Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 3

October 5, 2023

'Nagas and Garudas, Dreams and Stars', a guest post by Shevta Thakrar

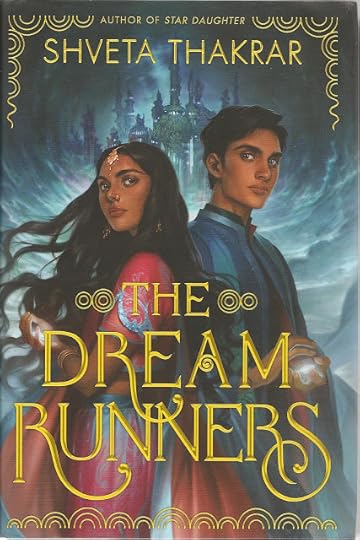

I’m delighted to welcome forthe second time to my blog the author Shveta Thakrar, whose second YA novel TheDream Runners was published by HarperCollins last year. I thoroughly enjoyed herdebut novel Star Daughter and this one's even better. Shvetaweaves into her YA fantasies all kinds of mystical beings from Hindu legends and sacred texts, and Holly Black describes her writing as ‘beautiful as starlight’. In this post, Shveta retells the story of the enmity between the nagas and garudas, describesthe creative thinking behind her novel, and challenges us toconsider ways to turn old enmities into friendships.

#

We all know aboutfaerie courts. Night Courts and Bright Courts, Seelie and Unseelie. But what ofnagas and garudas?

TheDream Runners, the second in my Night Market triptych of YA fantasynovels based on various aspects of Hindu mythology, started out as an answer tothat question. I’d finished all work on StarDaughter, and my editor reached out to ask me what was next. I tooksome time to ponder that. I knew I loved changelings and faerie courts, but Iwasn’t ready to stop writing about Hindu mythology and folklore when I’d reallyonly just begun.

Garuda devouring a naga

Garuda devouring a nagaThen it struck me: I already knew of a similar scenario,that of the ancient mythical war between the nagas—serpent shape-shifters—andtheir cousins and mortal enemies, the garudas—eagle shape-shifters. With suchsharp lines of division, these two groups might as well be two opposing courts.In fact, since I am a storyteller, allow me now to tell you their tale.

#

(There are, of course,different variations and even different narratives, but this is the version Ilearned as a child. And if you enjoy it, I highly recommend seeking out aseries of comic books called AmarChitra Katha, which recount many Indian myths and legends.)

Long, long ago, in the time of the Mahabharata,there were two sisters, the elder called Vinata and the younger Kadru, daughters of Lord Daksha. Wed to the samerishi—sage—Kashyapa, bothsisters bore children by him after requesting that boon: Vinata gave birth totwo eggs, which contained Arun, who laterbecame Lord Surya’scharioteer, and Garuda,while Kadru gave birth to a thousand eggs, from which emerged the first nagas.

One day, Kadru, known for her wily nature, challengedVinata to name the color of the tail of Uchchaihshravas, thedivine horse born from SamudraManthan, the churning of the Cosmic Ocean of Milk.However, the wager came with a cost: should Vinata answer incorrectly, she andher son would then become enslaved to Kadru and her brood. If she answeredcorrectly, the reverse would be true. The question seemed simple enough, and asthe seven-headed horse was radiantly white from head to toe, Vinata guessed thathis equine tail was white.

But Kadru had been scheming. She sent her children, thenagas, to cover Uchchaihshravas’s tail, then brought her sister to see him.“Black,” she pronounced, and her unfortunate sister had no choice but to agree.

The humiliation of being proven wrong would have been unpleasantbut bearable, had that been the only consequence. Of course, it was not, and soVinata and Garuda began their indenture, waiting upon her sister and her niecesand nephews. Watching his mother endure their abuse was an indignity Garudacould not accept, and from that day forward, he nursed a grudge against hiscousins, stoking the fires of his hatred.

At last, having grown mighty, with a wingspan that couldblock the sun, he demanded of Kadru that she free Vinata. Kadru, naturally, woulddo no such thing without a price: the amrit from the heavenly realmof Svargalok. Garuda then fought all the gods in the realm, even Lord Indra,and came away with the nectar. Kadru freed her sister and instructed Garuda to distributethe amrit amidst her children.

Garuda returns with the vase of Amrita

Garuda returns with the vase of AmritaHowever,Lord Indra had beseeched him not to grant it to the nagas, so instead, Garudacommanded them to wash and purify themselves before they could imbibe. Whilethey did so, Indra’s son, Jayanta,stole the vessel back. When the nagas returned, Garuda consumed them all.

(Yetin the contradictory way of mythology, there are still more nagas and later arace of garudas, who continue this enmity forever more.)

And that, gentle reader, is why eagles eat snakes.

#

I’ve always beenfascinated by this story—and the antics people get up to when they have no truepurpose driving them—so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that I had initiallyused it in my first attempt at a novel, now trunked. But when my editor camecalling, it occurred to me that I could cannibalize elements from that trunkednovel and incorporate them into what became The Dream Runners. By then, Ihad become a skilled enough writer to do the myth justice.

Thatoriginal attempt featured a human main character named Sameer, who becamerelegated to a tertiary character in The Dream Runners, while hisgirlfriend, the delightful and audacious nagini Princess Asha, now took on agreater role as a secondary character. I also—of course—resurrected the magicalbar with its enchanted libations as silver wine (distilled moonlight) and setit in the Night Market from Star Daughter, thus connecting the two books.

Meanwhile, two new characters, Tanvi, a dream runner whostarts waking up, and Venkat, the dreamsmith she previously sold her harvesteddreams to in return for a beloved bracelet, ran away with the story of boonsand dreams and arranged marriages between naga clans, all set against thebackdrop of the mythological war between the garudas and the nagas.

And so, The Dream Runners became my lovingfanfiction of the original myth.

#

Myths exist for manyreasons, one of which is to reflect our lives back to us. I cannot help but seethe connections between things, and I think a lot about interpersonalcommunication, empathy, and what plays out on the world stage when we forget thatwe’re connected and view others as our rivals, if not as our enemies. When weforget that, as the Sanskrit saying goes, we are all one world family: वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम (vasudhaiva kutumbakam), we harm both others andourselves.

As in the myth, that fundamental truth getsdismissed again and again in a dog-eat-dog global society focused on greed forthe few at the cost of the rest. Though I didn’t intend it, there’s definitelyan anticapitalist slant to The Dream Runners. I might not have realized that’swhat I was writing in Tanvi and her harvesting, but I stand by it.

So,returning to the matter at hand: What do you do once a war has calcified intowhat appears to be inevitability, and seemingly unmovable, unbreachable lineshave been drawn? When you hurt me, so now I must hurt you, and because I hurtyou, you will now hurt me?

How do we break old cycles of violence and hatred?

Iwon’t spoil how my characters choose to solve that problem, but I personallybelieve that we need to find answers to these questions. Our worlddepends on it. I wrote The Dream Runners to be a magical escape for myreaders, to celebrate Hindu mythology and shine a spotlight on the beingslesser known in the West, but also to get us to consider if there might be alternativesto the way it’s always been. If we can write a new ending to an old story.

Iinvite you to start writing yours.

Picture credits

The Dream Runners by Shveta Thakrar, HarperTeen. Cover art by Charlie Bowater

Garuda devouring a naga: Painting at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Bangkok, Wikipedia

Uchchaihshavras: origin unknown: https://www.quora.com/What-is-known-about-Uchchaihshravas

Garuda returns with the vase of Amrita: V&A collections

September 21, 2023

Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers #3

Probably the best-knownenchanted sleeper after the Sleeping Beauty is Rip van Winkle. A lazybonesliving in the Catskill Mountains, he prefers hunting to hard work. Out with hisdog one evening, he helps a strange little fellow to carry a keg up themountain. They arrive at ‘a hollow, like a small amphitheatre, surrounded byperpendicular precipices, over the brinks of which impending trees shot theirbranches, so that you only caught glimpses of the azure sky and the brightevening cloud.’

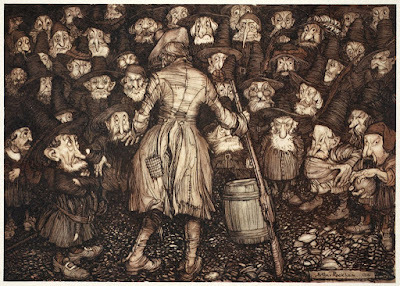

Within this cave-likestructure a number of ‘odd-looking personages’ dressed in old-fashioned clothesare playing at ninepins in complete silence except for the noise of the rollingballs which raise thunderous echoes. Stopping their play, they stare at Rip‘with such fixed, statue-like gaze, and such strange, uncouth, lack-lustrecountenances, that his heart turned within him and his knees knocked together.’Rip nervously serves the little men drinks from the keg, after which theyreturn to their game; he tries the beverage himself, and falls asleep fortwenty years.

