Katherine Langrish's Blog, page 32

October 26, 2012

Dick Whittington and His Cat: (or The Magic of Cats)

by Nick Green

Turn again, Whittington, Lord Mayor of London!

Turn again, Whittington, thrice Mayor of London!

Is ‘Dick Whittington and his Cat’ really a fairytale? I’m going to call it one. Even though there is no actual magic (but see below), most of the ingredients are there: the poor and naive youth, the quest, the hardship, and at least a semi-supernatural element in the prophecy of the Bow Bells, calling the young Whittington back from Highgate Hill. I would argue that ‘Dick Whittington’ is not just a fairytale, but a particularly interesting one, being the only one (to my knowledge) that features a real person.

The historical Richard Whittington, of course, was Lord Mayor a total of four times (but legend ignores that as it doesn’t scan). Also, he was never particularly poor, and no-one knows if he really kept a cat. According to my diligent academic research (Wikipedia), the story’s origins lie further back, in a Persian folktale of a youth and his cat, onto which the legend of Whittington was later grafted. We can only guess the reason for this, but by all accounts Richard W was an all-round good egg and probably deserved it.

DW and C (as I shall write henceforth) is a simple enough yarn. A young lad comes to London seeking his fortune, following a rumour that the streets are paved with gold. Of course, they aren’t, and he ends up as a scullery boy. But his master is a merchant, and offers a place on his ship for anything that Dick might want to sell. All Dick has is his beloved cat, so reluctantly he sends that. Then, despairing of his fortune and missing his cat, Dick runs away, only to be checked on the edge of the city by the calling of the Bow Bells, who seem to be foretelling his future. He will become Lord Mayor of London, not once, but three times. Dick turns back, and arrives at his master’s house to astonishing news. The King of Barbary (whose kingdom is plagued by rats and mice) has bought his cat for a huge sum of gold. Dick’s fortune in made, and his destiny set in motion.

It’s a heartwarming story, but what makes it a fairytale? Someone being elected to high office three times isn’t a fairytale – that’s Margaret Thatcher. Even the prophetic bells aren’t really enough to elevate this story to the level of fairytale. There has to be another element that makes it so enduring.

Let’s face it. It’s the cat.

Think of the story of DW and C, and it’s always the same image: the youth treading the roads with his belongings in a sack on a stick, and a cat trotting faithfully beside him. If that animal were a dog, you’d have no story. ‘Dog follows human’ is not news. ‘Cat walks with human’ is the stuff of legend (unless your name is Jackie Morris). And the cat is what people remember. I mentioned before that no cats are recorded in the life of the historical Richard Whittington – and yet the creature still keeps popping up in tantalising glimpses, much as you’d expect a cat to do. In his will, Whittington ordered the rebuilding of Newgate Prison, and over one of the gates you could find the carving of a cat. Later, in 1572, Whittington’s heirs presented a chariot with a carved cat to the Merchants’ Guild. And in front of the Whittington Hospital, on Highgate Hill where Dick was said to have turned around, the cat keeps watch in the form of a statue. Despite all his philanthropy and good works – not to mention his real, provable existence – Whittington’s perhaps-mythical cat has effortlessly outlasted him. It’s not fair, is it?

In the story, it’s the cat that fills the role normally occupied in a fairytale by magic. It manages this even though it does nothing extraordinary – it doesn’t talk or dress up like the animal in Puss In Boots, it just goes around being a very good mouser and Dick Whittington’s dearest friend. In short, it does what any cat does. Because what a cat does, is magic.

This idea is at the heart of my own series of books, 'The Cat Kin'. In this, a group of London children join a class where they learn to move, see, hear and fight like cats. The art of ‘pashki’ is entirely my invention, but such is the universal appeal and mystery of cats that many readers ask if pashki is in fact real, or based in reality. Indeed, if you search the web, you can find claims that it is (and I didn’t put them there). Like Whittington’s cat, pashki seems to want to have a life of its own. Cats, for whatever reason, continue to exert their mystical fascination over us human beings.

One final reason why I love the story of Dick Whittington and his Cat, is that it’s a great parable for an aspiring writer. Dick follows a bright dream initially, only to be bitterly disappointed, giving up and turning away from it. And then, when all seems lost, he is called back to his struggle with the promise of a great reward – a threefold reward. And since I’m just now publishing the third book in the Cat Kin trilogy, you could say that this ending rings a bell for me too.

It was difficult to get Nick Green to tell me enough about himself for me to make a decent go of introducing him. I suspect him of being the kind of guy who refuses to part with information even when tied to the chair in the underground room, with the water rising around him and the candle-flame slowly burning through the cord holding the anvil suspended over his head. Out of sheer bloody-mindedness, no doubt.

At any rate, after applying a good deal of pressure I managed to extract only this: Nick is the second oldest and second tallest of four brothers, and the only one who isn’t ginger. It was while working for a children’s book club that he made the rash decision to start writing books as well as selling them. He read English at Edinburgh University, and now lives in Hertford with his wife and an itinerant population of cats.

Fortunately, I have other sources of information. I first heard of Nick’s debut novel ‘ The Cat Kin’ because it was news. Nick self-published the book believing in its worth: and he was absolutely right. After it was reviewed in The Times by Amanda Craig, who called it ‘a gripping adventure’, it was bought by Faber & Faber. Nick was writing the sequel, there was going to be a trilogy, and everyone seemed to be talking about it. What brilliant success! I whizzed out and bought a copy… and was entranced.

It’s a classic children’s adventure story with a fantasy/sci-fi twist: Two inner-city kids, Ben and Tiffany, each living tough lives, join an after-school gym class run by a strange woman called Mrs Powell who teaches the lost Ancient Egyptian art of ‘pashki’ – moving and sensing like a cat. Soon Ben, Tiffany and the rest of their class are leaping over London’s rooftops, slipping near-invisibly through the streets – and about to need all nine of their new lives as they discover the very dark deeds taking place in the old factory with the chimney like a wizard’s tower, visible from Ben’s apartment block.

And there was a dark side to the success story of Nick’s publication, too. Despite many good reviews, despite the fact that by this time Nick had written the sequel, Faber & Faber decided not, after all, to go ahead with publishing this second volume, ‘Cat’s Paw’. A crushing blow.

Bloodied but unbowed, Nick decided that this left him with only one thing to do – self-publish ‘Cat’s Paw’, and be damned to 'em. Which he did. And lo! in the best of fairytale traditions courage and tenacity, allied to faith and talent, paid off. ‘The Cat Kin’ was republished by Strident Publishing along with its sequel ‘ Cat’s Paw’, and the final book of the trilogy, 'Cat's Cradle' is being published this very Hallowe'en. I'm really looking forward to reading it.

Picture credits:

Nick Green

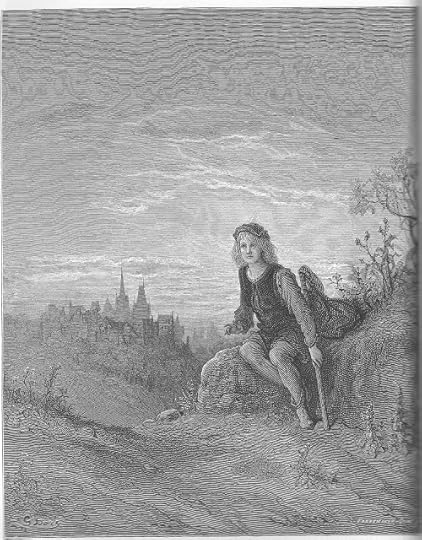

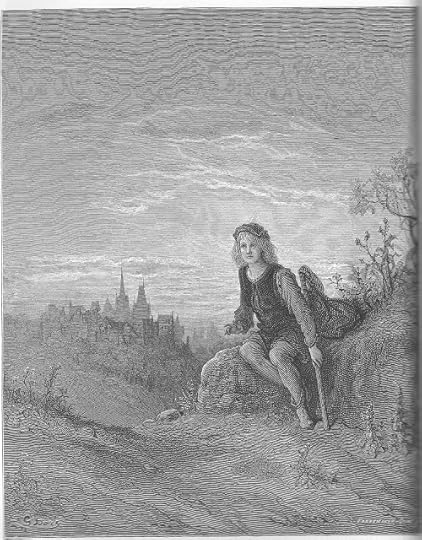

Dick Whittington on Highgate Hill: by Gustave Doré: 'London, A Pilgrimage'

The Dick Whittington Stone at Highgate

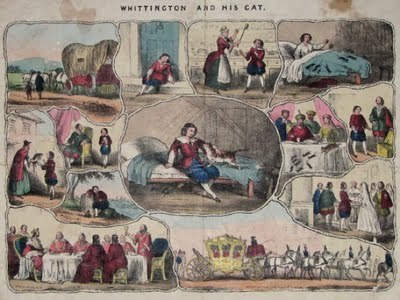

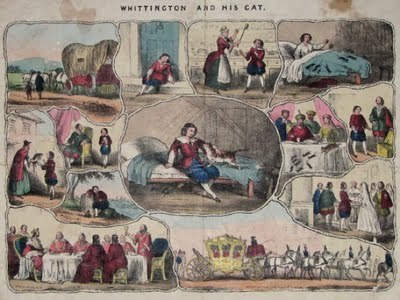

Whittington and His Cat: mid 19th century print, courtesy of SpitalfieldsLife (where you can find the story of Blackie, the last cat of Spitalfields Market).

