Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 45

April 22, 2011

Faerie-led

What makes a writer choose one subject over another, one genre over another? What draws one writer to contemporary fiction, another to historical fiction, fantasy, or thrillers? While I know and admire a number of authors who can handle a variety of forms (Gillian Philip and Nicola Morgan, for example, who seem equally and brilliantly at home with both gritty thrillers and historical or fantasy novels) – there are others like myself who stick to a single last. From the age of about ten, writing fantasy has been my first and only love.

This doesn't mean to say that I haven't had qualms. I've asked myself, in the past, what relevance fantasy has or can have to the problems of life. Can it really be serious? Shouldn't I – shouldn't I? – be writing something more meaningful?

But I have come to the conclusion that what is done with a whole heart, with love, and with as much artistic truth as I can personally muster, must be good enough. More than that is out of my control. I don't have a choice. There is in writing, as in all art – Susan Price has eloquently written about it for Katherine Robert's Muse Mondays, here – something that feels remarkably like outside inspiration: a fierce compulsion that grasps you by the hair and demands and absolutely requires: this is what you will write about: this and this alone. If you don't obey it you feel restless, haunted. You cannot ignore it. You cannot decide to write about something else. (Or if you try, what you turn out will be stale, flat and unprofitable.)

The problem is that the divine or daemonic impulse will only take you so far. It sets you going and then leaves you to stumble on alone as best you can. If you're lucky, you'll get occasional vivid flashes to light your path, but for the rest, you'll need patience, persistence, technique and plenty of common sense. This applies no matter what type of fiction you happen to have fallen in love with.

But it's good to be aware of the particular pitfalls of your chosen genre. I wouldn't like to speak for others, but in the early mid stages of my career as a fantasy writer I was anxious for a while about the possibility of getting carried away by colourful but superficial effects, and forgetting or neglecting emotional truth. What it boils down to is, that whatever their circumstances, the characters should have space to live and breathe. Ulysses isn't just a man island-hopping from one astounding adventure to another: he's a war-weary veteran desperate to get home. Malory's Lancelot isn't merely the best knight in the world and a hero sans reproche, he's a breathing, fallible man torn between his honour and his sense of sin: his love for Arthur and his love for Guinevere. He knows he's unworthy of the Holy Grail – so when he's finally allowed to perform a miracle of healing, he reacts with uncontrollable tears, weeping 'like a child that has been beaten'.

Here's a short ballad I wrote to warn myself about the dangers of following the queen of faerie rather too far into the dry lands.

As I walked out one summer day,

under the summer sky,

I saw about me the hills of summer

quaking with heat, and I

wondering saw a fair lady ride

down a slope in my mind:

it seemed she was the queen of fays

with the fairy host behind;

but they passed over the dry grass

through the quivering air

like vague thoughts passing

that are hardly there:

and where was the green velvet

and the rich jangling bells,

and the colour, and the dazzle

that the ballad tells

bewildered young Thomas the Rhymer

under the Eildon tree? –

thinking she was the queen of heaven

he bent his knee:

but it's no, no, she says, no,

I am not what you think.

I cannot give you water and wine,

only dust to drink:

and you shall gain nothing from me

of knowledge of men;

but you shall blow down the hillside

ghostly in the sun.

Picture credit: Thomas Rhymer by Joseph Noel Paton

Published on April 22, 2011 01:09

April 14, 2011

The White Horse of Uffington

A couple of nights ago, in the bright light of a half moon, we went up on to the Downs to visit the Uffington White Horse. This was an activity I discovered a few years ago, in winter – and believe me, visiting the Horse on a frosty winter night under a full moon is magic enough to make the back of your neck prickle.

For those of you who don't know it, or aren't lucky enough to live as I do, in the Vale which bears its name, the Uffington White Horse is a prehistoric chalk figure, cut into the turf to expose the white chalk beneath, close to the Iron Age hillfort known as Uffington Castle which rings the crest of the hill above it – but a bit older, late Bronze Age - around 3000 years old. Nobody knows anymore what it was for or what it signifies, but the impressive fact is that it has been maintained by local people - continuously - for the last three millennia, by a process of 'scouring' it every few years: this involves weeding it, and pounding lumps of broken chalk into the outline to rewhiten it. Otherwise, the turf would've reclaimed it within a few decades. In historical times, a huge country fair used to be associated with this. Nowadays, the National Trust turns up every so often with piles of chalk and baskets of hammers, and asks for volunteers. I've had a go myself – there's a bit of the upper foreleg which is forever mine – and the thumping of about fifteen or twenty hammers pulverising the chalk up and down the length of the figure as it curls over the shoulder of the hill (it's far too big to see all of it at once when you're up close) sounds weirdly like galloping hooves…

Some people say the Horse isn't a horse, but a dragon. It certainly isn't a realistic representation of a horse, but it's very much like horses on early Celtic coins: the Celts went in for abstract, flowing lines, and I'd agree with Granny Aching from Terry Pratchett's wonderful Discworld book 'A Hat Full of Sky': "Taint what a horse looks like, it's what a horse be."

