Katherine Langrish's Blog

September 8, 2025

The Silver Apples of the Moon, the Golden Apples of the Sun

This is our apple tree, so laden with fruit this year that a massive branch actually cracked in the wind one night and broke off under the weight, as though taking Keats’ lines from Ode to Autumn far too literally –

To bend with apples the mossed cottage-treesAnd fill all fruit with ripeness to the core…

The lawn is still almost ankle deep in windfalls.

What is it about apples? Why are they so evocative? Why was the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – not actually named in the Bible – assumed to be an apple? Why did the Firebird, in Russian folklore, steal golden apples from the garden of the Czar? Why did golden apples of immortality grow in the Garden of the Hesperides, why was the Norse goddess Idun the keeper of golden apples which preserved the youth of the gods? Why was the Apple of Discord – with its inscription To the Fairest – an apple, and why were three golden apples so irresistible to Atalanta that she paused to pick them up and lost her race? (Mind you, that dress she's wearing wouldn't help.)

As the fruit of immortality, or perhaps equally of death, the apple appears as a symbol in Celtic mythology too. Heralds from the Land of Youth might bear a silver apple branch bearing silver blossoms and golden fruit, whose tinkling music lulled the hearers to sleep – perhaps to everlasting sleep. Arthur, after his final battle, went to the island of Avalon, island of apples, to be healed of his mortal wound. Then of course there’s the apple given by the wicked Queen to Snow-White, one bite of which sends the little princess into a death-like sleep.

Apples are tokens of love and promises of eternity. In Yeats' ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’, the lovelorn Aengus seeks forever the beautiful girl from the hazel wood.

Though I am old with wanderingThrough hollow lands and hilly landsI find out where she has gone,And kiss her lips and take her hands;And walk among long dappled grassAnd pluck till time and times are done,The silver apples of the moon,The golden apples of the sun.

But such an eternity is probably also the land beyond death.

Where do apples even come from, why are they so ubiquitous? Why, even today, are so many varieties available even in supermarkets, usually the home of homogeneity? I went into our local Sainsburys one day and counted eleven different named varieties of apple all on sale at once: Empire, Royal Gala, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Cox’s Orange Pippin, Russets, Granny Smiths, Pink Ladies, Jazz, Braeburns and Bramleys. By contrast, there were just four named varieties of pears – and everything else was generic: bananas, strawberries, oranges etc.

Apples are related to roses, I’m delighted to tell you. According to a rather lovely book called ‘Apples: the story of the fruit of temptation’ by Frank Browning (Penguin 1998):

‘In the beginning there were roses. Small flowers of five white petals opened on low, thorny stems, scattered across the earth in the pastures of the dinosaurs, about eighty million years ago. …These bitter-fruited bushes, among the first flowering plants on earth, emerged as the vast Rosaceae family and from them came most of the fruits human beings eat today: apples, pears, plums, quinces, even peaches, cherries, strawberries, raspberries and blackberries.

‘The apple [paleobotanists believe]… was the unlikely child of an extra-conjugal affair between a primitive plum from the rose family and a wayward flower with white and yellow blossoms of the Spirea family, called meadowsweet.’

Isn’t that wonderful? Apples originated in the mountains of Central Asia, where they still grow in many different varieties, and from there they were carried along the Silk Road to Europe. The Pharoahs grew them, the Greeks and the Romans grew them. And they keep. You can store apples overwinter, eat them months after you’ve picked them: fresh fruit in hard cold weather when there’s nothing growing outside. So perhaps you would think of them as life-giving, immortal fruit. They smell fragrant. They feel good too: hard-fleshed, smooth, a cool weight in the hand.

The medieval lyric 'Adam lay y-bounden' provocatively celebrates the Fall of Man when Adam ate the forbidden fruit:

And all was for an appilAn appil that he tokeAs clerkes findenWritten in her boke.

It ends on the mischievously subversive thought that if Adam had not eaten the apple, Our Lady would never have become the Heavenly Queen:

Blessed be the timeThat appil take was!Therefore we maun singen:Deo gratias.

Here is a poem by John Drinkwater (surely the most poetically-named poet ever!) which captures some of those mystical coincidences of apples, eternity, sleep, moonlight, magic and death.

MOONLIT APPLES

At the top of the house the apples are laid in rows,And the skylight lets the moonlight in, and thoseApples are deep-sea apples of green. There goesA cloud on the moon in the autumn night.

A mouse in the wainscot scratches, and scratches, and thenThere is no sound at the top of the house of menOr mice; and the cloud is blown, and the moon againDapples the apples with deep-sea light.

They are lying in rows there, under the gloomy beamsOn the sagging floor; they gather the silver streamsOut of the moon, those moonlit apples of dreamsAnd quiet is the steep stair under.

In the corridors under there is nothing but sleep.And stiller than ever on orchard boughs they keepTryst with the moon, and deep is the silence, deepOn moon-washed apples of wonder.

Picture credits:

Apple tree: Author's gardenAtalanta racing Hippomenes: Willen van Herp, c1650Silver Apples: Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

Adam and Eve: Lucas Cranach, 1537Apple Tree: Arthur Rackham

Labels: Apple of discord, Apples, Eden, Forbidden fruit, John Drinkwater, Katherine Langrish, Keats, Tree of Knowledge, Yeats

July 17, 2025

The Princess as Role Model

A guest post by Gwyneth Jones

I’ve always been attracted to fairytales. I knew I was a storyteller long before I knew I’d be a writer: I took on my father’s mantle, and told epic bedtime stories to my brother and sister, at an early age, and my father’s stories (also epic, endless episodes from the same saga, about the same characters) were all based on a traditional tale, the one about a girl who finds out that she once had seven brothers, who were banished and turned into crows when she was born. It has many variants, but from internal evidence the original must be the Moroccan one, The Girl Who Banished Seven. Naturally, she sets off to find them and rescue them from the enchantment. That’s typical of a fairytale princess (she’s one of those who becomes a princess by marriage, but it’s all the same to me). They do the right thing. They stand up to evil step-mothers, and no task is impossible...

As a child I was small, podgy, clumsy and, worst of all, I was obviously going to pass that dreaded public exam called “The 11 Plus” and go to Grammar School. I felt for the princesses in the fairy tales. First they tell you you’ve been awarded fairy gifts (which you never asked for) and then wham, you’re plunged into bizarre vindictive hardship. Your mother dies, you end up sleeping in the ashes, washing bloody linen in a cave, knitting nettle shirts on a bonfire, wearing out your iron boots over razor sharp glass mountains. But I admired them too, and found them a tremendous comfort. They were so tough, so resourceful, and so decent. When everyone (not least the other little girls I knew) was telling me you are second-rate, they made me proud to be a girl. As I nursed my little bullied self home from school, by the most unobtrusive route, I thought about Cinderella. Elle s’estoit bien, says Perrault, and I wanted to be that person. To behave well, to stand up and be proud. (I knew it worked, too. The best way to frustrate a bully is to stay cheerful; be nice. It drives them absolutely nuts.)

When I was a child I responded to the bizarre adventures, the cheerful feats of endurance, the unstoppable can-do attitude of those privileged, yet beleaguered, young women. As I grew up the stories grew with me. I realised that the princess complex is a trap, it’s pure social propaganda. But I still loved the princesses, and the princes themselves, and honoured their traditions when I started writing my own fantasy stories, published, long afterwards, as Seven Tales And A Fable. I honoured the stories and I still do. I saw that they were more than lessons in docility, more than comforting, greedy daydreams. They were beautiful, ancient vessels, full of buried treasure. It was a very old, profound and lovely princess-story, re-written as a fantasy novel by a modern writer —'Till We Have Faces', C.S. Lewis— that inspired me to write 'Snakehead', my own re-imagining of the story of Perseus and Andromeda.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.'Till We Have Faces' is based on Eros and Psyche, one of the greatest of the Greek myths, and yet the story is familiar from many fairy tales. A princess finds her prince and loses him. She fights her way back to his side by overcoming the fiendish magical challenges devised by a spiteful royal mother-in-law—

Seven long years I served for thee

The glassy hill I clamb for thee

The bluidy shirt I wrang for thee

Wilt thou not wake and turn to me?

