieval French romance of Huon of Bordeauxthe child-size fairy king Oberon (‘the dwarf of the fairy’) entertains Huon by magicking up a beautiful palace, ‘hung with rich cloth of silk beaten with gold, with tables set ready full of meat’, and he and his guests wash their hands in ‘basins of gold, garnished with precious stones’ and are seated on benches of gold and ivory.

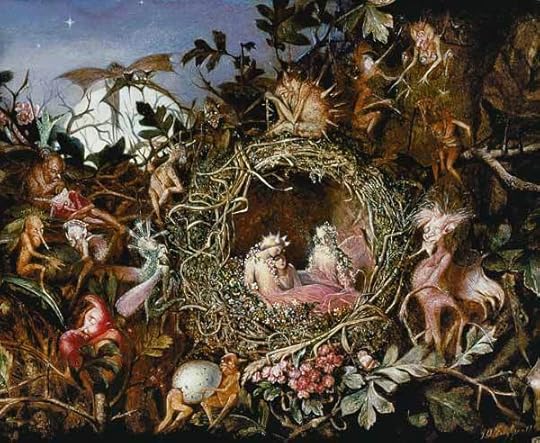

Fairies in a Bird's Nest, by John Anster Fitzgerald

Fairies in a Bird's Nest, by John Anster FitzgeraldBy the late 16th century, however, literary representations of the fairy rade had become far more rustic and a lot less serious. Writers like Shakespeare and Jonson (and in the 17th century, Drayton and Herrick) popularised the notion of the fairies as amusing miniature creatures. In part of his Flyting (a poetic duel) against fellow-poet Patrick Hume of Polwart some time in the early 1580s, the Scots writer Alexander Montgomerie includes a fanciful account of the fairy rade:

In the hinder end of haruest, on Alhallow even

When our good nighbours do ryd, gif I read right,

Some buckland on a bunwand, and some on a been,

Ay trottand in trupes from the twilight;

Some sadleand a shoe aip all graithed into green,

Some hobland on ane hempstalke, hoveand to the hight.

The King of Pharie, and his curt, with the Elfe Queen,

With many elrich Incubus, was rydand that night…

In rough translation:

At the back-end of harvest, on All Hallows eve,

When our good neighbours [euphemism for the fairies] do ride, if I read right,

Some buckled on a plant-stem and some a dry stalk [as weapons],

Aye trotting in troops from the [beginning of?] twilight;

Some saddling a she-ape all harnessed in green,

Some jogging on a hempstalk, hovering to the height.

The King of Fairy and his court, with the Elf Queen

With many eldritch Incubus, was riding that night…

This may seem whimsical or even cute to us, but the point for Montgomerie is to smear Polwart’s character and morals. For the Reformation has occurred: the fairies are now more disreputable than dangerous, and he continues with a scurrilously imaginative account of Polwart’s supposedly monstrous origins:

There ane elf, on ane aipe, an vnsell begat,

Into ane pot, by Pomathorne;

That bratchart in ane busse was borne;

They fand ane monster, on the morne.

War faced not a cat.

That is:

There an elf, on an ape, begot a wretch,

In a pit near Pomathorn [a place in Midlothian];

That brat was born in a bush;

They found a monster in the morn,

Worse faced than a cat.

You cannot write this kind of thing if you really believe in fairies. Even though some of the fairy lore is genuine (flying on hemp-stalks, for example), you can tell that Montgomerie's attitude towards these country superstitions is part scepticism, part mockery. A few years later in 1599, King James VI of Scotland (soon to succeed Elizabeth as James I of England) writes with disbelief and disapproval in his Daemonologyof the popular belief in spirits called ‘by the Gentiles…Diana, and her wandering court’ and ‘amongst us, the Phairie… or our good neighbours’:

How there was a King and Quene of Phairie, of such a iolly [jolly] court and train as they had, how they had a teynd [tithe], & dutie [tax], as it were, of all goods: how they naturallie rode and wente, eate and drank, and did all other actiones like naturall men and women…

He adds that this is ‘no[t] anie thing that ought to be beleeved by Christians’: in fact, the only possible explanation is that ‘the devil illuded the senses of sundry simple creatures, in making them beleeve that they saw and harde [heard] such thinges as were nothing so indeed.’

