Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 37

April 20, 2012

The Pied Piper of Hamelin

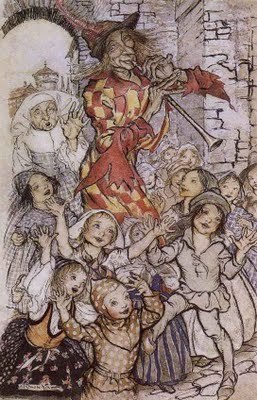

The Pied Piper by Arthur Rackham

The Pied Piper by Arthur Rackhamby Joanne Harris

Raised as I was on the darkest, grimmest of Grimm’s fairy tales, I’ve always been very much aware of the dual nature of the world depicted in folklore and story. For every happy ending, there is an equally tragic one; children left to die in the woods; lovers parted forever; villains with their eyes pecked out by crows, or burnt alive; or hanged. Fairytale is a world away from the comfortable assurances of the Disney franchise – and surely that was the purpose of those original fairy tales, devised as they were for an audience comprising mostly of adults; often very poor; people whose lives were cruel and harsh, and who would never – even in fiction - have accepted to believe in a world in which the shadows did not at least occasionally rival the light.

My favourite of these ambiguous tales was always the Pied Piper. It’s interesting that this very well-known story has never been softened and sweetened in the way in which, for instance, The Little Mermaid, or Sleeping Beauty, or Cinderella have been adapted to suit our more sensitive times and cultures. Perhaps because the main character is such a sinister figure, nameless, appearing from nowhere, then vanishing into nowhere again, leaving nothing but unanswered questions and a story that lingers uncomfortably without a happy ending. But the ambiguity and the unanswered questions are part of my fondness for this tale, which seems to me to sum up perfectly our uncomfortable relationship with the world of magic and story, a relationship that combines longing and fear in fairly equal proportions.

Like all stories carried down through the oral tradition, there are many versions of the Pied Piper. Mine goes like this.

Once, the town of Hamelin was overrun by a plague of rats. (One of this story’s most interesting characteristics is that it is set in a real place, thereby locating the action somewhere between the conscious and the unconscious mind.) The rats were huge, black rats, and they spread like wildfire through the town, invading store-rooms and cellars, getting fat on grain stores, finally growing so big and so bold that they would snatch food right off dining-room tables, or little children right out of their cribs. (At this point, I remember an illustration in one of my grandfather’s old books, which showed a nurse looking into a crib, frozen with horror at the sight of a big rat sitting there in place of the baby.) No-one in Hamelin knew what to do. The Mayor, faced with a crisis such as he had never seen, announced a reward of a thousand crowns to the man who could rid the town of the rats.

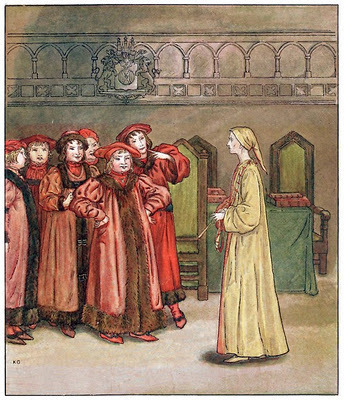

"A thousand guilders! The Mayor looked blue." Kate Greenaway

"A thousand guilders! The Mayor looked blue." Kate Greenaway The next day a stranger came into town. (It’s worth noting here how often the very best stories begin with the arrival of a stranger into a closed community.) He was a beggar, by the look of him, with red hair and a jacket of two colours. (This is what made him the Pied Piper, and I spent a long time as a child trying to determine exactly what this pied quality meant in visual terms. Some books depicted him in yellow and red, like a court jester. Some said he was in red and green, a combination sometimes associated with the fairy world. I imagined him as a magpie; white on one side and black on the other, with the added associations both of bad luck and theft.) The man had no horse, no money and no possessions but a set of reed-pipes, on which he played very beautifully. (I also spent a very long time thinking about those pipes of his. I’d first read the story in French, for which the name of the instrument was “flûte.” In English, however, the stranger is described as a “piper,” which to me implied either bagpipes – which seemed unlikely - or maybe some kind of recorder, also referred to as “flûte”, or “pipeau” in French. I finally decided that the stranger played the pan-pipes, an instrument that has long been associated with the primal, darker side of Nature. This may seem like a trivial point, but in these old stories so many things are lost in translation – look at Cinderella’s glass slipper – that it’s sometimes worth checking the details.)

The next day a stranger came into town. (It’s worth noting here how often the very best stories begin with the arrival of a stranger into a closed community.) He was a beggar, by the look of him, with red hair and a jacket of two colours. (This is what made him the Pied Piper, and I spent a long time as a child trying to determine exactly what this pied quality meant in visual terms. Some books depicted him in yellow and red, like a court jester. Some said he was in red and green, a combination sometimes associated with the fairy world. I imagined him as a magpie; white on one side and black on the other, with the added associations both of bad luck and theft.) The man had no horse, no money and no possessions but a set of reed-pipes, on which he played very beautifully. (I also spent a very long time thinking about those pipes of his. I’d first read the story in French, for which the name of the instrument was “flûte.” In English, however, the stranger is described as a “piper,” which to me implied either bagpipes – which seemed unlikely - or maybe some kind of recorder, also referred to as “flûte”, or “pipeau” in French. I finally decided that the stranger played the pan-pipes, an instrument that has long been associated with the primal, darker side of Nature. This may seem like a trivial point, but in these old stories so many things are lost in translation – look at Cinderella’s glass slipper – that it’s sometimes worth checking the details.)The Pied Piper had seen the rats and knew of the Mayor’s pronouncement. “I’ll rid you of your plague,” he said. “But remember, you promised to pay me.”

The Mayor, who, like all politicians, was more concerned with making promises than with keeping them, and besides, had little confidence in a man who couldn’t even decide on a single colour for his coat, agreed, rather too eagerly.

And so the Pied Piper took out his pipes and began to play a very simple little tune.

The Pied Piper by Elisabeth AlbaNo-one could quite remember the notes of the tune the piper played (this should have come as a warning,) but it was a warm and lilting tune, bright and wistful at the same time; the kind of tune that makes people smile almost without knowing it, the kind of tune that makes folk tap their feet and think about dancing. And as the Piper played, the rats came out of the cellars to listen to him; and they slunk out of the back alleys and the grain-stores and sewers and ditches, and went off in the wake of the Piper, who ignored them and just went on playing that very simple little song, making his way quite casually into the centre of Hamelin, where the river ran fast and deep. And when he got to the river, the Pied Piper stood on the quay and played a little faster, and all the rats that had followed him ran straight into the river and drowned; and that was the end of the plague of rats.

The Pied Piper by Elisabeth AlbaNo-one could quite remember the notes of the tune the piper played (this should have come as a warning,) but it was a warm and lilting tune, bright and wistful at the same time; the kind of tune that makes people smile almost without knowing it, the kind of tune that makes folk tap their feet and think about dancing. And as the Piper played, the rats came out of the cellars to listen to him; and they slunk out of the back alleys and the grain-stores and sewers and ditches, and went off in the wake of the Piper, who ignored them and just went on playing that very simple little song, making his way quite casually into the centre of Hamelin, where the river ran fast and deep. And when he got to the river, the Pied Piper stood on the quay and played a little faster, and all the rats that had followed him ran straight into the river and drowned; and that was the end of the plague of rats.

The next day the Piper went to the Mayor to collect his thousand crowns. (One of the beauties of this tale is its continuing relevance. Centuries down the line, and artists – musicians and writers - are still fighting to be paid for the work they do, while people like the greedy Mayor still believe they can get it for free.) But the Mayor just laughed at the Piper, and said; “A thousand crowns for a tune? You must be out of your tiny mind. I’ll pay you a shilling for your trouble, and I’ll not ask to see your performer’s license.”

The Pied Piper wasn’t amused. (I’ve always seen him as red-haired, and red-haired men have a temper.) His mouth grew tight, and his strange green eyes narrowed, and he turned to the people of Hamelin and said; “You all heard what he promised me. You can make him keep his word.”

