Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 44

July 1, 2011

Fairytale Reflections (25) "Weird Tales From Northern Seas"

I think it's time for some fairytale reflections from you, you lovely and talented and sensitive people who come and read this blog and sometimes comment! So I'm putting up an entire story from one of the wonderful 19th century collectors and retellers of folktales whom I've met on the road through fairyland: Jonas Lie, a celebrated Norwegian author.

I think it's time for some fairytale reflections from you, you lovely and talented and sensitive people who come and read this blog and sometimes comment! So I'm putting up an entire story from one of the wonderful 19th century collectors and retellers of folktales whom I've met on the road through fairyland: Jonas Lie, a celebrated Norwegian author.Here's a little bit of background: he was a contemporary of Ibsen, born 1833 at Hvokksund, Norway, not far from Oslo; but he spent much of his childhood at Tromsø, inside the Arctic Circle. He was sent to naval college, but poor eyesight made him unsuited for a life at sea, so he became a lawyer and began to write and publish poems and novels which reflected Norwegian life, folklore and nationalism.

I confess I haven't read any of Lie's novels, as most of them don't seem to have been translated into English. But I do have a collection of his reworkings of Norwegian and Finnish legends about the sea. It's called 'Weird Tales From Northern Seas'. My edition was published in English in 1893 and consists of eleven short stories cherry-picked from a volume called 'Trold'- 'Trolls' - and another called 'Fortaellinger og Skildringer ', which means something like 'Tales and Depictions, or 'Stories and Portrayals' (translations courtesy of the Bookwitch). How I wish I could read the others.

I do not know how close these stories are to original legends, although some strike me as very close in spirit. Even in translation I find them powerful and beautiful, marvellously told. I was reading this collection while writing the second of my 'Troll' books: one of his stories, 'The Fisherman and the Draug', was part of the inspiration for the malevolent ghosts which haunt the fisherman Bjørn in my own book. The one I want to share today is called 'The Cormorants of Andvær' – an eldritch, beautiful story. I'm not going to say any more about it. Here is the story itself, with no more than a couple of minor cuts. When you've read it, let me have your own fairytale reflections. Please tell me what you think of it, how it affects you. I am sure it will affect you. It's such a strange tale…

The Cormorants of Andvær

Outside Andvær lies an island, the haunt of wild birds, which no man can land upon, be the sea never so quiet; the sea swell girds it round about with sucking whirlpools and dashing breakers.

Outside Andvær lies an island, the haunt of wild birds, which no man can land upon, be the sea never so quiet; the sea swell girds it round about with sucking whirlpools and dashing breakers.On fine summer mornings something sparkles there through the sea-foam like a large gold ring; and, time out of mind, folks have fancied there was a treasure there left by some pirates of old.

At sunset, sometimes, there looms forth from thence a vessel with a castle astern, and a glimpse is caught now and then of an old-fashioned galley. There it lies as if in a tempest, and carves its way along through heavy white rollers.

Along the rocks sit the cormorants in a long black row, in wait for dog-fish.

But there was a time when one knew the exact number of these birds. There was never more nor less of them than twelve, while upon a stone, out in the sea mist, sat the thirteenth, but it was only visible when it rose and flew right over the island.

The only persons who live near the Vær at winter time, long after the fishing season was over, was a woman and a slip of a girl. Their business was to guard the scaffolding poles for drying fish against the birds of prey, who had such a villainous trick of hacking at the drying-ropes.

The young girl had thick coal-black hair, and a pair of eyes that peeped at folk so oddly. One might almost have said that she was like the cormorants outside there, and she had never seen much else all her life. Nobody knew who her father was.

Thus they lived till the girl had grown up.

It was found that, in the summer time, when the fishermen went out to the Vær to fetch away the dried fish, that the young fellows began underbidding each other, so as to be selected for that special errand.

Some gave up their share of the profits, and others their wages, and there was a general complaint in all the villages round about that on such occasions no end of betrothals were broken off.

But the cause of it all was the girl out yonder with the odd eyes.

… The first winter a lad wooed her who had both house and warehouse of his own.

"If you come again in the summer time, and give me the right gold ring I will be wedded by, something may come of it," said she.

And sure enough, in the summer time the lad was there again.

He had a lot of fish to fetch away, and she might have had a gold ring as heavy and as bonnie as her heart could wish for.

"The ring I must have lies beneath the wreckage, in the iron chest, over at the island yonder," said she; "that is, if you love me enough to dare fetch it."

But then the lad grew pale.

He saw the sea-bore rise and fall out there like a white wall of foam on the bright summer day, and on the island sat the cormorants sleeping in the sunshine.

"Dearly do I love thee," said he, "but such a quest as that would mean my burial, not my bridal."

The same instant the thirteenth cormorant rose from his stone in the misty foam and flew right over the island.

Next winter the steersman of a yacht came a wooing. For two years he had gone about and hugged his misery for her sake, and he got the same answer.

"If you come again in the summer time and give me the right gold ring I will be wedded with, something may come of it."

Out to the Vær he came again on Midsummer Day.

But when he heard where the gold ring lay, he sat and wept the whole day till evening, when the sun began to dance north-westward into the sea.

Then the thirteenth cormorant arose, and flew right over the island.

There was nasty weather during the third winter. There were manifold wrecks, and on the keel of a boat, which came driving ashore, hung an exhausted young lad by his knife-belt.

But they couldn't get the life back into him, roll and rub him about in the boathouse as they might. Then the girl came in. "'Tis my bridegroom!" said she. And she laid him in her bosom, and sat with him the whole night through, and put warmth into his heart.

And when the morning came, his heart beat. "Methought I lay betwixt the wings of a cormorant, and leaned my head against its downy breast," said he.

The lad was ruddy and handsome, with curly hair, and he couldn't take his eyes away from the girl.

He took work upon the Vær. But off he must be, gadding and chatting with her, be it never so early and never so late. So it fared with him as it had fared with the others.

It seemed to him that he could not live without her, and on the day when he was bound to depart, he wooed her.

"Thee I will not fool," said she. "Thou hast lain on my breast, and I would give my life to save thee from sorrow. Thou shalt have me if thou wilt place the betrothal ring upon my finger; but longer than the day lasts thou canst not keep me. And now I will wait, and long after thee with a horrible longing, till the summer comes."

On Midsummer Day the youth came thither in his boat all alone.

Then she told him of the ring that he must fetch for her from among the skerries.

"If thou hast taken me off the keel of a boat, thou mayest cast me forth yonder again," said the lad. "Live without thee I cannot."

But as he laid hold of the oars in order to row out, she stepped into the boat with him and sat in the stern. Wondrous fair was she!

It was beautiful summer weather, and there was a swell upon the sea: wave followed upon wave in long bright rollers.

The lad sat there, lost in the sight of her, and he rowed and rowed till the insucking breakers roared and thundered among the skerries; the groundswell was strong, and the frothing foam spurted up as high as towers.

"If thy life is dear to thee, turn back now," said she.

"Thou art dearer to me than life itself," he made answer. But just as it seemed to the lad as if the prow were going under and the jaws of death were gaping wide before him, it grew all at once as still as a calm, and the boat could run ashore as if there was never a billow there.

On the island lay a rusty old ship's anchor half out of the sea.

"In the iron chest which lies beneath the anchor is my dowry," said she. "Carry it up into thy boat and put the ring which thou seest on my finger. With this thou dost make me thy bride. So now I am thine till the sun dances north-westwards into the sea."

It was a gold ring with a red stone in it, and he put it on her finger and kissed her.

In a cleft on the skerry was a patch of green grass. There they sat them down, and they were ministered to in wondrous wise, how he knew not nor cared to know, so great was his joy.

"Midsummer Day is beauteous," said she, "and I am young and thou art my bridegroom. And now we'll to our bridal bed."

So bonnie was she that he could not contain himself for love.

But when night drew nigh, and the sun began to dance out into the sea, she kissed him and shed tears.

"Beauteous is the summer day," said she, "and still more beauteous is the summer evening; but now the dusk cometh."

And all at once it seemed to him as if she were becoming older and older and fading right away.

When the sun went below the sea-margin there lay before him on the skerry some mouldering linen rages and nought else.

Calm was the sea, and in the clear Midsummer night there flew twelve cormorants out over the sea.