But if poets and playwrights and kings no longer believed in fairies, many ordinary country people and other common folk undoubtedly still did - and they were interested in them, which is why some of the now unfashionable medieval romances ended up as tales in chapbooks or sung as ballads. The 13thcentury Sir Orfeo became the Shetland ballad King Orfeo: it was collected there in 1865 and was still being sung up till the mid 20th century, when two different tunes were recorded for it. And Thomas of Ercildoune morphed into the ballad of Thomas the Rhymer (collected by Walter Scott), when a fairy queen as richly attired as any of her predecessors comes riding down past the Eildon tree on her milk-white steed –though without followers:

Her shirt was o’ the grass-green silk

Her mantle o’ the velvet fine:

At ilka tett o’ her horse’s mane

Hung fifty siller bells and nine.

The ballad of Tam Lin includes a famous account of a fairy rade, and one that adds a twist to King James’s dour comment about the fairy king or queen claiming a ‘teynde’ or tithe on earthly goods. For on Hallowe’en, young Tam Lin will pay the seven-year ‘tiend’ the fairies owe to hell – unless his lover Janet can save him.

Just at the mirk and midnight hour

The fairy folk will ride;

And they that would their true love win,

At Milescross they maun bide.

…

About the middle of the night

She heard the bridles ring;

This lady was as glad of that

As any earthly thing.

First she let the black pass by,

And syne she let the brown

But quickly she ran to the milk-white steed

And pu’ed the rider down…

This is as serious a treatment as it could be, far removed from the satire and whimsy of Mongomerie, and untouched by the notion that trooping fairies were diminutive. The oral tradition preserved the gravity of the fairy kingdom. But writers couldn’t take fairies seriously and expect to be taken seriously themselves: they had to guy it up. It’s not that you can’t find any fairy lore in the poetry of Robert Herrick (1591-1674), it’s just that he’s at such pains to make it all light, decorative, amusing. In his poem The Beggar to Mab, the Fairy Queen, the beggar pleads with Mab to feed him:

Give me then an ant to eat,

Or the cleft ear of a mouse…

Or, sweet lady, reach to me

The abdomen of a bee…

The Fairy Queen's Messenger, by Richard Doyle

The Fairy Queen's Messenger, by Richard DoyleContrast such elegant flippancy with the genuine shiver we get at the end of the ballad of Tam Lin when the fairy queen, furious that she’s lost her knight, swears that if she had known ‘what now this night I see,/I wad hae ta’en out thy twa grey een,/And put in twa een o’ tree.’

Andrew Lang, in The Book of Dreams and Ghosts, tells of a man called Donald Ban who fought at the battle of Culloden and was afterwards troubled by a bocan (boggart) which made great difficulties for him. The bocan was thought to be the spirit of a man who had died at the battle, and it once led Donald to dig up some plough-irons which had been hidden while he was alive: as Donald lifted them, ‘the two eyes of the bocan were causing him greater fear than anything else he ever heard or saw.’ This is very like the incident in the medieval Icelandic Grettir’s Saga, where Grettir slays the corpse-ghost Glam and is never able to shed the terror of seeing Glam’s eyes roll horribly in the moonlight... Donald Ban saw other fairy sights too: for out hunting one day ‘in the year of the great snow, at nightfall he saw a man mounted on the back of a deer ascending a great rock. He heard the man saying, “Home, Donald Ban,” and fortunately he took the advice, for that very night there fell eleven feet of snow in the very spot where he had intended to stay.’