Rip is the invention ofWashington Irving who published the tale in 1819, but he based it heavily on aGerman folktale ‘Peter Klaus’. Peter is a goatherd from Sittendorf who pastureshis herd on the Kyffhäuser, a prominent hill south-east of the Harz mountains.Following a stray goat into a cave, Peter finds it eating oats mysteriouslyshowering from the roof. He hears horses neigh and stamp overhead, and a youngman beckons him up steps into a ‘deep dell, inclosed by steep craggyprecipices’ where ‘on a well-levelled, cool grass plot’, twelve knightssilently play skittles and sign for him to set up the fallen ones. Peter obeys:then growing bolder, drinks wine from a nearby pitcher and falls asleep ony towake stiff and old, with a beard a foot long. Descending the mountain to Sittendorf,he finds his house a ruin and recognises no one until a young woman tells himthat Peter Klaus was her father – ‘It is now twenty years and more since wesearched for him a whole day and night on the Kyffhäuser. ... I was then sevenyears old.’

Relevant to this tale is thelegend that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122-1190) sleeps in acave under the Kyffhäuser with six of his knights. He sits at the head of astone table and has been there so long that his great red beard has grown rightthrough the stone. This legend haunts the story of poor Peter Klaus andexplains his fate. Anyone local to the Kyffhäuser would know at once that thecave, knights and horses belonged to Barbarossa. It’s generally a riskybusiness to enter the cave of a sleeping king and his army, especially if oneof the sleepers stirs and asks ‘Is it time?’ (The best plan is to answer, ‘No,sleep on!’ and flee.) Hugh Miller, in his 1891 book Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland, relates how a manentered the Dropping Cave of Cromarty and fuelled by alcohol, blew a blast on abugle he found lying beside a vast sarcophagus, disturbing an unknown warrior:

Thecover heaved upwards, disclosing a corner of the chasm beneath; and a handcovered with blood and of such fearful magnitude as to resemble only theconceptions of Egyptian sculpture, was slowly stretched from the darknesstowards the handle of the mace. Willie’s resolution gave way, and flinging downthe horn he rushed toward the passage. A yell of blended grief and anger burstfrom the tomb, as the immense cover again settled over it.

So far as I know, WashingtonIrving had no similar legend of the Catskills to apply to Rip van Winkle, buthis odd little men are sufficiently fey to be disturbing. The fairiestraditionally dressed in old-fashioned clothes, and in Arthur Rackham’sillustrations to Rip van Winkle thelittle men look very like goblins.

Characters like Rip fallasleep in consequence of having accidentally strayed into what might be termeda supernatural danger zone. In fact, the ‘supernatural lapse of time’ – thephrase coined by Edwin Sydney Hartland in TheScience of Fairytales (1890) – experienced by Rip and the sleeping PeterKlaus is very similar to that of those who visit fairyland for what seems a fewdays or hours, but find on their return that years or centuries have passed.

The 12th centurycourtier Walter Map tells of King Herla of the Britons, who goes to the weddingof a pygmy fairy king (half goat, half man) in underground halls of greatsplendour. After the wedding, the pygmy king loads Herla and his retinue withgifts including a small hound for Herla to carry on his saddle, warning thatneither he nor any of his men should dismount before the dog leaps down.Emerging into the open, Herla asks an old shepherd for news of his queen, butthe shepherd can hardly understand him. ‘You are a Briton and I a Saxon... longago, there was a queen of that name ... who was the wife of King Herla; and he,the story says, disappeared in company with a pygmy at this very cliff and wasnever seen on earth again.’ Forgetting the fairy king’s warning, some ofHerla’s men jump from their horses and crumble instantly to dust: and Herlastill rides the hills with the rest of his company, for the little dog has notyet leapt down.

The same prohibition wasplaced on Oisin, son of the Irish hero Finn, who married Niamh of the GoldenHair, daughter of the King of the Country of the Young and went away with herto that country, riding over the sea. After spending three years there he longedto see his father Finn again. Niamh gave him permission, and her horse, and warnedhim on no account to dismount or put foot to the ground. Of course he forgot.

Some say it was hundreds of years he was in that country,and some say it was thousands of years he was in it; but whatever time it was,it seemed short to him. And whatever happened to him through the time he wasaway, it is a withered old man he was found after coming back to Ireland, andhis white horse going away from him, and he lying on the ground.

Gods and Fighting Men, Book XI, Ch 1, tr. Lady Augusta Gregory

Oisin leaves the land ofeverlasting youth and returns to mortal soil, where the weight of centuries fallsand crushes him. In a dialogue with St Patrick he describes himself as ‘an oldman, weak and spent, without sight, without shape, without comeliness, withoutstrength or understanding, without respect.’ Patrick tries to convert him, butOisin has the last word:

'Oisin and Patrick' by PL Lynch

'Oisin and Patrick' by PL Lynch‘It is a good claim I have on your God, to be among hisclerks the way I am; without food, without clothing, without music, withoutgiving rewards to peers. Without the cry of the hounds, without guardingcoasts, without courting generous women; for all that I have suffered by thewant of food, I forgive the King of Heaven in my will.

‘My story is sorrowful. The sound of yourvoice is not pleasant to me. I will cry my fill, but not for God, but becauseFinn and the Fianna are not living.’

Godsand Fighting Men, Book XI, Ch V, tr. Lady Augusta Gregory

Or are they? In most accountsOisin dies; his grave, like Arthur’s, is located in various places –Antrim, Armagh, even Scotland – but forFinn and the Fianna ‘there are some say he never died, but is alive in someplace yet.’

And one time a smith made his way into a cave he saw, thathad a door in it, and he made a key that opened it. And when he went in he sawa very wide place, and very big men lying on the floor. And one that was biggerthan the rest was lying in the middle, and the Dord Fiann [Finn’s war-horn] beside him, and knew it was Finn and the Fiannawere in it.

And thesmith took hold of the Dord Fian, and ... blew a very strong blast on it ...And at the sound, the big men lying on the ground shook from head to foot. Hegave another blast then, and they all turned on their elbows. And great dreadcame on his when he saw that, and he threw down the Dord Fian and ran from thecave and locked the door after him, and threw the key into the lake. And heheard them crying after him, ‘You left us worse than you found us.’ And thecave was not found again since that time.

But somesay the day will come when the Dord Fian will be sounded three times, and thatat the sound of it the Fianna will rise up as strong and well as ever theywere...

Godsand Fighting Men, Book X, Chapter III, tr. Lady Gregory

(If you want to hear what theDord Fian might have sounded like, clickthis link.)

Versions of this tale-typeknown as ‘the king asleep in the mountain’ are found worldwide, and I can’tresist sharing my recent discovery – recent to me, though known to many – ofperhaps the earliest European ‘sleeping king’ narrative. It’s recorded by the 1st/2ndcentury CE Greek historian and philosopher Plutarch, who attributes it toDemetrius the Grammarian ‘travelling home from Britain to Tarsus’. In onedialogue ‘On the Silence of the Oracles’, Demetrius tells how on one of themany islands lying around Britain, Cronus (Saturn) lies sleeping, guarded bythe hundred-handed monster Briareus: ‘and round about him are many demigods asattendants and servants.’ Anotherdialogue ‘On the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon’ elaborates thisaccount:

A run of five days off from Britain as you sail westward,three other islands equally distant from it and from one another lie out fromit in the general direction of the summer sunset. In one of these, according tothe tale told by the natives, Cronus is confined by Zeus, and the antiqueBriareus, holding watch and ward over those islands and the sea that they callthe Cronian main, has been settled closebeside him.

[...]

ForCronus himself sleeps confined in a deep cave of rock that shines like gold –the sleep that Zeus has contrived like a bond for him – and birds flying inover the summit of the rock bring ambrosia to him, and all the island issuffused with fragrance scattered from the rock as from a fountain; and thosespirits mentioned before tend and serve Cronus, having been his comrades whattime he served as king over gods and men.

I wonder if Demetrius reachedthe island on which ‘Cronus’ sleeps by circumnavigating Britain anti-clockwise,and sailed down the west coast from the north?

[T]hosewho survive the voyage first put in at the outlying islands [...], and see thesun pass out of sight for less than an hour over a period of thirty days, – andthis is night, though it has a darkness that is slight and twilight glimmeringfrom the west [...] and then winds carry them to their appointed goal.*

This description of the longnorthern summer days and short nights convinces me that Demetrius really did sail in northern waters and picked up information and stories ‘according tothe tale told by the natives.’ It’s tantalising! What Celtic god or hero seemedto Demetrius’ Greco-Roman mind, the equivalent of Cronus/Saturn, father ofZeus?

Whoever that might be (incidentally, a friend has reminded me of CS Lewis's giant Father Time, who sleeps in a cave under Narnia until Time ends – Cronus is a personification of time, and you can bet Lewis knew his Plutarch) theroll-call of sleeping heroes includes figures named and unnamed, legendary andhistorical: Finn, Barbarossa, Charlemagne, Ogier the Dane, and of course there’sArthur.