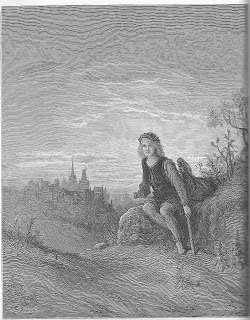

Picture credits: Engraving of Jonas Lie by H.P. Hansen

'The Cormorants of Andvær' by Laurence Housman

Published on July 01, 2011 01:42

June 24, 2011

Fairytale Reflections (24) Nick Green

So here is a photo of my friend Nick Green, looking like a super-cool, turbo-charged, kick-ass dude, pretty much exactly the way kids imagine every [male] author ought to look. I mean, your average ten-year old wouldn't feel like an idiot reading one of his books, would they?

So here is a photo of my friend Nick Green, looking like a super-cool, turbo-charged, kick-ass dude, pretty much exactly the way kids imagine every [male] author ought to look. I mean, your average ten-year old wouldn't feel like an idiot reading one of his books, would they? It has been very difficult persuading Nick to part with enough information for me to make a reasonable go of writing this introduction. I suspect him of being the kind of guy who refuses to part with information even when tied to the chair in the underground room, with the water rising around him and the candle slowly burning through the cord holding the anvil suspended over his head. Out of sheer bloody-mindedness, no doubt.

At any rate, after applying a good deal of pressure I managed to extract only this: Nick is the second oldest and second tallest of four brothers, and the only one who isn't ginger. It was while working for a children's book club that he made the rash decision to start writing books as well as selling them. He read English at Edinburgh University, and now lives in Hertford with his wife and an itinerant population of cats.

Fortunately, I have other sources of information. I first heard of Nick's debut novel 'The Cat Kin' because it was news. Nick self-published the book – yes, you heard – believing in its worth: and he was absolutely right. After it was reviewed in The Times by Amanda Craig, who called it 'a gripping adventure', it was bought by Faber & Faber. Nick was writing the sequel, there was going to be a trilogy, and everyone seemed to be talking about it. What a brilliant success story! So of course, I whizzed out and bought a copy… and was entranced.

It's a classic children's adventure story with a fantasy/sci-fi twist: Two inner-city kids, Ben and Tiffany, each living tough lives, join an after-school gym class run by a strange woman called Mrs Powell. And it turns out that what she teaches is the lost Ancient Egyptian art of 'pashki' – moving and sensing like a cat. Soon Ben, Tiffany and the rest of their class are leaping over London's rooftops, slipping near-invisibly through the streets – and about to need all nine of their new lives as they discover the very dark deeds taking place in the old factory with the chimney like a wizard's tower, visible from Ben's apartment block… The plot is exciting, the writing is fresh, funny and perceptive. Here, the children learn to climb trees like cats, up on top of Primrose Hill…

Perched over the dell, [Tiffany] parted the leaves. The city of London looked near enough to touch. Office blocks floated in the exhaust haze like fairy towers, the wheel of the London Eye no more than a charm bracelet dropped among them.

… A tree bearing bobbly green fruits fanned its branches like the spokes of an umbrella. She bounded from spoke to spoke, catapulting herself off the last branch. In a blink she was inside a cathedral of a horse-chestnut, emerald light glimmering through leafy windows, its mighty boughs straining higher like a spire towards the sun. Up she dashed through the rafters as if ascending a spiral staircase, leaping out through a portal in the leaves.

But there's a dark side to the book, too. Tiffany is struggling with the reality of her brother's illness. What if illegal experiments could produce a drug to cure him? Ben and his mother are under threat, their apartment wrecked by thuggish developers who want them to move out. And both children have to learn responsibility for their new, sometimes frightening powers:

The cat-self he had awakened, his Mau body, had reflexes too fast for him to control. If he was hit, he would hit back, no matter who got hurt. … He shrank inside, just as he had when he was five and had accidentally set the waste paper basket on fire, thinking the flat, the whole world, would burn down. … He hadn't meant this to happen. What had he done?

And there turned out to be a dark side to the success story of Nick's publication, too. Despite many good reviews, despite the fact that by this time Nick had written the sequel, Faber & Faber decided not, after all, to go ahead with publishing this second volume, 'Cat's Paw'.

This sort of thing is not uncommon these days, and it's a crushing blow on a scale that perhaps only another author can fully understand. Bloodied but unbowed, Nick decided that this left him with only one thing to do – self-publish 'Cat's Paw', and be damned to 'em.

Which he did. And lo! in the best of fairytale traditions courage and tenacity, allied to faith and talent, paid off. 'The Cat Kin' was taken by valiant 'Strident Publishing' and republished with a brand-new cover. Strident publishes the second book of the trilogy,'Cat's Paw', in August, and Nick is busy writing the third. And contemplating a new trilogy, 'Firebird'.

With all that going on, I'm grateful to Nick for taking the time to write this Fairytale Reflection – and not at all surprised, really, that he's chosen that tale of aspiration, fortitude, hard work …and cats:

Dick Whittington and His Cat: (or The Magic of Cats)

Turn again, Whittington, Lord Mayor of London!

Turn again, Whittington, thrice Mayor of London!

Is 'Dick Whittington and his Cat' really a fairytale? I'm going to call it one. Even though there is no actual magic (but see below), most of the ingredients are there: the poor and naive youth, the quest, the hardship, and at least a semi-supernatural element in the prophecy of the Bow Bells, calling the young Whittington back from Highgate Hill. I would argue that 'Dick Whittington' is not just a fairytale, but a particularly interesting one, being the only one (to my knowledge) that features a real person.

The historical Richard Whittington, of course, was Lord Mayor a total of four times (but legend ignores that as it doesn't scan). Also, he was never particularly poor, and no-one knows if he really kept a cat. According to my diligent academic research (Wikipedia), the story's origins lie further back, in a Persian folktale of a youth and his cat, onto which the legend of Whittington was later grafted. We can only guess the reason for this, but by all accounts Richard W was an all-round good egg and probably deserved it.

DW and C (as I shall write henceforth) is a simple enough yarn. A young lad comes to London seeking his fortune, following a rumour that the streets are paved with gold. Of course, they aren't, and he ends up as a scullery boy. But his master is a merchant, and offers a place on his ship for anything that Dick might want to sell. All Dick has is his beloved cat, so reluctantly he sends that. Then, despairing of his fortune and missing his cat, Dick runs away, only to be checked on the edge of the city by the calling of the Bow Bells, who seem to be foretelling his future. He will become Lord Mayor of London, not once, but three times. Dick turns back, and arrives at his master's house to astonishing news. The King of Barbary (whose kingdom is plagued by rats and mice) has bought his cat for a huge sum of gold. Dick's fortune in made, and his destiny set in motion.

It's a heartwarming story, but what makes it a fairytale? Someone being elected to high office three times isn't a fairytale – that's Margaret Thatcher. Even the prophetic bells aren't really enough to elevate this story to the level of fairytale. There has to be another element that makes it so enduring.

Let's face it. It's the cat.

Think of the story of DW and C, and it's always the same image: the youth treading the roads with his belongings in a sack on a stick, and a cat trotting faithfully beside him. If that animal were a dog, you'd have no story. 'Dog follows human' is not news. 'Cat walks with human' is the stuff of legend (unless your name is Jackie Morris). And the cat is what people remember. I mentioned before that no cats are recorded in the life of the historical Richard Whittington – and yet the creature still keeps popping up in tantalising glimpses, much as you'd expect a cat to do. In his will, Whittington ordered the rebuilding of Newgate Prison, and over one of the gates you could find the carving of a cat. Later, in 1572, Whittington's heirs presented a chariot with a carved cat to the Merchants' Guild. And in front of the Whittington Hospital, on Highgate Hill where Dick was said to have turned around, the cat keeps watch in the form of a statue. Despite all his philanthropy and good works – not to mention his real, provable existence – Whittington's perhaps-mythical cat has effortlessly outlasted him. It's not fair, is it?

In the story, it's the cat that fills the role normally occupied in a fairytale by magic. It manages this even though it does nothing extraordinary – it doesn't talk or dress up like the animal in Puss In Boots, it just goes around being a very good mouser and Dick Whittington's dearest friend. In short, it does what any cat does. Because what a cat does, is magic.

This idea is at the heart of my own series of books, 'The Cat Kin'. In this, a group of London children join a class where they learn to move, see, hear and fight like cats. The art of 'pashki' is entirely my invention, but such is the universal appeal and mystery of cats that many readers ask if pashki is in fact real, or based in reality. Indeed, if you search the web, you can find claims that it is (and I didn't put them there). Like Whittington's cat, pashki seems to want to have a life of its own. Cats, for whatever reason, continue to exert their mystical fascination over us human beings.