Country people – small-holders, crofters, farmers – took the world of spirits and fairies seriously because they had to: they lived liminal lives themselves, dependent on weather, on crops doing well, on animals thriving. Anything that might tip the balance, anything that might help or hinder their own survival, was worth paying attention to. So they kept a belief in their ‘good neighbours’ the fairies, whom it really wasn’t worth offending, and they kept telling the old tales and finding new ones. That is why the story of the fairy rade of Nithsdale with which I opened this post is so compelling. The fairies those young lassies witnessed may have been ‘tiny little folk in green scarves’, bedecked with stars, and shining with a light ‘prettier than moonshine’ – but they were really scary.

And that’s why the two girls cowered down, afraid of being seen.

Baccanal: Richard Dadd

Baccanal: Richard Dadd

February 16, 2021

Arthur's Voyage to the Otherworld

Perhaps you don't tend to think of Arthur as a voyager? Bear with me, and I'll explain.

Some of the earliest mentions of Arthur come from ninth or tenth century Welsh literature – just glancing references, as if to someone already well-known. The earliest of all may be a couple of lines from the poem Y Gododdin, in which another warrior is compared with Arthur:

He fed black ravens on the ramparts of a fortress,

Though he was no Arthur.

This makes sense if the historical Arthur really was an early British war leader: his name perhaps a nickname or pseudonym: ‘the Bear’, suitable for a fighter who may have wished to maintain an air of terrifying mystery. Whoever the historical Arthur may have been (Andrew Breeze, a professor of philology at the University of Navarre, has put forward the interesting theory that he was a 6th century warlord from the Strathclyde area in Northern Britain, whose battles, like those of the Ulster cycle, were glorified cattle raids against other Britons rather than against the Anglo-Saxons), the name of Arthur became associated with legends connected with supernatural figures from Celtic mythology. And such stories continued to be told about him in all parts of Celtic – that is British – Britain: and also in Brittany, the region of France to which many British Celts migrated after the fall of Roman Britain.

Even in Sir Thomas Malory’s late 15th century ‘Le Morte D’Arthur’ with all its courtly French additions and sources, plenty of Welsh and Celtic personages and motifs remain: the most obvious is Merlin himself, and the Lady of the Lake who gives Arthur his sword Excalibur, and there is Arthur’s shadowy relationship with his half-sisters: Morgause the mother of their son Mordred, and Morgan le Fay, Morgan the enchantress – whose name chimes with that of the Morrigan (‘great queen’ or ‘phantom queen’), the Irish Celtic goddess of battle and fertility. At any rate, Morgan is one of the queens who carry the wounded king away to the Isle of Avalon after the battle of Camlann.

And when they were at the water side, even fast by the bank hoved a little barge with many fair ladies in it, and among them all was a queen, and all they had black hoods, and all they wept and shrieked when they saw King Arthur.

…‘Comfort thyself,’ said the king, ‘…for in me is no trust for to trust in, for I will into the vale of Avilion to heal me of my grievous wound, and if thou hear never more of me, pray for my soul.’

But ever the queen and ladies shrieked, that it was pity to hear.

The shrieking and keening women, companions to a powerful sorceress, the ship that carries the hero away to the island of the dead, the island of apples...surely there are echoes here of the voyage of Jason to the Hesperides, home of the sorceress Medea, and of Odysseus to the island of Circe and the shores of Hades?

But much closer to home is a highly cryptic account of a voyage by Arthur to the Underworld. It’s the marvellous Welsh poem Prieddeu Annwfn, preserved in the single 14th century manuscript of The Book of Taliesin, but dated (cautiously) by internal linguistic evidence to around 900 AD. Here’s a link to the poem, with notes. It's an account of a raid led by Arthur, in his ship Prydwen, on Annwn, the Welsh underworld. There's a gorgeously illustrated book of this adventure by John and Caitlin Matthews:-

Annwn is described by a number of different epithets. Are these simply varying descriptions or manifestations of the same place, or are they intended as different locations which Arthur and his men encounter along their way, island-hopping as Jason and Ulysses do, gradually approaching their destination through a transformed and numinous sea-scape? The poem tells how Arthur and his men travel to Caer Sidi ‘The Mound Fortress’;Caer Pedryuan ‘the Four-Peaked Fortress’ – also described as Ynis Pybyrdor ‘isle of the strong door’. They travel to Caer Vedwit ‘the Fortress of Mead-Drunkenness’, Caer Rigor ‘Fortress of Hardness’, Caer Wydyr ‘Glass Fortress’, Caer Golud ‘Fortress in the Bowels [of the Earth?]’, Caer Vandwy ‘Fortress of God’s Peak’, and Caer Ochren‘Enclosed Fortress’. Alan Garner used some of these names in his book Elidor, which references the poem in other ways.