Some men say in many parts of England that King Arthur isnot dead, but had by the will of Our Lord Jesu into another place; and men saythat he shall come again, and he shall win the holy cross. I will not say thatit shall be so, but rather I will say, here in this world he changed his life.But many men say there is written upon his tomb this verse: HIC IACET ARTHURUS,REX QUONDAM REXQUE FUTURUS.

Le Morte D’Arthur, Book XXI, chapter 7

Malory’s Arthur is taken awayin a barge to ‘the isle of Avilion, to heal me of my grievous wound’, butEngland, Wales and the Borders are full of tales of the king and his knightssleeping hidden under a hill. Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpsonsummarize the stories in their comprehensive guide to England’s legends, The Lore of the Land.

In several places, including Sewingshields, Northumberland,and Richmond Castle, Yorkshire, it is said that a man finds a secret doorway ina hillside, leading to a cavern where Arthur and his knights sleep, surroundedby weapons and treasures, which may include some significant objects, such as asword, a horn, or a bell. [...] The sleepers begin to stir, and the intruderpanics and flees. He... can never find the hidden entrance again; meanwhile,Arthur and his knights return to their enchanted sleep, for the time for theirreturn has not yet come. Other stories, collected in the late 19thcentury, say Arthur and his court dwell inside the hill-fort of Cadbury Castle,Somerset; on the nights of full moon they emerge on horses shod with silver.

The Lore of the Land, p310

It’s easy to see how the ‘kingunder the hill’ tales bleed into fairyland. The Cadbury legend makes Arthur andhis silver-shod steeds sound very like the Seelie Court or Faerie Rade. Otherthan their regular full-moon wandering, the rest of the time do they sleep? TheIrish Earl Gerald of Mullaghmast, a master of the black arts, sleeps with hiswarriors in a cave under the Rath ofMullaghmast. Once every seven years he wakes and ‘rides around the Curragh of Kildareon a horse whose silver shoes were half an inch thick’ when he fell asleep.When they are worn ‘as thin as a cat’s ear, a miller’s son with six fingers oneach hand will blow his trumpet’ and the Earl and his men will wake and rideout against the English.

Perhaps Tolkien remembered thesestories when he sent Aragorn into the Dwimmerberg, the Haunted Mountain, tosummon the King of the Dead and the shadow army which slept there. Once theyhave fought on his side against the hordes of Mordor, Aragorn holds the dead king's ancient oath fulfilled, and the shadow army dissolves like mist.

Kings or heroes, all male,lying asleep in caves or underground: like the tales I explored in my firstpost and unlike those of the second, these narratives focus on the lapse oftime and its effect, but there is a difference. King Mucukunda, the SevenSleepers, Honi the Circle-Drawer and their ilk were all put to sleep by somedivinity – and for a purpose. And their experiences were ultimately positive:they received divine lessons or blessings and departed this life in peace. Thatis not the case in these tales. Nothing St Patrick says can comfort Oisin,whose lament expresses not only the personal, emotional cost of the lost years,but fierce grief for a vanished way of life and the age of heroes.

What causes this difference? Whiledeities can be expected to look after you, it is dangerous to trespass into theOtherworld of the Sidhe, where humanity does not belong, and even moredangerous if you taste food or drink there. The fair folk don’t age like us.Even Aragorn in The Lord of the Ringswill grow old long before his elven bride, Arwen.

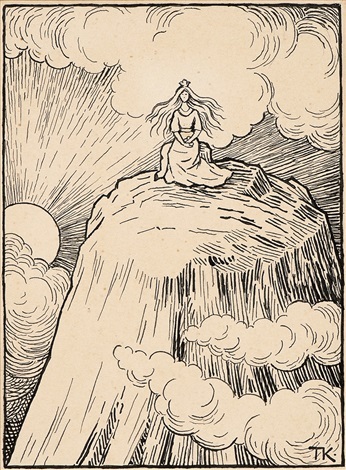

The women in my second post donot sleep in caves. They sleep in the open air on hilltops, or in the morecivilised environment of hall or castle. And they do not age. During hercentury of sleep the Sleeping Beauty does not age at all, neither does thevalkyrie Sigrdrifa in the Poetic Edda,or Brynhild in Volsunga Saga: theywake from their enchantments as active, young and beautiful as when they fellasleep. But whether by gradual natural process or sudden dynamic change, PeterKlaus, Rip van Winkle and Oisin do age. They sleep for decades and wake alreadyold, or discover they’ve skipped a huge span of years and instantly wither –some into dust.

A tale in The Celtic Magazine of November 1887 tells how a young bridegroomleaving the church after his wedding was stopped by ‘a tall dark man’ who askedhim to come around the back of the building with him for a quick word, and askedhim to stand still till a small piece of candle he held in his hand should burnout. The bridegroom complied; it burned for two minutes, then he ran after hisfriends. They were out of sight, so he asked a man cutting turf if he had seenthe wedding party go by. The turf-cutter shook his head: ‘Not for a long timepast. What did you suppose the date of the wedding to be?’ The bridegroom gavea date two hundred years in the past. And the turf-cutter told him, ‘Mygrandfather had a tale his grandfather told him, of a bridegroom whodisappeared on the day of his wedding.’ ‘I am that bridegroom!’ the young mancried, and fell as he spoke into a small heap of earth.

Maybe that’s the best way togo? For those who survive for a while, the sense of loss is devastating. In Ripand Peter Klaus’s case, meeting a grown daughter and grandchild offers partialconsolation, but there is no recovering lost youth.

As for the ones who grieve forthe lost years but do not die, one thing is clear: they are divorced from theflow of time. They cannot grow or change. Some spend the endless years likeKing Herla who ‘holds on his mad course with his band in eternal wanderings, withoutstep or stay’. This is not like sleep, which indeed doesn’t feature in Herla’stale, but it speaks of an inability to rejoin or ever to take part again innatural life. Unable even to dismount from their steeds, Herla and his troopare forever homeless, ‘blown in restless violence round about the pendantworld’, to quote Shakespeare. And the kings and their knights lie in theircaves in suspended animation, neither dead nor truly alive, waiting for the daywhen they will be needed, will be relevant again. Alas, it is a day that may nevercome, for – Aragorn excepted – in no story has any intruder ever wanted to wakethem.

* Charles William King, whose1908 translation this is, tells us that Demetrius was sent to the islands ofBritain by Trajan (who was emperor from 98 – 117 CE) and suggests that one of theislands may be Anglesey – ‘the focus of Druidism’ – since only ‘holy men’ aresaid to inhabit it. Could there still have been druids on Anglesey at the endof the 1st century CE? I suppose it’s possible, even after the 60-61 CEinvasion by Suetonius Paulinus (busily burning the sacred groves just beforenews of the Boudiccan rebellion reached him), and that of Agricola in 77 CE.Druidism might well have hung on for quite a while, as the account goes on toexplain that the cave of Cronus is a centre for oracles and prophecies described as ‘the dreams of Cronus’.

Picture credits

Sleeping King Arthur: illustration by Eric Fraser for 'English Legends' by Henry Bett

'They stared at him': illustration to Rip van Winkle by Arthur Rackham

Barbarossa in the Kyffhauser: artist unknown

Oisin and Niamh by Richard Hook: see https://littleisobel.com/home/2011/10/12/richard-hook-great-folk-tales-of-old-ireland/

Oisin meets Patrick:

The Death of King Arthur: painting by John Garrick, 1862

To the Stone of Erech: by Inger Edelfeldt

Rip van Winkle: by Arthur Rackham

September 7, 2023

Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers #2

My last post concerned anumber of enchanted sleepers, all male, whose lengthy slumbers – howeverinconvenient – were almost entirely benign, awarded by the gods or God in orderto save, enlighten or confer spiritual blessings upon them; and sometimes allthree, for even when the sleeper awakes only to die shortly afterwards, he doesso in a state of holiness or grace. This time I’m looking at enchanted sleepnarratives involving women, in which the motivation of the instigator is consistently malign and the dénoument is often far from satisfactory.

Sigurd kills Fafnir...

Sigurd kills Fafnir...

The poems known as the Poetic Edda are preserved in manuscriptsdating back to the 13th century CE but derive from much older oraltradition. One of them, the ‘Lay of Fafnir’, tells how the hero Sigurd slaysthe dragon Fafnir, cuts out and cooks the heart for the dragon’s treacherous humanbrother Regin, and tests it with his finger to see if it’s done.

...and licks the blood from his thumb

...and licks the blood from his thumbAfter lickingthe blood he understands the speech of birds – nuthatches – which warn him tokill Regin, and direct him to the sleeping valkyrie Sigrdrifa. In the wonderfultranslation by Carolyne Larrington:

There is a hall on high Hindarfell

outside it is all surrounded with flame;

wise men have made it

[...]

I know on the mountain the battle-wise one sleeps

and the terror of the linden [fire] plays above her;

Odin stabbed her with a thorn

[...]

Young man, you shall see the girl under the helmet,

who rode away from battle on Vingskornir.

Sigdrifa’s sleep may not be broken,

by a princely youth, except by the norns’ decree.