One final reason why I love the story of Dick Whittington and his Cat, is that it's a great parable for an aspiring writer. Dick follows a bright dream initially, only to be bitterly disappointed, giving up and turning away from it. And then, when all seems lost, he is called back to his struggle with the promise of a great reward – a threefold reward. And since I'm just now finishing off the third book in the Cat Kin trilogy, you could say that this ending rings a bell for me too.

Picture credits:

Nick Green

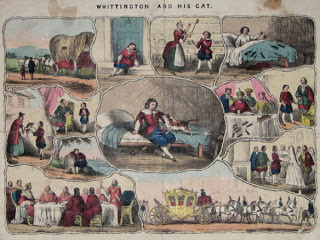

Dick Whittington on Highgate Hill: by Gustave Doré: 'London, A Pilgrimage'

The Dick Whittington Stone at Highgate

Whittington and His Cat: mid 19th century print, courtesy of SpitalfieldsLife (where you can find the story of Blackie, the last cat of Spitalfields Market).

Published on June 24, 2011 00:50

June 17, 2011

Fairytale Reflections (23) Gwyneth Jones

As a long-term writer of brilliant adult science fiction, Gwyneth Jones is a force to be reckoned with. 'Bold As Love', which won the Arthur C Clarke Award in 2002 (and was nominated for many others) is the first of a series of five books about a near-future Britain where society is in meltdown. There's a violent environmental movement, an Islamic uprising in the north, a subtle but nasty dose of black magic, and a complex relationship between the main characters – three charismatic, damaged and idealistic young rock stars who become the country's reluctant saviours and leaders of a new government, the 'Rock and Roll Reich'. The books are rich in wars, rock festivals, romance, horror, and a deeply felt version of the British landscape, history and myth. Do read them - if you haven't already!

As a long-term writer of brilliant adult science fiction, Gwyneth Jones is a force to be reckoned with. 'Bold As Love', which won the Arthur C Clarke Award in 2002 (and was nominated for many others) is the first of a series of five books about a near-future Britain where society is in meltdown. There's a violent environmental movement, an Islamic uprising in the north, a subtle but nasty dose of black magic, and a complex relationship between the main characters – three charismatic, damaged and idealistic young rock stars who become the country's reluctant saviours and leaders of a new government, the 'Rock and Roll Reich'. The books are rich in wars, rock festivals, romance, horror, and a deeply felt version of the British landscape, history and myth. Do read them - if you haven't already!However, Gwyneth also writes YA fiction under the name Ann Halam. The earliest of her books I ever read was 'Ally Ally Aster', Allen & Unwin, 1981, in which a couple of conniving villains manage to imprison an ice spirit for their own nefarious ends. (As you might guess, things turn out badly for them.) After that I was hooked and have read nearly everything she's written since: science fiction, horror and fantasy. I've already talked on this blog about 'King Death's Garden', a ghost story which is effortlessly funny as well as intensely frightening, as the self-pitying hero Maurice (characterised by the girl he fancies as a filthy, leprous little brute) sets out to discover the true secret of the large Victorian cemetery beside his great-aunt's house. Then there's 'The N.I.M.R.O.D. Conspiracy', a blend of horror and thriller, in which a boy, haunted by the little sister who drowned while in his care, begins to think – with reason – that she may still be alive. And 'Siberia', a haunting and beautiful book about a girl who journeys across a frozen and repressive land carrying a 'nut' full of mysterious secret seeds:

I knew the nutshell was magic. There was a thin dark line around the middle of it. Mama ran her fingertips around there: the nut came open in two halves and inside, snuggled in a nest of silky stuff, I saw tiny, furry living creatures. They looked at me, with eyes no bigger than pin-heads.

…They were called Lindquists, another strange word I must remember. They would live, snuggled up together, and they would die, and curl up in their dishes again and turn into cocoons (I knew furry animals didn't do that, caterpillars turning into butterflies did that, but this was magic). Then you had to crumble the cocoons into powder, and put the powder into a new seed tube, with the right-coloured cap.

"Once there were Lindquists for all eight orders," said Mama. "The two missing ones are Cetacea and Pinnipedia. But the marine mammals were lost."

Her most recent book for young adults, 'Snakehead', Orion 2007, is a marvellous retelling of the legend of Perseus, written with wit, liveliness and passion. And here is Gywneth herself to talk about:

The Princess As Role Model

I've always been attracted to fairytales. I knew I was a storyteller long before I knew I'd be a writer: I took on my father's mantle, and told epic bedtime stories to my brother and sister, at an early age, and my father's stories (also epic, endless episodes from the same saga, about the same characters) were all based on a traditional tale, the one about a girl who finds out that she once had seven brothers, who were banished and turned into crows when she was born. It has many variants, but from internal evidence the original must be the Moroccan one (The Girl Who Banished Seven). Naturally, she sets off to find them and rescue them from the enchantment. That's typical of a fairytale princess (she's one of those who becomes a princess by marriage, but it's all the same to me). They do the right thing. They stand up to evil step-mothers, and no task is impossible...

As a child I was small, podgy, clumsy and, worst of all, I was obviously going pass that dreaded public exam called "The 11 Plus", and go to Grammar School. I felt for the princesses in the fairytales. First they tell you you've been awarded fairy gifts (which you never asked for) and then wham, you're plunged into bizarre vindictive hardship. Your mother dies, you end up sleeping in the ashes, washing bloody linen in a cave, knitting nettle shirts on a bonfire, wearing out your iron boots over razor sharp glass mountains. But I admired them too, and found them a tremendous comfort. They were so tough, so resourceful, and so decent. When everyone (not least the other little girls I knew) was telling me you are second-rate, they made me proud to be a girl. As I nursed my little bullied self home from school, by the most unobtrusive route, I thought about Cinderella. Elle s'estoit bien, says Perrault, and I wanted to be that person. To behave well, to stand up and be proud. (I knew it worked, too. The best way to frustrate a bully is to stay cheerful; be nice. It drives them absolutely nuts.)

When I was a child I responded to the bizarre adventures, the cheerful feats of endurance, the unstoppable can-do attitude of those privileged, yet beleaguered, young women. As I grew up the stories grew with me. I realised that the princess complex is a trap, it's pure social propaganda. But I still loved the princesses, and the princes, themselves, and honoured their traditions when I started writing my own fantasy stories (published, long afterwards, as Seven Tales And A Fable). I honoured the stories, and I still do. I saw that they were more than lessons in docility, more than comforting, greedy daydreams. They were beautiful, ancient vessels, full of buried treasure. It was a very old, profound and lovely princess-story, re-written as a fantasy novel by a modern writer —'Till We Have Faces', C.S.Lewis—, that inspired me to write 'Snakehead', my own re-imagining of the story of Perseus and Andromeda.

'Till We Have Faces' is based on Eros and Psyche, one of the greatest of the Greek myths, and yet the story is familiar from many fairytales. A princess finds her prince and loses him. She fights her way back to his side by overcoming the fiendish magical challenges devised by a spiteful royal mother-in-law—

Seven long years I served for thee

The glassy hill I clamb for thee

The bluidy shirt I wrang for thee

Wilt thou not wake and turn to me?

(The Black Bull Of Norroway)

Perseus and Andromeda is another myth, perhaps the greatest of them all, with instant popular appeal. The hero-tale of Perseus fits in anywhere! There's this kid, you see, brought up by his single mother, goes to High School or whatever, and then one day some supernatural beings come along. They tell him his father was a Greek God, they give him a magic sword and flying sandals, they send him off to kill a terrifying monster. He's tall, strong and handsome! He has superpowers! He's a teen with a mission! Oh, hey, and there's a flying horse—

Unexpectedly, things get even better if you're looking to write a novel rather than a comic book. The story of Perseus has complexity, it has texture. There's the grim soap-opera of his parentage —why Danae of the shower of gold was locked up; how Zeus, the ruthless, randy chief of the Olympians, just couldn't resist a challenge; how Perseus's charming grandfather put both mother and child in a box and had them thrown into the sea. There's the unconventional little family group on the island of Seriphos: Danae and her son, washed up on the shore, living under the protection of Dictys the fisherman. Whose brother is the island's tyrant king. Imagine this boy, knowing he's different, but with nothing to show for it, no rank, no riches. Imagine him finding out that his biological father (he's not impressed by divine status, of course; he's family himself) is a ruthless Mr Big who raped his mother. He knows he's been protected at least once from certain death. He must be wondering, as he grows up, what his selfish brute of a Divine Father saved him for. Nothing good, you can bet... And then there's Dictys. Imagine the boy's relationship with the fisherman, who has brought him up, and never (not in any of the accounts) put a disrespectful move on Danae. He's been a true father. Dictys seems to be a man of peace, since he's able to live and let live, with his wicked brother on the throne. How is his adopted son really going to feel, when the Messenger of the Gods, and the Goddess Athini waylay him on the road, and tell him he has to chop off the Gorgon's Head? This Gorgon who was once a woman, too beautiful for her own good, like Danae. Who was turned into a monster, to punish her for having been raped...

