Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 38

March 21, 2012

"Damaged people do damage" : an interview with Celia Rees

So here's Celia Rees herself to talk about her latest YA thriller 'This Is Not Forgiveness'. Having heard her read aloud from the first page or two of this book while it was still a work in progress, I knew it was going to be a real page-turner, and so it has proved - but as always from Celia's hands, a thriller that gives us much to think about. On to the questions! "This Is Not Forgiveness" is a firecracker of a thriller, but it's also a love story - a vicious triangle of a love-story. And I can't help noticing that the story you chose to talk about for 'Fairytale Reflections', the Welsh legend of Blodeuedd, the maiden made of flowers, is also the story of the disastrous love of two men for one woman. Is there any connection?

The starting point for the novel was François Truffaut's, Jules et Jim. In the film two young men, who are close friends, fall in love with the same woman, played by Jeanne Moreau. She is a wild, free spirit and completely unconventional. Both of them try to shape and control her, but she keeps breaking any hold either of them have on her. This folie a trois has unavoidable and tragic consequences. The story is set before and after the First World War but I started thinking, 'You could update this. Make it now.' Whenever I have an idea like that, I begin to collect things – songs, poems, pictures, other writing and references. I came to Blodeuedd and the Mabinogion through The Owl Service, Alan Garner's re-working of the legend. As soon as I made the connection, it seemed some kind of validation. Blodeuedd is one of my favourite stories from the Mabinogion. There are two sets of men involved with one woman. Math and Gwydion who create her from flowers and Lleu and Gronw who are rivals for her love. My story is not a straight re-telling at all, but the myth has resonance within my story and this means that the roots are deep. That there is something archetypal, universal about it.

Two of the three main characters are predators. At the very beginning of the book, the heroine Caro sits in a bar despising everyone and 'picking out victims', an occupation ultimately echoed by Rob, a soldier and sniper invalided out of Afghanistan. Only Jamie, Rob's younger brother, seems innocent. Yet you don't demonise any of them. How deliberate was that?

I always saw Jamie as being a bit of an innocent, bearing witness. He has been described as naïve, as if to be so is a bad thing, but he is naïve in the way of most teenagers in that he has yet to venture out of the tight circle of his own concerns. Caro sees him as the Tarot Fool. The Fool is an innocent in search of experience. He is full of wonder, visions, questions and excitement but he doesn't know where he is going and is often depicted as standing on the edge of a precipice. Caro can see this, but she is blind to her own self delusion or to exactly what is going on with Rob.

I did not want to demonise either her or Rob.

I don't want the reader to be able to judge them or dismiss their actions. That would be too easy. There are reasons for the way they behave. Damaged people do damage. I like making the reader re-evaluate their judgements about character, re-assess.

Caro is fascinated by glamorous, articulate female terrorists like Ulrike Meinhof. She continually pushes the limits, sees how far she can go. Would you say that she and Rob are attracted to violence because it makes them feel alive?

My first motive for giving Caro an interest in radical politics was to make her different from other girls. When I first pitched the idea, it was met with some scepticism, in a 'radical politics, isn't that a bit '60s?' kind of way. Then came the Stop the Cuts Demos in London and the associated street violence and suddenly it was OK. It struck me that Caro would be a girl who would want to take it a little bit further. She is also clever and would do her research. She would arrive at the Red Army Faktion and Baader-Meinhof in a couple of clicks of the mouse. Once there, she would fall in love with them. Brilliant, beautiful, as glamorous as rock stars but doomed and destined to die for their cause. They have exercised a fascination for artists like Gerhard Richter and film makers: Uli Edel's Baader-Meihof Complex and Andres Veiel's recent If Not Us, Who? They exercise their lethal magic on Caro, too.

TINF is pretty strong stuff! Was there any passage that you found particularly difficult to write?

I found the end hard to write. I always knew how it would end, but when I came to writing it, I found it difficult to do.

I'm not surprised! It's a wonderful book. Thankyou, Celia!

This Is Not Forgiveness, Bloomsbury, £6.99

Published on March 21, 2012 02:41

March 19, 2012

"This Is Not Forgiveness" by Celia Rees

A warm welcome to Celia Rees, back on 'Steel Thistles' as part of the tour for her new book 'This Is Not Forgiveness' (Bloomsbury). Celia is not only a friend but a writer whose work I greatly admire - not least for the way she's always setting herself new challenges. Her last book, which I reviewed here, was a rethinking of Shakespeare's 'Twelfth Night'. This one is completely up-to-date. Twenty-first century Britain, warts and all.

I went to the funerals. They held them one after another. I don't think they meant them to be that way, but the crematorium was busy that day. Yours was second. Not much like the first. No orations, no weeping schoolmates clutching single blossoms to put on the coffin…No inky hand-printed notes on the flowers: R.I.P., C U in Heaven, Gone but not forgotten. No flowers at all. Hardly anyone there either. Only the bare minimum for decency. Police and immediate family. Some of your mates, but not many. Just Bryn and a few others, wearing uniform…

I went to the funerals. They held them one after another. I don't think they meant them to be that way, but the crematorium was busy that day. Yours was second. Not much like the first. No orations, no weeping schoolmates clutching single blossoms to put on the coffin…No inky hand-printed notes on the flowers: R.I.P., C U in Heaven, Gone but not forgotten. No flowers at all. Hardly anyone there either. Only the bare minimum for decency. Police and immediate family. Some of your mates, but not many. Just Bryn and a few others, wearing uniform…

This is not forgiveness. Don't think that.

Over the course of one hot summer, three young people's lives come together and trigger a chain reaction of dangerous events. There's Jamie, ready to fall in love, looking for his first sexual experience. There's Jamie's older brother Rob, a soldier invalided out of Afghanistan, macho, secretive, cynical and used to violence. And there's beautiful, complex, sexually magnetic Caro, who enjoys a spice of danger, who flirts with extremism, and who sleeps around – the kind of girl other girls dislike.

Jamie can hardly believe it when Caro begins sleeping with him. He tries hard to keep up – she's capricious, always springing surprises. But Caro is keeping more than one secret from him, and gradually Jamie begins to realise that his brother Rob knows Caro better than he'd guessed. Much better. And Caro and Rob are planning something which will end more terribly than even Caro ever imagined…

"This Is Not Forgiveness" is of course a fast-moving thriller – that goes without saying – but what I really loved about the book was the way Celia Rees writes about young people on the verge of growing up – some of them already damaged - desperate for experience, full of hope and full of cynicism. Jamie, getting ready to go out for the evening – 'Having a shower and a shave, getting my hair right, picking out clothes' – all of course in the hope that he's going to meet Her:

The day is tipping towards evening, the blue sky darkening, the streetlights coming on. It's warm. There are kids out playing on the front lawns, and the barbecues are on the go again. We walk quickly. I wave away the half bottle of vodka Cal takes from his pocket. I need to keep sharp. I don't want to get wasted in case I run into Caro.

I love that picture of the boys' sense of separateness from the world around them – their distance from the children they so recently were, the parental barbecues they would so recently have attended. Nothing to do with them now! Now they're young wolves, alone as only teenagers can be alone together. And of course, Jamie's evening runs its inevitable course from hope (anything is possible), through partial success (getting into a cool bar but only because the bouncer knows his brother), to isolation (not knowing anyone,not even having the nerve to talk to Caro when he sees her), aggression (when his brother picks a quarrel first with him and then with a stranger), and the final irony of getting together with Caro only because she needs help getting his drunken brother home over 'pavements slippery with vomit, the road glittery with glass, gutters strewn with kebab boxes spilling strips of discarded salad.' This is telling it how it is.

But there's also a tenderness to Celia Rees's writing. She never forgets how young her characters are, how vulnerable, how much they're testing themselves, trying to find out who they really are, and what might make life worth living. When Caro takes Jamie up a hill to see the full moon, her voice is authentically young, I think – talking solemn bullshit as if no one has ever done it before:

"I love it up here. … I love high places." She comes back to me and sits opposite, arms clasped around her bare legs. "This place is special, do you know that? I come here as often as I can. Different times of day. Sometimes in the very early morning. I come to catch the sun rising, or in the evening to see it set. I've been taking photographs, trying to capture the moment of transition, night to day, day to night. I like margins. It's different depending on the time of day, time of year. It can be weird, spooky here, especially in fog or mist, or when the clouds come down. You see things…"

If she were older it would sound pretentious: young as she is, it's completely natural. It makes me like her. (And of course the boy is impressed…)

Do read the book – it's not only wonderful, it's also explosively exciting. On Wednesday I'll be asking Celia some questions about 'This Is Not Forgiveness' – and on Friday she'll be talking about a fairytale which reflects one of the fundamental motifs of the book – the destructive trio of lovers.

