Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 41

November 28, 2011

Magick

Magick happens.

Or at least I think it can.

Magick can happen when a bunch of friends get together to do something lovely for another friend. And that's what's happening here.

When I lived in the States, one of the most touching things from time to time would be a fundraising event, often very local, to help someone in need. Perhaps someone needed expensive medical treatment, uncovered by insurance. Once, my children came home to tell me a schoolfriend's house had burned down overnight and the family was living in a trailer - this, in winter, with temperatures way below zero. There can be all kinds of reasons. Sometimes it's not necessary to detail them, and this is one of those sometimes.

But right now I'd like to direct you all to a site dedicated to raising a bit of magick for a friend of mine, wonderful editor, writer and artist Terri Windling. I know that many of you lovely people who visit 'Steel Thistles' are interested in fantasy, folklore, and magic of all sorts. So please do go and visit this on-line auction, Magick4Terri, where you can bid for signed artwork, signed books and all sorts of other things by people like Holly Black, Brian and Wendy Froud, Elizabeth Hand, Cassandra Clare, Jane Yolen, Tamora Pierce and Charles Vess - to name but a few. What a wonderful Christmas present any of these could be!

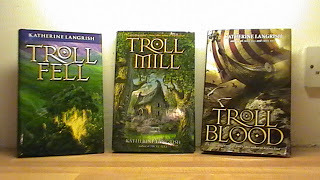

My own contribution to the auction is pictured above, so if anyone fancies a signed set of the hardcover US edition of my Troll trilogy, that's there too.

IF there were dreams to sell,

Here there ARE dreams to sell! Do go and take a look, and I hope you get lucky and buy some...

Quotation from: 'Dream Pedlary' by Thomas Lovell Beddoes

Published on November 28, 2011 09:33

November 27, 2011

A Blogging Award!

It was a splendid surprise this morning to check the comments on my last post - not actually expecting to find any, since it ran to all of a meagre two sentences - and discover my fellow fantasy writer Katherine Roberts has presented me with a blogging award!

It seems Liebster is a German word meaning "dearest", and the award is given to up-and-coming bloggers with less than 200 followers (and Steel Thistles isn't there yet!). So many thanks to Katherine, whose own blog 'Reclusive Muse', besides being the only one on the internet run by a unicorn, is full of fascinating insights into fantasy fiction, e-publishing, and interviews with other writers - click on her 'Muse Mondays'.

According to Katherine, or possibly the unicorn, these are the things you should do if you receive the award:

1. Thank the giver and link back to the blogger who gave it to you .

2. Reveal your top 5 picks and let them know by leaving a comment on their blog.

3. Copy and paste the award on your blog (tick).

4. Hope that the people you've sent the award to forward it to their five favourite bloggers.

And this is the best part, because it gives me the chance to tell you about five utterly terrific blogs and urge you to flock to them. In no particular order...

First on the list is Susan Price's 'A Nennius Blog'. Nennius - as the Dark Age scholars amongst us will know - was a ninth century monk who wrote a 'History of Britain' full of wonderful scraps of legend, myth as well as bits of genuine history: as he says himself, 'I have made a little heap of all I've found'. At 'A Nennius Blog' you will find a similar fascinating miscellany of ghost stories, book recommendations and tales about writing, from Susan Price, one of Britain's best fantasy writers - as well as 'Blot', a cartoon cat and writer's muse of devilish insight and cunning.

Second is my other home 'The History Girls' - a daily blog for anyone who loves historical fiction, whether for adults or children, whether straight or with a fantasy twist.

Third is 'John Barleycorn Must Die' where you can follow the birth and gradual growth of a graphic novel - along with round-the-table interviews with artists such as Alan Lee and David Wyatt, plus discussions about magic, the Tarot, and the creative process. I'm amazed there aren't already 200 followers, but go and visit!

Fourth is Beneath the Bracken, an artist's blog: a blend of beautiful photographs and thoughtful, introspective commentary with themes of change, growth, and poetry.

Fifth is 'Fantastic Reads' - a blog about children's reading and literature with well-written and thoughtful recommendations. I should warn you that the current post includes a favourable mention of my own 'Troll' books, but that's honestly not why I'm putting it here.

So thanks again to Katherine and her unicorn - and I do hope you'll enjoy these links.

It seems Liebster is a German word meaning "dearest", and the award is given to up-and-coming bloggers with less than 200 followers (and Steel Thistles isn't there yet!). So many thanks to Katherine, whose own blog 'Reclusive Muse', besides being the only one on the internet run by a unicorn, is full of fascinating insights into fantasy fiction, e-publishing, and interviews with other writers - click on her 'Muse Mondays'.

According to Katherine, or possibly the unicorn, these are the things you should do if you receive the award:

1. Thank the giver and link back to the blogger who gave it to you .

2. Reveal your top 5 picks and let them know by leaving a comment on their blog.

3. Copy and paste the award on your blog (tick).

4. Hope that the people you've sent the award to forward it to their five favourite bloggers.

And this is the best part, because it gives me the chance to tell you about five utterly terrific blogs and urge you to flock to them. In no particular order...

First on the list is Susan Price's 'A Nennius Blog'. Nennius - as the Dark Age scholars amongst us will know - was a ninth century monk who wrote a 'History of Britain' full of wonderful scraps of legend, myth as well as bits of genuine history: as he says himself, 'I have made a little heap of all I've found'. At 'A Nennius Blog' you will find a similar fascinating miscellany of ghost stories, book recommendations and tales about writing, from Susan Price, one of Britain's best fantasy writers - as well as 'Blot', a cartoon cat and writer's muse of devilish insight and cunning.

Second is my other home 'The History Girls' - a daily blog for anyone who loves historical fiction, whether for adults or children, whether straight or with a fantasy twist.

Third is 'John Barleycorn Must Die' where you can follow the birth and gradual growth of a graphic novel - along with round-the-table interviews with artists such as Alan Lee and David Wyatt, plus discussions about magic, the Tarot, and the creative process. I'm amazed there aren't already 200 followers, but go and visit!

Fourth is Beneath the Bracken, an artist's blog: a blend of beautiful photographs and thoughtful, introspective commentary with themes of change, growth, and poetry.

Fifth is 'Fantastic Reads' - a blog about children's reading and literature with well-written and thoughtful recommendations. I should warn you that the current post includes a favourable mention of my own 'Troll' books, but that's honestly not why I'm putting it here.

So thanks again to Katherine and her unicorn - and I do hope you'll enjoy these links.

Published on November 27, 2011 04:24

November 25, 2011

This morning...

... I am to be found at Awfully Big Blog Reviews, talking about Franny Billingsley's wonderful wild and witchy 'Chime'. It blew me away, I tell you.

Heading off to London now, but back on Seven Thistles in a day or two: and the AgonyAunts are arriving next Friday...