Turn again, Whittington, Lord Mayor of London!

Turn again, Whittington, thrice Mayor of London!

Is ‘Dick Whittington and his Cat’ really a fairytale? I’m going to call it one. Even though there is no actual magic (but see below), most of the ingredients are there: the poor and naive youth, the quest, the hardship, and at least a semi-supernatural element in the prophecy of the Bow Bells, calling the young Whittington back from Highgate Hill. I would argue that ‘Dick Whittington’ is not just a fairytale, but a particularly interesting one, being the only one (to my knowledge) that features a real person.

The historical Richard Whittington, of course, was Lord Mayor a total of four times (but legend ignores that as it doesn’t scan). Also, he was never particularly poor, and no-one knows if he really kept a cat. According to my diligent academic research (Wikipedia), the story’s origins lie further back, in a Persian folktale of a youth and his cat, onto which the legend of Whittington was later grafted. We can only guess the reason for this, but by all accounts Richard W was an all-round good egg and probably deserved it.

DW and C (as I shall write henceforth) is a simple enough yarn. A young lad comes to London seeking his fortune, following a rumour that the streets are paved with gold. Of course, they aren’t, and he ends up as a scullery boy. But his master is a merchant, and offers a place on his ship for anything that Dick might want to sell. All Dick has is his beloved cat, so reluctantly he sends that. Then, despairing of his fortune and missing his cat, Dick runs away, only to be checked on the edge of the city by the calling of the Bow Bells, who seem to be foretelling his future. He will become Lord Mayor of London, not once, but three times. Dick turns back, and arrives at his master’s house to astonishing news. The King of Barbary (whose kingdom is plagued by rats and mice) has bought his cat for a huge sum of gold. Dick’s fortune in made, and his destiny set in motion.

It’s a heartwarming story, but what makes it a fairytale? Someone being elected to high office three times isn’t a fairytale – that’s Margaret Thatcher. Even the prophetic bells aren’t really enough to elevate this story to the level of fairytale. There has to be another element that makes it so enduring.

Let’s face it. It’s the cat.

Think of the story of DW and C, and it’s always the same image: the youth treading the roads with his belongings in a sack on a stick, and a cat trotting faithfully beside him. If that animal were a dog, you’d have no story. ‘Dog follows human’ is not news. ‘Cat walks with human’ is the stuff of legend (unless your name is Jackie Morris). And the cat is what people remember. I mentioned before that no cats are recorded in the life of the historical Richard Whittington – and yet the creature still keeps popping up in tantalising glimpses, much as you’d expect a cat to do. In his will, Whittington ordered the rebuilding of Newgate Prison, and over one of the gates you could find the carving of a cat. Later, in 1572, Whittington’s heirs presented a chariot with a carved cat to the Merchants’ Guild. And in front of the Whittington Hospital, on Highgate Hill where Dick was said to have turned around, the cat keeps watch in the form of a statue. Despite all his philanthropy and good works – not to mention his real, provable existence – Whittington’s perhaps-mythical cat has effortlessly outlasted him. It’s not fair, is it?

In the story, it’s the cat that fills the role normally occupied in a fairytale by magic. It manages this even though it does nothing extraordinary – it doesn’t talk or dress up like the animal in Puss In Boots, it just goes around being a very good mouser and Dick Whittington’s dearest friend. In short, it does what any cat does. Because what a cat does, is magic.

This idea is at the heart of my own series of books, 'The Cat Kin'. In this, a group of London children join a class where they learn to move, see, hear and fight like cats. The art of ‘pashki’ is entirely my invention, but such is the universal appeal and mystery of cats that many readers ask if pashki is in fact real, or based in reality. Indeed, if you search the web, you can find claims that it is (and I didn’t put them there). Like Whittington’s cat, pashki seems to want to have a life of its own. Cats, for whatever reason, continue to exert their mystical fascination over us human beings.

One final reason why I love the story of Dick Whittington and his Cat, is that it’s a great parable for an aspiring writer. Dick follows a bright dream initially, only to be bitterly disappointed, giving up and turning away from it. And then, when all seems lost, he is called back to his struggle with the promise of a great reward – a threefold reward. And since I’m just now publishing the third book in the Cat Kin trilogy, you could say that this ending rings a bell for me too.

It was difficult to get Nick Green to tell me enough about himself for me to make a decent go of introducing him. I suspect him of being the kind of guy who refuses to part with information even when tied to the chair in the underground room, with the water rising around him and the candle-flame slowly burning through the cord holding the anvil suspended over his head. Out of sheer bloody-mindedness, no doubt.

At any rate, after applying a good deal of pressure I managed to extract only this: Nick is the second oldest and second tallest of four brothers, and the only one who isn’t ginger. It was while working for a children’s book club that he made the rash decision to start writing books as well as selling them. He read English at Edinburgh University, and now lives in Hertford with his wife and an itinerant population of cats.

Fortunately, I have other sources of information. I first heard of Nick’s debut novel ‘ The Cat Kin’ because it was news. Nick self-published the book believing in its worth: and he was absolutely right. After it was reviewed in The Times by Amanda Craig, who called it ‘a gripping adventure’, it was bought by Faber & Faber. Nick was writing the sequel, there was going to be a trilogy, and everyone seemed to be talking about it. What brilliant success! I whizzed out and bought a copy… and was entranced.

It’s a classic children’s adventure story with a fantasy/sci-fi twist: Two inner-city kids, Ben and Tiffany, each living tough lives, join an after-school gym class run by a strange woman called Mrs Powell who teaches the lost Ancient Egyptian art of ‘pashki’ – moving and sensing like a cat. Soon Ben, Tiffany and the rest of their class are leaping over London’s rooftops, slipping near-invisibly through the streets – and about to need all nine of their new lives as they discover the very dark deeds taking place in the old factory with the chimney like a wizard’s tower, visible from Ben’s apartment block.

And there was a dark side to the success story of Nick’s publication, too. Despite many good reviews, despite the fact that by this time Nick had written the sequel, Faber & Faber decided not, after all, to go ahead with publishing this second volume, ‘Cat’s Paw’. A crushing blow.

Bloodied but unbowed, Nick decided that this left him with only one thing to do – self-publish ‘Cat’s Paw’, and be damned to 'em. Which he did. And lo! in the best of fairytale traditions courage and tenacity, allied to faith and talent, paid off. ‘The Cat Kin’ was republished by Strident Publishing along with its sequel ‘ Cat’s Paw’, and the final book of the trilogy, 'Cat's Cradle' is being published this very Hallowe'en. I'm really looking forward to reading it.

Picture credits:

Nick Green

Dick Whittington on Highgate Hill: by Gustave Doré: 'London, A Pilgrimage'

The Dick Whittington Stone at Highgate

Whittington and His Cat: mid 19th century print, courtesy of SpitalfieldsLife (where you can find the story of Blackie, the last cat of Spitalfields Market).

Published on October 26, 2012 06:24

October 23, 2012

Folklore Snippets: The Silver Cup

The Silver Cup from Dagberg Daas

From Scandinavian Folklore, ed William Craigie, 1896

Here’s a version of an old tale I used in ‘Troll Fell’, although for my version the cup was golden, and my troll girl was rather more attractive. ( I love the practical but horrific way the 'berg-woman' deals with her long, drooping breasts.) A ‘berg-man’ is a mound dweller, hill-man, elf or troll.

In Dagberg Daas there formerly lived a berg-man with his family. It happened once that a man who came riding past there took it into his head to ask the berg-woman for a little to drink. She went to get some for him, but her husband bade her take it out of the poisoned barrel. The traveller heard all this, however, and when the berg-woman handed him the cup with the drink, he threw the contents over his shoulder and rode off with the cup in his hand, as fast as his horse could gallop. The berg-woman threw her breasts over her shoulders, and ran after him as hard as she could. (The man rode off over some ploughed land where she had difficulty in following him, as she had to keep to the line of the furrows.) When he reached the spot where Karup Stream crosses the road from Viborg to Holtebro, she was so near him that she snapped a hook (hage) off the horse’s shoe, and therefore the place has been called Hagebro ever since. She could not cross the running water, and so the man was saved. It was seen afterwards that some drops of the liquor had fallen on the horse’s loins and taken off both hide and hair.