Anyway, by moonlight, the Horse glows. We walked over the top of the Iron Age fort (past the much more recent barrow where Roman soldiers were buried) and down the slope in the watercolour moonlight, in the teeth of a sweeping cold wind, and down towards the head of the Horse. It lay there on the dim hill, its great eye and strange, open parallelogram of a head glowing mysteriously, almost appearing to throw more light back to the moon than the moon could give. Its body swept in a serpentine line over the slope of the hill, away out of sight.

I would say I feel sure it was meant to be looked at by moonlight, except that I'm not sure. It's hard to be sure of anything at all about the Horse. But I am sure that, intentional or not, once anyone's seen it by moonlight, now or three thousand years ago, they'd agree that this is when the Horse comes into its power. I half expected it to lift its head, come alive and levitate off the hill.

You would think there would be scores of poems written about the White Horse of Uffington, but the only one I can find is GK Chesterton's immensely long 'Ballad of the White Horse' (written when the Horse was still thought to be as recent as King Alfred's victory over the Danes, and much more about Alfred than the Horse). I think these lines from the poem do still suggest something of the Horse's wonder and power.

Before the gods that made the gods

Had seen their sunrise pass,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was cut out of the grass.

Before the gods that made the gods

Had drunk at dawn their fill,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was hoary on the hill.

Age beyond age on British land,

Aeons on aeons gone,

Was peace and war in western hills,

And the White Horse looked on.

For the White Horse knew England

When there was none to know;

He saw the first oar break or bend,

He saw heaven fall and the world end,

O God, how long ago.

For the end of the world was long ago,

And all we dwell to-day

As children of some second birth,

Like a strange people left on earth

After a judgment day.

So... does anyone know any other poems about the White Horse? Or have any of you written one?

Photo credits: 'The Uffington White Horse' by Microlightpilot.com; the White Horse's eye by Berkshire History.com

For those of you who don't know it, or aren't lucky enough to live as I do, in the Vale which bears its name, the Uffington White Horse is a prehistoric chalk figure, cut into the turf to expose the white chalk beneath, close to the Iron Age hillfort known as Uffington Castle which rings the crest of the hill above it – but a bit older, late Bronze Age - around 3000 years old. Nobody knows anymore what it was for or what it signifies, but the impressive fact is that it has been maintained by local people - continuously - for the last three millennia, by a process of 'scouring' it every few years: this involves weeding it, and pounding lumps of broken chalk into the outline to rewhiten it. Otherwise, the turf would've reclaimed it within a few decades. In historical times, a huge country fair used to be associated with this. Nowadays, the National Trust turns up every so often with piles of chalk and baskets of hammers, and asks for volunteers. I've had a go myself – there's a bit of the upper foreleg which is forever mine – and the thumping of about fifteen or twenty hammers pulverising the chalk up and down the length of the figure as it curls over the shoulder of the hill (it's far too big to see all of it at once when you're up close) sounds weirdly like galloping hooves…

Some people say the Horse isn't a horse, but a dragon. It certainly isn't a realistic representation of a horse, but it's very much like horses on early Celtic coins: the Celts went in for abstract, flowing lines, and I'd agree with Granny Aching from Terry Pratchett's wonderful Discworld book 'A Hat Full of Sky': "Taint what a horse looks like, it's what a horse be."

Anyway, by moonlight, the Horse glows. We walked over the top of the Iron Age fort (past the much more recent barrow where Roman soldiers were buried) and down the slope in the watercolour moonlight, in the teeth of a sweeping cold wind, and down towards the head of the Horse. It lay there on the dim hill, its great eye and strange, open parallelogram of a head glowing mysteriously, almost appearing to throw more light back to the moon than the moon could give. Its body swept in a serpentine line over the slope of the hill, away out of sight.

I would say I feel sure it was meant to be looked at by moonlight, except that I'm not sure. It's hard to be sure of anything at all about the Horse. But I am sure that, intentional or not, once anyone's seen it by moonlight, now or three thousand years ago, they'd agree that this is when the Horse comes into its power. I half expected it to lift its head, come alive and levitate off the hill.

You would think there would be scores of poems written about the White Horse of Uffington, but the only one I can find is GK Chesterton's immensely long 'Ballad of the White Horse' (written when the Horse was still thought to be as recent as King Alfred's victory over the Danes, and much more about Alfred than the Horse). I think these lines from the poem do still suggest something of the Horse's wonder and power.

