Enchanted Sleep and Sleepers #2

My last post concerned anumber of enchanted sleepers, all male, whose lengthy slumbers – howeverinconvenient – were almost entirely benign, awarded by the gods or God in orderto save, enlighten or confer spiritual blessings upon them; and sometimes allthree, for even when the sleeper awakes only to die shortly afterwards, he doesso in a state of holiness or grace. This time I’m looking at enchanted sleepnarratives involving women, in which the motivation of the instigator is consistently malign and the dénoument is often far from satisfactory.

Sigurd kills Fafnir...

Sigurd kills Fafnir...

The poems known as the Poetic Edda are preserved in manuscriptsdating back to the 13th century CE but derive from much older oraltradition. One of them, the ‘Lay of Fafnir’, tells how the hero Sigurd slaysthe dragon Fafnir, cuts out and cooks the heart for the dragon’s treacherous humanbrother Regin, and tests it with his finger to see if it’s done.

...and licks the blood from his thumb

...and licks the blood from his thumbAfter lickingthe blood he understands the speech of birds – nuthatches – which warn him tokill Regin, and direct him to the sleeping valkyrie Sigrdrifa. In the wonderfultranslation by Carolyne Larrington:

There is a hall on high Hindarfell

outside it is all surrounded with flame;

wise men have made it

[...]

I know on the mountain the battle-wise one sleeps

and the terror of the linden [fire] plays above her;

Odin stabbed her with a thorn

[...]

Young man, you shall see the girl under the helmet,

who rode away from battle on Vingskornir.

Sigdrifa’s sleep may not be broken,

by a princely youth, except by the norns’ decree.

ThePoetic Edda, tr. Carolyne Larrington, OUP

Sigurd kills Regin,loads his horse Grani with Fafnir’s treasure and rides off. The story continuesin ‘The Lay of Sigrdrifa:’ Sigurd climbs ‘high Hindarfell’ and finds thevalkyrie lying asleep surrounded by flames and a rampart of shields. Crossingthis barrier, Sigurd lifts off her helmet and with his sword Gram cuts away themail corselet which is biting into her flesh. Waking, she explains that inrevenge for the killing of a king to whom he had promised victory, Odin‘pricked her with a sleep-thorn’ and told her that she would never again bevictorious in battle, but should marry instead. At Sigurd’s request, Sigrdrifaconfers wisdom on him by teaching him many runes. The manuscript then breaksoff, but the exact same story is told in VolsungaSaga about the valkyrie Brynhild, who explains on waking:

In the battle I struck down Hjalmgunnar, and in retaliationOdin pricked me with the sleep thorn, said I should never again win a victory,and that I was to marry. And in return I made a solemn vow to marry no one whoknew the meaning of fear.

The Saga of the Volsungs, tr. Jesse L.Byock, Penguin Classics

She and Sigurd exchangevows. ‘Sigrdrifa’ appears in no other context, and Carolyne Larrington suggeststhe two valkyries are identical. The tale goes on to utter catastrophe. Unwittinglydrinking a potion that makes him forget Brynhild, Sigurd marries Gudrun andtricks Brynhild into marrying Gudrun’s brother Gunnar – impersonating him inthe test Brynhild sets her suitors, and leaping his horse through the ring offlames surrounding her hall. When she finds out, a bloodbath ensues anddoubtless Odin is satisfied.

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flames

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flamesBut what is a‘sleep-thorn’? Though ‘stabbed’ and ‘pricked’ by it, Sigrdrifa also refers to‘sleep-runes’.

Long I slept, long was I sleeping,

long are the woes of men;

Odin brought it about that I could not break

the sleep-runes.

The Poetic Edda, tr.Carolyne Larrington, OUP

I don’t know whetherit’s coincidental that ‘thorn’ is the name of the rune Þ (pronounced as a soft‘th’), or that Odin, in Hávamal,seizes the runes or runelore after hanging nine nights on a mystical tree.

I know that I hung on a windswept tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.

With no bread did they refresh me, nor a drink from a horn,

downward I peered;

I took up the runes, screaming I took them,

Then I fell back from there.