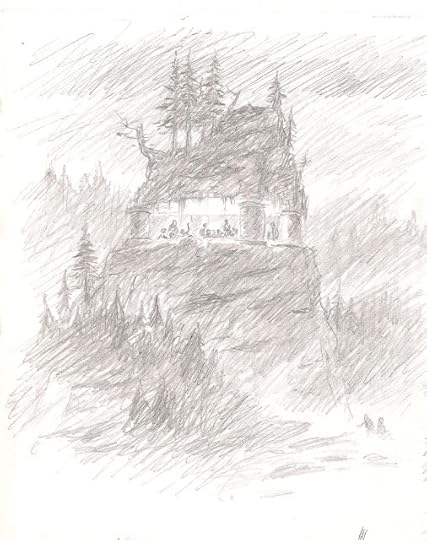

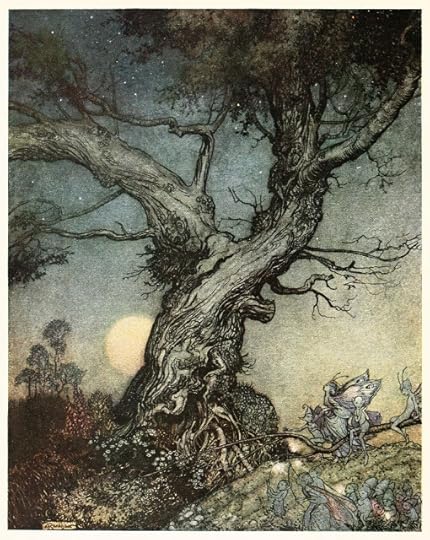

'Troll Fell' by David Wyatt

'Troll Fell' by David WyattIn 'Troll Fell' , Ralf tells the tale thus:

I was halfway over Troll Fell, tied and wet and weary, when I saw a bright light glowing from the top of the crag, and heard snatches of music gusting on the wind. I turned the pony off the road and kicked him into a trop up the hillside. I was in one of our own fields, the high one called the Stonemeadow. At the top of the slope I could hardly believe my eyes. The whole rocky summit of the hill had been lifted up, like a great stone lid! It was resting on four stout red pillars. The space underneath was shining with golden light and there were scores, maybe hundreds of trolls, skipping and dancing.

But the pony shied. I'd been so busy staring, I hadn't noticed this troll girl creeping up on me till she popped up right by the pony's shoulder. She held out a beautiful golden cup filled to the brim with something steaming hot - spiced ale I thought it was, and I tool it gratefully from her, cold and wet as I was.

Just before I gulped it down I noticed the look on her face. There was a gleam in her slanting eyes, a wicked sparkle! And her ears, her hairy, pointed ears, twitched forward. I saw she was up to no good!

So I lifted the cup, pretending to sip. Then I jerked the whole drink out over my shoulder. It splashed out smoking, some on to the ground and some on to the pony's tail, where it singed off half his hair! There's an awful yell from the troll girl, and the next thing the pony and I are off down the hill, galloping for our lives. I've still got the golden cup on one hand - and half the trolls of Troll Fell are tearing after us!

I had one chance. At the tall stone called the Finger, I turned off the road on to the big ploughed field above the mill. The pony could go quicker over the soft ground, you see, but the trolls found it heavy going across the furrows. I got to the mill stream ahead off them, jumped off and dragged the pony through the water. I was safe! The trolls couldn't follow me over the brook. They were spitting like cats and hissing like kettles. They threw stones and clods at me, but it was nearly dawn and off they scuttled back up the hillside. And I heard - no, I felt, through the soles of my feet, a sort of far-off grating shudder as the top of Troll Fell sank into its place again.

[Troll Fell, HarperCollins, 2004]

Picture credit: 'Troll Fell': unpublished illustration by David Wyatt. Copyright David Wyatt 2004

Published on October 23, 2012 02:10

October 19, 2012

Wayland's Smithy: a tangle of tales...

by Penny Dolan

Wayland's Smithy

Wayland's Smithy

All that was needed, so people said, was a single coin placed on a stone beside your tethered horse. Have faith, leave the horse there all night and when you came back next morning, your steed would be newly shod and the coin gone.

Though the nights of magical shoeing are surely long past, the ancient burial mound known as Wayland’s Smithy is still there on the shoulder of chalk downland, and the place with its tangled tale, haunts me.

I first saw the Smithy on a day so wet that froglets skittered from the path into overfull ditches and milky water ran down the cracks in the chalky clay.

The rain gods had only paused. By the time we had reached the crest of the ridge, a downpour had began. Thunder rolled around the hills and as we approached Wayland’s Smithy, the huge, dark clouds above were lit with streaks of lightning.

The long barrow lies off the track. We pushed through wet bushes and came to it, covered in grass and surrounded by grove of trees. Several ancient stones formed the gateway.

With the storm raging, the moment felt as if the past was only a shadow away. It was impossible not to think of the many feet that had passed along the Ridgeway and made the path, with or without horses to be shod. Did they all wonder at the mysterious mound or the strange white horse* spread across the hillside nearby? Did they seek shelter in the small wood?

However, the helpful smith of the legend does not match entirely happily with the Norse version of Wayland the Smith.

Wayland, or Volund, had been apprenticed to the dwarves of the Icelandic Mountains, He was one of the three sons of Wade, the king of the Finns. Out hunting, the brothers found three beautiful swan maidens, seized their feathered robes, and made them their wives. When the three sisters discovered their hidden feathers again, they flew away to freedom.

The two older brothers went searching for their wives, but the desolate Wayland stayed working at his smithy, sure that his beloved wife would return for the golden ring he was keeping for her and all the other treasures he was creating.

Soon rich men grew greedy for Wayland’s skills, King Niduth of Sweden more than any. Wayland was lured to his castle, crippled, imprisoned on an island and made to forge endless objects for the king. So dazzling were the treasures and so great the family’s pride that they forgot to be wary of their prisoner.

The two princes visited Wayland, who treated them kindly until they mocked him. Enraged, he beheaded them both and fashioned a set of dreadful gifts for the royal parents. The princely skulls became golden goblets, the eyes glittering gems from their eyes, and their pearly white teeth made a necklace for the queen their mother.

Meanwhile, the princess, jealous of her brothers, visited Wayland, bringing a golden ring for him to mend. Recognising the stolen ring as that made for his lost wife, he cruelly seduced the princess, leaving her with child. Having sent her and the horrific treasures back to the palace, Wayland strapped on a pair of mechanical wings, rose into the sky and flew away.

It is not quite clear how this tale links up to the burial mound, although the ancient site may have been given its new identity by Anglo Saxon invaders.

Certainly the tale travelled and adapted. One version claims that Wayland’s wings brought him to the mound, and that the Norse hero Sigurd brought his horse there to be shod. Some say that explains the white horse set in the chalk, who leaves the hillside once every hundred years and gallops across the sky to the smithy to be shod.

To me, this tale is loaded with contrasting images – the stolen skins of the swans, the broken wedding ring, the patient and desolate waiting, the greed of the powerful, the Samson-like captivity, the image of those awful golden chalices, and thee Daedulus-like wings – and they all make the tale of Wayland unforgettable. One cannot love or admire him, yet there is something enigmatic about his tale and about the unbound rage that creates such dreadful treasures.

The crippled smith’s name is mentioned in Beowulf, in the poem Volundarkvitha (part of the poetic Edda) as well as in Chaucer’s writings, in Kipling’s 'Puck of Pooks Hill', and in 'Kenilworth'. He is said to be a fore-runner of St Clement, patron saint of blacksmiths and both have feast days in November.

Why does the Wayland story matter to my writing? When I wrote my novel 'A Boy Called Mouse', I came to a section where my Mouse needed to have a place where he could rage and let out all the anger he felt. The pattern of his world had shifted dreadfully and he needed time in the wilderness to move out from his terrible grief, and renew his hope for his quest.

The image of that ancient site came into my head and the long path running alongside, and the wild storm overhead. So I created a “tramping man”, a character called Wayland. He is not a man who would put out my young hero’s eyes, but a wise kindly figure who makes Mouse to walk and walk and keep on walking along the high ridge of ground while a storm rages around them, almost Lear-like. Wayland. This agonising march moves Mouse out of his despair and sets him free for his future. The tales don’t fit easily together but for me, something matched.

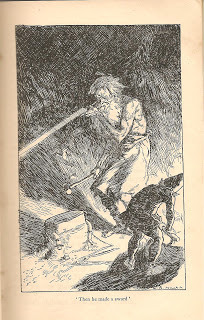

'Weland forges the Sword' - by H R Millar, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill'

'Weland forges the Sword' - by H R Millar, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill'

* The Uffington White Horse, a bronze age chalk figure cut into the hillside.

My friend Penny Dolan is a Yorkshire lass like me, a storyteller as well as a children’s writer, and we share a delight in that feistiest of fairytale heroines, the beautiful and dauntless Lady Mary from ‘Mr Fox’. We’re also both members of ‘The History Girls’, a blog devoted to the discussion of historical fiction.

