Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 33

September 14, 2012

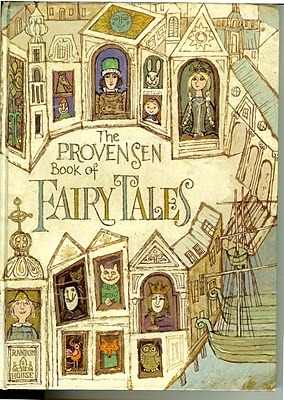

"The Provenson Book of Fairytales" (with scary pictures)

by Megan Whalen Turner

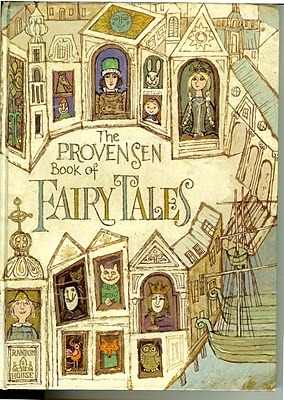

When Katherine asked if I might like to write a blog post about my favorite fairy tale, I drew a blank. I’m almost afraid to admit this, but I didn’t like fairy tales when I was a kid. I thought they were dry, their characters two dimensional and their plots predictable. But as I wrote my e-mail, meaning to decline, one particular book did come to mind. It was Alice and Martin Provensen’s book of fairy tales, and I remembered it mainly for the illustrations, which were terrifying.

I asked Katherine if that sort of subject would do for a non-fairy tale reader and she said, yes. So . . .

This book sat on my shelf untouched for years. Too disturbing to read, too compelling to overlook, it was a gift and absolutely could not be sent off to the library book sale. No matter how many times I weeded my collection, it always remained. There on the shelf, with its dark mesmerizing illustrations in black and purple and virulent green.

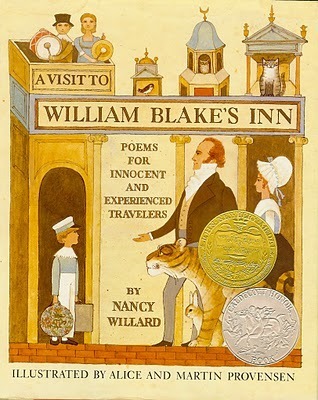

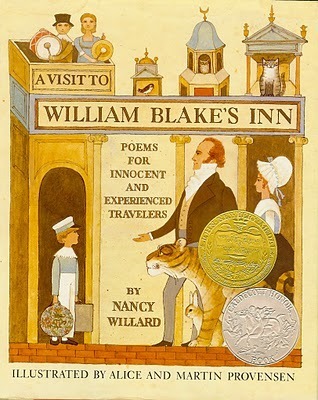

Those of you familiar with the deeply charming Animals of Maple Hill Farm, or with A Visit to William Blake's Inn which won both the Newbery Award and a Caldecott Honor in 1982 might be surprised that anything by the Provensens could be that disturbing.

Yes, well they were always about more than cats and bunnies and talking sunflowers. In The Animals of Maple Hill Farm the Provensens introduce you to all the hens and roosters at their farm in a two page spread that includes examples of the obnoxious rooster, Big Shot, being nasty to the other roosters and bullying the hens, and then Big Shot gets carried off by a fox.

And no one minds, they say with a shrug.

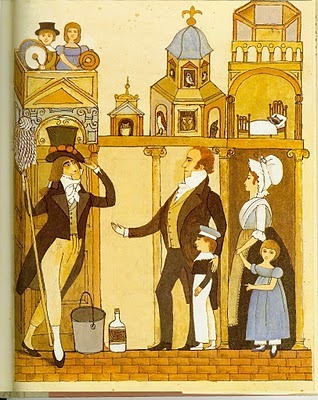

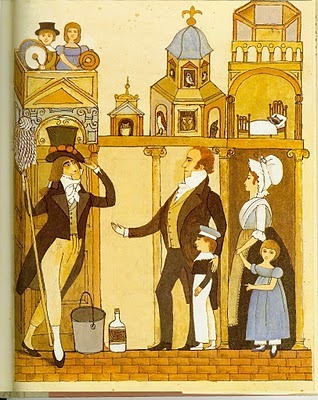

Look through A Visit to William Blake’s Inn and notice the semi-circular smile on the Man in the Marmalade Hat. That's him on the left.

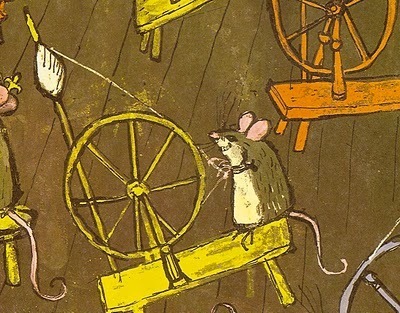

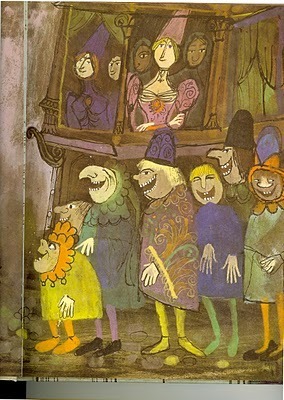

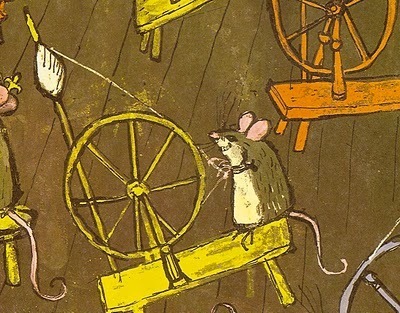

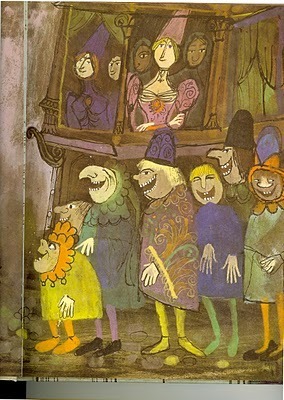

Observe his chiclet style teeth. Imagine an entire book peopled with those smiles and those teeth, and no friendly anthropomorphic sunflowers, either. The best you get is some malevolent looking mice.

A mouse from "The Forest Bride" by Parker Filmore.

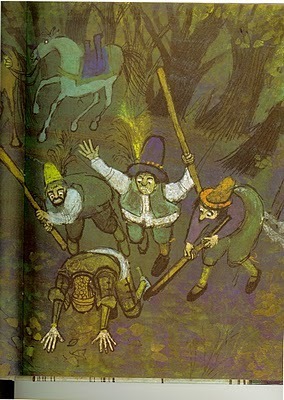

This from the story “The Lost Half Hour” by Henry Beston:

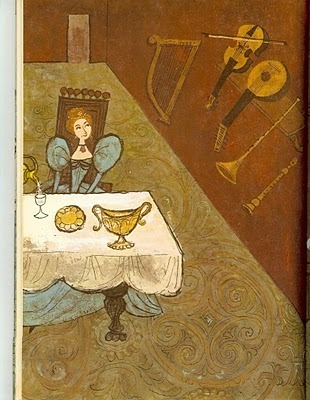

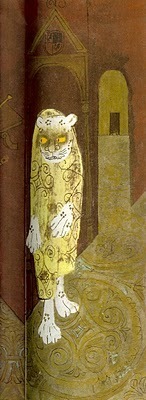

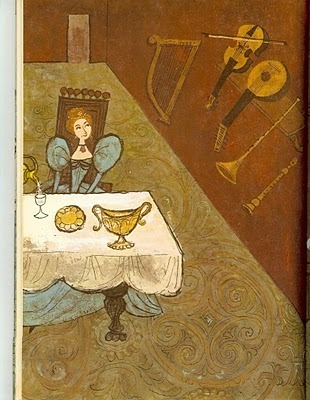

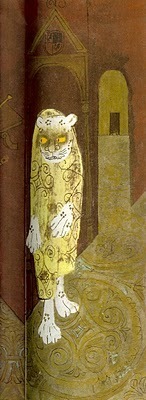

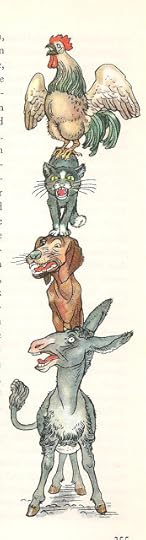

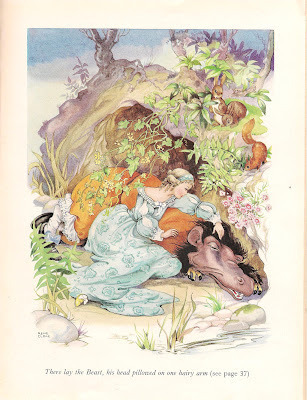

Or this from “Beauty and the Beast” by Arthur Rackham:

I couldn’t fit this into one scan, but if you look carefully you can piece together the composition with Beauty sitting at the table and the Beast lurking just around the corner. The Provensens have used the gutter between the pages to emphasize the corner in the image. The images aren’t merely frightening, they are brilliant and frightening. The hands of the beast are huge and clawed, yet they hang awkwardly, giving you the idea that in an unfortunate fumbling manner they might accidentally rip your arm off.