But the people of Hamelin knew perfectly well that the thousand crowns, if they were paid, would come straight out of their taxes. And now that they were free of the rats, it rankled to pay such a large sum to a man who had done nothing more than blow into a handful of reeds.

The man was a vagrant, after all; probably an illegal too. Why should their hard-earned taxes go to an undesirable? And so they said nothing, and shuffled their feet, and the Pied Piper got angry.

Pied fiddler? German: artist unknownAt which point the Mayor, who had been waiting for the chance to pin something on the vagrant, had the Piper thrown out of town, with orders never to return. But as he reached the town gates, the stranger took out his reed pipe and once again began to play. No-one paid much attention at first. After all, the rats were gone. But the children of Hamelin heard the tune – a music that was at the same time wild and a little wistful, merry and unutterably sad – and they came out to hear the Piper. Heedless of parents and teachers alike, children all over Hamelin left their games and their schoolwork, abandoned their bicycles in the street, left football matches and skipping-ropes and went dancing off in the Piper’s wake. (I like to think that the tune he played was something only children could hear; a sound beyond the normal frequencies of the adult register. Perhaps it was; or perhaps children are just more susceptible to the call of the subconscious mind.)

Pied fiddler? German: artist unknownAt which point the Mayor, who had been waiting for the chance to pin something on the vagrant, had the Piper thrown out of town, with orders never to return. But as he reached the town gates, the stranger took out his reed pipe and once again began to play. No-one paid much attention at first. After all, the rats were gone. But the children of Hamelin heard the tune – a music that was at the same time wild and a little wistful, merry and unutterably sad – and they came out to hear the Piper. Heedless of parents and teachers alike, children all over Hamelin left their games and their schoolwork, abandoned their bicycles in the street, left football matches and skipping-ropes and went dancing off in the Piper’s wake. (I like to think that the tune he played was something only children could hear; a sound beyond the normal frequencies of the adult register. Perhaps it was; or perhaps children are just more susceptible to the call of the subconscious mind.)They followed the Piper out of the town until they came to a round hill; and as they approached, a secret door inside the hill swung open, revealing a dark passage beneath. (I was born in a coal-mining town and in the waste ground behind my house there were several abandoned mineshafts. As a child I was at the same time terrified and fascinated by these, and spent hours crawling around the entrances to various tunnels and openings, certain that sooner or later I was going to get into Fairyland. Like the little lame boy, I’ve been looking ever since.)

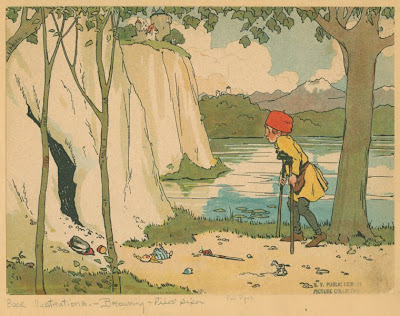

The Pied Piper by Elisabeth Forbes 1859-1912One by one, the children followed the Piper into the hill –and then the door to the passage slammed shut and none of the children were ever seen again. Only one child was left behind – a lame boy, unable to keep the pace, who was still outside when the hill closed.

The Pied Piper by Elisabeth Forbes 1859-1912One by one, the children followed the Piper into the hill –and then the door to the passage slammed shut and none of the children were ever seen again. Only one child was left behind – a lame boy, unable to keep the pace, who was still outside when the hill closed.As for the Pied Piper, whoever he was, no-one ever saw him again either, although some people thought they heard music coming from under the hill – music, and children’s voices, though whether the children were laughing or screaming, no-one could ever be certain.

As for the Piper, whoever he was… Perhaps this is the real reason why Disney has no use for this tale. There is no comfortable conclusion to this story; no happy-ever-after, not even a clear explanation. What happened to the children? Did they die inside the hill? Did the Piper abandon them there? Or were they (as I liked to believe) taken to another world, where children never have to grow up, forever free of the hypocrisy, greed and meanness of adult life? And who is the Pied Piper? The King of Faërie? An agent of Death? A parent’s worst nightmare? A child’s fondest dream? What happened to the lame boy? Did he spend the rest of his life trying to find the secret door, or did he have a lucky escape? I’ve always thought that a good story should ask at least as many questions as it answers, and this one seems to me to be a perfect example of the genre.

The lame child left behind. Artist unknown. (Note the discarded toys.)Yes, and it is a fairy tale. In recent decades it seems to have become fashionable to look down upon the fairy tale and to value instead the kind of reading matter that deals with “serious issues”. In short, we have learnt to look for answers, rather than questions in the stories that we read. Surely this is the opposite of what a story should do for us. One of the reasons fairy tales and legends still resonate so strongly with us is that in spite of their apparent irrelevance to the topical problems of the “real” world (one of my grandfather’s sternest criticisms was to refer to something as “airy-fairy”, which implied both lacking in substance as well as dangerously imaginative), they nevertheless manage to locate our most sensitive pressure points, those things that transcend mere topicality, heading straight for the collective unconscious. (If you need further proof of this, try naming ten classic fairy tales from memory. Then try naming ten Booker prize-winners. See which ones you remember best.)

The lame child left behind. Artist unknown. (Note the discarded toys.)Yes, and it is a fairy tale. In recent decades it seems to have become fashionable to look down upon the fairy tale and to value instead the kind of reading matter that deals with “serious issues”. In short, we have learnt to look for answers, rather than questions in the stories that we read. Surely this is the opposite of what a story should do for us. One of the reasons fairy tales and legends still resonate so strongly with us is that in spite of their apparent irrelevance to the topical problems of the “real” world (one of my grandfather’s sternest criticisms was to refer to something as “airy-fairy”, which implied both lacking in substance as well as dangerously imaginative), they nevertheless manage to locate our most sensitive pressure points, those things that transcend mere topicality, heading straight for the collective unconscious. (If you need further proof of this, try naming ten classic fairy tales from memory. Then try naming ten Booker prize-winners. See which ones you remember best.)Lastly, for me, the Pied Piper is the perfect metaphor for our relationship with stories and storytellers. We all enjoy stories, but we also mistrust the subconscious world from which they spring, and we are often ambivalent, dismissive, fearful or sometimes downright ungrateful towards the people who create them. The Piper, like all artists, exists outside of society; his morality (such as it is) is fundamentally different from ours; he can be helpful or malevolent according to whim and his personal code; and his world, though appealing in many ways, is fraught with danger and mystery. As children, we often identify with the child characters in our stories. As an adult (and as a writer, of course) I have come to identify increasingly with the Pied Piper. Poised uncomfortably between the real world and the world of magic, keeping his audience in thrall; making them believe in things that they know to be impossible; facing both love and hostility with nothing more than a handful of tunes (or a story) between himself and the darkness - isn’t that what we all do? In a world that claims no longer to believe in magic or fairies or monsters, magic is still a powerful force, existing beneath the surface of things, ready to emerge when summoned by just the right combination of musical notes or of words on a page –

A story can bring down a government; or steal away a child’s heart; or build a religion; or just make us see the world differently. Storytellers come and go, but stories never die. And if that isn’t magic, then I don’t know what is.

Joanne Harris, author of 'Chocolat', needs little introduction. Her adult books are full of fairytale motifs, and she's a writer who is definitely comfortable with the superstitious and supernatural side of human life. Born to a French mother and an English father in her grandparents' sweet shop, her family life was filled with food and folklore, and there's a clear connection between food and magical power in her novels. Bottles of homebrewed wine in 'Blackberry Wine' actually narrate parts of the story, and the chocolate in 'Chocolat' is almost sacramental food. Joanne's characters see ghosts, consult the tarot, dance with shadows. I love the passage in Chocolat where Vianne makes a Pied Piper window display in the chocolaterie: a mountain of green tins covered in crinkly cellophane to represent ice, with a river of blue silk and a cluster of houseboats,

"And below a procession of chocolate figures: cats, dogs, rabbits… and mice. On every available surface, mice. Running up the sides of the hill, nestling in corners, even on the riverboats. Pink and white sugar coconut mice, chocolate mice of all colours, variegated mice marbled through with truffle and maraschino cream, delicately tinted mice, sugar-dappled frosted mice. And standing above them, the Pied Piper resplendent in his red and yellow, a barley-sugar flute in one hand, his hat in the other."

