Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers #3

Probably the best-knownenchanted sleeper after the Sleeping Beauty is Rip van Winkle. A lazybonesliving in the Catskill Mountains, he prefers hunting to hard work. Out with hisdog one evening, he helps a strange little fellow to carry a keg up themountain. They arrive at ‘a hollow, like a small amphitheatre, surrounded byperpendicular precipices, over the brinks of which impending trees shot theirbranches, so that you only caught glimpses of the azure sky and the brightevening cloud.’

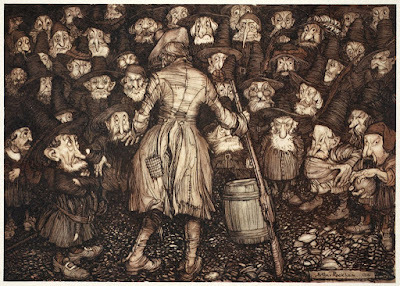

Within this cave-likestructure a number of ‘odd-looking personages’ dressed in old-fashioned clothesare playing at ninepins in complete silence except for the noise of the rollingballs which raise thunderous echoes. Stopping their play, they stare at Rip‘with such fixed, statue-like gaze, and such strange, uncouth, lack-lustrecountenances, that his heart turned within him and his knees knocked together.’Rip nervously serves the little men drinks from the keg, after which theyreturn to their game; he tries the beverage himself, and falls asleep fortwenty years.

Rip is the invention ofWashington Irving who published the tale in 1819, but he based it heavily on aGerman folktale ‘Peter Klaus’. Peter is a goatherd from Sittendorf who pastureshis herd on the Kyffhäuser, a prominent hill south-east of the Harz mountains.Following a stray goat into a cave, Peter finds it eating oats mysteriouslyshowering from the roof. He hears horses neigh and stamp overhead, and a youngman beckons him up steps into a ‘deep dell, inclosed by steep craggyprecipices’ where ‘on a well-levelled, cool grass plot’, twelve knightssilently play skittles and sign for him to set up the fallen ones. Peter obeys:then growing bolder, drinks wine from a nearby pitcher and falls asleep ony towake stiff and old, with a beard a foot long. Descending the mountain to Sittendorf,he finds his house a ruin and recognises no one until a young woman tells himthat Peter Klaus was her father – ‘It is now twenty years and more since wesearched for him a whole day and night on the Kyffhäuser. ... I was then sevenyears old.’

Relevant to this tale is thelegend that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122-1190) sleeps in acave under the Kyffhäuser with six of his knights. He sits at the head of astone table and has been there so long that his great red beard has grown rightthrough the stone. This legend haunts the story of poor Peter Klaus andexplains his fate. Anyone local to the Kyffhäuser would know at once that thecave, knights and horses belonged to Barbarossa. It’s generally a riskybusiness to enter the cave of a sleeping king and his army, especially if oneof the sleepers stirs and asks ‘Is it time?’ (The best plan is to answer, ‘No,sleep on!’ and flee.) Hugh Miller, in his 1891 book Scenes and Legends of the North of Scotland, relates how a manentered the Dropping Cave of Cromarty and fuelled by alcohol, blew a blast on abugle he found lying beside a vast sarcophagus, disturbing an unknown warrior:

Thecover heaved upwards, disclosing a corner of the chasm beneath; and a handcovered with blood and of such fearful magnitude as to resemble only theconceptions of Egyptian sculpture, was slowly stretched from the darknesstowards the handle of the mace. Willie’s resolution gave way, and flinging downthe horn he rushed toward the passage. A yell of blended grief and anger burstfrom the tomb, as the immense cover again settled over it.

So far as I know, WashingtonIrving had no similar legend of the Catskills to apply to Rip van Winkle, buthis odd little men are sufficiently fey to be disturbing. The fairiestraditionally dressed in old-fashioned clothes, and in Arthur Rackham’sillustrations to Rip van Winkle thelittle men look very like goblins.

Characters like Rip fallasleep in consequence of having accidentally strayed into what might be termeda supernatural danger zone. In fact, the ‘supernatural lapse of time’ – thephrase coined by Edwin Sydney Hartland in TheScience of Fairytales (1890) – experienced by Rip and the sleeping PeterKlaus is very similar to that of those who visit fairyland for what seems a fewdays or hours, but find on their return that years or centuries have passed.