(The Black Bull Of Norroway)

Perseus and Andromeda is another myth, perhaps the greatest of them all, with instant popular appeal. The hero-tale of Perseus fits in anywhere! There’s this kid, you see, brought up by his single mother, goes to High School or whatever, and then one day some supernatural beings come along. They tell him his father was a Greek God, they give him a magic sword and flying sandals, they send him off to kill a terrifying monster. He’s tall, strong and handsome! He has superpowers! He’s a teen with a mission! Oh, hey, and there’s a flying horse—

Unexpectedly, things get even better if you’re looking to write a novel rather than a comic book. The story of Perseus has complexity, it has texture. There’s the grim soap-opera of his parentage —why Danae of the shower of gold was locked up; how Zeus, the ruthless, randy chief of the Olympians, just couldn’t resist a challenge; how Perseus’s charming grandfather put both mother and child in a box and had them thrown into the sea. There’s the unconventional little family group on the island of Seriphos: Danae and her son, washed up on the shore, living under the protection of Dictys the fisherman. Whose brother is the island’s tyrant king.

Imagine this boy, knowing he’s different, but with nothing to show for it, no rank, no riches. Imagine him finding out that his biological father (he’s not impressed by divine status, of course; he’s family himself) is a ruthless Mr Big who raped his mother. He knows he’s been protected at least once from certain death. He must be wondering, as he grows up, what his selfish brute of a Divine Father saved him for. Nothing good, you can bet... And then there’s Dictys. Imagine the boy’s relationship with the fisherman, who has brought him up, and never (not in any of the accounts) put a disrespectful move on Danae. He’s been a true father. Dictys seems to be a man of peace, since he’s able to live and let live, with his wicked brother on the throne. How is his adopted son really going to feel, when the Messenger of the Gods, and the Goddess Athini waylay him on the road, and tell him he has to chop off the Gorgon’s Head? This Gorgon who was once a woman, too beautiful for her own good, like Danae. Who was turned into a monster, to punish her for having been raped...

So it goes on, a wonderful story: the work of many hands, over thousands of years, and yet still alive, still growing, still inviting new storytellers to weave new patterns into the web. There’s only one weak point, and that’s the traditional centrepiece, where our hero finds his true princess, and has to win her by beating a string of awful vindictive challenges, thrown down by the malign Gods—

It’s weak because it doesn’t happen.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.Andromeda isn’t a character. She’s not even as much of a character as the prince in 'The Black Bull Of Norroway'. She’s a name, and a predicament. Perseus doesn’t struggle to win her. He just passes by, on the way home from his questing work, swinging the Gorgon’s Head by the hair (not very safe! But that’s how it looks in all the pictures), and picks up a half-naked princess; like a pizza or a sandwich.

In my opinion, this just won't do!

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.In 'Till We Have Faces' C.S. Lewis keeps his distance from the two principals who represent, without much disguise, the human soul and the God of Love. His characters are the lesser figures. His protagonist is one of Psyche’s jealous sisters —a woman who barely exists in the original narrative. In 'Snakehead', I took the liberty of inventing the character of Andromeda, a weaver and a scholar (her name means Ruler of Men, or else Thinker) and switched things around so that she and Perseus have some previous history, before Andromeda is chained to the rock; before Perseus wanders along to slay the dragon. It just makes more sense, if Perseus knows he’s coming to the rescue of a princess; if he intends to claim her hand in marriage. It makes more sense to me personally, too. A generation ago, great writers and editors like Jane Yolen, Ellen Datlow reclaimed the traditional heritage: dismissing soft-focus, Disneyfied Snow White and Cinderella, rediscovering grim truths and quick-witted, resourceful heroines. That’s fine, that’s excellent work. But what I’ve wanted to do is to reclaim the relationships. To bring the prince and the princess together, instead of sending them off on segregated initiation trials. To let them meet as human beings, as friends, and fight side by side.

The story on record says Andromeda had to be sacrificed to punish her mother, queen Cassiopeia —who had boasted that her daughter was more lovely than a sea-nymph, and thus offended Poseidon, the God of Ocean and of Earthquakes. I don’t believe it. Child sacrifice was absolutely rife, around the shores of the Ancient Mediterranean. (Take a closer look at your Old Testament if you don’t believe me). I’ll bet you anything it wasn’t a one-off occasion. I bet there was a lottery, and the children of the rich were usually spared, but then the queen’s political opponents decided Andromeda’s number was up. A powerful woman like Cassiopeia could have been an annoying relic of the old ways, in the days of the original story —when the Mediterranean World was leaving female-ordered civilisation behind, and patriarchal tribal rule was taking over.What would a princess do, if she found out she’d been drafted? Run for it, of course. And then what would she do, if she was a real princess; and knew some other poor girl would have to die in her place? She’d run back, of course. No matter who tried to stop her, no matter if she’d fallen in love.

Leaving Perseus with his repellent, murderous quest: a terrible choice, and just the inklings of a desperate plan—

The story of Perseus and Andromeda is the story of the founders of Homer’s Mycenae: well built Mycenae, rich in gold... way back in the Bronze Age. And from Mycenae, the baton was handed on to Athens, the cradle of western civilisation; making them a fairly significant couple, in the scheme of human history. (And by the way, Perseus and Andromeda did live happily ever after, which makes them unique among pairs of lovers featured in the Greek Myths) But is that all? The deeper I looked into the history of the Medusa, terrible to look upon, snake-haired monster - and into the history of the mighty Goddess Athini, whose name means Mind, the more they seemed to reflect each other. As if Medusa and Mind were the two faces of one truth—

Did I catch a glimpse of the original, brilliant storyteller, telling me something timeless and profound? About that mysterious birthright gift, first freely given and then painfully earned, that lies at the heart of fairy tale? Maybe, maybe not. I don’t know. I’m just a storyteller, seeing pictures in the fire. Pictures that, now as then, sometimes seem playful, sometimes serious, and sometimes seem to tell me eternal things.

Gwyneth Jones is a brilliant writer of adult science fiction. ‘Bold As Love’ which won the Arthur C Clarke Award in 2002, is the first of a series of five books about a near-future Britain where society is in meltdown. There’s a violent environmental movement, an Islamist uprising in the north, a subtle but nasty dose of black magic and a complex relationship between the main characters – three charismatic, damaged and idealistic young rock stars who become the country’s reluctant saviours and leaders of a new government, the 'Rock and Roll Reich'. The books are rich in romance, horror, and a deeply felt version of British landscape, history and myth.

Under the name Ann Halam, Gwyneth has also written YA fantasy, science fiction and horror. I’ve talked on this blog about ‘King Death’s Garden’, a ghost story which is funny as well as very frightening. Siberia’ is a haunting, beautiful book about a girl who journeys across a frozen repressive land carrying a ‘nut’ full of mysterious secret seeds. And Snakehead’ is an absolutely womderful retelling of the legend of Perseus and Andromeda.

Picture credits:

Princess on Rock with Dragon: Arthur Rackham, Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. 1909

Perseus and Andromeda: a wall painting from Pompei, The National Museum of Naples.

Perseus and Andromeda: by Ingres

Perseus and Andromeda by Edward Burne-Jones

June 28, 2025

Time and the Hour

In the middle of the small room, under a low-hanging, glass-shaded light, was Uncle Bill's wooden worktable, covered in small, intricate, shining parts - cogs and springs and watch-cases. Those he wasn't currently working on would be protected from the dust by a collection of upturned crystal sherry-glasses whose stems had snapped. Everything gleamed.

We always tried to arrive just before noon. Bill would welcome us and we would all crowd into his workshop, adults and children alike, and wait, breathless and smiling. There would be a strange whirring. Then the first shy chime. And then one after another every working clock in the room would clear its throat and strike. Ding, ding, ding - dong, dong - bing, bing, bing - cuckoo, cuckoo - interrupting one another in a delightful, clashing crescendo and diminuendo of shrill and rapid and slow and mellow, till finally the last cuckoo ducked back in as the little doors whipped shut, and all that would be left was the constant tick-tick-ticking. It was something that could never fail to give pleasure.

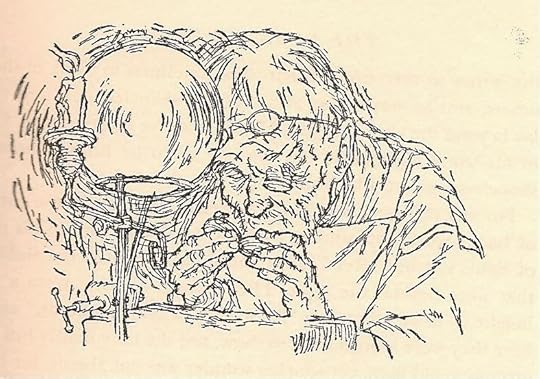

Isaac Peabody - illustration by A.R. Whitear

Isaac Peabody - illustration by A.R. WhitearUncle Bill's clock room often used to remind me of Isaac Peabody's workshop in Elizabeth Goudge's novel 'The Dean's Watch' which is set in the 1870s in an unnamed fictional cathedral city which combines elements of both Wells and Ely. Isaac is described as 'a round-shouldered little man with large feet and a great domed and wrinkled forehead. ...His eyes were very blue beneath their shaggy eyebrows and chronic indigestion had reddened the tip of his button nose. His hands were red, shiny and knobbly, but steady and deft.' As for his workshop:

The shop was so small and its bow window so crowded with clocks, all of them ticking, that the noise was almost deafening. It sounded like thousands of crickets chirping or bees buzzing, and was to Isaac the most satisfying sound in the world.