Her children's books, 'Runemarks' and its sequel 'Runelight', are wonderfully exciting blends of Norse myth and fantasy.

Published on April 20, 2012 00:07

April 17, 2012

Folklore Snippets - The Night Troll

The Night Troll

In this short tale, reminiscent of the Scottish ballad ‘The False Knight on the Road’, a quick-witted girl keeps a monster at bay. It was collected by the 19th century Icelandic folklorist Jón Árnason; trans May and Hallberg Hallmundsen, ‘Icelandic Folk and Fairy Tales’, Iceland Review Library, 1987 – and goes to show once again that girls and women in fairytales and folktales are resourceful and brave.

It happened at a certain farm that the person who was left to guard the house on Christmas Eve while the others were at evensong, were always found either dead or mad the following morning.

The farm people were greatly distressed over this, and there were few who wanted to stay home on that particular night. One Christmas, howeve, a young girl volunteered, and that was a relief to other members of the household.

After they left, the girl sat on a dais in the badstofa [heated sauna room], singing to the baby she held in her arms. As the night wore on she heard someone at the window saying:

“What a pretty hand you have,

my quick one, my keen one, and diddly-doe.”

The girl answered:

“It has never raked the muck,

my prowler, my Kári, and corry-roe.”

The one at the window said:

“What a pretty eye you have,

my quick one, my keen one, and diddly-doe.”

And the girl shot back:

“Never has it evil seen,

my prowler, my Kári, and corry-roe.”

The answer came from the window:

“What a pretty foot you have,

my quick one, my keen one, and diddly-doe.”

To which the girl replied,

“It has never trod in filth,

my prowler, my Kári, and corry-roe.”

From the voice at the window came:

“Day is dawning in the east,

my quick one, my keen one, and diddly-doe.”

And the girl within replied,

“Stay and turn to stone,

but be of harm to no one,

my prowler, my Kári, and corry-roe.”

Then the being disappeared from the window. In the morning when the farm people returned, a huge boulder was found in the alley between the farm buildings, and it has remained there ever since.

The girl recounted everything that had happened during the night. It appeared that it had been a night-troll that spoke to her through the window.

Picture credit: The Night Troll At the Window by Asgrimur Jonsson, 1876-1958

Published on April 17, 2012 00:48

April 16, 2012

The Golden Ages

I hope you'll forgive a little blatant self-promotion, but I'm going around this morning with a grin like a Cheshire Cat, after a couple of good friends got in touch to say my first book, Troll Fell, was given a really good shout-out on BBC Radio 4's book program, Open Book, yesterday! Novelist and critic Amanda Craig was in conversation with Lyn Gardner and Mariella Frostrup; and the second half of the program was about 'the golden ages' of children's books, and whether or not the classic children's book, accessible to what in the US are called middle-graders and over here, more long-windedly, 'seven to eleven year olds', is currently overshadowed by teen fiction.

I hope you'll forgive a little blatant self-promotion, but I'm going around this morning with a grin like a Cheshire Cat, after a couple of good friends got in touch to say my first book, Troll Fell, was given a really good shout-out on BBC Radio 4's book program, Open Book, yesterday! Novelist and critic Amanda Craig was in conversation with Lyn Gardner and Mariella Frostrup; and the second half of the program was about 'the golden ages' of children's books, and whether or not the classic children's book, accessible to what in the US are called middle-graders and over here, more long-windedly, 'seven to eleven year olds', is currently overshadowed by teen fiction.It's an interesting discussion with people who know their stuff - and I was thrilled to hear Amanda recommend 'Troll Fell' and its sequels (now in one volume as 'West of the Moon') as one of the best reads for the age group. Yay!

I think children aged seven to eleven or twelve or so ARE at a golden age - I love doing talks to them, they are so enthusiastic and receptive and just generally fun - and I agree with Amanda and Lyn that there has been more than one Golden Age of books written for them. But listen for yourselves!

Click here to go to the programme. The whole thing is worth listening to, but it's the last ten minutes which concern childrens' book, so it you want to concentrate on that, you can slide the cursor along.

Meanwhile I can't wipe that smile off my face.

Published on April 16, 2012 01:38

April 13, 2012

Rumpelstiltskin and the power of names

by Inbali Iserles

In the tale of Rumpelstiltskin, a mill owner boasts to the king of his daughter’s talent for spinning straw into gold. Presumably he utters this fib in a moment of reckless abandon, consumed with ambition and the desire to please. Why the king believes him is another question. Avarice and hubris rub shoulders thickly. So the mill owner’s daughter – beautiful, naturally, but quite lacking such talents, is set to work amid bales of straw. She must spin it into gold by morning, or perish at the king’s command. Men do not emerge well from this tale.

Yet the despairing maiden is visited by an odd little fellow. A dwarfish caliban without much to endear him, he nevertheless possesses the skill she lacks and he agrees to spin the straw into gold in exchange for her necklace. By morning, the man has gone, the room is full of gold, and the maiden is overjoyed. But the king is not satisfied: he wants more.

So the maiden is placed in a room, this time larger and with many more bales. Again she must spin them into gold, on pain of death. The little man returns to save the day, but creepily so – this is no prince on horseback, not the sort of character with whom you wish to do deals. But a deal must be struck, and the maiden offers him her ring. When the man has gone, and the room is full of gold, the king is overjoyed. But still he wants more.

Once last time the maiden is placed in a room, this time vast, with towering bales. As she wallows there, alone in her despair, the little man returns. This time she has nothing to offer him. He asks for her firstborn and the maiden agrees – thoughts of children are far from her mind. All turns out well, then, for a while. The delighted king offers his hand in marriage (the girl is of low birth but she is attractive, and she has made him rich beyond imagining). It is only later, long after the wedding festivities have concluded, that the young queen gives birth to her first child. And the little man returns to claim what is his.

Desperately the queen offers him the fortune of the kingdom, but the man will not be appeased – he longs for something living, not for the trappings of human wealth. Stirred with pity at the queen’s tears, he agrees that the she may keep the child provided that she can guess his name within three days.

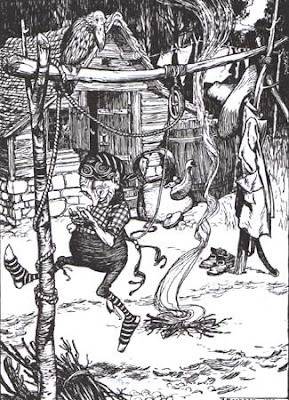

The queen tries every name she knows but all to no avail. She despatches messengers across the kingdom to hunt down unusual variations. Only on the third day, moments before the little man is due to appear, a messenger returns with a peculiar tale: on the very outskirts of the kingdom, he saw someone dancing a jig around a bonfire and singing of his unusual name: Rumpelstiltskin. The jubilant queen repels the little man by uttering his name. The man stamps his foot in fury, so hard that it sinks deep within the earth. Stamping his other foot, he rips himself apart. And that is the end of Rumpelstiltskin.

Here is a story where the greedy succeed, the victim is unsympathetic (was it wise of the maiden to promise her first born?) and the villain curiously wretched. What is the message of Rumpelstiltskin if not that cheaters are winners? After all, the little man had fulfilled his side of the bargain. Couldn’t it be that he was merely seeking that human affection that was denied him in his solitary life? He is odious, of course, but tragic too. I know that my interpretation of the story is a controversial one. I was always inclined to identify with the bad guy.

Here is a story where the greedy succeed, the victim is unsympathetic (was it wise of the maiden to promise her first born?) and the villain curiously wretched. What is the message of Rumpelstiltskin if not that cheaters are winners? After all, the little man had fulfilled his side of the bargain. Couldn’t it be that he was merely seeking that human affection that was denied him in his solitary life? He is odious, of course, but tragic too. I know that my interpretation of the story is a controversial one. I was always inclined to identify with the bad guy.What struck me most on first hearing this fairytale as a child was the power of a name. Rumpelstiltskin’s name was ultimately his undoing. As the bearer of an unusual name: my bête noir, my curse, my identity – I could empathise.