"This Is Not Forgiveness" is published by Bloomsbury, £6.99

I went to the funerals. They held them one after another. I don't think they meant them to be that way, but the crematorium was busy that day. Yours was second. Not much like the first. No orations, no weeping schoolmates clutching single blossoms to put on the coffin…No inky hand-printed notes on the flowers: R.I.P., C U in Heaven, Gone but not forgotten. No flowers at all. Hardly anyone there either. Only the bare minimum for decency. Police and immediate family. Some of your mates, but not many. Just Bryn and a few others, wearing uniform…

I went to the funerals. They held them one after another. I don't think they meant them to be that way, but the crematorium was busy that day. Yours was second. Not much like the first. No orations, no weeping schoolmates clutching single blossoms to put on the coffin…No inky hand-printed notes on the flowers: R.I.P., C U in Heaven, Gone but not forgotten. No flowers at all. Hardly anyone there either. Only the bare minimum for decency. Police and immediate family. Some of your mates, but not many. Just Bryn and a few others, wearing uniform…This is not forgiveness. Don't think that.

Over the course of one hot summer, three young people's lives come together and trigger a chain reaction of dangerous events. There's Jamie, ready to fall in love, looking for his first sexual experience. There's Jamie's older brother Rob, a soldier invalided out of Afghanistan, macho, secretive, cynical and used to violence. And there's beautiful, complex, sexually magnetic Caro, who enjoys a spice of danger, who flirts with extremism, and who sleeps around – the kind of girl other girls dislike.

Jamie can hardly believe it when Caro begins sleeping with him. He tries hard to keep up – she's capricious, always springing surprises. But Caro is keeping more than one secret from him, and gradually Jamie begins to realise that his brother Rob knows Caro better than he'd guessed. Much better. And Caro and Rob are planning something which will end more terribly than even Caro ever imagined…

"This Is Not Forgiveness" is of course a fast-moving thriller – that goes without saying – but what I really loved about the book was the way Celia Rees writes about young people on the verge of growing up – some of them already damaged - desperate for experience, full of hope and full of cynicism. Jamie, getting ready to go out for the evening – 'Having a shower and a shave, getting my hair right, picking out clothes' – all of course in the hope that he's going to meet Her:

The day is tipping towards evening, the blue sky darkening, the streetlights coming on. It's warm. There are kids out playing on the front lawns, and the barbecues are on the go again. We walk quickly. I wave away the half bottle of vodka Cal takes from his pocket. I need to keep sharp. I don't want to get wasted in case I run into Caro.

I love that picture of the boys' sense of separateness from the world around them – their distance from the children they so recently were, the parental barbecues they would so recently have attended. Nothing to do with them now! Now they're young wolves, alone as only teenagers can be alone together. And of course, Jamie's evening runs its inevitable course from hope (anything is possible), through partial success (getting into a cool bar but only because the bouncer knows his brother), to isolation (not knowing anyone,not even having the nerve to talk to Caro when he sees her), aggression (when his brother picks a quarrel first with him and then with a stranger), and the final irony of getting together with Caro only because she needs help getting his drunken brother home over 'pavements slippery with vomit, the road glittery with glass, gutters strewn with kebab boxes spilling strips of discarded salad.' This is telling it how it is.

But there's also a tenderness to Celia Rees's writing. She never forgets how young her characters are, how vulnerable, how much they're testing themselves, trying to find out who they really are, and what might make life worth living. When Caro takes Jamie up a hill to see the full moon, her voice is authentically young, I think – talking solemn bullshit as if no one has ever done it before:

"I love it up here. … I love high places." She comes back to me and sits opposite, arms clasped around her bare legs. "This place is special, do you know that? I come here as often as I can. Different times of day. Sometimes in the very early morning. I come to catch the sun rising, or in the evening to see it set. I've been taking photographs, trying to capture the moment of transition, night to day, day to night. I like margins. It's different depending on the time of day, time of year. It can be weird, spooky here, especially in fog or mist, or when the clouds come down. You see things…"

If she were older it would sound pretentious: young as she is, it's completely natural. It makes me like her. (And of course the boy is impressed…)

Do read the book – it's not only wonderful, it's also explosively exciting. On Wednesday I'll be asking Celia some questions about 'This Is Not Forgiveness' – and on Friday she'll be talking about a fairytale which reflects one of the fundamental motifs of the book – the destructive trio of lovers.

"This Is Not Forgiveness" is published by Bloomsbury, £6.99

Published on March 19, 2012 00:59

March 16, 2012

Our Craft or Sullen Art

IN MY CRAFT OR SULLEN ART

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labor by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

Dylan Thomas

I used to memorise poems. I got drunk on words: I muttered them under my breath while waiting for buses; I repeated them at night – poem after poem - to send myself sliding away on a raft of poetry down a river of dreams. Actually I still do.

Dylan Thomas's poems ask to be chanted aloud. They fill the mouth and roll off the tongue like thunder:

"Altarwise by owl-light in the halfway house

The gentleman lay graveward with his furies."

Whatever does it mean? I have no idea. I simply know it sounds good. Better than good. Grand - restorative - like wonderful spells. And when I first came across this poem, back in the 1970's, to be fair, there was a fashion for obscure poetry; almost every glam-rock album could do the mysteriously evocative stuff. Look at early Genesis! I wasn't that bothered about the meaning: I was listening to the music. Even then I think I did prefer those poems I could also make sense of – the luminous 'Fern Hill' or 'Poem in October': but meaning was – for me, then – secondary to music.

Nowadays, though I still love the music, I look for meaning too. And behold, it's there, and now I understand it a little bit better.

"My craft, or sullen art." How honest that adjective is: 'sullen': because writing can be so hard, so difficult – so damned uncooperative! You try and you try, and it's not good enough, still not good enough, but you keep trying. You keep on trying because what you're really aiming for, what you want the most – and he's right, he's so right – is not money, not 'ambition or bread', not fame: 'the strut and trade of charms/On the ivory stages'. No.

We don't write for the critics. We don't write (how could we dare - though maybe Thomas dared?) with an eye on posterity and the hope of joining the ranks of 'the towering dead with their nightingales and psalms'. We don't write for fame. We don't write because we dream of getting rich, and most of us certainly don't. We write for the love of the craft - and we're grateful to anyone who reads us from the crowds of all those heedless, living and breathing human beings getting on with life. We write for 'the common wages of the secret heart.'

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labor by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

Dylan Thomas

I used to memorise poems. I got drunk on words: I muttered them under my breath while waiting for buses; I repeated them at night – poem after poem - to send myself sliding away on a raft of poetry down a river of dreams. Actually I still do.

Dylan Thomas's poems ask to be chanted aloud. They fill the mouth and roll off the tongue like thunder:

"Altarwise by owl-light in the halfway house

The gentleman lay graveward with his furies."

Whatever does it mean? I have no idea. I simply know it sounds good. Better than good. Grand - restorative - like wonderful spells. And when I first came across this poem, back in the 1970's, to be fair, there was a fashion for obscure poetry; almost every glam-rock album could do the mysteriously evocative stuff. Look at early Genesis! I wasn't that bothered about the meaning: I was listening to the music. Even then I think I did prefer those poems I could also make sense of – the luminous 'Fern Hill' or 'Poem in October': but meaning was – for me, then – secondary to music.

Nowadays, though I still love the music, I look for meaning too. And behold, it's there, and now I understand it a little bit better.

"My craft, or sullen art." How honest that adjective is: 'sullen': because writing can be so hard, so difficult – so damned uncooperative! You try and you try, and it's not good enough, still not good enough, but you keep trying. You keep on trying because what you're really aiming for, what you want the most – and he's right, he's so right – is not money, not 'ambition or bread', not fame: 'the strut and trade of charms/On the ivory stages'. No.

We don't write for the critics. We don't write (how could we dare - though maybe Thomas dared?) with an eye on posterity and the hope of joining the ranks of 'the towering dead with their nightingales and psalms'. We don't write for fame. We don't write because we dream of getting rich, and most of us certainly don't. We write for the love of the craft - and we're grateful to anyone who reads us from the crowds of all those heedless, living and breathing human beings getting on with life. We write for 'the common wages of the secret heart.'