ThePoetic Edda, tr. Carolyne Larrington, OUP

Whatever the runicimplications, a ‘sleep-thorn’ clearly also had physical form and appears in twoof the legendary sagas dated at least to the 15th century. In Hrólfs Saga Kraka, Danish king Helgiarrogantly imposes himself upon the warrior-queen Olof, announcing hisintention to marry her at once. ‘That evening there was hard drinking’, andwhen the king collapses into bed with her, ‘The queen took advantage of thisand pierced him with a sleep-thorn; and the minute they [his retinue] were allgone, up she got, shaved off all his hair, and daubed him with tar.’ I’mcheering the queen on through this, and feel she was completely justified, butsad to say the saga takes a different view: later on Helgi gets his revenge,and the queen retaliates... In Gongu-Hrolf’sSaga, treacherous Vilhjálm pierces the sleeping Hrólf with a sleep-thorn,cuts off his legs and kidnaps his bride-to-be. But the sleep-thorn falls outwhen Hrólf’s faithful horse Dulcifal rolls him over, the dwarf Mondul healsHrólf’s legs, and the hero pursues his enemy, who confesses and is hanged.

Whatever a sleep-thornmeant to medieval Icelanders, the Sigrdrifa/Brynhild story is remarkably closeto that of the best-known sleeper of all time, The Sleeping Beauty: after having incurred the anger of a powerfulsupernatural figure, a young woman is pricked by something sharp and falls intoa lengthy enchanted sleep, protected or imprisoned by a barrier no one cancross except the hero appointed finally to wake her. Jacob Grimm in his Teutonic Mythology notes that the German version of the tale, Dorn-röschen, means literally ‘Thorn Rose’, and adds: ‘The thorn-rose has a meaning here, for we still call a moss-like excrescence on the wild rosebush schlaf-apfel [sleep-apple]; so that the very name of our sleeping beauty contains a reference to the myth. [...] When placed under the sleeper's pillow, he cannot wake till it be removed.’ Maybe this throws some light on the mystery?

The Sleeping Beauty pricksher finger on a spindle, and when I was a child I assumed spindles must besharp. They aren’t, but the princess’s century-long sleep is guarded by animpenetrable hedge of brambles or briars – which of course possess thorns.

Inearlier versions a splinter of flax causes the enchanted sleep. In the 14thcentury French prose romance Perceforest(set in a pagan, pre-Arthurian world) a feast is given for the goddesses Venus,Lucina and Thetis to celebrate the birth of the lady Zellandine. Offendedbecause she has not been presented with a knife to cut her food, Thetis ordainsthat ‘from the first thread of linen that Zellandine spins from her distaff’, apiece of flax will pierce the girl’s finger and she will fall into a long sleep.How is flax sharp? Well, making linen thread involved soaking and drying theflax stalks; the dried strands were then pulled through a toothed comb whichsnapped the stiff outer sheaths into small shards which might easily becomeembedded under a fingernail. This happens to Zellandine, and also to Talia, thesleeping heroine of Giambattista Basile’s ‘The Sun, the Moon and Talia’published in the Pentamerone (1636).Yet another instance of a flax-caused sleep comes in ‘The Ninth Captain’s Tale’which has been attributed to the OneThousand and One Nights but does not belong there. Heidi Anne Heiner of thewonderful website Sur La Lune researched it, and found it was a Egyptianfolktale collected by the translator J.C. Marcius from an Egyptian cook‘sometime prior’ to 1883. It tells of a girl whose mother begged Allah for achild, even if she were to be so delicate that the scent of flax would chokeher. The girl is born ‘fair as the rising moon’, eventually learns to spin (toshow off her lovely fingers): a piece of flax gets stuck under her fingernailand she falls swooning to the ground. (Midori Snyder’s excellent take on thestory can be read here.)

There is no way todemonstrate lines of descent, but the Sigurd/Brynhild story was much recycledin northern Europe, with additions and deletions according to taste. An exampleis a Faroese ballad, Brynhild’s Ballad,collected in 1851 but tentatively dated to the 14th century (read it at this link), and it cleaves closely to Volsunga Saga. Informed by ‘wild birds’ that ‘fair is Brynhild Buđledaughter,/Sheyearns for your encounter,’ Sigurd rides to find her:

No one but brave Sigurd

entered Hildar-hill,

he jumped through smoke and fiery-fire,

he and his horse Grani.