Published on November 25, 2011 00:37

November 22, 2011

"Midnight Blue"

Today I'm celebrating the re-release, as an E-book, of a strange and wonderful YA novel: Pauline Fisk's 'Midnight Blue', which won the Smarties Book Prize in 1990. It's the story of a young girl, Bonnie, who is about to begin a new life with her mother away from the influence of her controlling and malevolent grandmother. But the grandmother finds them and Bonnie runs away, finding refuge in a mid-city oasis, a walled garden in which a mysterious man called Michael is building a hot air balloon with the help of a strange shadowy boy. Michael's aim is to fly to the land 'beyond the sky. Not 'in outer space' or 'in another galaxy', but beyond the sky… as though it were possible to peel away the edge of the blue and pass straight through.'

Today I'm celebrating the re-release, as an E-book, of a strange and wonderful YA novel: Pauline Fisk's 'Midnight Blue', which won the Smarties Book Prize in 1990. It's the story of a young girl, Bonnie, who is about to begin a new life with her mother away from the influence of her controlling and malevolent grandmother. But the grandmother finds them and Bonnie runs away, finding refuge in a mid-city oasis, a walled garden in which a mysterious man called Michael is building a hot air balloon with the help of a strange shadowy boy. Michael's aim is to fly to the land 'beyond the sky. Not 'in outer space' or 'in another galaxy', but beyond the sky… as though it were possible to peel away the edge of the blue and pass straight through.' Bonnie and the shadow-boy fly without him, '... racing for the top of the sky. Its warmth welcomed them, turned the dark skin of the fiery balloon midnight blue... Then the smooth sky puckered into cloth-of-blue and drew aside for them, like curtains parting.' On 'the other side of the sky' Bonnie wakes in a farmhouse on Highholly Hill, a place of legends where Wild Edric and his fairy wife Godda are said to emerge from the caverns and ride by night. She is welcomed by a warm-hearted but strangely incurious family, whose daughter Arabella is Bonnie's living image: herself as she might have been in a different, secure life. But Bonnie struggles with jealousy and hatred. And then her grandmother reappears, a sinister, knowing figure with the power to suck away the essence of a person and leave a simulacrum behind...

If you want to see Highholly Hill, here it is, crowned with 'Wild Edric's Throne' - and it's also in the photo at the head of this blog! It is in fact the magnificent and brooding hill called Stiperstones, in Shropshire on the Welsh border, and I used it in my own book 'Dark Angels' and called it 'Devil's Edge.

All the things I love in a book are to be found in 'Midnight Blue' - mystery and magic, a strong sense of place, deep emotional feeling and beautiful writing. I highly recommend it, and I'm delighted to be able to welcome Pauline herself to the blog, as part of her 'Midnight Blue' tour.

Pauline, can you remember what impulse triggered the writing of this, your first book? What was the kernel, the seed of the idea that became Midnight Blue?

Writing a book has something of the snowball-making process about it. You start with a tiny handful of something scrunched up tight in your brain, then you roll it round and it starts to grow. You roll and roll and finally it becomes so big that it takes on a life of its own and starts rolling away from you. That's when the writing has to begin.

Writing a book has something of the snowball-making process about it. You start with a tiny handful of something scrunched up tight in your brain, then you roll it round and it starts to grow. You roll and roll and finally it becomes so big that it takes on a life of its own and starts rolling away from you. That's when the writing has to begin. The heart of my snowball came down to three things. Firstly, I'd long wanted to write a children's novel featuring balloon-flight, maybe with sky-gypsies or something like that, but the paraphernalia of modern ballooning didn't sit easily with what I envisaged. Secondly, when I came to live in Shropshire, I discovered a folklorist called Charlotte Burne whose 'Shropshire Folk-lore', published in the mid nineteenth century, included the story of a sleeping knight called Wild Edric. Thirdly, whilst our own house had builders in, my family and I were privileged to spend one autumn living in a remote hilltop farmhouse overlooking the Stiperstones and Wild Edric's haunt, the Devil's Chair. In the book it became Highholly House. I wanted to honour it as something magnificent which had stood through the centuries, enduring the elements and the passage of time. I was aware, when we moved out, that it would probably never be lived in again.

Many writers, wanting to send their characters into another world, would use some kind of magical talisman or spell. I'm fascinated by your use of the hot air balloon to send your character Bonnie away…it's physical travel to a physical place, High Holly Hill - yet in some sense unreal too. Where did the image of the hot air balloon and the parting of the sky come from?

The idea of ballooning as a means of escape really came alive for me when I read Jim Woodman's 'Flight of Condor I', describing how he and Julian Nott built, launched and flew a balloon over the desert at Nazca, Peru, powered only by smoke and flames. As soon as I read about their amazing dawn launch, I knew what shape I wanted my novel to take. Yes, a physical trip and, yes, to a physical place. But powered through the air by fire – how magical was that?

As to the sky parting – I suppose I've always seen the sky as a sort of stage putting on a show, so to imagine the blue as a set of curtains doesn't seem that far fetched. There's more to the sky than space, just as there's more to life than science - and it's this 'more' that's always really interested me in my writing life. In 'Flying for Frankie' - which also features a balloon flight - my heroine says, 'We peeled back the edges of our world and found out there was more.' For her, the 'more' is understanding who she is and what her place is in the scheme of things. But for Bonnie, the heroine of 'Midnight Blue', 'more' is literally more. More Maybelle. More Michael. More Highholly House. More of herself. And more of the dreaded Grandbag too.

One of the things I love about this book is that you don't seem to feel the need to provide rationales for everything. Much is left unexplained – yet it all feels natural, as if we understand the story on a deep, symbolic level. Did you write the book this way instinctively, or was it consciously planned?

This is something I feel so strongly about that it's hard to know where to start - or how to keep it short. Yes, instinctively I shy away from explanations. Perhaps, even in struggling to answer you now, I'm doing that. But how many books have been ruined by explanations? Oh, those terrible last chapters where the pieces are put together and the ends are tied up and all the author's hard work creating a believable alternate reality is suddenly undone!

After all, real life isn't like that. It very often doesn't have explanations - at least not ones that are handed on a plate. Especially for children – and it's children I'm writing for – life just happens. It's a mystery functioning on a level that goes deeper than mere words.

Take what happens to Bonnie when she arrives in Highholly House. From the adult perspective, the people who've taken her in should ask who she is, where she's from and whom they can phone. But from Bonnie's perspective, it might be unsettling that they don't, but she accepts it. Things are happening all the time in her child's life for which there are no words or explanations. That's just life.

It would be nice to say that I've taken a stand here, refusing to bow to adult requirements for what a story should be. But to be honest it's happened more naturally than that. I've simply put in what I felt Bonnie's story needed, and left out what I felt might ruin it, hoping that, as she learns to see the world anew, my readers would go through that experience seeing with her eyes.