Published on March 16, 2012 01:51

March 12, 2012

On the Vernacular Voice

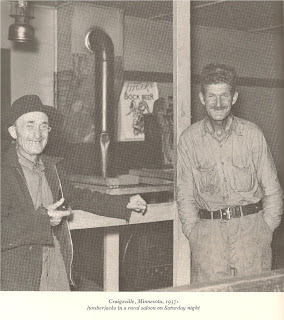

Rural Minnesota 1937: lumberjacks in a saloonThere've been a number of books written on what you might call the Huck Finn or Riddley Walker principle: written, that is, in the first person voice of an uneducated but lively narrator. You can think of plenty, I'm sure - but Patrick Ness's Chaos Walking trilogy springs to mind, as does Moira Young's 'The Blood Red Road' and Caroline Lawrence's 'The Case of the Deadly Desperadoes' - and I'm wrestling with one myself which should see the light of day in a year or so.

Rural Minnesota 1937: lumberjacks in a saloonThere've been a number of books written on what you might call the Huck Finn or Riddley Walker principle: written, that is, in the first person voice of an uneducated but lively narrator. You can think of plenty, I'm sure - but Patrick Ness's Chaos Walking trilogy springs to mind, as does Moira Young's 'The Blood Red Road' and Caroline Lawrence's 'The Case of the Deadly Desperadoes' - and I'm wrestling with one myself which should see the light of day in a year or so. It's not an easy thing to do, so it's good to look outside fiction at the real thing from time to time.

In a book called 'Folklore on the American Land' by Duncan Emrich (which I blogged about a couple of years ago in a post called 'Knee Deep in August'), Chapter Four is given over to what he calls 'A Manuscript of the Folk Language' written by 'a gentleman by the name of Samuel M Van Swearengen' whom he met while researching folk songs -

- in the Windsor Hotel on Denver's Larimer Street. The Windsor, as anyone who lived in Denver at the time knows, was the most elegant hostelry on skid row. To it flocked old prospectors…cowboys who remembered the days of the long trails north from texas, one time gamblers who spoke of dust and thousands, and old age pensioners who qualified for the munificent largesse of the state of Colorado. Sam Van Swearengen was one of those last. …He had been born in Chariton County, Missouri, in 1869, and was seventy-two years old in the Denver of 1941.

Emrich and Sam got friendly. "He was lonely, and my wife and I gradually became his 'children' - he so addressed us in letters" - and after a while Sam diffidently handed Emrich a manuscript he'd been typing out about his own life. Here is the beginning exactly as typed:

In Writing This Book I Have Carictorized It In The Best Manner Posible For Me To Remenber As I Am A Man of 66. Years Of Age And Did Never Keep No Dairie Of The Dayley Happenings As I Should Of Did But Nevver Thinking Of Writing This Book, I Just Have To Go Back In Memory As Fare As Posible And Give The Facts As Best I Can Remember I Was Born In Chariton County Misouri on January 19Th 1899. And Whas About 18 Mounths Old When My Mother Died She Died Leaving My Self And My Little Baby Brother Ho Whas About Two Mounths Old At Her Death, And My Father Not Beeing Very Well Fixed With The Necesary Things Of Life My Grand Parrents Taken Me And My Brother To Raise And Everything Went Good Tell About Four Years Later My Grand Mother Died Leaving US To The Murcy And Care Of Aunts And Uncle As For Whitch Had No Experience In Raising Of Children And Some Of Them Whas Only Children Them Selves

Emrich says,

I forgot about folk songs and encouraged Van Swearengen to go ahead and beat out some more of his life on his old turret-revolving Oliver typewriter, a relic salvaged from earlier, dining car days on the railroad. Even with the problem of capitals, to which he clung, and an aged hunt-and-peck system, the work progressed more rapidly for him than if he had attempted writing in a slow, longhand scrawl. Writing with pen and paper was labor. His schooling had been small.

(I can attest to this from my experience with Jean, see my post on 'The Power of Story'.)

Texas schoolboys, 1943

Texas schoolboys, 1943In all, Sam's manuscript ran to 272 single spaced pages, and covered his whole life from birth and boyhood on. Emrich continues:

He covers his life on the farm in Missouri, his brief schooling, his boyhood pleasures trapping and duck-hunting, and the hardships of his early days. He reviews his various jobs as a young man: making barrel hoops, work on the railroad, a job at the Armour plant in Kansas City, his 'corear' as butcher and grocer, work as a dining car steward. He tackles his marital problems with candor: "How The Holy Roolers Stole My Wife." … And he closes the manuscript with some fine, wild haymakes directed at hypocritical church people and the government of Colorado…

Here are some extracts, punctuated by Emrich and with capitals reduced.

The Wild Irish Minister at the Country School House.

Well I remember, in pioneer days in old Mo, when thire whas a church in about every hundred squire miles, and in them days the school houses whas used extencivley for religious services. And the people all knew automaticly the church days for certain ministers, and thay would all hitch up thayer ox teaims and some times start before day light on Sundays to church…

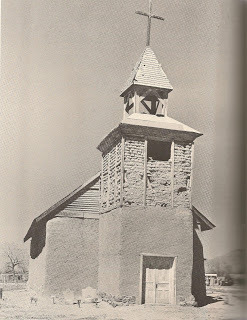

Adobe church, New Mexico, with graves

Adobe church, New Mexico, with graves[There was] a minister widely known as the Wild Irishman. His name reaily wear Charley Davis but he whas known greater by his alias name as the Wild Irishman. And in them days I guess he whas thought to be the top minister, for it seemed that everybody that whas church inclined whould try to hear him, and would pour in for miles around.

However, the Wild Irishman liked his tipple, especially Sam's grandfather's moonshine whisky.

And, of corse, this old Irish minister whas a full fledged Irishman...and if you know the Irish, you know what thay railly do like. And it has occurred to me that if thay will not pertake of the forbidden fruit, that he is not a full fledged Irishman. And I never will forget a old German man that used to go to hear the Wild Irishman preach. And at this special time the old German happened to be thire, and sed when the Wild Irishman got started, 'he schust could show you Jesus Christ and the angels chust flooting in the air.' And thire was the throne of God as plain as if it whas. And he showed them all the conveniences that a man had what was a church member, and shoed them all the different departments that thire was in haven. He showed the departments whire the people whas kept that had never sinned, and whire the people was held that had sined just a little, and whire the people was kept that had bin sinners tell thay foundout that that wear going to die. And that preacher told them that thay whas punished according to his deeds, and told them that the less a man sined, the less he whas punished. And he then, in return, showed them hell and showed them what a terrible place hell wear. And he [the old German] said, "Vell, I shust could see hell and de devell shust as plain as if I wear reaily in hell." And I will admit my self he could show you a picture of things tell thire would be sompthing funny about it. But he nevver could nor he never would undertake this untell he whas just three sheets in the wind.

And that, my fellow writers, is what we're aiming at, though in my opinion Mr Samuel M Van Swearengen has us beat, hands down. His narrative voice is not naïve, even if it may sound that way at first. We should beware if we suppose that. It's a rich voice, a voice of wisdom and humour, the voice of a man who knows exactly who he is and exactly what he thinks, and has a wealth of experience to draw on that most of us will never match.

All photos from Duncan Emrich's book 'Folklore on the American Land'

Published on March 12, 2012 01:55

March 10, 2012

Folklore Snippets - The Grav-so or Ghoul

Apologies for being absent from 'Steel Thistles' for so long! I lost internet access for TEN DAYS and have been going justabout crazy with frustration. I won't fill you in on the long sorry story of phone call after phone call to a disbelieving server and a lethargic and disingenuous British Telecom, but finally I'm back. Without more ado, here's a nice little story about a Ghoul.

THE GRAV-SO or GHOUL

From "Scandinavian Folklore" ed William Craigie

This monster is properly a treasure-watcher, and lies and broods over heaps of gold. For the most part it has its dwelling in mounds, where a light is seen burning at by night, and it is known then that the treasure lies there. If anyone digs for it, he may always be certain of meeting a ghoul, and that is hard to deal with. Its back is as sharp as a knife, and it is seldom that anyone escapes from it alive. As soon as anyone begins to dig in the mound, it comes out and says, "What are you doing there?" The treasure hunter must answer, "I want to get a little money, and it's that I am digging for, if you won't be angry." With this the ghoul must content itself, and they make a bargain. "If you are finished," it says, "when I come for the third time, then all you find is yours, but if you are not finished by then, I shall spring upon you and destroy you."