Penny is the author of many picture books and fairytale retellings for younger children, as well as longer books for junior readers. Notable among these is ‘The Third Elephant’, a lovely tale of a small wooden elephant who longs to see more of the world than his dusty mantelpiece:

When night came, the small elephant looked at the empty pool of moonlight. He thought about what the mouse had told him: wish for what you want, wish for what you dream about. ‘I wish’, he thought, as hard as he could, ‘I wish I could see the white palace again.’

In the classic tradition of change coming to discarded toys, the little elephant is thrown from the window and falls into the hands of a young girl on her way to play the flute in a concert - and the adventures begin. ‘Charming’ is an adjective which can sometimes be suspected of carrying the subtext ‘trivial’, but this is a book which is both truly charming and seriously involved with the fears and uncertainties of childhood. Her most recent novel, 'A Boy Called M.O.U.S.E’ is ‘a historical fairy tale’, a beautifully written, carefully researched story of a young boy wandering the roads of Victorian England, and is full of allusions to Victorian fiction, the theatre, and old legends about larger-than-life wanderers on the old roads of England - including Wayland himself.

Penny has an adaptation of 'A Christmas Carol' coming out this autumn for the Collins Big Cat series, and a story appearing in a winter anthology "On a Starry Night", Stripes Publishing, Little Tiger Press.

Picture credits:

Wayland's Smithy: Wikimedia Commons

Wayland's Smithy

Wayland's SmithyAll that was needed, so people said, was a single coin placed on a stone beside your tethered horse. Have faith, leave the horse there all night and when you came back next morning, your steed would be newly shod and the coin gone.

Though the nights of magical shoeing are surely long past, the ancient burial mound known as Wayland’s Smithy is still there on the shoulder of chalk downland, and the place with its tangled tale, haunts me.

I first saw the Smithy on a day so wet that froglets skittered from the path into overfull ditches and milky water ran down the cracks in the chalky clay.

The rain gods had only paused. By the time we had reached the crest of the ridge, a downpour had began. Thunder rolled around the hills and as we approached Wayland’s Smithy, the huge, dark clouds above were lit with streaks of lightning.

The long barrow lies off the track. We pushed through wet bushes and came to it, covered in grass and surrounded by grove of trees. Several ancient stones formed the gateway.

With the storm raging, the moment felt as if the past was only a shadow away. It was impossible not to think of the many feet that had passed along the Ridgeway and made the path, with or without horses to be shod. Did they all wonder at the mysterious mound or the strange white horse* spread across the hillside nearby? Did they seek shelter in the small wood?

However, the helpful smith of the legend does not match entirely happily with the Norse version of Wayland the Smith.

Wayland, or Volund, had been apprenticed to the dwarves of the Icelandic Mountains, He was one of the three sons of Wade, the king of the Finns. Out hunting, the brothers found three beautiful swan maidens, seized their feathered robes, and made them their wives. When the three sisters discovered their hidden feathers again, they flew away to freedom.

The two older brothers went searching for their wives, but the desolate Wayland stayed working at his smithy, sure that his beloved wife would return for the golden ring he was keeping for her and all the other treasures he was creating.

Soon rich men grew greedy for Wayland’s skills, King Niduth of Sweden more than any. Wayland was lured to his castle, crippled, imprisoned on an island and made to forge endless objects for the king. So dazzling were the treasures and so great the family’s pride that they forgot to be wary of their prisoner.

The two princes visited Wayland, who treated them kindly until they mocked him. Enraged, he beheaded them both and fashioned a set of dreadful gifts for the royal parents. The princely skulls became golden goblets, the eyes glittering gems from their eyes, and their pearly white teeth made a necklace for the queen their mother.

Meanwhile, the princess, jealous of her brothers, visited Wayland, bringing a golden ring for him to mend. Recognising the stolen ring as that made for his lost wife, he cruelly seduced the princess, leaving her with child. Having sent her and the horrific treasures back to the palace, Wayland strapped on a pair of mechanical wings, rose into the sky and flew away.

It is not quite clear how this tale links up to the burial mound, although the ancient site may have been given its new identity by Anglo Saxon invaders.

Certainly the tale travelled and adapted. One version claims that Wayland’s wings brought him to the mound, and that the Norse hero Sigurd brought his horse there to be shod. Some say that explains the white horse set in the chalk, who leaves the hillside once every hundred years and gallops across the sky to the smithy to be shod.

To me, this tale is loaded with contrasting images – the stolen skins of the swans, the broken wedding ring, the patient and desolate waiting, the greed of the powerful, the Samson-like captivity, the image of those awful golden chalices, and thee Daedulus-like wings – and they all make the tale of Wayland unforgettable. One cannot love or admire him, yet there is something enigmatic about his tale and about the unbound rage that creates such dreadful treasures.

The crippled smith’s name is mentioned in Beowulf, in the poem Volundarkvitha (part of the poetic Edda) as well as in Chaucer’s writings, in Kipling’s 'Puck of Pooks Hill', and in 'Kenilworth'. He is said to be a fore-runner of St Clement, patron saint of blacksmiths and both have feast days in November.

Why does the Wayland story matter to my writing? When I wrote my novel 'A Boy Called Mouse', I came to a section where my Mouse needed to have a place where he could rage and let out all the anger he felt. The pattern of his world had shifted dreadfully and he needed time in the wilderness to move out from his terrible grief, and renew his hope for his quest.

The image of that ancient site came into my head and the long path running alongside, and the wild storm overhead. So I created a “tramping man”, a character called Wayland. He is not a man who would put out my young hero’s eyes, but a wise kindly figure who makes Mouse to walk and walk and keep on walking along the high ridge of ground while a storm rages around them, almost Lear-like. Wayland. This agonising march moves Mouse out of his despair and sets him free for his future. The tales don’t fit easily together but for me, something matched.

'Weland forges the Sword' - by H R Millar, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill'

'Weland forges the Sword' - by H R Millar, from 'Puck of Pook's Hill'* The Uffington White Horse, a bronze age chalk figure cut into the hillside.

My friend Penny Dolan is a Yorkshire lass like me, a storyteller as well as a children’s writer, and we share a delight in that feistiest of fairytale heroines, the beautiful and dauntless Lady Mary from ‘Mr Fox’. We’re also both members of ‘The History Girls’, a blog devoted to the discussion of historical fiction.

Penny is the author of many picture books and fairytale retellings for younger children, as well as longer books for junior readers. Notable among these is ‘The Third Elephant’, a lovely tale of a small wooden elephant who longs to see more of the world than his dusty mantelpiece:

When night came, the small elephant looked at the empty pool of moonlight. He thought about what the mouse had told him: wish for what you want, wish for what you dream about. ‘I wish’, he thought, as hard as he could, ‘I wish I could see the white palace again.’

In the classic tradition of change coming to discarded toys, the little elephant is thrown from the window and falls into the hands of a young girl on her way to play the flute in a concert - and the adventures begin. ‘Charming’ is an adjective which can sometimes be suspected of carrying the subtext ‘trivial’, but this is a book which is both truly charming and seriously involved with the fears and uncertainties of childhood. Her most recent novel, 'A Boy Called M.O.U.S.E’ is ‘a historical fairy tale’, a beautifully written, carefully researched story of a young boy wandering the roads of Victorian England, and is full of allusions to Victorian fiction, the theatre, and old legends about larger-than-life wanderers on the old roads of England - including Wayland himself.

Penny has an adaptation of 'A Christmas Carol' coming out this autumn for the Collins Big Cat series, and a story appearing in a winter anthology "On a Starry Night", Stripes Publishing, Little Tiger Press.

Picture credits:

Wayland's Smithy: Wikimedia Commons

Published on October 19, 2012 00:46

October 12, 2012

In Defence of Poesie

Here is that very perfect knight Sir Philip Sidney, Elizabethan golden boy, courtier, soldier, poet and all-round Renaissance man. Looking a bit stern here, not a lot of fun perhaps - but I think we would have liked him: he seems to have charmed most people. Not only did he write the elaborate prose 'Arcadia' for his sister the Countess of Pembroke (in which the simple phrase 'It was spring' is delightfully embroidered into: 'It was in the time that the earth begins to put on her new apparel against the approach of her lover, the sun, and that the sun, running a most even course, becomes an indifferent arbiter between the night and the day...') but he also delighted in the kind of simple old tale 'that holdeth children from play and old men from the chimney corner,' and who said of popular ballads, 'I never heard the old song of Percy and Douglas that I found not my heart moved more than with a trumpet.'

The last two quotes come from his famous ‘Apologie for Poetrie’ which is a defence of invention: an argument against those people who felt, uneasily, that it was somehow wrong and childish to concern themselves with something ‘untrue’. (Plato was an early example. And they still exist today...) All fiction is invention. The perceived gulf between fantasy and realism is more mirage than fact. Sidney wrote:

I think truly, that of all writers under the sun the poet is the least liar… for the poet, he nothing affirms, and therefore never lieth. For the poet never maketh any circles about your imagination, to conjure you to believe for true what he writes.