The 12th centurycourtier Walter Map tells of King Herla of the Britons, who goes to the weddingof a pygmy fairy king (half goat, half man) in underground halls of greatsplendour. After the wedding, the pygmy king loads Herla and his retinue withgifts including a small hound for Herla to carry on his saddle, warning thatneither he nor any of his men should dismount before the dog leaps down.Emerging into the open, Herla asks an old shepherd for news of his queen, butthe shepherd can hardly understand him. ‘You are a Briton and I a Saxon... longago, there was a queen of that name ... who was the wife of King Herla; and he,the story says, disappeared in company with a pygmy at this very cliff and wasnever seen on earth again.’ Forgetting the fairy king’s warning, some ofHerla’s men jump from their horses and crumble instantly to dust: and Herlastill rides the hills with the rest of his company, for the little dog has notyet leapt down.

The same prohibition wasplaced on Oisin, son of the Irish hero Finn, who married Niamh of the GoldenHair, daughter of the King of the Country of the Young and went away with herto that country, riding over the sea. After spending three years there he longedto see his father Finn again. Niamh gave him permission, and her horse, and warnedhim on no account to dismount or put foot to the ground. Of course he forgot.

Some say it was hundreds of years he was in that country,and some say it was thousands of years he was in it; but whatever time it was,it seemed short to him. And whatever happened to him through the time he wasaway, it is a withered old man he was found after coming back to Ireland, andhis white horse going away from him, and he lying on the ground.

Gods and Fighting Men, Book XI, Ch 1, tr. Lady Augusta Gregory

Oisin leaves the land ofeverlasting youth and returns to mortal soil, where the weight of centuries fallsand crushes him. In a dialogue with St Patrick he describes himself as ‘an oldman, weak and spent, without sight, without shape, without comeliness, withoutstrength or understanding, without respect.’ Patrick tries to convert him, butOisin has the last word:

'Oisin and Patrick' by PL Lynch

'Oisin and Patrick' by PL Lynch‘It is a good claim I have on your God, to be among hisclerks the way I am; without food, without clothing, without music, withoutgiving rewards to peers. Without the cry of the hounds, without guardingcoasts, without courting generous women; for all that I have suffered by thewant of food, I forgive the King of Heaven in my will.

‘My story is sorrowful. The sound of yourvoice is not pleasant to me. I will cry my fill, but not for God, but becauseFinn and the Fianna are not living.’

Godsand Fighting Men, Book XI, Ch V, tr. Lady Augusta Gregory

Or are they? In most accountsOisin dies; his grave, like Arthur’s, is located in various places –Antrim, Armagh, even Scotland – but forFinn and the Fianna ‘there are some say he never died, but is alive in someplace yet.’

And one time a smith made his way into a cave he saw, thathad a door in it, and he made a key that opened it. And when he went in he sawa very wide place, and very big men lying on the floor. And one that was biggerthan the rest was lying in the middle, and the Dord Fiann [Finn’s war-horn] beside him, and knew it was Finn and the Fiannawere in it.

And thesmith took hold of the Dord Fian, and ... blew a very strong blast on it ...And at the sound, the big men lying on the ground shook from head to foot. Hegave another blast then, and they all turned on their elbows. And great dreadcame on his when he saw that, and he threw down the Dord Fian and ran from thecave and locked the door after him, and threw the key into the lake. And heheard them crying after him, ‘You left us worse than you found us.’ And thecave was not found again since that time.

But somesay the day will come when the Dord Fian will be sounded three times, and thatat the sound of it the Fianna will rise up as strong and well as ever theywere...

Godsand Fighting Men, Book X, Chapter III, tr. Lady Gregory

(If you want to hear what theDord Fian might have sounded like, clickthis link.)

Versions of this tale-typeknown as ‘the king asleep in the mountain’ are found worldwide, and I can’tresist sharing my recent discovery – recent to me, though known to many – ofperhaps the earliest European ‘sleeping king’ narrative. It’s recorded by the 1st/2ndcentury CE Greek historian and philosopher Plutarch, who attributes it toDemetrius the Grammarian ‘travelling home from Britain to Tarsus’. In onedialogue ‘On the Silence of the Oracles’, Demetrius tells how on one of themany islands lying around Britain, Cronus (Saturn) lies sleeping, guarded bythe hundred-handed monster Briareus: ‘and round about him are many demigods asattendants and servants.’ Anotherdialogue ‘On the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon’ elaborates thisaccount:

A run of five days off from Britain as you sail westward,three other islands equally distant from it and from one another lie out fromit in the general direction of the summer sunset. In one of these, according tothe tale told by the natives, Cronus is confined by Zeus, and the antiqueBriareus, holding watch and ward over those islands and the sea that they callthe Cronian main, has been settled closebeside him.