If the man has courage to make this compact, he must lose no time, for if the ghoul comes for the third time before he has finished, it runs between his legs and splits him in two with its sharp back. Old Peter Smith in Taaderup, who is now dead, had the reputation for having got his wealth in this fashion: he and another young fellow were desirous of digging for treasure, and went one night to a mound where they knew that there was a ghoul. When they began to dig, it came up and asked what they wanted, and then fixed a certain time within which they were to be finished. They worked now with all their might, and finally got hold of a big chest which they dragged out as fast as they could, but before they had got quite clear of the mound - Peter Smith still had one of his legs in the hole - the ghoul came for the third time and managed to rub itself against Peter's legs. Although it only touched him slightly, he had got enough for all his life, for however wealthy he was, his legs were always so feeble he could neither stand nor walk.

THE GRAV-SO or GHOUL

From "Scandinavian Folklore" ed William Craigie

This monster is properly a treasure-watcher, and lies and broods over heaps of gold. For the most part it has its dwelling in mounds, where a light is seen burning at by night, and it is known then that the treasure lies there. If anyone digs for it, he may always be certain of meeting a ghoul, and that is hard to deal with. Its back is as sharp as a knife, and it is seldom that anyone escapes from it alive. As soon as anyone begins to dig in the mound, it comes out and says, "What are you doing there?" The treasure hunter must answer, "I want to get a little money, and it's that I am digging for, if you won't be angry." With this the ghoul must content itself, and they make a bargain. "If you are finished," it says, "when I come for the third time, then all you find is yours, but if you are not finished by then, I shall spring upon you and destroy you."

If the man has courage to make this compact, he must lose no time, for if the ghoul comes for the third time before he has finished, it runs between his legs and splits him in two with its sharp back. Old Peter Smith in Taaderup, who is now dead, had the reputation for having got his wealth in this fashion: he and another young fellow were desirous of digging for treasure, and went one night to a mound where they knew that there was a ghoul. When they began to dig, it came up and asked what they wanted, and then fixed a certain time within which they were to be finished. They worked now with all their might, and finally got hold of a big chest which they dragged out as fast as they could, but before they had got quite clear of the mound - Peter Smith still had one of his legs in the hole - the ghoul came for the third time and managed to rub itself against Peter's legs. Although it only touched him slightly, he had got enough for all his life, for however wealthy he was, his legs were always so feeble he could neither stand nor walk.

Published on March 10, 2012 01:17

February 27, 2012

"Strange Neighbours" by Masha du Toit

Strange Neighbours is a collection of ten illustrated fantasy short stories set in Cape Town, South Africa. Meet a hitch hiking troll with a taste for pepper-spray and a homeless witch with a trolley full of secrets. Discover a book hoarding mermaid and a fridge full of frogs. And learn how to greet a witch – politely, of course.

Now here's a lovely and unusual collection. Masha du Toit is a South African artist and writer, who has written and illustrated an e-book of delicate fantasy stories for adults (though there is nothing actually unsuitable for younger readers, these are not aimed at children) called 'Strange Neighbours'. In them, quiet, ordinary people come face to face with all kinds of weird situations - and often behave with inspiring humanity and aplomb.

In 'In the Backyard' a young man who's inherited a small house begins to wonder why the back door has been so very securely locked and barred 'like Fort Knox', when all that's out there is a weedy yard and a broken manhole cover. And why is the shed so full of various poisons and traps?

'Kelp' is a moving tale about a lonely young woman who comes to visit the seaside in Cape Town, falls ill and is helped in by an old woman who scratches a living selling old books and magazines, and who lives in a shack under the pier. But there's something very strange and sad about her...

Aletta drifted in and out of consciousness. A small paraffin lamp glowed in a corner. The sea made deep sounds beyond the walls. Then she had to sit up and clutch at a glass and drink bitter liquid.

She woke, or dreamed she woke, in the dark.

Sea air breathed over her, cold and wet. A gap had opened in the wall opposite her bed. Something moved there. A figure, barely visible in glints of dim light. Something like a scarf was wrapped about its neck. Long fringes stirred against its shoulders. Then it ducked down and stepped through into the night beyond. The dream darkened and sucked Aletta back into sleep.

In 'The Ink Witch' an ostracised schoolgirl - who may have strange powers - appears to deal with her chief tormentor in a decisive and final way - and even if it's all only 'strong imagination', the story is a warning to those who crush the imagination and teach their victims to hate. In 'Troll Patrol' a woman driver helps a very unusual fugitive to escape the police. And in 'In The Oven' a young girl visits her grandmother and bakes gingerbread men which come to life in the oven. Trying to save them, she drops one:

The man had lost a leg now, but it was still alive, twitching sideways along the floor. Why couldn't he just lie there in his baking tray like he was supposed to? Now he'd made her hurt him. Maybe she could put its leg back on. But it was quite crushed, just a little pile of doughy crumbs. The man flipped himself over and lay on his back.

She knew what she had to do. It was like that time she had found a baby bird that had fallen out of its nest...

There are more. I enjoyed every one of them. Whilst recognizing and acknowledging cruelty and pain, these sour-sweet stories offer hope and refuse to despair. You can buy the e-book if you click on this link: Strange Neighbours and visit Masha's website to find out more about her writing and see more of her beautiful art.

Teaset with dragon - Masha du Toit

Teaset with dragon - Masha du ToitMasha du Toit is an artist and writer living in Cape Town, South Africa. She illustrates stories that don't exist yet, and writes about unexpected magic in every-day situations. She's inspired by folk- and fairy tales, puppetry, and spur-of-the-moment bed time stories. She's about to publish a full length e-book "The Story Trap".

All pictures copyright Masha du Toit

Published on February 27, 2012 00:05

February 20, 2012

The Power of Story

A few years ago when I was living in upstate New York I joined Literacy Volunteers of America and began teaching basic reading, writing and arithmetic to a lady in her middle fifties whom I'll call Jean - not her real name. She was a brilliant pupil, endlessly fascinated by learning. "Gee Katherine, the things you tell me are so inneresting," she'd exclaim, after I'd explained something like the concept of the plural - or the idea that you could make a drawing of the neighbourhood into a flat plan called a map.

In my diary I wrote:

Jean gave me a huge hug as soon as we met. She never went to school beyond kindergarten. She's pale, her grey hair strained back in a ponytail. Several of her lower teeth are missing so she lisps a little as she speaks. Her nails are bitten down and she smells of cigarette smoke - even her work smells of this. She wears a dainty set of earrings though, and always looks neat. Indeed her work is neat - she writes in pencil and hastily rubs out and corrects any letter she judges to be too far above the line.

I ask, "How come you never went to school, Jean?" She answers in her rather gruff voice, "Well, when I wuz seven I got polio 'n they put me in a Home. I would'n' want ta tell you 'bout that, Katherine. They beat up on us, hit us over the head - we didn' learn nuthin."

She cleans somewhere. Lives with her friend Joe since his sister died. She obviously adores him. He's older than her, a veteran in his seventies, who told her she needed to learn to do things by herself (because he's dying of lung cancer). He fell down a while ago, slid across a floor, hit his head against a door.

"He got a big goose bump," recalls Jean, "'n I said to him, 'Well I can do that for you, I can hit you over the head with a frying pan.' He says, 'Thanks Jeanie.' 'N he asked the landlord, he says for him to put soft doors in. He always makes a joke of it. He says, 'Well I don't want to go round thinkin' 'bout dyin' (she pulls her chin down) 'with a face like a cow that hasn't been milked.'"

Jean's reading level was very basic, around that of a child of six. She could spell out words slowly, but might miss the point of a sentence because by the time she got to the end of it she'd forgotten how it began. Her understanding of anything she read was therefore poor, and I began buying her simple early reader books with pictures, especially if they had anything to do with American history, which she was eager to learn about. And pretty soon I also realised she loved dogs. The story of Balto, the sled dog who helped bring vital medical supplies to Nome, Alaska, was a big hit with her, therefore - and probably her favourite until I found another dog story: this time about Buddy, the first American 'Seeing Eye' dog.

Buddy, the First Seeing Eye Dog by Eva Moore and Don Bolognese

Buddy, the First Seeing Eye Dog by Eva Moore and Don Bolognese

To see Jean take this little book to her heart was to see the power of story turned up high. C.S. Lewis once provocatively argued (in 'An Experiment in Criticism') that since all criticism is subjective, the only criterion for telling if a book was 'good' should be the way in which it is read. If even a single person would read and re-read a book, 'and notice and complain' if anything was changed, then we should assume that book has a richness of quality for them even if we can't ourselves detect it, and should hesitate to dismiss it.