Before the gods that made the gods

Had seen their sunrise pass,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was cut out of the grass.

Before the gods that made the gods

Had drunk at dawn their fill,

The White Horse of the White Horse Vale

Was hoary on the hill.

Age beyond age on British land,

Aeons on aeons gone,

Was peace and war in western hills,

And the White Horse looked on.

For the White Horse knew England

When there was none to know;

He saw the first oar break or bend,

He saw heaven fall and the world end,

O God, how long ago.

For the end of the world was long ago,

And all we dwell to-day

As children of some second birth,

Like a strange people left on earth

After a judgment day.

So... does anyone know any other poems about the White Horse? Or have any of you written one?

Photo credits: 'The Uffington White Horse' by Microlightpilot.com; the White Horse's eye by Berkshire History.com

Published on April 14, 2011 15:22

April 8, 2011

Robin Hood, and meeting people in wild places

It's a lovely spring morning, and I'm heading off to London, but time for a quick blog post before I leave... and to fill you in a little on what to expect here at Steel Thistles for the next few weeks.

It's a lovely spring morning, and I'm heading off to London, but time for a quick blog post before I leave... and to fill you in a little on what to expect here at Steel Thistles for the next few weeks.I'm hoping to begin a new series of Fairytale Reflections, some time in May. Between then and now, I'll be popping in and out with posts about this, that and the other.

So, for the next few Fridays, I'm going to be talking about fairytale poems - some of my own, and some old favourites. I'll end this post with one, but first I just have to tell you something which has been amusing me this morning as I sat out in our garden with my first cup of coffee and - as always - a book to read. The book in question is 'The Chronicles of Robin Hood' by Rosemary Sutcliff. I've always loved her work; and since 'The Eagle' came out recently (I haven't seen it yet, but I hear good things) I've been enjoying going back to some of her earliest books. This was published in 1950. I owned it as a child, and always cried at the end, where dying Robin Hood shoots the arrow into the greenwood and asks Little John to bury him where it falls. (The only other book that could make me cry was Black Beauty. Children have hard little hearts. I cry all the time at everything, these days.)

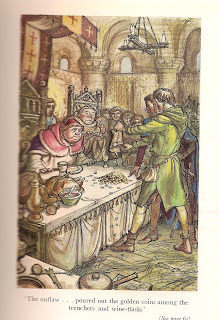

Anyway, I do love Sutcliff, and this story, old fashioned as it is, is still wonderfully enjoyable, but reading it as an adult, I couldn't help but lift an eyebrow at the way in which EVERYTHING Robin does is presented as perfectly, four-square righteous... even when he's clearly in the wrong. Just look at this. Robin ands his men have stopped a cavacade of monks wending their way through the woods with a posse of men-at-arms and packhorses.

Little John addressed himself to the foremost monk. 'Shame on you, Sir Monk, to keep pour master waiting!'

The monk is, rashly, rather rude:

The monk reined in and sat looking down at him angrily. 'And who is your master, you great oaf?'

'Robin Hood, the lord of these parts. He bids you dine with him - and he is not used to being kept waiting!'

The monk is even ruder:

'Robin Hood, is he?' said the monk with an ugly laugh. 'A foul thief if ever there was one, and he will be sure to hang on the gallows tree at the last!' And setting spurs to his horse, he strove to ride down the three outlaws.

Next moment Much's bowstring twanged and a long arrow hummed its way into the monk's heart.

Call me a wuss if you like, but shooting the poor man dead does seem a bit extreme to me... Anyway, the men-at-arms flee, and the outlaws lead the surviving monk back to the glade, where:

Robin greeted his unwilling guest with all courtesy. 'Welcome to the Greenwood, reverend Sir! It is a happy chance that has sent you to us on this feast of St John, for you shall say the mass for us...'

As a child I read all this totally on Robin's side. Robin Hood was Good. That was that. Anything he did was fine. Now, of course, I wonder how much Robin's courtesy sounded like sarcasm to the poor monk, and whether he agreed that it was a 'happy chance' to have his friend shot dead? No wonder that -

The monk was livid with spiteful fury, but he dared not disobey, and gabbled his way through the prayers while the outlaws knlet around him reverently...

Hmmm.....

I wonder if I'll still cry at the end?

Anyway, here's a fairy poem, as promised. Perhaps I should say verses rather than poetry, as this is one of mine, from a long time back. (All my poetry is from a long time back.) And it's about another encounter with a dark man on a road through the woods or the wilds: on one of the Old Straight Tracks that Alan Garner wrote about, which Alfred Watkins saw in a vision linking the sacred places of Old England, and he called them 'leys'.

Naming the King of the Fairies: or, How to get out of the Hill

His fair face is so still and calm

You never would think he means you harm

If he sets his hand on the bridle-rein

Your horse will start away, away –

See! Full of crows the turning sky

As on the straight ley road you lie.