Bonnie runs away from herself as well as from an intolerable situation, and finds, at the farm on Highholly Hill, the ideal family she might have had in a parallel universe. But she doesn't belong there. Would you say that Midnight Blue is very much a story about identity?

Who is Bonnie? Nobody knows, least of all herself. Who's Arabella? She's not the 'Arabella-thing' that steps out of the magic mirror. Who is the shadowboy? Only when he takes on flesh and blood, giving up his magic past, can he begin to feel. Yes, indeed, 'Midnight Blue' is a book about identity. What is it that makes us human? When characters in Philip Pullman's 'His Dark Materials' are separated from their daemons, the most awful thing in the world becomes reality – they are no longer truly human. Again, in Ray Bradbury's wonderful 'Something Wicked This Way Comes', people stumble home from the fair stripped of their years, their memories and all their experiences. And similarly, in 'Midnight Blue, when Jake and Arabella stumble into the magic mirror, they emerge with the shape of their humanity still intact, but devoid of life.

The truly terrible thing about Grandbag isn't her possessiveness. It's what she wants to possess. And what she wants is just that - life. She's drained it out of grey, limp Doreen, moved onto Maybelle, tried with Bonnie and now she's started on Bonnie's friends on Highholly Hill. And, it's in fighting for Highholly Hill, at the ultimate cost to herself, that Bonnie finds her place in the world and discovers who she really is.

Though 'Midnight Blue' is so mysterious and mystical, it feels real and grounded because of its strong sense of place. First the city which Bonnie flees, and then the dramatic landscape and legends of Shropshire, are essential ingredients of this book and many of your others since. What is it about the Shropshire hills that speaks to you?

Oh, there's a question! In a sense I'm Bonnie, fleeing the city and finding another, better world among the Shropshire hills. I grew up in London. In fact the flats from which Bonnie flees were ones I used to pass sometimes on the bus. I never felt rooted there, though. Maybe it was because my mother came to England as a refugee from the Channel Islands, fleeing Hitler's invasion during the Second World War, I don't know. Certainly she did her best to fit in, but her sense of belonging somewhere else was always there, and perhaps it rubbed off on me.

But why Shropshire? The first time I visited the county, I was driving through on my way to North Wales. The mountains were beautiful, but the horizon enclosed me and made me feel claustrophobic, and the rolling, open greenness of the Shropshire hills felt so much more open and liberating.

I moved here to live in 1972 and have been here ever since. I suppose I was a rootless person looking for roots, and the roots came in family [husband, five children, a series of dogs], and the enjoyment of the Shropshire hills became part of our shared experience.

But it's my own personal experience too. There's a great joy that comes from being alone out in the hills. I love the sense of space. I love being able to walk and rarely cross a road or see a soul all day, or see a thing that isn't beautiful or hear a sound that isn't made by birds or wind or sheep. And I've done this so often that the land feels like my second skin. I know where the finches nest; where the white violets come up in spring; where I just might see otters if I'm lucky, or wild orchids. What speaks to me about the Shropshire hills? It's the voice of home.

What, for you, is the purpose of fantasy fiction?

Purpose. Hmm. In order to attempt to answer this, I'm going to quote from another of my novels, 'The Beast of Whixall Moss'. My hero has found, and lost, a fabuous six-headed beast, and he's in mourning. Then one morning he wakes up and the garden is full of beasts, and they're all fabulous and this is what he thinks: 'This was what it meant to have vision. He knew at last. Not striving for things, hoping until hope had gone, as Mum had done, nor grasping for things in a frenzy of desire as he had done. But, amid the ordinary things of life, unasked for and unheralded, this act of sight.'

The key here, more even than those words 'act of sight', is the phrase 'ordinary things of life'. I think that the purpose of fantasy isn't so much to escape ordinary life as to shine light upon it. Being taken to the edge of human experience allows us to look both ways – out into the unknown and back into what we think we know all too well, but maybe don't. Tolkien talks about the realm of fairy-story being ' wide and deep and high and filled with many things: all manner of beasts and birds are found there; shoreless seas and stars uncounted; beauty that is an enchantment, and an ever-present peril; both joy and sorrow sharp as swords.' But you could say the same things about the world we live in. It's just that fantasy casts things in a heightened light.

It's back to what I was saying earlier about the sky as a stage. Fantasy's like a spotlight which illuminates life. It takes us out of ourselves and brings us back, changed yet scarcely knowing we've been away

Thankyou Pauline!

MIDNIGHT BLUE ASIN NO : B0062F6K10 PRICE: £2.99 BUY THIS BOOK

Or READ A FREE SAMPLE at the author's lovely new website

For a recent review of Midnight Blue, visit The Bookbag

Read Pauline's account of living in the ancient farmhouse on Stiperstones at Reclusive Muse

Discover how she came to be a writer at Book Angel Booktopia

Visit Authors Electric for an account of how Midnight Blue became an E-book

Published on November 22, 2011 01:05

November 17, 2011

"Runelight"

Well, here is the rather lovely cover of 'Runelight', the long-awaited sequel to Joanne Harris's first Norse fantasy 'Runemarks'. I've already written about that, but to remind you (and urge you to read the book if you haven't already), here's a link to the Fairytale Reflection Joanne wrote for this blog back in July, about her fascination with the story of the Pied Piper. As I said then,

Well, here is the rather lovely cover of 'Runelight', the long-awaited sequel to Joanne Harris's first Norse fantasy 'Runemarks'. I've already written about that, but to remind you (and urge you to read the book if you haven't already), here's a link to the Fairytale Reflection Joanne wrote for this blog back in July, about her fascination with the story of the Pied Piper. As I said then,"'Runemarks' is a wonderful concoction of Norse legend and fantasy. It grabbed me from the opening sentence: 'Seven o'clock on a Monday morning, five hundred years after the End of the World, and goblins had been at the cellar again.' And soon after that, the brave and independent heroine Maddy Smith, born with a runemark (or ruinmark) on her hand, is off exploring the labryrinthine caverns under Red Horse Hill with a goblin guide, hunting for the mysterious 'Whisperer' at the instigation of her old and ambiguous mentor, One-Eye. A magnificent adventure follows."

And here is the Red Horse of Red Horse Hill on the cover above: and now, in 'Runelight', Maddy has a counterpart. Maggie Rede is her twin sister, though neither of them knows it. The child of a harsh upbringing, she patrols the catacombs of the city of World's End, full of religious zeal for the Good Book and the Order. But she's also romantic and untaught, and perhaps it's not surprising when she falls in love with exactly the wrong person – mean-eyed Adam, possessed by the spirit of the sinister 'Whisperer'.