I love that! 'No circles about your imagination': if you know that what you are reading is given to you as pure invention, not history or fact, you no longer have to grapple with belief, and you are free to apprehend the truth of the poet's imagination. Sidney goes on to point out that - surely - only a fool would call Aesop's fables lies, or mistake a play for something 'real':

None so simple would say that Aesop lied in his tales of the beasts; for whoso thinks that Aesop writ it for actually true were well worthy to have his name catalogued among the beasts he writeth of. What child is there that, coming to a play, and seeing Thebes written in great letters upon an old door, doth believe that it is Thebes?

Nevertheless, Aesop's fictional fables present succinct truths. They are not about animals, though they appear to be, but about human morals and behaviour. To miss that would be to miss the whole point.

Sidney’s argument is still valid today. The books most likely to deceive are those apparently realistic works which may or may not be well-researched. No one supposes a story about a unicorn ever really happened, but how can we know, without checking, whether a story set during World War II has any basis in fact? Sidney's further point is that fiction (or poetry) teaches truth of another sort:

No learning is so good as that which teacheth and moveth to virtue, and none can better both teach and move thereto than Poetry.

Whatever Sidney meant by virtue (and judging by his death I think he meant right behaviour: courage, courtesy, gallantry, truthfulness), in modern terms, fiction provides insights that history and science cannot: it allows us to see life from other viewpoints than our own, and to explore our own world via the mirrorlands of metaphor and fancy. We must defend poetic truth: for if we do not, we may find ourselves wrecked on the stony shores of fundamentalism, where Aesop's fables are taught in schools as natural history, and Thebes written upon an old door is Thebes indeed.

Image: Sir Philip Sidney, National Portrait Gallery, London

Published on October 12, 2012 01:18

October 9, 2012

Publication Day

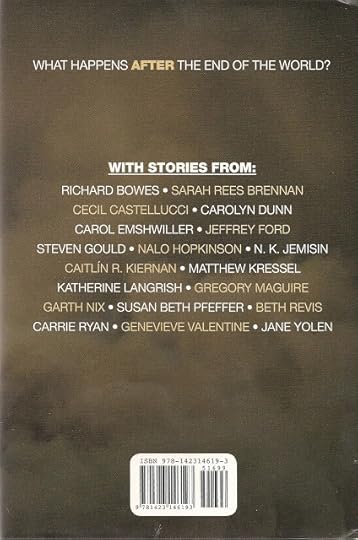

AFTERIt's publication day! And I'm doing a happy dance. Just take a look at this.

I can’t tell you how downright honoured I feel to be a part of this YA anthology of stories about what happens after the apocalypse – after the change, the meteor strike, the plague, the flood, the third World War, any number of other catastrophes that you can imagine and several that you can’t. It’s out today, ninth of October!

And here’s the front cover. Which is awesome.

Obviously I can’t properly reviewthis book, since I do have a story in it (‘Visiting Nelson’) and am definitely an interested party: but the writers’ names should speak for themselves, as should those of the editors, legendary duo Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling. I can't even say which stories are my favourites – in any case, they are all so different I keep changing my mind. Some are horrifying, many are very touching, some are full of black humour, some are audacious and fantastic.

The book itself is a beautiful physical object, with a gorgeous, slightly roughened, very tactile cover you want to keep brushing your fingers over.

Click on the links below to find what a few other people think of AFTER:

John De Nardo, for Kirkus Reviews 'Can't-Miss Science Fiction & Fantasy Books for October'

Bundle of Books

Alamosa Books

and there's even a podcast reviewing six of the stories in detail, at The Last Short Story

AFTER, ed. Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, is published in hardcover by Hyperion, New York, 9 October 2012.

Published on October 09, 2012 00:19

October 2, 2012

Unsettling Wonder

We craft and tell stories because we’ve stood on the uncertain edge between the waking world and our imagination, between enchantment and fear. And we remember other stories that help us build our own stories, scraps of lumber and fragments of narrative we gather together to make stories for ourselves.

We craft and tell stories because we’ve stood on the uncertain edge between the waking world and our imagination, between enchantment and fear. And we remember other stories that help us build our own stories, scraps of lumber and fragments of narrative we gather together to make stories for ourselves.Unsettling Wonder is a new fairytale journal dedicated to the retelling and re-imagining of traditional fairytales and folktales. Not so much putting a new spin on them, as understanding their eternal relevance:

We want to tell these tales, not as deconstruction or subversion, not as nostalgia or sentiment, but in the same way these stories have always been told—spun out and re-imagined by the tale-teller in the moment of telling, for the ones who hear it, to reclaim the magic of story.

Unsettling Wonder has only just been born, and in the way of fairytales parents we, its founders, are still looking it proudly, scratching our heads and wondering what it will make of life. Has it been born in a caul, or under a lucky star? Will its godmother be the Fairy of Good Fortune, or the sinister black-cowled figure of La Muerte? Is it even a child, or just a bristly half-hedgehog? Anyway, do come to the christening!

The website is live, so please visit to find out more about who we are and what we hope to do. You'll find an introductory article by me about the long history of fairytales and why we still want to write them. And I'll keep you posted as Unsettling Wonder grows, develops, and - we hope - finds its place in the world.

Published on October 02, 2012 01:38

September 28, 2012

The Princess As Role Model

by Gwyneth Jones

I’ve always been attracted to fairytales. I knew I was a storyteller long before I knew I’d be a writer: I took on my father’s mantle, and told epic bedtime stories to my brother and sister, at an early age, and my father’s stories (also epic, endless episodes from the same saga, about the same characters) were all based on a traditional tale, the one about a girl who finds out that she once had seven brothers, who were banished and turned into crows when she was born. It has many variants, but from internal evidence the original must be the Moroccan one (The Girl Who Banished Seven). Naturally, she sets off to find them and rescue them from the enchantment. That’s typical of a fairytale princess (she’s one of those who becomes a princess by marriage, but it’s all the same to me). They do the right thing. They stand up to evil step-mothers, and no task is impossible...

As a child I was small, podgy, clumsy and, worst of all, I was obviously going to pass that dreaded public exam called “The 11 Plus”, and go to Grammar School. I felt for the princesses in the fairytales. First they tell you you’ve been awarded fairy gifts (which you never asked for) and then wham, you’re plunged into bizarre vindictive hardship. Your mother dies, you end up sleeping in the ashes, washing bloody linen in a cave, knitting nettle shirts on a bonfire, wearing out your iron boots over razor sharp glass mountains. But I admired them too, and found them a tremendous comfort. They were so tough, so resourceful, and so decent. When everyone (not least the other little girls I knew) was telling me you are second-rate, they made me proud to be a girl. As I nursed my little bullied self home from school, by the most unobtrusive route, I thought about Cinderella. Elle s’estoit bien, says Perrault, and I wanted to be that person. To behave well, to stand up and be proud. (I knew it worked, too. The best way to frustrate a bully is to stay cheerful; be nice. It drives them absolutely nuts.)

When I was a child I responded to the bizarre adventures, the cheerful feats of endurance, the unstoppable can-do attitude of those privileged, yet beleaguered, young women. As I grew up the stories grew with me. I realised that the princess complex is a trap, it’s pure social propaganda. But I still loved the princesses, and the princes, themselves, and honoured their traditions when I started writing my own fantasy stories (published, long afterwards, as Seven Tales And A Fable). I honoured the stories, and I still do. I saw that they were more than lessons in docility, more than comforting, greedy daydreams. They were beautiful, ancient vessels, full of buried treasure. It was a very old, profound and lovely princess-story, re-written as a fantasy novel by a modern writer —'Till We Have Faces', C.S.Lewis—, that inspired me to write 'Snakehead', my own re-imagining of the story of Perseus and Andromeda.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.

'Till We Have Faces' is based on Eros and Psyche, one of the greatest of the Greek myths, and yet the story is familiar from many fairytales. A princess finds her prince and loses him. She fights her way back to his side by overcoming the fiendish magical challenges devised by a spiteful royal mother-in-law—

Seven long years I served for thee

The glassy hill I clamb for thee

The bluidy shirt I wrang for thee

Wilt thou not wake and turn to me?