Under the hill the air is dark,

The smells are all of mould and clay,

He'll show you where the dead men are,

And like a child, lead you away.

Young Roland blew his ox's horn

To make the dark tower tumble down –

But here he stays with Helen and John:

They toss a gilded ball and play.

You and the dark young man look on

But never a word they say.

He leads you on, he leads you down

Until you come to great Troy Town.

The walls are low, not two feet high –

Along you dance, for you must try

To find the fountain in the dark

That wells up from the centre mark.

The mazing streets are not too wide

(sing sweetly in the dry, black air)

They press you in on either side –

You're at the fountain, in the square.

The darkness snuffles like a mole.

You'll never leave or find your home

If once you drink from that stone bowl,

But leaning on the fountain there

The dark young man will have you whole –

You'll stay until your bones are bare.

He takes your wrist and on you go

To earthworm tunnels far below,

You taste the clay, you taste the marl,

Those fairy ferns are pressed in coal.

Now you're in trouble, cold as fate

Shouldering the hill's demanding weight.

Don't lose your nerve or feel despair

If you want to be free in the windy air.

He'll loose your hand and go away;

He'll leave you cramped and buried here:

You'll choke your life out far from day

If once you falter, weak from fear.

It's breathless-black, you're wrapped in earth

Your mouth is clogged, you dream of death…

Pull from his grip and think of birth!

Say, 'King Arawn, I will not stay!'

He'll lift you to his roof of turf

And out you'll stand on the ley.

Published on April 08, 2011 02:11

April 4, 2011

The Boy in the Golden Cape

I've been reading a remarkable book by Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul T Barber, 'When they Severed Earth from Sky: How the Human Mind Shapes Myth', Princeton UP, 2005. It's about the persistence of real physical information in ancient myths, and begins with a Klamath mythical story from Oregon, all about the creation of Crater Lake. The story, recorded in 1865 – even when you make allowances for European translation, rewording, and bias – describes a battle between 'the Chief of the Below World' and 'the Chief of the Above World' involving fire, burning ashes and the disappearance of an entire mountain, in such a way as certainly to encode an eyewitness account of the eruption of the volcano geologists deduce once stood 14,000 feet high between Mount St Helens and Mount Shasta. The catastrophic explosion of its magma chamber pulverised the entire mountain and formed the giant crater which now forms Crater Lake. And here's the thing: the eruption has been ice-dated (from ash layers) to nearly 7,700 years ago. So the Klamath explanation of this event has been handed down for millennia.

According to the Barbers, this isn't even unusual. Hawaiian mythical accounts of battles between various of their chiefs and the volcano goddess Pele can be closely correlated to radiocarbon dates for different lava flows. And I was absolutely fascinated by their chapter on the (massive) eruption of Thera in the Mediterranean, in around 1625 BC: check out this passage from Hesiod's poem 'The Birth of the Gods', about the battle between the gods and the Titans:

…wide heaven groaned, shaking, and great Olympus shook… and heavy quaking reached gloomy Tartarus… And the cry of both sides reached the starry sky as they bellowed and came together with a great battle shout. Nor did Zeus hold back his might, but now indeed…from Olympus he came, hurling lightning continually, and the bolts flew thickly amid thunder and flashing from his powerful hand…and all around the great boundless woods crackled with fire. …The hot blast surrounded the earthborn Titans, and a boundless flame reached to the bright upper air… and it seemed, facing it, as if Earth and wide Heaven above collided, for so huge a boom would roll forth, as if Earth were being hurled up while Sky were falling down from above…

Hesiod was writing about 700 BC, so nine hundred years after the eruption – but most poetry had been oral up to his time, and it's highly likely his account dates back much, much further.

And wouldn't it be odd if such a cataclysmic eruption hadn't been talked and wondered and sung about by the peoples ringing the Middle Sea, for centuries and centuries? The Barbers point also to the Exodus account in the Bible, in which Moses leads his people out of Egypt, guided by a pillar of smoke by day and a pillar of fire by night: 'for people moving north down the Nile valley to where the Delta opens out, an eruption pillar from Thera would indeed be ahead of them.' Though they go on to caution: 'whether the Exodus… actually occurred in 1625 BC is another matter. Time often gets foreshortened in the telling of myths… thus Exodus as we have it may contain details from several different time periods.'