In most cultures names have symbolic meaning. They are not just labels by which we distinguish ourselves but avatars that hold a deep message, whether about our origins (Moses, in Hebrew “Moshe”, meaning “plucked out of water”), our intention for the name-bearer (Linda – “beautiful” in Spanish, Aslan – “lion” in Turkish) or a homage we pay to a deity or a saint for protecting the name-bearer.

Modern fantasy reveals a fascination with names. In The Lord of the Rings, there are names in many tongues, and ancient words hold in them the power of revelation. Most characters have multiple monikers. The shift in a hobbit-like creature to a wasted, tormented obsessive is characterised through a change of name from Smeagle to Gollum. The handsome hero of the epic is known, among other things, as Aragorn, son of Arathorn, the Dúnadan, Longshanks, Wingfoot and Strider.

Names may be dangerous and, in the world of books, their expression alone can be folly. Characters in the early Harry Potters are urged not to speak the name Voldemort, due to its perceived power, and in the later books dare not do so because of a trace placed on its utterance (Harry’s foolishness in breaking the taboo almost costs him and his friends their lives). In a world of spells, where language is gateway to untold power, a presence can be called upon by a name alone.

Invocation of this kind does not appear in Rumpelstiltskin, but another theme familiar to fantasy does. If someone knows your name – your true name – they can defeat or even rule over you. Take, for instance, the Earthsea series by Ursula K Le Guin. As the Master Namer explains: “A mage can control only what is near him, what he can name exactly and wholly.” A name, then, is the very essence of a thing. It is not simply a useful appellation by which is it known – it is the actual knowledge. Symbolically, Rumplestiskin’s name is his sacred identity. Revealing it cleaves him to his very core, taking his identity away from him.

It is probably imprudent to stray into the realm of souls, a thing’s essence, or whatever we may call it, and yet I suspect that the longing to communicate this is at the heart of creativity: the desire to be understood. If the wicked would seek to enslave us by possession of our true names, could that knowledge, shared with those we love, dismantle the barriers between human minds? Where could such insights take us, should we seek to do good? How else might poor Rumpelstiltskin have responded, had his name been invoked with love?

Inbali Iserles was born in Israel, but came to London with her family at the age of three when her father took up a post at London University. When she was eleven the family spent a year in Tucson, Arizona – she claims to have arrived a tomboy and departed well-groomed and tidy! – before returning to England, where she eventually studied at the Universities of Sussex and Cambridge before becoming a lawyer. She lives in Islington, London, with four degus - exotic rodents rescued from the RSPCA. Inbali has been an animal-lover all her life. And from childhood she has loved to write. Aged eight, she wrote a poem called ‘Rich Cat/Poor Cat’, which won a prize (I’m not allowed to reproduce it here!) – but it would take years of secret scribbling before she revisited feline themes in her first book, ‘The Tygrine Cat’ and its sequel, 'The Tygrine Cat on the Run'.

In her spare time she's a committed globetrotter, a passion that has taken her to the depths of the Amazon Rainforest and the bubbling geysers of Iceland. In addition to her two books about the Tygrine Cat, she has written another children’s book called ‘The Bloodstone Bird’.

Picture credits: Rumpelstiltskin, Walter Crane

Rumpelstilskin, artist unknown

Rumpelstiltskin, Arthur Rackham

Published on April 13, 2012 00:30

April 10, 2012

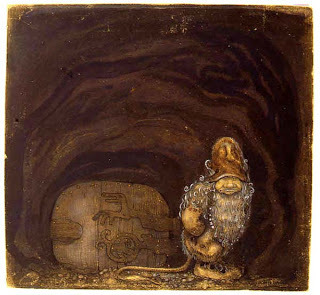

Folklore Snippets - "To Catch a Nisse"

From: "Scandinavian Folklore" ed: William Craigie 1896

As every one was eager to have a nisse attached to his farm, the following plan was formerly made use of to catch one. The people went out into the wood to fell a tree. At the sound of its fall the nisses all came running as hard as they could to see how folk did with it, so they sat down beside them and talked with them about one thing and another. When the wedges were driven into the tree, it would often happen that a nisse's little tail would fall into the cleft, and when the edge was driven out, the tail was fast and nisse was a prisoner.

Down in Bögeskov (Beech Wood) lived two poor people who, as they lay awake one night, talked of how fine it would be if a nisse would come and help them. No sooner had they said this than they heard a noise in the loft, as if someone were grinding corn. "Hallo!" said the man,"there we have him already!" "Lord Jesus, man, what's that you say?" said the woman; but as soon as she named the Lord's name, they heard nisse go crash out of the loft, taking the gable along with him.

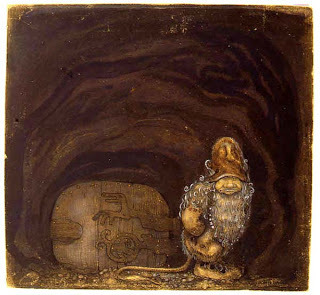

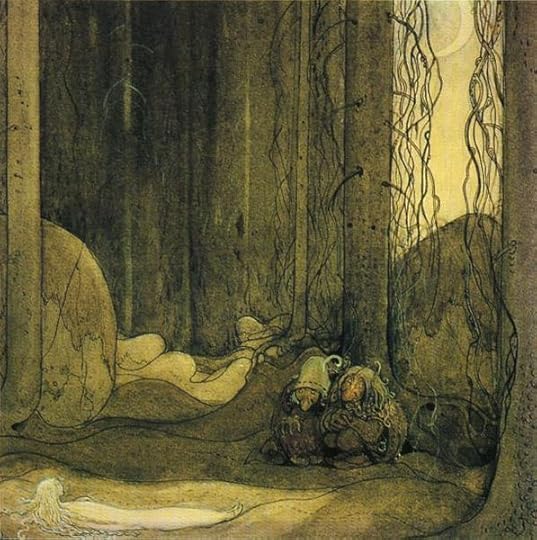

Picture credit: small troll or nisse by John Bauer (d. 1918)

As every one was eager to have a nisse attached to his farm, the following plan was formerly made use of to catch one. The people went out into the wood to fell a tree. At the sound of its fall the nisses all came running as hard as they could to see how folk did with it, so they sat down beside them and talked with them about one thing and another. When the wedges were driven into the tree, it would often happen that a nisse's little tail would fall into the cleft, and when the edge was driven out, the tail was fast and nisse was a prisoner.

Down in Bögeskov (Beech Wood) lived two poor people who, as they lay awake one night, talked of how fine it would be if a nisse would come and help them. No sooner had they said this than they heard a noise in the loft, as if someone were grinding corn. "Hallo!" said the man,"there we have him already!" "Lord Jesus, man, what's that you say?" said the woman; but as soon as she named the Lord's name, they heard nisse go crash out of the loft, taking the gable along with him.

Picture credit: small troll or nisse by John Bauer (d. 1918)

Published on April 10, 2012 02:41

April 6, 2012

The Wild Swans

by Sue Purkiss

I have been a reader of fairy tales at various stages in my life. When my sister and I were small, my mother used to buy us Ladybird books – Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood – always with the same reassuringly familiar format: a page of text on the left, and a full colour, full page illustration on the right. They taught me to read: we read the same books over and over, and one of my earliest memories is of insisting to Dad that tonight, I would read to him. I'd heard the stories so often that I'd memorised them, and begun to link up the printed words with the spoken ones.

Later on, when I really could read, I had a series of little buttercup yellow books, which each featured a single fairy story. I really liked these. I think it was partly because they were miniature: I also liked little teddy bears, dolls' house furniture, and tiny porcelain animals. I remember reading Beauty and the Beast under the sheets when I was supposed to be asleep. It had lovely pictures. There was one bit where the father brought back a red rose and a white rose from the Beast's castle. His daughters were astonished to see roses in the middle of winter; such a thing was impossible, and therefore proof of something magical. The roses in my garden often flower late, into November and even December, and when they do, I always feel vaguely surprised – because I know from that story that they shouldn't.