So it goes on, a wonderful story: the work of many hands, over thousands of years, and yet still alive, still growing, still inviting new storytellers to weave new patterns into the web. There's only one weak point, and that's the traditional centrepiece, where our hero finds his true princess, and has to win her by beating a string of awful vindictive challenges, thrown down by the malign Gods—

It's weak because it doesn't happen.

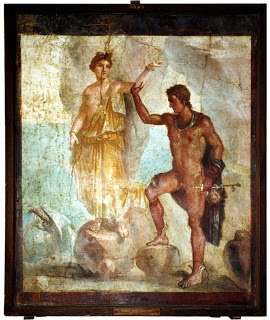

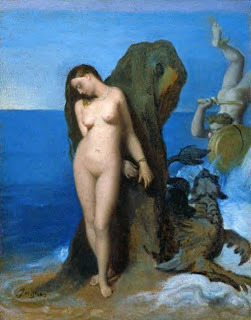

Andromeda isn't a character. She's not even as much of a character as the prince in 'The Black Bull Of Norroway'. She's a name, and a predicament. Perseus doesn't struggle to win her. He just passes by, on the way home from his questing work, swinging the Gorgon's Head by the hair (not very safe! But that's how it looks in all the pictures), and picks up a half-naked princess; like a pizza or a sandwich.

Andromeda isn't a character. She's not even as much of a character as the prince in 'The Black Bull Of Norroway'. She's a name, and a predicament. Perseus doesn't struggle to win her. He just passes by, on the way home from his questing work, swinging the Gorgon's Head by the hair (not very safe! But that's how it looks in all the pictures), and picks up a half-naked princess; like a pizza or a sandwich. In my opinion, this just won't do!

In 'Till We Have Faces' C.S.Lewis keeps his distance from the two principals, who represent, without much disguise, the human soul and the God of Love. His characters are the lesser figures. His protagonist is one of Psyche's jealous sisters —a woman who barely exists in the original narrative. In 'Snakehead', I took the liberty of inventing the character of Andromeda, a weaver and a scholar (her name means Ruler of Men, or else Thinker) and switched things around so that she and Perseus have some previous history, before Andromeda is chained to the rock; before Perseus wanders along to slay the dragon. It just makes more sense, if Perseus knows he's coming to the rescue of a princess; if he intends to claim her hand in marriage. It makes more sense to me personally, too. A generation ago, great writers and editors like Jane Yolen, Ellen Datlow reclaimed the traditional heritage: dismissing soft-focus, Disneyfied Snow White and Cinderella, rediscovering grim truths and quick-witted, resourceful heroines. That's fine, that's excellent work. But what I've wanted to do is to reclaim the relationships. To bring the prince and the princess together, instead of sending them off on segregated initiation trials. To let them meet as human beings, as friends, and fight side by side.

The story on record says Andromeda had to be sacrificed to punish her mother, queen Cassiopeia —who had boasted that her daughter was more lovely than a sea-nymph, and thus offended Poseidon, the God of Ocean and of Earthquakes. I don't believe it. Child sacrifice was absolutely rife, around the shores of the Ancient Mediterranean. (Take a closer look at your Old Testament, if you don't belive me). I'll bet you anything it wasn't a one-off occasion. I bet there was a lottery, and the children of the rich were usually spared, but then the queen's political opponents decided Andromeda's number was up. A powerful woman like Cassiopeia could have been an annoying relic of the old ways, in the days of the original story —when the Mediterranean World was leaving female-ordered civilisation behind, and patriarchal tribal rule was taking over.What would a princess do, if she found out she'd been drafted? Run for it, of course. And then what would she do, if she was a real princess; and knew some other poor girl would have to die in her place? She'd run back, of course. No matter who tried to stop her, no matter if she'd fallen in love.

Leaving Perseus with his repellent, murderous quest: a terrible choice, and just the inklings of a desperate plan—

The story of Perseus and Andromeda is the story of the founders of Homer's Mycenae: well built Mycenae, rich in gold... way back in the Bronze Age. And from Mycenae, the baton was handed on to Athens, the cradle of western civilisation; making them a fairly significant couple, in the scheme of human history. (And by the way, Perseus and Andromeda did live happily ever after, which makes them unique among pairs of lovers featured in the Greek Myths) But is that all? The deeper I looked into the history of the Medusa, terrible to look upon, snakehaired monster, and into the history of the mighty Goddess Athini, whose name means Mind, the more they seemed to reflect each other. As if Medusa and Mind were the two faces of one truth—

Did I catch a glimpse of the original, brilliant storyteller, telling me something timeless and profound? About that mysterious birthright gift, first freely given and then painfully earned, that lies at the heart of fairytale? Maybe, maybe not. I don't know. I'm just a storyteller, seeing pictures in the fire. Pictures that, now as then, sometimes seem playful, sometimes serious, and sometimes seem to tell me eternal things.

Here's some writing on fairytales, and some free stories:

And here's the Snakehead page

Photo credits:

Gwyneth Jones

Perseus and Andromeda: a wall painting from Pompei, The National Museum of Naples.

Perseus and Andromeda: by Ingres

Published on June 17, 2011 00:13

June 10, 2011

Fairytale Reflections (22) Terri Windling

Now here is the story of how I had the happy chance to meet Terri Windling. My younger daughter is best friends with her stepdaughter, and occasionally, as young people do, she would toss out a small scrap of information about her friend's family:

Now here is the story of how I had the happy chance to meet Terri Windling. My younger daughter is best friends with her stepdaughter, and occasionally, as young people do, she would toss out a small scrap of information about her friend's family:"Her step-mum writes."

"Does she? What sort of thing does she write?"

"I don't really know, but she's very nice."

So it took me ages to get around to asking more questions. (Note to self: always ask more questions!) Presumably a similar rivulet of information was flowing in the other direction too. I live in Oxfordshire, and Terri in Devon when she's not in New York or Arizona, so it wasn't as though we were constantly running into one another as one does when collecting or dropping off one's offspring at sleepovers, parties, school, etc. Eventually however, the penny dropped and I discovered who I'd been missing out on. As I suppose most of you do not need me to tell you, Terri Windling is an American writer, artist and editor of fantasy for children and adults. She has won more awards than you can shake a stick at: you can look it all up on Wikipedia, here.

I didn't know all that much about American fantasy writing before I met Terri, but she's the best possible person to provide guidance, being not only most generous with praise and recommendations of other writers' work, but also an excellent judge. A whole world of brilliant fantasy opens up from a reading of some of the many anthologies Terri has edited, such as 'The Armless Maiden and other Tales for Childhood's Survivors', a collection of powerful stories about 'the darker passages of childhood'; and, with Ellen Datlow, many wonderful myth and fairytale-inspired anthologies for young adults such as 'The Green Man' and 'The Faery Reel'. I'm the happy possessor this week of two recent anthologies: 'Teeth' - a book of very different vampire tales by luminaries such as Holly Black and Neil Gaiman, edited by Terri and Ellen Datlow - and 'Welcome to Bordertown', (a city on the edge of our world and faerie) edited by Holly Black and Ellen Kushner, with an introduction by Terri. I can't wait to read them both.

Terri's own fiction includes 'The Wood Wife', which won the Mythopoeic Award for Novel of the Year in 1996, a fantasy novel in which faeries and shape-changing nature-spirits (Owl-Boy, Crow, the Rabbit-Girl, the Spine-Witch) walk the Arizona desert and interact with mortals. Many of Terri's own paintings evoke such characters. As well as writing several children's books and numerous short stories, she is also the founder of the Endicott Studio, which is devoted to the discussion and practice of mythic fiction and arts. It could all be a bit overwhelming, except that she isn't at all an overwhelming person – and it helps that we both own young and boisterous dogs who dissolve into joyful hysteria whenever they meet...