But old Isaac has a secret. Brought up by a stern father in the fear of an angry God, he is terrified of the great cathedral, and even though he is fascinated by the Jaccomarchiadus (the mechanically-operated figure that strikes a bell on the outside of a clock) which adorns its tower, he is too afraid ever to go inside the cathedral and see the clock for himself:

The Jaccomarchiardus stood high in an alcove on the tower, not like most Jacks an anonymous figure, but Michael the Archangel himself. He was lifesize and stood upright with spread wings... Below him, let into the wall, was a simple large dial with an hour hand only. Within the Cathedral, Isaac had been told there was a second clock with above it a platform where Michael on horseback fought with the dragon at each hour and conquered him. But not even his longing to see this smaller Michael could drag Isaac inside the terrible Cathedral. No one could understand his fear. He could not entirely understand it himself.

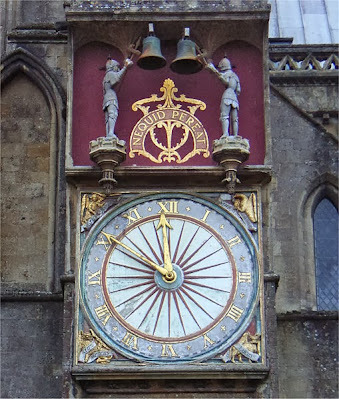

Perhaps not. But here is the dial on the outside north wall of Wells cathedral, and here - below - is the west entrance, and I think you can see that there is, or could be, something awe-inspiring, even terrible, about its beauty. You might well feel a bit of an ant, approaching it as Isaac does through the small streets of his anonymous city: 'Like a fly crawling up a wall Isaac crawled up Angel Lane, scuttled across Worship Street, cowered beneath the Porta, got himself somehow across the moonlit expanse of the Cathedral green and then slowly mounted the flight of worn steps that led to the west door...'

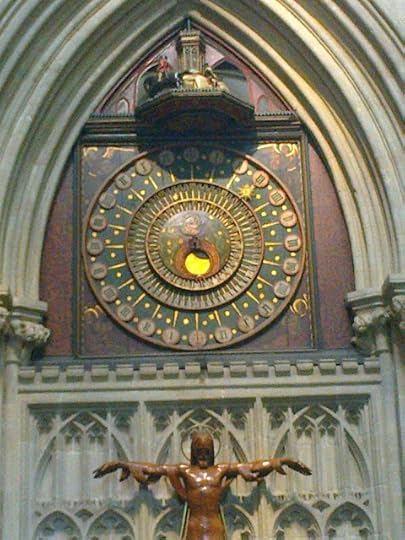

Eventually, right at the end of the book, Isaac does manage to conquer his fear and enter the cathedral. And there it is, the other clock.

It was just as it had been described to him. Above the beautiful gilded clock face, with winged angels in the spandrels, was a canopied platform. To one side of it, Michael in gold armour sat his white horse, his lance in rest and his visor down. On the other side the dragon's head, blue and green with a crimson forked tongue, rose wickedly from a heap of scaly coils. They waited only for the striking of the bell to have at one another. It was a wonderful bit of work. ...And to think he had lived in the city all these years and had not seen it!

Here is the one at Wells. It dates to the late 14th century. Around the dial you may just be able to make out the four angels in the corners, who hold the four cardinal winds.

On the hour, every hour, armoured knights ride around the platform you can see at the top, jousting with one another, while higher up the wall to one side, the Jack perches in his alcove, striking his bell.

On the hour, every hour, armoured knights ride around the platform you can see at the top, jousting with one another, while higher up the wall to one side, the Jack perches in his alcove, striking his bell.

After I had taken these pictures, one of the cathedral clergy came out and spoke to the gathered onlookers. He didn't preach, not in a specifically Christian way, but he did ask us to consider the value of time in our lives, and to make good use of it. It was a suitable message. In Goudge's book, old Isaac makes friends with the great Dean of the cathedral, whose clocks he comes to wind. The Dean is a sick man, who knows he has not long to live. He pays a visit to the clock-shop and listens to Isaac talking about horology:

He delighted in Isaac's lucid explanations and he delighted too in this experience of being shut in with all these ticking clocks. The sheltered lamplit shop was like the inside of a hive full of amiable bees. ... [The clocks] spoke to him with their honeyed tongues of this mystery of time, that they had a little tamed for men with their hands and voices and the the beat of their constant hearts and yet could never make less mysterious or dreadful for all their friendliness. How strange it was, thought the Dean, as one after another he took their busy little bodies into his hands, that soon he would know more about the mystery than they did themselves.

Dear Uncle Bill was nothing like poor frightened Isaac, but a truly happy man and faithful Catholic who willed his best and favourite clock, the massive black grandfather which stood in his living room, to the Catholic Bishop of Salford. It was a typical gesture which I hope the Bishop appreciated, but I expect he did, as - just as Isaac does for the Dean - Bill used to go regularly to wind the Bishop's clocks. Bill used to joke sometimes, that he didn't know what he'd do in heaven. "I don't know what I'll do in heaven," he'd say in his soft Manchester accent, with a twinkle in his eye. "There's no clocks there!" He died at the age of ninety-plus, contented to the last, and would have both enjoyed and deserved the genuine epitaph that Elizabeth Goudge quotes at the beginning of 'The Dean's Watch':

Epitaph from Lydford Churchyard

Here lies in a horizontalpositionThe outside case ofGeorge Routleigh, Watchmaker,Whose abilities in that linewere an honourTo his profession:Integrity was the main-spring,And prudence the regulatorOf all the actions of hislife:Humane, generous and liberal,His hand never stoppedTill he had relieved distress;So nicely regulated wereall his movementsThat he never went wrongExcept when set-a-goingBy peopleWho did not know his key;Even then, he was easilySet right again:He had the art of disposing ofhis timeSo wellThat his hours glidedawayIn one continual roundOf pleasure and delight,Till an unlucky minute put a periodtoHis existence;He departed this lifeNovember 14, 1802,aged 57, Wound up, in hopes of being taken in handBy his Maker,And of beingThoroughly cleaned, repairedand set-a-goingIn the World to come.

June 17, 2025

Alice, Creator and Destroyer

I once read, I think in an essay by C.S. Lewis – that to have weird or unusual protagonists in a fantasy world was gilding the lily. Simply too much icing on a very fancy cake. And then he cited Alice as a good example of an ordinary child to whom strange things happen. I’m not sure he was right.

Of course it’s true that many heroes and heroines in classic 20th century fantasy are ‘ordinary’ – hobbits, for example; and Lewis’s own Pevensie children, and Alan Garner’s Colin and Susan in ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ and ‘The Moon of Gomrath’. There’s a pleasure in seeing an ordinary person rise to the occasion, as when Bilbo Baggins turns out to be a very good burglar indeed, or when Frodo self-sacrificingly takes on the burden of the Ring. Tolkien must have seen many instances of ‘ordinary’ heroism in the trenches of World War I.

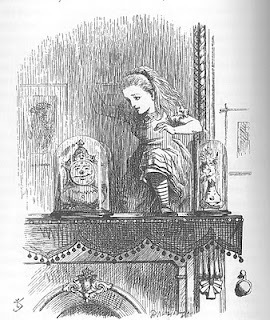

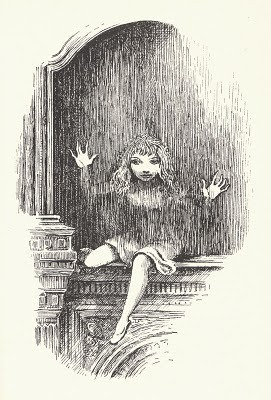

And I’d agree that one does need to able to identify with characters in fantasy. For me, one of the difficulties of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy is that apart from Titus and Fuschia there are too few characters for whom one can feel any empathy. Although I love the setting and the descriptions of the immense castle and its strange ritual life, I become emotionally exhausted by Peake’s cast of grotesques. Peake had, it’s fair to say, a line on the darker side of life. And not coincidentally for this post, he illustrated the two Alice books. Just look at his picture of Alice emerging out of the mirror into Looking-Glass Land, and compare it with Tenniel’s.