It's hard not to love Maggie: she's so brave and gallant – and so deluded. And she and Maddy are on exactly opposite sides... For there's a prophecy: Three Riders with swords of flame will come to purge the Worlds. It all rises to a nail-biting climax as Maddy, with the reluctant help of Loki, battles to save her long-lost sister and rebuild Asgard, citadel of the gods, in time to save the Nine Worlds from being engulfed by Chaos.

I was looking forward immensely to reading 'Runelight' and I wasn't disappointed. It's a grand extravaganza of a book, and – at nearly 600 pages – one to really settle down with and take time over. Because Joanne Harris is known mainly for her adult books, I've noticed a certain amount of what seems to me unnecessary head-scratching about this one. Is it for children? Is it YA? Is it for adults? But books are 'for' anyone who can read and enjoy them. Changing mythologies for a moment, there's a Greek story about a man called Procrustes, a bandit who forced his victims to fit an iron bed he had made, either by physically stretching them or by cutting off their arms and legs. Many a book is laid on the Procrustean beds of the kids/YA/adult categories. Some fit well, but there are others which are bigger. They spill over, and rather than complain about it, or squish them in or lop bits off, it's better to remember that these categories are really arbitrary and no one can define them anyway. And so 'Runelight' is for any reader, young or old, who can cope with a complex, gradually unfolding story, drama, humour and pathos, a large cast of brilliant characters and a myriad witty allusions to Norse mythology.

Like the Norse myths themselves, as they've come down to us in the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson, 'Runelight' is often very funny and irreverent, and whether you know the myths or not there is plenty to appreciate. I loved Joanne's take on the awesome Midgard Serpent Jörmungandr, who acts as Maddy's steed 'Jorgi' in horse shape: somnolent and slimy and continually snacking on seafood. And how come I never thought of Odin's eight-legged horse horse Sleipnir as a spider before? And then there's Sif of the Golden Hair (note those capitals) – a self-important beauty with a strong resemblance to a pig. And Loki, of course, Dog Star and Trickster, always out for himself yet somehow always managing to do the right thing. And last but not least, Odin – who can never be trusted at all, even when he's clearly dead...

I can't think of a nicer thing to do on a cold autumn or winter evening than to curl up in a big chair, turn on the lamp, and open this book to the first page:

Five past midnight in World's End, three years after the End of the World, and, as usual, there was nothing to be seen or heard in the catacombs of the Universal City – except of course for the rats and (if you believed in them) the ghosts of the dead...

Runelight is published by Doubleday

Published on November 17, 2011 01:23

November 11, 2011

Mystical Voyages (9) ...Or Were They Real?

Argo's sail against the light

Argo's sail against the lightWell, what if they were real? What if some or any of the Mystical Voyages I've been talking about during this series actually happened? What if they weren't mystical at all, but physical voyages to real physical places? Perhaps Odysseus, Jason, Maeldune, Bran, and Brendan were real people whose adventures simply got added to over the centuries and millennia - as real as Arthur anyway, who scholars suspect did exist, even if he never had a Round Table, even if he isn't sleeping in some cave surrounded by knights and white horses, waiting in suspended animation for the day when he will arise to save Britain from its last peril.

It doesn't affect the magic of the legends to suppose that there may be a core of truth in some of them. In fact, it'd be odd if there wasn't, and reams of paper and pints of ink have been expended in attempts to trace the actual course of Ulysses or the Argo from port to port across the ancient Mediterranean world. And why not? Not only are Ithaka and Sandy Pylos and Troy, Cape Malea and Colchis real places: but there are intriguingly detailed descriptions like this:

There is a rocky island there in the middle channel

halfway between Ithaka and towering Samos

called Asteris, not large, but it has a double anchorage...

White-capped waves mean dangerous sailing

White-capped waves mean dangerous sailingSometimes, though, better than paper and ink is to get out there and do it yourself. So thought the explorer Tim Severin when, in May 1976, he set out from the west coast of Ireland in a boat named Brendan, stitched together from forty-nine ox hides, heading for the Faroes. Rowing and sailing, he and his crew got there in June and carried on, arriving in Iceland in July. The following summer, Severin and his crew set out again, sailing from Iceland to Newfoundland, which they reached less than two months later, thus proving - not the unprovable, that Saint Brendan had really sailed to the coast of North America - but that an early medieval Irish coracle was at least capable of making the voyage.

Perhaps when you've done one voyage like this, you ache to do it again: at any rate, like Thor Heyerdahl before him, Tim Severin has famously continued to recreate archaic voyages. His second expedition, in 1984, was in 'Argo', a reconstruction of a Mycenean galley, following as nearly as possible the course of Jason and the Argonauts across the Mediterranean and up the Bosphorus and on to Georgia, land of the Golden Fleece.

Argo's beaked prow

Argo's beaked prowAnd here it gets personal, because in summer 1984 as the expedition was returning from Georgia via Istanbul, a sunburnt young man called David, who happened to be my boyfriend and who had decided that the way to relax after three years of studying physics at London's Imperial College would be to back-pack solo around Turkey, had a certain encounter in an Istanbul post-office. I'll let him take up the tale:

DAVID'S STORY

David does the dishes, Argo fashion

David does the dishes, Argo fashionThree men with arms like legs approached me. "Are you English?" They'd observed me apparently cracking the code of the Turkish phone system - 5 minutes puzzling over a huge, flabby directory in a dingy Istanbul post office, 1984 - and getting as far as making a call (to the British Embassy, unsuccessful). I clued them in on how the phones worked. "But what's that?" said I, peering intently at their T-shirts, from which protruded their Olympic scale arms:

ΑΡΓΟΝΑΥΤΙΚΑ

At anchor

At anchorNow any self respecting physicist, but more especially a graduate of Patrick Moore's 'Observer's Book of Astronomy', c.1969 (alpha-this, gamma-that is conspicuous in the winter sky, etc), should be able to read alphabetical greek... "Argonautica... is that the Tim Severin expedition?" - the one I'd read about in my father's Telegraph supplement? I'd just sailed back from Trebizond on the regular ferry after back-packing around Turkey. They'd just rowed a thousand miles in the opposite direction from Volos (Iolcos) to Georgia; their tremendous callouses bore witness to that fact, and to pretty useless winds. But they'd reached Jason's destination and found that people still "pan for gold" using sheep fleeces there, in the mountain streams.

Rowing hard...

Rowing hard...

I enthused, madly, and was told Tim was planning to sail Αργο next year, this time following the homeward trek of Ulysses from Troy. Versus the geographically exact Apollonius who wrote down 'Jason', Homer gives few recognisable locations for the Odyssey (and so providing Tim with the rationale for another clue searching expedition) but all the book-men agreed that the land of the Lotus Eaters simply must have been Libya. That sounded exciting! so I managed to persuade Tim to take me on for that (middle) leg of the voyage. Unfortunately, Colonel Gaddafi wasn't in the mood even for a bunch of adventurers in a Mycenaean galley and Tim spent days away on a fruitless trip to various Libyan consulates in search of promised visas (and that was before the Reagan / Thatcher raid on Tripoli).