Later, when I was older, I used to get as many books as I could out of the libraries in town and at school. I read anything I could get hold of, including fairy stories: collections from different countries and Andrew Lang's series of rainbow fairy books. Then I read a book called The Amazing Mr Whisper, by Brenda Macrow. That was the first story I'd come across where the magical world intruded into the real one: the precursor for me of the Narnia books, Alan Garner, and eventually Tolkien. I was enchanted by the idea that the two worlds could collide, and I think after that I began to drift away from pure fairytales.

I rediscovered them when I had children of my own. My mother bought more Ladybird books: I bought collections with gorgeous illustrations. The children loved them, as I had done. I remember a friend saying she wouldn't buy fairy stories for her children: they are full of such terrible things, she said – old ladies pushed into ovens, grannies eaten by wolves, stepmothers poisoning princesses, parents abandoning their children. Well, yes… and yet, these stories endure, as others don't. (I managed to track down a copy of my beloved Mr Whisper a while ago; it hasn't worn well, even for me!) Children cope with the cruelty in fairy stories, just as they love the horrors that Roald Dahl's characters encounter; I think sometimes they are not given enough credit for being able to tell a fictional world from the real one, the one they have to live in.

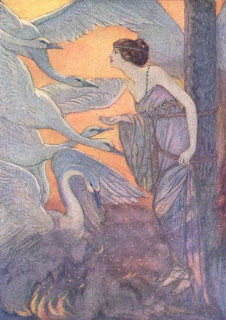

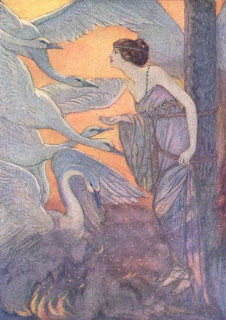

Decoupage of the Wild Swans by Queen Margrethe of Denmark

Decoupage of the Wild Swans by Queen Margrethe of Denmark

The Wild Swans, by Hans Christian Andersen, has terrible things in it. But it's also a story of haunting beauty. This is what happens.

It begins with eleven princes, who write 'with diamond pencils on golden tablets' and their little sister, Elisa, who has 'a picture book that cost half the kingdom'. Their mother is dead, but nevertheless they are happy until their father marries an evil queen, who turns the brothers into swans (they change back to their true forms only at night) and sends Elisa to live with peasants in the country. When she is fifteen, Elisa returns to the court, but the stepmother manages to get rid of her (not without some difficulty, but she's a resourceful woman). Elisa flees the castle, and find herself in a dark, dark forest. Thanks to a troop of glow worms, another of angels, and a mysterious old woman, Elisa finds her way through the woods to the sea, where she meets up with her brothers. They carry her over the ocean to the country where they live, a place of forests, mountains and castles. As she sleeps, a fairy comes to Elisa in a dream and tells her she can lift the enchantment from her brothers, provided she makes each of them a shirt out of nettles. But she must not speak a word till she has done: if she does, her brothers will die.

She begins the work, but she has only finished one shirt when the king of the country comes across her while he is hunting. He falls in love with her, takes her back to his castle, gives her 'regal gowns' and has her hair 'braided with pearls'. They marry, and she falls in love with him too, but is determined to press on with her task. The archbishop, however, believes she is a witch. He follows her one night when, having run out of nettles, she goes to a churchyard to collect more, passing by monsters which feast on the flesh of corpses to do so. The archbishop accuses her of witchcraft, the king can find no other explanation for her trips to the graveyard, and of course she cannot speak: he declares that the people must decide on her fate. They do – they say she's a witch and must burn. Still she keeps sewing, still she won't speak. Just in the nick of time, her brothers appear. She throws the shirts over them, and they are transformed into their real selves. (All except the youngest. His shirt is not quite finished, so he is left with a swan's wing instead of an arm.) Elisa, exhausted, collapses, seemingly lifeless. But then something magical happens: the faggots which had been used to make the pyre suddenly begin to grow, and in no time at all a hedge of beautiful red roses has appeared. At the very top is a single white one. The king plucks it, lays it close to Elisa's heart, and she comes back to life.

So – terrible things indeed. Some of the elements of this story are to be found in others too. There is the evil stepmother. She has the king: she doesn't want to be burdened with his twelve children. So they experience the sudden loss of an idyllic lifestyle; they sink from the top of the heap to the very bottom. There is the journey – the quest – through a forest. Forests, of course, were dangerous. They still are in many places (though not, perhaps, in our small island). In a real forest, you can quickly become disorientated and lose your way, and then you are at the mercy of fierce creatures: wild boar, wolves, and bears. In an enchanted one, there are other dangers too – witches, goblins, sinister trees.

Elisa is beset by dangers from the start. But once she sets about her task, she becomes even more vulnerable; she is not allowed to speak, so she cannot explain or defend herself. The king is kind and he loves her, but even he is a threat to her: he takes her away, without her permission, from where she needs to be. She has to go to the graveyard – it's the only place she can get fresh supplies of nettles – but in doing so, she lays herself open to the Archbishop's accusations. Then she falls victim to a mob: one day the people cheer her: the next they jeer and condemn her to a terrible death. The fickle affections of the mob are frighteningly real.

But she is not a passive victim. We know that she is only allowing all this to happen to her because she is ferociously loyal and determined. Even when she falls in love with the king, she still doesn't allow herself to be distracted. She loves her brothers and she is determined to keep to her commitment to save them, no matter how hard it may be. She may be a victim, but she's far from weak.

We talk of 'fairy-tale endings' as if fairy stories invariably end well. True, in the end Cinderella and her prince live happily ever after. So does the Sleeping Beauty; so does Snow White. But it isn't always so. In The Wild Swans, one brother is left with a swan's wing instead of an arm. Perhaps this is one of the things that makes this particular story so poignant; there's an admission that everything doesn't always turn out all right, no matter how hard you try. Fairy stories may take place in an enchanted land, but they deal with situations we must face in real life.

There is even something paradoxical about the enchantment. The stepmother wants to turn the princes into 'voiceless birds', but her power has its limits, and instead of becoming something ugly, they are turned into 'beautiful wild swans'. They are no longer princes, and their true lives have been taken away, but still they have been transformed into something wonderful: to borrow from Yeats, 'a terrible beauty is born': and they fly across the ocean at sunset to meet their sister like 'a white ribbon being pulled across the sky'. It's a lovely image and a lovely moment, as Elisa sees her brothers for the first time in so many long and difficult years.

The Wild Swans is about as far as you can get from the popular Disneyfied construct of what a fairytale is. Like a wild landscape, it is bleak and harsh. But, for me at any rate, it has also a beauty that touches the heart.

Sue Purkiss describes her first few stories as 'ghostie, witch fantasies for young children'. Her next two novels, 'The Willow Man' and 'Warrior King' are for older children. 'The Willow Man' is a contemporary story underpinned by the presence of the mysterious and magical figure of the 'Willow Man' or 'Withy Man', a huge outdoor sculpture by Serena de la Hey, set in a field near Bridgewater in Somerset. And 'Warrior King' is a re-imagining of part of the life of Alfred the Great – king of Wessex from 871 to 899, renowned for his learning, for his defence of England against the Danes, and in a legend once famous among schoolchildren, for burning those cakes.

Sue's books are grounded in the landscape of Britain, especially the beautiful county of Somerset where she now lives, which contains the original Isle of Avalon, the mysterious Glastonbury Tor, and the misty marshes where Alfred once hid from the Danes. Her most recent book, 'Emily's Surprising Voyage' is a story of Brunel's spectacular ship the SS Great Britain, now permanently in Bristol harbour. And she is currently working on a book set in World War II.

I have been a reader of fairy tales at various stages in my life. When my sister and I were small, my mother used to buy us Ladybird books – Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood – always with the same reassuringly familiar format: a page of text on the left, and a full colour, full page illustration on the right. They taught me to read: we read the same books over and over, and one of my earliest memories is of insisting to Dad that tonight, I would read to him. I'd heard the stories so often that I'd memorised them, and begun to link up the printed words with the spoken ones.