Tenniel’s Alice is barely halfway through the mirror. She looks not at us, but around and down at the room with an expression of calm interest. She is a little excited, perhaps, but not alarmed. We don’t feel there in the room waiting for her: instead, we are looking through the window of the picture. We can glimpse part of the room. The grinning clock is strange but not threatening. The room itself appears to be well lit. In Tenniel’s drawing, Alice is firmly planted on the mantelshelf. She has a chance to look around, and will jump down when she chooses.

Tenniel’s Alice is barely halfway through the mirror. She looks not at us, but around and down at the room with an expression of calm interest. She is a little excited, perhaps, but not alarmed. We don’t feel there in the room waiting for her: instead, we are looking through the window of the picture. We can glimpse part of the room. The grinning clock is strange but not threatening. The room itself appears to be well lit. In Tenniel’s drawing, Alice is firmly planted on the mantelshelf. She has a chance to look around, and will jump down when she chooses. Peake’s Alice appears through the misty glass like an apparition. She looks straight into our eyes, as if we are the first thing she sees. Her face is very white, and so are her hands, outspread as if pressing through the glass, but also gesturing an ambiguous mixture of alarm and conjuration. She is coming out of darkness, and there are no reflections to suggest what the looking glass room may contain – except us, for we are already there, waiting for her. (We may not be friendly). With one leg waving over the drop, she is about to fall off the mantelshelf into the room – for her position is precarious.

Peake’s Alice appears through the misty glass like an apparition. She looks straight into our eyes, as if we are the first thing she sees. Her face is very white, and so are her hands, outspread as if pressing through the glass, but also gesturing an ambiguous mixture of alarm and conjuration. She is coming out of darkness, and there are no reflections to suggest what the looking glass room may contain – except us, for we are already there, waiting for her. (We may not be friendly). With one leg waving over the drop, she is about to fall off the mantelshelf into the room – for her position is precarious.Even the 1951 Disney cartoon recognised the tough element in Alice’s character, and the latent terror in Wonderland. They made her into a prim little cutie, but she still managed to stand up to the frightening Queen of Hearts and the Mad Hatter.

So how ordinary is Alice, after all – is she really just an innocent and rather pedestrian Every-little-girl in a mad, mad world? Or does she have her own brand of illogical weirdness with which to combat the weirdness she finds? I think she does, and I think modern readers often miss it. We look at the blonde hair, the hairband, the blue dress and the white pinafore, and forget her speculative, inventive mind, her impatience – and passages like this:

And once she had really frightened her old nurse by shouting suddenly in her ear, “Nurse! Do let’s pretend that I’m a hungry hyaena, and you’re a bone!”

Compare that with George MacDonald’s heroine in ‘The Princess and The Goblin’. Can you imagine Princess Irene doing anything so bizarre? Irene is truthful and brave, but always a little lady – the Victorian gentleman’s ideal child. The adventures that happen to Irene are not of her own creation. But it’s Alice’s weird imaginings about what might be happening on the other side of the glass – that take her into Looking Glass Land at all. Alice is both a credibly strong-minded little girl – capable of losing her temper, of defending herself in the White Rabbit’s house by kicking Bill the lizard up the chimney – and a surreal philosopher, as some children are. She is the maker of her own imaginary worlds and when they get too chaotic, she ends them – amid considerable violence.

“Who cares for you?” said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time) “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!” At this the whole pack rose up into the air and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off…

(Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland)

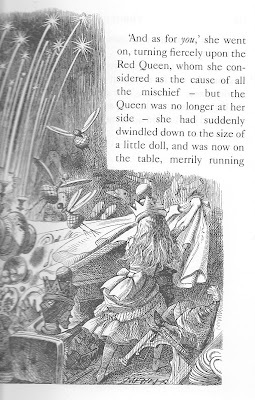

“I can’t stand this any longer!” she cried as she jumped up and seized the tablecloth with both hands: one good pull, and plates, dishes, guests and candles came crashing down together in a heap on the floor. “And as for you,” she went on, turning fiercely upon the Red Queen… “I’ll shake you into a kitten, that I will!”

“I can’t stand this any longer!” she cried as she jumped up and seized the tablecloth with both hands: one good pull, and plates, dishes, guests and candles came crashing down together in a heap on the floor. “And as for you,” she went on, turning fiercely upon the Red Queen… “I’ll shake you into a kitten, that I will!” (Alice’s Adventures Through the Looking Glass)

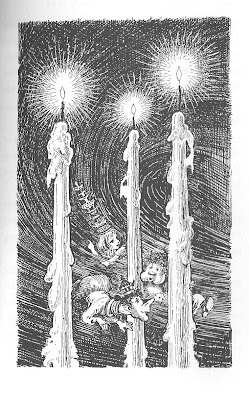

Tenniel’s illustrations catch the vivid threat and drama of the situation. In Peake's, lit by three tall sinister candles, it looks as if Alice and the two Queens are being sucked into a black hole.

Tenniel’s illustrations catch the vivid threat and drama of the situation. In Peake's, lit by three tall sinister candles, it looks as if Alice and the two Queens are being sucked into a black hole. Some books with dream endings can feel like a cheat. ‘And she woke up, and it was only a dream’ seems to negate all that has happened. But in the case of Alice, the dream settings are absolutely necessary. She has not strayed into a pre-existing Narnia like Lucy Pevensie. She is the Alpha and Omega of her own fantasylands. She is, like dreaming Brahma, the creator and destroyer of worlds: and when she awakens from her dreams, it is utterly logical that Wonderland and Looking Glass Land will cease to be.

March 30, 2025

The Woman in the Kitchen

It's Mothering Sunday in England this weekend, and here is a drawing I made for my junior school teacher a very long time ago. We'd been asked to draw a picture of our kitchens. I don't remember if a portrait of one's mother was also required, but she was there (of course) and so I included her. I was ten and very proud of the likeness, although I remember her saying to me, 'Hmm, do you really think I look like that?'

Anyone who grew up in the 1960s and 70's will recognise this kitchen. There's the speckled red lino on the floor, with the rubbery seal stuck down over the join. There are the painted wooden cupboards, the wire rack over the oven, the aluminium pans, the wall-hooks from which to hang sieves and scissors and fish-slices, above all the state-of-the-art glass disc in the window, with cords you pulled to line up the ventilation holes. There's my mother's curled hair (she used rollers), the fact that she's wearing a dress, her heeled court shoes.

Truth to tell, perhaps this isn't such a good likeness of my mother, who was slim and attractive... but it's a pretty good record of our kitchen. If you opened the back door to the right, six stone steps would lead you down into a slanting asphalt yard and the back gate. If you rubbed the steam from the kitchen window, you could look right over the valley to the moors on the other side of Wharfedale.

As I write this, my mother is 91 and has been in hospital for weeks, having fallen and broken her hip. She isn't very well. What you can't see in this drawing I made - but perhaps it's implicit - is the love in that room. It was a happy, happy home, and she made it so. No amount of trouble I go to now can be too much to repay her for what she gave us.

Last autumn around the time of my birthday, my sister and I were poking around in one of those fascinating antiques arcades where you can find anything and everything from Lalique glass so expensive it isn't even priced (if you have to ask, you can't afford it) to chipped jugs and odd sherry glasses at 50 pence apiece. My sister had asked me to choose a birthday present. I looked at this and that, and then I found this anonymous watercolour.

I had to have it. This is my ten-year old picture, grown-up and made better. This is or might as well be, my mother in one or any of the places we lived during my childhood. All that's wanting is some sign of the menagerie of cats, dogs, ducks, white mice etc, which went with us everywhere.

There is and was a lot more to my mother than housework (which she didn't much like). She sang in a wonderful, trained contralto voice, she wrote poetry, created wonderful gardens, had and has wit, spirit, a sense of humour and the most beautiful smile. She was practical, too. I remember her with a blowtorch and scraper, stripping brown varnish off the bannisters. Once she rehung a sash window. But the housework was always there, part of life, part of every home. These old-fashioned kitchens are part of my memories. There she is, the woman in the kitchen, washing the dishes, peeling the potatoes.

I want her to come home.

March 13, 2025

River Voices

RIVER VOICES

As I walked down by the river

Close by the sounding sea,

Up rose three water maidens

Who stretched white arms to me,

‘Comehere, you lilting stranger

Whowhistles as sharp as tin,

We’llgive you a bed, a crown for your head,

Andour hair to wrap you in.’

‘No thanks, my jacket’s good enough,

And my old black tarpaulin.’

Then ups the old green river-man,

‘Come Jerry my boy,’ says he,

‘There’s room for a bold young chaplike you

Under the water free.

I’llmake you lord of the river,

Walkingon silver sand,

Fineliquor you’ll sup from a golden cup,

Andthe fishes will kiss your hand.’