ThePoetic Edda, tr. Carolyne Larrington, OUP

Sigurd kills Regin,loads his horse Grani with Fafnir’s treasure and rides off. The story continuesin ‘The Lay of Sigrdrifa:’ Sigurd climbs ‘high Hindarfell’ and finds thevalkyrie lying asleep surrounded by flames and a rampart of shields. Crossingthis barrier, Sigurd lifts off her helmet and with his sword Gram cuts away themail corselet which is biting into her flesh. Waking, she explains that inrevenge for the killing of a king to whom he had promised victory, Odin‘pricked her with a sleep-thorn’ and told her that she would never again bevictorious in battle, but should marry instead. At Sigurd’s request, Sigrdrifaconfers wisdom on him by teaching him many runes. The manuscript then breaksoff, but the exact same story is told in VolsungaSaga about the valkyrie Brynhild, who explains on waking:

In the battle I struck down Hjalmgunnar, and in retaliationOdin pricked me with the sleep thorn, said I should never again win a victory,and that I was to marry. And in return I made a solemn vow to marry no one whoknew the meaning of fear.

The Saga of the Volsungs, tr. Jesse L.Byock, Penguin Classics

She and Sigurd exchangevows. ‘Sigrdrifa’ appears in no other context, and Carolyne Larrington suggeststhe two valkyries are identical. The tale goes on to utter catastrophe. Unwittinglydrinking a potion that makes him forget Brynhild, Sigurd marries Gudrun andtricks Brynhild into marrying Gudrun’s brother Gunnar – impersonating him inthe test Brynhild sets her suitors, and leaping his horse through the ring offlames surrounding her hall. When she finds out, a bloodbath ensues anddoubtless Odin is satisfied.

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flames

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flamesBut what is a‘sleep-thorn’? Though ‘stabbed’ and ‘pricked’ by it, Sigrdrifa also refers to‘sleep-runes’.

Long I slept, long was I sleeping,

long are the woes of men;

Odin brought it about that I could not break

the sleep-runes.

The Poetic Edda, tr.Carolyne Larrington, OUP

I don’t know whetherit’s coincidental that ‘thorn’ is the name of the rune Þ (pronounced as a soft‘th’), or that Odin, in Hávamal,seizes the runes or runelore after hanging nine nights on a mystical tree.

I know that I hung on a windswept tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.

With no bread did they refresh me, nor a drink from a horn,

downward I peered;

I took up the runes, screaming I took them,

Then I fell back from there.

ThePoetic Edda, tr. Carolyne Larrington, OUP

Whatever the runicimplications, a ‘sleep-thorn’ clearly also had physical form and appears in twoof the legendary sagas dated at least to the 15th century. In Hrólfs Saga Kraka, Danish king Helgiarrogantly imposes himself upon the warrior-queen Olof, announcing hisintention to marry her at once. ‘That evening there was hard drinking’, andwhen the king collapses into bed with her, ‘The queen took advantage of thisand pierced him with a sleep-thorn; and the minute they [his retinue] were allgone, up she got, shaved off all his hair, and daubed him with tar.’ I’mcheering the queen on through this, and feel she was completely justified, butsad to say the saga takes a different view: later on Helgi gets his revenge,and the queen retaliates... In Gongu-Hrolf’sSaga, treacherous Vilhjálm pierces the sleeping Hrólf with a sleep-thorn,cuts off his legs and kidnaps his bride-to-be. But the sleep-thorn falls outwhen Hrólf’s faithful horse Dulcifal rolls him over, the dwarf Mondul healsHrólf’s legs, and the hero pursues his enemy, who confesses and is hanged.

Whatever a sleep-thornmeant to medieval Icelanders, the Sigrdrifa/Brynhild story is remarkably closeto that of the best-known sleeper of all time, The Sleeping Beauty: after having incurred the anger of a powerfulsupernatural figure, a young woman is pricked by something sharp and falls intoa lengthy enchanted sleep, protected or imprisoned by a barrier no one cancross except the hero appointed finally to wake her. Jacob Grimm in his Teutonic Mythology notes that the German version of the tale, Dorn-röschen, means literally ‘Thorn Rose’, and adds: ‘The thorn-rose has a meaning here, for we still call a moss-like excrescence on the wild rosebush schlaf-apfel [sleep-apple]; so that the very name of our sleeping beauty contains a reference to the myth. [...] When placed under the sleeper's pillow, he cannot wake till it be removed.’ Maybe this throws some light on the mystery?

The Sleeping Beauty pricksher finger on a spindle, and when I was a child I assumed spindles must besharp. They aren’t, but the princess’s century-long sleep is guarded by animpenetrable hedge of brambles or briars – which of course possess thorns.

Inearlier versions a splinter of flax causes the enchanted sleep. In the 14thcentury French prose romance Perceforest(set in a pagan, pre-Arthurian world) a feast is given for the goddesses Venus,Lucina and Thetis to celebrate the birth of the lady Zellandine. Offendedbecause she has not been presented with a knife to cut her food, Thetis ordainsthat ‘from the first thread of linen that Zellandine spins from her distaff’, apiece of flax will pierce the girl’s finger and she will fall into a long sleep.How is flax sharp? Well, making linen thread involved soaking and drying theflax stalks; the dried strands were then pulled through a toothed comb whichsnapped the stiff outer sheaths into small shards which might easily becomeembedded under a fingernail. This happens to Zellandine, and also to Talia, thesleeping heroine of Giambattista Basile’s ‘The Sun, the Moon and Talia’published in the Pentamerone (1636).Yet another instance of a flax-caused sleep comes in ‘The Ninth Captain’s Tale’which has been attributed to the OneThousand and One Nights but does not belong there. Heidi Anne Heiner of thewonderful website Sur La Lune researched it, and found it was a Egyptianfolktale collected by the translator J.C. Marcius from an Egyptian cook‘sometime prior’ to 1883. It tells of a girl whose mother begged Allah for achild, even if she were to be so delicate that the scent of flax would chokeher. The girl is born ‘fair as the rising moon’, eventually learns to spin (toshow off her lovely fingers): a piece of flax gets stuck under her fingernailand she falls swooning to the ground. (Midori Snyder’s excellent take on thestory can be read here.)

There is no way todemonstrate lines of descent, but the Sigurd/Brynhild story was much recycledin northern Europe, with additions and deletions according to taste. An exampleis a Faroese ballad, Brynhild’s Ballad,collected in 1851 but tentatively dated to the 14th century (read it at this link), and it cleaves closely to Volsunga Saga. Informed by ‘wild birds’ that ‘fair is Brynhild Buđledaughter,/Sheyearns for your encounter,’ Sigurd rides to find her:

No one but brave Sigurd

entered Hildar-hill,

he jumped through smoke and fiery-fire,

he and his horse Grani.

[...]

There he saw that pretty maid

sleeping in her mail,

raised his good and sharpened sword,

andcut the mail wide open.

Brynhild welcomesSigurd, but suggests he should first ask her father’s permission to sleep withher. Sigurd replies that he doesn’t want to meet her father, and why should hein any case, since, ‘You are not exactly known/to take your father’s advice.’The ballad ends with Sigurd and the ‘mighty maid’ making love and conceivingtheir daughter Ásla.

A later version is a 16th century Danish balladSivard og Brynild in which Sivardrescues Brynild from a glass mountain (reminiscent of the fairytale ‘The Princess on the Glass Mountain’ widespread across Norway, Sweden, Poland andnorthern Germany). The ballad was translated by George Borrow and it was printedin 1913 for private circulation as TheTale of Brynild, and King Valdemar and His Sister: Two Ballads (read it here). It begins:

Sivard he a colt has got,

The swiftest ’neath the sun;

Proud Brynild from the Hill of Glass

In open day he won.

Unto her did of knights and swains

The very flower ride;

Not one of them the maid to win

Could climb the mountain’s side.

From the fairytaleopening things go downhill fast: Sivard succeeds, but instead of marrying Brynild,‘To bold Sir Nielus her he gave/To show him his regard’. Discovering that Sivardhas given a gold betrothal ring to the maiden Signelil, the angry Brynild demandsthat Sir Nielus bring her Sivard’s head: naturally it all ends in another bloodbath.

The lapse of time is implicitin these tales but not made much of. Sigrdrifa says, ‘Long I slept, long was Isleeping’ but we’re not told for howlong. The ‘valkyrie’ narratives focus on the tangled relationships, treachery andbloody tragedies that develop after the enchanted sleep has ended. There is notthat sense of confusion, loneliness, loss, and the discovery of a changed worldexperienced by many of the sleepers in my first post. Neither do any of the variousSleeping Beauties experience such emotions. In both Perceforest and the Pentamerone,the unconscious princess is raped by the prince and nine months later givesbirth, still sleeping – Zellandine to a baby boy, Talia to twins. Sucking at theirmother’s finger or breast, the babies suck out the splinter of flax, thuswaking her.