[...]

ForCronus himself sleeps confined in a deep cave of rock that shines like gold –the sleep that Zeus has contrived like a bond for him – and birds flying inover the summit of the rock bring ambrosia to him, and all the island issuffused with fragrance scattered from the rock as from a fountain; and thosespirits mentioned before tend and serve Cronus, having been his comrades whattime he served as king over gods and men.

I wonder if Demetrius reachedthe island on which ‘Cronus’ sleeps by circumnavigating Britain anti-clockwise,and sailed down the west coast from the north?

[T]hosewho survive the voyage first put in at the outlying islands [...], and see thesun pass out of sight for less than an hour over a period of thirty days, – andthis is night, though it has a darkness that is slight and twilight glimmeringfrom the west [...] and then winds carry them to their appointed goal.*

This description of the longnorthern summer days and short nights convinces me that Demetrius really did sail in northern waters and picked up information and stories ‘according tothe tale told by the natives.’ It’s tantalising! What Celtic god or hero seemedto Demetrius’ Greco-Roman mind, the equivalent of Cronus/Saturn, father ofZeus?

Whoever that might be (incidentally, a friend has reminded me of CS Lewis's giant Father Time, who sleeps in a cave under Narnia until Time ends – Cronus is a personification of time, and you can bet Lewis knew his Plutarch) theroll-call of sleeping heroes includes figures named and unnamed, legendary andhistorical: Finn, Barbarossa, Charlemagne, Ogier the Dane, and of course there’sArthur.

Some men say in many parts of England that King Arthur isnot dead, but had by the will of Our Lord Jesu into another place; and men saythat he shall come again, and he shall win the holy cross. I will not say thatit shall be so, but rather I will say, here in this world he changed his life.But many men say there is written upon his tomb this verse: HIC IACET ARTHURUS,REX QUONDAM REXQUE FUTURUS.

Le Morte D’Arthur, Book XXI, chapter 7

Malory’s Arthur is taken awayin a barge to ‘the isle of Avilion, to heal me of my grievous wound’, butEngland, Wales and the Borders are full of tales of the king and his knightssleeping hidden under a hill. Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpsonsummarize the stories in their comprehensive guide to England’s legends, The Lore of the Land.

In several places, including Sewingshields, Northumberland,and Richmond Castle, Yorkshire, it is said that a man finds a secret doorway ina hillside, leading to a cavern where Arthur and his knights sleep, surroundedby weapons and treasures, which may include some significant objects, such as asword, a horn, or a bell. [...] The sleepers begin to stir, and the intruderpanics and flees. He... can never find the hidden entrance again; meanwhile,Arthur and his knights return to their enchanted sleep, for the time for theirreturn has not yet come. Other stories, collected in the late 19thcentury, say Arthur and his court dwell inside the hill-fort of Cadbury Castle,Somerset; on the nights of full moon they emerge on horses shod with silver.

The Lore of the Land, p310

It’s easy to see how the ‘kingunder the hill’ tales bleed into fairyland. The Cadbury legend makes Arthur andhis silver-shod steeds sound very like the Seelie Court or Faerie Rade. Otherthan their regular full-moon wandering, the rest of the time do they sleep? TheIrish Earl Gerald of Mullaghmast, a master of the black arts, sleeps with hiswarriors in a cave under the Rath ofMullaghmast. Once every seven years he wakes and ‘rides around the Curragh of Kildareon a horse whose silver shoes were half an inch thick’ when he fell asleep.When they are worn ‘as thin as a cat’s ear, a miller’s son with six fingers oneach hand will blow his trumpet’ and the Earl and his men will wake and rideout against the English.

Perhaps Tolkien remembered thesestories when he sent Aragorn into the Dwimmerberg, the Haunted Mountain, tosummon the King of the Dead and the shadow army which slept there. Once theyhave fought on his side against the hordes of Mordor, Aragorn holds the dead king's ancient oath fulfilled, and the shadow army dissolves like mist.