In recent years, we in the mythic and fairytale community have grown accustomed to the psychological exploration of myths, the discovery of their emotional relevance, so it's refreshing to be reminded that some myths may have sprung from simple matters of fact. This is not to explain them away, either, since mythologizing is all part of the long struggle of humanity to make sense of the world. A calamity like the Japanese tsunami requires an explanation, which nowadays is promptly delivered by science, via experts appearing on our television screens, details about plate tectonics and so on. Interesting and accurate as this is, I don't know how much comfort it provides. But without scientific knowledge of the immediate physical causes, the best way to make sense of the thing – to bring it to some kind of proportion – is to inject it with emotion, and by analogy with human passions, suppose it to be caused by the anger of gods of God. And this is consolatory, because understandable. Even when the causes of natural disasters are known and understood by most people, we still struggle to 'make sense' of the unbearable loss of innocent lives. 'Human kind/Cannot bear very much reality'.

Well, do read the book, which is wise and fascinating and wonderful. And here's an epilogue, not in the book at all. In the British Museum is an utterly gorgeous golden cape. It dates to somewhere between 1900 – 1600 BC, and was found by workmen in Mold, Wales, in 1833. (They threw away the bones it clothed, tore it to pieces and shared it out, and it had to be painstakingly reconstructed, but that's another story.) I've seen it myself and the gold is as bright and yellow as summer buttercups.

It was one of the 100 objects in BBC Radio 4's 'History of the World In 100 Objects', so you may have heard about it there. The gold is so fragile that it could only have been used ceremoniously: and it's too small for a man, so must have belonged either to a woman, or a youth. Maybe a teenage king or priest was buried in it.

But the mound those workmen were digging into was in a field called Bryn-yr-Ellyllon, which means 'the Hill of the Fairies': and the legend of the hill was that it was haunted by a ghostly boy, all clad in gold. Just think of that for a moment... Isn't it possible, then, that the sight of a young man being laid to rest in his shimmering golden cape so impressed and touched the onlookers, that for nearly four thousand years if a child said, 'Mother, who's buried in that hill?' the answer was: 'A boy all dressed in gold'?

Photo credits: Crater Lake Oregon courtesy of Planet Oddity

According to the Barbers, this isn't even unusual. Hawaiian mythical accounts of battles between various of their chiefs and the volcano goddess Pele can be closely correlated to radiocarbon dates for different lava flows. And I was absolutely fascinated by their chapter on the (massive) eruption of Thera in the Mediterranean, in around 1625 BC: check out this passage from Hesiod's poem 'The Birth of the Gods', about the battle between the gods and the Titans:

…wide heaven groaned, shaking, and great Olympus shook… and heavy quaking reached gloomy Tartarus… And the cry of both sides reached the starry sky as they bellowed and came together with a great battle shout. Nor did Zeus hold back his might, but now indeed…from Olympus he came, hurling lightning continually, and the bolts flew thickly amid thunder and flashing from his powerful hand…and all around the great boundless woods crackled with fire. …The hot blast surrounded the earthborn Titans, and a boundless flame reached to the bright upper air… and it seemed, facing it, as if Earth and wide Heaven above collided, for so huge a boom would roll forth, as if Earth were being hurled up while Sky were falling down from above…

Hesiod was writing about 700 BC, so nine hundred years after the eruption – but most poetry had been oral up to his time, and it's highly likely his account dates back much, much further.

And wouldn't it be odd if such a cataclysmic eruption hadn't been talked and wondered and sung about by the peoples ringing the Middle Sea, for centuries and centuries? The Barbers point also to the Exodus account in the Bible, in which Moses leads his people out of Egypt, guided by a pillar of smoke by day and a pillar of fire by night: 'for people moving north down the Nile valley to where the Delta opens out, an eruption pillar from Thera would indeed be ahead of them.' Though they go on to caution: 'whether the Exodus… actually occurred in 1625 BC is another matter. Time often gets foreshortened in the telling of myths… thus Exodus as we have it may contain details from several different time periods.'

In recent years, we in the mythic and fairytale community have grown accustomed to the psychological exploration of myths, the discovery of their emotional relevance, so it's refreshing to be reminded that some myths may have sprung from simple matters of fact. This is not to explain them away, either, since mythologizing is all part of the long struggle of humanity to make sense of the world. A calamity like the Japanese tsunami requires an explanation, which nowadays is promptly delivered by science, via experts appearing on our television screens, details about plate tectonics and so on. Interesting and accurate as this is, I don't know how much comfort it provides. But without scientific knowledge of the immediate physical causes, the best way to make sense of the thing – to bring it to some kind of proportion – is to inject it with emotion, and by analogy with human passions, suppose it to be caused by the anger of gods of God. And this is consolatory, because understandable. Even when the causes of natural disasters are known and understood by most people, we still struggle to 'make sense' of the unbearable loss of innocent lives. 'Human kind/Cannot bear very much reality'.