(The Black Bull Of Norroway)

Perseus and Andromeda is another myth, perhaps the greatest of them all, with instant popular appeal. The hero-tale of Perseus fits in anywhere! There’s this kid, you see, brought up by his single mother, goes to High School or whatever, and then one day some supernatural beings come along. They tell him his father was a Greek God, they give him a magic sword and flying sandals, they send him off to kill a terrifying monster. He’s tall, strong and handsome! He has superpowers! He’s a teen with a mission! Oh, hey, and there’s a flying horse—

Unexpectedly, things get even better if you’re looking to write a novel rather than a comic book. The story of Perseus has complexity, it has texture. There’s the grim soap-opera of his parentage —why Danae of the shower of gold was locked up; how Zeus, the ruthless, randy chief of the Olympians, just couldn’t resist a challenge; how Perseus’s charming grandfather put both mother and child in a box and had them thrown into the sea. There’s the unconventional little family group on the island of Seriphos: Danae and her son, washed up on the shore, living under the protection of Dictys the fisherman. Whose brother is the island’s tyrant king. Imagine this boy, knowing he’s different, but with nothing to show for it, no rank, no riches. Imagine him finding out that his biological father (he’s not impressed by divine status, of course; he’s family himself) is a ruthless Mr Big who raped his mother. He knows he’s been protected at least once from certain death. He must be wondering, as he grows up, what his selfish brute of a Divine Father saved him for. Nothing good, you can bet... And then there’s Dictys. Imagine the boy’s relationship with the fisherman, who has brought him up, and never (not in any of the accounts) put a disrespectful move on Danae. He’s been a true father. Dictys seems to be a man of peace, since he’s able to live and let live, with his wicked brother on the throne. How is his adopted son really going to feel, when the Messenger of the Gods, and the Goddess Athini waylay him on the road, and tell him he has to chop off the Gorgon’s Head? This Gorgon who was once a woman, too beautiful for her own good, like Danae. Who was turned into a monster, to punish her for having been raped...

So it goes on, a wonderful story: the work of many hands, over thousands of years, and yet still alive, still growing, still inviting new storytellers to weave new patterns into the web. There’s only one weak point, and that’s the traditional centrepiece, where our hero finds his true princess, and has to win her by beating a string of awful vindictive challenges, thrown down by the malign Gods—

It’s weak because it doesn’t happen.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.

Andromeda isn’t a character. She’s not even as much of a character as the prince in 'The Black Bull Of Norroway'. She’s a name, and a predicament. Perseus doesn’t struggle to win her. He just passes by, on the way home from his questing work, swinging the Gorgon’s Head by the hair (not very safe! But that’s how it looks in all the pictures), and picks up a half-naked princess; like a pizza or a sandwich.

In my opinion, this just won't do!

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.

In 'Till We Have Faces' C.S.Lewis keeps his distance from the two principals, who represent, without much disguise, the human soul and the God of Love. His characters are the lesser figures. His protagonist is one of Psyche’s jealous sisters —a woman who barely exists in the original narrative. In 'Snakehead', I took the liberty of inventing the character of Andromeda, a weaver and a scholar (her name means Ruler of Men, or else Thinker) and switched things around so that she and Perseus have some previous history, before Andromeda is chained to the rock; before Perseus wanders along to slay the dragon. It just makes more sense, if Perseus knows he’s coming to the rescue of a princess; if he intends to claim her hand in marriage. It makes more sense to me personally, too. A generation ago, great writers and editors like Jane Yolen, Ellen Datlow reclaimed the traditional heritage: dismissing soft-focus, Disneyfied Snow White and Cinderella, rediscovering grim truths and quick-witted, resourceful heroines. That’s fine, that’s excellent work. But what I’ve wanted to do is to reclaim the relationships. To bring the prince and the princess together, instead of sending them off on segregated initiation trials. To let them meet as human beings, as friends, and fight side by side.

The story on record says Andromeda had to be sacrificed to punish her mother, queen Cassiopeia —who had boasted that her daughter was more lovely than a sea-nymph, and thus offended Poseidon, the God of Ocean and of Earthquakes. I don’t believe it. Child sacrifice was absolutely rife, around the shores of the Ancient Mediterranean. (Take a closer look at your Old Testament, if you don’t believe me). I’ll bet you anything it wasn’t a one-off occasion. I bet there was a lottery, and the children of the rich were usually spared, but then the queen’s political opponents decided Andromeda’s number was up. A powerful woman like Cassiopeia could have been an annoying relic of the old ways, in the days of the original story —when the Mediterranean World was leaving female-ordered civilisation behind, and patriarchal tribal rule was taking over.What would a princess do, if she found out she’d been drafted? Run for it, of course. And then what would she do, if she was a real princess; and knew some other poor girl would have to die in her place? She’d run back, of course. No matter who tried to stop her, no matter if she’d fallen in love.

Leaving Perseus with his repellent, murderous quest: a terrible choice, and just the inklings of a desperate plan—

The story of Perseus and Andromeda is the story of the founders of Homer’s Mycenae: well built Mycenae, rich in gold... way back in the Bronze Age. And from Mycenae, the baton was handed on to Athens, the cradle of western civilisation; making them a fairly significant couple, in the scheme of human history. (And by the way, Perseus and Andromeda did live happily ever after, which makes them unique among pairs of lovers featured in the Greek Myths) But is that all? The deeper I looked into the history of the Medusa, terrible to look upon, snakehaired monster, and into the history of the mighty Goddess Athini, whose name means Mind, the more they seemed to reflect each other. As if Medusa and Mind were the two faces of one truth—

Did I catch a glimpse of the original, brilliant storyteller, telling me something timeless and profound? About that mysterious birthright gift, first freely given and then painfully earned, that lies at the heart of fairytale? Maybe, maybe not. I don’t know. I’m just a storyteller, seeing pictures in the fire. Pictures that, now as then, sometimes seem playful, sometimes serious, and sometimes seem to tell me eternal things.

Here’s some writing on fairytales, and some free stories:

And here’s the Snakehead page

Gwyneth Jones is a brilliant writer of adult science fiction. ‘Bold As Love’, which won the Arthur C Clarke Award in 2002 is the first of a series of five books about a near-future Britain where society is in meltdown. There’s a violent environmental movement, an Islamist uprising in the north, a subtle but nasty dose of black magic, and a complex relationship between the main characters – three charismatic, damaged and idealistic young rock stars who become the country’s reluctant saviours and leaders of a new government, the 'Rock and Roll Reich'. The books are rich in romance, horror, and a deeply felt version of British landscape, history and myth.

Under the name Ann Halam, Gwyneth also writes YA fantasy, science fiction and horror. I’ve already talked on this blog about ‘King Death’s Garden’, a ghost story which is funny as well as very frightening. Then there’s ‘The N.I.M.R.O.D. Conspiracy’, in which a boy, haunted by the little sister who drowned while in his care, begins to think – with reason – that she may still be alive. And ‘Siberia’, a haunting and beautiful book about a girl who journeys across a frozen and repressive land carrying a ‘nut’ full of mysterious secret seeds. ‘Snakehead’, Orion 2007, is a marvellous retelling of the legend of Perseus and Andromeda.

Photo credits:

Perseus and Andromeda: a wall painting from Pompei, The National Museum of Naples.

Perseus and Andromeda: by Ingres

Perseus nd Andromeda by Edward Burne-Jones

I’ve always been attracted to fairytales. I knew I was a storyteller long before I knew I’d be a writer: I took on my father’s mantle, and told epic bedtime stories to my brother and sister, at an early age, and my father’s stories (also epic, endless episodes from the same saga, about the same characters) were all based on a traditional tale, the one about a girl who finds out that she once had seven brothers, who were banished and turned into crows when she was born. It has many variants, but from internal evidence the original must be the Moroccan one (The Girl Who Banished Seven). Naturally, she sets off to find them and rescue them from the enchantment. That’s typical of a fairytale princess (she’s one of those who becomes a princess by marriage, but it’s all the same to me). They do the right thing. They stand up to evil step-mothers, and no task is impossible...

As a child I was small, podgy, clumsy and, worst of all, I was obviously going to pass that dreaded public exam called “The 11 Plus”, and go to Grammar School. I felt for the princesses in the fairytales. First they tell you you’ve been awarded fairy gifts (which you never asked for) and then wham, you’re plunged into bizarre vindictive hardship. Your mother dies, you end up sleeping in the ashes, washing bloody linen in a cave, knitting nettle shirts on a bonfire, wearing out your iron boots over razor sharp glass mountains. But I admired them too, and found them a tremendous comfort. They were so tough, so resourceful, and so decent. When everyone (not least the other little girls I knew) was telling me you are second-rate, they made me proud to be a girl. As I nursed my little bullied self home from school, by the most unobtrusive route, I thought about Cinderella. Elle s’estoit bien, says Perrault, and I wanted to be that person. To behave well, to stand up and be proud. (I knew it worked, too. The best way to frustrate a bully is to stay cheerful; be nice. It drives them absolutely nuts.)

When I was a child I responded to the bizarre adventures, the cheerful feats of endurance, the unstoppable can-do attitude of those privileged, yet beleaguered, young women. As I grew up the stories grew with me. I realised that the princess complex is a trap, it’s pure social propaganda. But I still loved the princesses, and the princes, themselves, and honoured their traditions when I started writing my own fantasy stories (published, long afterwards, as Seven Tales And A Fable). I honoured the stories, and I still do. I saw that they were more than lessons in docility, more than comforting, greedy daydreams. They were beautiful, ancient vessels, full of buried treasure. It was a very old, profound and lovely princess-story, re-written as a fantasy novel by a modern writer —'Till We Have Faces', C.S.Lewis—, that inspired me to write 'Snakehead', my own re-imagining of the story of Perseus and Andromeda.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.