Old and new

Old and newBut we did find plenty of traces of the legend around and along the Cretan coast, from the island whose earlier name was "Leather Bag", situated at the crossroads of the Aegean, to a very good candidate (with local backing) for the Cyclops cave, complete with British wartime ration tins in the back, dropped for the Resistance. One could imagine P.L. Fermor having been another visitor, once.

Viewed from the cliffs

Viewed from the cliffs

And we did find out what a very difficult job it is sailing a square rigger with no keel and simple rig in a season with way too much wind: and it's pointless rowing with 30 degree roll - so our callouses were nothing much to show. No wonder it took him 9 years to get back. Our particular Argo is no more (a sad story) but I did hold one of her great, heavy oars again in a ship museum in Eyemouth of all places. And identifed the black ring where the lead counterweight was jammed on, perfectly positioned to thwack into the spine of the rower in front if you got your stroke wrong. A thousand miles of that? They must have been heroes.

Argo under full sail

Argo under full sailStuck at home like Penelope, I was extremely envious, of course. (I finally got the envy out of my system a few years ago learning to sail a reconstructed Viking age ship on a Danish fjord.) But there were no women on the voyage and in any case I obviously didn't have the Olympic-style muscles required for the job. So I whiled away some of the time by thinking up adventurous things I could do on my own, such as going up in a glider - I know - feeble by comparison - and some of the time composing and illustrating my own spoof Mystical Voyage, 'Jason and the AgonyAunts: a silly tale in eight fits', which I gave David when he got back and which I'm going to post on this blog over the next few weeks, beginning on November 25. (For the benefit of American readers, an 'Agony Aunt' is the cheery British term for an advice columnist in a magazine or newspaper.) It's just a bit of fun, but I enjoyed making it and I hope you'll enjoy reading it.

And David? Well, what do you think? Reader, I married him.

Picture credits: All photos by David Gahan, except for 'Argo under Full Sail' by Rick Williams: all photos copyright Tim Severin and used by kind permission of Tim Severin

Further reading: The Jason Voyage and The Ulysses Voyage by Tim Severin

Published on November 11, 2011 00:58

November 10, 2011

"FORSAKEN"

Mara's mother is missing, her little brother is sick, maybe dying, her father is grieving. It all seems hopeless - until Mara sets out on a life-or-death journey to bring her mother home.

Mara's mother is missing, her little brother is sick, maybe dying, her father is grieving. It all seems hopeless - until Mara sets out on a life-or-death journey to bring her mother home.Please excuse a quick interruption to service (Mystical Voyages will be back tomorrow) so that I can do a little dance and tell you that my mermaid book 'Forsaken' is published today by Franklin Watts/EDGE, along with three other titles by Ali Sparkes, Andy Briggs and Joe Craig in a series called Rivets.

All four in the series are short stories individually published, intended for readers of nine plus who aren't confident about tackling thicker volumes.

'Forsaken' is - along with most of my other books - based on folklore, on a tale which is most famously the inspiration for Matthew Arnold's beautiful 19th century poem 'The Forsaken Merman' - the story of a merman who marries a human woman, Margaret.

COME, dear children, let us away;

Down and away below.

Now my brothers call from the bay;

Now the great winds shoreward blow;

Now the salt tides seaward flow;

Now the wild white horses play,

Champ and chafe and toss in the spray.

Children dear, let us away.

This way, this way!

The merman, who speaks the poem, has married a human woman, Margaret. They lived happily together under the sea till one day she heard church bells ringing in the world above, and felt a sudden longing to go and pray. The merman agreed to part with her for a short visit but once on land she never returned to the sea, leaving her husband and little mer-children desolate.

Come away, away, children.

Come children, come down.

The hoarse wind blows colder;

Lights shine in the town.

She will start from her slumber

When gusts shake the door;

She will hear the winds howling,

Will hear the waves roar.

We shall see, while above us

The waves roar and whirl,

A ceiling of amber,

A pavement of pearl.

Singing, 'Here came a mortal,

But faithless was she:

And alone dwell for ever

The kings of the sea.'

I read this poem many times as a child and always loved its lilting, changing rhythms and the beauty of its descriptions, as well as feeling sorry for the poor, heartbroken merman. It's the opposite of the Selkie story which I use in 'West of the Moon': about the fisherman who takes a selkie bride, and the message of both tales seems to be about the attraction of the Other, as well as the difficulty of living with it. Of course the old belief about merfolk - as for all faerie folk - was that unlike human beings, they had no souls. Margaret fears she too will lose her immortal soul and her chance of heaven if she stays with the merman. This fear leads her to abandon her husband and children. And here is an eternal question, one still being asked and played out today in many a family: was she right to follow her beliefs? Or wrong to cause her family so much unhappiness?

In the original Danish ballad, which I think Arnold must have read, 'Agnete and the Merman', the woman lives eight years with the Merman under the sea until one day she 'hears the clocks of England chime' and asks permisson to go to church. She meets her mother at the church door. 'Where hast thou been?' 'I have been at the bottom of the sea, and have seven sons by the Merman'. The Merman comes to find her, but when he peeps into the church, all the little stone images turn their backs on him.

When I read this, a shiver ran down my spine and I knew I had to tell the story again - but this time I wondered, what would have happened if, instead of the merman, one of Margaret's own daughters came to find her...?

'Forsaken' is available from today as a 'proper' book and as an e-book on Amazon.

Published on November 10, 2011 01:09

November 4, 2011

Mystical Voyages (8) Saint Brendan ...and Caspian again.

As I said last week, for me, aged 10, the journey of King Caspian and his friends to the End of the World (in 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader') seemed completely original, but I now know that C.S. Lewis was borrowing from the traditional Old Irish voyage tales known as immrama. Most involve voyages towards the west, the traditional (European) direction for the Otherworld, where the sun sets into the sea. The immrama hark back to older pre-Christian Celtic voyage tales: but the briefest of readings will show that the stories of Bran or Maeldune are simple entertainment compared with the difficult and cryptic Welsh poem, 'The Spoils of Annwfn'.

It's hard to disentangle cause and effect, belief and tradition. Why was it the practice of many an early Celtic monk to set sail for a remote island on which to live and meditate – like Saint Cuthbert on Inner Farne, who was observed by the community on Lindisfarne to pray all night standing in the sea? Was it only for the solitude and sense of being cut off from the world, or was there a half-hidden memory or tradition that the voyage itself was a holy act which would bring the traveller at last to set bodily foot upon the shore of another world? Alongside the fame of their monasteries, is there a second reason why Lindisfarne off the east coast of Britain, and Iona off the west, are both named 'Holy Island'?