On that level this short book was a masterpiece. For me it was a nice little story about a man and his dog. For Jean it was something deeply, deeply moving. She read it so often she could quote whole sentences by heart. The best bit was in the middle. Buddy's blind owner is travelling to Europe on an ocean liner, and he's lying in his cabin unaware of the fact that he's dropped his wallet somewhere on the deck, when his dog Buddy comes up and nudges him, the wallet in his mouth. The owner rubs the dog's head and praises him. "Buddy," he says, "You're worth more to me than all the money in the world."

Jean would read this aloud and her eyes would brim with tears. Her voice would shake. "You're worth more to me than any money in the world, Buddy." Jean knew the value of money. She didn't have much of it. But she knew love was worth so much more.

Took Jean to lunch the other day. We each had a gyro at the Ice Cream Works on Market Street - she'd never had one before but thought it delicious. (Typical Jean to be bold and try something new!) I asked how Joe was; he won't have treatment for his cancer because he 'doesn't want to be a guinea pig', and looks terribly thin and keeps falling. What a charmer he is, though so ill. He told me he used to work for the Mafia - he means this - said one of the guys who lived on the hill offered him several thousand dollars to kill 'his old man' but Joe refused… And now he's a frail old man with a puckish sense of humour. He and Jean score off each other all the time. She thinks the world of him. At the moment she's paying off $40 on a pewter clock shaped like a merry-go-round horse, which she'll give to Joe as a late birthday present once she's paid it all (at $5 a week). My hope is that he lives to receive it. "He's worth it," she says.

Well, Joe died, and luckily the town found somewhere for Jean to live, and I left America for England. It was a wrench to say goodbye. Here's one of her letters to me, written in her careful curling pencil script which I know will have taken her ages to write:

Dear Katherine,I am writing you this letter to you to say hi. How are you and your family are doing. I am doing good. I miss you and your family. Merry Christmas happy new years. ...I wish I can see you. I have been learning on spelling words and math and reading and writing. I have been working on crafts. I have been learning a lots of different things. I learn on my budget all my friends said to me how I come along way. They are glad I came along way. They told me to keep up and don't give up. I told them I wont give up I will keep on going. I am going to keep on doing good for myself. I am going to make myself happy. …What happens to your first dog you had she was a sweet dog. I did like her so much. She was a sweet dog. I am learning on the computer I learn a lot on it.turnover… I got new curtains in my front room. They are blue goes with my furniture. I got to go for now. Love Jean

Lovely, indomitable Jean, I miss you too.

In my diary I wrote:

Jean gave me a huge hug as soon as we met. She never went to school beyond kindergarten. She's pale, her grey hair strained back in a ponytail. Several of her lower teeth are missing so she lisps a little as she speaks. Her nails are bitten down and she smells of cigarette smoke - even her work smells of this. She wears a dainty set of earrings though, and always looks neat. Indeed her work is neat - she writes in pencil and hastily rubs out and corrects any letter she judges to be too far above the line.

I ask, "How come you never went to school, Jean?" She answers in her rather gruff voice, "Well, when I wuz seven I got polio 'n they put me in a Home. I would'n' want ta tell you 'bout that, Katherine. They beat up on us, hit us over the head - we didn' learn nuthin."

She cleans somewhere. Lives with her friend Joe since his sister died. She obviously adores him. He's older than her, a veteran in his seventies, who told her she needed to learn to do things by herself (because he's dying of lung cancer). He fell down a while ago, slid across a floor, hit his head against a door.

"He got a big goose bump," recalls Jean, "'n I said to him, 'Well I can do that for you, I can hit you over the head with a frying pan.' He says, 'Thanks Jeanie.' 'N he asked the landlord, he says for him to put soft doors in. He always makes a joke of it. He says, 'Well I don't want to go round thinkin' 'bout dyin' (she pulls her chin down) 'with a face like a cow that hasn't been milked.'"

Jean's reading level was very basic, around that of a child of six. She could spell out words slowly, but might miss the point of a sentence because by the time she got to the end of it she'd forgotten how it began. Her understanding of anything she read was therefore poor, and I began buying her simple early reader books with pictures, especially if they had anything to do with American history, which she was eager to learn about. And pretty soon I also realised she loved dogs. The story of Balto, the sled dog who helped bring vital medical supplies to Nome, Alaska, was a big hit with her, therefore - and probably her favourite until I found another dog story: this time about Buddy, the first American 'Seeing Eye' dog.

Buddy, the First Seeing Eye Dog by Eva Moore and Don Bolognese

Buddy, the First Seeing Eye Dog by Eva Moore and Don BologneseTo see Jean take this little book to her heart was to see the power of story turned up high. C.S. Lewis once provocatively argued (in 'An Experiment in Criticism') that since all criticism is subjective, the only criterion for telling if a book was 'good' should be the way in which it is read. If even a single person would read and re-read a book, 'and notice and complain' if anything was changed, then we should assume that book has a richness of quality for them even if we can't ourselves detect it, and should hesitate to dismiss it.

On that level this short book was a masterpiece. For me it was a nice little story about a man and his dog. For Jean it was something deeply, deeply moving. She read it so often she could quote whole sentences by heart. The best bit was in the middle. Buddy's blind owner is travelling to Europe on an ocean liner, and he's lying in his cabin unaware of the fact that he's dropped his wallet somewhere on the deck, when his dog Buddy comes up and nudges him, the wallet in his mouth. The owner rubs the dog's head and praises him. "Buddy," he says, "You're worth more to me than all the money in the world."

Jean would read this aloud and her eyes would brim with tears. Her voice would shake. "You're worth more to me than any money in the world, Buddy." Jean knew the value of money. She didn't have much of it. But she knew love was worth so much more.

Took Jean to lunch the other day. We each had a gyro at the Ice Cream Works on Market Street - she'd never had one before but thought it delicious. (Typical Jean to be bold and try something new!) I asked how Joe was; he won't have treatment for his cancer because he 'doesn't want to be a guinea pig', and looks terribly thin and keeps falling. What a charmer he is, though so ill. He told me he used to work for the Mafia - he means this - said one of the guys who lived on the hill offered him several thousand dollars to kill 'his old man' but Joe refused… And now he's a frail old man with a puckish sense of humour. He and Jean score off each other all the time. She thinks the world of him. At the moment she's paying off $40 on a pewter clock shaped like a merry-go-round horse, which she'll give to Joe as a late birthday present once she's paid it all (at $5 a week). My hope is that he lives to receive it. "He's worth it," she says.

Well, Joe died, and luckily the town found somewhere for Jean to live, and I left America for England. It was a wrench to say goodbye. Here's one of her letters to me, written in her careful curling pencil script which I know will have taken her ages to write:

Dear Katherine,I am writing you this letter to you to say hi. How are you and your family are doing. I am doing good. I miss you and your family. Merry Christmas happy new years. ...I wish I can see you. I have been learning on spelling words and math and reading and writing. I have been working on crafts. I have been learning a lots of different things. I learn on my budget all my friends said to me how I come along way. They are glad I came along way. They told me to keep up and don't give up. I told them I wont give up I will keep on going. I am going to keep on doing good for myself. I am going to make myself happy. …What happens to your first dog you had she was a sweet dog. I did like her so much. She was a sweet dog. I am learning on the computer I learn a lot on it.turnover… I got new curtains in my front room. They are blue goes with my furniture. I got to go for now. Love Jean

Lovely, indomitable Jean, I miss you too.