Says I, ‘Your advice is mightynice,

But I reckon I’ll stay on land.’

The last of all to surface

Was my lost love Nancy Gray,

She was wearing the ring I gave to her

A year last quarter day.

Hersmile was bright as sunshine

Inspite of the tears she wept,

Withan infant pressed against her breast

Thatlooked as though it slept –

‘Leap in my lad, be no more sad...’

So I looked at her, and leapt.

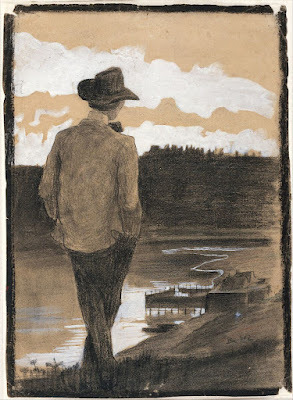

© Katherine Langrish 2025

Young Man on a Riverbank, Umberto Bocciano 1902, public domain:

February 26, 2025

The Ghost that spoke Gaelic

'An Incident at the Battle of Culloden' by David Morier, oil on canvas.

'An Incident at the Battle of Culloden' by David Morier, oil on canvas.

This post first appeared on The History Girls blog

Scotland, 1749: just four years after the failed Jacobite rising and the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the clans at the Battle of Culloden. Reprisals had been severe; the wearing of kilt and tartan was forbidden; the rising was still fresh and sore in everyone’s minds and by no means necessarily still over. Messages (and money) flew between the Prince in exile and his loyal supporter Cluny MacPherson, in hiding on Ben Alder.

Into this volatile, still smouldering arena marched, in the summer of 1749, the newly married – and it has to be said, utterly and foolishlynaïve – Sergeant Arthur Davies of ‘Guise’s Regiment’, heading over the mountains from Aberdeen to Dunrach in Braemar in charge of a patrol of eight private soldiers, for no more interesting purpose than to keep a general eye on the countryside.

This kind of countryside...

Sergeant Davies was a fine figure of a man, expensively but not at all sensibly dressed, considering what he was about. He carried on him a green silk purse containing his savings of fifteen and a half guineas; he wore a silver watch and two gold rings. There were silver buckles on his brogues, two dozen silver buttons on his striped ‘lute string’ waistcoat; he had a silk ribbon to tie his hair, and he wore a silver-laced hat. Thus attired he said goodbye to his wife – who never saw him again – and set off, encountering on the way one John Growar in Glenclunie, whom he told off for carrying a tartan coat. Shortly after this, the over-confident Sergeant left his men and went off over the hill, alone –to try and shoot a stag...

And he ‘vanished as if the fairies had taken him’. His men and his captain searched for four days, while rumours ran wild about the countryside that Davies had been killed by Duncan Clerk and Alexander Bain Macdonald. But no body was found…

Until the following year, in June 1750, a shepherd called Alexander MacPherson came to visit Donald Farquharson, the son of the man with whom Sergeant Davies had been lodging before his death. MacPherson, who was living in a shepherd’s hut or shieling up on the hills, complained that he ‘was greatly troubled by the ghost of Sergeant Davies’ who had appeared to him as a man dressed in blue and shown MacPherson where his bones lay. The ghost had also named and denounced his murderers – in fluent Gaelic, of which, in life, Sergeant Davies had of course not spoken a word… Farquharson accompanied MacPherson, and the bones were duly found in a peat-moss, about half a mile from the road the patrol had used, minus silver buckles and articles of value. The two men buried the bones on the spot where they lay, and kept quiet about it.

Of course, the story spread. Nevertheless it was not till three years later, in 1753, that Duncan Clerk and Alexander Bain Macdonald were arrested for the Sergeant’s murder on the testimony of his ghost. At the trial Isobel MacHardie who had shared shepherd MacPherson’s shieling during the summer of the ghost, swore that ‘she saw something naked come in at the door which frighted her so much she drew the clothes over her head. That when it appeared, it came in a bowing posture, and that next morning she asked MacPherson what it was, and he replied not to be afeared, it would not trouble them any more.’

Apart from the ghostly testimony, there was plenty of circumstantial evidence to convict the murderers. Clerk’s wife had been seen wearing Davies’ ring; after the murder Clerk had become suddenly rich. And a number of the Camerons later claimed to have witnessed the murder itself, at sunset, from a hollow on top of the hill: they never volunteered an explanation of what they themselves had been doing up there – doubtless engaged in the illicit business of smuggling gold from Cluny to the Prince.

Things looked black for the accused murderers. Yet a jury of Edinburgh tradesmen, moved by the sarcastic jokes of the defence, acquitted the prisoners. They could not take the ghost story seriously - not necessarily because it was a ghost: scepticism was on the rise, but ordinary people were still superstitious and the last Scottish prosecution for witchcraft had been only in 1727. But they could not believe in a ghost which had managed to learn Gaelic.

Andrew Lang, in whose ‘Book of Dreams and Ghosts’ I cameacross this tale, adds a postscript sent to him by a friend: the words of anold lady, ‘a native of Braemar’, who ‘left the district when about twenty yearsold and who has never been back’. Lang’s friend had asked her whether she hadever heard anything about the Sergeant’s murder, and when she denied it, hetold her the story as it was known to him. When he had finished she broke out:

“That isn’t the way of it at all,for… a forebear of my own saw it. He had gone out to try and get a stag, andhad his gun and a deerhound with him. He saw the men on the hill doingsomething, and thinking they had got a deer, he went towards them. When he gotnear them, the hound began to run on in front of him, and at that minute he sawwhat it was they had. He called to the dog, and turned to run away, butsaw at once he had made a mistake, for he had called their attention tohimself, and a shot was fired after him, which wounded the dog. He then ranhome as fast as he could…”

But at this point, the old lady ‘became conscious she wastelling the story,’ and clammed up. No more could be got out of her.

What a tangled skein of loyalties and hatreds, of secret activities in the heather, of rebellion and politics, of a murder where the whole countryside knew straight away who’d done it, but wouldn’t or dared not say – of a ghost’s evidence, and of poor, foolish Sergeant Davies in the middle of the Highlands, only four years after the ’45, behaving as though it was an adventure playground through which he could strut in his finery and shoot stags...

And how ironic that the very ghost story which brought the murder to light – almost certainly devised by Alexander MacPherson in order to denounce the murderers without bringing unwelcome attention upon himself – seemed so incredible to a Lowlands jury that they would not convict.

Photo credit:

Glen Clunie & Clunie Water, the road from Braemar

© Copyright Nigel Corby

January 26, 2025

Samuel Pepys & FOMO

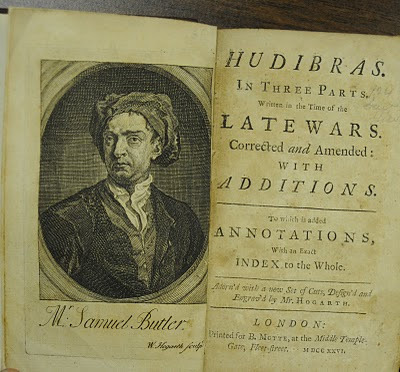

On 26th December 1662, twenty-nine year old Samuel Pepys met his friend Mr Battersby, who recommended ‘a new book of Drollery in verse called Hudibras.’ Eager to keep up with the newest thing, Pepys dashed out and bought the first volume for the considerable sum of two shillings and sixpence. But he was disappointed. ‘When I came to read it, it is so silly an abuse of the Presbyter-Knight going to the wars, that I am ashamed of it; and by and by meeting at Mr Townsend’s at dinner, I sold it to him for 18d’. And that was the loss of a whole shilling!

'Hudibras' is a mock epic by Samuel Butler which makes satirical fun of the Puritans and Presbyterians who had so lately held power in England. It tells of Sir Hudibras, a stupid and arrogant knight-errant on whom the poet lavishes absurd amounts of praise. The book was a huge success, with pirated copies and spurious continuations springing up even before the author could bring out the second and third parts. With Pepys, however, it completely misfired. He failed to see what was so funny about it.

By February 1663 though, Pepys was having second thoughts and rather regretted his decision. Since everyone else praised the book so highly, perhaps he had been too hasty in getting rid of it? Off he went, ‘To a bookseller’s on the Strand and bought Hudibras again, it being certainly some ill humour to be so set against that which all the world cries up to be an example of wit – for which I am resolved once again to read him and see whether I can find it out or no.’