[...]

There he saw that pretty maid

sleeping in her mail,

raised his good and sharpened sword,

andcut the mail wide open.

Brynhild welcomesSigurd, but suggests he should first ask her father’s permission to sleep withher. Sigurd replies that he doesn’t want to meet her father, and why should hein any case, since, ‘You are not exactly known/to take your father’s advice.’The ballad ends with Sigurd and the ‘mighty maid’ making love and conceivingtheir daughter Ásla.

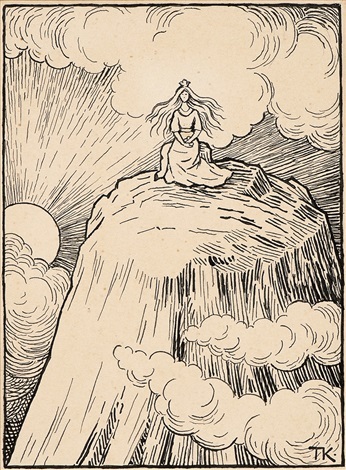

A later version is a 16th century Danish balladSivard og Brynild in which Sivardrescues Brynild from a glass mountain (reminiscent of the fairytale ‘The Princess on the Glass Mountain’ widespread across Norway, Sweden, Poland andnorthern Germany). The ballad was translated by George Borrow and it was printedin 1913 for private circulation as TheTale of Brynild, and King Valdemar and His Sister: Two Ballads (read it here). It begins:

Sivard he a colt has got,

The swiftest ’neath the sun;

Proud Brynild from the Hill of Glass

In open day he won.

Unto her did of knights and swains

The very flower ride;

Not one of them the maid to win

Could climb the mountain’s side.

From the fairytaleopening things go downhill fast: Sivard succeeds, but instead of marrying Brynild,‘To bold Sir Nielus her he gave/To show him his regard’. Discovering that Sivardhas given a gold betrothal ring to the maiden Signelil, the angry Brynild demandsthat Sir Nielus bring her Sivard’s head: naturally it all ends in another bloodbath.

The lapse of time is implicitin these tales but not made much of. Sigrdrifa says, ‘Long I slept, long was Isleeping’ but we’re not told for howlong. The ‘valkyrie’ narratives focus on the tangled relationships, treachery andbloody tragedies that develop after the enchanted sleep has ended. There is notthat sense of confusion, loneliness, loss, and the discovery of a changed worldexperienced by many of the sleepers in my first post. Neither do any of the variousSleeping Beauties experience such emotions. In both Perceforest and the Pentamerone,the unconscious princess is raped by the prince and nine months later givesbirth, still sleeping – Zellandine to a baby boy, Talia to twins. Sucking at theirmother’s finger or breast, the babies suck out the splinter of flax, thuswaking her.

These busy, crowdedstories pay little or no attention to the lapse of time. Perrault’s ‘La Belleau Bois Dormant’ (1697) sanitised and gentrified the tale to suit hissophisticated saloniste audience: hisprince kneels ‘with trembling admiration’ at the bedside of the princess anddares not even kiss her. And the princess feels no shock at missing a century:her entire household shares her sleep, from her ladies-in-waiting down to thekitchen boy, dogs, horses and even the flies on the wall: her society wakeswith her. She doesn’t even miss her parents (not included in the slumber spell andnow long dead), and Perrault’s single gesture towards the length of time she’s sleptis an arch reference to the out-moded fashion of her dress. In the 1729 Englishtranslation by Robert Samber:

She was intirely dress’d, and very magnificently, but theytook care not to tell her, that she was drest like my great-grandmother, andhad a point band peeping over a high collar; she looked not a bit the lessbeautiful and charming for all that.

TheClassic Fairy Tales, Iona & Peter Opie.