Published on February 20, 2012 00:50

February 17, 2012

The Snow Queen

by Katherine Roberts

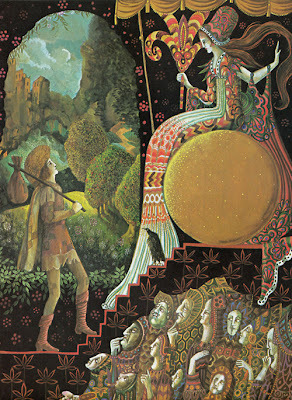

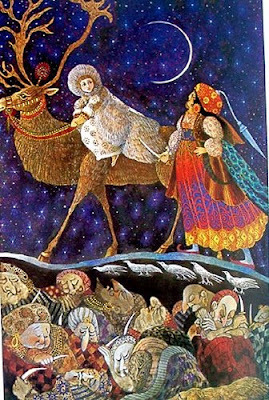

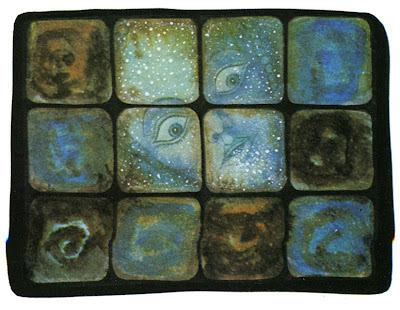

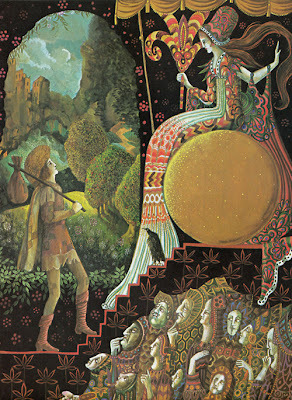

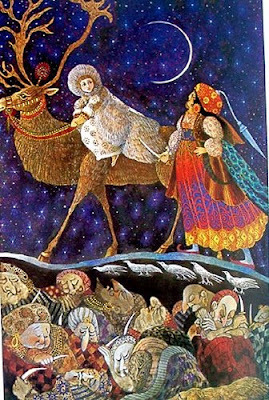

Hans Christian Andersen's "The Snow Queen" has haunted me all my life, so I was delighted when Kath gave me an excuse to revisit this one. It's a fairly complex fairytale, with its story of Kai who gets a splinter of the devil's mirror in his eye, rejects his sweetheart Gerda, and runs away with the Snow Queen. But like all the old tales, there are layers of meaning hidden under the story too. I think that's what makes them endure over the years, so I hope you'll be interested in my personal interpretation.

As a little girl I enjoyed the story mostly for its adventure and magic. Living in the southwest of England, Torbay in Devon, where we seldom see snow even in the coldest winters, I also liked the otherworldly beauty of the snowy mountains and the enchantment of the Snow Queen's ice palace – see, I was a budding fantasy writer even then! I remember the book I owned as a child (now sadly lost) had a beautiful full-colour picture of the Snow Queen dressed in white fur, driving her sleigh pulled by prancing white horses with silver bells on their harness through the Northern Lights across a winter's sky. Being pony crazy, I think it was probably these horses that drew me to the story initially. I never much liked later versions where the horses were replaced by reindeer or swans, or – as in the DVD version I have starring Bridget Fonda – an engine! Talk about destroying the magic…

But back to the story. As soon as I discovered that in this fairytale it is the boy – Kai – who gets kidnapped, and the girl – Gerda – who sets out on a quest to rescue him, I was hooked. After all those sugary little princess stories, here was a true heroine setting out on her own adventures! (I was Gerda, of course.) My memory of the actual adventures Gerda had on her quest is hazy, and I know these are often edited for simplicity, so maybe that's why. The version of the tale I re-read for this post has Gerda encountering a witch living in a cottage in the woods who tries to keep her as her own little girl, then a princess with a long line of suitors seeking her hand who tries to marry her off, followed by a robber girl who supplies her with a reindeer, and finally two old women – a Lapp and a Finn – living alone in the snow, who feed and warm Gerda on her journey. The DVD version leaves out the Lapp and Finn women entirely, linking each of Gerda's encounters to a different season so that she journeys through spring, summer, and autumn to find winter and the Snow Queen. I don't think the details really matter. However, I do think that, on a deeper level, Gerda's quest represents the stages of womanhood she will travel through in the world and perhaps that's why this fairytale speaks to me so strongly.

This is how I see Gerda's journey:

Spring – In the witch's cottage, Gerda is cared for and allowed to play in the garden but is forbidden to step outside the gate into the dangerous wood. The witch banishes all the roses that might remind her of Kai and does everything she can to keep the little girl from continuing her quest. Having a clingy mother myself, I can identify only too well with this stage. Even now, my mother seems unable to accept that I might want to open that gate and have adventures of my own in the big wide world.

Summer – At the Princess' palace, Gerda at first thinks Kai is the prince, and is disappointed when he turns out to be a stranger. In my DVD version a line of charming suitors try to win her hand, but Gerda rejects them all and escapes. This season represents the young and fertile woman chased by boys and making herself beautiful for them. It seems summer will last forever, with its dances and its roses and its declarations of love. But it is over all too soon.

Autumn – Here, I see the robber girl and her bandit mother representing the menopause, when a woman has finished with being a wife and mother and is beginning to find her own way in the world, coming into her power. It might be the autumn of her life, but autumn is a period of fruitfulness and harvest where the seeds sown in spring that blossomed in summer are ripening. Here, Gerda finds strength she didn't know she had and escapes by riding the robber girl's reindeer.

Winter – The Finn and Lapp women, living alone in their modest, cosy houses isolated in the snow, represent old age. They help Gerda, but warn her that if she chooses to continue her quest she must leave the reindeer and go on alone. This last part of her journey represents death, which everyone must face alone.

Finally, Gerda reaches the Snow Queen's palace, where she finds Kai trying to form a word out of shards of ice. The word is LOVE, but Kai's heart has been turned to ice by the Snow Queen's kiss, and the splinter of the devil's mirror in his eye means he cannot complete the puzzle. (In the DVD version, Kai's task is to reassemble the actual mirror). Of course he cannot do it, until Gerda kisses him and melts his heart. He weeps with joy at seeing her, and the splinter comes out of his eye. Like all fairytales, it is a happy ending. Kai completes his impossible task, winning his freedom from the Snow Queen, and the two young people return to their rose garden, where (one imagines) they got married and had a gloriously happy life bringing up their own children with the advantage of the lessons they have both learnt… I like to think so, anyway!

The splinter in Kai's eye is a powerful image. The devil – or hobgoblin or elf – made this mirror to reflect beautiful things as ugly and make ugly things seem normal. It's very true that the way you look at something can change completely the way you see life, and I've certainly gone through phases myself when a splinter of the devil's mirror gets lodged in my eye, and I have to make a conscious effort to squeeze it out before I can see the good around me.

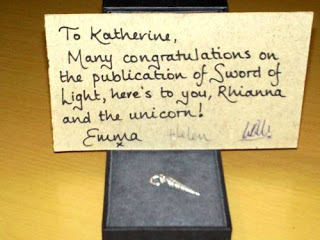

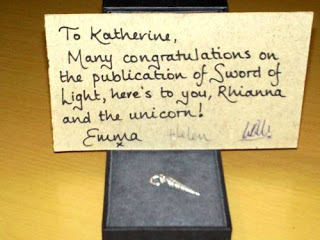

Breaking a mirror is also very symbolic, bringing seven years of bad luck according to some. I broke a large mirror seven years ago… of course I'm not superstitious AT ALL, but it is rather spooky how, after almost seven years of being out in the cold as an author following the death of my agent, this year sees the publication of a brand new quest for my readers beginning with "Sword of Light". And happily, I've no need to worry about breaking another mirror, since my lovely editors at Templar sent me this silver unicorn horn as a publication day present, which as everyone knows is a powerful charm against bad luck…

Katherine Roberts grew up in the wild, rocky counties of Devon and Cornwall with their brooding moors and rugged coasts. She gained a first class degree in mathematics from Bath University, and went on to work as a mathematician, computer programmer, racehorse groom and farm labourer - before her first novel, 'Spellfall', won the Branford Boase Award in 1999 and enabled her to fulfil her dream of becoming a full time writer. Her many fantasy books for children and young adults include 'The Echorium Sequence' (beginning with Song Quest), 'The Seven Fabulous Wonders' series of historical fantasies (beginning with 'The Pyramid Robbery'), and 'I Am The Great Horse', the story of Alexander the Great told by his famous horse Bucephalus.

Katherine's latest book, 'Sword of Light', the first of four Arthurian fantasies for children, has just been published by Templar.

Katherine's latest book, 'Sword of Light', the first of four Arthurian fantasies for children, has just been published by Templar.

Visit Katherine's website!

Picture credits: images from The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen, illustrated by Errol le Cain

Hans Christian Andersen's "The Snow Queen" has haunted me all my life, so I was delighted when Kath gave me an excuse to revisit this one. It's a fairly complex fairytale, with its story of Kai who gets a splinter of the devil's mirror in his eye, rejects his sweetheart Gerda, and runs away with the Snow Queen. But like all the old tales, there are layers of meaning hidden under the story too. I think that's what makes them endure over the years, so I hope you'll be interested in my personal interpretation.