The aim of the expedition was to bring back a cauldron belonging the lord of Annwn. We're not thinking blackened kitchen pots here, but inspirational, magical, probably sacred objects like the 1st century BC Gundestrop cauldron, pictured above. One of the many scenes on its sides depicts a pony-tailed warrior dipping a man into another such cauldron headfirst, probably to restore him to life:

In 'Elidor', one of my favourites of Alan Garner’s books, the children bring four treasures out of the Mound of Vandwy, corresponding to the Four Treasures of the Tuatha de Danaan: a spear, a sword, a stone and a bowl: 'a cauldron, with pearls above the rim. And as she walked, light splashed and ran through her fingers like water'. Taken into the workaday world of 1960's Manchester, however, the objects change appearance, and Helen finds she is carrying only 'an old cracked cup, with a beaded pattern moulded on the rim.' Once these treasures have been buried in the garden for safekeeping, all kinds of strange disturbances begin to occur, culminating in the eruption of the unicorn Findhorn onto the city streets.

Here is the second stanza of the Prieddeu Annwfn:

I am honoured in praise. Song was heard

In the Four-Peaked Fortress, four times revolving.

My poetry, from the cauldron it was uttered.

By the breath of nine maidens it was kindled.

The cauldron of the chief of Annwfn: what its fashion?

A dark ridge around its border, and pearls.

It does not boil the food of a coward...

And before the door of hell lamps burned.

And when we went with Arthur in his splendid labour,

Except seven, none rose up from Caer Vedwit.

Most of the eight stanzas end with a variation on the recurrent line: ‘Except seven, none returned’: by ordinary standards the expedition appears to have been disastrous, but this is no ordinary poem. Fateful and gloomy, mysterious as Arthur himself, all we can gather from it is some sense of a venture, by ship, by sea, into the Otherworld, and - perhaps – a description of a mound or island where a youth, Gweir, is imprisoned, lapped with a heavy blue-grey chain. Of a four-peaked fortress with a strong door, guarding a cauldron full of the magical life-giving mead of poetry, warmed by the breath of ‘nine maidens’. And of a fortress of glass with six thousand men lining the walls (‘it was difficult to speak with their sentinel’).

In the medieval story of Culhwch and Olwen in the Mabinogion, Arthur sails to Ireland in his ship Prydwen to steal the cauldron of Diwwnach Wyddel: not just any old cauldron either, for it’s also listed in ‘The Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain’ as the cauldron of Dyrnwich the Giant, which will not boil the food of a coward. Clearly the same cauldron as that which Arthur went to find in Annwn, and doubtless the same also as the Irish Cauldron of the Dagda, from which 'no man ever went away unsatisfied'. How old is this legend of magical, life-giving cauldrons? As old as Medea's? Could the ancient British and Irish cauldrons be the ultimate origin of the witches' cauldron we find in 'Macbeth'? Who knows? But the legends all say that Arthur did not die. He only sleeps. And is waiting in the Otherworld to return to us, in our hour of need.

Picture credits:

The Death of Arthur by James Archer, 1823-1902

The Death of Arthur by Katharine Cameron

The Gundestrop Cauldron, wikipedia

Detail from the Gundestrop Cauldron, wikipedia

The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon (detail) by Edward Burne Jones

February 4, 2021

How Do Portals Really Work?