Well, do read the book, which is wise and fascinating and wonderful. And here's an epilogue, not in the book at all. In the British Museum is an utterly gorgeous golden cape. It dates to somewhere between 1900 – 1600 BC, and was found by workmen in Mold, Wales, in 1833. (They threw away the bones it clothed, tore it to pieces and shared it out, and it had to be painstakingly reconstructed, but that's another story.) I've seen it myself and the gold is as bright and yellow as summer buttercups.

It was one of the 100 objects in BBC Radio 4's 'History of the World In 100 Objects', so you may have heard about it there. The gold is so fragile that it could only have been used ceremoniously: and it's too small for a man, so must have belonged either to a woman, or a youth. Maybe a teenage king or priest was buried in it.

But the mound those workmen were digging into was in a field called Bryn-yr-Ellyllon, which means 'the Hill of the Fairies': and the legend of the hill was that it was haunted by a ghostly boy, all clad in gold. Just think of that for a moment... Isn't it possible, then, that the sight of a young man being laid to rest in his shimmering golden cape so impressed and touched the onlookers, that for nearly four thousand years if a child said, 'Mother, who's buried in that hill?' the answer was: 'A boy all dressed in gold'?

Photo credits: Crater Lake Oregon courtesy of Planet Oddity

Published on April 04, 2011 02:21

March 30, 2011

"Well, I'm Back."

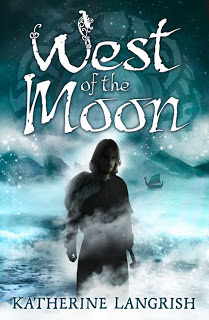

Today I end my journey - today is the last stop on the long road 'West of the Moon'. And I'd like to thank all of you who've come along with me, even for part of it, for your tremendous patience with this slightly odd business of an author hyping her own book. I mean, gosh, it's not really the way my mother brought me up. I, like you, was taught not to blow my own trumpet. You were supposed to receive a compliment with a deprecating smile and some such remark as, 'Oh it's nothing, really'. The phrase 'He's not backwards at coming forwards!' was not used with approval.

Today I end my journey - today is the last stop on the long road 'West of the Moon'. And I'd like to thank all of you who've come along with me, even for part of it, for your tremendous patience with this slightly odd business of an author hyping her own book. I mean, gosh, it's not really the way my mother brought me up. I, like you, was taught not to blow my own trumpet. You were supposed to receive a compliment with a deprecating smile and some such remark as, 'Oh it's nothing, really'. The phrase 'He's not backwards at coming forwards!' was not used with approval. But times have changed, and I'm not sure now how useful some of that advice really was. There are a lot of books in the world, and to assume (or hope) that one's own will attract attention while one stands modestly in the wings waiting for the applause, may actually be more arrogant than to go out there and tell people about it. If it was worth writing, perhaps it's worth talking about.

I hope I haven't bored you. I hope I've managed (I certainly tried) to find different approaches, different ways of saying - effectively - I spent getting on for ten years writing this book, I loved doing it, I love the characters, and I love the folklore and mythology which overshadow and permeate it. I want to share my enthusiasm and joy not just in the book I created but in the wider and greater context of all the stories I discovered along the way - folktales from Iceland and Norway and the Orkneys, the Icelandic sagas, the Eddas, and the stories and legends of the Mi'kmaq of Canada.

Anyway, today I am delighted to have been asked to talk about anti-tales (and anti-heroes) at The Paradoxes of Mr Pond . Here you will find me talking about characters such as Bluebeard, Lady Mary, Mr Fox and my own Harald Silkenhair. And to celebrate the end of the tour, there's also a rather unusual competition at The Hog's Head to win a signed copy of 'West of the Moon'.

It'll be back to normal on Seven Miles of Steel Thistles after this. But I've enjoyed every step of my journey and met some wonderful people along the way. Especial thanks to all the fantastic bloggers who hosted me. And now at last I can say (drawing a deep breath):

"Well, I'm back."

Published on March 30, 2011 02:29

March 28, 2011

Diana Wynne Jones - In Memoriam

I never met her. But many of you will know exactly what I mean when I say that in a way, I feel as if I had known her for years. That mysterious connection between reader and author, between the storyteller and those who love to listen, worked its inextricable magic and linked us forever. And this feeling is particularly strong when the author concerned is one whose work we first met and loved as children. I was in my early teens when 'Wilkins Tooth' came out in 1973, and I've never stopped reading her books from that day to this.