Re-reading, as I did before writing this introduction, some of Terri's stories and essays in 'The Armless Maiden', I am struck by her passionate understanding of the fragility and desperate strength of childhood in adversity. My own childhood was happy. I trusted adults. I used to trot down the lane to visit an old lady called Mrs Oliver, who had a collection of little porcelain houses with outsize porcelain flowers on the roofs. She would give me orange squash and a biscuit, and I would sit on her chair and swing my legs and chatter. She always asked about my parents and my brothers and sister, and would exclaim aloud, "Oh, yours is such a happy family!" in a way which – aged six or seven – I found silly, sentimental: of course we were happy: wasn't everyone? I now realise her exclamations were most probably related to the fact that my mother was my father's second wife – his first having died – and so my older brother and sister were her step-children.

Step-mothers get a bad deal in fairytales, as my mother herself has often ruefully remarked. In fact, in many stories – Hansel and Gretel is an example – it was the children's own true mother and father who abandoned them in the woods. Some 19th and 20th century collectors and editors found this too hard to stomach, and changed the mother figure to a stepmother as some way of softening the brutality of the stories. We would all prefer to believe that no true mother would abuse her child. But the fairytales were more realistic than the editors. As Alison Lurie wrote, in 'Don't Tell the Grown-ups': "The fairytales had been right all along – the world was full of hostile, stupid giants and perilous castles and people who abandoned their children in the nearest forest."

And as Terri Windling has said in her afterword to The Armless Maiden,'Surviving Childhood', there is a need for stories 'for the Hansels and Gretels still imprisoned in the witch's cottage. And for the lucky ones, the brave ones, who have found their way out of that terrible wood.'

On Fairytales

I've been asked to reflect on fairy tales – which, as it happens, is something that I've been doing my entire professional life: thirty years of championing re-told fairy tales as a literary art form. I've reflected so long, and written so much, on the fairy tales that have meant the most to me that my difficulty now is in finding a new approach, a new pathway into this old, old territory. And so I'm going to start by telling you a story. It begins, of course, Once Upon a Time.

Once upon a time there was a girl who was forced to flee her childhood home. Why? Let's never mind that now. Perhaps her parents were too poor to keep her. Perhaps her mother was an ogre or a witch. Perhaps her father had promised her to a troll, a tyrant, or a beast. She left home with the clothes on her back, and soon she was tired, hungry, and cold. As night fell, she took shelter in a desolate graveyard thick with nettles and briars. Beyond the graves was a humpbacked hill and in the side of the hill was a door. The girl walked towards the door and saw a golden key standing in its lock. She turned the key, opened the door, and crossed over the threshold….

I can still remember that moonlit night, but I don't remember how old I was -- only that I was past the age when a girl should still believe in magic. Cold and quietly miserable in a childhood that seemed never-ending, I sat hunkered down in the grass among the gravestones of my grandfather's church, trying to conjure a portal to a magic realm by sheer force of will. Like many children, I longed to discover a door to Faerie, a road to Oz, a wardrobe leading to Narnia, and I wanted to believe that if I wished with all my strength and all my will then surely a door would open for me. Surely they would let me in.

I wanted to flee unhappiness, yes, but there was more to my desire than this – more than just escape from the intolerability of Here and Now. My desire was also a spiritual one – for we often forget that spiritual quest is a common and natural part of childhood, as young people struggle to understand how they fit into the world around them. That night, my solemn conviction was that I did not fit into the world I knew, and so I sought to cross into some other world, through the power of imagination. Did I really think it might be possible? To tell the truth, I no longer know. But my longing for that door was real; and my sharp, physical, painful desire for the things I imagined lay just beyond: Vast, unmapped, unspoiled forests. Rivers that were clean and safe to drink. Wolves and bears who would guide my way once I'd learned the power of their speech. My childhood in the ordinary world was a transient, uprooted one; but beyond the door I'd find my place, my power, and my true home.

Like many children hungry for intimate connection with the spirit-filled unknown, what I failed to manifest that night I found in my favorite children's books: in fairy tales, myths, and other tales of border-crossing and enchantment. I read these stories over and over. I devoured them and I needed them. But there came a time when I understood that I was growing too old for fairy stories, and I slipped them to the back of the shelves, embarrassed by my attachment to them. I was dutiful. I read "realistic" books about teen detectives, inventors, and spies; I read teen romances and girl-with-horse novels. I watched the wholesome Brady Bunch and the Partridge Family on television…and nowhere in the popular culture of the '60s did I see a life and a family that was remotely like mine. Secretly, I still preferred those fairy stories that I was meant to out-grow. I found a strange kind of comfort in them, though I couldn't have told you why.

If only I'd known that in centuries past such stories weren't labeled For Young Children Only, I wouldn't have felt so obliged to hide these volumes behind Nancy Drew. I wish I'd known that magical tales had been loved by adults for thousands of years; and that in Europe the oldest known fairy tale collections had been published in adult editions, savored by the literary avante garde in 16th century Italy and 17th century France. Thanks to the work of contemporary fairy tale scholars we now know that early versions of familiar tales (Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, etc.) were sensual, dark, and morally complex. In the 16th century version of Sleeping Beauty, the princess is awakened not by a chaste, respectful kiss, but by the birth of twins after the prince has come, fornicated with her sleeping body, and left again (returning to a wife back home). In one of the oldest known versions of Snow White's tale, a passing prince claims the girl's dead body and locks himself away with it, pronouncing himself in love with his beautiful "doll," whom he intends to wed. (His mother, complaining of the dead girl's smell, is greatly relieved when her son's macabre fiancé comes back to life.) In older versions of the Bluebeard narrative (such as Silvernose and Fitcher's Bird), the heroine does not sit trembling while waiting for her brothers to rescue her – she outwits her captor, kills him, and restores the lives of her murdered predecessors. Cinderella doesn't sit weeping in the cinders while talking bluebirds flutter around her; she is a clever, angry, feisty girl who seeks her own salvation – with the help of advice from her dead mother's ghost, not the twinkle of fairy magic.

It was not until the 19th century that volumes of fairy tales aimed specifically at children became the industry standard, supplanting the arch, sophisticated editions penned by authors of previous generations. Advances in cheap printing methods had created a hot new market in children's books, and Victorian publishers sought products with which to tap into this lucrative trade. Ironically, the way was led by two scholarly German folklorists, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, editors of a German folk tale collection published for fellow academics. Upon realizing that a larger audience could be found among children and their parents, the Grimms revised their collection to make the tales more suitable for young readers, altering the stories more and more with each subsequent edition. The commercial success of the Grimms volume was noted by publishers in Germany and beyond, and soon there were numerous other fairy tale books aimed specifically at children -- filled with stories drawn from 16th, 17th, and 18th century fairy tale literature, now simplified and heavily revised to reflect Victorian "family values" and gender ideals.

As the next century dawned, the pendulum of adult literary fashion swung to tales of domestic realism while fairy tales and fantasy were increasingly left to the kids. Worse was to come as the century progressed, for Walt Disney would do more to turn fairy tales into pap than all of the Victorian fairy books put together as he rendered classic stories into animated films deemed suitable for American family viewing. Responding to criticism of the extensive changes he'd made in fairy tales like Snow White, Disney said: "It's just that people now don't want fairy stories the way they were written. They were too rough. In the end they'll probably remember the story the way we film it anyway."

Disney's fairy tale films, and the imitative books they spawned, went a long way to foster the modern misconception that fairy tales are children's stories and have always and only been children's stories. Yet fairy tales, J.R.R. Tolkien pointed out (in his lecture "On Fairy-stories," 1938) have no particular historical association with children; they'd been pushed into the nursery like furniture the adults no longer want and no longer care if its misused. "Fairy–stories banished in this way," he said, "cut off from a full adult art, would in the end be ruined; indeed, in so far as they have been so banished, they have been ruined."

Professor Tolkien himself deserves much of the credit for bringing magical tales back to an adult audience, which he did, of course, through the international success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien's books surprised critics by striking a chord with readers of all ages and from all walks of life, directly challenging the assumption that fantasy had no place on adult bookshelves. Today, a generation of readers who have grown up with Bilbo and Frodo Baggins – not to mention Sparrowhawk, Harry Potter, Lyra Belacqua, and the whole modern fantasy publishing genre – may not fully comprehend the boundary-busting nature of Professor Tolkien's achievement.