We'll never know, any more than we'll ever be able to answer the question I asked at the beginning of this series on Mystical Voyages, if prehistoric peoples who set out under sail or oar in the earliest times and colonised previously uninhabited lands all over the globe, may have done so partly out of a belief that they were voyaging to the land of spirits, gods, and their ancestors, the blessed dead.

'... do you think,' says Lucy in 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader', 'Aslan's country would be that sort of country – I mean, the sort you could ever sail to?'

Well, who knew? There was only one way to find out.

This Irish in particular, stationed as they are on the western verge of Northern Europe, were in a particularly good position to ask themselves the question, 'What might be out there?' One of the earliest parts of Britain to become Christian, Ireland was sending out missionaries to England and the continent by the 6th century AD: which is also the era of Saint Brendan.

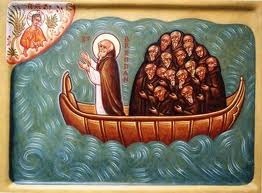

Brendan, whose voyages are recorded in many manuscripts, sets off into the Atlantic Ocean in search of Paradise, the Land of the Blessed, after dreaming of 'a beautiful island with angels serving upon it'. Later, hearing the account of a fellow monk, Mernoke, who claimed to have sailed to the Earthly Paradise, Brendan puts out in a curragh – a hide boat – with twelve companions in search of this country. He spends years wandering the Atlantic between island and island: the island of the 'Comely Hound' (a dog which leads them to a hall with a table spread with food); the Island of Sheep, 'every sheep the size of an ox'; 'The Paradise of Birds', on which the angels who fell with Lucifer, but whose fault was small, live in the form of small birds all rejoicing and singing the matins and the verses of the psalms…

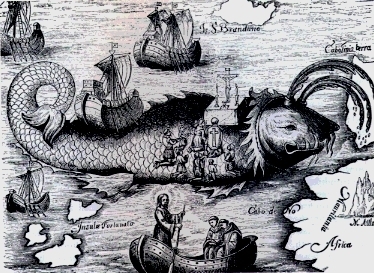

And I particularly like the amiable sea monster, 'Jasconye the Fish', whom the monks mistake for an island and who – after a startled first occasion when he swims off, bearing the fire the monks have lighted upon him still on his back – allows Brendan and his companions to celebrate Easter upon his back as an annual occurrence. Brendan seems to know all about this beast, explaining to his companions that Jasconye is for ever vainly trying to swallow his own tail. Is this an echo of the Northern Midgard Serpent, or simply a bit of early medieval natural science? Here he is anyway, on a map of 1621, obligingly stretched out between the east coast of Africa and 'the Fortunate Isles', with 'St Brendan's Isle' to the north.

There's a clear sea like Maeldune's, full of fishes which come to hear Mass:

So clear that they could see to the bottom, and it was all covered with a great heap of fishes. …And the fishes awoke and started up and came all around the ship in a heap, that they could hardly see the water for fishes. But when the mass was ended each one of them turned himself and swam away, and they saw them no more.

It's lovely, I think, that all nature is included in this Celtic Christianity.

Like Maeldune and his friends, Brendan and his companions also venture close to what seems suspiciously like an erupting volcano:

There came a south wind that drove them on… and at the end of eight days they saw far away in the north a dark country full of stench and of smoke; and as the ship drew near it they heard great blowing and blasting of bellows, and a noise of blows and a noise like thunder, the way they were all afeared and blessed themselves. …And with that there came demons thick about them on every side, with tongs and with fiery hammers, and followed after them till it seemed all the sea to be one fire… and they saw a hill all on fire and like as if walled in with fire, and clouds upon it…

This has to be Iceland, surely? To Brendan of course, it's the borders of hell, and therefore hardly surprising that their next encounter is with poor Judas Iscariot, marooned on a rock.

In the end, after forty days more sailing, and showers of hail, and fog, Brendan and his companions do reach the Land of Promise, the Blessed Land. Oddly enough, although they should be sailing west, the land they see is to the east. (Perhaps this is because east is the direction of Jerusalem: the Earthly Paradise is always located to the east in later medieval maps.) It is:

...clear and lightsome, and the trees full of fruit on every bough… and the air neither hot nor cold but always one way, and the delight that they found there could never be told. Then they came to a river that they could not cross but they could see beyond it the country that had no bounds to its beauty. Then there came to them a young man… and took [Brendan] by the hand and said to him…

'Here is the country you have been in search of, but it is our Lord's will you should go back again and make no delay… And this river you see here is the mering,' he said, 'that divides the worlds, for no man may come to the other side of it while he is in life; [and when he dies] it is then there will be leave to see this country towards the world's end.'

Praising God and laden with fruit of the country, and precious, stones, Brendan returns to Ireland and dies, his whole mind set on the heaven he has already seen.

No wonder C.S. Lewis wrote 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader'. Reading these old immrama, the writer in me longs to snatch up a pen and begin making one of my own. The Christianisation of the old myths in the Voyages of Maeldune and Brendan especially lent themselves to Lewis's Christian fantasy where the Land of the Blessed, Aslan's country, can just be glimpsed over the top of the stationary wave at the world's edge. Lewis tells it in almost the same flat yet awed manner of the immrama – the voice of one simply reporting or recording genuine wonders.

Eastwards – beyond the sun – was a range of mountains. It was so high that either they never saw the top or they forgot it. None of them remembers seeing any sky in that direction. And the mountains must really have been outside the world. For any mountains even a quarter or a twentieth of that height ought to have had ice and snow on them. But these were warm and green and full of forests and waterfalls however high you looked. And suddenly there came a breeze from the east, tossing the top of the wave into foamy shapes and ruffling the smooth water all round them. …It brought a smell and a sound, a musical sound. Edmund and Eustace would never talk about it afterwards. Lucy could only say, 'It would break your heart.'

'Why,' said I, 'was it so sad?'

'Sad! No,' said Lucy.

NB: I am also to be found, this morning, over at The History Girls, talking about girls dressed as boys in historical fiction.

Picture credits:Saint Brendan - image found at the blog LogismoiSaint Brendan and Jasconye the fish - Honorius Philoponus, Nova typis transacta navigatio novi orbis Indiae Occidentalis, 1621

Published on November 04, 2011 01:25

October 28, 2011

Mystical Voyages (7) Bran, Maeldune and ...Prince Caspian?

'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader' was the very last Narnia book which I came to. I'd read the series way out of sequence, beginning with 'The Silver Chair' and gobbling the others in random order one after another as they were given to me for birthday or Christmas presents, or borrowed from the library. So the day I was finally given 'The Dawn Treader' was a memorable one - and not only because my little brother was in hospital recovering from an emergency operation.

My parents knew that a present of the book I'd been longing for would keep me happily tucked up in an armchair for a couple of hours while they went visiting. (I can still almost feel the chair's bristly upholstery against my bare legs as, quite unworried about my poor little brother, I curled up and began to read.)