These busy, crowdedstories pay little or no attention to the lapse of time. Perrault’s ‘La Belleau Bois Dormant’ (1697) sanitised and gentrified the tale to suit hissophisticated saloniste audience: hisprince kneels ‘with trembling admiration’ at the bedside of the princess anddares not even kiss her. And the princess feels no shock at missing a century:her entire household shares her sleep, from her ladies-in-waiting down to thekitchen boy, dogs, horses and even the flies on the wall: her society wakeswith her. She doesn’t even miss her parents (not included in the slumber spell andnow long dead), and Perrault’s single gesture towards the length of time she’s sleptis an arch reference to the out-moded fashion of her dress. In the 1729 Englishtranslation by Robert Samber:

She was intirely dress’d, and very magnificently, but theytook care not to tell her, that she was drest like my great-grandmother, andhad a point band peeping over a high collar; she looked not a bit the lessbeautiful and charming for all that.

TheClassic Fairy Tales, Iona & Peter Opie.

Perrault adapts Basile’scontinuation of the story as follows: princess and prince marry. They have two children named Morning and Day.The prince becomes king and goes away to war; his mother, an ogress, orders thetwo children and their mother to be killed, and cooked for her to eat. The‘clerk of the kitchen’ hides the victims, substituting a lamb, a kid and a hind:the ogress discovers the trick and orders the three to be flung into a tub fullof poisonous snakes. At this moment the king returns, and the ogress jumps intothe tub herself, saving him the trouble of executing her. When I was a child Irather enjoyed this gruesome ending; nowadays I’m amused by the complacentcivility of the tale’s last sentence – ‘[The King] could not but be sorry, forshe was his mother, but he soon comforted himself with his beautiful wife, andhis pretty children.’ God forbid that any character of Perrault’s should suffer violent emotion.

From Sigrdrifa in the Poetic Edda to Perrault’s SleepingBeauty in the Wood, these tales are far less interested in the enchanted sleepitself, or how that lost time might affect the sleeper, than they are in thevarious dramatic events that take place once she wakes into a world which toall intents and purposes is no different from the one she fell asleep in.

With one exception:‘Dorn-röschen’ the Grimms’ version of the SleepingBeauty in the Wood. It's usually translated into English as ‘Little Briar Rose’: Iona and Peter Opie have unflatteringly compared this very shorttale with that of Perrault's lengthy one, stating that it ‘possesses little of the qualityof the French tale’. Well, I beg to differ. Perrault’s good Fairy engages in arelentless bustle of activity: she touches her wand individually to everyinhabitant of the castle to send them to sleep, she conjures up the hedge ofbriars ‘in a quarter of an hour’ – and the reader has barely time to drawbreath before the hundred years are done: in the very next paragraph ‘At theexpiration of a hundred years, the son of a King’ arrives, spots the towersfrom a distance and comes to investigate.

In contrast, this is how the Grimms’tale introduces the century of sleep:

But round about the castle there began to grow a hedge ofthorns, which every year became higher, and at last grew up close around thecastle and all over it, so that there was nothing of it to be seen, not eventhe flag upon the roof. But the story of the beautiful sleeping ‘Briar-rose’,for so the princess was named, went about the country, so that from time totime Kings’ sons came and tried to get through the thorny hedge into the castle.

But theyfound it impossible, for the thorns held fast together, as if they had hands,and the youths were caught in them, could not get loose again, and died amiserable death.

Afterlong, long years a King’s son came again into that country, and heard an oldman talking about the thorn-hedge, and that a castle was said to stand behindit in which a wonderfully beautiful princess, names Briar-rose, had been asleepfor a hundred years, and that the king and queen and the whole court wereasleep likewise.

There is room tobreathe. I love the slow, natural pace by which the hedge of thorns grows upand around the castle until it’s completely hidden; I love the way the story,now almost a legend, spreads around the countryside so that ‘from time to time’young princes come to try their luck, only to perish and be in turn forgotten;how at last ‘after long, long years’ the century of sleep is over and the time comesfor the spell to be broken. To compare ‘Little Briar Rose’ with ‘La Belle auBois Dormant’ is pointless: all the two stories have in common is the barebones of the plot. The Grimms’ tale is not witty or fashionable, it does notstrive either to amuse or to horrify, it’s not interested in characterisation. Rather,it places the hundred years’ sleep at the heart and centre of the tale and inits deceptive simplicity it is a meditation upon time.

In my next post I’ll belooking at folktales of kings sleeping under hills, sleeping armies, and, becausethe experience of lost time is so similar to that of enchanted sleepers, atsome of the many tales in which a seemingly short visit to fairyland or theotherworld turns out to have lasted years or centuries.

Picture credits:

The Sleeping Beauty by Edward Burne Jones - Manchester Art Gallery

Brunnhilde Asleep by Margaret Fernie Eaton, 1902

Sigurd Kills Fafnir and Sigurd Roasts Fafnir's Heart - from the Sigurd Portal

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flames by J.C. Dolman, 1909

The Hedge of Thorns by Errol le Cain, 'Thorn Rose' 1975

The Princess on the Glass Mountain by Theodor Kittelsen, 1857 - 1914

The Sleeping Beauty by Daniel Maclise - Hartlepool Museums & Heritage Service

The Prince and the Old Man by Errol le Cain, 'Thorn Rose', 1975

August 24, 2023

Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers #1

This is the first of a series of posts on enchanted sleep and sleepers in mythology,legends, the eddas, sagas, fairy tales and folklore. And to begin as as close tothe beginning as I can, the earliest tale of an enchanted sleep I know is that ofthe 7th or 6th century BCE philosopher Epimenides, recordedby Diogenes Laertius in his 3rd century CE Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Epimenides is far enough in thepast for any story about him to be ofdubious historicity, but we're told he was a Cretan of Knossos. As a young man:

He was sent by his father into the fields to look for asheep, turned off the road at mid-day and lay down in a certain cave and fellasleep, and slept there fifty-seven years; and after that, when he awoke, hewent on looking for the sheep, thinking that he had taken a short nap; but ashe could not find it, he went on to the field and there he found everythingchanged, and the estate in another person’s possession, and so he came backagain to the city in great perplexity, and as he was going into his own househe met some people who asked him who he was, until at last he found his youngerbrother, who had now become an old man, and from him he learned all the truth.

And when hewas recognised he was considered by the Greeks as a person especially belovedby the gods...

‘Beloved by the gods’ wouldbe down to the belief that Zeus was born in a cave on Crete, where his motherRhea hid from his father Cronos who had the bad habit of devouring his offspring. Epimenides’sleep was therefore presumed sacred or god-sent. He became a seer andphilosopher, and the Athenians called him to help them when the city wasafflicted by a plague in the year of the 16th Olympiad (596 BCE). Diogenesattributes various works to him, only one fragment of which has survived.

In the Bhagavata Purana (dated as written textfrom the 8th to 10th centuries CE but based on farolder oral traditions) King Mucukunda aids the devas, benevolent heavenly spirits, in their war against themalevolent asuras. When at last thedevas win, Indra their lord reveals to the king that an entire age of the worldhas passed, along with everyone he has known, but offers in recompense any giftwithin his power to give. The king, grief-stricken and weary, asks for unbrokensleep and for anyone who disturbs his slumber to turn to ashes. This Indragrants, and the king falls asleep in a cave.

Thousands of years later the godKrisha lures his enemy Kalayavana into the dark cave where, mistaking thesleeping Mucukunda for Krishna, Kalayavana kicks and wakes him. The king’sopening eyes burn him to ashes. Krishna next instructs Mucukunda on how tocleanse himself of sin, concluding, ‘O King, in your very next life you willbecome an excellent brahmana, thegreatest well-wisher of all creatures, and certainly come to Me alone.’ Onleaving the cave, Mucukunda notices that ‘the size of all the human beings,animal, trees and plants’ are far smaller now than before his long sleep.

A story from the BabylonianTalmud (c. 200 - 400 CE) concerns the sage Honi HaMe’agel (Honi theCircle-maker), a historical character of the 1st century CE. Thenickname was given him when during a drought, he drew a circle in the dustand told God that he would not step out of it until it rained. God obliged witha drizzle. Honi complained this was not enough; God sent a downpour. Honi then beggedfor a ‘moderate rain’, and God kindly reduced the flow. ‘Troubled throughout his lifeconcerning the meaning of the verse, “When the Lord brought back those thatreturned to Zion, we were like dreamers,”(Psalm 126)’, Honi wondered how it waspossible for seventy years (the period of the Babylonian exile) to be like a dream:‘How could anyone sleep for seventy years?’

One day Honi was journeying on the road and he saw a manplanting a carob tree. He asked, ‘How long does it take to bear fruit?’ The manreplied, ‘Seventy years.’ Honi then asked him, ‘Are you certain you will liveanother seventy years?’ The man replied, ‘I already found carob trees in theworld; as my forefathers planted those for me, so I too plant these for mychildren.’

Honi thensat down to eat, and sleep overcame him. As he slept, a rocky formationenclosed upon him which hid him from sight and he slept for seventy years. Whenhe awoke he saw a man gathering the fruit of the carob tree, and asked him,‘Are you the man who planted the tree?’ The man replied, ‘I am his grandson.’