Perrault adapts Basile’scontinuation of the story as follows: princess and prince marry. They have two children named Morning and Day.The prince becomes king and goes away to war; his mother, an ogress, orders thetwo children and their mother to be killed, and cooked for her to eat. The‘clerk of the kitchen’ hides the victims, substituting a lamb, a kid and a hind:the ogress discovers the trick and orders the three to be flung into a tub fullof poisonous snakes. At this moment the king returns, and the ogress jumps intothe tub herself, saving him the trouble of executing her. When I was a child Irather enjoyed this gruesome ending; nowadays I’m amused by the complacentcivility of the tale’s last sentence – ‘[The King] could not but be sorry, forshe was his mother, but he soon comforted himself with his beautiful wife, andhis pretty children.’ God forbid that any character of Perrault’s should suffer violent emotion.

From Sigrdrifa in the Poetic Edda to Perrault’s SleepingBeauty in the Wood, these tales are far less interested in the enchanted sleepitself, or how that lost time might affect the sleeper, than they are in thevarious dramatic events that take place once she wakes into a world which toall intents and purposes is no different from the one she fell asleep in.

With one exception:‘Dorn-röschen’ the Grimms’ version of the SleepingBeauty in the Wood. It's usually translated into English as ‘Little Briar Rose’: Iona and Peter Opie have unflatteringly compared this very shorttale with that of Perrault's lengthy one, stating that it ‘possesses little of the qualityof the French tale’. Well, I beg to differ. Perrault’s good Fairy engages in arelentless bustle of activity: she touches her wand individually to everyinhabitant of the castle to send them to sleep, she conjures up the hedge ofbriars ‘in a quarter of an hour’ – and the reader has barely time to drawbreath before the hundred years are done: in the very next paragraph ‘At theexpiration of a hundred years, the son of a King’ arrives, spots the towersfrom a distance and comes to investigate.

In contrast, this is how the Grimms’tale introduces the century of sleep:

But round about the castle there began to grow a hedge ofthorns, which every year became higher, and at last grew up close around thecastle and all over it, so that there was nothing of it to be seen, not eventhe flag upon the roof. But the story of the beautiful sleeping ‘Briar-rose’,for so the princess was named, went about the country, so that from time totime Kings’ sons came and tried to get through the thorny hedge into the castle.

But theyfound it impossible, for the thorns held fast together, as if they had hands,and the youths were caught in them, could not get loose again, and died amiserable death.

Afterlong, long years a King’s son came again into that country, and heard an oldman talking about the thorn-hedge, and that a castle was said to stand behindit in which a wonderfully beautiful princess, names Briar-rose, had been asleepfor a hundred years, and that the king and queen and the whole court wereasleep likewise.

There is room tobreathe. I love the slow, natural pace by which the hedge of thorns grows upand around the castle until it’s completely hidden; I love the way the story,now almost a legend, spreads around the countryside so that ‘from time to time’young princes come to try their luck, only to perish and be in turn forgotten;how at last ‘after long, long years’ the century of sleep is over and the time comesfor the spell to be broken. To compare ‘Little Briar Rose’ with ‘La Belle auBois Dormant’ is pointless: all the two stories have in common is the barebones of the plot. The Grimms’ tale is not witty or fashionable, it does notstrive either to amuse or to horrify, it’s not interested in characterisation. Rather,it places the hundred years’ sleep at the heart and centre of the tale and inits deceptive simplicity it is a meditation upon time.

In my next post I’ll belooking at folktales of kings sleeping under hills, sleeping armies, and, becausethe experience of lost time is so similar to that of enchanted sleepers, atsome of the many tales in which a seemingly short visit to fairyland or theotherworld turns out to have lasted years or centuries.

Picture credits:

The Sleeping Beauty by Edward Burne Jones - Manchester Art Gallery

Brunnhilde Asleep by Margaret Fernie Eaton, 1902

Sigurd Kills Fafnir and Sigurd Roasts Fafnir's Heart - from the Sigurd Portal

Sigurd and Gunnar at the ring of flames by J.C. Dolman, 1909

The Hedge of Thorns by Errol le Cain, 'Thorn Rose' 1975

The Princess on the Glass Mountain by Theodor Kittelsen, 1857 - 1914

The Sleeping Beauty by Daniel Maclise - Hartlepool Museums & Heritage Service

The Prince and the Old Man by Errol le Cain, 'Thorn Rose', 1975