'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader' swept me away into an open-air world full of light. Light pervades the book: the light of sunrise over the sea, the sunlit quiet passages of the Magician's House, sunbeams penetrating the green waters of the undersea world beneath the ship, the birds that come flying out of the rising sun to the table of the Three Sleepers, the almost painful light of the Silver Sea.

For me, aged 10, the Mystical Voyage of Caspian and his friends to the End of the World - island-hopping as usual - seemed completely original, but I now know that C.S. Lewis was borrowing from the traditional Old Irish voyage tales known as immrama, in which a hero or saint sets out for some kind of Otherworld, stopping at a number of fantastic or miraculous islands along the way. Written in the Christian era, they hark back to older pre-Christian Celtic voyage tales, and may also have been consciously influenced by the classical tales of the Odyssey and Argonautika.

In 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader' the heroic mouse Reepicheep expects to find 'Aslan's own country': and he does, in spite of Lucy's question, 'But do you think… Aslan's country would be that sort of country – I mean, the sort you could ever sail to?'

The answer of the immrama would be: 'Yes! Although you may not always get back.'

The Irish hero Bran's Mystical Voyage begins when, after being lulled to sleep by the magical music of a silver branch with white apple-blossoms, he meets a woman who invites him to seek the wonders of the Emain Ablach or 'Isle of Women', where there is peace and plenty and no one is ever sick or dies. Bran sets out after her with twenty-seven companions and three curraghs – nine men in each boat. After sailing for two days he is encouraged by meeting Mannanan Mac Lir, god of the sea, driving his golden chariot over the sea, who tells Bran he should reach the Isle of Women by sunset. First however they come across an island on which everyone is laughing, and when Bran sends one of his men to investigate, he begins laughing too, and will not return to the boats. (Is this reminiscent of the Odyssey's Land of the Lotus Eaters?) They are forced to leave him there, and sail away.

[image error]

Arriving at the Isle of Women, Bran's boat is drawn into port by a ball of magical thread which the queen tosses to him. Each of the men is paired with a beautiful woman, Bran sharing the bed of the queen, and they remain there happily, unaware of how much time is passing in the real world, until Nechtan son of Collbran becomes homesick and Bran decides to return home. The queen warns against it, and especially against setting foot on land, but Bran insists – but when they sight Ireland, so many years have passed that Bran's name is only an ancient legend, and when Nechtan leaps out of the curragh, he crumbles to dust. (Just the same fate befalls one of Oisin's companions in the legend of Oisin and the fairy woman Niamh.) At the sight, Bran and his companions sail away, never to be seen in Ireland again.

The hero Maeldune also discovers these same two islands which Bran found, but his is a longer voyage and a happier homecoming. Setting out to avenge the killing of his father Ailill, his journey is extended because he fails to follow the advice of a druid to take only seventeen men with him. His three foster brothers swim after the ship, and Maeldune picks them up – but one by one loses them as they visit or pass thirty or so marvellous islands and a variety of other wonders. At last Maeldune receives the advice of a hermit that he will only be able to return home safely once he has forgiven his father's murderer. Maeldune does so and makes a safe landfall.

Along the way Maeldune and his companions see such wonders as the Isle of Ants 'every one of them the size of a foal'; an Island of Birds; an island where demon riders run a giant horse race; an island of a miraculous apple tree whose fruit satisfy the whole crew for 'forty nights'; an island where a mysterious beast turns itself around and around inside its skin (and hurls stones at the voyagers); an island of fiery pigs, an island of a little cat; a 'four-fenced' island divided into quarters for kings, queens, fighting men and young girls respectively; an island where giant smiths strike away on anvils and hurl a huge lump of red-hot iron after the boat (surely a volcanic eruption?) so that 'the whole of the sea boiled up'.

The Very Clear Sea They went on after that till they came to a sea that was like glass, and so clear it was that the gravel and the sand of the sea could be seen through it, and they saw no beasts or monsters at all among the rocks, but only the clean gravel and the grey sand. And through a great part of the day they were going over that sea, and it is very grand it was and beautiful.

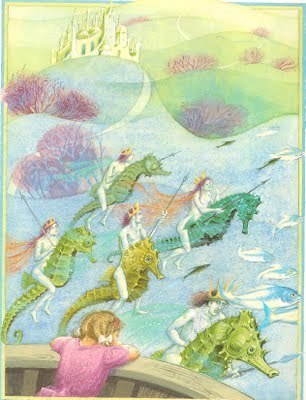

Surely this influenced C.S. Lewis's 'Silver Sea'! ('How beautifully clear the water is' said Lucy to herself as she leaned over the port side early in the afternoon...'I must be seeing the bottom of the sea; fathoms and fathoms down.' Although Lewis soon fills his clear sea with the Sea People and their castle, as shown in this lovely illustration by Pauline Baynes.)

Maeldune soon comes across another marvel: one of my favourites:

The Silver-Meshed Net They went on then till they found a great silver pillar; four sides it had, and the width of each of the sides was two strokes of an oar; and there was not one sod of earth about it, but only the endless ocean; and they could not see what way it was below, and they could not see what way the top of it was because of its height. There was a silver net from the top of it that spread out a long way on every side, and the curragh went under sail through a mesh of that net.

Diuran, one of Maeldune's companions, strikes the net with his spear to obtain a piece:

"Do not destroy the net," said Maeldune, "for we are looking at the work of great men." "It is for the praise of God's name I am doing it," said Diuran, "The way my story will be better believed; and it is to the altar of Ardmacha I will give this mesh of the net if I get back to Ireland." Two ounces and a half now was the weight when it was measured after in Ardmacha. They heard then a voice from the top of the pillar very loud and clear, but they did not know in what strange language it was speaking or what word it said.

I love the way these voyage tales don't try to explain anything: they simply delight in the marvellous inventions (of the poet, or of God) and convey a sense of great wonder at the things men find when they set out upon the illimitable sea.

All quotatations are from Lady Gregory's translations of the voyages in her 'Book of Saints and Wonders'

Picture credits: cover and illustration from 'The Voyage of the Dawn Treader' by Pauline Baynes

Bran meets Manannan Mac Llyr : 'The Voyage of Bran': Tapestry by Terry the Weaver/Terry Dunn, 1996

Published on October 28, 2011 01:01

October 21, 2011

Mystical Voyages (6) Arthur's Voyage to the Underworld

Perhaps you don't tend to think of Arthur as a voyager? Bear with me, and I'll explain.

Perhaps you don't tend to think of Arthur as a voyager? Bear with me, and I'll explain.Some of the earliest mentions of Arthur come from ninth or tenth century Welsh literature – just glancing references, as if to someone already well-known. The earliest of all may be a couple of lines from the poem Y Gododdin, in which another warrior is compared with Arthur:

He fed black ravens on the ramparts of a fortress,

Though he was no Arthur.