When Honi returned, noone recognised him, or believed him when he tried to identify himself;distraught, he prayed for mercy and died. But the Jerusalem Talmud tells the storydifferently: ‘Near the time of the destruction of the [First] Temple,’ Honi setout to oversee his workers on a mountain, and went into a cave to shelter fromrain. There he fell asleep and remained for seventy years ‘until the Temple wasdestroyed and it was rebuilt a second time.’ At the end of this time he wokeand ‘saw a world completely changed.’ Vineyards had been replaced by olives,olives by fields of grain. On learning what had happened during his sleep hewent to the Temple and recited the verse: ‘When the Lord restored the fortuneof Zion, we were like those who dream.’

A 12th or 13thcentury CE manuscript owned by Kiel University (S.H. 8A 8vo) contains a similarand charming story. An unnamed monk was meditating on the psalm, ‘The merciesof the Lord I will sing forever’ (Psalm 89) when a beautiful little bird ledhim out of the cloister into a wood, where it flew into a tree and begansinging so wonderfully that the monk was entranced. When it had finished itssong and flown away he made his way back to the monastery, but the buildingswere utterly changed, no one knew him, and he was accused of being an imposter.On checking the records however, the current abbot realised that that the monkhad lived there two hundred years before.

Then the monk became aware that he was seized by God ...and that the sweet birdsong had delighted him throughout so many years that hecompletely forgot food, drink or sleep. From then on the monk was received withgreat veneration and retired within the same sacred monastery.

Though this monk doesn’tactually fall asleep, he certainly experiences the lapse of time in a very dream-liketrance. The story of the Seven Sleepers ofEphesus dates from at least the 6th century CE and is extant in numerous Islamic and Christian versions. The basic Christian story tells how, escaping persecution for their faith duringthe reign of the Emperor Decius, seven Christian youths take refuge in amountain cave where they pray and fall asleep. The Emperor has the cave sealedup with them inside. More than two centuries later the cave is opened by alandowner who wishes to stall cattle there, and the sleepers wake, imaginingonly a day has passed. Finding that Ephesus is now a Christian city, they telltheir story to the bishop, and die praising God.

I can’t resist addingthat in her children’s novel The SilverCurlew (an adaptation of the Norfolk folktale Tom Tit Tot) Eleanor Farjeon uses the Seven Sleepers in a spellcast by the Man in the Moon, Charlee, to rescue the heroine Poll from thewicked Spindle-Imp and his coven of Queer Things.

And now strange words seemed to swim through the pipe withthe tune, but whether Charlee was breathing them as he blew, or whether themoon-misty notes had a tongue of their own, Poll could not have said.

‘Malchus... ’ breathed the pipe. ‘Martinian ... Serapion...’

The Queer Things swayed like shadows, andRackny yawned.

The Spell of the Seven Sleepers (breathedthe pipe)

I put upon your peepers,

The sevenfold spell of the Sleepers

In Ephesus long gone.

Malchus ... Maximinian...

Dionysius ... John...

Constantine ... Martinian ...

And Serapion...

What did the strange spell mean? But what did it matter?The Queer Things were nodding now, their heads flopping from side to side,their heavy eyelids lolling up and down. [...] ‘Two hundred nine-and-twentyyears shall you lie there,’ murmured Charlee to the sleepers.

Leaving Eleanor Farjeon aside, almost all theseaccounts have four things in common: an implied intervention by a god or other religioussupernatural power; a cave; a world that has visibly changed since their sleepbegan; and an all-male cast who reap spiritual benefit from their experiences. Thereseemed nothing special about Epimenides before his oddly specific 57 year sleepin – it seems to have been assumed – Zeus’s cave: but afterwards he isgod-touched and becomes a philosopher important enough to be called upon by theAthenians in their hour of need. King Mucukunda assists Indra and his devasagainst the evil asuras, sleeps thousands of years in a cave and wakes to meetKrishna and become a Brahman. After pondering the meaning of a psalm, theJewish sage Honi sleeps for seventy years in either a ‘rocky formation’ whichgrows up around him or else in a mountain cave. Though not specified it’simplicit that God has sent this experience. Minus the cave, the same is truefor the monk who spends two centuries listening to the bird. ‘Seized by God’,he does not immediately die but is treated with ‘great veneration’ by theabbey. The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus slumber in their cave for two or threecenturies: on waking to find themselves in a Christian world, there is no morefor them to do but ‘praise God and die’.

Caves are dark, quietand secret places into which people might well disappear, and as such they recurfrequently in enchanted sleep narratives. There are more to come. In my nextpost I’ll be looking at some of the more malevolent occurrences of sleep-spells, such asthat cast on the valkyrie who pre-figures the Sleeping Beauty.

Picture credits

Seven Sleepers: Menologion of Basil II Wikipedia

King Mucukunda burns Kalayavana: Artist unknown

Bird (bluetit?): 13th C Medieval ms. British Library

August 3, 2023

'The Homestead Westward in the Blue Mountains' by Jonas Lie

Jonas Lie was a contemporary of Ibsen, born 1833 at Hvokksund,not far from Oslo, but spent much of his childhood at Tromsø, inside the ArcticCircle. He was sent to naval college, but poor eyesight made him unsuitedfor a life at sea, so he became a lawyer and began to write and publish poemsand novels which reflected Norwegian life, folklore and nationalism. Acollection of his short stories based on Norwegian and Finnish legends, 'Weird Tales from Northern Seas', was published in English in 1893. This isone of them. Other tales from the same collection can be found here, and here.

There was once afarmer’s son who was off to Moen for the annual manoeuvres. He was to be thedrummer, and his way lay right across the mountains. There he could practisehis drumming at his ease, and beat his tattoos again and again without makingfolks laugh – or having a parcel of small boys dangling after him like so manymidges.

Every time he passed a mountain homestead he beat hisrat-tat-a-tat to bring the girls out, and they stood and hung about and gapedafter him at all the farmhouses.

It was in the middle of the hottest summer weather. Hehad been practising his drumming from early in the morning, till he had grownquite sick and tired of it. And now he was toilng up a steep cliff, and hadslung his drum over his shoulder and stuck his drumsticks in his bandlolier.

The sun baked and broiled upon the hills; but in theclefts there was a coolness such as you get by a rushing waterfall. The hillswere covered in bilberries all the way up, and he bent down so often to pickwhole handfuls that it took him a long time to get to the top.

Then he came to a hilly slope where the ferns stood highand there were lots of birch bushes. It was so nice and shady there, hethought, and he couldn’t for the life of him resist taking a rest.

He took off his drum, put his jacket behind his head andhis cap over his face, and went off to sleep.

But as he lay dozing there, he dreamt that someone wastickling him under the nose with a grassblade. He quickly sat up, and was surehe heard someone laughing and giggling.

The sun by now had begun to cast oblique shadows, and fardown below, towards the valleys, lay the warm steaming vapours, creepingupwards in long drawn-out gossamer bands and ribbons of mist.

As he reached behind him for his jacket, he saw a snake,which lay and looked at him with such sharp quick eyes. But when he threw astone at it, it caught its tail in its mouth and rolled away like a wheel.

Again there was a laughing and sniggering among the bushes.

And now he heard it coming from some birch trees whichstood in such wonderful sunlight, for they were filled with the rain and finedrizzle of a waterfall. The waterdrops glittered and sparkled so that he couldhardly see the trees properly.

But something was moving about in them, and he couldswear it looked like a slim pretty girl, laughing and making fun of him, andpeeping at him from under her hand because of the sun, and her sleeves weretucked up.

And a moment later he glimpsed a dark blue blouse movingbehind the twigs. He was after it in an instant.

He ran and ran till he was almost ready to give up, butthen glimpsed a dress and a bare shoulder between a gap in the leaves. Off hepelted again as hard as he could, and just as he began to wonder if it was allimagination, he saw her cornered against the green bushes. Her hair had tornloose from her plaits from the speed with which she had flown through thebranches, and she looked back at him, pretending to be terribly frightened.

She was holding his drumsticks! She should pay for that,he thought, and off they ran again, she in front and he behind. But she keptturning around, laughing and jeering at him, and tossing and twisting her headso that it looked as if her long wavy hair were writhing and wriggling andtwisting like a serpent’s tail.

At the top of the hill she stopped by a fence and wavedthe drumsticks at him, laughing. Now he was determined to catch her, but beforehe could grab her she was through the fence, and he tumbled after her into theenclosure of a homestead.

“Randi, and Brandi, and Gyri, and Gunna!’ the girl criedup to the house.

And four girls came rushing down over the greensward. Thelast of them had a fine rosy face and heavy golden-red hair, and greeted himgraciously with downcast eyes, as if she was quite distressed that they shouldplay such naughty pranks with a strange young man.

She stood there quite shy and uncertain, poor thing! justlike a child who doesn’t know whether to say something or not. She sidlednearer till she was so close her hair almost touched him, and then she openedher blue eyes wide and looked straight at him.

Butshe had a frightfully sharp look in those eyes of hers.