Perhaps buying the book for a second time made him determined to persist, but it didn’t make the task of wading through it any less of a chore. And now he became more cautious. Nine months later, on 28 November, he walked through St Paul’s Churchyard, famous for its bookstalls, ‘and there looked upon the second part of Hudibras; which I buy not, but borrow to read, to see if it be as good as the first, which the world cries so mightily up, though I have tried by twice or three times reading to bring myself to think it witty…’

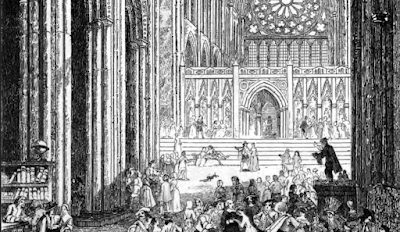

Bookstalls (on the left) within Old St Pauls

Bookstalls (on the left) within Old St PaulsBut borrowing it made no difference either to his opinion of the book or to his obvious desire that – somehow, anyhow – he might learn to like what everyone else liked.

For on December 10th, having decided to spend the immense sum of three pounds upon books, he went back to the booksellers ‘and found myself at a great loss what to choose.’ His real temptation was to buy plays, but he could never quite rid himself of the feeling that plays were somehow rather sinful, so at last… ‘I chose Dr Fuller’s Worthys, the Cabbala or collection of Letters of State – and a little book, Delices de Hollande, with another little book or two, all of good use or serious pleasure, and Hudibras, both parts, the book now in greatest Fashion for drollery, though I cannot, I confess, see enough where the wit lies.’

So by now, Pepys has bought Hudibras three times – even though he simply cannot get on with it. This goes to show how success breeds success, of course. Hands up who bought the latest block-busting thriller just to discover what all the fuss was about?

It would be nice to record that Pepys finally managed to enjoy his purchase, but I fear he never did. At any rate, the last reference he makes to Hudibras is in his diary entry for January 27th, 1664. ‘At noon to the Coffee-house, where I sat with Sir William Petty, who is methinks one of the most rational men that I ever heard speak, having all his notions the most distinct and clear; among other things saying that in all his life these three books were the most esteemed and generally cried up for wit in the world – Religio Medici, Osbourne’s Advice to a Son, and Hudibras.’

And there we are left: Pepys makes no further comment. But can’t you just sense him scratching his head? If, like me, you have ever bought a best-selling novel that everyone seems to praise but which you found impossible to finish – perhaps you will spare him a thought.

August 23, 2024

More about the Billy Blin'

A book called ‘The Remains of Nithsdale andGalloway Song’ edited by R.H. Cromek and published 1810,contains this “Account of Billy Blin'" with some entertaining stories.

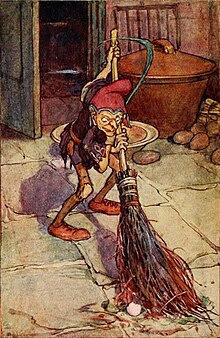

"This is another name for the Scotch Brownies, a class of solitary beings,living in the hollows of trees, and recesses of old ruinous castles. They aredescribed as being small of stature, covered with short curly hair, with brownmatted locks, and a brown mantle which reached to the knee, with a hood of thesame colour. They were particularly attached to families eminent for theirancestry and virtue; and have lived, according to tradition’s ‘undoubted mouth’,for several hundreds of years in the same family, doing the drudgery of amenial servant.

"But though very trustworthy servants, theywere somewhat coy in their manner of doing their work:– when the threaves of corn [this is 25 sheaves gathered in ‘shocks’] were counted out they remained unthrashen[unthreshed];at other times, however great the quantity, it was finished by thecrowing of the first cock. Mellers of corn [grainready to be sent to the mill] would be dried, ground and sifted, with suchexquisite nicety, that the finest flour of the meal could not be found strewedor lost.

"The Brownie would then come into thefarm-hall and stretch itself out by the chimney, sweaty, dusty and fatigued. Itwould take up the pluff – a piece ofbored boar-tree [elder] for blowingup the fire and, stirring out the red embers, turn itself till it was restedand dried. A choice bowl of sweet cream, with combs of honey, was set in anaccessible place:– this was given as its hire; and it was willing to be bribed,though none durst avow the intention of the gift. When offered meat or drink,the Brownie instantly departed, bewailing and lamenting itself, as if unwilling to leave a place so long itshabitation, from which nothing but the superior power of fate could sever it.

"A thrifty good wife, having made a web oflinsey-woolsey, sewed a well-lined mantle and a comfortable hood for her trustyBrownie. She laid it down in one of his favourite haunts and cried to him toarray himself. Being commissioned by the gods to relieve mankind under thedrudgery of original sin, he was forbidden to accept of wages or bribes. Heinstantly departed, bemoaning himself in a rhyme, which tradition hasfaithfully preserved:

Anew mantle and a new hood! –

PoorBrownie! ye’ll ne’er do mair gude.

"The prosperity of the family seemed to dependon them, and was at their disposal. A place called Liethin Hall, inDumfies-shire, was the herefitary dwelling of a noted Brownie. He had livedthere, as he once communicated in confidence to an old woman, for three hundredyears. He appeared only once to each new master, and indeeed seldom shewed morethan his hand to anyone. On the decease of a beloved master, he was heard tomake moan, and would not partake of his wonted delicacies for many days. Theheir of the land arrived from foreign parts and took possession of his father’sinheritance. The faithful Brownie shewed himself and proffered homage. Thespruce Laird was offended to see such a famine-faced, wrinkled domestic, andordered him meat and drink, with a new suit of clean livery. The Browniedeparted, repeating loud and frequently these ruin-boding lines:

Ca’,cuttie, ca!

A’the luck of Liethin Ha’

Gangs wi’ meto Bodsbeck Ha’.

"Liethin Ha’ was, in a few years, in ruins,and ‘bonnie Bodsbeck’ flourished under the luck-bringing patronage of theBrownie.

"They possessed all the adventurous andchivalrous gallantry of crusading knighthood, but in devotion to their ladiesthey left Errantry itself far behind. Their services were really useful. In theaccidental encounters of their fair mistresses with noble outlaws in woods, andprinces in disguise, – when the kindladies had nothing to show for their courtsey but a comb of gold or afillet of hair, – the faithful Brownie restored the noble wooer; laid thelovers on their bridal bed, declared their lineage, and reconciled all parties.He followed his dear mistress through life with the same kindly solicitude;for, when the ‘mother’s trying hour was nigh’, with the most laudablepromptitude he environed her with the ‘cannie dames’ ere the wish for theirassistance was half-formed in her mind.

"One of them, in the olden times, lived withMaxwell, Laird of Dalswinton, doing ten men’s work and keeping the servantsawake at nights with the noisy dirling [clatter]of its elfin flail. The Laird’s daughter, says tradition, was the comeliestdame in all the holms of Nithsdale. To her the Brownie was much attached: heassisted her in love-intrigue, conveying her from her high tower-chamber to thetrysting-thorn in the woods, and back again with such light-heeled celeritythat neither bird, dog nor servant awoke.

"He undressed her for the matrimonial bed, andserved her so handmaiden-like that her female attendant had nothing to do, notdaring even to finger her mistress’s apparel, lest she should provoke theBrownie’s resentment. When the pangs of the mother seized his beloved lady, aservant was ordered to fetch the ‘cannie wife’ who lived across the Nith. Thenight was dark as a December night could be; and the wind was heavy among thegroves of oak. The Brownie, enraged at the loitering serving-man, wrappedhimself in his lady’s fur cloak and, though the Nith was foaming high-flood,his steed, impelled by supernatural spur and whip, passed it like an arrow. Seating the dame behind him, he took the deep water back again to the amazement of the worthy woman, who beheldthe red waves tumbling around her, yet the steed’s foot-locks were dry. – ‘Ride nae by the auld pool,’ quo’ she,‘lest we should meet wi’ Brownie.’ – He replied, ‘Fear nae, dame, ye’ve met a’the Brownies ye will meet.’ – Placing her down at the hall gate, he hastened tothe stable, where the servant lad was just pulling on his boots; he unbuckledthe bridle from his steed and gave him a most afflicting drubbing.

"This was about the new-modelling times of theReformation; and a priest, more zealous than wise, exhorted the Laird to havethis Imp of Heathendom baptised; to which he, in an evil hour, consented, andthe worthy reforming saint concealed himself in the barn, to surprise theBrownie at his work. He appeared like a little wrinkled, ancient man and beganhis nightly moil. The priest leapt from his ambush and dashed the baptismalwater in his face, solemnly repeating the set form of the Christian rite. Thepoor Brownie set up a frightful and agonising yell and instantly vanished,never to return.