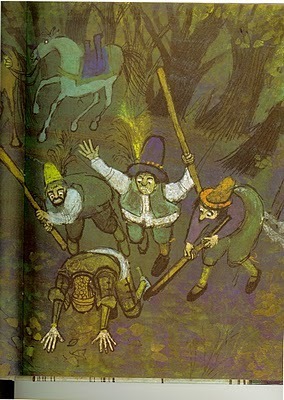

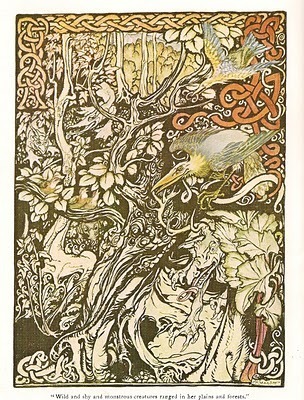

This is from the happy, upbeat (not), The Prince and the Goose Girl by Elinor Mordaunt.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

So, of course, I left it on the shelf when I grew up and moved out on my own. And I never read it when I visited home. No, never. And when I saw a copy at a thrift store, of course I said, “Oh, look!” And bought it instantly.

Okay, so there . . . there may be a contradiction there. And when I said the book sat on my shelf untouched? I lied. When I got the book home and looked through it, I remembered every single story. "The Lost Half Hour" where poor unfortunate Bobo is sent out by the Princess to find the half hour lost while she overslept. “Feather O’ My Wing” by Seamus McManus with the same spiteful stepsisters as “Beauty and the Beast,” but a story line a little more like “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Barbara Leonie Picard’s "Three Wishes" were the peasant boy gives away his hard earned wishes and receives them all back again.

And perhaps my favorite, “The Prince and the Goose Girl.” The heroine Erith is absolutely indomitable. She won’t back down, not even if it costs her life, and when the Prince realizes this he also realized that Erith is right that he isn’t much of Prince. Fortunately, he becomes a reformed man, and because Erith is as kind as she is brave, it all works out in the end.

Why, oh, why didn’t I think of "The Prince and the Goose Girl" when Katherine asked me to write a post?

I think the answer has something to do with the Introduction to the book, which may be the one part I really didn’t read. In the introduction Joan Bodger explains that these are literary fairy tales. The italics are hers, not mine and their elitism makes me uncomfortable, but I think Bodger is saying the same thing that I am struggling with. I didn’t like fairy tales when I was growing up because most of the things that were labeled “Fairy Tales” in my experience were those bowdlerized, dessicated versions that were three paragraphs long and came in books of a hundred or more and had absolutely no personality. Everything that gave them depth had been sifted out because it was rude, or it was frightening, or it made the story too long for its intended audience.

They were stripped down to their Propp’s morphology. I tend to think of them as skeletons of stories, but the Provensons remind me that they aren’t dead skeletons so much as a seed bank that any of us can draw on, and that when we do draw on this seed bank, what we are writing (with or without the upscale qualifier literary) is fairy tales.

Note from Katherine: It's an honour to have Megan on the blog. In about 1998 I was living in America, in upstate New York, and one of the bolt-holes for me and my two young daughters was the local Barnes and Noble (conveniently close to Toys R Us and a miniature horse ranch). Trawling the shelves one day - for myself, of course; the girls were in the littlies section - I pulled out a book called 'The Thief' by Megan Whalen Turner. It was a Newbery Honor book – I flicked it open and read a snippet – and thus met her narrator Gen (short for Eugenides), who is languishing in prison, loaded with chains, because:

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

Gen is truly an unreliable narrator – an infuriating, intelligent, secretive, multi-layered individual whom you get to like very much indeed. The book is set in an almost but-not-quite familiar early Mediterranean world, where gods are worshipped who resemble the Greek pantheon but are not – and where small city states war against one another, or form alliances, under the shadow of a powerful Eastern empire. 'The Thief' was followed by its sequels, ‘The Queen of Attolia’, ‘The King of Attolia’, and ‘A Conspiracy of Kings’ and from an impressive start they just get better and better. Beautiful writing. Lots of devious politics. Lots of twists. Unforgettable characters. I'm a huge fan, and I'm hoping there's going to be more...

When Katherine asked if I might like to write a blog post about my favorite fairy tale, I drew a blank. I’m almost afraid to admit this, but I didn’t like fairy tales when I was a kid. I thought they were dry, their characters two dimensional and their plots predictable. But as I wrote my e-mail, meaning to decline, one particular book did come to mind. It was Alice and Martin Provensen’s book of fairy tales, and I remembered it mainly for the illustrations, which were terrifying.

I asked Katherine if that sort of subject would do for a non-fairy tale reader and she said, yes. So . . .

This book sat on my shelf untouched for years. Too disturbing to read, too compelling to overlook, it was a gift and absolutely could not be sent off to the library book sale. No matter how many times I weeded my collection, it always remained. There on the shelf, with its dark mesmerizing illustrations in black and purple and virulent green.

Those of you familiar with the deeply charming Animals of Maple Hill Farm, or with A Visit to William Blake's Inn which won both the Newbery Award and a Caldecott Honor in 1982 might be surprised that anything by the Provensens could be that disturbing.

Yes, well they were always about more than cats and bunnies and talking sunflowers. In The Animals of Maple Hill Farm the Provensens introduce you to all the hens and roosters at their farm in a two page spread that includes examples of the obnoxious rooster, Big Shot, being nasty to the other roosters and bullying the hens, and then Big Shot gets carried off by a fox.

And no one minds, they say with a shrug.

Look through A Visit to William Blake’s Inn and notice the semi-circular smile on the Man in the Marmalade Hat. That's him on the left.

Observe his chiclet style teeth. Imagine an entire book peopled with those smiles and those teeth, and no friendly anthropomorphic sunflowers, either. The best you get is some malevolent looking mice.

A mouse from "The Forest Bride" by Parker Filmore.

This from the story “The Lost Half Hour” by Henry Beston:

Or this from “Beauty and the Beast” by Arthur Rackham:

I couldn’t fit this into one scan, but if you look carefully you can piece together the composition with Beauty sitting at the table and the Beast lurking just around the corner. The Provensens have used the gutter between the pages to emphasize the corner in the image. The images aren’t merely frightening, they are brilliant and frightening. The hands of the beast are huge and clawed, yet they hang awkwardly, giving you the idea that in an unfortunate fumbling manner they might accidentally rip your arm off.

This is from the happy, upbeat (not), The Prince and the Goose Girl by Elinor Mordaunt.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.So, of course, I left it on the shelf when I grew up and moved out on my own. And I never read it when I visited home. No, never. And when I saw a copy at a thrift store, of course I said, “Oh, look!” And bought it instantly.

Okay, so there . . . there may be a contradiction there. And when I said the book sat on my shelf untouched? I lied. When I got the book home and looked through it, I remembered every single story. "The Lost Half Hour" where poor unfortunate Bobo is sent out by the Princess to find the half hour lost while she overslept. “Feather O’ My Wing” by Seamus McManus with the same spiteful stepsisters as “Beauty and the Beast,” but a story line a little more like “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Barbara Leonie Picard’s "Three Wishes" were the peasant boy gives away his hard earned wishes and receives them all back again.

And perhaps my favorite, “The Prince and the Goose Girl.” The heroine Erith is absolutely indomitable. She won’t back down, not even if it costs her life, and when the Prince realizes this he also realized that Erith is right that he isn’t much of Prince. Fortunately, he becomes a reformed man, and because Erith is as kind as she is brave, it all works out in the end.

Why, oh, why didn’t I think of "The Prince and the Goose Girl" when Katherine asked me to write a post?

I think the answer has something to do with the Introduction to the book, which may be the one part I really didn’t read. In the introduction Joan Bodger explains that these are literary fairy tales. The italics are hers, not mine and their elitism makes me uncomfortable, but I think Bodger is saying the same thing that I am struggling with. I didn’t like fairy tales when I was growing up because most of the things that were labeled “Fairy Tales” in my experience were those bowdlerized, dessicated versions that were three paragraphs long and came in books of a hundred or more and had absolutely no personality. Everything that gave them depth had been sifted out because it was rude, or it was frightening, or it made the story too long for its intended audience.

They were stripped down to their Propp’s morphology. I tend to think of them as skeletons of stories, but the Provensons remind me that they aren’t dead skeletons so much as a seed bank that any of us can draw on, and that when we do draw on this seed bank, what we are writing (with or without the upscale qualifier literary) is fairy tales.

Note from Katherine: It's an honour to have Megan on the blog. In about 1998 I was living in America, in upstate New York, and one of the bolt-holes for me and my two young daughters was the local Barnes and Noble (conveniently close to Toys R Us and a miniature horse ranch). Trawling the shelves one day - for myself, of course; the girls were in the littlies section - I pulled out a book called 'The Thief' by Megan Whalen Turner. It was a Newbery Honor book – I flicked it open and read a snippet – and thus met her narrator Gen (short for Eugenides), who is languishing in prison, loaded with chains, because:

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

Gen is truly an unreliable narrator – an infuriating, intelligent, secretive, multi-layered individual whom you get to like very much indeed. The book is set in an almost but-not-quite familiar early Mediterranean world, where gods are worshipped who resemble the Greek pantheon but are not – and where small city states war against one another, or form alliances, under the shadow of a powerful Eastern empire. 'The Thief' was followed by its sequels, ‘The Queen of Attolia’, ‘The King of Attolia’, and ‘A Conspiracy of Kings’ and from an impressive start they just get better and better. Beautiful writing. Lots of devious politics. Lots of twists. Unforgettable characters. I'm a huge fan, and I'm hoping there's going to be more...