Later on, when I really could read, I had a series of little buttercup yellow books, which each featured a single fairy story. I really liked these. I think it was partly because they were miniature: I also liked little teddy bears, dolls' house furniture, and tiny porcelain animals. I remember reading Beauty and the Beast under the sheets when I was supposed to be asleep. It had lovely pictures. There was one bit where the father brought back a red rose and a white rose from the Beast's castle. His daughters were astonished to see roses in the middle of winter; such a thing was impossible, and therefore proof of something magical. The roses in my garden often flower late, into November and even December, and when they do, I always feel vaguely surprised – because I know from that story that they shouldn't.

Later, when I was older, I used to get as many books as I could out of the libraries in town and at school. I read anything I could get hold of, including fairy stories: collections from different countries and Andrew Lang's series of rainbow fairy books. Then I read a book called The Amazing Mr Whisper, by Brenda Macrow. That was the first story I'd come across where the magical world intruded into the real one: the precursor for me of the Narnia books, Alan Garner, and eventually Tolkien. I was enchanted by the idea that the two worlds could collide, and I think after that I began to drift away from pure fairytales.

I rediscovered them when I had children of my own. My mother bought more Ladybird books: I bought collections with gorgeous illustrations. The children loved them, as I had done. I remember a friend saying she wouldn't buy fairy stories for her children: they are full of such terrible things, she said – old ladies pushed into ovens, grannies eaten by wolves, stepmothers poisoning princesses, parents abandoning their children. Well, yes… and yet, these stories endure, as others don't. (I managed to track down a copy of my beloved Mr Whisper a while ago; it hasn't worn well, even for me!) Children cope with the cruelty in fairy stories, just as they love the horrors that Roald Dahl's characters encounter; I think sometimes they are not given enough credit for being able to tell a fictional world from the real one, the one they have to live in.

Decoupage of the Wild Swans by Queen Margrethe of Denmark

Decoupage of the Wild Swans by Queen Margrethe of DenmarkThe Wild Swans, by Hans Christian Andersen, has terrible things in it. But it's also a story of haunting beauty. This is what happens.

It begins with eleven princes, who write 'with diamond pencils on golden tablets' and their little sister, Elisa, who has 'a picture book that cost half the kingdom'. Their mother is dead, but nevertheless they are happy until their father marries an evil queen, who turns the brothers into swans (they change back to their true forms only at night) and sends Elisa to live with peasants in the country. When she is fifteen, Elisa returns to the court, but the stepmother manages to get rid of her (not without some difficulty, but she's a resourceful woman). Elisa flees the castle, and find herself in a dark, dark forest. Thanks to a troop of glow worms, another of angels, and a mysterious old woman, Elisa finds her way through the woods to the sea, where she meets up with her brothers. They carry her over the ocean to the country where they live, a place of forests, mountains and castles. As she sleeps, a fairy comes to Elisa in a dream and tells her she can lift the enchantment from her brothers, provided she makes each of them a shirt out of nettles. But she must not speak a word till she has done: if she does, her brothers will die.

She begins the work, but she has only finished one shirt when the king of the country comes across her while he is hunting. He falls in love with her, takes her back to his castle, gives her 'regal gowns' and has her hair 'braided with pearls'. They marry, and she falls in love with him too, but is determined to press on with her task. The archbishop, however, believes she is a witch. He follows her one night when, having run out of nettles, she goes to a churchyard to collect more, passing by monsters which feast on the flesh of corpses to do so. The archbishop accuses her of witchcraft, the king can find no other explanation for her trips to the graveyard, and of course she cannot speak: he declares that the people must decide on her fate. They do – they say she's a witch and must burn. Still she keeps sewing, still she won't speak. Just in the nick of time, her brothers appear. She throws the shirts over them, and they are transformed into their real selves. (All except the youngest. His shirt is not quite finished, so he is left with a swan's wing instead of an arm.) Elisa, exhausted, collapses, seemingly lifeless. But then something magical happens: the faggots which had been used to make the pyre suddenly begin to grow, and in no time at all a hedge of beautiful red roses has appeared. At the very top is a single white one. The king plucks it, lays it close to Elisa's heart, and she comes back to life.

So – terrible things indeed. Some of the elements of this story are to be found in others too. There is the evil stepmother. She has the king: she doesn't want to be burdened with his twelve children. So they experience the sudden loss of an idyllic lifestyle; they sink from the top of the heap to the very bottom. There is the journey – the quest – through a forest. Forests, of course, were dangerous. They still are in many places (though not, perhaps, in our small island). In a real forest, you can quickly become disorientated and lose your way, and then you are at the mercy of fierce creatures: wild boar, wolves, and bears. In an enchanted one, there are other dangers too – witches, goblins, sinister trees.

Elisa is beset by dangers from the start. But once she sets about her task, she becomes even more vulnerable; she is not allowed to speak, so she cannot explain or defend herself. The king is kind and he loves her, but even he is a threat to her: he takes her away, without her permission, from where she needs to be. She has to go to the graveyard – it's the only place she can get fresh supplies of nettles – but in doing so, she lays herself open to the Archbishop's accusations. Then she falls victim to a mob: one day the people cheer her: the next they jeer and condemn her to a terrible death. The fickle affections of the mob are frighteningly real.

But she is not a passive victim. We know that she is only allowing all this to happen to her because she is ferociously loyal and determined. Even when she falls in love with the king, she still doesn't allow herself to be distracted. She loves her brothers and she is determined to keep to her commitment to save them, no matter how hard it may be. She may be a victim, but she's far from weak.

We talk of 'fairy-tale endings' as if fairy stories invariably end well. True, in the end Cinderella and her prince live happily ever after. So does the Sleeping Beauty; so does Snow White. But it isn't always so. In The Wild Swans, one brother is left with a swan's wing instead of an arm. Perhaps this is one of the things that makes this particular story so poignant; there's an admission that everything doesn't always turn out all right, no matter how hard you try. Fairy stories may take place in an enchanted land, but they deal with situations we must face in real life.

There is even something paradoxical about the enchantment. The stepmother wants to turn the princes into 'voiceless birds', but her power has its limits, and instead of becoming something ugly, they are turned into 'beautiful wild swans'. They are no longer princes, and their true lives have been taken away, but still they have been transformed into something wonderful: to borrow from Yeats, 'a terrible beauty is born': and they fly across the ocean at sunset to meet their sister like 'a white ribbon being pulled across the sky'. It's a lovely image and a lovely moment, as Elisa sees her brothers for the first time in so many long and difficult years.

The Wild Swans is about as far as you can get from the popular Disneyfied construct of what a fairytale is. Like a wild landscape, it is bleak and harsh. But, for me at any rate, it has also a beauty that touches the heart.

Sue Purkiss describes her first few stories as 'ghostie, witch fantasies for young children'. Her next two novels, 'The Willow Man' and 'Warrior King' are for older children. 'The Willow Man' is a contemporary story underpinned by the presence of the mysterious and magical figure of the 'Willow Man' or 'Withy Man', a huge outdoor sculpture by Serena de la Hey, set in a field near Bridgewater in Somerset. And 'Warrior King' is a re-imagining of part of the life of Alfred the Great – king of Wessex from 871 to 899, renowned for his learning, for his defence of England against the Danes, and in a legend once famous among schoolchildren, for burning those cakes.

Sue's books are grounded in the landscape of Britain, especially the beautiful county of Somerset where she now lives, which contains the original Isle of Avalon, the mysterious Glastonbury Tor, and the misty marshes where Alfred once hid from the Danes. Her most recent book, 'Emily's Surprising Voyage' is a story of Brunel's spectacular ship the SS Great Britain, now permanently in Bristol harbour. And she is currently working on a book set in World War II.

Published on April 06, 2012 00:45

April 3, 2012

Folklore Snippets - The Nidagrísur

From: "Scandinavian Folklore" ed. William Craigie, 1896

The Nidagrísur is little, thick and rounded, like a little child in swaddling clothes or a big ball of yarn, and of a dark reddish-brown colour. It is said to appear where new-born illegitimate children have been killed and buried without receiving a name. It lies and rolls about before men's feet to lead them astray from the road, and if it gets between anyone's legs, he will not see another year. In the field of the village of Skáli on Österö stands a stone, called Loddasa-stone, and here a nidagrísur often lay before the feet of those who went that way in the dark, until once a man who was passing and was annoyed by it, grew angry and said "Loddasi there," upon which it buried itself in the earth beside the stone, and was never seen again, for now it had got a name.