"The Brownie, though of a docile disposition, wasnot without its pranks and merriment. The Abbey-lands, in the parish of NewAbbey, were the residence of a very sportive one. He loved to be, betimes,somewhat mischievous. – Two lassies, having made a fine bowlful of buttered brose[oatmeal gruel], had taken it into the byre to sup, while it was yetdark. In the haste of concealment they had brought but one spoon, so theyplaced the bowl between them and took a spoonful by turns. ‘I hae got but threesups,’ cried the one, ‘an’ it’s done!’ ‘It’s a’ done, indeed,’ cried the other.‘Ha, ha!’ laughed a third voice, ‘Brownie has gotten the maist o’t.’ He hadjudiciously placed himself between them and got the spoon twice for their once.

"The Brownie does not seem to have loved thegay and gaudy attire in which his twin-brothers, the fairies, arrayedthemselves: his chief delight was in the tender delicacies of food. Knuckled [kneaded] cakes made of meal, warm fromthe mill, haurned [roasted] on thedecayed embers of the fire, and smeared with honey, were his favourite hire;and they were carefully laid so that he might accidentally find them. – It is still a common phrase, when a childgets a little eatable present, ‘there’s a piece wad please a Brownie.’ "

[ Read my previous post on the Billy Blin': https://steelthistles.blogspot.com/2024/08/the-billy-blin-scottish-brownie.html ]

Picture Credits

Lob Lie By the Fire, by Dorothy P Lathrop: illustration to 'Down-a-down-derry,' Fairy Poems by Walter de la Mare 1922

Nis or Tomten Laughing at a Cat, by Theodor Kittelsen 1892

August 8, 2024

The Billy Blin': the Scottish Brownie

Iam extremely fond of house-spirits, two of which appeared in my first books for children. The three books of my Troll trilogy all feature one of the Scandinaviannisses I first met in Thomas Keightley’s 1828 compendium ‘The Fairy Mythology’. I was charmed by their mischief, vanity, naïvety, essential goodwill and occasionalbursts of temper. My Nis has all these characteristics and I love him. The secondhouse spirit arrived in my fourth book ‘Dark Angels’: he’s a hob (a ‘bwbach’ in Welsh) who lives under thehearthstone of a 12th century motte and bailey castle on the WelshMarches, loves food and does his gruff best to help the young daughter andheiress of Hugo de la Motte Rouge, the lord of the place. (I wrote a shortstory involving this hob, which you can read here.)

Thereare hobs or brownies in all parts of the British Isles, but some have names oftheir own, though these names themselves are often generic: if the English havePuck, the Irish have the pooka or phooka and the Welsh have the pwca... In Scotland though, the brownieis often named the Billy Blin’, with variants such as Billy Blynde or BellyBlin – and he is found in a number of ballads in which he usually takes on anadvisory role. I should issue a warning that the ballads 'Gil Brenton' and 'Earl Lithgow', examined in this post, include sexual violence.

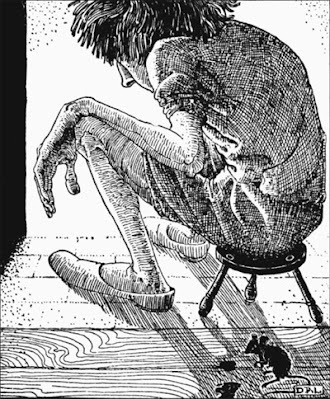

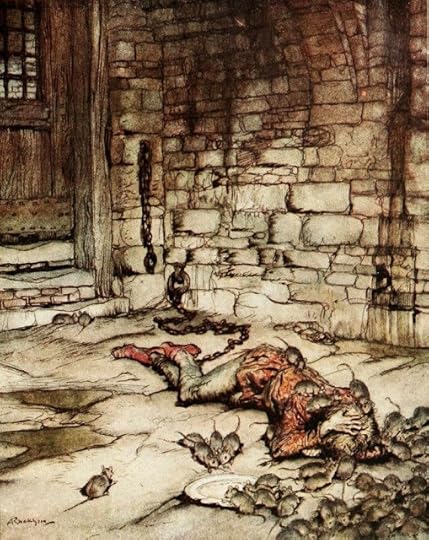

But ‘Young Bekie’ (Child Ballad 53c) does not! A Scottish knight named YoungBekie takes service with the King of France. He falls in love with the king’sdaughter, Burd Isbel, and is ‘thrown into prison strong’ where the mice and the‘bold rattons’ gnaw his yellow hair, a scene Arthur Rackham obviously could not resist illustrating. Burd Isbel simply steals the keys andrescues him: this practical young woman then provides a razor for his chin, acomb for his hair, five hundred pounds ‘for his pocket’, a fast horse and (a little oddly) a numberof hounds all from one litter, one of which is called Hector. The two young people then part, solemnly promisingto marry within three years. Off goes Young Bekie to Scotland and his ownlands, but within the year he is ‘forced to marry a duke’s daughter’ or loseall his land. The young man laments his ill fortune, since – he says –

‘I know not what to dee,

For I canno win to Burd Isbel

And she kens nae [doesn’t know] to come to me.’

Enterthe Billy Blin’:

O it fell once upon a day

Burd Isbelfell asleep

An up itstarts the Belly Blin

An stood ather bed feet.

‘Oh waken,waken, Burd Isbel,

How can yesleep so soun’

When this isBekie’s wedding day,

An’ themarriage gaein on?’

TheBilly Blin’ tells her what to do. She must take two of the ‘Marys’ (servingwomen) from her mother’s bower, dress them in green and herself in ‘the redscarlet’, with rich girdles about their waists, and go down to the sea strandwhere a ‘Hollans boat’ will come rowing in for them. Burd Isbel takes hisadvice and when the boat arrives, ‘the Belly Blin was the steerer o’t/To rowher o’er the sea.’ As Burd Isbel and her maids arrive at the castle gate, shehears music playing for the wedding, and gives the porter ‘guineas three’ tocall the bridegroom down to her. When the porter describes the ladies’ richclothing to the company the bride comments sarcastically that if these ladiesare ‘braw without’, she herself is ‘braw within’: but Young Bekie jumps up.‘I’ll lay my life it’s Burd Isbel/Come o’er the sea to me.’ Running downstairs hetakes her in his arms: she reminds him of all she’s done for him, the weddingis cancelled and the other bride sent home: ‘For I maun marry my BurdIsbel/That’s come o’er the sea to me.’

Isbel is not a bit surprised by the Billy Blin’s warning: he seems aknown and respected household inhabitant. I should like to point out that thisballad is another instance of the many ‘fairy’ tales, whether prose or verse,in which the girl does nearly everything: Burd Isbel gets all the action. Sherescues Young Bekie in the first place – and with help from the Billy Blin’ shecrosses the sea and ejects the bride he doesn’t want.

In‘Willie’s Lady’ (Child Ballad 6), a wicked mother – ‘a vile rank witch ofvilest kind’ – prevents her son’s wife from giving birth, so ‘in her bower shesits wi’ pain/And Willie mourns o’er her in vain.’ Willie tries bribing hismother to undo the spell she has cast on his wife:

He says; ‘Myladie has a cup

Wi’ gowd andsilver set about.

This goodliegift shall be your ain

And let herbe lighter o’ her young bairn.’

Hismother replies:

‘Of heryoung bairn she’ll ne’er be lighter

Nor in herbower to shine the brighter:

But sheshall die and turn to clay

And youshall wed another may.’

Whilehis wife lies in agony wishing she could die, Willie tries again to bribe his mother,offering her a horse shod with gold, with golden bells hanging from every lockof its mane. Again his mother refuses. Trying for the third time, Willie offersher his wife’s girdle of red gold, ringing with golden bells that hang from asilver hem, but this too is refused – and in steps the Billy Blin’.

Then out andspake the Billy Blind;

He spake ayein good time.

‘Ye doe yeto the market place

And there yebuy a loaf o’ wax.

Hetells Willie to mould the wax into the shape of a new-born baby, place two glasseyes in its head, invite his mother to its christening – and listen carefullyto her words. And fooled into believing the baby has been born, she exclaims:

‘Oh wha hasloosed the nine witch knots

That wasamong that ladie’s locks?

And wha has taenout the kaims of care

That hangsamong that ladie’s hair?

And wha’staen down the bush o’ woodbine

That hangsatween her bower and mine?

And wha haskilld the master kid

That ranbeneath that ladie’s bed?

And wha hasloosed her left-foot shee

And lettenthat ladie lighter be?’

Hearingthis, Willie looses the nine witch knots, removes the ‘combs of care’, pullsdown the bush of woodbine, kills the ‘master kid’ – it really is a young goat! –and takes off his wife’s left shoe. The lady then promptly gives birth to ‘abonny young son’. We don’t find out what, if anything, happens to the wickedmother; it’s simply to be hoped she doesn’t try this again – but the BillyBlin’ has clearly saved the day.