Published on September 14, 2012 01:00

September 11, 2012

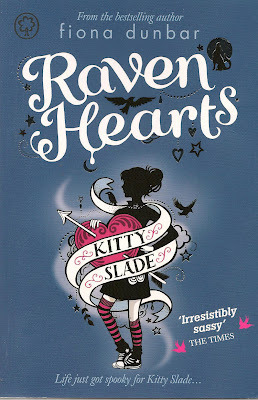

RAVEN HEARTS by Fiona Dunbar

My friend Fiona Dunbar's lively and exciting children's adventure stories leap boundaries and span genres: for example her brilliant ‘Silk Sisters’ trilogy, which mixes genome research and nano-technology with, believe it or not, fashion, and wittily poses the question: what if you really are what you wear?

My friend Fiona Dunbar's lively and exciting children's adventure stories leap boundaries and span genres: for example her brilliant ‘Silk Sisters’ trilogy, which mixes genome research and nano-technology with, believe it or not, fashion, and wittily poses the question: what if you really are what you wear?Now here comes Raven Hearts, the fourth in her series about the irrepressible Kitty Slade, whose ability to see ghosts (a talent called phantorama, inherited from her dead Greek mother) leads her into all sorts of adventures. Kitty is a determined and attractive heroine, who takes her uncomfortable gift firmly in her stride. The first in the series, Divine Freaks, featured a dodgy London landlord, a scalpel-wielding ghost in the school biology lab, a back-street taxidermist, shrunken heads, and a fraudulent antiques business. In the sequel, Fire and Roses Kitty deals with a poltergeist, and encounters the ghost of a member of the Hellfire Club (you can find Fiona's post about her research for this book here); while the third book,Venus Rocks, is set in Cornwall and includes a ghost ship and evil Cornish sprites called spriggans. From which you'll gather that a strong sense of place is one of the keynotes of these books.

So I was more than excited to read Raven Hearts, especially as it's set in Yorkshire on Ilkley Moor, where I spent much of my own childhood scrambling about wishing I could have adventures like Enid Blyton's Famous Five, although if I'd found as much excitement as Kitty does, I would undoubtedly have chickened out and decided reading about adventures was better than experiencing them, after all.

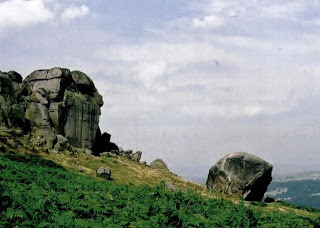

The Cow and Calf Rocks

The Cow and Calf RocksArriving in her family's camper van 'The Hippo' at a campsite near Ilkley Moor, Kitty rapidly becomes aware that all is not well. People have gone missing on the moor, which is rumoured to be haunted by a spectral black dog called the Barghest. (A nice Yorkshire folklore touch, that: Brontë devotees may remember Jane Eyre imagining the Barghest just before she meets Mr Rochester for the first time...) At the famous Cow and Calf Rocks Kitty meets a ghostly woman searching for her lost son. She hears childrens' voices chanting an eerie song (and yes, it's 'Ilkla Moor Baht'At', which when you think about is a pretty gruesome little ditty: 'the worms'll coom an' ate thee oop', etc.) She's haunted by ravens. And when she meets a highly unreliable spirit called Lupa, Kitty really does find herself in deadly danger...

I learned something while reading this book. I grew up knowing about the prehistoric Swastika Stone, the Roman baths at White Wells, and the massive Cow and Calf Rocks. But how come I'd never heard of the stone circle called the Twelve Apostles? Fiona Dunbar uses these settings deftly to create a sense of mystery; the story moves at a cracking pace, and by the time Kitty is cycling alone over the moor as dark falls and the moon rises, the stage is perfectly set for the appearance of something awful...

The Kitty Slade books are expertly pitched for the 9 + reader who wants something scary and exciting, but not TOO scary. One of the things I like most about them is that her heroine has back-up. Kitty can rely on her brother and sister for help, while her Greek grandmother Maro is a reassuring if eccentric presence. This helps steady the reader’s nerves through some of the more hair-raising passages. If you have a nine-to-thirteen year old in your life with a taste for mystery, ghosts, adventure and a (light) touch of horror, believe me, they're going to really, really enjoy this series.

RAVEN HEARTS by Fiona Dunbar, Orchard

Picture credits:

Cow and Calf, wikimedia commons, Hugh Chappell

Published on September 11, 2012 00:13

September 7, 2012

On Bedtime Stories

When my daughters were small I used to read aloud to them every evening, just as my mother used to read to me, and her mother to her, I dare say…generation before generation. It’s something I miss, now they’re all grown up. No matter what sort of day you’ve had, how cross and tired you may be, there’s something lovely about snuggling up with your children on the sofa, or on the edge of one of their beds (strictly alternating between younger daughter’s bedroom and older daughter’s bedroom: ‘it’s my turn tonight!’), and reading a book chapter by chapter.

Since they were keen readers anyway, I used to choose books to read aloud which I thought they might not actually pick for themselves. So instead of contemporary fiction I chose older books, things I’d loved as a child, books which might develop slowly, in that leisurely, let’s-take-time-over-the-first-chapter way which we’re not allowed to write any more, since children’s attention spans are now supposedly so short. Well, children love to be read to, and they rarely get bored while they’re cosied up next to you, the centre of your attention, listening to a lovely story competently read. It’s completely different from struggling along by themselves. Reading aloud is just a huge pleasure all round.

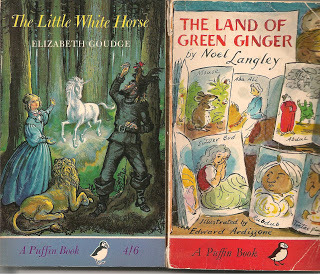

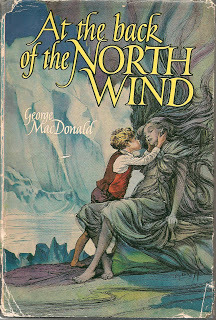

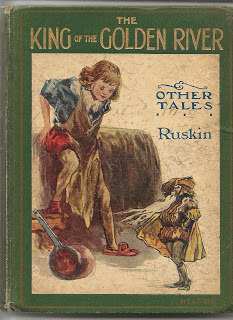

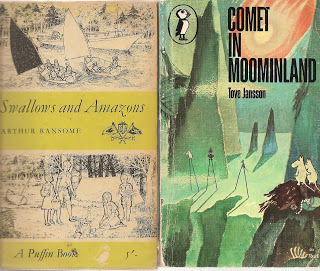

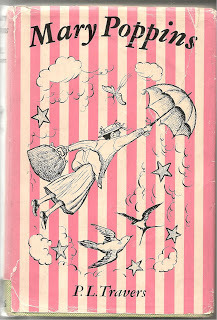

And so together we read all sort of classics. The Treasure Seekers, The Wouldbegoods, The Hobbit. Black Beauty, Brendon Chase, The Little Grey Men. The Brothers Lionheart, Finn Family Moomintroll, Martin Pippin in the Daisyfield. The Enchanted Castle, Mary Poppins, The Bogwoppit. The Land of Green Ginger, The Little House on the Prairie, A Christmas Carol. The King of the Golden River, The King of the Copper Mountains, the Chronicles of Narnia. Anne of Green Gables, Tuck Everlasting, The Search for Delicious. And many, many more.

Of course not every single book was a success. Neither child cared for Anne of Green Gables, to my surprise; and they never thought much of Jo March, either. Are today's children so used to independent, strong-minded heroines that flaming-haired Anne and hot-tempered Jo have paled in comparison? Both daughters regarded the March sisters as a bunch of wimpish goody-two-shoes who gave away their Christmas breakfast. And that was that.

One child loved The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge; the other was less keen. One went a bundle on The Treasure Seekers; her sister felt lukewarm about it. ‘Swallows and Amazons’ was an utter failure. I loved that book when I was a child (I remember when I first saw it, in a row of children’s books in the dark, glass-fronted bookcase on the landing of some farmhouse where we’d gone on holiday), but it fell completely flat as a read-aloud. I don’t know why. Maybe Ransome’s meticulous descriptions of how to do things – whether sailing a boat, building a campfire, or setting up a pigeon post – work better on the page? At any rate, this was the one and only book I ever read aloud which really did bore them to the point where I gave up, and we found something ‘more interesting’. Even the Narnia stories, which they enjoyed hearing, turned out not to be books they went back to re-read. But they did go back, again and again, to read many of these books and authors by themselves.

There’s something quite emotional about reading to your children, especially stories with which you feel a special connection. Books I read with total composure as a child can now bring tears to my eyes, and I have developed a family reputation for doing a wobble on the last page. Black Beauty in old age, dreaming of the past:

‘My troubles are all over and I am at home; and often, before I am quite awake, I fancy I am still in the orchard at Birtwick, standing with my old friends under the apple trees.’

Or: ‘They thought he was dead. I knew he had gone to the back of the north wind.’

Or: ‘It is autumn in Moomin valley – for how else can spring come back again?’

I’d be struggling to keep my voice level, and tears would come brimming up. The children pounced on this. They would sit up as I turned the last page, watching me like hawks for any signs of sentiment. They regarded it as funny but embarrassing. “Oh Mum… Why do you always cry?” And this made me self-conscious, till, conditioned by their expectations, I’d be brimming up – and laughing too – on the last page of almost any book I read aloud, even ones which weren’t sad at all. I reckoned it was their fault for staring at me and making me worse. But it didn’t matter. I didn’t mind then, and I don’t mind now.

For, after all, how can it be a bad thing to let our children see how stories move us?