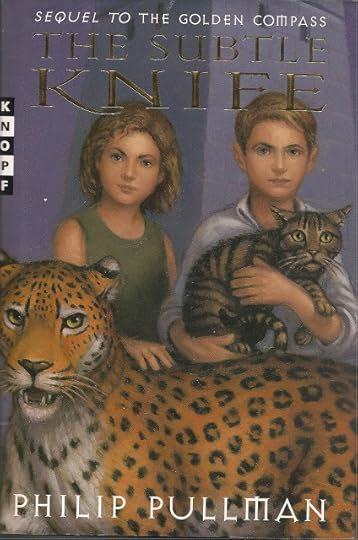

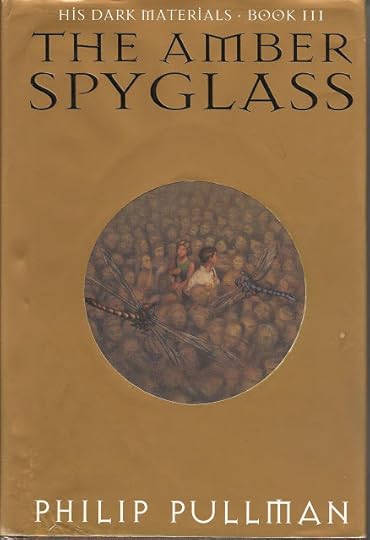

In my last post I looked at the two very different ways in which the characters of Philip Pullman’s trilogy ‘His Dark Materials’ pass between worlds. ‘If light can cross the barrier between the universes,’ says Lord Asriel in ‘The Golden Compass’, ‘if Dust can … then we can build a bridge and cross. It needs a phenomenal burst of energy.’ He obtains this energy by severing the link between child and daemon, sacrificing Roger and using wires to ‘harness’ the power of Dust in the Aurora. Asriel’s bridge is the result of a single, dynamic, explosive (and emotionally charged) event. Then in ‘The Subtle Knife’ and ‘The Amber Spyglass’ we learn of innumerable windows linking the universes, opened by a knife forged centuries before by ‘learned men’ in the city/world of Cittágazze: the product of an unexplained otherworld science, ‘subtle’ in effect as well as in nature. Each method on its own is impressive, but I’ve always been slightly uneasy about their co-existence in the same world – that is, ‘the fictional world of the three books’. Maybe that’s just me.

Even though Pullman’s trilogy contains ghosts, witches, angels, harpies and Spectres, ‘His Dark Materials’ isn’t a world of magic, and so the portals don’t work by magic either. The energy released by severance of child from daemon is 'explained' by analogies with electro-magnetism and atomic fission, and since most of us have at best a hazy grasp of such things (me included), we accept it.

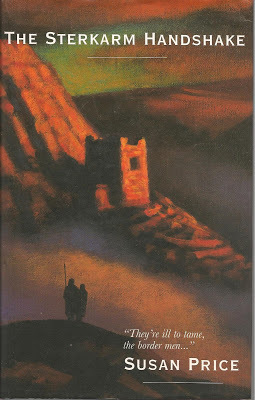

Susan Price uses a similar method in ‘The Sterkarm Handshake’, the first book of her magnificent ‘Sterkarm Trilogy’ set in the reiver borderlands between England and Scotland. A 21st century British corporation called the FUP has invented a Time Tube which takes people not just into the 16thcentury, but into the 16th century of closely parallel universes and the lands owned by the wild Sterkarm clan, who quite reasonably pigeon-hole their 21stcentury visitors as Elves. Despising the Sterkarms as naïve, primitive and ignorant, the company sets out to exploit them, trading small numbers of aspirins for valuable products like the locally produced ‘organic’ beef. However, the Sterkarms are not in the least naïve, as the FUP discovers to its cost.

The world of the ‘Sterkarm Trilogy’ contains no magic. The Tube is powered by a ‘cold fusion reactor’ ‘no bigger than a small family car’, and is a huge piece of ‘industrial concrete piping’ supported by a framework of steel girders. Here it is, seen through the eyes of a 21st century character called Bryce:

In front of each round mouth was a platform big enough for a truck… The mouths of the Tube, at both ends, were masked by hanging fringes of plastic strips.