Kings or heroes, all male,lying asleep in caves or underground: like the tales I explored in my firstpost and unlike those of the second, these narratives focus on the lapse oftime and its effect, but there is a difference. King Mucukunda, the SevenSleepers, Honi the Circle-Drawer and their ilk were all put to sleep by somedivinity – and for a purpose. And their experiences were ultimately positive:they received divine lessons or blessings and departed this life in peace. Thatis not the case in these tales. Nothing St Patrick says can comfort Oisin,whose lament expresses not only the personal, emotional cost of the lost years,but fierce grief for a vanished way of life and the age of heroes.

What causes this difference? Whiledeities can be expected to look after you, it is dangerous to trespass into theOtherworld of the Sidhe, where humanity does not belong, and even moredangerous if you taste food or drink there. The fair folk don’t age like us.Even Aragorn in The Lord of the Ringswill grow old long before his elven bride, Arwen.

The women in my second post donot sleep in caves. They sleep in the open air on hilltops, or in the morecivilised environment of hall or castle. And they do not age. During hercentury of sleep the Sleeping Beauty does not age at all, neither does thevalkyrie Sigrdrifa in the Poetic Edda,or Brynhild in Volsunga Saga: theywake from their enchantments as active, young and beautiful as when they fellasleep. But whether by gradual natural process or sudden dynamic change, PeterKlaus, Rip van Winkle and Oisin do age. They sleep for decades and wake alreadyold, or discover they’ve skipped a huge span of years and instantly wither –some into dust.

A tale in The Celtic Magazine of November 1887 tells how a young bridegroomleaving the church after his wedding was stopped by ‘a tall dark man’ who askedhim to come around the back of the building with him for a quick word, and askedhim to stand still till a small piece of candle he held in his hand should burnout. The bridegroom complied; it burned for two minutes, then he ran after hisfriends. They were out of sight, so he asked a man cutting turf if he had seenthe wedding party go by. The turf-cutter shook his head: ‘Not for a long timepast. What did you suppose the date of the wedding to be?’ The bridegroom gavea date two hundred years in the past. And the turf-cutter told him, ‘Mygrandfather had a tale his grandfather told him, of a bridegroom whodisappeared on the day of his wedding.’ ‘I am that bridegroom!’ the young mancried, and fell as he spoke into a small heap of earth.

Maybe that’s the best way togo? For those who survive for a while, the sense of loss is devastating. In Ripand Peter Klaus’s case, meeting a grown daughter and grandchild offers partialconsolation, but there is no recovering lost youth.

As for the ones who grieve forthe lost years but do not die, one thing is clear: they are divorced from theflow of time. They cannot grow or change. Some spend the endless years likeKing Herla who ‘holds on his mad course with his band in eternal wanderings, withoutstep or stay’. This is not like sleep, which indeed doesn’t feature in Herla’stale, but it speaks of an inability to rejoin or ever to take part again innatural life. Unable even to dismount from their steeds, Herla and his troopare forever homeless, ‘blown in restless violence round about the pendantworld’, to quote Shakespeare. And the kings and their knights lie in theircaves in suspended animation, neither dead nor truly alive, waiting for the daywhen they will be needed, will be relevant again. Alas, it is a day that may nevercome, for – Aragorn excepted – in no story has any intruder ever wanted to wakethem.

* Charles William King, whose1908 translation this is, tells us that Demetrius was sent to the islands ofBritain by Trajan (who was emperor from 98 – 117 CE) and suggests that one of theislands may be Anglesey – ‘the focus of Druidism’ – since only ‘holy men’ aresaid to inhabit it. Could there still have been druids on Anglesey at the endof the 1st century CE? I suppose it’s possible, even after the 60-61 CEinvasion by Suetonius Paulinus (busily burning the sacred groves just beforenews of the Boudiccan rebellion reached him), and that of Agricola in 77 CE.Druidism might well have hung on for quite a while, as the account goes on toexplain that the cave of Cronus is a centre for oracles and prophecies described as ‘the dreams of Cronus’.

Picture credits

Sleeping King Arthur: illustration by Eric Fraser for 'English Legends' by Henry Bett

'They stared at him': illustration to Rip van Winkle by Arthur Rackham

Barbarossa in the Kyffhauser: artist unknown

Oisin and Niamh by Richard Hook: see https://littleisobel.com/home/2011/10/12/richard-hook-great-folk-tales-of-old-ireland/

Oisin meets Patrick:

The Death of King Arthur: painting by John Garrick, 1862

To the Stone of Erech: by Inger Edelfeldt

Rip van Winkle: by Arthur Rackham