Perseus and Andromeda - a wall painting from Pompei. The dignified classical take.'Till We Have Faces' is based on Eros and Psyche, one of the greatest of the Greek myths, and yet the story is familiar from many fairytales. A princess finds her prince and loses him. She fights her way back to his side by overcoming the fiendish magical challenges devised by a spiteful royal mother-in-law—

Seven long years I served for thee

The glassy hill I clamb for thee

The bluidy shirt I wrang for thee

Wilt thou not wake and turn to me?

(The Black Bull Of Norroway)

Perseus and Andromeda is another myth, perhaps the greatest of them all, with instant popular appeal. The hero-tale of Perseus fits in anywhere! There’s this kid, you see, brought up by his single mother, goes to High School or whatever, and then one day some supernatural beings come along. They tell him his father was a Greek God, they give him a magic sword and flying sandals, they send him off to kill a terrifying monster. He’s tall, strong and handsome! He has superpowers! He’s a teen with a mission! Oh, hey, and there’s a flying horse—

Unexpectedly, things get even better if you’re looking to write a novel rather than a comic book. The story of Perseus has complexity, it has texture. There’s the grim soap-opera of his parentage —why Danae of the shower of gold was locked up; how Zeus, the ruthless, randy chief of the Olympians, just couldn’t resist a challenge; how Perseus’s charming grandfather put both mother and child in a box and had them thrown into the sea. There’s the unconventional little family group on the island of Seriphos: Danae and her son, washed up on the shore, living under the protection of Dictys the fisherman. Whose brother is the island’s tyrant king. Imagine this boy, knowing he’s different, but with nothing to show for it, no rank, no riches. Imagine him finding out that his biological father (he’s not impressed by divine status, of course; he’s family himself) is a ruthless Mr Big who raped his mother. He knows he’s been protected at least once from certain death. He must be wondering, as he grows up, what his selfish brute of a Divine Father saved him for. Nothing good, you can bet... And then there’s Dictys. Imagine the boy’s relationship with the fisherman, who has brought him up, and never (not in any of the accounts) put a disrespectful move on Danae. He’s been a true father. Dictys seems to be a man of peace, since he’s able to live and let live, with his wicked brother on the throne. How is his adopted son really going to feel, when the Messenger of the Gods, and the Goddess Athini waylay him on the road, and tell him he has to chop off the Gorgon’s Head? This Gorgon who was once a woman, too beautiful for her own good, like Danae. Who was turned into a monster, to punish her for having been raped...

So it goes on, a wonderful story: the work of many hands, over thousands of years, and yet still alive, still growing, still inviting new storytellers to weave new patterns into the web. There’s only one weak point, and that’s the traditional centrepiece, where our hero finds his true princess, and has to win her by beating a string of awful vindictive challenges, thrown down by the malign Gods—

It’s weak because it doesn’t happen.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.

Andromeda and Perseus - by Ingres. The prurient neoclassical take.Andromeda isn’t a character. She’s not even as much of a character as the prince in 'The Black Bull Of Norroway'. She’s a name, and a predicament. Perseus doesn’t struggle to win her. He just passes by, on the way home from his questing work, swinging the Gorgon’s Head by the hair (not very safe! But that’s how it looks in all the pictures), and picks up a half-naked princess; like a pizza or a sandwich.

In my opinion, this just won't do!

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.

Perseus and Andromeda - by Burne-Jones. The OTT macho Pre-Raphaelite take.In 'Till We Have Faces' C.S.Lewis keeps his distance from the two principals, who represent, without much disguise, the human soul and the God of Love. His characters are the lesser figures. His protagonist is one of Psyche’s jealous sisters —a woman who barely exists in the original narrative. In 'Snakehead', I took the liberty of inventing the character of Andromeda, a weaver and a scholar (her name means Ruler of Men, or else Thinker) and switched things around so that she and Perseus have some previous history, before Andromeda is chained to the rock; before Perseus wanders along to slay the dragon. It just makes more sense, if Perseus knows he’s coming to the rescue of a princess; if he intends to claim her hand in marriage. It makes more sense to me personally, too. A generation ago, great writers and editors like Jane Yolen, Ellen Datlow reclaimed the traditional heritage: dismissing soft-focus, Disneyfied Snow White and Cinderella, rediscovering grim truths and quick-witted, resourceful heroines. That’s fine, that’s excellent work. But what I’ve wanted to do is to reclaim the relationships. To bring the prince and the princess together, instead of sending them off on segregated initiation trials. To let them meet as human beings, as friends, and fight side by side.

The story on record says Andromeda had to be sacrificed to punish her mother, queen Cassiopeia —who had boasted that her daughter was more lovely than a sea-nymph, and thus offended Poseidon, the God of Ocean and of Earthquakes. I don’t believe it. Child sacrifice was absolutely rife, around the shores of the Ancient Mediterranean. (Take a closer look at your Old Testament, if you don’t believe me). I’ll bet you anything it wasn’t a one-off occasion. I bet there was a lottery, and the children of the rich were usually spared, but then the queen’s political opponents decided Andromeda’s number was up. A powerful woman like Cassiopeia could have been an annoying relic of the old ways, in the days of the original story —when the Mediterranean World was leaving female-ordered civilisation behind, and patriarchal tribal rule was taking over.What would a princess do, if she found out she’d been drafted? Run for it, of course. And then what would she do, if she was a real princess; and knew some other poor girl would have to die in her place? She’d run back, of course. No matter who tried to stop her, no matter if she’d fallen in love.

Leaving Perseus with his repellent, murderous quest: a terrible choice, and just the inklings of a desperate plan—

The story of Perseus and Andromeda is the story of the founders of Homer’s Mycenae: well built Mycenae, rich in gold... way back in the Bronze Age. And from Mycenae, the baton was handed on to Athens, the cradle of western civilisation; making them a fairly significant couple, in the scheme of human history. (And by the way, Perseus and Andromeda did live happily ever after, which makes them unique among pairs of lovers featured in the Greek Myths) But is that all? The deeper I looked into the history of the Medusa, terrible to look upon, snakehaired monster, and into the history of the mighty Goddess Athini, whose name means Mind, the more they seemed to reflect each other. As if Medusa and Mind were the two faces of one truth—

Did I catch a glimpse of the original, brilliant storyteller, telling me something timeless and profound? About that mysterious birthright gift, first freely given and then painfully earned, that lies at the heart of fairytale? Maybe, maybe not. I don’t know. I’m just a storyteller, seeing pictures in the fire. Pictures that, now as then, sometimes seem playful, sometimes serious, and sometimes seem to tell me eternal things.

Here’s some writing on fairytales, and some free stories:

And here’s the Snakehead page

Gwyneth Jones is a brilliant writer of adult science fiction. ‘Bold As Love’, which won the Arthur C Clarke Award in 2002 is the first of a series of five books about a near-future Britain where society is in meltdown. There’s a violent environmental movement, an Islamist uprising in the north, a subtle but nasty dose of black magic, and a complex relationship between the main characters – three charismatic, damaged and idealistic young rock stars who become the country’s reluctant saviours and leaders of a new government, the 'Rock and Roll Reich'. The books are rich in romance, horror, and a deeply felt version of British landscape, history and myth.

Under the name Ann Halam, Gwyneth also writes YA fantasy, science fiction and horror. I’ve already talked on this blog about ‘King Death’s Garden’, a ghost story which is funny as well as very frightening. Then there’s ‘The N.I.M.R.O.D. Conspiracy’, in which a boy, haunted by the little sister who drowned while in his care, begins to think – with reason – that she may still be alive. And ‘Siberia’, a haunting and beautiful book about a girl who journeys across a frozen and repressive land carrying a ‘nut’ full of mysterious secret seeds. ‘Snakehead’, Orion 2007, is a marvellous retelling of the legend of Perseus and Andromeda.

Photo credits:

Perseus and Andromeda: a wall painting from Pompei, The National Museum of Naples.

Perseus and Andromeda: by Ingres

Perseus nd Andromeda by Edward Burne-Jones

Published on September 28, 2012 00:41

September 24, 2012

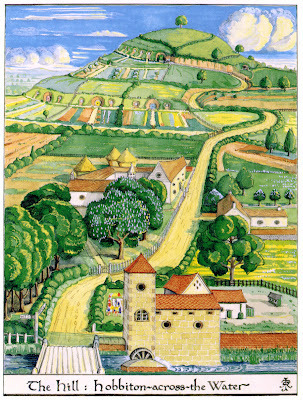

A Hobbity Weekend

As I'm sure you know, 'The Hobbit' was seventy-five on Friday last. Quite clearly the only possible response was to hurry off to a Party of Special Magnificence. Which was the reason I found myself in London for an evening of celebratory readings and conversation at the British Library.