Published on September 07, 2012 00:13

August 30, 2012

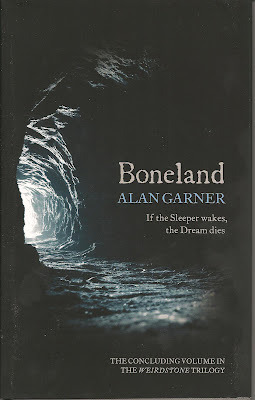

BONELAND by ALAN GARNER

I got interested in star-watching years ago, when I lived in a Yorkshire Dales village with no streetlights anywhere much nearer than Skipton, eleven miles away. On a clear night you could see as close to forever as makes no difference. Notes such as these filled my diary:

I got interested in star-watching years ago, when I lived in a Yorkshire Dales village with no streetlights anywhere much nearer than Skipton, eleven miles away. On a clear night you could see as close to forever as makes no difference. Notes such as these filled my diary:Jupiter setting as I went out about 11.30pm, so Arcturus the most conspicuous thing in the sky now. Standing under the flowering current bush I heard the Kirkby church clock chiming a mile and a quarter away. The tree by High Barn had stars in its leaves as bright as diamonds. Looked through binoculars at the Andromeda Spiral, a pale hazy blob, and wondered for the umpteenth time at how huge everything is – how could stars and planets and creatures all be packed into that faint ball of fuzz? C. looked too, and said it made him feel creepy, small and cold.

Or:

Woke up around 3 am, pushed up the window and looked out. Slap bang across from me was the whole constellation of Auriga, all risen above the hills like a sign, like a flambeau. The Pleiades glimmered secretly; below them shone Aldebaran in Taurus.

The Andromeda Spiral galaxy is one of our nearest celestial neighbours, and it is known as M31, or 'Messier 31', in the catalogue of 'deep sky objects' compiled by the 18th/19th century comet-hunter Charles Messier. In the same catalogue the Pleiades or Seven Sisters are designated 'M45'. Knowing this kind of thing helps, if you’re going to read and enjoy Alan Garner’s Boneland to the full, and explains why I found myself laughing at this exchange of mutual incomprehension between a fuddled Colin and a friendly taxi driver on page 4:

“What’s your job?”“Ah. Survey. M45. At the moment.”“It wants widening.”“I’m measuring it.”“Comes in handy sometimes.”“Yes?”“M6, M42, M45, M1.”“How do you mean?”“It misses the worst of the traffic.”

Colin is talking about galaxies; the taxi driver about British motorways. Each to his own. And maybe I’m lucky to be (a) British, and (b) interested in stars, but isn’t it great, for once, not to have stuff spelled out for you?

Already enchanted by this, and by the opening sequence of some mysterious paleolithic shaman puffing paint on to a cave wall, I settled down to enjoy.

Boneland isn’t a children’s book, and was never intended to be. And anyway, you can never step twice into the same river. If you’re expecting another book ‘like’ The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ or ‘The Moon of Gomrath’, you’ll be disappointed. Writers grow up, move on. But it’s fascinating to see Alan Garner pick up the threads of those two wonderful early books and weave something new. This is a grown-up story which would be impenetrable to children: but for adults it’s playful, tender, sometimes terrifying. It links nursery rhymes to the sound of bicycle wheels. It uses folktale rhythms and repetitions, incantatory story-telling, prose poetry, astronomy, geology, ornithology, jokes, and enough references to mythology and literature to keep the academics happy for years.

But it’s not written for academics! It’s also a great story. Colin, the Colin of the early books, is now a middle-aged professor working at the Jodrell Bank observatory in Cheshire (near Alderley Edge, of course) and ‘searching for his lost sister in the Pleiades’ as the blurb says. He’s in the middle of a breakdown: obsessive, hospitalised and seeking therapy. The parallel, interwoven narrative is that of another man, in the same place and in another time or maybe only another dimension, a Paleolithic shaman who views the same stars and imbues them with a different kind of meaning: with personality: with causality: with power. Both men (who may be the same man) search for meaning, for purpose, for the bringing-back of life from the dark. With the help of Doctor Meg Massey, an unconventional psychiatrist and psychotherapist, Colin begins to rediscover his lost past and face his fears.

There are all sorts of things going on. References to the Grail quest, the Fisher King, the medieval poem ‘Gawain and the Green Knight’ – the latter poem local to the north-west Midlands, of course. When Colin sharpens his axe, to chop wood; when the shaman goes up into the cold hills to find the mountain called the Mother, Garner paraphrases famous passages from the Gawain poem; and when the 21stcentury foreman of a group of workmen declares ‘I’m the governor of this gang’, it’s almost a direct quote. Surely Alan Garner is restating the depth and continuity of myth and legend and story in this small pocket of England. Is Colin the wizard of the Edge? Is he the Green Knight? The Wounded King? What did happen to Susan, and where is she? Where is the Morrigan? Is anything real?

It’s not a perfect book. There are things I found irritating. Not all of the dialogue works – does anyone really say things like: ‘Look here, Whisterfield. You’re an able fellow. You have the potential to expand our understanding of the cosmos’? And for me, some of the interchanges between Meg and Colin have a surreal, ‘Educating Rita’ quality as Meg – though a trained psychiatrist – does a teasing, wide-eyed-little-girl act to Colin’s reams of information. However, where Colin is confused, stubborn, frightened, pompous, almost an idiot savant, Meg is intuitive and powerful, half-leading, half-bullying him as he ventures into the darkness of his self – and the past. And there are many mysteries and many spine-tingling surprises in store.

In short, I think Boneland is wonderful. It’s allusive, elusive, tantalising, mystifying and evocative. It’s a poem, a song. It’s funny, it’s sad, and it made the hair rise on the back of my neck. It’s one to read – along with its two forerunners – again and again.

NB: You can read Ursula K Le Guin's Guardian review of BONELAND by clicking HERE: but beware: it DOES contain spoilers and I'm glad I didn't read it before reading the book itself.

Published on August 30, 2012 03:31

August 29, 2012

The House of Dreams

I'm guest-posting today over at Jenny Alexander's thoughtful, creative blog 'Writing in the House of Dreams'. Jenny asked me to share a recurrent dream I used to have as a child: one which I inherited (yes) from my mother and grandfather. I'd be interested to know if anyone else has a 'family dream'? If so, I hope it's a good one. This one wasn't. (Click HERE for the post.)

Published on August 29, 2012 01:15

August 24, 2012

THE BREMEN TOWN MUSICIANS

by Leslie Wilson

When my novel Last Train from Kummersdorf was published, my brother read it and then said to me: ‘It’s not at all a realistic novel, is it?’ And indeed, it isn’t, though I’m not sure how many people have noticed.

It is a novel very much in the German tradition: and at first glance it is close to other German novels and short stories about the Second World War and ‘Die Flucht’ – which means ‘The Flight’, meaning the escape from the advancing Russian army. Most of these are realist. But as I wrote it I knew I was in the German romantic/gothic tradition, like Storm’s Schimmelreiter (The Rider on the White Horse), or Gotthelf’s The Black Spider. Less unequivocally so, perhaps, than Grass’s Tin Drum. (A novel which made it hard, at first, to write Kummersdorf, because Grass seemed to have said it all so brilliantly.) But then I began to see that I had things to say that hadn’t already been said, and dared to go forward.

That tradition is deeply rooted in folklore, and so am I. Like Susan Price, I spent years and years of my childhood reading folktales from all over the world. But it was when I was doing my degree in German that I read the whole way through the three-volume 1900 jubilee edition of Grimm that I was lucky enough to be given in childhood – and, like Susan Price, found my mind going clicketty-clack, categorising the stories, seeing that certain basic plots came up over and over again, with variations – and once a motif from the Nibelungenlied, the medieval Lay of the Nibelungs, in The Two Brothers: the sword put between a man masquerading as his twin brother and his sister-in-law when they have to sleep together. Siegfried puts a sword between himself and Brünhilde when he beds her in the guise of his brother-in-law-to be, Gunther. Maybe the Nibelungenlied draws from popular folklore, maybe the folk story has picked up part of the epic. In any case, it was deeply important to me to read the collection then, one of those things that one knows one has to do, even if one doesn’t know why. What it taught me is what others have said before me: there are only a limited amount of plots. The other realisation was also important: that stories are interdependent and feed each other. When – many years later - I started to write Kummersdorf, I quickly realised the influence, in my story, of The Bremen Town Musicians.

The Brothers Grimm were undoubtedly motivated by a desire to establish an authentic ‘German’ voice; a project rooted in the dubious one of German unification by force, rather than through the liberal impulse of revolution. That hope was dashed in 1948. As for the ‘authentic German voice’, that was a stupid idea. Folktales are international; carried along trade routes, they flit from country to country. Some of the Grimm stories came from Perrault. Maybe nursemaids picked them up in the houses of the francophile German aristocracy and middle class, and took them back into their own humble homes to tell to their own children. At that point other motifs infiltrated them, which is why Aschenputtel is different from Cendrillon. The other thing that the Grimm brothers did was to edit the stories – but I am quite certain that they still retain much of the authentic vernacular voice.