In‘Gil Brenton’ (Child Ballad 5c), the young hero – a title he hardly meritsgiven his behaviour – meets a young woman, the seventh of seven sisters, who comesto the wood to pick lilies and roses for her sisters’ bowers. She tells what happened next:

‘And was Iweel or was I wae

He keepit mea’ the simmer’s day.

‘And tho Ifor my hame-gaun sicht [sighed for myhome]

He keepit mea’ the simmer nicht.’

Hegives her tokens – a gold ring, a shortknife and ‘three locks of his yellow hair’ – and then departs. The result ofcourse is that she becomes pregnant, and seeks to find him across the sea. Sendingher dowry ahead of her, she arrives at his dwelling, only to be warned that‘Childe Brenton’ has already ‘wedded’ seven king’s daughters, but never beddedthem: they have all proved not to be maidens, so he has ‘cut the breasts fraetheir breast-bane’ and sent them back to to their fathers. Mysteriously shestill wants to marry him, and is warned also not to sit in a particular goldenchair until she is bidden to do so. But she does. At this point the Billy Blin’pops up and defends the girl by suggesting that she only sat in the chairbecause ‘the bonnie may is tired wi’ riding’ – which sounds reasonable in anotherwise unreasonable milieu. Presumably anxious about the chance of having herbreasts carved off by an ‘unco’ lord’ (‘unco’means strange, uncanny, weird, a description we can agree seems apt) she begs her virginal maid to take her place inthe bridal bed. For her lady’s sake the girl agrees, and when they are lyingdown together Gil Brenton asks the Billy Blin’ to tell him ‘if this fair damebe a leal [true] maiden’. The BillyBlin’ replies:

I wat [know] she is as leal a wight

As the moonshines on in a simmer night.

I wat she isas leal a may

As the sunshines on in a simmer day.

But yourbonnie bride is in her bower

Dreeing themither’s trying hour.’

[Enduringthe birth of her child: becoming a mother]

Leapingout of bed, Gil Brenton runs to his mother’s bower and tells her that ‘themaiden I took to my bride/Has a bairn atween her sides’ and is currently givingbirth. You’d assume this might have been noticed before, but this is a ballad:so no. Rushing to the lady’s chamber, his mother flings the door wide,demanding to know who is the father of the child? The lady tells her story, producesthe tokens, and the pair are united. This particular version was taken andslightly abridged, from R.H. Cromek’s ‘Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song’(1810) in which the introduction states it to have been ‘copied from therecital of a peasant-woman of Galloway, upwards of ninety years of age’, whichmay well put it back at least to the mid-1700s. Cromek gives the title as ‘WeWere Sisters, We Were Seven’, and he comments:

The singularcharacter of the Billy Blin’ (the Scotch Brownie, and the lubbar fiend ofMilton*) gives the whole an air of the marvellous, independently of the mysticchair, on which the principal catastrophe [denouement,reveal] of the story turns.

Strangely, the ‘Child 5c’ version misses out a long versepassage from Cromek’s. In it, following the rape and ignorant of the victim’sidentity, Brenton arrives at the seven sisters’ gate and shouts that he’s a‘lord o’ lands wide’ and wants one of them to be his bride, preferably theyoungest. The youngest, speaking for herself, remarks: ‘Little ken’d he, whenaff he rode,/I was his token’d luve in the wood’ – but at least the passageexplains how she knows where to find him, and where to send the dowry. Unembarrassedby Brenton’s dubious character, the ballad ends on a tender note as Brentonkneels at his lady’s bedside:

O tauk [take] ye up my son,’ said he,

And mither,tent [look after] my fair ladie;

O wash himpurely in the milk,

And lay himsaftly in the silk;

An’ ye maun [you must] bed her very soft,

For I maunkiss her wondrous oft.

It was wellwritten on his breast bane,

ChildeBranton was the father’s name;

It was wellwritten on his right hand,

He was theheir o’ his daddie’s land.

Ballads in which the girl ends up married to the man who raped her seem deeplyproblematic today. Back in those days though, how likely was it that girls insuch circumstances got any redress whatever? I think such ballads offer a fantasyending: the girl gets married to the rich lord and her child becomes legitimate, and heir to a fine estate. The Billy Blin did his best, Isuppose.

A ballad with a similar theme is ‘Earl Lithgow’, variant F of ChildBallad 110 generally known as ‘The Knight and the Shepherd’s Daughter’. The Billy Blin’once more appears in it; this ballad toobegins with a rape; but the young woman gets as good a revenge as she can andis more than a match for Earl Lithgow. He tries to hide his identity, but sheknows his real name and races after him when he rides away. When they come tothe River Dee his horse swims it, but she swims faster, fast as an otter and reachesthe ‘queen’s high court’ well ahead of him, where she gains an audience withthe queen. Announcing proudly that she can neither ‘card nor spin’, but knowshow to ‘sit in a lady’s bower and lay gold on a seam’, she accuses Lithgow, whois the queen’s brother, of stealing her maidenhead. Brought before her, Lithgowattempts to pay her off with one – two – three purses of gold, but the youngwoman will have none of it:

‘I’ll haenane o’ your purses o’ gold

That ye tell[count] on your knee:

But I willhae yoursell,’ said she,

‘The queenhas granted it me.’

Thefurious Earl is forced to marry her, and she taunts him with her supposed lowbirth (he wasn’t there when she told the queen about being able to sew withgold thread). As the pair pass by a watermill, she tells him how her ‘auldmither, the carlin’ (a carlin is an old woman) would have pricked and stung himlike the nettles that grow by the dyke.

‘Sae well’sshe would you pyke,’ she says,

‘She wouldyou pyke and pou [prick and pull],

And wi’ the dust lies in the mill

Sae wouldshe mingle you.’

Ifthat wasn’t sufficiently crushing, she further informs him that her ‘mither’would sup till she was full, lay her head on a sod and snore like a sow. This is her heritage: THIS is who he’smarried! He can throw his china plates away: she’s happy eating from a ‘humble gockie’ – a wooden dish. She doesn’twant to sleep in ‘holland sheets’, not she: she prefers ‘canvas clouts’. She iswreaking sweet revenge on him by shaming him socially as deeply as he’d shamedher. And it’s working:

He’s drawnhis hat out ower his face,

Muckle shamethought he;

She’s drivenher cap out ower her locks,

And a lightlaugh gae she.

Ilove that! At long last he begins to wonder about her. ‘If ye be a carlin’sget,’ he begins slowly, still unsure – ‘As I trust well ye be/Where got ye allthe gay claithing/Ye brought to the greenwood with thee?’ The quick-thinkingyoung woman instantly replies that her mother was an old nurse, whose mistresswould sometimes give her cast-off clothes which she kept for her daughter. Thencomes the sting in the tail:

And I put them on ingood greenwood,

To beguile fause [false] squires like thee.

Atthis point the Billy Blin’ decides that enough is probably enough, and intervenes.

It’s out then spake thebilly-blin,

Says, I speak nane outof time [not before time]

If ye make her lady o’ nine cities,

She’ll make you lord o’ten.

Out it spake thebilly-blin,

Says, The one may servethe other;

The king of Gosford’s aedaughter,

And the queen ofScotland’s brother.

Revealedas a princess, the girl is distinctly displeased and turns on him:

Wae but worth you,billy-blin.

An ill death may ye die!

My bed-fellow he’d beenfor seven years

Or he’d ken’d sae mucklefrae me.

[He’dhave been my bedfellow for seven years

Beforehe’d learned so much from me!]

She’sclearly enjoyed humiliating her new husband, who equally clearly deserved it. Henow at least tries to make peace, saying:

Fair fa’ ye, ye billy-blin

And well may ye aye be!

In my stable is theninth horse I’ve kill’d

Seeking this fair ladie.

Now we’re married andnow we’re bedded

And in each other’s armsshall lie.

Here’sto the girl who got her own back! More colourful stuff about theBilly Blin’ in my next post.

* The lubber fiend is described by Milton as a 'drudging goblin' in his 1631 poem L' Allegro. After spending a night threshing a quantity of corn that 'ten day-labourers could not end': "Then lies him down, the lubber fiend/And stretch'd out all the chimney's length/Basks at the fire his hairy strength...' He sounds rather large for a brownie, but who knows?

Picture credits

Brownie sweeping - by Alice B Woodward, wikipedia

Young Bekie in prison - by Arthur Rackham - Some British Ballads, 1919

The Billy Blin' wakes Burd Isbel - by Arthur Rackham - Some British Ballads, 1919

Willie's Lady - by Vernon Hill - Ballads Weird and Wonderful, 1911

The Knight and the Shepherdess - by Byam Shaw - Ballads and Lyrics of Love, 1908