I never met her. But many of you will know exactly what I mean when I say that in a way, I feel as if I had known her for years. That mysterious connection between reader and author, between the storyteller and those who love to listen, worked its inextricable magic and linked us forever. And this feeling is particularly strong when the author concerned is one whose work we first met and loved as children. I was in my early teens when 'Wilkins Tooth' came out in 1973, and I've never stopped reading her books from that day to this. And such wonderful books! Diana Wynne Jones is – for as Jane Yolen has said, her writing will continue to shine for us – a writer whose warmth of personality fills her work. Her range was extraordinary. Sane, witty, exuberant, compassionate, yet also eldritch, eerie, poetic, tragic. There's the wild fantasy of the Dalemark Quartet, a world in which the gods come and go in a way that raises the hair on the back of your neck, yet – typically for Diana, a grounded writer if ever there was one – a world full of complex politics, flawed heroes and difficult moral choices. She understood anger. She understood grief. She knew that bad things happen to good people, and good people can do bad things.

Many of her heroes are underdogs, people who feel insignificant and disadvantaged - until under pressure they discover hidden talents, hidden strength. On the other hand, she also wrote about the responsibilities of power. In 'The Lives of Christopher Chant', she shows us why young Christopher uses his power to help his uncle exploit other people in other worlds – unloved and naïve, he falls for his uncle's flattery – but his innocence is not really an excuse. We see that Christopher hasn't used his intelligence. When he finally does put two and two together, it is too late for the mermaids. Christopher feels guilty and he deserves to. As Chrestomanci, it will be his duty to police the world of magic, to ensure that power is harnessed, not abused.

I don't know which of her books is my favourite. There seems to be one for every mood. It could be 'The Time of the Ghost' – a tour de force of such intricate construction that even though I've read it countless times I still sometimes can't remember the identity of the narrator, the poor speechless ghost who goes whirling through the tragi-comic chaos of her past life. Or it could be 'The Homeward Bounders', that wonderful take on the legends of Prometheus, the Flying Dutchman, the Wandering Jew – and on war-gaming – in which displaced Jamie wanders forever between the worlds, trying to get back Home. Or it could be 'Dogsbody', or 'Eight Days of Luke', or 'Drowned Ammet', or 'Fire and Hemlock.'

And she was so funny. Think of the hilarious Sci-fi and Fantasy convention in 'Deep Secret' (clearly drawn from life!) and the indispensable 'Tough Guide to Fantasyland' which will unerringly lead the would-be author – safe, but goggling – past every one of the innumerable potholes and mantraps on the road to writing a fantasy.

I fancy that Fantasyland has fallen very quiet today. And that every pennon of every castle, from the Tower of Sorcery to the Dark Citadel, has been lowered to honour the passing of the queen of fantasy. Diana Wynne Jones, a great lady and a great writer.

Published on March 28, 2011 09:07

March 23, 2011

West of the Moon tour (17)

Things have got a bit ahead of me over the last few days - I was busy most of yesterday with the Daily Telegraph letter, and although I don't know if they will use it, heartfelt thanks to everyone who signed it and/or sent emails of support. As Pamela, in the 27th comment to my last post, points out, it's just daft to make speeches about promoting literacy while at the same time cutting libraries and library staff.

But now I'll get off my soapbox (which I rarely climb) and get back to the West of the Moon tour - which will end at the end of the month, you may like to know (it's really not going to go on for ever!) To return to the metaphor of the journey which which I set out, I'm over the Misty Mountains and have reached a safe haven at Serendipity - where I'll be until Saturday, answering questions and writing about this and that and generally lounging about having a good time. Today is an interview about my 'Big Break' - the wonderful day when I finally got a publisher.

And if you missed the last couple of stops and would like to visit, recently I've been at Girls Without A Bookshelf (how do they manage?) issuing my Ten Commandments of Creative Writing, at The Book Mogul trying desperately to choose my Five Favourite Books of All Time - and at Bloggers[heart]Books - where they asked me some really lovely questions - including which fantasy world I would like to visit, and my definition of love. (Wow.)

Thankyou all for staying with me - the end is in sight!

But now I'll get off my soapbox (which I rarely climb) and get back to the West of the Moon tour - which will end at the end of the month, you may like to know (it's really not going to go on for ever!) To return to the metaphor of the journey which which I set out, I'm over the Misty Mountains and have reached a safe haven at Serendipity - where I'll be until Saturday, answering questions and writing about this and that and generally lounging about having a good time. Today is an interview about my 'Big Break' - the wonderful day when I finally got a publisher.

And if you missed the last couple of stops and would like to visit, recently I've been at Girls Without A Bookshelf (how do they manage?) issuing my Ten Commandments of Creative Writing, at The Book Mogul trying desperately to choose my Five Favourite Books of All Time - and at Bloggers[heart]Books - where they asked me some really lovely questions - including which fantasy world I would like to visit, and my definition of love. (Wow.)

Thankyou all for staying with me - the end is in sight!

Published on March 23, 2011 01:50

March 22, 2011

'Leading Authors' to propose list of 50 books children should read.