In the place and time where I grew up, for example, there were only a very few fantasy books available in the local library (the Narnia books, the Oz books, The Wind in the Willows, a handful of others ), strictly confined to the children's section – and somewhat suspect even there. Fantasy, I understood, was like the training wheels on my first two-wheel bike: a forgivable crutch at the outset, but one I was meant to progress beyond needing. I hadn't progressed. I still craved such tales, though they stood on shelves meant for much younger kids. A worried librarian actually took The Blue Fairy Book out of my check-out stack, replacing it with a more "age appropriate" (and insipid) story about a perky camp counselor. The message was clear: fantasy belonged to the children who still played with dress-up dolls, and my craving for it led me to think there was something wrong with me. It was only later that I learned that others shared this craving, including adults. "I desired dragons with a profound desire," wrote J.R.R. Tolkien of his own adolescence. "Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood…. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fáfnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever the cost of peril."

It wasn't until I turned fourteen that I discovered Tolkien's trilogy, although the books had been available in American editions for some years before that. I began The Fellowship of the Ring on the school bus on a grey winter morning, reading with pure amazement as Middle Earth opened up before me. Here, in the language of fantasy, was a story that seemed more real to me than any "realistic" story I knew -- a story about danger, terror, and courage; about the cost of heroism and the importance of moral choices. In Middle Earth, as in my parent's house, an epic battle between good and evil was waging, and even a humble, seemingly-powerless creature like a hobbit could affect its outcome.

Some months after The Lord of the Rings, I discovered Tolkien's slim volume Leaf by Niggle containing his lecture/essay "On-Fairy Stories" – which was, for me, a more influential text than all the good professor's celebrated fiction. It was here I first learned that fairy tales had an old and a noble lineage -- and that they'd once been more, so much more, than the Disney versions known today. I dug out my favorite fairy tale books and I read the old tales with new eyes; and this time I understood why I'd clung to these stories for so many years. Like Tolkien's books, they addressed large subjects: good and evil, cowardice and courage, hope and despair, peril and salvation – all subjects not unfamiliar to children raised in embattled households. Fairy tales spoke, in their metaphorical language, of danger, struggle, calamity – and also of healing journeys, self-transformation, deliverance, and grace. The fairy tales that I loved best (Donkeyskin, The Wild Swans, The Handless Maiden) were variations on one archetypal theme: a young girl beset by grave difficulties sets off, alone, through the deep, dark woods. Armed with quick wits, clear site, persistence, courage, compassion, and a dollop of luck, she meets every challenge, solves every riddle, and transforms herself and her fate. This was my story, my myth, the central text and theme of my young life's journey. This was the story I needed to hear again and again and again.

There is irony in the fact that the door I'd been looking for that night among the graves had been right in front of me all along, in the pages of those old fairy tale books. But I'd needed Tolkien's lecture to understand what it was I loved about fairy tales; his words were the golden key that finally opened the door for me. I then crossed the threshold into the land of Story, where I have been travelling ever since: wandering its vast forests, drinking from its clear, cold streams, learning to speak with wolves and bears (which, as it turns out, is not half as hard as you would think).

If I could have one Magic Wish today, I would like to travel back in time and to find that miserable girl among the graves, appearing before her like a classic Good Fairy, draperies flapping in the wind behind me. This is what I would like to tell her (and, indeed, every other child just like her): "There are better worlds out there, my dear. And I promise you, you're going to find them."

Picture Credits: Terri Windling: photo by Alan Lee

Hansel and Gretel by Arthur Rackham

Published on June 10, 2011 00:10

June 2, 2011

Exciting Things!

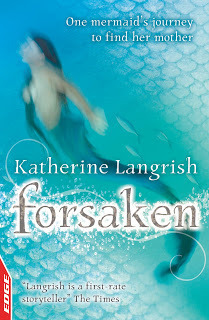

Two exciting things, actually. The first is the lovely cover of the new book I've written. 'Forsaken' will be published in November by Franklin Watts EDGE, and is one of a series, commissioned from several different well-known children's authors (*modest cough*), of quick reads children aged nine and over – children who are competent readers but might feel daunted by a thick, 350 page novel.

Two exciting things, actually. The first is the lovely cover of the new book I've written. 'Forsaken' will be published in November by Franklin Watts EDGE, and is one of a series, commissioned from several different well-known children's authors (*modest cough*), of quick reads children aged nine and over – children who are competent readers but might feel daunted by a thick, 350 page novel. This is as sophisticated a story as I've ever written, so I hope some of you adults will like it too. You can fit a lot into a little room.

Last week I was thinking about waterspirits – naiads and undines and kelpies – the denizens of fresh water, rivers, lakes and tarns. But the salt sea has always been the province of mermaids. And rather as fairies were downgraded to flowery little creatures with butterfly wings and sparkly wands, so mermaids – ever since Disney's Ariel, perhaps – have gone sparkly too. Long blonde hair, mirrors and combs: perhaps the accessories don't help – and don't get me wrong, I don't mind this at all, any more than I mind little girls poring over the Flower Fairy books, as my own daughters used to do. Sweet little mermaids are safe and happy reading for little girls. But what about older children?

I'm not even going down the route of the siren, the mermaid as death omen, precursor of shipwrecks. No, where I started from in this little book was the original legend behind Matthew Arnold's classic poem 'The Forsaken Merman'. It's called 'Agnete and the Merman' and I found it in an old book of Scandinavian poetry. In it, as in Arnold's poem, a mortal woman marries a Merman and has seven children by him. One day, as she sits singing under the blue water she 'hears the clocks of England clang' and seeks leave to revisit land and go to church once more.

Once back on shore, however, she refuses to return to the sea. In Arnold's poem, which I really love, the Merman and his children call wildly and vainly for their lost wife and mother from the bay, until at last they accept that she will never return.

But children, at midnight,

When soft the winds blow,

When clear falls the moonlight,

When spring-tides are low:

When sweet airs come seaward

From heaths starr'd with broom,

And high rocks throw mildly

On the blanch'd sands a gloom,

Up the still, glistening beaches,

Up the creeks we will hie,

Over beds of bright seaweed

The ebb-tide leaves dry:

We will gaze, from the sand-hills

At the white, sleeping town,

At the church on the hillside –

And then come back down,

Singing, 'There dwells a loved one,

But cruel is she.

She left lonely for ever

The kings of the sea.

There seems to me a great tragic tension in this poem and in the older ballad – the same tension that is found in the Orkney stories of the selkie wife who leaves her fisherman husband to return to the sea. (Which is the same story in reverse, and an important element of my book Troll Mill, the second part of West of the Moon). These stories are about an unbridgeable strangeness between husband and wife, perhaps more specifically the terrible strangeness caused by post-natal depression. They're about seeing someone – even someone as close to you as your partner – as alien. In the Merman story, and with Andersen's story of The Little Mermaid, despite the little mermaid's bargain with the sea-witch – it's not really the physical fact that the mer-people have tails and the humans have legs that causes the trouble. It's the perceived 'fact' that mer-people don't have souls. This will cause the eventual eternal separation of any mer/human marriage anyway; so no wonder the Merman husband, though he calls so desperately, and even climbs on the gravestones in the churchyard to peep through the church windows, will never win his Margaret back.

Then I thought, but what if one of the children went after her mother to try and bring her back? And with that idea, which totally grabbed me, this book just flowed.

And my second Very Exciting Thing is that a new series of Fairytale Reflections will begin on this blog next Friday, and the opening essay will be from the amazing Terri Windling, author of 'The Wood Wife' - which won the Mythopoeic Award for Novel of the Year in 1996 - and fantasy editor extraordinaire.

I'm posting a little early this week, as I'm going away for a few days. Have a good weekend, everyone!

Published on June 02, 2011 05:17

May 27, 2011

On Water

Water.

Water.You can touch it, but you can't hold it. It runs between your fingers. It flows away in streams, in rivers, talking to itself. It's a metaphor for time.

It reflects things – trees, the sky – but upside down, distorted and fluid. Peer over the brink and your own face peeks up at you, like yet unlike, pale and transparent. It could be another you, living in another world. Maybe in The Other World. After all, you can't breathe water...

You can drink it, wash in it, water your fields with it. It turns your mill wheel to grind your corn, but it can also drown you or your children and sweep you away. Homely, treacherous, necessary, strange, elemental, no wonder that we populated it with spirits. Goddesses like Sabrina, or loreleis, ondines, naiads, nixies: sly, beautiful, impulsive but cold-hearted nymphs whose white arms pull you down to drown. To say nothing of kelpies, in whom the brute force and treacherous nature of water gets its true personification...