As a little girl I enjoyed the story mostly for its adventure and magic. Living in the southwest of England, Torbay in Devon, where we seldom see snow even in the coldest winters, I also liked the otherworldly beauty of the snowy mountains and the enchantment of the Snow Queen's ice palace – see, I was a budding fantasy writer even then! I remember the book I owned as a child (now sadly lost) had a beautiful full-colour picture of the Snow Queen dressed in white fur, driving her sleigh pulled by prancing white horses with silver bells on their harness through the Northern Lights across a winter's sky. Being pony crazy, I think it was probably these horses that drew me to the story initially. I never much liked later versions where the horses were replaced by reindeer or swans, or – as in the DVD version I have starring Bridget Fonda – an engine! Talk about destroying the magic…

But back to the story. As soon as I discovered that in this fairytale it is the boy – Kai – who gets kidnapped, and the girl – Gerda – who sets out on a quest to rescue him, I was hooked. After all those sugary little princess stories, here was a true heroine setting out on her own adventures! (I was Gerda, of course.) My memory of the actual adventures Gerda had on her quest is hazy, and I know these are often edited for simplicity, so maybe that's why. The version of the tale I re-read for this post has Gerda encountering a witch living in a cottage in the woods who tries to keep her as her own little girl, then a princess with a long line of suitors seeking her hand who tries to marry her off, followed by a robber girl who supplies her with a reindeer, and finally two old women – a Lapp and a Finn – living alone in the snow, who feed and warm Gerda on her journey. The DVD version leaves out the Lapp and Finn women entirely, linking each of Gerda's encounters to a different season so that she journeys through spring, summer, and autumn to find winter and the Snow Queen. I don't think the details really matter. However, I do think that, on a deeper level, Gerda's quest represents the stages of womanhood she will travel through in the world and perhaps that's why this fairytale speaks to me so strongly.

This is how I see Gerda's journey:

Spring – In the witch's cottage, Gerda is cared for and allowed to play in the garden but is forbidden to step outside the gate into the dangerous wood. The witch banishes all the roses that might remind her of Kai and does everything she can to keep the little girl from continuing her quest. Having a clingy mother myself, I can identify only too well with this stage. Even now, my mother seems unable to accept that I might want to open that gate and have adventures of my own in the big wide world.

Summer – At the Princess' palace, Gerda at first thinks Kai is the prince, and is disappointed when he turns out to be a stranger. In my DVD version a line of charming suitors try to win her hand, but Gerda rejects them all and escapes. This season represents the young and fertile woman chased by boys and making herself beautiful for them. It seems summer will last forever, with its dances and its roses and its declarations of love. But it is over all too soon.

Autumn – Here, I see the robber girl and her bandit mother representing the menopause, when a woman has finished with being a wife and mother and is beginning to find her own way in the world, coming into her power. It might be the autumn of her life, but autumn is a period of fruitfulness and harvest where the seeds sown in spring that blossomed in summer are ripening. Here, Gerda finds strength she didn't know she had and escapes by riding the robber girl's reindeer.

Winter – The Finn and Lapp women, living alone in their modest, cosy houses isolated in the snow, represent old age. They help Gerda, but warn her that if she chooses to continue her quest she must leave the reindeer and go on alone. This last part of her journey represents death, which everyone must face alone.

Finally, Gerda reaches the Snow Queen's palace, where she finds Kai trying to form a word out of shards of ice. The word is LOVE, but Kai's heart has been turned to ice by the Snow Queen's kiss, and the splinter of the devil's mirror in his eye means he cannot complete the puzzle. (In the DVD version, Kai's task is to reassemble the actual mirror). Of course he cannot do it, until Gerda kisses him and melts his heart. He weeps with joy at seeing her, and the splinter comes out of his eye. Like all fairytales, it is a happy ending. Kai completes his impossible task, winning his freedom from the Snow Queen, and the two young people return to their rose garden, where (one imagines) they got married and had a gloriously happy life bringing up their own children with the advantage of the lessons they have both learnt… I like to think so, anyway!

The splinter in Kai's eye is a powerful image. The devil – or hobgoblin or elf – made this mirror to reflect beautiful things as ugly and make ugly things seem normal. It's very true that the way you look at something can change completely the way you see life, and I've certainly gone through phases myself when a splinter of the devil's mirror gets lodged in my eye, and I have to make a conscious effort to squeeze it out before I can see the good around me.

Breaking a mirror is also very symbolic, bringing seven years of bad luck according to some. I broke a large mirror seven years ago… of course I'm not superstitious AT ALL, but it is rather spooky how, after almost seven years of being out in the cold as an author following the death of my agent, this year sees the publication of a brand new quest for my readers beginning with "Sword of Light". And happily, I've no need to worry about breaking another mirror, since my lovely editors at Templar sent me this silver unicorn horn as a publication day present, which as everyone knows is a powerful charm against bad luck…

Katherine Roberts grew up in the wild, rocky counties of Devon and Cornwall with their brooding moors and rugged coasts. She gained a first class degree in mathematics from Bath University, and went on to work as a mathematician, computer programmer, racehorse groom and farm labourer - before her first novel, 'Spellfall', won the Branford Boase Award in 1999 and enabled her to fulfil her dream of becoming a full time writer. Her many fantasy books for children and young adults include 'The Echorium Sequence' (beginning with Song Quest), 'The Seven Fabulous Wonders' series of historical fantasies (beginning with 'The Pyramid Robbery'), and 'I Am The Great Horse', the story of Alexander the Great told by his famous horse Bucephalus.

Katherine's latest book, 'Sword of Light', the first of four Arthurian fantasies for children, has just been published by Templar.

Katherine's latest book, 'Sword of Light', the first of four Arthurian fantasies for children, has just been published by Templar. Visit Katherine's website!

Picture credits: images from The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen, illustrated by Errol le Cain

Published on February 17, 2012 00:57

February 13, 2012

"Sword of Light" Interview with Katherine Roberts

King Arthur is dead, the Round Table broken. You'd think all hope was gone... but you'd be wrong, for the King has one last heir - a young girl! Hidden for her own protection in the enchanted mists of Avalon since she was a child, she now comes riding forth to save her father's kingdom from the wiles of the evil Mordred. Meet Princess Rhianna Pendragon, King Arthur's daughter!

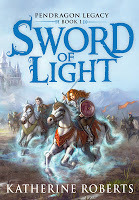

And here is the lovely cover of 'Sword of Light', the first of the 'Pendragon Legacy', a magical Arthurian fantasy for children by my friend Katherine Roberts.

This is just the sort of book I adored as a child. It has everything - sword fighting, magically beautiful mist-horses, elves, dragons, a couple of truly evil villains, more than a hint of Celtic folklore, and on top of all that a brave, frank, adventurous heroine with red hair and freckles. Think Anne of Green Gables in a suit of armour!

Katherine Roberts' writing is perfectly pitched for any romantic ten-year old who likes a tale of adventure with a strong dash of magic. It can also be slyly witty. I loved the episode where Rhianna meets the langorous Nimue, Lady of the Lake (who, disconcertingly, has gills):

"Rhianna Pendragon," the fish-lady repeated, and the name sang around the cavern, making the anemones flare brightly. "Hmm. A damsel with a warrior's name. No tail, I see," she observed as Rhianna squeezed the water from her hair.

"Of course I haven't got a tail! I'm human. And I need that sword so we can take it back to Avalon for my father, as soon as Merlin shows up again."

"Ah..." The lady's turquoise eyes went distant. "Dear old Merlin. Strange, I can't see him. How is he?"

So here is my interview with Katherine Roberts. I think it sheds interesting light on the writing process - the way themes or an idea can occur years before they are used, and work their way slowly to the forefront of a writer's mind, morphing and shapeshifting as go - and on the way a writer's 'world' slowly emerges, too.

Rhianna Pendragon, King Arthur's daughter! Such a simple but marvellous idea - how did it first occur to you?

I first came across the idea of King Arthur having a daughter in a collection of novellas by Vera Chapman ("The Three Damosels"), which I won in one of the infamous Fantasycon raffles organised by the British Fantasy Society. That was way back before I'd had any books published myself, but the concept of a Pendragon princess certainly caught my imagination. As Vera Chapman says in her introduction to the story: "Nobody can say that King Arthur did NOT have a daughter. King's daughters, unless they make dynastic marriages, are apt to slip out of history and be ignored."

The idea resurfaced when I wanted to write a series about a warrior princess for younger readers. I'd actually begun a book about Queen Boudicca's daughters, but found the rape scene to be a stumbling block for children's publishers. So I ditched that idea and combined my red-haired Celtic warrior princess with Vera's more courtly Princess Ursulet… and ended up with Rhianna Pendragon!