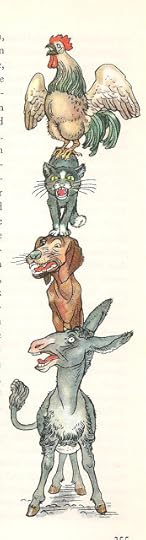

I think the value of myth and fairy stories is that they mitigate the dreadful things that happen to human beings. Stories of heroes, of magical rescues, of the world turned upside down, give us courage to face a harsh world. The savagery of the revenge sometimes taken expresses people’s deep inner anger; an anger too often bitten back in a world where injustice and callous exploitation were – and still are - rife. The Bremen Town Musicians is about old animals, worked-out, threatened with various brutal ends because they’re no use to their masters any longer. They find a robbers’ house in the forest and frighten the robbers away from it and their booty simply by making their various noises – music, according to them – so then they are able to live at their ease for the rest of their lives. I think the story reflects the reality of the lives of story-telling grandparents, who were similarly regarded as useless – except to keep the children quiet. It’s a story about Grey Power. Or just about the powerless who manage – just for once – to turn the tables. And, significantly, when the robber comes back to see if the band can repossess their house, the voice that finally terrorises him is that of the cockerel who he interprets as a judge’s voice, calling out: ‘Bring the rogue to me!’

I think the value of myth and fairy stories is that they mitigate the dreadful things that happen to human beings. Stories of heroes, of magical rescues, of the world turned upside down, give us courage to face a harsh world. The savagery of the revenge sometimes taken expresses people’s deep inner anger; an anger too often bitten back in a world where injustice and callous exploitation were – and still are - rife. The Bremen Town Musicians is about old animals, worked-out, threatened with various brutal ends because they’re no use to their masters any longer. They find a robbers’ house in the forest and frighten the robbers away from it and their booty simply by making their various noises – music, according to them – so then they are able to live at their ease for the rest of their lives. I think the story reflects the reality of the lives of story-telling grandparents, who were similarly regarded as useless – except to keep the children quiet. It’s a story about Grey Power. Or just about the powerless who manage – just for once – to turn the tables. And, significantly, when the robber comes back to see if the band can repossess their house, the voice that finally terrorises him is that of the cockerel who he interprets as a judge’s voice, calling out: ‘Bring the rogue to me!’

Last Train from Kummersdorf is about civilians, and civilians who end up facing the incoming army. As a child, I always noticed the value that’s placed in wartime on soldiers’ lives over those of civilians. I resented it, because from an early age I’d heard from my mother just what defeat means. When the soldiers are dead, it’s the old people, the youngsters and children who are in the front line. Many of the Russian soldiers entering Germany in 1945 behaved the way conquering soldiers have always done. They behaved that way even in the Slav countries they came to first, so it wasn’t, as many people have said, just a revenge-taking for the dreadful things the German soldiers had done in Russia. Members of the Red Army raped, tortured, murdered and looted, with Stalin’s blessing. The innocent suffered along with the guilty. ‘Deutsche Frau ist deutsche Frau,’ a Russian soldier said when it was pointed out to him that the woman he was about to rape was Jewish. ‘German woman is German woman.’ My mother got away from a Russian by the skin of her teeth, ran away into the forest and the mountains and almost died there. That, along with the expulsion of many of her family from their homes in Silesia, is the ‘core narrative’ I was working with.

If you sleep rough, it very quickly starts to do things to your perception of reality: dossers and refugees live a different kind of reality from ours, in our houses, where we can shut the door on danger. I think when you’re in constant danger of your life, then some fundamental, mythic perceptions probably kick in. My mother, wandering the mountains in April, was living out a fundamental folkloric story of pursuit, only it was Russian soldiers, rather than enraged witches, she was escaping from. Hanno and Effi, in Kummersdorf, are trying to escape from the Russians too, but they have a Quest, too: to get to the West, where the boy Hanno’s mother is, and where the girl Effi is firmly convinced she’ll find her father. The teenagers pick up other people, rag-tag refugees; it was at that point that I said to myself: ‘This story is like The Bremen Town Musicians!’

But my refugees don’t find the baddies in a house: the baddies are on the run, too, and the kids pick some of them up and have to schlepp them along willy-nilly; the old crazy doctor who’s murdered disabled children in the ‘euthanasia’ programme; the rabid Nazi police officer who nurses a strange hatred for the boy Hanno. But there’s someone else: the little man Sperling (which means sparrow) with his dog Cornelius and his magic cart which he makes over to the kids after a Russian air attack kills him. When the kids play a game with the railway tickets in the cart, when Effi teases the adults with the fantasy they’ve cooked up – when suddenly the other refugees start believing the alluring fantasy of a train that can carry them out of danger – this is story taking people over, altering their perceptions of reality. And the train itself, when it half-magically appears, becomes a location where the truth comes out about the refugees’ pasts. Though it’s no means of escape for them, so the story doesn’t end there.

My novel, like so many fairy-tales, and especially the Musicians, takes place in the German ‘Wald’, the forest, the location where so many German folk tales play off. I knew the German forest from an early age, though not the Brandenburg forest of the novel. My grandfather had a house on the eastern shore of the Rhine. My brother and I used to go off into the Wald and explore it, but it felt dangerous; full of wild boar for one thing, who might attack us in the breeding season. Once, when I was a baby, my mother was on her own in the house at night – my grandparents had gone out together – and she heard a snuffling and thumping against the door, a huge animal apparently trying to break in. She was terrified. In the morning, there was blood on the grass outside, and the adults realised it must have been a wounded boar. It wasn’t really a danger to us, of course, but the story of that inchoate menace in the night coming out of the Wald stayed with me. When the stags were rutting, the clash of their antlers echoed and filled the valley in front of the house; they were almost as loud as thunderclaps.

The road from Opa’s house led to a little clearing in the woods where a flame flickered, day and night. I was told that a child had been lost out there once, and its desperate mother promised the Virgin Mary that if her child was found, she’d set a flame there to burn to help other travellers who might be lost. The flame marked the place where the child was safely found. I don’t know if it’s still there. I can picture it now, at a place where two paths met, in a part of the forest planted with conifers; the dusty path scattered with needle-mess and resinous cones, and the dimness among the trees. Mirkwood. The forest went on and on, it seemed enormous. I knew the witches and wolves and robbers were in there; you only had to go far enough. And so it became part of my psyche and so I had to write about it.

Leslie Wilson grew up bilingual, the daughter of a German mother and an English father, and some of the events in her first YA book, ‘Last Train from Kummersdorf’ stem from her mother’s traumatic wartime experiences, from which, in part, her writing derives its emotional truth. Shortlisted for the Guardian Fiction Prize, the novel is set in 1945. On the run from the advancing Russian army, two young people, Effi and Hanno, become companions on the road, teaming up to defend and help each other from the many dangers they meet along the way. Leslie is additionally the author of two novels for adults: 'Malefice', a novel of the English witchhunt, published in 1991, and 'The Mountain of Immoderate Desires', which won the Southern Arts Prize in 1997. Her most recent young adult novel, 'Saving Rafael' (2009) was nominated for the Carnegie Medal and shortlisted for the Lancashire and the Southern Schools book awards. ‘Saving Rafael’ opens grimly in ‘Uckermark Girls’ Concentration Camp, Spring 1944’, where the heroine, Jenny, has been sent. She herself is not Jewish, but she’s in love with her long-term best friend Rafael, who is – and the book heartbreakingly and nail-bitingly describes her and her family’s increasingly desperate and forlorn attempt to protect their old friends and neighbours. I asked Leslie if she could see any fairytale motifs in this book too, and she answered that maybe it is a bit like the stories of girls who undergo hideous sufferings to save their enchanted lovers or husbands – like ‘East of the Sun and West of the Moon’. Illustrations:The Bremen Town Musicians: black and white illustration from book of Grimm's fairytales in Leslie Wilson's possession. Watercolour illustration by Ruth Koser-Michaels, from 'Marchen der Bruder Grimm' 1937, Droemer Knaur, in Katherine Langrish's possession.

[The translation of the German gothic script in the illustration is: "into the room, so that the windowpanes rattled. The robbers leapt up at the ghastly racket, and were convinced that a ghost was coming in: terrified, they ran out of the house into the forest. Now the four companions sat down at the table, helped themselves to what was left of the feast, and ate as if they were getting ready for a four weeks fast. When the four musicians had finished, the extinguished the light..."]

When my novel Last Train from Kummersdorf was published, my brother read it and then said to me: ‘It’s not at all a realistic novel, is it?’ And indeed, it isn’t, though I’m not sure how many people have noticed.

It is a novel very much in the German tradition: and at first glance it is close to other German novels and short stories about the Second World War and ‘Die Flucht’ – which means ‘The Flight’, meaning the escape from the advancing Russian army. Most of these are realist. But as I wrote it I knew I was in the German romantic/gothic tradition, like Storm’s Schimmelreiter (The Rider on the White Horse), or Gotthelf’s The Black Spider. Less unequivocally so, perhaps, than Grass’s Tin Drum. (A novel which made it hard, at first, to write Kummersdorf, because Grass seemed to have said it all so brilliantly.) But then I began to see that I had things to say that hadn’t already been said, and dared to go forward.

That tradition is deeply rooted in folklore, and so am I. Like Susan Price, I spent years and years of my childhood reading folktales from all over the world. But it was when I was doing my degree in German that I read the whole way through the three-volume 1900 jubilee edition of Grimm that I was lucky enough to be given in childhood – and, like Susan Price, found my mind going clicketty-clack, categorising the stories, seeing that certain basic plots came up over and over again, with variations – and once a motif from the Nibelungenlied, the medieval Lay of the Nibelungs, in The Two Brothers: the sword put between a man masquerading as his twin brother and his sister-in-law when they have to sleep together. Siegfried puts a sword between himself and Brünhilde when he beds her in the guise of his brother-in-law-to be, Gunther. Maybe the Nibelungenlied draws from popular folklore, maybe the folk story has picked up part of the epic. In any case, it was deeply important to me to read the collection then, one of those things that one knows one has to do, even if one doesn’t know why. What it taught me is what others have said before me: there are only a limited amount of plots. The other realisation was also important: that stories are interdependent and feed each other. When – many years later - I started to write Kummersdorf, I quickly realised the influence, in my story, of The Bremen Town Musicians.