I've always loved the well known 'Overheard on a Salt Marsh' by Harold Monro, a dialogue between a goblin and a water nymph.

Nymph, nymph, what are your beads?

Green glass, goblin. Why do you stare at them?

Give them me.

No.

Give them me, give them me.

No.

Then I will howl all night in the reeds,

Lie in the mud and howl for them.

Goblin, why do you love them so?...

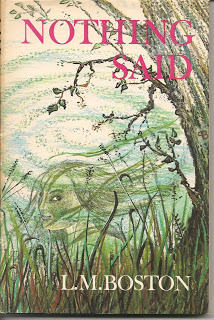

It's a poem which can be found in Lucy Boston's lyrical short book 'Nothing Said', Faber 1971 – in which the heroine Libby finds a green glass bead in a stream – and is one of many fairytale and literary references in Delia Sherman's witty and delightful 'The Magic Mirror of the Mermaid Queen',Viking 2009: the heroine Neef (the Official Changeling of New York's Central Park) hears of a clue to the whereabouts of the magic mirror she is searching for:

It's a poem which can be found in Lucy Boston's lyrical short book 'Nothing Said', Faber 1971 – in which the heroine Libby finds a green glass bead in a stream – and is one of many fairytale and literary references in Delia Sherman's witty and delightful 'The Magic Mirror of the Mermaid Queen',Viking 2009: the heroine Neef (the Official Changeling of New York's Central Park) hears of a clue to the whereabouts of the magic mirror she is searching for:"It's in Riverside Park… This goblin's been howling. Everybody's heard it that lives on Riverside Drive. …Howl, howl, howl all night, every night. Nobody's got any sleep…"

Then again, rivers can be gods, like TS Eliot's 'strong brown god,' the Thames, or Stevie Smith's 'River God':

I may be smelly and I may be old,

Rough in my pebbles, reedy in my pools,

But where my fish float by I bless their swimming

And I like the people to bathe in me, especially women.

But I can drown the fools

Who bathe too close to the weir, contrary to rules.

And they take a long time drowning

As I throw them up now and then in the spirit of clowning.

Hi yi, yippety-yap, merrily I flow,

Oh I may be an old foul river but I have plenty of go…

King Arthur's sword Excalibur comes from under the water:

They rode till they came to a lake, that was a fair water and broad, and in the midst of the lake Arthur was ware of an arm clothed in white samite, that held a fair sword in that hand.

Merlin and Arthur are advised by a 'damosel' (the Lady of the Lake) to row a barge over to the arm:

And when they came to the sword that the hand held, Sir Arthur took it up by the handles… and the arm and the hand went under the water.

At the very end of the Morte D'Arthur, at Arthur's command Sir Bedivere brings himself (on the third attempt) to throw Excalibur into the lake again:

And he threw the sword as far into the water as he might; and there came an arm and a hand above the water and met it, and caught it, and shook it thrice and brandished, and then vanished away the hand with the sword in the water. So Sir Bedivere came again to the king and told him what he saw.

"Alas", said the king, "help me hence, for I dread me I have tarried over-long."

It's as though only once the return of the sword has been accomplished can Arthur set off for Avalon in the barge full of queens and ladies clad in black. We know that the Celts made many offerings of swords and weaponry to rivers, as these Bronze Age examples show. What the significance was, we can only guess, but even today people throw coins into fountains and 'wishing wells'.

In Frederick de la Motte Fouqué's 'Undine' (1807), a knight marries a river spirit, Undine, and swears eternal faithfulness to her. However, his previous mistress, Bertalda, sows suspicion of Undine in his mind, and he comes to regard her unbreakable bond with the waterspirits – and especially with her terrifying uncle Kuhlborn, the mountain torrent – with fear and disgust. He repudiates his union with Undine and prepares to marry Bertalda instead. There is a genuinely spine-tingling climax, as the well in the castle bubbles uncontrollably up to release the veiled figure of the Undine, who walks slowly through the castle to the knight's chamber. In my 1888 translation:

The knight had dismissed his attendants and stood in mournful thought, half-undressed before a great mirror, a torch burnt dimly beside him. Just then a light, light finger knocked at the door; Undine had often so knocked in loving sportiveness.

"It is but fancy," he said to himself; "I must to the wedding chamber."

"Yes, thou must, but to a cold one!" he heard a weeping voice say. And then he saw in the mirror how the door opened slowly, slowly, and the white wanderer entered, and gently closed the door behind her.

"They have opened the well," she said softly, "And now I am here and thou must die."

Ignore the force of water at your peril. And what follows isn't a fanciful poem at all. It's a tribute to the volunteers of Clapham Cave Rescue Organisation up in Yorkshire, who spend a good part of every year pulling people, dead or alive, out of rivers and water-filled potholes.

Cave Rescue Workers at Ingleton Falls

As the wet rescuers come stumbling out of

the greedy water, gasping from their dive,

"Christ," they say, spitting, pushing up their masks,

"it took us all our time to stay alive."

Somewhere below that creaming soapy surface

the drowned man is rolling, arms flung out:

thrown against rocks, knocked, tumbled and abraded,

kissing the water with his open mouth.

The weary divers huddle on the pathway

now black and slippery with the driving rain.

"We'll find him further down."

They know he's dead.

They lug the gear downstream to try again.

Poem: 'Cave Rescue Workers at Ingleton Falls' copyright Katherine Langrish 2011

Image: 'Ingleton Falls in Flood' copyright Bob Jenkins

Detail from 'Hylas and the Nymphs' by John Waterhouse

Published on May 27, 2011 01:27

May 20, 2011

Lost to the Faeries

How much do you know about faeryland? If you've spent as much time as I have reading the (many of them wonderful) modern YA fantasy novels about faeries, you may think you've got it pat. Many of them involve doomed but brilliant young men in thrall to a beautiful, capricious and often cruel faerie queen. Often it's the heroine's role to try and rescue the young man, who would be her boyfriend or lover if only he were free. Examples are Holly Black's fantastic 'Tithe' and its sequels, and Gillian Philip's equally fantastic 'Firebrand'.

I think this particular theme has its source in the 16th century ballads 'Tam Lin' and 'Thomas the Rhymer' – especially the former: Janet saves her lover Tam Lin from the worst possible fate by her bravery and single-mindedness. She goes to Miles Cross at midnight and waits for the Seelie Court to go riding by, seizes Tam Lin from his horse and holds on to him while he is transformed into a number of horrifying shapes. At last he appears in his own shape, a naked man, and Janet casts her cloak around him and claims him as her own true love, while the furious fairy queen can only threaten and rage.

And the story, in which a woman rescues a man, is popular today partly because we got tired of the stereotype of 'man rescues woman'. We want strong women, and in this legend we get double offerings: staunch Janet, and the powerful Queen of Fays. I was looking for a good picture to illustrate the modern notion of a fairy queen - vengeful, beautiful, dangerous - and came across this electrifying photo of Maria Callas as Medea, taken in Dallas, Texas, 1958. (And yes, Medea is a witch queen rather than a faery queen, but same difference.)

Naturally we don't want weak male characters either. Tam Lin in the ballad is far from effeminate – the very first verse warns maidens to keep away from him, and he rapidly gets Janet pregnant – but let's face it, there's something sexy about a handsome young man in bondage to a cruel queen, and sexy goes down well in YA fiction… and so we've all got used to it: Faeryland is ruled by a dangerous queen. And the idea of the tithe to hell, the sacrifice of the young man, meshes with the figure of the dying Corn King or Year King made familiar by Sir James Fraser's 'The Golden Bough', and Jessie Weston's 'From Ritual to Romance'. (I wouldn't expect many teenagers to have heard of either, and apparently modern anthropologists have their doubts that Corn Kings were ever sacrificed in fact – but the idea is there in the back of a lot of fantasy writers' minds, I'm sure.)

Anyway, all this is something of a preamble: I want to point out that fairyland hasn't always been this way. In fact I'm not at all sure that the all-powerful Faery Queen even existed in the popular imagination before the 16th century when Queen Elizabeth I was lauded by Edmund Spenser as Gloriana, the Faerie Queen herself.