It's refreshing to read an Arthurian story in which a girl is active and heroic rather than a damsel in distress. But Rhianna Pendragon has been kept ignorant of her parentage, and is called into action at the darkest possible moment, after Arthur's death at the hands of Mordred. Why did you decide to begin Rhianna's adventures at this particular late stage of the story?

I wanted to start where the traditional Arthurian legends left off because I knew that would give me more freedom to work up some new stories for Rhianna. The TV series "Merlin" takes the Arthurian legend backwards, which can work too, but for me a story is usually more interesting when you don't know the ending.

Rather than the medieval period, you've set the novel in the much earlier Dark Ages at the time of the Saxon invasion of Britain, thought be the likeliest period for a historical Arthur. But the narrative also makes room for magic and ghosts, for Celtic myths and legends, for the Wild Hunt, dragons, and gallant knights. The blend of history and fantasy is seamless, but was it hard to balance these elements?

Rather than the medieval period, you've set the novel in the much earlier Dark Ages at the time of the Saxon invasion of Britain, thought be the likeliest period for a historical Arthur. But the narrative also makes room for magic and ghosts, for Celtic myths and legends, for the Wild Hunt, dragons, and gallant knights. The blend of history and fantasy is seamless, but was it hard to balance these elements?

It wasn't seamless in the first draft! I had to do a lot of invisible stitching... But yes, the Dark Ages appeal to me as a setting simply because they are historically dark and therefore leave me more freedom to work in fantasy elements. There's actually very little historical fact about Arthur, so I haven't been too strict on the historical details in my series – I'm aiming to give these books the feel of a fantasy age, occurring somewhere between our Dark Ages and the Middle Ages, but not entirely of our world. If you look closely at my maps, you'll see I've taken the same approach with the geography – familiar, but not too familiar!

Rhianna has good friends to assist in her quest: the faerie Prince Elphin of Avalon, a stocky squire named Cai, and of course her beloved little mare Alba, a silver-shod mist horse who can mind-speak with her mistress! I don't think I've ever met a mist-horse before, so are they even more special than unicorns?

In the first draft of the book, Rhianna's horse was just an ordinary white mare. Then I remembered the Irish myth of Oisin and Niamh, where the fairy horse carries Oisin across the sea to his lover in Fairyland, and decided to make Alba more magical. When shod with silver, mist horses can trot over the surface of water – a useful talent when Rhianna needs to escape her enemies. They also have the ability to "mist", which is a kind of vanishing/reappearing act and (as you can imagine) makes a mist horse tricky to ride. And, of course, all fairy horses can talk.

In your 'Fairytale Reflection' (coming on Friday!) you chose to write about 'The Snow Queen' and Andersen's steadfast heroine, Gerda, who sets out to rescue her brother. Do you think there is a connection between her and Rhianna – who sets out into the world on a quest to defeat another powerful queen, Morgan le Fay?

Now that you mention it, the two quests are very similar, aren't they? Rhianna's ultimate quest is to bring her father King Arthur back to Camelot from Avalon. Gerda's quest is to bring her brother Kai back from the Snow Queen's palace. Both involve going into an enchanted place and rescuing a loved one from the cold kiss of death.

I know Rhianna has many more adventures to come: and she hasn't even met her mother Queen Guinevere yet! Given her parentage, which do you think she takes after most - the noble and brave King her father, or the beautiful Queen?

In looks – freckles and red hair – Rhianna takes after her mother. But in courage and spirit, she's definitely more like her father. Though having grown up on the enchanted island of Avalon in the care of Lord Avallach with brief visits from Merlin, she is also her own person, and sees no problem with using magic to help her on her quest. She finds it hard to relate to the other damsels at Camelot, and poor Arianrhod (her maid) has a hard time trying to turn her into a princess!

SWORD OF LIGHT is published in hardcover by Templar (www.templarco.co.uk)

You can follow Rhianna Pendragon on Twitter at www.twitter.com/PendragonGirl

Katherine's website with details of all her books is at www.katherineroberts.co.uk - where you can also read the first chapter of 'Sword of Light

And here is the lovely cover of 'Sword of Light', the first of the 'Pendragon Legacy', a magical Arthurian fantasy for children by my friend Katherine Roberts.

This is just the sort of book I adored as a child. It has everything - sword fighting, magically beautiful mist-horses, elves, dragons, a couple of truly evil villains, more than a hint of Celtic folklore, and on top of all that a brave, frank, adventurous heroine with red hair and freckles. Think Anne of Green Gables in a suit of armour!

Katherine Roberts' writing is perfectly pitched for any romantic ten-year old who likes a tale of adventure with a strong dash of magic. It can also be slyly witty. I loved the episode where Rhianna meets the langorous Nimue, Lady of the Lake (who, disconcertingly, has gills):

"Rhianna Pendragon," the fish-lady repeated, and the name sang around the cavern, making the anemones flare brightly. "Hmm. A damsel with a warrior's name. No tail, I see," she observed as Rhianna squeezed the water from her hair.

"Of course I haven't got a tail! I'm human. And I need that sword so we can take it back to Avalon for my father, as soon as Merlin shows up again."

"Ah..." The lady's turquoise eyes went distant. "Dear old Merlin. Strange, I can't see him. How is he?"

So here is my interview with Katherine Roberts. I think it sheds interesting light on the writing process - the way themes or an idea can occur years before they are used, and work their way slowly to the forefront of a writer's mind, morphing and shapeshifting as go - and on the way a writer's 'world' slowly emerges, too.

Rhianna Pendragon, King Arthur's daughter! Such a simple but marvellous idea - how did it first occur to you?

I first came across the idea of King Arthur having a daughter in a collection of novellas by Vera Chapman ("The Three Damosels"), which I won in one of the infamous Fantasycon raffles organised by the British Fantasy Society. That was way back before I'd had any books published myself, but the concept of a Pendragon princess certainly caught my imagination. As Vera Chapman says in her introduction to the story: "Nobody can say that King Arthur did NOT have a daughter. King's daughters, unless they make dynastic marriages, are apt to slip out of history and be ignored."

The idea resurfaced when I wanted to write a series about a warrior princess for younger readers. I'd actually begun a book about Queen Boudicca's daughters, but found the rape scene to be a stumbling block for children's publishers. So I ditched that idea and combined my red-haired Celtic warrior princess with Vera's more courtly Princess Ursulet… and ended up with Rhianna Pendragon!

It's refreshing to read an Arthurian story in which a girl is active and heroic rather than a damsel in distress. But Rhianna Pendragon has been kept ignorant of her parentage, and is called into action at the darkest possible moment, after Arthur's death at the hands of Mordred. Why did you decide to begin Rhianna's adventures at this particular late stage of the story?

I wanted to start where the traditional Arthurian legends left off because I knew that would give me more freedom to work up some new stories for Rhianna. The TV series "Merlin" takes the Arthurian legend backwards, which can work too, but for me a story is usually more interesting when you don't know the ending.

Rather than the medieval period, you've set the novel in the much earlier Dark Ages at the time of the Saxon invasion of Britain, thought be the likeliest period for a historical Arthur. But the narrative also makes room for magic and ghosts, for Celtic myths and legends, for the Wild Hunt, dragons, and gallant knights. The blend of history and fantasy is seamless, but was it hard to balance these elements?

Rather than the medieval period, you've set the novel in the much earlier Dark Ages at the time of the Saxon invasion of Britain, thought be the likeliest period for a historical Arthur. But the narrative also makes room for magic and ghosts, for Celtic myths and legends, for the Wild Hunt, dragons, and gallant knights. The blend of history and fantasy is seamless, but was it hard to balance these elements? It wasn't seamless in the first draft! I had to do a lot of invisible stitching... But yes, the Dark Ages appeal to me as a setting simply because they are historically dark and therefore leave me more freedom to work in fantasy elements. There's actually very little historical fact about Arthur, so I haven't been too strict on the historical details in my series – I'm aiming to give these books the feel of a fantasy age, occurring somewhere between our Dark Ages and the Middle Ages, but not entirely of our world. If you look closely at my maps, you'll see I've taken the same approach with the geography – familiar, but not too familiar!

Rhianna has good friends to assist in her quest: the faerie Prince Elphin of Avalon, a stocky squire named Cai, and of course her beloved little mare Alba, a silver-shod mist horse who can mind-speak with her mistress! I don't think I've ever met a mist-horse before, so are they even more special than unicorns?