The Brothers Grimm were undoubtedly motivated by a desire to establish an authentic ‘German’ voice; a project rooted in the dubious one of German unification by force, rather than through the liberal impulse of revolution. That hope was dashed in 1948. As for the ‘authentic German voice’, that was a stupid idea. Folktales are international; carried along trade routes, they flit from country to country. Some of the Grimm stories came from Perrault. Maybe nursemaids picked them up in the houses of the francophile German aristocracy and middle class, and took them back into their own humble homes to tell to their own children. At that point other motifs infiltrated them, which is why Aschenputtel is different from Cendrillon. The other thing that the Grimm brothers did was to edit the stories – but I am quite certain that they still retain much of the authentic vernacular voice.

I think the value of myth and fairy stories is that they mitigate the dreadful things that happen to human beings. Stories of heroes, of magical rescues, of the world turned upside down, give us courage to face a harsh world. The savagery of the revenge sometimes taken expresses people’s deep inner anger; an anger too often bitten back in a world where injustice and callous exploitation were – and still are - rife. The Bremen Town Musicians is about old animals, worked-out, threatened with various brutal ends because they’re no use to their masters any longer. They find a robbers’ house in the forest and frighten the robbers away from it and their booty simply by making their various noises – music, according to them – so then they are able to live at their ease for the rest of their lives. I think the story reflects the reality of the lives of story-telling grandparents, who were similarly regarded as useless – except to keep the children quiet. It’s a story about Grey Power. Or just about the powerless who manage – just for once – to turn the tables. And, significantly, when the robber comes back to see if the band can repossess their house, the voice that finally terrorises him is that of the cockerel who he interprets as a judge’s voice, calling out: ‘Bring the rogue to me!’

I think the value of myth and fairy stories is that they mitigate the dreadful things that happen to human beings. Stories of heroes, of magical rescues, of the world turned upside down, give us courage to face a harsh world. The savagery of the revenge sometimes taken expresses people’s deep inner anger; an anger too often bitten back in a world where injustice and callous exploitation were – and still are - rife. The Bremen Town Musicians is about old animals, worked-out, threatened with various brutal ends because they’re no use to their masters any longer. They find a robbers’ house in the forest and frighten the robbers away from it and their booty simply by making their various noises – music, according to them – so then they are able to live at their ease for the rest of their lives. I think the story reflects the reality of the lives of story-telling grandparents, who were similarly regarded as useless – except to keep the children quiet. It’s a story about Grey Power. Or just about the powerless who manage – just for once – to turn the tables. And, significantly, when the robber comes back to see if the band can repossess their house, the voice that finally terrorises him is that of the cockerel who he interprets as a judge’s voice, calling out: ‘Bring the rogue to me!’Last Train from Kummersdorf is about civilians, and civilians who end up facing the incoming army. As a child, I always noticed the value that’s placed in wartime on soldiers’ lives over those of civilians. I resented it, because from an early age I’d heard from my mother just what defeat means. When the soldiers are dead, it’s the old people, the youngsters and children who are in the front line. Many of the Russian soldiers entering Germany in 1945 behaved the way conquering soldiers have always done. They behaved that way even in the Slav countries they came to first, so it wasn’t, as many people have said, just a revenge-taking for the dreadful things the German soldiers had done in Russia. Members of the Red Army raped, tortured, murdered and looted, with Stalin’s blessing. The innocent suffered along with the guilty. ‘Deutsche Frau ist deutsche Frau,’ a Russian soldier said when it was pointed out to him that the woman he was about to rape was Jewish. ‘German woman is German woman.’ My mother got away from a Russian by the skin of her teeth, ran away into the forest and the mountains and almost died there. That, along with the expulsion of many of her family from their homes in Silesia, is the ‘core narrative’ I was working with.

If you sleep rough, it very quickly starts to do things to your perception of reality: dossers and refugees live a different kind of reality from ours, in our houses, where we can shut the door on danger. I think when you’re in constant danger of your life, then some fundamental, mythic perceptions probably kick in. My mother, wandering the mountains in April, was living out a fundamental folkloric story of pursuit, only it was Russian soldiers, rather than enraged witches, she was escaping from. Hanno and Effi, in Kummersdorf, are trying to escape from the Russians too, but they have a Quest, too: to get to the West, where the boy Hanno’s mother is, and where the girl Effi is firmly convinced she’ll find her father. The teenagers pick up other people, rag-tag refugees; it was at that point that I said to myself: ‘This story is like The Bremen Town Musicians!’

But my refugees don’t find the baddies in a house: the baddies are on the run, too, and the kids pick some of them up and have to schlepp them along willy-nilly; the old crazy doctor who’s murdered disabled children in the ‘euthanasia’ programme; the rabid Nazi police officer who nurses a strange hatred for the boy Hanno. But there’s someone else: the little man Sperling (which means sparrow) with his dog Cornelius and his magic cart which he makes over to the kids after a Russian air attack kills him. When the kids play a game with the railway tickets in the cart, when Effi teases the adults with the fantasy they’ve cooked up – when suddenly the other refugees start believing the alluring fantasy of a train that can carry them out of danger – this is story taking people over, altering their perceptions of reality. And the train itself, when it half-magically appears, becomes a location where the truth comes out about the refugees’ pasts. Though it’s no means of escape for them, so the story doesn’t end there.

My novel, like so many fairy-tales, and especially the Musicians, takes place in the German ‘Wald’, the forest, the location where so many German folk tales play off. I knew the German forest from an early age, though not the Brandenburg forest of the novel. My grandfather had a house on the eastern shore of the Rhine. My brother and I used to go off into the Wald and explore it, but it felt dangerous; full of wild boar for one thing, who might attack us in the breeding season. Once, when I was a baby, my mother was on her own in the house at night – my grandparents had gone out together – and she heard a snuffling and thumping against the door, a huge animal apparently trying to break in. She was terrified. In the morning, there was blood on the grass outside, and the adults realised it must have been a wounded boar. It wasn’t really a danger to us, of course, but the story of that inchoate menace in the night coming out of the Wald stayed with me. When the stags were rutting, the clash of their antlers echoed and filled the valley in front of the house; they were almost as loud as thunderclaps.

The road from Opa’s house led to a little clearing in the woods where a flame flickered, day and night. I was told that a child had been lost out there once, and its desperate mother promised the Virgin Mary that if her child was found, she’d set a flame there to burn to help other travellers who might be lost. The flame marked the place where the child was safely found. I don’t know if it’s still there. I can picture it now, at a place where two paths met, in a part of the forest planted with conifers; the dusty path scattered with needle-mess and resinous cones, and the dimness among the trees. Mirkwood. The forest went on and on, it seemed enormous. I knew the witches and wolves and robbers were in there; you only had to go far enough. And so it became part of my psyche and so I had to write about it.

Leslie Wilson grew up bilingual, the daughter of a German mother and an English father, and some of the events in her first YA book, ‘Last Train from Kummersdorf’ stem from her mother’s traumatic wartime experiences, from which, in part, her writing derives its emotional truth. Shortlisted for the Guardian Fiction Prize, the novel is set in 1945. On the run from the advancing Russian army, two young people, Effi and Hanno, become companions on the road, teaming up to defend and help each other from the many dangers they meet along the way. Leslie is additionally the author of two novels for adults: 'Malefice', a novel of the English witchhunt, published in 1991, and 'The Mountain of Immoderate Desires', which won the Southern Arts Prize in 1997. Her most recent young adult novel, 'Saving Rafael' (2009) was nominated for the Carnegie Medal and shortlisted for the Lancashire and the Southern Schools book awards. ‘Saving Rafael’ opens grimly in ‘Uckermark Girls’ Concentration Camp, Spring 1944’, where the heroine, Jenny, has been sent. She herself is not Jewish, but she’s in love with her long-term best friend Rafael, who is – and the book heartbreakingly and nail-bitingly describes her and her family’s increasingly desperate and forlorn attempt to protect their old friends and neighbours. I asked Leslie if she could see any fairytale motifs in this book too, and she answered that maybe it is a bit like the stories of girls who undergo hideous sufferings to save their enchanted lovers or husbands – like ‘East of the Sun and West of the Moon’. Illustrations:The Bremen Town Musicians: black and white illustration from book of Grimm's fairytales in Leslie Wilson's possession. Watercolour illustration by Ruth Koser-Michaels, from 'Marchen der Bruder Grimm' 1937, Droemer Knaur, in Katherine Langrish's possession.

[The translation of the German gothic script in the illustration is: "into the room, so that the windowpanes rattled. The robbers leapt up at the ghastly racket, and were convinced that a ghost was coming in: terrified, they ran out of the house into the forest. Now the four companions sat down at the table, helped themselves to what was left of the feast, and ate as if they were getting ready for a four weeks fast. When the four musicians had finished, the extinguished the light..."]

Published on August 24, 2012 00:49

August 21, 2012

'MUDDLE AND WIN: The Battle For Sally Jones' by John Dickinson

If I described this book as ‘The Screwtape Letters for children’ I would be both spot on and way, way off at the same time. Because even though it’s about a devil and an angel and their battle to possess, or at least influence, the soul of young Sally Jones, it’s not a religious book. And therein lies its strength. John Dickinson is too nuanced a writer to fall for a polarised good/evil view of morality. This is not a story about Sin. Perish the thought. Neither is it a story about Being Saved. It’s a story about the dark side of the mind – the soul, if you will – and the multifarious ways in which we manage to convince ourselves that we’re in the right and everyone else is being totally unreasonable. And it’s funny, and it’s scary, and it’s very, very sharp in its observations of human nature.