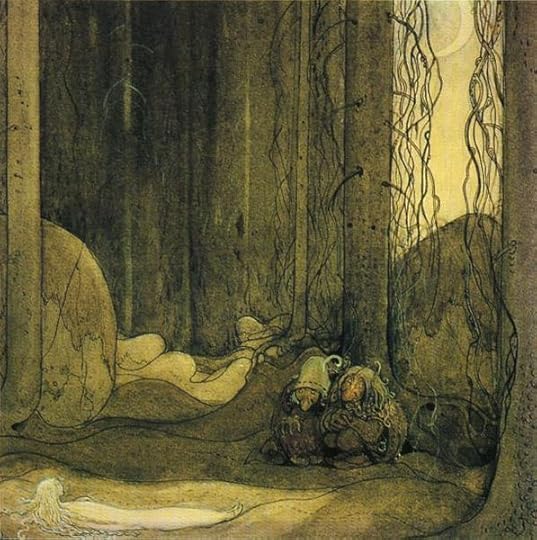

No Nidagrisurs available online, so here's a picture by John Bauer of a changeling child reared by trolls, 1913

No Nidagrisurs available online, so here's a picture by John Bauer of a changeling child reared by trolls, 1913

The Nidagrísur is little, thick and rounded, like a little child in swaddling clothes or a big ball of yarn, and of a dark reddish-brown colour. It is said to appear where new-born illegitimate children have been killed and buried without receiving a name. It lies and rolls about before men's feet to lead them astray from the road, and if it gets between anyone's legs, he will not see another year. In the field of the village of Skáli on Österö stands a stone, called Loddasa-stone, and here a nidagrísur often lay before the feet of those who went that way in the dark, until once a man who was passing and was annoyed by it, grew angry and said "Loddasi there," upon which it buried itself in the earth beside the stone, and was never seen again, for now it had got a name.

No Nidagrisurs available online, so here's a picture by John Bauer of a changeling child reared by trolls, 1913

No Nidagrisurs available online, so here's a picture by John Bauer of a changeling child reared by trolls, 1913

Published on April 03, 2012 02:20

March 30, 2012

"Jorinda and Joringel" - a new Fairytale Reflection

I was reminded by Celia Rees's post on Blodeuedd, the girl who was changed into an owl, of this haunting fairytale collected by the Brothers Grimm, which I first read many, many years ago. It's stayed with me ever since. It isn't well known – perhaps because although it's strong on emotional intensity, it's short on plot. But first, here's the story.

It tells of a castle in the middle of a dark and thick forest, inhabited by a single old woman who turns herself into the shape of a cat or screech-owl by day, assuming her own form only at night. She lures wild birds and beast to her, and kills and eats them.

If anyone came within one hundred paces of the castle he was obliged to stand still and could not stir from the spot until she bade him be free. But whenever an innocent maiden came within this circle, she changed her into a bird and shut her up in a wickerwork cage, and carried the cage into a room in the castle. She had about seven thousand cages of rare birds in the castle."

A young maiden called Jorinda is betrothed to a youth called Joringel, and in order to be alone together, the pair of them take a walk into the forest. Joringel warns Jorinda to take care: they must not stray too near the castle.

It was a beautiful evening. The sun shone brightly between the trunks of the trees into the dark green of the forest, and the turtledoves sang mournfully upon the beech trees,

but for some reason the young lovers – for whom everything should be wonderful - are sorrowful.

Jorinda wept now and then: she sat down in the sunshine and was sorrowful. Joringel was sorrowful too; they were as sad as though they were about to die. Then they looked around them, and were quite at a loss, for they did not know which way they should go home. The sun was still half above the mountain and half under.

Joringel looked through the bushes, and saw the old walls of the castle close at hand.

He was horror-stricken and full of deadly fear. Jorinda was singing:

"My little bird with the necklace red

Sings sorrow, sorrow, sorrow.

"He sings that the little dove must soon be dead.

Sings sorrow, sor- jug, jug, jug."

For the sun has set, Jorinda has been changed into a nightingale, and "A screech owl with glowing eyes flew three times about her and three times cried 'to-whoo, to-whoo, to-whoo!'"

Frozen to the spot and unable to speak or move, Joringel sees the owl fly into a thicket and immediately afterwards a crooked old woman 'with large red eyes' emerges, catches the nightingale and takes it away. She returns later and releases Joringel with the strange words, 'If the moon shines on the cage, Zachiel, let him loose,' but she refuses to release Jorinda, saying Joringel will never see her again.

Joringel does finally manage to release Jorinda with the aid of a magical blood-red flower containing a dew-drop as big as a pearl, with which he touches the doors of the castle and the cage itself and sets Jorinda and all the other maidens free; the sexual imagery is clear enough, and the happy ending is satisfactory if perfunctory; what is really memorable is the sorrowful beauty of the forest, the sadness of the lovers, the imagery of the birds, and the strange song Jorinda sings.

What's it all about? Not always a useful question. A fairytale should be read like a poem, or attended to in the same kind of way as we attend to music, allowing it to work directly on the emotions. For me, this tale strikes strange chords from the heartstrings. I might hazard a guess that the lovers are sad because they know they'll grow old and die, that evening is here and the day nearly over, because their young love may not last and the sun is already half beneath the mountain. Perhaps they're afraid of mortality, the grave, symbolised by the grim stone walls of the castle whose shadow immobilises them, and the old owl-woman whose voice is a lament.

Years ago in my early twenties I was walking through London with a girl friend. We were laughing and chattering, and a middle-aged woman passing by – she may have been elderly, but I think she was only middle-aged – leaned over and said in a low voice but with extraordinary venom, "One day you'll be like me." As a memento mori, it was quite something, and my friend shuddered, but we agreed later that we never would be like her. We would never, ever be that bitter.

Nevertheless, everyone recognises the fear and dread associated with thoughts of old age and death, and the loss of youth and beauty; and happy are those of us who can throw it off with no more than a brief shiver. For me this fairytale takes those dark emotions and transmutes them into something beautiful.

Picture credit: Arthur Rackham, Jorinda and Joringel

Published on March 30, 2012 00:44

March 26, 2012

Iris Schamberger's Fairytale Jewellery

As many of my friends already know, for my 25th wedding anniversary last week my husband bought me this really wonderful ring, a joyously-created fairytale castle with turrets and pinnacles and a green dragon, made by artist and silversmith Iris Schamberger, whose work is so delightful I feel sure you'd like to know more about her. I fell in love with her gorgeous jewellery last year on discovering her website, but it seemed right to wait for a special occasion before buying something.

I was seriously tempted by this beautiful Swan King...

and by this waterlily with a goldfish hiding under the leaves...

but in the end, it was her little castles that I truly fell for. Like this one:

You can see lots more of them at Iris's lovely website, Fairytale Jewellery - but first I've asked Iris to answer a few questions. Here they are!

Iris, how long have you been making fairytale jewellery?

I have been making fairytale jewellery for 22 years.

And what inspired you to choose fairytales as a theme for your work?

My first ring with a small castle on it, I made for myself to remember happy holidays in Southern France, where I saw such a castle on the top of a hill. I loved to tell fairytales and to read out fantasy stories to my son and my little daughter, so that stories became more and more a theme to my work.

What is your favourite fairytale, and why?

One of my favourite fairytales is "Frog Prince". Perhaps it is because the princess dares to throw the insistent frog against the wall and not to give him a kiss as he expects it. As the princess shows her honest feelings, her rage, she makes the frog turn to a prince.

(That's such a different new take on the Frog Prince! I'd always felt sorry for the frog, but you're right, he's really a prince after all, and why should she have to marry him - or take him to her bed - just for returning her ball? So when she shows her real feelings, she's drawing a line that sets their relationship on a truthful footing.)