Prior to that, Fairyland was ruled by kings. The Welsh Annwn was ruled by King Arawn. In the early medieval metrical romance 'Sir Orfeo' where Celtic and English fairy lore blends with the Greek myth of Orpheus, the fairy king is clearly Pluto, lord of the dead – but is not named. In the Irish tale, 'The Wooing of Etain', the beautifu Etain is stolen away by a fairy king called Midir. And in a legend related by the 12th century courtier Walter Map, a British King called Herla is invited to a wedding by an unnamed, goat-footed pigmy king who rules underground halls of unutterable splendour. Also pigmy-sized is the Fairy King in the French fairy romance 'Huon of Bordeaux': Auberon, a dwarf with the face of beautiful child – whose name resurfaces in A Midsummer Night's Dream as Oberon.

These early fairy kings rule over lands which are usually underground, and there is a pervading sense of loss that hangs about them. When Herla visits the pigmy king's halls, he loses his own time: like Oisin returning from the Land of Youth, he finds himself hundreds of years in the future. He cannot dismount from his horse without crumbling to dust, and therefore still rides the Welsh border hills at the head of his troop of knights. In a tale called 'The Sons of the Dead Woman', Walter Map tells of a Breton knight who buried his wife and then saw her one evening dancing in a gloomy valley, in a ring of maidens. When the fairy king steals Orfeo's wife, she is mourned as dead. And yet, tantalisingly, the dead may not be quite dead, but stolen away into some other dimension, some fairy realm of half-existence. This is the fantasy of grief. And of course, time runs differently there: if you visit, you risk losing yourself forever.

This 12th century fairyland, the mysterious underground kingdom, is the fairyland I wrote about in my book 'Dark Angels' (The Shadow Hunt' in the USA). One of the characters, the troubadour knight Lord Hugo, lost his wife seven years before the book opens:

"The night she died – it was New Year's Eve, and the candles burned so low and blue, and we heard over and over again the sound of thunder. That was the Mesnie Furieuse – the Wild Host – riding over the valleys. Between the old year and the new, between life and death – don't you think, when the soul is loosening from the body, the elves can steal it?"

But, this month, I've been promising you poems. Here is one I love. It's by Rudyard Kipling, from 'Rewards and Fairies'. It's written in a Sussex dialect, and speaks poignantly and tenderly of loss and longing.

BROOKLAND ROAD

I was very well pleased with what I knowed,

I reckoned myself no fool –

Till I met with a maid on the Brookland Road

That turned me back to school.

Low down – low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

Oh! maids, I've done with 'ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

'Twas right in the middest of a hot June night,

With thunder duntin' round,

And I seed her face by the fairy light

That beats from off the ground.

She only smiled and she never spoke,

She smiled and went away;

But when she'd gone my heart was broke,

And my wits was clean astray.

Oh! Stop your ringing and let me be –

Let be, O Brookland bells!

You'll ring Old Goodman out of the sea,

Before I wed one else!

Old Goodman's farm is rank sea sand

And was this thousand year;

But it shall turn to rich ploughland

Before I change my dear!

Oh! Fairfield Church is water-bound

From Autumn to the Spring,

But it shall turn to high hill ground

Before my bells do ring!

Oh! leave me walk on the Brookland Road

In the thunder and warm rain –

Oh! leave me look where my love goed,

And p'raps I'll see her again!

Low down – low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

Oh! maids, I've done with 'ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

Picture credits: Maria Callas as Medea, 1958, Dallas, Texas

Orpheus and Euridice by Christian Kratzastein-Stub, 1783 - 1816

Orpheus leading Euridice from the Underworld by Camille Corot

I think this particular theme has its source in the 16th century ballads 'Tam Lin' and 'Thomas the Rhymer' – especially the former: Janet saves her lover Tam Lin from the worst possible fate by her bravery and single-mindedness. She goes to Miles Cross at midnight and waits for the Seelie Court to go riding by, seizes Tam Lin from his horse and holds on to him while he is transformed into a number of horrifying shapes. At last he appears in his own shape, a naked man, and Janet casts her cloak around him and claims him as her own true love, while the furious fairy queen can only threaten and rage.

And the story, in which a woman rescues a man, is popular today partly because we got tired of the stereotype of 'man rescues woman'. We want strong women, and in this legend we get double offerings: staunch Janet, and the powerful Queen of Fays. I was looking for a good picture to illustrate the modern notion of a fairy queen - vengeful, beautiful, dangerous - and came across this electrifying photo of Maria Callas as Medea, taken in Dallas, Texas, 1958. (And yes, Medea is a witch queen rather than a faery queen, but same difference.)

Naturally we don't want weak male characters either. Tam Lin in the ballad is far from effeminate – the very first verse warns maidens to keep away from him, and he rapidly gets Janet pregnant – but let's face it, there's something sexy about a handsome young man in bondage to a cruel queen, and sexy goes down well in YA fiction… and so we've all got used to it: Faeryland is ruled by a dangerous queen. And the idea of the tithe to hell, the sacrifice of the young man, meshes with the figure of the dying Corn King or Year King made familiar by Sir James Fraser's 'The Golden Bough', and Jessie Weston's 'From Ritual to Romance'. (I wouldn't expect many teenagers to have heard of either, and apparently modern anthropologists have their doubts that Corn Kings were ever sacrificed in fact – but the idea is there in the back of a lot of fantasy writers' minds, I'm sure.)

Anyway, all this is something of a preamble: I want to point out that fairyland hasn't always been this way. In fact I'm not at all sure that the all-powerful Faery Queen even existed in the popular imagination before the 16th century when Queen Elizabeth I was lauded by Edmund Spenser as Gloriana, the Faerie Queen herself.

Prior to that, Fairyland was ruled by kings. The Welsh Annwn was ruled by King Arawn. In the early medieval metrical romance 'Sir Orfeo' where Celtic and English fairy lore blends with the Greek myth of Orpheus, the fairy king is clearly Pluto, lord of the dead – but is not named. In the Irish tale, 'The Wooing of Etain', the beautifu Etain is stolen away by a fairy king called Midir. And in a legend related by the 12th century courtier Walter Map, a British King called Herla is invited to a wedding by an unnamed, goat-footed pigmy king who rules underground halls of unutterable splendour. Also pigmy-sized is the Fairy King in the French fairy romance 'Huon of Bordeaux': Auberon, a dwarf with the face of beautiful child – whose name resurfaces in A Midsummer Night's Dream as Oberon.

These early fairy kings rule over lands which are usually underground, and there is a pervading sense of loss that hangs about them. When Herla visits the pigmy king's halls, he loses his own time: like Oisin returning from the Land of Youth, he finds himself hundreds of years in the future. He cannot dismount from his horse without crumbling to dust, and therefore still rides the Welsh border hills at the head of his troop of knights. In a tale called 'The Sons of the Dead Woman', Walter Map tells of a Breton knight who buried his wife and then saw her one evening dancing in a gloomy valley, in a ring of maidens. When the fairy king steals Orfeo's wife, she is mourned as dead. And yet, tantalisingly, the dead may not be quite dead, but stolen away into some other dimension, some fairy realm of half-existence. This is the fantasy of grief. And of course, time runs differently there: if you visit, you risk losing yourself forever.

This 12th century fairyland, the mysterious underground kingdom, is the fairyland I wrote about in my book 'Dark Angels' (The Shadow Hunt' in the USA). One of the characters, the troubadour knight Lord Hugo, lost his wife seven years before the book opens:

"The night she died – it was New Year's Eve, and the candles burned so low and blue, and we heard over and over again the sound of thunder. That was the Mesnie Furieuse – the Wild Host – riding over the valleys. Between the old year and the new, between life and death – don't you think, when the soul is loosening from the body, the elves can steal it?"

But, this month, I've been promising you poems. Here is one I love. It's by Rudyard Kipling, from 'Rewards and Fairies'. It's written in a Sussex dialect, and speaks poignantly and tenderly of loss and longing.

BROOKLAND ROAD

I was very well pleased with what I knowed,

I reckoned myself no fool –

Till I met with a maid on the Brookland Road

That turned me back to school.

Low down – low down!

Where the liddle green lanterns shine –

Oh! maids, I've done with 'ee all but one,

And she can never be mine!

'Twas right in the middest of a hot June night,

With thunder duntin' round,

And I seed her face by the fairy light

That beats from off the ground.

She only smiled and she never spoke,

She smiled and went away;

But when she'd gone my heart was broke,

And my wits was clean astray.

Oh! Stop your ringing and let me be –

Let be, O Brookland bells!

You'll ring Old Goodman out of the sea,

Before I wed one else!

Old Goodman's farm is rank sea sand

And was this thousand year;

But it shall turn to rich ploughland