This makes sense if the historical Arthur really was a fourth or fifth century British war leader fighting the Saxon invaders: his name perhaps a nickname or pseudonym: 'the Bear', suitable for a fighter who may have wished to maintain an air of terrifying mystery. Whoever the historical Arthur may have been, his name soon became associated with all kinds of older legends connected with supernatural figures from Celtic mythology, and such stories continued to be told about him in all parts of Celtic – that is British – Britain, and in Brittany, the region of France to which many British Celts migrated after the fall of Roman Britain.

Even in Sir Thomas Malory's late 15th century 'Le Morte D'Arthur', with its many courtly French additions and sources, plenty of Welsh and Celtic personages and motifs remain: the most obvious is Merlin himself, and the Lady of the Lake who gives Arthur his sword Excalibur, and then there's Arthur's shadowy relationship with his half-sisters, Morgause the mother of their son Mordred, and Morgan le Fay – Morgan the enchantress, whose name chimes with that of the Morrigan ('great queen' or 'phantom queen'), the Irish Celtic goddess of battle and fertility. At any rate, Morgan is one of the queens who carry the wounded king away to the Isle of Avalon after the battle of Camlann.

And when they were at the water side, even fast by the bank hoved a little barge with many fair ladies in it, and among them all was a queen, and all they had black hoods, and all they wept and shrieked when they saw King Arthur.

…'Comfort thyself,' said the king, '…for in me is no trust for to trust in, for I will into the vale of Avilion to heal me of my grievous wound, and if thou hear never more of me, pray for my soul.'

But ever the queen and ladies shrieked, that it was pity to hear.

The shrieking and keening women, companions of a powerful sorceress, the ship that carries the heroic king away to the island of the dead, the island of apples – seems familiar, doesn't it?

At any rate, there is an earlier – and highly cryptic – account of a voyage by Arthur to the Underworld. It's the marvellous Welsh poem Prieddeu Annwfn, preserved in the single 14th century manuscript of The Book of Taliesin, but dated (cautiously) by internal linguistic evidence to around 900 AD. Here's a link to the poem, with notes. It's an account of a raid led by Arthur, in his ship Prydwen, on Annwn, the Welsh underworld.

Annwn is described by a number of different epithets. No one has a clue if these are simply varying descriptions/manifestations of the same place, or intended for different locations which Arthur and his men encounter along their way. It may not matter much, but in the context of the Mystical Voyages I've been thinking about so far in this series, the latter fits in well with the island-hopping itinerary of heroes in ships gradually approaching their destination through a transformed and numinous sea-scape.

The poem tells how Arthur and his men travel to Caer Sidi, 'The Mound Fortress'; Caer Pedryuan, 'the Four-Peaked Fortress' – also described as Ynis Pybyrdor, 'isle of the strong door'. They travel to Caer Vedwit, 'the Fortress of Mead-Drunkenness', Caer Rigor, 'Fortress of Hardness', Caer Wydyr, 'Glass Fortress', Caer Golud, 'Fortress in the Bowels [of the Earth?]', Caer Vandwy, 'Fortress of God's Peak', and Caer Ochren, 'Enclosed Fortress'. Alan Garner used some of these names in his book Elidor, which references the poem in other ways.

The aim of the expedition was to bring back a cauldron from the lord of Annwn. We're not thinking blackened kitchen pots here: we're thinking inspirational, magical, perhaps sacred items like the 1st century BC Gundestrop cauldron, above. One of the many scenes on its sides depicts a pony-tailed warrior dipping a man into another such cauldron headfirst, probably to restore him to life:

In my personal favourite among Alan Garner's books, 'Elidor', the children bring four treasures out of the Mound of Vandwy. corresponding to the Four Treasures of the Tuatha de Danaan: a spear, a sword, a stone and a bowl: 'a cauldron, with pearls above the rim. And as she walked, light splashed and ran through her fingers like water'. Taken into the workaday world of 1960's Manchester, however, the objects change appearance, and Helen finds she is carrying only 'an old cracked cup, with a beaded pattern moulded on the rim.' Once these treasures have been buried in the garden for safekeeping, however, all kinds of strange disturbances begin to occur, culminating in the eruption of the unicorn Findhorn onto the city streets.

Here's the second stanza of the Prieddeu Annwfn:

I am honoured in praise. Song was heard

In the Four-Peaked Fortress, four times revolving.

My poetry, from the cauldron it was uttered.

By the breath of nine maidens it was kindled.

The cauldron of the chief of Annwfn: what its fashion?

A dark ridge around its border, and pearls.

It does not boil the food of a coward...

And before the door of hell lamps burned.

And when we went with Arthur in his splendid labour,

Except seven, none rose up from Caer Vedwit.

Most of the eight stanzas end with a variation on the recurrent line: 'Except seven, none returned': by ordinary standards the expedition appears to have been disastrous, but this is no ordinary poem. Fateful and gloomy, mysterious as Arthur himself, all we can gather from it is some sense of a venture, by ship, by sea, into the Otherworld, and - perhaps – a description of a mound or island where a youth, Gweir, is imprisoned, lapped with a heavy blue-grey chain. Of a four-peaked fortress with a strong door, guarding a cauldron full of the magical life-giving mead of poetry, warmed by the breath of 'nine maidens'. And of a fortress of glass with six thousand men lining the walls ('it was difficult to speak with their sentinel').

In the medieval story of Culhwch and Olwen in the Mabinogion, Arthur sails to Ireland in his ship Prydwen to steal the cauldron of Diwwnach Wyddel: not just any old cauldron either, for it's also listed in 'The Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain' as the cauldron of Dyrnwich the Giant, which will not boil the food of a coward. Clearly the same cauldron as that which Arthur went to find in Annwn, and doubtless the same also as the Irish Cauldron of the Dagda, from which 'no man ever went away unsatisfied'.

How old is this legend of magical, life-giving cauldrons? As old as Medea's? Is hers' the ultimate origin of the witches' cauldron that we find in 'Macbeth'? Who knows? Lastly, also in the Mabinogion, the Welsh hero Bran is the keeper of yet another magical cauldron which restores the dead to life. And he too is the subject of a Mystical Voyage. More about him and some other Celtic voyagers next week!

Picture credits:

The Death of Arthur by James Archer, 1823-1902

The Death of Arthur by Katharine Cameron

The Gundestrop Cauldron

Detail from the Gundestrop Cauldron

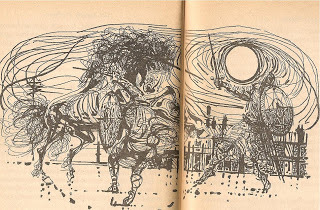

Illustration by Charles Keeping from 'Elidor' by Alan Garner

Published on October 21, 2011 08:00