“Bettercome with me and you shall have dancing – or are you too tired, lad?” cried agirl with blue-black hair and a wild dark fire in her eyes. She skipped up anddown and slapped her rump; she had white teeth and hot breath, and would havedragged him off with her.

“Tieyourself up behind first, black Gyri!” giggled the others, and immediately shelet the lad go and wobbled away backwards, twisting her hands behind her back.He couldn’t help staring: she writhed uncomfortably as if she were hidingsomething behind her and was suddenly so quiet.

Butthe fine bright girl whom he had chased, the prettiest of them all with theslender waist, began to laugh and tease him again. “Run as you like, you’llnever catch me,” she jibed and jeered, “nor your drumsticks either.” But thenher mood shifted right round and she flung herself on the ground, sobbing.She’d followed him all day, she cried, and never had heard any fellow who couldbeat a rat-tat-a-tat so well, nor ever seen a lad so handsome as he slept. “Ikissed you then,” said she, and smiled up at him sadly.

“Bewareof the snake’s tongue, lest it bite you! It caresses before it stings,”whispered the shy girl with the golden-red hair, stealing softly up. And all atonce the boy remembered the snake on the hillside, as slender and supple as thegirl who lay there weeping and mocking at the same time, with the same sharp,cunning eyes.

Now abent, clumsy little figure stuck her head in between them, and smiled bashfullyat him as if she knew and could tell him so much. Her eyes held a deep, inwardsparkle and over her face passed a sort of pale golden gleam, like the lastsunbeam fading over the hilltop. “At my place,” said she, “you shall hear musicsuch as no-one else has ever heard. You will hear all that sings and laughs andcries in the roots of trees, and in the mountains and in everything that grows,so that you will never care about anything else in the world.”

Thenthe boy heard a scornful laugh, and up on a rock he saw a tall, strong girlwith a gold band in her hair. With powerful arms she lifted a huge wooden horn,threw back her head and blew a blast as strong as the rock on which she stood:it sounded far and wide through the summer evening, and echoes rang to and froacross the hills.

Butthe pretty girl on the ground stuck her fingers in her ears and mimicked thesound and laughed and jeered. Then she peered up at him through her ash-blondhair and murmured, “If you want me, you’ll have to pull me up.”

“Shehas a strong grip for a girl,” thought he, as he did so – “But first you’llhave to catch me!” cried she, and raced for the house.

Suddenlyshe stopped, crossed her arms and looked straight into his eyes. “Do you likeme?” she asked.

He hadhold of her now, and couldn’t say no to that. “You’ll have to decide on this,father,” she shouted in the direction of the house. “The boy wants to marryme!” And she dragged him hastily towards the hut door.

Theresat a little, grey-clad old fellow with a cap on his head like a milk-can,staring at the livestock on the mountainside. He had a large silver jug infront of him.

“It’sthe homestead westward of the Blue Mountains that he’s after, I know,” said theold man, nodding his head with a sly look in his eyes.

“Isit, now?” thought the boy, understanding at last. Aloud he said, “It’s a greatoffer, I know, but surely too soon to decide. Down our way, the usual thing isto send go-betweens first of all, to see matters properly arranged.”

“You did send two ahead of you, and here theyare!” the girl said promptly, and she brandished his two drumsticks.

“Andwith us, it’s customary to look over the property first, however smart the girlmay be,” he added.

Thenshe shrank into herself and there was a nasty green glitter in her eyes –

“Haven’tyou run after me the livelong day, and courted me right down there in theenclosure, where my father could hear and see it all?” cried she.

“Mostpretty lasses hold back a bit,” said the boy, seeing that it wasn’t all love inthis wooing. Then she bent backwards in a complete circle and shot forward herhead and neck, and her eyes glittered. But the old fellow lifted his stick fromhis knees, and she stood upright again, merry and sportive as ever, with herhands in her silver girdle, and looked in his eyes and laughed, and asked if hewas one of those fellows who were afraid of girls?

“Ifyou want me, you might be run right off those legs of yours,” she joked, andskipped and curtseyed, making fun of him again. But behind her he saw hershadow whisking and frisking in circles on the grass like a long, coilingribbon.

Theyseemed in a great hurry to get him under their yoke, he thought, but a soldieron his way to the manoeuvres is not to be married off-hand. “I came here for mydrumsticks, not looking for a wife, and I’ll thank you to hand them back.”

“Notso fast. Look about you first, young man,” said the old fellow, and as hepointed with his stick the drummer boy saw mountain pastures full of dun cowsgrazing, with cow-bells clonking and the prettiest of milkmaids carrying brightcopper buckets. There was wealth here for sure.

“Maybethis dowry of mine in the Blue Mountains doesn’t seem much to you,” said thegirl, sitting down beside him. “But we’ve four such saeter as this, and what I inherit from my mother is twelve timesas large.”

Butthe drummer had seen what he had seen. They were rather too anxious to settlethe property upon him, he thought. So he declared that in such a seriousmatter, he needed a little time for consideration.

Thelass began to cry, and take on, and accused him of trying to fool a poor innocentyoung thing and pursue her, and drive her out of her wits. She had trusted him,she said, and fell a-howling and rocking with her hair all over her eyes, tillat last the drummer began to feel quite sorry for her and almost angry withhimself. But when she looked at him with those sharp, glinting eyes, it was asif he saw again the snake under the birch trees down on the hillside when itcurled into a hoop and rolled away.

Thenshe reared up hissing, and a long tail whisked about behind her from underneathher skirts. “You won’t get away from me like that!” she shrieked. “I’ll haveyou dragged in shame from parish to parish!” And she called her father.

Thedrummer felt a grip on his jacket. He was lifted right off his legs and chuckedinto an empty cow-house, and the door was shut behind him.

Therehe stood and had nothing to look at but an old billy-goat through a crack inthe door, who had odd yellow eyes and looked very much like the old fellow, anda sunbeam through a little hole, which crept higher and higher up the blankstable wall till late in the evening, when it went out altogether.

Buttowards night a voice outside said softly, “Boy! boy!” and in the moonlight hesaw a little shadow cross the hole. “Hush! the old man is sleeping outside on theother side of the wall,” it said.

Herecognised the voice: it was the golden-red one who had seemed so shy.

“Allyou need to do is say you know Snake-eyes has had a lover before, or theywouldn’t be in such a hurry to get her off their hands with a dowry. Thehomestead westward in the Blue Mountains is mine, so tell the old man that itwas me, Brandi, you were after all the time. Hush, here he comes,” shewhispered, and whisked away.

But ashadow again fell across the little knot-hole in the moonlight, and theduck-necked one peeped in at him. “Boy, are you awake? Snake-eyes will make afool of you. She’s spiteful, and she stings. But the homestead westward in theBlue Mountains is mine, and when I play there the gates under the high mountainsfly open and show the way to the nameless powers of nature. Just say it was I,Randi, you were running after, because you love her songs. Hush, the old man isstirring by the wall!” – and she was gone.

Alittle afterwards nearly every bit of the hole was darkened, and he recognisedthe dark one by her voice.

“Boy,boy!” she hissed. “I had to tie my skirts up behind today, so we couldn’t godancing the Halling-fling. But thehomestead in the Blue Mountains is lawfully mine, so tell the old man it wasmadcap Gyri you were running after today, because you love dancing jigs and hallings.” Then she clapped her handsand was frightened she might have awakened the old man. And she was gone.

Butthe lad sat inside there and watched the thin summer moon rise, and thought thatnever in his life had he been in such trouble. And from time to time he heardscraping and snorting against the wall outside, and knew it was the old fellowwho lay there and kept watch over him.

“Areyou there, boy?” said another voice at the peephole.

It wasthe sturdy girl who had planted herself so firmly on the rock.

“Forthree hundred years I have been blowing the langelurhere in the summer evenings. Everything you see here is illusion and fairyglamour: many a man has been fooled by it, but I won’t see the other girlsmarried before me. Rather than let one of them have you, I’ll set you free. Nowlisten! When the sun is hot and high the old man will get frightened and crawlinto the shadows. Then’s your chance. Shove the door open hard and run, jumpover the fence, and you’ll be rid of us.”

Assoon as the sun began to burn, the drummer followed her advice. He cleared thefence in one good bound and fled, and in no time he was down in the valleyagain. He could hear the horn calling distantly in the mountains. But he slunghis drum over his shoulder and set off to the manoeuvres at Moen. And neveragain did he beat his drum to call out the lasses from the farmsteads, for fearhe should find himself westwards in the Blue Mountains before his time.

Illustration by Laurence Housman

July 27, 2023

The Pilot’s Ghost Story

St Ives Harbour Fish Market: courtesy of https://www.cornwalls.co.uk

St Ives Harbour Fish Market: courtesy of https://www.cornwalls.co.ukAnother tale from RobertHunt’s ‘Popular Romances of the West ofEngland, or The Drolls, Superstitions and Traditions of Old Cornwall’ (thirdedition, 1896) was told orally to Charles Taylor Stephens, a poet and ‘sometime ruralpostman from St Ives to Zennor’. Hunt employed Stephens to collect stories fromremote villages on the assumption that people would more readily tell tales tothe friendly postman than to a stranger.