If I described this book as ‘The Screwtape Letters for children’ I would be both spot on and way, way off at the same time. Because even though it’s about a devil and an angel and their battle to possess, or at least influence, the soul of young Sally Jones, it’s not a religious book. And therein lies its strength. John Dickinson is too nuanced a writer to fall for a polarised good/evil view of morality. This is not a story about Sin. Perish the thought. Neither is it a story about Being Saved. It’s a story about the dark side of the mind – the soul, if you will – and the multifarious ways in which we manage to convince ourselves that we’re in the right and everyone else is being totally unreasonable. And it’s funny, and it’s scary, and it’s very, very sharp in its observations of human nature.Deep down – deep, deep down, Dickinson suggests – everyone has a dark and fiery place within them, accessible from a trapdoor in one of the backrooms of the mind:

There won’t be much light there, and there’ll be things scattered all over the floor. Most of it’s stuff you’ve always known about but don’t get out and look at too much. You start clearing it to one side. Never mind the dust. Never mind the smell. (Listen – even the best-kept minds have rooms like this.) When you find you’re shifting aside thoughts you would never, ever try to explain to anybody – and there will be some – then you’re in the right place.

Underneath it all there’ll be a trap door. …If it’s locked, you open it. You have the key, of course.

I love that sinister last line. Of course we do. And below the trap door is a dark void, and at the bottom of that – well, we don’t get anywhere near the bottom, all we get to see is the topmost brass towers of the city of Pandemonium (‘They like brass here’) from which the oddly loveable little imp Muddlespot – up till now merely one of Pandemonium’s cleaners – is despatched to do his best, or worst, to corrupt the incorruptible Sally Jones, a schoolgirl so Good that her LDC (or Lifetime Deed Counter) reads:

Lifetime Good Deeds: 3,971,570 Lifetime Bad Deeds: NIL nil NIL nil NIL nil NIL nil

Sally Jones is a poster girl for Heaven. Not only is she Good, she is Popular (except possibly with her twin sister Billie: no one likes to be shown up that much, do they?).

Because, if your phone was out of credit, you could borrow Sally’s. If you’d left your maths homework at school, you could call Sally and she would give you the questions. …Her allowance wasn’t great, but if you needed any of it, it was yours. She’d hear your lines for the school play. And when all was lost and the Head of Year was bearing down on you and your last alibi was blown, Sally would get you out of it. Somehow. Without even lying.

Not surprising, then, that the angelic squadrons scramble in her defence. And Angel Windleberry (‘no one watched more sleeplessly, praised more mightily or fought the good fight more fiercely’) is chosen to become Sally’s guardian angel and put Muddlespot to flight.

But the Battle for Sally Jones turns out to be a lot more complicated than either Muddle or Win could ever have anticipated. For one thing, Sally’s got her own strong views on things. Then there’s her sister Billie’s guardian angel and resident devil, who’ve … reached a certain understanding. There’s a war to be fought over a batch of muffins. There’s an amoral cat. And anyway, is it really good for Sally to be That Good? And if not, can Good sometimes be Bad?

If I had one tiny niggle with the book at all, it's the role of the fiend Corozin, Muddlespot's master. I'm not entirely sure how he fits into Sally's psyche, and he's so hands-off during most of the book that his appearance at the end (as arch tempter) feels something of a diabolus ex machina. But that's all it was, a niggle. It's a huge relief to come across such an intelligent, thought-provoking book for children. Give it to good readers of ten and up. And read it yourself. It's fast-moving, vivid and funny, there’s not a dull line in it, and I adored it. I think you will too.

Muddle and Win, by John Dickinson, will be published next month by David Fickling Books.

Published on August 21, 2012 00:00

August 17, 2012

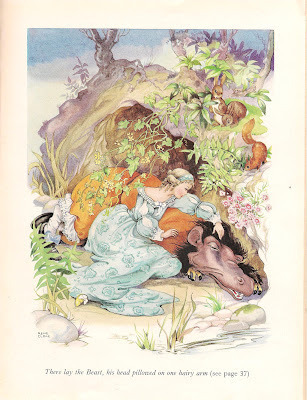

Beauty and the Beast

by Juliet Marillier

I’ve loved Beauty and the Beast ever since I discovered it in Andrew Lang’s Blue Fairy Book at the age of eight or so. As a child, I was captured by the magical elements of the story: the mysterious empty house with the meal ready on the table and the bed turned down for the weary traveller; the shock of the Beast’s first appearance; the mirror that allows Beauty to see far away; the cast of invisible retainers; the sixth sense that lets our heroine rush back to her dying Beast just in time to save his life. As a child I was untroubled by the fact that Beauty was so much the victim of her family’s poor judgement. I simply revelled in the spellbinding romance of the story. It was probably that tale, above all, that shaped me into a writer who puts a good love story in every novel!

All my books contain elements of traditional storytelling. I thank both my Celtic ancestry and a perceptive children’s librarian for providing me with a very early passion for myth, legend, fairytale and folklore. Of my twelve novels, three are loosely based on well known fairytales, and the others dip frequently into the cauldron of story that we all share, borrowing themes and motifs from its rich brew and, I hope, adding something new each time to the nourishing contents. I’ll write more later on my use of Beauty and the Beast as the framework for a gothic fantasy-romance for adults, Heart’s Blood (Roc, 2009.) First let’s look at the history of the fairytale itself.

According to fairytale scholar Jack Zipes, the literary development of Beauty and the Beast starts with the Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche, published by Roman writer Apuleius the second century. This story was revived in seventeenth century France, where it became immensely popular, inspiring various re-tellings including a ‘tragédie-ballet’ by Corneille and Molière.

Cupid and Psyche is a story about the perils of female curiosity, and belongs to an oral storytelling tradition featuring mysterious bridegrooms and inquisitive brides. Marry me, the young woman is told, share my bed, but don’t ever light the lamp after night falls. When the curious woman inevitably falls victim to temptation, she loses her husband and may or may not be allowed to win him back by performing a gruelling quest. East of the Sun and West of the Moon is a wonderful example of this kind of tale.

French writers of romances reworked the tale of Cupid and Psyche in various ways, usually incorporating magical transformations, wicked fairies and handsome princes. These tales had the dual function of entertainment and instruction. As with most re-tellings of traditional stories, whether oral or written, the new versions were tailored to their time, culture and readership. In the French romances, the emphasis shifts towards the female protagonist. She must discover the importance of keeping her word, and learn which virtues are most to be valued in a young woman. In addition, she learns that a true hero practises the qualities of courtesy, honour and self-restraint.

Gabrielle de Villeneuve’s elaborate, extended tale of Beauty and the Beast, published in 1740, was the model for most of the later versions. A simpler version, intended for a young audience, was written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont. Instead of Psyche, who lets her curiosity get the better of her common sense, we have Beauty, a model of daughterly loyalty, sweetness and self-denial. Jack Zipes tells us that in Mme de Villeneuve’s version, Beauty is ready to give up her claim to the Beast/Prince at the end of the story because her own origins are too humble to make her a fit wife for him. The fairies intervene and argue on her behalf, and then, in a real cop-out of an ending, we discover that Beauty is actually adopted, and a princess!

The story most of us are familiar with goes something like this. There’s a widowed merchant with three daughters. They’ve fallen on hard times, and have gone to live in the country where they run a small farm. The two elder daughters are vain and lazy, and spend all their time moaning about the loss of their wealth and status. The youngest daughter, Beauty, is not only lovely to look at, but a paragon of virtue who works hard and never complains despite the selfish behaviour of her sisters. Elder siblings in traditional stories are often shown as less than admirable, while the youngest is generally good and beautiful, though sometimes naive.

Father hears that one of his ships, thought to be lost at sea, has arrived safely in port. He heads off to retrieve the cargo. Before he goes he asks the daughters what gifts they want him to bring home for them. Sisters One and Two ask for jewels, silks and so on. Beauty asks her father to bring her a rose.

On his way home Father is caught in a storm in a forest and seeks shelter in a mysterious castle that seems deserted. Despite the emptiness, lights are blazing and he finds a delicious meal all set out, which he eats. He finds a cosy bed all prepared, and he sleeps. In the morning he wanders into the garden and finds roses blooming. Remembering Beauty’s request, he picks one, and a fearsome Beast appears to tell him his life is forfeit. If not his own, then that of one of his daughters. The Beast lets the father leave on condition that either he or one of his daughters returns within a certain period.

When she hears this, Beauty insists on returning with her father, since it was her request for a rose that caused the trouble. She persuades her father to leave her at the Beast’s castle, and the Beast sends Father home with a chest of riches.

Over the next few months, Beauty is provided with everything she wants, and the Beast comes to eat supper with her every evening. Once Beauty realises the Beast is not fattening her up to eat her, she befriends him, and realises over time that despite his hideous appearance, he is a courteous, thoughtful and charming companion. After some time, Beauty wants to visit her family and the Beast allows her to go for one week. Her sisters, however, conspire to keep her home for longer. They’re jealous of her fine clothes and her happiness, and they are hoping the Beast will get annoyed and devour her!

After ten days, Beauty dreams the Beast is lying in the garden of his castle, almost dead. She is stricken by remorse and realises she cares about him more than she realised. ‘It is neither handsome looks nor intelligence that makes a woman happy. It is good character, virtue, and kindness, and the Beast has all these good qualities.’ (Mme Leprince de Beaumont.)