Your jewellery is so detailed and beautiful - how much work goes into making a fairytale ring?

Making a fairytale ring is a lot of work. I often spend many hours by building it out of wax, but I love this job. With a heated needle I am modelling the little figures and putting them together. The dragon´s eyes or other details are so small, I often have to wear magnifying glasses.

When the ring out of wax is perfect, it is sent to a foundry for casting. Afterwards I have to do the finish: to solder little golden balls on the top of the towers or to mount some rubies or sapphires. At the end, the ring is provided with a multilayered fired varnish.

Magical rings often turn up in fairytales! If you could give your rings a magical power, what power would you choose?

I would choose the power of love of life and I hope it is truly there in my work!

I am quite sure it is...

Finally, here's a video of Iris at work.

Published on March 26, 2012 00:30

March 23, 2012

THE GIRL MADE OF FLOWERS by Celia Rees

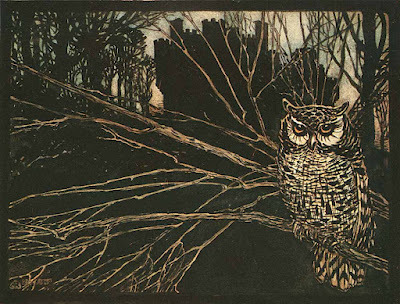

The 'Owl Service' plate design, which can be flowers or owls

The 'Owl Service' plate design, which can be flowers or owlsMyth and legend are very important to me. They inhabit a special, deep place in my mind and often appear in my work in unexpected ways. The surface matter might seem unconnected but the myths contain abiding and archetypal truths about human relationships and the human condition that have nothing to do with trivial considerations, such as time and place. While I was writing "This Is Not Forgiveness" , I was drawn to the story of Blodeuedd . My story would be a contemporary fiction, but this ancient story of two men who set out to create a woman from flowers, and two other young men who seek to possess her, seemed to contain the essence of my tale. While I was writing the book, I was drawn to the legend again and again.

'She wants to be flowers and you make her owls...' (The Owl Service, Alan Garner)

Blodeuedd is a story from the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion. I first came across it when I was eleven or twelve years old and reading my way through the Myths, Legends and Fairy Tales section of the school library. There, I discovered Lady Charlotte Guest's translation of the Mabinogion, that great collection of Welsh stories. I was familiar with Greek myths and legends, stories of the Norse gods, but these tales were new to me and they were our stories, stories from the British Isles. There were familiar characters, I recognised King Arthur, but this was not the Arthur I knew. There was a strangeness here and a power. Many of the stories did not make sense on first reading; there was a denseness about them, a feeling that the tales contained many stories, concentrated and packed together. This did not detract from my enjoyment. It merely added to the mystery. Here were kings, queens, magicians and shape shifters, golden ships, magic cauldrons, giants and dragons but behind them it was possible to sense something far more ancient, darker: more dangerous and more powerful.

I have continued to be fascinated by the Mabinogion, by its elusiveness and by its hints at other meanings, the remnants of a much more ancient storytelling tradition reaching back into an otherwise unknowable pre-history. The Mabinogion has proved a rich source of raw material for many of our greatest fantasy writers: Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Susan Cooper and, of course, Alan Garner who used the story of Blodeuedd as the basis for his novel The Owl Service.

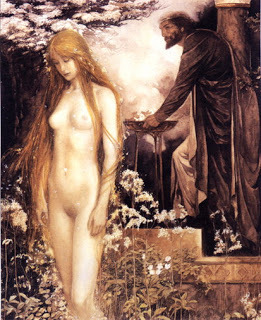

'Blodeuedd' by Alan Lee, 1984Then they took the flowers of the oak, and the flowers of the broom, and the flowers of the meadowsweet, and from these they conjured up the fairest and the most beautiful maiden that anyone had ever seen. And they baptised her in the way they had at that time, and named her Blodeuedd.

'Blodeuedd' by Alan Lee, 1984Then they took the flowers of the oak, and the flowers of the broom, and the flowers of the meadowsweet, and from these they conjured up the fairest and the most beautiful maiden that anyone had ever seen. And they baptised her in the way they had at that time, and named her Blodeuedd. (The Mabinogion trans. Sioned Davies)

She is made from the sweet smelling flowers of summer, gold for beauty, white for purity. 'They' are Math, a powerful magician, and his nephew, Gwdyion, shape shifter and story teller. They are making a wife for Lleu Llaw Gyffes, miraculous child and now strapping young man. The boy's mother, the great queen Aranrhod, will not own him and Math and Gwdyion resort to trickery to get her to grant him the trappings that will mark him as noble: a name, arms, a wife. They have already tricked her into naming and arming him but she has got wise to their wiles and places a bane upon the boy: 'He will never have a wife from the race that is on this earth.' Undeterred, Math and Gwydion make him a woman out of flowers but they cannot control her. They cannot make her love Lleu, or prevent her from falling in love with another: Gronw Pebr, lord of Penllyn, who is staying in her house. When Lleu is called away, she betrays him with his guest. Even though Lleu is protected and can only be killed in the most bizarre and unlikely set of circumstances, she manages to overcome protections to enable Gronw to kill him with a spear. Lleu is, of course, no ordinary mortal, so at the moment of his death he changes into an eagle. Gwydion finds him and restores his true self. Then Gwydion goes after Blodeuedd. In punishment for what she has done, he turns her into an owl.

'I will not kill you. I will do worse. Namely, I release you in the form of a bird … you will never dare show your face in daylight for fear of all the birds … You shall not lose your name, however, but will always be called Blodeuwedd. Blodeuwedd is owl in today's language and for that reason the birds hate the owl and the owl is called Blodeuwedd '

Gronw Pebr, the adulterous guest, does not escape punishment. He is made to stand on the same spot where Lleu he was standing when he was killed. He is allowed to put a stone between himself and his attacker, but Lleu's spear goes through the stone and kills him. So ends the story of Blodeuedd, and so ends the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion.

I like magicians who make mistakes. Their mistake is to think that they can make a woman out of flowers, or anything else, and expect to control her, or crucially expect her to obey human rules. It is all bound to go hideously wrong. On the other hand, you cannot get away with breaking the universal, ancient and binding obligations of a wife to her husband, or a guest to his host. Those who do so will inevitably be punished.

The mistakes, the misplaced love, the infidelity, the punishment, all make the story very human. One of the most intriguing aspects to the story is its association with an identifiable place: Nantlleu – the valley of Lleu. The Nantlle(u) Valley is located along the Llyfni river to the east of Pen-y-groes and Tal-y-sarn in North Wales. Even more intriguingly, a stone pierced with a hole was found in a local river in 1934. This gives the story an unusual and powerful validity, a sense that these things really happened in this place, something not lost on Alan Garner, when he set his modern re-telling in this actual valley. Behind these characters, however, stand greater, more shadowy figures, hinted at by the powers, abilities, and often names associated with them. Lleu, for example, is set apart by the bane upon him, his special protection, his great strength and above all his name which associates him with Lugh, the Celtic god, who is, in turn, identified with Mercury.

Barn owl by Arthur Rackham (illlustration to 'Jorinda and Jorindel')

Barn owl by Arthur Rackham (illlustration to 'Jorinda and Jorindel')Then there is the enigma of Blodeuedd herself. Math and Gwdyion don't destroy her. How can they? She is their creation. They make her into an owl. Somehow, in doing this, they exchange the grounded passivity of flowers for something far more potent. They give her wings and a whole new set of associations. She still has beauty. In my mind, she becomes a barn owl, one of our most beautiful native birds. In becoming an owl she takes on other meanings: fierce hunter, ghost-like harbinger of death, but also potent and universal signifier of knowledge and wisdom. These different aspects echo the dual and triple aspects of many goddesses. Blodeuedd uses her wings to fly back through time and across space, to perch on the shoulder of the Greek goddess Athene, and stand next to the great Babylonian goddess, Ishtar, who is often shown with the feet of a bird - and flanked by owls.

'This Is Not Forgiveness' by Celia Rees is published by Bloomsbury, £6.99

Published on March 23, 2012 01:11