Having read this article in the Daily Telegraph, which reports Michael Gove as about to begin an initiative to get children reading 50 books a year, with the help of a list of suggested titles to be compiled by 'leading authors', we, the undersigned, have written to the Telegraph as follows:

Dear Sir,

Everybody must approve of children reading more, so Michael Gove's wish to raise the number of books we expect our children to read is no bad one in principle. However, the idea of a list of 50 titles 'that every child should read' sounds prescriptive and inflexible - likely to concentrate on classics or high-profile books which teaching professionals will already know.

There are plenty of guides to good reading for children: for example the School Library Associations's 'Riveting Reads', or 'The Ultimate Book Guide', published by AC Black, which lists more than 700 titles, chosen by a broad field of over 170 children's authors, with short descriptions and links leading from one book to another on the 'what to read next' principle.

But in any case there are skilled, professional people who know more about this than we do: librarians. What is needed is a flexible approach which can offer children the books most suitable to their ability and preferences. Librarians can do this. It's no good suggesting to a child that she 'should' read 'The Wind in the Willows', if she doesn't actually like it. Instead of a golden standard, the list of fifty books could become just another bugbear.

It seems perverse to begin this initiative against a background of the proposed closure of a high percentage of English public libraries and the sacking of many school librarians. Fifty books a year would cost well over £300 per child: much better to share them! Perhaps Mr Gove should consider protecting school library provision by law.

Sincerely,

Katherine Langrish

Keren David

Ellen Renner

Charles Butler

Nick Green

Jackie Morris

Marie-Louise Jensen

Tamsyn Murray

Adele Geras

Debi Gliori

Maria Nikolajeva

Susie Day

Bryony Pearce

Frances Thomas

Annie Dalton

Fiona Dunbar

Liz Kessler

Gillian Philip

Mary Hoffman

Celia Rees

John Dougherty

Michelle Lovric

Dennis Hamley

Malorie Blackman

Joanna Kenrick

Catherine Johnson

Savita Kalhan

Dee Shulman

Jo Nadin

Philippa Francis

Malcolm Rose

Julie Sykes

Elizabeth Baguley

Dear Sir,

Everybody must approve of children reading more, so Michael Gove's wish to raise the number of books we expect our children to read is no bad one in principle. However, the idea of a list of 50 titles 'that every child should read' sounds prescriptive and inflexible - likely to concentrate on classics or high-profile books which teaching professionals will already know.

There are plenty of guides to good reading for children: for example the School Library Associations's 'Riveting Reads', or 'The Ultimate Book Guide', published by AC Black, which lists more than 700 titles, chosen by a broad field of over 170 children's authors, with short descriptions and links leading from one book to another on the 'what to read next' principle.

But in any case there are skilled, professional people who know more about this than we do: librarians. What is needed is a flexible approach which can offer children the books most suitable to their ability and preferences. Librarians can do this. It's no good suggesting to a child that she 'should' read 'The Wind in the Willows', if she doesn't actually like it. Instead of a golden standard, the list of fifty books could become just another bugbear.

It seems perverse to begin this initiative against a background of the proposed closure of a high percentage of English public libraries and the sacking of many school librarians. Fifty books a year would cost well over £300 per child: much better to share them! Perhaps Mr Gove should consider protecting school library provision by law.

Sincerely,

Katherine Langrish

Keren David

Ellen Renner

Charles Butler

Nick Green

Jackie Morris

Marie-Louise Jensen

Tamsyn Murray

Adele Geras

Debi Gliori

Maria Nikolajeva

Susie Day

Bryony Pearce

Frances Thomas

Annie Dalton

Fiona Dunbar

Liz Kessler

Gillian Philip

Mary Hoffman

Celia Rees

John Dougherty

Michelle Lovric

Dennis Hamley

Malorie Blackman

Joanna Kenrick

Catherine Johnson

Savita Kalhan

Dee Shulman

Jo Nadin

Philippa Francis

Malcolm Rose

Julie Sykes

Elizabeth Baguley

Published on March 22, 2011 04:00

March 21, 2011

West of the Moon tour (16)

Over at the Book Mogul today. She asked me to list my five favourite children's books of all time. Yikes! For this way-too-difficult task, I got my daughter to help.

Published on March 21, 2011 12:48

March 19, 2011

Finding Your Voice

This morning I am over at my other home, The Awfully Big Blog Adventure, collective blog of the (British) Scattered Authors Society, where I am thoroughly enjoying myself. You see, yesterday I hauled out all my old manuscripts going back to when I was ten, and took a look at them. In between cringing, laughing, and occasionally exclaiming 'Wow - not bad...!' I had a heck of a lot of fun, and thought I would share with you some of the steps along the way to what is called 'finding your own voice'. I don't know if there are any short cuts. There weren't for me - but I loved every minute of it.

Published on March 19, 2011 02:28