Beauty rushes back to the castle, finds her dream was indeed true, splashes the Beast’s face with water and tells him she loves him. The Beast disappears, to be replaced by a prince ‘more handsome than Eros himself.’ He explains that Beauty has just undone a wicked witch’s spell, which prevented him from revealing either his looks or his true intelligence until a girl came along who would ‘allow the goodness of my character to touch you.’ A good fairy praises Beauty for preferring virtue over beauty and wit. Beauty and her prince are married, and the two sisters are turned into statues that will stand one at each side of the castle doors until they learn to recognise their faults.

Maybe this tale has its origins in Cupid and Psyche, but the Greek myth’s theme of feminine curiosity has vanished completely from the Beauty and the Beast stories of Mme de Villeneuve and Mme Leprince de Beaumont. The story is no longer about a woman’s inability to respect her lover’s secrets, but has become a tale of virtue and self-denial rewarded; a lesson in feminine behaviour, eighteenth century style. Indeed, reading the Mme de Beaumont version today I find myself rather surprised that I still love the story! Of course, the wonderful magical elements remain, even if the moral lesson is somewhat difficult for a contemporary readership to swallow.

When I used Beauty and the Beast as a framework for my adult novel, Heart’s Blood, I saw the theme of the story as acceptance: learning to accept others with all their flaws, both physical and non-physical; and learning to accept, love and forgive yourself, no matter what your weaknesses and faults. I altered various elements of the story, notably to make my Beauty a less passive person. In my story, both principal characters carry a weight of past trouble. Anluan (Beast) has suffered a stroke in childhood, losing full use of one arm and leg, and has fallen into depression after various family crises. He sees himself as crippled, weak and impotent. Caitrin (Beauty) is on the run from abusive relatives, and is barely holding herself together after a breakdown. So we have a pair of wary, damaged protagonists, each of whom must learn self-acceptance before he/she can reach out to the other. Together they must face an external challenge of massive proportions, as well as confronting their personal demons.

Anluan does not provide a splendid castle, beautiful clothing and sumptuous meals for Caitrin, but he does provide the two things she needs most: a safe place to stay, and paid work in the craft she loves (she’s a scribe.) Caitrin is neither a great beauty nor a paragon of feminine self-denial. Her sense of self-worth has taken a battering. But she has one virtue that allows her to make a difference: she sees every individual as worthy of love, no matter how flawed. In reclaiming others, she finds herself.

I ditched the wicked fairy’s curse and the magical transformation from beast to prince. I’ve always disliked stories in which the hero or heroine must become physically perfect (and wealthy / noble) before the happy ending can occur. For me, it is inner beauty that counts, and the knowledge that everyone is worthy of love. So my Beast has a disability at the start, and he still has it at the end. But by the end, it no longer matters.

I did keep the parts of Beauty and the Beast that I so loved in childhood. Heart’s Blood has a forbidden garden and a rare flower; it has a cast of unusual retainers; it has magic mirrors; it has a visit home and a precipitate return to face a life-and-death crisis. It also has ghosts, Irish history, a library full of ancient documents and a little occult magic. Beauty and the Beast it isn’t. But the strong old bones of my favourite fairytale are there throughout, giving my story its true heart.

And that’s what is so marvellous about fairytales. They’re as ancient as the hills, but they never grow old. As society and culture change, as our world becomes a place Apuleius and Mme Leprince de Beaumont could never have dreamed possible, the wisdom of those tales remains relevant to our lives. Because, of course, the stories change with us. We tell them and re-tell them, and they morph and grow and stretch to fit the framework of our time and culture, just as they did when they were told around the fire after dark in times long past. In this high-speed technological age, an age in which 140 characters are deemed sufficient to transmit a meaningful message, these stories still have much to teach us. We would do well to listen.

Juliet Marillier was born and brought up in Dunedin, New Zealand, and now lives in Western Australia. Her books have won many awards, including the Aurealis (three times) the Sir Julius Vogel Award, and France’s Prix Imaginales. She is a member of the druid order OBOD (the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids), and owns to ‘a lifelong love of traditional stories’. She lives in a hundred year old cottage which she shares with a small pack of waifs and strays.

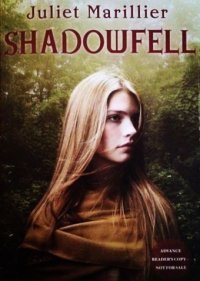

Respect, courtesy, courage – the strength of sisterly love and family ties – and a strong dose of the attractions and wild dangers of the Otherworld and the woods. These seem to be some of the recurrent themes of Juliet’s work. And her heroines – Jena of ‘Wildwood Dancing’, Caitrin of ‘Heart’s Blood’ – are intelligent, hardworking, responsible, and brave. They may live in apparently isolated villages or castles, they may enjoy dancing with faerie princes, but they belong to the wider world, they acknowledge links of trade and commerce. They value education, the chance to travel and work. They are, in the best sense, civilized. Juliet's latest book for young adults is Shadowfell, the first in a three-book series. Visit Juliet's website to find out more: http://www.julietmarillier.com/books/shadowfell.html or order from Amazon - you can do this via the Steel Thistles link, above, if you'd like to help this blog!

Respect, courtesy, courage – the strength of sisterly love and family ties – and a strong dose of the attractions and wild dangers of the Otherworld and the woods. These seem to be some of the recurrent themes of Juliet’s work. And her heroines – Jena of ‘Wildwood Dancing’, Caitrin of ‘Heart’s Blood’ – are intelligent, hardworking, responsible, and brave. They may live in apparently isolated villages or castles, they may enjoy dancing with faerie princes, but they belong to the wider world, they acknowledge links of trade and commerce. They value education, the chance to travel and work. They are, in the best sense, civilized. Juliet's latest book for young adults is Shadowfell, the first in a three-book series. Visit Juliet's website to find out more: http://www.julietmarillier.com/books/shadowfell.html or order from Amazon - you can do this via the Steel Thistles link, above, if you'd like to help this blog!

Picture credits: Beauty and the Beast by Walter Crane

Beauty and the Beast by Rene Cloke

I’ve loved Beauty and the Beast ever since I discovered it in Andrew Lang’s Blue Fairy Book at the age of eight or so. As a child, I was captured by the magical elements of the story: the mysterious empty house with the meal ready on the table and the bed turned down for the weary traveller; the shock of the Beast’s first appearance; the mirror that allows Beauty to see far away; the cast of invisible retainers; the sixth sense that lets our heroine rush back to her dying Beast just in time to save his life. As a child I was untroubled by the fact that Beauty was so much the victim of her family’s poor judgement. I simply revelled in the spellbinding romance of the story. It was probably that tale, above all, that shaped me into a writer who puts a good love story in every novel!

All my books contain elements of traditional storytelling. I thank both my Celtic ancestry and a perceptive children’s librarian for providing me with a very early passion for myth, legend, fairytale and folklore. Of my twelve novels, three are loosely based on well known fairytales, and the others dip frequently into the cauldron of story that we all share, borrowing themes and motifs from its rich brew and, I hope, adding something new each time to the nourishing contents. I’ll write more later on my use of Beauty and the Beast as the framework for a gothic fantasy-romance for adults, Heart’s Blood (Roc, 2009.) First let’s look at the history of the fairytale itself.

According to fairytale scholar Jack Zipes, the literary development of Beauty and the Beast starts with the Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche, published by Roman writer Apuleius the second century. This story was revived in seventeenth century France, where it became immensely popular, inspiring various re-tellings including a ‘tragédie-ballet’ by Corneille and Molière.

Cupid and Psyche is a story about the perils of female curiosity, and belongs to an oral storytelling tradition featuring mysterious bridegrooms and inquisitive brides. Marry me, the young woman is told, share my bed, but don’t ever light the lamp after night falls. When the curious woman inevitably falls victim to temptation, she loses her husband and may or may not be allowed to win him back by performing a gruelling quest. East of the Sun and West of the Moon is a wonderful example of this kind of tale.

French writers of romances reworked the tale of Cupid and Psyche in various ways, usually incorporating magical transformations, wicked fairies and handsome princes. These tales had the dual function of entertainment and instruction. As with most re-tellings of traditional stories, whether oral or written, the new versions were tailored to their time, culture and readership. In the French romances, the emphasis shifts towards the female protagonist. She must discover the importance of keeping her word, and learn which virtues are most to be valued in a young woman. In addition, she learns that a true hero practises the qualities of courtesy, honour and self-restraint.

Gabrielle de Villeneuve’s elaborate, extended tale of Beauty and the Beast, published in 1740, was the model for most of the later versions. A simpler version, intended for a young audience, was written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont. Instead of Psyche, who lets her curiosity get the better of her common sense, we have Beauty, a model of daughterly loyalty, sweetness and self-denial. Jack Zipes tells us that in Mme de Villeneuve’s version, Beauty is ready to give up her claim to the Beast/Prince at the end of the story because her own origins are too humble to make her a fit wife for him. The fairies intervene and argue on her behalf, and then, in a real cop-out of an ending, we discover that Beauty is actually adopted, and a princess!

The story most of us are familiar with goes something like this. There’s a widowed merchant with three daughters. They’ve fallen on hard times, and have gone to live in the country where they run a small farm. The two elder daughters are vain and lazy, and spend all their time moaning about the loss of their wealth and status. The youngest daughter, Beauty, is not only lovely to look at, but a paragon of virtue who works hard and never complains despite the selfish behaviour of her sisters. Elder siblings in traditional stories are often shown as less than admirable, while the youngest is generally good and beautiful, though sometimes naive.