The speakers were the academic and writer Adam Roberts (author of the spoof 'The Soddit'); the ebullient and talented writer and broadcaster Brian Sibley , who created the BBC radio versions of The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings; David Brawn of HarperCollins, who was there to show us many of Tolkien's own marvellous illustrations (published in a wonderful book called The Art of the Hobbit); and Jane Johnson, a Tolkien expert and lifelong enthusiast, who has also written the companion books to all the films.

The speakers were erudite and entertaining, the readings were rich and marvellous, and the artwork was haunting and evocative. I learned several things I'd never known (although I'm sure all Real Fans do), such as the fact that in the first edition of The Hobbit, Bilbo doesn't find the Ring; he merely wins it from Gollum as the prize for the Riddle Game - which must mean, unthinkable as it seems, that the famous line 'What has it got in its pocketses?' wasn't there in the first edition! Apparently Tolkien revised the story for the second edition, having given further thought to the antiquity and significance of the Ring. And Adam Roberts further explained that in Unfinished Tales (which I confess I personally never have finished), Gandalf comes up with several suspiciously after-thought-like reasons for sending Bilbo on the journey to the Lonely Mountain: claiming it all to have been part of his deep plan to prevent the Necromancer (Sauron) in Dol Guldur from forming an alliance with Smaug and using the dragon as a terrible weapon for evil.

As Adam Roberts remarked, it rather defies belief that Gandalf seriously decided to recruit, from the other end of Middle Earth, a band of the most unlikely possible adventurers (staid little Bilbo, plus assorted rather unfit dwarves: think of Bombur) and send them through a myriad dangers to combat Smaug, when he might more simply have addressed himself to the valiant Men of Dale, who were on the spot anyway. Far easier to believe that, in The Hobbit, Gandalf never had any such master plan, and the whole thing was the serendipitous caprice of a batty old wizard. But of such things is fiction made, and who cares about consistency anyway? Perhaps Gandalf/Tolkien can be forgiven a little bluffing on this occasion.

We all thoroughly enjoyed the evening. But that was only the first part of my Hobbity Weekend. Because on Saturday, although I should have been cooped up in my office with the curtains drawn, tapping away at the keyboard writing my book, it was such a bee-yoo-tiful day I couldn't bear to, so D. and I went off with the dog to do one of our favourite walks around the Avebury stone circle: you start below the barrows on Overton Hill (which you'll agree look remarkably like the Barrow Downs), and walk a circular four or five miles along the chalky hillside, down to the Avenue, up between the stones to the circle, and then back via Silbury Hill.

It's very Tolkieny countryside... And of course, this was the weekend of the Autumnal Equinox, so Avebury circle was full of colourful modern pagans holding their rites. Rings of folk dressed in long robes and cloaks, holding staffs and beating drums, striking huge gongs, praising the land and the spirits of the land, the oak trees and the stones, and praying as people have always prayed everywhere and in all religions, for good to befall them and their neighbours: for richness of crops and richness of soul.

We went and sat on one of the benches outside The Red Lion pub, in the sunshine, with a drink and a couple of packets of crisps. It might as well have been The Prancing Pony. Everyone was happy, everyone was friendly. Lots of people admired the dog. (She's worth admiring.) Everyone - well, almost everyone - was in what you might call fancy dress. They had beaded ribands around their brows, or feathered hats on their heads; they carried musical instruments or carven staffs or baskets full of fruit and flowers; they sported tattoos and silver nose-rings, they wore bright colours: crimson or scarlet or white satin, yellow or purple. One had a wolfhound. On the way into the pub we quite definitely brushed past Aragorn (in his disguise as Strider): a young, lean, long-haired fellow in brown and green, with a broad, dull copper band encircling one brown wrist. You half expected people to start dancing the Springle Ring.

I didn't have a camera with me, and in any case it might have been rude to snap photos of people I didn't know, but it was, I assure you, quite lovely. Perfect strangers even chatted merrily in the loos.

We bought a little empty cut glass bottle from a small antique shop run by a charming elderly village couple. (Maybe it's not empty. Maybe it's filled with starlight. I haven't tried it out in dark places yet.) The old gentleman told us how he'd been born in Avebury, in a 16th century house just down the street, and how the Romans used to camp down by the river, and about all the Roman coins he'd found. The kind lady gave our Dalmatian Polly a long drink of water in a cut glass bowl. Polly, who had spurned the water in the pub's steel dog dish, lapped it all up thirstily and had seconds.

To add to the general fairytale feel, a large double-decker bus passing through the village had 'TROWBRIDGE' written as its destination. Yes, yes, it's the county town of Wiltshire, and probably the etymology has nothing whatever to do with trolls and billygoats, but on this particular day I thought it should, don't you think? After that, we walked around the circle and through the church yard, and back past mysterious Silbury Hill, the largest man-made mound in Europe, and up the chalk to the barrows, and got in the car and drove home, passing through Marlborough, a town which - apart from the traffic - looks as though the streets ought to be full of dressed-up rabbits, and squirrels with shopping baskets on their arms.

Yes. At seventy-five, Middle Earth is alive and well.

Picture credits

The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the-Water, 1937. (MS. Tolkien drawings 26) Copyright the Tolkien Estate, reproduced here under the fair use clause of the copyright law.

The 'Hedgehog' Hill Barrows near Avebury: Wikimedia Commons, by Dickbauch

Part of Avebury stone circle and village, Wikimedia

The Red Lion, Avebury, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Use...

Katherine Langrish and Polly by Silbury Hill, copyright Katherine Langrish

High Street, Marlborough, Copyright Brian Robert Marshall and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Tumuli on Overton Hill near Avebury, Wiltshire: Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Use...

Published on September 24, 2012 01:41

September 21, 2012

ON FAIRYTALES

by Terri Windling

by Terri WindlingI've been asked to reflect on fairy tales – which, as it happens, is something that I've been doing my entire professional life: thirty years of championing re-told fairy tales as a literary art form. I've reflected so long, and written so much, on the fairy tales that have meant the most to me that my difficulty now is in finding a new approach, a new pathway into this old, old territory. And so I'm going to start by telling you a story. It begins, of course, Once Upon a Time.

Once upon a time there was a girl who was forced to flee her childhood home. Why? Let’s never mind that now. Perhaps her parents were too poor to keep her. Perhaps her mother was an ogre or a witch. Perhaps her father had promised her to a troll, a tyrant, or a beast. She left home with the clothes on her back, and soon she was tired, hungry, and cold. As night fell, she took shelter in a desolate graveyard thick with nettles and briars. Beyond the graves was a humpbacked hill and in the side of the hill was a door. The girl walked towards the door and saw a golden key standing in its lock. She turned the key, opened the door, and crossed over the threshold….

I can still remember that moonlit night, but I don’t remember how old I was -- only that I was past the age when a girl should still believe in magic. Cold and quietly miserable in a childhood that seemed never-ending, I sat hunkered down in the grass among the gravestones of my grandfather’s church, trying to conjure a portal to a magic realm by sheer force of will. Like many children, I longed to discover a door to Faerie, a road to Oz, a wardrobe leading to Narnia, and I wanted to believe that if I wished with all my strength and all my will then surely a door would open for me. Surely they would let me in.

I wanted to flee unhappiness, yes, but there was more to my desire than this – more than just escape from the intolerability of Here and Now. My desire was also a spiritual one – for we often forget that spiritual quest is a common and natural part of childhood, as young people struggle to understand how they fit into the world around them. That night, my solemn conviction was that I did not fit into the world I knew, and so I sought to cross into some other world, through the power of imagination. Did I really think it might be possible? To tell the truth, I no longer know. But my longing for that door was real; and my sharp, physical, painful desire for the things I imagined lay just beyond: Vast, unmapped, unspoiled forests. Rivers that were clean and safe to drink. Wolves and bears who would guide my way once I’d learned the power of their speech. My childhood in the ordinary world was a transient, uprooted one; but beyond the door I’d find my place, my power, and my true home.

Like many children hungry for intimate connection with the spirit-filled unknown, what I failed to manifest that night I found in my favorite children’s books: in fairy tales, myths, and other tales of border-crossing and enchantment. I read these stories over and over. I devoured them and I needed them. But there came a time when I understood that I was growing too old for fairy stories, and I slipped them to the back of the shelves, embarrassed by my attachment to them. I was dutiful. I read “realistic” books about teen detectives, inventors, and spies; I read teen romances and girl-with-horse novels. I watched the wholesome Brady Bunch and the Partridge Family on television…and nowhere in the popular culture of the ‘60s did I see a life and a family that was remotely like mine. Secretly, I still preferred those fairy stories that I was meant to out-grow. I found a strange kind of comfort in them, though I couldn’t have told you why.