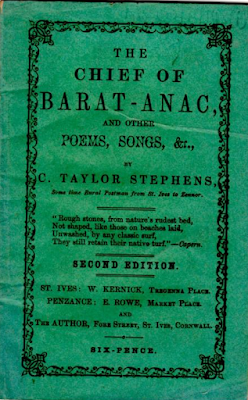

C. Taylor Stephens' book of poems

C. Taylor Stephens' book of poemsThis particular story was told toStephens by a pilot whose job it was to meet ships and guide them into port. Inthis tale he guides the sloop Sallyfrom St Ives to Hayle, approximately five miles up the coast.

Robert Hunt often altered stories‘from the vernacular – in which they were for the most part related – intomodern language’, but says of this one, ‘I prefer giving this story in thewords in which it was communicated. For its singular character, it is a ghoststory well worth preserving.’

Here it is, in what is (mostly) the pilot's own words.

Just seventeen years since*, Iwent down on the wharf from my house one night [between] about twelve and onein the morning, to see whether there was any ‘hobble,’* and found a sloop, the Sally of St Ives (the Sally was wreckedat St Ives one Saturday afternoon in the spring of 1862) in the bay, bound forHayle.

When I got by the White Hartpublic-house, I saw a man leaning against a post on the wharf – I spoke to him,wished him good morning, and asked him what o’ clock it was, but to no purpose.I was not to be easily frightened, for I didn’t believe in ghosts, and findingI got no answer to my repeated inquiries, I approached close to him and said,‘Thee’rt a queer sort of fellow, not to speak; I’d speak to the devil, if he wereto speak to me. Who art a at all? thee’st needn’t think to frighten me: thatthee wasn’t do, if thou wert twice so ugly; who art a at all?’

He turned his great ugly faceon me, glared abroad his great eyes, opened his mouth, and it was a mouth sure ’nuff. Then I sawpieces of sea-weed and bits of sticks in his whiskers; the flesh of his face andhands were parboiled, just like a woman’s hands after a good day’s washing.Well, I did not like his looks a bit, and sheered off; but he followed close bymy side, and I could hear the water squashing in his shoes every step he took.

Well, I stopped a bit, andthought I would be civil to him, and spoke to him again, but no answer. I thenthought I would go to seek for another of our crew, and knock him up to get thevessel, and had got about fifty or sixty yards, when I turned to see if he wasfollowing me, but saw him where I left him.

Fearing he would come afterme, I ran for my life the few steps that I had to go. But when I got to thedoor, to my horror there stood the man in the door, grinning horribly. I shooklike an aspen leaf; my hat lifted from my head; the sweat boiled out of me.What to do I didn’t know, and in the house there was such a row, as ifeverybody was breaking up everything. After a bit I went in, for the door wason the latch [ie: not locked] – and called the captain of the boat, and gotlight, but everything was all right, not had he heard any noise.

We went out aboard of the Sally and I put her into Hayle but Ifelt ill enough to be in bed. I left the vessel to come home as soon as Icould, but it took me four hours to walk two miles, and I had to lie down inthe road, and was taken home to St Ives in a cart; as far as the Terrace* fromthere I was carried home by my brothers and put to bed. Three days afterwardsall my hair fell out as if I had had my head shaved. The roots, and about halfan inch from the roots, being quite white. I was ill six months, and doctor’sbill was £4, 17s. 6d. for attendance and medicine. So you see I have reason tobelieve in the existence of spirits as well as Mr Wesley* had. My hair grewagain, and twelve months after I had as good a head of dark-brown hair as ever.

Notes:

* ‘Just seventeen yearssince’: Stephens, to whom it was told,died in 1865, so the events of the story must have occurred by 1848 or earlier.

* ‘hobble’ – dialectword a Cornish glossary says is ‘the share each person received when the vessel was brought in - or perhaps when the catch was sold.’ The sense here seems to be ‘a share of any work to do’?

* ‘TheTerrace’ is a street in St Ives with views over the bay.

* The preacher John Wesley believedin the existence of ghosts and other spirits.

July 18, 2023

Jorinda and Joringel: Owls and Flowers

There’s a story in The Mabinogionabout a girl who is changed into an owl. The magicians Gwydion and Math apMathonwy create her out of flowers for Lleu Llaw Gyffes whose mother has cursedhim never to have a human wife. They take ‘the flowers of the oak, and theflowers of the broom, and the flowers of the meadowsweet, and from those theyconjured the fairest and most beautiful maiden that anyone had ever seen. Andthey baptised her in the way that they did at that time, and named herBlodeuedd.’

Deed done, cursecircumvented: Blodeuedd is presented to Lleu. Nobody has asked her what she wants, however, and one day whenLleu is away she meets the handsome young man Gronw Pebr. The two fall in love andplot to murder Lleu so that they can be together. At the moment of his deathhowever, Lleu is transformed into an eagle. Math restores him to his humanshape, and Gwydion pursues Blodeuedd and transforms her into an owl:

‘[Y]ouwill never dare show your face in daylight for fear of all the birds. And allthe birds will be hostile towards you. … You shall not lose your name, however,but shall always be called Blodeuwedd.’ Blodeuweddis ‘owl’ in today’s language. And for that reason the birds hate the owl:and the owl is still called Blodeuwedd.

Commenting on the tale,Sioned Davies explains that the name ‘changes from Blodeuedd (‘flowers’) to Blodeuwedd(‘flower-face’) to reflect the image of the bird.’The white face of the barn owl does in fact look like two huge white daisies crushedtogether.

Blodeuedd is a girlmade from flowers and turned into an owl. In the Grimms’ fairy tale Jorinda and Joringela girl is turned into a bird by an owl-woman – and released by the touch of aflower. Here’s what happens: In the middle of a dark forest an ancient castle isinhabited by an old woman who turns into a cat or a night-owl by day, assumingher own form only when evening comes. She lures wild birds and beasts to her,and kills and eats them. Further:

If anyone came within one hundred paces of thecastle he was obliged to stand still and could not stir from the spot until shebade him be free. But whenever an innocent maiden came within this circle, shechanged her into a bird and shut her up in a wickerwork cage, and carried thecage into a room in the castle. She had about seven thousand cages of rarebirds in the castle.

A betrothedyoung couple, Jorinda and Joringel, walk into the forest in order to be alonetogether. Though Joringel warns his sweetheart that they must take care not to strayclose to the castle, everything should be wonderful in this glowing sunset wood– ‘It was a beautiful evening. The sunshone brightly between the trunks of the trees into the dark green of theforest, and the turtledoves sang mournfully upon the beech trees.’ But forsome reason the young lovers feel sorrowful – ‘as sad as though they were aboutto die.’ In this strange mood,

[T]hey looked around them,and were quite at a loss, for they did not know which way they should go home.The sun was still half above the mountain and half under.

Joringellooked through the bushes, and saw the old walls of the castle close at hand. Hewas horror-stricken and filled with deadly fear. Jorinda was singing:

“Mylittle bird with the necklace red

Singssorrow, sorrow, sorrow.

He singsthat the little dove must soon be dead.

Singssorrow, sor– jug, jug, jug.”

The sun has set, Jorinda has been changed into a nightingale, and ‘a screechowl with glowing eyes flew three times round about her, and three times cried‘to-whoo, to-whoo, to-whoo!’’ Unable to speak or move, Joringel sees the owlfly into a thicket and emerge as a crooked old woman ‘with large red eyes’ whocatches the nightingale and takes it away.

Later that evening theenchantress returns later and releases Joringel with the cryptic words, ‘Greetyou, Zachiel. If the moon shines on the cage, Zachiel, let him loose at once.’ (Zachielis probably the angel Zakiel mentioned along with Michael, Gabriel and other angels ina spell for ‘binding the tongue’ in the Syriac ‘Book of Protection’, acompendium of charms and incantations dating in manuscript form from the early1800s though probably much older.) The old woman refuses to release Jorinda andtells Joringel he will never see his sweetheart again. Joringel goes sadly away,but while working as a shepherd in a nearby village he dreams of a blood-redflower containing a dew-drop as big as a pearl, with which he can open thedoors of the castle and the cage. After a nine-day search he finds the flower, returnsto the castle and sets Jorinda and all the other maidens free.

The Grimm brothers tookthis tale almost verbatim from the deeply Romantic semi-fictional autobiographyof Johann Heinrich Jung, 'The Life ofHeinrich Stilling', published in 1777. Writing throughout in the third person, Jungtells how one day, out in the forest gathering firewood, the eleven-year-oldHeinrich asks his Aunt Marie for a story. ‘“Tell me, aunt, once more,” saidHeinrich, “the tale of Joringel and Jorinde.”’ His aunt is happy to oblige andwhen she has finished, Heinrich sits ‘as if petrified – his eyes fixed and hismouth half-open. “Aunt!” said he, at length, “it is enough to make one afraidin the night!” “Yes,” said she, “I do not tell these tales at night, otherwiseI should be afraid myself.”’