From each platform a ramp with a surface of textured rubber sloped down to the ground. The one nearer Bryce touched the gravel drive. The one that sloped down from the rear platform didn’t quite touch the grass of the lawn, and concrete blocks had been placed to support it, when it was present. […] That end of the Tube spent a lot of time in the 16th century. It was easy to tell which was which, because the end that spent all its time in the 21st was dirty. The concrete was grey and streaked, and stained where it touched its supporting girders. The concrete of the half that spent much of its time in the 16th was still white and unstained. The rain of the 16th century wasn’t full of dirt, and it wasn’t acid.

The Sterkarm Handshake, 5

We don’t need to be told how it works, because the viewpoint character, Bryce, isn't a scientist, so he doesn’t know either. He simply marvels at it in operation.

You heard the noise of the Tube spinning – some part of it, hidden inside the concret pipe, spun, so he was told. A roar, increasing in pitch to a whine, and then passing almost out of hearing. And then one end of the Tube vanished. … As fast as light switching off, it blinked out of sight.

The Tube is so well thought through and clearly described out that we accept it just as Bryce does:

[He] tried to think about the Tube as he did about his fridge, and his multi-media console. He wasn’t sure how any of them worked. He just expected they would, was glad when they did, and got on with his life.

That's a masterly piece of writing... The Time Tube is a machine, a piece of technology: and ‘The Sterkarm Trilogy’ is the least fantastical of the fantasies I’ve looked at in these essays. The story inhabits the debatable lands between fantasy and sci-fi, where much good fiction resides, for though there is no magic, ghosts or witches or fairies, there are many references to border ballads and folktales. If you haven’t read them yet, do! The first book won the Guardian Fiction prize and was shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. They are wonderful, witty and bloody – and not for children.

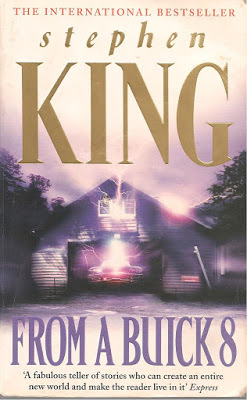

The portal in Stephen King’s novel ‘From a Buick 8’ is totally unexplained and (spoiler alert) remains so. One day in 1979, two decades before the ‘present’, a car rolls up at a small filling station in rural Pennsylvania. It’s an old-style, dark blue Buick Roadmaster, in mint condition. A man or what looks to be a man gets out, dressed in a black trenchcoat and black hat, and heading in the direction of the toilet cabin tells the youngster who mans the pumps to ‘Fill ‘er up’ in a voice ‘that sounded like he was talking through a mouthful of jelly’. He is never seen again. The Buick – if that’s what it is – sits on the tarmac until the youngster gets worried and calls the local cops. And when Troopers Ennis Rafferty and Curtis Wilcox check the car over, they realise the whole thing is impossible.

‘It’s got a radiator, but so far as I can tell there’s nothing inside it. No water and no antifreeze. There’s no fanbelt, which makes sense, because there’s no fan.’

‘Oil?’

‘There’s a crankcase and a dipstick, but there’s no markings on the stick. There’s a battery, a Delco, but Ennis, dig this, it’s not hooked up to anything. There are no battery cables.’

‘You’re describing a car that couldn’t possibly run,’ said Ennis flatly.

From a Buick 8, 52

There’s a lot more than this that’s wrong with the car – and after Ennis mysteriously disappears, the vehicle becomes the hidden secret of the police barracks in Statler, PA – shut away in Shed B and unwillingly protected by the fascinated yet instinctively repelled men and women of Troop D, who have no way of explaining or disposing of the monster they guard. Gradually it becomes clear that the Buick is itself a portal. It does weird things, generates blinding lightstorms: here, Sandy, one of the patrolmen, witnesses one:

[T]he whole world went purple-white. His first thought was that, clear sky overhead or no, he had been struck by lightning. Then he saw Shed B lit up like…